INTRODUCTION

Gift exchange was central to Tudor court culture. Contemporaries held a range of attitudes toward gift-giving: they noted that gifts should be given with a generous spirit and that they promoted social bonding and loyalty, but they also observed that gifts were transactional, that they required reciprocity, that they reinforced hierarchy, and that they were useful tools for acquiring patronage.Footnote 1 Gift exchange took place between social equals, but also between the monarch and his or her subjects and between high-ranking members of the nobility and those below them. While most studies of the Tudor period focus on the gifts given to the monarch, the monarch was also expected to give generously, a fact that Felicity Heal claims is often overlooked in studies of the court.Footnote 2 Heal notes that one of Desiderius Erasmus's (1466–1536) Apophthegmes (1542) stated that “bounty and largesse is befalling [appropriate] for Kings,” and she observes that people expected a monarch to use gifts in “binding” their subjects to them.Footnote 3 The monarch was at the apex of the gift-exchange system, distributing plate and money at New Year's (in response to their subjects’ more creative offerings), but also distributing material objects (jewels, deer, clothing, paintings) and benefits all year round, including land, titles, monopolies, and positions at court or in the church.Footnote 4 As Carole Levin has noted, gifts were “part of the language of power” at court.Footnote 5

In Tudor England, books played a distinctive part in this robust culture of gift exchange. Specially prepared books were beautiful, nonperishable, portable, and often unique, and were powerful vehicles through which men and women could create or reaffirm friendships or alliances, thank or pressure recipients, or express their views on religious or political matters.Footnote 6 At court, manuscripts and printed volumes were offered to the monarch (and members of the royal family) by male and female courtiers, clerics, lawyers, and scholars. James P. Carley, Valerie Schutte, Jane Lawson, and Sarah Knight have discussed some of the books offered to Henry VIII (1491–1547), Edward VI (1537–53), Mary I (1516–58), and Elizabeth I (1533–1603) at New Year's or other occasions.Footnote 7 Scholars have also closely scrutinized some of the most striking giftbooks from this period: the manuscript psalter given to Henry VIII by Jean Mallard; the manuscripts with hand-embroidered covers offered to Henry VIII and Katherine Parr (1512–48) by Princess Elizabeth; the presentation copy of Regno Christi given to Edward VI by Martin Bucer (1491–1551); the hand-illuminated copies of Orlando Furioso given as gifts by John Harington (1560–1612); and the manuscripts presented to members of the English royal family and many others by calligrapher Esther Inglis (1571–1624).Footnote 8

This essay adds to our understanding of the giftbook in Tudor England by examining the production, the gifting, and the reception of deluxe copies of Katherine Parr's Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture. First printed on 25 April 1544 by the king's printer, Thomas Berthelet (d. 1555), Parr's anonymous octavo volume was a compilation comprised of her translation of seventeen “Psalms” (psalm collages and paraphrases) by Bishop John Fisher (1469–1535), printed around 1525 in Cologne and reprinted anonymously in London on 18 April 1544, and two prayers: Parr's translation of “A Prayer for the King,” a text derived from a prayer by Georg Witzel (1501–73); and her translation of “A Prayer for Men to say Entering into Battle” by Erasmus.Footnote 9 Henry had recently formed a military alliance with the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (1500–58), and Parr's volume was a timely publication designed to forward Henry's war effort against the Scottish, the French, and the Turks by enabling his subjects to assist him (and his army) through repentance, imprecation, and thanksgiving.Footnote 10 Parr's bellicose Psalms or Prayers is best thought of as a work of religio-political propaganda, and it was clearly produced for, and in consultation with, Henry and his advisors; as such, it provides a striking instantiation of Theresa Earenfight's argument that monarchical power was “never isolated in one person,” that the queen was “integral to the mechanisms of monarchy,” and that the queen could (if permitted) exert considerable cultural and political agency.Footnote 11 The volume was reprinted many times in octavo and sextodecimo formats between 1544 and 1613.

The copies I discuss are distinctive in several regards: they are printed on vellum and are hand illuminated; they are books that were gifted by a queen rather than to a queen; they were tied to specific military initiatives rather than to the New Year's Day gift-exchange ritual; and two of them were annotated by Henry VIII. This essay examines these volumes for the first time and studies them as material objects and media through which Parr and Henry jointly participated in the exercise and display of royal power and sacrality. The first two sections examine Parr's activities as a producer of beautiful books. Parr's chamber accounts and five extant copies of the Psalms or Prayers reveal that in addition to seeing her books through the press for widespread dissemination, she oversaw the production of special copies to be distributed as gifts. By participating in these processes, Parr transformed the material nature and social function of her texts, amplifying their aesthetic, sacred, and political character and participating in a form of social authorship. In the third section, I focus on Parr's books as media that promoted political bonding and reciprocity. I argue that they displayed Henry and Parr's generosity, learning, and political authority, and that they demanded the recipients’ military and devotional loyalty in return. As they were gifted, the special books made Parr's role as author, political agent, and a part of the Crown visible and central in ways that the books sold by Berthelet did not.

In the fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh sections, I examine two copies of Parr's 1544 book that have markings made by Henry VIII. The copy in the Elton Hall Collection is known to scholars, but I demonstrate that a copy in the Wormsley Library also has markings, and I argue that there is good reason to believe that they were made by Henry. These markings were certainly part of Henry's personal reading and writing, but because monarchs often read with others and knew that their reading was observed, I treat Henry's marginalia as writing that was also performative and understood to be visible to those in the orbit of the king and queen.Footnote 12

I argue that Parr's giftbooks with Henry's marginalia deserve careful consideration: they shed new light on the use of books in the exercise and display of monarchical power and piety at the late Henrician court; they underscore the fact that Parr had assumed an unusual, but important position as consort/author/propagandist; and they reveal the transactional textual relationship that existed between Henry and Parr. Specifically, both volumes provide material evidence of the textual labor that Parr undertook to support Henry's war effort; by writing in the books, Henry implicitly thanked Parr and his annotations might be read as a kind of countergift. At the same time, the annotations in the two books record different transactional dynamics. In the copy in the Elton Hall Collection, Henry's inscription acknowledges Parr's political labor, but it also foregrounds his authority and offers devotional directives to her (and other readers). In the Wormsley Library copy, Henry's numerous markings document his affective engagement with a devotional text during a period of political and medical crisis and record the fact that Parr's authorial labor both advanced his cause and enabled him to fulfill his religio-political duties.

THE PSALMS OR PRAYERS AND SOCIAL PUBLICATION

Parr has long been studied as one of the first English women to publish her works in print, and Kimberly Coles has recently emphasized that her Psalms or Prayers (1544) and Prayers or Meditations (1545) were best sellers in the print marketplace.Footnote 13 The large number of extant copies attests to the popularity and cultural significance of these widely distributed printed texts. As I discuss here, bills and expense vouchers from Parr's chamber accounts reveal that she simultaneously engaged in a second mode of authorship. That is, a number of Parr's texts were printed on vellum, hand illuminated, specially bound, and delivered back to her so that she could distribute them as gifts. These giftbooks resonate with Margaret Ezell's discussions of social authorship and social texts that were neither public nor private in our current understandings of the terms, but were carefully distributed by an author to select readers.Footnote 14 In focusing on the material features of these books, I am inspired by scholars who stress that the content of a book should not be “severed from its physical presentation” and that scholars must examine the “diverse material cultures through which early modern women's writing was produced, transmitted, and received.”Footnote 15

I begin with a bill that draws attention to the fact that Parr valued beautiful texts and paid to transform “unbounden” printed pages into books that incorporated elements from the manuscript tradition. William Harper was the clerk of Parr's closet and was responsible for acquiring the materials needed for worship in her devotional closet (books, plate, linen, and vestments). On 12 April 1544, he asked to be reimbursed for the following:

Imprimis paid for a Primer for her grace in Latin and English with epistles and gospels unbounden 2 s 4 d.

Item for ruling and coloring of the letters of the said Primer. And of her grace's Testament in French 5 s.

Item paid for gilding, covering and binding of the two said books 5 s.Footnote 16

This bill demonstrates that in addition to having her books bound and gilt, Parr paid to have the pages of the printed primer and New Testament “rul[ed]” and “color[ed],” thereby imitating manuscript books of hours and bibles. As Martha Driver and others have noted, the movement from manuscript to print normally entailed a movement from colored pages to black-and-white pages, for while each manuscript miniature was colored and “to some extent unique . . . woodcuts were mechanically produced and were not usually in colour unless they had been painted by hand.”Footnote 17 Like many other elite readers, Parr desired the visual and material pleasure derived from hand illumination, and she paid for printed books to be ruled and hand painted.

More importantly, Parr paid to produce deluxe copies of her own works as special copies to be distributed as gifts. In May 1544, a bill was submitted by Berthelet to the Lord Chamberlain of Parr's household that included charges for the delivery of fourteen copies of “books of the psalm prayers” for “the Queen's grace.”Footnote 18 On May 1 and May 4, a total of twelve copies were delivered to Parr's almoner, George Day, Bishop of Chichester (1501–56), and two copies were delivered to Harper. Scholars now agree that this title refers to Parr's Psalms or Prayers, a book printed by Berthelet on 25 April 1544, and that the fourteen books would not all have been for Parr's personal use:

Delivered to my lord of Chichester for the Queen's grace, the first day of May, 6 books of the psalm prayers, gorgeously bound and gilt on the leather, at 16 d the piece.

Item delivered to the clerk of the Queen's closet, for her grace, 2 of the said books of psalm prayers, likewise gorgeously bound and gilt on the leather, at 16 d the piece.

Item delivered to my lord of Chichester for the Queen's grace, the 4 of May, 6 of the foresaid books likewise bound, and gilt on the leather, at 16 d the piece.

Summa totalis 18 s 8 d.Footnote 19

It seems likely that the two copies delivered to Harper were for Parr's personal use while the twelve copies delivered to Day were to be distributed as gifts. The bill does not mention whether the “psalm prayers” were printed on vellum or paper, but it reveals that the books were all “gorgeously bound and gilt on the leather.” The latter phrase refers to gold tooling, a technique by means of which gold leaf was applied to a tooled binding with the use of glair (egg white) and heat.Footnote 20 Robert Harding notes that gilt-tooled leather bindings were commissioned through Berthelet in the 1540s, and Berthelet's account with Henry VIII (from 1541–43) shows that Henry paid two shillings (twenty-four pence) for a copy of the Summaria in Evangelia et Epistolas “gorgeously bound and gilt on the leather.”Footnote 21 Each copy of Parr's octavo Psalms or Prayers cost sixteen pence, a price that was in line with Henry's payments for the binding of similar books.Footnote 22 The key point is that Parr gave Berthelet a translation which he printed and bound in a small quantity, and that he “delivered” the volumes back to her for a social form of publication. The volume was reprinted for sale on 25 May 1544 and printed in sextodecimo format at some point in 1544, likely in the summer.Footnote 23

Parr's creation of special copies of her works did not end in 1544. Susan James has noted that she paid for four “books of Psalms” on 13 June 1546, and these may have been gift copies of the Psalms or Prayers designed to celebrate the end of the war with France.Footnote 24 The document includes the following charges for “ruling,” “binding,” and “cording”:

Imprimis for the Ruling of 4 books of Psalms 2 s.

Item for the binding of the said books 2 s 8 d.

Item for velvet for the cording of the said books 7 s.Footnote 25

This bill also included charges for “binding and cording” a Mass Book and a separate item for “a quarter yard of crimson velvet” for the “cording” of the same book.Footnote 26 According to Aaron Pratt, the use of the term cording in this document is somewhat unusual and appears to refer to the labor and process of decorating textile covering material as distinct from the covering material itself and the usual labor and process of bookbinding. It may refer to decorative work (strapwork, knotwork, embroidery, or couching) done on the covering material.Footnote 27 Embroidered books were popular: at New Year in 1539, Berthelet offered the king “a book of divers works of doctors covered with crimson satin embroidered,” and Princess Elizabeth presented Henry and Parr with manuscripts with hand-embroidered covers for the New Year in December 1544 and 1545.Footnote 28 The velvet that Parr used to cover the four “books of Psalms” is very expensive (seven shillings) and is two and half times the expense for the labor and materials for binding the books. These velvet-covered books were clearly very important to Parr as the total cost for each copy was thirty-five pence, twice as much as the copies of the “psalm prayers” from 1544.

A third bill from 4 June 1547 (after Henry's death) reveals Parr's ongoing involvement in the dynamics of social authorship. This bill from Berthelet shows that she paid sixteen pence for another special copy of the Psalms or Prayers: “A book of psalm prayers covered in white and gilt on the leather” was delivered to “master Harper for the Queen's grace.”Footnote 29 This may have been intended for personal use, but Parr's reputation was under attack in June 1547 due to her sudden marriage to Thomas Seymour (1508–49), and she may have wanted to send it herself as a gift to the king, Edward VI, or to Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset (1500–52).Footnote 30 This bill also includes six different line items pertaining to books described as “prayer books” and then as the “same prayers.” Parr ordered at least thirty (maybe thirty-one) copies of this particular book and the copies were delivered to Parr's almoner (George Day). Scholars concur that these “prayer books” were copies of Parr's second publication, Prayers or Meditations, and that the thirty or thirty-one books must have been gift copies.Footnote 31 The most striking thing about this bill is that it reveals Parr's attention to detail regarding the different material options available to her: two printed copies were “covered in white satin” and were one shilling each; ten copies were “printed in vellum” for eight pence each; nine of those ten vellum copies were bound “in white and gilt on the leather” for an additional six pence each; another twelve copies were printed and “bound in white and gilt on the leather” for six pence each; and six (five plus one) were “printed in fine vellum” and were considerably more expensive—two shillings each.Footnote 32 Parr was clearly a detail-oriented gift giver, and she chose to publish several different versions of her book, presumably adjusting the material features and costs according to the status of the recipients or the nature of their relationship.

PARR TRANSFORMS HER BOOK

While Parr's bills provide valuable data pertaining to the dates, materials, numbers of copies, and costs of her giftbooks, the fortuitous survival of five special copies of the Psalms or Prayers allows a reader to analyze her material, aesthetic, and sociopolitical choices in more detail. These five books are spectacular: they are printed on vellum; they have red-ruled borders; and they have hand-illuminated title pages, hand-drawn and painted royal coats of arms, and illuminated drop caps. Sadly, there are no extant bills pertaining to the hand illumination and none of the books have their original bindings so it cannot be known if Parr used the bindings to enhance aspects of the text. Three of the special copies of the Psalms or Prayers are octavo volumes printed on 25 April 1544. All three have the same overarching decorative program, but they have minor variations. One copy is owned by Sir Mark Getty, KBE, and is in the Wormsley Library; one copy is owned by Sir William and Lady Proby and is in the Elton Hall Collection; a third copy (which has sustained some damage) is in the Exeter College Library, Oxford University. The other two copies are sextodecimo volumes printed in 1545: there is an almost complete copy in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and an incomplete copy with a different decorative program at the Bodleian Library.Footnote 33 These five volumes complement the data provided by Parr's chamber accounts, and they provide evidence of what Parr did with the affordances of the giftbook. While all five volumes deserve careful attention, I will focus on the three copies from 25 April 1544. Presumably these three books were among the fourteen copies mentioned in Berthelet's book bill from early May 1544, but it is not clear whether the rest were illuminated as lavishly as these three or not.Footnote 34

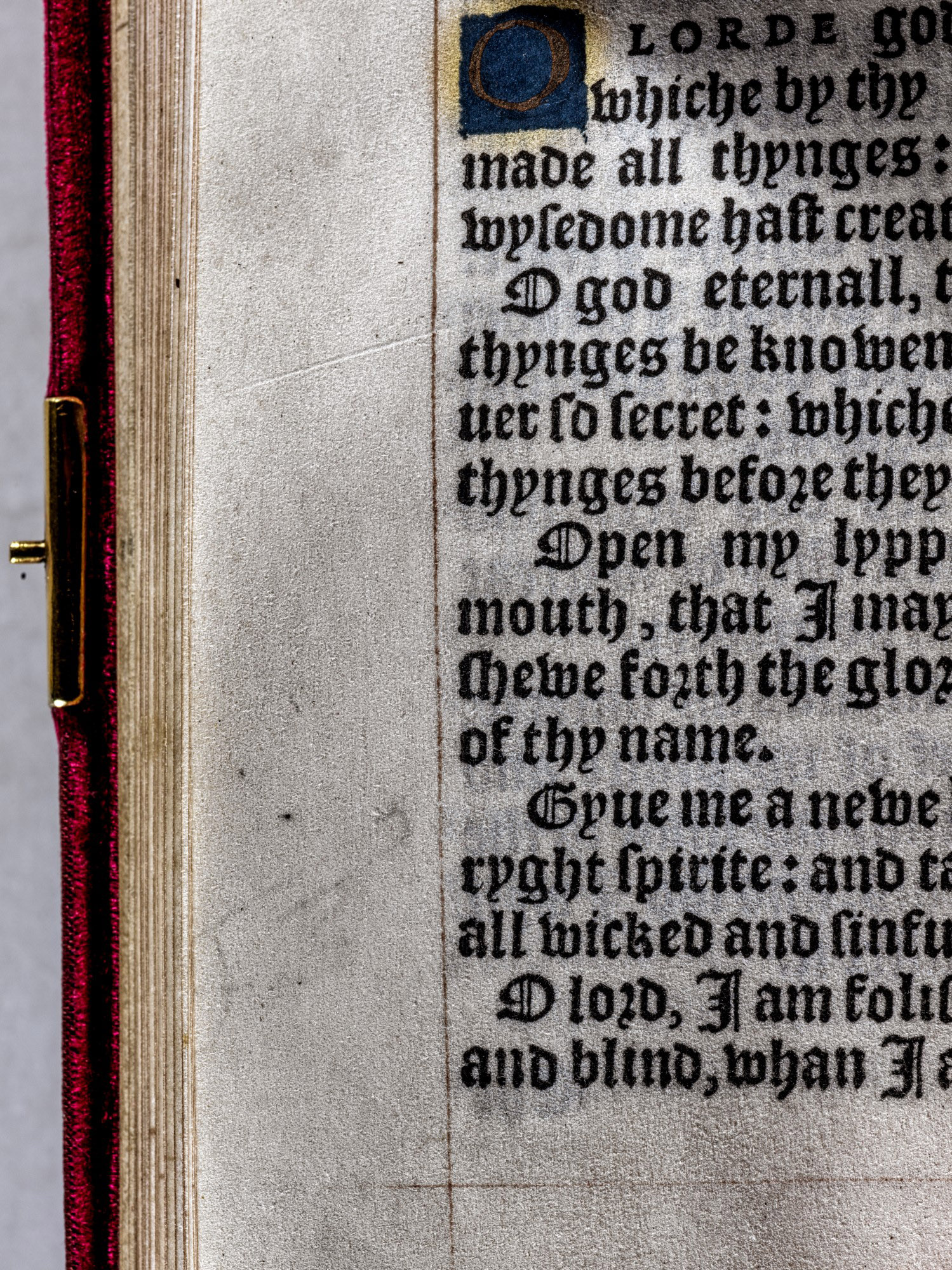

In the analysis that follows, I argue that as the Psalms or Prayers was prepared for social publication in 1544, the printed pages were transformed in ways that enhanced the volume's aesthetic and material value and amplified its political and sacred character.Footnote 35 For example, Berthelet's architectural title-page compartment was significantly altered as it was illuminated with shell gold, blue, pink, green, and red paint (fig. 1).Footnote 36 The luminosity of the gold paint would have echoed the (now lost) gold tooling on the binding and would have emphasized Henry's power and wealth as well as the sacred nature of the text. The architectural frame invokes the court spaces where Parr's book would have been gifted and read, spaces such as palace chapels, devotional closets, or the living areas of the nobility. Importantly, the limner has heightened the volume's political timeliness. Berthelet's printed title-page compartment has the date 1534 in the sill, the year he acquired the compartment. The limner has painted 1544 over the 1534, matching the Arabic numeral with the Roman numeral on the title page. The intense blue rectangle and the gold numbers draw the reader's eye to this detail and clearly locate the volume in 1544, the year of the resumption of war with Scotland and France.Footnote 37

Figure 1. Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), title page. The Wormsley Library. With permission.

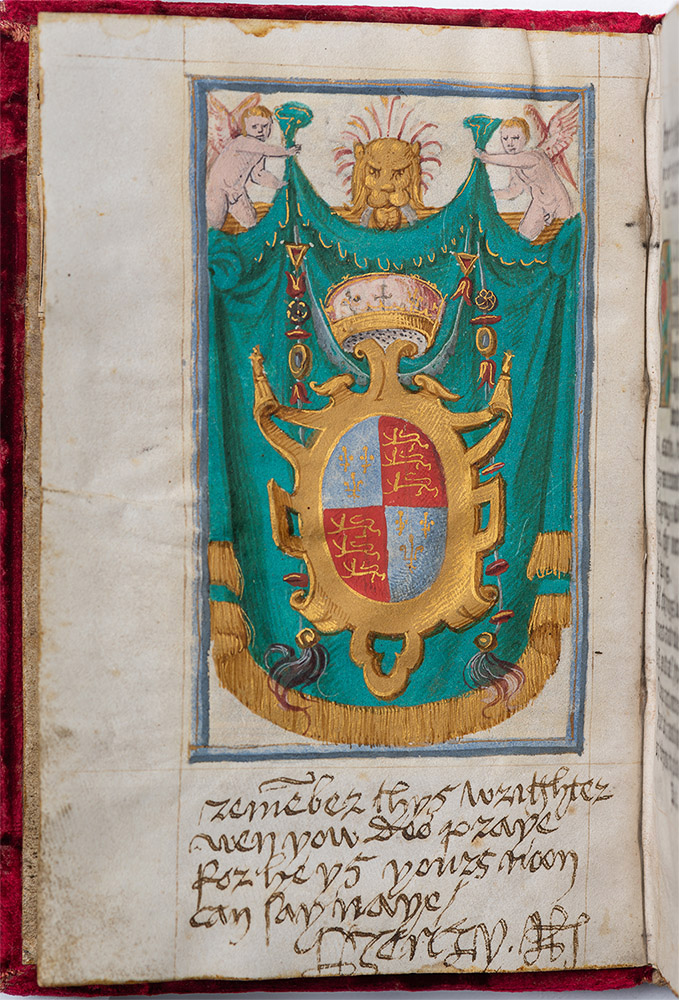

On the verso of the title page the limner has filled the blank page with a large, beautiful hand-drawn and hand-illuminated image of Henry's royal arms (fig. 2). There is a 3 mm grey and gold border that closely follows the red ruling. Two putti flank a lion's head with a gold and pink mane, and they jointly hold up a verdigris drapery that almost fills the page. The drapery has a brilliant gold fringe and serves as a backdrop for a gold frame featuring Henry's arms, an imperial crown, and tassels with jewels. On the opposite page, the limner has made another important change to the printed page. The blank space in the drop cap O that begins the “First Psalm” has been painted grey, but the rest of the initial has been covered over with shell-gold paint, and the limner has added a crimson Tudor rose with foliage (fig. 2).Footnote 38 The painted decoration utterly transforms the design of the woodcut drop cap, as can be seen in the Exeter College copy where the overpainting is almost entirely erased.Footnote 39 Thus while the printed, mechanically produced woodcut drop caps were black and white and were the same in every copy, Parr's limner made each gift volume unique and has provided additional visual pleasure for the reader.

Figure 2. Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), title-page verso–A2r. The Wormsley Library. With permission.

The addition of the coat of arms and the Tudor rose also generated new kinds of political meanings. In all copies of the Psalms or Prayers printed during Henry's reign, there are two details that make it clear that the volume was issued by the Crown: Berthelet's recognizable title-page compartment, and the colophon that announced that the book was issued by Berthelet, “printer to the King's highness.”Footnote 40 Although he did not use them in the Psalms or Prayers, Berthelet had several ornaments of the royal arms that appeared in publications such as the King's Book and volumes of Statutes and Acts of Parliament.Footnote 41 As J. Christopher Warner has argued, when readers saw Berthelet's compartment, or the royal arms ornament, or the words “Thomas Berthelet, printer to the king's highness” on a text, they would have understood “that the text was doing official service: proclaiming new laws, stating the king's views, representing the king as he wanted others to see him.”Footnote 42 The unique hand-illuminated royal arms and the Tudor rose in the gift copies of the Psalms or Prayers clearly reference those printed ornaments, and they amplify the political dimension of the text by announcing the king's authority and his endorsement of the text. But they do something more: they activate political relationships by asserting that the book has not only been printed by the Crown, but has also been personalized by the Crown and given to a select subject as a gift.

The remaining decorative elements in the gift copies recall deluxe books of hours, and they enhance both the aesthetic and religious nature of the Psalms or Prayers. The drop caps opening each of the “Psalms” (and the “Prayers”) have been overpainted with gold on a red or blue rectangular ground in a way that was typical of the manuscript books of hours owned by wealthy readers. There are similar painted drop caps in the printed book of hours signed by Anne Boleyn that is now at Hever Castle and in a printed book of hours owned by Henry VIII now at the Folger Library.Footnote 43 In Parr's book there are eleven Os decorated in this way as well as a decorated T, S, H, I, R, and two Ms. Most of the decoration occupies two lines of print, but the M at the opening of the “xxi psalm of David” occupies five lines.Footnote 44 In decorating her Psalms or Prayers to resemble a book of hours, Parr enhanced the sacred nature of her volume, reminding the recipients that Henry's war was a just and sacred enterprise and asserting that they should use the prayers as part of their daily devotional routines.

THERE'S NO SUCH THING AS A FREE BOOK:

RECIPROCITY AND THE PSALMS OR PRAYERS

Having overseen the transformation of black and white printed texts into colorful, hand-painted, deluxe objects, Parr distributed them as gifts. As early modern scholars and anthropologists have taught us, kings and queens were expected to display generosity, and while social norms asserted that gifts should be given freely, they were also given with the understanding that they would elicit some kind of reciprocity and would benefit both the receiver and the giver. In a study of the books that Elizabeth gave to Henry and Parr at New Year's, Lisa Klein observed that “gift-exchange forms social, even spiritual bonds between people who thereby establish community, assert hierarchy, and incur mutual obligations.”Footnote 45

Although there is plenty of evidence that books were given as gifts at the Tudor court, extant records often provide no information about the content of those books; the gift copies of Parr's Psalms or Prayers thus provide a valuable opportunity to study a queen's engagement in the dynamics of gift exchange in some detail.Footnote 46 There are challenges, though, in discussing these books from the perspective of exchange: Parr did not provide dedications discussing her books as gifts, and although two of the three extant copies from 1544 passed into Henry's hands, it is unclear who received the copies now at Exeter College, the University of Illinois, the Bodleian, or the other copies referred to in Parr's book bills. Nevertheless, given the volume's bellicose content it seems reasonable to surmise that the recipients would have been high-ranking courtiers (male or female) or clerics involved in the war effort.Footnote 47 Moreover, the material features and the content provide enough data to allow me to draw on Klein's terms and to hypothesize about how the gifts functioned as they were distributed at court.

In offering her books to selected recipients, Parr obviously promoted social bonding and conferred a social benefit upon them. The “gorgeously” bound illuminated vellum books were beautiful, and in offering them to a small number of people, Parr (and Henry) would have bestowed affection, honor, and prestige upon them. The books would also have unified the recipients and created a sense of political belonging focused on the war effort, a locus for the consolidation of martial values among the peerage and nobility. It is clear that the books would also have reaffirmed political hierarchies, even as they fostered community. In particular, it must be noted that in addition to amplifying Henry's political authority, the gift copies made Parr's authority as queen/translator apparent in a way that the regular, anonymous paper copies of the Psalms or Prayers sold as commodities did not. Many of the readers who purchased the book at Berthelet's premises on Fleet Street would not have known that Parr was the translator. By contrast, the gift copies presented by Parr (or her Almoner) were obviously the product of her intellectual effort and aesthetic oversight, and the recipients could not help but acknowledge her authority as wartime queen/translator/giver and their status as subjects/readers/recipients.Footnote 48 Anthropologists have emphasized that gift objects always carry with them something from their giver, and in this case, Parr offered gifts that she had produced in three stages—first by means of pen and paper, then by means of print, and finally through hand illumination and binding.

This dimension of the gift volumes would have taken on new meaning after 7 July 1544, the date Parr was appointed to serve as regent and to rule, act, and speak in Henry's name while he was in France. A dedication penned by Nicholas Udall to Parr in September 1545 confirms that Parr was recognized as an author who had undertaken literary labor connected to religio-political conflict, a role highlighted in the gift copies of the Psalms or Prayers. Udall praised Parr for producing “Psalms and contemplative meditations,” and a few lines later, he alluded to the “Prayer for Men to say Entering into Battle” and used a military analogy to describe Parr's literary activities, claiming that she was like a “good captain” who went “before” his “forward soldiers” to provide an encouraging example.Footnote 49

And what did Parr's giftbooks ask for in return? As noted above, the illuminated books emphasized Henry's and Parr's monarchical authority, and as the books changed hands they would have reminded the recipients that they were Henry's subjects and that they had a duty to reciprocate with political loyalty. Heal has argued that when subjects offered gifts to the monarch at New Year's, they “showed that they were incorporated into the personal service of the Crown, and a part of the royal body; the [Crown's] countergift affirmed this.”Footnote 50 Here I argue that Parr's gift performed the same kind of political work, but in reverse: it reminded recipients that they were “incorporated into the personal service of the Crown” and that they needed to affirm this through acts of loyalty. In thinking about this duty, it must be remembered that the Psalms or Prayers was a prayer book to be used in daily practice, rather than a prose treatise to be read silently and perhaps only once. In accepting the prayer book, the recipients were committing themselves (in theory) to taking up the devotional and political speech acts in the book. For example, recipients would have been expected to give voice to the devotional “I” in the “First Psalm” and to engage in wartime repentance in order to help Henry obtain God's forgiveness and favor: “My soul is full of filthiness, and no part of me is whole and sound. Wherefore my enemies do persecute me the more; the greatness of my pain maketh me to roar and cry . . . . Forgive me all my sins, O Lord God . . . for according to thy goodness thou has promised forgiveness of sins to them that do penance.”Footnote 51 Courtiers accompanying Henry to France would have been encouraged to use lines from the “Tenth Psalm” to ask God for assistance: “Instruct and teach my hands to battle; make my arms strong like a bow of steel. Gird me with strength to battle; overthrow them that arise against me. . . . Cast down mine enemies before my face, and destroy them that hate me.”Footnote 52 Recipients would have understood that they had a duty to use the timely “A Prayer for the King” and to ask God to “heap glory and honor upon him [Henry]. Glad him with the joy of thy countenance. So strength him, that he may vanquish and overcome all his and our foes, and be dread and feared of all the enemies of his realm. Amen.”Footnote 53 Finally, recipients leaving to fight with Henry or those remaining at court would have been expected to use the petitions from “A Prayer for Men to Say Entering into Battle”: “Our cause now being just, and being enforced to enter into war and battle, we most humbly beseech thee, O Lord god of hosts, so to turn the hearts of our enemies to the desire of peace, that no Christian blood be spilt. Or else grant, O Lord, that with small effusion of blood, and to the little hurt and damage of innocents, we may, to thy glory, obtain victory.”Footnote 54

Parr's gift, then, demanded a devotional response, and that response (prayer) might be thought of as a complex, extended countergift that expanded to include God in the dynamics of reciprocity: after accepting the giftbooks from Parr, the recipients were to offer their repentance to God, remind God of his promise to assist the repentant, and “beseech” God to reward Henry and his army with victory. In a world that believed in the efficacy of supplicatory wartime prayers, Parr's gift was asking for something valuable in return.

HENRY'S MARGINALIA: SOCIABILITY, SELF-REFLECTION, AND SELF-REPRESENTATION

Parr's deluxe giftbooks were clearly treasured and passed on by their owners, and four of the five extant copies have accrued annotations by different readers over the centuries. In what follows I will examine two copies that found their way into the hands of Henry VIII.Footnote 55 The copy in the Elton Hall Collection appears to have been Parr's personal copy and has an inscription by Henry. There is also a marked-up copy at the Wormsley Library that is currently unknown to scholars. I argue that there is good reason to believe that Henry made the markings in this copy and that the volume belonged to him. In other words, these two copies are slightly different than the copies that would have been distributed by Parr and Henry to courtiers, and they allow a reader to study the volume's reception by one of the period's most studied readers—Henry VIII.

Henry was an active and busy reader: he had a library with over two thousand volumes, and he annotated many books with his distinctive handwritten notes, manicules, trefoils, brackets, notas, and monogram.Footnote 56 The best known of these books is Henry's manuscript psalter (Royal MS 2 A XVI), but other examples include his copies of Marko Marulić's Evangelistarium (1529), Dominicus Mirabellius's Polyanthea (1514), Augustinus Triumphus of Ancona's Summa de Potestate Ecclesiastica (1475), the Institution of a Christian Man (1537), Miles Coverdale's The Books of Solomon (1545), and the Collectanea Satis Copiosa (1534). Henry also wrote inscriptions in prayer books that belonged to others, including a manuscript prayer book owned by Jane Vaux Guildford (BL, Add MS 17012) and a prayer book signed by either Anne Boleyn or Margaret Shelton (BL, Kings MS 9).

Henry wrote in his books for different purposes at different times: while much of his marginalia is scholarly, outward-looking, and focused on political topics, other marginalia is devotional and self-reflective, and still other inscriptions are social. Scholars have begun analyzing Henry's marginalia in detail, and studies by James Carley, Ian Christie-Miller, Andrea Clarke, Thomas Fulton, Michael Hattaway, Pamela Tudor-Craig, and myself have examined places where Henry left personal inscriptions or annotated passages about theological issues (good works, idolatry); political issues (divorce, kingship, his enemies); and ethical and spiritual issues (being charitable, obeying God's word, loving wisdom over riches).Footnote 57 Henry's inscription and markings in the Psalms or Prayers demonstrate his ongoing engagement with these topics, but they have an additional layer of meaning because they are found in books created by his consort. In other words, when looking at this particular marginalia, scholars need to expand their vision beyond the dyadic relationship between Henry and the text to include a third figure—Parr. Natalie Zemon Davis has observed that a book is not only a “source of ideas” but can be “carrier of relationships,” and I argue that these books—and their marginalia—register complex transactions between the king and queen.Footnote 58

Henry left several kinds of marks in the Psalms or Prayers. I treat them all as records of his individual reading and writing, but I also stress that Henry and Parr discussed books with others, knew that their reading and writing was observed, and understood that their marginalia was performative and visible to select courtiers.Footnote 59 A variety of sources provide evidence of the social nature of reading at the late Henrician court. In a letter to William Parr (Katherine's brother), Roger Ascham (1515–68) describes a meeting where he presented a gift copy of Toxophilus (1545) to Henry and Katherine Parr. Ascham notes that the presentation of the gift involved an open discussion between Katherine Parr, William Parr (the dedicatee), and Henry: the giftbook “was carried very modestly and fearfully to his Royal Majesty,” and “I still seem to see, as though gazing with admiration, how you [William] extolled this book to her Majesty Queen Catherine when she asked by chance what book it was, and how you commended it with an agreeable countenance.”Footnote 60 Ascham also reveals the highly visible nature of book ownership and reading, telling William that of “all the leading men in the realm,” he was the one in whose hands his “book longs especially to be carried about.”Footnote 61

Comments made by Nicholas Udall (1504–56) and John Radcliffe (1539–68) reveal the visible nature of the circulation and reception of Parr's books at court. In a dedication to Parr penned in September 1545, Udall described the affective responses of her courtly readers who received spiritual “consolation” and edification from her books. He lauds: “The Psalms and contemplative meditations on which your highness, in the lieu and place of vain courtly pastimes and gaming, doth bestow your night-and-day's study, and which you have set forth as well to the incomparable good example of all noblewomen, as also to the ghostly consolation and edifying of as many as read them.”Footnote 62 In a dedication to his stepfather of a Latin translation of Parr's Prayers or Meditations, Radcliffe also noted the visible popularity of Parr's text, claiming that “almost everyone carries this small book in their hands, and it is wonderfully recommended by many.”Footnote 63 As one of the people who definitely “read” and carried Parr's Psalms or Prayers “in [his] hands,” Henry must have been aware that his response to the book would be of interest to those at court. Henry's marginalia was certainly read by others and migrated to other texts. For example, Clarke has noted that Henry placed a manicule beside a passage about the validity of Old Testament moral precepts in his copy of Marulić's Evangelistarium and that this passage was then cited by the team of scholars who assembled the Gravissimae academiarum censurae (1531), a text defending Henry's right to a divorce.Footnote 64 Henry's manuscript psalter also demonstrates the broader social dimension of his annotations. The small, deluxe manuscript was designed for personal use and contains an image of Henry reading by himself in his bedchamber.Footnote 65 Yet the gorgeous text was likely seen by those in the Privy Chamber who attended to Henry's bodily needs and transported his belongings from palace to palace, and it is a fact that Henry's annotations were a kind of prized text unto themselves, as someone paid a scribe to recopy them in red ink into a printed English psalter.Footnote 66 Finally, the copy of the Psalms or Prayers in the Elton Hall Collection reveals that it also circulated to Elizabeth Tudor (and perhaps Mary Tudor and Thomas Seymour), and that they would have read Henry's inscription. As all these texts reveal, giving, reading, and annotating books was a visible activity in the late Henrician court, and I argue that while Henry used the blank spaces in the Psalms or Prayers for intimate social exchange and self-reflection, he also used them for visible, monarchical self-representation.

REMEMBER ME

The Psalms or Prayers in the Elton Hall Collection contains an inscription by Henry on the verso of the title page.Footnote 67 Henry's inscription is intimate and playful, and scholars concur that it was addressed to Parr. The volume appears to have been Parr's personal copy: it was bound early on with her personal copy of Thomas Cranmer's Litany, a liturgical text that Parr's book was designed to complement, and both books contain annotations in an italic hand that matches Elizabeth's hand ca. 1548.Footnote 68 Either Parr intended to keep the book for herself and Henry wrote in it, or she offered it to Henry who then returned it to her with the inscription (fig. 3). In any case, Henry wrote on the verso of the title page, directly underneath the hand-illuminated coat of arms:

Inscriptions like this were very common in late medieval and early modern prayer books, and although they can seem superficial, they did important work by reinforcing social, familial, and political relationships.Footnote 70 Rosalind Smith notes that writers often thought creatively about where to place inscriptions or annotations, making use of the content on the page to generate new meanings. A handwritten annotation, she observes, “alters one text with another in a process that creates something new for future readers, at the same time as it invites further annotation in an iterable process.”Footnote 71 Henry, for example, wrote a provocative inscription in a prayer book that aligned his sexual frustrations with the pains of the bleeding, suffering Christ, and Anne Boleyn (or Margaret Shelton) responded with a promise of loving kindness under an image of the Annunciation.Footnote 72 In a different hand-painted printed book of hours, Boleyn placed an inscription about hope and prayer across from an image of Mary's presentation of the infant Jesus at the temple, surely an attempt to mobilize the power of prayer to bring about a fecund future for herself.Footnote 73 And the young Katherine Parr reminded her uncle of his duty to care for his family by placing an appeal to him in a prayer book on the page with a Collect for the feast of Saint Katherine.Footnote 74 Commenting on inscriptions such as these, Smith argues that they are “strategic choices of textual collaboration, harnessing the material energy of a volume in order to direct the reader's gaze to the annotator's project of self-presentation in familial economies.”Footnote 75

Figure 3. Henry's inscription in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544b), title-page verso. The Elton Hall Collection. With permission.

In the case of the Psalms or Prayers in the Elton Hall Collection, Henry placed his inscription and monogram on a page that had been blank coming off the press, but had been filled by a limner with his royal coat of arms. Henry then added something more, and his inscription commands the reader's attention as the material trace of the hand of the king whose power is displayed so dramatically above it, a celebrity autograph par excellence. Insofar as Henry's handwritten inscription would have augmented the value of the giftbook (in the eyes of Parr and future readers), it might be thought of as a kind of countergift. The content of Henry's inscription renders this textual dynamic even more interesting, for the inscription refers to the giftbook itself. That is, Henry's conventional request for Parr to “remember” to “pray” for him takes on additional meaning because it clearly refers to the penultimate item in the volume, Parr's creatively translated “A Prayer for the King.”Footnote 76 Henry's inscription is thus multifaceted, for while he implicitly acknowledges that Parr is the writer of the prayer for the monarch and the producer of the giftbook designed to aid him, he also specifically instructs her to pray for him and his military success.Footnote 77 The letters that Parr wrote to Henry while he was in France reveal that she took this duty seriously and that she wanted him to know that she prayed for him every day. She explains that upon hearing of one of his successes, she fell to her knees and gave “most humble thanks,” hoping that God would “grant such an end and perfection in all your majesty's most noble enterprises . . . to the singular comforts of me and all your faithful subjects, who daily make our prayers and intercessions for preservation and continuance of the same.”Footnote 78

Henry's inscription is also noteworthy for the palpable tension that exists between Henry's assertion of Parr's power as beloved and the page's textual and visual reminders of his power as king. Henry instructs Parr to pray for him but then suggests that she should do so because he belongs to her: “For he is yours.” Parr, the beloved, is granted possession over Henry, the lover. Although this claim is charming, it must give us pause, for although Parr was a vital part of the Crown, she was also subject to and dependent on Henry, as his wife and political subject. In fact, according to John Foxe, Parr's life was in danger in the spring of 1546 precisely because Henry had become convinced that she had become an insubordinate “subject” who dared to “reason and argue with him so impertinently.”Footnote 79 The coat of arms underscores the kind of power Henry wielded over Parr, and the inscription might more accurately read: “for you are his none / can say nay.” In sum, this short inscription registers a nuanced textual transaction between a king and queen: Parr produced a giftbook for Henry that promoted his war; Henry added an intimate inscription that acknowledged her textual labor, underscored his authority, and issued a devotional directive to her.Footnote 80

HENRY'S HAND IN THE COPY IN THE WORMSLEY LIBRARY

There is another marked-up copy of the Psalms or Prayers, but to date it has remained unknown to scholars. The volume was purchased by Sir Paul Getty, KBE, in 1978 and is in the Wormsley Library.Footnote 81 This copy has twelve discernible markings made with a graphite pencil: eight manicules, three stylized trefoils, and one bracket.Footnote 82 There are two stylized trefoils in slightly different shades of brown ink that may (or may not) have been made by the same hand. Finally, there is one manicule made with brown ink that is clearly not made by the same hand that made the graphite manicules.Footnote 83 I have compared the markings in this copy of the Psalms or Prayers to manicules and trefoils made by dozens of early modern readers, and I argue that the graphite markings were most likely made by Henry VIII and that this was probably his copy.Footnote 84 The ink trefoils also resemble Henry's trefoils, but this attribution is less certain.

Early modern readers were exhorted to annotate their books with notes and symbols, and many did. Each reader's marks are idiosyncratic, and some well-known readers left behind enough marginalia for scholars to analyze it as a corpus and to add newfound annotations to that corpus. For example, Claire Bourne and Jason Scott-Warren have recently argued that the extensive marginalia in the Free Library of Philadelphia's copy of Shakespeare's First Folio was made by John Milton, and Mark Rankin has attributed newfound marginalia to Richard Topcliffe.Footnote 85 Henry VIII (like Milton and Topcliffe) left behind a substantial body of distinctive marginalia, and scholars have added new examples over the years. In 1965, Michael Hattaway compared the markings in a copy of Coverdale's translation of The Books of Solomon to those found in Henry's manuscript psalter and his Summa de Potestate Ecclesiastica, and he concluded that the marks in The Books of Solomon were “made by the king.”Footnote 86 Recently, Ian Christie-Miller found a previously unnoticed manicule (in red ink) in an English psalter printed by Whitchurch, and after comparing the shape of the new red manicule against manicules that Henry made elsewhere, he concluded that it had been made by Henry.Footnote 87 In what follows, I compare the graphite manicules and trefoils in the Wormsley Library Psalms or Prayers to those attributed to Henry elsewhere (and against a large number of manicules and trefoils attributed to other readers). I argue that while it is impossible to assert definitively that they were made by Henry (he did not sign the volume), there is enough evidence to conclude that they were very likely made by Henry, and that it is necessary to pursue the implications of that probability.

I begin with the eight graphite manicules. William Sherman notes that compared to other annotations, manicules are “extremely distinctive” and can be easier to identify than a person's handwriting.Footnote 88 Henry's manicules and the manicules in the Wormsley Library Psalms or Prayers share four key features which distinguish them from those made by other readers. The first distinctive feature is the shape of the hand. The Wormsley manicules (like all of Henry's manicules) are comprised of one pointed index finger and the first phalanges of three other fingers (see figs. 4 and 5), although in some instances some of the phalanges in the Wormsley copy are difficult to see because the markings are so faint. This shape distinguishes the Wormsley manicules and Henry's manicules from those that included thumbs or even five fingers.Footnote 89 Second, the Wormsley manicules have a cuff at the wrist that is shaped like the cuffs in all of Henry's manicules. These distinctive cuffs are very different from those drawn by John Dee, Ben Jonson, Richard Topcliffe, and others. Henry drew two lines that cut across the wrist, curve toward the left, meet in a point, and sometimes (but not always) curve back up to the left in a hook shape (see fig. 5). Although the cuffs have been cropped in most of the manicules in the Wormsley copy, the basic features are still visible. A third shared feature pertains to size: the distance from the tip of the index finger to the first band of the cuff in the Wormsley manicules is consistent with the distances in manicules that Henry made elsewhere. For example, this distance is 13.7 mm in the Wormsley manicule on sig. E2r (fig. 4) and 13 mm in Henry's manicule on sig. A5r in his Books of Solomon. This distance is 13.8 mm in the Wormsley manicule on sig. F1v (fig. 10) and 14 mm in Henry's manicule on fol. 76v of his psalter, Royal MS 2 A. XVI. The fourth feature is the placement of the manicules on the page. The Wormsley manicules are angled on the page just like those made by Henry: those in the right margin always point downwards with the index finger dipping below the horizontal line, at an angle usually between twenty-five and thirty-five degrees (see figs. 4 and 5), while those in the left margin point upwards at around forty degrees (see figs. 8 and 9).

Figure 4. Manicule 1 in Katherine Parr's Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. E2r. The Wormsley Library. With permission. Photo by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Figure 5. Henry's manicule in Dominicus Mirabellius, Polyanthea (Savona, 1514), detail of fol. 249r. © British Library Board. C.45.g.9.

The first graphite manicule in the Wormsley Library Psalms or Prayers occurs at sig. E2r (fig. 4). The index finger points downward at a thirty-five-degree angle and the fingertip points to the space between two lines of print. Although the cuff has been cropped, the two lines crossing the wrist and part of one of the bands is visible. In terms of the angle, finger shape, cuff band, and placement in the margin it resembles an ink manicule that Henry made in his copy of Mirabellius's Polyanthea, which is angled at thirty-two degrees and points to the space between two lines of print (fig. 5). The second manicule in the Wormsley book is at sig. E5r and it is also in the right margin pointing down at a twenty-degree angle (fig. 6). It is very faint and most of the cuff has been cropped, but in terms of the angle and the shape of the fingers, it resembles a manicule that Henry made in his copy of Marulić's Evangelistarium (fig. 7). The third manicule is in the left margin at sig. E7v and it points upwards at thirty-five degrees (fig. 8). The tip of the index finger is somewhat flat (rather than pointed) and only one band of the cuff is visible. This manicule resembles one that Henry drew in his Evangelistarium where the fingertip is also flat and the finger points upwards at forty degrees (fig. 9).Footnote 90 In both these manicules (from the left margins of the two books), the tips of the fingers are aligned with a line of print rather than with the space between the lines (as in figs. 4 and 5). The fourth manicule is in the top corner of sig. F1v and both bands of the cuff are visible (fig. 10). The index finger is angled at thirty-nine degrees and it bulges at the top. This finger resembles one that Henry drew in the Collectanea which was also angled at thirty-nine degrees (fig. 11), and the cuff is similar to a cuff in Henry's Collectanea (fig. 13).Footnote 91 There appears to be another manicule at sig. F1v right above a trefoil (fig. 10). I count this is as a fifth manicule, but it is too faint to match with other manicules from Henry's books. There is a sixth manicule at the top of sig. F2v, but it is also too faint to match with other manicules (fig. 17). A seventh manicule is at sig. F3v and has a shape that is somewhat different from the other ones in the Psalms or Prayers (fig. 12). The three partial fingers are not well defined and the bands on the cuff were drawn at a different angle from those on the manicule at sig. F1v. Nevertheless, the angle of the manicule (forty degrees) and the overall shape of the phalanges and the cuff resemble a manicule that Henry drew in the Collectanea (fig. 13).Footnote 92 The eighth manicule is in the right margin at sig. F4r, but the three fingers are difficult to see (fig. 14). The angle of the finger and the shape of the cuff recall one of Henry's manicules in the Collectanea (fig. 15).

Figure 6. Manicule 2 in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. E5r. The Wormsley Library. With permission. Photo by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Figure 7. Henry's manicule in Marko Marulić, Evangelistarium (Cologne, 1529), detail of 27. © British Library Board. 843.k.13.

Figure 8. Manicule 3 and illuminated drop cap in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. E7v. The Wormsley Library. With permission. Photo by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Figure 9. Henry's manicule in Marko Marulić, Evangelistarium (Cologne, 1529), detail of 6. © British Library Board. 843.k.13.

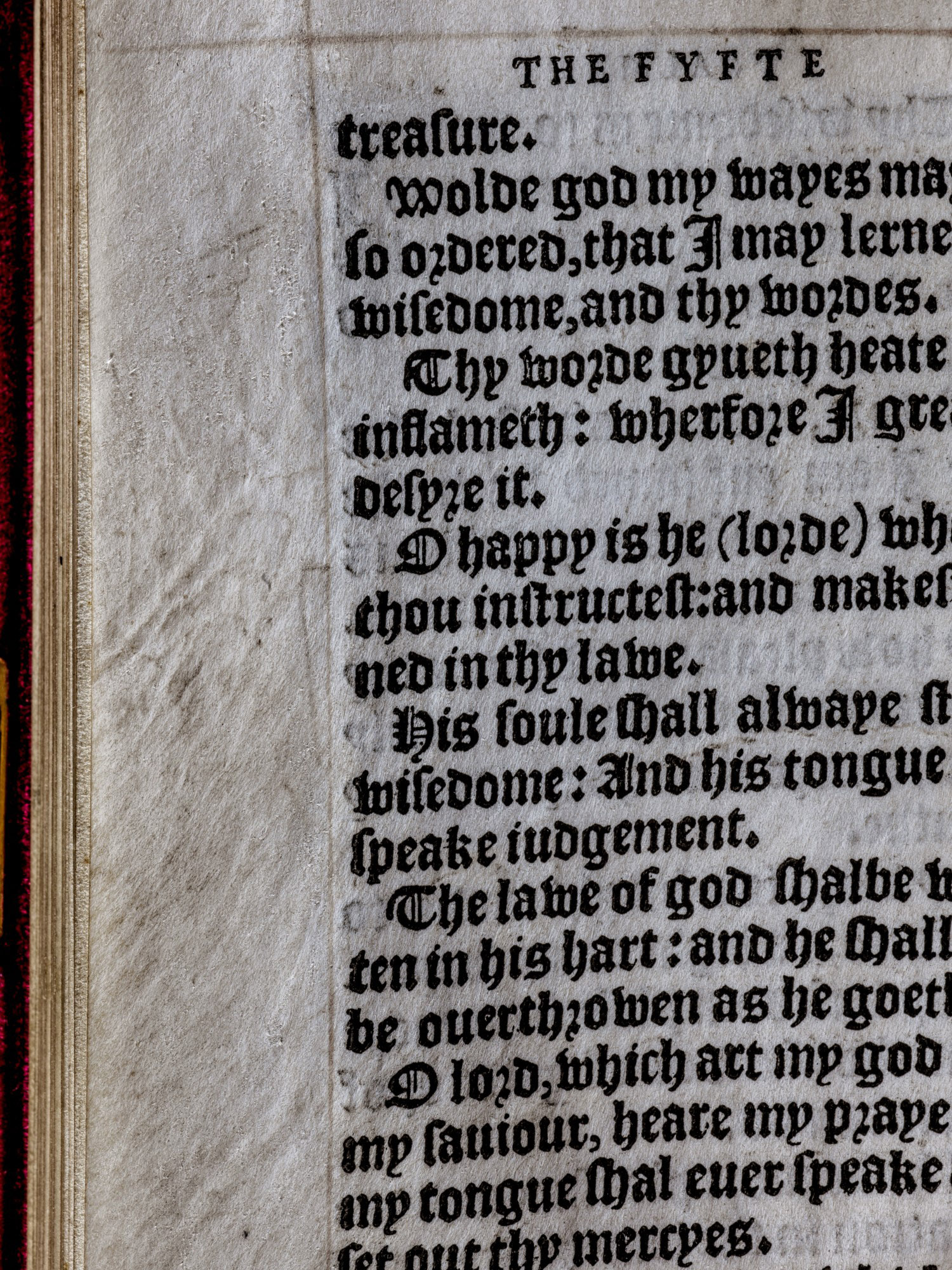

Figure 10. Manicule 4, manicule 5, and graphite trefoil 1 in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. F1v. This page is part of the “Fifth Psalm.” The “sixte” is a printing error. The Wormsley Library. With permission. Photo by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Figure 11. Henry's manicule in Collectanea satis copiosa, detail of fol. 29r. © British Library Board. London, British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra E VI.

Figure 12. Manicule 7 in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. F3v. This page is part of the “Fifth Psalm.” The “sixte” is a printing error. The Wormsley Library. With permission. Photo by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Figure 13. Henry's manicule in Collectanea satis copiosa, detail of fol. 28v. © British Library Board. London, British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra E VI.

Figure 14. Manicule 8 in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. F4r. The Wormsley Library. With permission. Photo by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Figure 15. Henry's manicule in Collectanea satis copiosa, detail of fol. 32r. © British Library Board. London, British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra E VI.

In addition to the eight graphite manicules, the margins of the Psalms or Prayers contain three graphite stylized trefoils that appear to be made with the same instrument.Footnote 93 Henry drew hundreds of trefoils in his books, but because he drew them in several different shapes and sizes, they are less immediately recognizable. The three graphite trefoils in the Wormsley volume all have different shapes, but they all strongly resemble trefoils made by Henry elsewhere. The first graphite trefoil is found on sig. F1v, just below the fifth manicule (fig. 10). The three dots are more like vertical lines and the short line, or tail, angles sharply to the right at fifty-five degrees above the horizontal plane. This trefoil resembles many of Henry's trefoils, especially ones that he drew right below a manicule, as he did in his Evangelistarium where the tail is also at a fifty-five-degree angle (fig. 16). The second, very faint, graphite trefoil in the Wormsley volume is at sig. F2v and is very different, with a long tail that hooks to the left at the top (fig. 17). Many of Henry's trefoils have this shape, and a good example can be seen in The Books of Solomon, although the graphite pencil that Henry used while annotating the latter had a thicker lead (fig. 18).Footnote 94 The Wormsley annotator has also drawn a faint bracket at a ninety-degree angle which begins around the center of the trefoil on sig. F2v, but fades off (fig. 17). Most of Henry's brackets have a curved shape, but there are a few places where Henry's brackets resemble the one in the Wormsley volume (fig. 19). There is a third graphite trefoil in the Wormsley volume at sig. G3v with a short, wavy tail (fig. 20), and it resembles a trefoil that Henry made in his Books of Solomon (fig. 21).

Figure 16. Henry's trefoil in Marko Marulić, Evangelistarium (Cologne, 1529), detail of 569. © British Library Board. 843.k.13.

Figure 17. Manicule 6, graphite trefoil 2, and bracket in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. F2v. The Wormsley Library. With permission. Photo by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Figure 18. Henry's trefoil in Miles Coverdale, trans., The Books of Solomon, namely: Proverbia, Ecclesiastes, Sapientia, and Ecclesiasticus, (London, ca. 1545), detail of sig. A6r. © British Library Board. C.25.b.4 (1).

Figure 19. Henry's bracket in the psalter of Henry VIII, detail of fol. 37v. © British Library Board. London, British Library, Royal MS 2 A XVI.

Figure 20. Graphite trefoil 3 in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. G3v. The Wormsley Library. With permission.

Figure 21. Henry's trefoil in Miles Coverdale, trans., The Books of Solomon, namely: Proverbia, Ecclesiastes, Sapientia, and Ecclesiasticus, (London, ca. 1545), detail of sig. A6v. © British Library Board. C.25.b.4 (1).

The margins of the Wormsley Library Psalms or Prayers also contain two trefoils in different shades of brown ink which appear to have been made with different writing instruments, based on the shape of the dots (figs. 22 and 23). They do not resemble the pencil trefoils in the Psalms or Prayers (which are all different), but they do resemble trefoils that Henry made in his manuscript psalter and other books (see fig. 24). The length of the trefoil in figure 22 is similar to that of the top trefoil in figure 24 (11 mm and 12 mm). The length of the trefoil in figure 23 is similar to that of the bottom trefoil in figure 24 (7.2 mm and 8 mm) and the shape of the ink dots is very similar. While the ink trefoils in the Wormsley volume may have been made by a different reader, it is very possible that they were also made by Henry at a different reading session.

Figure 22. Ink trefoil 1 in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. E8v. The Wormsley Library. With permission. Photo by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Figure 23. Ink trefoil 2 in Katherine Parr, Psalms or prayers taken out of holy scripture (London, 1544a), detail of sig. G4v. The Wormsley Library. With permission. Photo by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Figure 24. Henry's graphite and ink trefoils in the psalter of Henry VIII, detail of 9r. © British Library Board. London, British Library, Royal MS 2 A XVI.

If the features of the graphite manicules and trefoils strongly suggests that they were made by Henry VIII, the provenance history of the Wormsley Library volume provides a degree of additional support for this attribution. The Short Title Catalogue (second edition) lists Boies Penrose (d. 1976) as the owner of this copy of STC 3001.7. A long note written by Penrose on the front flyleaf explains that the book came from the library of Miss J. M. Seymour, and that he purchased it from Sotheby's on Wednesday, 4 April 1928.Footnote 95 Sotheby's catalogue states that the volume was “King Henry VIII's copy,” noting that it was printed on vellum, was “emblazoned with the royal arms,” was “in all probability specially printed for King Henry VIII,” and was being sold by one (J. M. Seymour) who was “eleventh in direct descent from the Protector Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, Henry VIII's executor.”Footnote 96 Penrose copied out the material from the catalogue onto the flyleaf and repeated this attribution, claiming that the book was “King Henry VIII's own copy” (which he underlined twice).Footnote 97 He added one additional piece of information: “The accepted tradition in the Seymour family was that Henry VIII had left this book to Somerset & so it had been handed down in the direct line.”Footnote 98 It would appear that neither J. M. Seymour nor Penrose noticed the markings in the book or their connection to Henry, for they make no mention of them. In sum, this copy of the Psalms or Prayers contains an exciting new collection of marginalia which was very likely made by Henry VIII.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND EXEMPLARY PIETY

So what does this new corpus of Henrician marginalia in Parr's book reveal? Henry's markings in the Wormsley Library copy are quite different from the inscription in the Elton Hall Collection copy and from the theological or political commentary he made in books such as Marulić's Evangelistarium. Sherman has argued that the manicule is a particularly interesting kind of marking because it has a “gestural function that extends beyond its straightforwardly indexical one,” and in this volume, Henry's manicules and trefoils record a deep, affective engagement with the fourth, fifth, and seventh “Psalms.”Footnote 99 The verses he marked are comprised of supplicatory passages from the psalms and biblical books associated with King Solomon. Thus, as he paused in his reading and marked these specific supplicatory passages, Henry used his writing instrument to activate Parr's text, enabling it to speak on his behalf and ask God for assistance. David and Solomon provided important models for early modern kings, and Henry drew on these kings as a way of representing himself in paintings, tapestries, and the title pages of the Coverdale Bible (1535) and the Great Bible (1539).Footnote 100 Henry also annotated verses in his manuscript psalter and his Books of Solomon, thereby displaying a profound affinity with the words of those exemplary monarchs.Footnote 101 Parr's gift copy of the Psalms or Prayers provided Henry with another special book in which to undertake this kind of monarchical self-reflection, ventriloquism, and self-representation.

More specifically, in the Wormsley Library volume, Henry annotated verses in which the speaker begs God for the cessation of physical suffering, for forgiveness, and for the imparting of divine wisdom. These verses resonate powerfully with Henry's situation between the spring of 1544 and his death in January 1547: his body natural was gravely impaired; he was a wartime king faced with momentous and costly decisions; and he faced a number of domestic crises.Footnote 102 As he made his markings in Parr's book, Henry grappled with his challenging predicament, fulfilled his spiritual and political duties, displayed his monarchical piety, and implicitly thanked Parr for her textual labor. As in the case of the Elton Hall copy, I read this marginalia as a kind of visible countergift that underscored Parr's value as queen/author.

The first two graphite manicules occur in the “Fourth Psalm” described as “a Complaint of a Penitent Sinner, which is Sore Troubled and Overcome with Sins.”Footnote 103 Here Henry has marked verses in which the speaker begs for mercy and bewails the physical suffering he is experiencing as a punishment for his sins:

manicule 1: Take away thy plagues from me, for thy punishment hath made me both ☚

feeble and faint.

For when thou chastisest a man for his sins, thou causest him by and by to consume and pine away.Footnote 104

manicule 2: Turn away thine anger from me, that I may know that thou art more ☚

merciful unto me than my sins deserve.

What is my strength, that I may endure? Or what is the end of my trouble, that my soul may patiently abide it?

My strength is not a stony strength, and my flesh is not made of brass.Footnote 105

These two manicules mark very similar verses in which the speaker begs God to “take away” or “turn away” his “plagues” and “anger.” The verses surrounding these lines underscore the distressing weakness of human “flesh” which is “feeble and faint,” which is “not made of brass,” and which will “pine away” under chastisement. In the “Seventh Psalm,” there is an ink trefoil beside a related verse in which the speaker worries that his sins will cause God to forsake him:

ink trefoil 2: ✢ O Lord God forsake me not, although I have done no good in thy sight.Footnote 106

These three markings clearly resonate with Henry's dire physical predicament from 1544 onwards. He was obese and suffering from a purulent ulcer on his leg. In May 1544, the imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (ca. 1490–1556), told the Holy Roman Emperor that in addition to his “age and weight,” Henry had “the worst legs in the world,” but that “no one dare tell him so.”Footnote 107 Henry may have been reticent about his medical woes in front of his subjects and military allies, but in the margins of Parr's book he engaged head-on with some unpleasant facts: he was England's divinely ordained monarch, yet his aging, sinful body was “feeble and faint,” and although he believed his actions were just, he also believed that God sent sickness as a punishment and might forsake him. In marking these verses in Parr's book, Henry both confronted the ugly truth and revealed himself to be an exemplary monarch by responding to the crisis by begging God to “turn away” his anger and extend mercy.

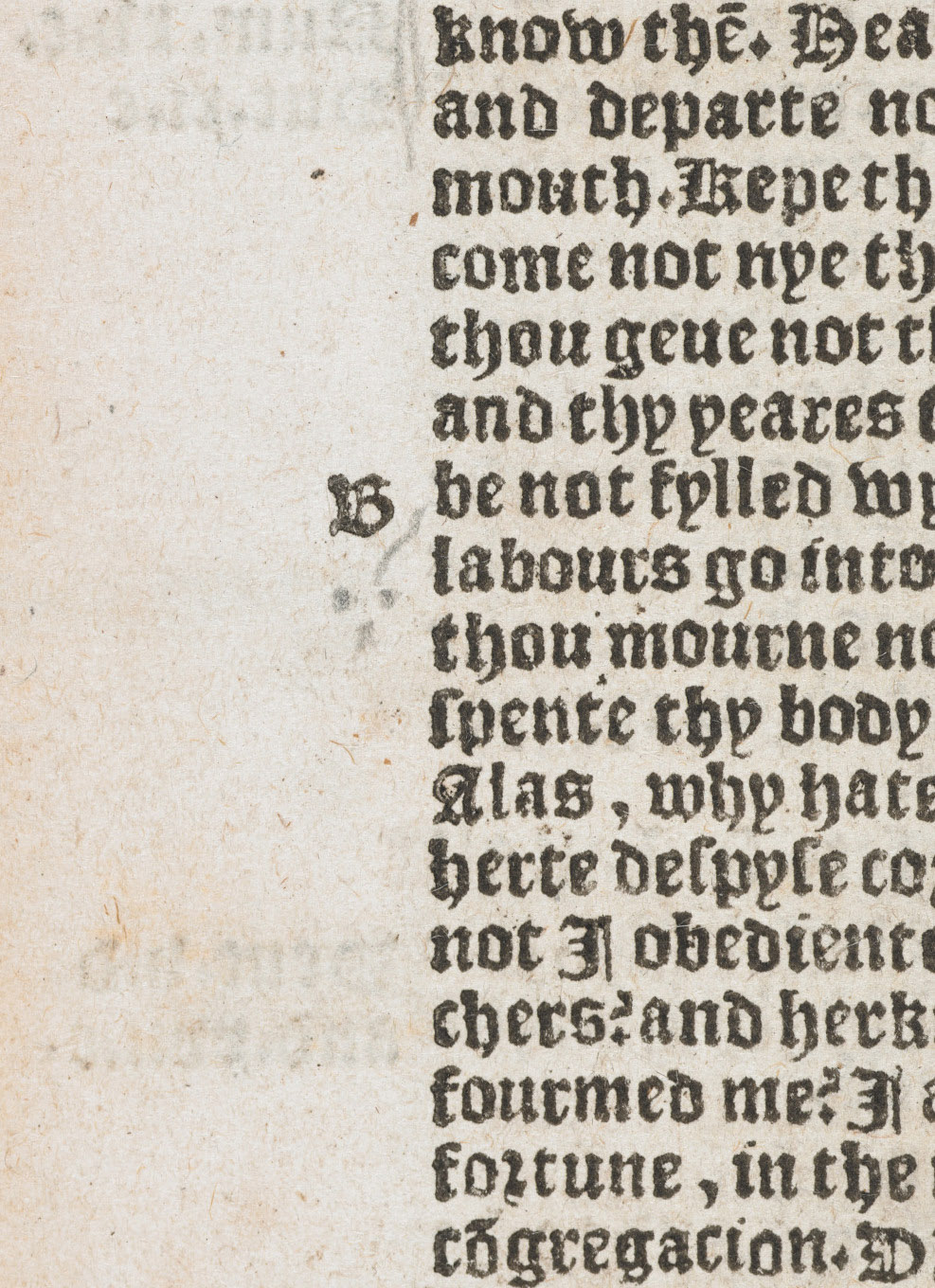

“The Fifth Psalm, For the Obtaining of Godly Wisdom” is the most heavily annotated psalm in the volume. There are six graphite manicules, two graphite trefoils, one bracket, and one ink trefoil, which means that there is at least one marking on every page opening but one. Sigs. F1v and F2v have three markings each. Henry also placed a graphite trefoil beside a verse about wisdom in “The Seventh Psalm, for an Order and Direction of Good Living.” Henry had always been interested in biblical and theological texts pertaining to wisdom, annotating similar passages in his copy of The Books of Solomon and his manuscript psalter.Footnote 108 As he read Parr's book during this time of international and domestic conflict, he clearly felt that it was imperative to call upon God for wisdom and guidance. However, as he read the “Fifth Psalm,” Henry did not annotate any of the passages celebrating the beauty of wisdom or any of the passages focusing on the approach of death. Instead, his markings focused on two sets of issues. First, he annotated verses in which the speaker begs God to purge his sins and free him from ignorance. For example, he placed a manicule beside one of the opening verses asking for purification and knowledge:

manicule 3: ☛ Give me a new heart, and a right spirit, and take from me all wicked and sinful desires.

O Lord, I am foolish, ignorant, and blind, when I am destitute of thy knowledge.Footnote 109

On F1v, he marked a similar passage in which the speaker asks God to “dwell” in his “heart” and asserts that purification from sin must precede the obtaining of wisdom:

manicule 4: ☛ O Lord God, touch my mouth, that my iniquity may be driven away;

dwell thou in my heart, that my sins may be purged.

Wisdom doth not enter into a malicious soul, nor will abide in a body which

is subject to sin.Footnote 110

Another manicule (right below it), marks a passage in which the speaker implores God to “teach” him to prevent ignorance and sin:

manicule 5: ☛ Teach me, O Lord God, lest my ignorance increase, and my sins wax more

and more.Footnote 111

An ink trefoil marks a verse that asserts the supreme value of God's wisdom and declares that a man without wisdom is worthless:

ink trefoil 1: ✢ If any seem to be perfect among men, yet if thy wisdom forsake him, he

shall be reckoned nothing worth.Footnote 112

In marking these particular verses, Henry displayed a conviction that sin was the cause of ignorance and articulated optimism that God's forgiving “touch” could dispel that sin and imbue him with wisdom, the supreme virtue during this time of crisis.

Henry also marked passages in the “Fifth Psalm” in which the speaker asks God to “teach” him the “law” so that he might be led to think and walk in the “straight way” and “please” God. These verses reveal how Henry hoped that he might translate wisdom into pleasing, godly thought and action. For example, he marked the following verses:

graphite trefoil 1: ✢ Let thy spirit teach me the things that be pleasant unto thee, that I may be led into the straight way, out of error wherein I have wandered overlong.Footnote 113

manicule 6: ☛ Would God my ways may be so ordered, that I may learn thy wisdom and thy words.Footnote 114

graphite trefoil 2 and bracket: ✢[ O happy is he, Lord, whom thou instructest, and makest learned in thy law.Footnote 115

manicule 7: ☛ Let thy wisdom rule and guide my thoughts, that they may always please thee.Footnote 116

In the “Seventh Psalm” Henry marked a similar verse about wanting to walk in the right “path”:

graphite trefoil 3: ✢ Stay and keep my feet from every ill way, lest my steps swerve from thy

paths.Footnote 117

The last manicule in the “Fifth Psalm” marks a summative verse in which the speaker explains that he has voiced his desire for God's wisdom and now resigns himself to God's mercy:

manicule 8: I have declared my cause before thee; do with thy servant according to ☚

thy great mercy.Footnote 118

In these markings, Henry acknowledges his sins, but also charts a way forward, asking God to teach him wisdom and actively guide his thoughts, steps, and future actions.

These markings in the fourth, fifth, and seventh “Psalms” provide fascinating insight into Henry's thinking in the tumultuous last years of his life. As noted above, I read these markings as newfound examples of Henry's personal and performative reading and writing, and I argue that they demonstrate his timely engagement with physical suffering, sinfulness, divine wisdom, and human action. Most importantly, these markings are found in a gorgeous, high-profile book produced by his wife, rather than in a book produced by an ancient or Continental author with whom he had no relationship. As such, each marking invites the reader to consider the triadic relationship between Parr-text-Henry; in this regard, the markings are especially valuable because they shed new light on the vital role that Parr played as queen/author, both in forwarding Henry's cause and in facilitating the fulfillment of his monarchical and spiritual duties. Henry clearly valued Parr's labor, seizing on the opportunity to speak to God as a new David/Solomon, and by leaving a visible record of his engagement with her book he offered a valuable countergift in return.

CONCLUSION

The extant deluxe copies of Parr's Psalms or Prayers offer valuable insight into several areas of early modern court culture. In conjunction with the expenses from Parr's chamber accounts, the volumes reveal that Parr was a multifaced author who saw her books through the press and oversaw the production of beautiful gift copies. The deluxe books highlight the fact that Parr was an author/consort who played a key role in the exercise of monarchical power and the display of monarchical piety during a time of crisis. The copies in the Elton Hall Collection and in the Wormsley Library are particularly important because they provide evidence of Henry's engagement with Parr's text and illuminate the complex textual exchanges that took place between a king and queen who read and wrote for each other. Future studies of the three other giftbooks (at Exeter College, Oxford, the Bodleian Library, and the University of Illinois) will add to our understanding of the book's production and reception. Finally, future studies might examine the influence of Parr's giftbooks on the famous books produced by Princess Elizabeth for Parr and Henry as New Year's gifts in December 1544 and December 1545.Footnote 119 Elizabeth's books are gorgeously bound with hand-embroidered covers, and the dedications reveal Parr's literary influence. I suggest that Parr was the mentor who inspired and initiated Elizabeth into the ritual practices of early modern gift exchange, and that her books served as a model for Elizabeth's.