Prelude: Realities of Our Current World

I write this address in the latter part of 2020, when we are traversing a period of historic proportions with a global pandemic not experienced since 1918. There is overwhelming exhaustion in attempting to carry out even the mundane work that preceded this COVID-19 moment. For many of us, the work has been compounded by taking care of elderly family members, “homeschooling” our children through online learning, leading and assisting our institutions in being responsive, and trying to maintain a semblance of mental wellness (even with the heavy toll of the death of loved ones for some of us). The relevance of teaching and researching in this pandemic moment has taken on new meaning.

These conditions have occurred on top of the political turmoil of the past four years, with a presidential administration determined to undermine democracy at every level. On the morning of the History of Education Society (HES) Presidential Address on November 7, 2020, the Associated Press declared former vice president Joe Biden the winner of the presidential election, with former senator Kamala Harris as the first Black and Asian female vice president. The sitting president has yet to concede and has employed numerous divisive tactics, including lawsuits, to declare the election results fraudulent, despite all evidence and court decisions to the contrary. The election results have also revealed the racial fault lines that have divided this country. COVID-19 has also served as a stark reminder of racial disparities and the disproportionate toll on communities of color with respect to deaths, lack of access to basic health care, and continued glaring inequities in housing and education. The United States has more than 13 million cases of COVID-19, record levels of positive cases reaching well over 200,000 on some daily counts, and over 260,000 deaths. The failure to address the pandemic under the Trump administration has amplified needless human suffering.

Adding to this, we have witnessed the rise of global protests over racism against Blacks and systemic inequalities heightened by the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor throughout the summer months, marshaling new and renewed calls for permanent reforms in all facets of society. Even in rural White America, pockets of protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement have surfaced. There was no shortage of organizational statements denouncing inequality and racism. The HES's statement reiterated our long-standing commitment to transformative and inclusive scholarship:

In this global pandemic, amidst the tragic loss of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor and countless persons whose names we may never know, we write to affirm the centrality of #BlackLivesMatter in our past, present and future. Our work over the decades has shed light on those dark moments when the promises and possibilities of equality under the law were anything but equal. Our scholarship has shown evidence of human agency and resistance in the face of extreme circumstances, honoring individuals and groups who seized access to literacy and schooling in the face of threats to life and the dissolution of communities. This moment is a reminder of the import of our work, and it inspires us to do more, as established and emerging scholars, teachers, and mentors and citizen scholars. We can tell new stories, offer new historical interpretations, and help all of those in our midst make connections between the past and present. As we do so, we recognize that this history is deeply personal, as mothers, fathers, siblings and friends are living it now, in this very moment.Footnote 1

Since the society's inception, our research as historians has demonstrated and evidenced disparities in educational opportunities and outcomes. We have also traced the historical origins of this imbalance to contemporary policies and practices, where we are witnessing continued, glaring inequalities, not just in the United States but around the world. Thus, I am imploring us to work collectively and systematically to dismantle institutional practices intentionally designed to maintain systemic inequality by building a new institutional order.Footnote 2 Perhaps it begins, first and foremost, with a critical reflection of our own complicity in this process, embedded in historical traditions designed for certain groups of students to fail. All of us have been beneficiaries, but with varying degrees of privilege. Thus, my approach in this address is to facilitate a process of inner reflection toward outward action. I draw from scholarship in the fields of history, education, ethnic studies, sociology, and philosophy as well as revisit primary sources to lay out an argument for why confronting racism-blind and “racist-blind” institutional practices is necessary and long overdue, especially in our role as educational historians. What I offer today is a conceptual reframing to help make sense, at least for me, of what has resurfaced in this dual pandemic moment of COVID-19 and systemic racism. Professor Edmund Gordon's inspiring words at the opening plenary of the annual HES conference, offered online, was a clear indication of where more work needs to be done and why.Footnote 3 This unconventional year calls for an unconventional address.

The HES at Sixty: Reflection, Renewal, and Rebirth

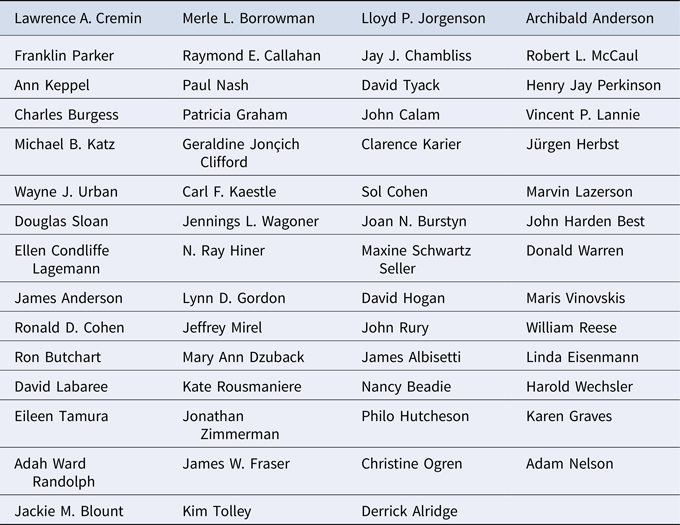

The year 2020 also marks an important milestone in our society's history with the sixtieth anniversary of its founding. I was reminded of this significance in recalling how within certain East Asian cultures (including my Korean family), one's sixtieth birthday is not only a time of grand celebration but one involving deep reflection on a life (hopefully) well lived. The shared, communal experience of a sixtieth birthday opens up promises and possibilities for renewal and rebirth—to pave a new path for the next generation. In acknowledging our society's history, represented by the previous fifty-nine presidents listed in Table 1, we stand witness to how much HES has been on the forefront of generating and disseminating new knowledge, and how each successive president's path has led to our organization's vibrancy.

Table 1. The First Fifty-Nine Presidents of HES (in order, from left to right)

To be in such company fills me with great awe and humility. But it is a reminder of how much more work needs to be done and where we must lead to make history of education scholarship crucial in offering solutions in this deeply inequitable educational system.

“They're being racist-blind, not color-blind!”

Evening rituals in my household often entail certain members delaying the inevitability of going to sleep, to which I am sure many of you can relate. For some reason, my children have used such “downtimes” to engage in probing existential questions about the meaning of life and, more often than not, why racism, sexism, and inequality persist in our society. My initial responses have included the typical big sigh and asking why they couldn't have asked these questions during the day or at dinner when ample opportunities existed. It has, however, become a tradition that I have come to cherish, albeit tinged with exasperation.

One evening two years ago, my children, then ages fourteen and ten, were discussing daily occurrences in their respective schools in which they observed disparate treatment of mainly African American students by teachers and school administrators. They recalled this being a common occurrence throughout their school years, starting with kindergarten. This particular evening, as I attempted in my usual manner to explain the effects of educators being color-blind, all the while operating with implicit biases, I noticed that my son was actually listening and processing, and growing viscerally angry. As I continued in my professorial manner, he suddenly exclaimed loudly, “They're not being color-blind, they're racist-blind! They are blind to their own racism!” I was taken aback at his astute analysis, which revealed the systemic roots of racism and where the color-blind ideology fell short. What he so aptly understood as a fourth grader was the seemingly benign nature of how claiming color-blindness excused one from owning systems of privilege and racism in everyday life. A ten-year-old pointed out why color-blindness was never an accurate way to describe the structural realities of inequitable school systems and those who have been educated within them. To also acknowledge the honest appraisals of our youth, we must focus on a way to decenter the language and thought of color-blindness toward recognizing “racist-blind” mindsets and working to redesign our systems of practice.

“Racist-Blind” by Design: The “White Racial Frame”

In a recent National Public Radio TED Radio Hour entitled “Designing Our Lives,” Debbie Millman of the School of Visual Arts in New York revealed that societies, and essentially our realities, are built on foundations of design that were always intentional.Footnote 4 Visual symbols have been attached to specific meanings about our cultural resonances throughout time and space and reveal processes of group identity formation. In essence, Millman argues this is how cultures are “read” and understood.

Even though Millman was addressing the history of design through logos and branding in popular culture, I could not help but think of how our social structures were built upon the framing of storied identities through intentional design. That, in conjunction with reading anew and revisiting classic works on the history of race and racism, led me to sociologist Joe Feagin's concept of the “White racial frame” and how it is implicated in the systematic racism built into the design of US society.Footnote 5 He defines it as “an organized set of racialized ideas, stereotypes, emotions, and inclinations to discriminate. This White racial frame generates closely associated, recurring, and habitual discriminatory actions.”Footnote 6 It speaks centrally to the intentional design of our political, economic, and social systems in maintaining a racial hierarchy.

Nothing is new about this historical framing, at least to many of us, but the recent attention to systemic racism and inequality as “what's trending,” even among colleagues in academe, leaves me perplexed. In a sense, the White racial frame has insisted on a “racist-blind,” and not a color-blind ideology to persist. Color-blindness is rooted in an assimilative structure that focuses on individual behaviors and choices, without fundamentally addressing the power and racial differential habitually reinforced on a daily basis. The continued efforts, especially in education, to reinforce color-blindness as a form of racial neutrality and societal advancement, perpetuates racist-blind thinking about the intentional design of our society to accept racism as a given and natural. To question efforts to be color-blind, as all things equal and neutral, is a racist act in itself.Footnote 7 Critical race theorist and legal scholar Derrick Bell has written extensively on the permanence of racism in our legal and social systems and notes that the cloak of color-blindness continues to stall any traction toward racial progress.Footnote 8 To be sure, color-blind and racist-blind coexist, but the constant inattention to a system of racist structures inscribed in our laws, policies, and social customs maintains that discrimination is individual and personal, not systemic.

Contributing to a racist-blind system built on the White racial frame can also be seen as an extension of racial formation advanced by sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant. Their book, Racial Formation in the United States, highlights the significance of the category of race as a social construct that is shaped and reshaped over time depending on the particularities of the social, political, and economic landscape. The process of racial formation is produced through racial projects (for example, school systems) that become inscribed and practiced through our everyday customs and interactions.Footnote 9 What is pervasive, to reiterate Bell's argument, is the way “race” and racism shapeshift to maintain Whiteness as the default structure of standard operations. Here I am reminded of the citizenship cases of Takao Ozawa (1922) and Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), who contested, and lost, arguments over racial classification of Whiteness and Caucasian status in attempts to gain naturalized citizenship. The courts’ decisions, however, rested on “common sense” definitions of race, concluding that their phenotypical features would clearly render them as not White.Footnote 10 Racism and Whiteness, as historian Erika Lee notes in America for Americans, also operates within the history of xenophobia in the United States and the ways it becomes entangled with who deserves citizenship. While xenophobic attitudes against certain European groups surfaced, they were quelled in short order as these groups became absorbed into the White populace, as in historian Noel Ignatiev's account of the Irish.Footnote 11 Nell Painter also brings this into sharp relief through her insightful analysis of the historical formation of Whiteness and power (in also ascribing beauty and intelligence) throughout Western civilization and of its transmogrification to US society.Footnote 12

And certainly that the foundation and design of our society were built from the global slave trade is a matter of history and record. Historian Andrés Reséndez details how colonial territorial expansion became fueled by “the other slavery” with the enslavement of Indigenous populations throughout the Caribbean, South and Latin America, including Mexico, and into the US territories.Footnote 13 Settler colonialism, predicated on territorial expansion and systematic exploitation of Indigenous land and labor, is as much a feature of the development of school systems to eradicate any forms of indigeneity and resultant cultural awareness.Footnote 14 Such scholarship reveals how the United States is not unique in this regard and points to how entrenched systemic racism was “stamped from the beginning,” as documented by Ibram Kendi and other scholars on race.Footnote 15 But how educators, paralyzed by White fragility, still shun and shy away from these historical facts, as Robin DiAngelo advances, especially in teaching about our nation's past, poses an imminent threat to building democratic ideals and citizenship.Footnote 16

W. E. B. Du Bois makes this painstakingly clear in confronting our racist past and present within public schools. His 1935 essay, “Does the Negro Need Separate Schools?,” published nearly two decades before Brown v. Board of Education, offers an indictment and a cautionary tale for northern schools and institutions of higher education, where the operationalization of de facto segregation revealed a condition so harmful to African Americans that attaining a “proper education” in that current context could never be achieved.Footnote 17 Du Bois knew full well that the system of the White racial frame in a future desegregated South would yield devastating results, with the loss of an educated workforce of Black teachers and administrators, and that the lives of nearly four million school-age children would come with dire consequences for generations. Du Bois's conceptualization and plea for a “proper education,” was comprised of:

Sympathetic touch between teacher and pupil; knowledge on the part of the teacher, not simply of the individual taught, but of his surroundings and background, and the history of his class and group; such contact between pupils, and between teacher and pupil, on the basis of perfect social equality, as will increase this sympathy and knowledge; facilities for education in equipment and housing, and the promotion of such extra-curricular activities as will tend to induct the child into life.Footnote 18

Described nearly a century ago, Du Bois's conception carries continued meaning in today's context. The design of a school system that is culturally relevant, responsive, and sustaining, and that foregrounds the student's needs with a well-trained teacher vested in the whole life of the child and their community, has been well-documented in contemporary educational research.Footnote 19 Why was Du Bois not recognized as a central intellectual figure in educational theory and thought like John Dewey, and especially within the history and philosophy of education, where the two might be read in conversation with each other? Derrick Alridge's The Educational Thought of W.E.B. Du Bois: An Intellectual History is an important corrective in centering Du Bois within education.Footnote 20 To reposition Du Bois's question about separate schools, I would also question why we persist on providing an improper education to our students of color. What are the ways we continue to extend miseducative experiences to our schoolchildren, as Dewey notes in Experience and Education, written in 1938, during the same time period?Footnote 21 Why are we (willfully) operating within a deeply flawed design?

“Schools Are Doing Exactly What They Were Designed to Do”

James Anderson would often recall that, as a doctoral student at the University of Illinois, he and David Tyack, then a faculty member, often engaged in conversations about the history of education and why inequality, especially along racial lines, continued to persist. According to Anderson, Tyack's usual response in such instances was, “Schools are doing exactly what they were designed to do,” and that we should not be surprised at the results. In that vein, schools were intentionally designed to be inherently unequal institutions, and we have been conditioned to accept the White racial frame as a given and “natural.” It is the dual system of schooling that historically, and presently, educates a privileged group for democratic citizenship and all others for second-class citizenship in the ways that Anderson so starkly documented.Footnote 22

The structure of school systems formally established since the common school era were predicated on adherence to a pan-Protestant ideological citizenship based on republicanism, capitalism, and Whiteness (as property) granting entitlements to those deemed worthy.Footnote 23 The design of common schools, because they expressly had to invoke a common system to tame the growing diversity of European ethnic groups, included elements of what should and should not be taught in schools, which extended to those topics deemed too controversial or taboo. The fact that our educational and workplace organizations still have difficulty broaching subjects like race and racism is a result of intentionally evading critical conversations. A common refrain I hear from my doctoral advisees, many of whom work in schools as one of the few diversity and equity advocates, is that teachers and administrators are unequipped to talk about racism and systemic inequality—they were never taught how to address it in their teacher or school leadership training. Even in K-12 schools where Black and Brown students constitute the majority, my students also reveal the systemic unwillingness to question the basis of deficit-based thinking and practices.Footnote 24

Schools function in the ways they are designed because they reflect a deeply fractured society steeped in racism-blind practices. Everyday acts of “mundane racism,” which David Garcia, Tara Yosso, and Frank Barajas have detailed in their historical analysis of how school segregation in Oxnard, California, was able to persist as an acceptable and preferred system by Whites, further reifies the normativity of the White racial frame.Footnote 25 Such mundane racist practices, enhanced by the design of municipal systems, also allowed for the deleterious and generational persistence of unequal schools, both public and private.Footnote 26 The continued segregation of schools in cities such as Chicago, especially in the post-Brown era, which sociologists Loïc J. D. Wacquant and William Julius Wilson have termed hyperghettoization, has resulted in an extreme concentration of a Black and Brown “underclass” where disparities in housing, employment, health care, and schools have been exacerbated, and where the suburban growth of Asian “ethnoburbs” have surfaced.Footnote 27 Such policies as “benign neglect” to appease White interests and evade any further attention to civil rights and racial issues in society is also a matter of historical record enmeshed in the evidentiary trail of intentional mismanagement.Footnote 28 In essence, such a doctrine of benign neglect can be extended to the functioning of school systems (of which there is nothing benign).

Tinkering toward Dystopia?

In this section, I take a cue from Tyack and Larry Cuban's Tinkering toward Utopia to indicate how those of us in schools and colleges of education have been contributing to a system where tinkering toward dystopia has become the norm.Footnote 29 If it truly were about creating utopia through effective educational reforms, why have we yet to witness such systemic changes? In that respect, it is the constant tinkering that prevails. This is not to discount improvements in academic achievement rates, judged by standard measures, in isolated pockets, but they continue to exist as outliers. Certainly, as Tyack and Cuban would assert, the intricate ways that educational reform and policies are entwined and layered in complexities at micro and macro levels of society impede substantive progress. Likewise, our work within schools and colleges of education is embedded in organizational and hierarchical systems that privilege certain types of research and knowledge production over others, particularly where scientific research reigns supreme.

Teaching and Teacher Education in Schools and Colleges of Education

The historical development of normal schools and the resultant teacher education programs were fraught with ideological tensions over the means of teacher preparation, establishing a professionalized workforce, and their “place” within institutions of higher education. Even within the more prestigious, research-intensive universities, education was designed to occupy a lesser status, gendered work notwithstanding. Scholars such as Jürgen Herbst, Ellen Condliffe Lagemann, Chris Ogren, David Labaree, James Fraser, and Lauren Lefty have detailed the institutional, political, and local responses in the ways that schools and colleges of education, educating a predominantly White female teaching force, navigated the precarity of their existence struggling to legitimize their standing in research and practice.Footnote 30 This would extend into decisions over who would become ideal teacher candidates and where conversations over quality and merit ensued. For teacher candidates of color, and northern Black teachers in particular, being identified as “ethnically qualified,” as Christina Collins indicates, created barriers to full consideration and access to teaching careers in cities such as New York.Footnote 31

With the path to school leadership heavily dependent on veteran teachers, the limited routes to promotion and career advancement becomes curtailed even further. Where logically the White female teaching force would transition into school administration in disproportionate numbers, what we find over time is the “natural” role of White, cisgendered, heterosexual males to occupy school district leadership ranks, especially with the rise of bureaucratization during the Progressive Era. Kathleen Weiler, Kate Rousmaniere, Jackie Blount, and Karen Graves provide groundbreaking accounts of female schoolteachers and leaders whose professional and personal identities threatened the gendered norms of acceptability.Footnote 32 Career advancement for White males whose sexuality and marriage status came into question would also be stalled. Here, too, the White racial frame dictates strict adherence to archetypal ideals of teaching and school leadership that are heavily gendered and heteronormative. There is very little room for deviance.

It is no surprise then that we still maintain a relatively homogenous teaching force. The latest demographic data on public schoolteachers in the United States from the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) for 2017–2018 indicates that 79 percent of schoolteachers were White and non-Hispanic. About 9 percent indicated Hispanic origin, and 7 percent identified as Black and non-Hispanic. Even more dismal are the 2 percent of teachers identifying as Asian and non-Hispanic, 2 percent reporting as two or more races and non-Hispanic, and less than 1 percent as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic and American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic.Footnote 33 While it might be considered slightly encouraging to find teachers of a given race or ethnicity to teach in schools where the student body matched that of the teachers, by and large, in schools where the majority of students were not White, the majority of teachers tended to be White. The teaching force as a whole employs approximately 77 percent females, with that trend growing.Footnote 34

The overall student racial demographic in the public schools witnessed a decline among White students from 61 percent in 2000 to 48 percent in 2017. In that seventeen-year timespan, Black student enrollment declined from 17 to 15 percent, Hispanic students increased from 16 to 27 percent, Asian students increased from 5 to 7 percent, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population held at 1 percent, with limited information for Pacific Islander students.Footnote 35

How we work toward creating a more diverse teaching and school leadership workforce rests on an intentional, shared commitment by those of us in decision-making positions in schools and colleges of education. We can decide who gets into teacher education and who becomes a teacher with a strong foundational basis to offer a “proper education.” Julie Gorlewski and Eve Tuck's edited book provides contemporary case studies for reimagining possibilities where schools of education can lead and be sites of resistance in questioning the neoliberal basis of state licensure requirements and edTPA as a teacher performance assessment.Footnote 36 We know that ancillary or alternative pathways to diversify the teaching force, such as Teach for America, Call Me MiSTER, or Grow Your Own programs, do not fundamentally change the structure of everyday operations in teacher education programs. We also know from history that what began with great intentions, like the National Teacher Corps (NTC), became diffused and challenged from the start. Bethany Rogers offers an important account and a reminder of how educational innovations such as the NTC can be mired in the ways we have constructed and approached the preparation of teachers, where low-income students and students of color bear the brunt of inequitable schooling conditions.Footnote 37

Limitations in Educational Research and “Racist-Blind” Thinking

On the breadth and scope of educational research, where I point to the American Educational Research Association's various publications, there have been marked improvements in addressing a range of social and educational inequalities from multidisciplinary research methodologies. Certainly, there is no shortage of scholarship on race in education. What must be done better, in my humble opinion, is to question the framing of educational research that now maintains a Black/Brown vs. White/Asian binary. I do not mean to diminish or dismiss the stark realities of what we have witnessed in terms of resegregation of urban and suburban sites and the glaring opportunity gaps therein, as revealed in the works of Linda Darling-Hammond, Erica Frankenberg, and Gary Orfield.Footnote 38 My concern rests with the incomplete picture of how the achievement or opportunity gap is framed that leaves unquestioned the perpetuation of binary thinking.

A clear instance of this comes in extending an uncritical, a priori view of Asian and Asian American students as the academically successful model minority. While researchers in multiple academic disciplines, including education, have been debunking this stereotype for decades, it stubbornly persists in K-12 through higher education, where admissions policies have been fought in the US Supreme Court.Footnote 39 Despite recent research by critical quantitative scholars to provide nuanced, disaggregated data among various Asian American ethnic groups and academic achievement, it is more convenient to believe in Asian American student success (primarily from East and South Asians) while at the same time believing in Black and Brown “deficiencies.”Footnote 40 The convenience of adopting culture-based arguments of why certain minority groups achieve and others do not is also a condition of the White racial frame and racism-blind ideology in that academic achievement is tied to a group's “cultural” or familial disposition to value education and is not a feature of systemic racism. This logic also extends to explaining the dearth of Asian American teachers, for example, in that such aspirations, or lack thereof, are more culturally rooted rather than a feature of historical and structural barriers.Footnote 41 Culture-based arguments for group deficiencies also contribute to forms of anti-Black and -Brown racism even within racial minority populations.

An important corrective comes in critical disaggregation of quantitative data for groups, such as Asian and Asian Americans, where particular subgroups and ethnicities have markedly distinct histories and experiences that contest notions of academic achievement. At the same time, questioning the basis of how racialized student populations are “counted” and considered “statistically insignificant” in the case of American Indian college students, with the continued invisible rendering of Indigenous populations, remains highly problematic and must change.Footnote 42 The ways we design educational research through such normalized language matters and must be aligned to accurately acknowledge the full humanity of historically marginalized populations.

Questioning “Racist-Blind” Practice in My Own Research

While it might be tempting to underscore the ways that other educational research has neglected to question the means with which “racist-blind” ideology operates in designing research, especially in assuming deficit characterizations of our youth of color, I refer to my own limitations. Here I have been influenced by Rousmaniere's essay in the History of Education Quarterly on the disabling of history, and how a rereading of her groundbreaking book on city teachers in New York revealed the extent to which she ignored the physical toll of teaching.Footnote 43 The accounts of former schoolteachers spoke volumes and made explicit the bodily demands of teaching, yet was left underanalyzed and “persistently avoided” until Rousmaniere engaged more with theories in disability studies and personally recognizing the physical limits of aging. While the vocal expression of ailments went largely unheard at the time, researchers also have a role in becoming more attuned to historical silences and the silencing of history among racialized populations. I point to K. Tsianina Lomawaima's essay on the deafening silence within her own family's history and how that shaped the stories that were told and left untold after revisiting the gaps in her previous research.Footnote 44

In an essay review in HEQ of my book on Seattle's Japanese American students during World War II, historian Roger Daniels pointedly brought up an “obvious” question that I neglected to consider throughout my research.Footnote 45 How could I have claimed a school district as so progressive and responsive to its diverse student body yet be blind to the fact that there was not one teacher of color? Or at least fail to mention this fact? How was I researching and writing about race but not laying out the operating structures of racism in the school system?Footnote 46

My own racism-blind view inhibited me from seeing the absence of Black teachers, or other teachers of color for that matter, in the Seattle Public Schools. My presumption was that they were all White (and perhaps “all right”?), and to question such “normal practice” would have been futile, as teachers of color were nonexistent. And that when they are “found” in the historical record, it appears as an anomaly, despite the evidence of African American teachers in the South. Evidence would suggest that among men and women of color there was always a desire to teach, but that the system of schooling barred their entry into the profession.

That glaring omission revealed my inability and immaturity to see and look for evidence in that regard. Essentially, there were things I did not want to see because I wanted to believe in the inherently progressive nature of the Seattle schools within a majority White system. Certainly, there are historical indicators and evidence of Seattle as a progressive city: feisty Bertha Knight Landes as the first female mayor of a major American city (1926–1928), an important site of the organized labor movement, and the first school superintendent to resist the encroaching rise of administrative progressivism.Footnote 47 White liberal progressives have played significant roles in the city and, subsequently, school district governance. At the same time, de facto segregation of neighborhoods and policies to maintain the White racial frame remained a stabilizing feature, where the convenience of not attuning to multiracial divisions prevailed.

In further review of ongoing research on intercultural education in the public schools, where Lauri Johnson and I have come to a more expansive understanding of its formation from the early through the late twentieth century, I have begun to re-examine the same set of archival sources for evidence addressing structural equality in the schools.Footnote 48 To be sure, a great deal of intercultural education efforts concerned changing attitudes and revising curricula to incorporate the cultural contributions of immigrants, voluntary and “involuntary” (in reference to slavery in certain curriculum materials), especially by noted educators such as Rachel Davis DuBois, Stewart Cole, and William Kilpatrick. But where attempts at reform expanded the confines of the classroom to address whole school systems, including hiring one or two African American teachers, it was met with quick public outcry.Footnote 49

Historical Reimaginings to Redesign a New Education Reality

What if our public schools in this post-Brown era maintained even a fraction of the estimated 40,000 Black teaching force in the segregated South, where our Black students would be beneficiaries of a “proper education”? How might the heroic lives of teachers such as Horace Tate, whom Vanessa Siddle Walker so beautifully captures, have been openly celebrated rather than being forced to hide in the shadows of Jim Crow?Footnote 50 How might our current conceptions of academic achievement, suspension, and dropout rates be approached otherwise? As an undergraduate history student, a cardinal rule of historical analysis was that one should not engage in “what ifs,” as such speculation does little to change the course of history. I suspect such outmoded ways of thinking have subsided over the course of three decades, as how are we to imagine a more egalitarian and democratic future if we don't question what might have been?

James Baldwin's 1963 essay “A Talk to Teachers” reminds us in its opening paragraphs, amid growing civil unrest, for teachers to take seriously what it means to teach for democratic civilization versus barbarism. On the one hand, education's ideal is to bring forth individualistic thinking and identity development, while on the other, society has been designed to quell those who actively seek it, as Baldwin notes:

But no society is really anxious to have that kind of person around. What societies really, ideally, want is a citizenry which will simply obey the rules of society. If a society succeeds in this, that society is about to perish. The obligation of anyone who thinks of himself as responsible is to examine society and try to change it and to fight it—at no matter what risk. This is the only hope society has. This is the only way societies change [emphasis added].Footnote 51

Baldwin's call is to arm ourselves against racism and the continued violence aimed at Black bodies and minds, and to make explicit how the system of inequality that has been designed to maintain the White racial frame, including our schools, requires a thorough overhaul. Otherwise we face extinction.

In more contemporary thought, Baldwin's words extend to what philosopher Maxine Greene notes as “the possibility of looking at things as if they could be otherwise,” and learning to think otherwise, where the power of hopeful, imaginative thinking forms the basis and necessity for human flourishing.Footnote 52 Baldwin brought this notion to bear decades earlier to underscore that humanity's survival depends on what I would phrase as teachers teaching to be otherwise. But yet how many of us teaching in teacher education and other licensure programs see this reflected in the day-to-day operations of our respective programs? How much time and energy are spent in efforts to comply with state regulations that are also deeply flawed? What danger still lurks if we were to take W. E. B. Du Bois and Baldwin seriously to redesign school systems to be otherwise?

On this, I acknowledge where efforts have taken place to research otherwise, and where our field has fundamentally changed the landscape of educational research. I reference a few since the 1980s through the 1990s where histories of African American, American Indian, Latinx, and Asian American student populations paved the way for more complex stories that have become increasingly interrelational in scope.Footnote 53 Fuller inclusion of the ways global imperialism and colonialism interacted with race, gender, class, and sexual identities are injecting much needed antidotes to isolated and binary studies of educational research.Footnote 54 Only through continued researching to be otherwise can we reimagine new possibilities to redirect educational research.

University of Illinois, 1930s-1950s: Multiracial Education Students Destined for Erasure

For over twenty years, I have possessed a small set of nearly three dozen microfiche documents containing information on teacher candidates at the University of Illinois from the 1930s through the 1950s. While this in itself sounds rather mundane, I offer a retelling of these teacher candidate files that I find quite extraordinary, especially as the microfiche, along with hundreds of other historical teachers’ files, were destined for the university's incinerator. The Educational Placement Office (EPO) at the time received campus approval to remove and burn all historical files in its possession, mostly due to privacy laws, but also because they were taking up valuable office space. Only scant information would be recorded in a database, such as names, dates of attendance, program areas, and maybe where they did their practicum. An employee, whose job was to enter students’ information in a database, noticed something curious about the names and faces on the microfiche. Not only was he captivated by the students’ years of attendance (from the 1930s through the 1950s), he was struck by their physical appearance, as they were African American and Asian American/Asian students seeking teaching positions within K-12 schools and higher education. Recognizing the import of these “hidden figures” destined for permanent erasure, he salvaged all the microfiche that he could acquire and secured them inside his shirt. During his lunch break, he came up to my third-floor office of the Education Building and placed on my desk a small stack of student microfiche files. Not quite certain why he would have such materials in his possession, he told me to take a look. An initial glance at these historical materials left me with more questions and a growing excitement, but also uneasy and angered as well, especially after he informed me that they were destined to be burned. My first response was incredulity at how the staff failed to realize the historical value of the materials slated for permanent destruction and especially where students of color were represented in our college's past. How was this allowed to happen? Being that type of researcher, I walked down to the EPO office and offered to take all the teachers’ files and store them securely in the basement of my home (not knowing if there would be enough space to house them)—unable to accept the fact that such valued materials would be forever unattainable. I asked further about university archives as a possible depository, but the director of the office stated that the libraries were not interested. Despite my persistence, there was nothing more to be done. The protocol for destruction was in place. Feeling a sense of defeat, I went through a period of mourning for those lost files that represented the lives of teacher candidates who had expressed a deep desire to teach. The mourning was more pronounced for those teacher candidates of color who, at that time and even now, were so rare in our public schools. How many more of them were there at the University of Illinois as well as beyond?

Those thirty-one files in my possession, thanks largely to the individual who recovered them (and who happens to be my spouse), have remained hidden in my office for nearly a generation. I did not know how to conduct research on subjects who weren't supposed to be written about with documents that were not housed in officially sanctioned spaces. It seemed methodologically daunting at the time, as an assistant professor whose tenure clock would not have supported the longer time it would take to work through these challenges. But also thanks to graduate research assistants throughout this time, some progress was made to lend additional context.Footnote 55

The passage of time does afford certain advantages of perspective and wisdom as one ages with the research. My own process of “reading” the students’ files came from assumptions about who the teachers and supervisors were—but is now being questioned. Intermittent conversations with James Anderson about the history of the university and its faculty within the College of Education widened my field of vision (and where talking about historical research has become a luxury). Being a presence in the College of Education for nearly a third of the university's existence(!), Anderson indicated that the campus and the college faculty have always had a strong progressive pulse and that their views on social issues might also have been ahead of their time. This made me reconsider my initial thoughts about the university faculty's evaluation letters for these students. Were they writing in coded language to express their support, in spite of the racism students would certainly face as K-12 teachers or university faculty? Or was their writing designed to express how these teacher candidates were “ethnically qualified”? Reading through the only known published history about the College of Education offers important institutional contexts but again, very little is provided about the lives of teacher candidates and the faculty who taught them.Footnote 56

What has clouded my judgments about the educational past, sometimes predetermined by binary thinking (that is, the rise-and-fall thesis), was that it rested mostly on Americanization and assimilation with White norms, resulting in schooling for vocationalism or separate tracks. While I do not dispute past historical works that have pushed our field into important directions, I have always felt uneasy with grand, sweeping generalizations and claims (although admittedly I might be doing that in this essay). And in rereading the data about our Illinois preservice teachers, more questions and uncertainties remain: Who were these students? Did they all become successful teachers? Which professors worked with the students? Were they guided by socially progressivist ideals? Most curious of all, why did they come to Illinois?

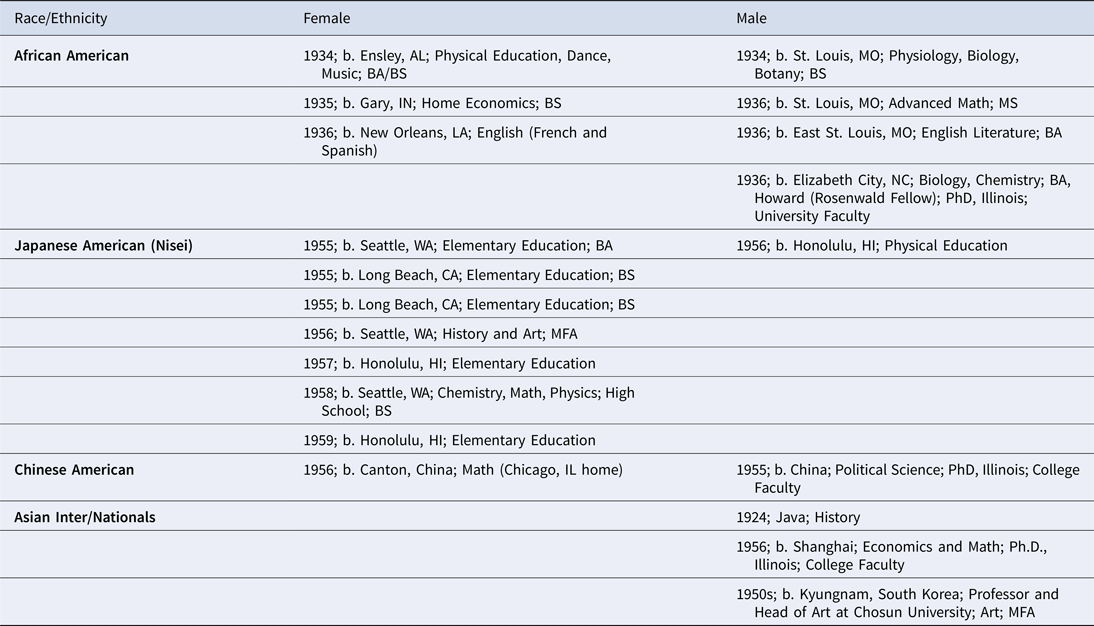

What is known about the twenty student records that I can legibly read thus far can be broken down by the following demographics: nine male, eleven female. Among the males, five are African American (one with a PhD), one is Chinese American, and two are Asian nationals (from China and Java). Among the females, three are African American and eight are Asian American (seven Japanese American or Nisei, and one Chinese American). The following table indicates where the students were born, their subject areas of study/specialty, and the degree they sought, broken down by race and gender, if indicated.

Table 2. Notes on Teachers of Color at the University of Illinois College of Education, 1930s-1950s.

Source: Files in the author's possession.

The Japanese American students who originated from the West Coast, and especially Washington State and California, describe how their families’ experiences from evacuation camps during World War II necessitated their move away from their home to places like Denson, Arkansas, and then resettlement to Iowa or Chicago.Footnote 57 While the descriptions of their wartime experiences do not provide great detail, their personal statements reflect general interest in why they wanted to teach and in what subject areas. Certainly, the effects of wartime trauma as well as “not airing one's grievances” are important features to consider in their basic statements, but it can also be interpreted as a means to focus on who they wanted to become as a teacher and why. The purpose of teaching for one Nisei female in the early 1950s was clearly formed by her experience of being born and raised in Long Beach, California; being relocated and spending four years behind barbed wire in Denson, Arkansas; resettling in Des Moines, Iowa; and finally moving to Chicago, Illinois. She writes in her statement:

I think that it is very important for children of different nationalities to experience playing and working together. If this is not possible the teacher should guide the children into a study of different people. Perhaps from this study racial prejudice, which is most often learned at home, will be overcome. I would want each child in my class to feel that he is important and capable of many things. This could be partly achieved through a joint teacher-pupil planning of what to study. Each child should be allowed to express what he would like to study. I want to make school so interesting and exciting to each child that he can't wait to get to school. I want each child to feel that I am his friend—a friend learning with him.Footnote 58

There is no specific date to indicate when this student wrote her statement, though I suspect it was near the end of her program after completing her field placement. What is known would date it to the mid-1950s. I wonder if any of her coursework in classes such as Social Foundations in Education, or the Philosophy or History of Education, addressed reducing racial prejudice in the classroom, especially as this would align with when intercultural and intergroup education were implemented in teacher education? Or did she experience such racial animosity as a student and in her practicum that she developed this teaching philosophy through those moments? For this student, she outlines what would be a critical feature of a “proper education” for a child, explicitly calling on teachers to address racial prejudice, working alongside the student to aid in their developmental growth. The supervisors’ statements offer little to extend in their observations of her teaching, other than what would be considered as stereotypical statements such as, “She is a quiet, steady worker,” “She is very quiet and reserved, not included to talk much,” and “Do know she is [a] very studious, conscientious person entirely dependable in whatever she undertakes.”

The files of African American students remain more incomplete, with no record of students’ personal statements, which would reveal so much. The female candidates represent a variety of subject areas, from music/dance and home economics to English/foreign languages, which are typical of the appropriate subject areas identified for females. The African American males with conferred doctoral degrees fit within the larger narrative of those unable to seek employment as university faculty in northern institutions, even though they were fully qualified, as also indicated by university professors’ letters of recommendations. There is every indication of them being overqualified, given their degree and training, particularly within science, engineering, and mathematics fields.Footnote 59

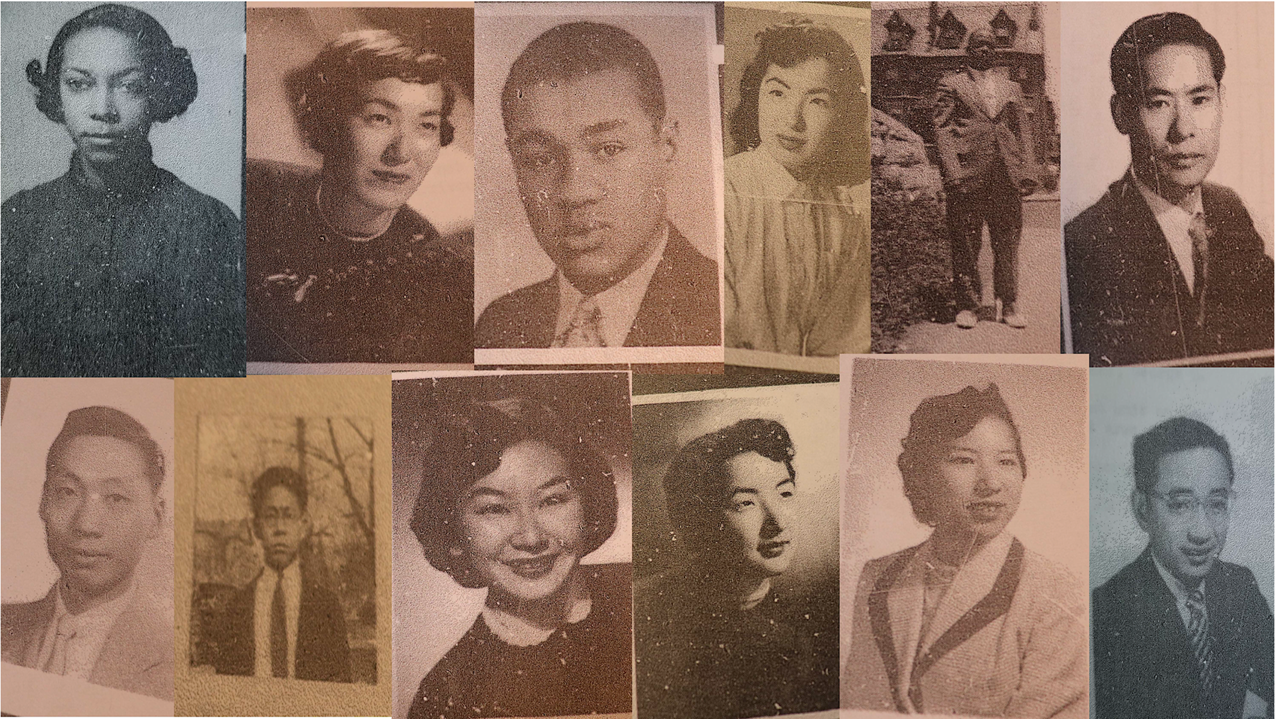

Figure 1. De-identified photos of select teacher candidates of color at the University of Illinois at the Urbana-Champaign College of Education, ca. 1930s to 1950s. Original documents in the author's possession.

Obviously, much more research needs to be done on this, and I hope it does not take another twenty years to complete. But the realities of professorial and administrative duties have led me to other paths, much of it not conducting historical research, and have added experience and perspectives I would not have otherwise gained. I especially thank my students, past and present, the majority of whom are racial minorities and not focused on the history of education, as I am a better educational scholar because of them.

Conclusion: What Do We Owe to Future Generations?

At this juncture, we have much to lose if we continue to persist in “racist-blind” practices. Our young people are pleading with us to change our ways so that they and future generations can fully exist in a world where all of them matter. Specifically, those of us in positions of influence in schools and colleges of education possess cultural capital within our respective institutions where greater attention to equity and inclusion can take place. I offer just a few examples of what can be done collectively. First, we can do better in questioning and changing admissions requirements in teacher and graduate education, for example, including test-optional provisions, while being intentional in recruitment, retention, and graduation support services. Traditional markers of academic achievement do not fully capture the potential for excellence of which some of us have firsthand knowledge.Footnote 60

Second, we must forcefully make the case for historical foundations in our teacher education programs, where such neglect over the years has come with dire consequences for democratic and civic education. Faculty trained to research and teach the history of education are central to the training of future educators. The dangers of ahistoricism and disinformation are all too real. Third, in doing so, we must also fully embrace our identities as educators and historians, resisting additional false binaries and the unnecessary insecurities that come from them. As educational historians, what and how we teach pre- and in-service educators can have immediate impact in our nation's classrooms—changes that can take place overnight. Let us not be timid in this moment, as we have wasted too much time already!

As I close out the first life cycle as sixtieth president of HES, I am hopeful about the renewed possibility of reimagining and researching “otherwise” for the next sixty years and beyond. History will have its eyes on us—how will we be judged?