A man said to the universe:

“Sir, I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation.”

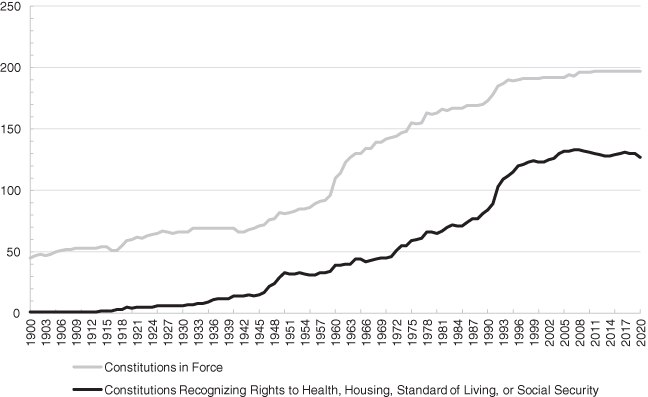

This is a book about how new constitutional rights provisions become meaningful in everyday life, moving from parchment promises to constraining institutions. It focuses on the embedding of “social constitutionalism,” by which I mean the constitutional recognition of rights to social goods, like health, housing, and social security, and the empowerment of courts to hear claims to those rights. Around the world, written constitutions have become ubiquitous. In fact, Canada, Israel, New Zealand, San Marino, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom are the only states that do not have such a document.Footnote 1 Written constitutions set out the parameters of the contemporary nation-state: who belongs to the nation and who does not, the organization and commitments of the state, and the rights and duties of citizens. While the number of rights – especially social rights (see Figure 1.1) – included in constitutional texts has increased steadily over time, rights realizations in practice have lagged behind those promises, particularly when they involve already marginalized individuals and groups.

Figure 1.1 Constitutions and social rights over time (Elkins and Ginsburg Reference Elkins and Ginsburg2021).

The transition from an unequal society to one based on a sense of obligation regarding the needs of all citizens is not a natural or inevitable one, and powerful actors often try to thwart this process. Yet, this seemingly impossible situation has been met time and time again with obstinate contestation, with people who refuse to accept this lack of recognition, with people who imagine better futures and work toward those futures tirelessly. Though the story involves macrohistorical institutional change by way of significant revisions to the core documents that outline the parameters of the state, it begins and ends with individuals. Individuals – both those who advance rights claims and the judges who respond to them – together construct and reconstruct notions of obligation, specifically the conditions under which the state has a duty to provide for the social needs of its citizens. In this book, I present a detailed study of the Colombian experiment with social constitutionalism, uncovering how new written constitutions and constitutional rights can come to be more than simply words on paper and instead fundamentally shape both social and legal life. The adoption and embedding of social constitutionalism account for the expansion of access to social goods throughout much of the world. And in a global climate defined by democratic backsliding and backlash against progressive constitutional provisions,Footnote 2 understanding the conditions under which the justiciability of social rights becomes a taken for granted aspect of political life and a widely accepted “rule of the game” becomes even more important.

Before moving forward, however, I want to offer an example of how social constitutionalism plays out in people’s lives. One Sunday afternoon in April 2017, a woman named TeresaFootnote 3 told me about her life in Agua Blanca, a densely populated district on the outskirts of Cali, Colombia. Teresa operated an informal sewing business out of her living room, and weathered as best she could the interrelated threats of violence, drugs, and economic insecurity that swirled around her. Social service provision in Agua Blanca is sorely lacking, and accessing doctors and hospitals is particularly difficult. The state’s presence appears to be limited to police officers, who – according to residents of the neighborhood – punch, kick, and shoot first, asking questions later, if at all. Teresa told me about how, after she developed a problem with her trachea that made it difficult for her to breathe, she attempted but failed to attain what she deemed to be adequate medical attention. In the midst of this difficult situation, what did she do? She turned to the courts, filing a claim to the constitutional right to health through a legal procedure called the acción de tutela, because, as she put it, “everything happens through the tutela.”Footnote 4

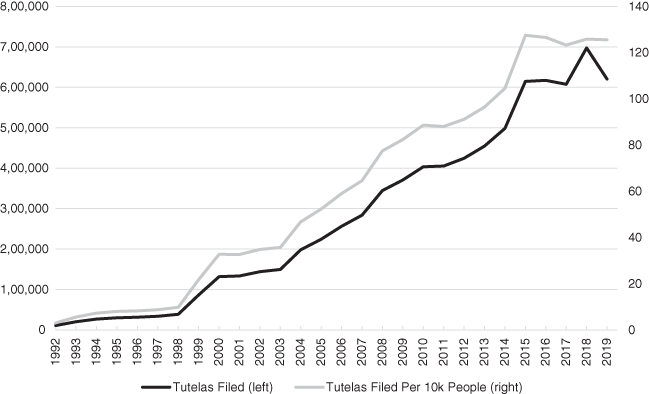

Teresa’s assessment is only a slight exaggeration. In fact, Colombians have filed almost eight million legal claims to their constitutional rights through tutelas since 1992, the year the tutela was introduced (see Figure 1.2). The acción de tutela is a legal procedure that allows individuals to make immediate claims to their “fundamental” constitutional rights before any judge in the country and does not require the service of a lawyer.Footnote 5 This has occurred in a country in which the majority of citizens routinely express little to no confidence in judges (on average just over two-thirds of Colombians, according to surveys fielded between 1996 and 2020).Footnote 6 Even more surprisingly, actors generally not associated with constitutional rights talk, such as doctors, pharmaceutical companies, and insurance companies, openly encouraged citizens to file these claims. Far from simply being words on paper, the 1991 Constitution has come to be an important part of the social fabric of everyday life in Colombia.

Figure 1.2 Tutela claims filed, 1992–2019.

How exactly did this occur? How did shifts in ideas about the law translate into substantive tools that allow citizens to make claims on the state, reshaping access to social goods in Colombia and elsewhere? More generally, how do constitutional rights provisions become embedded in social and legal life? These are the questions that this book tackles.

1.1 The Global Emergence of Social Constitutionalism

According to conventional wisdom, citizens pursue social welfare claims by voting, lobbying, and pressuring elected officials. The story goes that judiciaries are conservative bastions of the old order, perhaps valuable for advancing elite interests, but hardly useful for defending individual or group rights to social needs like healthcare, housing, and education. Further complicating the turn to law to advance access to social welfare goods, the content of social rights is often underspecified and subject to progressive realization and available resources at both the national and international levels. Yet, against the backdrop of expanding constitutional recognition of social rights, progressive and pro-status quo actors alike have engaged the law and courts in pursuit of their social and political goals. At times, social rights protections have even come to have binding influence, fundamentally reshaping the relationship between citizens and their state.

Historical accounts trace the development of legal systems and constitutional law to the changing nature of relationships within groups. Formalized law derives from informal rules fashioned to create or maintain social relationships, and this formalized law governs not just horizontal relationships between equals but also vertical relationships between rulers and those they rule. In other words, law emerged to regulate the behavior of members of a political community, limiting the relative power of leaders through a system that exchanges protection (from internal repression and external threat) for resources in the form of taxes (e.g., Tilly Reference Tilly1990), and developing standards to support economic growth (e.g., North and Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989). Others argue that those in power consent to constitutional regulation in order to avoid revolutionary overthrow (e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006) or as a response to specific electoral pressure (e.g., Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2003; Hirschl Reference Hirschl2004). None of these accounts entail a need for the state to ensure, through universal legal principles or “rights,” the basic welfare of its citizens. However, over time, understandings about the appropriate relationship between state and citizen have changed.

Specifically, the fourth wave of constitutionalism (Van Cott Reference Van Cott2000) marks a significant change in the thinking underlying the relationship between the law, the state, and the citizenry. This form of constitutionalism, which was prominent in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s, includes an expansive set of rights recognition, particularly social and economic rights, and, often, broad review powers for the judiciary.Footnote 7 Scholars have variously termed this model “new,” “social,” and “social rights” constitutionalism (Hilbink 2008; Angel-Cabo and Lovera Reference Angel-Cabo, Lovera, García, Klare and Williams2014; Brinks and Forbath Reference Brinks, Forbath, Peerenboom and Ginsburg2014; Brinks, Gauri, and Shen Reference Brinks, Gauri and Shen2015). Throughout this book, I refer to this model of constitutionalism as “social constitutionalism.”

Features of the social constitutionalist model had been around for decades – for instance, the Mexican Constitution of 1917 recognized a limited set of social rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights was drafted in 1966 – but these features only became commonplace in the 1980s and 1990s. In the social constitutionalist model, law is understood as an appropriate tool to address social ills, at least under certain conditions. At times, this shift in the function of constitutional law has been accompanied by the creation of mechanisms to allow citizens to claim their rights with relative ease.

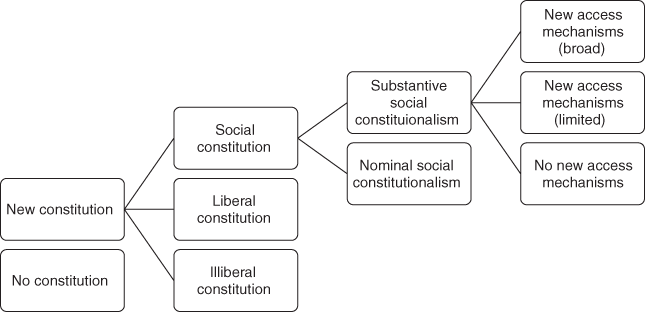

Yet, this move to a more responsive vision of constitutional law was neither uniform nor inevitable. Between 1980 and 2000, seventy-nine countries – primarily in eastern Europe, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa – adopted new constitutions. While many of the resulting constitutions fit the social constitutionalist model, not all do. Figure 1.3 represents the set of choices related to the drafting of a constitution available in the context of a transition. In the midst of an effort to refound the state (whether substantively or simply rhetorically), the initial choice is whether or not to draft a new constitution at all. The resulting constitution – if drafted – could take a variety of forms, grouped broadly as social, liberal, or illiberal.

Figure 1.3 Differentiating types of constitutions and constitutionalism.

As described earlier, social constitutions recognize a wide range of rights that indicate state obligations to the needs of citizens and allow for the “judicialization of political disputes under the social rights rubric” (Brinks et al. Reference Brinks, Gauri and Shen2015: 290). In contrast, liberal constitutions – the most common constitutional design choice in Europe and North America following the end of World War II – feature a circumscribed set of individual rights protections, offer few opportunities for contestation over social goods through the formal legal system, and tend to limit the ability of racial and ethnic minority groups to fully participate in political life (Ginsburg, Huq, and Versteeg Reference Ginsburg, Huq and Versteeg2018). Importantly, however, liberal constitutions do set out a vision of state–society relations in which the state is obligated to serve citizens’ interests. The core differences lie in whose interests count and what those interests are understood to include. Illiberal constitutions even more narrowly serve to protect the interests of an elite class and refrain from setting out a view of state obligations to the broader citizenry.

Even after constitution drafters select the social constitutionalist model, they still have a variety of choices at hand. For one, they must decide whether to recognize social rights as guiding principles (sometimes described as directives for state action) or to recognize them as justiciable, as actively claimable and contestable. Figure 1.3 distinguishes between these two forms, referring to the former as “nominal” social constitutionalism and the latter as “substantive” social constitutionalism. If a constitution includes substantive social rights protections, then the resulting question is how easy or difficult is it for citizens to make claims to those rights? We can set off additional types of substantive social constitutionalism: ones that include new mechanisms that effectively reduce the barriers to accessing the judiciary and making legal claims in a broad or in a more limited sense, and one that relies on more longstanding or general mechanisms for legal claim-making. This book presents a detailed investigation of the 1991 Colombian Constitution, which is a substantive social constitution that includes newly created access mechanisms like the acción de tutela. While the tutela procedure was initially limited in scope, over time that scope broadened significantly.

1.2 Countervailing Forces in the Early 1990s

In addition to there being distinct models of constitutionalism in play at this particular historical moment, rendering the adoption and embedding of social constitutionalism far from guaranteed, the dominant emergent economic model – understood variably as neoliberalism, market fundamentalism, or the Washington Consensus – seemed to imply an oppositional set of political and legal institutions to those implied by social constitutionalism. In both scholarly and popular usage, the term neoliberalism refers to “an overlapping set of arguments and premises that are not always entirely mutually consistent” (Singh Grewal and Purdy Reference Singh Grewal and Purdy2014: 2). Broadly, the neoliberal economic model as understood in the early 1990s emphasized a substantial reduction of the size of the state, the privatization of industries, and limits on economic and social rights protections. The Washington Consensus formally involved ten policy prescriptions (Williamson Reference Williamson2004), with the underlying idea being “to cut overall social spending in order to cut budget deficits, increase the targeting of spending by increasing means testing, decentralize spending and administration to regions/states/provinces or municipalities, and privatize the pension system” (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2012: 206). Thus, the prevailing beliefs about the most appropriate and effective economic arrangement during this time period seems to have directly cut against the social constitutionalist idea of how to organize the state and how (or whether) to moderate state–society relations. Further, this period of the early 1990s featured dramatic changes to the international system. The fall of the Soviet Union inspired a reordering of connections and alliances between countries. Neoliberalism, if only momentarily, was seen as one of the last models of political and economic life standing.

The dominant version of neoliberalism envisioned an important, but limited, role of law and courts in political and economic life. At a basic level, neoliberalism requires the protection of property rights and individual freedoms that would allow for participation in the economy. David Singh Grewal and Jedidiah Purdy (Reference Singh Grewal and Purdy2014: 9) go a step further, arguing that “neoliberalism is always mediated through law,” with respect to “the scope and nature of property rights (including intellectual property), the constitutional extent of the government’s power to regulate, the appropriate aims and techniques of administrative agencies, and the nature of the personal liberty and equality that basic constitutional protections enshrine.” While law and neoliberalism may be intimately intertwined, it is clear that social constitutionalism involves the recognition and advancement of a different kind of citizenship, a different kind of citizen–state relationship than does neoliberalism. In the neoliberal view, the law protects citizens so that they can pursue their economic interests, while social constitutionalism makes no necessary claim about the economic pursuits of citizens. In fact, under the social constitutionalist model, the law is meant to step in to protect even those, or perhaps especially those, citizens who have not succeeded economically.

In practice, however, the choice turned out not to be neoliberalism or social constitutionalism – one or the other – but how exactly these two seemingly incongruous models might come to coexist in one country. We might think of the combination of these two models as the result of an uneasy compromise between different sets of actors. Another possible interpretation is that of a bait and switch, wherein elites offer empty promises of social equality and democracy, in keeping with the overarching scripts of the time, but with no intention of making good on those promises. Yet another possibility is that of unrecognized tension between these models. This is perhaps most likely where constitution-drafting procedures are fragmented across distinct working groups. Finally, it could be that these models are not, in fact, incongruous. To the extent that both rights-based constitutionalism and neoliberalism result in the individualization of social problems and obligations, there may be less of a disjuncture between these models than originally appears. Regardless of the exact dynamics at play, what we see is that these two models did come to the fore at roughly the same historical moment, with countries at once adopting neoliberal economic policies and new constitutions that recognized social rights. Whether or not these legal visions provided any substantive protections for the individual depends on the extent to which both social constitutionalism and neoliberalism became embedded. This book tracks these processes in Colombia, and provides insights for understanding the tensions between social constitutionalism and neoliberalism elsewhere in the world.

1.3 The Argument in Brief: Constitutional Embedding through Legal Mobilization

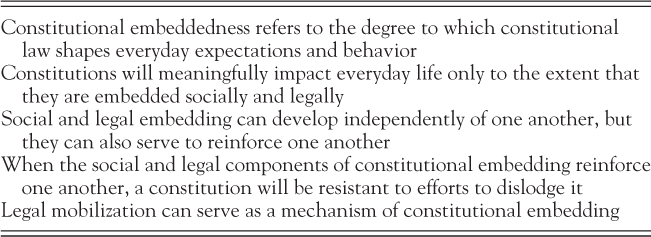

The Social Constitution introduces the concept of embedding constitutional law and documents how legal mobilization can propel constitutional embedding. Turning to the concept of embedding helps us to understand how constitutional rights become “real,” or how the promises written into constitutions come to have social and legal meaning, thus shaping the behavior of both everyday citizens and judicial system actors. Table 1.1 breaks down the argument of this book.

Table 1.1 Argument: constitutional embedding through legal mobilization

Constitutional embeddedness refers to the degree to which constitutional law shapes everyday expectations and behavior |

Constitutions will meaningfully impact everyday life only to the extent that they are embedded socially and legally |

Social and legal embedding can develop independently of one another, but they can also serve to reinforce one another |

When the social and legal components of constitutional embedding reinforce one another, a constitution will be resistant to efforts to dislodge it |

Legal mobilization can serve as a mechanism of constitutional embedding |

What exactly does constitutional embedding look like? Following the adoption of new constitutions that recognized a wide set of rights, citizens gradually come to learn about these rights, and they begin to take some of the problems in their lives to the formal legal system, experimentally. Some of the time, this experimental claim-making solidifies into general patterns in claim-making, as citizens begin to view particular issues as amenable to a legal solution and as societal actors encourage further claim-making. Simultaneously, judges’ beliefs about their own role and whether and how the law applies to social issues change, in part because of the way that legal claims and daily life combine to expose them to these social issues. As judges continue to decide cases, opportunities for further claim-making shift. In this way, legal mobilization can serve as a mechanism of constitutional embedding, with the iterative process of legal claim-making shaping how both everyday citizens and legal actors understand what the law is and does – or what the law ought to be and what it ought to do.

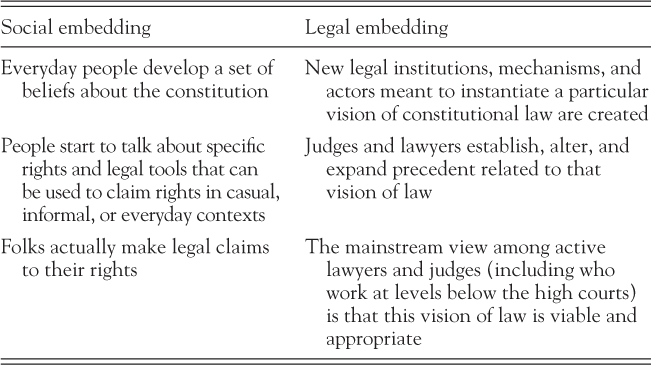

There are two distinct, but related, components of constitutional embedding: social and legal embedding. Social embedding refers to the degree to which ordinary people know about rights, talk about rights, and, at times, make legal claims to their rights.Footnote 8 Beliefs about constitutional law – whether technically accurate or inaccurate – set out the possibility that the constitution and constitutional rights become reference points in social life. As those beliefs are contextualized within people’s everyday experiences, they become less abstract and more locally meaningful. These beliefs then provide the foundation for legal claim-making, influencing which issues people see as a matter of rights, claimable through the courts, or protected by the constitution and which ones they do not. Thus, social embedding can be thought of as a subset of legal consciousness, which refers to the ways people think about and use or do not use law more broadly.

Legal embedding refers to the process by which a particular vision of constitutional law becomes the dominant understanding held by actors in the formal legal sphere. Newly developed constitutions set out rights, rules, and obligations whose enactment requires the construction of an infrastructure made up of physical settings, such as courthouses, and various people, including judges, clerks, bureaucrats, and the like. Without this infrastructure, neither the state nor citizens will be able to make claims or settle disputes under the law. These various actors, in carrying out their jobs, influence how the law comes to life, both opening up new possibilities and closing off others for different groups of people. Ultimately, when legal embedding is robust, the mainstream view among lawyers and judges will be that the new vision of constitutional law is both viable and appropriate, rather than one to be ignored or undermined. Table 1.2 summarizes the observable implications of both social and legal embedding.

Table 1.2 Observable implications of constitutional embedding

Social embedding | Legal embedding |

|---|---|

Everyday people develop a set of beliefs about the constitution | New legal institutions, mechanisms, and actors meant to instantiate a particular vision of constitutional law are created |

People start to talk about specific rights and legal tools that can be used to claim rights in casual, informal, or everyday contexts | Judges and lawyers establish, alter, and expand precedent related to that vision of law |

Folks actually make legal claims to their rights | The mainstream view among active lawyers and judges (including who work at levels below the high courts) is that this vision of law is viable and appropriate |

Successful constitutional embedding – along either or both the social and legal dimensions – is not inherently or necessarily a positive development. It may occur unevenly across rights areas, and it does not mean that the system works for all citizens. Rather, constitutional embedding means that certain rights have been institutionalized and normalized; that they have become accepted parts of everyday life. Individual constitutional rights protections, when realized, may meet the needs of some people, but they may not adequately serve everyone. Some problems might fall outside the realm of constitutional law or be caused by structural factors that are difficult to remedy with individual legal orders. Here, we might think of an inversion of Anatole France‘s comments on the law’s majestic equality: law offers the same promises to everyone, even if needs are not the same.Footnote 9 Further, constitutional embedding may not develop evenly across all constitutionally recognized rights. Some rights may garner more attention in society writ large than others, and some may be viewed as more binding or, on the other hand, as more aspirational by the legal community than others. Even when this variation is present, a constitution may still be deeply embedded in a particular context.

One driver of constitutional embedding is legal mobilization. Legal mobilization involves decisions by both everyday citizens (who choose whether or not to make legal claims on the basis of how they understand the law) and judges (who decide whether and how to respond to those legal claims). The iterative process of claim-making in the formal legal sphere shapes how everyday citizens and legal actors understand what the law is and does, or what the law ought to be and do. By engaging in this kind of claim-making, potential claimants, judges, and intermediaries collectively redefine: (1) the kinds of problems that social actors understand as “legal grievances,” or as claimable in the formal legal sphere; and (2) judicial receptivity to particular kinds of claims, or the extent to which judges view a category of claims as appropriately falling within the realm of law. When legal and societal actors agree that particular issues fall within the domain of the law, feedback loops can form, incentivizing continued claim-making and positive judicial responses to those claims. Over time, these patterns can stabilize, resulting in the embedding of a new vision of constitutional law and the heading off of challenges to that new vision. This is exactly what occurred in Colombia following the drafting of its new, social constitution in 1991. Constitutional embedding in Colombia was catalyzed by claim-making using the tutela procedure, especially for claims to the right to health, that the newly created Constitutional Court affirmed. Over time, constitutional embedding expanded, though not always consistently, across rights arenas.

1.4 The Significance of Social Constitutionalism

The rights implicated in social constitutionalism encompass not only the most immediate provisions necessary to make participation in political and social life theoretically possible (e.g., the right to assemble or the right to vote), but also those provisions necessary to make participation in social and political life actually feasible (e.g., access to healthcare, housing, and education). Social constitutionalism may be thought of as implying formal social citizenship, to use T. H. Marshall’s terms. Marshall (Reference Marshall1950: 11) defines social citizenship as “the whole range [of rights], from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage and to live the life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society.”Footnote 10 Here, social citizenship is described in relation to social and economic rights. This understanding of citizenship does not necessarily entail full equality. It simply poses limits on inequality on paper.Footnote 11 Formal social citizenship suggests only equality of opportunity in social and economic realms, while substantive social citizenship might go a step further, requiring some basic level of social welfare provision, though even substantive social citizenship does not necessarily imply complete equality.

As such, legal claim-making related to social goods moves beyond traditional understandings of citizenship rights defined in narrow legal and political terms. In this book, I argue that how people use the law has changed precisely because how they understand the law and rights has shifted. Legal mobilization for social rights reflects claims to citizenship rights that include social benefits and new forms of social inclusion or incorporation. Deborah Yashar (2005: 6, emphasis in original) notes that citizenship regimes determine “who has political membership, which rights they possess, and how interest intermediation with the state is structured.” She continues, “[a]s citizenship regimes have changed over time, so too have the publicly sanctioned players, rules of the game, and likely (but not preordained) outcomes.” Most of the time, citizenship regimes have been oriented around specific civil and political rights, with only limited recognition of social citizenship rights. The recognition of social (citizenship) rights generates important shifts in the nature of the promises that the state makes to its citizens and in the opportunities available to citizens to contest the conditions of their lives. At least on paper, these commitments to address inequality and specifically the unequal access to social goods dramatically change the nature of state–society relations. Here, poverty and inequality become not simply the byproducts of economic or social relations, but evidence of the failure of the government to live up to its obligations.

Typically, social incorporation or the provision of social welfare in developing societies has occurred through one of three dominant models of state–society relations: patron-clientelism, corporatism, or the market alternative. In a setting defined by patron-clientelism, social goods are not universal rights but discretionary benefits that are selectively allocated by political authorities or brokers to individuals in exchange for political loyalty (Bratton and van de Walle Reference Bratton and van de Walle1997; Auyero Reference Auyero2001; Chandra Reference Chandra2004; Kitschelt and Wilkinson Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Stokes Reference Stokes2013). Corporatism, on the other hand, enables access to social goods through segmented linkages between states or ruling parties and organized sectors of the formal economy, particularly workers with membership in labor unions (Schmitter Reference Schmitter1974; Collier and Collier Reference Collier and Collier1979; Yashar Reference Yashar1999). Finally, the neoliberal or market alternative holds that the marketplace and the private sector facilitate a more just, rational, and efficient provision of social goods than the state. In this system, social goods become available to citizens on the basis of their ability to pay the market rate, with the state providing a minimal safety net for those who are incapable (e.g., due to age or disability) of meeting their needs in the marketplace (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Adésínà Reference Adésínà2009).

The social constitutionalist commitment to promoting access to social goods on the basis of an understanding of inherent human dignity marks a stark difference from these traditional models of social incorporation. Social constitutionalism is grounded in principles of universal rights, in contrast to traditional models that offer social inclusion in a formally selective, discretionary, or politically mediated fashion that excludes large numbers of citizens – in particular, those who lacked the partisan ties, organizational advocates, or market leverage required to access social benefits. Moreover, social constitutionalism assigns the courts a prominent role in processing and adjudicating claims to social goods; claims that traditionally have been channeled through political parties, legislative bodies, and state or municipal social service agencies, or simply depoliticized through their relegation to the private sphere of commodified market exchange.

Comparative social policy scholarship has tended to focus on the differences in and determinants of formal welfare policies or types of welfare states (e.g., Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Powell and Barrientos Reference Powell and Barrientos2004; Lynch Reference Lynch2006; Pribble Reference Pribble2011; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2012). Another strand of scholarship has explicitly examined why developing countries have failed to construct robust social welfare protections comparable to those in western Europe (e.g., Gough et al. Reference Gough, Wood, Barrientos, Bevan, Davis and Room2004; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008; Rudra Reference Rudra2008; Mares and Carnes Reference Mares and Carnes2009; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2012; Garay Reference Garay2016). Further work on developing countries has explored the role of conditional cash transfers as part of social welfare policy (Valencia Lomelí Reference Valencia Lomelí2008; Fiszbein, Rüdiger Schady, and Ferreira Reference Fiszbein, Schady and Ferreira2009; Ferguson Reference Ferguson2015). Scholars have also begun to identify informal dimensions of welfare policy (Holland Reference Holland2017), the role of nonstate actors in the provision of social goods and social programs (e.g., Wood and Gough Reference Wood and Gough2006; Martinez Franzoni 2008; Cammett and MacLean Reference Cammett and MacLean2014), and the importance of shared histories and social identities for social policy development (Singh Reference Singh2017; Wilfahrt Reference Wilfahrt2018).

According to these accounts, with greater or lesser success, citizens pursue such channels as voting, lobbying, and otherwise pressuring elected officials to voice their preferences or make social welfare demands, or they look inward, to self-help or friends and family. In particular, existing studies of the development of social policy regimes emphasize the electoral determinants of social policy change or policy enforcement (e.g., Iversen Reference Iversen2005; Mares and Carnes Reference Mares and Carnes2009; Garay Reference Garay2016; Holland Reference Holland2017), the importance of the preferences of employers (e.g., Swenson Reference Swenson2002; Mares Reference Mares2003), or the strength of the political left (e.g., Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2012). The ability of the poor to influence social policy historically has been limited due to challenges to effective political mobilization, including but not limited to labor informality, diverse and even contradictory interests, and exclusionary or clientelistic political contexts (e.g., Weyland Reference Weyland1996; Cross Reference Cross1998; Roberts Reference Roberts1998, 2002; Kurtz Reference Kurtz2004; Kitschelt and Wilkinson Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008; Abdulai and Hickey Reference Abdulai and Hickey2016).

Considering the barriers facing the poor and marginalized, social constitutionalism and legal mobilization potentially offer citizens who are otherwise cut off from formal channels of political access the chance to express need or discontent; an opportunity that is largely unavailable for individuals in the context of other modes of social incorporation. In this view, the courts may serve the interests of the poor, perhaps more so than any other democratic institution. In the context of social constitutionalism, issues related to the provision of social goods are thrust into the legal sphere. On paper, the guarantees of social constitutionalism are universal in nature, though, like other universalistic guarantees, access to these social goods and services in practice often remains less than desired. In this context, social policy expands and contracts in part on the basis of the ability of individuals or groups to make legal claims and receive a positive response from courts. Here we see a new form of selectivity: one that differs from the selectivity inherent to clientelism, corporatism, or market-based access to social goods. In addition, the social constitutionalist model raises the question of who or what institutions will enforce the social rights claims that judiciaries may assert but cannot on their own deliver.

While social rights may appear in international law as a single, coherent idea, providing the minimum conditions necessary for a dignified life and conferring both positive and negative obligations on the state, the goods that comprise social rights relate to the market in very different ways and are claimable in very different ways. These goods can be constructed as public, private, or a mix of the two, and the extent to which the state engages in the public provision of each good may vary across time and place.Footnote 12 For instance, in the present day, most states provide for some degree of basic education and require school attendance, often through the end of secondary school. On the other hand, states vary substantially in terms of investment in large-scale public infrastructure and investment designed to provide access to other social goods. Healthcare can also be understood primarily as a private good, a market commodity accessible by individuals through private insurance plans, clinics, and hospitals, or as a mix of the two. The same can be said for housing. Generally speaking, the market alternative, clientelism, and corporatist models do not treat healthcare or housing as public goods in that some measure of formal excludability persists, which is not true of social constitutionalism. Social constitutionalism and the ensuing legal mobilization for social rights, thus, fundamentally shift the boundaries of social policy and the nature of social incorporation.

The durability and long-term consequences of this kind of expansion of access to social welfare goods as rights are largely unknown. Constitutional rights offer equal access to all citizens on paper, yet real access is determined by the ability of citizens to make claims to these goods, either as individuals or as part of a group. Thus, legal recognitions offer an indirect route to social incorporation and to social policy change; one that might reify rather than offer redress for preexisting disadvantage. In order to assess these consequences, however, we must first understand how social constitutionalism came about and developed over time – something that the subsequent chapters of this book document for the Colombian case.

1.5 Empirical Approach

In order to explore constitutional embedding, I turn to the case of the 1991 Colombian Constitution. In some ways, Colombia is exceptional. Unlike much of Latin America, Colombia’s constitutional history throughout the nineteenth century was remarkably stable, which means that there were competing, previously institutionalized visions of law in existence as the country sought to draft a new constitution. Further, the 1991 Constitution featured a significant shift in the content of constitutional law – from liberal to social constitutionalism. And perhaps most obviously, the tutela procedure allows nearly unprecedented access to the judiciary for everyday citizens. The tutela procedure considerably reduces the cost, time, and knowledge or experience necessary to make constitutional rights claims. The relative ease of making claims and the scope of claim-making possibilities helped to push the embedding of the 1991 Constitution. The constitution came to be part of daily life, from accessing state information to gaining healthcare services. This outcome, however, was not a foregone conclusion. The tutela procedure was initially limited to civil and political rights claims. Those limits could have persisted. Judges could have stymied claim-making. Claimants could have turned away from the tutela procedure for a variety of reasons. Constitutional embedding could not have happened. The existence of the tutela did not guarantee embedding, and the initial design of the tutela would not suggest embedding as a particularly likely outcome.

In other ways, the case of Colombia is quite ordinary. Following a period of social and political strife, citizens mobilized, calling for significant reforms to the institutions of government and a refounding of the country based on new constitutional principles. These institutional changes took place in an international and regional environment that privileged rule of law and judicial reforms (Hammergren Reference Hammergren2006; Santos Reference Santos, Trubek and Santos2006). Those reforms were enacted and developed in unexpected ways, changing as various actors – from legal and political elites to everyday citizens to insurance companies – came together to negotiate meanings and possibilities of the law. By carefully examining how visions and uses of law changed in Colombia throughout the 1990s and 2000s, we gain insight into how constitutional embedding can occur (and/or be hindered) through the process of legal mobilization, as well as the limitations of constitutional embedding.

To examine how and why constitutional embedding occurs, I spent one year in Colombia between June 2016 and May 2017. During this time, I primarily lived and worked in the cities of Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali. I conducted interviews with both “legal elites” – a term that loosely refers to lawyers, judges, law professors, and activists at nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that include litigation within their strategiesFootnote 13 – and, to a lesser extent, everyday citizens. This amounted to eighty-four interviews with ninety-two legal elites, as well as seventy-four interviews with ninety-three everyday citizens. The elite interviews were primarily conducted in the cities of Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali between June 2016 and May 2017. I also conducted a few interviews remotely after my research trip had ended. Typically, these interviews took place in judges’ chambers, law offices, or on college campuses, though some took place in interviewees’ homes. And typically, these interviews lasted between one and two hours. Several elite interviews involved two interviewees at a time. Often, this occurred because I sought out an interview with a particular individual who then invited a colleague to join our conversation.Footnote 14

One set of nonelite interviews was conducted in Bogotá in February and March 2017. With the help of a Colombian research firm, the Centro Nacional de Consultoría, respondents were randomly selected within three class categories or estratos (lower, middle, and upper). Interviews were conducted in locations chosen by the respondent, usually the respondent’s home. Over the course of an hour-long semi-structured interview, respondents were asked to share their views on their neighbors and neighborhoods, on any difficulties they or their family members had in terms of topics ranging from healthcare, housing, education, social security, or pensions to minor disputes between neighbors, and, at the end of the interview, on the Colombian legal system.

I conducted the second set of nonelite interviews – twenty-four unstructured individual and group interviews with forty-three people – in Agua Blanca, Cali during April and May of 2017. These interviews took place in respondents’ homes and more often than not took the form of informal conversations about justice in Agua Blanca or in Colombia. A local interlocutor connected me with each interviewee and was present for the majority of these interviews. As a result, these interviewees were primarily part of her social network and are not necessarily representative of the district as a whole. These interviews varied significantly in time, ranging from ten to fifteen minutes to well over an hour. After transcription, each set of interviews was organized, coded, and analyzed.

These interviews allowed for the probing of the orientation of the judicial establishment, as it appears on the inside (to judges and lawyers) and the outside, as well as to those who have tried to traverse those boundaries (including claimants, activists, and academics). They also allowed me to assess beliefs about the appropriate role of legal institutions in democratic society and the status of social rights (specifically to what extent they are justiciable or claimable).

I also fielded a survey, with the help of several law students from the Universidad de Antioquia, in March 2017 of 310 tutela claimants.Footnote 15 The survey was based on a convenience sample of people waiting in line outside the Palacio de Justicia in Medellín to file a tutela claim in April 2017. As such, they reflect the views of individuals who have already decided to file a legal claim rather than the views of the general population. This survey only includes claimants – individuals who had already recognized something in their lives as problematic and who had decided to turn to the legal system to address that problem – and, as such, the respondents are not necessarily representative of the broader population.

Beyond these interviews and surveys, I analyzed both archival and legal documents. In order to assess the debates that took place at the Asamblea Nacional Constituyente (the constitution-drafting body), I turned to a collection held at the Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. I collected data on two types of legal cases: tutela cases (T-cases) and abstract review cases (C-cases).Footnote 16 Every Constitutional Court decision is available online, which allowed for the scraping of a random sample of tutela cases from the Constitutional Court’s website and to organize that sample into a dataset.Footnote 17 I obtained information about abstract review cases from the Congreso Visible project at the Universidad de los Andes. I also consulted numerous reports issued by the ombudsman’s office and the judiciary.

In addition, I participated in the two-week “Caravan for Peace, Life and Justice,” organized by Colombian social leaders in November 2016, which involved visits to a variety of small and large Colombian cities, as well as rural areas that were hard-hit by the decades-long armed conflict between the Colombian government, the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), other guerilla groups, and various paramilitary groups. Finally, I spent significant periods of time in law offices and courtrooms, community group and social movement meetings, and government agencies observing and, less frequently, participating in the events occurring around me. This participant observation, while difficult to meaningfully quantify, proved to be invaluable in helping me to better understand both the patterns I observed in legal claim-making practices as well as what I learned through the semi-structured interviews and survey responses. Many of these experiences do not explicitly appear again in the pages that follow, but they provided vital insight into the ways in which the broad shifts in the meaning of law that form the core focus of this project are manifest in and by lived experience.

1.6 Outline of the Book

This book examines the construction and reconstruction of notions of obligation, specifically with respect to the conditions under which the state has an obligation to protect the social needs of its citizens in Colombia. Focusing on one particular site of contention over these notions of obligation – the formal legal sphere – I investigate the dynamics of legal mobilization for social claims as they relate to the activation and embedding of social constitutionalism. In the process, I address issues related to the functioning of democratic institutions and the actors that operate within them, state–society relations, social welfare provision, and institutional change. The rest of this book proceeds as follows.

Chapter 2 introduces the idea of “constitutional embedding” and describes how legal mobilization can put into motion processes that result in the embedding of social constitutionalism. Constitutional embedding occurs along two dimensions: social and legal. Where social and legal embedding reinforce one another, constitutional embedding will be particularly robust. Where they do not, constitutional embedding will be vulnerable to challenges related to the scope of the law, concerns of powerful actors, and the workload judges must navigate. Each type of challenge can derail both social and legal embeddedness, and, as a result, limit the potential for social constitutionalism to translate into gains in real access to social welfare goods. Legal mobilization can catalyze constitutional embedding, as it facilitates the social construction of legal grievances and the development of judicial receptivity to particular kind of claims, in the process shaping views about the law.

Chapter 3 provides the backdrop of constitutionalism in Colombia, demonstrating that although many sectors of society sought dramatic legal change with the 1991 Constitution, few imagined the breadth of the social changes that would come with that legal text. It tracks how substantive social constitutionalism and the creation of new access mechanisms, most importantly the tutela procedure, emerged. It closes with an introduction to early legal claim-making under the 1991 Constitution.

Chapters 4 and 5 detail the ways in which social constitutionalism became socially and legally embedded, respectively. Chapter 4 tracks how the tutela procedure came to attain a central place in Colombian life, as people were inundated with opportunities to learn about the new constitution, including through media campaigns, popular television shows, board games, and comics. Over time, the tutela became “vernacularized,” and Colombians not only talked about the tutela procedure but transformed the word tutela in several different verb forms. Colombians developed a set of beliefs about the possibilities created by the new constitution, and these beliefs – whether accurate or inaccurate in relation to the constitutional text – drove claim-making using the tutela procedure, which in turn ensured the social embedding of the constitution.

Chapter 5 explores legal embedding in Colombia. It tracks why and how Colombian judges – both at the Constitutional Court level and the lower-court level – came to be receptive to the new constitutional order, especially claims through the tutela procedure, even when those claims appeared to be beyond its formal scope. The combination of repeated exposure to particular kinds of legal claims in the formal legal sphere and exposure to the problems those claims implicate in everyday life seems to drive judicial receptivity. Judges are particularly receptive to claims when they interpret them as consonant with contemporary sociolegal values.

Chapters 6–8 cover the three challenges to the stability of Colombia’s social constitutionalist order: scope, power, and work. Chapter 6 examines the limits of legal legibility, or what – and whose – problems are legible to the law, and who gets left behind. The chapter looks to the community called Agua Blanca in the western part of Colombia. There, the most visible impact of the 1991 Constitution seems to be the conversion of rights promises into paperwork. While residents of Agua Blanca still use the tutela procedure, accepting the idea that filing tutela claims is what one has to do to try to gain access to services, they see the 1991 Constitution as largely irrelevant to their lives, which are instead constrained by violence and marginality.

Chapter 7 focuses on overt, political efforts to confront social constitutionalism and unravel rights protections. Following the introduction of the 1991 Constitution, established elites within the judiciary, the executive, and the legislature bristled at the changing political and legal landscape. They attempted to stymie those changes in various ways, primarily seeking to disempower the newly created Constitutional Court and limit the newly created tutela procedure. The popularity of the Constitutional Court and the tutela procedure – and continued legal mobilization using the tutela procedure – however, meant that these efforts to dislodge social constitutionalism in Colombia failed.

Chapter 8 turns to the labor of law, or the difficulty of keeping up with the daily work that underpins this legal order. While Constitutional Court judges have garnered substantial attention, lower-court judges are tasked with the majority of the work of social constitutionalism in Colombia. They are the ones who have reviewed each of the nearly eight million tutela claims that have been filed since 1992. Many of these lower-court judges report that they feel overworked and underresourced. Material and normative pressures, thus far, have combined to ensure that these judges continue to keep up with the labor of social constitutionalism.

Chapter 9 extends the argument of this book to the case of the 1996 South African Constitution, demonstrating the usefulness of examining the contours and limits of constitutional embeddedness beyond the Colombian context. The South African case is one of partial constitutional embedding, where legal embedding significantly outpaced social embedding. While judges, lawyers, legal aid organizations, and NGOs embraced the language and tools of the new constitution, many social groups adopted rights discourse hesitantly, if at all, and still others explicitly rejected rights (Smith Reference Smith2015). This comparative examination probes different ways in which constitutional embedding can occur in practice, and it helps to show how constitutional embedding is not a necessary or inevitable phenomenon.

Chapter 10 draws out the implications of this study of constitutional embedding for how citizens access social goods around the world and how scholars ought to study constitutional law and legal mobilization. Though not without important limits, the introduction of social constitutionalism to Colombia has resulted in tangible material gains for many citizens and generated new possibilities for citizens to contest the conditions of their lives.