17.1 Introduction

An important aspect of reexamining carceral logics is the careful consideration of approaches for reforming the law and social practices surrounding confinement more generally. Toward that end, this chapter undertakes a comparative examination of cause lawyeringFootnote 1 in the prisoners’ rights and animal protection movements. Drawing on the rich literature on cause lawyering and social movements, and on our backgrounds in American constitutional law, we discuss the similarities and differences in the possibilities for legal advocacy concerning the rights of incarcerated persons and the treatment of nonhuman animals. In the limited space available for our discussion, we aim primarily to offer a descriptive comparison rather than a normative prescription. We hope that, to the extent possible, viewing these movements through a comparative lens might lead to a collaboration and dialogue among public interest lawyers working in these respective spaces to share ideas about strategic approaches and potential similarities that might be employed to overcome common barriers to progress.Footnote 2 Furthermore, by pursuing such a typological approach, we suggest that these same points of comparison might be useful in assessing similar connections between or among other social movements.

We begin the chapter with a brief discussion of the missions of each movement and observe that within each there are both long-term structural goals and narrower, concrete objectives. Though we could discuss a wide range of factors in comparing the movements, we narrow our focus to just three. First, we examine the important role that attorneys who work in these movements play in overcoming the invisibility of the populations they represent. Second, we explore ways in which lawyers advocating for these groups can facilitate moral suasion that could have a potentially more extensive real-world impact than might formal legal reforms. Third and lastly, we discuss the role of cause lawyering in addressing disenfranchisement of the relevant communities. Of course, these three categories are overlapping and coconstitutive, and by organizing the discussion in this way, we do not mean to suggest otherwise. For example, addressing the disenfranchisement problem may lead to more vocal advocacy and less invisibility. Similarly, great visibility can result in more public engagement in relevant moral debates. For the purposes of our discussion, however, we deem it valuable to address them as distinct points of comparison.

17.2 Movement Goals and Objectives and the General Role of Cause Lawyers

An important element in measuring the success of any social movement is identifying its precise goals. We acknowledge, of course, that movements are not monolithic and are constantly in flux, and that divisions, even sharp ones, commonly arise within any movement about its goals. For our purposes, we identify what might be considered the aspirational or long-term goals of each movement and then home in on each movement’s more discrete objectives (though by discrete, we mean separable from the aspirational goals; many of the discrete objectives are themselves quite substantial). But we also note that within each movement, given limited resources, there may well be a divide between those who wish to seek broader, structural reforms and those who prioritize improving the conditions and quality of life for each individual involved.Footnote 3 Moreover, as in other social movements, there will be disputes about incrementalism versus more immediate, radical transformation of the law. These goals can be debated at the margins, but we view them as creating a helpful organizing frame for the discussion.

A starting point is considering how to characterize each movement and identifying what might be described as aspirational or ultimate goals for each of them. As in other realms of public interest law, it is tempting to center discussions about a movement around major victories in the judicial or legislative arenas. Indeed, in the early years of the prisoners’ rights movement, the nation witnessed pathbreaking Supreme Court decisions solidifying previously unrecognized rights for incarcerated persons, including basic due process rights in disciplinary proceedings,Footnote 4 the right that prison living conditions not be so severe as to violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishment,”Footnote 5 and prisoners’ entitlement to “the minimal civilized measure of life’s necessities,” including food, clothing, and medical care,Footnote 6 to name a few. A number of later decisions, however, would make it much more difficult for incarcerated persons to successfully press these claims. For example, in Wilson v. Seiter, the Court erected a deliberate indifference standard, substantially reducing the likelihood of a prisoner’s success on a claim challenging “inhumane conditions of confinement.”Footnote 7 And in Sandin v. Conner, the Court cut back on procedural due process protections for prison disciplinary proceedings, finding that they apply only when the resulting sanction imposes an “atypical and significant hardship on the inmate in relation to the ordinary incidents of prison life.”Footnote 8

Focusing on bold judicial proclamations risks essentializing a social movement around law only, which might result in the neglect or marginalization of other critical political and social factors. Scholars whose work focuses on the prisoners’ rights movement thus approach the definitional question in a more nuanced manner. Marie Gottschalk defined the prisoners’ rights movement as “the broader effort by a variety of groups and organizations from roughly the 1950s to the early 1980s to redefine the moral, political, economic, and legal status of defendants and offenders in democratic societies through a range of activities, including lawsuits, legislation, demonstrations, strikes, riots, and calls for revolution.”Footnote 9 Similarly, an older characterization of the prisoners’ rights movement that still resonates today sees it as “a broadscale effort to redefine the status (moral, political, economic, as well as legal) of prisoners in a democratic society.”Footnote 10

But toward what end? In the context of prison reform, the ultimate aspirational goal for many may be prison abolition, though that phrase itself is fraught with contested and diverse meanings.Footnote 11 To some, abolition is an umbrella term for broad, structural reform that includes not only eradication of mass incarceration, but also the transition toward alternatives that address more embedded social problems, including poverty, drug dependency, and racism, that lead to crime. Such reform is also integrally related to reexamining other crucial aspects of the criminal justice system, most notably policing. Importantly, abolition is a perspective that has thus far gained more traction in academic circles than it has on the ground in social-movement lawyering.Footnote 12 For example, the ACLU’s National Prison Project describes its work in this, more limited, way: “Through litigation, advocacy, and public education, we work to ensure that conditions of confinement are consistent with health, safety, and human dignity, and that prisoners retain all rights of free persons that are not inconsistent with incarceration,”Footnote 13 which implicitly does not embrace abolition insofar as it assumes at least some imprisonment will be ongoing in our society. That does not diminish the centrality of prison abolition, however, because intellectual and political movements that broadly reframe social goals, even in radical (and perhaps impractical) ways, can strongly influence how public interest lawyers view their tactical approaches.

In terms of relatively more discrete reform efforts, those in the prisoners’ rights movement have worked tirelessly to end capital punishment; to abolish or severely limit solitary confinement; to promote basic rights of dignity, safety, and security for prisoners; to seek material improvement of conditions for those who remain incarcerated, by, for example, eliminating overcrowding and improving medical and mental health care; ending forced labor of convicted persons; promoting the free exercise of religion, especially among incarcerated persons who are Muslim; ensuring rights of access to reading materials, law libraries, and the courts; and, as has been much in the news of late, restoring voting rights to persons who have completed their terms of incarceration. Of course, cases can raise important constitutional issues on behalf of individual prisoners as well.

Like prison abolition, the big-picture concept of animal protection embraces a variety of positions that are not always in harmony.Footnote 14 The emergence of an animal protection movement is a story built around two separate campaigns, one to change law and society to promote substantial improvements in animal welfare and another, bolder one that seeks to expand the legal recognition of rights for animals and to end all human exploitation of animals.Footnote 15 At first glance, these goals do not appear to be mutually exclusive, but they do reflect serious divisions over the ultimate end goals of the movement. Animal welfare advocates seek greater protection for animals from inhumane or cruel treatment, enforcement of laws against animal cruelty, and limits on, or the end of, the exploitation of animals across all contexts, but do not assert that the law should recognize nonhuman animals as having independent rights. It could be argued that animal welfare proponents are concerned less with global or structural change, and instead care more about incremental reform and stronger enforcement of existing laws protecting animals. Animal rights proponents, by contrast, pursue the more ambitious, aspirational objective of legal recognition of rights for nonhuman animals, equivalent or functionally comparable to those of humans, though there are disagreements within the movement about the scope of that recognition. As with prison abolition, the more expansive vision of animal rights has led to a greater degree of philosophical and academic discourse than it has lawyering on the ground, at least to date.Footnote 16

In the near term, the goals of animal welfare and animal rights advocates often converge. Well shy of, along an aspirational spectrum, something approximating a rights-based approach to animal welfare, one can observe common goals in enhancing legal protection and enforcement of laws against animal cruelty, defined broadly to include the exploitation and mistreatment of animals in the industrial agriculture and entertainment industries. Animal welfare proponents seek the enforcement and enactment of stronger legal protection for animals from cruel treatment, tougher regulation of businesses that use animals for commercial gain, such as the agriculture, entertainment, cosmetics, and fashion industries, and action to address cruelty in the commercial breeding of pets.Footnote 17 But even groups more closely associated with rights-recognition describe their objectives in ways that do not differ significantly from those of animal welfare groups. For example, while People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) proclaims that “[a]nimals are not ours to experiment on, eat, wear, use for entertainment, or abuse in any other way,”Footnote 18 which connotes a rights orientation, it focuses much of its work on discrete projects designed to reduce or minimize animal suffering. Similarly, the Animal Legal Defense Fund states that its mission is to “protect the lives and advance the interests of animals through the legal system.”Footnote 19 Yet ALDF seeks to accomplish this mission principally “by filing high-impact lawsuits to protect animals from harm, providing free legal assistance and training to prosecutors to assure that animal abusers are held accountable for their crimes, supporting tough animal protection legislation and fighting legislation harmful to animals, and providing resources and opportunities to law students and professionals to advance the emerging field of animal law.”Footnote 20

One thing that distinguishes the two strands of animal advocacy is that animal-rights groups also engage in strategies that will directly or indirectly lead to the recognition of greater rights for animals. For example, those who focus on animal rights have promoted efforts to establish legal standing for animals to pursue their rights in the courts. In some cases, animal rights organizations have sought to stand in as the legal representative of specific animals as a “next friend” or legal surrogate pursuant to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,Footnote 21 even though several courts have rejected those arguments because the rules refer to representing an incompetent “person.”Footnote 22 Interestingly and perhaps importantly, a couple of decisions from the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit have stated that animals can have standing, even without a next friend, under Article III of the US Constitution.Footnote 23 In both of those cases, however, the court went on to hold that the animals could not establish standing under the relevant federal statutes they invoked as the substantive bases for their lawsuits. Surely, the right of an animal to sue in federal court could be acknowledged as one step toward legal rights recognition.

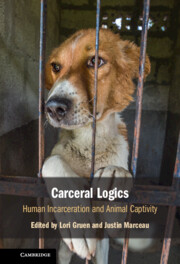

Another noteworthy observation about divisions within each movement is how much they parallel each other. In a sense, in both the prisoners’ rights and animal protection movements, one might see the differences in vision as “no cages” versus “bigger and better cages.” Prison abolitionists and animal rights advocates argue for the end to incarceration and all human exploitation of animals, respectively. Prison conditions advocates and animal welfare proponents argue for reforms that improve the lives of the caged, but do not liberate them. These parallels are not only interesting, but also may inform how reform advocates set their priorities. To some extent, some abolitionists may look at the “bigger and better cages” group as a counterproductive force, believing that small-bore reforms in some way perpetuate the status quo or create the illusion that such reforms have addressed the main problems, thus perhaps reducing the urgency of more ambitious abolitionist goals.Footnote 24 In contrast, the bigger-and-better-cages proponents may charge the abolitionists as unrealistic idealists whose work might ignore the value of incremental progress.Footnote 25 This may create fissures within the movements that may be inescapable. An introspective understanding of these dynamics may be valuable in assessing the movements’ strategic futures.

Before moving on to the rest of the discussion, we make two observations that are widely recognized in the cause-lawyering literature. First, we acknowledge that litigation, which we identify and analyze as one strategic option for lawyers in these two movements, has been the subject of widespread criticism as a social movement tool. In short, such critics

suggest that rights litigation is a waste of time, both because it is not actually successful in achieving social change and because it detracts attention and resources from more meaningful and sustainable forms of work such as mobilization, political lobbying, and community organizing. In this sense, the critics claim that rights lawyers offer nothing but “hollow hope” and create false expectations of sustainable social transformation.Footnote 26

For purposes of our discussion, we assume these critiques to have some validity, even as we seek to identify a broader understanding about the contributions attorneys can make to advance social movements.

Second, we recognize the concern that cause lawyers in these fields might not be fully sensitive to the power imbalance between clients or constituents, on the one hand, and their attorneys, on the other.

Although clients have the ultimate authority to define the goals of representation, as many commentators have noted, the line between ‘ends’ and ‘means’ is not so neat, and lawyers may (even sometimes unknowingly) use their position of relative power to advance agendas that may diverge from the clients’, thus undercutting client autonomy. . . . [T]he problem arises [especially] when the client is relatively weak, which permits the lawyer to make crucial case decisions, often persuading the client to go along.Footnote 27

While these challenges are ever-present in most areas of public interest law, they may be particularly acute in the context of prisoners and animals, making both groups subject to replication of the disempowerment that exists because of the laws, structures, and carceral logics that shape their treatment. Public interest lawyers addressing the three areas discussed below must be sensitive to these power dynamics in working on behalf of their clients and the causes they represent.

17.3 Countering Invisibility

In any given generation, there are multiple worthy social causes vying for public attention. Advocates for such causes compete for scarce resources, including charitable donations, legal and policy advocates, and level of public concern. For some causes, even ones that present existential threats such as climate change, constituents are diffused and unorganized, which makes for difficulties in gaining attention and also creates collective action problems. For example, in the 1960s and 1970s this was the case for environmental and consumer protection interests.Footnote 28

In other contexts, the challenges to commanding public attention might be driven primarily by the fact that constituencies are not as readily visible; for many groups, it is “out of sight, out of mind.” There are numerous reasons why a particular group may be invisible to the broad spectrum of the public eye. First, all invisibility problems may be partly a function of lack of power. This factor is one that likely affects most communities seeking greater legal protection in our society. Second, invisibility may be the product of a subjective sense of public discomfort predicated on biases and stereotypes. Thus, the general public may look at members of powerless groups, such as persons experiencing homelessness, people with disabilities, and transgendered persons, without really seeing them in a way that acknowledges their humanity and dignity. These causes of invisibility likely affect both incarcerated persons and many animals. But a third cause of group invisibility is as elementary as actual physical segregation. Prisoners and many categories of animals, including farmed animals and animals used for experimentation and testing, are literally behind walls.Footnote 29 As Justice Kennedy once observed in a speech to the American Bar Association, “When the door is locked against the prisoner, we do not think about what is behind it.”Footnote 30 However, he went on, “As a profession, and as a people, we should know what happens after the prisoner is taken away.” Indeed, this is one of the central challenges in dismantling carceral logics. Here invisibility is not just a metaphor, but a product of social and physical isolation through incarceration.

To invoke a comparison from constitutional doctrine, there is a strong relationship between invisibility and insularity. In the widely referenced footnote 4 in United States v. Carolene Products Company,Footnote 31 the Supreme Court observed that heightened judicial scrutiny might be necessary to protect “discrete and insular minorities” from the majority-driven political process. The concept of insularity connotes a separateness from the general public that results in unfamiliarity with such groups, causing voters and lawmakers to be, at best, insensitive to, and at worst, actively prejudiced toward, members of such groups.Footnote 32 And insularity surely begets invisibility.

A challenge, then, for social movement lawyers in these fields is to make their clients and their clients’ experiences visible to the world. Enhanced transparency can lead to public recognition of the plights of prisoners and animals; public recognition, in turn, can lead to increased understanding, attitudinal shifts, and ultimately law reform. Being visible means garnering public attention, sympathy, and support.

Sometimes visibility arises spontaneously on account of discrete, high-profile events or series of events. In the summer of 2020, for instance, the nation watched in shock as cell phone videos of horrifying police violence toward and killing of Black men and women went viral, calling focused public attention to the Black Lives Matter movement. These victims included Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks, and Jacob Blake. And those were just the violent incidents that became public. At the Democratic National Convention, George Floyd’s brother called on Americans not only to mourn those whose names were already widely known, but also those who were unknown “‘because their murders didn’t go viral.’”Footnote 33 But this attention can be fleeting. Despite what seems like an endless string of tragic school shootings, the public’s interest in comprehensive gun regulation seems to quickly wane over time.Footnote 34 And 2020 is hardly the first time the country’s focus has been drawn to what seem like obvious incidents of unjustified police shootings of young Black men. The attention generated by the numerous other police killings of Black people a few years ago and the ensuing protests were, sadly, short-lived.Footnote 35

But more often than not, making clients and their causes visible requires a conscious, affirmative, and sustained effort. Cause lawyers may promote their clients’ visibility through a combination of advocacy tactics such as public education and media campaigns.Footnote 36 Sometimes litigation can serve not only the primary objective of vindicating and enforcing legal rights, but also as a mechanism to educate the broader public about the underlying conditions that caused a particular conflict. Indeed, even when the litigation is unsuccessful, it can promote learning and call attention to an otherwise overlooked social problem.Footnote 37

In the early stages of the prisoners’ rights movement, litigation was often used as a tool not only to reveal problems with the treatment of prisoners to the courts, but also to establish sustained oversight of prison systems by federal judges.Footnote 38 This had an important transparency dimension because it contemplated an ongoing role for the judges to be informed about prisons’ compliance with injunctive orders or consent decrees. Not surprisingly, over time these orders were met with increasing resistance by state officials and judicial conservatives, who argued that this exceeded the proper role of the federal judiciary, which was accused of micromanaging day-to-day prison operations.Footnote 39 Eventually, those criticisms took hold, and the courts mostly abandoned such efforts to oversee prisons. Moreover, federal legislation such as the Prison Litigation Reform Act made it much harder for prisoners to file civil rights claims by limiting the types of damages that could be recovered and capping attorneys’ fees.Footnote 40

Other transparency mechanisms are limited as well. As one commentator has noted:

Currently, prisons and jails are shrouded in secrecy. Media access to prisoners and prisons is extremely limited and completely discretionary. Moreover, investigative reporting is generally in decline given the changing nature of media, news, and reporting. In combination with the high barriers to obtaining prison related information, media coverage is less able to fill the prison transparency gap.Footnote 41

Indeed, the Supreme Court has directly rejected the idea that the media should have a special First Amendment right to gain access to prisons in the interest of transparency.Footnote 42 But perhaps prisoners’ rights advocates might pursue federal legislation that requires or incentivizes correctional institutions to report data in important categories, such as statistics on medical care, violence in prisons, and the administration of prison disciplinary policies as one mechanism to increase transparency.Footnote 43

Addressing invisibility has similarly been an emphasis of some aspects of the animal protection movement. As McCann and Silverstein observed, there are constraints on traditional litigation tools in the animal rights context that do not limit other movements.Footnote 44 This helps explain why cause lawyers in the movement often focus on more conventional rights claims that will indirectly yet still importantly promote the interests of animals. “For animal rights advocacy, this mean[s] creatively using resources like free speech laws and open meetings laws to heighten awareness about hunting, dissection, and animal experimentation.”Footnote 45

Another example of this is in sustained efforts to promote transparency about animals farmed for food production. These animals are exempt from the Animal Welfare Act’s protections,Footnote 46 and the conditions in which they live and are killed are decidedly nonpublic. To address this lack of transparency, undercover investigators in several states have gained access to slaughterhouses and other animal facilities and made secret video recordings of severe mistreatment of farmed animals that were then made widely available over the internet.Footnote 47 Dismayed at the negative publicity, the industry lobbied state legislatures to bar such investigations, which many states have done by making it a crime to misrepresent one’s identity to gain access to an animal agriculture facility or to take photographs or make a video recording without the owner’s consent.Footnote 48 These so-called “Ag-Gag” laws were soon enacted in a number of states where animal agriculture is a prominent part of the local economy. ALDF, PETA, and other animal rights groups have mounted a nationwide litigation campaign to challenge these laws as violating their First Amendment free speech rights. While the campaign is ongoing, many of these suits have been successful, with federal courts in several jurisdictions declaring the laws to be invalid.Footnote 49 The central point of Ag-Gag challenges it that transparency is an essential component of animal law reform. If a larger percentage of the public was aware of how the mass production of animals for food creates an environment of cruelty and raises substantial concerns about food safety, efforts to seek legislative reforms would be much more likely to gain traction. Moreover, the information disclosed through these investigations may sway public opinion in ways that will enhance the possibility of greater recognition of animals’ rights.

Notably, some progress on the public-opinion front has already been made in recent years. A 2015 Gallup Poll found increasing support for animal rights in the United states, with 32 percent of respondents believing that animals should have the same rights to be free from harm and exploitation as humans, and 62 percent believing that animals deserve “some” protection from such harm but that animals may still be used for the benefit of humans.Footnote 50 These figures both represented a notable increase in affirmative responses to the same questions asked in 2008 and 2003.Footnote 51

Conversations across the prisoners’ rights and animal protection movements might promote the sharing of meaningful and thoughtful suggestions for law reform and tactical approaches to overcoming the invisibility of their constituencies. Moreover, recognition of the parallels between the two movements could lead to conscious strategic collaborations through reform efforts – for example, a joint campaign to promote greater transparency for all those who are caged. This could also lead to public education efforts that might lead to a broader understanding of the harms that can result when misconduct occurs but is obscured from the public eye. Similarly, lawyers from one movement might submit amicus briefs in support of court cases brought by advocates in the other movement, calling judicial attention to the parallels between concerns about prisoner and animal welfare. These types of partnerships might also reduce the incidence of the potentially problematic public rhetoric used by movement leaders that we discuss below.

17.4 Facilitating Moral Suasion

Historically, moral suasion has been one of many tactical approaches social movements have employed to achieve their objectives, although the degree of its effectiveness has been debated. A major segment of the slavery abolition movement rested on moral suasion, whether on the legislative or judicial battlefronts.Footnote 52 Moral leadership, from Gandhi to the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., has often been coupled with social movements. Moral commitment to causes can also be one of the driving forces of public interest lawyers working within these movements.Footnote 53 What is distinct about moral suasion as a social reform tactic is that there is nothing uniquely connecting lawyering to moral claims. Indeed, the standard conception of the role of the lawyer suggests that an attorney’s moral views are not to be confused with those of her clients.Footnote 54 As with other social movements, both the prisoners’ rights and animal protection movements engage in moral suasion to help transform public opinion, and ultimately influence public policy, another feature that connects these movements.

Although moral argumentation is not a skill unique to lawyering, it frequently occurs in the context of advocacy in the courtroom and before legislative bodies, two arenas where more traditional legal arguments are commonly employed and where lawyers tend to be heavily utilized. Litigation is not merely a tactic to win rights in specific disputes, but can also be integrated into a broader strategic approach that is designed to facilitate public education, which correlates strongly with movement building.Footnote 55

Within the context of the prisoners’ rights movement, moral claims have probably been most commonly employed in arguments against capital punishment.Footnote 56 Moreover, the contemporary debates over mass incarceration are frequently based on moral claims.Footnote 57 But more broadly, beyond dealing with these more discrete issues, prisoners’ rights advocates can seek to employ moral rhetoric more generally to reexamine basic theories of punishment and the carceral state. This is all the more important because of the connection between social attitudes toward prisoners and incarceration rates. Studies of the effects of the expanding movement against mass incarceration have captured some elements of public sympathy in moving public opinion. One study shows a direct correlation between public views on punitiveness toward convicted persons and incarceration rates.Footnote 58 But public opinion seems to be shifting to a more sympathetic view of prisoners and in favor of major criminal justice reform efforts. And though these results cannot be directly linked to moral arguments, a 2017 poll by the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice found that 91 percent of Americans support criminal justice reform.Footnote 59

However, there may be important limits on the ability of advocates to influence attitudes about prisoners through moral arguments because views about mass incarceration may differ significantly with regard to prisoners who have been convicted only of minor drug crimes than concerning persons who have committed violent offenses. The reform efforts that have been successful thus far have focused on nonviolent offenders.Footnote 60 Meaningful efforts to end mass incarceration must reach beyond those offenders, however, as 80 percent of incarcerated persons are imprisoned on non-drug-related offenses.Footnote 61 In some sense, then, moral arguments could end up being counterproductive if people feel righteous only about deincarcerating a small segment of the prison population.

Although these may be framed publicly as moral debates, they can also be mapped onto legal ones. Indeed, the Eighth Amendment’s very text invites moral debate through its focus on what counts as unconstitutionally “cruel and unusual.”Footnote 62 Moral values even make it into the Supreme Court’s opinions from time to time. In Roper v. Simmons, for example, in the course of declaring that the application of the death penalty to persons who were minors at the time of their crimes is unconstitutional, the Court observed that “[f]rom a moral standpoint it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult, for a greater possibility exists that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.”Footnote 63

Moral claims for animal rights might meet somewhat less resistance, perhaps because at least some animals may be inherently more sympathetic to a broader spectrum of the public than are people convicted of capital crimes. In evaluating moral claims here, we must tread carefully, however, as many in the animal protection movement have pointed out that while people may be sympathetic toward their own pets, they are simultaneously not as likely to feel the same way about farmed animals, animals used for products other than food, and animals exploited for human entertainment.Footnote 64 Indeed, studies have demonstrated that people engage in motivated cognition that causes them to block out relevant information, such as a farmed animal’s intelligence, to avoid the moral dilemma that they would face with such a recognition.Footnote 65 Just as moral claims in the prison reform context may reach a limit that confines the scope of meaningful reforms, these distinctions between domesticated pets and farmed animals may act as a ceiling on more ambitious animal rights claims. Thus, moral claims for animals based in public sentiment may meet more resistance than one might first imagine. If this is the case, then movement leaders must reflect on how to use moral suasion in the face of this type of barrier. Further, the parallels with the limits of moral claims in the mass incarceration context might be worth discussing strategically across movements.

The founding of the animal rights movement has been strongly linked to the writings of moral philosophers such as Tom ReganFootnote 66 and Peter Singer.Footnote 67 In the advocacy movement, moral arguments are presented on a range of issues to oppose keeping animals in captivity for human entertainment, wearing fur, eating meat, using animal products, and medical experimentation on animals, to name just a few.Footnote 68 Moreover, animal rights lawyers use moral claims as a building block for legal rights. As Helena Silverstein has noted:

Animal advocates have increasingly defined their cause in terms of rights. In doing so, movement activists have relied partly on philosophical grounding in rights theory to appropriate rights language and to attribute meaning to rights. This philosophical foundation attempts to extend the meaning of rights, calling for the application of moral rights to animals. It further translates this demand for moral rights into a demand that legal rights be extended to animals.Footnote 69

However, although public sympathy toward animals is strong, the same cannot be said for their human advocates.Footnote 70 Opponents of animal rights activists have attempted to derail the movement by branding all who advocate of animal rights as “terrorists.”Footnote 71

Ironically, however, the prisoners’ rights and animal protection movements sometimes unwittingly engage in moral arguments that are at cross-purposes to the other. One of the largest and most prominent animal rights organizations, the Animal Legal Defense Fund, is frequently associated with the slogan “All Our Clients Are Innocent.”Footnote 72 This offers tremendous appeal from a moral standpoint because nonhuman animals lack agency, so all human exploitation of animals is thrust upon them. Another public relations campaign involves raising the consciousness of pet owners to recognize the moral equivalency of mistreatment of pets with the abominable treatment of animals who are hunted, used for human entertainment, and mass-produced for food and products through our commercial agricultural industry.Footnote 73 As morally persuasive as these approaches to public education can be, they may inadvertently promote a form of “othering,” in that the converse of the ALDF slogan is that perhaps we needn’t care as much about humans who are not “innocent” (using that in the legal as well as colloquial sense).

And at the same time, the morality switch can be flipped in the prisoners’ rights movement, which frequently employs moral rhetoric to raise issues with prison conditions by complaining that the basic rights of incarcerated persons are illustrated by the fact that they are frequently treated “like animals.”Footnote 74 Indeed, sometimes prisoners point out that they are being treated worse than animals. In one reported instance, a man incarcerated at a California prison complained about conditions in overcrowded cells with temperatures of 114 degrees and little ventilation, while pointing out that the prison’s dog kennels were air conditioned.Footnote 75 In another complaint from a Texas prison that reportedly registered 130-degree temperatures and where fourteen prisoners had died from the heat in recent years, it was noted that the prison has recently constructed a $750,000 climate-controlled, swine-production facility on site to produce food for the prisoners.

What is problematic with these characterizations is that, like the claim that all animals are innocent, it pits groups that are oppressed by carceral logics against each other, creating a hierarchy of moral worthiness. Saying prisoners shouldn’t be treated like animals sends an implicit message to the public that not only should humans not be treated like animals, but also that animals are lesser beings and that it may even be acceptable to treat animals “like animals.” And saying that all animals are innocent implies that people who are not innocent may deserve punishment or incarceration. This conflicting moral discourse could ultimately lead to undermining both claims, thereby diluting, if not erasing, the moral message. Indeed, it is potentially troubling messages like that this that can perpetuate the carceral logics that plague our society and undermine important social movements. Thus, conversing across movements and engaging in introspection about moral claims can be a productive way of getting us outside of these types of rhetorical traps.

We note one other area in which there are tensions between these two movements relating to moral suasion claims. Some animal protection groups have included as part of their mission the stricter enforcement of criminal sanctions against persons who engage in unlawful acts of animal cruelty.Footnote 76 That is, such advocates have pursued a carceral strategy against humans to advance the welfare, safety, and dignity of nonhuman animals. To some degree, such campaigns reflect moral claims on behalf of animals while simultaneously making moral arguments for punitive sanctions against those who abuse them. While we point to this as another example where the prisoners’ rights and animal protection movements could be at odds, others have argued more strenuously that not only are such measures ineffective, but also are counterproductive to the larger cause of animal rights. As Professor Justin Marceau has observed, “the logic of increased attention to crimes and penalties for individual animal abusers actually reinforces hierarchies and perpetuates larger-scale animal abuse and exploitation caused by corporations.”Footnote 77 While we acknowledge this patent tension, we see this as yet another area where cross-movement collaboration and discourse could lead to revisitation of such reflexive carceral approaches to animal cruelty.

17.5 Overcoming Disenfranchisement

A major element of social justice is redressing imbalances in political power. Frequently, public interest lawyers focus their work on reviving power for their clients where it has been lost and enabling power where it never existed. This is consistent with the ultimate objective of client empowerment, which decentralizes power to individuals to advocate for themselves. Ironically, client disenfranchisement frequently steers advocates toward the courts, which are somewhat independent of the political system and are, by some measures, already designed to account for protection of those without political power.Footnote 78 However, for a variety of reasons, advocates sometimes overlook the limits of litigation as a tool for social change.Footnote 79

With regard to incarcerated or formerly incarcerated persons, disenfranchisement is both formal and sweeping. Many states’ laws deprive people who have been convicted of a felony of their right to vote, not only while they are incarcerated but even after they have completed the terms of their sentence.Footnote 80 In some states, even those convicted of misdemeanors may lose their voting rights.Footnote 81 Although some of those states have established mechanisms to allow people to regain their voting rights, such systems have been widely criticized for long delays, for cumbersome or arbitrary administrative processes, and extremely low success rates.Footnote 82

No fair discussion of prisoners’ rights can ignore the deep connection between incarceration and race. Indeed, the prisoners’ rights movement began as an outgrowth of the activism of Black Muslims, who organized incarcerated persons and asserted their rights through activism and litigation.Footnote 83 In the US prison system as of 2018, Black men were incarcerated at a rate 5.8 times that of white males.Footnote 84 Not surprisingly, then, the disenfranchisement of formerly incarcerated persons has had and continues to have a substantially disproportionate impact on people of color.Footnote 85

But support for reenfranchisement of formerly incarcerated persons seems to be increasing. According to a 2018 Huff Post/YouGov poll, 63 percent of Americans support the restoration of voting rights for persons incarcerated for felony convictions after they have completed their sentences.Footnote 86 In that same year, nearly 65 percent of Florida voters approved a ballot measure to amend the state constitution to restore voting rights to most persons convicted of a felony after completion of their sentences.Footnote 87 Some 85,000 persons filed formal requests to have their voting rights restored pursuant to the amendment. The Florida legislature soon pushed back, enacting a statute that interpreted the amendment’s phrase “completion of all terms of sentence” to include not only a prison sentence and terms of parole, but also the payment of any amount of restitution, fines, and fees ordered by a court to be paid as part of a sentence.Footnote 88 Those provisions were immediately challenged in federal court. As of now, the law has been upheld by an en banc decision of the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, meaning that a substantial number of otherwise qualified persons were probably unable to vote in the 2020 election.Footnote 89

Through executive action, New York and Iowa have taken steps to narrow the impact of disenfranchisement. Under New York law, the Democratic governor issued an executive order in 2018 to restore voting rights to persons who had completed their prisons sentences, but were still on parole.Footnote 90 And in Iowa, which previously had permanently barred voting for anyone convicted of an “infamous crime,”Footnote 91 the Republican governor issued an executive order restoring voting rights for most convicted persons who have completed their sentence, probation, and parole.Footnote 92 Unlike Florida, Iowa does not require such persons to pay any restitution to their victims before regaining the right to vote.Footnote 93

Turning to the animal movement, nonhuman animals, of course, have no recognized legal rights, much less the right to vote in elections, and it is difficult, of course, to understand how it would work if they did.Footnote 94 But we might think of disenfranchisement for these purposes not only as the denial of formal voting rights, but also as the exclusion from all forms of participation and representation in the political system. And political advocacy for the interests of animals is surely imaginable, even as it must necessarily be undertaken through surrogates, such as animal rights groups that engage in lobbying and policy reform, or official ombudspersons. But query whether the current framework for permitting or encouraging such advocacy is sufficient. As one commentator has noted, animals are a politically powerless constituency, one of the factors the Supreme Court considers in evaluating whether heightened judicial scrutiny should apply to laws that discriminatorily burden such groups under the Equal Protection Clause. “The political powerlessness of animals [is] more than evident. . . . [T]hey are completely disenfranchised due to linguistic barriers. Some may argue that they are derivatively represented by animal rights proponents, but this seems a lackluster form of democratic participation without real bite.”Footnote 95 And yet, even in countries that have legally recognized animals as sentient beings, such status does not confer full political rights.Footnote 96

Cause lawyers in the prisoners’ rights and animal protection movements might consider mechanisms of reenfranchisement as a point of comparison across movements. Some states, for example, have ombudspersons for prisoners to serve as a representative voice to advocate for their interests. Similarly, some countries have established ombudspersons to represent the interests of animals.Footnote 97 The effectiveness of such measures depends to a large degree on the scope of ombudspersons’ powers and the degree to which they may participate in different types of government proceedings, from judicial to administrative to political. Movements could identify what features are essential to an effective ombudsperson and what types of limitations hamper their ability to adequately assert the interests of the powerless.

Another important point of comparison could be the relative merits of different advocacy tactics to combat disenfranchisement. As in other areas of public interest law, there are serious questions about which tactical approaches to advocacy are most effective, and there is ample room for a full investigation of the limits of such tactics. A conventional approach to social movements over the past half century might at least first look to rights litigation in the federal courts, which earlier movements have counted on to achieve progress for politically powerless constituencies. Setting aside for a moment the substantive question about the source and scope of rights for incarcerated persons and nonhuman animals, the idea of a litigation-centric, rights-based approach to protecting these groups fits within what we might characterize as traditional or “old school” models of social reform. Turning again to Carolene Products,Footnote 98 the Supreme Court observed in its famous footnote 4 that courts might have to be more vigilant about safeguarding the rights of underrepresented minorities. The Court recognized that it did not need to decide “whether prejudice against discrete and insular minorities may be a special condition, which tends seriously to curtail the operation of . . . political processes ordinarily to be relied upon to protect minorities, and which may call for a correspondingly more searching judicial inquiry.”Footnote 99 But this footnote has been understood by subsequent cases to imply just that point – that groups that are politically unpopular, disenfranchised, or both may be structurally unable to redress their grievances through ordinary political processes, and therefore are more deserving of more aggressive judicial interventions.

Both incarcerated persons and nonhuman animals can certainly be described as discrete and insular minorities who are unlikely to be able to achieve meaningful policy change through ordinary political processes. In the case of prisoners, the “special condition” that impedes their ability to pursue ordinary political processes is, as we have seen, formal disenfranchisement and resistance to reinstatement of voting rights. (The same is true for noncitizens, and one arguable justification for treating both groups as outsiders is that their status is, for the most part at least, not thought to be based on immutable characteristics. But whether justified or not, the exclusion from political participation is stark.) For animals, there has never, of course, been any formal political power, so they are situated similarly to other groups that have always been excluded from the political process. For these reasons, both groups might seek to employ impact litigation to achieve meaningful law reform, and in the case of animals, there is no possible rejoinder of them having been guilty of misconduct that might be true for some convicted felons or loyalty to another government that might be true for some noncitizens. On the other hand, as many commentators have observed, reliance on litigation as a long-term tactic for achieving social reform has perhaps not been as successful as we might imagine. Pathbreaking cases such as Brown v. Board of EducationFootnote 100 and Roe v. WadeFootnote 101 are quite rare, and rather than effectively embedding rights in our constitutional firmament permanently, frequently instead lead to resistance in their implementation and substantial, and often quite effective, backlash.Footnote 102 These responses reflect the potential instability of a litigation-centered approach to reform.

And litigation approaches to reenfranchisement are subject to additional substantial barriers in both movements. In the context of persons who have been convicted of felonies, in addition to the complexity of footnote 4 theory as applied to a class of people defined not by who they are or what they were born with but rather what they did, the text of the Fourteenth Amendment implicitly contemplates the removal of voting rights by States. Section 2 provides that states will not be penalized regarding their proportional representation in Congress if they deny the right to vote to persons engaged in “rebellion, or other crime.”Footnote 103 And the history of the Reconstruction Amendments is in line with this understanding. It would therefore be difficult, if not impossible, to argue for a federally required constitutional right to vote for formerly incarcerated persons. In theory, it would be possible to win a constitutional challenge recognizing the legal rights of nonhuman animals, but that would require that they be deemed “persons” within the meaning of the Constitution’s text, which is also highly unlikely.

Thus, despite the arguments that might be drawn from footnote 4 of Carolene Products, it would seem that, at least with regard to voting and other participatory rights, other social change tactics would be more effective and sustainable. One might look at recent democratically driven successes in prison reform and view them as reason for hope that mobilization, community organizing, and policy advocacy are among those effective options. The initial success of the Florida movement to restore voting rights to the formerly incarcerated, as well as a more receptive public, at first blush suggests that there are realistic tactical options to address reenfranchisement for prisoners. Of course, because this movement suffered almost immediate backlash from the Florida legislature, advocates turned to the state and federal courts to block efforts to dilute the amendment. But this type of litigation is reactive and serves a more complementary role to the underlying mobilization strategy, as opposed to the litigation model, where the courts are the primary venue in which advocates seek change. Other signs of political mobilization in the prisoners’ rights movement may be seen in the surprisingly bipartisan cooperation that led to enactment of the First Step Act of 2018, which reformed federal criminal justice system by, among other things, reducing mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent crimes, softening the federal “three strikes” sentencing requirements, and instituting some measures to improve prison conditions.Footnote 104 Though these do not directly relate to enfranchisement, they represent the possibility of political and policy reforms advancing other related rights for prisoners and former prisoners.

What about nonlitigation efforts to improve the welfare of animals? Here, we have witnessed only mixed success, and none of the reforms has come close to addressing animal disenfranchisement. The most prominent piece of federal legislation regarding animals is the federal Animal Welfare Act (AWA), which establishes some legal standards for the protection of animals used for research and exhibition.Footnote 105 Enacted in 1966, the AWA has been praised as an important foundation setting minimum standards for human treatment of nonhuman animals. At the same time, it has been widely criticized on the ground that the definition of “animal” is so narrow that it does not cover treatment of farmed animals or many animals commonly used in animal experimentation, provides those who work in the animal industry with cover that makes their activities less transparent, precludes efforts at stronger animal welfare legislation, and diminishes meaningful public discourse about animal rights and welfare.Footnote 106 Legislative reform also occurs, of course, at the state and local level, and here groups such as ALDF have accomplished some success addressing discrete animal welfare issues in a number of jurisdictions.Footnote 107 If some of this success can be directed toward legal recognition of surrogates such as ombudspersons to represent animals’ interests in the political and judicial process, it could promote at least some enfranchisement for animals.

17.6 Conclusion

In this chapter, we have attempted to establish a typological model for comparing cause lawyering across different social movements that share a common goal of challenging carceral logics in the United States. This is a very limited snapshot, but we hope to promote further discussion, not only about comparisons between the prisoners’ rights and animal protection movements, but also between and among other social movements. Moreover, we do not mean to suggest invisibility, moral suasion, and disenfranchisement are the only important factors to compare. Indeed, other researchers could address a range of other considerations that might yield rich and interesting comparisons across movements, including availability of resources, reliance on rights-oriented approaches to reform, and the comparative life stage of different movements, to name a few. We hope that this chapter will prompt further academic discussions and that such comparisons may, in turn, promote open and candid dialogue among cause lawyers associated with different movements to generate an appreciation for the value that can be drawn from such a comparative approach.