On 12 October 1912, Alexander Grechaninov's opera Sister Beatrice had its premiere in Sergei Zimin's Private Opera in Moscow. Based on a play by Maurice Maeterlinck and directed by Pyotr Olenin, the opera is set in a medieval convent and centres on a statue of the Virgin Mary that comes to life, initiating a series of miracles and wonders. The reviews reveal high expectations placed on the opera, and the Christian imagery of the work elicited constant slippages between the vocabularies of religious art and late-romantic ‘art religion’. Critic Yuri Sakhnovsky begins, ‘Art is life. Life is the search for God.’ Monumental religious artworks have testified to this search across history, and he lists the Hagia Sophia, J.S. Bach's cantatas and the sacred music of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Grechaninov and Sergei Rachmaninov as evidence. ‘Parallel with purely ecclesial [tserkovnaia] music’, he writes, ‘there has always been a striving to write operas either on the lofty events of sacred history, or even on sacred legends, where the essence of Christian dogma is vividly expressed.’ Sister Beatrice, he hoped, would follow the two ‘crowns’ of this tendency: Richard Wagner's Parsifal, for ‘Catholic Western Europe’, and Rimsky-Korsakov's The Legend of the Hidden City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya, for ‘the Slavic Orthodox world’. When these works are performed, he writes, ‘the theatre transforms into a church, where [the public] goes to pray, and not to seek entertainment’.Footnote 1 Sakhnovsky does not make the reference to prayer and dogma lightly; he was himself a composer of sacred music, and his Cherubic Hymn had earned a place in the repertoire of the prestigious Synodal Choir.Footnote 2

If Maeterlinck's Sister Beatrice represented to critics ‘a most beautiful and alluring plot in the highest degree for an opera of exactly the type of Parsifal and Kitezh’,Footnote 3 then Grechaninov seemed uniquely qualified for this task. A former student of Rimsky-Korsakov, Grechaninov had one successful opera under his belt, which dealt with Russian folkloric material, and a major Maeterlinck setting would complete his trajectory towards increasingly modernist and mystical texts. Grechaninov was also one of the leading composers of the so-called ‘New Direction of Russian Church Music’, a musical synecdoche for the widespread culture of Orthodox revivalism in late Imperial Russia.Footnote 4 This ‘New Direction’ had resulted in the unprecedented flowering of liturgical music and a robust culture of sacred music concerts in which Grechaninov's music featured heavily. Such deep investment in sacred music promised both a stylistic fluency for the representation of religious mystery on stage and a degree of spiritual sincerity. Grechaninov's Beatrice, however, failed to meet the high expectations placed upon it. Mainstream music critics claimed that it failed to capture the mystery of Maeterlinck's original, while conservative commentators levelled claims of blasphemy for its presentation of religious content. The production was cancelled after three performances. This critical and commercial flop, however, reveals a highly charged intersection of late romantic and symbolist operatic aesthetics with the concerns of Orthodox theology and piety: the dilemma of whether and how to represent the sacred or otherworldly on stage and in sound.

In what follows, I reconsider the heady spiritual atmosphere of the Russian Silver Age (1890–1917) into which Beatrice entered, beginning briefly with the wildly successful 1906 spoken production of the play by the modernist director Vsevolod Meyerhold and the charismatic actress Vera Komissarzhevskaia. I then turn to what critics such as Sakhnovsky considered the direct precedents for Grechaninov's opera, Parsifal and Kitezh, both of which forced critics and censors to engage with questions of how and where the sacred could be displayed in the years surrounding Beatrice's premiere.Footnote 5 I analyse two moments of Grechaninov's opera – the one most derided by critics and the one most lauded – within this context. In these scenes, Grechaninov takes different approaches toward embodying the divine in music, drawing alternately upon operatic convention and liturgical practice. Although Kitezh, Parsifal and other spiritually inclined operas are often considered within the context of ‘art religion’ or the appropriation of religious imagery,Footnote 6 Grechaninov's status as a leading composer of sacred music invites a more thorough consideration of the theological and liturgical backdrop for his opera. In this opera based on the animation of a statue and suffused with angelic voices, Orthodox ideas of the ‘spiritualisation of matter’ and the theology of angels are particularly relevant. I draw upon Silver Age thought in these areas to offer a fresh perspective on these operatic tropes, one that would have been available to Grechaninov's own interpretive community.

Finally, the opera's swift disappearance has spawned myths that it was ‘taken’ from the stage by the Holy Synod, the highest church authority in Russia.Footnote 7 Drawing upon new archival evidence, I offer a more nuanced picture of the censorship surrounding Beatrice, both before its performance and after it reached the stage. Joining recent scholarship that has considered Russian Imperial censors as competent and engaged individuals,Footnote 8 I demonstrate that the agents of church and state were indeed co-participants with composers and critics in discussions of how and where the sacred could be displayed. Furthermore, the opera, which included the imagery and musical signifiers of both Roman Catholicism and Russian Orthodoxy, forced commentators and censors to reckon with the very question of where the line between sacred and secular lay in Orthodox Russia. The case of Beatrice not only illuminates the often-opaque official processes surrounding a work's path to (and from) the stage, but also reveals the convergence of administrative, aesthetic and religious questions in the Russian Silver Age.

The ‘unheard music’ of Sister Beatrice

Maeterlinck's Sister Beatrice was introduced to the Russian public in 1906, when Komissarzhevskaia and Meyerhold transfixed audiences with their symbolist, spoken production of the play. Set in a convent in thirteenth-century Louvain, the play tells the story of a novice named Beatrice. The first act finds her, entrusted with guarding a statue of the Madonna overnight, being seduced by a local prince, Bellidor, who convinces her to run away with him. Before succumbing, Beatrice prays to the Madonna: if the statue gives the slightest sign of reproach, she will not go away with Bellidor. The statue, who looks remarkably similar to Beatrice herself, gives no sign. The second act begins with the statue coming to life and stepping from her pedestal to take Beatrice's place. The Madonna meets a crowd of beggars and supplies them with miraculously plentiful provisions. The other nuns take the Madonna for Beatrice, but when they discover that the statue has gone missing, they blame Beatrice–Madonna for its theft. Just as the nuns and a priest are about to punish Beatrice–Madonna, angelic voices break into song, flowers fall from the sky, and the walls of the convent begin to shake. The accusers reverse their course and decide that Beatrice–Madonna is a blessed bringer of miracles. The final act opens twenty years later as the statue returns to its pedestal and the real Beatrice returns to the convent. She confesses that Bellidor had quickly abandoned her and that she had led a life of sin and destitution, but the nuns refuse to believe her, claiming that Beatrice had been with them the entire time. The aged Beatrice dies in the adoring arms of the sisters, leaving the true miracle undiscovered.

The play is typical of Maeterlinck's sparse, static style. The miracles in the stage directions fill some of the gaps left by the dialogue; the most notable of these directions comes in Act II and describes heavenly voices singing the Marian hymn ‘Ave maris stella’. The second stanza of this hymn beautifully encapsulates the miracle at the centre of the play: ‘Sumens illud Ave / Gabriélis ore, / Funda nos in pace, / Mutans Hevae nomen.’Footnote 9 The transformation of ‘Eva’ (Eve) into ‘Ave’ (i.e., the word spoken to Mary at the Annunciation) is the transformation from the archetypical ‘fallen’ woman to the archetypical pure Virgin, set aside from original sin. This is an almost hieroglyphic summary of Beatrice's replacement with the Madonna, perceived as a transformation by the other characters. In Meyerhold and Komissarzhevskaia's production, Komissarzhevskaia is double cast as Beatrice and the Madonna, further emphasising the Christian typological impression. The wordplay of the hymn relies on the arbitrary relationship between letters, words and meaning – true symbols in the Peircian senseFootnote 10 – which also captures the play's refusal to signify beyond its surface.

With an enigmatic hymn at the heart of the play, it is fitting that Beatrice was received in musical terms. Maeterlinck himself claimed that the play was intended not for moral or philosophical messages, but to provide a ‘suitable theme for lyrical effusion’.Footnote 11 The music critic Iulii Engel reacted, ‘One must listen to that music, which flows unheard from each scene of this masterpiece.’Footnote 12 The influential symbolist writer Andrei Bely referred to the Meyerhold–Komissarzhevskaia production as a ‘complex chord of light blue, gold, green, ruby tones, [and] indistinguishable sounds’,Footnote 13 and the critic Georgii Chulkov called it a ‘musical act [deistvie]’.Footnote 14 Though there was in fact heard music in the production – three incidental numbers provided by Anatoly LidadovFootnote 15 – it was its unheard music that captured critics’ imaginations. For Russian symbolists, unheard music was invested with high metaphorical, even metaphysical value, which often dissipated upon entering the sounding world.Footnote 16

Maeterlinck's aesthetics, as Lydia Goehr has written, offered something of a riposte to the ‘external, totalizing, or symphonic condition of musical artifice’ of Wagner's Parsifal in favour of a ‘so-called inexpressible expression of interior musicality’.Footnote 17 Meyerhold and Komissarzhevskaia likewise sought to ‘preserve the implicitness of expression’Footnote 18 through long pauses, hushed speech and stylised, rhythmic gestures, and it was precisely this quality that gave it its ‘musicality’ in the Silver Age mind. The production was a model of the practice known as uslovnost’, or ‘conventionalisation’, which Dassia Posner has described as ‘a structural philosophy of theater-making that generates expectation, surprise, and thought by rejuvenating and reapplying how theatrical conventions are used’.Footnote 19 Though the term had once held a pejorative ring for Russia's realist generations of the mid-nineteenth century, symbolists such as Valery Briusov brought it into vogue as they reacted against naturalism in the theatre.Footnote 20 Beatrice received ecstatic praise for its brand of uslovnost’, pulsing with a musicality that never fully disclosed its mystery.Footnote 21

Grechaninov was in the audience when Komissarzhevskaia brought the production on tour to Moscow with her Petersburg troupe in 1907. He found himself ‘enchanted by the penetrating performance of the great actress’ and decided that the play was perfect for an opera. He notes his task: ‘unheard music already flows from each scene of this masterpiece: only listen and attempt to bring this music to life’.Footnote 22 But even as Grechaninov strove to listen to Maeterlinck's unheard sounds, the legacy of Parsifal and Kitezh, as well as his own experience writing liturgical music, would loom large in his attempts to bring Beatrice's interior music to life.

Grechaninov's brush with symbolism

The years between Russia's revolutions (1905 and 1917) were crucial for musical modernism at large, and it was during this time that Grechaninov's interests began to shift from a conservative, academic style towards contemporary aesthetic trends.Footnote 23 The clearest sign of Grechaninov's change in artistic predilections is his choice of poetry for his solo vocal works during this period. After setting texts by Alexander Pushkin and Alexei Tolstoy, as well as ‘ethnographic’ folk songs earlier in his career,Footnote 24 Grechaninov turned increasingly to Heinrich Heine, the French symbolists and the Russian symbolists. Friends and colleagues considered Grechaninov's aesthetic shift as contrary to his ‘purely Russian nature’, which had produced music ‘so simple, direct, national, and epic-lyrical’ to that point.Footnote 25 Nadezhda Salina, the soprano who had created the role of Nastas'ia in Grechaninov's first opera, Dobrynia Nikitich, associated the changes with events in the composer's personal life. She notes that this ‘new Grechaninov’ had divorced and remarried, changed his wardrobe, and ‘in his new works the Russian style that was natural to him had disappeared and an alien, forced exotica had appeared: Sister Beatrice, Les fleurs du mal on a text by Baudelaire and so on’.Footnote 26 Though Grechaninov showed equal interest in texts by Russian symbolists, his critics treated his new aesthetics as a form of Western European decadence. Boris Asafiev (under the pen name Igor Glebov) wrote of Grechaninov's turn toward these texts simply, ‘of course, nothing good came out of this’.Footnote 27

Grechaninov was drawn to symbolist texts but seems not to have updated his musical language accordingly. Asafiev reserves the harshest critique for moments when Grechaninov ‘illustrates’ individual sections of text without regard for the overall tone of the text. He approaches texts ‘from the outside’, with ‘descriptiveness’, at times employing a series of ‘descriptive formulas’.Footnote 28 Critics had once praised Grechaninov's pictorial flair in his sacred settings of Biblical narratives,Footnote 29 yet these symbolist texts demanded subtle suggestion, not mimetic representation. Asafiev's comments on the setting of Viacheslav Ivanov's tryptic At the Well sharpen the focus regarding what symbolist poetry held for Grechaninov. While Asafiev is critical of the stereotyped fanfare in the final song, ‘Christ is Risen’ (Khristos voskrese) – one of Grechaninov's descriptive formulas, perhaps – he gives the other two songs in the tryptic a more sympathetic reading. Of ‘Beneath the Cyprus Tree’ (Pod drevom kiparisnym), he notes that Grechaninov's setting ‘gave the stylisation of the sacred verse a radiance of true faith’, and ‘The Well’ (Krinitsa) had the austerity of a church chant, ‘not too strict, but somehow unique, sweet in Grechaninov's way’.Footnote 30 Grechaninov was not ‘stylising’ a sacred verse, as Ivanov had, however. His chant-like melody was one of countless he had written, but most were set to actual sacred verses, that is, liturgical hymnody. Grechaninov must have experienced a shock of recognition when he read the poetry of the symbolists, which often drew upon Christian sources. But if mysticism was a characteristic of style for the likes of Ivanov, it lay at the heart of the subject matter Grechaninov selected.

Although Maeterlinck had dissuaded his audience from seeking a moral message in Sister Beatrice, Grechaninov found one. At the foundation of his opera on the text, he claimed, lay ‘the idea of love and total mercifulness’, and he sought to ‘imbue it with lofty religious feeling’ through his music.Footnote 31 In further contradistinction to the Meyerhold–Komissarzhevskaia production, he claimed that his music was ‘more real[istic] [real'na] than Maeterlinck demands, and therefore all uslovnost’ should be reduced in the production’.Footnote 32 For Grechaninov, there was no paradox in approaching mystery and miracle as realistic. Whereas Meyerhold and Komissarzhevskaia's aesthetic in Beatrice was predicated on unsayability, the language Grechaninov had honed in his sacred music sought to illustrate and explicate mystical ideas and events, and he brought this approach into the opera house with his Beatrice. As we will see, the Dramatic Censors and the Holy Synod, ironically, preferred Meyerhold's approach. Grechaninov wanted to pull back the veil, while the Church wanted to protect the mystery. For symbolists, the veil was quite often the point: its presence actually generated the mystery.

The Grail, the Grad, the statue, and the Synod

For Grechaninov, the path from sacred music to symbolist texts like Sister Beatrice was paved with religious themes and imagery, and his writings indicate that this path led in both directions. In an article in 1900, he had sparked one of the more heated discussions of the New Direction by insisting on a mutable boundary between sacred and secular music.Footnote 33 In the article, ‘A Few Words on the “Spirit” of Church Singing’, he wrote that the most important criterion for sacred music was ‘the correspondence of the musical content of a given composition to the content of the text’, even if it led the composer to opera for inspiration.Footnote 34 Some operas, he argued, contained ‘music entirely appropriate for church’ resulting from their own ‘lofty stor[ies]’. His example: Wagner's Parsifal.Footnote 35

As Marina Rakhmanova has demonstrated, Grechaninov put this belief into practice in his sacred masterpiece, Passion Week, which premiered just after his Beatrice and has found an enduring place in the choral repertoire internationally.Footnote 36 Rakhmanova describes a ‘dramaturgy’ that unfolds against a liturgical progression from Good Friday to Easter Sunday in Passion Week, a temporal setting similar to that of Parsifal.Footnote 37 The ‘Wagnerism’ goes further: the motivic concordance at the words taina/tainaia (‘mystery/mystical’, also the word for sacrament) in ‘Now all the Powers of Heaven’ (Nyne sily nebesnyia) and ‘At Thy Mystical Supper’ (Vecheri Tvoeia tainyia) bears clear resemblance to the Grail motif/Dresden amen in Lohengrin and Parsifal.Footnote 38 The most unmistakable parallel is between the procession of the Grail Knights at the end of Act I of Parsifal and ‘Noble Joseph’ (Blagoobrazynyi Iosif) in Passion Week, which share a bass ostinato. Perhaps this association occurred to Grechaninov because of Joseph of Arimathea's mythic association with the Holy Grail.Footnote 39 Though the cycle is full of motifs redolent of traditional liturgical chants, the melody of ‘Noble Joseph’ stands out as the only recognisable pre-existing chant melody set in full.Footnote 40 It seems that Grechaninov treated the chant as a relic; like the Grail, it survived intact, borne reverently, unlike a leitmotif or imitation chant that was pliable and could be manipulated without fear of damaging its aura.

For Grechaninov, Parsifal, Passion Week and Sister Beatrice were all linked by the themes of transformation, redemption and suffering.Footnote 41 This linkage, made by the composer himself, can be expanded to include Kitezh, which operates within a similar thematic constellation and shares Parsifal's liturgical sensibility – its ‘inclination to ritual and tableau’,Footnote 42 an association made by both Silver Age critics and more recent scholars.Footnote 43 Taken together, these works question not only the relationship between liturgy and opera, but also the impact of national and confessional difference on how the sacred was defined in Russia. As Grechaninov's article suggests and Beatrice demonstrates, he sought to actively undermine such distinctions and would eventually write a large-scale Ecumenical Mass.Footnote 44 The critic Boris Popov, however, represents what might be considered a more common view among the Russian opera-going public. Like other critics, he juxtaposes ‘Catholic’ Parsifal with ‘Orthodox’ Kitezh, but qualifies that the latter is ‘not the Orthodoxy of Nikon and Avvakum, not the Orthodoxy of the Synod, but the Orthodoxy of John of Damascus, Seraphim of Sarov, Simeon of Verkhoturye, the Orthodoxy of Francis of Assisi — so all-embracing, so unexpectedly reconciling all cults, all times, and all peoples in a bow before the mystery of life and its Source, but not naming Him’.Footnote 45 In this litany of saints, he includes both Russian Orthodox and Roman Catholic figures, as well as a church father who lived before the 1054 schism between the churches. This version of Orthodoxy is distinct from Catholicism but is broad enough to subsume its traditions under a ‘sacred canopy’.Footnote 46 The Holy Synod itself took a similarly broad view of the sacred when it came to guarding against blasphemy; both Parsifal and Kitezh were subject to cuts from the authorities in the years surrounding Beatrice's premiere.

Wagner, wishing to preserve the mystique of Parsifal, had forbidden its performance outside Bayreuth until 1914;Footnote 47 ironically his attitude was similar to that of the Russian Orthodox Church, which sought a monopoly on the same imagery that permeated the opera. In the years leading up to Parsifal's first Russian performances, these forces conspired against would-be productions, a drama that played out at high levels in the church and state. In 1913, Count Sergei Sergeevich Tatishchev, head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which oversaw the Dramatic Censors, wrote to Vladimir Sabler, Chief Procurator of the Holy Synod, seeking approval for the opera's Russian premiere.Footnote 48 Since staged works needed to be approved only by a local bureau of the Dramatic Censors, Tatishchev was under no official obligation to secure Sabler's approval.Footnote 49 This is rather an example of what Paul du Quenoy refers to as the ‘unofficial censorship’ the Church exercised over the theatre.Footnote 50 Sabler, who proved to be a more imposing force than his famous predecessor, Konstantin Pobedonostsev,Footnote 51 seemed to have enjoyed the last right of refusal when any questionable content was proposed for the stage.

Tatishchev's letter notes that in August 1912 the Dramatic Censors had prohibited the planned premiere of Parsifal at St Petersburg's Theatre of Musical Drama the following year, on the grounds of the ‘religious character of the legend serving as the basis of the opera’. The administration of the theatre sought a second consideration after making unspecified edits to the Russian-language libretto and clarifying that their aim was merely ‘artistic–aesthetic’ rather than religious – meaning that no offence to the Church was intended.Footnote 52 Sabler, after reviewing the revised libretto, responded that it was ‘unconditionally necessary’ to redact several words, ‘removing the possibility of confusing the faithful with words that have direct relation to the Mystery of the Eucharist’. He also stipulated that it was ‘necessary to remove all possibility of disturbing the religious sentiment of Orthodox viewers’ in the way it was staged, ‘for example, during the blessing of the bread and wine on the altar, the cup ought to, in agreement with the text, be crystal and not like the chalice used by the Orthodox Church’.Footnote 53

The Holy Synod feared that the opera was so close to the true faith that it would ‘disturb’ or ‘confuse’ believers. For others, Parsifal's proximity to Orthodoxy meant that it could actually nourish the faith of those who heard it. Alexander Dmitrievich Sheremetev sought the rights for the Russian premiere for his Musical Historical Society for this very reason. Sheremetev had already been granted approval in 1903 for an unstaged performance,Footnote 54 and he claimed that even in its concert version it ‘created an altogether strong and indelible impression, arousing the listeners’ best religious feelings’. He believed that, if ‘staged in a serious manner’, the opera would ‘create an even greater impression in listeners and play a remarkable role in the raising of moral and religious feelings’.Footnote 55 Sheremetev received permission from Tatishchev, despite the exclusive permission the Theatre of Musical Drama had received, provided that the edits demanded by Sabler were implemented and that the size of the hall and price of the tickets prevented the performance from ‘bearing any sort of popular character’.Footnote 56 Sheremetev's company thus gave the Russian premiere of Parsifal in December 1913.

Sabler was incensed. He wrote to Nikolai Alekseevich Maklakov, the new Minister of Internal Affairs, that the production was ‘confusing the religious sentiment of Orthodox viewers in the extreme’. He pointedly reminded Maklakov of his earlier demands for edits to the libretto, adding that ‘the kneeling prayer, the raising of Parsifal's hands, and his blessing of the chalice in the third act created a particularly disturbing impression’. Sabler stopped short of insisting that the opera be kept off the stage altogether, but asked Maklakov ‘to take appropriate measures to eliminate … everything that is capable of causing temptation for the faithful, excited by the appearance of a singer in clothing and visage reminiscent of Christ the Saviour’.Footnote 57

From the exchanges between the impresarios, censors and Chief Procurator, it is clear that the Theatre of Musical Drama's insistence on its ‘artistic–aesthetic goals’ is in opposition to what was the unspoken priority for Parsifal's defenders and detractors: the religious and moral disposition of the Russian people. While Sheremetev and Sabler disagreed sharply over whether the opera would elevate or disturb the people's morals and faith, it is also clear that Sheremetev's claim of the loftiness of the opera's music was not in question. What Sheremetev believed would make the strongest impression, and what Sabler was most shocked by, were what was seen on stage. Ironically, it was the Holy Synod that anticipated the Marxist criticism of the ‘false, overcompensating objectification of the noumenal’ in Parsifal,Footnote 58 not because of phantasmagoric cloaking of labour, but because Wagner's fetishised objects bore a striking resemblance to its own sacred ones. This made the operatic commodification of holy objects all the more dangerous.

Kitezh, like Parsifal, drew simultaneous praise and censure for its visualisation of the sacred. The libretto itself made generous use of religious sources, particularly the vita of Saint Fevroniya. While the librettist, Vladimir Belsky, considered renaming the heroine to obscure her saintly roots, Andrei Nikolayevich Rimsky-Korsakov, the composer's son, thanks the loosening of print censorship in 1906 for the freedom to retain her name.Footnote 59 When the pendulum swung back in reaction, however, it was not the name that drew the attention of the Synod, but rather the ‘sacred processes’ that transpire on stage, as an anonymous writer for the periodical Music reported in January 1912.Footnote 60 A few months later, the production had been altered. Again, in Music:

Listeners to Rimsky-Korsakov's Tale of the Invisible City of Kitezh on 30 October in the Mariinsky theatre were significantly surprised by changes in the staging of the final scene. Previously this scene, depicting Kitezh under the water, gave an astonishing impression of something unearthly: the stage was saturated with white light, the snow-white clothing of the participants, standing in a circle – all this evoked a reverent feeling. Now the scene has been changed, and the impression has been decreased by half. The participants stood not in a semi-circle, but in some sort of square, and among the snow-white clothing appeared brown, greenish and other colours. The Holiness of the scene has disappeared. In public they have said that this scene has long disturbed the Synod, finding that it should be changed.Footnote 61

Grechaninov had written to Rimsky-Korsakov in 1906, praising his teacher's ‘miraculous’ opera for this very scene, as well as the scene of Kitezh's transformation at the end of the first act, which left him ‘in rapture’.Footnote 62 Apparently, Chief Procurator Sabler had attended the celebrated production, score in hand, and had decided that the scene was inappropriate.Footnote 63

As in Parsifal, it was precisely the appearance of holiness in Kitezh that generated excitement among theatre-goers and anxiety in the Synod. The writer for Music lambasted ‘the fathers’ for their ‘most unbearable sanctimony’, wondering why they should choose to go after the ‘genius Kitezh’, which ‘could not create any impression other than an elevated one’. If they were to act as a ‘moral censor’, he wondered, why not root out ‘pornography’, which was rampant in society?Footnote 64 There are two obvious answers, however, depending upon one's degree of cynicism. The first relies on an old Biblical principle of typology: the more convincing an imitation of holiness is, the more dangerous it is and the greater its potential to lead believers astray.Footnote 65 This was Sabler's argument against Parsifal and, if the reports in Music are to be believed, the argument against Kitezh.Footnote 66 A less generous interpretation is that the Synod attacked Kitezh not because its religious imagery would mislead the Orthodox conscience, but simply because it threatened its own monopoly on the sacred.

The same report in Music also claimed that Grechaninov's Sister Beatrice had been pulled from the stage in order for ‘the spheres’ to determine whether or not the opera's ‘pure and serene plot’ was appropriate for performance.Footnote 67 While the post facto censorship of Beatrice is a historical rumour worth fuller explanation, the opera's long road to the stage, including its experience with the Dramatic Censors, is worth adumbrating before turning to its reception from the Church and the press. The first problem that Grechaninov encountered when attempting to have Sister Beatrice staged was intellectual property, which Maeterlinck guarded (though not as jealously as Wagner). After completing composition of the opera, Grechaninov learned that the playwright had given the French composer Gabriel Fabre the performance rights to use the work as a libretto.Footnote 68 (A similar dilemma caused Rachmaninov to halt work on his final opera, Monna Vanna, another Maeterlinck project.Footnote 69) Grechaninov would not be stopped easily. He travelled to Paris to track down Maeterlinck and secure his permission. Though he was ultimately disappointed not to gain an audience with the playwright, he did meet with Maeterlinck's wife, who assured him there would be no objections to the opera's performance in Russia.Footnote 70

The next hurdle was the self-censorship of the Mariinsky Theatre. After being approved for the following season by a panel that included Alexander Glazunov, Caesar Cui and Sergei Taneyev in May 1911,Footnote 71 Grechaninov learned from Vladimir Arkad'evich Teliakovsky, director of the Imperial Theatres, that this decision would be overruled due to the ‘anti-religiousness of the plot’. Most of all, eyebrows were raised that the ‘Mother of God’ would be acting on the stage.Footnote 72 In keeping with attitudes toward its precedents, what made Beatrice ‘anti-religious’ to some was precisely what made it religious to others, including in this case Grechaninov himself. Alongside seeking a performance venue and experiencing pre-emptive ‘censorship’ from Teliakovsky, Grechaninov went through the official process of submitting his libretto to the Dramatic Censors. In the Moscow Gazette he bemoaned this process, writing that his inclusion of sacred language and hymns in the opera was specifically for the ‘elevation’ of ‘religious feeling’, while operas with no such ‘Christian foundation’ were free to use expressions such as ‘alleluia’.Footnote 73 These frustrations, he admitted however, were the ‘usual protests’ one receives from the censors.Footnote 74

If the responses of the censors were routine, this makes them all the more useful for discerning habitual practices of parsing what was and was not appropriate for the stage. By the time Grechaninov sent his own handwritten libretto to the St Petersburg Dramatic Censors, several versions of the work had already been screened. Though the version used by Komissarzhevskaia passed through the censors in the brief window of liberal attitudes after the 1905 uprising,Footnote 75 the censors’ conditions for approval were significant enough to give Alexander Blok serious pause about attending the premiere. Blok claimed that they had ‘butchered the subtle play, forbidding its designation of “miracle” on the advertisement, crossing out many important lines and the very name of the Madonna, and, most importantly, forbidding the Madonna to sing and come alive on the stage’.Footnote 76 The exact copy of M. P. Somov's translation submitted by Komissarzhevskaia's theatre prior to the 1907 premiere has not been preserved, but Blok's description squares with the censors’ copy of the same translation submitted in 1911. This is among three versions dating back to 1903 that precede Grechaninov's libretto in the Dramatic Censors’ archive, and like all of them, the character of the Madonna is changed simply to ‘woman’, while any text that would identify her specifically as the Madonna is excised. In all versions, the statue is taken out of the stage directions; though characters can refer to a statue, it cannot be shown.Footnote 77

National and confessional differences, too, play out in the various translations of Beatrice reviewed by the censors. In the 1903 version, the name ‘Madonna’, not typically used in Russian religious discourse, is regularly crossed out – indicating that the word was not too Western to confuse audiences as sacred – yet ‘pater’ was written in as an acceptable alternative to the Russian sviashchennik (‘priest’).Footnote 78 Such changes in nomenclature seem to have been meaningful in distinguishing what exactly constituted the sacred, as Tchaikovsky's The Maid of Orleans had faced very similar modifications three decades earlier.Footnote 79 The 1911 translation by M. V. Pechet received similar treatment. Most interesting in this case is Pechet's decision to translate the Madonna into Bogomater (Mother of God) and Prichistaia Deva (Purest Virgin), the terms Russians would be more accustomed to hearing in a religious context, indicating that at least for him Maeterlinck's Western Catholic mystery was translatable in Orthodox terms.Footnote 80 All these texts were approved, provided they implemented the revisions required by the censors.

The exact authorship of Grechaninov's libretto is unclear. He claims in his memoir that he worked from Jurgis Baltrusaitis's translation, adapting the ‘simple prose’ into ‘metered prose’ and consulting the French original when necessary.Footnote 81 In a contemporaneous article, however, he claims to have translated the work himself, and the version he submitted to the censors in 1911 makes no attributions other than to the children's choir at the beginning of Act II, which is translated from the French by S. Rafalovich.Footnote 82 If Grechaninov did work from another translation, it was likely one that had already gone through the censorship process, as he anticipates some of the key adjustments they would require: the ‘Madonna’ character, for example, is renamed simply as ‘Pious Woman’ (Blagochestivaia zhenshchina). Nevertheless, the libretto still required significant revisions before approval. As in Parsifal and Kitezh, body language and clothing had to be modified to avoid false sanctity; references to Beatrice kneeling are stricken, as are references to her monastic garb. When Beatrice appeals to the statue of the Madonna, the exclamation ‘Oh, my Mother’ (O, Mat’ moia) is crossed out, and any mentions of the Madonna or the Purest Virgin, which both appear in this translation, are crossed out. As Grechaninov notes with irony in his Moscow Gazette article, the Latin text of the hymn ‘Ave maris stella’ and the word ‘hosanna’ were crossed out, but the Slavonic text of Psalm 50 – Grechaninov's own addition – was left untouched, perhaps accidentally.Footnote 83

This last amendment is perhaps the most significant, as the hymn animates the entire scene of ‘Beatrice's ecstasy’. Judging by the reviews of the opera, it seems that Grechaninov ignored this condition, as Meyerhold and Komissarzhevskaia had before him. Similarly, the director Pyotr Olenin seems to have disregarded the most fundamental of the censors’ tweaks to the stage directions: the removal of the statue of the Madonna from sight. Olenin, famous for his theatrical realism,Footnote 84 instead placed the statue at the very centre of the stage. This drew derision from Engel and, later, Grechaninov in his memoires.Footnote 85 Engel compared this to Meyerhold's placement of the statue at the side of the proscenium, where it was barely visible. Meyerhold and Komissarzhevskaia had pleased both critics and censors by keeping the most sacred imagery (literally) behind the curtain, where it could retain an air of mystery and meet the conditions of piety. The concerns of the censors, whether heeded or not, foreshadowed the aesthetic strengths and weaknesses of Grechaninov's opera. Though the censors tried to eradicate the sacred hymns, these choruses were lauded by the critics as the most successful moments of an overall unsuccessful opera. On the other hand, the director's decision to present the statue in full view corresponds with the most persistent critique of the opera: its explicitness deflated the Maeterlinckian mystery. This deficit is felt most strongly in the scene of transformation, when the miracle becomes at best magic, or at worst kitsch.

Transformation music

The scant scholarly attention Grechaninov's Sister Beatrice has received has focused primarily on his use of leitmotifs and the few instances of modernist harmony that seem a better fit with Maeterlinck than the majority of the score.Footnote 86 Paisov has deftly identified the most frequently used leitmotif in the opera as self-citation from Grechaninov's setting of Charles Baudelaire's ‘Hymn’ (not to be confused with ‘Hymn to Beauty’), in Les fleurs du mal, in which the poet refers to his addressee as an angel.Footnote 87 The leitmotif, which Pyotr Karasev calls the ‘monastery theme’,Footnote 88 is rather nondescript, however, and critics claimed that many such themes were ‘pale’ or ill-suited to the ideas they accompanied.Footnote 89 Rather than the introduction of leitmotifs, it is their development and application that reveals how new the technique is to Grechaninov. For Sakhnovsky, their use is ‘mechanical’ and they often recur ‘almost unchanged’.Footnote 90 Another reviewer surmises that Grechaninov's stylistic transition was ‘purely external’ and his old realist roots were not far below the surface.Footnote 91 As the ensuing analysis will confirm, Grechaninov was neither a true Wagnerian nor a true symbolist: his is an aesthetic of the concrete.

Paisov and Morrison have also highlighted the music of the final act, as Beatrice approaches death. Morrison calls this ‘mystic Symbolist music’,Footnote 92 and Paisov notes that Beatrice's ‘confessions’ scene could rival the harmony of Stravinsky and Prokofiev in its chromaticism.Footnote 93 These moments are exceptions in the score, which conform more to what a symbolist opera ‘should’ sound like than to Grechaninov's overarching aesthetic. I will focus, rather, on the moments that are most exemplary of this aesthetic. Engel was right when he wrote that Grechaninov ‘illustrates’ rather than ‘recreates’ Maeterlinck, a response in keeping with reactions to his song settings of symbolist poetry.Footnote 94 As Engel notes, ‘these illustrations are not always free from “artificiality”’.Footnote 95 This unsuccessful pole of Grechaninov's realism will be my first focus, exemplified by the transformation scene.

The transformation of the Madonna's statue into living flesh is the miracle upon which the entire plot of Beatrice is based. If the moment has operatic precedents in Mozart's Don Giovanni and Dargomyzhsky's The Stone Guest,Footnote 96 its significance in Christian thought is even deeper. The miracle of incarnation, of Christ's physical birth on earth, is foundational to Christian dogma. The ability of God to take physical form enables an understanding of communion that is common to both Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy: by the power of the Holy Spirit, the bread of communion is turned into the body of Christ. This religious backdrop, though certainly present in Western Europe, is greatly amplified in Russia during the Silver Age. Vladimir Soloviev (1853–1900), the most influential Russian philosopher of the era, developed the idea extensively, arguing that the task of humankind is ‘the joint spiritualization of matter and the materialization of the spirit’.Footnote 97 As pertains to human art, he saw its goal as the continuation and perfection of the beauty of the natural world, and he placed music in the first of three orders of art.Footnote 98 He describes this order as ‘direct or magical, when the deepest internal conditions, connecting us to the true essence of things and with the unearthly world … breaking through all circumstances and material limitations, find direct and complete expression in beautiful sounds and words’.Footnote 99 This moment in Sister Beatrice thus provides an opportunity to illustrate the process of ‘spiritualization of matter’ and, in putting the mystery of the moment into perceptible sound, embody the ‘materialization of spirit’.

The transformation sequence begins at the end of the upstage children's chorus that starts the second act. The quick tempo and the D flat mixolydian tonal area of the chorus collapse into a slow passage based on the whole-tone scale at Rehearsal Number 63 (Lento e molto misterioso), bridged by a common tone in the children's choir over an orchestral rest. It is a clear sectional division, distinguished by key, time signature and harmonic material, and Grechaninov provides a stage direction to confirm the importance of the dramatic moment introduced by the music: ‘As if after a long, miraculous sleep, the statue of the Mother of God (Bogomateri) comes alive and descends the steps from the pedestal.’Footnote 100 The following thirteen bars comprise almost entirely whole-tone material, in a series of incomplete seventh chords (with the fifth removed) moving downwards in parallel motion. The flutes, in octaves, grab the ear's attention, outlining a whole-tone scale, step-by step (Example 1). Sakhnovsky considers this usage of a whole-tone scale to be misaligned with the miraculous. Such a passage in the hands of Rimsky-Korsakov, Vladimir Rebikov, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, he argues, conjures up the supernatural but is connected with ‘every “impure power”: wood-goblins, house-goblins, fauns, mermaids, but in no way the transfiguration of the statue of the Mother of God!’Footnote 101

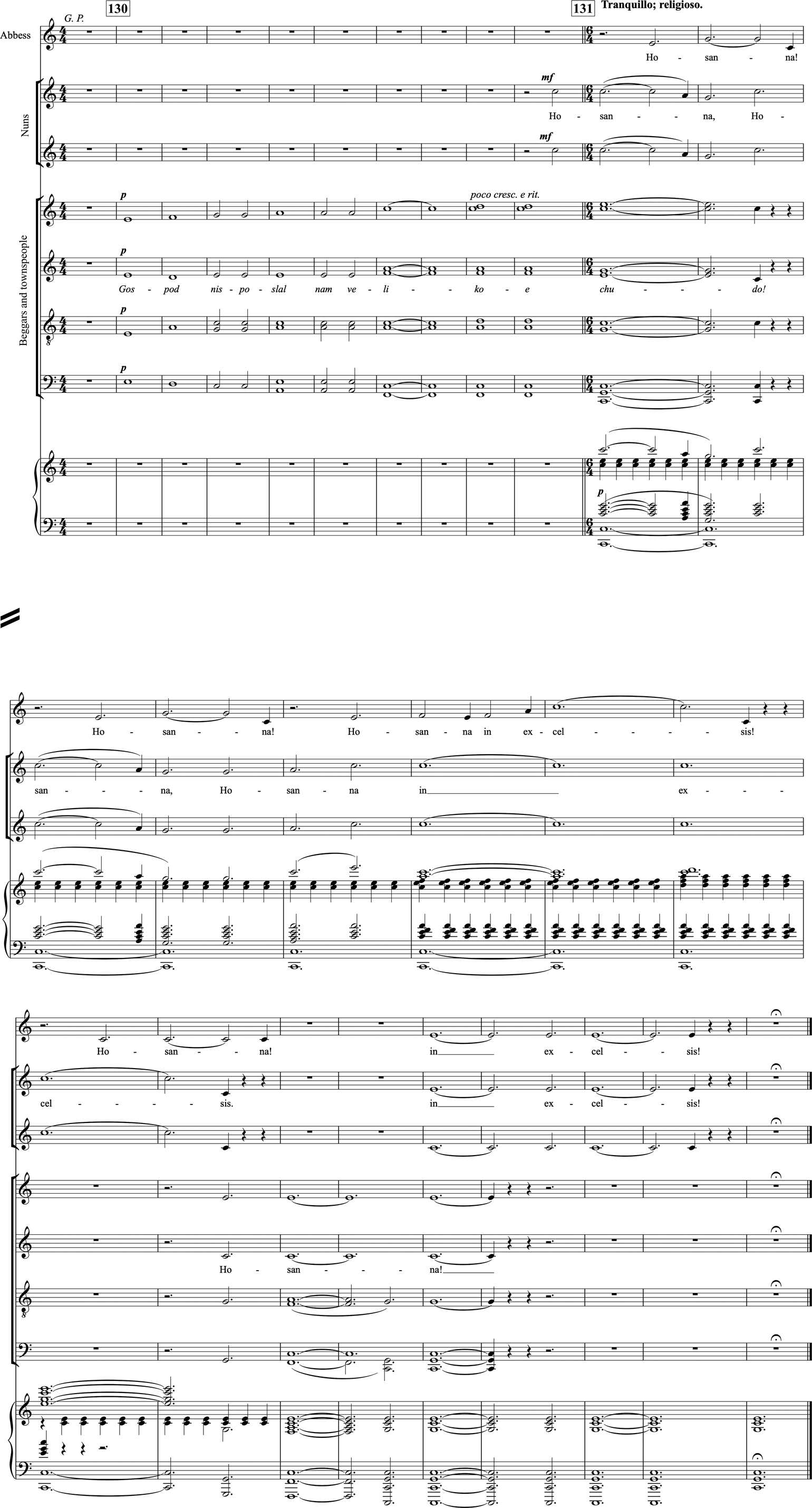

Example 1. Grechaninov, Sister Beatrice, Rehearsal Number 63, ‘Transformation music’.

Listening further to Grechaninov's transformation sequence, the seemingly misplaced harmonic material is not all that conveys the moment that the statue comes to life. At Rehearsal Number 64, between the sets of stage directions when the Madonna begins her descent from the pedestal and then dons Beatrice's habit, an arpeggiated diminished triad rises through the orchestra to the flute, which completes the gesture in a trill and an embellished warble (Example 2). The trill is conventional operatic rhetoric in this context, but it also had deeper philosophic valence in the Silver Age. Scriabin's piano sonatas, for example, are full of extended trills, which have been taken as signifiers of ‘human existence’ being ‘touched through divine illumination’, indicating a shared symbolic vocabulary.Footnote 102 Though the whole-tone progression leading to this moment feels strangely ossified, a closed harmonic world, the embellishment cracks this stone, introducing a melodic semitone for the first time in several bars. In the flute's high range above sustained strings, the tentative warble is the indication of a foreign element being introduced to the scene. Engel lamented that ‘only rarely is that breathing of the Holy Spirit felt, which in the language of sounds might at once and inscrutably communicate [priobshalo by] to the listener the essence of the mystery, thirsting namely for musical embodiment, accessible to the word only weakly and one-sidedly’.Footnote 103 In both Russian Orthodox and Roman Catholic understandings the Holy Spirit, which brought man to life from clay and transmutes the Eucharist for communion, is often depicted as a dove. Grechaninov's bird-like flute figure seems to gesture toward the spirit's descent into the statue, despite its somewhat clichéd presentation.

Example 2. Grechaninov, Sister Beatrice, Rehearsal Number 64, ‘Transformation music’, continued.

The shared conceptual framework of incarnation and communion also has a link to the musical rhetoric of Beatrice's most immediate precedent in Russian music, Kitezh. In Act IV, as Fevroniya is departing the material realm for the spiritual, she and the spirit [prizrak] of Vsevolod break bread together. He sings to her: ‘One who has tasted our bread / Has taken part [prichasten] in eternal joy.’Footnote 104 Like Engel's use of the verb priobshchat’, Vsevolod's use of prichasten connotes the sacrament of communion. Punctuating each of Vsevolod's lines are arpeggios in the solo violin, charting the same range as the flute in Beatrice, ending in a trill. Fevroniya's response cements the connection – ‘I am satisfied, and I sow the seeds for you, little birds, in the end I will regale you’ – and is accompanied by a trill in the flute, just a third lower than Grechaninov's. Her next line is also followed by a flute trill and the words complete the harmony of heaven and earth: ‘Lord Jesus, take me, settle me in your righteous dwelling’ (Example 3). Rimsky-Korsakov achieves a radiance far beyond Grechaninov's, with his more relaxed pacing and use of violin harmonics and occasional doublings across sections of the orchestra. Likewise, his use of clarinets and horns to iterate what Richard Taruskin has identified as a cousin of Wagner's Grail leitmotifFootnote 105 – which also seems to be the template for Beatrice's ‘monastery theme’ – provides a sense of depth to the scene and cathedral-like stability to counterbalance the effervescent violin ascent.

Example 3. Rimsky-Korsakov, Kitezh, Rehearsal Number 310–11.

Grechaninov approached Maeterlinck's text with the same attitude that Rimsky-Korsakov took for Belsky's, coordinating the concept of incarnation with sounds whose timbre and register seem to provide a link between heaven and earth. If Rimsky-Korsakov's communion scene music is a more integrated artifice of heaven, Grechaninov's transformation music aspires to take its place with opera's ‘disembodied voices … that trill from above, like Wagner's Forest Bird [or] Strauss's Falcon’.Footnote 106 These flutes all simulate a brush with the otherworldly. Yet Adorno's commentary on Parsifal, Beatrice's other direct predecessor, rings true here as well: ‘the phantasmagoria is transferred into the realm of the sacred which, for all that, retains elements of magical enchantment’.Footnote 107 Grechaninov intended to ‘bring to life’ the sound of the Holy Spirit; what resulted was a bit of magic, more akin to the scarecrow coming down from his post than the Madonna coming down from her pedestal.

The trading of mystical for magical in Beatrice's scene of transformation is most of all a result of Grechaninov's penchant for illustration when the moment calls rather for suggestion. In a moment such as this, the composer runs up against a problem that vexed many opera composers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the challenge of representing the divine or supernatural – in short, the unrepresentable.Footnote 108 In addition to the operatic tradition, however, Grechaninov's interpretative community was also steeped in Russian Orthodox liturgical experience. In the Orthodox liturgy, the descent of the Holy Spirit is a weekly affair, and the composers and critics of the New Direction also grappled with what sounds might accompany the miracle, known as the epiclesis. Very few composers made any attempt at representation. Indeed, Father Mikhail Lisitsyn, a priest, composer and prominent critic among the New Direction, cautioned against such renderings. Of ‘the moment of the hovering of the grace of God’, he writes, ‘[h]ere the human tongue should be silent, since word and even sound are powerless to communicate this mystery, this miracle of miracles’.Footnote 109 This was the choice of Meyerhold and Komissarzhevskaia, who kept the transformation hidden from sight (and sound). Grechaninov's explicit, mimetic approach achieved the transformation only of miracle into kitsch.

The ecstasy of Sister Beatrice

Although Engel criticised Grechaninov's penchant for ‘illustrating’, he admitted that at times there was ‘much of beauty in these illustrations’, and this is the case in the scene known as ‘Beatrice's ecstasy’.Footnote 110 Grechaninov uses ‘authentic’ (podlinnye) Gregorian melodies for the Latin angelic hymns,Footnote 111 as well as his own imitation psalmody for the Slavonic psalm text that he sneaked past the censors (Example 4). As in his more successful symbolist song settings, Grechaninov renders the scene in concrete musical terms, but the religious nature of his liturgical artifacts simultaneously captures the mystical quality of the miracle on stage.

Example 4. Grechaninov, Sister Beatrice, Rehearsal Number 85 (Psalm 50).

The psalm recitation serves as an ostinato, concluding the beggars’ chorus while also propelling it towards the first of a series of offstage choruses. The text, Psalm 50 in the Orthodox tradition, 51 in the Western, is a penitential one, asking for mercy from the subject position of an earthly sinner, sung here primarily by the basses. The offstage choir comes as answer. It is coded as otherworldly: high voices, disembodied, modal, comprised primarily of parallel unisons and open fifths.Footnote 112 Distinguishing it from the Slavonic and Russian preceding it, the text is in Latin: ‘Gloria tibi, Deus noster’. This recalls the Great Doxology, which is sung by angels announcing the birth of Christ in the Gospel of Luke, though the citation is inexact.Footnote 113 It is, however, a direct translation of the Slavonic prayers of praise that begin the All-Night Vigil, ‘Slava tebe, Bozhe nash’.Footnote 114 The austere harmonisation, like the imitation psalmody, would be at home in one of Grechaninov's liturgical settings, suggesting that despite the dramaturgical distinction between penitents and angels at this moment, distinctions between Western and Eastern Christianity are blurred here.

The plot point that takes a tediously long time to unfold between this taste of liturgical music and the grand choral apotheosis of the second act is the discovery of the statue's disappearance. When the abbess makes this discovery, she orders that Beatrice be punished (taking on the role of the priest, which Grechaninov eliminated) and the nuns lead her to the church for her penance, accompanied by a pompous funeral march that drew criticism from Sakhnovsky.Footnote 115 What stops the Madonna from being punished is the faint but sudden interruption of an offstage choir of unearthly voices, which in a spoken production would stand out easily from the fabric of the play. Presented with the operatic challenge of making the impending miracle evident to the listener, Grechaninov resorts to his magic trick, the flute figure from the scene of transformation. Again, its mechanistic, almost direct repetition is hardly evocative of the Holy Spirit, but it does seem to say to the audience, ‘look out for a miracle’.

The following sequence is one of the most aesthetically confounding in the opera, yet it also contains the key to an appreciation of it. The noumenal voices the censors tried to strike from the score sing ‘Ave maris stella’ to an authentic medieval melody in radiant, pseudo-medieval harmony.Footnote 116 This is punctuated, however, by the crudest imitative strokes in the opera: the use of melodic tritones in the brass within the orchestra's whole-tone harmony at a dynamic of fortississimo – the representation of the church walls shaking. When the whole-tone passage and subsequent flute gesture appeared earlier, they were an operatic approximation of spirit (flute with chromatic ornamentation) penetrating immobile matter (whole-tone orchestra). Here, the opposition is reconfigured. The flute gesture is linked to the blaring, wall-shaking music by their shared whole-tone material and instrumental (rather than vocal) timbre, as well as by their shared status as representational rhetoric. This music is opposed to the music coming from off stage: modal, vocal and representational not in the sense of Grechaninov's ‘illustrations’ but rather as a stand-in for angelic song (Example 5).

Example 5. Grechaninov, Sister Beatrice, Rehearsal Number 114, ‘Ave maris stella’.

It is after this opposition of orchestra and angels that the Latin hymn induces the breakthrough from the musical rhetoric of opera, representation and narration to that of liturgy, here in its most characteristic mode of doxology, or pure praise. The rest of the act is given over to choral acclamations of ‘Hosanna in excelsis’, which concludes the Sanctus in both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox liturgies. Drawn from the book of Isaiah, it is one of the oldest parts of the liturgy, and as Greek and Hellenised Hebrew, it subsumes the early opposition of Slavonic and Latin texts within a shared antiquity.Footnote 117 The Sanctus was believed to be angelic song, first revealed in Isaiah 6:3, and as Grechaninov's contemporary Sergius Bulgakov notes, this is the unending hymn of praise that is one of the hallmarks of angelic activity.Footnote 118 Furthermore, it was a moment when the congregation (or stand-in choir) joined in with ongoing angelic song.Footnote 119 Grechaninov models this participation throughout the remainder of the act as choral groups join in successively with what had begun as an offstage, noumenal voice.

Grechaninov's operatic realism earlier in the act failed to depict convincingly the embodiment of the Madonna through the Holy Spirit. Here, Grechaninov adapts his liturgical rhetoric more successfully to the stage with the gradual embodiment of disembodied song. The ‘beggars and townspeople’ sing ‘hosanna’ first off stage in two successive groups; the nuns likewise enter in two subgroups, singing alternately ‘Sister Beatrice is holy’ and ‘hosanna’; and after the nuns sing the last text that can be considered narrative, ‘God has sent down to us a great miracle’, all voices save Beatrice–Madonna's, which is silent, unite in praise. This embodiment of angelic song and turn to doxology occurs, according to Grechaninov's stage directions, as the doors of the church open and all the singers appear bathed in light, with flowers raining from above.Footnote 120 In both Wagnerian and Russian symbolist approaches to opera, offstage voices often sustain an impression of the uncanny or the ineffable.Footnote 121 Grechaninov begins the scene with this effect, but his decision to bring all voices on stage results in the exchange of mystical suggestion for the more concrete representation of sacred community.

In the concluding bars of the scene of ecstasy, a sudden grand pause – akin to what Ellen Harris labels ‘sublime pauses’Footnote 122 – followed by a final round of ‘hosanna’ signifies the apotheosis of the act (Example 6). The singers stand in awe as three withered, elderly guests enter. The Madonna washes the dust from their hands, using a golden pitcher and a clean towel, recalling handwashing rituals present in both Eastern and Western liturgies.

Example 6. Grechaninov, Sister Beatrice, Rehearsal Number 130 to end of Act II.

With this, the act comes to a close. Sakhnovsky had envisioned the theatre as a church when attending performances of Kitezh and Parsifal, and critics claimed that Meyerhold and Komissarzhevskaia had indeed transformed the theatre accordingly.Footnote 123 Grechaninov took a much more literal approach towards staging the sacred, using actual liturgical chants (and their simulacra), not only vividly representing miracle worship, but also presenting religious artifacts. It was this very desire to make the opera ‘more real’, however, that would lead critics at opposing ends of the cultural spectrum to condemn Beatrice to obscurity.

The disappearance of Sister Beatrice

Despite the praise Grechaninov received for the choruses of Sister Beatrice, the opera as a whole was considered a failure. Certain harsh responses and the opera's abrupt disappearance from the stage after only three performances have, however, added some mystique to the flop. As the writer for Music noted, when the staging of Kitezh was discussed ‘in the spheres’ of the Synod, Chief Procurator Sabler reportedly had his eye on Beatrice as well.Footnote 124 While Grechaninov himself set the text with a pious attitude, certain more conservative corners of the public found it blasphemous, contributing to a rumour that the opera was ‘taken’ from the stage by the Holy Synod. The conservative backlash to Beatrice is instructive for assessing the narrow course Grechaninov had to chart, but the evidence that the opera was actually stricken from the repertoire by the Church is far from conclusive. More importantly, the rumour allowed the composer to save face when confronted with negative reviews and an unenthusiastic public.

The harshest review came from the right-wing ‘political, social and church paper’ The Bell (Kolokol).Footnote 125 As predicted by the administration of the Mariinsky and the Dramatic Censors, what most angered the author was to place ‘the Visage (Lik) of the Mother of God – that Holy Visage, to which we bow’ on the ‘indecent’ stage. The author, who had recently eviscerated the Dramatic Censors for allowing Anatoly Kamensky's play Leda to be produced,Footnote 126 takes aim again at the local administration for allowing Beatrice:

What is being done in Moscow? Has it has fallen into the godless dissolution of Babylon, drawing the wrath of God upon Russia …? Who is ruling Moscow? What laws are in effect there? … The law of our Russian tsardom forbids the depiction on the stage of any sacred person in the very clothing assigned to them, it forbids the use of images of the cross or any other sacred action, and in Moscow they allow on the stage not only the material representation of the Mother of God, but even make Mother of God into a public comedienne.Footnote 127

Komissarzhevskaia's sinful soul was punished for her presentation of the play, he writes, and surely those who allowed this would be as well.

In his memoir, Grechaninov blames this review for the opera's short run. He claims that because of such reviews, ‘an extensive report was made in the Holy Synod, which expressed the opinion that the presentation of Grechaninov's opera Sister Beatrice in Zimin's opera should be forbidden’.Footnote 128 Based on the composer's account, the historical understanding is that a directive from the Synod put an end to the production.Footnote 129 But there is reason to doubt the account in Grechaninov's memoir. As in the complaint over the placement of the statue cited earlier, his explanation of the opera's disappearance is lifted directly from a contemporaneous report, without any citation (which could explain Grechaninov's awkward third-person reference to himself). His source was an unsigned note in the St Petersburg Market News (Birzhevye vedomosti), which claims this account was ‘related by an altogether trustworthy source’.Footnote 130 The Moscow paper News of the Season (Novosti sezona) relayed this report but retorted that they knew better in Moscow; Zimin pre-emptively cut the opera himself, due to its lack of popularity.Footnote 131 The censorship explanation was a persistent one, however. News of the Season printed another unsigned commentary a few weeks later, which in largely the same words as the Music report blamed the censors for both the disappearance of Beatrice and the modifications to Kitezh, though admitting it was the ‘influence’ of the ‘sacred circles’, rather than an ‘official decree’ that brought down Beatrice.Footnote 132

These rumours likely have some basis in fact: a copy of The Bell's review was collected by the Dramatic Censors.Footnote 133 Unlike the extensive battle over Parsifal, however, Beatrice's paper trail stops there.Footnote 134 Furthermore, many contemporaneous writers themselves seem to have a slightly hazy view of how the censorship process worked. Reports frequently blame the ‘Sacred Censors’ for the prohibition of a play or an opera,Footnote 135 although the Sacred Censors only screened works for print that were intended for religious use, while it was the Dramatic Censors who screened stage works. What they did understand, however, was the influence church officials like Sabler could wield to interfere with the work of the Dramatic Censors.

The tendency of the Chief Procurator to intervene in theatrical life in fact provides the most compelling evidence that this was not Grechaninov's fate. Two days before Grechaninov's Sister Beatrice began its three-day run, another composer, A. A. Davidov, received permission from the Dramatic Censors for his own setting of Maeterlinck's text, which would premiere two years later.Footnote 136 Sabler read a review of the premiere in Market News and, predictably, claimed that the opera would ‘create great temptation and confusion among the faithful sons of the Orthodox church’. Now that the war had begun, it was even more crucial that the Synod care for the ‘protection of the Children of the Orthodox Church from all that might disturb their religious conscience and moral sentiment’.Footnote 137 Sabler makes no mention of any previous action over Beatrice. Nikolai Maklakov, Minister of Internal Affairs, responds with reference to Grechaninov that this is the second time the play has appeared in operatic form and it ‘has never excited doubt in the sense of an anti-religious tendency’.Footnote 138 He also points out that the production has been modified to eliminate the statue altogether. If the Synod or the Dramatic Censors had indeed shut down Grechaninov's Beatrice, it is unlikely that the Chief Procurator of the Synod and the overseer of the Dramatic Censors would have forgotten about the affair two years later. Sabler's willingness to intervene, however, nevertheless lends credibility to the rumour.

As one of the News of the Season articles suggests, there is another more likely reason for Beatrice's disappearance from the stage: money. The income registers for Zimin's theatre tell a story similar to that of the reviews: a production that failed to live up to the expectations that marked its opening. When Beatrice premiered on 12 October 1912, on a double bill with Tchaikovsky's Iolanta, it grossed 3,346.43 rubles, the second highest total in October (in first place was Tosca, with 3,707.53 rubles). The mean gross income for the month was 1,992.04 rubles. The numbers for subsequent performances plummeted to 755.53 rubles and 958.13 rubles on 15 and 17 October, respectively. By the next scheduled performance, on 19 October, Beatrice had been replaced with Pietro Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana (still paired with Iolanta).Footnote 139 One of the more measured reviews blamed other harsh critics for scaring off the public.Footnote 140 Zimin's own journals attribute the cancellation to poor attendance rather than official intervention, though he claims that it was simply the length of the opera that bored audiences.Footnote 141

Beatrice's fate, it seems, was decided by a confluence of factors – aesthetic values, religious sensibilities, routine censorship – and it is ultimately this confluence that sheds the most light on how sacred and secular were negotiated in the Silver Age. In the cases of Parsifal, Kitezh and both Beatrices, the Dramatic Censors, the Chief Procurator of the Holy Synod and the conservative press all seemed to agree with the mainstream musical press and critics with symbolist tendencies that sacred images should not be directly displayed on stage. These productions and their paper trails also reveal a surprisingly loose definition of the sacred, as distinctions between Western and Eastern Christianity were worked out in the margins of set design and nomenclature. Censors and symbolists, it would seem, shared a common language. What Grechaninov's Beatrice helps expose to a greater degree than its precedents, however, are the limits to the mutual legibility this common language could guarantee. If Grechaninov's attempt at the ‘spiritualization of matter’ – his animation of the statue of the Madonna – was condemned in all corners, his ‘materialization of the spirit’ in the scene of ‘Beatrice's ecstasy’ split the opinions of the administrators and the aesthetes. Despite the censors’ attempts to keep hymnody off the stage, Grechaninov's embodiment of angelic song, and his presentation of sacred sounds and representation of liturgical community, gave critics a brief taste of the miracle they so longed for.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to several people for their generous time, support and feedback throughout the many stages of drafting this article, including Philip Ross Bullock, Caryl Emerson, Rebecca Mitchell, Simon Morrison, Jamie Reuland, Megan Sarno, Carolyn Watts and Michael Wachtel, as well as to the editors and anonymous reviewers of this journal. This research also is greatly indebted to the staff and archivists of the St Petersburg Theatrical Library and the Russian State Historical Archive.

Competing interests

The author declares none.