Introduction

The Department for Education (DfE) GCSE Subject Content for Ancient Languages embeds the study of literature as a significant requirement in the specifications of any Latin GCSE (DfE, 2018). Specifications are instructed to ‘require students to read a range of ancient literature, including at least one selection of prose and/or verse texts in the original language, adapted and abridged, as appropriate’ (DfE, 2018, p5). Furthermore, students are to be expected to respond to the literary style; show an understanding of the cultural and historical context; and compare and contrast ‘values and social practices from the ancient and modern worlds’ (DfE, 2018, p5). The two exam boards offering GCSE Latin, Oxford Cambridge and RSA (OCR) and Eduqas, take slightly different approaches to fulfilling these requirements. Both have a range of module options to choose from; however, OCR offers fewer choices of author in the original language (OCR, 2015), whereas Eduqas requires either six or ten different authors in its compulsory literature module (Eduqas, 2015).

Modern languages at GCSE level do not have this literature requirement as part of their assessment. Ancient languages sit alongside English Literature as the only GCSE subjects requiring students to respond to authored works as literature rather than as historical sources, or to extract information. The National Curriculum in England programme of study for Key Stage 3 English states that pupils should be taught to appreciate a range of literature and be equipped with the skills to engage with it critically (DfE, 2013). This means that pupils studying English Literature will begin their GCSE familiar with the type of task that will be required of them, and crucially will have engaged with literature that is at a similar level to that which forms part of their assessment. In ancient languages such as Latin and Classical Greek, the literature requirement does not occur until they have started their GCSE and it will often be introduced late in that course due to the need to have completed the majority of learning for the language components. Furthermore, the literature they encounter is of a very different nature to the texts which they are likely to have encountered up to that point if they have been following some of the more popular Latin courses, such as the Cambridge Latin Course or Ecce Romani.

Reading literature in the original language was one of the most engaging parts of my study of languages, and the chance to continue engaging with authentic texts and pass on my enthusiasm formed a great part of my motivation in deciding to pursue a career as a Classics teacher. Therefore, for this assignment I was keen to design a unit of work to investigate incorporating authentic texts into the current scheme of work that was being followed by the class.

National Context

Latin has been offered as a subject on the main curricula of an increasing number of schools over recent years, reversing a decades-long period of decline (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016). It remains nevertheless a minority subject. In 2018, the total number of entrants across the two exam boards for GCSE Latin was 9,297 (Eduqas, 2019; Taylor, Reference Taylor2019). Achievement is high, with 53.4% gaining the highest grades 8 or 9 with Eduqas and 64.5% gaining grades 8 or 9 with OCR (Eduqas, 2019; Taylor, Reference Taylor2019).

School context

My placement was an independent school in West Sussex. The school site has a pre-prep, prepFootnote 1 and senior school with a total of 1106 pupils ranging from age 4 to 18. Boarding starts in the senior school (Year 9) and around a half of senior school pupils are boarders for at least some of the week (ISI, 2016). The school population is predominantly white British. Under 15% of the pupils receive support for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (in line with national statistics) and at the time of the ISI compliance report in 2016 there was only a single pupil with a statement of educational needs or Education, Health and Care plan (EHC) (ISI, 2016)Footnote 2. In 2016 there were 26 pupils with English as an Additional Language (ISI, 2016)Footnote 3. The school reports achievement of 43.3% A*, 9 and 8 at GCSE in 2018.

Latin is studied in the prep school by all pupils from Years 5 to 8. Pupils elect whether to continue with Latin upon moving to the senior school in Year 9, where there is also an intake of pupils from other schools who may choose to take Latin if they have studied it before (or if they are prepared to put in ‘catch-up’ work over the preceding summer). There are three full-time Classics teachers in the department who also offer Classical Greek GCSE and Classical Civilisation A Level.

Class context

The class to whom I delivered this unit of work is a Year 10 Latin set of 15 pupils, comprising 11 boys and four girls. There are four pupils with learning support needs. The school operates a ‘challenge grade’ system whereby pupils are given the grade they are expected to work to, reflecting the GCSE grading system. In this class 13 of the 15 pupils have a challenge grade of 8 or 9; therefore, performance levels are high. The class have all chosen to study Latin at GCSE and largely express enthusiasm for the subject. They are studying for the Eduqas GCSE and have been following the reading approach using the Cambridge Latin Course (CLC), supplemented with additional material. They have not yet commenced study of the literature components of the GCSE.

Rationale

As outlined in the introduction, the study of literature in the original language forms a significant component of the Latin GCSE whichever examination board is followed. There is, however, no requirement for authentic literature to be studied outside of the relevant GCSE component. Therefore, the first time pupils are exposed to it could come in Year 10 or even Year 11. Hunt (Reference Hunt2016, p.126) comments on the difficulty of preparing students for reading the set texts. Cresswell notes that in her attempts to get pupils to engage with Catullus, the pupils had commented that they were ‘particularly daunted by the sophistication posed by the verse set texts’ which formed their initial encounter with Latin literature (Cresswell, Reference Cresswell2012, p.12). A solution could be to prepare the pupils for what is to come by giving them some exposure to some carefully selected examples of Latin literature which might tie in with the course being followed or at appropriate points of the year (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, pp.126-7). I designed this unit of work (UoW) for a Year 10 class as they would soon be beginning their study of Latin literature. The UoW would incorporate authentic texts into their language study alongside the reading course they were following. This would be used to fulfil the language objectives set out in the scheme of work while also introducing the pupils to something of the nature of authentic Latin so that it would not seem so unfamiliar when they encountered it in their literature module. Churchill (2006) describes using lines from Virgil to introduce and practise particular grammar points and I decided to incorporate this approach into the UoW.

In order to do this successfully it would be necessary to make sure that the material was useful for achieving the learning objectives. Selection of materials would be vital to ensure that they were comprehensible and that the content was suitable for what was being studied, both in terms of language content and thematic content. To bridge the gap between the level of Latin the pupils were accustomed to and the level in the authentic materials an appropriate level of scaffolding would have to be provided. I would also have to ensure that the resources were designed in a way to offer potential for differentiation so that the tasks would not be excessively daunting and so that there would also be a suitable level of stretch for the more able or faster-working pupils.

I was especially keen to design a unit of work around authentic literature as I find it one of the most interesting aspects of studying Latin. For all that the stories offered by reading courses can be engaging and exciting, there is no comparison with studying genuine literature and creating a connection to the past by reading someone's genuine words. My own experience chimes with Bernado's suggestion that authentic materials ‘are highly motivating, giving a sense of achievement when understood and promote further reading’ (Berardo, Reference Berardo2006, p.60). The literature components of the Latin GCSE and A Level courses tend to draw from a relatively narrow range of authors compared to the enormous variety that is available, therefore developing the ability to incorporate additional sources into my lessons would help me continue to widen my own experience as a teacher. The act of preparing resources based on the other sources of authentic literature would serve to enhance my own subject knowledge.

The reading approach

Courses following the reading approach to Latin teaching are the most popular in UK schools (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, p.35). The class I designed the UoW for have been following the Cambridge Latin Course (CLC). CLC was developed in the 1960s and the first edition published in 1970 amid a climate of change in educational theory brought about by the application of cognitive science (Gay, Reference Gay2003, p.74). A major influence on the development of CLC was Noam Chomsky and his theory of language acquisition (Gay, Reference Gay2003, p.76-77). Chomsky theorised that children have a Language Acquisition Device (LAD) which allows them to pick up language through internalising rules from hearing language spoken. He formed this theory in relation to first language development, but it was taken to be applicable for second language acquisition. The validity of this has been contested (Gay, Reference Gay2003). In a Latin course following the reading approach there is a continuous storyline in which vocabulary is restricted and language features introduced gradually, with the aim of helping the student to develop reading comprehension (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, p.38). A fundamental aspect of CLC is that ‘reading and understanding should precede grammatical explanation’ (Gay, Reference Gay2003, p.78). This restricted exposure to vocabulary and grammar poses something of a contradiction with the idea of introducing authentic Latin; however, Hunt points out that in practice most teachers following a reading course are not utilising a pure reading approach but supplement their teaching with other approaches (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, p.38). Lightbown and Spada (Reference Lightbown and Spada2013) argue against the sole use of formulated materials with a narrow range of vocabulary and grammar for language teaching, saying that while they may be appropriate when a language feature is initially introduced or requires some correcting, ‘it would be a disservice to students to use such materials exclusively or even predominantly’ (Lightbown & Spada, Reference Lightbown and Spada2013, p.209) as they need to be challenged and develop strategies to cope with what they encounter from other sources.

Definition of authentic materials

Authentic materials can be defined as materials which were created ‘to fulfil some social purpose in the language community’ (Little, Devitt and Singleton, 1989, cited in Peacock, Reference Peacock1997, p.146), i.e. they were not created for the purpose of language instruction as are the passages in a course like CLC. Beresova (Reference Beresova2014) questions whether material can properly be regarded as authentic when it has been taken away from its original context and audience. The issue of materials being outside of their context is worth noting; however, for the purposes of this assignment I am adopting the definition given by Little, Devitt and Singleton (1989). Nuttall (Reference Nuttall2005) advocates a degree of simplification (while retaining as much as possible); however the texts that the pupils will encounter in their GCSE are unsimplified. I decided for this UoW not to simplify the selected texts, but to use other methods (scaffolding and differentiation) to make them accessible.

Advantages of using authentic materials

A large part of the academic discourse around authentic materials has come from the world of modern foreign languages teaching, or the teaching of English as a foreign language (EFL). Therefore, I have drawn from the literature concerned with these fields, as well as that relating to the learning of ancient languages. Advocacy for the use of authentic materials goes back as far as the philologist Henry Sweet in the 1890s but gained in popularity from the 1970s with the rise to prominence of communicative language teaching (CLT) (Beresova, Reference Beresova2014). Morrell (2006) observes that despite widespread disagreement on most issues surrounding foreign language learning, ‘both theorists and practitioners are close to consensus on the need to use authentic texts as frequently and early as possible’ (Morrell, 2006, pp.144-5). He sets out the advantages as providing access to a rich source of cultural information, being engaging, and improving students’ abilities to derive meaning from texts (Morrell, 2006). Berardo (Reference Berardo2006) gives a similar list of the benefits of using authentic texts, with the further comment that they can also be used in a variety of ways to focus on different skills.

There are contrasting opinions. Devitt (Reference Devitt1997) says that the use of authentic material is regarded as having little value for beginners (a position with which, as a learner of languages, I personally disagree). Peacock (Reference Peacock1997) gives the example of some authors who have said that it may reduce learner motivation through being too difficult. This can be avoided by beginning with a limited exposure to authentic materials which will prepare them to cope with more challenging material (Morrell, 2006). This forms part of the basis on which I developed this UoW, which starts out with simpler materials and progresses to something more complex.

Disadvantages of using authentic materials

The most obvious difficulty in using authentic materials is their complexity of vocabulary and mix of grammatical structures compared to the carefully curated texts of a course like CLC. However, Nuttall (Reference Nuttall2005) points out that new grammatical features ‘often cause no problems if the text is comprehensible in other respects’ (Nuttall, Reference Nuttall2005, p.175). Indeed, as we have seen, this is the philosophy behind the reading approach followed by CLC. Word glosses can be used for unfamiliar vocabulary and can also be used by the learner to gain information about what the text is about (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016). The difficulty of a text can also be addressed by the nature of the tasks that are required of the students. A difficult text may suit a task that requires a more top-down approach, ‘in which intelligence and experience count for more than language proficiency’ (Nuttall, Reference Nuttall2005, p.192). The harder the text, the easier the task. Nuttall (Reference Nuttall2005) also recommends breaking up the text to prevent it from seeming too daunting. These are factors I have considered when designing the UoW, where I have assigned the students a range of different tasks according to the difficulty of the text and made an effort to present it in an appealing way. Berardo (Reference Berardo2006) notes that in order to use authentic texts effectively, time-consuming special preparation is required. Beresova (Reference Beresova2014) also notes that the use of authentic materials is demanding on the teacher due to having to plan and prepare the materials, but claims that the teacher will benefit ‘as preparing authentic materials for their classes will help teachers enhance their own language competence and deepen their cultural awareness’ (Beresova, Reference Beresova2014, p.203).

A major issue with authentic texts in language learning that is very applicable to the learning of ancient languages is that of the very different cultural circumstances in which they were produced. Widdowson (Reference Widdowson1996) says that learners of English have trouble dealing with authentic material produced by native speakers as ‘they belong to another community and do not have the necessary knowledge of the contextual conditions’ (Widdowson, Reference Widdowson1996, p.68). Kitchell (Reference Kitchell2000) describes how some students of Latin with a solid grasp on grammar can struggle when it comes to understanding authentic Latin. He attributes this to an unfamiliarity with the cultural background that is intimately bound up in some of the texts. He shows how dense an 11-line passage from Ovid is with references that require a considerable level of background knowledge. The solution offered to this is to provide that background information to the class by leading classroom discussions (Kitchell, Reference Kitchell2000), a solution with which Morrell (2006) agrees. I designed the UoW to take this into account and provide background knowledge, and in fact as much as a disadvantage I see this as a positive effect of using authentic texts, which supports the aim of the ancient languages GCSE subject content to enable students to ‘develop their knowledge and understanding of ancient literature, values and society’ (my emphasis) through the study of literature (DfE, 2018, p.3).

Selection of materials

Writers on the use of authentic materials for language learning agree that judicious selection of materials is essential. Peacock (Reference Peacock1997) warns that poor choice of material may reduce learner motivation. Therefore, when selecting material, a teacher must consider ‘whether the text challenges the students’ intelligence without making unreasonable linguistic demands’ (Berardo, Reference Berardo2006, p.63), a point backed up by Hunt when he warns against it merely becoming a ‘particularly difficult linguistic puzzle’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, p.125). The suitability of content also needs to be considered as you ‘need texts that will interest most of the students and not actually bore the others’ (Nuttall, Reference Nuttall2005, p.171). This makes it a careful balancing act to find texts that are appropriate both linguistically and in terms of content, particularly as in the UoW I also intended to make thematic connections to the existing scheme of work.

Motivation and engagement

One of the reasons behind my choice of authentic texts as a focus for the UoW was my own experience of having found them motivating and engaging. I have not found any studies of the effect of authentic materials on motivation in the Latin classroom. Berardo (Reference Berardo2006) reports on the outcome of an investigation into the use of authentic materials in the EFL classroom and states that the learners were initially not very motivated as the subject matter was not very stimulating, but that upon changing the material the students became highly motivated. Beresova (Reference Beresova2014) conducted an analysis of different types of authentic materials with EFL learners: academic texts, literary texts and newspapers. The students reacted positively to both the literary texts and newspapers, and Beresova (Reference Beresova2014) concludes with a strong recommendation for the use of authentic materials in the classroom for their positive affect on engagement. Both of these studies, however, were carried out in the EFL classroom; therefore, the students, while not sharing the full cultural knowledge of the society that produced the texts, were at least immersed within that society - which is a considerably different situation to the ancient language classroom. Additionally, these studies were carried out with students considerably older than the Year 10 class I was designing the UoW for. I have taken these as indicative that there could be a motivating effect of using authentic texts in the Latin classroom, but they are far from strong evidence. Dörnyei (Reference Dörnyei2001) states that ‘breaking the monotony of learning’ by utilising a variety of teaching strategies can contribute to motivation; therefore it could be speculated that the introduction of authentic texts could achieve a positive effect on motivation through this effect (Dörnyei, Reference Dörnyei2001).

As important as the authentic materials being a source of motivation for this UoW is, the aim of preventing the future exposure to set texts becoming a demotivating influence due to their difficulty. Dweck (1999) writes about students responding to difficulty with either a ‘mastery’ or a ‘helpless’ response. The response is connected to their self-theory rather than their intrinsic ability, as less skilled students can enjoy tackling a challenge while even some very high-attaining students can display a helpless response (Dweck, 1999). I have taken it as an essential aspect of this UoW to avoid generating the helpless response (whereby they begin to doubt their intelligence and feel overwhelmed and unable to tackle the task). I would achieve this by using scaffolding and differentiation. Hunt (Reference Hunt2016, pp.122-123) gives the reminder that the main purpose of using literature is to understand and respond to it, and that it may be a cause of demotivation and lack of engagement if students are left not understanding the story. Therefore, I would have to ensure that there was scope built in to the lesson plans to check comprehension and allow discussion.

Scaffolding

To expect students to be able to suddenly work with the full complexity of authentic Latin texts (particularly verse) after the simplified texts of the CLC would be to expect them to make a large leap in their ability. Vygotsky (Reference Vygotsky1978) claimed that learning occurs in a student's zone of proximal development (ZPD), the difference between what they can achieve on their own and what they can achieve with the guidance of a teacher or more capable classmate. To enable this, scaffolding can be used to support the students as the authentic texts are introduced, but can then be gradually withdrawn to encourage pupils to take on the challenge themselves. To scaffold the selected texts, I made use of word glosses, gap-fill and texts numbered in order of translation.

Differentiation

Despite the class being of overall high ability and mainly working towards grades 8 or 9 at GCSE, there is nevertheless a wide range in interest and readiness represented among the pupils. I would therefore have to ensure that there was a degree of differentiation in the work assigned. Tomlinson explains the rationale for differentiated instruction, saying that students learn best when teachers ‘effectively address variance in students’ readiness levels, interests and learning profile preferences’ (Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2005, p.263). To achieve this, I created the resources and planned the lessons to ensure that the introduction of authentic Latin would be done in such a way as to be achievable to all and yet provide a challenge to the higher-achieving students, thereby avoiding a lack of motivation caused by tasks being too difficult or too easy.

Differentiation in the classroom can be achieved in a number of ways. The methods I planned to use were differentiation by outcome using an ‘all, most, some’ approach; differentiation by product where the students would have the choice of task to undertake; and differentiation by input with additional resource and extension tasks being given to students as appropriate (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, pp. 58-70). A further form of differentiation, that of giving individual attention to students who were either struggling with the difficulty of the texts or who were moving ahead quickly, would be applied contingent upon the classroom situation (Nuttall, Reference Nuttall2005, p.174).

Unit of Work

As a result of my reading, I designed a unit of work consisting of six lessons, each of which at some stage of the lesson involves a piece of authentic Latin literature. The amount of literature built up over the series, from just a starter activity in the first lesson, to the main focus of later lessons. The literature was always presented with scaffolding and differentiation strategies to make it both achievable and sufficiently challenging for all. I also selected the texts for their content to be interesting and sufficiently engaging, as well as relevant to the grammar points being learned in CLC and, where possible, connected thematically.

Evaluation

An aim of the UoW was to give students exposure to authentic Latin texts before they encountered their set texts, as Cresswell (Reference Cresswell2012) and Hunt (Reference Hunt2016) observe that the study of set texts is many students’ first exposure to Latin literature. Cresswell (Reference Cresswell2012) notes that the students in her class were ‘daunted’ by the complexity of texts when they appeared, which could be a manifestation of the ‘helpless’ response described by Dweck (Reference Dweck2000), or that the increase in complexity put the text outside of the students’ ZPD and greater scaffolding was required to bridge the gap.

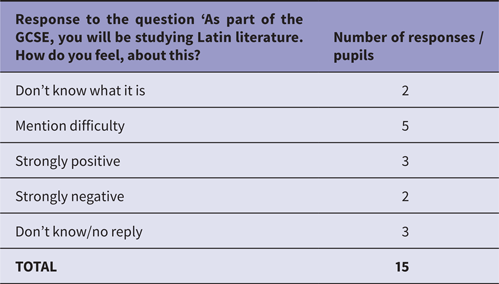

At the very start of lesson one, I gave the students two questions to answer: ‘What do you enjoy most about studying Latin?’ and ‘As part of the GCSE, you will be studying Latin literature. How do you feel about this?’ The responses are summarised in the table below:

What stands out to me in the responses is the lack of clarity about what is involved in the components that will make up 50% to their examination result (they are following the Eduqas specification and will take the literature option for Component 3) (Eduqas, 2015). This supports Hunt's claim about the set texts being the first exposure to Latin literature (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016). For me, this affirmed that the UoW was a worthwhile endeavour if it did nothing else but give the students a clearer idea of what they would be studying for the remainder of the course. I believe it succeeded in this respect as the students met several instances of unadapted Latin verse and prose, including two authors (Ovid and Martial) who appear among the authors of the ‘A Day at the Races’ option they will be studying for component 2 (Eduqas, 2015).

The reading approach

Hunt (Reference Hunt2016) says that the purpose of the reading approach is ‘to develop students’ abilities to comprehend original Latin’. Following a course such as CLC that uses the reading approach means that students are presented with a continuous storyline, vocabulary is restricted and grammar is introduced gradually (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016). However, they do not actually come across any original Latin unless the course is supplemented by the teacher. I found that it was possible to introduce unadapted authentic texts alongside the reading course in a way that supplemented the language and thematic content. Even though the students like the course, particularly the stories, I believe that this supplementation will enrich their experience of learning Latin. I believe this would be possible and worthwhile with lower years who might otherwise get through their whole Latin-learning experience without encountering any examples of real Latin. In that case I might think about focusing on inscriptions so that students could connect what they have learned to things in the real world around them.

Selection of materials

Peacock (Reference Peacock1997), Berardo (Reference Berardo2006) and Hunt (Reference Hunt2016) all claim that the selection of texts is of vital importance; therefore I made sure to select texts that I considered suitable in terms of the difficulty of the text, the enjoyableness of the subject matter and the amount of cultural background knowledge required. For the first lesson I chose a poem by Martial in which each line formed a discrete sentence, there was a lot of repetition, and the tenses were limited to present, perfect and one instance of the future which they would be learning about in the following lessons. As the UoW was being delivered around Christmas, for lessons two and three I selected passages from the Gospels of Luke and Matthew on the basis that they contained several instances of the future tense but were syntactically simple. Lesson three included the use of four short epigrams by Martial, each of which contained a verb in the future tense. The Martial and the passages from Luke and Matthew were selected to tie in with the study of the future tense and I was able to exploit them for activities related to this. For lessons five and six I used a passage from Ovid's Ars Amatoria about the trap set by Vulcan for Venus and Mars. This was selected as it is alluded to in the CLC Stage 33 story we were reading, and was thematically linked to the events of that story. I found that the texts suited the purposes for which they had been selected, and would make use of them in future, although with the passages from Matthew and Luke I would be careful to ensure that they were appropriate within the ethos of the school (I had confirmed this with my mentor prior to using these as texts).

Disadvantages of using authentic materials

Kitchell (Reference Kitchell2000) claims that unfamiliarity with the ancient cultural schemata is a significant impediment to students’ ability to work with and enjoy authentic texts, but that this can be remedied by leading the class in culturally relevant discussions. I found the lack of familiarity with cultural schemata to be an issue with the first Martial poem in lesson one as the students were unclear what they were dealing with (which I compounded by only giving them each a section of the poem to translate); however, when we looked at some other epigrams in lesson four, I set up the task with an explanation and some other examples with translations that allowed the pupils to not only complete the language objective of the task (identifying and translating verbs in the future tense) but also to enjoy the additional task of matching titles to the epigrams. Contrary to Kitchell's claim, for the sections from the Bible in lessons two and three no additional contextual information was necessary as the students were familiar with the characters and the events. For the Ovid passage I set up the background by reading the account of the story given in the Odyssey and got them to make notes which would help when it came to understanding the Latin story. I also included a picture of the event on the worksheet which I asked them to label and which they could refer to as a reminder when we came back to it in the second lesson. I found that the students were genuinely interested in the background information, so I do not see that the requirement to include it as a significant negative. It also supports the GCSE subject content requirements to enable students to ‘develop their knowledge and understanding of ancient literature, values and society’ (DfE, 2018, p.3).

Berardo (Reference Berardo2006) identifies unfamiliar/irrelevant vocabulary and too many grammatical structures as being among the difficulties with using authentic texts. I found that providing word glosses meant that the vocabulary posed no issues, as the students are familiar with using them in the CLC and I imitated the CLC style of giving them to the right of the text. I was also able to gloss some unfamiliar grammar, such as the passive infinitive and the perfect infinitive, and they did not cause any particular problems; in fact, they would soon be learning the passive infinitive so it was a useful opportunity to introduce them to the concept of something without focusing on it. I agree, therefore, with Nuttall (Reference Nuttall2005) that if a structure can be understood it is not necessary to avoid it or to spend time teaching it. For lesson four, the Martial epigrams were being used as an exercise in recognising the future tense; therefore complete understanding was not necessary, which supports Nuttall's view that difficult texts can still be used with a suitable task (Nuttall, Reference Nuttall2005).

Berardo (Reference Berardo2006) and Beresova's (Reference Beresova2014) claims that the preparation required is extremely time-consuming was confirmed by my experiences. To include scaffolding and differentiation, tailor them to a specific grammar point (the focus on future tense) or theme, and ensure they do not show excessive lexical complexity, time must be spent selecting the materials and then preparing suitable resources. I found these took longer to create than making resources completely from scratch and for a one-off activity I would doubt the value of the effort. However, having put the time in creating them, I have resources that can be used again. I certainly agree with Beresova's (Reference Beresova2014) point that the effort creating these resources is rewarded by an increase in my subject knowledge, both linguistically and culturally.

Motivation/engagement

Berardo (Reference Berardo2006) and Beresova (Reference Beresova2014) reported the use of authentic materials as having positive effects on motivation and engagement in the EFL classroom. I do not have a qualitative measure of the motivation and engagement of the students in the class, although from my subjective judgement there was a positive effect most of the time the materials were used. It may be significant that the instance picked up in my observation notes of significant off-task behaviour (a student watching football on their laptop) occurred during the work on the first Martial poem where I did not set up the context and students were not clear about what they were working on. The students appeared very interested in the task with the Martial epigrams, but it may have been because the task of matching the titles to the poems represented something different and not because it was real Latin. This could be seen to support Dörnyei's (Reference Dörnyei2001) claim that variety in teaching approaches and tasks is motivational. I also had an impression of engagement with the Ovid story of Mars and Venus. Some of the pupils in the class were very interested in mythology and it presented a good opportunity for them to share their knowledge and enthusiasm as well as to convey my own.

Hunt (Reference Hunt2016) warned of a potential for boredom and demotivation if students are not left with an understanding of the story. I made sure there was opportunity for a discussion of each of the texts that we studied, even when (such as with the Martial epigrams or sections from the Bible) they were being used principally as grammar exercises. I had the students discuss in pairs their response to what we had read and used questioning to ensure understanding. This ensured the pupils went away with an understanding of what we had been reading. Follow-up work in later lessons confirmed that they had retained some understanding of what we had been looking at.

Differentiation and scaffolding

Tomlinson (Reference Tomlinson2005) claims that students work best when teachers address their particular needs. I used a range of methods of differentiation in the lessons I delivered. For one of the poems by Martial I offered a choice of the original text or a version re-ordered to the word order they were more accustomed to dealing with, and by allocating sections to individual students to translate based on my perception of their ability and the complexity of the text. For another task I offered a choice of task of finding similarities or differences between two Latin texts or an easier ordering task. I was disappointed that so many chose the easier task even when it was my perception that many more of them would have been certainly capable of the harder task. Even the two that took on the harder task only did so after completing the other task. This made me question whether offering the choice of task to all was the correct thing to do. I had intended to avoid making any student feel singled out by being given something different, but I think that the result was the higher-attaining students taking on a task of insufficient challenge.

The passage of Ovid was selected for its thematic relevance to the story in CLC rather than the linguistic content and represented a challenging section of Latin verse. This therefore required heavy scaffolding to bring it within the students’ ZPD, and for some sections I gave the English translation rather than the Latin. The text was broken up into its constituent couplets, as Nutall (2005) suggested this could make it less daunting and better able to hold pupils’ attention. This was very successful, as it gave the appearance of manageable sections and made it easy to assign goals to the students (e.g. ‘I expect you to get to section D’). The first three couplets were to be completed as a gap-fill and for the first six couplets the words numbered in translation order. All scaffolding apart from word gloss was removed for the final couplets. All of the pupils were able to get past the gap-fill sections and many completed some of the couplets unsupported by anything apart from the word gloss.

Conclusion

The development, delivery of and reflection on this unit of work has been an extremely valuable exercise in my development as a trainee teacher. I was sure from early on that I wanted to incorporate the use of authentic materials into the assignment. Having concluded this piece of work, I am certain that it is also something that I want to take forward and make a feature of my teaching career. In fact, I would like to extend the practice to classes at an earlier stage in their Latin-learning journey as I believe they can be used with a range of abilities provided they are supported with scaffolding to enable comprehension. There will be a lot of work involved in achieving this, but I consider that doing so will be worthwhile in several respects. Creating the resources gave me the opportunity to reflect deeply on the texts and look closely at their content and context. Therefore, doing this will assist with the ongoing development of my subject knowledge in areas outside the set texts specified by the exam boards. The resources created will be re-useable and I have found that they that can be successfully deployed to supplement a Latin course such as CLC. The use of authentic materials will enrich the experience of the learners by adding variety to the course and deepening their knowledge of the cultural background of the subject they are studying. It may even encourage some students to continue their study of Latin.

I think it is of great importance that students are exposed to authentic Latin texts prior to the introduction of the set texts at GCSE. Considering it forms such a large part of the exam for many students, the earlier they begin to be prepared for what it involves the better, especially if it can be done in a way that supports their language learning. Doing so will give them some familiarity with what they will be facing and mitigate any potentially negative reactions to the increased difficulty of the language when they are encountered in that context.