Introduction

Institutionalist scholarship has recently begun to investigate the ways in which perceived legitimacy deficits of international organisations (IOs) create pressures for institutional reform. At the global level, the legitimacy of post-Second World War global multilateral organisations, such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization, and the United Nations, is being challenged for being unrepresentative of the voices, interests, and values of developing countries and their citizens. At the regional level, the legitimacy of the European Union has been perceived as declining over the last two decades and is currently in what some are calling a legitimacy crisis. This perceived legitimacy crisis of IOs has led to a lively policy and academic debate over the types of institutional reforms that might remedy the deficit and enhance legitimacy.Footnote 1 Indeed, IO legitimacy has received renewed attention as an important variable in explaining institutional change, a central concern of recent institutionalist literature.Footnote 2

Beyond the core insight that legitimacy can be a source of institutional change, however, we still know little about the conditions under which an IO is likely to suffer a perceived legitimacy deficit, when that legitimacy deficit is likely to lead to institutional change, and what type of institutional change we are likely to observe as a result. Consider, for example, that while the creation of parliamentary bodies has been a notable response to legitimacy concerns within regional IOs, there has been little movement to implement them at the global level,Footnote 3 despite a vast theoretical literature discussing the benefits of instituting global parliamentary assemblies.Footnote 4 Many proposals to enhance democratic legitimacy of global IOs envisage state-based elections for global parliamentarians in a way not dissimilar to the process in the European Union,Footnote 5 but proposals to create a parliamentary body within the United Nations in order to remedy its legitimacy deficits are often seen as radical rather than legitimacy-enhancing. Why are some institutional designs perceived as more legitimate than others, and why is the same institutional design sometimes perceived as legitimacy-enhancing in one setting and not in another? Moreover, in a world in which most IOs do not fully embody underlying societal values and norms, such as democratic participation and equal treatment, why do legitimacy deficits in some organisations lead to pressure for change while in others they are simply tolerated? What factors condition actor sensitivity to legitimacy deficits? These are important questions at a time when the post-Second World War liberal international order is increasingly challenged on legitimacy grounds.Footnote 6

We argue that in order to begin to answer these questions, we need to take into account the cognitive processes that shape legitimacy perceptions in the first place. Our purpose in this article is to use insights from the cognitive psychology literature to develop a cognitive approach to explain how legitimacy perceptions shape pressures for institutional change. The field of cognitive psychology has studied judgment formation for more than four decades and the resulting body of empirical findings has been applied to different settings of political decision-making.Footnote 7 However, the relevance of these findings for understanding organisational legitimacy thus far has not been systematically explored. We develop a cognitive account of organisational legitimacy and spell out some of its observable implications for institutional (non-)change. These implications, we posit, are distinct from implicit expectations within the existing legitimacy literature. Existing arguments about the consequences of legitimacy for institutional change, we argue, are underspecified and indeterminate in the absence of microfoundations that help explain how legitimacy judgments are formed. Existing approaches have difficulty explaining a range of complex cases, such as when an organisation is not under pressure to change even though we might expect it to suffer from low legitimacy, or cases in which an IO faces legitimacy pressures suddenly even though neither its design nor the values of its constituents have changed.

We take as our point of departure the insight that legitimacy concerns can be an important driver of institutional change. Indeed, we show that the organisational legitimacy literature has a particular model of institutional change – what we call the congruence model – implicitly embedded within it (Section I). According to this model, incongruence between societal values and an organisation’s procedures, purpose, and performance will lead to a loss of legitimacy and, consequently, to pressures for institutional change. But this account, we argue, is too coarse; it fails to appreciate the perceptual, and therefore cognitive, nature of legitimacy judgments. In order to better capture the dynamics of organisational legitimacy, it is necessary to provide legitimacy judgments with microfoundations (Section II). From these cognitive microfoundations, then, we can develop propositions about the conditions under which an incongruence between societal values and organisational features is likely to lead to legitimacy loss, and the conditions under which legitimacy loss is likely to lead to institutional change (Section III).

I. Legitimacy as an explanation of institutional change

What explains change in institutional design both within IOs and across IOs over time? This question has become a central concern of recent institutionalist literature in International Relations (IR). Traditionally, the IR literature has identified three broad logics that explain the creation of and adherence to institutional equilibria: the distribution of power, the pursuit of self-interest, and the normative appropriateness of the organisation. This tripartite distinction maps different expectations about what drives actor compliance and institutional change; such as, changes in power (for example, hegemonic decline), utility loss, or legitimacy loss. While we do not deny the importance of power and interests, we aim to contribute to recent literature that focuses on the normative appropriateness, or legitimacy, of an IO for understanding support and demands for institutional reforms.Footnote 8

Legitimacy is recognised as important to organisations because it helps to explain institutional choices and actor compliance even in a setting, such as the international system often is, in which coercive enforcement mechanisms are absent and the potential for utility losses are real.Footnote 9 In other words, legitimacy is the answer to Thomas Franck’s seminal question: ‘Why should rules, unsupported by an effective structure of coercion comparable to a national police force, nevertheless elicit so much compliance, even against perceived self-interest, on the part of sovereign states?’Footnote 10 The literature on organisational legitimacy is premised on the idea that institutions are selected and supported based on voluntary recognition of the organisation’s ‘right to rule’; legitimacy involves a moral obligation.Footnote 11 This idea is nicely captured in Richard Merelman’s definition of legitimacy as ‘the quality of “oughtness” that is perceived by the public to inhere in a political regime’.Footnote 12 According to this logic, institutional change should be motivated not only by changes in the distribution of power or utility losses but also by changes in organisational legitimacy.

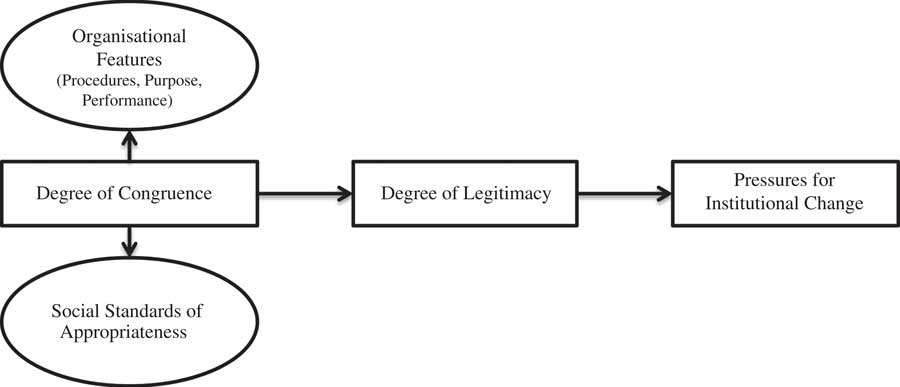

But how, specifically, does legitimacy lead to institutional change? Thus far the legitimacy literature in IR has focused on normative considerations, such as determining what the appropriate standards of legitimacy ought to be,Footnote 13 or on sociological considerations, such as empirically studying whether and on what grounds actors actually accept an IO as legitimate,Footnote 14 but has not explicitly developed a theory of legitimacy-driven institutional change.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, we argue that the existing legitimacy literature is based on an implicit model of change that we refer to as the ‘congruence model’ (Figure 1). This model starts from the premise that legitimacy is derived from congruence between an organisation’s features and the social values and norms held by actors in the organisation’s constituency. In a seminal text on legitimacy, David Beetham points towards the moral justifiability of political institutions and systems of power as a major determinant of legitimacy, which involves ‘an assessment of the degree of congruence, or lack of it, between a given system of power and the beliefs, values and expectations that provide its justification’.Footnote 16 Mark Suchman defines legitimacy as ‘a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions’.Footnote 17 In other words, legitimacy ‘reflects a congruence between the behaviors of the legitimated entity and the shared (or assumedly shared) beliefs of some social group’.Footnote 18 This is also a dominant view in IR where Ian Hurd, among others, sees legitimacy to be ‘a subjective quality, relational between actor and institution, and defined by the actor’s perception of the institution’.Footnote 19

Figure 1 The congruence model of organisational legitimacy.

Despite different analytical foci, the bulk of the literature follows Beetham in the view that organisational legitimacy depends on the congruence between an organisation’s features – specifically, its procedures, purpose, and performanceFootnote 20 – on the one hand, and the inter-subjectively shared norms and values held by relevant organisational stakeholders, on the other hand. If correspondence exists, organisational legitimacy results; as correspondence declines, so does organisational legitimacy. Because legitimacy enables organisations to function in the absence of threats of coercion and in the presence of potential utility losses, policymakers are sensitive to a decline in an organisation’s legitimacy, or legitimacy loss. Legitimacy loss leads to reduced support for the organisation and, consequently, pressure to engage in institutional changes that re-establish congruence. This, we argue, is the change mechanism implicit within the legitimacy literature.

According to this model, incongruence can arise in two ways: a change in the organisational features (procedures, purpose, performance) against a fixed set of underlying norms and values; or a change in the underlying standard of appropriateness against given organisational procedures, goals, and performance. In the first type of incongruence sequence, organisational features (perhaps ones created on efficiency grounds) violate underlying normative principles and thereby cause a decline in organisational legitimacy, which actors seek to mitigate through additional institutional change. This is a dynamic that has regularly driven institutional reform in the European Union.Footnote 21 The Lisbon Treaty, for example, was in part meant to reduce the Union’s legitimacy deficit that resulted from the incongruence of its procedures with underlying democratic norms, which had accumulated over prior waves of efficiency-driven institutional reform. Normative standards based on democratic principles had, arguably, not changed, but the IO’s procedures needed to be updated to match these standards. Another example is the expansion of the United Nations’ mandate to include the Responsibility to Protect. Much recent criticism sees this emergent rule as contravening key underlying principles, such as non-intervention and sovereign autonomy, and thus undermining organisational legitimacy and spurring institutional reform efforts.Footnote 22 Others have argued that as IOs expand their policy reach to ‘beyond the border’ issues that include individuals as the targets of regulation, they are under increased pressure to reform their procedures to align with standard norms of democratic participation.Footnote 23

The second type of incongruence occurs when changes in underlying standards of appropriateness no longer match dominant organisational features, leading to pressures for institutional change to conform to the new normative standards of appropriateness. Christian Reus-Smit argues, for example, that changes in basic institutional forms of international society reflect shifts in prevailing beliefs about the moral purpose of the state, the organising principle of sovereignty, and the norm of procedural justice.Footnote 24 Modern multilateralism, for example, was legitimised by a normative shift away from a social order based on natural law to a contractarian view of individual rights that understood the purpose of the state as a guarantor of those rights. More recently, Alexandru Grigorescu has shown how the rise of democratic norms and principles has created normative pressures for existing institutional designs – rules of participation, voting procedures, and transparency – to adapt in order to better align with those emergent norms.Footnote 25 Jonas Tallberg and colleagues have shown how IOs have opened up to civil society actors partly in response to changes in understandings of democratic participation norms.Footnote 26

The congruence model provides a useful starting point for thinking about organisational legitimacy and its relation to institutional change. It offers an analytically distinct and empirically plausible mechanism of change that is rooted in a variety of intellectual traditions and feeds off work in different social science disciplines. Yet, this implicit model of legitimacy as a driver of institutional change is underspecified, giving rise to three explanatory weaknesses. These weaknesses derive from the tendency to treat legitimacy as resulting from the straightforward assessment of congruence, by which a match or mismatch between institution and norms can be objectively ascertained.Footnote 27 In this view, changes in congruence are taken at face value as information that translates smoothly into judgments about organisational legitimacy. As we argue below, this account fails to take seriously the insight that attributions of legitimacy rest on perceptions; that is, that assessments of congruence lead to legitimacy judgments by way of cognitive processing. In short, the microfoundations that the model implies have yet to be developed. The costs of this failure are threefold.

The first weakness of the congruence model is that it has difficulty to account for endogenous dynamics of legitimacy judgments and legitimacy-driven institutional change. Change in the congruence model is exogenous: it expects organisational legitimacy to be constant as long as congruence between organisational features and underlying standards of appropriateness persists; conversely, it expects legitimacy judgments to change as soon as incongruence develops. It appears empirically plausible, however, that legitimacy may deepen or erode (that is, become more or less robust to external shocks) over time even in the presence of unchanged congruence. The German Grundgesetz, for example, is arguably more legitimate today than it was in the 1950s because over time Germans have more deeply internalised that it serves as an important safeguard of democratic norms and that it should be obeyed. As many observers suggest, Germans have been successfully ‘educated to democracy’.Footnote 28 For related reasons, an IO may be able to retain high levels of legitimacy even if its features become incongruent with underlying norms. One could argue, for example, that the United Nations has experienced a surprisingly small change in legitimacy given the degree of incongruence between its organisational features and underlying norms because over time it has built up a store of legitimacy. As Michael Barnett notes, ‘the UN is still the cathedral of the international community, the organizational repository of the community’s collective beliefs’.Footnote 29 In other words, congruence does not necessarily imply invariance in organisational legitimacy because legitimacy change may have endogenous sources, while incongruence may not immediately lead to legitimacy loss because legitimacy may exhibit path dependent qualities.

Second, the congruence model has difficulty accounting for spatial dynamics of legitimacy judgments and legitimacy-driven institutional change because it neglects legitimacy dynamics in other, related IOs. It assumes that all that matters for assessing the legitimacy of an organisation is to know the organisation’s procedures, purpose, or performance as well as the relevant standard of appropriateness. On this basis, individuals figure out a normative ideal point and compare the existing IO to it. If the two match up, the organisation is seen as legitimate; if the two do not match up, the organisation is seen as less or even illegitimate. This process of legitimacy judgment implies that IOs are conceived as atomistic entities whose legitimacy is determined in isolation from that of other, related organisations. Again, this appears empirically questionable. For example, we can discern waves of legitimacy crises that envelop groups of IOs. The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis that sparked a legitimacy crisis of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), for example, was the start of broader anti-globalisation protests felt across related global economic IOs and culminating in 2000, the ‘year of global protest’. The legitimacy crisis of the IMF was followed in 1999 by protests in Seattle at the World Trade Organization ministerial meeting. The collapse of the ministerial meeting, in turn, encouraged massive protests at subsequent World Bank-IMF meetings and the annual Asian Development Bank conference in the spring and autumn of 2000.Footnote 30 Similarly, after the end of the Cold War, regional organisations across diverse contexts have created parliamentary bodies as legitimation devices, suggesting cross-cutting influences.Footnote 31 These examples suggest that legitimacy challenges in one organisation might have repercussions for the legitimacy of other, related organisations. In other words, legitimacy dynamics are not independent across different organisations, but are in fact interdependent.

A third weakness of the congruence model is that it is indeterminate with respect to the specific institutional choices that are likely to result from a decline in legitimacy. While the congruence model broadly posits that legitimacy requires some overlap between societal norms and organisational features, it is largely indeterminate with respect to what levels of congruence lead to what levels of legitimacy and, therefore, with respect to what kinds of institutional change will be legitimacy enhancing. Congruence is multiply realisable; multiple institutional designs can be compatible with the same underlying norms. We would not expect, however, all variations of congruence to be equally legitimate. Many institutional designs, for instance, can be congruent with democratic norms and principles, but not all of these variants will necessarily enjoy legitimacy. Multilateralism, as Reus-Smit suggests, may be legitimate because it is congruent with underlying constitutive norms, but multilateralism comes in many institutional guises with varying levels of legitimacy – witness the variation in legitimacy across post-Second World War IOs despite their common commitment to multilateralism.Footnote 32 Moreover, scholars of normative legitimacy make proposals for appropriate organisational procedures, purposes, and performance that improve congruence with social norms, but not all of these proposals enjoy empirical legitimacy – recall the example of global parliamentary assemblies discussed earlier. Indeed, the empirical world seems to indicate that there are important threshold effects at work that determine when incongruence leads to legitimacy loss, but the model does not theorise why such threshold effects should matter or what determines them.

These empirical and analytical weaknesses indicate that the existing congruence model of legitimacy is insufficient for understanding the formation of legitimacy judgments and, consequently, pressures for institutional change. Some congruence between underlying norms and organisational features appears to be part of the very definition of legitimacy; however, variation in the level of congruence between an IO’s features and underlying social norms cannot on its own explain variation in legitimacy judgments. We argue that the evaluative assessment of congruence – that is, the meaning of congruence for legitimacy – is ultimately a perceptual judgment that requires examining its cognitive microfoundations. Cognitive factors are significant because they mediate how sensitive or tolerant actors are to varying degrees of incongruence. Examining cognitive microfoundations can help us to understand why, for instance, an incongruent but familiar IO may still be perceived as more legitimate than the congruence model alone would predict. In the next section we introduce a cognitive model of legitimacy that seeks to understand how cognitive processes affect legitimacy judgments and what implications this has for when imperfect congruence between organisational features and underlying norms will actually produce a push for institutional change.

II. The cognitive foundations of legitimacy

The dominant definition of legitimacy, as we have outlined it above, explicitly but only incidentally depends on actor perceptions. Recall that for Hurd, legitimacy is ‘defined by the actor’s perception of the institution’,Footnote 33 for Suchman legitimacy is ‘a generalized perception’,Footnote 34 and Jonathon Symons characterises legitimacy as ‘a “latent” psychological variable’.Footnote 35 Many important definitions of legitimacy, then, imply a cognitive process that has yet to be spelled out. While the literature has thus far emphasised the correspondence element of the definition, it has given less attention to the perceptual element of legitimacy. At the same time, while cognitive explanations have been used broadly to account for institutional or policy change,Footnote 36 their implications for perceptions of legitimacy have yet to be developed. We draw on the literature in cognitive psychology to develop microfoundations for the congruence model. Lessons from the cognitive literature are likely to help us better understand under what conditions (non-)changes to organisational features or underlying norms are likely to result in changes to legitimacy and when that is likely to lead to pressures for institutional change.

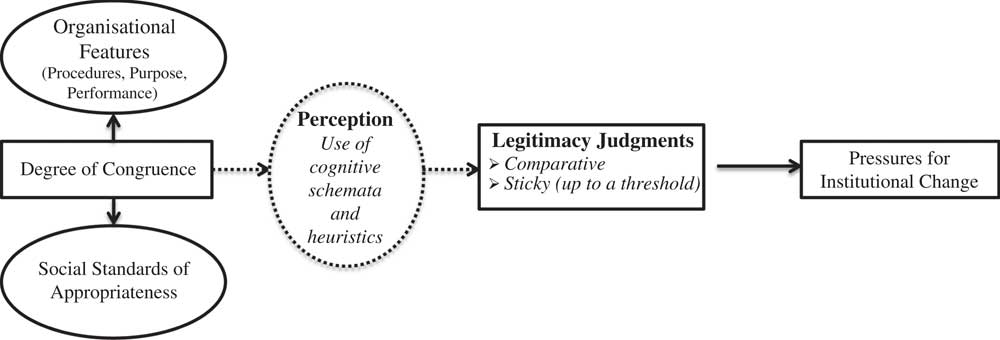

In this section, we discuss three core insights from the cognitive literature that should inform the way we think about legitimacy judgments: (1) judgments rely on cognitive schemata and heuristics that bias judgment; (2) they are comparative; and (3) they are sticky, up to a threshold. These lessons from cognitive decision-making theory provide empirically verified microfoundations for legitimacy judgments that lead to expectations different from the implicit or explicit implications of the standard congruence model. In Section III, we then scale up these lessons to develop distinctive hypotheses about aggregate patterns of organisational legitimacy and implications for institutional change. The expanded ‘cognitive congruence model’, which we now introduce, is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2 The cognitive model of organisational legitimacy.

Legitimacy judgments are rooted in cognitive schemata and heuristics

Because the bulk of the literature on legitimacy does not consider complex cognitive processes, most work implicitly expects actors to form legitimacy judgments in an ‘empty’ mind (tabula rasa): actors collect information on relevant organisational characteristics and accurately assess the congruence of characteristics and underlying standards of appropriate rule. The baseline assumption is that no other information apart from that derived from the organisation in question is used in judgment, and that congruence can be assessed unambiguously on the basis of this information without reliance on mental structures to give meaning to facts. Susan Fiske has termed this type of information processing ‘piecemeal processing’, which she characterises as relying ‘only on the information given and combines the available features without reference to an overall organizing structure’.Footnote 37

In cognitive psychology, in contrast, it has become widely accepted that actors are generally ‘cognitive misers’ and perception, judgment, and other basic cognitive tasks rely on schemata or mental concepts based on experiences that guide information collection, processing, and judgment.Footnote 38 In this approach, information is both incomplete and complex and therefore meaningful only through cognitive processes that mediate the perception and processing of external stimuli.Footnote 39 Unlike piecemeal processing, in schematic processing each ‘new person, event, or issue is treated as an instance of an already familiar category or schema’.Footnote 40 Schemata are ‘knowledge structures that represent objects or events and provide default assumptions about their characteristics, relationships, and entailments under conditions of incomplete information’.Footnote 41 As Richard Nisbet and Lee Ross put it, ‘Objects and events in the phenomenal world are almost never approached as if they were sui generis configurations but rather are assimilated into preexisting structures in the mind of the perceiver.’Footnote 42

This perspective suggests that we should approach legitimacy judgments not simply as the result of actually collected information but as that information filtered through existing experiences and ways of perceiving similar situations.Footnote 43 The informational requirements for legitimacy judgments are demanding, and the information needed to render them is likely to be ambiguous. For example, it is far from obvious what the appropriate standard for assessing an IO is and what, specifically, this standard requires of an IO in terms of procedures, purpose, or performance. From this perspective, legitimacy judgments are not so much active assessments of the congruence between organisational features and underlying norms in a single organisation based on externally provided ‘information’, but involve an assessment of congruence between the organisation in question and a mentally stored representation, or schema, of an IO. As Stefan Goetze and Berthold Rittberger reason, ‘From a cognitive perspective, the legitimacy of social objects and practices can be conceived of as corresponding to a state of congruence between the schemas governing a particular situation and the (perception of the) object or practice.’Footnote 44 Judgments about the legitimacy of an IO involve using schemata, based on prior experiences and mental models, to process different strands of information to make an inference about the right of that IO to rule.

Whereas research on schemata is mainly (though not exclusively) concerned with how the way we organise information and knowledge affects how we process information, the cognitive literature has also contributed to our understanding of how specific processing rules, known as heuristics, influence inferential judgment and decision-making.Footnote 45 Cognitive heuristics are ‘shortcuts that reduce complex problem solving to simpler judgmental operations’.Footnote 46 The field of heuristics is buttressed by large amounts of empirical, experiment-based research, whose central finding is that actors not only rely on specific cognitive tools to reach judgments, but that using such tools tends to bias judgments in identifiable and systematic ways. Many heuristics have been discovered, but among the most studied are the representativeness heuristic (making judgments based on similarity to the prototypes one has in mind), the availability heuristic (making judgments based on the information that is most memorable or familiar), and the anchoring heuristic (using the earliest information and experiences as a baseline for subsequent judgments). As we will discuss next, the use of these heuristics depends on comparative judgments and generally leads to the confirmation of prior beliefs rather than updating. As Paul DiMaggio emphasises, cognitive tools ‘promote efficiency at the expense of synoptic accuracy’.Footnote 47 In other words, ‘the price of cognitive economy in world politics is – as in other domains of life – susceptibility to error and bias’.Footnote 48 We should expect, then, legitimacy judgments to display biases that make them deviate systematically from the ‘objective’ or face value congruence between underlying norms and organisational features, which much existing research assumes.

Legitimacy judgments are comparative

Standard accounts of legitimacy implicitly expect actors to assess legitimacy against an ideal reference point; that is, does this IO conform to our normative standards of rightful rule? A cognitive approach, in contrast, expects legitimacy judgments to be based on a reference point that is available in the environment. Judgments are formed not on the basis of the optimal level of congruence between organisational features and norms, but rather on the degree of consistency with known models. Thus, whether a specific IO is more or less legitimate than another relevant IO is expected to be more informative of legitimacy judgments than comparison to an abstract ideal.

The comparative nature of legitimacy judgments is rooted in what Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman have called the representativeness heuristic.Footnote 49 People make sense of new information by evaluating it in relation to existing cognitive schemata, which tend to take the form of prototypes or exemplars. ‘Matching each new instance with instances stored in memory is then a major way human beings comprehend the world.’Footnote 50 We can expect beliefs about an IO’s right to rule to be formed on the basis of ‘departures’ in legitimacy from the legitimacy of a (ideal or real) reference organisation.Footnote 51 This argument is rooted in the experimentally verified idea that changes and differences are more accessible than absolute values. In Kahneman’s own words, ‘Perceptions are reference dependent: The perceived attributes of a focal stimulus reflect the contrast between the stimulus and a context of prior and concurrent stimuli.’Footnote 52

Cognitive psychologists debate whether such comparisons are based on prototypes, understood as an ideal-typical representation of an object, or exemplars, understood as a collection of existing models that have previously been encountered by an observer.Footnote 53 In any case, what matters for our purposes is that people judge the legitimacy of an IO in relation to a reference category. Prototypes and exemplars are chosen based both on being ‘highly accessible’,Footnote 54 that is, readily available to memory, and displaying superficial categorical similarities with the IO under judgment.Footnote 55 Similarity is generally assessed on the basis of semantic or relational similarities not necessarily relevant to the judgment at hand.Footnote 56 This might well explain the curious absence of parliamentary bodies in global organisations but also their pervasive existence in regional organisations. The European Union might be the prototypical exemplar of a regional organisation, and the fact that it features a parliamentary body might have come to pose a legitimacy challenge to regional organisations that do not have one. In contrast, the United Nations might be the prototype of global organisations, and the fact that it does not have a parliamentary body implies that the absence of parliamentary bodies in other global organisations has not induced similar legitimacy challenges. This kind of comparison has the potential to introduce bias because how similar one IO is to an important reference organisation may not be a good predictor of how congruent a specific IO’s procedures or performance are with underlying norms.

The comparative nature of legitimacy judgments implies that perceptions of legitimacy are not IO-specific and independent but are likely to co-vary across the institutional environment. This addresses two weaknesses of the existing congruence model. The first one is that it has difficulty accounting for spatial dynamics. A cognitive approach provides a plausible account of the interdependent nature of legitimacy judgments. One implication, for instance, is that when legitimacy judgments around the exemplar organisation change, then so too will judgments about other related IOs. This helps to explain why legitimacy crises often affect a range of organisations, even if the procedures, purpose, and performance of some remain unchanged. Second, this lesson also adds determinacy to the institutional changes that are likely to result from legitimacy dynamics. Whereas the requirement of congruence in the standard model does not ‘dictate’ specific institutional reforms in response to legitimacy loss, the cognitive model suggests that they will likely aim to mirror features in the exemplar IO. Conversely, conformity to typical IOs can help explain the persistence of legitimacy perceptions even if there is a growing incongruence between underlying norms and organisational features over time.

More broadly, comparative legitimacy grounds the general expectation that judgments of IO legitimacy within an organisational field display less variation, or more similarity, than an assessment of an individual IO’s congruence between underlying values and organisational features alone would lead us to expect. The standard congruence model should expect legitimacy judgments to vary rather widely across different IOs, reflecting specific ‘local’ conditions. However, if we conceive legitimacy judgments across a set of diverse IOs as interrelated, based on a limited set of prototypical exemplars, the full range of these judgments is likely to be narrower, fluctuating around the legitimacy of the reference IOs. In sum, the standard congruence model and the cognitive congruence model of legitimacy differ in the range of variation in legitimacy perceptions that they predict.

Legitimacy judgments are robust, up to a threshold

Standard accounts of how actors make judgments expect updating of prior beliefs in response to new information – regardless of whether those beliefs are normative or instrumental in nature. This is the baseline assumption of both Bayesian theories of inference as well as (fully) rational actor models. For legitimacy, this implies that actors are constantly monitoring the degree of congruence between underlying norms and an IO’s procedures, purpose, and performance. But experiments have shown that actors display a more conservative process of judgment formation, and that revision is slower and less responsive to changes. This empirical finding is explained in part by the types of heuristics actors use to make sense of information and experiences. Anchoring is one such heuristic that refers to actors’ tendency to give disproportionately more weight to prior beliefs, for example by making them a reference point of comparison, and less weight to new information. To the extent that new information is considered at all, it tends to be assimilated to fit existing beliefs.Footnote 57 People tend to be more sensitive to information that confirms existing schemata and tend to neglect, or easily discard, disconfirming information.Footnote 58 In this sense, the formation of judgment is theory- or belief- rather than data-driven.Footnote 59 The anchoring heuristic leads to a general tendency for selective attention to information and for actors to see what they expect to see based on prior beliefs and worldviews. In an empirical application of this idea, Robert Jervis shows that the failure to rethink and adjust pre-existing beliefs to incoming information is at the root of intelligence failure.Footnote 60 A core implication of cognitive models of perception, then, is that judgments are ‘sticky’ because early judgments tend to get reinforced and that updating based on new information is slow and unreliable.Footnote 61 As Richard Herrmann notes, ‘cognitive theories … typically feature continuity’.Footnote 62

Accordingly, we should expect perceptions of organisational legitimacy to be: (1) strongly conditioned by prior judgments about the IO; (2) resistant to updating; and therefore (3) also self-reinforcing. Existing beliefs about certain organisations in the environment will serve as the anchor that forms the baseline for whether an IO is more or less legitimate. The ‘stickiness’ of legitimacy judgments implies that incongruence between institutional features and underlying societal norms may persist over extended periods of time without a decline in legitimacy. Judgments of legitimacy are likely to display less frequent change, or updating, than an assessment of organisational congruence would lead us to expect. In other words, the standard model and the cognitive model of legitimacy differ in their predictions of frequency of change in legitimacy.

Although the cognitive approach implies a bias toward persistence and replication, it certainly does not conclude that beliefs and perceptions never change. In fact, the cognitive approach tells us something about the conditions under which we are likely to observe changes in perceptions of legitimacy and how these changes are likely to unfold. Gradual and isolated revelations of discrepancies between organisational features and underlying norms are likely to be integrated into and ‘rationalised’ by existing schemata, therefore slowing updating and forestalling an erosion of legitimacy.Footnote 63 However, a change in sticky legitimacy judgments becomes possible when actors are confronted with new, strong, salient, and rapidly arriving information that is disruptive of existing judgments and difficult to accommodate in existing schemata.Footnote 64 When new information triggers strong negative emotions or creates discomfiting feelings of cognitive inconsistency, actors are prompted to revisit their judgments in a more active and analytical fashion. Recent research in cognitive psychology argues that while reliance on heuristics or ‘quasi-rationality’ is the most common mode of cognitive processing, actors do have multiple cognitive approaches available to them depending on context. Kenneth Hammond’s cognitive continuum theory, for example, arrays different modes of cognitive processing along a continuum from intuition to rational analysis, with quasi-rationality positioned somewhere in between.Footnote 65 Susan Fiske and Shelley Taylor similarly argue that actors are not just cognitive misers but ‘motivated tacticians’ that can be motivated by new information to be more reflexive and engaged thinkers.Footnote 66 As a result, we should expect different – that is, more or less active – modes of cognitive processing to lead to different judgments; while heuristics lead to biases that may mask or make tolerable incongruence, more reflexive reasoning may increase actor sensitivity to incongruence.

According to cognition theory, movement towards more reflective modes of reasoning is stimulated through disruptive information that triggers negative emotions and cognitive conflict. Being confronted with an urgent crisis or starkly conflictual information, for example, can lead actors to engage in more active reflection. The idea here, following cognitive-consistency principles, is that change in deeply held perceptions is more likely when existing schemata are no longer serviceable and there is no other easily available path for accounting for and resolving contradictory evidence.Footnote 67 We would expect, for example, actors making legitimacy judgments about the IMF after the Asian Financial Crisis to engage in more reflexive rather than routine cognition as compared to just before the crisis, even though neither the IMF’s organisational features nor underlying values underwent change. In this context, emotion often ‘assist[s] the process of reasoning’.Footnote 68 Neuroscientific research suggests that humans use emotion-based evaluations of threat and novelty to direct attention and activate thinking, making reasoning and emotions intimately linked.Footnote 69 Negative emotions, in particular, appear to be influential in triggering a revision of legitimacy judgments because, as Fiske and Taylor explain, ‘negative affect is a bigger change from the baseline, more interrupting and distracting’.Footnote 70 George Marcus, Russell Neuman, and Michael MacKuen, summarising a large body of cognitive literature, similarly suggest that habitual judgment that bolsters stability is sustained by positive emotions, whereas active reasoning is sparked by negative emotions that cause despair and anxiety, stimulating actors to collect more information, to actively assess prior judgments, and to learn new attitudes and behaviours.Footnote 71 Consequently, we especially expect negative emotions to lead to a reassessment of IO legitimacy. Thus, when political activists manage to stir widespread anxiety about an IO, changes in legitimacy judgments should be more likely. The ‘Vote Leave’ campaign prior to the Brexit referendum might be a good example of this dynamic.

Cognitive conflict and discomfort can also be expected when actors operate in an environment with conflicting beliefs, or ‘multiple advocacy’, creating cognitive inconsistency that, in turn, promotes active reflection on existing beliefs.Footnote 72 Actors otherwise content to maintain pre-existing beliefs, may be compelled to revisit them when (perhaps long-existing) mismatches between underlying standards of appropriateness and organisational features become the subject of contestation. As Suchman notes, ‘An organization may diverge dramatically from societal norms yet retain legitimacy because the divergence goes unnoticed.’Footnote 73 Once that divergence becomes a topic of political debate with multiple, apparently irreconcilable, positions, actors will be more compelled to re-examine, and thus more likely to revise, their perceptions. For example, highly technical issues such as global financial regulation or taxation regimes remained largely unpoliticised before the 2008 economic crisis, allowing organisations in these areas to operate without experiencing low legitimacy perceptions even though the level of incongruence between their institutional features (for example, lack of transparency and representativeness) and underlying social norms (for example, equal representation and democratic accountability) was, arguably, quite high.Footnote 74 Thus, a given level of (in)congruence might be assessed differently depending on the extent to which it becomes subject to political debate.Footnote 75

III. Testable propositions of the cognitive approach to legitimacy

What are the testable implications of the cognitive model of legitimacy? We argue that the way actors cognitively process judgments about the match or mismatch between underlying norms and an IO’s features generates patterns of legitimacy beliefs that are distinct from those predicted by the standard congruence model. We develop these implications in the form of testable propositions that concern, respectively, judgment formation (propositions 1 and 2), judgment change (propositions 3 and 4), and IO responses (proposition 5). Before developing these propositions, we address how cognitive models that work at the level of individual actors can be used to understand aggregate judgments.

Aggregation: From individual to collective judgment

A defining characteristic of many cognitive schemata and patterns of individual judgment is that they are supra-individual; that is, they are not idiosyncratic to particular individuals but are shared by many. In this sense, cognition and perception are systematic, not idiosyncratic. Similar cognitive processes, and resulting biases, are likely to characterise legitimacy judgments of diverse individuals. Because of this, we can expect to find systematic patterns in judgments of IO legitimacy.Footnote 76 Conversely, patterns of organisational legitimacy, and legitimacy-driven institutional change, are likely to reflect, at least partly, the aggregate biases of individual cognitive assessments. These patterns, we suggest, differ systematically from those expected by the standard ‘objectivist’ congruence model of legitimacy.

Moreover, there is an important social element to cognitive schemata that undergird legitimacy judgments. While schemata can range from the universal to the idiosyncratic, many schemata are ‘culturally shared mental constructs’.Footnote 77 A cognitive approach to the study of IO legitimacy directs our attention not to individual psychology but to ‘sociomental’Footnote 78 phenomena that are shared by many, if not most, individuals, and that affect their legitimacy judgments in similar ways. Processes of social contagion and peer effects reinforce the collective nature of legitimacy judgments and can trigger rapid, wave-like change.Footnote 79 In the realm of IO legitimacy, ‘cognitive construction, in short, is social construction’.Footnote 80

Thus, legitimacy judgments of IOs are likely to display fairly coherent aggregate patterns not because the assessment of congruence between organisational features and underlying norms is easy and ‘objective’, but because any actor’s assessment of congruence between an IO and a typical exemplar is likely to be based on the same limited range of reference points. Categorisation theory shows that some members of a category are more central than others.Footnote 81 Even though no such research exists on international organisations, it appears plausible to assume that a representative sample of politically informed citizens around the world, when asked to give an example of a regional organisation, would much more often mention the European Union than, say, the Southern African Customs Union; similarly, it seems likely that the United Nations features as a prototype of a global organisation more often than, say, the International Whaling Commission. Overall, we argue that the propositions we develop should apply generally to both individual actors and collective legitimacy judgments.Footnote 82

Propositions

Because legitimacy judgments rely on pre-existing beliefs that tend to get replicated and reinforced over time (anchoring) and because of the importance of existing prototypes, we should expect legitimacy judgments to be more favourable towards well-established, familiar, and known organisations. Even a new organisation that conforms to existing models is likely to have a lower, or shallower, level of legitimacy than a well-established one. New organisations suffer from what organisational theorists call the ‘liability of newness’,Footnote 83 a condition that results from being unknown and, therefore, more difficult to evaluate because the formation of judgments and inferences relies on pre-existing beliefs and experiences that are unavailable.

Over time, the ‘liability of newness’ turns into a ‘legitimacy dividend’ that comes from the comprehensibility, familiarity, and reliability of beliefs formed over a long period. Continuity and legitimacy thus become mutually reinforcing. Frequent and intense interaction can make perceptions of legitimacy more robust over time. Longevity and familiarity are also likely to lower the threshold of congruence, so that an organisation may continue to ‘make sense’ even if the degree of congruence between its features and underlying norms begins to slip. Of course, even a long-lived and familiar IO is more likely to suffer legitimacy losses if it is no longer congruent with underlying norms, but age may compensate for such incongruence for extended periods of time.

The increasing difficulty of institutional change over time is also a key prediction of historical institutionalism. Scholars in this theoretical tradition tend to stress the rising costs of change as institutions create constituencies that have vested interests in maintaining the institutional environment. High set-up and sunk costs as well as learning and coordination effects lead to increasing returns to using the same institution.Footnote 84 A cognitive approach emphasises the stickiness of cognitive expectations once an institution has been put in place. In this vein, Amitav Acharya shows how policymakers’ ‘cognitive priors’ mitigated pressures for institutional change in Asian regional organisations for a long time, and eventually led to merely symbolic change that kept intact these cognitive priors.Footnote 85 The cognitive approach to legitimacy, then, leads to the following proposition:

P1 Longevity: a) Established IOs will enjoy a ‘legitimacy dividend’ and are likely to be perceived as more legitimate than new ones. b) As a result, institutional change to enhance congruence should become more difficult the older and more established an organisation is.

The next two propositions follow from the insight that legitimacy judgments are comparative. First, the representativeness and accessibility heuristics expect perceptions of legitimacy to be affected by the extent of an IO’s conformity to existing organisational prototypes and the ease of extrapolating from specific organisational experiences. Given the indeterminacy of the link between underlying standards of appropriateness and organisational features, actors are more likely to assess an organisation as legitimate when it conforms to other exemplars of organisations in the environment. As Michael Hannan and John Freeman have noted, ‘the simple prevalence of a form tends to give it legitimacy’.Footnote 86 This bias towards standardisation or conformity reflects actors’ conservatism and preference for continuity and familiarity. IOs can ‘protect their cognitive legitimacy by conforming to prevailing “heuristics”’.Footnote 87 Even though there are different ways to translate the principle of democracy into specific institutional features in nation states, there is a surprising degree of institutional commonality among democratic states around the world. Similarly, at the international level, some authors have argued that the empowerment of the European Parliament has become the ‘habitual’ response to allegations of a democratic deficit in the European Union over time. Whereas initially different institutional options were carefully considered in the face of a legitimacy challenge, over time strengthening the European Parliament became the default response.Footnote 88 Now there is evidence to suggest that the creation of parliamentary assemblies is becoming the ‘standard’ response to allegations of a democratic deficit in other regional organisations as well.Footnote 89 Similarly, recent findings suggest that there is a significant degree of convergence in the way that IOs open up to non-state actors, suggesting that institutional templates play an important role in how IOs confront legitimacy challenges.Footnote 90 These considerations lead to our second proposition:

P2 Conformity : a) An IO that conforms to existing organisational prototypes is more likely to be perceived as legitimate than one that does not. b) As a result, legitimacy crises are likely to lead to the adoption of ‘familiar’ institutional designs.

Further, given both that legitimacy judgments are comparative and that legitimate organisations tend to be isomorphic (P2 conformity), we expect both positive and negative legitimacy perceptions of referent, or focal, IOs to affect the legitimacy perceptions of related organisations in the environment. This is perhaps most apparent for legitimacy crises. A legitimacy crisis occurs ‘when the level of social recognition that its identity, interests, practices, norms, or procedures are rightful declines to the point where the actor or institution must either adapt (by reconstituting the social bases of its legitimacy, or by investing more heavily in material practices of coercion or bribery) or face disempowerment’.Footnote 91 Such crises of legitimacy often are not restricted to a single IO, but are likely to be contagious across a set of organisations. The comparative nature of legitimacy means that an actor’s perception of organisational legitimacy is generally likely to decline when the referent IO has slipped into crisis. We might expect, for example, that many regional organisations around the world will have trouble retaining previous legitimacy levels in view of the apparent legitimacy crisis currently affecting the European Union. Similarly, a legitimacy crisis of the United Nations Security Council is likely to affect perceptions of other United Nations organisational emanations. Global economic organisations, as noted above, have been susceptible to contagious legitimacy loss, even if the crisis was localised to one IO, such as the IMF in the Asian Financial Crisis. At the same time, organisations that are perceived as legitimate can lend that legitimacy to other organisations, resulting in a wave of positive legitimacy.Footnote 92 Thus, our third proposition says:

P3 Contagion: a) A change in the legitimacy of an important referent IO in an organisational field will affect the legitimacy of other organisations in the field. b) As a result, we are likely to see waves of legitimacy-driven institutional change.

Despite the cognitive approach’s emphasis on the stickiness of perceptions, it also helps us to think about the conditions under which we are likely to see a change in legitimacy judgments and, conversely, what conditions can promote stable legitimacy beliefs even in the face of some degree of ‘objective’ incongruence. Research on cognition has shown that beliefs are most susceptible to revision and updating when information deviating from prior beliefs is strong, salient, and arrives rapidly.Footnote 93 For similar reasons, levels of active reflection may be related to the policy-cycle, with founding moments or moments requiring active decision-making eliciting more debate and active thinking. Hurd, for example, highlights the strong consequences deliberation at the 1945 San Francisco Conference had for establishing UN legitimacy.Footnote 94

More generally, our discussion thus far leads us to hypothesise that active reflection should be more likely under conditions of contestation over an IO. Contestation can arise when an organisation loses (or has no) taken-for-grantedness; that is, when new information elicits strong negative emotions or creates new tasks or creates cognitive inconsistency that needs to be resolved.Footnote 95 These are situations in which the ‘failure’ of existing beliefs is exposed and requires resolution. During moments of politicisation and contestation, actors otherwise content to maintain pre-existing beliefs and to not actively deliberate over judgments may be compelled to revisit their beliefs in light of conflicting beliefs or multiple advocacy.Footnote 96 Contestation may be motivated by incongruence, but it need not be. Incongruence between norms and organisational features can exist for extended periods of time before becoming subject to political debate; thus, we expect politicisation to have an impact on legitimacy independently of levels of incongruence.

Consider, for example, that for the first 25 years of its history, the European Community’s legitimacy was based on a permissive consensus that allowed elites to advance European integration without much public scrutiny. With the Maastricht Treaty, this permissive consensus gave way to the politicisation of the European Union and public political contestation over its legitimacy.Footnote 97 Even though the incongruence between underlying values and organisational features has remained constant or even improved due to subsequent reforms aimed at addressing legitimacy deficits, popular judgment of the EU’s legitimacy has deteriorated.Footnote 98 The implication is that a given degree of incongruence might be perceived as either legitimate or illegitimate depending on the level of contestation within the relevant constituency, which itself might change over time or over different phases in the policy cycle, yielding proposition four:

P4 Politicisation: a) Contestation can prompt active judgment updating. b) As a result, judgments about legitimacy are more likely to change when an organisation is highly politicised.

Finally, understanding when legitimacy judgments are likely to change yields expectations about the strategies that IOs and their leaders are likely to pursue to forestall or mitigate legitimacy losses. The literature has focused thus far on institutional solutions to incongruence: institutional reforms aimed at realigning organisational features and socially-held values. But the cognitive model highlights that an IO should also be aware of how actors perceive it and on what basis those perceptions are likely to rest. When an IO cannot maintain or repair its legitimacy by actively bringing its procedures, purposes, and performance into alignment with norms and expectations, an IO can attempt to influence how actors perceive it by presenting arguments, or legitimation narratives,Footnote 99 that (1) cash in on the longevity dividend; that (2) emphasise the prototypical nature of the organisation (for example, we have all the features you expect us to have); that (3) emphasise the conformity to other specific organisations that do not suffer from a legitimacy deficit; and/or that 4) emphasise those organisational features that are congruent with underlying norms while downplaying the importance of those that are not. As Roy Suddaby and Royston Greenwood note, ‘Rhetorical strategies are the deliberate use of persuasive language to legitimate or resist an innovation by constructing congruence or incongruence among attributes of the innovation, dominant institutional logics, and broader templates of institutional change.’Footnote 100

The United Nations has engaged in several of these legitimation strategies. In the context of the organisation’s 70th anniversary celebrations, for example, the United Nations launched an advertising campaign called ‘70 Ways the UN Makes a Difference’.Footnote 101 The campaign – rolled out under the theme ‘Strong UN. Better World’ – aims to increase support for the organisation and its work by drawing on its status as the premier IO. In a quote featured prominently on the United Nations’ website, then Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon reminds his audience that, ‘In many respects, the world is shifting beneath our feet. Yet the Charter remains a firm foundation for shared progress.’Footnote 102 This is an argument that directly appeals to the United Nations’ longevity and prototypical status as sources of its legitimacy. Moreover, the United Nations’ marketing campaign emphasises its mission – rather than its procedures or actual effectiveness – of improving life for all people globally, thus underscoring the congruence between its purpose and underlying social norms. Indeed, distinct organisational features can align differently with underlying norms, providing an opportunity for legitimacy arbitrage. Procedural legitimacy, for example, might be perceived as worse when compared to the purpose or performance of an organisation.Footnote 103 Variation in congruence across features provides IOs with an opportunity to pursue legitimation narratives that strategically seek to shift stakeholder attention to the more congruent dimension.Footnote 104 The purpose of strategic legitimation narratives is to prevent ‘objective’ incongruences from resulting in legitimacy loss by engaging with heuristics that are likely to enhance tolerance for or mitigate uneasiness with incongruence. These considerations yield our fifth proposition:

P5 Legitimation Narratives: a) IOs are likely to pursue legitimation narratives that invoke heuristic devices to promote cognitive consistency. b) As a result, even IOs with limited ‘objective’ legitimacy might survive over extended periods of time.

These five propositions outline the expectations that a cognitive approach generates for the conditions under which legitimacy judgments are likely to change, when they are likely to lead to institutional change, and what strategies we can expect organisations to pursue in response. We base them on the conceptual model we generated from cognitive insights into perception and decision-making. Although the propositions outline plausible patterns that can help us make sense of legitimacy judgments, we leave an empirical test of the propositions (and a discussion of related methodological challenges) for future work.

Conclusions

An increasing number of studies focus on empirically measuring the sources of legitimacy and the degree to which relevant stakeholders actually perceive an IO as legitimate. But relatively little attention has been paid to the mechanisms by which legitimacy judgments originate and change. Standard accounts of legitimacy are based on an implicit model that sees legitimacy as the result of congruence between institutional features (such as procedures, purpose, and performance) and societally held norms. However, as we have outlined, this model cannot account for some likely patterns of variation in legitimacy and institutional change. We argue that thinking about the role of cognitive factors in the formation of legitimacy judgments can make an important contribution to understanding the dynamics of legitimacy.

First, considering the cognitive factors involved in perceptions of legitimacy can help us to understand how legitimacy judgments are formed and under which conditions they are likely to change. This, in turn, gives us better leverage in explaining the set of cases in which organisational features and societal norms remain constant but legitimacy perceptions change, and cases in which organisational features and societal norms are incongruent but legitimacy perceptions remain unchanged. Second, these insights help us to understand when legitimacy is likely to lead to institutional change. Pressures for institutional change do not simply arise when there is an ‘objective’ incongruence between an IO’s features and socially-held norms. Instead, pressures for institutional change will depend on the strength of heuristic biases, the legitimacy perceptions of other IOs in the environment, and the ability of an IO to create a legitimation narrative that mitigates the cognitive dissonance that arises from perceiving an ‘objectively’ illegitimate (that is, incongruent) IO as legitimate.

Finally, considering the cognitive processes involved in legitimacy judgments has important practical applications. In particular, it reveals the possibility of manipulating perceptions in order to shape legitimacy judgments and indicates what types of legitimation strategies are likely to be successful (namely, those that rely on anchoring, availability, and representativeness). Legitimation strategies, as with all signalling strategies, need to speak to the psychology of perception. This is an important insight given that many observers diagnose a widespread delegitimation of international authority.Footnote 105 As the success of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump indicate, countering perceptions of illegitimacy simply with an appeal to ‘true facts’ alone is insufficient. ‘Facts’ neither speak for themselves nor do they motivate the updating of beliefs as long as they can be comfortably integrated into existing schemata, meaning they do not cause cognitive dissonance or negative emotions. Countering the current legitimacy crisis of global governance, therefore, will require taking into account the psychology of judgment, the cognitive nature of decision-making, and the role of emotions in processing information.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the workshop ‘Designing Legitimacy in International Organizations’, European University Institute, 8 June 2016, and the International Studies Association Annual Conference in Baltimore, 22 February 2017. We thank the participants at these events, and especially Klaus Dingwerth, Nadav Kedem, Friedrich Kratochwil, Eva Lövbrand, Vincent Pouliot, Jonas Tallberg, and Jennifer Welsh, as well as the reviewers for very useful comments. We are grateful to the European University Institute for sponsoring the above workshop and for hosting us as Max Weber and Jean Monnet Fellows in 2015/16. The EUI provided an ideal atmosphere in which the fruitful collaboration that underpins this article could develop. Tobias Lenz also acknowledges support from the European Research Council Advanced Grant #249543 ‘Causes and Consequences of Multilevel Governance’, and a Daimler-and-Benz Foundation postdoctoral scholarship.