1. Introduction

State agricultural marketing programs are state-supported initiatives designed to showcase and encourage the consumption of state-grown foods. Initially established during the Great Depression to support farmers’ revenues during economic difficulties (Patterson, Reference Patterson2006), these programs have evolved to include broader purposes, including advancing a common state brand that can be collectively supported by growers, consumers, and state agencies, while encouraging healthier food choices (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Jung, Im and Severt2020). These initiatives also align closely with the local food movement as they are intended to help consumers identify locally sourced products and promote the benefits of consuming products grown near the point of purchase (Naasz et al., Reference Naasz, Jablonski and Thilmany2018). Nearly every state in the US has now implemented some form of agricultural marketing program (Onken and Bernard, Reference Onken and Bernard2010), though their effectiveness varies depending on the products promoted, market segments targeted, and program administration (Patterson, Reference Patterson2006).

Previous studies have suggested that state agricultural marketing programs are most effective at protecting state-grown products against imports from competing states or foreign countries (Khachatryan et al., Reference Khachatryan, Rihn, Campbell, Behe and Hall2018; Ruth and Rumble, Reference Ruth and Rumble2016). However, their collective effectiveness becomes limited when multiple states establish equivalent programs. This situation results in a zero-sum game where gains in one state are offset by losses in another (Neill et al., Reference Neill, Holcomb and Lusk2020; Patterson, Reference Patterson2006). Still, even if most state branding programs’ impact remains confined within their borders, some states have successfully promoted their products nationally by leveraging unique competitive advantages. For example, Idaho has capitalized on its volcanic soil, year-round sunshine, and irrigation resources to promote its potatoes through the “Grown in Idaho” logo (Guenthner, Reference Guenthner2012), while Washington has successfully marketed its apples by making use of its quality orchard industry and capitalized well-developed infrastructure (Jarosz and Qazi, Reference Jarosz and Qazi2000).

These examples suggest that some state marketing programs can effectively promote produce beyond their borders. However, research evaluating the overall effectiveness of these programs in supporting out-of-state promotional activities remains limited. To fill this gap, we sought to determine how the “Fresh From Florida” program affects consumers’ preferences in locations other than Florida itself. For this purpose, we developed and administered an online choice experiment for which tomatoes were used as a representative product. We elicited consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP) for “Fresh From Florida” labeled tomatoes in three distinct regions: the Northeastern region of the US, the Eastern territories and provinces of Canada, and the state of Florida itself. We then compared the WTP for “Fresh From Florida” labeled tomatoes among out-of-state consumers with that of Florida consumers.

Florida’s state branding program represents an interesting case to address those questions as the state agriculture benefits from a unique growing environment that makes it one of the main exporters of produce in the US. Indeed, Florida’s climate is characterized by subtropical conditions, which are ideal for growing produce during the winter months. This also corresponds to a period of the year during which production in other states is limited due to the colder weather. In addition, this subtropical climate provides producers with a relatively long growing season, which, except for a few months during the summer, allows them to remain active nearly year-round (Chanda et al., Reference Chanda, Bhat, Shetty and Jayachandran2021; Lucier et al., Reference Lucier, Pollack, Ali and Perez2006).

Given the significance of agriculture for its economy, Florida established in 1990 its own state-branding initiative called “Fresh From Florida.” This program is currently administered by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS). Like other state-branding initiatives, the program’s principal objective is to promote the consumption of commodities grown in Florida. The main promotional instrument at its disposal is the “Fresh From Florida” identifier, which is a logo designed to help consumers identify foods produced under this program.

According to FDACS, as reported by Loria (Reference Loria2020), the “Fresh From Florida” program has achieved significant reach and awareness. With a customer base surpassing 50 million consumers, the program’s influence extends well beyond the population of Florida and the state’s borders. Furthermore, within Florida, the program’s awareness rate is now at 86 percent, demonstrating its success in reaching out to the primary market it is designed to serve. Still according to FDACS, nine out of ten Florida shoppers declare that they are more likely to purchase a food product if it is labeled with the “Fresh From Florida” logo. Finally, 74 percent of consumers are willing to pay a premium for foods produced under the programs, demonstrating the trust and value that consumers place in the program.

Despite the success of the “Fresh From Florida” program, Florida’s agriculture faces significant economic challenges, particularly in its competition with Mexico following NAFTA’s implementation in 1994, which has led to a substantial influx of Mexican produce that peaks during Florida’s winter growing season (Zahniser et al., Reference Zahniser, Angadjivand, Hertz, Kuberka and Santos2015). This is especially problematic for Florida’s tomato industry, which accounts for 90% of US fresh winter tomato production and is the state’s second-largest agricultural crop after citrus (Chanda et al., Reference Chanda, Bhat, Shetty and Jayachandran2021). Since 2000, Florida’s tomato production has declined by over half, while Mexican imports have doubled (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Biswas and Wu2018). The factors commonly cited to explain this unfavorable trade environment are Mexican government subsidies, lower labor costs, and favorable exchange rates (Li et al., Reference Li, Wu, Guan and Luo2022). As a result, Florida’s produce industry must now compete with cheaper imports in its traditional export markets.

To address these challenges and enhance the visibility of Florida-grown products, the “Fresh From Florida” program has sought to develop collaborative initiatives with a number of national and foreign retailers. Over the years, the program has built promotional partnerships with more than 100 retail partners in 26 countries (Robbins, Reference Robbins2023). Since Canada is the leading destination for Florida’s fresh fruits and vegetables (FDACS, 2023), FDACS has also initiated collaborations with more than a thousand stores in three Canadian provinces to showcase the various food products it promotes (FDACS, 2015). These efforts demonstrate the program’s commitment to strengthening its market presence. However, assessing the program’s impact and reach in both domestic and international markets remains critical.

2. Literature review

The majority of the contributions regarding the impact of state marketing programs show that consumers are generally willing to pay a premium for food produced under state agricultural marketing programs (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Bernard and Pesek2013; Fonner and Sylvia, Reference Fonner and Sylvia2015; Grashuis and Su, Reference Grashuis and Su2023; Loureiro and Hine, Reference Loureiro and Hine2002; Merritt et al., Reference Merritt, Delong, Griffith and Jensen2018; Nganje et al., Reference Nganje, Hughner and Lee2011; Onken et al., Reference Onken, Bernard and Pesek2011). The factors that have been advanced to explain the willingness to pay a premium for state-branded food are varied and include considerations such as the nature of the product under study, its perceived freshness, other quality attributes, brand equity, and consumer willingness to support the local economy (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Bosworth, Bailey and Curtis2014; Loureiro and Hine, Reference Loureiro and Hine2002; Nganje et al., Reference Nganje, Hughner and Lee2011; Onken and Bernard, Reference Onken and Bernard2010).

However, research on state branding programs’ effectiveness in influencing out-of-state consumers, particularly those in distant regions, remains limited in the literature. Patterson (Reference Patterson2006) recognizes that while these programs can extend across state lines, their success largely depends on their ability to differentiate products from those of other states. However, this strategy has limitations in terms of collective impact, as competition between state programs can create a “beggar-thy-neighbor” effect where gains in one state come at the expense of losses in another.

Neill et al. (Reference Neill, Holcomb and Lusk2020) further investigated this beggar-thy-neighbor effect by examining how states’ branding programs spill over to other states. With a choice experiment for state-branded milk across eight contiguous states, they found that consumers show significant preference variations for both their own state’s brands and those from other states. When presented with both options, consumers sometimes choose products from other states, which led the authors to suggest cooperative or regional branding efforts as a potential solution to mitigate competitive effects.

Finally, Fife et al. (Reference Fife, Secor and Campbell2024) investigated how competition between state brands affects consumers’ perceptions of what constitutes “local” food. Their research revealed that these perceptions are relative and influenced by exposure to state-branded foods. Specifically, consumers who have not been exposed to their home state’s brands tend to have a more confined view of what counts as local, but when presented with brands from other states, their definition of “local” tends to expand geographically.

These contributions show that state branding programs can positively influence consumer behavior in neighboring states, though their overall impact is limited by interstate competition. However, Florida presents a unique case that differs from previous studies, which focused primarily on contiguous states. Indeed, Florida’s agricultural exports travel significantly greater distances, particularly to the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada. In this case, the influence of proximity may not have much of an effect on consumers located in geographically distant regions.

Nonetheless, state labels may still influence purchasing behavior even if consumers are located in geographically distant markets. On the one hand, state labels may be interpreted as a signal of quality, especially in the case of Florida’s state program, where the purported freshness of the product is clearly communicated with the label. On the other hand, state-branded products may be perceived as a threat to the local economy. Indeed, these labels usually feature the name of the state where the product was grown and, therefore, clearly indicate that it has been imported from somewhere else. In addition, with the imported nature of the product emphasized by the state label, consumers may question the quality and freshness of produce that may have traveled long distances. Therefore, consumers located in geographically distant markets may either respond positively or negatively to state labels such as the “Fresh From Florida” program.

However, we may still hypothesize that factors such as consumers’ previous exposure to the promotional activities of the program or consumers’ affinity towards the state of Florida may play a role in influencing purchasing behavior. Consumers who remember being exposed to the “Fresh From Florida” logo in the past or have positive associations with the state may be more responsive to the branding efforts and more likely to view Florida-grown products favorably. Conversely, consumers with an uncertain recall of the logo or those expressing a negative view of Florida may be less inclined to buy Florida-grown products.

We, therefore, establish three research objectives. First, we test whether state labels influence purchasing behavior in geographically distant markets. Second, we examine how consumers’ prior exposure to promotional activities, measured through logo recall, affects their response. Third, we investigate whether consumers’ opinions toward Florida moderate the effect of logo recall on purchasing decisions.

3. Methodology

We used a choice experiment to address the questions mentioned in the previous section. The choice experiment approach allows researchers to quantify the utility that consumers derive from the different attributes of a product or service. In practice, the participants recruited for the experiment are presented with different alternatives to the product or service in question, which is, in our case, are tomatoes, and are asked to choose the alternative they prefer. Each of these alternatives consists of a different attribute profile, including varying prices, so respondents must make realistic tradeoffs when choosing their preferred alternatives. Respondents are usually asked to make repeated choices, each with a different alternative profile. A statistical model is then applied to the participants’ selections to determine the utility derived from the different attributes and the corresponding WTP.

Choice experiments are often the preferred method for the type of study like ours. First, by recreating credible purchasing scenarios, choice experiments compel respondents to make the same types of trade-offs as they would during real shopping situations, thereby lending credibility to the study setting. Moreover, choice experiments provide researchers with flexibility in the construction of the design. They permit the inclusion of realistic, yet hypothetical, attributes, thus enabling researchers to customize the experiment to their specific research questions and hypotheses (Hensher et al., Reference Hensher, Rose and Greene2005). In our case, we recreated purchasing scenarios involving the different attributes of tomatoes, including the “Fresh From Florida” logo, similar to what respondents would find when shopping online or at a supermarket.

3.1. Choice experiment theory

The utility theory that serves as the foundation of choice experiments is based on Lancaster’s (Reference Lancaster1966) proposition that consumers do not derive utility from the consumption of a good as a whole but rather derive utility from each of the distinct characteristics or attributes that make up the good in question. If we assume that utility is additive, consumer preferences for a good or service can be expressed as a random utility model, as shown in equation (1):

$${\rm U}_{{\rm j}}=\sum _{{\rm m}=1}^{{\rm M}}{\unicode{x03B2}} _{m}{\rm x}_{{\rm mj}}+{\unicode{x03B2}} _{{\rm p}}{\rm P}_{{\rm j}}+{\rm\varepsilon} _{{\rm j}}$$

$${\rm U}_{{\rm j}}=\sum _{{\rm m}=1}^{{\rm M}}{\unicode{x03B2}} _{m}{\rm x}_{{\rm mj}}+{\unicode{x03B2}} _{{\rm p}}{\rm P}_{{\rm j}}+{\rm\varepsilon} _{{\rm j}}$$

where M is the number of attributes under consideration, xmj denotes the value or level of attribute m for alternative j, and β m is the utility conferred to attribute m. The variable P j is refers to the price of alternative j. Accordingly, β p representing the marginal utility of income which is assumed to be constant. An error term, ε j , is also included in the equation to represent unobserved random influences contributing to the utility. This error term is assumed to be independently and identically distributed and to follow a type I extreme value distribution.

With those assumptions, the probability that alternative j is selected can be expressed as a function of all the other alternatives K in the choice set:

$${\rm P}_{{\rm j}}={\exp \left[{\bf U}_{{\bf j}}\right] \over \sum _{{\rm k}=1}^{{\rm K}}\exp \left[{\bf U}_{{\bf k}}\right]}$$

$${\rm P}_{{\rm j}}={\exp \left[{\bf U}_{{\bf j}}\right] \over \sum _{{\rm k}=1}^{{\rm K}}\exp \left[{\bf U}_{{\bf k}}\right]}$$

The parameters in equation (2) can then be estimated using maximum likelihood estimation. Furthermore, the willingness to substitute one attribute for another can be determined by calculating the ratio of any two utility parameters in (1). The marginal effect of an attribute on WTP for the product attribute m can be estimated by taking the ratio of utility parameters βim over the price parameter βiP.

However, the conditional logit model is based on assumptions of independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA), which may not always hold. The nested logit model relaxes this assumption by allowing for correlation among alternatives within each nest. In this case, the probability of choosing alternative j in nest B becomes:

where PB is the probability of choosing nest B and Pj|B is the probability of choosing alternative j conditional on choosing nest B.

The mixed logit model allows the utility parameters to vary randomly across individuals and, therefore, can account for preference heterogeneity. In this case, the utility parameters in Equation 1 can take the form of a random distribution. The probability of individual i choosing alternative j can then be calculated by integrating the conditional probability over all possible values of β:

$${\rm P}_{{\rm ij}}=\int {\exp \left[{\bf U}_{{\bf ij}}\right] \over \sum _{{\rm k}=1}^{{\rm K}}\exp \left[{\bf Ui}_{{\bf k}}\right]}f\left(\beta \right)d\beta$$

$${\rm P}_{{\rm ij}}=\int {\exp \left[{\bf U}_{{\bf ij}}\right] \over \sum _{{\rm k}=1}^{{\rm K}}\exp \left[{\bf Ui}_{{\bf k}}\right]}f\left(\beta \right)d\beta$$

3.2. Choice experiment design

One of the advantages of choice experiments is that respondents can be presented with product alternatives made of multiple attributes, as in real shopping situations. This helps to mitigate the biases that may arise when respondents are drawn to focus their attention on only one or a few attributes. In our case, we selected a set of attributes commonly found on the packaging of tomatoes sold in grocery stores. As shown in Table 1, these attributes include product origin and branding, the official USDA organic logo, the Non-GMO Project Verified logo, a digital indicator (i.e., a QR code), and the price of the product. This design offers the advantage of recreating a shopping experience where participants evaluate tomatoes based on attributes that are familiar to them. Furthermore, including these attributes allows us to compare the WTP for the “Fresh From Florida” logo with the WTP of other attributes, such as organic or non-GMO status, and hence use them as benchmarks.

Table 1. Attributes for the choice experiment

We chose four levels for the product origin and state program branding: no indication for US consumers (or “Product of USA” for Canadian consumers), the “Fresh From Florida” logo, the “California Grown” logo, and “Product of Mexico.” As explained previously, Mexico is a significant competitor for both Florida and California, so we also included the attribute “Product of Mexico.” Furthermore, the “California Grown” logo was meant to be used as a reference point to be compared with the utility consumers derived from “Fresh From Florida.”

We also thought that the inclusion of the “California Grown” attribute would be relevant to our study since California and Florida are intermittent competitors in the production of fresh tomatoes. Each state accounts for a roughly equal share of the nation’s production of fresh tomatoes. However, California’s fresh tomatoes are produced year-round, except during the winter months, while Florida’s tomato production takes place from October to June (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Biswas and Wu2018).

Whether both states’ tomato options are simultaneously available in the market or only one is present at a time should not substantively impact the measurement of the premium associated with the “Fresh From Florida” label or the rest of the attributes. This is because the utility parameters reflect the value that consumers place on the different tomato attributes with respect to the baseline option, which is a generic US tomato. The inclusion of the “California Grown label” provides a point of comparison, but it does not alter how consumers value any of the other attributes relative to the baseline US-grown option. Moreover, the hypothetical nature of our choice experiment allows consumers to express their preferences for different attributes regardless of actual market availability. Nonetheless, there is still a period in the fall and spring during which the production of tomatoes in California and Florida briefly overlaps (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Biswas and Wu2018).

It is important to note that for Canadian respondents, the baseline for the “product origin” attribute refers to tomatoes imported from the US. While not including a Canadian tomato does not allow us to fully account for the role that domestic tomatoes play in the Canadian market, we chose this approach for several reasons. One is that our study is meant to assess whether the presence of the “Fresh from Florida” logo adds any value to Florida-grown produce over other US-imported varieties. Hence, our design is primarily intended to assess whether Canadian consumer preferences for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes differ from other unlabeled US tomatoes. Another reason for excluding the Canadian-grown attribute is that our study sought to replicate the peak export season for Florida tomatoes, a period during which Canadian-grown tomatoes are limited due to cold temperatures and low light conditions, and therefore, imported varieties play a more significant role in the Canadian tomato market. However, the presence or absence of a Canadian-grown option should not substantively affect our estimated parameters, as these measure consumers’ preferences relative to the baseline of a generic tomato imported from the US, independent of domestic availability. These relative valuations capture how attributes like the “Fresh From Florida” label and other characteristics of imported US tomatoes differ from unlabeled US imported tomatoes, which remains valid regardless of other potential options in the market.

Regarding the rest of the attributes, the organic status attribute indicates whether the tomatoes were certified as USDA Organic or were conventionally grown; the GMO status attribute conveys whether the tomatoes were certified by the Non-GM Project Verified organization; the digital of a QR code to reflect the present use of this technology.Footnote 1 Finally, we used three levels for the price attribute: $1.49, $2.39, and $3.29 per pound, which represented a plausible price range of prices when we conducted the survey.Footnote 2

With one attribute having four levels, three attributes having two levels, and one attribute having 3 levels, a total of 96 (4 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3) potential alternatives could be constructed. To facilitate the creation of the choice experiment pictures (see Fig 1) and minimize respondents’ fatigue and information overload, we sought to create a design of 48 alternatives that could be allocated to 24 choice sets and further divided into 3 blocks. With these parameters, we use a SAS macro to generate a design that maximizes efficiency in terms of orthogonality and balance (Kuhfeld, Reference Kuhfeld2003). We then used the functionalities of our survey platform to randomly assign our respondents to one of these three blocks. Hence, each respondent was presented with 8 choice sets of two paired alternatives.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Sample choice set from the choice experiment.

Figure 1 shows an example of a choice set that was presented to respondents. The pictures represent the product alternatives that were constructed when designing the choice experiment. They were designed to simulate a typical shopping experience, either in-store or online, by displaying various product attributes, such as prices, state labels, organic and non-GMO certifications, and QR codes, in a layout intended to be both intuitive and familiar.

To ensure consistency, each attribute was displayed in exactly the same location across all alternatives in each choice set. For example, prices were always displayed in the upper-right corner of each product image, while country-of-origin labels consistently appeared in the bottom right. Similarly, the organic and non-GMO status indicators were always positioned on the bottom left side of the images, and the QR code was always positioned on the upper left side of the images. Furthermore, the placement and size of attributes within a picture may impact decision-making, so we avoided putting any of the attributes near the center of the picture and ensured that all the attributes were the same size.

Before participating in the choice experiment, respondents were presented with a “cheap talk” script intended to encourage them to provide truthful responses and mitigate any potential hypothetical bias, i.e., the tendency of respondents to overstate their WTP for a good or service when they do not have to spend actual money. Following the approach suggested by Lusk (Reference Lusk2003), the script instructed participants to make their selections as if they were making an actual purchase in a grocery store. Participants were also asked to remain mindful of any budget constraints and consider the opportunity cost of spending money on the product in question. To reinforce these instructions, the script also provided an explicit discussion of the nature of hypothetical biases by citing a recent study where people overstated their willingness to pay for a food product in the context of a hypothetical survey.

4. Data collection

The survey was administered online using the Qualtrics platform, an integrated cloud-based software system that allows the creation, distribution, and analysis of online surveys. The survey was disseminated to potential participants via Dynata, a panel company that provides access to proprietary pools of respondents in the US and elsewhere in the world.

The three geographical regions that we targeted were Florida, the Northeastern region of the US, and Canada’s Eastern provinces and territories. Based on the US Census, the Northeastern region of the US includes the states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. This region was chosen to ensure that these states had no contiguity with Florida and that a significant distance separated the region from Florida. In addition, this region is a prime export destination for Florida produce. The provinces and territories of Canada that we targeted were New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec. These are also the provinces and territories where most of Florida’s tomatoes are exported. Given the significant French-speaking population in these parts of Canada, we translated the survey into French to avoid any participation bias that could arise because of language incompatibility.

We used several screening questions to minimize any potential bias from the respondents’ profession and ensure that respondents had recent shopping experiences to make informed choices and were the actual decision makers to more accurately reflect behavior related to tomato purchasing decisions. These include whether (1) the respondents were the primary grocery shopper in their household or shared this responsibility equally with someone else; and whether (2) neither the respondents nor their household members worked for a marketing research company, advertising agency, public relations agency, newspaper, food product manufacturer, or tourism agency. Furthermore, we used quotas based on age and income data based on the latest US and Canadian censuses to obtain a representative sample of the targeted populations. Attention checks were included to ensure respondents remained attentive and provided conscientious responses throughout the survey (Jones et al., Reference Jones, House and Gao2015). For example, within a matrix of Likert scale questions, we included an item instructing respondents to select “Strongly agree” to confirm they were reading the questions carefully. Furthermore, Dynata tracks IP addresses to detect and prevent multiple submissions from the same location, so we were provided with these IP addresses to verify that there were no duplicates in our dataset.

The data were collected between July and August 2023. The timing of the survey does not align with Florida’s primary tomato growing season, as production in Florida is limited during the summer months. However, the hypothetical nature of choice experiments allows respondents to express preferences for tomatoes and their attributes regardless of actual market availability. Hence, participants were presented with scenarios where all options were available, which enabled us to assess their preferences independent of the season. Moreover, consumer perception of and preference for the “Fresh From Florida” logo are likely to remain relatively stable throughout the year. Brands and logos build equity over time (Quester and Farrelly, Reference Quester and Farrelly1998), and the “Fresh From Florida” program promotes the brand year-round, maintaining consumer awareness even during off-season periods. While actual purchasing behavior might be influenced by product availability, our study focused on measuring stated preferences in a controlled setting.

5. Sample characteristics

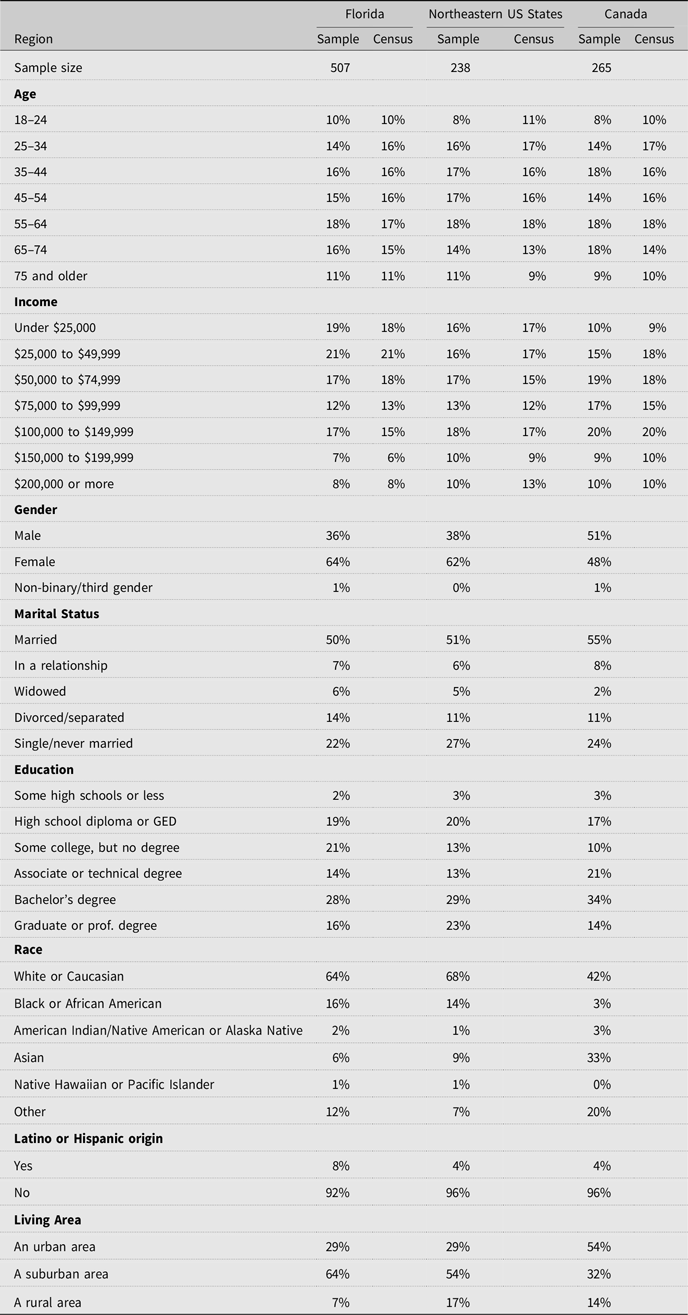

After passing the screening questions and attention check, 507 respondents completed the survey in Florida, 238 respondents from the northeastern regions of the US, and 265 respondents from the Eastern provinces and territories of Canada.Footnote 4 Hence, our sample is roughly equally distributed between Florida consumers and out-of-state consumers.

Table 2 shows that for the two quota variables that we used, age and income, the demographic characteristics of our respondents are similar to those of the census data of each region. However, Table 2 also reveals a significant difference in gender distribution between Canada and the US. Indeed, the proportion of female respondents in Florida and the Northeastern US states respondents (64 and 62%, respectively) is much higher than in Canada, where female participation in grocery shopping activities is much lower (48% female). It also implies that male participation in those activities is much lower in the US than in Canada.

Table 2. Sample characteristics

Note: The categories for education and race were slightly modified for Canadian respondents to reflect the Canadian education system and demographic classifications used in Canada. For education, the categories were some high school or less, high school diploma, some university but no degree, diploma of college studies, bachelor’s degree, master’s, or doctorate. For race, the categories were White, Black, Indigenous, Asian, Pacific Islander, and Other.

This gender disparity is attributable to our sampling approach and our screening for primary grocery shoppers. We implemented screening questions at the beginning of the survey to ensure respondents either had primary responsibility for grocery shopping or shared this responsibility with others in their household, as these individuals are the key decision-makers who ultimately determine food purchases. We further employed a non-probability quota sampling method with quotas on age and income to achieve representation across these characteristics, but we deliberately did not impose quotas on gender. Our intention was to reflect the market realities of tomato shopping rather than strictly mirroring general population demographics. In the US, women tend to be more involved in grocery shopping activities. According to the Pew Research Center (2019), women do more cooking and grocery shopping than men among US couples. Therefore, our US sample naturally included a higher proportion of female respondents, aligning with this market reality.

In contrast, the more balanced gender composition in the Canadian sample may reflect the more equal division of household chores, including grocery shopping, between men and women in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2019). Hence, by not imposing gender quotas and screening for primary shoppers, our sampling method captured differences in gender roles and shopping responsibilities between the US and Canada. So, while our samples differ in their demographic composition between the US and Canadian markets, these differences reflect the actual shopping populations in each region. This approach makes our results more applicable for producers, marketers, and policymakers, for which the behavior of the actual shoppers’ population is more relevant than that of the general population.

Furthermore, this gender disparity should not affect the relevance of our comparisons across regions. Indeed, findings regarding the effects of gender on consumer preferences for state branding programs have generally been mixed. Carpio and Isengildina-Massa (Reference Carpio and Isengildina-Massa2009), for instance, found gender to have an effect on the WTP for locally grown animal products, but found that the effect was non-existent for produce; similarly, Ruth and Rumble (Reference Ruth and Rumble2016) found that gender did not have an effect in the case of Florida state-branded strawberries.

Canada shows the highest proportion of bachelor’s degree holders, while the Northeast leads in graduate/professional degrees. Both Florida and the Northeast show a white majority, while Canada’s sample is more diverse with a notably larger Asian population. The Black/African American population is highest in Florida, followed by the Northeast, and significantly lower in Canada. In terms of living areas, Florida is mostly suburban, while Canada is predominantly urban. The Northeast has a more balanced distribution but is more suburban than the two other regions.

6. Results

6.1. Logo recall and perception of Florida

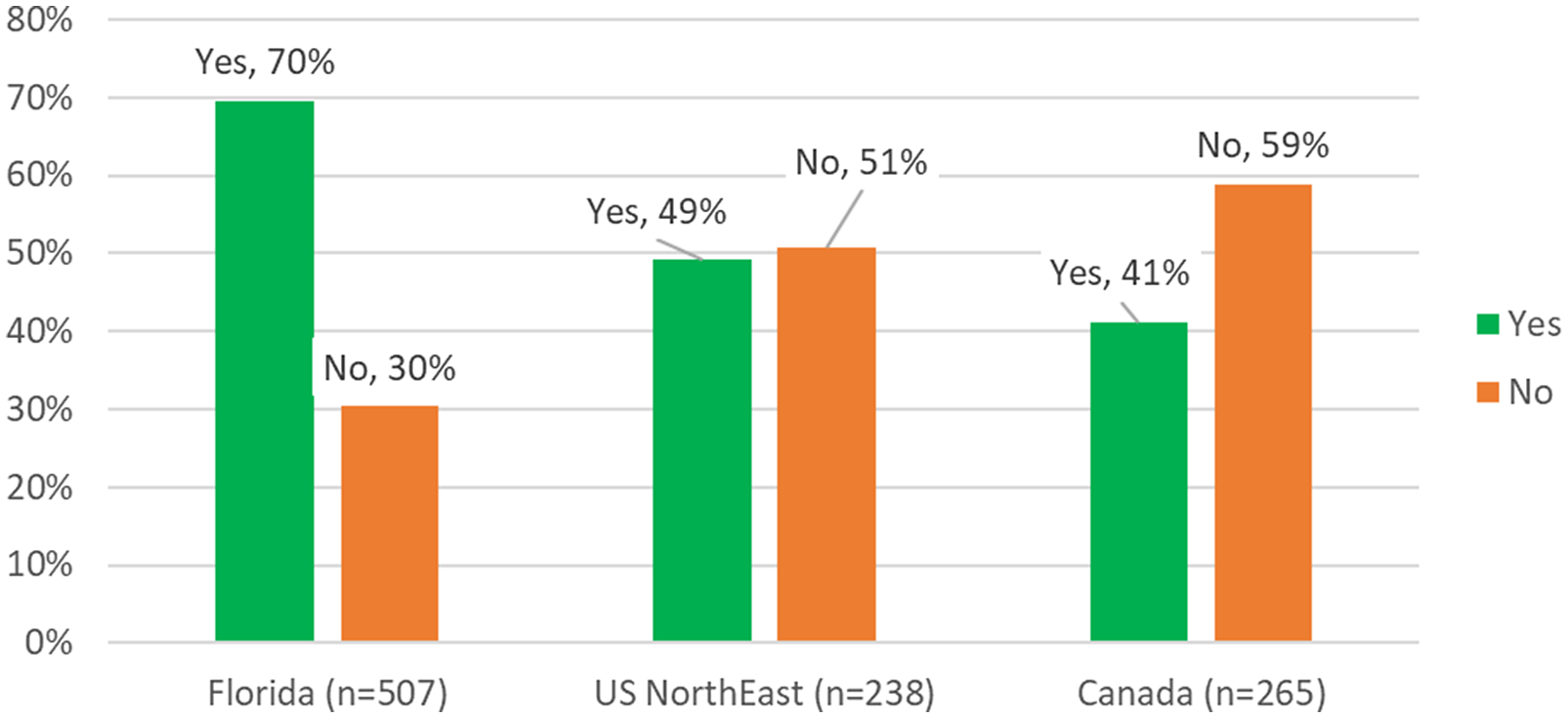

Figure 2 shows that 70% of Florida respondents reported recalling seeing the “Fresh From Florida” logo before taking the survey. The recall rate in the northeastern region of the US was significantly lower (49%) but higher than the recall rate in Canada (41%). These results align with expectations that the logo recall should be higher in its home state and lower in distant markets where the program’s reach is expected to be less prominent.

Figure 2. “Fresh From Florida” logo recall across study regions.

One caveat needs to be noted. The logo recall question was asked after the choice experiment to avoid drawing attention to the logo beforehand, which could have biased our main research results. Although respondents were asked to base their recall on prior exposure, their brief exposure to the logo during the choice experiment may have influenced the results shown in Figure 2.

Table 3 summarizes the results for Canadian respondents, including the breakdown of visit frequency to Florida, opinions of Florida, and logo recognition. Approximately 21% of the Canadian respondents had frequently visited Florida, 47% had visited Florida occasionally, 23% had never visited Florida but were interested in visiting, and 9% had never visited Florida and were not interested in visiting.

Table 3. Visits, logo recall, and opinion of Florida of Canadian respondents (n = 265)

As our study primarily focuses on understanding the preferences of out-of-state consumers for Florida produce, the questions related to the opinion of Florida were only asked to respondents in Canada and the Northeastern region of the US. To be precise, we use three 7-point Likert scale questions formulated to assess these respondents’ opinions of Florida. The questions were “Florida should be a model of inspiration for other states,” “I would be happier if I could live in Florida,” and “My opinion of Floridians is very positive.” We averaged the responses to construct a composite variable, which we named the Florida Opinion Score, with higher values indicating a more favorable opinion of Florida.

As expected, Canadian respondents who had never visited Florida and were not interested in visiting had the lowest Opinion of Florida score (3.68). They also had the lowest logo recall rate (24%). Respondents who visited Florida frequently had the highest opinion of Florida (5.21) and the highest logo recall rate (60%). Respondents who had occasionally visited Florida, or those who had never visited but were interested in visiting Florida, also had a fairly positive opinion of Florida (4.84 and 4.80, respectively). However, less than half of the respondents in these two groups recalled seeing the “Fresh From Florida” logo (37 and 39%, respectively).

Our study cannot determine whether respondents who visit Florida recalled the logo from exposure in Canada or during Florida visits. However, the recall rate among those who never visited Florida indicates the program’s reach in Canada, as their exposure would have been solely through FDACS promotional activities. While the recall rates for the two groups who have never visited Florida (39 and 24%, depending on their interest in visiting Florida), are lower than for the group who has frequently visited Florida (60%), these recall rates are nonetheless fairly significant in magnitude, demonstrating the program’s success in building brand recognition and awareness in Canada.

Overall, these results suggest that Canadian respondents had a fairly positive perception of Florida. More than two-thirds of them (68%) had occasionally or frequently visited Florida, and visitation frequency to Florida was positively associated with both opinion of the state and recall of the agricultural marketing logo.

As Table 4 shows, the breakdown of those responses for the Northeastern US respondents is similar to that of Canadian respondents. Frequent visitors to Florida again had the highest opinion score (5.36) and logo recall rate (63%), while those who never visited and were uninterested had the lowest opinion (3.58) and recall (13%). The average opinion of Florida was about the same among Northeastern US respondents (average 5.03) compared to Canadian respondents (average 4.80). As with the Canadian respondents, visitation frequency appears to be a key factor influencing both their opinion of Florida and logo recall for Northeastern US respondents. Interestingly, Northeastern respondents who had never visited Florida but were interested in visiting had a higher recall rate (56%) than respondents who had occasionally visited Florida (42%). This could be because of the small number of respondents that fall into the “never visited but interested” category (N-25), which would lead to less reliable results, or because this group may be more attentive to Florida-related marketing materials due to their interest in potentially visiting the state.

Table 4. Visits, logo recall, and opinion of Florida of Northeastern US respondents (n = 238)

6.2. Consumer willingness to pay for the “Fresh From Florida” logo

We used NLOGIT 5.0 software to estimate the nested logit model and calculate part-worth utility value estimates for the “Fresh From Florida” label and other tomato attributes. The nested logit model allows for different substitution patterns between choosing one of the alternatives versus opting out.Footnote 5 In our case, however, the opt-out option represents a nest with only one choice. Accordingly, we followed Hensher and Greene (Reference Hensher and Greene2002) where the opt-out option is specified as a degenerate branch. In this case, the inclusive value (IV) parameter for the opt-out branch needs to be normalized to 1 to permit identification. To do so, we used NLOGIT commands outlined in Hilbe (Reference Hilbe2006) to constrain the IV parameter of the degenerate branch.

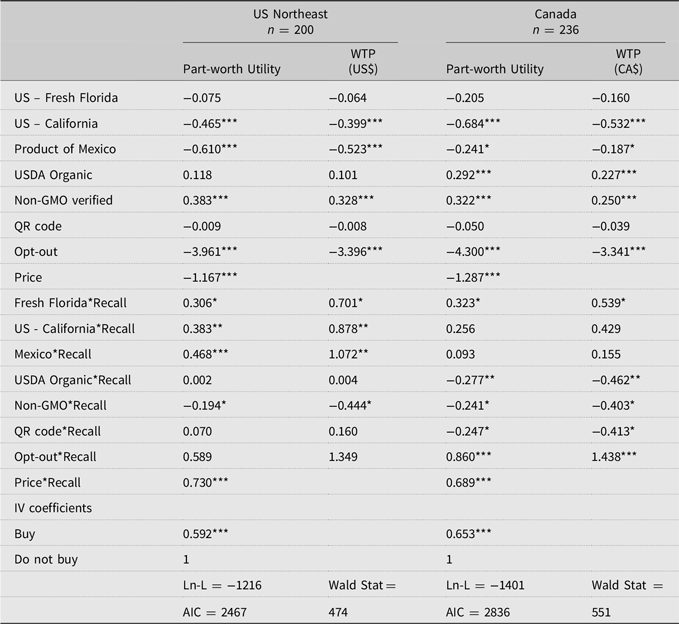

The Delta method (Wald procedure) was used to construct the standard errors for these WTP estimates, with results presented in Table 5. Additionally, we estimated a mixed logit model to examine preference heterogeneity across respondents. This model allows preference parameters to vary randomly across individuals rather than remaining fixed and can, therefore, account for unobserved preference heterogeneity in the sample. Results for the mixed logit model are presented in Table 6.

Table 5. Nested Logit Model – Utility (part worth) and WTP values for round tomatoes among different regions of the US and Canada (Nested Logit Model)

Three, two, and one asterisk indicated significance at 1, 5, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 6. Mixed logit model – utility (part worth) and standard deviations for round tomatoes among different regions of the US and Canada (mixed logit model)

Three, two, and one asterisk indicated significance at 1, 5, and 10% levels, respectively.

The mixed logit in Table 6 shows the preference heterogeneity for the utility-part worth associated with each attribute. The standard deviation for the Fresh from Florida program is statistically significant (p < 0.01) and comparatively large for Florida respondents, which implies that there is significant heterogeneity of consumer preferences for the program within the state of Florida. This further suggests that the program might benefit from targeted marketing strategies that account for the potential presence of different consumer segments within the state.

In contrast, Northeastern and Canadian consumers show a lower preference heterogeneity for the “Fresh From Florida” label. Another interesting result is that preference for Mexican origin has the highest heterogeneity across the three regions, which suggests strong variations in the consumer responses to imported tomatoes from Mexico compared to other origins.

As expected, Table 5 shows that respondents in Florida have the highest WTP for the “Fresh From Florida” logo (0.562 US$/pound). In fact, the WTP for the state logo is higher than for any other attribute of the tomatoes, which demonstrates the program’s ability to build equity and establish a positive brand image in its home state. In contrast, respondents from the Northeastern region of the US and the Eastern region of Canada did not exhibit a statistically significant WTP for tomatoes with the “Fresh From Florida” logo. In line with expectations, this result shows that the program’s influence is more limited outside of Florida.

Tomatoes labeled with the Californian State program logo are heavily discounted in all three regions under study. The discount is particularly large in Canada, where respondents discount California-grown tomatoes by 0.536 CA$/pound. Similarly, tomatoes imported from Mexico are discounted in Florida and, to a greater extent, in the Northeastern region of the US. Canadian respondents, on the other hand, do not appear to discount tomatoes from Mexico.

The significant discount that consumers in all three regions expressed for the California State program attribute was an unexpected result. This finding was particularly interesting in the case of the Canadian respondents since they did not discount tomatoes produced in the US or Mexico. This implies that Canadian attitudes toward imported tomatoes cannot explain the lower WTP for California tomatoes. It is worth reiterating that the California State marketing program was included to be used as a point of reference so that the “Fresh From Florida” program could be compared to similar initiatives. An investigation into the reasons for this finding is, therefore, beyond the scope of this study. However, we could suppose that consumers’ attitudes and perceptions regarding the quality and freshness of California-grown tomatoes, the visual appeal of the logo, and familiarity with the brand could explain the negative utility derived from the Californian logo. Further research could explore the reasons why California-grown tomatoes are discounted in these regions.

The WTP estimates for the USDA organic and non-GMO verified attributes are positive and statistically significant. It is worth noting that residents in Florida have a substantially higher WTP for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes (US$ 0.562/pound) than for USDA organic tomatoes (US$ 0.206/pound). This result is consistent with other studies that suggest that consumer preferences for local food sometimes outweigh preferences for organic food (Adams and Salois, Reference Adams and Salois2010; Meas et al., Reference Meas, Hu, Batte, Woods and Ernst2015). The WTP for the non-GMO verified attribute is the largest in the Northeastern region of the US and is larger than the WTP for organic products for both US and Canadian respondents. The WTP for the QR code is variable and relatively small, which may be explained by the fact that consumers do not perceive significant value in this technology or that the QR code in our study was not linked to any specific online information. It is statistically insignificant in Florida, positive and statistically significant in the Northeast of the US, and interestingly, negative and statistically significant for Canadian respondents. This suggests, as we could expect, that consumer preferences for tomato attributes among these three regions are relatively heterogeneous.

The opt-out parameter represents the utility that respondents derive from declining to buy any of the tomato options presented to them in the paired alternatives of the choice experiment. Accordingly, the negative of the WTP value for the opt-out option corresponds to the average WTP for a tomato produced in the US without any of the other attributes. The opt-out parameter has a significant negative value in all cases, which indicates that, on average, respondents were averse to choosing the opt-out option and, therefore, would prefer selecting one of the tomato alternatives.

Finally, the inclusive value (IV) coefficients for the “Buy” option are all statistically significant and with values close to 1, which suggests a relatively weak correlation among alternatives within nests. However, the Canadian sample shows the strongest correlation within nests (0.779, p < 0.01), which implies some regional variation in the decision-making process regarding those alternatives.

The mixed logit in Table 6 shows the preference heterogeneity for the utility-part worth associated with each attribute. The standard deviation for the Fresh from Florida program is statistically significant (p < 0.01) and comparatively large for Florida respondents, which implies that there is significant heterogeneity of consumer preferences for the program within the state of Florida. This further suggests that the program might benefit from targeted marketing strategies that account for the potential presence of different consumer segments within the state.

In contrast, Northeastern and Canadian consumers show a lower preference heterogeneity for the “Fresh From Florida” label. Another interesting result is that preference for Mexican origin has the highest heterogeneity across the three regions, which suggests strong variations in the consumer responses to imported tomatoes from Mexico compared to other origins.

6.3. Consumer willingness to pay and logo recall

As noted earlier, consumer recall of the “Fresh From Florida” logo is an important measure of the success of the program as it denotes its ability to establish brand recognition. As such, recall of the logo may potentially influence preferences and WTP for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes. To better estimate the impact of logo recognition, and thus the previous exposure of consumers to the program and their recollection of it, we interacted the logo recall variable with the other parameters of the model. With that, we can separate the effect of consumers’ inherent preferences for Florida-grown products from the program’s ability to influence consumer preferences and purchasing decisions through its promotional efforts.

Table 8 shows that the interaction term between the logo recognition variables and the “Fresh From Florida” attribute is not statistically significant for Florida residents. This implies that recall of the logo does not translate into higher WTP for Florida-grown products for Florida residents. While this result may appear counterintuitive, we could suppose that Florida residents have an inherent preference for produce grown in their own state. So regardless of whether they had been previously exposed to the “Fresh From Florida” logo and can recall it, Florida consumers would naturally be more inclined to pay a premium for produce grown within their state. This suggests that providing visibility to the logo, whether directly on produce, on the packaging, or with shelf displays, would probably be more effective in influencing Florida residents’ purchasing behavior than other promotional and marketing activities aimed at building brand recognition.

On the other hand, the results in Table 7 show that for Northeastern respondents, the interaction term between the logo recognition variables and the “Fresh From Florida” attribute is positive and statistically significant. This indicates that recalling the logo correlates with an increase in Northeastern respondents’ WTP for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes. This positive relationship would be consistent with the program’s efforts to promote Florida-grown produce through its various promotional efforts. As a result, respondents who recall the logo may attribute certain qualities to produce with the label, such as freshness, healthiness or positive association with Florida, resulting in a higher premium. Conversely, consumers who do not recall the logo may not have been subject to the same marketing efforts and, therefore, may not have developed the same positive associations with Florida produce, hence their lower WTP.

Table 7. WTP estimates interacted with logo interaction – nested logit model

Interestingly, the other interaction terms in Table 8 show that recall of the “Fresh From Florida” logo positively correlates with the WTP of Northeastern respondents for tomatoes labeled with the California State program and for those imported from Mexico. This could be explained by consumers who recall the logo having an inherent interest in produce origin, leading them to pay attention to geographical indicators and pay premiums for perceived quality attributes. Additionally, consumers who recall the Florida logo may view California and Mexican produce as reasonable substitutes, leading to an increased WTP for these origins.

Table 8. WTP estimates for respondents with a neutral or positive opinion of Florida

Table 8 also shows that the interaction term between the logo recall variable and the opt-out variable is positive and statistically significant, which implies that recall of the logo correlates with an increase in the utility of opting out and, correspondingly, a decrease in the utility of choosing one of the tomato alternatives. This suggests respondents who recalled the logo were more likely to opt out of purchasing tomatoes. One explanation could be that consumers who pay attention to tomato quality attributes and recall the logo may have higher quality expectations, making the tomato alternatives appear less appealing. It is also worth noting that recalling the logo does not appear to increase Canadian respondents’ WTP for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes in any statistically significant way.

6.4. Consumer willingness to pay and opinions of Florida

The literature on country image has shown that the perceptions that consumers have of a country can influence their evaluation of goods imported from that country and their subsequent buying decisions (Roth and Diamantopoulos, Reference Roth and Diamantopoulos2009; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Barnes and Ahn2012). While Florida is a state and not a country, we may still presume that it holds a unique place in the minds of many people in the US and the rest of the world. On the one hand, Florida is often a preferred vacation destination, especially during the winter months for many of the northerners living in colder climates. As a result, the state may suggest images of sunshine, beaches, fishing activities, and theme parks, which may lead to positive associations with the way consumers view goods produced in the state. On the other hand, Florida also often attracts attention in the media for its unique political environment and cultural identity. Media coverage, when negative, could potentially lead to adverse connotations associated with goods produced in Florida. Hence, respondents’ opinion of Florida may positively or negatively influence their willingness to pay a premium for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes, depending on their views of Florida.

To verify this, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to isolate the impact of negative views of Florida. We removed 29 respondents in the Canadian sample and 38 in the Northeastern sample with a Florida Opinion Score less than or equal to 2 on the 7-point Likert scale, representing the most unfavorable opinions. The sample size of those with negative opinions being insufficient for a meaningful statistical analysis, we chose this approach to focus our analysis on the target audience most likely to be influenced by the “Fresh From Florida” program, which would be consumers with neutral or positive perceptions of Florida.

Results for this subsample are presented in Table 8. The comparison with Table 8 reveals that for Northeastern consumers, removing consumers with negative views of Florida does not change the results and that the effect of logo recall on the WTP for “Fresh From Florida” remains statistically significant. For Canadian respondents, however, the comparison between Table 8 and Table 8 indicates that the effect of logo recall on WTP for “Fresh From Florida” becomes statistically significant at the 10% level. This suggests that the overall perception of Florida as a state can affect the way Canadian consumers respond to the “Fresh From Florida” logo. Negative opinions of the state image diminish the potential positive influence of the logo on consumer preferences. In contrast, when consumers have a more neutral or positive view of Florida, the logo is more likely to positively influence their preferences and WTP.

7. Conclusion

The “Fresh From Florida” program is a state agricultural marketing initiative that distinguishes itself by having succeeded in extending its reach far beyond its state’s borders. This contrasts with most other state marketing programs in the rest of the US, whose promotion and marketing activities remain mainly focused within the boundaries of their own state. Accordingly, most of the literature on the topic has focused on the effectiveness of these programs in their home states or in close-by contiguous states. However, the results of these studies cannot be generalized to the effect of state marketing programs in regions with significantly greater distances from the state of interest because the effect of proximity does not apply in these cases.

This study aimed to address this question by assessing the impact of the “Fresh From Florida” program on consumers’ preferences in states located a significant distance from Florida. To do so, we conducted an online choice experiment with tomatoes as a representative product and with the Northeastern region of the US and the Eastern region of Canada as our study markets. We chose this produce because of the significant volumes of tomatoes that Florida ships to these regions during the winter months. These US and Canadian regions were targeted because the department managing the program, the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, has conducted promotional activities and developed partnerships with retailers in these regions, and the Florida produce industry faces significant competition with Mexican imports in these markets.

Our study also surveyed consumers in Florida so that the impact of the program in those distant regions could be compared with its home state. As expected, awareness of the program in Florida is significant, with 70% of respondents reporting recalling seeing the “Fresh From Florida” logo before taking the survey. Florida respondents are also willing to pay a substantial price premium for the tomatoes with the “Fresh From Florida” logo. The WTP for the “Fresh From Florida” attribute among Florida respondents is actually larger than the WTP for the USDA Organic and Non-GMO Project Verified attributes. While such a marked preference for state-grown food is consistent with other studies that have shown that the WTP for state-branded food can be higher than for organic foods (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Bernard and Pesek2013; James et al., Reference James, Rickard and Rossman2009; Loureiro and Hine, Reference Loureiro and Hine2002), this result still demonstrates the program’s effectiveness in promoting Florida-grown produce within its home state.

However, our analysis reveals that, on aggregate, the program’s influence on consumer preferences is relatively limited in the two geographically distant markets that we targeted for the survey, i.e., the Northeastern region of the US and the Eastern region of Canada. Indeed, the premiums that respondents from these regions were willing to pay for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes were not statistically significant. Nonetheless, with an average logo recall rate of 49% in the Northeastern region of the US and 41% in the Eastern region of Canada, the program appears to have achieved some success in raising awareness of Florida-grown produce in these geographically distant markets.

Our study also focused on the effect of logo recall on consumer WTP since this variable is often used to gauge the effectiveness of these types of programs in building brand equity. Our results indicate that among Northeastern US respondents, recall of the logo has a statistically significant interaction effect on the WTP for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes. It is also worth mentioning that a significant share of respondents in the Northeastern region of the US and in Canada recall seeing the logo even if they had never visited Florida. This indicates that the “Fresh From Florida” program has managed to extend its reach beyond the state’s borders. Together, these findings indicate that previous exposure to the marketing and promotional efforts of the program correlates with a higher WTP for “Fresh From Florida” produce, even in geographically distant markets where consumers may not consider the food as locally grown.

We also sought to explore whether consumer opinion of Florida could affect the WTP for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes since the literature on country image has shown that the perception that consumers have of a country can affect purchasing decisions. Overall, we found that consumers’ opinion of Florida in the Eastern region of Canada and in the Northeastern region of the US is relatively positive. A notable result in this respect is that while, on average, Canadian respondents do not appear to be willing to pay a premium for “Fresh From Florida” tomatoes, this effect became positive and statistically significant when we restricted our samples to respondents with positive or neutral views of Florida.

In conclusion, this research informs on the ability of state agricultural programs to promote their product in geographically distant markets successfully. Our study shows that initiatives such as the “Fresh from Florida” program do have the ability to raise awareness and influence consumer WTP for state-grown foods. In our case, however, the program’s impact on the WTP is conditional on its ability to first build sufficient brand equity. In addition, our study shows that consumers’ views and opinions of the state in question can also affect the WTP for state-branded products.

A limitation of our study is the timing of data collection, which occurred during a period when Florida-grown tomatoes were not typically available. While the hypothetical nature of the choice experiment mitigates the impact of seasonal availability on consumer preferences, seasonal factors could influence perceptions in ways not fully captured by our study. Future research could align data collection with the production season to explore potential seasonal effects on consumer preferences.

This study suggests several areas for further investigation. Given the increasing use of technology in food marketing and labeling, future research could examine how QR codes could be used to provide additional information about state marketing programs and whether access to such program-specific information influences consumers’ willingness to pay for state-branded products. Additionally, although the primary focus of this study was the effectiveness of the “Fresh From Florida” program, the unexpected findings related to the “CA Grown” label suggest that additional factors, such as brand equity, country-of-origin effects, and consumer ethnocentrism, may influence consumer preferences. Future research could build upon these insights by investigating how these factors shape the effectiveness of state branding programs across different markets. A better understanding of these factors would help state governments refine their marketing strategies and potentially allow their agribusiness industry to operate successfully in geographically distant markets.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/aae.2024.39.

Data availability statement

The data for the study can be accessed at openICPSR (https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/): Project Title: openicpsr-206221.

Financial support

This project was supported by a USDA-FSMIP grant: “Enhancing the Local, National, and International Reach of Florida Agricultural Products: Analyzing the Determinants of Consumer Preferences for the Fresh from Florida Program.” FAIN Number 23FSMIPFL1013.

Competing interests

Authors Alexandre Magnier, Lijun Angelia Chen, Bachir Kassas, and Kimberly Morgan declare none.

AI statement

Except for Grammarly to proofread the text, we did not use AI tools to generate content for this article.