Introduction

The scourge of poor housing conditions was a persistent issue in Irish political discourse prior to independence, and housing issues, including mortgage debt and homelessness, continue to be politically charged to the present day.Footnote 1 This article focuses on the period immediately following the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922 until the start of World War II, at a time when the new state was finding its feet and implementing strategies to tackle the ongoing slum problem.Footnote 2 Poor urban housing conditions had been attributed a role in politicizing elements of the population, including suggestions that neither the 1913 Lockout nor the 1916 Rising might have happened had the population been adequately housed.Footnote 3 Appalling conditions in Dublin were highlighted in an inquiry published in 1914, whose appendices also revealed shocking circumstances in the smaller provincial towns.Footnote 4 Given this backdrop, together with severe housing shortages, it is unsurprising that one of the first acts of the Provisional Government in 1922 was to set aside one million pounds to encourage house building. Despite hopes that such efforts would eliminate the housing problem, it persisted into the 1960s.Footnote 5

Although housing is a fundamental issue, with a huge impact on individuals and society, as well as leaving a long-lasting imprint on the landscape, it has been surprisingly under-researched by historians and historical geographers in Ireland.Footnote 6 Much of the emphasis has been on the broad national picture or on Dublin and, to a lesser extent, the larger cities of Cork and Belfast. With the exception of a small number of recent studies, notably Peter Connell's examination of municipal housing in Meath, and Fióna Gallagher's unpublished Ph.D. thesis on Sligo town, there has been little research on the twentieth-century housing experience of Ireland's provincial towns.Footnote 7 This article begins to address that absence by exploring how the problem of urban housing provision was addressed in provincial towns in the early years of the Irish Free State. While government policies and grants influenced all housing provision, the focus here is on dwellings built by urban local authorities. It draws on Dáil (parliamentary) questions and reports, legislation, census data, annual reports of the department of local government and contemporary newspaper accounts, including reporting of urban district council (UDC) meetings. When combined, these various sources begin to reveal the housing challenges and achievements of the period.

While Irish housing policy shared many concerns in common with other European countries, such as post-World War I housing shortages as well as the need to address poor conditions for those in need, there are also particularly distinctive features of the Irish inter-war experience. Housing formed part of the post-independence state building project, but there was also an ongoing anti-urban bias in local authority provision.Footnote 8 The provincial towns played an important role in housing provision during this period, as this article will reveal.

Irish housing in limbo?

Anne Power's 1993 volume, Hovels to High Rise, includes an overview of Irish state-sponsored housing within her analysis of social housing in five European countries, but of necessity this is an overview rather than an in-depth study. In a chapter entitled ‘Irish housing in limbo’, she observes that ‘the inter-war years were dominated by economic and political problems that left Ireland's housing situation very little better than before independence’.Footnote 9 Certainly, the housing programme was slow to get underway, due to political upheaval and high post-war construction costs.Footnote 10 But is it really fair to describe this as a limbo period?

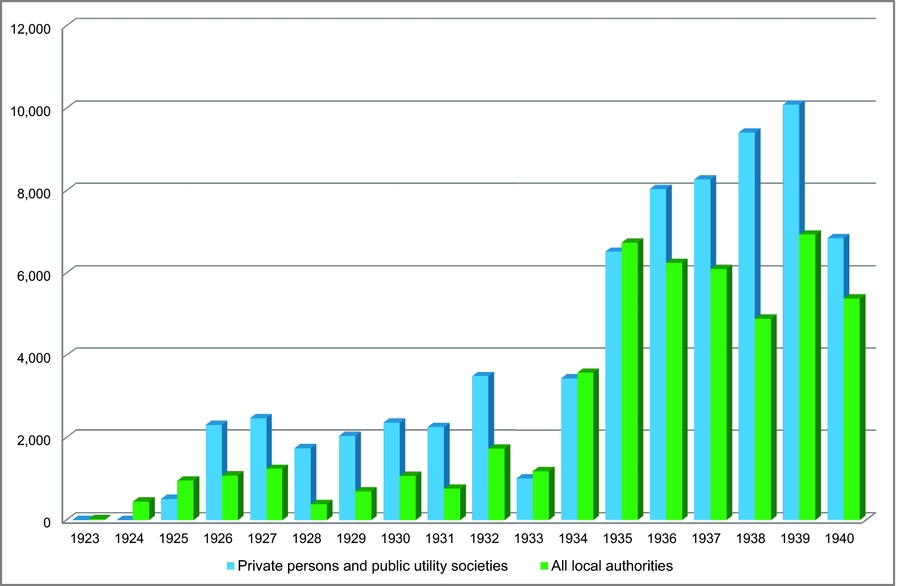

In one sense, this might appear to be true. The 1946 census revealed Irish housing conditions that were still very poor. Only 36 per cent of dwellings had inside piped water, while inside sanitary fittings (23 per cent) and fixed bath (15 per cent) were even less common.Footnote 11 However, these findings generally reflect older housing stock, whereas newer dwellings had superior facilities. Indeed, the sheer scale of housing completions in the early years of the new state's existence is impressive. Only 8,750 dwellings had been erected by urban authorities in 40 years prior to 1922, whereas 6,441 local authority dwellings were erected or planned in five years from 1922 to 1927.Footnote 12 This further increased so that by 1940, local authority dwellings accounted for 84,000 units, over half of which had been completed in the 1930s.Footnote 13 Figure 1 displays all house completions that received state aid, both private and local authority dwellings in both rural and urban areas, showing increasing numbers over time.Footnote 14 It should be noted here that the severe housing shortage by the mid-1920s led the government to enact legislation providing grants to private builders and public utility societies (a form of co-operative housing association) building houses of a certain size and specification, albeit at lower rates than the grants made available to local authorities for house building, in an effort to encourage building. Indeed, between 1922 and 1932, more than twice as many private and public utility houses as local authority houses were completed countrywide.Footnote 15 This targeting of both middle- and low-income groups was not unique in a European context. Concessionary grants and subsidies were also used in France from 1928 to promote both owner-occupation and flat construction, while new building was heavily subsidized in inter-war Germany.Footnote 16 The Department of Local Government and Public Health annual reports outlined the numbers of dwellings completed which availed of such grants, but generally lumped private enterprise and ‘assisted self-help’ (public utility society housing) into a single category. Despite these limitations, the data give a useful impression of the scale of house completions over the study period.

Figure 1: Annual house completions under state-aided schemes from 1923 to 1940, showing both public and private dwellings

There had been important shifts in housing policy from 1922, but more importantly, huge numbers of families were taken out of abject poverty and rehoused in modern dwellings. These new housing schemes, particularly those erected in the 1930s with their distinctive appearance and layout, reshaped Irish cities and towns. The style of local authority housing built in the 1920s and 1930s generally followed the typical plans and site layouts identified by the Ministry of Local Government's five-volume series of model housing plans, issued in 1925, and subsequent additions.Footnote 17 In order to qualify for subsidy under the legislation, the regulations specified that houses were required to be in general accordance with prescribed plans or with other such plans as may be approved by the minister. Throughout the country, therefore, there is a tendency for council houses of this era to be readily identifiable. Streetscapes were changed through both the demolition of older slum dwellings and construction of new homes. The impact of this period resonates to the present day.

Dublin versus the rest

The evolution of Dublin's housing in the inter-war period has been well documented.Footnote 18 In brief, the 1920s saw an effort to build high-quality ‘model’ dwellings along ‘garden suburb’ lines. These were made available, most notably at Marino, for tenant purchase. ‘Reserved areas’ at the edges of Corporation schemes enabled private builders and public utility societies to build better houses, thereby increasing social diversity in the new areas.Footnote 19 By the late 1920s, cost factors led to construction of smaller houses with fewer rooms and a return to rentals. Flats were not favoured and did not become important until the 1930s, when they were erected in central slum clearance areas. One outcome of Dublin Corporation's 1930s dual policy of building central flats and suburban ‘cottages’ was to increase social segregation, with flats generally occupied by the poorest members of society.Footnote 20 This activity took place against the backdrop of a series of legislative changes, outlined below. The 1920s Housing Acts encouraged construction by private builders and public utility societies, reflecting the general shortage of housing. As in Britain, the 1930s saw a re-emphasis on slum clearance. Due to the dominance of Dublin's story, and the ongoing and vocal discussion of the capital's slums, it has been largely overlooked that the rest of the country was also struggling with inadequate housing conditions which urgently needed remedy. The remainder of the article explores the degree to which Ireland's provincial towns mirrored Dublin's housing experience during this period, as all urban authorities were operating under the same national legislation, and the extent to which distinctive patterns emerged.

One million pounds

In response to the ‘crying scandal’ of the slums, in both the cities and the smaller towns, in 1922 the Provisional Government set aside one million pounds to encourage house building.Footnote 21 Municipal authorities were given a free grant to cover two-thirds of the cost of construction, to which they were to contribute the remaining one third by way of a special housing rate (of at least 1s in the £) and a short-term loan (the latter equal to three times the produce of the rate). Overall, the councils would raise £125,000 from rates and a further £375,000 through short-period loans, so that, with the government's one million pounds, a total of £1.5 million would be made available nationally for the construction of an estimated 2,000 houses (based on an all-in cost per house of £750).Footnote 22

Some 71 local authorities (three-quarters of all in the Free State) adopted housing schemes under the scheme which was commonly known as the ‘million pound grant’. It was a noble gesture and kick-started building across the country, but the overall number of dwellings completed was very small. Already by 1923, the million pound grant was running out, and the question of value for money was coming to the fore. In a Dáil question in June 1923, John Lyons, a TD for Longford-Westmeath observed that just 11 houses were being provided in Athlone, which ‘do not come near providing the number of houses required’. Ernest Blythe, the minister for local government, replied that there was no additional money available; however, if the local authorities sold the houses already built, the government would agree to that money being used for further housing.Footnote 23 He continued by stating that the housing problem was ‘of appalling magnitude’, that the situation was ‘really terrible. . .exceedingly bad for the country, and it costs the country dear in many ways’. Every consideration would have to be given to getting ‘the best possible value for any money voted for housing’.Footnote 24 While subsidies to private builders were not an entirely satisfactory way of dealing with the problem, they had proven more cost effective than giving a grant to public bodies. ‘You would get as much out of £180, given to a private builder as £500, given to a public body.’Footnote 25 This early experience clearly laid the foundations for the mid-1920s housing legislation which promoted private development. It also partially helps to explain how the shift towards promoting owner-occupation, which became a hallmark of Irish housing policy, began.Footnote 26

Affordability was a major issue for housing providers. The credit received by the municipal authorities operating under the million pound scheme involved loans at 4½ per cent interest per annum over a repayment period of 15 years. The short term of the loan was such that rents were quite high for the houses which the councils built. In a Dáil question in 1927, for example, the local TD for Sligo, John Jinks, stated that the rents of 24 dwellings erected by the Sligo Corporation at Cleveragh and Ballytivnan in accordance with the 1922 scheme were so high ‘that the tenants find it impossible to pay these rents, and have petitioned the Corporation to have same reduced to a reasonable figure’.Footnote 27 Unfortunately, the banks refused to extend the period of repayment of the loan, which would have enabled local authorities to reduce the rents without adding a burden to the rates. Given these circumstances, some local authorities chose to sell their ‘million pound grant’ houses. In Dublin, the tenant-purchase policy was adopted, whereas some UDCs sold the houses for cash, which could then be used to provide further housing. Both options were adopted in Ballina, discussed below. While the ultimate effect was to promote owner-occupation, particularly when coupled with the promotion of private house construction under the 1924 and 1925 Housing Acts, the decision to sell these houses was driven more by pragmatism than ideology.

1924 and 1925 Housing Acts

By the end of 1924, many local authorities had completed their work under the million pound grant, and the Housing (Building Facilities) Amendment Act of 1924 was introduced to support urban local authority housing. This scheme, as modified by the 1925 Housing Act, offered higher grants per house to local authorities and public utility societies, with lower grants for private persons, and also extended it to the local authorities operating in rural areas under the Labourers (Ireland) Acts.Footnote 28 However, most local authorities experienced difficulties in obtaining loans to finance the balance of the cost, which meant that it was not possible to undertake large schemes. One outcome was the ‘reduced cost’ house plan produced by the Department of Local Government and Public Health. From 1922 to 1927, local authorities built 6,500 houses, adding to the 9,000 completed in the previous 40 years.Footnote 29

A complex range of issues typically arose when local authorities took responsibility for housing provision, as is illustrated by the following Dáil exchange. In April 1925, George Wolfe, a TD for Kildare, had asked why the Newbridge town commissioners had accepted people living outside the area as tenants for four of the six houses which they had completed under the act, ‘when there are many families living in one room who would gladly pay the weekly rent of 6/6’.Footnote 30 Seamus Bourke, the minister for local government and public health, responded that the selection of tenants for houses built under the 1924 Housing (Building Facilities) Acts was at the discretion of the local authority. This exchange highlights typical issues seen across the country: the small number of house completions, controversy over their allocation, prevalence of one-roomed dwellings in the town and, finally, the high weekly rent for the new houses. Incidentally, the six one-storey houses which caused such controversy in Newbridge had been built, as a cost-saving measure, with no back entrance; this was to be an ongoing annoyance for tenants.Footnote 31

Despite government efforts, the amount of housing provided by local authorities under the 1924 Act was small. Furthermore, not all authorities undertook construction. In November 1925, the question of housing in Edenderry was raised in the Dáil. At a recent inquiry concerning the purchase of the old workhouse buildings to provide additional housing accommodation, it was stated that ‘there were human beings living in stables in this town, and that the stables were owned by members of the Town Commission’.Footnote 32 The town commissioners had refused, by a small majority, to proceed with a new housing scheme ‘as demanded in a memorial signed by the majority of the residents’. Furthermore, it was alleged that the lack of suitable housing was preventing Messrs Alesbury Brothers from employing a larger number of workers in their factory.Footnote 33

As had been suggested by Minister Blythe as early as 1923, it seems that grants were giving more value to private individuals than to local authorities. Comparisons of dwelling completions in Co. Carlow in 1928, to take just one example, showed that over six times the grant-in-aid given to each house built by a private individual was required for a house built by the local authority. The overall number of houses built in the county was small; just 7 dwellings had been built by private individuals using government grants, and 12 by the local authorities.Footnote 34 Thus, each private house was completed with government grants of less than £63, contrasting with over £400 in grant-aid for each local authority house.

Evidence of the urban housing need and responses

The 1926 census provides a useful baseline for housing conditions because there were relatively few housing completions before that date. It revealed widespread overcrowding and the need for intervention. One indication of need was the fact that both workhouses and army barracks were being considered for housing purposes in the 1920s.Footnote 35

The number of families occupying one-room tenements is presented for both 1911 and 1926.Footnote 36 In Dublin (excluding Rathmines and Pembroke), some 23,655 families lived in one-roomed tenements, a feature which had been singled out as a major cause of high death rates in Dublin's slums.Footnote 37 However, the problem of one-roomed dwellings was not confined to the cities; furthermore, some provincial towns had experienced a significant deterioration on the conditions detailed in 1911. One third (i.e. 29) of the 87 ‘towns possessing local government’ in 1926 had seen an increase in the number of families occupying one-room tenements compared with the previous census.Footnote 38 Of these, Waterford had the greatest problem, with 359 families living in one-room tenements, although this was a relatively static figure. In Sligo, the number of one-room tenement families had grown six-fold (to 242), while significant increases were also experienced in Mullingar (over 350 per cent), Bray (over 250 per cent) and Athlone (over 180 per cent).

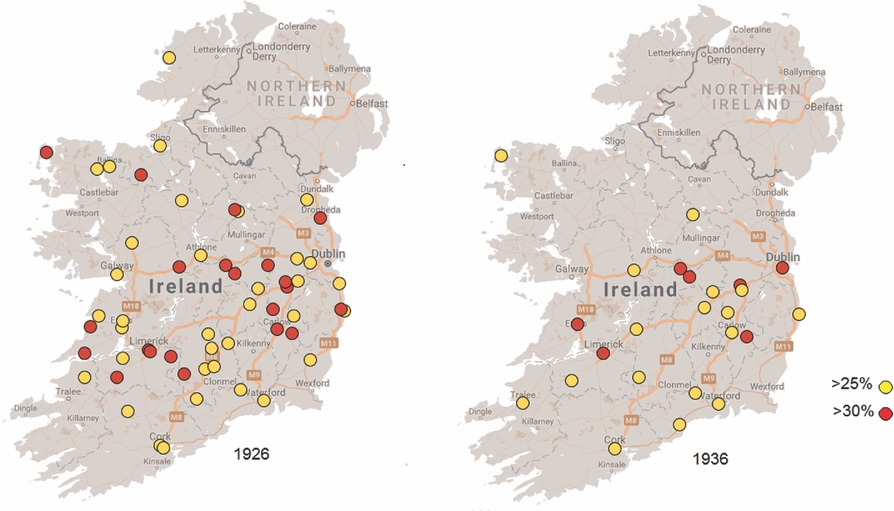

The analysis of overcrowding, when measured in terms of the percentage of persons in families having more than two persons per room, can be used to give a more in-depth picture of the national situation, as each town of over 500 inhabitants is listed in the census.Footnote 39 Figure 2 highlights towns where 25 per cent and 30 per cent of the population was overcrowded by this measure, and shows that the problem was widespread. It is against this backdrop that the proposals for action, and their outcomes, should be measured.

Figure 2: Provincial towns where 25 per cent and 30 per cent of families experienced overcrowding, 1926 and 1936

As the census results became available (the housing volume was published in 1929), the need for policy change was clear. In July 1929, a circular letter issued by the Department of Local Government and Public Health asked urban authorities to survey the housing conditions in their areas, indicating the need for houses to meet unsatisfied demand and also to rehouse those displaced by clearance of unhealthy areas and to replace unfit houses.Footnote 40 These returns showed a great need for an attack on Ireland's urban slums and ultimately led to the new housing legislation of the early 1930s. Mary Daly has also suggested that senior officials in Finance felt that scarce resources had been misallocated in the 1920s to farmers and others building private houses and they now argued that funding should be targeted at slum clearance and those not in a position to provide decent housing for themselves.Footnote 41

In 1929, there was a general reduction in grants and an attempt to focus on the most vulnerable members of society. A uniform grant of £60 per house was made available to local authorities, while the possibility of obtaining advances from the Local Loans Fund was introduced. Among the conditions imposed, however, was the requirement that ‘as far as possible’ schemes would be confined to the erection of four-roomed houses of modified standard, where the all-in cost per house was not to exceed £350 (with a building cost of £300 per house). Already, the aspirational standards of the early 1920s, as seen in Dublin's Marino scheme, had to make way for a more pragmatic vision. Whereas the emphasis on slum clearance in the 1930s was generally associated with the new Fianna Fáil government which took office in 1932, it is clear that policy change was already underway in the late 1920s.

In December 1931, the new Housing Act introduced considerable changes, with a quicker method for the clearance of unhealthy areas and the repair or demolition of unfit houses.Footnote 42 Owners could be directed to demolish the dwellings and level the site, or the local authority could purchase the land and buildings and undertake the demolition themselves. In the first instance, the ‘unhealthy area’ could be cleared without loss to the rate-payers where the land was not required to rehouse displaced residents.Footnote 43 Compensation for property in an unhealthy area was now to be the site value less the cost of clearing and levelling the site, rather than simply basing the compensation on the value of the land as a cleared site available for development. The process of a Compulsory Purchase Order made by local authorities and confirmed by the minister was introduced for site acquisition for housing, with an inquiry to confirm the order in the case of objections. State assistance was now to be paid as an annual subsidy towards the loan charges, rather than lump sum grants. There were also changes to the Small Dwellings Acquisition Act aimed at encouraging private building.

The new Fianna Fáil government of 1932 introduced a new Housing Act with a similar slum clearance emphasis but which increased the rates of state contributions to schemes.Footnote 44 Two-thirds of the loan charges were to be granted where the houses were for people displaced, while one third were available for houses targeting the better-paid worker who was unable to pay a full economic rent. Limits were made to the all-in cost of houses on which contributions would be paid. This general framework was used for a decade or so until the Emergency (World War II) brought an end to construction.

A difficult balance

A major issue experienced in Ireland's provincial towns, as in other settings, was the challenge of balancing the different requirements of government and local authorities who provided houses, the tenants who rented them and the tax-payers who contributed to the costs through their local rates and taxes. There were ongoing difficulties in providing housing at a rent within the reach of those who required improved dwellings, without putting too great a burden on the rates. During the 1930s, Dublin Corporation debated the question of differential rents, but the decision to base the rent of working-class dwellings on ability to pay was not readily accepted and caused considerable difficulties for many years.Footnote 45 Equally, there was a great deal of discussion among the councillors and commissioners in provincial towns about the burden on the rate-payers and the ongoing challenge of rent arrears.

Connell has noted regular requests by tenants in Meath's towns to have their rents reduced, which reflected underlying problems of poverty and unemployment affecting many families. Furthermore, he points out that ‘the higher rents tenants of new Council houses were obliged to pay had the effect of reducing their disposable incomes’.Footnote 46 A local councillor in the Trim area reported in 1934 that the rents of the newly built houses were not within the means of the tenants, and that in some large families the people were on the brink of starvation. Similar concerns were voiced across the country. For example, at a housing inquiry in Cavan town in June 1936, councillor John Muldoon argued that ‘the workers could not pay the rents that local authorities were compelled to fix under the housing schemes’, while councillor John Moore stated ‘we cannot have cheap houses unless we get cheap loans’.Footnote 47

Across the country, the various local authorities attempted to balance affordability with quality, while also avoiding an extreme burden on the local rates, with varying degrees of success. In a 1934 discussion about the fixing of rents for new houses in Mountmellick, Co. Laois, the Westmeath Examiner reported that the weekly rent of a two-storey stone cottage was reduced from the initial proposal of 3s 6d down to 3s, as it was felt that tenants from the clearance areas would not be able to pay the higher rent.Footnote 48 In Nenagh, too, a gradual transition is evident as these aspects were weighed up. Discussions in 1919 had focused on the provision of high-quality houses with a substantial amount of ground around each one. By the time that the Stafford Street scheme was in preparation in 1927, the council preferred a smaller house size, so that prospective tenants would be capable of paying the rent.Footnote 49

Tensions between the different agendas of local landlords and council members often played out in local housing policies (as seen above in Newbridge). Although appalling conditions in Ballinasloe, Co. Galway, had been highlighted as early as 1922 and 1923, with controversial proposals to use the old workhouse for housing, progress was slow.Footnote 50 A housing inspection in 1936 by two medical officers and the town surveyor noted that in St Michael's Square in the heart of the town ‘there were houses with only two rooms, in which there were ten members of a family’. In many cases, these houses were below ground level, dark, insanitary and congested. Others in laneways were also declared insanitary and unhealthy.Footnote 51 A year later, despite ongoing efforts, the medical officer could still report of dwellings which were ‘deficient of everything that went to make a healthy house’.Footnote 52 However, there were objections to proposed clearances from landlords who claimed that the dwellings were capable of being made sanitary and that the council had not given them the opportunity to do so. Furthermore, Mr Hutchinson Davidson, solicitor acting for the estate agents, stated that the council had a scheme which was occupied but which had no running water and only dry closets for the past five years. This was admitted by the council, explaining that it was impossible to put in proper water supply or sewerage as the sewers were a mile from the site. Davidson argued that the council should ‘put their own houses in order’ before closing others.Footnote 53

Ballina: ‘a model town’

Ballina, Co. Mayo, a market town with a large agricultural hinterland, had one of the most active UDCs with regard to housing (Figure 3a). Their work was reported on in both local and national press and their experience gives a flavour of the type of discussions which were underway nationwide. In 1933, the chairman of Ballina UDC noted that the housing drive would mean that Ballina would be ‘a model town so far as housing is concerned’.Footnote 54 He described the scheme as being the largest put forward by any urban council in the Free State. At that time, 500 cottages were about to be completed, while the overall population of the town was about 5,000.

Figure 3a: Location map of Ballina, Co. Mayo

The nature and location of slums, and how best to replace them, were common discussion points at council meetings across Ireland. In 1932, Ballina's town surveyor, George Joynt, reported that there were ‘264 houses (or rather structures, for many cannot be designated as houses) which come under the condemnatory scale as unfit for human habitation, and 154 which are more or less capable of being improved, so as to render them habitable’.Footnote 55 He further noted that it was difficult at times to distinguish between the categories, and that ‘in many cases it would be just as cheap, and far more satisfactory, to rebuild as to renovate or reconstruct’. These unfit dwellings were scattered all over the town. In the course of the discussion, the town surveyor considered it better to rebuild on old sites, whereas Councillor Seán Maguire argued in favour of building on new ground. Mrs Teresa Beckett, who was one of the largest rate-payers in Ballina as well as its first female councillor, held that demolition of ‘the old shacks’ and replacing them with ‘decent houses’ was necessary to improve the appearance of the town.Footnote 56

There was also a discussion of the need to concentrate on building houses that would be let at low rents of 2s or 2s 6d a week. The concentration on building 60 or 100 one-storey houses and clearing out the lanes was recommended, although the question of one-storey houses caused some dispute. While Thomas Ruane felt that this would be a helpful starting point, one council member (John J. Kilgallon, who represented Ardnaree where it was proposed to locate the smaller dwellings) said ‘they could not build one storey in Ardnaree and larger elsewhere. They would make a laughing stock of it.’Footnote 57 Such arguments around the dangers of building low-cost, low-quality housing which would become slums in future years were echoed on the national stage. Indeed, the Citizens’ Housing Council suggested that ‘it is highly probable that future generations will stigmatize, and not praise, the results of our best endeavours to house the workers’.Footnote 58

The question of ability to pay was raised long before the schemes were begun. In one discussion about sites in Ballina, the council members noted that a lot of the people ‘living in the lanes’ (generally a euphemism for slums) were only paying 1s to 1s 6d per week in rent and would find it difficult to come up with a higher rent. Mr Clarke, a Labour councillor, stated that ‘there were people living in the lanes – old age pensioners and people in receipt of St. Vincent de Paul Society money – who could not pay 2/6 or 3/- a week’.Footnote 59 The St Vincent de Paul Society, active in Ireland since 1844, is a large voluntary charitable organization. At this time, its focus on a practical approach to poverty, including family visitation, gave it a vital importance to the socio-economic structure of Irish towns. The public health arguments for slum clearance, however, failed to recognize the underlying causes of poverty which would not be resolved simply by provision of a modern dwelling.

There was opposition to the clearances from landlords, particularly those who felt that they had not been given the opportunity to improve dwellings before they were condemned. This is not entirely surprising, given that the legislation may have encouraged certain interpretations. In Ballina, Thomas Ruane noted that if a house was condemned under the act, then the council would only be required to pay for the site, which would have been an incentive to condemn ‘borderline’ dwellings and would have caused great concern for the landlords who would have lost out on potentially lucrative compensation. Slum clearances were not just opposed by landlords, on occasion tenants in Irish towns refused to move, despite the new and improved dwellings on offer. Inability to pay, as well as attachment to place, often explained the refusals of slum dwellers to leave their homes for improved housing elsewhere. In the case of Ballinasloe, old houses which had been cleared were almost immediately reoccupied by other tenants from congested lanes.Footnote 60 As landlords were complying with orders to clear and demolish unfit properties under the act, the families displaced by these notices to quit were relocating to other slums in the town. A similar phenomenon had been described in nineteenth-century slum clearances in both London and Dublin, and the same process was operating in miniature in these smaller urban areas.Footnote 61

Building programmes were seen as a way of dealing with high levels of unemployment. It is not surprising therefore that issues arose around who was being employed on the schemes, a matter raised at various UDC meetings around the country. In 1933, the Ballina council passed a resolution to refuse work on the Upper Mill Street housing scheme to men who had not been resident in the urban area for the previous two years. Labour councillor Christy Carroll stated that this resolution would ‘prevent people coming in from outside areas, getting into the Union, and securing work on the scheme under any old subterfuge’.Footnote 62 In the same year, councillors debated the merits of avoiding the use of machinery such as motor lorries and cement mixers on the construction of the schemes, in order to ‘give a chance to the unemployed labouring men’.Footnote 63 Table 1 and Figure 3b provide details of house completions by Ballina UDC from its first scheme in 1916 to 1933, revealing the range in the number and types of dwellings and size of schemes. In total, up to the end of March 1934, 111 cottages had been built by Ballina UDC and let to tenants. By December of that year, a further 116 cottages had been completed, made up of 96 four-roomed cottages for rehousing slum dwellers and 20 five-roomed cottages for non-slum dwellers. There were also 102 cottages in course of construction at three sites: Ardnaree, 50 three-roomed; Circular Road, 44 four-roomed; Howley Terrace, 8 five-roomed cottages. Clearly, the 8 five-roomed cottages were intended for a different class of tenant to the 94 three- and four-roomed cottages intended to rehouse tenants occupying slum dwellings. Overall, the mid-1930s saw a significant increase in the rate of building but also, as in Dublin, a decrease in the size of dwellings. The three-roomed cottages, while cheap, had the potential to become future slums. It is also noteworthy that each of the sites seems to have had housing of only one type, rather than a mixture of dwellings.

Table 1: Dwellings completed by Ballina UDC between 1916 and 1933

Source: Connaught Telegraph, 8 Dec. 1934.

Figure 3b: Location map of Ballina UDC housing schemes to 1940

Although the council cottages were often built in small groups and terraces, the larger-scale slum clearance schemes of the 1930s generally resulted in distinctive additions of one-class housing, typically on the outskirts of the provincial towns. In Tuam, Co. Galway, the scheme of 90 houses at Tubberjarlath was ‘a massive undertaking [which] changed the face and image of the town’ after it was opened by Seán T. O'Kelly, minister for local government, in October 1936.Footnote 64 In all, some 160 slum clearance homes were completed at the edge of the town, leading to the development of what became known locally as ‘the village’, and as ‘a vibrant and supportive community’.Footnote 65 The location of schemes depended on the availability of land suitable for building and sometimes complex negotiations with owners. The use of sites which had been in public ownership is a topic which warrants further study. In the case of Ballina, the largest and most spatially discrete scheme was erected adjacent to the site of the former workhouse. The main frontage is onto Lord Edward Street, formerly Workhouse Road. The solid two-storey, semi-detached houses with small front gardens are built of mass concrete and Irish slates, and laid out in the characteristic local authority garden suburb style. Like the Tubberjarlath scheme in Tuam, the houses used local authority plan ‘type 69’, and thus are almost identical in appearance to those in Tuam.Footnote 66

Ballina's final, and largest, scheme of 176 cottages was completed at Tirawley (or Tyrawley) Park in 1938.Footnote 67 Typically glowing newspaper reports described the ‘simple but impressive ceremony’ which took place in April of that year, when local parish priest, administrator and vicar forane of St Muredach's Cathedral, D. O'Connor, solemnly blessed the 176 new cottages: ‘It was a fitting finish to one of the largest housing schemes ever undertaken in an urban district. The site of the new houses was once 20 acres of grazing ground. Today, colourful homes stand upon it and it presents an animated appearance on a height adjacent to the new district hospital.’Footnote 68 The laudatory tone of this report was reflected across the country when the completion of large housing schemes was reported on with overwhelmingly positive rhetoric.Footnote 69

However, the reality was not always as utopian as these rosy descriptions might suggest. Tirawley Park was not without its share of teething problems and more generally, as will be shown, Ballina's housing activism came at a cost. In April 1938, one new tenant left after a week, complaining that his house was haunted (a councillor quipped that the only ghost was the rent collector). However, the same council meeting heard that a further three tenants had refused to take up the dwellings which they had been allocated.Footnote 70 As late as August 1938 about a dozen families were refusing to leave condemned dwellings, while some 28 cottages were vacant at Tirawley Park.Footnote 71 A letter received by the council on behalf of 228 tenants at Tirawley Park and neighbouring Lord Edward Street also pointed to a significant problem with ability to pay. It was a familiar predicament. The people who most needed decent housing could not afford to pay for it. Tirawley was at risk of becoming a ghetto of the unemployed; 160 of the 228 tenants were receiving unemployment assistance of between 6s and 14s weekly, while paying 5s weekly in rent and rates. Many tenants were finding it difficult to ‘provide themselves and their families with the ordinary necessaries of life’.Footnote 72

Ballina UDC had built more houses than any other urban council, owning almost half of the houses in the town by 1938.Footnote 73 The Tuam Herald declared that ‘every working class family in Ballina is now provided with fine sanitary dwellings with gardens attached’.Footnote 74 While this might be seen as laudable, the financial impact was devastating, a fact highlighted in early 1939, when a new housing bill was being debated in the Dáil.Footnote 75 Richard Mulcahy, opposition Fine Gael TD for Dublin North-East, used Ballina as one of his examples. Ballina's population in 1926 was 4,873 with 914 inhabited houses, and the population increased to 5,674 by 1936. In Ballina, the local authority had built 465 houses whereas 94 had been completed by private persons. Mulcahy's contention was that there was a significant burden on local authorities due to the amount of money being invested in housing. In Ballina, there was an increase of £91,535 in loans for housing over the 1924 figure and the town rate had increased from 12s 6d to 18s 11d. His argument was that it would be unwise to withdraw grants from private persons under the revised housing act as this would have, in Mulcahy's view, a detrimental effect. Even with the existing situation, where grants were available to private individuals, a great burden was falling on urban authorities as a result of this large building of houses. He felt that this burden would be further increased if the grants to private persons were stopped.

Conclusion

Through its various initiatives, the state was involved in the provision of over 120,000 dwellings from 1923 to 1940 (see Figure 1).Footnote 76 Around 33,000 dwellings were provided in 88 urban areas between 1932 and 1939, of which more than two-thirds (23,142) were built by the local authorities.Footnote 77 When compared with the 1926 census baseline for inhabited houses in each of these provincial towns, these new houses account for an addition of more than one quarter (26.4 per cent) to the existing housing stock. Despite Power's observations, by any stretch of the imagination this is a substantial contribution which had a very tangible impact.

Comparing the data for 1940 with the number of inhabited dwellings in each of the urban areas according to the 1926 census, the importance of the housing drive becomes clear. Two towns in the west of Ireland, Tuam and Ballina, saw the greatest proportional increase of their housing stock. In Tuam, the 343 house completions under the act accounted for 60 per cent of the inhabited dwellings in the town in 1926. The increased housing stock reflected the boost to the economy and population of the town experienced with the opening of the sugar beet factory there in 1933.Footnote 78 In Ballina, 514 dwellings were added to the 914 inhabited dwellings listed in 1926 (56.2 per cent). In the next tier, Thurles (42.5 per cent), Athlone (35 per cent), Bray (33.1 per cent) and Castlebar (32.9 per cent) added over one third to their existing housing stock. Figure 2 shows an important reduction in overcrowding between 1926 and 1936 when mapped using the same criteria. P.J. Meghen considered that the housing programme was, on the whole, very successful, while acknowledging criticisms that too great an emphasis was laid on economy in building costs and probably more variety was needed in accommodation.Footnote 79 Nevertheless, over 11,000 condemned houses were demolished by local authorities, and a considerable number of private houses were also replaced, resulting in considerable health benefits which are difficult to measure.

The achievement of this massive building programme by the nascent state must be recognized. However, the picture is nuanced and statistics alone can only tell so much. The quality of dwellings and of new residential environments was variable, as is reflected in their present-day status. The voice of the new tenants is largely absent from the record. Did they enjoy the new amenities or miss the sense of community? To what degree, if any, did they feel stigmatized by their type of residence? Many further histories remain to be uncovered. Rather than being a period of limbo, this was a deeply significant era which left a permanent mark on policy, on streetscapes and on people's lives.