Introduction

Recent decades have witnessed a remarkable rise in precarious, non-standard employment (Kalleberg Reference Kalleberg2000; ILO 2015). A notable example is ‘multiparty employment arrangements’, or temporary agency work (TAW), where workers are supplied via contracts between multiple parties and are not directly employed by the firms for which they perform work (ILO 2015). Research on such arrangements has centred around the agency–worker–client triangle, where a single third party recruits, deploys, and pays workers (Bidwell and Fernandez-Mateo Reference Bidwell and Fernandez-Mateo2008). However, recent studies indicate that some process of labour supply resembles a supply chain beyond the traditional triangle, reflecting new employment changes and breeding grounds for exploitation (Allain et al Reference Allain, Crane, LeBaron and Behbahani2013; Barrientos Reference Barrientos2013; Gordon Reference Gordon2016; Liu and Zhu Reference Liu and Zhu2020).

In this article, the term ‘cascading employment’ is introduced to describe employment arrangements where the employer (an agency) arranges for a worker’s placement in a workplace (a client) through a sequence of third parties, but where the employer has no direct contractual or business relationship with the client. Cascading employment remains inadequately conceptualised in the literature. Relevant research mainly focuses on the client–agency–worker triangle, and discussion on employment arrangements with more actors involved is scarce. While there are studies on extended labour supply subcontracting chains, they typically adopt a business model lens, focusing on unethical and illicit subcontracting practices. However, they often fail to recognise these chains as a distinctive and ‘normalised’ form of employment. Moreover, the fact that cascading employment operates on a continuum is often overlooked by researchers, who mainly concentrate on the top or bottom of the chain.

Drawing on Vosko’s (Reference Vosko2011) schema for identifying precarious employment and data from US-based IT workers in cascading employment, the argument is made that cascading employment is a paradigmatic form of precarious employment, distinct from its triangular counterpart. Findings show that cascading employment’s distinct dimensions – multilayeredness, hierarchical fissuring, and relationship heterogeneity – separate it from triangular employment and significantly contribute to employment precariousness. These dimensions challenge traditional determinants of employment precariousness, which often focus on contract type, employment status, and social context. Therefore, in this article, it is argued that the ‘complexity of employment arrangements’ is an important and heretofore largely neglected determinant of employment precariousness. ‘Complexity’ can be measured by indicators such as the number of actors involved, fissuring in employer costs and responsibilities, and the diversity of inter-actor relationships.

Background

In recent decades, the nature and structure of employment have shifted dramatically, largely due to the rise of information technology, globalisation, neoliberal economic policies, and economic restructuring. Vertical-hierarchical organisations have gradually given way to more decentralised and flexible networks (Castells Reference Castells1996). This shift, particularly evident in the IT sector, has resulted in firms increasingly relying on temporary, contract, and part-time workers for the purpose of maintaining flexibility in response to technological advancements and market fluctuations (Benner Reference Benner2002). Labour market intermediaries, such as temporary help agencies, professional organisations, and workforce development agencies, have become key players in facilitating this labour flexibility, particularly in the IT industry (Benner Reference Benner2002; Smith and Neuwirth Reference Smith and Neuwirth2008; Smith and Neuwirth Reference Smith and Neuwirth2009). A central mode through which these intermediaries operate is the multiparty employment arrangements, in which ‘when workers are not directly employed by the company to which they provide their services’ (ILO 2015). A multiparty employment arrangement is often understood as ‘triangular employment’, characterised by a client–agency–worker relationship, where the workers’ formal contracts are with the agencies rather than with the firms they provide services to (Bidwell and Fernandez-Mateo Reference Bidwell and Fernandez-Mateo2008; Gonos Reference Gonos1997). This model grew in popularity in the 1980s as businesses sought to further downsize and avoid employee (mis)classification issues.

However, recent multiparty employment arrangements have been characterised by further complexities, including the participation of new actors, the diversification of labour market intermediaries’ functions, and the growing polarisation of the staffing industry. In the industry’s higher echelons, vendor management organisations (VMOs) became prominent in the 1990s, breaking the direct link between clients and temporary agencies by acting as facilitators and gatekeepers (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2018). Large companies often outsource their staffing management to these VMOs, who manage the approved vendor list and limit authorised access to a few global labour market intermediaries (GLMI) (Cárdenas Tomažič Reference Cárdenas Tomažič2022). These GLMIs have accumulated enough economic and cultural capital to hold the ‘classification power’ to redivide the workforce (Cárdenas Tomažič Reference Cárdenas Tomažič2022). Meanwhile, the industry’s lower echelon saw the rise of small, marginal ‘backstreet’ agencies that operate with thin profit margins (Peck and Theodore Reference Peck and Theodore1998), and which are documented sporadically in the literature as body shops (Ontiveros Reference Ontiveros2017; Xiang Reference Xiang2007), labour contractors (Barrientos Reference Barrientos2013), recruitment agents (Stringer et al Reference Stringer, Kartikasari and Michailova2021), and the like. These agencies lack direct access to large companies’ orders and depend on upper-tier intermediaries. The restructuring of the ‘top’ and ‘bottom’ in the staffing industry has gradually weakened or even severed client firms’ direct connection with many workers’ employers, making once close relationships weak or even nonexistent.

Defining ‘cascading employment’ and gaps

In this article, ‘cascading employment’ is narrowly defined to include the employment practices involved in labour supply outsourcing and subcontracting, not those associated with production outsourcing and subcontracting. Despite often being used interchangeably, production and labour supply outsourcing are two different processes. While production outsourcing involves delegating a process or an entire production line to a third party, labour supply outsourcing recruits flexible, just-in-time, and cost-effective labour to fill non-core positions that would otherwise have been handled by in-house employees (e.g. IT, human resources, janitorial services, etc.) (Allain et al Reference Allain, Crane, LeBaron and Behbahani2013; Gordon Reference Gordon2015; LeBaron Reference LeBaron2014). Admittedly, labour supply and production outsourcing may intersect, as labour supply outsourcing can arise at any production outsourcing stage (Gordon Reference Gordon2015, Reference Gordon2016). Actors involved in labour supply outsourcing (different types of labour market intermediaries) arrange a worker’s employment more directly than actors involved in production outsourcing (manufacturers, distributors, and retailers).

Despite being under-conceptualised, cascading employment is not a new phenomenon. Indeed it has been documented in studies on extended labour supply outsourcing and subcontracting across various countries and industries – such as the IT sector in Australia (Xiang Reference Xiang2007), horticulture in South Africa and the UK (Barrientos Reference Barrientos2013), fisheries in Singapore (Wise Reference Wise2013), and manufacturing in China (Liu and Zhu Reference Liu and Zhu2020). Together, these studies shed light on the chainisation of labour supply and how this chainisation creates the potential complexity of employment relations and the wherewithal for exploitation. The term for such extended labour supply outsourcing varies, with ‘chain’ often used, as seen in terms like ‘labour chain’ (Allain et al Reference Allain, Crane, LeBaron and Behbahani2013), ‘human supply chain’ (Gordon Reference Gordon2016), ‘agency chain’ (Xiang Reference Xiang2007), and ‘intermediary chain’ (Liu and Zhu Reference Liu and Zhu2020). However, ‘chain’ can oversimplify complex arrangements by implying a linear process. Echoing Barrientos’ ‘cascade system’, I use ‘cascade’ to capture the non-linear nature of employment arrangements involved in labour supply, as they do not simply follow a single path or direction but can unfold through multiple channels.

Knowledge and conceptualisation gaps remain. First, cascading employment remains under-conceptualised and often conflated with or equated to ‘triangular employment’, TAW, or employment in production outsourcing. The danger of this is mistaking vendors in a cascade for ‘clients’ in triangular employment or overlooking a sequence of pass-through vendors between client and employer. Both prevent a complete understanding of worker employment in cascading employment. Second, there is insufficient analysis of cascading employment from an employment perspective in the literature. Most scholars have analysed extended labour supply from a ‘business model’ perspective, which is organisation-centric, focusing on ‘the rationale of how an organisation creates, delivers, and captures value’ (Osterwalder and Pigneur Reference Osterwalder and Pigneur2010). However, less common is an employment perspective, which is worker-centric and focuses on how employment is organised, governed, and experienced. Third, research on cascading employment, though growing, often shows polarised focuses. Some research investigates the effects of powerful actors at the higher echelon, such as VMOs and GLMIs, which shape the market and regulatory landscape (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2018; Rho Reference Rho2018; Cárdenas Tomažič Reference Cárdenas Tomažič2022), while other research has examined informal or unregistered labour contractors at the lower echelon who often operate cross-border and engage in exploitative employment practices (Barrientos Reference Barrientos2013; Stringer et al Reference Stringer, Kartikasari and Michailova2021). These studies provide valuable empirical evidence and emphasise cascading employment’s prevalence, complexity, and potential for exploitation. However, they fail to represent cascading arrangements as a continuum, where the upper and lower echelons are closely connected, even when placing a single worker. Also, the large focus on the extremely exploitative aspects fails to view cascading employment as a ‘normalised’ employment form, thus overlooking the fact that exploitation is often embedded and normalised within legitimate practices (Davies Reference Davies2019). In this paper, I adopt the same position as Gordon (Reference Gordon2016), who argues that cascading arrangements (which she called a ‘human supply chain’) are not merely generated by ‘anomalous bad actors’ but are embedded in legitimate business practices. Therefore, the analysis must shift from viewing cascading employment as a peripheral business model to recognising and conceptualising it as a ‘normalised’ and distinct employment type. Similarly, instead of isolating tiers for analysis, we should view cascading employment as a continuum and study upper and lower tiers as distinct segments of one chain to understand each actor’s impact on work conditions. Key questions arise: What dimensions of cascading employment distinguish it from more commonly understood forms of employment, such as triangular employment? How do these dimensions impact employment conditions?

Conceptual framework: precarious employment

The conceptual framework of precarious work is well-suited for analysing cascading employment due to its focus on the causes and consequences of non-standard employment forms across multiple levels. Precarious work, defined as ‘uncertain, unstable, and insecure employment where employees bear the risks and receive limited social benefits and statutory protections’ (Kalleberg and Vallas Reference Kalleberg and Vallas2017), offers a robust framework for analysing employment changes and their consequences for workers. Precariousness spans five categories: employment, work, workers, precariat, and precarity (Campbell and Price Reference Campbell and Price2016). Among these, employment precariousness is fundamental, as ‘objective job dimensions’ play a crucial role in framing labour practices and determining legal protections. Employment precariousness is primarily characterised by a low degree of job security, regulatory ineffectiveness, workers’ low control over the labour process (including working conditions, wages, and work intensity), and the inadequacy of the income package (Campbell and Price 2016; Vosko Reference Vosko2011). Applying these criteria to cascading employment, we can identify it as a form of precarious employment and evaluate how workers endure the consequences of precariousness.

Efforts have been made to identify factors shaping employment precariousness. Some of the factors that have previously been identified include employment status (paid/self-employed), contract type (permanent/temporary; full-time/part-time), social context (occupation, industry, geography), and social locations (gender, legal status). These factors can be seen as falling into two categories: employment factors (employment status and contract type) and worker factors (social context and social location). However, current conceptualisations of the employment factors inadequately explain cascading employment’s precariousness. Cascading employment is paid employment; most of the time, workers sign ‘full-time’ (being contracted to work 40 hours per week) and ‘permanent’ (open-ended and long-term) contracts with their employers, and cascading employment often exists in high-paying occupations such as IT, which are often understood as ‘good’ jobs. Therefore, to comprehensively understand the precariousness inherent in cascading employment, it is essential to go beyond traditional measures.

The theoretical perspectives of ‘employment fissuring’ (Weil Reference Weil2011) and ‘fragmenting work’ (Grimshaw et al Reference Grimshaw, Rubery, Cooke and Hebson2023) are instrumental in highlighting three major changes in current employment: the greater diversity of actors influencing employment; the redistribution of responsibilities and costs from a single employer to multiple firms; and the impact of inter-firm relationships on work organisation and employment conditions. They both advocate bringing ‘complexity’ into employment relations analysis. Brandl et al (Reference Brandl, Larsson, Lehr and Molina2022) attribute the ‘complexity of labour relations’ to the number of actors involved, their roles, and the form and quality of their interactions. However, current theoretical frameworks regarding precarious employment fail to fully capture such complexity. Current conceptualisations of precarious employment span the micro (worker agency and experience) and macro (social and political structures) levels, but barely cover the meso level (inter-party relationships), which is especially important for understanding cascading employment.

The study presented herein applies and extends the concept of precarious employment in two ways. First, the definitional framework is applied to ‘cascading employment’, arguing that it is a prominent form of precarious employment and different from ‘triangular employment’. This conceptualisation serves as a foundation for future research on how workers’ social locations intersect with cascading employment. Second, drawing from Brandl et al’s (Reference Brandl, Larsson, Lehr and Molina2022) view of the ‘complexity of labour relations’, and identifying cascading employment dimensions through an ‘active categorisation process’ (Grodal et al Reference Grodal, Anteby and Holm2021), this paper expands on the current understanding of the factors that shape employment precariousness. It is suggested that ‘complexity of employment arrangements’ be added as a new criterion for assessing factors shaping employment precariousness. This criterion includes the number of involved actors, the fissuring of cost and responsibility, and the heterogeneity of relationships.

Case studies: IT workers within cascading employment in the United States

In this paper, I seek to conceptualise cascading employment using the example of cascading employment in IT occupations in the United States. Over 43 million workers are engaged in multiparty employment arrangements globally, with the United States hosting the largest share (ILO 2015). The United States has a huge market size in staffing, with around 25,000 staffing and recruiting firms operating out of nearly 49,000 offices; notably, 56% of these firms are dedicated to providing temporary and contract staffing solutions (American Staffing Association (ASA) 2023). Moreover, the US ranks as the largest global market for temporary IT staffing, with nearly 13% of temporary workers serving in the engineering and IT sectors (ASA 2023). IT is a sector in which cascading employment is increasingly prevalent. With its extensive reliance on staffing agencies, its inherently flexible and project-based nature, and the prevalence of flexible employment practices within the industry (Benner, Reference Benner2002), the IT industry provides a fertile ground for studying cascading employment arrangements. ‘Workers supplied by contract firms accounted for 0.6% of total US employment, with almost half (43.1%) holding advanced degrees and many (35.1%) occupying professional roles in IT in 2017 (Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) 2017). Temporary IT workers employed through staffing firms have been found to outnumber full-time permanent staff in certain tech companies (Desario et al Reference Desario, Gwin and Padin2021). Prior research has often focused on ‘low-skill’ and ‘low-paying’ industries, with less attention to ‘high-skill’ and ‘high-paying’ sectors presumed to offer ‘good jobs’. This oversight misses the precariousness within a workforce often seen as privileged. Therefore, in this paper, I aim to deepen our understanding of cascading employment by primarily focusing on cascading employment in a ‘high-skilled’ and ‘high-paying’ sector.

Methods

In this study, in-depth interviews with workers and stakeholders engaging in multi-party employment arrangements in the United States were conducted. Participants had experience with cascading employment, enabling them to offer detailed narratives on the actors involved, their roles, and their interactions. Since this study focused on the hard-to-reach, or ‘hidden’ populations, non-probability sampling was appropriate. Purposive and subsequent snowball sampling methods were employed to recruit participants. Purposive sampling ensured the selection of participants with knowledge and experience with cascading employment. Selection criteria included experience in cascading (beyond triangular) employment arrangements and readiness to share experiences with such employment. After initial recruitment, snowball sampling enabled quick sample expansion and access to hard-to-reach individuals. Participants were asked to refer others in their network meeting the study’s requirements.

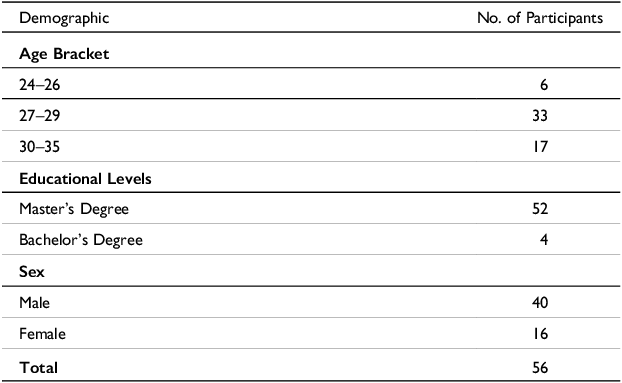

From June 2022 to August 2023, interviews were conducted with workers who were or remained employed by agencies and placed through multiple intermediaries to a client’s workplace. To exclude the confounding factors of ‘employment status’ and ‘contract types’ that may explain the employment precariousness, a subset of samples of paid employees who signed W-2 contracts with open-ended terms with their employers (N = 56) were selected. The interviews also involved nine stakeholders, including two CEOs of upper-tier vendors, three owners of small temporary agencies, and four marketing staff from the small agencies. The sample of 65 participants was deemed sufficient based on the fact that saturation (i.e., the point at which no new themes emerged in qualitative analysis) was achieved, and the information was repetitive enough to reinforce the research assumptions. Participants’ demographics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Worker participant demographics overview

Participants were connected and recruited online via web-based communities such as Reddit, Blind, and 1Point3Acre, with advertisements posted and direct message invitations sent. These platforms, focusing on career development or featuring career themes, particularly in tech, proved ideal for finding targeted participants. The interviewed employees were employed by agencies mainly in metropolitan areas such as New York-Newark-Jersey City, San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, and Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, though their placements spanned the US. Geographic locations and privacy concerns led to most interviews happening via video or phone, with some in person. Participants, were mostly aged 24 to 35, had a master’s degree and worked in IT-related occupations. Participants varied in their time in cascading employment arrangements from 0.25 to 36 months, with two-thirds still in such arrangements. They worked in the IT departments of various industries, including health care, finance, retail, supermarkets, e-commerce, and software. The most common job titles were Java Developer, .Net Developer, Front-End Developer, and Full-Stack Developer.

Thematic analysis was the primary analytical method. All transcripts were inputted into NVivo 12, a qualitative analysis tool, to streamline data organisation and simplify the coding and recoding processes. To evaluate whether cascading employment fits within precarious employment. To highlight cascading employment’s distinct dimensions compared to other forms of triangular employment, I followed Grodahl et al’s (Reference Grodal, Anteby and Holm2021) active categorisation process, which involved three stages: creating initial categories, refining tentative categories, and finalising categories, treating data analysis as an iterative ‘live’ process. The first step involved generating initial categories by asking questions and focusing on identifying distinguishing dimensions of cascading employment and their potential effects on precariousness. Further analysis examined how these dimensions affect workers’ conditions. The process then moved to deleting, merging, and splitting categories. Finally, the categories were reanalysed and conceptually integrated. Participants were informed of the purpose of the study and assured of their anonymity. Consent forms were sent and received electronically, and participants were assured that the research process was transparent and voluntary. The project had been approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Dimensions of cascading employment

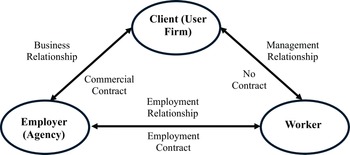

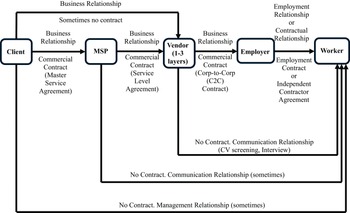

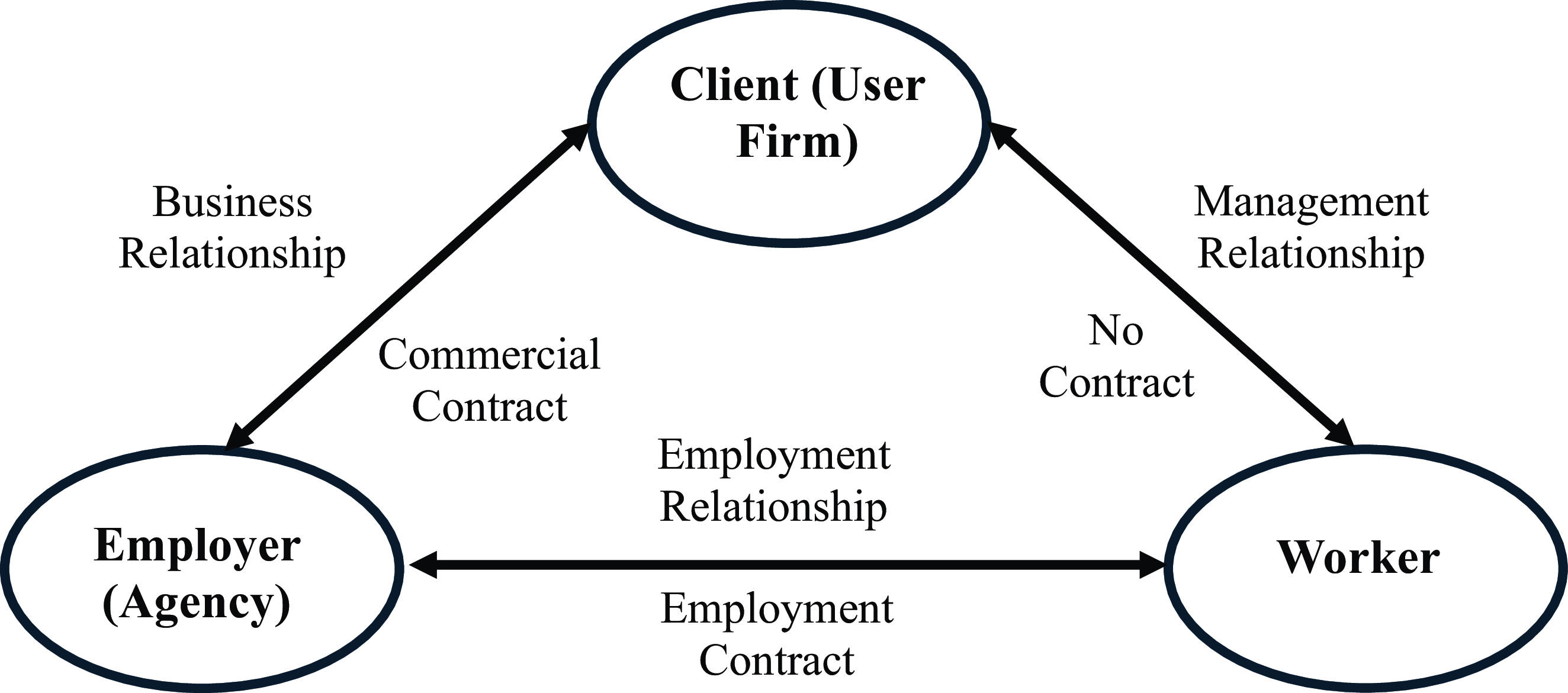

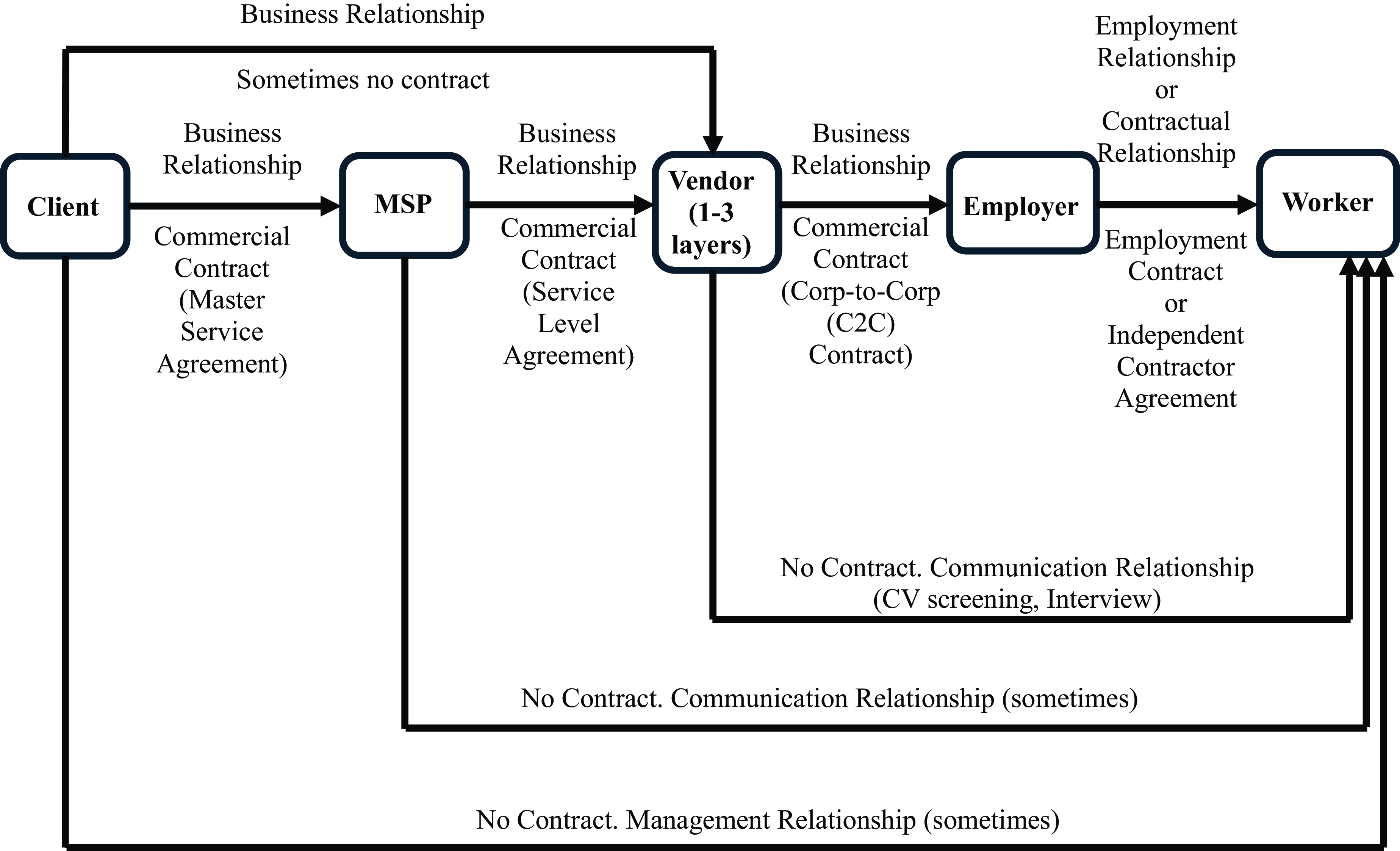

Figure 1, based on Kristina and Isidorsson (Reference Kristina and Isidorsson2015), and Figure 2, from in-depth interviews, are crucial for intuitively showing how ‘cascading employment’ is distinct from ‘triangular employment’. They delineate relationship types (business, management, employment, and communication) alongside contract forms. Figure 2 illustrates the route from client to worker via several actors (MSP, 1–3 vendors, employer). A notable difference is that, in cascading employment, the worker’s employer has no commercial contracts or business relationship with the client.

Figure 1. Triangular employment.

Figure 2. Cascading employment.

This section applies the active categorisation method to frame cascading employment and set it apart from triangular employment. I also draw on Brandl et al’s (Reference Brandl, Larsson, Lehr and Molina2022) ‘complexity of labour relations’ framework, which emphasises investigating the number of actors, their roles, and their different interactions. My analysis identifies three distinct dimensions of cascading employment: multilayeredness, hierarchical fissuring, and relationship heterogeneity.

Multi-layeredness

Multi-layeredness is the first dimension of cascading employment, with workers being placed through multiple actors. All interviewed workers reported arrangements that involved actors more than just their immediate employers or clients (their workplaces). Approximately half reported interacting with one vendor beyond their employer and client, while the other half interacted with more than one. As CW41, a frontend developer, explained his experiences:

For almost every placement, you go through multiple layers… First, there’s the agency, then there’s the vendor, then there’s the client, who’s the company you’re going to work for… Sometimes, there are even four layers. You have your employer pass you through a big agency, then to a small vendor, then to a big vendor, then to the client. (CW41, 29, Frontend Developer)

Interviewed workers commonly referred to their workplace as an ‘end client’, often a well-known large business where they worked. However, job orders from these clients do not go directly to the workers and their employers. Instead, they often first go through Managed Service Providers (MSPs), VMOs that consolidate orders, solicit bids, and sometimes pre-screen candidates. As described by the CEO of an upper-tier vendor:

The MSP handles all the hiring for [client company name] … they team up with maybe 10 or 20 staffing partners, like us… MSPs categorise partners based on what they do well…Next, they’ll talk with the [client’s] project coordinator about the specifics… If there’re ten to twenty profiles, the MSP will shortlist five or seven based on cost and quality…The MSP takes a small cut from the order, like 2 or 3%t. (AP1, 47, CEO of an upper-tier staffing firm)

Clients authorise several large staffing firms to be on a ‘preferred vendors’ list. The multi-layered process partly arises because not all vendors can become part of a client’s preferred vendor list. Large companies often maintain exclusive partnerships with select vendors, creating high entry barriers for others. According to AP1:

For vendors… it’s not easy to get on the MSP supplier shortlist for a large client. It’s pretty tough nowadays to break into this industry. You have to make the right connections, and when you’re just starting out, the barriers to entry are quite high. (AP1, 47, CEO of an upper-tier staffing firm)

Preferred vendors have first-hand large client orders, but they may not always be able to meet demands themselves. Therefore, subcontracting (with or without the client’s approval) becomes a common solution when these large staffing firms face deadlines or labour shortages (See also Allain et al Reference Allain, Crane, LeBaron and Behbahani2013; LeBaron Reference LeBaron2014). In this case, large vendors serve as the clients for the lower-tier agencies and the intermediaries between end clients and lower-tier agencies. They use their market position and client relationships to obtain orders, while utilising a multi-layered outsourcing network to complete projects. Similarly, tier 2 vendors may continue to look for tier 3 and 4 intermediaries to fulfil their orders. Further subcontracting can reach two or three additional layers beyond a single vendor. As a marketer from a lower-tier labour agency described:

When you can’t work directly with a company, you can still find ways to get business through other companies that have direct, Tier 1, or Tier 2 relationships with them. We call these connections ‘layers.’…There’s no limit to how deep these layers can go. (AP5, 28, marketing personnel in a lower-tier labour agency)

Every subcontract introducing a new layer incorporates additional actors, duties, and exchanges into a worker’s arrangement. Such multilayeredness complicates identification due to the indirect and informal connections formed through the cascade.

Hierarchical fissuring

Hierarchical fissuring is another dimension of cascading employment, where employment-associated responsibilities, costs, risks, and ‘moral relations’ (Wise Reference Wise2013) are fragmented and distributed across multiple subcontracting layers.

In triangular employment, fissuring is single-layered; the client directly offloads employment-associated costs, responsibilities, and risks to the worker’s employer, creating a straightforward line of accountability and responsibility. However, cascading employment sees these elements passed down each tier and shared between multiple parties. Each party in this hierarchy can introduce its own terms, conditions, and costs that can largely affect the workers at the bottom of the cascade.

The rationale behind the extended subcontracting of labour supply rests on the principles of ‘fissuring’ (Weil Reference Weil2011), focusing on core competencies, shedding employment, and creating and enforcing standards. Clients aim to downsize their employee headcount and concentrate on core competencies, leading to outsourcing of non-core roles’ recruitment to a preferred vendor list and vendor management to VMOs. The primary vendors’ core competency is to fill the order swiftly and cheaply. Subcontracting the job orders from the clients allows primary vendors to handle fluctuating demands and access a wider pool of specialised labour while also maintaining a leaner payroll. This process, while serving the interests of the clients and primary vendors, provides workers’ employers – often lower-tier vendors – with business opportunities they might not otherwise access, though usually at the cost of accepting tighter margins for the workers themselves.

Hierarchical fissuring implies a ‘moral distancing’, whereby the recognition of workers as fully human and deserving of respect (Wise Reference Wise2013) that close relations with workers ordinarily entail is absent. As the subcontracting chain extends, social distance increases and moral responsibility between the client and the worker diminishes (Wise Reference Wise2013). A CEO of an upper-tier staffing firm illustrates this mindset,

Big companies are leaning more towards using people as contractors nowadays. The reason is simple—if something goes wrong, they can end the contract anytime without the trouble of firing a full-time, which can be much more complicated… the company can just tell vendors like us to stop using someone, and that’s it. This saves them a lot of money and avoids all sorts of legal issues, labour disputes, or HR issues. (AP1, 47, CEO of an upper-tier staffing firm)

By framing worker recruitment in terms of ‘job orders’ rather than ‘employment contracts’, clients and upper-tier vendors distance themselves from the social and moral responsibilities that come with traditional employment. As Wise (Reference Wise2013) puts it, ‘the longer the chain, the less ‘human’ the workers become to those at the top’.

Moreover, hierarchical fissuring implies a power asymmetry among actors. Workers and smaller firms fall under the control of more powerful players and lack coordination rights (see also Paul Reference Paul2019). Interviews indicate a stark power disparity in obtaining job orders. Top-tier vendors secure direct orders through exclusive deals with large clients, while secondary subcontractors depend on upper-tier vendors to access labour demand from these companies. As a result, lower-tier vendors often receive only secondary or tertiary opportunities opportunities, as described by the owner of a small agency:

[Client company name] has positions, but they won’t give them directly to me because we’re not their preferred vendor. Even though I’ve got connections with them, and I’m even in touch with folks directly in their HR department…they won’t give the positions directly to me. They’ll definitely go to a large vendor they work with, and then that vendor contacts me because they know I have the right people ready. (AP4, 38, owner of a small agency)

This power imbalance extends to coordination and pricing. Clients have definite control over the terms of contracts, including billing rates and margins. As AP1 explained,

For large companies like [client company name], they have the final say, and while we can try to negotiate, there’s not much room. The billing rates and margins are usually set in advance in the agreement. (AP1, 47, CEO of an upper-tier staffing firm)

Similarly, when larger vendors subcontract to smaller agencies, they often set fixed prices or allow the agencies only a small margin to negotiate. As the owner of a small agency put it,

When the big vendors advertise the orders, the price is mostly fixed…Everything is pretty much decided… Of course, we can choose to reject an order if the price isn’t good, but we can’t negotiate much, so we often accept the terms if we want to keep that order. (AP2, 51, owner of a lower-tier agency)

Upstream players serve as ‘clients’ who have the authority to set overall terms, project schedules, and standards that all downstream players must follow. Consequently, lower-tier firms (and consequently their workers), wielding little bargaining power, must acquiesce to contractor terms to sustain business relations, often enduring cost reductions and shrinking profits.

Relationship heterogeneity

Relationship heterogeneity refers to the great variation in inter-firm relations and employer–worker relations patterns within the cascade. Triangular employment assumes rather straightforward relationships: the client contracts with the agency, establishing a business relationship; the worker signs an employment contract with the agency; and the client oversees the workers’ performance without directly contracting them. Cascading employment, however, adds more contractual and relational layers and removes business and contractual relationships between employer and client. Interactions at the top of the cascade are largely driven by commercial imperatives for profit and efficiency, focusing on managing risk and maximising profit through various forms of contracts that are governed by contract law. Moving down the cascade, relationships ranging from transactional to more individualised interactions are governed by labour law.

Inter-firm relations can take various forms depending on how client companies choose to structure their agreements. For instance, clients may enter into a tripartite agreement with an MSP and a preferred vendor, or they may enter a management service agreement exclusively with an MSP without direct contracts with vendors, or they may bypass the MSP entirely, contracting directly with a roster of vendors. The type of structure significantly affects the level of control and responsibility the client retains. In some cases, clients hire vendors to supply individual contract workers while maintaining direct control over the workers’ labour process (using an onsite manager from the company), with the vendor handling administrative aspects like payroll. In other cases, clients fully outsource entire departments or projects to a vendor (often referred to as an ‘implementation partner’ by interviewees) giving the vendor full operational control, even though the work is still performed at the client’s site. In this case, labour supply and production/service outsourcing intersect in one cascade. As CW47 described his experience,

Though I was working at the client’s site, my manager wasn’t the clients’ employee. He was from the big vendor company, and he handled all my leave requests, time tracking, and overtime reports. But the thing is, we’re also just contractors for the vendors. My legal employer is actually another agency. (CW47, 28, IOS developer)

This situation suggests that some workers find themselves in complex arrangements: performing tasks for one company (the client), managed by another (the supplier), legally employed by a third (the staffing agency).

Subcontracting relationships between upper-tier vendors and lower-tier vendors can vary from contractually rigid to flexibly negotiated. The upper tiers act as clients to the lower tiers and may formalise their relationship through a Corp-to-Corp (C2C) agreement, a rate confirmation, or, in some cases, operate without any formal contract. For example, as a marketer from a lower-tier labour agency noted,

We usually work with brokers to avoid adding extra tiers. We pay them a commission for helping us bring workers, but we don’t sign a contract. (AP5, 28, marketing personnel in a lower-tier labour agency)

Similarly, employer–worker relationships within cascading employment can also be varied, depending on what type of employment contract employers want to sign with the workers. Employers and workers may sign formal employment contracts or independent contractor agreements at the employer’s discretion. Employer–worker relationships are influenced by various factors, with visa status being one of the most important. This is particularly evident in how employment contracts are structured. For instance, as one recruiter explained:

H-1B workers usually have to go with a W-2 because their visa requires a full-time job contract, so they don’t have much choice there. But if you’re a green card holder or a U.S. citizen, you can go either W-2 or 1099 … the pay differs. 1099 contractors often get a higher rate because they need to handle their own taxes. (AP6, 37, marketing personnel in a lower-tier labour agency)

This differentiation in employment terms, particularly as it relates to visa status, is a clear example of what Benassi and Kornelakis (Reference Benassi and Kornelakis2021) describe as ‘institutional toying’. Employers strategically manipulate the terms of employment to align with broader cost-efficiency goals, taking advantage of the legal constraints imposed by immigration policies. For H-1B workers, the rigidity of visa requirements means they are more likely to be placed in positions where the employer retains greater control. In contrast, green card holders and U.S. citizens, who are not as tightly bound by immigration regulations, are often pushed towards independent contractor roles where the employer can benefit from reduced costs related to taxes and benefits.

Cascading employment as a form of precarious employment

Vosko’s (Reference Vosko2011) modelReference Vosko is applied with slight modifications to determine whether cascading employment qualifies as a precarious form of employment. It outlines four parameters: (a) income adequacy, (b) employment certainty, (c) worker control over work conditions, and (d) regulatory effectiveness. Through investigation of these dimensions, I argue that cascading employment is a paradigmatic form of precarious employment, which is largely different from its conflated triangular counterpart. Moreover, interview data indicate that cascading employment’s precariousness stems from its three dimensions: multilayeredness, hierarchical fissuring, and relationship heterogeneity, rather than merely the traditionally understood factors: contract type, employment status, or industry differences.

Diluted income adequacy

Income adequacy dilution was defined here as workers earning less than the industry standard or the prevailing wages. Interviewed workers can be categorised into ‘Software Developers, Quality Assurance Analysts, and Testers’, who earn an average of 124,200 USD annually across the United States in 2023 (BLS). However, the workers interviewed reported earning between 50,000 USD and 70,000 USD annually. Though seemingly ‘adequate’ compared to many other occupations, it is significantly below the average for their specific roles in the industry.

Previous research has shed some light on how wages are impacted in multi-party employment arrangements. First, the prices that clients pay to agencies are often lower than the wages of their directly hired employees (Basu et al Reference Basu, Chau and Soundararajan2019). This means that at the top of the cascade, the original billing rate for the same role is already lower than the wages of in-house employees. Additionally, the presence of MSPs between clients and vendors can lead to vendors subcontracting at reduced rates or paying their employees less (Rho Reference Rho2018). Furthermore, research on production outsourcing and subcontracting has found that an employers’ position in the subcontracting hierarchy significantly influences their employees’ wages: employees working for pure subcontractors earn considerably less than those for principal contractors (Perraudin et al Reference Perraudin, Petit, Thèvenot, Tinel and Valentin2014).

The interviews revealed that cascading employment further reduces worker earnings due to multiple-level margin deductions. This differs from triangular employment, which features more direct relationships among the client, worker, and agency, and exhibits no additional layers that dilute the original price of job orders. In cascading employment, a primary vendor might secure a high-rate order from a client, but as the order cascades down through subcontracting layers, the initially high rate diminishes, as each layer of subcontracting slices off a margin. As AP3, an owner of a staffing agency explains:

So, let’s say a client pays a preferred vendor $80 an hour for a requisition. When it gets to us, we might be looking at $60 an hour because they [preferred vendor]’ve skimmed off 30% from the top. Now, we can use workers on our payroll or hand the order off to another agency at about $50 and pocket a 20% markup ourselves.

In this scenario, when an agency, as a subcontractor of this staffing firm, pays a worker $60,000 annually, roughly $28 per hour, it captures over 70% of the markup. Moreover, when MSPs step in, they typically extract a 5% management fee from the client’s initial payment to the preferred vendor. This highlights how the multilayeredness and the hierarchical fissuring enable markup strategies across various tiers. Consequently, this leads to diminished wages for workers situated at the lowest levels of the cascade.

Furthermore, similar to production outsourcing and subcontracting, workers in cascading employment may earn different amounts based on their employers’ position in the cascade (Perraudin et al Reference Perraudin, Petit, Thèvenot, Tinel and Valentin2014). For instance, as a .Net developer shared, bypassing the employer and tier-2 vendors allows a worker to secure higher payment from the preferred vendor:

I got along well with the big vendor manager…One day, he came to me and proposed a 3-7 split to see if I wanted to work directly for them so we don’t need to go through my employer…so I learned that my employer takes at least 30% [of the vendor order price]… If you can work directly for the big vendor, you’ll see, [the wage] is not just a small increase. Many times, it can be doubled. (CW 17, 30, frontend developer)

In summary, workers in cascading employment suffer diluted wages through the layered subcontracting and markup system. This contrasts with more direct triangular employment, in which employers keep the original share of order, thus potentially increasing earnings for the worker. Findings regarding cascading employment in other industries support this (e.g. Wise Reference Wise2013).

Employment uncertainty

Employment uncertainty has two main features: earnings uncertainty, or control over future earnings, and scheduling uncertainty, or workers’ control over when and where they will work (Devereux and Wadsworth Reference Devereux and Wadsworth2021). Earnings uncertainty emerges because, as most interviewed workers reveal, earnings are usually assignment based. Client-oriented business and the fissuring of costs and responsibilities induce employers to draft contract terms that favour their interests, such as billable hours-based payment. Most workers revealed that they are paid per assignment. Consequently, they earn only when generating income for their employer, thus facing unstable earnings during idle periods. As a mobile frontend developer reported:

When there’s a gap between assignments, they[employer] don’t count that time to the 2080 work hours. Or they call it ‘billable working hours’ … They only pay when we’re on assignment…. So, when they say a year, they mean 2080 actual assignment hours, not a regular year. (CW 34, 30, Mobile Frontend Developer)

Another interviewed worker further illustrates how compensation and benefits, such as pay, leave, and relocation expenses, are also linked to whether workers are on assignment:

Almost all bonuses and compensations are tied to whether you’re on assignment. For example, they [employer] promise ten days of paid vacation, but only after completing 1040 working hours. They also promise $700 relocation expenses if our client is 50 miles away, but that’s also after 2080 working hours are completed. (CW 32, 28, Backend Developer)

Together, these narratives highlight how conditional clauses link workers’ earnings and compensation to the fluctuating availability of work assignments. This aspect of the employment arrangement, pay based on billable hours, has been found in other occupations, particularly those that are client -oriented. It is argued that billable hours have become a new labour process control mechanism related to the idea of ‘market governance’ that intensifies management control, driven by the pursuit of profit (Campbell and Charlesworth Reference Campbell and Charlesworth2012). This trend towards market governance within cascading employment heightens earnings uncertainty, deviating from traditional employment relationships that offer more stable and predictable earnings.

Though such an assignment-based payment approach can appear in triangular employment, income uncertainty in cascading employment is intensified by scheduling uncertainty, which refers to the unpredictability of securing and retaining assignments. In cascading employment, the securing of assignments is influenced by a web of decisions beyond the control of clients or workers’ direct employers. Interviewees reported undergoing multiple screenings and interviews across different levels before securing an assignment. The process typically begins with tier-2 vendors for initial resume screenings and phone interviews, advances through tier-1 vendors for technical and behavioural assessments, and culminates in final evaluations by the client. A misstep at any stage can eliminate the worker from consideration. This multistage screening, driven by cascading employment’s multilayeredness and fissuring of responsibilities, introduces extra challenges for workers as they seek assignments. Moreover, the strength of the inter-firm relations directly impacts workers’ assignment access. Solid employer–vendor relationships usually mean easier assignment access for workers, while those in agencies lacking such ties, struggle to get assignments and are often benched for a long time. As a worker reported:

There are these vendors who are tied to my employer. And they’re also close with some of the end clients. I got lucky because once you get past the vendor’s interview, the client’s interview is pretty much just for show… But I’ve heard about some places that just don’t have the connections or can’t seem to land a deal, and they end up unable to place anyone for about half a year.

Retention of assignments also largely depends on the complex web of inter-firm relations within the cascade. For instance, disruptions in these relations can cause loss of assignments. A frontend developer recounted an instance of a disrupted client–vendor relationship:

The client signs an agreement with the big vendor…this big vendor brings in contractors for the whole department at the client site… Clients can change vendors at any time. When clients change vendors, all the contractors they brought in have to go. (CW 17, 30, frontend developer)

Moreover, non-compliant inter-firm relationships within the cascade can result in workers losing assignments. For instance, when a vendor subcontracts to an unauthorised firm – a frequent practice known as covert or rogue subcontracting – employees tied to that vendor suffer consequences upon discovery. A full-stack developer recounted an incident where his primary vendor secretly subcontracted orders to smaller firms without the MSP’s approval. Exposure of this unauthorised subcontracting threatened him and his fellow contractors with termination from assignments:

I always have to tell my client I’m with Company A, the big vendor, and never mention I’m with Company R [worker’s employer]. Because if Company P [the MSP] found out, they’d immediately cut ties with A. A was doing secret business with many other smaller agencies… about two weeks ago, I heard this one contractor reveal to P that he wasn’t really from A. And then, P is so mad and wants to cut ties with A. So now, all of us working under A are in trouble. Like we’re all lined up for the chop. (CW 52, 28, Fullstack Developer)

In summary, employment uncertainty in cascading employment stems from earnings and scheduling unpredictability, heightened by conditional contract terms and the multilayered subcontracting process. Workers face unstable income due to payment models based solely on active assignments, compounded by the challenges of securing and retaining these assignments amid inter-firm relationships that are out of their control. Therefore, earnings and scheduling certainty for workers in cascading employment diminish compared to triangular employment, where direct and close client–employer relationships can imply more certain earnings and scheduling of assignments.

Low control over working conditions

Workers in cascading employment face similar limitations in controlling their day-to-day work tasks and overall job roles as workers in triangular employment arrangements. As CW57 explained,

To the client, you’re just a contractor, or really just a contractor for the vendor, so you don’t get to choose your tasks. Full-time employees can suggest their own projects and get credit for them, but as a contractor, you don’t get to propose anything. There are no performance reviews, no raises, just your fixed rate. And yeah, you’re definitely not working on anything important or core, probably because of intellectual property or something like that.(CW57, 28, data analyst)

Just like their contractor counterparts, workers in cascading employment arrangements are not allowed to choose or propose tasks, unlike full-time employees who can suggest projects and earn recognition. Additionally, contractors do not receive performance reviews or raises, and are excluded from handling core business tasks, further limiting their agency and career development opportunities. This lack of control of working conditions is further exacerbated by the multi-layered structure of employment arrangements, which includes limited ability to negotiate wages and the assignment’s duration and location.

Control over the negotiation of wages is also weakened due to extended decision-making chains and information opacity. As CW 41 noted: ‘The fewer tiers in between, the more you can argue’. Workers’ employers lack direct contractual relationships with clients and primary vendors, and workers positioned at the cascade’s end seldom interact with key decision-makers, which restricts their negotiation opportunities. This lack of control is evident in the experience shared by CW 45, who explained,

When I was assigned to this project, I didn’t get any chance to discuss my pay with the client. The rate was already decided between the upper-tier vendors and the middlemen, and I just had to accept what they offered… Sure, technically, I could turn down an order, but let’s be real. Most people won’t do that. It’s not easy to land a job, and nobody wants to sit on the bench because that means no paycheck. (CW 45, 34, software developer)

Control over assignment duration and location are similarly dictated by upstream agreements, where workers lack rights of knowledge and coordination. For example, agreements between vendors and clients can cap tenure in a role, forcing periodic reassignments. Workers thus find themselves in a perpetual cycle of adjustment. A software engineer shared his experience of being rotated between clients:

I stayed at the client’s place for about a year and a half. But, because of this agreement between the primary vendor and client, I couldn’t keep the same position for more than that time. So, what they [vendor] did was they moved me to another client company for a few months and then brought me back to our team. (CW 54, 25, Software Engineer)

In summary, while both cascading and triangular employment limit workers’ control over their tasks in the workplace, the lack of control over employment conditions – such as wages, assignment duration, and location – is more pronounced in cascading employment due to the multylayeredness, hierarchical fissuring and complex inter-firm relations that govern these arrangements.

Low regulatory effectiveness

Cascading employment relationships present challenges to regulatory effectiveness.

First, identifying cascading workforces and tracking firms’ use of such workforces is inherently difficult, and publicly available data have gaps and limitations (see also, Rho Reference Rho2018). For example, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) currently defines ‘workers provided by contract firms’ in the Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey based on whether they were contracted out last week by their employer and performed their work at the client’s worksite. While measuring this variable in this manner is sufficient to identify workers in triangular employment, it falls short of identifying workers in cascading employment, and it also fails to identify the number of vendors between the contracting firm and the client. Additionally, many of the data sources on non-standard work (e.g., BLS 2017 Contingent Worker Supplement) primarily rely on self-reporting by workers and client managers, leading to potential discrepancies between survey results and the actual situation. Workers, vendors, and clients may not be aware of the details of the employment arrangements, especially when there is hidden or rogue subcontracting. It is not uncommon for clients to have limited knowledge of all the actors involved in the worker’s placement. For example, AP1, the CEO of an upper-tier vendor, acknowledged that companies like his do not investigate the agency workers’ compensation or control the percentage retained by the agency:

We don’t ask lower-tiers how much money they make or how they divide it with their employees. That’s their business. We don’t pry into what they can offer. As long as it’s legal, that’s what matters.

Also, as CW 15 described it,

The whole system works like an onion—layer after layer. Clients usually only know about vendors. They don’t know what layer you’re on.

As a result, many workers in cascading employment are in a regulatory and data blind spot, making it difficult for them to receive effective protection.

Second, enforcing nominal labour rights in cascading employment arrangements is challenging. Workers in cascading employment relationships appear to be protected by U.S. federal and state labour laws. For example, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) establishes minimum wage and overtime pay eligibility, while the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) requires safe working conditions. The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) ensures the right to unionise and bargain collectively. However, these laws are primarily designed for direct employment, and while there are provisions for triangular employment, such as the joint-employer doctrine under the NLRA and the contractor liability clauses under the FLSA, translating these labour protections into cascading employment is not straightforward. Workers in cascading employment are often misclassified as ‘full-time employees’. In the U.S., employers are typically considered to be the entities responsible for submitting W-2 tax forms (reports of employees’ income and tax withholdings) to the federal IRS. However, this framework does not fully accommodate the complexity of cascading employment, as clients and subcontractors who benefit from workers’ labour and placement are not held accountable as employers.

Furthermore, despite current efforts to address triangular employment, there is a risk of simply identifying vendors as the ‘client’ or ‘user firm’ in the triangle rather than recognising the company that actually benefits from workers’ labour. There is also the risk of overlooking the value extraction and influence exerted by multiple intermediaries on employment. Due to incomplete data tracking and gaps in legal design, regulatory oversight of actors throughout the labour supply chain remains insufficient. This results in a lack of adequate monitoring and accountability for those involved in cascading employment arrangements. Ultimately, the worker’s direct employer (usually the lowest-tier agency) bears most of the legal responsibility, while the upper-tier clients and intermediaries that benefit from the worker’s labour often evade their share of accountability.

Conclusion and Discussion

This study has addressed an important yet under-explored topic – cascading employment, which is not new but seems to have become increasingly prevalent in the labour market due to the rise and expansion of multilayered outsourcing and subcontracting. Unlike triangular employment, in which a single labour market intermediary agency connects workers and clients (Bidwell & Fernandez-Mateo, Reference Bidwell and Fernandez-Mateo2008; Vosko, Reference Vosko2011), cascading employment involves multiple labour market intermediaries varying in scale and functions to place workers at client work sites. Its dimensions – multilayeredness, hierarchical fissuring, and relationship heterogeneity – set it apart from its more simple and straightforward counterparts. The argument here is that cascading employment is not merely an extension of triangular employment, but fundamentally introduces more precarious labour relationships. Its precariousness cannot be fully explained by traditional variables such as contract type, employment status, or industry. Instead, it must be understood through the ‘complexity of employment arrangements’, which can be measured by indicators such as the number and types of actors as well as the type of interactions involved.

One dimension of cascading employment that distinguishes it from triangular hiring is its multilayeredness. Workers are passed through multiple intermediaries – with overhead costs at each step – before reaching the client’s worksite. This results from super-subcontracting, where outsourced job orders are further split, contracted, and subcontracted, which creates a contracting cascade. Each extracts a share of the original job order, reducing the payout to workers’ employers, which in turn lowers workers’ final salaries. The multilayeredness also reduces transparency in employment negotiations and weakens workers’ agency. Additionally, the multiple intermediaries act as buffers, further distancing workers from the entities that benefit from their labour both economically and socially. The second dimension of cascading employment is hierarchical fissuring. In cascading employment, the financial, legal, and ethical obligations that should be borne by the client are fissured across multiple labour market intermediaries and eventually concentrated on the legal employer of the worker. This mirrors the conditions found in product supply chains (see Weil Reference Weil2011). This diffusion enables many actors to extract value, while only the legal employer (often a small entity operating under cost pressures, which may enforce the lowest ethical standards) assumes responsibility for worker welfare. Relationship heterogeneity is the third dimension of cascading employment. Unlike the more direct and simple relationships in triangular employment, cascading employment involves a range of contractual arrangements. At the top, agreements are governed by commercial law, while lower-tier contracts between agencies and workers fall under labour law. Informal interactions between agencies and brokers often escape legal scrutiny. The categorisation of migrant workers’ legal status further complicates matters, as lower-tier agencies exploit immigration laws to craft contract types favouring their interests (see also Liang, Reference Liang2024).

This study extends the traditional frameworks for understanding precarious employment (Vosko, Reference Vosko2011; Kalleberg and Vallas, Reference Kalleberg and Vallas2017). The findings show that standard variables such as contract type, employment status, and industry cannot adequately explain the precariousness of cascading employment, which arises not from the nature of the contract but from the complexity of employment arrangements. Therefore, relying solely on traditional metrics to assess precariousness can lead to a misrepresentation of workers in cascading employment. These workers may appear to be in stable, “good” jobs because they hold full-time (W-2) contracts, are paid employees rather than self-employed, and are employed in high-skilled, high-income sectors such as IT. However, such metrics often overlook the instability and vulnerabilities inherent in their employment arrangements. Without distinguishing these workers from others in precarious employment arrangements, they risk being wrongly grouped as full-time employees, temporary workers hired under triangular employment models, or independent contractors directly contracted by clients.

Cascading employment introduces significant challenges in understanding exploitation and regulatory oversight. On one hand, recognising only the contractual or legal employer oversimplifies the issue of exploitation by placing responsibility on the direct employer at the bottom of the cascade while ignoring the larger profits gained by several intermediate layers and the ultimate beneficiaries of the workers’ labour. If cascading employment is forced into the framework of triangular employment, the ‘client’ can be misidentified as the immediate intermediary above the employment agency rather than the higher-tier intermediaries or the end clients who actually benefit from the worker’s labour and hold more control over the employment arrangement. On the other hand, this confusion complicates legal regulation and public data tracking, as existing worker classifications – such as those for temporary help agency workers, on-call workers, contract workers, and independent contractors – cannot fit the situation of workers in cascading employment situations. Importantly, workers in cascading employment arrangements can often be misclassified as direct hires because they are employed under formal W-2 contracts. Therefore, by distinguishing cascading employment and its workers from other workers and introducing the variable of ‘employment arrangement complexity’, this study extends the framework for understanding employment precariousness.

The findings highlight the need for policy intervention. Policymakers must recognise the multilayered nature of cascading employment and create regulatory frameworks that ensure transparency and accountability across all participants in labour supply chains. This study supports Gordon’s (Reference Gordon2016) call for applying regulatory models from product supply chains, such as corporate responsibility for labour conditions, to address labour supply chains and the cascading employment relations within those chains. Product supply chain scholars emphasise the importance of implementing transparency and traceability systems to ensure that labour standards are maintained across all tiers of the supply network (see Gold et al Reference Gold, Chesney, Gruchmann and Trautrims2020). These systems require firms to monitor compliance, even beyond their direct suppliers and enable full visibility of the production processes across subcontractors and other intermediaries. By spreading sustainability standards throughout supplier–subcontractor networks, companies can make sure that everyone in the supply chain shares responsibility, resulting in more ethical practices across the board (Gold et al 2020). Similar strategies could be applied to labour supply chains to track workers from recruitment to employment, reducing the risk of exploitation. To address cascading employment, labour regulations should be put in place, such as limiting the number of intermediaries and requiring clear, transparent subcontracting practices. Introducing transparency standards would also help hold top-tier intermediaries and clients accountable.

There are several recommendations for further research. First, there is a pressing need for more empirical analyses of cascading employment. Future survey data collection should aim to operationalise the concept of “complexity of employment arrangements.” This could involve developing specific measures, such as tracking the number of intermediaries involved, identifying the various types of contracts used, and examining the relationships between different actors. Second, the results of the present study highlight the complexity of cascading employment; however, the study’s focus is limited to the employment aspect of precariousness. Further investigation of cascading employment that examines the worker aspect of precariousness is needed. It is worth noting that precarious workers’ (i.e., those in marginalised social positions) inclusion in precarious employment contributes significantly to the process of precarisation (Shin et al Reference Shin, Kalleberg and Hewison2023). Therefore, examining the role of categories of social (in)visibilisation (Cárdenas Tomažič Reference Cárdenas Tomažič2023) of workers – the structured social inequalities based on categories such as race, gender, and class – play in reinforcing systems of exploitation and control in cascading employment is crucial. The relationships involved in cascading employment are constructed within a broader socio-political context, where structural vulnerabilities often intersect with control and consent in employment relations.

Xiaochen Liang is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her research focuses on precarious work, international migration, and the intersection of legal status with employment outcomes.