It’s bad with the gangs, but worse without. An unhappy but necessary marriage.

The gangs today don’t understand why they’re fighting. They know they’re angry and willing to fight but they don’t know what they’re actually fighting for.

The Puzzle

I had been living in Nova Holanda (New Holland) for several months when Carlos, my research assistant, introduced me to Severino, a member of the local Comando Vermelho (Red Command, hereon CV) affiliated gang.Footnote 1 Severino did not raise his eyes to meet mine when we shook hands. “Hello!” I said, “It’s nice to meet you. I’m a researcher from the United States. I’m interested in …” Severino stopped me immediately with a wave of his hand. “I already know,” he said. I looked at Carlos, who shrugged. “I’ve seen you around,” Severino explained. The corner where we were standing was only a minute’s walk from my apartment. In fact, Severino had seen me nearly every day for the past few months. I, on the other hand, had never noticed Severino. He was a full head shorter than me, skinny, with light brown skin. That day, he was wearing an oversized red t-shirt, baggy athletic shorts, and a pair of what used to be white Havaiana sandals. A baseball cap with a logo I did not recognize covered his closely shaved head. Unlike most of the other gang members I saw on the streets, Severino was not carrying a gun. Despite his rather unassuming appearance, he had been in the gang for more than fifteen years over which time he had held various positions: aviãozinho (messenger), olheiro (lookout), soldado (soldier), and vapor (seller). When I met him, Severino was working directly for the gang’s gerente de crack (crack manager) as a sub-gerente (sub-manager).

Carlos walked over to a small convenience store on the corner, leaving the two of us alone. Severino was still looking out at the intersection, and I began to feel a bit uncomfortable just standing in front of him, so I turned to face the bustling traffic. After a few moments of awkward silence, I felt I needed to say something. “Shit, it’s really hot today, isn’t it?” was all I could come up with. “Very,” he replied. I decided to get straight to the point, “Do you have some time to talk?” I asked. He nodded and we went over and sat down on the curb, out of earshot of any of the passersby.

I started by reciting my oral consent script.Footnote 2 I told him that my research was focused on understanding the relationship between the gang and the community, that he did not have to answer my questions, and could stop whenever he wanted. I promised not to use his name – Severino is a pseudonym – or divulge any identifiable information about him.Footnote 3 I concluded by asking if it was alright if I took notes. “Of course,” he said, “there are no secrets here. Everyone knows everything.” I reached for my notepad, but before I could take it out he asked, “Why do you think I hang out on this corner?” I took a closer look at the intersection.

Unlike many other favelas (informal neighborhoods), Nova Holanda’s streets have a checkerboard layout because it was originally built as a temporary housing project in the early 1960s. The larger of the two roads that comprised the intersection was one of the busiest in Maré. A constant stream of cars, trucks, motorcycles, and pedestrians moved past the shops, bars, and restaurants that lined both sides of the street. The intersecting street was less busy and much narrower, barely wide enough for two cars to squeeze past one another. A small barbershop was located on the corner closest to us, just a few steps away. I spotted Carlos eating a Snickers bar and chatting with the owner of the small convenience store on the opposite corner. The other two corners were home to a beverage shop and a hardware store. This intersection did not have one of the gang’s bocas de fumo (literally, mouths of smoke), open-air drug markets where the gang sold varying quantities of marijuana, cocaine, and crack. Without a boca and no heavy gang presence, it seemed like an unremarkable intersection to me.

“I don’t know,” I admitted.

“Look around,” Severino said and motioned down the smaller street. I turned and looked where he had gestured. In the distance, I could see all the way to Avenida Brasil, Rio’s busiest highway, some 500 yards away. Then he turned and looked in the other direction. I followed his gaze. Just a couple of hundred yards away, I could see a section of the fifteen-foot concrete wall that surrounded the 22nd Battalion, an imposing police station built on the edge of Nova Holanda in 2003. I could just make out the razor wire that ran along the top of the wall, but the gun turrets and the large double doors through which the enormous, militarized vehicles would pass when the police conducted their operations were just out of sight. We then turned to look down the larger street. I saw cars and pedestrians crossing the Ponte da Amizade (Bridge of Friendship) into Parque União (Union Park), a neighboring favela controlled by another CV-allied gang. A few hundred yards in the other direction, I spotted the beginning of Baixa do Sapateiro (Cobbler’s Swamp) and Morro do Timbau (Timbau Hill) rising in the distance, two favelas controlled by a gang connected to CV’s longtime rival, Terceiro Comando Puro (Third Pure Command, hereon TCP), another prison-based faction (facção). Severino then looked at me, our eyes meeting for the first time. “You always have to pay attention to what’s going on in the community,” he said. “This is a great spot to do that.”

Over the next year and a half, I found Severino hanging out on this corner most days. He was often accompanied by an assortment of young men, some with pistols tucked into their shorts, others carried semiautomatic rifles. Severino would sometimes wave me over, and we would strike up a conversation about community events, politics, football, family, or any one of a variety of other topics. He would also tell me if anything important was happening regarding the gang or the police. Over time, I noticed that various residents approached him: an elderly man requested help buying medicine, a single mother carrying an infant asked for money for diapers, a young man wanted to know where he could find his former neighbor, and a middle-aged woman wanted to resolve a domestic dispute with her husband. Although he would not solve every problem, Severino often provided information, handed out small amounts of money, told residents who to talk to, and passed the most serious problems up the chain of command.

At first glance, Severino’s services may seem rather banal and inconsequential, but the longer I lived in Maré, the more I came to realize that his behavior was part of a broader set of gang activities and relations which included not just financial assistance but a series of more programmatic policies intended to control space, gather information, and ingratiate the gang with the local population. Severino was just one of the Nova Holanda gang’s 150 or so members, many of whom were engaged in similar activities that included monitoring the streets, enforcing a set of rules, throwing parties, offering forms of welfare, and providing access to illicit and informal economies. Together, these activities constitute what I refer to as criminalized governance, or the structures and practices through which gangs control territory and manage relations with local populations.

Criminalized governance is not uncommon in Rio de Janeiro. More than 1,000 favelas dot the city’s sprawling urban landscape. In most of these communities, social services are limited, public infrastructure only partially provided, and schools and basic utilities fail to meet the needs of the population. Police only appear to engage in aggressive militarized operations. In the absence of a reliable state presence, drug-trafficking gangs have been the dominant political authority in hundreds of these neighborhoods for more than three decades. Their governance activities have irrevocably shaped the social dynamics within these communities, determined the physical security of residents, influenced local levels of development, and even affected the functioning of Rio’s democratic institutions.

This book seeks to explain the origins, evolution, and variation in Rio de Janeiro’s criminalized governance arrangements across space and time. To do so, I seek to answer a series of interrelated questions. First, what exactly are the “structures and practices” which criminalized governance entails? What are its primary dimensions and activities? Second, why do gangs govern at all? Why would organizations that seem most interested in accumulating wealth from the drug trade, spend valuable time and resources to implement reliable systems of order, adjudicate disputes, provide welfare, or distribute gifts and other benefits to residents? Finally, I seek to explain how and why these governance practices vary. Why do some gangs rely on violence and threats to dominate local populations while others refrain from such coercive behaviors? Why do some gangs provide significant benefits to local communities while others offer little or nothing? And how and why do these practices change over time and even vary within a single gang’s turf?

These questions are enduring puzzles not just for scholars of Rio de Janeiro but also a growing swath of the global urban terrain. Most contemporary cities are wracked by poverty and inequality, sparse investment in public housing, uneven infrastructure, and inadequate social services. They are mostly governed by corrupt and inefficient political institutions and bureaucracies, ill-equipped to handle the massive waves of urbanization that continue to reshape human societies across the globe.Footnote 4 As a result, a vast multitude of slums (Davis Reference Davis2006), shantytowns (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2003), hyper-shantytowns (Auyero Reference Auyero2001), ghettos (Venkatesh Reference Venkatesh1997), and hyperghettos (Wacquant Reference Wacquant2008) have emerged on what has been termed the “urban periphery” (Leeds Reference Leeds1996) or the “urban margins” (Auyero, Bourgois, and Scheper-Hughes Reference Auyero and Fernanda Berti2015). Together, these communities are home to an estimated one billion people worldwide (UN-Habitat 2016). Gangs and their governance activities are a fact of life for many of these communities.

A growing number of scholars have begun to recognize the prevalence of criminalized governance in the contemporary world. The phenomenon is particularly prominent across Latin America and the Caribbean, where hundreds of cities have witnessed the incredible proliferation of gangs and other organized and criminalized groups (OCGs) – drug-trafficking organizations, cartels, mafias, smuggling networks, and protection rackets among others. Today, a staggering 77 to 101 million people (≈14 percent) across the region are estimated to live in areas where OCGs operate (Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Lessing, Schouela and Stecher2024). In São Paulo, Brazil, for instance, a prison gang, the Primeiro Comando da Capital (First Command of the Capital, or PCC), “sits at the heart of the governance of the urban conditions of life and death” (Denyer Willis Reference Denyer Willis2015, 9), where they have developed an alternative system of law and justice for imprisoned populations and marginalized communities (Biondi Reference Bill and Athayde2014; Feltran Reference Feltran2010b; Lessing and Denyer Willis Reference Lessing and Denyer Willis2019). In Medellín, Colombia, combos (street gangs) have developed a dizzying array of arrangements with drug cartels, paramilitaries, and insurgent groups as they vie for control of impoverished neighborhoods across the city’s periphery (Abello-Colak and Guarneros-Meza Reference Abello-Colak and Guarneros-Meza2014; Arias Reference Arias2017; Blattman et al. Reference Blattman, Duncan, Lessing and Tobón2021; Lamb Reference Lamb2010).

In Central America, gangs are abundant. Nicaraguan pandillas impose their own form of order in urban areas, creating strong neighborhood-level identities and allegiances in the process (Rodgers, Reference Rodgers2006a, Reference Rodgers2006b, Reference Rodgers2009, Reference Rodgers2017). Across the Northern Triangle countries of Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, maras dominate poor, marginalized neighborhoods in the major urban centers where they have been known to extort residents while also providing order and protection from rivals (Córdova Reference Córdova2022; Cruz Reference Cruz2010; Cruz and Rosen Reference Cruz and Rosen2024; Van Der Borgh and Savenije Reference Van Der Borgh and Savenije2015). Across urban Mexico, street and prison gangs compete and collaborate with drug cartels for the control of illicit markets while imposing various forms of order in local neighborhoods (Correa-Cabrera Reference Correa-Cabrera2017; Magaloni et al. Reference Magaloni, Franco-Vivanco and Melo2020; Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020; Wolff Reference Wolff2018).

The Caribbean has witnessed a similar expansion of gangs in recent decades. In Kingston, Jamaica, gangs linked to political parties dominate the sprawling towns surrounding the capital and are often considered de facto sovereigns while providing order and a variety of public goods to local communities (Arias Reference Arias2017; Jaffe Reference Jaffe2013, Reference Jaffe2015). In Port-au-Prince, Haiti, gangs linked to political patrons have long dominated areas of the capital, engaging in a complex mix of predation and protection (Mobekk and Street Reference Mobekk and Street2006; Olivier Reference Olivier2021; Schuberth Reference Schuberth2015). Nearly each and every island in the region contains examples of criminalized governance (Bobea Reference Bobea2013).

Governance is also an oft-noted dynamic of gangs in the United States. Across many marginalized and impoverished urban neighborhoods, gangs can provide individuals and communities some level of security amidst chaotic and volatile circumstances (Ortiz Reference Ortiz2018; Sobel and Osoba Reference Sobel and Osoba2009), occasionally even constituting the dominant local authority (Sánchez-Jankowski Reference Sánchez-Jankowski1991, Reference Sánchez-Jankowski2003; Venkatesh Reference Venkatesh1997, Reference Venkatesh2008). Prison gangs also control much of the US penitentiary system; some of these organizations have managed to extend their governance beyond the prison walls to entire illicit markets (Skarbek Reference Skarbek2014).

The phenomenon of criminalized governance is not exclusive to the Americas. In South Africa, gangs have a long history of dominating impoverished townships on the outskirts of the major urban centers (Jensen Reference Jensen2008; Kynoch Reference Kynoch1999, 2005; Lambrechts Reference Lambrechts2012; Pinnock Reference Pinnock1984, Reference Pinnock2016). Slum-based gangs in Nigeria and Kenya have linked themselves to political parties and elites through which they have managed to accumulate significant local authority (LeBas Reference LeBas2013). In India, youth gangs are known to provide order in urban slums by punishing criminals (Sen Reference Sen, Jennifer and Rodgers2014), while some have even become major players in lucrative real estate markets (Weinstein Reference Weinstein2008, Reference Weinstein2013). In Bangladesh, gangs control access to infrastructure and services, determine property rights, and distribute employment opportunities to impoverished communities (Jackman Reference Jackman2019; Khan Reference Khan2000). Meanwhile, in urban Pakistan and Indonesia, gangs have long competed for control of protection rackets and illicit markets while providing some public goods, developing close relationships with a variety of political parties in the process (Siddiqui Reference Siddiqui2022; Tajima Reference Tajima2018).

And yet, despite the prevalence of criminalized governance in the contemporary world, gangs and other OCGs have been mostly ignored as consequential political actors. The discipline of political science has long been interested in how a variety of armed actors (states, insurgents, paramilitaries, and terrorists) control territory and govern populations, but these same behaviors by gangs and other criminalized groups have been almost completely overlooked. Why?

Historically, this oversight was justified by their lack of overt political ambitions pertaining to the state and, as I often heard from audiences when presenting this project early on, the belief that gang members “are just criminals.” Such a perspective is thoroughly biased in two ways. First, political science as a discipline has incorrectly assumed that modern states, unless in the midst of war, successfully monopolize legitimate violence within their territories. This hegemonic assumption stems from Weber’s iconic definition: “a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of violence within a given territory” (1965). Drawing from the early twentieth-century European experience, Weber’s idealized state shares little in common with the vast majority of states in the modern world (Barkey Reference Barkey1994; Centeno Reference Centeno2002; Davis and Pereira Reference Davis and Pereira2003; Herbst Reference Herbst2015). Seldom have states outside of Europe – or even European ones, for that matter – been able to monopolize “legitimate” violence within their borders.Footnote 5 In fact, many high capacity, democratic, and seemingly “peaceful” states will often contain a variety of non-state armed groups that operate and sometimes govern specific areas within their territory. While gangs and a variety of other criminalized groups may not consider themselves rivals to the state, their use of violence and governance practices have made it abundantly clear that we can no longer ignore their origins, motivations, and behaviors if we are to understand contemporary politics in a great many locations throughout the world.Footnote 6

The other source of bias is racial and of class. Political science has long regarded the “ordinary strategies that the black [and brown] urban poor embrace … as apolitical” (Alves Reference Alves2018, 197). This book, rather, contends that “black [and brown] youths’ deviant behavior (of which the figure of the gangster has become an icon) should be understood not only as counterhegemonic protest against racism and discrimination but also as a radical refusal to comply with white civil society” (p. 197).Footnote 7 Thus, joining and becoming a gang member, instead of being seen as an act of mere deviance or criminality, should be considered a political one. Moreover, the residents of the communities where gangs operate – favelas, ghettos, housing projects, etc. – are overwhelmingly underrepresented in higher education, much less the research community. For anyone who grew up in a neighborhood where gangs operate, the political nature of these organizations is self-evident, though often contested and disliked. The discipline has mostly overlooked the political nature of the violence that these communities have suffered and continue to endure, in part because incredibly few political scientists come from such neighborhoods. For these reasons, criminalized governance remains a significant blind spot for the discipline. By developing the conceptual and theoretical language to describe how and why gangs govern in the contemporary world, I seek to add to our understanding of the politics of the most marginalized within our societies.

The Argument

I argue that gangs govern not because their members are motivated by governance (it is a difficult and time-consuming task) nor by a desire to remake the political order that has placed them at the bottom of society. Instead, gangs govern because they inhabit an extremely dangerous world and need the obedience and support of local communities if they are to survive. To gain the type and degree of support they need from the local population, they must learn to wield power effectively, to deploy the tools – the carrots and sticks, so to speak – at their disposal. In this regard, I conceive of criminalized governance as comprised of two primary dimensions: coercion and the provision of benefits. On the one hand, gangs have developed a variety of coercive practices in the areas where they operate: they monitor entry and exit to their territories, maintain a physical and sometimes militarized presence on the streets, and can violently punish anyone that infringes on their economic activities or disobeys their rules. A gang that merely predates and dominates a community through coercion alone, however, is not governing. Such contexts are better thought of as disorder. To govern, gangs must place some limits on their coercive behavior and will often develop a set of beneficent practices that can include mechanisms for dispute resolution, economic stimulation, as well as opportunities for recreation, among others.

Not all gangs that govern, however, employ the same levels of coercion nor provide the same quality of benefits. In fact, we observe significant variation across these two dimensions. I distinguish between gangs that use low or high amounts of coercion and are responsive or unresponsive to resident demands for benefits. The interaction of these two dimensions produces four ideal-typical criminalized governance regimes. A social bandit gang will employ low levels of coercion while providing responsive benefits to the community. A benevolent dictator gang will use high levels of coercion but simultaneously offer responsive benefits to residents. A tyrant gang also employs high levels of coercion but is unresponsive to residents’ requests for benefits. Finally, a laissez-faire gang uses little coercion while providing few if any benefits to the community. Some gangs may maintain a particular type of governance regime for decades while others move back and forth across these regimes quickly. Gangs may even vary their governance practices within the areas in which they operate. This book seeks to explain this variation.

Building on three years of ethnographic fieldwork in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, I argue that criminalized governance is an innate strategic response to two kinds of threat, from rival gangs and from the police, that shape what a gang needs from residents.Footnote 8 First, a belligerent rival represents an existential threat to any gang organization and its membership because they are capable of conquering and expelling a gang from its territory.Footnote 9 In this regard, gang turf wars are an oft-documented phenomenon throughout much of the world. At the same time, many gangs have also found ways to avoid violence and warfare by negotiating, making peace, forging alliances, and developing arrangements to divide territory among themselves.Footnote 10 Given this variation in intergang relations, I argue that gangs can face three different levels of rival threat: active, latent, or absent.

An active threat is when a gang faces a rival that is intent on taking over their territory, which can include everything from all-out invasions, skirmishes, and drive-by shootings to targeted kidnappings and assassinations, as well as more subtle attempts to infiltrate a territory. A latent threat, by contrast, applies to contexts where a gang does not currently face a rival actively trying to take over their territory but due to proximity, a history of conflict, or previous territorial turnover, the possibility of violent contestation is high. Finally, an absent threat means a gang faces no competitors for territorial control. This is often due to a group having successfully defeated and absorbed all local rivals, their relative geographic isolation, or the result of stable alliances or arrangements with surrounding gangs. Gangs can shift back and forth across these levels rapidly while, in other cases, rival threat builds slowly or gradually diminishes. Some gangs may experience multiple rival threats at the same time. Others may have never faced a proximate rival.

I argue that the degree of rival threat determines the coercive practices gangs will use against the population within its territory. If a gang loses its turf to a rival, incumbent gang members and their families will either be killed or expelled from the territory. Therefore, when facing an active rival threat, gang members will defend their turf at all costs, diverting any available resources and manpower to prevent their enemy from invading and infiltrating their territory. They will remove any existing limits on their coercive behavior because, in the fog of war, gangs cannot put the concern for resident well-being above the need to defend their territory. In these contexts, I predict gangs will use extreme levels of coercion directed at residents as they demand higher levels of obedience and fear collaboration with their rival. They will question, threaten, and expel anyone they think does not belong, ostentatiously display themselves and their armaments as a constant reminder to residents that they dominate the territory, and will engage in brutal and public punishments of anyone suspected of betrayal. These contexts are best understood as disorder. For latent threats, gangs will still closely monitor their borders, maintain an extensive physical presence, and punish disloyalty but they will refrain from the most extreme forms of coercion and not divert all their attention and resources to the defense of their turf. Finally, an absent threat translates to a gang that will take a more relaxed approach to controlling their territory. They will not monitor their borders assiduously, be less physically present on the streets, and refrain from violent punishments.

I argue that the threat of police enforcement, unlike that of a rival, constitutes only a transient threat to gangs, one that can also vary from active to absent. Even amid active and highly militarized enforcement efforts, the police almost never represent an existential threat to gangs because they seldom seek a permanent presence within these neighborhoods and do not look to take over local illicit markets like a rival would. Instead, police enforcement the world over mostly focuses on weakening gangs and combatting illicit markets by arresting their members and by confiscating weapons, drugs, or other illicit material. Although gangs may occasionally confront police directly, they generally refrain from such tactics because: (1) they know police will only be present for a short period of time and (2) this will only cause further police attention and enforcement. Therefore, gangs do not defend their territory at all costs like they do against rivals but rather seek to evade enforcement by melting into the population. Not all gangs, however, face active enforcement. Some gangs have developed durable bribery schemes or tacit agreements with the police that prevent or limit enforcement. Other gangs operate in areas where police may seldom go, either due to a lack of resources or because they have decided that enforcement is too costly or unattractive.

I argue that the degree of transient threat from police enforcement determines a gang’s willingness to provide benefits to local communities. Where enforcement is active and frequent, gangs will seek greater levels of support from the community in the effort to avoid enforcement. In these contexts, gangs need residents to at least not inform on them and sometimes their direct assistance to evade the police. As a result, they are more willing to resolve disputes for residents, provide economic stimulation, and organize opportunities for recreation. Gangs that face little or no enforcement, however, need the community less and will provide little in terms of benefits.

Although gang-level incentives may seem to predominate, criminalized governance is not merely imposed from the top-down. The role of residents is crucial. This insight has already been baked into the theory as residents are presented with a series of constraints and opportunities for gaining access to scarce resources and providing for their safety within each of the security environments described earlier. How residents respond to gangs within each of these environments shapes the nature of the threats that gangs face and, in turn, the governance outcomes observed. I argue that there are two resident behaviors, in particular, that matter to governance outcomes: denunciations and demands. On the one hand, residents of gang territories have sensitive information regarding gang members’ activities, whereabouts, routines, and social relations. This information is extremely useful in the hands of rivals and the police. Where a gang faces an active or latent threat from a rival, they will employ higher levels of coercion to try to prevent and deter residents from offering sensitive information to their enemy. Residents can do little to limit coercion in these circumstances because the nature of the threat is existential.

When gangs face high levels of police attention and enforcement, however, residents have more leverage over gang behavior. First, the transient nature of enforcement does not require the same coercive gang response and, second, unlike denunciation to rivals, which is extremely difficult and dangerous, residents can often provide information to the police quite easily through emergency phone numbers or hotlines created specifically for this purpose. Thus, when enforcement is active, gangs are incentivized to seek out closer, more beneficial relations with residents because they need residents to refrain from denouncing them to the police. The use of coercion in such circumstances is counterproductive because gangs have a difficult time knowing who is informing on them and, therefore, who to target. Moreover, indiscriminate forms of coercion while enforcement is active will only lead to further denunciation and even more frequent police enforcement efforts. Where enforcement is not forthcoming, however, either through bribery schemes or the lack of police presence, denunciation does not produce the same effect and gangs are not incentivized to develop such reciprocal relations with local communities.

Finally, although gangs often manage to provide benefits to communities when and where they attempt to do so, they cannot resolve disputes, provide welfare, or create opportunities for recreation if residents refuse to accept them. Thus, when and where residents “demand” (ask for and accept) gang benefits is essential to understanding these outcomes. While perhaps not as consequential as denunciations in terms of the local security environment, demands and the more collaborative relations that they engender between gangs and residents are equally important to the survival of any gang organization. In this way, criminalized governance should be understood as a two-way street; residents always play a fundamental role in shaping the nature of these arrangements. Overall, I argue that criminalized governance is a joint production, the result of frequent and repeated interactions between gang members and residents within particular security environments.

Contributions to the Literature

An emerging research agenda spanning several social scientific disciplines has slowly begun to investigate the origins, causes, and consequences of governance by gangs and other OCGs. Although the literature generally refers to this phenomenon as criminal governance, I employ the term criminalized governance because, ultimately, the state – both representing and shaping the interests and opinions of society at large – is the arbiter of what activities, practices, individuals, and groups are considered to be “criminal.” If we are to sufficiently understand how and why such groups engage in governance, the processes by which some individuals and groups are criminalized while others are considered acceptable or even legal must be acknowledged and incorporated into our frameworks.Footnote 11 Notwithstanding this conceptual correction, the theoretical framework I develop contributes to three distinct analytical traditions within this quickly expanding literature, which implicitly or explicitly equate criminalized governance to processes of state making, rebel governance, or state perversion. In the following sections, I describe how this book borrows key insights from each of these approaches and contributes to them in multiple ways. Overall, this book attempts to build more and better bridges between these parallel literatures by highlighting points of similarity while remaining cognizant of the distinctions.

Criminalized Governance as State Making

The first framework views gangs and other OCGs as would-be states and their governance activities as incipient forms of state making. In this tradition, today’s nation-states are understood as the descendants of racketeers from the late Middle Ages that created governing institutions because “the provision of a peaceful order and other public goods gives the stationary bandit a far larger take than he could obtain without providing government” (Olson Reference Olson1993, 568) and because providing governance can generate “quasi-voluntary compliance” with the effort to extract resources (Levi Reference Levi1989). Counter-intuitively, then, it was the self-interested and avaricious bandit that settled down and began providing services and benefits to populations.

Developing governance structures and institutions (i.e. state making) was never the explicit intent of these bandits but were “inadvertent by-products of efforts to carry out more immediate tasks, especially the creation and support of armed force” (Tilly Reference Tilly1992, 26). Almost by necessity, the conquest of territory through warfare involved providing some services to local populations that included redistribution of lands, encouragement of production, adjudication of disputes, and, inevitably, extraction (p. 20). This process quickly became self-reinforcing. The concentration of the means of coercion within a specific territory facilitated and demanded resource extraction that, in turn, built governing institutions, which then allowed the ruler to continue to expand their territory and build more extensive governing institutions. In this way, war making, extraction, and governance slowly (over several centuries) produced elaborate bureaucracies and governmental institutions (tax collectors, courts, exchequers, and, eventually, police forces) that would extend the power of the state directly into the lives of each and every citizen, thus bringing about a more peaceful order.Footnote 12 Here we have the basic components of a bellicist theory of governance that revolves around the extraction of resources amid violent competition for control of territory and population.

Like the bandits of the late Middle Ages, the governance that gangs engage in is often related to similar processes of violence and competition. Due to their criminalization by the state and society, gangs exist within what can be considered anarchic security environments (Sánchez-Jankowski Reference Sánchez-Jankowski1991; Skaperdas and Syropolous Reference Skaperdas, Syropolous, Fiorentini and Peltzman1995). Gang members must constantly be willing to use or threaten violence to protect themselves and their interests against would-be rivals, of which there can be many; single gang cities are incredibly rare. Given these anarchic conditions, gangs often fight wars for territorial supremacy. The fact that gangs fight wars has yet to be truly appreciated by scholars of political violence because they generally only occur within cities and states that we have traditionally considered to be “at peace.” Moreover, such wars seldom threaten the “fortified enclaves” (Caldeira Reference Caldeira2001) of the middle classes and elites, much less the functioning of government institutions. They are mostly contained within the marginalized and impoverished neighborhoods where gangs and other criminalized groups emerge and operate. In this book, I argue that gang warfare (and its threat) incentivizes gangs to behave in ways that resemble the state makers of yore: they seek to consolidate territorial control, eliminate all internal threats and enemies, and extract resources. If state-making theories are correct, it should come as no surprise that these contexts provide the primary examples of gangs that govern.

The state formation approach to criminalized governance seems, initially, to be a fruitful path to understanding its underlying dynamics. However, unlike early state-formers, gangs exist within states that have already accumulated the concentrated means of coercion. Thus, when contemporary gang organizations engage in warfare with rivals, they are not battling for absolute territorial control which precedes the state. Instead, they are self-consciously competing for territories within states. Gangs are not interested in taking over or breaking away from the state. In fact, the state plays a starring role in where violence escalates and where it is contained. The state can often be the deciding factor in which gangs emerge victorious as security forces may protect some while allowing others to perish. In addition, although the presence and responsiveness of the state and its institutions may be weak or only partial for resident populations in areas where gangs operate, citizens and communities continue to make demands of the state, either directly to the public security apparatus or through electoral and political processes. These differences make the direct application of this framework not so straightforward, as others have pointed out (Koivu Reference Koivu2016; Lessing Reference Lessing2020).

Despite this key difference, the state making approach offers key insights to the task at hand. First, the accumulation of the means of violence is an inherently political project, whether governance is the group’s primary motivation or not. By overlooking gangs’ lack of overt political motivations regarding the state and focusing our attention more squarely on their actual activities and behavior, we can more clearly recognize how they have managed to accumulate political authority. Second, this approach places violent competition and the strategic environments in which these actors operate at the center of the analysis. How gangs deal with threats to their organization and the role that residents play in intensifying or diminishing those threats are crucial to understanding how and why they govern.

Criminalized Governance as Rebel Governance

The second analytical framework stems from the emerging research agenda on rebel governance. Like the state-making approach, competition over territory and population plays a central role in theories of rebel governance. Rebel groups, by definition, are engaged in violent conflict with the state and, therefore, their governance activities can only occur within this broader contestation for control of territory and population. The contours of this growing literature are still evolving but the fundamental thrust is that civil war represents “competitive state-building” (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006) in which rebel groups are attempting to implement their vision of an alternative political order. To do so, they create structures and institutions that not only correspond to that vision, but which help them gain the support of the local population and maximize the byproducts of territorial control (like recruitment and access to resources) in their effort to win the war. Rebel governance has been found to vary significantly even within territories held by the same overarching rebel organization. The effort of many scholars working in this area has been to explain the causes and consequences of this variation.Footnote 13

Rebel governance shares a surprising resemblance to criminalized governance in several respects. First, like rebels, OCGs can vary from being indifferent to territory and populations to out-administering the state in others (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2015a, 1534). Some OCGs have even been known to “secure the allegiance and identification of large segments of society” (Felbab-Brown Reference Felbab-Brown2010, 158), thus resembling more overtly political movements. In addition, some gangs have even been known to directly confront state security forces, what has been referred to as “criminal insurgency” (Killebrew Reference Killebrew2011; Manwaring Reference Manwaring2005; Sullivan Reference Sullivan2010) or “cartel-state conflict” (Lessing Reference Lessing2017), thus, even more closely resembling civil war contexts. Finally, although generally thought to be uniformly antagonistic, gang- and rebel-state relations have been shown to vary along a similar continuum from collaboration to competition (Barnes Reference Barnes2017; Staniland Reference Staniland2012).

Despite these numerous points of overlap, there are strong arguments against a wholesale adoption of this framework. The primary difference between gangs and rebels concerns their raison d’être. While I disagree with the simple distinction between criminal and political motivations that much of the literature adheres to (see Barnes Reference Barnes2017), rebels are almost always seeking the larger goal of secession, state capture, or political reform (Kasfir Reference Kasfir, Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015, 23). In this effort, they govern not only to gain the support of local populations, but to demonstrate to the international community that they are capable and responsible rulers, what Mampilly has referred to as “juridical sovereignty” (2011, 39). Gangs and other criminalized groups may maintain de facto sovereignty but have no interest in juridical sovereignty. They certainly do not seek the support of states within the international system, thus making these forms of governance potentially quite distinct. Moreover, rebel groups that have consolidated their territorial control seldom allow state institutions and agents to continue to function in these areas. This is never the case for gangs that will allow various aspects of the state (including the police) to continue to operate in their turf even as they claim exclusive control vis-à-vis their rivals (Barnes Reference Barnes2022b). As such, gangs and other criminalized groups generally prefer lower profile and informal governance mechanisms that can overlap or coexist with some forms of state governance. In this regard, numerous scholars have argued that comparing gangs and OCGs with rebels is misguided and produces counter-productive policies (Arias Reference Arias2006a; Lessing Reference Lessing2017, Reference Lessing2020; Rodgers and Muggah Reference Rodgers and Muggah2009). These are compelling arguments for the continued distinction between rebel and criminalized governance.

While I agree that we must not equate OCGs with rebels, discarding the parallels between these forms of governance would be equally unwise. This project borrows three important insights from existing work on rebel governance. First, while many rebel groups may obtain the obedience or acquiescence of local populations through the threat of violence, they must also gain the willing or active support of at least a segment of the population if they are said to govern.Footnote 14 In this regard, conceptualizations of rebel governance nearly always include both the use and threat of force (coercion) as well as the provision of some benefits.Footnote 15 Similarly, I argue that we cannot understand criminalized governance without focusing on both the coercive as well as beneficent activities. They constitute separate but complementary sides of the same governance coin.

Second, violent competition for territorial control plays a major role in shaping rebel governance. In his seminal work on the logic of violence in civil war, for instance, Kalyvas (Reference Kalyvas2006) demonstrated how armed groups shift their repertoires of violence and, thereby, relations to civilian populations depending on the type and degree of territorial contestation vis-à-vis other armed groups. Other scholars have similarly shown that governance of civilians is often subordinated to the strategic considerations regarding the ongoing civil war and may even be suspended during more conflictual periods.Footnote 16 The theory of criminalized governance I develop builds on these works by tracing the logic and mechanisms through which violent territorial competition between rivals translates to the greater use of coercion against local communities.

Finally, the role of civilians in determining the nature of rebel governance arrangements is an insight which this project applies to understanding how and why gangs govern. In civil wars, some communities have refused to cooperate with rebels, resisting their attempts to govern at every turn.Footnote 17 In other cases, communities have embraced rebels, welcomed their governance initiatives, and provided them significant support in their effort to win the overarching war in return.Footnote 18 Again, these dynamics map quite easily onto contexts of criminalized governance: existing work finds a similar variation in citizen responses to gangs and other criminalized groups, from direct support to begrudging obedience to overt resistance and even mobilization.Footnote 19 How and why individuals and communities respond in these ways has yet to be fully explained but this book offers some clues by providing a micro-level analysis of how civilian responses map onto and shape criminalized governance activities.

Criminalized Governance as State Perversion

The final approach views criminalized governance as a direct result of perverse states. Until the turn of the millennium, numerous scholars had come to view the region’s increasing levels of violence and crime as a consequence of neoliberal reforms: the hollowing out of social services, the shrinking of the public sector, and the limiting of access to systems of law and justice (see Leeds Reference Leeds1996; O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1993). Desmond Arias was one of the first to articulate a different explanation, arguing that the proliferation of “criminal governance” (in perhaps the first use of the term) was not the product of state absence or failure but rather the result of a state that was present (2006b, 294). A variety of scholars quickly followed suit, documenting how criminalized groups governed through clandestine networks involving politicians, public security officials, licit businesses, and community leaders, what Auyero (Reference Auyero2007) referred to as the “grey zone.”Footnote 20 According to Arias, these illicit networks “provide important conduits through which impoverished populations, historically excluded from basic political protections and economic opportunities, are incorporated under conditions of dependency and violence into a wider political system” (2013, 282). From this perspective, criminalized governance can be seen as a perverse form of state building in highly unequal societies.Footnote 21

Overall, the perverse state approach offers a persuasive argument for how and why gangs and other criminalized groups emerge and engage in governance. Departing from a Weberian understanding of the state, this tradition highlights the many ways that states themselves have given rise to the very groups they are purportedly combatting. By marginalizing segments of their citizenry, refusing to provide them with rights and services, engaging in a variety of corrupt and unsavory practices within these communities, and arbitrarily and cynically applying the rule of law, it is little wonder that a variety of organizations willing to engage in crime and violence have gathered authority outside of the state. Instead of combatting them by striving to (re)incorporate marginalized populations within the body politic, Latin American states have overwhelmingly chosen to militarize their policing practices (Flores-Macías and Zarkin Reference Flores-Macías and Zarkin2021), pushing citizens of these areas even further toward alternative governance arrangements (Koonings and Kruijt Reference Koonings and Kruijt2004; Wolff Reference Wolff2015). For anyone familiar with the politics of the Latin American region, this is a compelling vision for how and why gangs and other criminalized groups govern.

One of the major flaws of this approach, however, is that it seldom offers gangs or other criminalized groups and their members much agency. Scholars within this tradition seldom focus on the strategic behavior of gangs and their members. Instead, the networks and connections to the state often override any bottom-up processes, including how residents relate to gangs in these areas. While many studies have compellingly shown that gang violence and authority are heavily influenced by top-down processes, how gangs order space, recruit members, provide welfare, develop informal systems of law and justice, and offer access to illicit markets are not structurally determined. What this book contributes is a ground-level analysis of how gangs and their members are capable of a remarkably diverse set of actions and reactions to these difficult and constrained environments.

Existing research has mostly overlooked the bottom-up aspects of criminalized governance because these activities are extremely difficult if not impossible to observe directly. By its nature, criminalized governance is nearly always informal and clandestine. Gangs and other criminalized groups seldom keep records and always try to prevent the authorities and larger society from finding out about these activities.Footnote 22 Moreover, those receiving criminalized governance services seldom want the authorities, local institutions, or even their neighbors to know about these exchanges due to the significant stigma and perhaps even the legal repercussions of such connections. As a result, we have mostly been unable to document much less theorize a whole range of governance activities which are the bread and butter of any criminalized organization. Moreover, we have failed to understand these activities from the perspective of their protagonists, the providers and subjects/beneficiaries of such governance. This book seeks to break new ground by taking you, the reader, inside the organizations and communities where such practices take place. In the next section, I outline the mixed-method ethnographic approach required to provide such a perspective of criminalized governance as well as the various ethical, security, and positionality considerations necessary to conduct such research.

Research Design and Fieldwork

This book employs a comparative ethnographic research design. By ethnography, I refer not just to interviews and long-term fieldwork but the use of participant observation and “immersion in the place and lives of people under study” (Wedeen Reference Wedeen2010, 257). Many ethnographers have focused on single case studies to highlight complexity and contextual meaning while mostly ignoring case comparisons and explicitly refuting claims of generalizability. In a recent innovation, however, Simmons and Smith have argued that ethnographers can better engage with broader theoretical debates by conducting “ethnographic research that explicitly and intentionally builds an argument through the analysis of two or more cases” (2019, 341). This book takes just such an approach by comparing the governance activities of three separate drug-trafficking gangs over four decades. It traces the evolution of each of these organizations, from their emergence as fledgling street gangs to powerful drug-trafficking organizations, with an eye toward understanding how and why their governance activities have shifted over that time. Analytical leverage is gained not only through comparison across these cases but also the temporal and spatial variation within each.

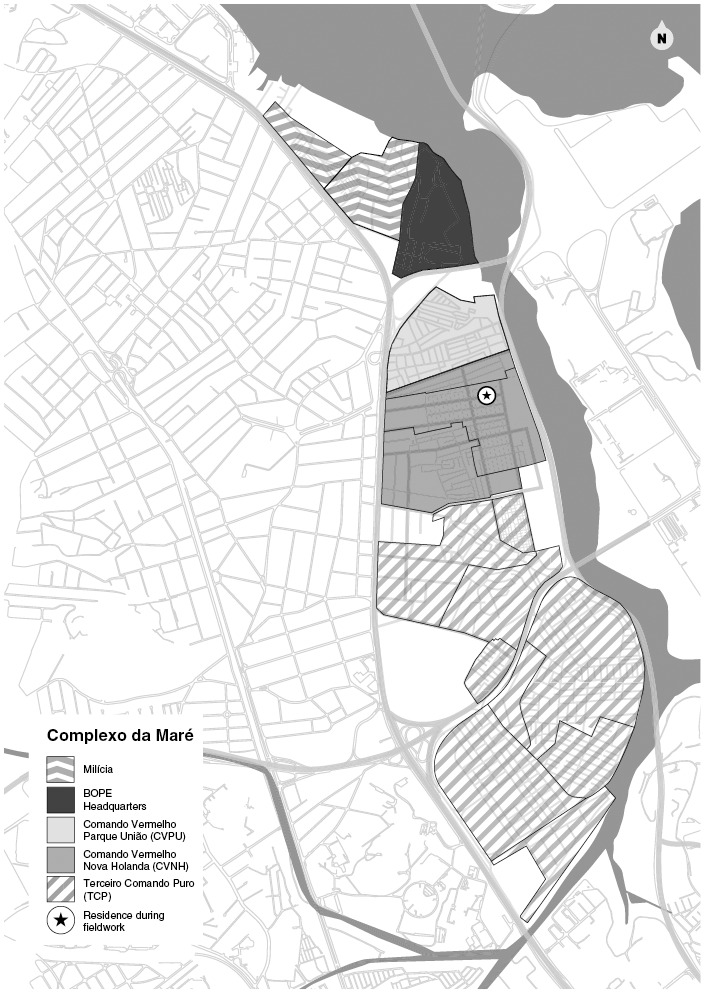

I engaged in more than three years of multi-method fieldwork in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and eighteen months of ethnography in Complexo da Maré, a sprawling complex of fifteen favelas and housing projects, in which three separate drug-trafficking gangs operate. In June 2013, I moved to Nova Holanda (see Figure 1.1), one of three contiguous neighborhoods controlled by a gang I refer to as Comando Vermelho of Nova Holanda (CVNH). Although I resided in this one gang’s territory, I travelled extensively throughout Maré, spending several days a week in Maré’s two other gang territories, one of which was also affiliated with the CV faction and located in an adjacent neighborhood, Parque União (thus, CVPU). The third gang, which controlled ten contiguous favelas and housing projects in the south of Maré, was connected to CV’s primary rival, Terceiro Comando Puro (TCP).

Figure 1.1 Map of gang territories in Complexo da Maré during fieldwork

In April 2014, nine months after I moved to Maré, 2,500 Brazilian Army and Marine troops invaded and occupied the entirety of Complexo da Maré. The intervention represented the culmination of Rio’s Unidades de Polícia Pacificadora (Police Pacification Units) or UPPs, a public security program intended to recapture the state’s “monopoly of violence” from drug-trafficking gangs in hundreds of favelas throughout the city. The military occupation was initially intended to be short-term – just four months – to weaken the gangs and build local capacity before the installation of four community policing units. This would never come to pass. Instead, the military occupied Maré for fifteen months, during which time I continued my fieldwork, living in Maré for another nine months, concluding initial data collection in November 2014. I returned to Maré in July and August 2015 immediately following occupation, again in 2017 and 2018 for several more months of follow-up research, and finally in 2023 for a few months.

During the original fieldwork period, I spent 24 hours a day, seven days a week in my field site. To the extent that a gringo (foreigner) could, I tried to live like other favela residents. I shopped at local supermarkets, ate at favela restaurants, exclusively used informal and public forms of transportation, and attended numerous music performances, sporting events, and other local cultural events. I became intimately familiar with each of Maré’s fifteen neighborhoods by walking or biking through the labyrinth of streets and alleyways. Prior to military occupation, I attended dozens of gang-organized bailes funk (funk parties), birthday parties, and holiday celebrations while subjecting myself to gang rules. During military occupation, I attended numerous public meetings and events organized by the military and was able to observe their daily operations. Such an immersive and participatory methodology allowed me to document how each of Maré’s gangs governed these communities as well as how their behavior changed over time.

Given Maré’s size (roughly 1.25 square miles) and population (approximately 140,000 residents), a comprehensive accounting of criminalized governance through participant observation alone was not possible. Therefore, I also collected several other forms of data. I conducted 206 semi-structured interviews, 73 of which were with current and former gang members, 73 with community leaders, 48 with a cross-section of residents, and 12 more with scholars, researchers, and public security officials.Footnote 23 I identified most of these research subjects through a “snowball sampling” of the various social networks in which I became embedded. Interviews were conducted on the street, in public plazas, in my apartment, in my interlocutors’ homes or businesses, or at local NGOs, lasting anywhere from thirty minutes to more than three hours. I did not record the interviews due to security concerns but instead took copious notes, which I immediately translated and typed up after the interviews.Footnote 24 All names are pseudonyms and I have avoided using any specific information which could be used to identify these individuals. Beyond these semi-structured interviews, I also engaged in hundreds of less formal conversations and thousands of daily encounters and interactions across all three gang territories that I wrote up in more than 400 pages of field notes. Finally, I supplement these personal observations and interviews with hundreds of newspaper articles, government reports, and archival documents, as well as micro-level data concerning gang and police behavior from Disque-Denúncia (Denunciation Hotline, hereon DD).Footnote 25

Case Selection

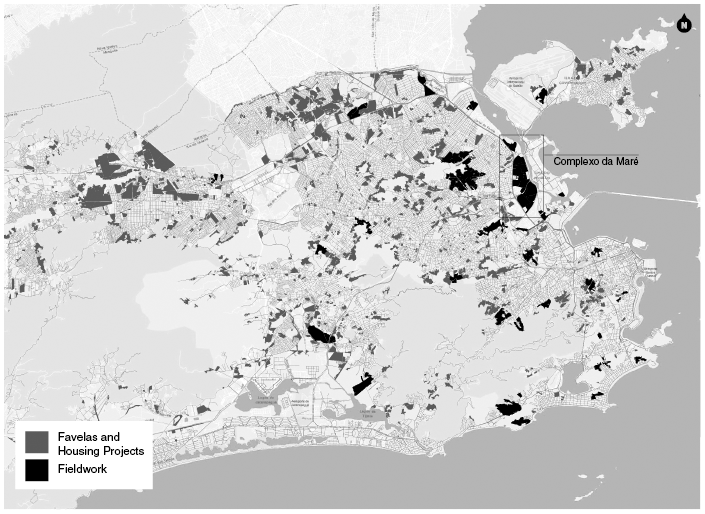

Following two preliminary research trips in 2010 and 2011, I moved to Rio in October 2012 and quickly began searching for suitable field research sites. This sprawling city of six million has roughly 1,100 favelas (see Figure 1.2), which vary in size from several hundred residents to more than 70,000 (Instituto Pereira Passos 2018). Nearly all favelas have been dominated by drug-trafficking gangs or police-connected milícias (militias) that run protection rackets for the past three decades. Every favela-based gang is at least nominally connected to one of three factions located within the city’s prisons: CV, TCP, and Amigos dos Amigos (Friends of Friends, hereon ADA).Footnote 26 While all the city’s gangs can be considered part of these prison-based factions, they are better understood as horizontal networks of alliance rather than singular, hierarchical organizations (Dowdney Reference Dowdney2003, 31). Importantly for this book, governance practices are entirely dictated by the gang’s Dono (leader) and its membership on the streets of the favela, not the faction in prison.

Figure 1.2 Map of fieldwork in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas and housing projects

I spent the first nine months of fieldwork taking every opportunity to visit favelas throughout the city. In total, I visited nearly 60 separate communities (see Figure 1.2), where I learned about the local geography, history, security dynamics, and gang practices while also exploring the possibility of conducting longer-term research. During this initial phase, I also interviewed twenty rehabilitated gang and milícia leaders from favelas across the city. I connected with these former members through AfroReggae, an influential NGO that had developed an impressive program to assist individuals in leaving these organizations. These interviews were invaluable in helping me understand the complex histories and structures of the gangs, the breadth of their governance activities, and their evolution over time.

Through these initial visits and interviews, my understanding of Rio’s gangs increased incredibly but remained superficial. Up to this point, my research had revealed the breadth and scope of criminalized governance, but even when I got access to these communities and their members, I found many of the answers to my questions were “pra Inglês ver” (literally, “for the English to see”), as many favela residents put it.Footnote 27 That is, they had answers to questions from outsiders that did not correspond to their lived experience because it was too difficult to explain the reality, that’s what they thought I wanted to hear, or they were perhaps afraid of the legal or moral connotations of revealing the truth (Wood Reference Wood and Schatz2009). Alternatively, offering such canned responses could have been a way for some of my interlocutors to deny access to certain parts of their life or perhaps a subtle way of refusing to be studied or analyzed at all (Simpson Reference Simpson2007). Whatever the reason, I wanted a more intimate understanding that was not possible from interviews alone or from spending the occasional afternoon in favelas.Footnote 28 If I was going to understand the causes and consequences of criminalized governance, I needed to place myself inside these communities.

Over the course of the initial period of field research, one case – or set of cases, rather – began to stand out as an ideal location in which to conduct long-term fieldwork. Complexo da Maré (highlighted in Figure 1.2) is located in the Zona Norte (Northern Zone) of the city along the banks of Guanabara Bay. There are three reasons why I chose Maré as my primary field site. First, Maré is the only group of favelas in the city in which multiple OCGs control territory: two gangs connected to CV, another to TCP, as well as a police-connected milícia (see Figure 1.1). Their proximity offered a unique opportunity to compare across these organizations. In addition, the nature of competition between these groups and their shifting territorial control within Maré allowed me to focus on how gangs won and lost territory and the consequences of territorial expansion and contraction on their governance activities. Finally, because of its location at the intersection of three of the city’s major traffic arteries – Avenida Brasil, Linha Vermelha, and Linha Amarela – and its proximity to the international airport, Maré has also been the focus of considerable public security attention over the years. In fact, Maré has the only Military Police Battalion (the 22nd) located inside its borders and the headquarters of the Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais (Special Police Operations Battalion) or BOPE was moved to the outskirts of Maré in 2011 (see Figure 1.1).Footnote 29 Together, these characteristics made Maré an ideal context in which to study criminalized governance.

I first visited Maré on a preliminary research trip in 2011 and began making regular trips soon after beginning fieldwork in 2012. For my first several visits, I met NGO workers along Avenida Brasil – the city’s busiest highway that runs the length of Maré – and they brought me into the community, passing by gang olheiros (lookouts) that monitor all the entrances to these neighborhoods. Over time, gang members became used to my presence and, eventually, I was able to come and go without a chaperone. Then, in June 2013, one of my local contacts informed me of a studio apartment available for rent in Nova Holanda. The rooftop apartment was near a couple of local NGOs and a safe distance from the border separating Maré’s rival gangs, where most inter-gang violence occurred (see Figure 1.1). Later that month, I moved to Maré and would permanently reside there until November 2014.

When I selected Maré as my field site, I did not know that the military would eventually occupy the area. On March 21st, 2014, just two months before the start of the World Cup, in a meeting with then-President Dilma Rousseff, the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Sergio Cabral, formally requested the assistance of Federal troops to occupy Maré. Three weeks later, and roughly nine months after I moved to Maré, the Brazilian military invaded all fifteen of Maré’s neighborhoods and would stay there for the duration of my fieldwork.Footnote 30 Thus, the research design for this book evolved organically and, in this way, reflects how events occurring on the ground can provide opportunities for inquiry and investigation, one of the distinct advantages of long-term ethnographic fieldwork (Gade Reference Gade2020).

Ethics and Safety

At this point, it is important to recognize that built into my desire for greater understanding and access was the considerable power and privilege that I had as a white cisgender male researcher from a prestigious university in the Global North. After all, going to the field much less spending three years there is an enormous privilege, one that the vast majority of researchers do not have (Fujii Reference Fujii2016, 1149). Moreover, the type of access I enjoyed in many favela communities was predicated on the existing inequalities between myself and my interlocutors because access and its refusal are very much “a privilege of the powerful” (Krystalli Reference Krystalli2021, 137). Especially for communities that have been, from their origins, heavily surveilled by the state and thoroughly under the microscope of social science, such inquiry can simultaneously be a form of invasion (Tuck and Yang Reference Tuck and Wayne Yang2014). Therefore, ethnographers and researchers of marginalized spaces must recognize the inherently extractive nature of such research and should tread with caution, sensitivity, and respect when entering these communities to study or document life there. As Lee Ann Fujii reminds us, “…to enter another’s world as a researcher is a privilege not a right” (Reference Fujii2012, 722). In the rest of this section, I first address some of the ethical and security considerations of my fieldwork before analyzing how my positionality shaped and informs the data to which I gained access.Footnote 31

Conducting research on gangs in favelas requires significant consideration of local security dynamics, possible risks for would-be research participants, as well as issues surrounding confidentiality and anonymity.Footnote 32 In Rio’s favelas, gangs have implemented their own set of rules which govern daily life: no speaking to the police, no theft in the community, no fighting between residents, and no sexual or domestic abuse, among others. Submitting myself to gang rules was an important part of the ethnographic experience but learning which behaviors were circumscribed or which topics of conversation were acceptable was a slow process. Gang rules are not written down and local customs often go unspoken. In this regard, I relied on the help of several NGO workers and residents that had grown up in Maré and who were intimately familiar with these local dynamics and whose patience and guidance were instrumental in my learning process. Several of these collaborators had worked with other researchers in the past, helping them identify suitable interview participants. Two of these collaborators would eventually complete Institutional Review Board training and become formal and paid members of my research team.Footnote 33 With one of these research assistants, whom I refer to as Carlos (a pseudonym), we developed a set of guidelines for research activities, where and when we could engage in them, and the locations that were safe for us and the research participants.

With the support of Carlos, other research collaborators, my expanding social networks, and by merely spending a lot of time observing and listening, I learned how to stay safe. The social networks in which I became embedded not only provided me greater information and access to interlocutors but also offered increased security. Malejacq and Mukhopadhyay (Reference Malejacq and Mukhopadhyay2016) refer to this as building one’s own “tribe” or “forming and joining different social micro-systems to collect data and, in some cases, survive” (2016, 1014). I also developed what Baird (Reference Baird2018, 346–47), following Bordieu (1992), refers to as “a feel for the rules of the game” and “practical sense” that helped me evade danger. I began to identify the signs of an approaching police operation or rival gang invasion by watching the traffic patterns, the movement of pedestrians, and the sights and sounds of the favela. I came to quickly recognize the far-off sounds of a police helicopter and eventually was able to differentiate between firecrackers and gunshots. Innate to most favela residents, these were indispensable skills for staying safe.

During my first several months living in Maré, I mostly refrained from conducting interviews. I first wanted to gain a better understanding of local dynamics and allow residents and gang members to become comfortable with my presence before jumping into formal interviews. I sought to take things as slowly as possible at each stage of the research process because of the inherently fraught nature of conducting research within these marginalized communities and because I had never heard of another long-term ethnographic project that focused explicitly on gangs and involved them as research participants. I decided to err on the side of caution. To my surprise, however, there seemed to be little suspicion and reticence about me and my project. My connections to respected NGOs and the fact that several interlocutors and collaborators vouched for me was essential. Moreover, because I was living in Maré, residents and gang members alike were assured that I was interested in more than just a superficial understanding of their lives and was not there to extract information before quickly leaving.

I found many residents were open to the possibility of being interviewed. While residents seldom speak directly about gangs in public, conversations about violence and crime are frequent. Most often, they take the form of passing comments about shootouts or police operations. In more private settings, residents are quick to share their experiences, interactions, and opinions about gangs. Such conversations are one way that residents keep informed about local security dynamics and to deal with the stress of these environments. I had to be careful, however, not to take any stories or conversations at face value. News travels quickly through favela communities and fofoca (gossip) and rumors about such topics are rampant (Grillo Reference Grillo2013, 17–18; Menezes Reference Menezes2014). Therefore, I attempted to triangulate and verify accounts across several participants and with other forms of data, including newspaper articles, archival documents, and public security reports. That said, I was not only interested in ascertaining the veracity of these accounts. Gossip and the ways in which residents and gang members exaggerate, lie, prevaricate, and opine about gangs offered me important insights into what Fujii (Reference Fujii2009) has called the “logics” or patterns of meanings, which residents and gang members use to understand violence and crime as well as daily life in Maré. Interpreting these logics was crucial if I was to understand criminalized governance.

Positionality

Despite living in Maré and eventually becoming a more integrated member of these communities is not to say that residents and gang members did not recognize my foreignness or that they were not surprised by my presence.Footnote 34 Although it was not unheard of for a gringo from the Global North to visit Maré or conduct a short-term research project there, most residents had never met one who lived there.Footnote 35 Some residents, even ones I came to know quite well, merely referred to me as “gringo.” I was an oddity, to be sure. My gringo-ness, however, was a distinct advantage. First, part of the reason my research did not arouse more suspicion was because no one thought I was working for the police, a common fear for gangs and residents alike. A native Brazilian conducting research on the same subject would have faced far more suspicion in this regard.

In addition to being a gringo, my identity as a white cisgender male, a tall and bearded one at that, from a university in the Global North shaped the data I collected in ways large and small. How my race, specifically, influenced my research in Maré is difficult to pin down. First, it is important to note that racial identities and experiences of favela residents are significantly more diverse and heterogenous than is commonly thought. According to a recent census, roughly 37% of Maré’s residents identify as white (branco), 53% as brown (pardo), and 9% as black (preto), with less than 1% as either indigenous or Asian (amarelo) (Redes da Maré Reference da Maré2019a).Footnote 36 That said, my whiteness surely shaped the nature of each and every interaction. Along with my gender and connection to a prestigious university in the US, it meant that I was offered immediate respect and deference in many situations and especially during interviews. I quickly gained access to people and places, not just in Maré, but in government offices, think tanks, and universities throughout the city.

My class is an equally important aspect of my identity to consider. Although Maré can be generally characterized as impoverished, it is not uniformly so. The socio-economic disparity within Maré stretches from individuals and families living in destitute poverty, without access to secure housing, water, or food, to lower middle-class families that own homes and businesses furnished with all the modern appliances and technologies. I conducted interviews across this entire spectrum. While it is impossible to change certain aspects of one’s class, I sought to diminish the socio-economic difference between myself and the community in which I was living. I tried to live a lifestyle like most other favela residents. I did not eat out frequently or extravagantly spend money at local shops or bars. I did not wear expensive shoes or clothes. I traveled exclusively by walking, biking, or by taking buses or vans (informal public transportation). I attended free and inexpensive forms of entertainment along with other residents. None of my participants (or anyone else in Maré for that matter) ever asked me for money nor seemed to expect payment of any kind though I would often pay for a meal, snacks, or beverages before or after interviews if the timing and occasion called for it.Footnote 37 As far as I could tell, I was not known as someone “with money” or someone whom residents or interlocutors could garner favors and resources though it is difficult to ascertain exactly how I was spoken of and understood among residents.

My gender also had considerable and perhaps more easily identifiable consequences for my research. First, the vast majority of gang members are men, and our common gender shaped our interactions, especially how they expressed their thoughts and feelings about violence and crime as well as their familial and romantic relationships. My gender allowed me to develop a rapport with these men in public, when they hung out in groups and engaged in conversations and exchanges on the street, in a way that a woman or non-binary researcher may have not been able to. That said, I avoided performing male bravado as a means of ingratiating myself with gang members or in an effort to become “one of the guys” (Baird Reference Baird2018; Theidon Reference Theidon2014).Footnote 38 Instead, I tried to maintain a professional yet relaxed attitude when interacting with them and in interviews. I did not become close friends with gang members and decided early on not to try to interview or “hang out” with gang members while they were on duty – shifts normally run for 12 hours, beginning at 6am or 6pm – because I wanted to be respectful of their responsibilities and the nature of their jobs often meant increased security risks.Footnote 39 I also avoided prolonged interaction with gang members at parties or bars at night, where alcohol consumption and drug use were common, due to the complicated ethics of these situations. Nearly all my interviews with gang members were when they were off duty and not obviously under the influence.

As a single man, I also had significant independence and autonomy within Maré that would likely not have been afforded to a woman. Maré, like most favelas in Rio, is comprised of surprisingly tight knit communities, which can sometimes have conservative ideas concerning family structure, gender roles, and sexuality. If I was not aware of it beforehand, this disparity was driven home during meetings of an informal research group of Brazilian and US ethnographers comprised almost entirely of women researchers.Footnote 40 We met once a month for the better part of a year to discuss our fieldwork experiences. Through these meetings, conversations, and visits to the favela communities in which these women were conducting their own ethnographic research, the numerous advantages I had as a product of my positionality became abundantly clear.

For one, our security fears differed enormously. I was most afraid of gang members not recognizing me or perhaps believing I was police and threatening or using violence against me as a result. I was particularly careful around gang borders because I did not want to be mistaken for a rival gang member or off-duty police. Gang members more frequently stop and question men and mistake them for security threats than women. On the other hand, like nearly everywhere else in the world, I was little concerned with just walking down the street of a favela or in the rest of the city even at night. Many of my female colleagues were extremely worried about being sexually assaulted or robbed and, over the course of my time living in Rio, several female friends and colleagues were victimized in these ways.Footnote 41

Beyond security concerns, no one ever gave me a hard time or judged me for living alone, staying on the streets late, or coming and going when I pleased. Some female colleagues found that community members monitored their behavior more closely and encouraged them to have a male companion or to attend church. They were also expected to assist in childcare or help neighbors while I was never asked to do so. Some of my colleagues even became pregnant and had children over the course of fieldwork. Aside from the incredible physical and emotional energy and effort required to raise a child while conducting fieldwork, this also dramatically changed their relationship to the local community. Some reported that they were even more closely monitored but that they were also often invited to parties and people’s houses, becoming even more integrated into the community. In this way, there were also research opportunities and conversations that, as a single man, I was not privy to.

Finally, the information and opinions that research participants offered me were also shaped by my gender. This was made especially clear when a female colleague and I conducted a couple of interviews jointly. These interviews offered a fascinating lens into the different behaviors and responses that research participants had to our presence. One older community leader, a man I had already interviewed individually and known to be very stoic and authoritative, became visibly emotional and openly wept when he told us about his mother. Following the interview, I marveled at his willingness to be vulnerable. My colleague told me that this did not surprise her at all as that interlocutor had cried in all her previous interviews with him as well. This example demonstrates how my gender and other intersecting identities influenced not only who I gained access to and the social networks in which I became embedded but also shaped the exchanges, assumptions, and responses during interviews. I note these dynamics here not to discount any of the information that I or other researchers gather through such methods but rather to emphasize how I tried to remain reflexive about the types of information and data to which I was given access.

Organization of the Book