Jack Rodney Laundon was born in Kettering, Northamptonshire on 28th July 1934. He attended Kettering Central School from 1945 until 1950 and was the only pupil in that year to transfer to the sixth form of the Grammar School. Early on he developed an interest in natural history, especially bird-watching but also lichens, and in 1952 obtained A-levels in botany, chemistry, and zoology but failed to secure a grant to attend university. At 18 he obtained work delivering telegrams for the Post Office but his heart was in natural history and on the off-chance he wrote to the then British Museum (Natural History), now the Natural History Museum, to enquire if they had any vacancies. A day or two later he received a reply informing him that annual interviews were being held the next day so he rushed off to London. Eight candidates were being assessed for two places and he was fortunate enough to be selected for the Department of Botany, where he remained until his retirement in 1990.

After his appointment on 1st November 1952, he worked for several months as a Scientific Assistant in the Mycological Section, where he dusted neglected lichen specimens; this suited him well in view of the interest in lichens he developed whilst in the sixth form at school. In 1953, to his dismay, he was transferred to the General Herbarium to curate foreign flowering plants; here he wrote taxonomic papers on Drosera, Geranium and Crassula, but also continued working and then publishing on lichens. He regarded his most exciting find as occurring in 1953, when pushing his bicycle through some heather in Northamptonshire on a damp winter’s day at dusk he spotted a crust of some yellowish granules on the peat. He was thrilled to recognize it as something very special and went on to describe it in 1960 as Lecidea (now Placynthiella) oligotropha. In these early days, Jack often travelled long distances by bicycle, one evening cycling from the museum to Kettering, a distance of 82 miles, arriving just before midnight. His first published lichenological contribution appeared in 1954; it was of some records from Bookham Common, Surrey, a site owned by the National Trust and now a National Nature Reserve. He was able to reach this site by train, an important factor as he did not learn to drive until much later in life, and the reserve was just over the bridge from the station platform; he developed a long-term interest in its changing lichen communities, on which he continued to publish for much of his career. In 1956, he published a survey of the lichen communities in his home county of Northamptonshire which was especially significant in being the first application of the Scandinavian method of characterizing lichen communities in the UK; amongst these was a description of the new federation Conizaeoidion, then predominant throughout much of lowland Britain.

On 16th January 1961, he was transferred back to lichens at his own request, to work under the supervision of Peter James who was Head of the Lichen Section created in 1955. He was especially keen to work on the taxonomy of a most difficult group, the sterile crusts, and pursue his interests in lichen ecology. At weekends from 1956, he started to study London’s lichens in his spare time, which resulted in detailed papers in 1967 and 1970. The lichen communities in London were then extremely impoverished due to the effects of sulphur dioxide air pollution, with no Flavoparmelia caperata and Parmelia sulcata found only on a wall at a single site. He mapped the distribution of several species in the city in relation to sulphur dioxide isopleths, the first time such maps had been produced in Britain. His careful studies on lichens on churchyard memorials demonstrated the phenomenon of relict lichen communities, where species persisted on older memorials but failed to colonize newer ones. These pioneering studies formed a basis for research documenting the return of lichens to urban areas following dramatic falls in pollution levels, including one of Jack’s last publications on lichens invading the city of London which appeared in 2012.

Jack played a significant part in the development of the British Lichen Society. He was a founder member, attending the inaugural meeting on 1st February 1958. He became editor of the British Lichen Society Bulletin in 1963, an office he held until 1979, writing and illustrating it almost single-handedly. He also took over from Arthur Wade as Honorary Secretary in 1964, meticulously executing this job for 19 years until he was elected President for 1984–1985. He was elected an honorary member of the Society in 1988, and also received the Ursula Duncan Award in recognition of these services in 2007. Jack was a regular attendee of British Lichen Society Field Meetings in the early years, and also of the Kent Field Club’s Wall-Tours. He was always keen to help emerging lichenologists, carefully naming or checking specimens sent to him at the Museum for verification. He also edited The London Naturalist from 1971 until 1979, and the Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Botany Series from 1977 until 1990. Jack was a life member of the Museums Association, having passed the diploma in 1957, and was proud to be awarded a fellowship (FMA) in 1972.

In the Lichen Section, he painstakingly curated the Acharius collection from 1962 to 1963, the specimens being coated with dirt and soot before careful cleaning. He published four major papers on sterile lichens: corticolous crusts in 1963, Chrysothrix in 1981, Leproloma in 1989, and Lepraria in 1992. Aware of the potential of chemical characters and the need to identify the compounds responsible for responses to reagent tests, he and Peter James visited one of us (DLH) at the University of Leicester to learn the mysteries of thin-layer chromatography which he helped establish at the Museum. Jack published over 150 articles in total, as well as accounts of six genera, including Caloplaca, in The Lichen Flora of Great Britain and Ireland (1992). Jack together with his wife translated and revised the German lichen text of H. Martin Jahns’ Collins Guide to the Ferns, Mosses and Lichens of Britain and North and Central Europe published in 1983. He also wrote a popular book Lichens, illustrated with his own photographs, for Shire Natural History and published in 1986 (also reprinted in 2001). The lichen Lepraria jackii was named in his honour in 1992, and the chemicals jackinic acid and norjackinic acid were described in 1995.

A life member of the International Association for Plant Taxonomy (IAPT), he endeavoured to apply the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature strictly. This led to what became his most controversial publication, on Withering’s neglected lichen names (Laundon (1984)) which resulted in his changing the names of 16 well-known lichens. At that time it was not possible to conserve names in species rank unless of major economic importance, and the familiar replaced names came to be mischievously described as having been ‘jacked’. Jack’s paper contributed to the provisions being changed to permit any species name to be proposed for conservation by the International Botanical Congress in Berlin in 1987. Even in 2005 the paper was still, however, described as ‘notorious’ (Ahti & DePriest Reference Ahti and DePriest2005).

The Museum was entering a period of dramatic change in its organization and focus as the 1980s came to an end, and on 23rd April 1990 it was restructured to concentrate on research related to the environment and human well-being rather than on identification work. Ten posts were to be lost in the Department of Botany and sadly Jack was faced with compulsory early retirement at the age of just 56, leaving the Museum in September 1990. He published a ‘whistle-blower’ account of events (Davies Reference Davies1990), as a result of which the staff were told that he was to be banned from the Museum, although that did not actually come into effect. After that time, when he did require library and other facilities for his on-going research he used those of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

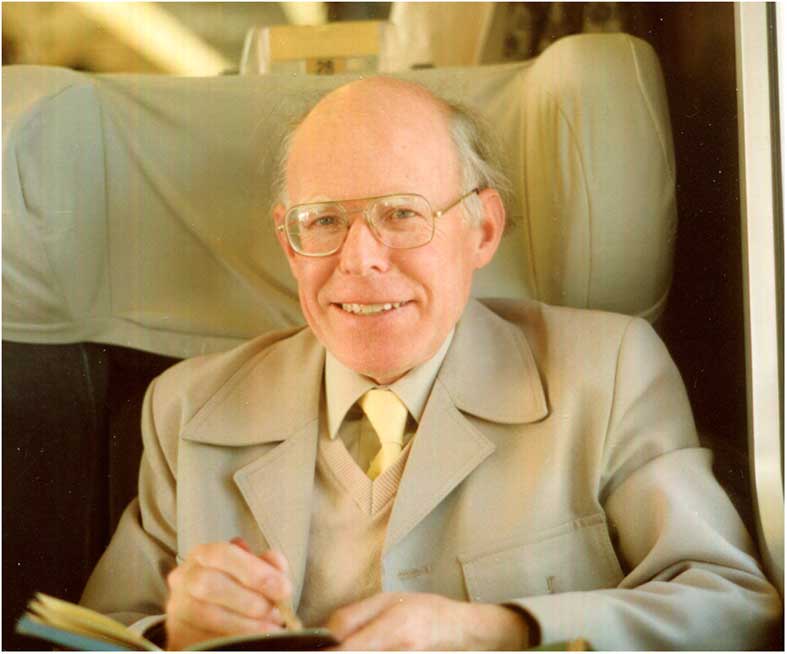

Considering that he had no university degree and had no formal training in taxonomy, his achievements are particularly impressive. He was always smartly dressed, invariably with a soft flat cap on field excursions. He had a reputation for being honest and reliable, and all he did was executed meticulously – and at his own pace. He spoke his mind and was not afraid of authority but was somewhat retiring with colleagues, avoiding congresses and meetings overseas. Even on field meetings he preferred the company of his wife to that of other lichenologists. He was, however, always helpful when approached for information and opinions, as many, including ourselves, can testify. Indeed, it was Jack who was instrumental in persuading one of us (MRDS) to join the British Lichen Society and to giving a lifetime, as did Jack, to a fascination with lichenology and to the Society.

In 1958, he married Rita June Bransby, who he nursed for two years before she died of leukaemia in 2003. Jack had a lifelong connection with Kettering, purchasing a second home there in 1999 and dividing his time between London and Kettering from that point onwards. He renewed his interest in Northamptonshire local history, researching and publishing several articles there. He remained active until mid-December 2016, despite his declining health, and died on 31st December 2016, aged 82, also from leukaemia, having elected not to receive chemotherapy. Following a celebration of his life at St Lawrence Church, Morden, on 26th January 2017, he was interred with his wife at Merton and Sutton Joint Cemetery. His only sibling, Geoffrey (Gillian) F. Laundon, an accomplished mycologist specializing in rust fungi, died in New Zealand in 1984 when only 46. Jack is survived by his daughter Jenny and grandson Matthew, of whom he was very proud.