After its outbreak in Wuhan (China) in late 2019, the new coronavirus was first detected in Italy on 30 January 2020. The following day, the Italian government – comprising the ideologically ambiguous 5 Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle, M5S), the moderate-left Democratic Party (Partito Democratico, PD), the left-wing Free and Equal (Liberi e Uguali, LeU) and the centrist Italia Viva – responded by blocking air traffic with China and declaring a state of emergency. The first COVID-19 infections were registered in the second half of February. So-called ‘red zones’ were enforced in a number of municipalities in northern Italy (mostly in the Lombardia and Veneto regions), until the spread of the virus went out of control and a full national lockdown was imposed on 9 March. Italy was the first European country to enforce a hard lockdown on its population and report a dramatic toll in terms of coronavirus-related deaths (see Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart2022). For several reasons, the Italian management of the crisis – through inevitable trial and error – provided a benchmark for other EU member states. So while there is a temptation to frame COVID-19 as an opportunity for the populist radical right (PRR) (Katsambekis and Stavrakakis Reference Katsambekis and Stavrakakis2020; Wondreys and Mudde Reference Wondreys and Mudde2022), due to their ability to capitalize on the missteps of adversaries and/or to use the pandemic to feed public resentment, much of this potential effectively rests on whether these parties sit in government or not (Bobba and McDonnell Reference Bobba and McDonnell2016; Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart2022). Fundamentally, Italy provides instances of both.

The Conte II government (September 2019–February 2021) roughly defines the political contours of this article. For as long as the Conte II government had been in power, the PRR – including Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d'Italia, FdI) and the League (Lega) – provided a common opposition front at the national level (Albertazzi et al. Reference Albertazzi, Bonansinga and Zulianello2021). But the crisis surrounding COVID-19 has given unprecedented relevance to regional ‘governors’ and the subnational level. The League's status of leading force in key regions affected by the outbreak of the pandemic (e.g. Lombardia and Veneto, the party's regioni-vetrina, or ‘showcase-regions’) especially prompts a reflection on PRR responses at different levels and the extent to which policy legacy might affect their management of the crisis (Capano Reference Capano2020). Italian PRR parties found themselves, at the same time, in a position di lotta (‘of struggle’, to denote their role in opposition) and di governo (‘of government’).Footnote 1 We are therefore led to focus on the national and subnational levels as concomitant arenas of government and opposition.

While recent regional elections have offered room for reflection on the state of Italian politics (Tronconi and Valbruzzi Reference Tronconi and Valbruzzi2020; Vampa Reference Vampa2021), very little research has taken the activity of the PRR at the subnational level to heart (cf. Paxton and Peace Reference Paxton and Peace2021). This contribution thus sets to explore how PRR parties performed (during) the COVID-19 crisis, nationally as well as regionally. Questions related to PRR responses to the crisis, their framing of the pandemic and the blame game surrounding it, and the increasing or decreasing popularity of these parties inevitably vary according to the different arenas taken into account. While populists might incite and exacerbate crises for their own advantage (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2015; Taggart Reference Taggart2000), the pandemic is interpreted here as background context (Kriesi and Pappas Reference Kriesi and Pappas2015) in which parties defined problems, prospected solutions, and ultimately saw their fortunes sway. The article therefore advances interpretations of the main questions of this Special Issue – regarding the responses, frames and popularity of the PRR – looking at the agency of respective party leaderships.

The article starts off by clarifying the political premises of this crisis, identifying the relevant PRR parties in Italy and broadening the discussion to the type of crisis that unfolded from early 2020. After mapping the role of the PRR at the national and subnational levels, this contribution addresses how this party family performed during the first year of the pandemic and across different levels of governance. The picture we get is one of varying strategies and fortunes for the PRR. While the PRR did not collectively alter its popularity during the crisis, the power balance within the right-wing bloc has shifted considerably. The leader of the League, Matteo Salvini, seemed at a loss in the first year of COVID-19. Instead of propelling its fortunes in opposition, and thus serving as an opportunity, the pandemic has shown some limits in the League's ‘national winning formula’ and exposed the first cracks in Salvini's leadership. FdI has been the main beneficiary of the League's decline in the polls. Overall, the PRR performed crisis differently depending on the opportunities that respective leaderships were able to reap at the national and subnational levels – opportunities that were also facilitated by the different organizational configuration and trajectories of the two parties. We are therefore compelled to think of the PRR as a composite and less-than-unified party family, which can stage multiple acts according to changing contexts and circumstances.

The PRR and the coronavirus pandemic in Italy

The entrenchment of populism in the Italian party system is neither a novelty nor a surprising fact (Tarchi Reference Tarchi2015; Verbeek and Zaslove Reference Verbeek and Zaslove2016). For two decades since the mid-1990s, Silvio Berlusconi's parties (Forza Italia and the People of Freedom) represented the gravitational centre of both Italian populism and the right-wing bloc. Riven by several scandals and trials, but above all incapable of designating an heir to his personal political enterprise (McDonnell Reference McDonnell2013), Berlusconi has progressively lost electoral weight within the right-wing bloc to the benefit of the PRR League, tilting the balance of the bloc further to the right (Passarelli and Tuorto Reference Passarelli and Tuorto2018). The sweeping electoral results of the M5S in the 2013 and 2018 general elections, however, testify that the decline of ‘Berlusconism’ and ensuing political changes have not affected the resilience of populism in the Italian party system.

The 2018 election delivered a strong mandate for the M5S, which gained 32.7% and 32.2% of the vote, respectively, in the Chamber of Deputies (lower chamber) and the Senate of the Republic (upper chamber). The M5S has been characterized as an ideologically ambiguous populist party, with a ‘polyvalent’ platform centring on digital participation, environmentalism, anti-corruption, but also (mild) nativism and Euroscepticism (Pirro Reference Pirro2018). After three months of negotiation talks, the M5S and the League teamed up for an ‘all-populist’ government with M5S-nominee Giuseppe Conte as prime minister (PM).Footnote 2 The Conte I government (June 2018–September 2019) ostensibly converged on a common ground of Euroscepticism and nativism as well as selected trademark reforms such as the citizens' income (M5S) and early retirement (League) schemes. Among notable policy reforms in a nativist direction, the Conte I government hardened anti-immigration laws (the ‘Salvini Decree’ on immigration and security; see Geddes and Pettrachin Reference Geddes and Pettrachin2020).

In late summer 2019, the coalition between the M5S and the League came to a bitter end. At that point, the League had emerged victorious from the European Parliament election held in May (first party with 34.3% of the vote), prompting its leader to instigate a government crisis and call for early elections. Contrary to Salvini's expectations, the ground was laid for a new government, always led by PM Giuseppe Conte, but now supported by the M5S, the moderate-left PD and the left-wing LeU. Almost overnight, Conte thus went from presiding over a M5S–League government with evident right-wing overtones (Conte I government, 2018–2019) to heading a M5S–PD–LeU government with a somewhat enhanced social-democratic appeal (Conte II government, 2019–2021). Salvini had singlehandedly relegated his party to parliamentary opposition.

What parties?

By the time coronavirus broke out in early 2020, Italy had two relevant PRR parties sitting in opposition at the national level: FdI and the League (Taggart and Pirro Reference Taggart and Pirro2021). FdI draws on the legacy and personnel of the right-wing National Alliance (Alleanza Nazionale, AN), the national conservative party heir of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement (Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI). AN dissolved in 2009 to join the People of Freedom (Popolo della Libertà, PdL) alongside Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia. FdI emerged as a split from the PdL at the end of 2012, just months before the latter officially dissolved. The party is led by Giorgia Meloni, who has a pedigree of militancy in the youth section of the MSI (Fronte della Gioventù) and then as head of the AN youth section (Azione Giovani). She served as minister of youth (2008–2011) with Silvio Berlusconi as PM. It is an open secret that FdI seeks to fill the void left by AN in Italian politics – in part ideologically (given the symbolic and organizational continuity, with a sizeable presence of former AN personnel in the party organigram), but also electorally, in an attempt to attract those voters left orphaned by the dissolution of the chief national conservative party of the Italian right.

Ideologically, FdI did not start out as a PRR party. At first, it presented itself as a ‘nationalist centre-right party’ concerned with socioeconomic and moral issues, without notable traces of populism in its discourse. By 2014, populist, nativist and Eurosceptic elements became more prominent in the agenda of the party and FdI now squarely qualifies as PRR. FdI, however, kept a strong commitment to social conservatism, family policies and the defence of small and medium enterprise, bearing a distinct and more circumspect profile not only within the right-wing bloc, but also compared to the League. Organizationally, the party subscribes to the same ‘Bonapartist’ configuration as its historical predecessors (Ignazi Reference Ignazi1996; Morini Reference Morini, Bardi, Ignazi and Massari2007). Despite a degree of internal factionalism, moreover, FdI was never quite hampered by it (cf. Carter Reference Carter2005) and thus qualifies as strongly organized, well-led and sufficiently united. FdI returned 4.4% (Chamber) and 4.3% (Senate) of the vote in the 2018 general election. At the national level, the party had been in opposition since the start of the parliamentary term in 2018 and, thus, also during the first stages of the coronavirus crisis. At the subnational level, the party fielded candidates as part of joint right-wing tickets, but in two regional elections (Abruzzo in 2019 and Marche in 2020) was able to get its own candidates elected as governors. Hence, FdI can also be defined as a party of government at the subnational level.

The other PRR party is the League (formerly known as Northern League), the oldest party represented in the Italian parliament. Ideologically, the League has changed its breadth from being mainly a northern regionalist party to a fully fledged national PRR actor under the leadership of Matteo Salvini. Yet, the elites of northern regional branches still identify with regionalism and seem to endorse the ‘national turn’ for instrumental reasons – as long as it pays off electorally (Albertazzi et al. Reference Albertazzi, Giovannini and Seddone2018). Salvini has steered the party further to the nativist right (Passarelli and Tuorto Reference Passarelli and Tuorto2018): since 2013, the League has placed anti-immigration and Euroscepticism at the core of its agenda. Organizationally, the party has weathered several crises – above all, a €49 million fraud case that brought about the downfall of the founding leader Umberto Bossi in 2012 – but essentially remained a vertically integrated structure dominated by its Lombard leadership (Cedroni Reference Cedroni, Bardi, Ignazi and Massari2007; McDonnell and Vampa Reference McDonnell, Vampa, Heinisch and Mazzoleni2016). Salvini, himself part of the Lombard elite, is thus leading a strongly organized, well-led, but factionalized party (Carter Reference Carter2005), with a new latent fracture now centring on the national aspiration of the chairman and the northern regionalism of other party elites (Albertazzi et al. Reference Albertazzi, Giovannini and Seddone2018).

Internal divisions have remained dormant due to the recent upward electoral trajectory of the party: 17.4% (Chamber) and 17.6% (Senate) of the vote in the 2018 general election. Following this result, the League was asked to join the Conte I government until the coalition with the M5S came to a bitter end in late summer 2019. Throughout the League's stint in government, the relationship with the M5S was never celestial, but Salvini's party was able to exploit its well-rehearsed experience in government to gain the upper hand within the coalition. The League very often set the government agenda and dominated the public debate – to the point that the party improved its performance in just one year.Footnote 3 Salvini then doubled down on the prospect of an early election – from which his party would have come out as the likely winner – and left the government coalition in August 2019. This prospect, however, never materialized as the M5S coalesced with liberal and progressive parties to form the Conte II government. Through the first stages of the pandemic, the League has therefore sat in opposition alongside FdI and Forza Italia.Footnote 4 At the subnational level, the League ran as part of right-wing coalitions and has had its own regional governors in place in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Lombardia, Umbria and Veneto during the first phases of the COVID-19 crisis. The League thus also qualifies as a party of government at the subnational level.

What kind of crisis?

Having identified the relevant PRR actors in Italy, it is important to relate their fortunes and framing to the type(s) of crisis that unfolded from early 2020. On the one hand, there is a clear temptation to frame the coronavirus crisis in terms of a critical juncture, whereby circumstances ‘have brought about differential changes in institutional settings that could be difficult to alter or revert’ (Pirro and Taggart Reference Pirro and Taggart2018: 258; also Giovannini and Mosca Reference Giovannini and Mosca2021). While it is only possible to speculate on the long-term consequences of COVID-19, the unfolding of events and the response mechanisms enhanced at various levels are simply unprecedented and are likely to bear a long-lasting impact. One only has to think of the extraordinary stimulus package funded by the European Union (EU) or the collective efforts to carry out vaccinations on a mass scale. The success or failure of these measures will, in all probability, condition future decisions on health management as well as the mitigation of the economic and social consequences of similar events. On the other hand, the coronavirus crisis is essentially a health crisis with severe socioeconomic reverberations. So while the assumption is made that populists thrive in conditions of crisis (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2015; Taggart Reference Taggart2000), this time their tried and tested performance of crisis was pushed to venture into relatively uncharted waters.

In political terms, the year 2020 started out pretty much as it ended: with forceful attempts to take down the Conte II government by the opposition (above all, Salvini and his League) as well as dissatisfied members of his own coalition (Matteo Renzi's Italia Viva). The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic essentially froze prospects of a government crisis for almost a year. Despite relatively swift action by the Conte II government, Italy was by and large caught off guard in terms of crisis management (Capano Reference Capano2020). Italy was the first European country to impose a hard lockdown on a national scale on 9 March 2020, limiting movement only to work or in emergencies and closing down all non-essential commercial and retail activities. These unprecedented measures were prompted by the sudden surge of cases and coronavirus-related deaths but met with the overall favour of public opinion (Istituto Piepoli 2020) and a prolonged rally-round-the-flag effect for PM Conte. Lockdown measures were kept in place until 4 May, when restrictions were gradually lifted so as to allow movement within municipalities and the reopening of closed factories. During so-called ‘phase 2’ (between mid-May and mid-June), shops, bars and restaurants reopened. By mid-June 2020 (i.e. beginning of ‘phase 3’), several standing limitations were revoked or attenuated. Lockdown measures had proven successful in containing the spread of the virus; the monitoring of new cases and related deaths over the summer gave encouraging signs about the management of the pandemic. Travel restrictions and new rules on outdoor gatherings were, however, introduced in August amid rising contagion. In October, PM Conte announced new emergency measures intended to last until 31 January 2021, entailing restrictions on indoor and outdoor gatherings. Limitations were further enhanced to define a national curfew and three tiers to be enforced at the regional level (yellow, orange and red, depending on the R number, which measured the spread of the virus, and other criteria such as capacity of intensive-care beds). As the second wave broke out in autumn and new lockdown measures were introduced, the number of COVID-19 cases reached new heights. In just four months (September–December), coronavirus-related deaths totalled those recorded between February and August 2020 (i.e. over 35,000).

Between March 2020 and January 2021, the Conte II government approved five major packages to rescue and kickstart the Italian economy (i.e. ‘Heal Italy’, ‘Relaunch’, as well as three other decrees in August, October and January) worth a total of €142 billion (IMF n.d.). After lengthy and tense discussions at the EU level throughout the summer, Conte secured a sizeable share of the €750 billion European recovery fund (‘Next Generation EU’), amounting to almost €209 billion (of which €81.4 billion was in grants and €127.4 billion in loans).

The government's inability to define a sound expenditure strategy, however, prompted friction within the coalition and led to its eventual demise. The technocrat-led Draghi government, inaugurated in February 2021 after yet another political crisis, provided enough reassurances on the appropriate spending of EU funds. At least, this is what the almost unanimous party approval of his government seemed to suggest. Only FdI, a dissenting faction of the M5S, and a portion of Italian Left (Sinistra Italiana) – the latter, part of LeU – voted against the Draghi government. From February 2021, the PRR FdI was the only relevant opposition force sitting in parliament.

In government and opposition: the PRR in different arenas

As COVID-19 broke out in early 2020, ‘the virus and its spread monopolized the attention of news broadcasters to the exclusion of almost everything else, and the opposition parties were under pressure to ensure that criticisms were constructive’ (Newell Reference Newell2020: 109). This section therefore engages with the two PRR parties presented so far – FdI and the League – to see whether their role in opposition at the national level could in any way be framed as constructive and assess the payoffs of these strategies. By looking at their discourse and performance at the national level, this article seeks to outline the responses to the pandemic by FdI and the League, especially whether they were supportive of the measures implemented by the Conte II government or not. It casts light on the framing of the pandemic by the PRR, and whether and how the expected demonization and scapegoating strategies of these parties were revealed in their discourse. And it finally addresses the consequences of the pandemic in terms of popularity and electoral support for FdI and the League.

The changes that occurred in Italian politics during the 2019–2020 cycle present us with a complex interaction between national and subnational politics (De Giorgi and Dias Reference De Giorgi and Dias2020; Tronconi and Valbruzzi Reference Tronconi and Valbruzzi2020). The League, which came out of the 2018 general election as the main force of the right-wing bloc, and then as the most voted-for party in the 2019 European Parliament election, found itself at the helm of several Italian regions alongside its fellow coalition members FdI and Forza Italia. Some of these regions were led by League-affiliated governors, as in the case of Lombardia and Veneto. The different roles in the national and subnational arenas offer us an unprecedented opportunity to examine the changing strategy and fortunes of the PRR between government and opposition (Bobba and McDonnell Reference Bobba and McDonnell2016), but also consider subnational politics as an arena marked by personalization and responding to its own logics (Vampa Reference Vampa2021). The two arenas of PRR activity are presented in turn in the following subsections. For reasons of space, the focus on the subnational level is limited to the northern regions of Lombardia and Veneto.Footnote 5

Between 2020 and 2021, Lombardia and Veneto were governed by League-affiliated presidents – respectively, Attilio Fontana and Luca Zaia. The two regions have been frequently framed as success stories of subnational governance by the party. At the same time, they are among the most affected by the pandemic in absolute numbers and present us with rather different health systems as well as modes of crisis management. At least during the first wave of COVID-19, Veneto responded well to the COVID-19 challenge; Lombardia's answer was conversely quite poor and punctuated by missteps. The differences between regional health systems should be in part attributed to the fact that regional governments enjoy significant autonomy in Italy (Terlizzi Reference Terlizzi2019); even a global challenge like COVID-19 can result in differential responses at the regional level. In particular, Lombardia traditionally valued hospital structures but relied on the externalization of services to the private sector, whereas Veneto invested in public health and territorial assistance. These different regional models resonate with the antithetical approaches to the coronavirus crisis and in good part with a legacy of prior policy decisions (Capano Reference Capano2020; Casula et al. Reference Casula, Terlizzi and Toth2020) – in these specific cases, by previous League administrations. Therefore, the two regions offer the opportunity to reflect on the policy legacy of PRR subnational government and the agency of the League.

The article draws on 2,322 news media entries retrieved from the Factiva database, which are used to assess and reconstruct PRR responses, frames and popularity in the first year of COVID-19. Print media sources were deemed particularly well suited to delve into these three aspects and tackle visible interactions between government and opposition actors (e.g. Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Hutter and Bojar2019). Sources include the print version of the main general-interest (Corriere della Sera and la Repubblica) and business (il Sole 24 Ore) daily newspapers. The time range of the analysis spans 20 January 2020 to 15 January 2021.Footnote 6

The national arena: populist radical right di lotta

The first wave of the crisis was characterized by greater diversity with regard to the responses to the pandemic – most certainly compared to the second wave in autumn 2020. The League's initial reaction to government policies was rather erratic. At first, Salvini urged people to flood bars and discos, in order to counter the perception of Italy as the ‘lazaretto of Europe’; and to reopen small and medium enterprises affected by restrictive measures because the country needed to get back on its feet. In just a matter of days, however, the League's secretary changed its position on the emergency and mounted attacks to the government for its inability to act sooner and more effectively. COVID-19 was used as an excuse to seal Italian borders and blame migrants for potential sources of contagion.

Towards the end of February, Salvini openly called for the suspension of the Schengen Agreement and a halt to immigration from Africa as core objectives to stop the spread of the virus and defend the Italian population (Corriere della Sera 2020). But while the health crisis was somehow minimized and expected to be soon brought under control, the leader of the League invoked swift action to remedy economic repercussions. For example, the EU was called on to intervene to provide adequate financial support to the Lombardia region and the province of Brescia. The incapacity of the government was itself used as a pretext for Conte's resignation.

Amid initial uncertainty surrounding the magnitude of the crisis, FdI swayed from cautiousness to optimism and back. One day the global emergency required ‘seriousness, judgement, and firmness’ (Isman Reference Isman2020). The other, party leader Meloni was storming the Internet with a video exhorting tourists to come to Rome – for life had been proceeding as usual in the Italian capital.Footnote 7 Similar to Salvini, Meloni was also ready to take down Conte with a vote of no confidence. But amid the growing gravity of the situation, FdI was alive to prospects of cooperation with the government and showed a responsible and proactive profile (Di Caro Reference Di Caro2020). Ultimately, both PRR parties approved the first decree on the coronavirus emergency, which focused on measures to counter the spread of COVID-19.

This was virtually the PRR's first and only attempt at cooperation with the Conte II government. Throughout the first year of the pandemic, PRR parties engaged in various forms of outbidding and irresponsible opposition, always lamenting Conte's unwillingness to get them involved. The League's erratic position on rescue packages is best exemplified by Salvini's compulsive criticism of funds allocated. The first package approved by the government, totalling €3.6 billion, was dismissed as ‘peanuts’. Each day the League's leader would ask for more – 20, 30, 50 billion euros – well aware of the budget constraints (then still in place) publicly acknowledged by Conte, and that the League's opposition status would grant him free rein to double down without pressure to deliver.

Looking at their framing of the pandemic and the management of the crisis, FdI and the League placed government criticism at the heart of their discourse. At least during the first wave of the crisis, concerns related to immigration were relegated to a secondary role. The reason for this is quite straightforward; the draconian measures adopted regarding movement and travel deprived the Italian PRR of one of its trademark issues.Footnote 8 Conversely, a populist anti-government frame took centre stage in their performance of crisis. Socioeconomic issues also rose to prominence in their discourse. True to their right-wing positions on the economy and their support for small and medium enterprise, the League has been remarkably consistent in advocating a nationwide tax amnesty, whereas FdI called for tax cuts and measures to help the self-employed. Without hesitation, both FdI and the League were willing to overcome the Fiscal Compact to allocate resources and tackle the economic effects of the crisis.

COVID-19 also boosted the Italian PRR's Euroscepticism. Especially at the beginning of the crisis, the EU looked unqualified to address the pleas of the Italian government. At first, the European Central Bank chief Christine Lagarde claimed no responsibility in closing bond spreads of eurozone members (Stirling Reference Stirling2020), fuelling the image of distant and unresponsive supranational institutions. The president of the European Commission (EC) Ursula von der Leyen promptly set the record straight, stating that maximum flexibility would be granted to Italy. At the same time, Lagarde vowed to support affected economies throughout the whole length of the crisis.

In response to these quandaries, Salvini spoke of a ‘deafening silence’ from the EU and speculated about other European countries taking advantage of the pandemic to mount a trade war on Italy (Sole 24 Ore 2020). In one of her parliamentary addresses, Meloni was not short of criticism either:

The Europe we once dreamed of no longer exists: the civilized Europe, the Europe of solidarity, the Europe that is a mother to us all. What we have seen is a Europe of selfishness, of the interests of some at the expense of the rights of the many. It is the Europe that waits for the earthquake to take place in our own backyard in order to dig through the rubble and make off with the silverware. (Meloni in Newell Reference Newell2020: 109–110)

As talks moved forward between the Italian government and the EC, one of the proposed solutions to tackle the crisis resulted in a European Stability Mechanism (ESM) loan. The principled opposition surrounding ESM conditionality triggered a mantra of ‘no to ESM’ among PRR parties.Footnote 9

The measures adopted by the Conte II government were rebuffed by the whole right-wing bloc. The first substantive package approved by PM Conte just before Easter (‘Heal Italy’) was framed by the leader of the League as a ‘joke for the millions of Italians who won't see a cent’ (Salvini in Patta Reference Patta2020). FdI lamented again its lack of involvement in decision-making, despite its claimed proactive attitude and the proposals put on the table. It is around this time that the two PRR leaders steered their parties in somewhat different directions, in no small part due to their shifting fortunes in popularity.

By early April 2020, Matteo Salvini started pressing for early reopening. He proposed to open churches for Easter – an idea quickly dismissed by Pope Francis himself. The leader of the League aimed to put the government under further pressure and impose his own timing to the management of the pandemic. Salvini demanded the reopening of all businesses and of Lombardia, the region most affected by the pandemic. He embarked on a mission to set the Italian people free from the ‘cages of lockdown’ imposed by the ‘government of terror’. Meloni upheld a somewhat warier profile and, while longing for a return to normality, she started differentiating her strategy from the League's. At the rhetorical level, the priority for FdI remained the safety of people and businesses. She decided to turn to the streets and carve out a niche for herself outside the institutional arena. She first resurfaced publicly for an anti-government flash mob in front of the seat of the Chamber (28 April) and was the main driver behind the first collective event organized by the right-wing bloc on the Day of the Republic (2 June).

Both party leaders argued that the economy would be the real casualty of coronavirus. But while Meloni seemed keen to invest in public events, she was never caught off guard and always appeared in public wearing a mask. The leader of FdI calibrated her strategy so as to deliver a responsible profile. While she publicly defied the government, she hardly questioned the seriousness of the pandemic. The leader of the League, on the other hand, tended to ignore safety protocols in contempt of both the government and the virus. The different posture of the two leaders is best exemplified by their behaviour at the 2 June demonstration in Rome. At the end of the event, Meloni and her party delegation, who had mostly complied with safety measures, simply left the premises. Instead, Salvini hung around to take selfies with supporters (a trademark of his politicking), taking his mask down. This illustrates Salvini's trivialization of COVID-19 as well as his craving for public contact and exposure. He was seeking a ‘return to normality’ not only with regard to the pandemic but also to the political life of the League: ‘The League is the only political movement that lives among the people. … If you close down the squares and factories for three months, you take vital space away from the League’ (Salvini in Lopapa Reference Lopapa2020).

The public debate over the summer was monopolized by the upcoming regional elections and the Conte II government's efforts to undo the nativist measures adopted by the previous Conte I government. The government proposal of a short-term regularization of migrants to tackle shortages in the agricultural labour force seemed to respond to a similar logic. This plan was intended to redress one of the side-effects of COVID-19, but marked a watershed in the politics of the Italian PRR. It helped FdI and the League return to their familiar ideological turf (i.e. anti-immigration), offering them additional ammunition to criticize the government. Salvini framed this provision as a ‘prize to illegality’. Migrant populations were later depicted as ‘dangerous for public health. While Conte dismantles security decrees and opens up the ports, NGOs take migrants positive to coronavirus to Italy. This government is putting Italy in danger’ (Salvini in Ziniti Reference Ziniti2020).

The indecisiveness surrounding the post-lockdown phase eventually led to the outbreak of a second wave. New restrictive measures followed in autumn 2020 and through the December holidays, which were predictably criticized by the PRR. FdI and the League once again blamed the government for incompetence and immobility as well as for the chaotic handling of the crisis. Unlike during the first wave, however, a morbid familiarity with the state of emergency had supplanted the frantic search for solutions by the government and the quest for relevance by the opposition. The political dynamics during the second wave of coronavirus were thus largely uneventful, with the two PRR parties keeping up with their attacks on the Conte II government and lamenting their continued lack of involvement in decision-making. This lasted until PM Conte's resignation on 26 January 2021.

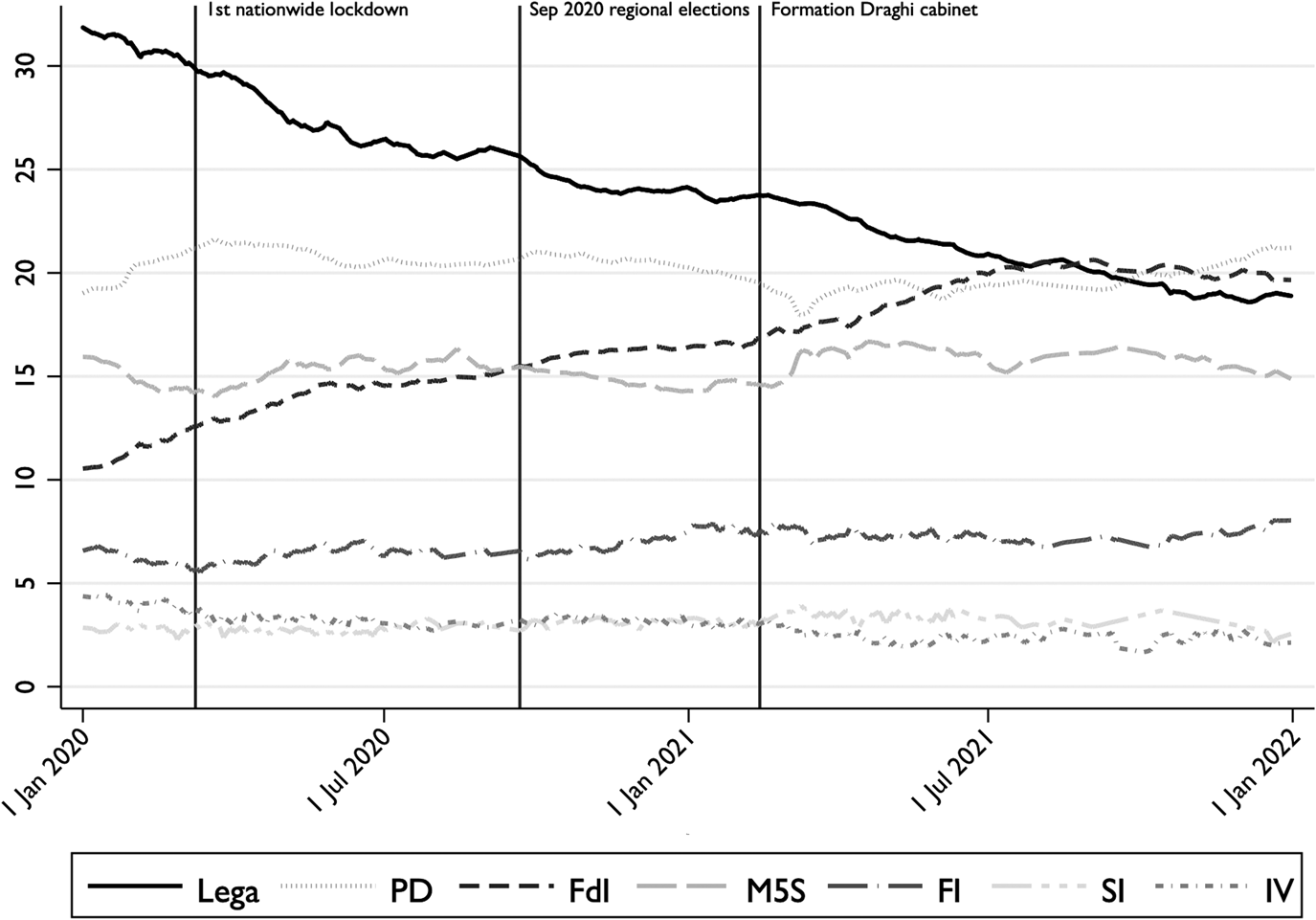

In terms of popularity, the League lost momentum during the first year of COVID-19, dropping well below the performance of the 2019 European Parliament election (34.3%). FdI, conversely, experienced an upward trajectory, gaining ground compared to the European election (6.4%). Figure 1 shows that, between January 2020 and January 2021, the League went from about 32% to 24% of public support; FdI grew from about 11% to 17%. FdI's takeover was complete by the end of 2021, when voting intention for the party averaged 20% against 19% for the League. Cumulative support for the two parties had been well within the margin of error during the first year of COVID-19 (from 43% to 41%), but these figures confirm a major reshuffle within the PRR camp. While the League lost out during the first stage of the pandemic, FdI made significant inroads. As a result, since the beginning of the pandemic, Meloni has posed a credible threat to Salvini's leadership within the right-wing bloc.

Figure 1. Average Support (%) for Italian Parties, January 2020–December 2021

Source: POLITICO Poll of Polls (www.politico.eu/pollofpolls); author's own elaboration.

Note: Lega (League), PD (Democratic Party), FdI (Brothers of Italy), M5S (5 Star Movement), FI (Forza Italia), SI (Italian Left), IV (Italia Viva).

The subnational arena: populist radical right di governo

Attention now turns to the League's government in Lombardia and Veneto – two regions severely affected in terms of coronavirus cases and related deaths. The responses laid out by the governor of Lombardia, Attilio Fontana, ostensibly failed to comply with health protocols in Codogno (Lodi) – the first European town to be placed in lockdown over the coronavirus. The ill-fated decision to use nursing homes as COVID-19 units then led to the outbreak of the virus and eventual death of several residents of the institutions. These episodes sparked a prolonged blame game between the central government in Rome and governor Fontana (Piccolillo Reference Piccolillo2020), later ending in an official inquiry into whether the responsibility for establishing a ‘red zone’ in the early phase of the crisis rested on the national or subnational government (Post 2020). At the discursive level, the situation in Lombardia and the modest measures initially enforced by PM Conte reignited the League's original leitmotiv of antagonism between the productive north – now in need – against the undeserving central government.

As the emergency continued, Lombardia was able to expand the capacity of intensive-care beds (with the aid of the central government) and set up a field hospital in Milan provisionally worth €21 million and funded through private donations.Footnote 10 Amid calls for early reopenings, Fontana was embroiled in an alleged case of fraud regarding the purchase of €513,000 worth of surgical gowns from his brother-in-law's company. The regional governor dismissed the case as a ‘misunderstanding’ and was later acquitted. The regional government, however, did little to prevent and contain the spread of the virus after the first lockdown. In absolute numbers, Lombardia remained the most affected region in Italy through the second wave of the virus too.

Luca Zaia's early handling of the crisis in Veneto was very different from Fontana's. Upon the outbreak of coronavirus in Vo’ (Padua), Zaia quickly set up a taskforce aided by the Civil Protection Department and researchers from the University of Padua. The advice of Professor Andrea Crisanti was instrumental to test and trace the whole population of Vo’, securing reagents for PCR tests at a time of shortage of supplies, and purchasing a device able to process 9,000 tests per day. During the first wave, Veneto had tested 6.7% of the population as opposed to the 3.5% of Lombardia (Casula et al. Reference Casula, Terlizzi and Toth2020), showing the regional government's proactiveness in going after the virus (Vecchio Reference Vecchio2020).

The initial success story of Veneto was also crafted through communication and strategy. Zaia held press conferences for 130 consecutive days, giving the impression of beating coronavirus almost singlehandedly. The effective management of the crisis gave new impetus to the long-standing debate on regional autonomy – an issue dear to Bossi and old-fashioned League members – overall helping Zaia uphold traditionally high support rates (Porcellato Reference Porcellato2017) and secure a third consecutive mandate (76.8% of the vote) in the September 2020 regional election. A change of approach, however, occurred between the first and second waves. In the latter phase, Zaia pushed for an increase in the capacity of intensive-care beds and gave priority to cheaper antigen over more expensive PCR tests, which seemed to respond to a coherent logic: keeping the costs down, the number of cases low and, ultimately, businesses open. With such strategies in place, Veneto generally managed not to move into the ‘red tier’ of higher restrictions despite a rise in cases.

Looking at the intersection between national and subnational politics, the initial success of Zaia over the virus and his subsequent triumph in the Veneto regional election in September propelled a media narrative on Salvini's precarious hold on party leadership. Although this framing contravened the leader-centric nature of the League, it ostensibly reignited the national versus northern regionalist internal ideological divide and seemed to undermine its Lombard gravitational centre at the organizational level.Footnote 11 Salvini himself invested much effort in endorsing and defending the governor of Lombardia despite Fontana's several missteps, while remaining silent over the successful management of the coronavirus crisis in Veneto by a leading exponent of the ‘old League’. Throughout 2020, the governor of Veneto was portrayed as the League's golden boy and a suitable successor as party secretary. Both Salvini and Zaia downplayed such prospects, but disputes over two different conceptions of the League (northern regionalist vs nationwide PRR) are and will remain salient for some time to come. In the meantime, the coronavirus crisis provisionally took a toll – not so much on the Italian PRR as a whole, but on Matteo Salvini's leadership.

Discussion and conclusions

The Italian party system has undergone several changes over the last decade. If the 2019–2020 election cycle testified the growth of the League, the coronavirus crisis exposed the first cracks in Salvini's leadership and marked a setback for its nationwide PRR project. Reflecting on PRR party responses to the pandemic, this article delved into this party family's reaction to the emergency measures, framing of the crisis and consequences in terms of popularity. The specificity of the Italian case means we needed to consider the broader PRR bloc – and thus look at FdI and the League – and account for developments at the national and subnational levels. Depending on the level considered, the PRR in Italy qualified both as a force of government and of opposition during the first year of COVID-19.

The analysis of the PRR in opposition (at the national level) evidenced common negative responses to the measures of the Conte II government. Meloni and Salvini both deemed the government unfit for the task and spared no effort demeaning and outbidding Conte's prospected remedies. But in their common intents, the two leaders essentially differed in style. Meloni has been rather consistent in her criticism but above all conveyed a resolute and more responsible self-image during the emergency. Standing at the top of a strongly organized, well-led and sufficiently united party allowed her to deliver a credible opposition stance (also aided by the continued status in opposition at the national level) with the full backing of the FdI cadre. On the other hand, Salvini has been erratic in his remarks and adherence to safety measures, also in an attempt to woo extremists and various other sceptics. The leader of the League thus appeared overwhelmed by the COVID-19 crisis at a time when he was still coping with pulling government support in summer 2019. These faux pas accentuated the inner factionalism and ideological frictions, which always animated the party, but had remained dormant in the face of electoral growth.

In terms of the framing of the crisis by the PRR, several commonalities emerged between FdI and the League. Both parties placed populist anti-government frames at the forefront of their discourse. Their status as opposition forces certainly offered them ample room to criticize the Conte II government. In light of the several restrictions in place during the first national lockdown, FdI and the League were, however, deprived of their anti-immigration trademark issue. Nativism resurfaced only at a later stage, especially in connection to the short-term regularization of undocumented migrants to deal with the shortages in the agricultural labour force. Much more persistent has been the PRR's criticism of the EU and its principled opposition to ESM loans. No relevant cases of Sinophobia were detected in the two parties' discourse, nor were there major attempts to fuel conspiracy theories over the spread of the virus.

These aspects at least in part resonate with the diverging patterns of popularity of FdI and the League after the outbreak of COVID-19 (Figure 1). While the PRR remains collectively as popular as ever with approximately 40% of public support, Salvini's party lost out during the first year of the pandemic. The League paid for the hazardous decision to leave the government coalition in summer 2019. It was then deprived of its main campaign stage (public events) and issue (immigration) by the pandemic. Meloni's party instead made significant gains, also by attracting disenchanted League supporters who rewarded her political consistency in opposition. Fast-forward to the Draghi government (since 2021), and FdI's standing has further improved as the sole fully fledged opposition force sitting in parliament.

Looking at the PRR's posture in government (at the subnational level), the governors of Lombardia and Veneto (both from the League) handled the crisis quite differently. While Attilio Fontana's response seemed punctuated by strategic errors and mismanagement, Luca Zaia initially kept the crisis under control, in no small part thanks to the advice of experts. Although their decisions were also conditioned by previous health policy choices (Casula et al. Reference Casula, Terlizzi and Toth2020), both regional governments ultimately succumbed to the pressure of keeping businesses open at all costs. This notwithstanding, Zaia's performance during the first phase of the crisis paid off. Not only did he manage a third consecutive mandate with a landslide, but also raised questions over Salvini's leadership model and vision of the League.

The varying trajectories of FdI and the League in opposition and the uneven responses of the League in (regional) government confirm that there is no one-size-fits-all answer to how the PRR is coping with COVID-19 (Manucci Reference Manucci, Katsambekis and Stavrakakis2020; Wondreys and Mudde Reference Wondreys and Mudde2022), and that it is plausible to attribute divergence in their performance of crisis to the agency of respective party leaderships and affiliated regional governors (in these cases, also aided or hindered by the long arm of policy legacy). Yet of all the wavering reactions and performances, the Italian PRR has broken even in the face of coronavirus. Only Salvini has come out weakened by the virus; it might be a long way back to the top for him in light of the possible challenges posed by League old-timers, internally, and Meloni's rising star, externally.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Igor Guardiancich, Andrea Terlizzi and Lorenzo Zamponi for the insightful discussions as well as Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser and Paul Taggart for their invaluable editorship and guidance.