Introduction

Most research regarding the early urbanisation of the Southern Levant has focused on the construction of defensive walls and public buildings. Tel Erani (Tel esh-Sheikh el-Areyni) is located on the border between the Mediterranean coastal plain and the Judean foothills, in present-day Israel (Figure 1). Excavations began there in the 1960s under the first director of the Department of Antiquities (Yeivin Reference Yeivin, Avi-Yonah and Stern1977) and have continued since, with the most recent fieldwork undertaken in 2019. These expeditions include archaeologists from Tel Aviv University, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU), the Jagiellonian University in Krakow (JUK) and the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) (Kempinski & Gilead Reference Kempinski and Gilead1991; Ciałowicz et al. Reference CiaŁowicz2015), with the support of a team from the University of Buenos Aires.

Figure 1. Location map with sites mentioned in the text (inset) (produced by A. Fadida, based on ArcGIS, Esri), with general view of Tel Erani, looking north (2015–2016 season) (courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority).

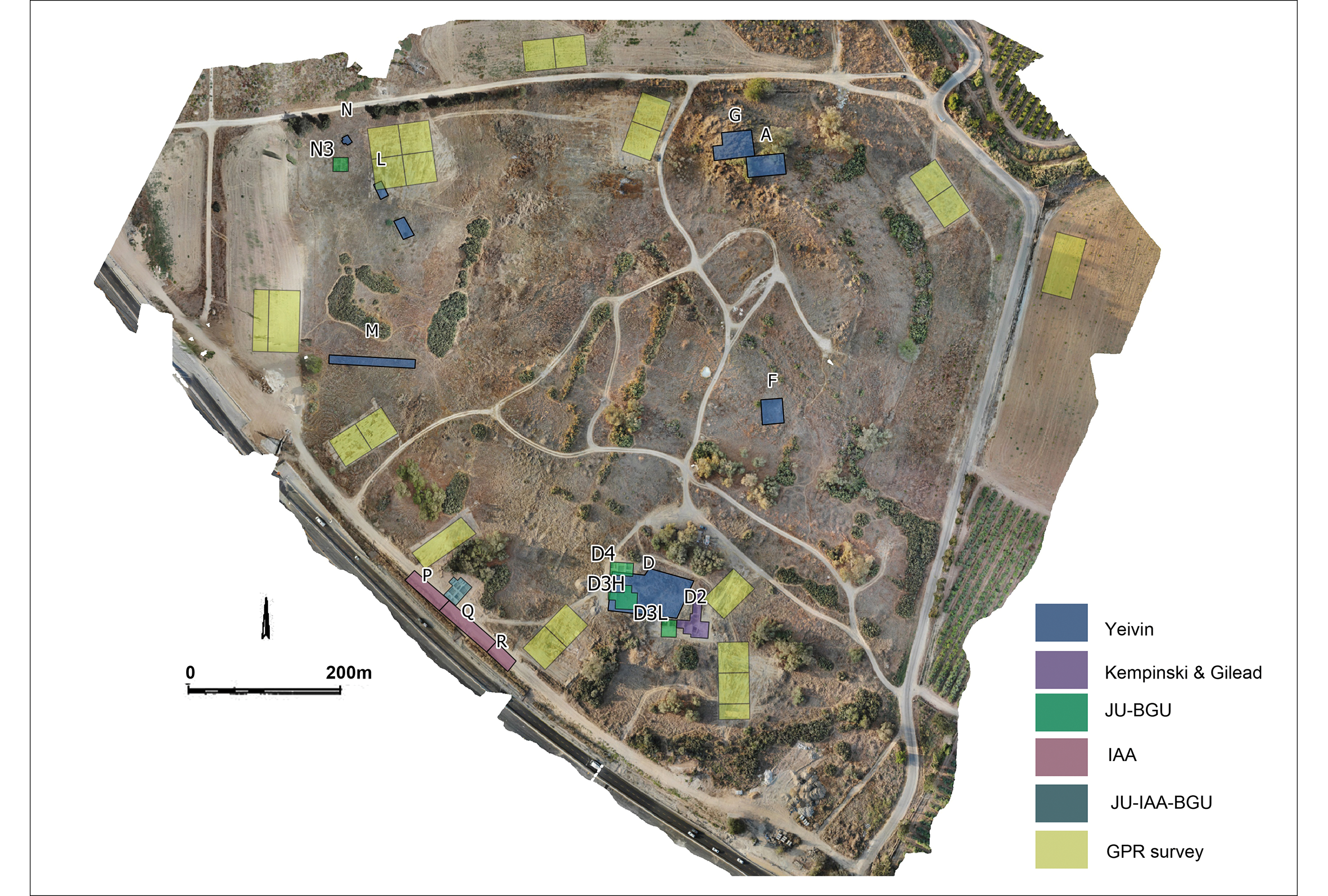

The tell comprises three main areas: the acropolis in the north, the upper terrace and the lower terrace (Figure 2). Occupying approximately 25ha, the site includes Early (thirty-fifth to thirty-first century BC) and Late Bronze (fourteenth century BC) Age, and Iron Age phases (twelfth to eighth century BC), with some remains from the Byzantine (fourth to eighth century AD) and Ottoman (sixteenth to twentieth century AD) periods.

Figure 2. Location of excavated areas. JU = Jagiellonian University; BGU = Ben-Gurion University; IAA = Israel Antiquities Authority; GPR = ground-penetrating radar (aerial image by M. Czarnowicz).

Yeivin's (Reference Yeivin, Avi-Yonah and Stern1977) excavations in Area N—one of several areas he excavated (Figure 2)—revealed the remains of defensive mud-brick walls in the north-western part of the lower terrace. These were re-excavated by a BGU/JUK team (Cialowicz et al. 2015). A salvage excavation during 2015–2016 (Milevski et al. Reference Milevski, Yegorov, Pasternak, Aladjem, Cialowicz, Yekutieli and Czarnowicz2016) revealed a new portion of the site's fortification walls. Both complexes in areas N and P-Q date to the Early Bronze (EB) IB1 (c. 3300–3100 BC), referred to as the ‘Erani C horizon’ (Yekutieli Reference Yekutieli2006) following the nomenclature of the excavation conducted by Kempinski and Gilead (Reference Kempinski and Gilead1991).

Building complexes found in Area D, excavated by Yeivin (Reference Yeivin, Avi-Yonah and Stern1977) and later Kempinski and Gilead (Reference Kempinski and Gilead1991) (Figure 3), provide some evidence for public buildings or proto palaces. These complexes were also dated to the EB IB1 based on associated pottery.

Figure 3. Public building(s) in Area D (adapted from Kempinski & Gilead Reference Kempinski and Gilead1991; Czarnowicz & Braun Reference Czarnowicz and Braun2019).

The defensive walls and the buildings in Area P-Q

The excavations in 2015–2016 revealed two defensive walls built one on top of the other; these are numbered W200 and W204 (Figures 4 & 5:1). Excavations reveal several phases of the site that pre-date the fortifications, all of which belonged to the Erani C horizon.

Figure 4. Fortification walls in Area P-Q (2015–2016 season; courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority).

Figure 5. 1) Area P-Q, view of fortification walls (2015–2016); 2) inner buildings attached to the walls (2019). JU = Jagiellonian University; BGU = Ben-Gurion University; IAA = Israel Antiquities Authority (plan drawn by E. Aladjem and M. Czarnowicz).

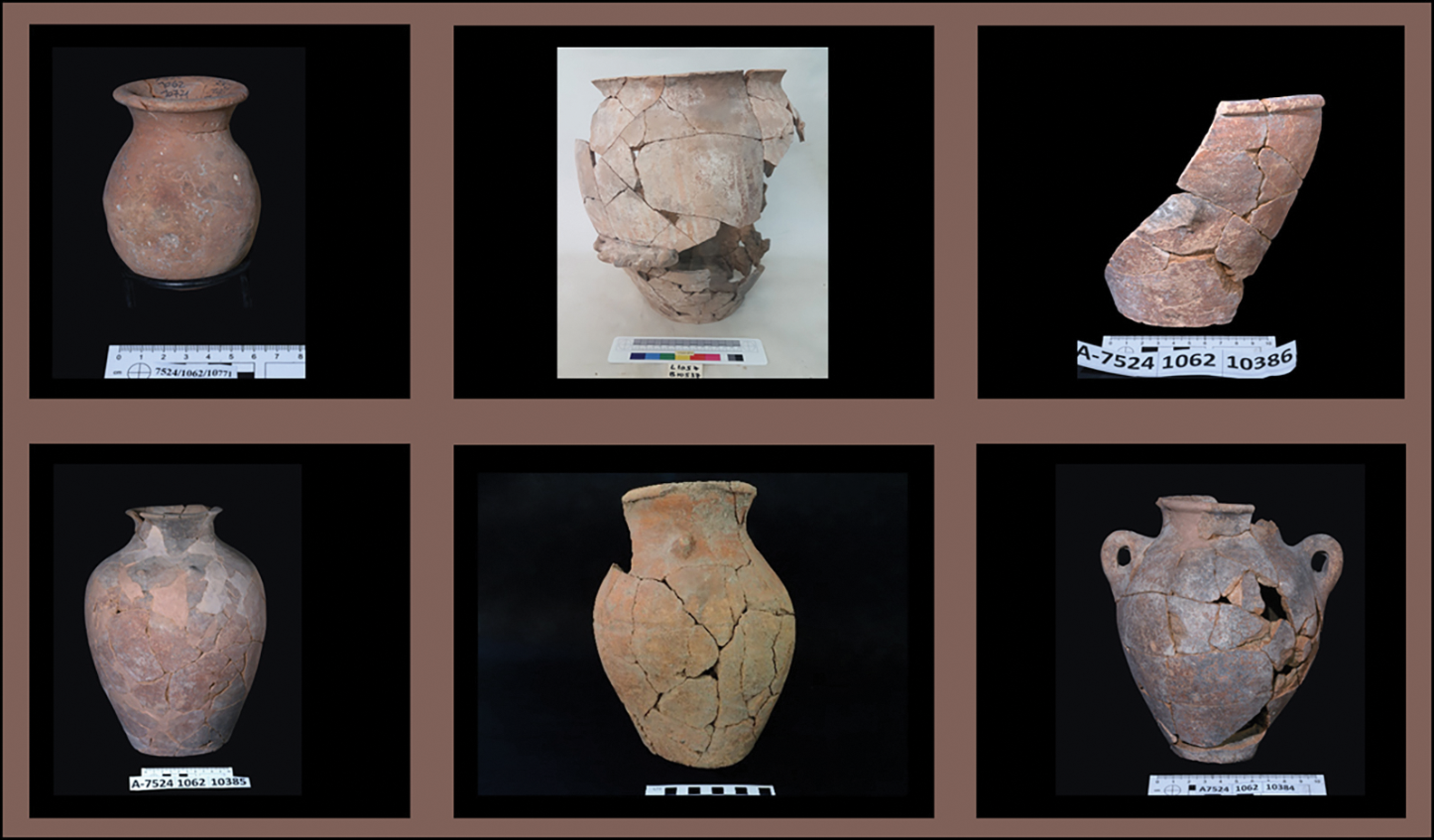

In 2018–2019, a collaborative excavation between the BGU, JUK and the IAA, along with the team from Buenos Aires University, investigated the inner part of the town in Area P-Q, within the defensive walls (Figure 5:2). Several buildings were found near or attached to the defensive walls. Two main levels were found: one early, probably attached to the inner face of the defensive walls, and with several phases; and one late, which seems to post-date the collapse of the walls. The early level belongs to the Erani C horizon—probably its late phase, according to the associated pottery (Figure 6) and a radiocarbon date from one of the floors (4491±27 BP; GrM-22786: 3348–3092 BC at 95.4%; date modelled in OxCal v4.2, using the IntCal13 calibration curve; Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2013).

Figure 6. Pottery from the Erani C horizon found in Area P-Q (photographs by C. Amit, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority).

Immediately below wall W200 was a destruction layer containing floors with in situ pottery vessels belonging to the Erani C horizon. The pottery was the same type as that found in floors of the structures inside the town (in Area P-Q) that are attached to the fortification walls.

A magnetometry survey conducted in 2019 on the edge of the lower terrace, close to areas N and P-Q, suggests that other structures existed on the north-western and southern border of the lower terrace. These are most evident in the south-east of the terrace, where the wall appears to turn northwards following the topography of the lower terrace (Figure 2).

Discussion

The excavations at Tel Erani have revealed a walled town of the early phase of the EB IB on the Mediterranean coastal plain. The town was probably connected via inter-regional exchange between the coast and the highlands of the Southern Levant (Yekutieli Reference Yekutieli2006; Milevski Reference Milevski2011). The gradually increasing occupation density and the presence of public buildings and defensive town walls suggest an early period of urbanisation and fortification in the central-southern part of the Southern Levant. This surely reflects a type of social organisation led by elite groups (see Shalev Reference Shalev2018).

Tel Erani clearly has some features associated with urbanism: public architecture, evidence for economic specialisation and trade, and dense occupation. Other criteria, such as population density, however, cannot be asserted. Early sites in the Southern Levant have some, but not all, of the attributes associated with urbanism (see Childe Reference Childe1950; Gaydarska Reference Gaydarska2016; Smith Reference Smith, Fernández-Götz and Krausse2016; Woolf Reference Woolf2020). Tel Erani appears to be at a relatively early stage of the urbanisation process in the Near East.

This process can perhaps also be observed at Tel Afek, north of Tel Aviv, at ‘Ai, near Jerusalem, and also in the north, at Ein Zippori, Tel Bet Yerah and Tel Shalem (Callaway Reference Callaway1980; Eisenberg Reference Eisenberg1996; Kochavi et al. Reference Kochavi, Beck and Yadin2000; Getzov Reference Getzov2006; Milevski et al. Reference Milevski, Liran and Getzov2014). The material culture—predominantly Erani C horizon pottery—demonstrates how Tel Erani was widely connected, with links to other sites on the coastal plain (e.g. Azor, Lod, Afridar, Barnea); the foothills (e.g. Tel Gezer Hartuv, Eshtaol, Ramat Bet Shemesh, Horbat Ptora, Tel Lachish, Amazyia); the central hill country (e.g. Tel en-Nasbeh, Jerusalem); the Jordan Valley (e.g. Jericho); the Judean desert (e.g. Nahal Mishmar Cave); and the northern Negev (e.g. Lahav) (Yekutieli Reference Yekutieli2006; Milevski Reference Milevski2011). This pottery is also evident in Lower and Middle Egypt (Czarnowicz Reference Czarnowicz and Mączyńska2014) and represents one of the first phases of Levantine interaction with the Nile during the mid-fourth millennium BC.

The following phase of Tel Erani, EB IB2, probably reflects the presence of Egyptians at the site, as evidenced by a ubiquitous presence of Egyptian finds (Czarnowicz et al. Reference Czarnowicz, Pasternak, OchaŁ-Czarnowicz, SŁucki, Jucha, Dębowska-Luwin and Kołodziejcyk2014). The connection between phase EB IB2 and the earlier Erani C horizon remains unclear, as does the relationship between the Egyptian influence and the earlier fortification walls; this is an area of future research at the site.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank field supervisors E. Aladjem, M. Pasternak and S. Atkins, along with other members of the field team: J. Regev, E. Boaretto and F. Höflmayer (radiocarbon dating), and M. Kahan, Y. Shmidov, V. Assman and A. Fadida (plans and sections). Thanks are due to students from JUK and UBA, as well as to workers and volunteers from Qiryat Gat, Ashkelon, Kfeife and Abu Kaf. Special thanks also to D. Varga and V. Lipshitz from IAA for their help during all stages of the work.

Funding statement

This fieldwork and research were funded as part of the salvage excavation by the National Roads Company of Israel, the Israel Scientific Fund, the National Science Centre in Poland and the Fund for Science and Technology (Argentina).