Figure 1.1 Graveyard of the First Hawaiian Church, Kapa‘a.

The Ship

Early on the morning of 17 June 1885, a steamship by the name Yamashiro-maru arrived in the Hawaiian port of Honolulu. A government-appointed physician boarded to carry out an all too perfunctory check of the passengers’ health – there were nearly 1,000 Japanese labourers in the steerage accommodation – before giving permission for the vessel to dock.

This book follows a single ship to explore such moments of landfall in the Asia-Pacific world.Footnote 1 The iron-hulled Yamashiro-maru may have been an unremarkable vessel in the global scheme of things, but it steamed the seas in a remarkable age. A century or so before 1885, for example, this particular arrival would have been unimaginable. Japan, according to its most famous European chronicler of the eighteenth century, was all but closed to the outside world.Footnote 2 Ships were still powered by wind, their hulls constructed from wood. Japanese sea-faring vessels were neither capable of intentionally crossing the Pacific Ocean nor legally permitted to do so; overseas migration was also prohibited. And halfway across that vast expanse of water which Edo intellectuals labelled not the Pacific but the ‘great eastern sea’, islanders on the Hawaiian archipelago were only just beginning – after the year 1778 in European calendars – to explore the possibilities raised by their encounters with people from beyond the realm of their ocean-faring memories.Footnote 3 In the first decades of the twenty-first century, by contrast, the world is unimaginable without the transformations epitomized by the Yamashiro-maru’s Hawaiian arrival: that is, long-distance transport infrastructures; labour migrations and transnational families; fossil fuel consumption on an unsustainable scale; and tropes of a Pacific ‘paradise’ exploited by resource extraction. The story of a Japanese steamship thus speaks to the world today as much as to its nineteenth-century context.

At least, such a sweeping overview of Asian and Pacific engagements was the book I originally thought I would write. Inspired by C. A. Bayly’s The Birth of the Modern World, 1780–1914, and Jürgen Osterhammel’s The Transformation of the World, I planned a ‘global history’ in terms of broad brushstrokes and apposite vignettes: in my case, of Japanese contributions to the period Bayly characterized as modernity’s ‘great acceleration’ in the decades either side of 1900.Footnote 4 Japan fascinated non-Japanese people in these years, whether in the speed of society’s perceived ‘Westernization’ after the 1868 Meiji revolution, or in the carefully curated image of national ‘civilization’ – wooden temple reconstructions, gorgeous silk kimonos – presented at world fairs in Europe and North America, or in the supposed anti-colonial vision its victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5) constituted in the imaginations of colonized peoples in North Africa and South Asia.Footnote 5 My focus on a single steamship, especially on its migrant passengers, was initially intended to complicate these stereotypes by examining the socioeconomic costs of societal transformation during the Meiji period (1868–1912), alternative expressions of Japaneseness on Hawaiian plantations or Singapore streets, and the complex imbrication of overseas migrants with Japanese settler colonialism. And in the pages which follow I indeed address these issues, alongside the wider dynamics of labour, race, and environmental disruptions at the turn of the twentieth century. But the way I do so derives from my realization that the book I wanted to write was not a global history in the mode of all-encompassing vistas of modernity and globalization.

One problem was where to begin – a problem which quickly shifted from aesthetics to the epistemologies of archival position.Footnote 6 In an earlier age, whose logic still pervaded my historical training in the heart of the British establishment, the geographies of intellectual choice seemed simpler. If you wanted to write about local history, you began with local archives; if you were researching an aspect of the modern nation-state, you would at some point end up in national archives. A recent book on ‘the birth of the archive’ reinforces this basic binary: the author first acknowledges institutions ranging ‘from small city archives with the charm of improvisation to great national archives with sophisticated operations’.Footnote 7 But the problem of where or how to conduct global history research was not addressed in an older literature on historians’ enamoured relationship with the archives;Footnote 8 and, as I shall argue, Ann Laura Stoler’s crucial insight that colonial archives produce colonial ontologies, or ‘categories of things that are thought to exist’, has been inadequately pursued in a global history literature.Footnote 9 Bafflingly, the canonical works on global history methodologies have overlooked archival considerations, as have interventions on the ‘prospect’ or ‘futures’ of the field. Pamela Kyle Crossley went so far as to claim, in her What Is Global History? (2008), that ‘the essential work of discovering facts and assembling primary history is not the work of those doing global history’, while Sebastian Conrad’s wide-ranging book of the same title (2016) eschewed global history archives as an explicit object of analysis.Footnote 10

But if we accept that the past is a position, as Michel-Rolph Trouillot argued in his groundbreaking study of power and silence in Haitian history-making, then the physical site of the archive must be a key epistemological consideration in where a ship-centred history should begin, and what form its global dimensions might take.Footnote 11 Through histories of passage and landfall, Mooring the Global Archive attempts to answer a set of questions concerning the sites of ‘global’ archives, how they are constituted, and by whom. The standard answer to these questions, if they are asked at all, invokes some variation of the phrase ‘multi-sited archival research’, as if number and geographical breadth alone conjured up the global. But I shall argue that the production of global history emerges not only in archival breadth or archival silences – important though these are – but in the brackish spaces between archival sites, or between physical and digitized archives; in ontologies co-produced as a consequence of complementary agendas shared by record keepers across great oceanic distances; and also in the historian’s imagination – or occasional failure thereof – as they try to bring different source collections into dialogue with each other. Broadly defined in ways I later discuss, ‘the archive’ disrupts ‘the global’ and the global reshapes the archive.

Through the heuristic device of the ship, I came to think of this mutual destabilization in terms of ‘archival traps’.Footnote 12 I lay out three such traps below, all of which I unerringly jumped into as I drafted book beginnings and shapely structures. The first was my hope that the Yamashiro-maru could be narrated as a quasi-biographical history, in which a ship’s ‘life’ could be told through moments of birth, death and achievements in-between. The second was my assumption that the global was googleable, such that the profusion of accessible, newly digitized sources might serve as my empirical base. And the third trap lay in the temptation to overlook the material contexts in which the languages of my sources were deeply embedded. Like all good traps, their cover was convincing: they led to several sources upon which I draw in future chapters, and they offered insights into how certain actors experienced change in the late nineteenth-century world. But they also led me to problematic narrative places in terms of my aspiration to write global history.

So here are three archival departures whose allure was all too real but whose intellectual logic I eventually came to jettison. Here is an explanation for why a gravestone inscription with the wrong date serves as this chapter’s epigraph. And here, along the way, are some background sketches of the late nineteenth-century worlds of Britain, Japan and Hawai‘i, between which the Yamashiro-maru steamed.

Trap 1: History as Moments of Birth

The most obvious place to begin was the ship’s launch in Newcastle upon Tyne: the moment of its official birth. Indeed, one of only three surviving photographs of the Yamashiro-maru (to my knowledge) document this christening ceremony, in January 1884. On a temporary wooden platform at the base of the vessel’s vast bow, around two dozen dignitaries pose for the moment of celluloid exposure (see Figure 1.2). The woman at the centre, Lady Margaret Armstrong (1807–93), wears a white fur cape; everyone else’s overcoat is of a more sombre hue. The six Japanese men in the group sport top hats.Footnote 13

Figure 1.2 The launch of the Yamashiro-maru, Newcastle upon Tyne, 12 January 1884.

Though a rare enough gathering to be worthy of a photograph, Japanese statesmen and businessmen had in fact been coming to the north-east of England for more than two decades by the time of the Yamashiro-maru’s launch. Back in 1862, the Tokugawa shogunate, weakened by the domestic unrest and foreign encroachment that would culminate in the 1868 Meiji revolution, had sent overseas embassies to Europe and Qing China, to build on the work of a similar mission to the United States in 1860.Footnote 14 To mark the ambassadors’ arrival in ‘our own neighbourhood’ as part of their European tour, the Newcastle Daily Journal offered a summary of the region’s historical achievements – in the modest prose typical of Victorian Britain:

Here in the cradle of the locomotive and the railway system; in the home of the High-Level Bridge; in the birthplace of the hydraulic engine and the Armstrong gun; and in the great centre of the coal trade, where works for the manufacture of lead, iron, and glass rise up on every hand – where, with one exception, the largest ships in the world have been built, and where alone in England the beauties of Continental Street architecture are worthily rivalled, the illustrious [Japanese] party whom we entertain today will find the real secret of England’s greatness among nations.Footnote 15

Meanwhile, on the same day as the Journal published these breathless claims, the shogunate’s embassy to China departed Nagasaki. Upon arrival in Shanghai, many in the group were appalled by what they perceived to be the decline of the Qing empire and the leeching of Asian resources at the hands of the ‘barbarian’ foreigners. But one attendant knew a good thing when he saw it. In his diary, he sketched an Armstrong twelve-pound cannon, a gun which had been extensively used by British forces against the Qing during the Second Opium War (1856–60). From prior discussions with Portuguese interlocutors in Nagasaki, he already knew that British battleships, armed with great cannons, rendered Britain ‘the mightiest country in the world’.Footnote 16 Together with the Newcastle Daily Journal’s claim to ‘greatness’, this perception of British ‘might’ drove the logic which subsequently brought top-hatted men to Newcastle in 1884.

The career of one such man, bearded and standing to Lady Armstrong’s right, offered a way to consider the Yamashiro-maru’s conception in the early 1880s as part of Japan’s pursuit of alleged Euro-American pre-eminence. Mori Arinori (1847–89) grew up in the southern domain of Satsuma, one of the shogunate’s historical foes. In 1863, as Japan descended into pro- and anti-Tokugawa civil strife, Mori’s home town of Kagoshima was bombarded by British ships as payback for the murder of a British merchant by Satsuma samurai. Armstrong-built guns ‘laid the town in ruins’.Footnote 17 Awed by the superiority of British military power, the Satsuma domain established a new School for Western Studies in 1864. Mori was one of its first pupils, specializing in English and naval surveying; the school also taught the natural sciences, military strategy, engineering, shipbuilding and medicine. The following year, he was one of fourteen Satsuma students clandestinely sent to study at University College London. During the summer vacation of 1866, Mori and a friend spent time in Russia, travelling first to Newcastle and then crossing on a coal barque to Kronstadt. The intra-European contrasts that he observed during this period led him to insist that in addition to Britain, the key country with which Japan should engage was not Russia but rather America. Mori himself was appointed deputy minister to the United States five years later, in the wake of samurai from Satsuma and other domains establishing the new Meiji state.Footnote 18 Following his return to Japan from Washington in 1873, he was one of a group of influential intellectuals who argued for faster Westernization at home. In his ‘First Essay on Enlightenment’, probably written in the same year, he imagined human development in terms of ‘change in man’s means of support’ – from what he called savage to half-enlightened, and from there to kaika 開化, a term traditionally translated as ‘enlightenment’. He wrote: ‘Once national customs have reached this level [of enlightenment] in some part, countries can construct machines, erect buildings, dig mines, build ships, open seaways, produce carriages, and improve highways. Thus will the thousand industries and ten thousand arts burst forth one after another.’Footnote 19

Gazing unsmiling into the camera on the morning of 12 January 1884, the scaffolding of the Low Walker dockyards latticed all around, Mori may have considered Newcastle upon Tyne an epitome of this transformative vision. He was present in one of his last official duties as Japanese Minister to London, a post he had held since 1879. A new public–private enterprise, the Kyōdō Un’yu Kaisha (KUK, or ‘Union Steamship Company’) had been founded just eighteen months previously in Tokyo to challenge the monopoly influence of the Mitsubishi company and to establish Japan as a major maritime power in East Asia.Footnote 20 Company executives, visiting British shipbuilding centres since 1883, had ordered sixteen custom-built steamships for the KUK, and the Yamashiro-maru, at 2,490 gross tons, was the first and biggest of the new fleet.Footnote 21 It therefore made sense for Mori to attend the ship’s launch, representing as it did one articulation of the ‘level of enlightenment’ which he had long hoped Japan would attain. And perhaps the Yamashiro-maru was in the back of his mind when he gave his final newspaper interview before departing London a few weeks later. ‘People imagine here that Japanese progress during the last ten or fifteen years is a new thing to us,’ he explained. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth: for centuries until the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan had taken ‘that which is best from all worthy nations with which we [came] into contact’. Japanese strength was epitomized by this ‘importation of ideas and institutions from foreign and alien civilizations’. And now, having overthrown the Tokugawa, and bolstered by the knowledge that the imperial dynasty had (allegedly) remained unbroken for 2,500 years, ‘it is natural that we should feel a pride in our country – a pride that makes us smile with amusement at the idea that our importation of steam engines, telegraphs, or Parliaments can in any way affect our Japanese heart’.Footnote 22

Such a profile of the most important Japanese dignitary attending the Yamashiro-maru’s launch served as one possible template for framing the history of the ship itself. It thus constitutes the first archival trap, namely my initial instinct to anthropomorphize the ship – to assume that the Yamashiro-maru was an object whose history could be narrated in the form of a biography, just as historians have written histories of modern Japan through the figure of Mori Arinori.Footnote 23 But the problem was that the genre of biography implied a moment of birth and thus, as deployed figuratively in histories of the modern world (or, indeed, the archive), a linear temporality departing from origin points.Footnote 24 Such narrative linearity in turn reinforces a universalizing, Enlightenment mode of imagining the modern world, in which ‘progress’ moved in one direction and as yet unenlightened people, whether they be in Europe’s backwaters or beyond the European metropole, were destined to follow a predetermined course in the pursuit of catch-up.

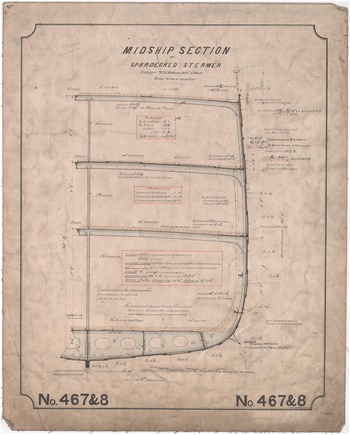

In practical terms, my imagination of the Yamashiro-maru’s January 1884 launch as such a moment of birth posed the danger of leading me towards a centrifugal narrative, whereby the ship equated to civilization bursting forth from a site of British ‘greatness’ and then proceeding – as the Yamashiro-maru did that July – towards a new home in Japan. In this mindset, my tendency was to shape even technical documents into a Mori-inspired mould of unidirectional history, in which the nascent ship both conformed to and reinforced standard narratives of modern world transformations. One afternoon in the autumn of 2009, for example, I visited the Tyne and Wear Archives, just down the hill from my office in Newcastle University’s Armstrong Building. There I called up a design drawing for the midship section of the Yamashiro-maru (constructed in the Armstrong–Mitchell company’s Low Walker yard 467) and its sister ship, the Omi-maru (yard 468).Footnote 25 On paper thick to the touch, a beguiling set of acronyms, numerals, annotations and calculations spoke to the physical heft of a vessel which – as we shall see – contemporaries hailed as ‘handsome’, ‘lofty’ and ‘splendid’ (see Figure 1.3). The ‘3″ [three-inch] teak deck’ conjured up the tapped sound of polished leather shoes strolling from stern to bow during an afternoon promenade, the flesh of first-class hands resting on iron railings. In the Yamashiro-maru’s entry in the Lloyd’s Register (1884–5), the line C.I.Cy.42″&78″ – 54″ similarly evoked a copper-sheathed, two-cylinder engine, both cylinders 54 inches in length but the narrower one – 42 inches wide – being where steam was compressed at high pressure.

Figure 1.3 ‘Midship Section of Spardecked Steamer’ (Yamashiro-maru and Omi-maru).

Or, more to the point, such numbers would have translated into a basic materiality, had I known their meaning. As it was, I had to go online to fathom the drawing’s 300′ PP (‘300 feet between perpendiculars’, the Yamashiro-maru’s length) or 37′-0″ BMLD (its breadth).Footnote 26 The engine had to be explained to me several years later by a retired shipbuilder in the German city of Rostock, with the help of a dictionary, a bottle of wine, and – on his part – infinite reserves of patience.

But even without grasping these technical details, I sensed what the numerals represented. Scaled up at half-an-inch to the foot, the result would be not merely a ship but a way of measuring the world: where those in the know, no matter whether they came from Kagoshima or Kronstadt (or Rostock), would recognize the technology as meeting international standards; where the publication of those standards – the post-launch Yamashiro-maru was awarded the highest possible ‘A1’ Lloyds rating for hull and equipment – constituted global ‘indicators of a ship’s modernity’.Footnote 27 Thus, the design drawing’s technical information served as a synecdoche for the increased standardization of nineteenth-century global time and space – itself symbolized by the October 1884 treaty to establish an international time regime.Footnote 28 Like the temporal marker of Greenwich Mean Time, the surviving traces of the Yamashiro-maru in the Newcastle archives would anchor my history to an hour zero: a base point from which to narrate, through the ship’s subsequent journeys, what Bayly called the world’s ‘great acceleration’ towards a modern age.

True, Mori Arinori himself apparently subscribed to the idea of base points when he spoke of Japanese ‘progress’ (shinpo 進歩) in comparison to a British civilizational standard, and of ‘importation’ as a means by which Japan might catch up with the West.Footnote 29 For many years, moreover, historians borrowed this rhetoric of the actors and ascribed it an analytical value. Thus, in an influential essay entitled, ‘The Spread of Western Science’, George Basalla argued that the steamboats introduced to the River Ganges in the 1830s were ‘far more than a rapid and effective means of transportation’. In words which Mori could have uttered, Basalla continued, ‘[Steamboats] were vectors of Western civilization carrying Western science, medicine, and technical skills into the interior of India’.Footnote 30 But this imagination of the world, which my own vectors of assemblage in the Newcastle archives seemed likely to reinforce, served only to privilege certain metropolitan narratives.Footnote 31 To consider the ship’s birth as one moment in the spread of civilization from Britain to Japan would be to entrench a modernist historiography of what Dipesh Chakrabarty has pithily called, ‘first in the West, and then elsewhere’.Footnote 32 It would be to reinforce a diffusionist view of progress that the nineteenth-century discipline of history, at least as practised in Europe, itself validated – thereby undermining my aspiration to write any kind of global history.Footnote 33

Obviously, this is somewhat of an exaggeration. There was nothing in the Tyne and Wear Archives that would determine a West-first reading of the Yamashiro-maru’s history, nobody insisting that I reconstruct Mori Arinori’s career or cite his words. But the absence of other voices and genres of written sources (a problem that was becoming clearer by the day); the materiality of the magnificent red-bricked Armstrong Building from which I wrote; Armstrong’s statue and the natural history museum and the other spaces bequeathed by this global engineering ‘magician’ in Newcastle and around the region;Footnote 34 the survival of the Armstrong–Mitchell company records; and even the drawing’s thick paper in my hands: these seemed likely to launch me on a linear history pursuing tropes of greatness, progress and Japanese catch-up.Footnote 35

There were other tropes hidden in this story, not least Mori’s reference to the ‘Japanese heart’. If I could find a way of fleshing out this claim, either through Mori himself or even better through the words of any of the thousands of Japanese migrants who had travelled on board the Yamashiro-maru, then this potentially offered an alternative vocabulary to ‘civilization’ for understanding Japan’s late nineteenth-century engagements with the world, and thus a less standardized way of framing the ship’s global history as a story of modernity. There were also alternative temporal scales suggested by the lived landscape of north-east England, in particular the histories of coal formation and extraction. These possible alternatives offered a way of imagining the ship, and, indeed, the modern world, not in terms of moments of birth but in terms of a process which encompassed parallel timelines.Footnote 36 Turning that imagination into a narrative that might work on the page was a different order of challenge, however. Back in 2009, my own design drawing of the Yamashiro-maru was merely a rough sketch, its calculations far from complete.

Trap 2: The Global as Googleable

Luckily, the internet was to hand – a different kind of archival trap. As I began imagining alternative points of departure, historians were debating new destinations, intellectual journeys made possible by the fact that ‘networked access to online sources and to one another has completely changed the transaction and information costs that historians face’.Footnote 37 During my doctoral studies, my research had involved oral interviews and paper archives – the latter most haphazardly preserved in rural Japan. The transaction and information costs were high (as were my carbon costs), involving a flight to Tokyo at the very least. If digitized sources had aided my work at all, they had done so in a supplementary way, an extra gust of wind to my analogue sails. But now, in the long winter evenings of northern England, even something as methodologically unsophisticated as the single-box search engine promised an entirely new source of research power. I could sit at my screen, type some imaginative combination of yamashiro and steamship and 1880s – and one night be presented with the search result, Full text of “Reminiscences of an Ancient Mariner”.Footnote 38 Tempted by this none-too-subtle allusion to Coleridge, I read on, turning yellowed pages with the tap of a touchpad, revelling in accessibility and drowning in detail.

Reminiscences had been published in Yokohama in 1918 by one of the city’s English-language newspaper presses. Its author, John J. Mahlmann, had by that time been living in Japan for nearly fifty years – the ‘New Japan’, as he at one point described it. ‘The Japanese people have undergone many changes,’ he wrote, ‘in some ways for the better, and in others not. They are endeavouring to raise themselves to the level of the most advanced nations, and I am of the opinion that if given enough time, their endeavour will be crowned with success.’Footnote 39 Here, more than four decades after Mori Arinori’s ‘First Essay on Enlightenment’, was the undying trope of civilizational catch-up, replete with the language of nationally distinct ‘levels’. And Reminiscences made clear that Mahlmann had played his own role in this Japanese ‘success’ story, most notably as harbour master at Kobe, 1888–98, and then as Meiji government adviser until his retirement in 1902. He had been decorated for his efforts with the Third Order of the Rising Sun.Footnote 40 But if Mahlmann had made the New Japan, then Reminiscences demonstrated that Japan had equally made the New Mahlmann. By 1918, he was a paragon of respectability, a man so far removed from the dubious associations of his youth that his memories merited publication – that in his dotage (this the greatest claim of all to respectability, arguably) he could afford to sojourn in Switzerland.Footnote 41

Such a respectable future would have been unimaginable in 1864, the year Reminiscences begins. Mahlmann fails to make his anticipated £50,000 fortune in Hokitika during New Zealand’s West Coast Gold Rush.Footnote 42 After working his way back to Australia (whence the reader is led to believe he comes), he finds various employments, including as chief mate on a commodity-trading ship sailing between Sydney and the Gilbert Islands.Footnote 43 In 1868 he joins a barque overloaded with coal, bound from Newcastle (New South Wales) to Shanghai. The vessel is wrecked in the Marshall Islands, but Mahlmann is eventually picked up by the notorious US trader Benjamin Pease (1834–70), for whom he will work on the Caroline Island of Pohnpei. And thus to one of Mahlmann’s aims in penning his autobiography: he wants to ‘clear away any misunderstanding among my acquaintances respecting the extent of my connection’ with Pease and with William ‘Bully’ Hayes [1829(?)–77], also American, who were heavily involved in ‘blackbirding’ – that is, the abduction of tens of thousands of Pacific Islanders to work on colonial plantations in Queensland in particular.Footnote 44 Eventually, in mid 1871, Mahlmann makes his way to Shanghai but there discovers that Pease’s company, for which he’d been promised employment, has collapsed. Instead finding work on a steamer belonging to the Yokohama-based Walsh, Hall & Co, he arrives in Japan on 1 November 1871.

Though no Coleridge, Mahlmann offers the reader an intriguing insight into the changing economic dynamics of the Pacific world in the mid nineteenth century. We grasp the migratory pull of gold rushes; the increasing presence of US interests in the region, even as China remained a key market for Pacific commodities; the British imperial infrastructures which supported the shipping of coal to the strategic port of Shanghai; the continuation of a Pacific slave trade deep into the nineteenth century; and the emergence of Japan into East Asian trading networks during the 1860s and 1870s.Footnote 45 But there is nothing in these stories to suggest that Mahlmann was Third Order of the Rising Sun material, either in 1871 or in the years that followed – which boast the chapter titles ‘Coasting and Loafing in Japan’, and ‘Here, There and Everywhere’. Late in 1884, however, Mahlmann’s fortunes took an upward turn. Due both to his years of service in the Japanese merchant marine, and to his acquaintance with Robert W. Irwin (1844–1925) of the new KUK shipping company, he was offered command of the KUK’s ‘best steamer at the highest rate then going’.Footnote 46 This was the Yamashiro-maru.

During Mahlmann’s three years in the ship’s command, the Yamashiro-maru mainly ran the Kobe–Yokohama line, the key passenger and freight artery of Meiji Japan. Mahlmann was thus on the bridge when the young Yanagita Kunio travelled to Tokyo in 1887.Footnote 47 But in addition to these regular duties, in May 1885 the Yamashiro-maru was also ‘chartered to take 1,000 Japanese emigrants to Honolulu, to be distributed from there among the different sugar plantations on the islands’.Footnote 48 The chapter Mahlmann writes on Hawai‘i constitutes the most detailed episode in Reminiscences. In it, he describes a seventeen-day quarantine period that all first-class passengers and crew were forced to spend on the ship after the belated discovery, upon arrival in Honolulu, of smallpox among the migrant labourers. But the main story, accompanied in the text by imprints of King Kalākaua (1836–91, r. 1874–91) and Queen Kapi‘olani (1834–99), concerns a working tour that the Yamashiro-maru took of the Hawaiian Islands, joined also by the royal couple. There is ‘Hawaiian dancing’ on the ship’s decks, a ‘charming’ dawn view of Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea (Mahlmann reaches for the cliché, ‘Paradise of the Pacific’), and a respectful nod to the new monument honouring where Captain Cook ‘was foully murdered by a native in 1779’. Upon the Yamashiro-maru’s return to Honolulu, there is more royal dancing late into the night. At an impromptu breakfast ceremony, Mahlmann is appointed Companion of the Royal Order of the Crown of Hawai‘i in the presence of the king, government ministers, the aforementioned Mr Irwin and the Royal Hawaiian Band.Footnote 49 The author plays to the crowd in these pages, reinforcing an anti-Native Hawaiian stereotype of King Kalākaua which would later coalesce around the phrase, ‘merrie monarch’.Footnote 50 But mainly the chapter is about Mahlmann himself: his newfound status as an acquaintance of monarchs and ministers; his royal honour in Hawai‘i foreshadowing his imperial honour in Japan; his becoming, through the Yamashiro-maru (‘the first Japanese merchant steamer that ever visited the islands’), a conduit of the New Japan.Footnote 51 Indeed, his command directly leads, at the turn of 1888 and in his fiftieth year, to his prestigious appointment as Kobe harbour master. Thus, Mahlmann’s service as the Yamashiro-maru’s captain serves as a narrative bridge between his chequered life aft and his reputable life fore.Footnote 52

As I say, a lot of detail. But reading Reminiscences in 2009, I became convinced that the ship as a narrative device, shaping however briefly the lives of historical actors and their subsequent memories, could be a model for my book as a whole. If I could interpret Mahlmann’s biography in this way, then approximately 1,000 other opportunities for a similar approach presented themselves to me in the form of the Japanese migrants transported to Hawai‘i in 1885, such that the ship would summon subaltern lives.Footnote 53 All I needed was to google a little more – although perhaps with a tad more search-term sophistication.

And so to the second archival trap. My online reading of Mahlmann’s Reminiscences was one manifestation of what Lara Putnam has called the ‘digitized turn’.Footnote 54 Indeed, my research for Mooring the Global Archive in the 2010s coincided with an intensification of source digitization in the Global North especially.Footnote 55 English-language newspapers in Hawai‘i that could only be manually searched on microfilm readers in 2011 were by 2014 miraculously available on the Library of Congress’s ‘Chronicling America’ online directory. In the period 2012 to 2014, as I trawled through bound paper files in the Diplomatic Archives of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, documents were being unbound and photographed at an adjacent table. The archivists’ whispered consultations and the camera’s electronic click formed a background soundtrack to my research. Over the months, staff updated their work in a colour-coded spreadsheet on the archive’s website.

If the updates evoked a journey’s progress similar to that measured by a shipboard log (a source genre which was proving frustratingly difficult to find in the Yamashiro-maru’s case), then comprehensive digitization was our promised destination – depending on what was meant by ‘comprehensive’. Mahlmann had appeared in my Google search results because someone called Alyson-Wieczorek, working for the non-profit Internet Archive, had uploaded Reminiscences to archive.org on 10 May 2007.Footnote 56 As of June 2022, Alyson-Wieczorek has an upload history of 68,455 texts, 97 per cent of which were published in English. For the Internet Archive as a whole, 74 per cent of the 34.9 million digitized texts are published in English, with the three next most popular languages – French, German and Dutch – comprising another 6 per cent.Footnote 57 There was a similar imbalance in Chronicling America: after 2014, you could browse those Hawai‘i-based newspapers founded before the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in January 1893 – Chronicling America had nine – and come away with the erroneous impression that English was the only language of the islands.Footnote 58 Hawaiian-language newspapers do in fact exist in large numbers, and have been digitized by local institutions rather than by the Library of Congress; but as of mid 2022, neither Hawaiian nor any other Indigenous North American or Pacific Island language appears as a search filter option on Chronicling America.Footnote 59 In other words, I could read Mahlmann online because the vast majority of printed publications digitized by the Internet Archive and other similar services are English-language sources.

The trap’s narrative consequence was that Mahlmann would all too easily become the textual embodiment of the Yamashiro-maru in Hawai‘i, the ship’s story his story. By contrast, it turned out that to study the Yamashiro-maru’s nearly 1,000 emigrants to Hawai‘i in June 1885 still necessitated the transactional costs of multiple flights to Japan and their concomitant carbon footprint, because the very files I had been reading to reconstruct their migrations in the Japanese Diplomatic Archives came from exactly those source series which were not and will not be digitized (see Chapter 5). This discrepancy highlights what Putnam has identified as ‘the systematic underrepresentation of whole strata of people in our now-massive digitized source base’.Footnote 60

The chapters which follow offer a set of archival strategies for narratively countering this digitized source underrepresentation. But my narrative also occasionally pauses to reflect on why historians should practise greater methodological transparency in a digitized age. For example, my blithe assumption that the global was googleable overlooked the problem of traceable archival pathways. In an analogue world, archival collections are ordered according to certain organizational principles. To map these principles, and to understand how they affect results generated by a particular archival request, is partly to identify what Ann Laura Stoler calls the ‘archival grain’ – and thus to trace, as if fingering a piece of timber, one’s lines of archival enquiry.Footnote 61 If newly digitized archives and their browsing infrastructure maintain the original organizational principles of their physical counterparts – as was eventually the case with the Japanese diplomatic archives – then all to the better. But with invisible commercial algorithms driving general internet searches, some of the archival grain has become impossible to trace.Footnote 62 A decade on from 2009, and thanks to the Wayback Machine (itself developed by the aforementioned Internet Archive), I could reconstruct a decent approximation of the websites I had visited at the beginning of my research.Footnote 63 But I could never revisit the paths that had led from my browser one winter evening in Newcastle upon Tyne to Mahlmann’s Reminiscences, nor explain how a similar search ten years later might throw up subtly different results. One principle of scientific reconstruction, manifested in the discipline of history in explanatory footnotes or endnotes, has thus been broken. The fact that the text-searchable is at some level irretrievable thus provides one justification for my argument concerning authorial transparency. If the internet offers serendipitous discoveries whose algorithmic pathways nevertheless remain commercially hidden, then one compensatory move is for scholars to offer greater methodological self-reflection in other aspects of their research – as Mooring the Global Archive attempts to model.

By itself, this call for transparency is not entirely new. A recent literature on digital methodologies in history has argued for scholars to provide more reference information: on whether a newspaper article was accessed via a database, a microfilm or the original paper copy; on search strings – namely, the combinations of yamashiro and steamship and 1880s that I no longer recall – and on the specialized databases through which we can run those searches.Footnote 64 The problem is, the assumption lying behind these arguments is that the digitized turn in history, including the new possibility to analyse millions rather than thousands of source pages, has rendered archival work exponentially more complex than it was in a predigital world. ‘Historians’ relationship to the archives used to be simple’, we have been told; but with the digital age, ‘Historians now not only use but create, contribute to, and theorize collections of digital records, some at massive scale.’Footnote 65 Or equally, ‘the stereotypical historian still remains resolutely tied to scholarly traditions – dust in the archives rather than bytes in the computer’s memory’.Footnote 66 The straw man pervades such statements: if scholars in the old days can be represented as simply turning up to ‘use’ paper archives (trying not to sneeze too much from dust in the process), then new methodologies in digital history research appear even more innovative.

In digital as in global history, the appeal of the term ‘unmooring’ partly derives from this rhetoric of stasis, in which outdated methodologies are tied to analogue research traditions or national history pasts.Footnote 67 My contrasting emphasis on ‘mooring’ comes not from a place of nostalgia for those paper-filled days in national archives, but from a contention that the digitized turn has not rendered position and place irrelevant in the writing of history, especially global history. For sure, Mooring the Global Archive as a research project would have been dead in the water without the digitization of sources such as Mahlmann’s Reminiscences or the Daily Pacific Commercial Advertiser. But the trap lay not just in the appeal of their accessibility or in their volume (and English-language bias), and the narrative consequences thereof. It also lay in the incalculable ‘information cost’ of what knowledge I would have overlooked without my pre-online memories of having first read microfilm copies of the Advertiser in the Periodicals Room of the Hawai‘i State Library. Here, then, we arrive at a third archival trap, namely my assumption that historical context was primarily a matter of written text rather than material encounter.

Trap 3: Fixation on the Written Word

The Yamashiro-maru does not survive. The board minutes of the Nippon Yūsen Kaisha (NYK), the enterprise formed in October 1885 from a merger of the KUK and Mitsubishi companies, record that the decision was taken in March 1908 to divest of ‘obsolete and uneconomic’ vessels, and both the Yamashiro-maru and the Omi-maru were sold for scrap eighteen months later.Footnote 68 A second-generation Yamashiro-maru would be constructed for the NYK in Kobe in 1912, the year of the Meiji emperor’s death – but that story, with which Mori Arinori would surely have defended the notion that civilized nations build ships, must be for others to write.

Though the first Yamashiro-maru’s scrapping deprives me of a museum experience such as that offered by the Bristol-built SS Great Britain (launched in 1843), and thus of the chance to walk, touch and inhale the ship, there are other archival ways to grasp its materiality. This is because after historical vessels had been constructed through cutting, moulding, welding and hammering, they were then produced a second time: through adjectives, numerals, metaphors and iconography. Briefly examining some of these rhetorical constructions in Honolulu, first via New York, Millwall and Edo Bay, reveals a vocabulary of global encounter in the second half of the nineteenth century – while also highlighting the trap of our becoming too fixated on the written word alone.

When the SS Great Britain arrived for the first time in New York, for example, newspapers described it as a ‘monster of the deep – this Megatherion [sic], or Megaplion, rather of the nineteenth century … this mammoth’.Footnote 69 Megaplion simply meant ‘great ship’; but megatherium (great beast) was the name that Georges Cuvier (1769–1832) had famously given to the huge fossil skeleton discovered in the 1790s in Spanish America, with which he proposed a theory of extinction and thereby a much longer history of the earth than Biblical time allowed. This kind of labelling, applied as it often was to mid nineteenth-century steamships, implied that the new technology was so revolutionary in shrinking global distance that, like the new disciplines of geology and palaeontology, it would ‘burst the limits of time’ (to use one of Cuvier’s most memorable phrases).Footnote 70 Thus, the Millwall-built SS Great Eastern (launched in 1858) was similarly described by contemporaries as ‘pre-Adamitic’, a vessel ‘to which even Noah’s Ark must yield precedence’.Footnote 71 Half a century later, a newspaper correspondent looked back to the Great Eastern as a ‘leviathan born out of due time, since even now she dominates the imagination of many’.Footnote 72

Japanese commentators in the mid nineteenth century also constructed steamships rhetorically, but without the Biblical references. Like their European and North American counterparts, they offered their readers detailed technical descriptions. When, for example, Commodore Matthew Perry (1794–1858) arrived with a small squadron in Edo Bay in July 1853 to force the Tokugawa shogunate into agreeing trade treaties with the United States (see Chapter 6), one local artist framed his monstrous depiction of one of Perry’s two steamships with a cartouche recording the alleged dimensions of the vessel: length 75 ken 間, breadth 20 ken, wheel 6.5 ken; three masts; distance from waterline to deck 2 jō 丈 5 shaku 尺; and so on (see Figure 1.4).Footnote 73 Encountering the squadron up close, local fishermen talked of ships ‘as large as mountains’ – a trope which was quickly taken up by writers as far away as Wakayama. (That there was already a word for ‘steamship’ in Japanese suggests that there may have been an element of hyperbole in these visual and verbal depictions.)Footnote 74 In June 1860, a diarist on the Tokugawa shogunate’s aforementioned embassy to the United States used a similar analogy in New York, when the ambassadors’ departure coincided with the arrival of the Great Eastern on its maiden transatlantic voyage: the British ship, he wrote, ‘was like a mountain protruding from the sea’. Another of the mission’s diarists inadvertently echoed the press coverage of the Great Britain’s arrival in New York fifteen years previously when he described the Great Eastern as a ‘mammoth [kyodai naru 巨大なる] British merchant steamship’.Footnote 75

Figure 1.4 ‘Depiction of a Foreign Ship’ (Ikokusen-zu 異国船図).

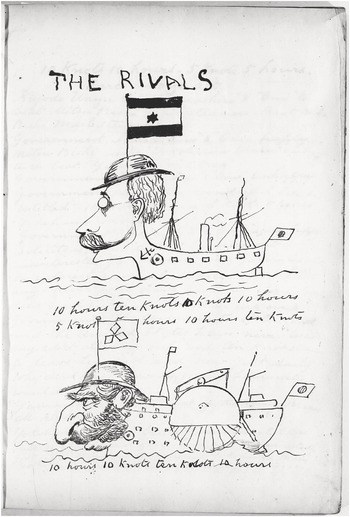

To be clear, the Yamashiro-maru in the mid 1880s did not provoke such hyperbole. Its name notwithstanding – Yamashiro (山城) literally means ‘mountain castle’, referring to Japan’s most important ancient province (see Chapter 4) – the vessel was no Great Eastern-like ship-mountain. But it did provoke considerable comment in Japan’s English- and Japanese-language newspapers upon its post-launch arrival from Newcastle in July 1884, as if its much-noted interior electric lights embodied a level of enlightenment.Footnote 76 In another example of steamship anthropomorphism, a cartoonist working for the Yokohama-based Japan Punch newspaper even gave the Yamashiro-maru facial features (see Figure 1.5): the ship took on an appearance very close to that of the KUK’s Robert W. Irwin, as the foreign press decried the deleterious competition between the KUK and Mitsubishi prior to the two companies’ merger.Footnote 77 And in by far the most detailed written description I found during my years of research, the Yamashiro-maru was produced to have a different face, namely that of Japan.Footnote 78

Figure 1.5 ‘The Rivals’, Japan Punch, January 1885. (The Yamashiro-maru is the upper ship.)

To understand how this rhetorical production of the ship as the face of Japan worked in Hawai‘i, we need to return to the Yamashiro-maru’s arrival in Honolulu – the episode with which I began this chapter. During his perfunctory first inspection on the morning of 17 June, the government-appointed doctor had in fact missed all the classic symptoms of smallpox among a small number of passengers who were sick. Only thanks to a second inspection, after the ship had docked, was the disease discovered and the potential public health disaster of infectious passengers entering the archipelago avoided. Nevertheless, as Mahlmann had noted in his Reminiscences, ‘The newspapers censured the port physician most severely for not knowing the difference between measles and small-pox, and had much to say about the probable dreadful consequences thereof’.Footnote 79 This comment gave me a new research lead. But if I wanted to know what these Hawaiian newspapers had actually written in the pre-digitized era of 2011, I needed to fly to Honolulu – and find the institutional sponsorship to do so.Footnote 80

Once there, I started by retrieving some basic contextual facts on the smallpox incident from the government records of the time: the minutes of the Hawaiian Board of Health, for example, or those of the Board of Immigration. These survive in the Hawai‘i State Archives, a rectangular, white-panelled building which squats among banyan trees in the south-east corner of the ‘Iolani Palace grounds. (The palace had been completed in 1882 as a way of impressing Kalākaua’s kingship upon both his own people and the kingdom’s increasingly powerful – and critical – sugar planter constituency.)Footnote 81 After a day or two burrowing around there, I walked all of five minutes to the Hawai‘i State Library, loaded a plastic reel into one of the Periodicals Room’s microfilm readers and commenced a manual search for all newspaper references to the Yamashiro-maru or to smallpox in the summer of 1885. In the Hawaiian Gazette from 24 June, for example, I found a blistering attack on the Hawaiian government’s handling of the ship’s original inspection. This bemoaned the fact that though the man – an unnamed reference to Foreign Minister Walter Murray Gibson (1822–88) – ‘ruling these Boards had it in his power to prevent the slightest chance of contagion of small pox coming to these Islands through an immigrant ship from Japan’, he had failed to do so. The disease, it claimed, was ‘endemic in Japan, as it is in most Asiatic countries’, and agents in Yokohama had regrettably allowed on board the Yamashiro-maru a group of seventy-five people from the city itself, all ‘reeking from the slums of a seaport town’.Footnote 82

Back in the Hawai‘i State Archives, I found a letter to Gibson from Robert Irwin, KUK businessman and also Hawaiian consul to Japan. Written from ‘On board Steamship “Yamashiro Maru”’ while still in offshore quarantine on 25 June, Irwin challenged the accuracy of the Gazette’s claims about ‘endemic’ smallpox in Japan and immigrants reeking of seaport slums. ‘Our Japanese Emigrants,’ he insisted, ‘have come with the intention of remaining in Hawaii. They are hard working, industrious men.’ Japan, moreover, should not be considered ‘an Asiatic Nation’, for ‘Japanese people have nothing in common with India and China’, and ‘Japan is progressive and is rapidly becoming a Western Civilized State’. (And a postscript: ‘The “Yamashiro Maru” is a splendid iron steamer with capacity for 1,200 Emigrants in the steerage. We had 988, including children.’)Footnote 83

To the Hawai‘i State Library again. In the Daily Pacific Commercial Advertiser (proprietor: Walter M. Gibson), an article on 29 June asked, ‘Is Japan an Asiatic Country?’ No, the correspondent suggested. Paraphrasing but not acknowledging Irwin’s 25 June letter, he emphasized, ‘Japan has cut loose, as far as it is presently safe to do so, from its Asiatic methods, and adopted those of the Western world’. To which, a few weeks later, the Gazette responded with incredulity: ‘If the Japanese are not Asiatics what are they? Let us have Professors from Harvard, Columbia, Oxford and Cambridge, to settle the point.’Footnote 84

This to-and-fro, rhetorical as well as physical, offered two different ways to read the Yamashiro-maru. For critics of Japanese immigration to Hawai‘i and sceptics of Meiji Japan’s bona fide Westernization alike, it was no more than an ‘immigrant ship’.Footnote 85 For defenders of the New Japan, on the other hand, it was a ‘splendid iron steamer’ which carried ‘industrious’ labourers.Footnote 86 In the words of the Advertiser’s correspondent, touring the ship after quarantine, it was ‘a splendid specimen of marine architecture’. Indeed, his report, headlined, ‘THE YAMASHIRO MARU – Description of this Fine Japanese Steamship – Constructed and Equipped as a Cruiser with Krupp Guns – Her Rate of Speed, and Other Interesting Details’, appeared on 21 July, in the midst of the newspaper debate about whether or not Japan was ‘Asiatic’. Thus, when the correspondent waxed lyrical about the ship’s proportions, tonnage, engine size and consequent speed, about the reinforced main deck to support midship guns (should the Yamashiro-maru need to be converted for war service), about the electric lights of the Edison-Swan patent or the positioning of the compasses and steering mechanisms, the numbers were not neutral.Footnote 87 Rather, they gave empirical flesh to Irwin’s argument that Japan was ‘progressive’ and (here the Advertiser) ‘adopting [the methods] of the Western world’. Many miles from Newcastle, I was back at catch-up. The numbers produced the ship; the ship produced the face of Japan.

In Honolulu the archival trap was of a different nature, however. For a start, wherever I looked, the written sources constructed not only the ship but also the migrants on board. They were ‘hard working’; they were ‘Asiatic’; they were disease-ridden; and, after finishing quarantine on Sand Island, they were in the city and causing ‘amusing scenes’.Footnote 88 But the 988 men, women and children remained unnamed: not for the Advertiser the ‘interesting detail’ that the one Japanese man to die of smallpox was Tanaka Kōji, aged thirty.Footnote 89 Moreover, these sources gave no insight into the multiple causes of the migrants coming to Hawai‘i, including to work on the kingdom’s burgeoning sugar plantations. In other words, the nature of my archival fact retrieval rendered the Yamashiro-maru migrants silent – a silence that would be exacerbated by the post-digitized accessibility of the (English-language) Advertiser or the Gazette. The challenge would be to find a methodology to make them visible or audible – as I attempt, respectively, in Chapters 2 and 3.

But the main archival trap in Honolulu concerned the relationship between written words and their sites of preservation. Shuttling back and forth between the State Archives and the State Library, I was walking contemporary Hawai‘i’s statehood. The names of these institutions acknowledged the endpoint (in 1959) of a political history which came to the boil exactly in the years when the Yamashiro-maru transported migrants to Hawai‘i: with the imposition by sugar planter interests of the so-called Bayonet Constitution on King Kalākaua in 1887, followed by their overthrow of his successor and sister, Queen Lili‘uokalani (1838–1917), in January 1893. On the second floor of the ‘Iolani Palace, where the deposed queen had been forcibly confined for eight months in 1895, was the Imprisonment Room. There visitors can today view a quilt sewed by Lili‘uokalani while in captivity. The intricate patchwork was a very different kind of documentary evidence from the paperwork I was intent on retrieving. This was literal ‘context’, a weaving together (con-texere) of a past which coincided with the Yamashiro-maru but which it was all too easy to overlook if I stayed focused on rates of speed or other ‘interesting details’. Indeed, the quilt’s creation and survival constituted an act of archival resistance, into which Lili‘uokalani threaded memories of her life, Hawaiian nationhood and her own short reign.Footnote 90 Thus, the royal-cum-state land across which I walked also constituted archival context – but of a material kind, crucial both to an understanding of the ship’s nineteenth century world and to the kinds of ‘tacit narratives’ through which archives are constructed.Footnote 91

In the era of digitized and born-digital sources, historians have become adept at reading metadata – that is, data about data (such as who digitized Mahlmann’s Reminiscences, and when). But the ‘Iolani Palace lands across which I walked must also be considered essential data about data: the grounds and sounds and colonial legacies right outside the Hawai‘i State Archive’s doors were at some level framing my reading of the sources. It was a trap not to acknowledge this metadata, even if computer scientists have not (yet) found a way to annotate it. In falling into that trap, I risked overlooking both the historical protagonists whose migrant lives had tempted me to study the Yamashiro-maru in the first place – and the materially inescapable history of Native Hawaiian dispossession.

* * *

These were three archival traps: that I would anthropomorphize the ship at the time and place of its launch, turning its ‘life’ into a history of Japanese catch-up; that I would revel too much in the accessibility of digitized sources at the narrative expense of undigitized migrant actors; and that, in pursuing newspaper debates online, I would overlook crucial material metadata and its ongoing epistemological significance. My way out of these traps was to take time away from the archives, or from ‘the archive’ as I had imagined it to date – one comprising papers, microfilms and digitized sources. The credit for this goes to my wife Asuka, who convinced me that, enticing though the Hawai‘i State Library collections were (open ‘til late on Thursdays!), we should devote a few days to holiday not history – and we should do so at Hanalei, on the north-east coast of Kaua‘i Island.

Kodama’s Gravestone: A Mooring Berth

Of course, things are never that simple if you’re married to a historian. To Asuka’s demonstrable delight I proposed that on the way up to Hanalei we have the briefest of brief detours to Kapa‘a. This is because I had worked out that one man whose name I had previously encountered in a Japanese village archive, during my PhD research, had also emigrated to Hawai‘i on the Yamashiro-maru in 1889. A note from a village bureaucrat suggested that Fuyuki Sakazō had ended up in Kapa‘a; thus, I sunnily assumed, it might be possible to find something of him in the town.

During my PhD, my earliest interest in Japanese overseas migrants had been triggered by the material traces many of them left in their rural home towns – in the form of commemorative stones recording their donations to the repair of temples and shrines, or to the construction of new schools. In the absence of the schools themselves, rebuilt again in the post-war years, the stones constituted a largely unread archive of lives lived abroad.Footnote 92 As such, they were also a counter-archive to the wide range of elite explanations as to the value of overseas migration. For example, in a December 1885 letter to the Meiji government’s honorary consul in Tasmania, Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru (1836–1915) wrote of his dismay at ‘low and ignorant men’ leaving Japan without official permission. (Like Mori Arinori, Inoue himself had left Japan clandestinely to study at University College London in the 1860s.) And yet, he continued, the government was loath to prohibit labourer mobility as this ‘would not be consistent with the policy of promoting their progress by enlarging their knowledge of enterprise in the world’.Footnote 93 Here, the enlargement of knowledge was offered as a reason for which men sought work overseas. (No mention of women, as I explore in Chapter 5.) The fact that local institutions needed to be repaired or built from scratch, however, and that labourers were remitting money home, suggested that socioeconomic factors more than a thirst for ‘knowledge of enterprise’ lay behind the decision to emigrate. But where my earlier work had focused on the home town, for my new project I wanted to study the labourers’ lives across the Pacific world, and to connect those transpacific histories through a ship.

In Kapa‘a we parked on the main street and, on nothing more than a whim, I entered the adjacent graveyard of the First Hawaiian Church. Already, I was doubting whether I would find any remains of Fuyuki, corporeal or otherwise; it would later transpire that the village bureaucrat in Japan had made a mistake, for Fuyuki never lived or worked anywhere near Kapa‘a. But after meandering for a few minutes, I stumbled across this untended headstone – and instantly knew that I’d had a stroke of incredible fortune:

KEIJIRO, KODAMA

ARRIVED

HAWAII, NEI

JUNE 18, 1885

DIED

KAPAA, KAUAI

MEIJI XXIX

JULY 9, 1896

By recording a date of arrival, the gravestone identified its subject as one of the nearly 1,000 migrants who had shipped to Honolulu on the Yamashiro-maru. No less importantly, it evoked a life lived between two worlds and the ambiguities arising therefrom. Thus, the comma on the first line indicated that the engraver – or, more likely, an unknown benefactor – was unsure whether the family name (Kodama) should take precedence or not. The comma on the third line suggested a similar cultural uncertainty with the Hawaiian phrase ‘Hawaii Nei’, or ‘beloved Hawai‘i’.Footnote 94 On the other hand, the inscriber knew enough to correctly translate the Gregorian calendar into that of imperial Japan (where ‘Meiji XXIX’ indicated the progression of Emperor Meiji’s reign, with 1868 as Year I); and the positioning of imperial before Gregorian dates perhaps gave precedence to the temporal regime by which Kodama lived until his death.

Admittedly, I articulated few of these ambiguities on that morning in Kapa‘a. And I missed entirely the inscription’s error: according to all surviving archival accounts, the Yamashiro-maru arrived in Honolulu on 17 June. But working through both the gravestone’s wrong date and its broader historical significance offered an escape from my previous archival traps. The simplest explanation for the mistake went as follows. Although the aforementioned International Date Line was agreed in an October 1884 treaty, its global synchronization was not simultaneous: Japan only harmonized in July 1886.Footnote 95 Thus, for anyone arriving in Honolulu from Yokohama in 1885, there may have been some confusion as to whether that morning was 17 or 18 June – a confusion exacerbated, more than a decade after the event, by the need to pinpoint a date for a gravestone inscription.Footnote 96 That said, there was no conventional need to record Kodama’s date of arrival: no such information was listed on other immigrant graves I subsequently studied in Hawai‘i (including several more on that ‘holiday’ weekend). This anomaly consequently raised a number of questions about Kodama himself.Footnote 97 Was the date so important in his memories that he repeatedly referenced it to friends? Did it signify for him the start of a new life, a new set of relationships to the Hawai‘i Nei? Did the gravestone’s benefactor understand those feelings and acknowledge them by noting Kodama’s date of arrival rather than his date of birth? Such questions were unanswerable. But at least to pose them reframed the problem away from my language of ‘errors’, ‘mistakes’ and ‘wrong dates’ – a vocabulary that reinscribed the idea of a standard base point against which all else must be measured, and that thus returned me to Trap 1. Instead, my questions suggested the necessity of positioning the labourers’ experiences and imaginations at the heart of my story: their material histories, their language, their conceptions of time and space.

Though imperfectly, this narrative repositioning is one challenge I take up in Mooring the Global Archive: to trace the worlds of the Japanese migrants and the worlds seen by those migrants, and to connect these traces to broader historiographies of Meiji Japan’s industrialization or the state’s colonial ambitions. In so doing, I contribute to a new literature which argues that Japanese overseas migrants were central to the making of the imperial state – as central, indeed, as the better-known Chinese diaspora is considered to Qing and post-imperial state histories.Footnote 98 But I go beyond this literature’s primary focus on the Japanese metropole to examine how migrants became entangled in the colonial contexts of the polities in which they worked, and the historiographical implications thereof.Footnote 99 By focusing on passages and infrastructures, I also broaden that literature’s assumptions about where migration histories might begin and end, and in what archival forms they might be found.

Indeed, my departure from the Kodama gravestone further entails a different way of writing about the historian’s relationship to archives. Though paper-based archives and their digitized iterations remain central to this book, I try to avoid privileging their epistemologies over other kinds of archival assemblages for which search engines do not exist. Equally importantly, I bring to the fore oft-overlooked contexts in historical research, namely the ‘metadata’ of (in this case) a spousal escape to Kaua‘i and improbable chance in a cemetery.Footnote 100 Such contexts raise important questions of privilege and transactional cost – visa regimes, institutional support, the carbon footprint, and not least time – which in most historical writing remains unacknowledged, or at best relegated to the Acknowledgements. I shall contend that what I call ‘authorial metadata’ is central to a historian’s reading of the archives – not as a cursory first-person preface to the heavy intellectual lifting, but as constituent to that intellectual work itself.

In these ways, I take the Kodama gravestone as a berth, both for the histories I reconstruct in Mooring the Global Archive and for the methodologies by which I do so. Kodama does not appear in every chapter of the book, nor did my memories of Kapa‘a prevent me from jumping headfirst into other archival traps since 2011, as I shall show. But at some abstract level the gravestone informs all that now follows.

* * *

Chapter 2 departs from the temporal spaces implied in Kodama’s 17–18 June discrepancy to consider what happened in the in-between spaces of the onboard. Here and in Chapter 3, I draw on John-Paul A. Ghobrial’s observation that the study of global processes of movement ‘obliges us to focus as much on the worlds that people left behind as the new worlds in which they found themselves’.Footnote 101 The chapters offer microhistorical reconstructions of two Yamashiro-maru migrants and their home towns in the mid 1880s. In Chapter 2, this leads to a broader discussion of the archival juxtapositions necessary both to counter the documentary void of the transpacific journey, and to challenge dominant narratives of a homogenized ‘Japanese’ identity with which the labourers were labelled upon arrival in Hawai‘i. Deconstructing these narratives in turn raises the problem of how the English- and Japanese-language historiography to date has excluded Native Hawaiian understandings of the new government-sponsored programme’s significance in 1885. Building on this presence of Native Hawaiian voices (or, rather, their absence in the archives of Japanese transpacific migration), Chapter 3 addresses how the archival reading room’s ‘sounds in silence’ can shape a historian’s analysis of archival documents and the gaps therein.Footnote 102 The central problem addressed is one of linguistic commensurability: how Japanese canefield songs correlate with an oft-used vocabulary of ‘circulation’ in global history; and whether a language of ‘industriousness’ (kinben 勤勉) in English and Japanese brings historians closer to understanding migrant labourers’ engagement in settler colonialism in Hawai‘i.

Chapter 4 attempts to answer Paul Carter’s questions, in his book Dark Writing: ‘Can we live with our maps differently? Could we inhabit our histories differently?’ Noting that ‘these are questions that might be addressed to modernity generally’, Carter contextualizes them by introducing the famous Petitions of the Aboriginal People of Yirrkala, two bark paintings dating from 1963 and collaboratively designed by Yolŋu artists in what colonial maps call the ‘Northern Territory’.Footnote 103 I also examine Yolŋu bark paintings, in order to posit a different cartographic and archival approach from that embedded in the map at the chapter’s heart – that is, an NYK company map which depicts its steamship routes across the Pacific world (including the Yokohama–Melbourne line, opened by the Yamashiro-maru in 1896). To the question of whether we could inhabit our histories differently, I reply in the affirmative, but with the caveat that any answer depends on who ‘we’ are, and what ‘our’ histories (and archives) are imagined to be.

Similar considerations of the first-person voice lie at the heart of Chapter 5. Interrogating the first-person testimony of a young Japanese woman, Hashimoto Usa, who left Nagasaki in June 1897 and ended up via Hong Kong in Thursday Island, I explore the gendered construction of the archival trail between Tokyo and Brisbane, and the concomitant difficulty in accessing the voices of female migrants. But part of the problem is my unfortunate use of verbs such as ‘interrogate’: thus, while I acknowledge Lisa Yun’s point that testimonial statements generated by state-led agendas are ‘not impervious to appropriation from below’ and may be ‘seized upon by subaltern agendas’, I also reflect upon the (male) historian’s archival interventions in the reading of female voices.Footnote 104 Finally, in Chapter 6, I step back – and below – to consider the fuel infrastructures of transpacific Japanese migration. This chapter focuses on a different kind of journey: that of a piece of coal from seam to ship. In so doing, it radically expands the scale of the temporal regimes that frame Kodama’s gravestone. But while I thereby make a small nod towards ‘big’ or ‘deep’ history, my interest remains anthropocentric. Like Timothy J. LeCain, I see the danger that very large scales of history can conversely lead to historical materiality being overlooked in favour of aggregate phenomena. Like mine, his interests lie in ‘the smaller scale lived phenomena of individual embodied human beings trying to warm their frosty fingers by tossing a few extra lumps of coal on the fire’. My chapter merely attempts to specify which coal, which fire and which human beings.Footnote 105

This has been a messy book in the making. Unlike a long and distinguished literature which has addressed ‘the world’ through the history of single ships, Mooring the Global Archive boasts no single textual genre through which to chart its course: no onboard journal, collection of poems, log book, popular travel account or legal case in the aftermath of a crime or mutiny.Footnote 106 My stories are disorderly and often out of chronological order – as demonstrated by my new interpretation of Commodore Perry’s engagement with Tokugawa Japan in 1853–4, addressed in the book’s final chapter.Footnote 107 To moor the reader, each of my chapters begins with a primary source and concludes with a methodological reflection, such that each may also be considered a stand-alone essay.Footnote 108 Mooring the Global Archive also includes images of people and places pertinent to the discussions – with the exception of Chapter 5, where, given the ways that migrating Japanese women were framed as ‘unsightly’, I have tried to avoid adding to these visual stereotypes through stock contemporary depictions of ‘Japanese ladies’ or the like. Given my arguments about the complex epistemologies inherent in cartography, I have equally refrained from including any custom-made maps and hope, for the most part, that the reader can follow my narrative routes through the historical maps in question.