During a visit to the Cibali Cigarette Box Factory in Istanbul in 1949, a labor journalist was struck by the productivity of the young girls, who assembled more than half a million boxes a day with dizzying speed. Guided by the signboards at the work stations, he approached the most productive workers from the previous day, Ruhsan and Nazmiye, two teenage girls who found their way to the factory through broadly similar paths. Both had to pick up factory work due to a family misfortune, and speaking about it brought them to tears. But the journalist was not particularly interested in painting a picture of the sentimental factory girl, a common trope in both the mainstream and labor press of the day. It was the work speed of the factory women, the “living machines” as he described them, that captured his attention. In an effort to disperse the dark clouds that the personal stories had cast on the shop floor, he switched to the hegemonic, national narrative of industrial work, and hailed the “working-class heroines” for serving the homeland by working with their “hands [which] had no difference from machines.”Footnote 2

Alongside the impressive work speed of the factory girls stood a related narrative in the pages of the early postwar Turkish press. Young working women attracted public attention as increasing demand for mostly imported, luxury items sparked fears of disordered femininity and engendered anxiety over blurring class lines. Struggling with a growing trade deficit, the Turkish parliament debated enacting a luxury tax. It was not only rich tradesmen and the middle class apprehensively following the news in the papers; the tax rumors also worried “the fathers of poor families” because “luxury had ceased to be the enjoyment of war profiteers, black-market sellers and hysterical women who have nothing else to do.” A new group of women suffered so much from this “incurable disease that ate out their minds and bodies” that they reportedly fell prey to tuberculosis because of their poor consumption choices. In the spot light were factory girls, who “spend half of their weekly allowance on nylon stockings and have to live on bread and cheese the rest of the week.”Footnote 3

In the cultural context of early postwar Turkey, the figure of the factory girl received increasing consideration. Representations of young working-class women oscillated between proud emphasis on their industrious, regulated work habits and condemnation of their selfish, mindless consumer behavior. On the one hand, an idealized image of young factory women emphasized their productive potential by metaphorically linking them with technology and mass production. However, an anxious, conservative view counterbalanced this proud, progressive message by highlighting the threats urban modernity posed to factory girls’ respectable femininity. If hyper-productive, sentimental factory girls like Ruhsan and Nazmiye generated pride and affection, working girls spending half their wages on nylon stockings and lipstick spawned anger and irritation. The first line in the story portrayed factory girls as model workers at the point of production, while the second presented them as a “problem” at the point of consumption. Taken together, they tell a third story about the emergence of a gendered construction of labor and its control within the fast-changing political, economic and cultural landscape of early postwar Turkey. The new gendered discourse on young women's industrial work was riddled with instabilities produced by a situation in flux.

I start with this lack of a sense of stable femininity, and unpack the juxtaposition of the two tropes about factory girls against the backdrop of the postwar expansion of capitalism in Turkey.Footnote 4 A quest for productivity and the emergence of a broader consumer culture were two of the key processes of that expansion. Young industrial women assumed center stage significance in both processes. Industrial experts and policy makers pointed at women's low labor force participation as one of the main reasons for high labor costs in production. Underpaid and disciplined young women formed a vital component of the workforce needed for tedious, repetitive, unskilled tasks. But what benefited capital, threatened the gender order. Factory work gave young women some limited independence and some money of their own, yet it also called their respectability into question, and controlled them through expectations about proper womanly conduct.

By asking contextualized political economy and representation-related questions of select sources produced by trade unions, state agencies, women's publications, and International Labour Organization (ILO) reports, I weave a social history of working girls in production with a cultural history of factory girls as conspicuous consumers. I build my argument on two interrelated premises. First, the labor market is a mental and cultural as well as an economic structure where historical actors negotiate a socially and culturally desirable order, and the processes of producing and affirming the socially desirable gender order are key to these negotiations.Footnote 5 Gender has historically been a fundamental and permanent structuring principle of the labor market; the culturally handed-down gender hierarchy has shaped accepted notions about who women workers are and what they need. The construction of working-class femininity is among the key principles of women's entrance into the labor market; it is also inscribed in the mechanism of labor control on and beyond the shop floor. Second, discourses have a material basis in established social institutions and practices, or as Aihwa Ong puts it, in the symbolic reproduction of capitalism. It is through this symbolic reproduction that gender differences become references on the basis of which labor-management relations are conceived, legitimized, naturalized, and criticized.Footnote 6 In early post-war Turkey, the two discourses on young women workers as metaphorical machines and mindless consumers communicated a normative framework of femininity that functioned according to the importance of efficiency and frugality, and informed the disciplinary practices employed to control young female laboring bodies at the point of production and consumption.

The article begins with a brief summary of postwar developments in Turkey. Next, I first locate Turkey within the international postwar trends in female industrial labor and then explain the incessant demand for female industrial labor. In the last two sections, I delve into the discourses on normative femininity as a gendered mode of discipline pertaining to the spheres of production and consumption.

Manufacturing and Consumption in Early Postwar Turkey

The Second World War was the catalyst for sweeping social and political change in Turkey. Despite her vital strategic location, the country managed to remain neutral for most of the Second World War, and was thus saved from physical destruction, but not from economic devastation.Footnote 7 Among the many postwar economic problems, two had a direct relationship to the discourses on working-class femininity: the persistence of low productivity in both manufacturing and agriculture, and the development of a dysfunctional consumer market. Together, they produced a complex interplay between workplace conditions and societal norms that brought the issue of young female workers’ femininity to the forefront.

Since the early 1930s, Turkish economic policy was mainly concerned with building a state-owned industrial establishment substantial in size. Post-imperial Turkey had emerged from long years of war and economic destruction with a new developmentalist plan and had embarked on an ambitious import substitution model of national industry building before state-led import-substitution industrialization spread throughout the developing world in the years after 1945.Footnote 8 Underlined by a sense of urgency and speed, the industrialization plan focused on manufacturing previously imported simple consumer goods for which internal markets and local raw materials existed and labor-intensive production methods could be employed. But the outbreak of the war impeded the prompt realization of Turkey's economic aspirations. By the end of the war, GDP was down to 1934 levels, and GDP per capita was 38 percent below the figure in 1939.Footnote 9 On top of that, Turkey's dependence on imports remained undiminished to any significant degree. In 1948, the percentage of imports paid for by exports was only 50 percent.Footnote 10

The protectionist, manufactured-based, state-led development strategy of the 1930s came under fire after the war, both from inside and outside the country. On the political front, almost two decades of one-party rule ended shortly after the war. Economically, the war years had had an expansionary effect on capital accumulation. Having accumulated a sizeable amount of capital thanks to war inflation, private industrialists threw their weight behind a rival, pro-business political party formed by a splinter group from the governing Republican People's Party (RPP). The liberal opposition, which was baptized as the Democrat Party in a direct criticism of the former's rule, had an overwhelming victory in 1950, thus ending 27 years of the RPP at the helm.Footnote 11

Cold War tensions developed rapidly in Turkey, the furthest geographical post of the noncommunist world. Interested in admission to new international organizations, and under pressure from Soviet territorial demands, the country came under the increasing influence of the North Atlantic coalition in the making. To qualify for International Monetary Fund membership and to partcipate in the Marshall Plan aid program, the government initiated a major economic policy change involving devaluation and a set of foreign trade liberalization measures. 1946 was a threshold year economically because it marked the end of the protectionist, inward-looking economic policy the country had followed since 1930. In 1946, the RPP devalued the lira by 54 percent against the US dollar, seeking to gain a competitive advantage before its entry into the Bretton Woods system. Devaluation, government officials claimed, would not only increase the value of the country's exports, it would also protect local manufacturing from imports.Footnote 12 One of the RPP's last actions in power was the establishment of the Industrial Development Bank of Turkey (Türkiye Sınai Kalkınma Bankası) under the auspices of American aid agencies and the World Bank to “orient [Turkish industry] towards its proper place in the world division of labor.”Footnote 13

Economic liberals at home and abroad welcomed the end of protectionism. They claimed that the government had chosen the wrong path to rapid development by investing in state-led manufacturing at the expense of agricultural growth, thus leaving 80 percent of Turkey's population underemployed, underproducing and underconsuming. The primitive status of agriculture and insufficient private industrial investment hindered productivity growth and domestic market expansion. By the end of the 1940s, Turkey's consumption level compared poorly even among low-income economies such as Portugal and Greece.Footnote 14 Authors of an American mission report underlined the “curious fact” that “in an intensive drive for industrialization and self-sufficiency, Turkey has not, within the twenty years since the program was implemented, provided enough capacity to supply even the modest wants of its population.”Footnote 15 While textile manufacturing had received the largest investment, out of a total population of 20 million people, they claimed, 17 million were insufficiently clothed. The war exigencies exacerbated the lives of peasants, who had already been living in the margins of subsistence, and the urban waged classes, whose real wages deteriorated.

Turkish industrialization, an economic historian argued, was an “artificial affair” because investment decisions did not take into account the absence of a large integrated national market and a poor infrastructure network.Footnote 16 In the postwar period, a consumer culture slowly but steadily emerged in the country, creating “a nation of contrasts” where “American motor cars dash by villagers on donkeys; a young Turkish girl who in dress and carriage would not be noticeable on Fifth Avenue strides along past an old woman in baggy trousers, with a veil below her eyes.”Footnote 17 In urban settings, the increase in American exports had begun to fuel a whole new economy of desire replete with cinema, print advertising, rotary presses, and new consumer goods during the interwar period.Footnote 18 The end of the war gave a new spin to this economy by increasing the commodities and cultural artefacts in circulation. This global trend coincided with the end of protectionist economic policies in postwar Turkey, fueling fraught discussions about import liberalization and the threats it posed both to local manufacturing and fiscal balance. The resulting language of economic nationalism was charged with concern about the increasing availability of imports, eventually instigating a “struggle against luxury” that combined economic concerns and moral anxieties.Footnote 19

In the realm of manufacturing, the struggle against imports was fought on two fronts. On one side was the protection of local manufacturing against the increasing competitive advantage of foreign products. Already in effect throughout the late Ottoman period, the idea to defend local manufacturing gained new life with the development of local import-substitution industries.Footnote 20 On the other side were the gendered anxieties over the degenerating effects of conspicuous consumption. The figure of the young factory woman was central to both.Young women's cheap labor would bring the production costs down, providing competitive advantage to local factories. But conspicuous consumption among young female workers disrupted the image of the industrious, altruistic and patriotic factory girl.

Liberal critics advocated for two central policies to fix the developmental problems in Turkey: transform agriculture from subsistence to a market orientation by increasing productivity, and increase the efficiency and competitiveness of Turkish manufacturing.Footnote 21 With regards to agriculture, machine-based productivity became the name of the game as American-financed machinery quickly revamped the agricultural sector. In 1946, the total value of machinery imports to Turkey was $18 million US dollars.Footnote 22 In 1949 alone, Marshall Plan aid authorities allocated more than twice this amount for the procurement of agricultural machinery and modern extraction and transport equipment.Footnote 23 “Tractor fever” swept the country. In the 12 years between 1936 and 1948, the number of tractors in Turkey increased from 961 to 1,750. That number grew five-fold from 1948 to 1949, and by 1952, there were more than 31,000 tractors in the country. One of the first industrial undertakings financed partly by foreign capital was a tractor plant.Footnote 24

Beyond supplying foodstuffs for domestic consumption and additional exportable products, the mechanization of agriculture increased the production of tobacco and cotton, two of the main raw materials Turkish manufacturing processed and two of the industries that widely employed female labor. Yearly production of tobacco more than doubled during the 1950s, increasing the value of Turkey's tobacco exports as well as domestic cigarette production. The kilograms of cigarettes produced by the monopolies increased from 9 million in mid-1930s to 15 million in 1945.Footnote 25 By the mid-1950s, domestic cigarette consumption reached 27 million kilograms.Footnote 26 As the principal industrial crop of Turkey, cotton production almost tripled between the mid-1920s to the late 1940s, but as late as 1946, the locally manufactured cotton goods accounted for only about 60 percent of Turkish consumption.Footnote 27 In the 1950s, yearly production of cotton increased from 54,000 bales to 212,000 bales.Footnote 28 With continued steady development after 1953, local cotton textile manufacturing finally met national demand.Footnote 29

Low industrial productivity had bothered policy makers since the mid-1930s, but their attempts to rationalize Turkish industry, mainly through the services of foreign experts in the 1930s and 1940s, proved largely ineffective. Notions of “efficiency” and “productivity” were articulated at an unprecedented scale with the increasing circulation of American industrial and managerial techniques in the postwar period. In the words of a contemporary academic, at the root of all the industrial problems in the country lay the high cost of production due to low labor productivity.Footnote 30 Similar to the 1930s, work intensification was viewed as the main mechanism to fix the problem. But, unlike in the 1930s, economic protectionism came under scrutiny as a culprit for low productivity.

Backed by foreign, mainly American, experts, the Democrats, as the opposition came to be known, attacked the exemption for inefficient and costly state enterprises from having to operate on a sound competitive basis. Some of them had such high production costs, a Democrat Party minister claimed in 1950, it would be ten times cheaper to import their products.Footnote 31 The remedy, they argued, lay in increasing foreign investment, staying away from heavy industry, focusing on expanding labor-intensive, private investment in light industries, and increasing local productivity.Footnote 32 Thus, began a second wave to enhance the productivity and global competitiveness of Turkish industry. In 1953, under the terms of a Turkish-American agreement, an interministerial committee was established to cooperate with the Foreign Operations Administration in developing productivity programs.Footnote 33 This was followed by the establishment of a National Productivity Centre in 1954.

Unlike the agricultural sector, the search for productivity in manufacturing was not machine-based. To begin with, both state and private factories had difficulties renewing their technical equipment which had gone through extreme wear and tear during the war years.Footnote 34 But even before the war, both local and European industrial experts extensively criticized the state as well as private industrialists for expanding facilities to increase production instead of improving the administration and management, and investing in labor training.Footnote 35 By the end of the 1940s, American experts joined the chorus. A report by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the lending arm of the World Bank, defined improvements in efficiency in both public and private enterprise as essential to the economic development of Turkey and claimed it did not require “much, if any, investment of funds.”Footnote 36 The deputy chief of an Economic Cooperation Administration mission claimed that the immediate problems in Turkey were of a “more elementary nature” compared to Western European countries, and thus the country needed “basic production techniques” rather than “refinements usually visualized in the concept of productivity.”Footnote 37 As with the earlier industrial experts, the Americans also pointed to wider and better implementation of scientific management techniques. The immediate effect of these developments on the shop floor was an increase in the work rhythm. Instead of engaging in technical transformations to sweat greater productivity out of workers, industrial managers chased increased levels of productivity through labor intensification that relied upon old technologies to achieve higher levels of productivity.

How did this new search for productivity effect young female workers? I argue that it placed young women squarely in the forefront of the working class as a key section of industrial workers for two reasons. First, industrial policy makers pointed at low female industrial labor participation as one of the main reasons for high production costs and thus low productivity. Expert reports documented how Turkey compared unfavorably not only to early industrialized economies, but also late industrializing ones in terms of female industrial labor participation.Footnote 38 Second, women's cheap labor became central to the expanded production of labor-intensive and low-value added goods which required the rapid performance of repetitive tasks.

The Incessant Demand for Female Industrial Labor

The 1950s presented a central contradiction with regards to expectations of women in the United States, Alice Kessler-Harris argues, because of the co-existence of a strong emphasis on women's obligations to the home and the insistence on their capacity to take jobs.Footnote 39 This contradiction is detectable in varying degrees in other contexts. Industrialization levels determined which of women's two roles was central to state and employer discourses. In war-torn, industrialized settings, integrating men back into the postwar industrial workforce preoccupied economic policy makers. Late-comers to industrialization, on the other hand, depended on a cheap female labor force to expand their light industries. Thus, the dramatic turn toward the domestic ideal in the early industrialized economies was not as strong in the circumstances of “catch-up” industrialization, where the historical emergence and significance of women in the industrial workforce gained a pronounced cultural dimension.Footnote 40 Postwar Turkey happens to be a perfect example of this.

Two political economic developments between the establishment of the Republic in 1923 and the end of the Second World War gave public opinion and state policy on female industrial labor in the postwar period a peculiar feature. Within the framework of secular state-building, the Kemalist regime had instituted a series of reforms concerning women's legal and civil status, including replacing the Islamic civil code with the Swiss secular code, abolishing polygamy, recognizing women's right to vote, and launching a nationwide campaign for girls’ education in the 1920s and 1930s. Women's new legal and social status under the Republic became the banner of Kemalist development narratives.Footnote 41 The second process concerned the economic policy choice of state-led industrialization after the Great Depression, explained above. And I argued elsewhere that a new ideology of women's work was articulated throughout this industrialization drive.Footnote 42 Women's changing status under the secular Republic created a set of state discourses that marked women's presence on the shop floor as emblematic urban industrial modernism. This newly acquired status did not improve women's experience on the shop floor, however. Women entered the industrial workplace as subordinate individuals and worked in a strictly hierarchical labor market divided by sex (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Factory girls at a textile factory posing with their foreman at the center, 1950. Courtesy of Ergin Aygöl.

Despite the celebratory presentation of women on the shop floor, the share of women in the industrial workforce remained below 30 percent. Industrial experts pointed at this low female participation rate as one of the main reasons for low productivity. In report after report, they emphasized the need to tap the reserve army of female labor. In the postwar period, the Turkish government extended its regulatory power over the labor market, joining various other governments in launching publicity campaigns to encourage women to either enter or stay in the labor force.Footnote 43 The Ministry of Labor, established in 1945, listed among its primary objectives making better use of the reserve of female labor, and set out to encourage “our women to commit to our work life [and] to motherhood.”Footnote 44

The celebratory press coverage of women's industrial labor in the 1930s and ’40s revealed scant knowledge of how women's industrial labor was actually organized and experienced on the ground. The emphasis in these early depictions of factory women was on how the secular state had bestowed women with the right to work, or in broader terms, the right to public space. The availability of a specific group of workers in the social space of the labor market is determined by, among other things, the social constructs of the group's identity. In Turkey, the identity of factory women was formed on the basis of their alleged emancipation from religious bigotry and legal discrimination. Building on that identity, the expectation of women as good citizens in a reserve labor pool was that they would respond to the obligations of national economic reconstruction and realize their productive and patriotic potential. With the appearance of the mechanistic metaphors about women's labor in the postwar period, the emphasis shifted to the feminine values of diligence and industriousness.

As in other industrial contexts, the war experience affected this shift. In 1939 alone, one million men were enlisted out of a total population of 17 million. Between 1935 and 1945, the percentage of women and children working in the textile industry increased to 54.9 percent from 41 percent and to 16.6 percent from 6.6 percent, respectively.Footnote 45 The already widespread use of child labor in the textile industry expanded even further with the percentage of workers younger than 14 years old rising to to 8.7 percent in 1945 from 6.3 in 1935.Footnote 46 It is a well-documented fact that the war experience altered employers’ perceptions of female workers, and proved that “women could function well in jobs that had previously been male domains.”Footnote 47 Such was the case in Turkey. In the official journal of the Ministry of Labor, a male writer happily reported that women's performance during the war both at home and at work disproved assumptions about them being “slow in the head, sluggish, easily bored, limited in creativity, and fickle.”Footnote 48 The newly emerged labor press published photos of proud factory women and praised their “great success even in the hardest jobs” and their entry into new sectors.Footnote 49

And then there were the employer testimonials. In the summer of 1947, a female parliamentarian visited 80 factories in Turkey as part of a parliamentary mission and penned a series of articles based on her observations for the Women's Newspaper, a social and political newspaper that followed the state feminist line. She first noted the increase in the number of women and girls on the shop floor, which she explained was partly the result of war enlistment and partly due to intensifying economic hardship. She then described employers’ surprised satisfaction with female workers, especially their capacity to work hard and their speed in acquiring skills. Despite carrying the heavy burden of domestic work on their shoulders, she continued, women's productivity was outstanding.Footnote 50 A male writer took these observations one step further and claimed that “in many respects, women workers are reported to be superior to men.”Footnote 51 But what exactly did he mean by “superior”? To answer that question, we need to delve into the machine symbolism deployed in narratives about working girls.

Of Factory Girls and Machines

Decades before cheap labor by nimble-fingered, female, assembly-line workers became a widespread image, and their labor came to be described through allusions to the imagery and vocabulary of machines, working women were frequently described as metaphorical machines in early postwar Turkey.Footnote 52 Almost hypnotized by their work speed, journalists were awestroke by the young working women. “One would never get bored of watching them working like ants,” a female reporter wrote in 1947, recounting the pleasure she derived from the synchronization and pace of their movements.Footnote 53 Later that year, the same journalist visited the Cibali Cigarette Box Factory, where we found Ruhsan and Nazmiye at the beginning of the article. Amazed by the fierce competition among the mostly young and female workers, she described them as “workers with higher productivity than machines.”Footnote 54 Accompanying this “dizzying speed,” as described by yet another visitor, was “joy and harmony” among “the machine-like mass of women workers.”Footnote 55

The strong allusions to machinery in the depictions of female industrial bodies are intriguing on their own. Read against the multiple historical narratives on the tension between femininity and the machine, and more specifically, the horrific physical and moral effect machines had on female bodies, the intrigue grows. Both conservatives and radicals writing about mechanization in the nineteenth-century saw machines as instruments of torture inflicted on the female body.Footnote 56 The overworked, fatigued factory woman has been one of the most universal and enduring symbols of the human costs of mechanization. Provoked by the mechanization of the garment industry, which transformed women's manual labor of sewing, Jules Simon, in his 1860 book L'ouvrière, powerfully summarized the widespread anxiety over women at machines by contrasting “the peaceful spirituality of womanhood” with “the violent disruptiveness of the machine,” or “the demonic automatons” with “icons of feminine traditionalism.”Footnote 57

A notable exception to the narrative came from Harriet Martineau, the prominent British writer and political activist. In her Illustrations of Political Economy (1832–1834), Martineau claimed women were the greatest beneficiaries of recent mechanical innovations. After returning from her factory visits with eyes aching from watching women's intense and monotonous labor, she wrote that female bodies acquired almost superhuman skills and strengths by working on machines. Women workers overcame the limits of normal eyestrain, developed “unusual strength” in their wrists and arms, and their fingertips became so broad and their joints so flexible that they could bend them considerably backward when in use.Footnote 58

A precursor to Karl Marx's depiction of the metabolic overlap between the human body and the machine, which presented such an integration as a dehumanizing form of submission, Martineau's enthusiastic blurring of the lines between the female body and the machine was motivated by an urge to overcome women's labor market marginalization.Footnote 59 An outspoken champion of women's rights and a vehement advocate of equal pay for equal work, she established a definite compatibility between machinery and femininity to challenge gendered divisions of labor, which confined women to cheap labor and limited their access to mechanized production. Documenting women's aptness for industrial labor in a quickly mechanizing industrial environment was important to Martineau because “where it is a boast that women do not labor, the encouragement and rewards of labor are not provided.”Footnote 60 But what about contexts such as early postwar Turkey where it was a boast that women labored? Where do we locate the mechanical enthusiasm we find here in the range between Simon's fear and Martineau's keenness?

In terms of timing and scale, Turkish industrialization lagged significantly behind the settings where women's mechanized labor came to be seen as a modern social problem. As social commentators grappled with the accelerated pace of mechanization in the nineteenth century, Ottoman industrialists were trying to build manufacturing; a century later, the extent and structure of Turkish industrialization was still quite limited although the state-led industrialization drive of the 1930s and 1940s had made important gains. The female industrial proletariat remained small in size, but industrial women received attention disproportionate to their number. Factories emerged as national spaces that displayed and enforced modern gender relations. Speaking of late-industrializing contexts, Dina Siddiqi observes that “women at the machine in factories heralded a kind of modernity.”Footnote 61 In the instance of Turkey, the new centrality of gender to secular state-making invoked the image of women at the machine as proof of the emancipating possibilities of industrial modernity. It was aspiration to that kind of modernity which lay behind the enthusiastic depictions of women as machine-like, joyful workers instead of workers caught up in “the trauma of industrialization.”Footnote 62

In the context of a widely popularized state ideology stressing women's emancipation under the secular republican regime, middle-class observers based their romantic, celebratory representations of women's industrial labor on three interrelated premises. Firstly, women's presence on the shop floor strengthened the country's Western identity. Secondly, they claimed women were drawn into industrial work by the allure of patriotic service as we saw in the portrayal of Ruhsan and Nazmiye as working-class heroines. Last but not least, the depictions reinforcing the idea of women's aptitude for industrial labor responded to the then-recent, ethno-religious change in the female industrial workforce.

Turkish-Muslim women made their way into factories in the first two decades of the twentieth century, when much of the Ottoman industrial labor force was removed through deportation and emigration. Their numbers increased first with the onset of the war, and then with the 1923 population exchange with Greece, which resulted in the loss of not only an important source of cheap labor, but also artisanal skills, particularly in urban areas.Footnote 63 Though on a much-reduced scale, the question of the ethno-religious composition of the industrial workforce remained relevant until the end of the 1940s. In 1949, the owner and editor of the Women's Newspaper joined the large chorus of statesmen, industrialists and middle-class intellectuals calling women to the factories. In her aptly titled piece, “The Economic Duty That Falls On Our Womanhood,” she raised the issue of non-Muslim women working outside the home:

That we have a shortage of labor and entrepreneurship is a well-known fact […] We see so many [women] working in hat and padding making and tailoring to help their families get by during these hard times. There are so many similar professions that we hesitate to go into in fear of breaking social norms although the [non-Muslim] minorities among us earn money by making their women work like machines.Footnote 64

Encouragement for women to join the workforce was there, and it had strong nationalist undertones. But what exactly happened when women took up industrial jobs? Despite the celebratory representations, the benefits seemed to be miniscule. Although middle-class women assured their working-class sisters that the enlightened state would protect their rights as workers, women's marginalization continued, and woman-protective legislation remained limited and focused on women's maternal roles.Footnote 65 The rigid sexual hierarchy within the production process maintained the mechanisms to profit from socio-culturally acceptable low female wages and from the gendered notion of women's suitability as docile, more dexterous workers for labor-intensive work.

Feminist scholars have documented the way in which these mechanisms have worked in both historical and contemporary contexts.Footnote 66 To a great extent, gendered assumptions about work in postwar Turkey adhere to well-known tropes of women's unique capabilities, soft skills and essential qualities. Policy makers, employers, managers, and middle-class observers of women's industrial labor explained women's hyper-productivity as an extension and efficient utilization of their innate capacities. Describing his excitement over “watching thousands of women workers struggling with the volume of work,” one writer reported that their fingers worked so fast that no matter how hard he tried he could not follow their movement.Footnote 67 At first glance, he wrote, “it looks like magic,” but it was nothing more than a “quite advanced meleke,” an Ottoman Turkish word with the primary meaning “natural capability.”Footnote 68 When another journalist asked the director of a state textile factory whether women “met his productivity expectations,” the director assured her that they were not different from men at all, in fact “their productivity is actually higher in delicate jobs.”Footnote 69 The Ministry of Labor attributed the increase in the number of factory women in Istanbul to employers’ preferences for “cheap and dexterous female hands.”Footnote 70 Factory inspectors used international examples to emphasize that patience and dexterity were superior to muscular strength in the textile industry, and underlined the urgent need to recruit more women to textile factories to counteract “the negative effect [of their low numbers] on the cost of production.”Footnote 71

What then was peculiar to early postwar Turkey with regards to the gendered discourses on skill and productivity? I argue that the discourses had two peculiarities. First, the naturalization of women's skills is sustained by a merging of gender and ethnic-national identities. When the vocabulary of skill is applied to women's work, Helen Harden Chenut argues, “it evokes mythical images of patience, perseverance and silent craft.”Footnote 72 That mythical image took on an ethnic-national character in Turkey. Behind the representations of female factory hands as “the diligent Turkish women” lay the motivation to assert their aptness for industrial labor in comparison to the non-Muslim women on the local level and “the Western women” on the international level. A convergence of racist and sexist stereotypes elevated industrial efficiency into a gendered, nationalist aesthetic ideal and inscribed “the patience and the endurance of the Turkish women” onto young working women's bodies.Footnote 73

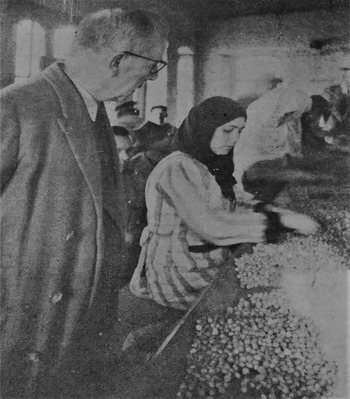

Second, in most representations of women's machine-like bodies in postwar Turkey, there was no machine involved. This was especially the case in tobacco and cigarette manufacturing (see Figure 2). In the 1930s and ’40s, the mainstream press proudly reported on how the nationalization of tobacco manufacturing in 1925 progressively mechanized the “technologically impoverished tobacco and cigarette factories.”Footnote 74 What they did not report was the gendered access to technology in these factories. It was mostly male workers who operated the new machines, while women remained in traditionally sex-typed occupations such as the manual separation and sorting of tobacco leaves. In the manufacturing of cigarette boxes, for example, the printing and cutting was completely mechanized. But women placed paperboards into the machine-cut cartons and attached the upper lid by hand.Footnote 75 When the director of the factory said women worked so well that “some of them compete with machines,” he was referring to this manual labor.Footnote 76 However, it did not mean that mechanization had no affect on women's work. By speeding up men's work, machines increased women's work rhythm indirectly (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Working girls at the Cibali Tobacco Factory between 1935 and ca. 1947. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Figure 3. Prime Minister Şükrü Saracoğlu observes a young woman working in a hazelnut processing plant. Çalışma no. 1, September 1945.

But what about the instances when women actually tended machines? Then their role was mostly confined to watching the equipment to make sure it was operating smoothly. In workshops where women and men worked together, women's subsidiary role was made clear by their classification as auxiliaries; women had job titles such as “weaver helper,” for example. Skill requirements and job training were organized in such a way that, when they worked with machinery, women had to have male overseers to repair and adjust machines. In the cotton textile industry, where spinning was mostly a female job and weaving a mostly male job, women's work rhythm increased with the automation of weaving looms.

So then what lay beneath the machine as the central metaphor around which discourses on female industrial labor were structured? Manufacturing capital in postwar Turkey chased labor-intensive productivity gains that were not accompanied by machine investment. Women's labor played a key role in the reshaping of the labor process to become more efficient, coordinated and specialized. It was not women's actual work at machines that informed depictions of their body movements as machine-like, but the ordering and perfectibility of the female industrial body on the model of the industrial machine, which came to “represent fetishized extensions of workers bodies.”Footnote 77 Through signifying rhythm, continuity and order, the metaphor of the machine served as the paradigmatic expression of discipline over the female laboring body. Besides the focus on specific women's hyper-productivity, the metaphor surfaced in descriptions of the body choreography on predominantly female shop floors. The figure of the machine functioned as a model for work organization in these descriptions, where women's ability to synchronize and coordinate work made them look like the moving parts of a machine. Finally, the metaphor of the machine was not merely a means of representation, but also a means of labor control. In addition to regulating women's sexed bodies on the shop floor, the idea of the machine became a means for molding those bodies along an industrial model that encompassed all facets of working women's existence, including their eating habits, grooming customs, leisure pursuits, and courtship.

Factory Girls, Consumer Culture and Gendered Social Control

In addition to the pressures of work speed-up at the point of production, young working women in early postwar Turkey increasingly came under a socio-cultural regulation of femininity at the point of consumption. To be sure, the social criticism, which used “luxurious consumption” as a symbol of moral and social decadence, was not confined just to working women. The expansion of the consumer market carried the weight of larger concerns about the character of modern femininity and its bearing on the moral future of the nation. The morality of consumption placed the nation's women as a whole in the spotlight: the image of the female consumer was the focus of national popular anxieties over the social order as well as economic development.

The portrait of the female consumer increasingly served to filter out wasteful consumers from responsible citizens. In popular and political discourse, the two extremes of that image were the female consumer as a potential traitor who put her fellow nationals at risk by purchasing imports, and the female consumer as a diligent and patriotic homemaker. Any consumption pattern that did not comply with the family-centered model supporting local manufacturing was promptly rejected. Women's consumption acquired a whole new meaning when it concerned the working-class fashion devotee, who, in taking pleasure in fashion and leisure, not only exceeded the bounds of legitimized femininity, but also transgressed class boundaries. Because fashion served as a display of class distinction and taste, and expressed class hierarchies, middle-class elites viewed working women's appropriation of fashion as crossing class boundaries through overconsumption to fulfil their desire for unaffordable goods.

Historically, middle-class concern about the unbridled consumerism of working-class women coalesced around the idea of the factory girl as an emblem of female self-assertion.Footnote 78 Often, these sentiments were accompanied by disapprobation of wage-earning woman as a symptom and symbol of masculine degradation.Footnote 79 This was not the case in postwar Turkey. In keeping with the secular regime's celebration of women's public visibility and the incessant demand for female industrial labor, judgements over the frivolous factory girl were not disapproving of their work. For middle-class commentators, the threat to young working women's reputations did not come from the hazards of factory labor. On the contrary, most women workers protected their reputations “thanks to the moral disciplining work provides.”Footnote 80 Instead, dangers to proper womanly conduct originated in the realm of consumption, and thus managing this female desire emerged as a powerful tool in the social regulation of working-class femininity.

Baron and Boris conceptualize normative definitions of working-class sexual practices and rules about appearance as “technologies that enhance managerial control over workers.”Footnote 81 In early postwar Turkey, commentaries on working women's displays of femininity on the shop floor focused on two broad themes. Firstly, local socio-cultural meanings and mechanisms of gender intertwined with nationalist and ethnicized ideals of Turkish womanhood. The question of how young working girls in Turkey compared to “Western women” preoccupied a writer for a trade union newspaper. Citing the observations of an American visitor to the country, he complained bitterly that working women in Istanbul looked like “Hollywood women.” Why would a working girl embellish herself, he rhetorically asked and answered, if not for that shameful motive known to everybody? Thus having insinuated that the painted woman was a figure of deception and alterity, and an inauthentic self, the writer went on to point to the modest style choices of English working women as the example to follow in order to command respect on the shop floor.Footnote 82 Idealizing a natural appearance also found an ethnicized expression in that “Turkish women” did not need embellishment because they already looked like “precious pearls…blessed with natural beauty.”Footnote 83

The second theme connected to young working women's familial and national duties. The ephemeral satisfaction derived from wasting money on finery was contrasted to “the peace of mind that serving one's self, family and the homeland” brought. The source of “real beauty” lay in this kind of service as opposed to the fake attractiveness achieved by buying imported cosmetics and fashionable clothing.Footnote 84 The last verse of an unsigned poem called “Working Girls” published in a trade union newspaper in 1948 offered a vivid account of how the ideal working girl was imagined:

Forget her thinness, that she stands on her feet is what matters

So what if her wrists are not adorned with gold jewelry?

Her spotless heart makes her beautiful

Benefiting the homeland is her ambitionFootnote 85

The poem resolves the disquiet prompted by financial freedoms and expressions of beauty culture by comparing and contrasting. The young working girl is underweight but independent, although we learn from one of the previous verses that she and her mother work together in order to take care of the girl's sick father. Independence here stands for the young woman's ability to provide for her family. She does not have jewelry, but she does not need it to be beautiful. She has overcome unworthy “feminine” emotions in order to devote herself to a higher cause, in this case, her family and national industrial development. Benevolence, modesty and a tireless concern for the welfare of others are defined as the basic components of young working-class female identity.

What happened when working girls deviated from this ideal of normative femininity? A short story titled “The Real Lover” also published in a trade union newspaper addressed this question through the story of Emine, an exemplary spinner who fell victim to seduction.Footnote 86 The tale opens with a description of the spinnery immediately followed by an admiring description of Emine's own industry. In both, the author moves between organic and mechanic metaphors: the spinnery operated day and night like “a steel heart,” Emine had “steel-like nerves” and her brain worked with “the accuracy of a Swiss watch.” But things changed. Once the most cheerful, hardworking, and orderly worker at the factory, Emine's demeanor became timid and depressed. Her face paled. Her laughter, which used to “blend like music into the machine noise” stopped, and her mind became foggy. She used to be sharply focused during her 12-hour night shift, but now her mind constantly wandered to the enticements of urban life. But above all else, she was preoccupied with Hüseyin, a male worker who had recently “stirred Emine's pure and calm life like a muddy stick.”

The two factory workers met through a chance encounter, after which Hüseyin followed Emine to her factory every night until he gained her trust. His constant talk about the pleasures of urban life led Emine slowly to lose all interest in work to the point that she neglected her beloved spinning machine. After days of absenteeism and multiple warnings, Emine quit her job. At first, she felt deep relief, her joy returned. The lovers walked the streets of Istanbul hand-in-hand, going to movies and patisseries. But after only a week, her mother no longer had money to buy food and the local shopkeeper refused to sell to the family on credit. But, according to the story, this was only part of Emine's misery. Being away from the factory caused her physical and mental suffering. Her fingers missed the spinning machine, her ears yearned for the sounds of the factory. Feeling like a castaway on a desert island, Emine found her eyes searching for the familiar faces of her co-workers. In the end, she returned to the factory. “This was a sight worth seeing,” wrote the author. A teary-eyed Emine embraced her spinning machine crying out, “My true lover! My joy, my life!”

Whether she was a “real” factory girl or the figment of some writer's imagination, Emine's story is a perfect example of the sentimental factory girl literature that worked to control women.Footnote 87 By illustrating how normative femininity travelled between the spheres of production and consumption, it demonstrates the socio-cultural tensions over female body autonomy in a changing economy. The narrative reinforces three key discourses on young women's work amidst the shifts, instabilities and contradictions of an economic and cultural system in motion. Firstly, it was not industrial employment but urban leisure and mindless consumption that could morally corrupt a factory girl. Far from posing a danger to young women, factory work could deliver them from degradation. The emphasis on the positive experiences of work obscured the realities of industrial work for young women. That Emine worked 12 hours a day on a cramped, noisy shop floor (the spinnery was located on the second floor of a large commercial building) or that only one week of unemployment dragged Emine and her mother into poverty do not concern the author. Secondly, for factory girls, despite the allure of modern urban life, the only possible source of real pleasure was devotion to their family and factory. Finally, the pleasure of work found its expression in an erotic union between Emine and her sexually charged machine. Unlike historical examples where machines were gendered as “feminine” when used by female operators, Emine's machine was gendered as male.Footnote 88 And accordingly, although she was the operator, the machine controlled Emine's psyche on and off the shop floor to the extent that any other union constituted a betrayal.

Conclusion

A country in transition was the backdrop for both the hypnotizing effect young factory women's productivity had on middle-class commentators and the heightened concern over the emergence of the “frivolous factory girl” in postwar Turkey. As the ideology of productivity and the expansion of the consumer market brought young, working-class femininity to the forefront of public discussion, images of young factory women alternated between the industrious worker devoted to her family, and the irresponsible consumer in danger of losing her female respectability. The young female worker was praised for her physical speed and endurance, but at the same time condemned for violating acceptable forms of femininity, for embarrassing herself, her family and her nation. Within this new industrial order, cultural references to femininity and productivity circulated inside and outside of the industrial workplace, and labor control went well beyond the domain of production when the categories of subordination, age, and gender intersected.

Behind mechanical metaphors praising women's hard work and productivity was an effort to prove that women were fit for industrial labor and to present factories as desirable workplaces for them. Admiring depictions of women's labor did not signal a change in the hierarchical typing of jobs, however. There were barely any signs of improvement in the working conditions to which unskilled and semiskilled female workers were subjected. Women entered the industrial workplace as subordinate individuals and worked in a strictly hierarchical labor market divided by sex. They were concentrated in manual, low-tech occupations and were paid accordingly. In many cases, women depicted as machine-like did not even work with machines. The metaphors were not directed at their mechanical prowess, but rather at how their skilled bodies performed like machines.

A combination of the economic indispensability of female labor and the anxieties over working-class femininity provided an excuse for greater public control to be exerted over young, working-class women. The result was the formulation of a new industrial femininity that naturalized, and thus enabled gendered labor control over women both as producers and consumers. Zeroing in on femininity provided a pretext for brushing off the harsh realities of young women's industrial labor. In this article, I have focused on the construction of that gendered control at and beyond the workplace. It still remains to be written how factory girls responded to that control, especially in the framework of the fast-developing trade union movement and the socio-economic transformation the country underwent beginning in the late 1950s.