Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a public health crisis that has affected the entire healthcare community. Although much of the focus of the pandemic has been on acute-care hospitals, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has identified dental healthcare personnel (DHCP) as being at high risk for work-related COVID-19 exposure due to direct contact with aerosols and respiratory droplets from unmasked patients. Reference Brunello, Gurzawska-Comis and Becker1–Reference Peng, Xu and Li3

The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the importance of adequate training in personal protective equipment (PPE) to reduce risk of exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19. Early in the pandemic, many DHCP voiced concerns related to limited knowledge of infection control methods, PPE availability and use, and personal health. Reference Bastani, Mohammadpour and Ghanbarzadegan4–Reference Estrich, Gurenlian and Battrell6 Although recommendations and guidance for dental clinics were available from OSHA and professional organizations such as the American Dental Association, little is known about the real-world application of these recommendations. 2,7,Reference Estrich, Mikkelsen and Morrissey8

Limited data have been published documenting how the COVID-19 pandemic affected DHCP usage of PPE and how DHCP adapted their clinical practices to protect themselves from COVID-19. Reference Banaee, Claiborne and Akpinar-Elci5,Reference Malandkar, Choudhari and Kalra9–Reference Estrich, Gurenlian and Battrell11 The purpose of this study was to characterize PPE use during the COVID-19 pandemic and to develop and pilot test an educational video on proper PPE donning and doffing procedures for use in dental clinics.

Methods

Study design and recruitment

This study was a qualitative analysis of 2 sets of semistructured interviews. The study included DHCP from 8 dental clinics in a Midwestern metropolitan area: 3 community-based general clinics, 3 community-based pediatric clinics, an academic clinic, and a hospital-affiliated pediatric clinic. Clinics were recruited through snowball sampling. DHCP with clinical care responsibilities and experience using PPE were eligible to participate. The study took place from September through November 2020 and from March through October 2021. Participants provided written, informed consent. The Washington University Human Resources Protections Office and the St. Louis University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Interview 1

Donning and doffing PPE. This study was performed in conjunction with an assessment of donning and doffing PPE methods. Reference Reske, Park and Bach12 After donning and doffing, individual semistructured interviews were conducted in person to characterize PPE use during the COVID-19 pandemic. The interview guide and questions are summarized in Appendix A.

Donning and doffing educational video. Qualitative and quantitative data from the donning and doffing interview were reviewed and analyzed to develop an educational video tailored to DHCP. 13 This video demonstrated donning and doffing in accordance with US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance. 14

Interview 2

Video feedback. After reviewing the educational video, DHCP participated in individual and group semistructured qualitative interviews to obtain feedback on the relevance and usefulness of such a tool for DHCP. Interview questions are summarized in Appendix B.

Assessment

Audio files were transcribed and coded independently by 2 study members trained in qualitative research methods. Thematic patterns were identified using deductive coding. Discrepancies between coders were resolved through discussion. Study team members selected representative quotations from common themes for the results.

Results

Participation included 70 DHCP in the donning and doffing interview and 62 DHCP in the video feedback interview (48 DHCP participated in both). Demographic and occupational background were available for the 70 participants who participated in the donning and doffing interview. Ages ranged from 19 to 70 years, and 78% were female. More than half (54%) reported ≥5 years of clinical experience, and 23% had ≥10 years of clinical experience. Dental assistants and hygienists accounted for 54% of participants; dentists or dental residents accounted for 46%.

Interview 1: PPE donning and doffing practices

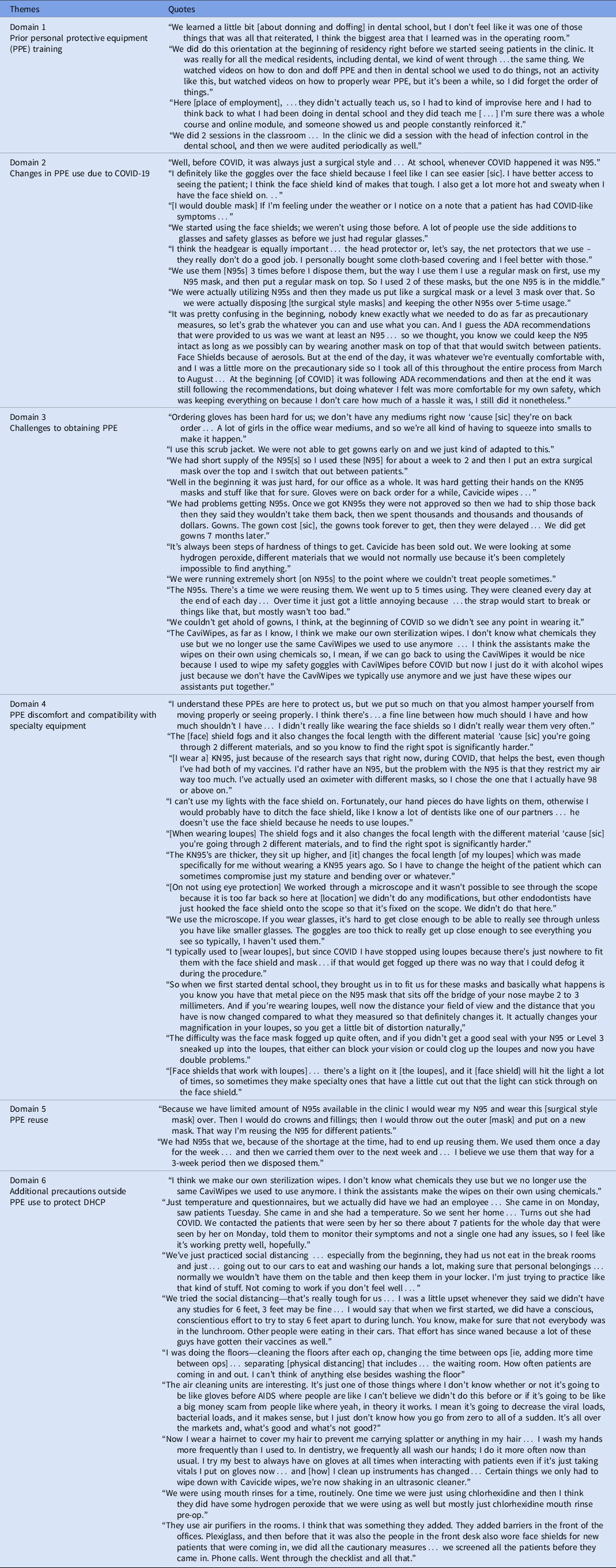

Interviews after donning and doffing were coded into 6 thematic domains. Interviews are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Themes and Quotes From Donning and Doffing Interviews

Domain 1: Prior PPE training. Overall, 60 (86%) of 70 DHCP reported receiving some prior PPE training. Among them, 36 (51%) received PPE training on the job, and 31 (44%) had received training in residency or other formal education. Only 10 (14%) of these 70 DHCP had received this training through an educational video. One DHCP said, “We did this orientation at the beginning of residency right before we started seeing patients in the clinic. It was for all the medical residents, including dental, and we went through kind of the same thing; we watched videos on how to don and doff PPE.” Similar experiences with previous PPE training were reported among 27 (84%) of 32 dentists and dental residents as well as 28 (85%) of 33 dental assistants and hygienists. Of the 61 DHCP who had received prior PPE training, 13 (21%) had received multiple forms of training.

Domain 2: Changes in PPE use due to COVID-19. DHCP reported increased use of N95 respirators and changes in eyewear due to COVID-19. When asked about mask use, 59 (87%) of 68 DHCP reported using N95 respirators. For example: “Before COVID, it was always just a surgical style [mask] and… whenever COVID happened, it was N95.” Among DHCP asked about N95 respirator fit testing, 24 (71%) of 34 reported having undergone formal fit testing. Fit testing was significantly less common among community DHCP compared to academic and hospital DHCP (47% vs 100%; Fisher exact P < .01).

Among these 70 DCHP, 37 (53%) reported wearing eyewear that included face shields, 36 (51%) wore safety glasses or glasses, and 14 (20%) wore goggles; 22 (31%) reported using multiple forms of eyewear. Of the DHCP who wore eyewear, 45 (71%) of 63 wore eye protection that met CDC guidelines. DHCP reported choosing eyewear based on factors such as size and compatibility with specialty equipment. One DHCP said, “I definitely like the goggles over the face shield because I feel like I can see easier [sic]. I have better access to seeing the patient; I think the face shield kind of makes that tough.”

Domain 3: Challenges to obtaining PPE due to COVID-19. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, DHCP experienced challenges with obtaining PPE, including gloves, disposable gowns, and N95 respirators. One DHCP said, “Ordering gloves has been hard for us; we don’t have any mediums right now ‘cause [sic] they’re on back order… A lot of girls in the office wear mediums, and so we’re all kind of having to squeeze into smalls.” These challenges also affected what PPE DHCP used. One DHCP said, “I use this scrub jacket. We were not able to get gowns early on and we just kind of adapted to this.”

Domain 4: PPE discomfort and compatibility with specialty equipment. DHCP experienced difficulties using PPE, including compatibility with specialty dental equipment and physical discomfort. When prompted about challenges wearing PPE, face shields were commonly mentioned due to size, incompatibility with other equipment, and interference with mobility or ability to see. One DHCP said, “I understand these PPEs are here to protect us, but we put so much on that you almost hamper yourself from moving properly or seeing properly… I didn’t really like wearing the face shields, so I didn’t really wear them very often.”

Among DHCP asked about specialty equipment, 28 (46%) of 61 reported using items such as loupes, light attachments, or microscopes. Among the 28 DHCP, dentists (24 of 28, 86%) were more likely to report using specialty equipment than dental assistants (4 of 28, 14%). Of DHCP who used specialty equipment, 17 (61%) of 28 said PPE interfered with their ability to see and use equipment appropriately. On discussing loupes and face shields, one DHCP said, “The [face] shield fogs and it also changes the focal length with the different material ‘cause [sic] you’re going through 2 different materials, so… to find the right spot is significantly harder.”

DHCP reported challenges with wearing an N95 respirator. Physical discomfort was a commonly reported factor for not wearing an N95 respirator. One DHCP said, “[I wear a] KN95… I’d rather have an N95, but the problem with the N95 is that they restrict my air way too much. I’ve actually used an oximeter with different masks, so I chose the one that I actually have 98 or above on.” Another DHCP mentioned that improper N95 respirator fit led to fogging of loupes during use.

Some DHCP eliminated use of specialty equipment all together. One DHCP said, “I typically used to [wear loupes], but since COVID I have stopped using loupes because there’s just nowhere to fit them with the face shield and mask… if that would get fogged up there was no way that I could defog it during the procedure.”

Domain 5: PPE reuse. A variety of methods were used to extend PPE use. For example, 26 (44%) of 59 DHCP who used N95 respirators also mentioned sterilization techniques, such as ultraviolet (UV) light, autoclave, and use of a baby bottle sanitizer machine. Many DHCP also reported wearing a surgical mask over their N95 respirator to preserve and facilitate its extended use or reuse. One DHCP reported, “I would wear my N95 and wear this [surgical mask] over. Then I would do crowns and fillings; then I would throw out the outer [mask] and put on a new mask. That way I’m reusing the N95 for different patients.”

Domain 6: Additional precautions. Temperature checks and health screening questionnaires were most often used for both patients and DHCP (14 of 67, 21%). Additional precautionary measures implemented included rinsing a patient’s mouth with antiseptic, more frequent sanitization of floors and surfaces, installation of air purifiers and enhanced ventilation, and making homemade disinfectant wipes in the clinic. One DHCP said, “We were using mouth rinses for a time, routinely. One time we were just using chlorhexidine and then I think they did have some hydrogen peroxide that we were using as well, but mostly just chlorhexidine mouth rinse pre-op.”

Interview #2: Training Video Feedback

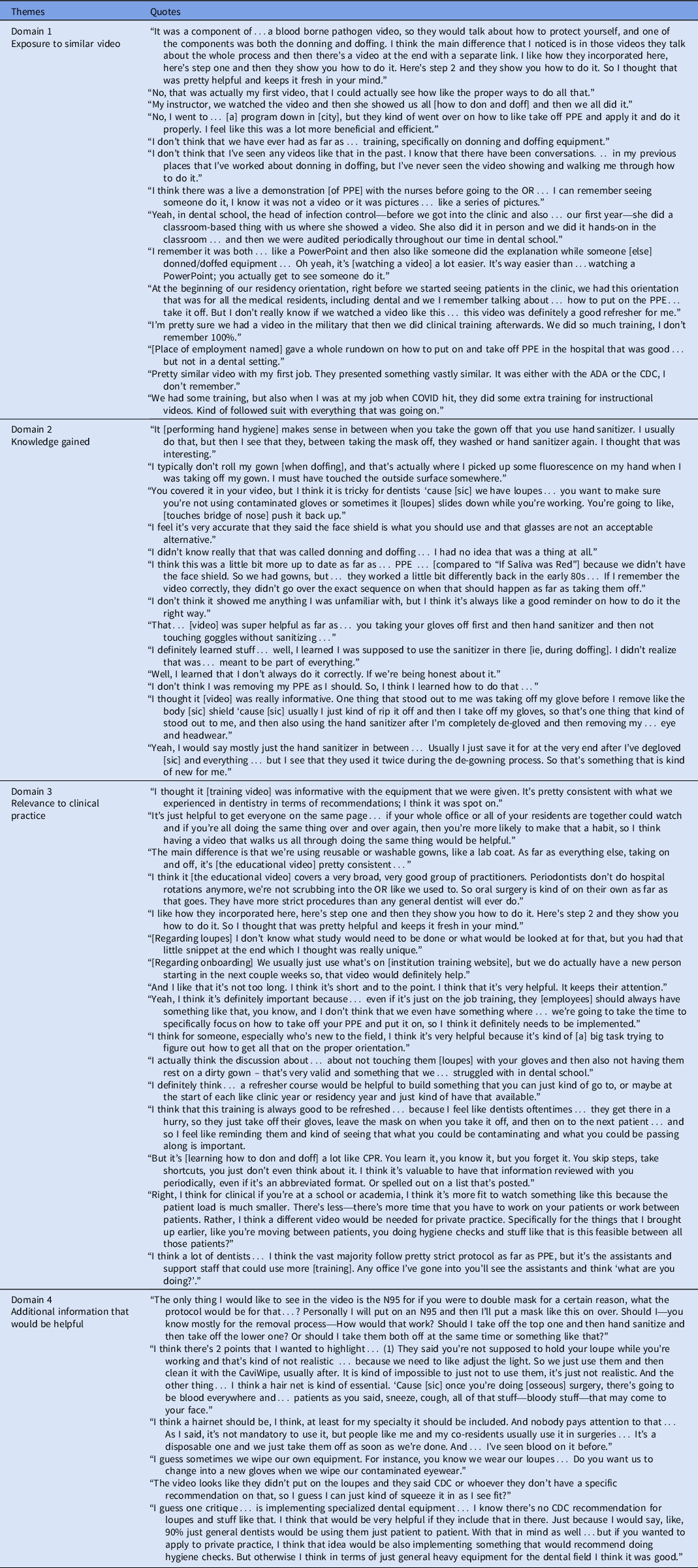

Overall, 62 DHCP provided feedback on the PPE training video, most of whom responded positively. One DHCP shared, “I thought it [video] was informative with the equipment that we were given. It’s pretty consistent with what we experienced in dentistry in terms of recommendations; I think it was spot on.” Responses were coded into 4 thematic domains. Training video feedback is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Themes and Quotes From Video Feedback Interview

Domain 1: Exposure to similar video. When asked about previous exposure to an educational video, 26 (43%) of 60 DHCP reported having seen a similar video. One DHCP said, “I think the main difference that I noticed is in those [other] videos they talk about the whole [donning/doffing] process and then there’s a video at the end with a separate link. I like how they incorporated here’s step one and then they show you how to do it.”

Of the 26 DHCP that reported exposure to a similar educational video, 11 (42%) cited “If Saliva Were Red,” a dental infection control and safety educational video created by the Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention. Reference Eklund15 One DHCP said, “I think this was a little bit more up to date as far as… PPE… [compared to “If Saliva Were Red”] because we didn’t have the face shield… If I remember the video correctly, they didn’t go over the exact sequence on when that should happen as far as taking them [PPE] off.”

Domain 2: Knowledge gained. Common feedback included increased knowledge regarding hand hygiene frequency and the proper sequence for doffing PPE. DHCP were familiar with practicing hand hygiene prior to doffing PPE but were less familiar with performing hand hygiene between individual doffing steps. One DHCP said, “It [hand hygiene] makes sense in between when you take the gown off that you use hand sanitizer. I usually do that, but then I see that they, between taking the mask off, they washed or hand sanitizer again. I thought that was interesting.”

After reviewing the video, some participants identified where they might have deviated from protocol in the initial donning and doffing assessment. Reference Reske, Park and Bach12 One DHCP stated, “I typically don’t roll my gown [when doffing], and that’s actually where I picked up some fluorescence on my hand when I was taking off my gown.”

Domain 3: Relevance to Clinical Practice. When prompted about relevance to clinical practice, certain PPE items were identified as not applicable, most notably disposable gowns. One DHCP said, “The main difference is that we’re using reusable or washable gowns, like a lab coat. As far as everything else, taking on and off, it’s [video] pretty consistent.”

Among the 58 DHCP who had a positive reaction to the video, 18 (31%) also mentioned that the video would be useful during onboarding for new employees and/or as a part of annual training. One DHCP said, “It’s just helpful to get everyone on the same page… I think having a video that walks us all through doing the same thing would be helpful.”

Domain 4: Additional information that would be helpful. When prompted about video improvements, 16 (30%) of 53 DHCP expressed need for additional guidance. One DHCP stated, “The only thing I would like to see in the video is the N95 for if you were to double mask for a certain reason, what the protocol would be for that… Should I take off the top one and then hand sanitize and then take off the lower one? Or should I take them both off at the same time or something like that?”

DHCP suggested more information is needed on how to don/doff specialty equipment safely. One DHCP said, “I guess one critique… is implementing specialized dental equipment… I know there’s no CDC recommendation for loupes and stuff like that. I think that would be very helpful…”

Discussion

This real-world study captured dental challenges and concerns throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, including before and after vaccines became available. DHCP expressed significant challenges with PPE regarding supply and usage; this is consistent with the findings of Tabah et al, Reference Tabah, Ramanan and Laupland16 who noted that DHCP experienced PPE shortages and needed to reuse single-use PPE items. As a result, DHCP modified PPE to accommodate their needs. DHCP and clinics included in this study adapted to COVID-19 with resourceful solutions; however, the impact of these changes on PPE effectiveness and durability are unknown.

DHCP commonly faced challenges related to respirator use and reuse. Methods for extended N95 use (ie, wearing the same respirator for multiple patient encounters) may reduce effectiveness of PPE. 2,17 CDC guidance states that extended N95 respirator use is not ideal for conventional everyday practice, but it can be done in cases of expected and known shortages. 17 In response to limited supply of N95s, DHCP adopted methods for extended use, including cleaning and double masking or wearing a surgical mask over an N95 respirator.

In addition, fit testing was not universal among the DHCP in this study. Fit testing is required by OSHA; however, enforcement discretion was applied temporarily during COVID-19. 18,19 In our study, 24 (73%) of 33 DHCP who reported using N95 respirators received fit testing, whereas Tabah et al Reference Tabah, Ramanan and Laupland16 found that half of healthcare personnel had never undergone fit testing. Data regarding fit testing were not captured for 26 (44%) of 59 DHCP who wore N95s, suggesting that fit-testing rates may be similar to those of healthcare personnel. All 9 DHCP who were not fit tested were associated with community-setting clinics. Limited access to fit testing is a barrier to proper PPE use among community-based DHCPs. KN95s were not commonly mentioned, but DHCP sometimes used the term KN95 interchangeably with N95. This finding may be linked to limited prior N95 respirator fit testing experience because these tests are often accompanied by education of users on respirator specifications.

PPE effectiveness is complicated further by use of specialty equipment. Additional guidance is needed on how to properly don and doff specialty dental equipment and how to disinfect them between uses. Protective eyewear presented a physical barrier to the use of loupes and microscopes. Similar challenges have been reported in the field of ophthalmology. Reference Ashour, Elkitkat and Gabr20 These challenges may limit use of specialty equipment or increase self-contamination. Recommendations on alternative protective eyewear compatible with loupes and microscopes are needed. Development of protective eyewear that physically incorporates loupes into the design may also serve useful.

DHCP found the educational video helpful and relevant to clinical practice. Educational videos are an effective training tool for teaching and learning, most notably as a supplement to in-person facilitation or demonstration for clinical based skills. Reference Green, Suresh and Bittar21–Reference Forbes, Oprescu and Downer23 Data suggest that incorporating an instructional video along with independent or observed practice of an instructor may be an effective method to teaching. Reference Shippey, Chen and Chou22,Reference Hurtubise, Martin, Gilliland and Mahaz24 Limited data are available regarding retention after PPE training videos; thus, recurrent training may be necessary as a component of continuing education. Future studies are needed regarding the impact of educational videos on postviewing PPE donning and doffing skills.

This study had several limitations. The sample size was relatively small and limited to 1 geographic region. Findings may not be representative of all DHCP due to sampling methods. Due to the nature of semistructured interviews, not all participants discussed the exact same topics. Furthermore, only 1 method of PPE donning and doffing was demonstrated in the video. Based on participant feedback, the incorporation of multiple CDC-approved methods would be beneficial in the future. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable preliminary data on DHCP needs related to PPE and donning and doffing.

Similar to other healthcare personnel, DHCP faced challenges to applying PPE guidance due to supply shortages, specialty equipment, and variable levels of PPE training. Limited guidance may lead to unsafe or inappropriate PPE use; additional research is needed to improve occupational health and address unique challenges in dental care. Educational videos are an effective learning tool widely used throughout the healthcare field for clinical based skills and can help increase PPE knowledge among DHCP.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2023.6

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This study was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR grant nos. X01 DE 031119, X01 DE030403, and X01 DE 030402). These grants were subawards of National Dental Practice-Based Research Network (grant nos. U19-DE-028717 and U01-DE-028727). This funding source did not have a role in the design of this study and did not have a role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results. REDCap at WUSM is supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (grant no. UL1 TR000448) and the Siteman Comprehensive Cancer Center and NCI Cancer Center (grant no. P30 CA091842). J.H.K. is supported by the National Institute 320 of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant no. 1K23AI137321-01A1). M.J.D. is supported by the National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research (grant no. K23DE029514). S.Y.L. is supported by The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences which is, in part, supported by the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS, CTSA grant no. UL1TR002345).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.