Introduction

This paper is aimed at increasing the understanding of the relationships between social participation and life satisfaction after retirement, considering both the diversity of involvements in social life and the social inequalities among older adults. These embedded issues contribute to the reflection on the concept of active ageing that has become dominant in the last few decades, while social participation – broadly defined as individual involvement in activities implying interaction with others (Levasseur et al., Reference Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin and Raymond2010) – gained prominence in ageing representations and realities (Agahi and Parker, Reference Agahi and Parker2005; Ajrouch et al., Reference Ajrouch, Akiyama, Antonucci, Wahl, Tesch-Romer and Hoff2007; Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008; Einolf, Reference Einolf2009; Broese van Groenou and Deeg, Reference Broese van Groenou and Deeg2010; Baeriswyl, Reference Baeriswyl, Burnay and Hummel2017). In particular, social participation seems closely related to the issues of individual wellbeing – or the fact of ‘feeling good and functioning well’ (Ruggeri et al., Reference Ruggeri, Garcia-Garzon, Maguire, Matz and Huppert2020: 1) – at this lifestage.

Initially, around the mid-20th century in the Western world, the institutionalisation of retirement supported a withdrawal from active life, which was largely considered as a withdrawal from social life. This was the argument of the disengagement theory (Cumming and Henry, Reference Cumming and Henry1961), which posits that the withdrawal of older adults from all spheres of life was inevitable and necessary. The extension of longevity, improvement of health and living conditions, and debates about demographic ageing and its impact on both intergenerational solidarity and the welfare state have progressively contributed to changing expectations (Mendes, Reference Mendes2013). In the last part of the 20th century, ageing representations saw the emergence of a ‘third age’ associated with autonomy, activity and personal achievement, while negative representations of old age were postponed to a ‘fourth age’ (Laslett, Reference Laslett1987). Over this period, the initiators of the influential ‘successful ageing’ model, Rowe and Kahn (Reference Rowe and Kahn1987, Reference Rowe and Kahn1997), gave a central place to activity among the factors allowing older adults to overcome age-related losses associated with ‘normal ageing’. In this context, individual wellbeing emerged as a new political ambition for old age and the capacity to remain active became the condition for this wellbeing (Collinet and Delalandre, Reference Collinet and Delalandre2014). Upon these foundations emerged the concept of ‘active ageing’, promoting older adults’ social participation and appearing as an overall response to new ageing realities (Walker, Reference Walker2002), with a ‘win–win’ gain for both individuals and societies (van Dyk et al., Reference van Dyk, Lessenich, Denninger and Richter2013).

Despite an apparent broad consensus, this concept involves different approaches (Walker, Reference Walker2009; Mendes, Reference Mendes2013; Zaidi and Howse, Reference Zaidi and Howse2017). According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002: 12), active ageing aims for ‘people to realise their potential for physical, social, and mental well-being throughout their life course and participate in society according to their needs, desires and capacities, while providing them with adequate protection, security and care when they require assistance’. If individual wellbeing is central to this WHO perspective, active ageing can likewise be further promoted in terms of savings and gains. For instance, the European Commission (nd) has defined active ageing as ‘helping people stay in charge of their own lives for as long as possible as they age and, where possible, to contribute to the economy and society’. This definition reflects a more reductive and utilitarian vision of social participation.

Critically, different authors have reported prescriptivism under the active ageing concept. By promoting a certain ideal of ageing, active ageing policies empower the individual about this lifestage while legitimising one way of behaving (Moulaert and Biggs, Reference Moulaert and Biggs2013). However, not all older adults, depending on their resources and way of life, are able or want to conform to what is valued by scientific and political discourses (van Dyk et al., Reference van Dyk, Lessenich, Denninger and Richter2013). Thus, although the discourses on active ageing have contributed to promoting a more positive picture of ageing and value of older adults’ social roles, the associated risks of exclusion and marginalisation for those who do not conform should be seriously considered (Zaidi and Howse, Reference Zaidi and Howse2017; Del Barrio et al., Reference Del Barrio, Marsillas, Buffel, Smetcoren and Sancho2018).

More so, this paper contributes to this discussion by examining the links between the older adults’ life satisfaction and their social participation, considering explicitly the diversity of practices and the social inequalities in their access. Life satisfaction refers to the overall assessment by the individual of their quality of life according to their own criteria. Through this measure, we focus on the subjective wellbeing (SWB) of older adults (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985; Oishi et al., Reference Oishi, Diener, Lucas, Snyder, Lopez, Edwards and Marques2018), in other terms the self-reported evaluation of wellbeing. This dimension has become a key element of the assessment of ‘ageing well’ (Collinet and Delalandre, Reference Collinet and Delalandre2014; Jivraj et al., Reference Jivraj, Nazroo, Vanhoutte and Chandola2014). This increasing interest has resulted in various measures of SWB, effectively distinguishing between emotional (or affective) and cognitive (evaluative) dimensions. Life satisfaction belongs to the second category and is described as more stable and less affected by transient moods than the first one (Dolan et al., Reference Dolan, Peasgood and White2008).Footnote 1 Life satisfaction is considered a good indicator of psychological adaptation to the ageing process and successful ageing (Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez, Tomás, Galiana, Sancho and Cebrià2013; Li et al., Reference Li, Xu, Min, Chi and Xie2016). Consequently, it would be appropriate to question the associations between social participation and the individual sense of wellbeing.

Empirically, based on a large survey on the health and living conditions of older adults (aged 65 years and older) in Switzerland, we essentially addressed our questioning in two stages, asking first what participation forms are associated with life satisfaction, and then how belonging to certain social categories shape access to these forms of participation. In the following sections, we deepen the rationale of our research questions through a focused literature review; thereafter we discuss the data and methods. Results indicate the complexity of the association between social participation and life satisfaction. They sustain a discussion about the meaning of having some multiple and various participations, on the one hand, and some specific participations types involving institutionalised ties and/or private sociability forms, on the other hand. Moreover, findings of social inequalities in participation opportunities lead to making a difference between more or less traditional forms of participation, new ones similarly emerging overall as more unequal. We conclude by re-examining social participation diversity and social inequalities linked with the active ageing discourses, underlining the importance of the cohort change and its implications for future generations of older people.

Social participation and life satisfaction: a literature review

Multiplicities and complexities of ties between social activities and SWB

The associations between social participation and several dimensions of health, including SWB and life satisfaction measures, have been repeatedly observed (Bath and Deeg, Reference Bath and Deeg2005; Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008; Morrow-Howell, Reference Morrow-Howell2010; Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Hendricks, O'Neill, Binstock and George2011; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Morrow-Howell, Wilson, Settersten and Angel2011; Dorfman, Reference Dorfman and Wang2013; Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Georgiou and Westbrook2017; Hornby-Turner et al., Reference Hornby-Turner, Peel and Hubbard2017). Their conclusions are however not completely coherent. One reason for this variability refers not only to the various indicators of wellbeing and SWB studied but also the multiple ways of conceptualising and defining social participation (Bath and Deeg, Reference Bath and Deeg2005; Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008; Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Georgiou and Westbrook2017). Studies have considered simultaneously various activities and their links with SWB (Li and Ferraro, Reference Li and Ferraro2005; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Stewart and Dewey2013; Potočnik and Sonnentag, Reference Potočnik and Sonnentag2013; Amagasa et al., Reference Amagasa, Fukushima, Kikuchi, Oka, Takamiya, Odagiri and Inoue2017; Vozikaki et al., Reference Vozikaki, Linardakis, Micheli and Philalithis2017), particularly life satisfaction (Chen, Reference Chen2001; Warr et al., Reference Warr, Butcher and Robertson2004; Joulain et al., Reference Joulain, Martinent, Taliercio, Bailly, Claude and Kamel2019; Ramia and Voicu, Reference Ramia and Voicu2022), and have confirmed that not all the types of social participation show a similar and positive association.

Overall, the mechanisms involved in a positive influence of social participation on older adults’ wellbeing are not clearly established. Raymond et al. (Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008) distinguished three types of explanations. The first advances that social participation allows older adults to keep fit by supporting cognitive and/or physical activity, which influences SWB indirectly (Helliwell and Putnam, Reference Helliwell and Putnam2004). The second considers social participation as an identity resource that contributes to overcoming losses and bereavements associated with ageing by providing recognised social roles (see also Van Willigen, Reference Van Willigen2000; Morrow-Howell et al., Reference Morrow-Howell, Hinterlong, Rozario and Tang2003; Li and Ferraro, Reference Li and Ferraro2005; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Burr, Mutchler and Caro2007). The last type of explanation focuses on social relations benefits in the ageing process: the contacts and significant mutual exchanges in social participation are described as ways to find goals and consequently to maintain meaning in life.

These mechanisms are not exclusive and can be more or less present depending on the specific activity being performed. For instance, formal public participation, such as being active in associations or formal volunteer work, seems particularly meaningful to occupy a recognised social role (Li and Ferraro, Reference Li and Ferraro2005; Morrow-Howell, Reference Morrow-Howell2010), and thus contribute to individuals’ sense of wellbeing. Various empirical studies have confirmed its association with older adults’ SWB (Morrow-Howell et al., Reference Morrow-Howell, Hinterlong, Rozario and Tang2003; Greenfield and Marks, Reference Greenfield and Marks2004; Potočnik and Sonnentag, Reference Potočnik and Sonnentag2013; Barbabella et al., Reference Barbabella, Poli and Kostakis2019), and specifically with their satisfaction of life (Van Willigen, Reference Van Willigen2000; Helliwell and Putnam, Reference Helliwell and Putnam2004; Lee and Choi, Reference Lee and Choi2020; Ramia and Voicu, Reference Ramia and Voicu2022). Among social relations, some contexts appear more relevant for wellbeing; in the last decades, marked by a growing prevalence of social norms promoting individuality against institutions (Giddens, Reference Giddens1991), friendships ties emerged as particularly meaningful in terms of SWB and life satisfaction because they are independent of constraint and obligation when compared with family ties (Krause, Reference Krause2010; Carr and Moorman, Reference Carr, Moorman, Settersten and Angel2011; Huxhold et al., Reference Huxhold, Miche and Schüz2014). Consequently, friendly relationships tend to last only as long as they are perceived as positive (Allan, Reference Allan2008). In contrast, studies on care-giving have shown that family roles could even be detrimental for SWB (concerning particularly life satisfaction, see Ramia and Voicu, Reference Ramia and Voicu2022). Involvements in other social activities may be important by providing a network of meaningful relationships: this is especially the case with religious participation, which supports values and specific individual behaviours contributing to SWB (Ellison, Reference Ellison1991; Lim and Putnam, Reference Lim and Putnam2010) and specifically to life satisfaction (Ellison et al., Reference Ellison, Boardman, Williams and Jackson2001; Warr et al., Reference Warr, Butcher and Robertson2004). Besides, involvement in multiple roles could be particularly beneficial for individual wellbeing by increasing an ‘individual's social network, power, prestige, resources, and emotional gratifications’ (Moen et al., Reference Moen, Dempster-McClain and Williams1992: 1634; see also Baker et al., Reference Baker, Cahalin, Gerst and Burr2005; Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Georgiou and Westbrook2017). Furthermore, studies have confirmed a higher level of life satisfaction for individuals accumulating several activities (Warr et al., Reference Warr, Butcher and Robertson2004; Gilmour, Reference Gilmour2012).

This diversity of results and potential mechanisms underlines the complexity of the links between social participation and SWB, including life satisfaction, significantly with the many realities behind the concept of ‘social participation’.

Definitions of social participation: multiple boundaries and issues

Studies on the concept of social participation have confirmed the lack of a clear universally accepted definition of the term (Larivière, Reference Larivière2008; Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008; Levasseur et al., Reference Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin and Raymond2010). Social participation refers broadly to individual involvement in activities that entail interaction with others (Levasseur et al., Reference Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin and Raymond2010), however, various focuses co-exist in specific studies. Levasseur et al. (Reference Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin and Raymond2010) distinguished six levels of social participation dependent on the proximity with others (alone, in parallel, in interaction) and aims of the activity (basic need, socialisation, task completion, the support provided to others or the society). Accordingly, Raymond et al. (Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008) distinguished four sets of definitions that refer to the dynamics of the relationships between individuals and their environment. In the broadest sense, social participation is defined as daily functioning, while in the most restrictive sense, it is defined as structured associativity (or formal public participation). Between these two extremes, the researchers also distinguished social participation as social interactions (or social connectivity) and social networks (personalised social interactions referring to social capital and informal volunteering).

Ultimately, these studies underline the multi-dimensional aspect of social participation. In gerontology, a majority of studies have examined structured associativity (Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008) or in a slightly broader perspective, social commitment (Levasseur et al., Reference Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin and Raymond2010). Thus, we can draw a parallel with issues that are central to the definition of active ageing content: clearly, the most restrictive definition – formal public participation – is the most popular in political discourses (Walker, Reference Walker2009; Moulaert and Biggs, Reference Moulaert and Biggs2013; Del Barrio et al., Reference Del Barrio, Marsillas, Buffel, Smetcoren and Sancho2018). This perspective refers to a ‘productive’ model of ageing or, more broadly put considering alongside informal commitment, to a ‘solidary’ model of ageing (Backes and Amrhein, Reference Backes, Amrhein, Künemund and Schroeter2008). Both models primarily support the ‘useful’ character of older adults’ activities. However, several studies have shown the importance of more informal and/or private activities in terms of both older adults’ practices (Suanet et al., Reference Suanet, van Tilburg and Broese van Groenou2013; Baeriswyl, Reference Baeriswyl, Burnay and Hummel2017) and their SWB outcomes (Bickel and Girardin Keciour, Reference Bickel, Girardin Keciour, Guilley and Lalive D'Epinay2008), including life satisfaction (Chen, Reference Chen2001; Gutiérrez et al., Reference Gutiérrez, Tomás, Galiana, Sancho and Cebrià2013; Huxhold et al., Reference Huxhold, Miche and Schüz2014; Yuan, Reference Yuan2016; Ramia and Voicu, Reference Ramia and Voicu2022). Thus, these forms of participation should equally be considered as important investments at retirement time in the individual wellbeing perspective.

On a more theoretical level, the study of two sets of distinctions – between private and public spheres, and between formal and informal participation – revealed ambivalent issues about the meanings attached to various investments in terms of empowerment versus confinement/domination. First, the private/public distinction, which is crucial in the study of gender relations and inequalities, can generally be seen as a continuum,Footnote 2 combining two criteria where the private is opposed to the visible and collective character of the public (Weintraub, Reference Weintraub, Weintraub and Kumar1997). The public dimension of investments emerges thus as a privileged place for social recognition and is often conceived in that perspective as crucial for self-realisation (see the section above on SWB). However, conversely, the private does not refer only to simple negative withdrawal but should be thought of as emancipatory and ‘satisfactory’ through its more individual aspects (as opposed to public constraints or public desingularisation) (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1990). For retired people, more private investments may particularly mean work liberation and time for themselves.

The second level of distinction refers to structural dimensions of participation. Several authors have distinguished particular relational structures, the social circles, from social networks or relationships (Grossetti, Reference Grossetti2005; Bidart et al., Reference Bidart, Degenne and Grossetti2011). Social circles involve institutionalised forms of social ties in which individual position and status are defined, borders are clear and stable, and forms of collective identification are shared. This distinction refers to more or less formal forms of participation indirectly mentioned above as ‘structured associativity’, and family or religious participation too. For the individual, social circles represent both resources and constraints (Bidart et al., Reference Bidart, Degenne and Grossetti2011) and involve mixed issues regarding SWB, particularly in the context of late modern societies where individuality is promoted against the institutions (Giddens, Reference Giddens1991). This is well expressed through the concept of ambivalence in intergenerational relationships that spotlights the adverse feelings that can arise from the co-existence within family dynamics of norms and practices of solidarity and interdependency, on the one hand, and autonomy and independence, on the other hand (Lüscher and Pillemer, Reference Lüscher and Pillemer1998).

An inclusive and plural approach of social participation

At this stage, we conclude that adopting a more inclusive definition of social participation while considering its multi-dimensional character and various contents is important to understand better its relations to life satisfaction. In this framework, we propose to understand social participation as any activity undertaken voluntarily by an individual that includes a relation with other persons. Given the background on various social participation opportunities, we can distinguish formal public participation forms that constitute the most restrictive definition of social participation in the literature (Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008) and refer to the civic dimension of the ‘public’ definition as a means of intervention in collective life (Weintraub, Reference Weintraub, Weintraub and Kumar1997), embodying both characteristics related to this sphere – that is visible and collective. Additionally, it implies mainly the integration to specific circles, notably associative.

Besides, we can distinguish more informal participation in the public sphere similarly studied in the literature in terms of social leisure, that is not aimed towards the ‘collective’ but refers to some impersonal sociability (Weintraub, Reference Weintraub, Weintraub and Kumar1997) or socialisation in parallel (Levasseur et al., Reference Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin and Raymond2010). This dimension of social participation involves more exclusively expressive practices compared to formal public participation. In particular, cultural activities can be seen as typical of contemporary society based on consumption and personal achievement (Bickel et al., Reference Bickel, Lalive d'Epinay and Vollenwyder2005). Other activities – typically going to the café – represent a more communitarian and traditional aspect of these forms of social participation.

Other social participation forms refer more directly to the private as the sphere of intimate and interpersonal relationships (Weintraub, Reference Weintraub, Weintraub and Kumar1997). Both ‘invisible’ and ‘individual’, private sociability refers to expressive activities involving personal relationships and represents the counterpart of social leisure in private space, often studied in terms of a personal network. This more invisible aspect of social participation has a collective aspect through support practices that are studied as ‘informal volunteering’. These forms of social participation represent the less visible, and less recognised, side of social commitment, in comparison with the formal public dimension (Pennec, Reference Pennec2004). In addition, considering the structural aspects of participation, the distinction between activities involving family or non-kin (typically friends) ties refer to the more or less institutionalised dimensions of private participation.

Finally, religious social participation (typically office attendance) occupies a special position: it takes place outside the home and the intimate sphere, which, however, refers neither to civic engagement nor to impersonal sociability. It refers to the inclusion in a specific circle involving a community based on shared beliefs and values. It provides specific opportunities for meaningful exchange, social support and recognition (Baumann, Reference Baumann, Pahud de Mortanges, Bochinger and Baumann2012).

Beyond the distinction of various forms of investments in social ties, the accumulation of individual investments is another interesting point to consider regarding life satisfaction. The possibility to combine many different forms of social integration is, as Simmel (Reference Simmel2009) stressed, a central element in the modernity process as a major motor of individualisation. Combining multiple forms of social participation should thus be important for self-realisation and SWB.

Individualisation and unequal individuals

As previously stated, social participation issues related to SWB and life satisfaction can vary depending on the adopted definition of social participation. Further, from the perspective of more critical gerontology (Baars et al., Reference Baars, Dannefer, Phillipson, Walker, Baars, Phillipson and Dannefer2005), it is important to consider the heterogeneity of the older adult population (Oris et al., Reference Oris, Guichard, Nicolet, Gabriel, Tholomier, Monnot, Fagot, Joye, Oris, Roberts, Joye and Ernst-Stähli2016) and the social inequalities that impact life conditions after retirement (Oris et al., Reference Oris, Gabriel, Ritschard and Kliegel2017). The process of individualisation – in which social and cultural changes occurred in post-war Western societies have notably established self-realisation as a lifecourse ideal (Honneth, Reference Honneth2004) – , is sometimes described as involving a decline in logics of inequalities (e.g. Beck and Willms, Reference Beck and Willms2004, on the idea of classes’ erasure). Rather, empirical studies have emphasised the persistence of inequalities (e.g. Blossfeld et al., Reference Blossfeld, Blossfeld and Blossfeld2015, on the impact of social origin on educational attainment; or Krüger and Levy, Reference Krüger and Levy2001, regarding gendered lifecourses), particularly in old age, where a cumulative process may even increase social inequalities (Dannefer, Reference Dannefer2020).

Studies have underlined social participation as conditioned by a set of social determinants that include gender, age or socio-economic status (Morrow-Howell, Reference Morrow-Howell2010; Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Hendricks, O'Neill, Binstock and George2011; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Morrow-Howell, Wilson, Settersten and Angel2011; Dorfman, Reference Dorfman and Wang2013). Furthermore, previous research comparing various forms of participation has shown that such determinants and their impact may vary depending on the type of activity (Wilson and Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997; Agahi and Parker, Reference Agahi and Parker2005; Bickel and Cavalli, Reference Bickel, Cavalli, Lalive D'Epinay and Spini2008; Broese van Groenou and Deeg, Reference Broese van Groenou and Deeg2010; Baeriswyl, Reference Baeriswyl, Burnay and Hummel2017, Reference Baeriswyl2018). For instance, access to public formal activities, such as volunteering or membership of associations that are socially valued forms of social participation, seems more socially stratified or, simply put, more unequal. Thus, the inclusive and multi-dimensional approach adopted in this paper is pertinent regarding the issues of social inequalities.

Methods

Data

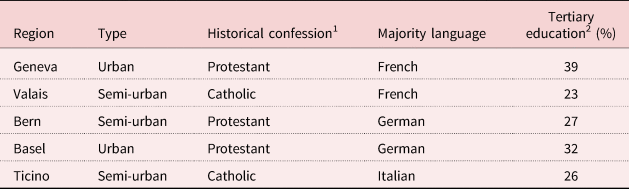

The empirical analyses are based on data from the survey ‘Vivre-Leben-Vivere: Old Age Democratization? Progresses and Inequalities in Switzerland’ (VLV). This large interdisciplinary survey on living and health conditions of people aged 65 and older was conducted in 2011/2012 in five Swiss cantons (Geneva, Valais, Bern, Basel and Ticino). These regions are representative of the country's diversity on territorial, lingual and political levels (for more details on the characteristics of these regions, see Table 1; for more details on the VLV survey, see Ludwig et al., Reference Ludwig, Cavalli and Oris2014). The VLV data have already been exploited in more than 80 publications.Footnote 3

Table 1. Surveyed regions’ main characteristics

Notes: 1. Majority confession may differ from historical one. However, historical confessions always influence the institutional and cultural frameworks of each region (Monnot, Reference Monnot2013). 2. Proportion of people with tertiary education among the resident population aged 25 years and older in 2012 (Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS), nd).

Source: Table taken from Duvoisin (Reference Duvoisin2020: 47, own translation) and completed with data derived from the OFS.

The sample was randomly selected from regional population registers and was stratified by gender and age group (65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89 and 90 years and older). In this context, all the following analyses use a computed weighting coefficient to restore the real population structure (StataCorp, 2011). Data were collected through two standardised questionnaires, one auto-administered and one filled in during a face-to-face interview. Overall, 3,080 individuals answered personally (for a complete assessment of the VLV survey, see Oris et al., Reference Oris, Guichard, Nicolet, Gabriel, Tholomier, Monnot, Fagot, Joye, Oris, Roberts, Joye and Ernst-Stähli2016). Among those, we excluded from the working sample 353 who did not respond to all the items of the Diener life satisfaction scale, leaving us with 2,727 older adults.

Variables

Life satisfaction

We analysed the life satisfaction of older adults using the Satisfaction with Life Scale developed by Diener et al. (Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985). This scale is composed of five items through which an individual is asked to evaluate life satisfaction based on his or her own criteria:

(1) In most ways my life is close to my ideal.

(2) The conditions of my life are excellent.

(3) I am satisfied with my life.

(4) So far I have gotten the important things I want in life.

(5) If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.

Participants had to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with each item using a seven-point scale, with seven meaning ‘strongly agree’ and one ‘strongly disagree’. The answers were added to an individual score.

Analysis of Cronbach's alpha (0.85) and principal component analysis (the first axe explaining 64% of the variance) confirmed the overall consistency of individual answers. A mean satisfaction with life value of 26.8 and standard deviation of 5.4 showed VLV results close to those found for older adults in other studies (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Vallerand, Pelletier and Brière1989; Pavot and Diener, Reference Pavot and Diener1993, Reference Pavot, Diener and Diener2009).

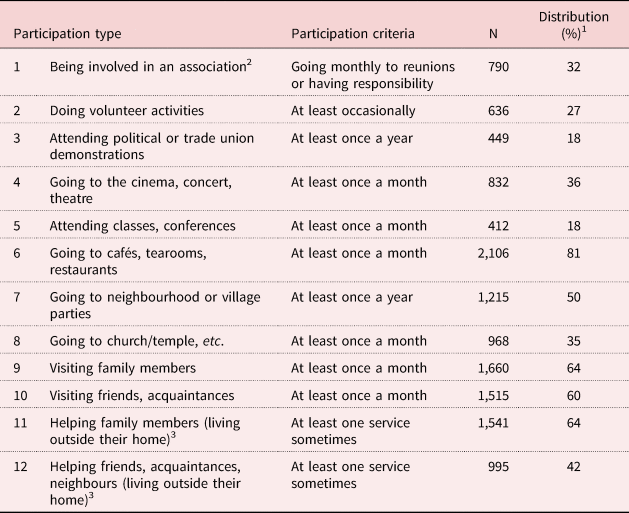

Participation variables

In coherence with the previous theoretical discussion, we constructed 12 binary indicators of social participation. Original variables consisted of different frequency scales. We dichotomised them to render information on access to the activities in question. More specifically, we set bounds that assumed a minimal regularity, that is, their practice was not exceptional, and, however, a high frequency was not necessarily required. Often, the frequency chosen was monthly; however, it depended on the nature of the activity and the original variable response modalities (Table 2).

Table 2. Social participation variables and distribution among the survey population

Notes: 1. Weighted data. 2. This variable is based on three questions: a list of types of associations to which individuals can be member, the frequency of participation to associations meeting and the fact of having responsibility in associations. 3. This variable is based on a list of ten types of service that individuals can provide: cleaning, preparing/bringing meals, shopping, providing child care/helping with homework, doing home repairs/tinkering/gardening, taking children on outings, taking old or disabled persons on outings, helping with professional work, helping with grooming, helping with administrative tasks.

The first three indicators (being involved in associations, doing volunteer activities, and attending political or trade union demonstrations; 1–3 in Table 2) are forms of social commitment in the public sphere. They refer mainly to civic participation and the most restrictive definition of social participation as formal public participation. The next four indicators (4–7) are more individual forms of participation in the public sphere, referring to more informal and unilaterally expressive social activities involving a certain integration in society. Primarily, going to the cinema/concert/theatre and attending classes/conferences represent activities more typical of contemporary culture; the two other indicators – going to neighbourhood or village parties and going to cafés/tearooms/restaurants – represent a more communitarian and traditional form of social participation. Another form of participation that can be considered traditional in the European context is the church/temple, etc. attendance (8). As noted above, it represents a specific form of participation in the public sphere, neither ‘collective’ nor ‘impersonal’, and refers to a particular social circle. The last four indicators (9–12) refer to forms of participation in the private sphere of intimacy and interpersonal relationships: they are differentiated by whether they take place within the family circle or in non-kin networks and whether they imply the collective dimension of social commitment (helping) or not (visiting), referring in the last case to more exclusively expressive practices of sociability. Additionally, we constructed a score representing the sum of the 12 binary indicators to document the individual accumulation of practices.

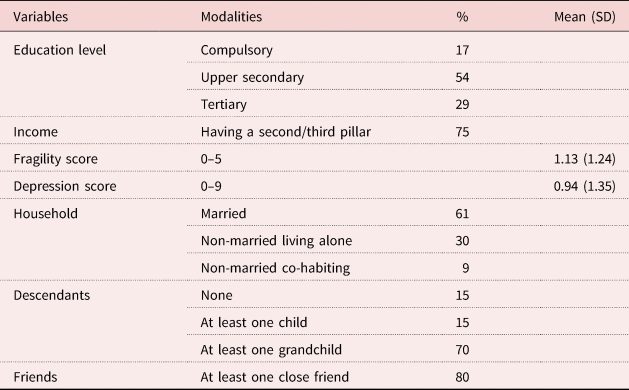

Control variables

The various control variables introduced in the analyses of the links between social participation and life satisfaction refer first to the three socio-demographic variables that were used to stratify the VLV sample: sex, age group and region. A second group includes other individual characteristics that constitute, as previous research has shown, resources for both life satisfaction (Pinquart and Sörensen, Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2000; Dolan et al., Reference Dolan, Peasgood and White2008; George, Reference George2010) and social participation (Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008; Morrow-Howell, Reference Morrow-Howell2010; Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Hendricks, O'Neill, Binstock and George2011; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Morrow-Howell, Wilson, Settersten and Angel2011; Dorfman, Reference Dorfman and Wang2013). Education level (compulsory, upper secondary, tertiary) and access to more than basic old-age pension (yes/no)Footnote 4 refer to the individual socio-economic position in the structures of the retired population; frailty score (Guilley et al., Reference Guilley, Ghisletta, Armi, Berchtold, Lalive d'Epinay, Michel and de Ribaupierre2008) and depression score (adapted from Wang et al., Reference Wang, Karp, Winblad and Fratiglioni2002; see also Lalive d'Epinay et al., Reference Lalive d'Epinay, Bickel, Maystre and Vollenwyder2000) refer to health capacities, both physical and psychological; household composition (married, not married and living alone, not married but co-habiting); presence of descendants (none, having at least one living child, having child(ren) and at least one grandchild) and presence of close friend(s) (yes/no) in the individual network refer to social capital (Table 3).

Table 3. Surveyed population characteristics

Notes: Weighted data. SD: standard deviation.

Indicators of social inequalities

Among the presented control variables, the three socio-demographic characteristics (sex, age group and region) are used as independent variables in the second set of analyses that examine social inequalities in participation opportunities. Subsequently, we selected the education level that constitutes a good and reliable proxy of socio-economic status in old age (Oris et al., Reference Oris, Gabriel, Ritschard and Kliegel2017).

Analyses

We ran two sets of linear regression models on the score of life satisfaction. In the first one, the 12 binary indicators of social participation were tested, and in the second, the score resulting from the sum of those 12 indicators. For both analyses, we ran two nested models: in the first model, the three socio-demographic variables of sample stratification (age, sex and region) and the participation indicators (activities or score) were included. In the second model, we added all the other control variables (‘resources variables’) presented above to isolate the association between social participation and life satisfaction from a broader resources system (that can influence both participation and life satisfaction).

Thereafter, we ran a series of regression analyses on the indicators of social participation revealed to be significantly linked with life satisfaction to address the issue of social inequalities. Specifically, we ran logistic regressions on the binary participation indicators and Poisson regression on the score of participation.

Results

Social participation distribution

Overall, the mean value of the social participation score is 5.22 out of a maximum of 12, and its standard deviation is 2.42. Regarding the distribution of the various practices of social participation among our study population (Table 2), sociability practices in public (going to café or local event) and private (visiting family or friends) spheres are the most common, concerning a majority of the older adults. The other expressive practices, i.e. cultural leisure, are less frequent and engage only a minority of the people of retirement age. Among the forms of commitment towards others, a majority of older adults offer occasional help to family members living outside the home. Social commitment in the public sphere is rarer than in the private sphere: about one-third of older adults declare being involved in associations, while fewer do volunteer activities and even fewer take part in political or trade union demonstrations. Finally, religious participation concerned about one-third of older people.

The links between social participation and life satisfaction

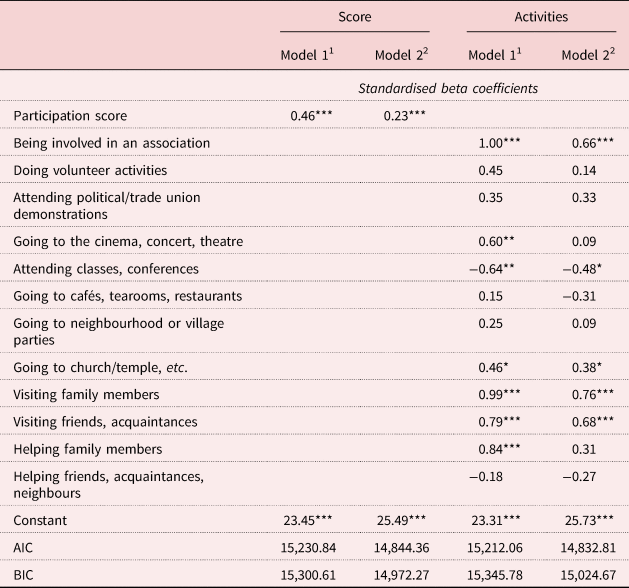

The general importance of participation for life satisfaction is confirmed when we consider its links with the score of participation: multi-activity and life satisfaction are positively associated (Table 4, ‘Score’ column). Although the coefficient is reduced in Model 2, showing that part of the link between the life satisfaction and social participation score can be explained by other individual resources, a significant link remains.

Table 4. Multiple linear regression analyses on the Satisfaction with Life Scale – the links with social participation

Notes: N = 2,475. Weighted data. 1. Control variables: gender, age group and region. 2. Control variables: gender, age group, region, education level, income source, fragility score, depression score, household composition, descendants, close friend existence. AIC: Akaike information criterion. BIC: Bayesian information criterion.

Significance levels: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

The analyses of life satisfaction related to the different types of participation show more or less significant results (Table 4, ‘Activities’ column). Namely four types remain significant and positively linked to this measure of cognitive SWB after controlling for the aforementioned various resources (Model 2): being involved in an association, visiting family, visiting friends/acquaintances and going to church/temple, etc. Attending shows (cinema, concert, theatre) and helping family members have a significant positive association with life satisfaction in Model 1. However, this association disappears when controlled for the various resources of older adults. An unexpected result concerns attending courses or conferences: this type of activity has a significant negative association with life satisfaction.

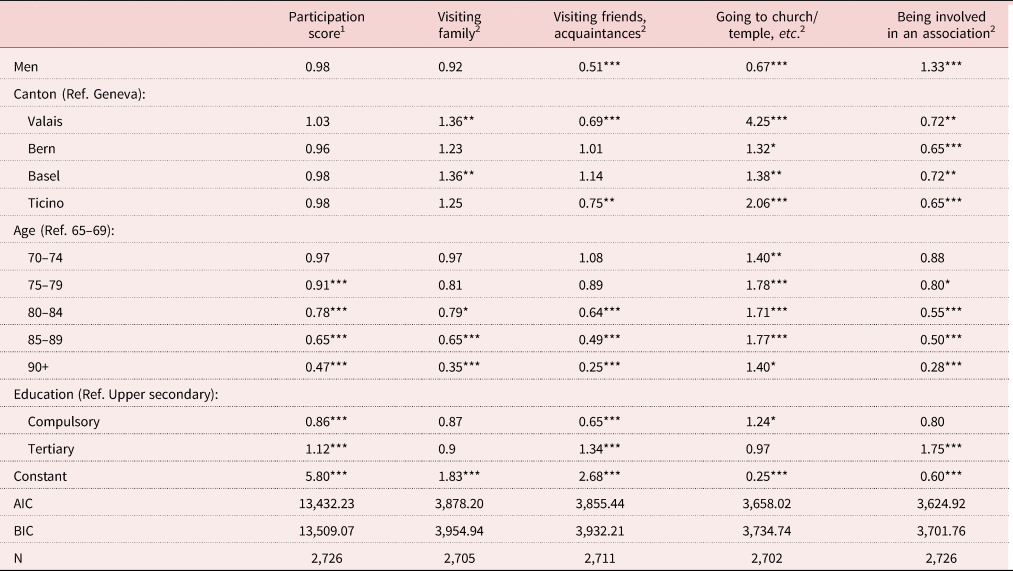

Social inequalities in social participation

Table 5 shows significant results concerning social participation and life satisfaction when considering unequal chances to participate according to gender, region, age and level of education. The overall score is not differentiated between men and women; however, the types of participation refer to gender differences. Men are more likely to invest in associations; women are more likely to visit friends or acquaintances and to go to church/temple, etc. Family sociability, however, is not impacted by gender.

Table 5. Multiple regression analyses on participation indicators – the impact of socio-demographic and socio-economic positions

Notes: Weighted data. 1. Poisson regression (incidence-rate ratio). 2. Logistic regression (odds ratio). Ref.: reference category. AIC: Akaike information criterion. BIC: Bayesian information criterion.

Significance levels: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

In terms of region, we also found specificities in participation types. People living in the canton of Geneva – which is typical of an urban, laic and socio-economically advanced regional context – are significantly more likely to have associative involvement and are less likely to have religious or family participation. They are also significantly more likely to visit friends or acquaintances than people living in the Catholic and less socio-economically developed regions of Valais and Ticino.

The effect of age on participation likelihood is markedly negative (as shown by the score results). However, in contrast with this general trend, going to church/temple, etc. is positively associated with older age groups. This result underlines a cohort effect. The comparison of this practice in 2011 with comparable data from 1979 clearly showed its decline across the birth cohorts (Baeriswyl, Reference Baeriswyl, Burnay and Hummel2017).

Taking into perspective the educational level impact, the overall advantage of an elite group emerges. Possessing a tertiary diploma increases the likelihood of participating in a wide variety of activities. More specifically, having a high education has a positive effect on the probability of being involved in an association, and having an average education level, and much more a high level increases the likelihood of visiting friends or acquaintances. However, family sociability is not impacted by this individual socio-economic position and having a low level of education tends even to increase church attendance.

Discussion

The links between social participation and life satisfaction in old age are confirmed by the Swiss data while highlighting some specific aspects of the various social activities of the older adults as well as important issues related to social inequalities in participation likelihood. In this final section, after the first point on the main results linking activities to life satisfaction, we discuss in particular two characteristics shared by the types of social participation that are positively linked to life satisfaction. Then, we reconsider these results from the perspective of the social inequalities involved in access to participation opportunities. After an acknowledgement of the limits of our analyses, we conclude by re-examining the implications of the various definitions of social participation and the dominant active ageing discourses. Future challenges and questions about social participation and life satisfaction will be finally addressed.

Social participations and life satisfaction

First, our results confirmed the association between having a rich and varied social participation and higher life satisfaction. This pattern observed in Switzerland is consistent with previous studies examining various dimensions of SWB (see the literature review section). Generally, it supports theories underlining the significance of multiple and intersected belongings for individuals’ identity building and personal achievement, namely allowing greater individuality (Simmel, Reference Simmel2009). Second, analyses similarly highlighted four types of social participation that are especially meaningful for life satisfaction: involvement in associations, attendance of religious celebrations, visits to family and visits to friends/acquaintances. For most of those results, our results align with previous studies from other countries (mainly from the Western world and Asia as well). As stated earlier in the literature review section, the positive association with civic commitment, religious participation or friendship are well documented in the literature on life satisfaction of older people (see also Dolan et al., Reference Dolan, Peasgood and White2008; George, Reference George2010).

Our findings about family are, however, less obvious. Studies have shown some negative impacts of family investment on older adults’ SWB (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Stewart and Dewey2013; Huxhold et al., Reference Huxhold, Miche and Schüz2014; Ramia and Voicu, Reference Ramia and Voicu2022). Overall, family ties involve more constraints (both as constrained and constraining) and seem more ambivalent than non-kin relationships regarding SWB issues: they can be simultaneously not just an important source of support but also a source of tension by reducing the autonomy of older individuals (Lüscher and Pillemer, Reference Lüscher and Pillemer1998; Baeriswyl et al., Reference Baeriswyl, Girardin and Oris2022). However, our results establish a positive association between visiting family members and life satisfaction that underlines the emancipatory dimension of the family (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1990). Caution is, however, needed since our variable concerns only one type of sociability practice, which represents a relatively voluntary form of contact, and focuses on family members living outside the household.

Finally, a more unexpected result concerns the negative association between life satisfaction and activity in courses or conferences. In Switzerland, like elsewhere, there is a growing offer of such activity, as part of the institutional promotion of life-long learning, seen as sustaining the productive capacities of the older adults as well as their general wellbeing (Campiche and Kuzeawu, Reference Campiche and Kuzeawu2014; Formosa, Reference Formosa and Formosa2019). More so, studies tend to confirm the positive impact of life-long learning on SWB (Narushima et al., Reference Narushima, Liu and Diestelkamp2018). Critical voices, however, assert the absence of reliable statistics on the participation, the gap between the participants’ expectations and offers sometimes qualified as elitist and ‘mindless’ together, and older adults being taken as passive recipients (Formosa, Reference Formosa2011, Reference Formosa2012). Another hypothesis to explain our result is that people who have less SWB, specifically life satisfaction, seek solutions through this type of learning activity. However, further investigation is needed, especially taking into consideration the types and content of learning activities. However, this result is the most explicit illustration of the various and complex links existing between social participation and life satisfaction.

Collectively, our results highlight two more general important characteristics of social participation positively associated with satisfaction of life. On one side, they emphasise the significance of participation embedded in formal/institutionalised social ties. Participation in associations, family or religion refers to structured forms of social ties, to ‘social circles’ in which individual position and status are defined and borders are clear and stable (Bidart et al., Reference Bidart, Degenne and Grossetti2011). In the literature review section, and the image of family dynamics mentioned above, we noted the ambivalent meaning that participation in social circles can have between resources and constraints. However, in our results the association with life satisfaction is positive. An explanation lies in the social identity theory which suggests that integrations in such circles offer a feeling of belonging, with strong meaning that would contribute to a greater sense of wellbeing (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, Jetten, Postmes and Haslam2009). Participation in such social structures can also be regarded as playing a role of ‘facilitator’ for other types of relationships and participation (Bidart et al., Reference Bidart, Degenne and Grossetti2011) and would constitute central investments in older adults’ lives. At the crossroads of these two functions, when considering the association of religious participation and life satisfaction, Lim and Putnam (Reference Lim and Putnam2010: 929) showed thus the role of both the network built through religious attendance and the identity shared: ‘the social contexts in which networks are forged and the identities shared in these networks matter’. This interpretation can be applied to other social circles.

On the other side, the results about private sociability in the family circle and with friends or acquaintances point out the significance of very private forms of social participation related to life satisfaction. This highlights the meaning of expressive, personal and intimate relationships after retirement (in this sense, see also the results of Warr et al., Reference Warr, Butcher and Robertson2004). Furthermore, it refers to the issue of the quality of social ties involved in participation: having significant and reciprocal exchanges would support the perception of social support, self-esteem and positive affects (Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Gagné, Sévigny and Tourigny2008), which would also influence positively life satisfaction.

Social inequalities of participation in a late-modern society

As we suspected, analysing the social determinants of social participation supports a critical perspective on previous findings by underlining social inequalities. Having multiple and diversified forms of social participation is associated with higher life satisfaction; however, the so-called ‘young old’ and individuals with high education are more likely to benefit from such participation profiles. Likewise, the chances of being engaged in an association or of visiting friends/acquaintances follow the same logic. These forms of social participation all refer to roles and relationships that are particularly valued in late modernity societies. First, hyperactive seniors represent the ideal type of ‘new’ older adults – matching both with the multi-activity characterising contemporary lifestyles (Cingolani, Reference Cingolani2012) and with the attribution of individual responsibility to age ‘successfully’ (and actively) (Rowe and Kahn, Reference Rowe and Kahn1997). In the perspective of the new models of ageing, involvement in the public sphere embodies particularly the ‘productive’ view on active ageing, often privileged in political discourse (Walker, Reference Walker2009; Moulaert and Biggs, Reference Moulaert and Biggs2013; Del Barrio et al., Reference Del Barrio, Marsillas, Buffel, Smetcoren and Sancho2018), and responds to the injunction for older adults to not be a ‘social burden’. Finally, the development of elective social and flexible ties, referring expressly to personal relationships outside the family, is also part of individualisation processes in late modern societiesFootnote 5 (Stevens and Van Tilburg, Reference Stevens and Van Tilburg2011; Suanet et al., Reference Suanet, van Tilburg and Broese van Groenou2013).

In contrast, family and religious participation – that may be regarded as traditional modes of participation and integration – emerge as important practices for groups considered more vulnerable, that is they have greater exposure to risks and stresses because they tend to have fewer resources, for instance in terms of health and revenues (Oris, Reference Oris2017). This is notably the case for the less-educated older adults and older women (Oris et al., Reference Oris, Gabriel, Ritschard and Kliegel2017; Baeriswyl, Reference Baeriswyl2018). Visiting family members appears as ‘democratic’ social participation as it is not impacted by the level of education. Being involved in a religious circle is the only type of social participation that tends to be more frequent for those with a low education level. In addition, women are more likely to engage in religious participation.

Opportunities to participate are not equally distributed among men and women, trends showing a traditional division of gender roles. In particular, we found the traditional gendered opposition between the public and the private: women remain overrepresented in the private sphere of intimacy and interpersonal relationships by their higher trend of visiting friends and are relatively less present than men in public spaces through a lower associative involvement. Beyond the SWB issue, this observation has consequences for power relationships between genders as women have less access to spaces where collective interests can be defended (Baeriswyl, Reference Baeriswyl2018). Furthermore, the trend of religious participation – women are more likely to attend religious celebrations – refers also to gendered role construction, particularly in this generation (Campiche, Reference Campiche1996). Noteworthy, gender inequalities are transversal with those related to socio-economic status and the distinction between modern versus traditional participation. We will revisit the implications of the various patterns of social inequalities at the end of this paper.

Limitations

Before discussing the complexity in conclusion, some limitations of this study were acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the VLV data does not enable a causal relationship between social participation and life satisfaction and the direction of their association to be established. A second limiting factor is the indicators used in this study. We examined social participation in terms of access to some practices. However, the intensity of practice would as well impact wellbeing (Morrow-Howell et al., Reference Morrow-Howell, Hinterlong, Rozario and Tang2003). This dimension requires further investigation. Similarly, among the SWB indicators, we studied its cognitive dimension using the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Affective dimensions or a eudemonic approach deserve consideration to understand better the various issues of social participation linked to SWB (on the threefold structure of SWB, see Vanhoutte, Reference Vanhoutte2014). More so, studies examining various dimensions of SWB submitted possible differing association or mechanisms with social participation (Warr et al., Reference Warr, Butcher and Robertson2004; Li et al., Reference Li, Jiang, Li and Zhang2018).

Beyond specific indicators, a more ideological remark concerns measuring the social participation value through its association with SWB. As mentioned in the Introduction, this is a relatively new trend. In fact, until the 1980s retired wellbeing was a socio-political issue considered at a collective level, while individual (and consequently subjective) wellbeing emerged at the end of the 1990s as a new political ambition for old age (Collinet and Delalandre, Reference Collinet and Delalandre2014). In this context, the capacity to remain active became the condition for this wellbeing. The capability approach especially opposes this view as any utilitarianism conception of wellbeing, by defending a definition of wellbeing as the ‘real freedom’ individuals have to live the life they ‘have reason to value’ (Sen, Reference Sen1999: 285). In addition to the issues of inequalities affecting lifestyle opportunities, the proponents of the capability theory are concerned with the adaptive preferences mechanism, whereby expectations would be lowered depending on the status and associated life opportunities. This would lead to reducing the cost of inequalities in terms of SWB and life satisfaction. Nonetheless, we think that examining life satisfaction as a component of SWB is coherent with the important investigation line in gerontology on older adults’ adaptation strategies (e.g. Baltes and Baltes, Reference Baltes, Baltes, Baltes and Baltes1990; Rowe and Kahn, Reference Rowe and Kahn1997). In this context, the capability approach and critical gerontology have the merit to put in perspective and to underline the normative aspect behind both activation and SWB.

Finally, the focus of our study on Swiss data limits the generalisation of the results, since socio-cultural contexts can influence the forms of social participation as well as their links with satisfaction with life (Vogelsang, Reference Vogelsang2016). Nevertheless, we believe that studying Switzerland is informative as it poses a good example of both a wealthy and unequal society. It has one of the highest life expectancies and is one of the richest parts of the world, however, the life expectancy of the less-educated stagnates, and about 20 per cent of its older adults live below the poverty threshold (Oris et al., Reference Oris, Gabriel, Ritschard and Kliegel2017; Remund et al., Reference Remund, Cullati, Sieber, Burton-Jeangros and Oris2019). In addition, Switzerland has fully adopted the model of active ageing in its old-age policy (Conseil fédéral, 2007). Finally, the various Swiss regions make the country diverse (territorially, culturally, socio-economically and even politically), reflecting in large part the diversity of north-west Europe. Overall, our findings on the links between life satisfaction and social participation conform with the various trends propounded in other national contexts, while having the advantage to remove barriers between research fields (e.g. family and personal relationships, formal public participation or leisure activities) and to link them explicitly to social inequalities. In this context, our results invite further study in other countries or an international comparative perspective.

Diversity and social inequalities in social participation challenge active ageing

Overall, our results highlight the particular significance of participation through involvement in institutionalised ties and/or sociability in private contexts. Following a critical perspective, they underline the existence of various social inequalities in the access to these forms of participation: more modern ones – that are more valued in a social context promoting individualisation and self-realisation and in the context of ageing societies – are more socially stratified, showing an accumulation of advantages for an elite group of globally hyperactive older adults. In particular, those who represent the new cohorts of retired people – young old, more educated and in relatively better health (Remund et al., Reference Remund, Cullati, Sieber, Burton-Jeangros and Oris2019) – can be opposed to the older ones who are much more dependent on family or religious circles to preserve some meaningful social participation. Furthermore, our results emphasise the importance of more community-based, traditional forms of participation: they are equal across the social strata and appear particularly crucial for the more vulnerable – and globally less-participative – older adult.

In this perspective, the oldest men from the popular classes seem particularly at risk of a lack of meaningful participation opportunities. While women are more frequently poor, living alone and facing health problems, they are simultaneously advantaged regarding friendship sociability and religious practices. This last activity is even more important for the older cohort and among the less educated. In addition, the fact that the oldest men constitute a small minority of the population contributes to their vulnerability, making their condition less visible.

Our results have important implications towards the ‘active ageing’ concept as a key issue in both scientific and political debates on ageing, linking social participation with wellbeing. Our study demonstrates an interest in adopting a broad and multifaceted definition of social participation and support literature defending the multi-dimensionality of the active ageing concept (Marsillas et al., Reference Marsillas, De Donder, Kardol, van Regenmortel, Dury, Brosens, Smetcoren, Braña and Varela2017; Del Barrio et al., Reference Del Barrio, Marsillas, Buffel, Smetcoren and Sancho2018). In particular, results underline that meaningful social participation activities are not necessarily the same from both an individual perspective (e.g. SWB) and from a societal one, as supported, for instance, through productive or even solidarity models of active ageing, which focus on the contribution of older people to society. Further, we showed that the dominant discourses of active ageing, which so often focus on the productive definition of social participation, or generally the level of practices through the promotion of physical activity (Del Barrio et al., Reference Del Barrio, Marsillas, Buffel, Smetcoren and Sancho2018), contribute particularly to an elitist vision of ageing that is observed essentially among a minority of the older adults: the most socio-economically favoured. In this sense, we agree with other authors describing active ageing as a product of – built by and for – the upper class (Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2020). In addition, the focus on formal public participation tends to promote a more masculine model of ageing (Baeriswyl, Reference Baeriswyl2018).

Conversely, in the perspective of SWB, promoting participation should include efforts to allow each older adult to access the form that has meaning for him or her. In this context, private forms of sociability, which are more common among the older adults, or religious attendance, a practice important for more vulnerable categories, should be considered.

Such results raise questions for the future. Previous studies showed that in secularising Switzerland, as in most of the Western world, church attendance is decreasing across time and the birth cohorts (Agahi and Parker, Reference Agahi and Parker2005; Ajrouch et al., Reference Ajrouch, Akiyama, Antonucci, Wahl, Tesch-Romer and Hoff2007; Broese van Groenou and Deeg, Reference Broese van Groenou and Deeg2010; Baeriswyl, Reference Baeriswyl, Burnay and Hummel2017). The transformations affecting family life are well-documented (Widmer, Reference Widmer2016). Conversely, the increasing importance of elective social ties, such as friendship, have been theoretically and empirically demonstrated (Allan, Reference Allan2008; Baeriswyl, Reference Baeriswyl, Burnay and Hummel2017). Collectively, these trends suggest a possible decline of meaningful participation chances for the most vulnerable who could face an additional accumulation of penalties. Further studies are needed to understand better how social participation and its links with life satisfaction are changing and will be distributed among older adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Swiss National Science Foundation for its financial assistance. The authors are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and their valuable suggestions on this paper.

Author contributions

MB participated in the data collection, formulated the research question, conceptualised the study, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. MO supervised the data collection, helped in analysing and interpreting the data, and critically appraised and approved the final version of the paper.

Financial support

This work was supported by a Sinergia project (grant number CRSII1_129922/1) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research LIVES – Overcoming Vulnerability: Life Course Perspectives (NCCR LIVES; grant number 51NF40-160590), which are both financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All participants gave their written informed consent for inclusion in the study before participating. The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol has been approved by the ethics commission of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Geneva (project identification code CE_FPSE_14.10.2010). The database is available at the Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences (https://forscenter.ch/).