I. Introduction

It is a bedrock assumption of many international legal scholars that courts are institutionally best suited to protect the international rule of law and human rights, and that quasi- and non-judicial alternatives are less desirable—if not insufficient or even harmful.Footnote 1 The end of the Cold War sparked a stunning proliferation of international courts (ICs), but today the appetite of states for establishing international judiciaries has largely disappeared,Footnote 2 and backlash against ICs has become a recurring concern.Footnote 3 The tectonic shift in the geopolitical context, with the American empire and the rule of the West fading and a multipolar world order with China as a new superpower emerging, has likely ended the “temporary golden age” of ICs.Footnote 4 At least, the current zeitgeist renders the establishment of new ICs increasingly unlikely as states grow more wary of losses of control that independent courts typically induce.Footnote 5 Tom Ginsburg even predicts that with the rise of authoritarian regimes, “we should expect international law to increasingly take on the character of that demanded by authoritarians”Footnote 6—which likely means less “third-party dispute resolution mechanisms in the form of a court.”Footnote 7

At the same time, global governance still creates multiple accountability and human rights lacunas that require oversight or even an effective remedy. States seeking to provide oversight mechanisms and individual remedies at the international level are likely to opt for less intrusive and more flexible quasi- or non-judicial review mechanisms because “[s]uch ‘softer’ forms of dispute resolution … reflect more accurately the political contours of the current international system.”Footnote 8 Today, there already are numerous alternatives to international adjudication that were designed to increase the level of control exercised by member state-principals over their reviewer-agents.Footnote 9 One of the most important manifestations of this phenomenon are what I call international complaint mechanisms (ICMs) such as the World Bank's Inspection Panel (WBIP) and Compliance Advisor/Ombudsman (CAO), the ILO's Committee on Freedom of Association (CFA), the Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee (ACCC), the UN treaty bodies, and the former ombudspersons of the UN transitional authorities in Kosovo and East Timor.Footnote 10

I use a three-part working definition of these bodies: First, an ICM is an (ordinarily subsidiary) organ of an international organization (IO), composed of independent experts vested with compulsory jurisdiction who conduct legal review to assess compliance with international norms. Second, an ICM serves as triadic dispute resolver between individuals, communities, and/or NGOs adversely affected by alleged non-compliance on one side and the responsible state or IO on the other side. In this triad, the former are entitled to unidirectionally file complaints against the latter before the ICM. Third, the mandate of the ICM is institutionally highly constrained, reflecting the founding member states’ intention to guard themselves against unintended role expansions. The lack of binding decision-making powers—a feature that is shared by all IMCs—best encapsulates these constraints,Footnote 11 entitling the scrutinized states and IOs to adopt or reject the reports and recommendations submitted by ICMs at their will.Footnote 12 Nevertheless, private persons and entities have to date lodged more than ten thousand complaints with various ICMs and have often received substantial relief.Footnote 13

The growth of ICMs raises important normative issues that are embedded in a broader debate about the just design of global institutions.Footnote 14 That debate reflects public international law's built in tension between realist pragmatism and principled aspirations, between apology and utopia.Footnote 15 Is it normatively acceptable to establish more flexible and less intrusive complaint mechanisms given the power structures of the international legal system? Do they promote the international rule of law or are they a lamentable degradation of traditional judicial forms of adjudication? To what extent are and can they be structured to ensure meaningful oversight of states and IOs and to protect the rights of affected individuals and communities?

The Ombudsperson to the ISIL (Da'esh) and Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee (OP) is one of the most controversial and remarkable ICMs.Footnote 16 It was grudgingly established by the UN Security Council (S.C.) in 2009 in response to the Kadi judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to save the ISIL and Al Qaeda sanctions regime established in 1999 by S.C. Resolution 1267 (1267-sanctions regime), thereby empowering a single individual, the acting OP, to review the listing decisions of arguably the most powerful international institution. Yet the OP faces serious institutional constraints: it is neither institutionally independent nor does it have the power to render binding decisions. This raises the questions whether this kind of mechanism could become a blueprint for global governance in a more turbulent world order or whether it only constitutes a fig leaf that purports to legitimate the S.C.'s sanctions regime. How we evaluate the success or failures of the high-profile OP in terms of protecting due process rights and providing accountability may have important ramifications for the design of future global institutions.

The literature about the OP reflects the broader debate about ICMs. It is characterized by a stark controversy between proponents and critics of the OP mechanism. While both agree that legal protection for listed persons should be provided by an independent oversight body, they hold contrasting views on whether the OP is institutionally sufficient to provide such review. Proponents see the OP model as providing court-equivalent legal protection that is the best institutional solution for the highly political context of the S.C.Footnote 17 Instead of fixating on courts as the universal ideal model, this view argues that context-appropriate institutional models should be developed beyond the state and that the OP model should be consolidated and expanded.Footnote 18 Conversely, critics insist that only a judicial body can guarantee sufficient legal protection for the listed persons,Footnote 19 and that the OP constitutes a fig-leaf that contributes to stabilizing the sanctions regime—a global security exception incompatible with the rule of law.Footnote 20

Both of them overlook the tension between principle and pragmatism that is inherent in the OP's nature as an alternative to adjudication—a tension that international legal scholars will likely increasingly have to grapple with in a possibly more authoritarian and less judicialized international law. Before engaging in principled and abstract debates about the merits and demerits of the OP mechanism—and of other ICMs for that matter—we need to better understand and evaluate how these bodies operate in practice, their institutional features, procedures and decision-making techniques, and what prospects and limitations they have in providing an effective remedy for individuals and private organizations harmed by states or IOs. Although ICMs are an important phenomenon in international dispute settlement, we still lack a clear understanding of these issues.Footnote 21

This Article seeks to contribute to the global debate about alternatives to adjudication by providing a detailed case study of the OP. Most analyses of the OP focus on the period shortly after its establishment and on the flawed institutional design set out in the legal texts of the S.C. resolutions. Today, however, there is a significant body of practice from the first decade of its existence, allowing for a systematic, nuanced, and empirically grounded evaluation of the OP.

To do so, the analysis proceeds in three steps. Part II puts the OP into the broader context of UN targeted sanctions, providing a brief overview of the 1267-sanctions regime and explaining its serious accountability and human rights deficits that call for independent review. It further dives into the diplomatic history of making the Resolutions 1904 and 1989 that established and transformed the Office of the OP to better understand the motivations and political compromises that resulted in the creation of the OP mechanism.

Part III explores the institutional design and the practice of the OP mechanism. It demonstrates the shortcomings of the OP mechanism: the informality of the process that makes it less fair, the non-binding nature of the recommendations that allows the permanent members of the S.C. to block every disliked delisting recommendation, and the lack of institutionalized independence that potentially compromises the OP's ability to render impartial decisions. Despite these institutional inadequacies, Part III documents that the OP is surprisingly effective. Although the S.C. and its Sanctions Committee are legally entitled to override the OP's delisting recommendations, they have never actually done so. The OP has capably countered the constraints concerning independence and procedural fairness with professional integrity and innovative lawmaking. In sum, the case study about the OP illustrates how an ICM that was designed and assumed to be “soft” was transformed into a moderately robust international review mechanism that advances regard for the international rule of law even in the institutionally difficult and highly politicized S.C. environment.

Part IV assesses whether and when the institutional model of the OP merits replication in other contexts, cautiously drawing two broader lessons for other ICMs. First, it argues that ICMs have the institutional capacity to incrementally improve over time to better fulfill their normative mission as complaint mechanisms based on their influential role as triadic dispute resolver and the transnational character of its dispute settlement if officeholders engage in legally and politically skillful institution-building. Second, it suggests that heightened procedural requirements for overriding recommendations of ICMs may constitute a promising option beyond the binarity between bindingness and non-bindingness.

The Article concludes with the argument that there is value in establishing even weak independent review bodies, despite serious and likely persistent limitations, because institutional dynamics have the potential to compensate for many shortcomings built into the body at its creation. Instead of pitting legally binding ICs and non-binding ICMs against each other, the emphasis should be on building islands of independent legal review (whether judicial or extrajudicial) in the turbulent sea of international relations.

II. Context and Genesis

International legal scholarship lacks an empirically grounded understanding of the practice of ICMs generally and the OP specifically. This Article provides a case study about the OP to fill that gap.Footnote 22 It relies upon a variety of sources beyond legal texts to examine the OP and its institutional environment, including publicly available documents, small-scale statistical measures, and semi-structured qualitative expert interviews with key actors, including all former ombudspersons, their staff, attorneys representing petitioners in the OP process, members of the monitoring team of the 1267-sanctions regime, and diplomats who were sitting in the Sanctions Committee and participated in the drafting of the pertinent S.C. resolutions.Footnote 23 This Part begins the case study by outlining the broader institutional context in which the OP operates and the international political process that led to its creation.

A. In Need of Independent Review: A Sketch of the 1267-Sanctions Regime

The OP forms part of the UN sanctions regime. To maintain or restore international peace and security, the S.C. is authorized under Articles 39 and 41 in Chapter 7 of the UN Charter to impose economic sanctions on states and individuals that are legally binding on all UN member states. On the basis of these far-reaching Chapter 7 powers, the S.C. has established thirty different sanctions regimes since 1966, fourteen of which are currently still in force, each administered by a separate UN sanctions committee.Footnote 24 The most elaborate and controversial is the 1267-sanctions regime, a counterterrorism instrument against Al Qaeda (and later also ISIL) created in response to 9/11, which is virtually unlimited in time, geographical reach, and number of persons who may be designated.Footnote 25

The 1267-sanctions regime reflects a tectonic shift in the sanction practice—away from comprehensive trade sanctions against states toward targeted sanctions against individuals. At first glance, this new direction appears both gentler and more effective, as innocent populations are spared from potentially disastrous humanitarian consequences and instead the responsible leaders are sanctioned. However, the switch to targeted sanctions against amorphous and geographically dispersed terrorist organizations created a new dilemma.Footnote 26

The regime establishes a novel form of international security law through which the S.C. effectively exercises international public power over individuals.Footnote 27 The S.C. itself targets individuals by placing them on the so-called Consolidated List. It does so via its subsidiary body, the 1267 Committee, thereby eliminating to a significant extent the state as a mediator between international law and its citizens—and eliminating with the state its infrastructure of parliament and courts that controls the executive and protects individuals. The S.C. justifies this broad authority with questionable reliance on the right to preventive self-defense against the diffuse enemy of terrorism, which can strike at any time to threaten international security.Footnote 28 The sanctions are thus preventive, not punitive; the relevant question is therefore not whether someone is guilty, but whether someone poses a threat.Footnote 29 The sanctions interfere with the targeted individuals’ human rights to property, freedom of movement, personality, and family, and severely affect their daily lives.Footnote 30 Sanctioned individuals have all their assets frozen, including bank accounts used to pay rent and receive salaries, and bans on travel and on acquiring weapons are also imposed.Footnote 31

The S.C. initially showed little sensitivity for the serious accountability and human rights vacuum it had created.Footnote 32 In its original form, the 1267-sanctions regime lacked even rudimentary procedural safeguards, drawing metaphorical comparisons with Kafka's literary account The Trial.Footnote 33 Listed individuals were neither informed or heard in advance, nor were they told the reasons for listing. Their sole legal remedies were diplomatic protection, later trivially expanded through the creation of the Focal Point, which was largely limited to facilitating communication between listed persons and the reviewing states.Footnote 34 Nevertheless, numerous U.S. nominations were—even if some of them contained only very little identifying informationFootnote 35—mostly just rubber-stamped by the sanctions committee in the aftermath of 9/11.Footnote 36

The S.C. has improved the listing regime through incremental steps in response to widespread criticism,Footnote 37 but descriptions of the listing process in legal literature today still tend to paint a caricature of the 1267-sanctions regime based on its original form. In current Committee practice, however, the number of clearly false listings has gradually declined, if not disappeared altogether.Footnote 38 The listing process has become a long, arduous, and information-intensive process for the designating state,Footnote 39 and listing designations are commonly withdrawn as a result.Footnote 40 The S.C. requires member states to take all possible measures to notify listed individuals and entities,Footnote 41 to make available a publicly available Narrative Summary of Reasons for the Listing,Footnote 42 and a more detailed Statement of the Case.Footnote 43 In addition, Resolution 1822 (2008) has established an annual review that requires the review of all listings at least every three years—even if just to remove deceased or falsely identified persons from the List.Footnote 44

The basic governance vacuum inescapably remains: The 1267-Sanctions Committee, staffed by diplomats from the fifteen-member S.C., is an intergovernmental and power-political forum that is institutionally unsuited to designate individuals (with serious human rights implications), let alone to adjudicate their delisting applications. The listing process is highly political.Footnote 45 Any state, including a non-member, can nominate an individual it believes is “associated” with Al Qaeda or ISIL for listing, without providing evidence or intelligence underlying the nomination. There are virtually no deliberations about listing designations at the usually non-public meetings of the Committee,Footnote 46 and listings are approved through a no-objection procedure.Footnote 47 As a result, the Sanctions Committee does not review designations as a collective body, even though—or perhaps because—states typically have little incentives to diplomatically snub another state by explicitly rejecting a listing nomination simply to protect from sanctions an Islamist terrorist suspect that the other state believes poses a terrorist threat. This combination of the culture of secrecy in the sanctions committee, the absence of collective deliberation, and the political nature of its sanctions decisions makes the listing process structurally prone to error and abuse.Footnote 48

There may be some valid reasons for giving a highly political and diplomatic, almost apotheosized intergovernmental institution like the S.C. the mandate to maintain international peace and security,Footnote 49 but its Sanctions Committee is institutionally ill-suited to individualized administrative action causing serious human rights infringements. The listing process itself suggests that the S.C. does not conform to the rule of law-principles that we should use to evaluate its work as an international institution that exercises international public power against individuals.Footnote 50

B. Creating the Ombudsperson: Insights into the Negotiation History

It is not surprising against this background that the practices of the 1267-sanctions regime raised widespread criticism. It is, perhaps, more surprising that this criticism triggered serious reflection inside the S.C.—an institution perceived by its member states, especially the five permanent members (P-5), as sovereign and empowered to take any measure they deem necessary to ensure peace and international securityFootnote 51—about how to make the sanctions regime more just.

The greatest weakness of the 1267-sanctions regime was arguably the disregard for listed persons’ right to be heard and right to effective review by an independent institution.Footnote 52 The institutional solution to this problem was the creation of the OP—an independent review body tasked with examining, upon receipt of a delisting petition, whether the listed petitioner is associated with Al Qaeda or ISIL, conducting its own investigations and making a recommendation to the 1267-Sanctions Committee on whether the petition should be granted or denied.

Put in perspective, its establishment through Resolution 1904 and the strengthening of this mechanism through Resolution 1989 is one of the most astonishing institutional developments in the S.C. context and in the field of ICMs. This Part explores the genesis of the OP. Based on accounts of diplomats who were involved in the drafting of those resolutions, it provides insights into the negotiation history of Resolution 1904 (A.) and Resolution 1989 (B.), suggesting that the establishment and strengthening of the OP mechanism constituted an unlikely reform conducted under exceptional circumstances.Footnote 53

1. The Making of Resolution 1904 (2009)

The P-5 of the S.C. did not agree to establish the OP on the courage of their convictions but instead because of outside pressure and because of specific conditions that cannot be easily reproduced. The S.C. was then—unlike today—still capable of meaningful compromise and action. The early days of the Obama presidency in the United States created a political window for international institution-building.

The P-5 encountered heavy criticism for the 1267-sanctions regime from various actors. Within the UN framework, state leaders at the 2005 World Summit called on the S.C. to ensure a fair and clear process,Footnote 54 and, in 2006, then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan urged the S.C. to provide listed individuals the right to be heard and the right to review by an effective, independent, and impartial review mechanism.Footnote 55 The UN human rights machinery, from the high commissioner for human rights to the Human Rights Council and beyond, unanimously condemned the S.C.'s sanctions regime.Footnote 56

Some member states advocated for reform through the Group of Like-Minded StatesFootnote 57 that put forward various proposals for the establishment of an independent monitoring body, ranging from the expansion of the Focal Point, to the creation of a Special Advocate with access to intelligence, to a panel of experts.Footnote 58 One of these proposals, originally put forward by Denmark, was the establishment of an ombudsperson,Footnote 59 seeking to transplant the Scandinavian ombuds tradition to the international plane.

The most important impetus for reform came from the CJEU's Kadi judgmentFootnote 60 that annulled the EU regulation incorporating the applicable S.C. resolutions into EU law for violating EU fundamental rights.Footnote 61 As a result, EU member states were legally prevented from implementing the UN sanctions, sparking fears that Al Qaeda money would be diverted through Europe in order to avoid the sanctions thereby creating an EU-wide “hole in the sanctions net.”Footnote 62 The S.C. acted out of concern about the lack of legitimacy and effectiveness of the sanctions regime.Footnote 63

The establishment of the OP was an extraordinary diplomatic achievement. After all, it was surprising that the P-5 would accept an independent oversight body interfering with how they ran the 1267-sanctions regime. Although non-permanent S.C. members such as Austria and Mexico, as well as the Group of Like-Minded States, played a significant role in the diplomatic negotiation,Footnote 64 the framework and central rules were negotiated in typical S.C. fashion in a small circle among the P-5, with the decision-making dynamics remaining largely obscure to outsiders.Footnote 65

Among the P-5, the United Kingdom and France were the strongest advocates for the OP mechanism. Because they were bound by the CJEU's Kadi ruling, the two states hoped that its establishment would dispel the CJEU's objections and resolve the norm conflict between the UN Charter and EU law.Footnote 66 The UK in particular was a key player in this process because its own domestic version of the Kadi case, the Ahmed proceedings, was then pending before the British Supreme Court, and it had the ear of the United States based on their “special relationship.”Footnote 67

By contrast, all three non-European P-5s, China, Russia, and the United States, initially took the stance that Kadi was a European problem that the Europeans should deal with themselves, though the United States understood that bringing an independent court in line in a liberal constitutional system may not be as simple.Footnote 68 An additional source of institutional reluctance shared between the United States and Russia was the potential effects of the OP mechanism on the S.C.'s primacy. In their view, the Council is an inherently political body that should not be held accountable to a quasi-judicial body.Footnote 69

As the lead country in counterterrorism,Footnote 70 as the central force behind the establishment of the 1267-sanctions regime, and as the country that designated the most individuals on the Consolidated List, the United States was arguably the key player in the establishment of the OP. Resolution 1904 ultimately passed because the United States supported it, assumed the role of key negotiator, and submitted an ambitious and influential draft resolution.Footnote 71 However, U.S. support was not a given.Footnote 72 While the Bush administration likely would not have agreed to its establishment,Footnote 73 there was serious skepticism even within the Obama administration.Footnote 74

Underlying the internal U.S. decision-making process was an interdepartmental conflict between two of the most powerful departments of the U.S. government, the U.S. Department of State and the U.S. Department of Treasury.Footnote 75 The former viewed the establishment of the OP as a means to end the legitimacy crisis of the 1267-sanctions regime, accommodate European partners, and realize President Obama's credo of a “false . . . choice between . . . safety and . . . ideals.”Footnote 76 By contrast, the U.S. Department of Treasury, a key actor in U.S. sanctions policy due to its financial dimension (“asset freeze”),Footnote 77 opposed this reform for several reasons. First, Treasury was confident that U.S. entries on the Consolidated List were correct because they were based on extensive intelligence and on the domestic listing process conducted by the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), which was subject to domestic judicial review.Footnote 78 Second, Treasury resented the additional workload that the OP process was expected to create.Footnote 79 Third, it did not believe that “anything short of full independent judicial review” would “be sufficient to appeal to European courts.”Footnote 80 Ultimately, the State Department prevailed.

The OP mechanism created by Resolution 1904 represents a delicate compromise between the opposing camps. It was designed to meaningfully provide listed persons with the right to be heard and the right to effective review requested by Kofi Annan.Footnote 81 It was agreed that addressing these issues required the creation of “a neutral mediator-like position”Footnote 82 and a process in which the independent reviewer would provide the listed persons with reasons and listen to their side of the story. Against this background, the U.S. State Department drafted Annex II of Resolution 1904 from scratch, envisioning a process that met minimum requirements of due process, without putting an undue burden on the member states.Footnote 83 The biggest concession for the skeptics of the OP was agreeing to a “paradigm shift” for the S.C.,Footnote 84 empowering a single individual to review, second-guess, and potentially alter its listings.Footnote 85

However, the powers of the OP under Resolution 1904 were carefully limited. The P-5 agreed that the OP would have only the power to make observations on delisting requests. Anything more would have lost the Chinese and Russian vote and would have created internal problems for the U.S. government.Footnote 86 Resolution 1904 was finally adopted unanimously on December 17, 2009. In diplomatic circles, the establishment of the OP was considered a “sensation” that went far beyond what members of the Group of Like-Minded States had imagined.Footnote 87

However, the P-5's hope that the establishment of the OP would alone quell critics of the sanctions regime was not fulfilled. As U.S. diplomats described, “before 1904 even had a chance to breathe, the drumbeat of European litigation did not slow down”Footnote 88 and “from the earliest days, there was pressure to move in the direction of something more binding.”Footnote 89 About a month after the enactment of Resolution 1904, the UK Supreme Court in Ahmed dismissed the new OP mechanism noting that “[w]hile these improvements are to be welcomed, the fact remains that there was not when the designations were made, and still is not, any effective judicial remedy.”Footnote 90 Even worse, the European General Court (EGC) in Kadi II found the OP to fall short “of an effective judicial procedure for review of decisions of the Sanctions Committee.”Footnote 91

At the same time, the newly appointed OP Kimberly Prost pushed ahead. In her first two years in office, she submitted twenty comprehensive reports to the sanctions committee, seventeen of which proposed delisting, including some of the most controversial cases in the history of the OP.Footnote 92 For the United States, this was a surprising development as they had “a degree of confidence in the names that we had on the list that these were the right people and there was enough information,” and expected that “any delisting recommendation that would come from the Ombudsperson would be a very rare occasion.”Footnote 93 As a result, the P-5 faced the worst of both worlds: continued court challenges and a legitimacy crisis, along with interference with their sanctions practices by the new OP.

2. The Making of Resolution 1989 (2011)

Negotiations for Resolution 1989 took place in the spring of 2011. The developments since the adoption of Resolution 1904 had arguably hardened the stances and reinforced the views of the opposing camps. On one side, the EU members in the S.C., the UK, France, Germany, and Portugal, as well as the Group of Like-Minded States, intensified their push for strengthening the OP in order to address the concerns raised by the EGC in Kadi II—particularly because the appeal of the case was pending before the CJEU.Footnote 94 The United States was concerned about the legitimacy crisis of the 1267-regime.

On the other side, Russia and China were soured by the continued court challenges mounted against the 1267-regime despite the establishment of the OP. They questioned whether they should continue to help strengthen an accountability mechanism that was fundamentally at odds with their own preferences, without any guarantee that this further effort would end the regime's legitimacy crisis.Footnote 95 Moreover, the working atmosphere between Russia and the three Western members of the P-5 had deteriorated due to the disagreement about the no-fly zone over Libya that had been established in March 2011 despite Russia's concerns.Footnote 96

Still, that the mechanism had already been established made it easier in the negotiations “to convince people to take a few additional steps.”Footnote 97 The bottom line for the negotiators was that the objections articulated by the EGC had to be addressed in a meaningful way. Because granting the Ombudsperson binding decision-making authority over the S.C. “was absolutely not acceptable,”Footnote 98 a compromise emerged to upgrade the OP's decisions from observation to recommendation and, more importantly, to making the recommendation more difficult to overturn. Instead of requiring unanimity in the sanctions committee when adopting a delisting recommendation (consensus), overruling a recommendation would now require a unanimous resolution (reverse consensus). The CJEU upheld the decision of the EGC despite the improvements under Resolution 1989, causing frustration among member state diplomats,Footnote 99 but the reforms succeeded in substantially mitigating the legal challenges posed by litigation before European courts.Footnote 100

Russia only agreed to this compromise in return for a concession: the bifurcation of the Al Qaeda and Taliban sanctions regime. A “central motivation”Footnote 101 for the bifurcation was that Russia, which had designated most of the Taliban names to the 1267-list, was not willing to accept that its designations would be subject to the strengthened OP process.Footnote 102 The bifurcation thus had the ramification that due process for listed persons associated with Al Qaeda improved substantially, while those associated with the Taliban lost access to the OP.Footnote 103

III. Institutional Design and Practice

The establishment of ICMs is an institutional design choice that involves delicate tradeoffs. They are, as the genesis of the OP illustrates, frequently created in response to intense criticism for IOs or states for the lack of accountability and human rights deficiencies, yet their creation also involves contentious negotiations and resistance from some states.Footnote 104 Establishing softer, less intrusive, and thus more adaptable independent review mechanisms, often results from a carefully crafted compromise that promises to stabilize the concerned international institution or regime by accommodating calls for more accountability, participation, and better protection of human rights and the environment, while avoiding the role expansions typically associated with ICsFootnote 105 and thereby maintaining the favorable prevailing power structures.Footnote 106

The contradictory purposes that ICMs serve lead to normative questions about how we should evaluate their performance. This evaluation should not be based on instrumental member state preferences to keep them in check but on how they perform measured against the procedural and substantive principles that they are claimed to promote. ICMs are often defended as: (1) providing attainable access even for marginalized petitioners and an expedient process; (2) bringing states and individuals together in a fair process on the international plane; (3) offering some measure of independence; and (4) providing meaningful remedies for aggrieved private persons and organizations negatively affected by states and international institutions. Given that the normative debates concerning ICMs are oriented around these four metrics, we should also evaluate the performance of ICMs on this basis.

Reasonable doubts persist about whether ICMs can deliver on these promises. How we normatively evaluate ICMs should therefore also depend—in addition to these four criteria—on their capacity to overcome at least some of their institutional constraints to better fulfill their normative missions even if this does not conform to state preferences. In other words, it hinges on the institutional dynamics that ICMs do or do not set in motion.

This Part evaluates the OP based on these criteria of effective remedy, procedural fairness, independence, broad access and expedient process, and capacity to overcome institutional constraints through quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the existing institutional arrangements and practices. The analysis shows that the institutional constraints imposed on the OP are troubling on paper. Its delisting recommendations are not binding, it does not review the legality of the S.C. original listing decisions, its process is characterized by a high degree of informality that works mostly to the petitioner's disadvantage, it lacks institutional independence, and most listed persons have never filed a petition with the OP. If we ended our analysis here, the OP would seem like a poor and inadequate complaint mechanism.

The practice of the acting OPs tells a different story, however. It suggests that the officeholders, Kimberly Prost (July 2010–July 2015), Catherine Marchi-Uhel (July 2015–Aug. 2017), Daniel Kipfer Fasciati (July 2018–Dec. 2021), and Richard Malanjum (Feb. 2022–present), have, through politically shrewd institution-building, exploited the break-in-points in the legal framework set forth by the applicable resolutions. They have turned the OP into a surprisingly effective review body with very high delisting and compliance rates that provides impartial review and basic procedural rights to listed persons.

A. Remedy

ICMs are established to offer meaningful remedies,Footnote 107 but critics contend that mere findings and recommendations will have little impact on non-compliant states and IOs.Footnote 108 This argument is persuasive in theory, but in the practice of the OP the reverse consensus rule introduced by Resolution 1989 has ensured very high delisting and acceptance rates. In addition, critics argue that the remedies of ICMs are unduly limited to promoting future compliance instead of repairing past wrongdoing.Footnote 109 Although the remedy offered by the OP excludes review of original listing decisions, this section demonstrates that de novo review, the standard of review responsible for this exclusion, was pivotal in establishing an outcome-oriented model of individual justice that succeeded in getting dozens of petitioners off the List through a procedurally efficient and substantively focused no-nonsense approach.

1. Non-bindingness and Reverse Consensus

The OP lacks binding decision-making powers. It concludes every pending delisting petition with a “comprehensive report” that is strikingly similar to a court judgment.Footnote 110 The report outlines the standard of review, presents in detail the facts of the case, and sets forth a legal assessment as to whether there is sufficient information to provide a reasonable and credible basis for an association with Al Qaeda or ISIL.Footnote 111 The 1267-Sanctions Committee decides to follow or reject the recommendation. The OP decision is therefore best understood as an intermediate procedural step in a global administrative process.

However, the legal effect of these recommendations was significantly strengthened by the reverse consensus rule that the S.C. grudgingly introduced via Resolution 1989. According to paragraph 23 of the Resolution, recommendations to delist a person from the Consolidated List can be overruled in two ways with starkly different voting requirements. First, the Sanctions Committee can overrule the recommendation by consensus. Second, the Chair of the Sanctions Committee shall, on the request of a single Committee member, refer the matter to the S.C., which will decide on the basis of its ordinary voting rules laid down in UN Charter Article 27(3) “the question of whether to delist.”Footnote 112 In other words, the question put before the Council for a vote would not be “whether the name should be on the list, but whether the name should be removed from the list.”Footnote 113 This careful wording ensures that each permanent member retains its veto power to block any disliked delisting recommendation.

a. Findings: High Delisting and Acceptance Rates

In practice, no recommendation has ever been overruled even though the OP recommends delisting in most cases, and even though some P-5 members perceive “sanctions as a tool to ‘help get the bad guys,’ and due process [rights and procedural fairness] as ‘getting in the way.’”Footnote 114 The OP has recommended delisting in sixty-three out of eighty-six individual petitions in completed cases, or 73.3 percent, and in six out of six entity petitions, or 100 percent.Footnote 115 Member states’ representatives believe that “the vast majority of these names were truly names of individuals who deserve to remain on the list.”Footnote 116 Although the member states were opposed to vesting the OP with binding decision-making powers and retained fire-alarm controls, the Sanctions Committee has yet to overrule a recommendation or refer the matter to the S.C. in a single case.

b. Interpretations: Inducing Compliance by Accommodating State Preferences?

Of course, high acceptance rates of recommendations do not by themselves demonstrate that the OP provides an effective remedy. George Downs, David Rocke, and Peter Barsoom have shown, for example, that high compliance rates with international treaties arise if a treaty with shallow commitments does not require “states to depart from what they would have done in its absence.”Footnote 117 High compliance rates may also be achieved through a high degree of deference to states.Footnote 118

It is doubtful, however, that these general objections explain the interplay between the OP and the states sitting in the S.C., because it is unlikely that the Sanctions Committee would have delisted the petitioners in the absence of the OP's recommendations. The Committee kept the petitioner on the List until the recommendation and delisted the petitioner after the recommendation. It was the OP that made the difference.Footnote 119 Deference also does not seem to explain the high compliance rate for the OP's decision. It recommended delisting in almost three-fourths of all cases even though member states maintain that most listed persons should remain listed, suggesting that the recommendations do not defer to the views of the states, but instead frequently go against state preferences.

c. Explanations: Compliance Through Persuasion?

The high compliance rate might be explained through the persuasiveness of the OP's recommendations and the reputational costs of override, as advocates of the OP model argue.Footnote 120 The OP's reports are comprehensive legal documents, ranging between twenty and fifty pages with careful analysis of the facts and systematic legal reasoning that have been praised by diplomats for their thorough legal analysis, yet it is doubtful that the OP persuades most member states that the persons whose delisting it recommended are not associated with Al Qaeda or ISIL. Most, if not all, designating states continue to insist that the petitioner belongs on the List. State representatives are likely to put more trust in the findings of their intelligence agencies than in decision of the OP who frequently only sees a fragment of the existing intelligence on a terrorist suspect.

But states also have good reasons to accept the OP's delisting recommendations even though they are not persuaded. Most importantly, overriding the delisting recommendations of an independent legal expert who precisely was assigned with making this determination may appear illegitimate. Especially for low-level supporters of Al Qaeda or ISIL confronting the OP and paying the ensuing political cost may not be worth it.Footnote 121 Finally, the OFAC Sanctions List of the U.S. government, with its sweeping extraterritorial effect, provides additional assurances that even persons delisted from the UN Sanctions List can still be effectively targeted with the national List.

A look into the practice of the Sanctions Committee suggests that the reverse consensus rule is an important constraint on states’ ability to reject the OP's delisting recommendation. Although the Sanctions Committee accepts the recommendations without any objection in most cases,Footnote 122 two or three member states routinely vote against delisting recommendations.Footnote 123 The fact that some committee members object to the recommendations some of the time suggests that if the consensus rule of Resolution 1904 had not been substituted with the reverse consensus-rule of Resolution 1989, several delisting recommendations would likely have been overridden. Although legal expertise and reputational cost are significant factors, the design of the voting procedure and the high requirements for an override imposed by the reverse consensus rule appear to be more important.

Two cases that—due to the strict confidentiality requirements of the OP process—have received little attention in legal scholarship illustrate this point. In the case concerning Saudi citizen Saad al-Faqih, a former professor of medicine and outspoken critic of the Saudi government, the Sanctions Committee came very close to overturning the delisting recommendation—twelve of fifteen committee members voted to maintain the listing, only narrowly failing to meet the unanimity requirement.Footnote 124 In no other case did the Sanctions Committee ever come nearly as close to overruling the OP.Footnote 125 The case has been described by participants as “the watershed case”Footnote 126 and “the test case for the credibility of the ombudsprocess.”Footnote 127

The Saudi government had made it a high diplomatic priority to keep al-Faqih on the List, calling and exerting pressure on the “very highest level” of government in the process,Footnote 128 even calling the British prime minister and the German foreign minister, amongst others, only about this case.Footnote 129

In the end, Saudi Arabia managed to persuade twelve members, including all of the P-5, to support its campaign. Many of the members were persuaded not because they believed that al-Faqih truly belonged on the List, but only because they saw the diplomatic rationale in not alienating an important ally or state. Ultimately, however, Germany, South Africa, and Guatemala voted in favor of upholding the delisting recommendation even though this stand was not a given throughout the entire process.Footnote 130

The example of the Committee's decision-making process in the al-Faqih case demonstrates the importance of the reverse consensus rule. States represented in the S.C. do not form a homogeneous community of interests. They have very different interests regarding the OP mechanism. Some states such as the Group of Like-Minded States regard a robust OP institution as essential, but others reject it as an encroachment on the Council's authority.Footnote 131 Against this political background, it appears almost impossible to create a consensus in the Sanctions Committee for overruling a recommendation—at least one S.C. member will prioritize protecting the integrity of the OP process and therefore vote against override. Put differently, the reverse consensus rule transforms the recommendations into quasi-binding decisions in the framework of the Sanctions Committee, triggering a procedurally almost insurmountable voting requirement, especially in times of a deeply divided membership.

However, the twelve member states that had voted to overturn the al-Faqih recommendation still had a second legal avenue readily available—referring the matter to the S.C. where either a majority of nine members or the veto of a single permanent member would have sufficed. So why did those member states choose not to pursue this path? First, the Council may have better uses of its time than maintaining the listing of a single individual especially considering how difficult it generally is to put an issue on the S.C.'s agenda.Footnote 132 Second, the referral of delisting cases to the Council has been described, at least by supporters of the OP mechanism, as a “nuclear option,” because it would disavow the authority of the Sanctions Committee.Footnote 133 The member states that pursued this path were reportedly “talked down” from referral by U.S. State Department officials, which “saw the bigger picture and [knew that] it would have blown the whole process up.”Footnote 134 Notwithstanding strong disagreement with the OP, the P-5 ultimately concluded that retaining Mr. al-Faqih on the List was not important enough to risk damaging the credibility of the mechanism, not least because the sword of Damocles of the pending Kadi II litigation was still hanging over the S.C. at that time.Footnote 135

The decision-making process in the al-Faqih case demonstrates two things: First, member states are apparently less concerned about overturning the OP's recommendation by unanimity vote in the Sanctions Committee than by the ordinary voting procedures in the S.C. even though Resolution 1989 legalizes both pathways. Meeting the high threshold of unanimity seems, in the view of the member states, to legitimate overturning the recommendation, while referral to the Council is perceived more akin to power politics despite its legality. Second, the combination of the resource costs caused by putting issues on the S.C.'s tight agenda and the legitimacy costs for overturning delisting recommendations provide a robust safeguard against override despite the recommendations’ non-bindingness. However, the 1989-procedure also provides no guarantee for deviations from the Council's current practice in the event of changing circumstances, illustrating the fragility of the OP process. For illustration, consider this hypothetical: If Saudi Arabia did have P-5-status, it surely would have overturned the recommendation, and if ever a case came up in the Sanctions Committee that was as important to a real P-5 as the al-Faqih case was to Saudi Arabia, it would likely use its veto power—that is why they insisted on its presence in the first place.

Legal override of delisting recommendation is not the only avenue for member states to keep persons on the List as the Ali Ahmed Nur Jim'ale case concerning a Somali businessman who allegedly financed Al Shabaab, a regional offshoot from Al Qaeda, shows. Although this case was marked by strong disagreement between the OP and some member states, the Sanctions Committee formally followed the recommendation by delisting Jim'ale from the 1267-Consolidated List, but instantly placed him on the Somalia and Eritrea Sanctions List (today only Somalia) for the same purported conduct that the OP had deemed insufficient for continued listing.Footnote 136 U.S. diplomats have characterized this treatment as “our clever little way of getting around a very tricky problem.”Footnote 137 Although they have justified the relisting arguing that Jim'ale should have been placed on the Somalia sanctions list in the first place,Footnote 138 this approach violates rule of law-principles and exposes the double standards between the 1267-sanctions regime (with an OP mechanism) and the other sanctions regimes (without an OP mechanism).Footnote 139

d. Conclusions: Beyond the Binarity Between Bindingness and Non-bindingness

Safety valves by states are a common way of counteracting principal-agent dynamics and the associated risk that judicial or non-judicial agents exceed the limits of the authority delegated by the state principal.Footnote 140 In the negotiations to Resolution 1989, the safety-valve of paragraph 23 was one of the “most heavily negotiated paragraphs of the entire text.”Footnote 141 Especially for the United States and Russia, retaining this fire-alarm control proved to be conditio sine qua non for agreeing to the resolution.Footnote 142 They could not bring themselves to agree to a mechanism that would “upset or cheapen the power of the veto.”Footnote 143 For the United States, the thought that they could have voluntarily stripped themselves of veto power for delistings and then “someone [could] recommend[] removing Osama bin Laden from the list,”Footnote 144 was simply unacceptable. In addition, safety valves have a symbolic dimension. They underline that the principal—and not the agent—has the final say and does not subject itself to the agent's decision. Against this background, the art of the compromise consisted in strengthening the recommendatory powers without relinquishing veto power and the right to overrule the OP.

The practice of compliance with the recommendations indicates that fire-alarm controls may only have limited practical significance. As shown above, the recommendations were accepted by the Sanctions Committee in all cases (except for Jim'ale) despite the high rate of delisting recommendations. The al-Faqih case illustrates the resilience of procedural safeguards falling short of bindingness against override despite high political pressure in the diplomatic arena. The Jim'ale case indicates that even legal bindingness does not immunize OP delisting decisions against political override because member states have other means such as re-listing at their disposal. The OP hence serves as an example of how to create meaningful decision-making power that fall within a continuum between the binary poles of bindingness and non-bindingness.

2. De Novo Review and Disregard of Original Listing Decisions

The central legal standard for listing and delisting decisions is whether a person or entity is associated with Al Qaeda or ISIL.Footnote 145 This narrow and vague criterion provides the OP with little guidance but broad discretion. The politically savvy Kimberly Prost used this latitude to craft a standard of review tailored to navigate the minefield of S.C. politics that has shaped the Office and is meticulously followed by her successors. The OP evaluates delisting petitions de novo and looks only at the present. In other words, it does not review the legality of the original listing decision, but only whether there is a sufficient basis to continue listing.Footnote 146 This exclusive focus on the present benefits the designating state because it offers a face-saving procedure for false recommendations with no pressure to justify the original listing recommendation.Footnote 147 From the OP perspective, this approach avoids numerous minefields that would arise in a formal legal review of the S.C.'s listings. It creates a serious justice gap for the petitioner, however, because a listing is never established as unlawful, precluding recognition of wrongdoing, let alone reparations or damages.

De novo review is a clever legal innovation carefully tailored to the legal situation of listed petitioners, most of whom claim to have disassociated themselves from Al Qaeda or ISIL since their original listing. It ties in with the preventive and non-criminal classification of sanctions set forth in the relevant Resolutions and takes the S.C. at its word. If the nature of sanctions is preventive, its existence can only be justified by a persistent threat. But if a person no longer poses a terrorist danger, there is no reason to continue imposing anti-danger sanctions. From the perspective of the petitioners, the advantage of de novo reviews lies in the fact that new information may be presented, and the OP's review is not limited by the S.C.'s prerogative to assess the original listing decision.Footnote 148 The delisting decision does not hinge on the past, making burdensome and likely fruitless investigations into the S.C.'s decision making superfluous.Footnote 149

A critical feature of de novo review is that it disentangles the concern of providing an effective legal remedy to listed persons from the concern of holding the S.C. accountable for its original listing decisions. The OP succeeds in getting listed persons off the list without providing a meaningful accountability forum against the Council, making it easier for member states to accept its interventions. Critics assert that the purpose of de novo review is to accommodate the prevailing power structures within the sanctions regime, thereby legitimizing an otherwise illegitimate sanctions regime.Footnote 150 Although Prost sacrificed comprehensive legal review of human rights infringements by abstaining from review of the S.C. original listing decisions, there is much to suggest that she understood the S.C. would never have accepted review of the original listing decisions. All OPs are firmly convinced that review of original listing decisions would be politically unenforceable.Footnote 151

B. Procedural Fairness and Informality

ICMs bring together states and individuals in a joint procedure under international law—an arena that historically has been dominated by states. While proponents laud ICMs precisely for this feature, critics chide their processes as inadequate.Footnote 152 This begs the question what role the individual has in the process, and whether the process design lives up to promises of procedural fairness and due process.Footnote 153

The OP process is the product of the legal imagination of a few actors: U.S. lawyers and diplomats received substantial leeway from the other permanent members to invent a process with “no playbook on how to set any of this up,”Footnote 154 but also the creative practice and advocacy of the acting OPs. The process has two phases:Footnote 155 through “Information Gathering” the OP gathers the information relevant to the individual case from the states, from the monitoring team of the Sanctions Committee, and through independent research; through “Dialogue,” the listed person has notice and a meeting with the OP who presents the case against him and who hears the listed persons version of the relevant facts. Both phases are informal processes which accommodate the member states by protecting their control over classified and other information. Although the power asymmetries between states and listed persons remain stark, the OP has managed to alleviate some of the most negative effects through creative procedural practices.

1. Information Gathering

One of the greatest challenges for the OP is to gather the information necessary to make an informed decision on a delisting petition.Footnote 156 The factual support for listing process is often thin, especially for listings that are predominantly based on undisclosed intelligence sources.Footnote 157 Although the monitoring team provides the OP with all its collected information on a listed person or entity,Footnote 158 this information regularly contains the official listing dossier only.Footnote 159

The most valuable source of information in the delisting process are states.Footnote 160 Classified information based on intelligence is key in the Sanctions Committee, yet only states typically have this type of information. However, they are often unwilling to provide relevant information to protect their intelligence—a matter of vital importance in the field of counterterrorism in a multilateral context.Footnote 161 Resolution 1989 does not require them to do so; it merely asks member states “to provide all relevant information to the Ombudsperson, including providing any relevant confidential information, where appropriate.”Footnote 162 OPs cannot legally order, let alone compel, the provision of evidence in the fact-finding process. They ultimately rely upon the goodwill and cooperation of states.Footnote 163 As a result, states may reject requests for information or retreat to futile diplomatic phrases for justifying why they believe that a listing should be maintained.Footnote 164 They also may withhold exculpatory information,Footnote 165 and provide misleading informationFootnote 166—all without any consequences. They do not have to engage in a constructive process role and a rational legal discourse with the OP, and they regularly choose not to. This lack of cooperation by many states and the central role of intelligence in the OP process creates fairness dilemmas for the petitioner that the OP has primarily sought to address in three ways.

a. Assuming an Investigative Role

The OP meets this challenge in part by playing an active, investigative role in obtaining both incriminating and exculpatory information.Footnote 167 It assumes, in some ways, the procedural roles of attorney and prosecutor.Footnote 168 The OP writes official letters to member states requesting case-relevant information, meets with diplomats and security officials from member states to emphasize the importance of a request, to build trusting relationships, and to explain delisting recommendations to designating states in private meetings while listening to their objections,Footnote 169 concludes agreements on access to classified information,Footnote 170 and undertakes independent research on social networks.Footnote 171 Although advocates of ombudspersons praise this information-gathering process as an institutional strength of the mechanism,Footnote 172 they overlook that fact-finding and trust-building activities are weak mechanisms as compared to the legal power to order the production of evidence.Footnote 173

b. Requiring Updated Information to Maintain Listing

Second, the OP leverages de novo review to create strong incentives for member states that wish to maintain a listing to provide sufficient information even if they are legally not obliged to do so.Footnote 174 De novo review puts pressure on the member states to continuously update the justification for the listing in the present. In the absence of sufficient information, it can bring about the delisting of a listed person considering the OP's strong recommendation power, benefitting the petitioner even if he fails to provide new information. When member states assert, as some still do, that because “[w]e do not have updated information, therefore the grounds for the listing remain,”Footnote 175 they entirely miss this point. The crux of de novo review is precisely that the grounds for the listing disappear if states fail to justify the listing in the present.

c. Admissibility of Intelligence

Third, the unreliability of classified information raises the issue of admissibility. The OP has implemented a compromise between the concerns of the member states and the petitioners. With no formal rules of evidence for the OP process, Prost deliberately invented a highly flexible and permissive evidentiary standard that avoids a priori excluding intelligence information as evidence from the outset.Footnote 176 The evidentiary standard requires the OP to assess “whether there is sufficient information to provide a reasonable and credible basis for the listing.”Footnote 177 Although this wording reiterates that mere suspicion or an unproven allegation is not sufficient to uphold a listing,Footnote 178 the approach provides the Office with a high degree of flexibilityFootnote 179 and accommodates member states’ sensibilities with respect to the admissibility of intelligence. An evidentiary approach that disqualified classified information might have called into question the OP's institutional viability.Footnote 180

Instead, the OP lumps all available information together to assess whether the listing should be revoked or upheld. Unrestricted “truth”-finding enjoys priority over strict rules on the admission of evidence. This approach is a concession to member states, which value the accuracy of the sanctions list higher than procedural fairness for the listed person.Footnote 181 The latter must rely on the OP's professional sensitivity to properly assess the inherently unreliable sources of evidence. But the OP has alleviated the risks for petitioners arising out of the broad admissibility of intelligence by creating another informal procedural rule that caught some member states off guard. She made it clear early on that allegations without provision of the underlying information are not considered in the process, ending any illusion for member states that they could keep a person on the List simply by asserting “don't worry, we got info on this guy.”Footnote 182

2. Dialogue

The information collected serves as the basis for the “dialogue” with the petitioner.Footnote 183 For many listed persons, the dialogue is the only human encounter with a representative of the sanctions regime in the entire listing and delisting process—creating an element of humanity in an otherwise depersonalized sanctions regime.Footnote 184 The dialogue involves an intensive face-to-face meeting between the OP and the petitioner that lasts between several hours and two days, and is typically also attended by the OP's legal officer, the petitioner's attorney, and a translator.Footnote 185 Here, the petitioner learns the core of the listing reasons, is questioned about and can respond to incriminating information.Footnote 186 While the OPs believe that they convey the essence of the listing rationale to petitioners in sufficient detail,Footnote 187 the petitioners’ attorneys have expressed more skepticism.Footnote 188

The dialogue is informal and conversational.Footnote 189 It lacks most formal rules of procedure, including many features of criminal proceedings. The petitioner, for example, is not an accused who is innocent until proven guilty and faces the risk that a refusal to testify will be used as incriminating evidence against him.Footnote 190 He must instead convince the OP that he is not associated with Al Qaeda or ISIL to be taken off the list.Footnote 191 Incriminating intelligence information is only verbally described by the OP to the petitioner and his lawyer.Footnote 192

The process puts the petitioner in a vulnerable position. A petitioner must defend himself in part against detailed allegations, such as fifteen-year-old telephone conversations, without ever seeing the basis of the allegation, such as the transcript of the telephone conversation. From his perspective, the dialogue is more like an interrogation than a relaxed conversation.Footnote 193 As important as dialogue is for procedural fairness in the OP process, it does not create equality of arms in the asymmetrical sanctions regime. While the entire process leaves much to be desired in terms of procedural fairness, what mitigates some of the resulting concerns is the high rate of delisting recommendations. The outcome suggests that petitioners get a fair hearing despite procedural flaws.

C. Independence and Personal Integrity

Independence is a critical institutional feature of ICMs because both their credibility and their ability to hold states and IOs accountable depends upon it.Footnote 194 It is also essential to the OP's mandate as review body tasked with ensuring due process and reviewing individual complaints.Footnote 195 Yet the institutional arrangements designed to ensure the independence of ICMs attract criticism.Footnote 196 The Office of the OP is not, by any means, institutionally independent,Footnote 197 failing to meet even basic internationally established standards of independence.Footnote 198

The term of office is not fixed for a sufficient and reliable period, the security of tenure is not guaranteed, and the OP has no legally guaranteed self-governing autonomy. Its mandate must be continually renewed by resolution and was, until very recently, limited to eighteen months,Footnote 199 providing the S.C. with the regular opportunity to remove the institution simply by choosing not to pass a new resolution—all it takes, in other words, is the veto of one permanent member.Footnote 200 The lack of institutional independence and the self-imposed need to regularly renew the mandate means that the OP is a fragile institutional arrangement.

The officeholder is employed by the United Nations as an external consultant.Footnote 201 The OP is part of the general performance evaluation system of the UN SecretariatFootnote 202 and requires approval of all work-related expenses and travel. The consultancy contracts are surprisingly short-term, ranging from one to twelve months,Footnote 203 without any legal guarantee of renewal. They include no health insurance, no pension, and no sick leaveFootnote 204 but entitle the officeholder to terminate the contract with two weeks’ notice. This contractual framework and the OP's institutional design as a small single-leader institution resulted in the Office being vacant for almost a year between August 2017 and July 2018 following Marchi-Uhel's resignation—a period during which no decisions on delisting applications could be made.Footnote 205 While the selection process for the OP remains opaque, it appears that the UN Secretariat typically proposes several qualified candidates selected from applicants to a public job posting, and requests the member states in the Sanctions Committee, in practice especially the P-5, to unanimously agree on one of them.Footnote 206 The long vacancy period suggests that the selection process has become more controversial among the P-5.Footnote 207 The Office's staff are formally employees of the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, which serves as the S.C.'s international secretariat.Footnote 208 In other words, the OP's staff is hierarchically integrated into and reports to the very institution whose listing decisions the OP is supposed to monitor as an independent reviewer.

While the contractual arrangement is almost paradoxically provincial for a world organization, the rigid and inflexible bureaucratic culture of the United Nations is only one reason for the lack of institutional independence. It appears that some member states in the S.C. are determined to “keep the position as weak as possible.”Footnote 209 A brief window of opportunity for institutionalizing the Office of Ombudsperson ultimately failed because it was reportedly blocked by key P-5 members.Footnote 210 In any case, the UN Secretariat justifies its lack of action in this matter with its lack of political authority without express S.C. mandate and the predictable resistance from the UN budget committee, which is controlled by the member states.Footnote 211 The findings on independence, or the lack thereof, indicate that the lack of entrenched expectations about the specific configuration of institutional design features of ICMs such as the guarantee of independence facilitate increasing the level of control exerted by states over an ICM.

The lack of institutional independence has been countered by the personal integrity and professional diligence of the OPs. All former OPs have, not surprisingly given their prior professional background as criminal judges, approached delisting petitions with the self-conception of a judge.Footnote 212 They view targeted sanctions as a legitimate international legal instrument so long as due process is provided. They were just as determined to provide listed persons with due process as they were worried about recommending the delisting of an actual terrorist. Their professional skills in conducting rigorous interrogations and assessing the credibility of criminal defendants reassured member states. Moreover, there are no reported cases of delisted persons re-engaging in terrorist activities yetFootnote 213—which could otherwise undermine the acceptance by states of the OP mechanism.

While the common judicial background has shaped the Office of the OP, it was not a given from the outset. The United States had initially preferred “someone who comes from a government counter-terrorism agency, and someone who understands counter-terrorism and understands how intelligence works and how we identify these people.”Footnote 214 However, EU states wanted a candidate with a judicial background, and they ultimately prevailed.Footnote 215 This choice proved critical for the institutional trajectory of the OP. Although an adequate guarantee of independence requires more than reliance upon personal integrity, the latter can offset shortcomings in the former. The analysis in this section suggests that the success and failure of independence and the specific institutional arrangements designed to protect independence will not necessarily correlate neatly.Footnote 216 Independence can be realized, albeit delicately, without proper institutional arrangements.

D. Accessibility and Expeditiousness of the Process

One justification for establishing an ombudsperson institution is the ease of access and the expeditiousness of the proceedings. The OP seems to live up to its promise: it is credited for being “far more accessible than courts,”Footnote 217 and Annex II of Resolution 1904 sets short deadlines for the OP process.Footnote 218 Procedural efficiency is paramount. This Section shows that the informality of the process allows the OP to support listed persons in filing petitions and to conduct a swift and efficient process.Footnote 219 But it also demonstrates based on available data that only a modest number of listed petitioners and entities actually initiate proceedings, pointing to structural limitations of the OP in addressing the due process vacuum created by the 1267-sanctions regime.

1. Ease of Access

Although the OP is only entitled to act upon receiving a petition,Footnote 220 it compensates for this petition requirement with a low threshold for admissibility of petitions. A short e-mail from petitioners identifying themselves and briefly explaining the reason for the petition is sufficient to establish the OP's competence.Footnote 221 Even if the information contained in the first e-mail is inadequate, the OP and the legal officer will make proactive efforts to rectify the situation.Footnote 222 As a result, first-time petitions do not fail due to the admissibility requirements.Footnote 223 Those who seek access to the OP receive it.

To date, 99 of all 432 listed individuals, or 23 percent, have initiated OP proceedings.Footnote 224 The number for entities is even lower (29 out of 168 listed entities, or 17.3 percent). In addition, 114 individuals were delisted by the Sanctions Committee without completing the OP process as part of the annual triennial review established by Resolution 1822 (2008), thus removing the grounds for a successful petition. As a result, roughly half of all listed individuals did not petition the OP even though they are still listed.Footnote 225

Another serious legal protection issue is that petitioners, on average, did not initiate delisting proceedings until 9.1 years after they were placed on the Consolidated List. Twenty-eight individuals and twenty entities have been on the List for more than twenty years. Even if one replaces the actual listing date with the start date of the operation of the OP, when a meaningful legal remedy existed, it still took individual petitioners 4.9 years on average to file a delisting request. In part, this can be explained by cases in which the petitioners did not disassociate themselves from Al Qaeda or ISIL until sometime after the listing, so the delisting reason occurred later. Other probable reasons include: (1) lack of knowledge of being subject to sanctions and of the existence of the OP; (2) lack of prospects of success of an OP procedure; (3) lack of legitimacy of the procedure from the perspective of the listed persons; and (4) the risks involved for members of Al Qaeda or ISIL of revealing their identity and address.Footnote 226 If one considers the OP as a solution to the due process vacuum for listed persons caused by the 1267-sanctions regime, then it encounters structural limitations in that it only conducts review for a fraction of the listed persons and entities.

2. Expeditious Process

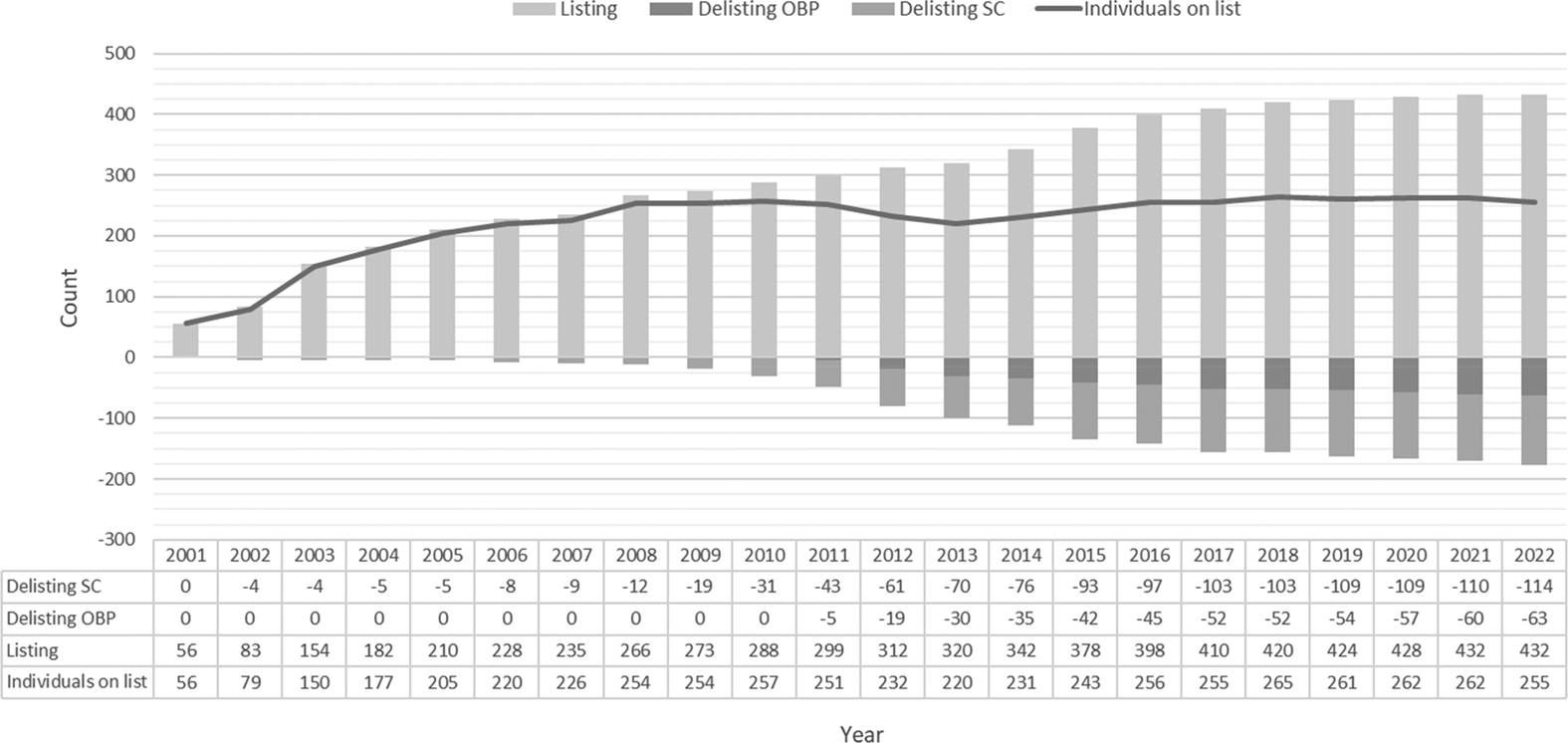

Once a petition is filed, the review process is conducted expeditiously. Figure 1 shows the duration of all proceedings to date, distinguishing the core OP process and the process in the 1267-Sanctions Committee after the OP's recommendation. On average, it takes only 7.4 months from receipt of the petition to the recommendation.Footnote 227 After completion of the Comprehensive Report, which is ultimately decisive for the outcome of the proceedings given the OP's strong recommendation power, another three months pass on average before a petitioner is delisted. This leads to a total of just 10.6 months between the start of the OP process and the decision of the Sanctions Committee. From the perspective of petitioners who typically have already been on the Consolidated List for several years prior to initiating the proceedings, such a speedy and pragmatic process arguably best serves their interests.

Figure 1. Duration of OP Process

Sources: Own calculations based on information provided by Office of the Ombudsperson, Status of Cases, at un.org/securitycouncil/sc/ombudsperson/status-of-cases.

E. Possibilities and Limits of Institution-Building

This Section tracks the institutional incrementalism of the OP mechanism to better understand its capacity to overcome institutional constraints. It also explores the impact of the OP on the List based on empirical data before finally addressing the criticism that the OP had the counterproductive effect of stabilizing the regime.

1. Mode of Institutional Incrementalism

The evolution of the OP mechanism is an example of institutional incrementalism.Footnote 228 The mechanism today is substantially more robust and better protects the due process rights of listed persons than the version enacted by Resolution 1904. It was improved through small and incremental steps over time. To name only a few examples: At its inception, the applicable consensus-rule gave every single S.C. member state the power to veto OP “observations.” Today, the reverse consensus rule provides the elevated “recommendations” robust protection from political override. Moreover, the petitioner was initially not informed about the identity of designating states, impairing his right to defend himself against allegations behind the listing. For the first 80 cases, only every other petitioner was assisted by legal counsel,Footnote 229 but since then until December 2021 all nineteen cases reviewed except one featured legal representation.Footnote 230 Favoring factors for this institutional incrementalism likely are the small-scale nature, ease of implementation and reversibility of the reform proposals, the disinterest of some member states in such procedural niceties, the OP's status as an expert, and the existence of allies, such as other UN institutions, some member states, NGOs, or academia.

The process of incremental improvement—the opportunities it provides and its structural limitations—is best illustrated by the transparency of the OP decisions. At the outset, the process was treated so confidentially that the goal of generating procedural fairness was almost reduced to absurdity: the so-called reasons letter submitted to the petitioner initially did not give the reasons for the recommendation that he either remain listed or was removed from the list.Footnote 231 But since 2017, the OP—and not the Sanctions Committee anymore—is responsible, albeit subject to oversight by the Sanctions Committee, for preparing a summary of the confidential report written by the OP which explains the outcome, including the reasons, and makes the decision comprehensible for the petitioner.Footnote 232 In most recent practice, the OP has moved to sending the petitioner redacted versions of the recommendation, rather than writing a summary, without objections from the Sanctions Committee.Footnote 233

This incremental institution-building has its limits, though. Although the small reform steps have substantially improved the process, more sweeping proposals have rarely, if ever, gained much traction. The OP's comprehensive reports are not disclosed to the public (not even in a redacted form), severely impairing public accountability of the sanctions regime and keeping the OP from entering a legal discourse with the public and legal scholars on fundamental procedural principles.Footnote 234 The Office is still not institutionally independent, despite repeated advocacy by the OP and the Group of Like-Minded States, the legality of original listing decisions of the Sanctions Committee are still not subject to review, and the OP is only entitled to review listings upon the request of a petitioner, and not ex officio as most ombudspersons around the globe.