Introduction

Exercise instructors shape the experiences of exercisers participating in group exercise classes. Indeed, these instructors have a significant effect on the social space, physical culture, and degree of inclusivity experienced by exercisers participating in group classes (Carron & Spink, Reference Carron and Spink1993). For these reasons, scholars have argued that exercise instructors are a key social determinant of exercise enjoyment, attendance, and adherence (Carron, Hausenblas, & Mack, Reference Carron, Hausenblas and Mack1996; Carron & Spink, Reference Carron and Spink1993; de Lacy-Vawdon, et al., Reference de Lacy-Vawdon, Klein, Schwarzman, Nolan, de Silva and Menzies2018; Petrescu-Prahova, Belza, Kohn, & Miyawaki, Reference Petrescu-Prahova, Belza, Kohn and Miyawaki2015). However, little is known about exercise instructors or the roles they play in older adult fitness: specifically the ways that they might impact the social inclusivity, enjoyment, and physical culture of group exercise for older adults. In order to assess the scope of the available scholarly literature on exercise instruction, we conducted a scoping review, which is a literature review method employed to evaluate the breadth and depth of extant literature (Grant & Booth, Reference Grant and Booth2009). Our aim in conducting this scoping review was to ascertain the roles that exercise instructors play in older adult group fitness. In this review, we highlight key findings and gaps in the literature, so that future research on exercise instruction can build upon extant literature and address significant lacunae in scholarship. The results of this review can initiate a conversation about the best practices and policies that would assist exercise instructors in creating more inclusive physical environments for older adults. As a result, the heterogeneous and rapidly growing population of older adults in Canada will feel more welcome in group exercise classes, which in turn could increase in the number of physically active older adults.

Background

Physical activity in older adulthood has been linked to positive psychosocial and health outcomes, including optimism, life satisfaction, positive affect, quality of life, and psychological well-being, as well as improved physical health and function (Battaglia et al., Reference Battaglia, Bellafiore, Alesi, Paoli, Bianco and Palma2016; Hartley & Yeowell, Reference Hartley and Yeowell2015; Kim, Chun, Heo, Lee, & Han, Reference Kim, Chun, Heo, Lee and Han2016; Yamada, Reference Yamada2016). However, only 12 per cent of Canadians 60–79 years of age meet the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines (Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, 2011; Statistics Canada, 2015). Older adults are less physically active than younger generations (Prohaska et al., Reference Prohaska, Belansky, Belza, Buchner, Marshall and McTigue2006). To address the generational discrepancy in exercise participation rates, a large corpus of scholarship has focused on the barriers to and facilitators of being physically active in older adulthood.

Social (in/ex)clusion of older adults has been identified as one such social determinant of physical activity participation (Biedenweg et al., Reference Biedenweg, Meischke, Bohl, Hammerback, Williams and Poe2014; Jacey, Clarke, Howat, Maycock, & Lee, Reference Jacey, Clarke, Howat, Maycock and Lee2009; Yamada, Reference Yamada2016). Social exclusion can occur for many reasons, but can be because of language, cultural, and literacy differences (Horne & Tierney, Reference Horne and Tierney2012; Shilling, Reference Shilling2016). In the context of exercise, cultural differences can centre around physical culture, which refers to the rules, beliefs, norms, and values that take place within spaces of physical activity and are reinforced by society (Lox, Martin, & Petruzzello, Reference Lox, Martin and Petruzzello2003). The dominant physical cultures for older adult fitness have been described as: (1) mainstream fitness culture’s focus on constant improvements in order to age “successfully” or “positively” (Katz, Reference Katz2001), and (2) the discourse of inevitable functional decline, dependency, and disability that is said to be part of the process of aging (Gilleard & Higgs, Reference Gilleard, Higgs, Gilleard and Higgs2013; Phillipson, Reference Phillipson, Johnson, Bengtson, Coleman and Kirkman2005). Indeed, scholars have argued that aging is associated with “letting oneself go” (Poole, Reference Poole2001) and that exercise is a form of anti-aging bodily management (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard, Higgs, Gilleard and Higgs2013).

Successful aging and the narrative of decline are two sides of the same coin: a problematic binary that results in ageist assumptions surrounding (in)ability and (in)activity (Calasanti, Reference Calasanti2016). Neither discourse fully appreciates the affective and communal dimensions present in the narratives of inactive older adults. Counter-narratives—as alternatives upon which physical cultures are built and embodied by older adults—present in extant literature include: pleasure (Phoenix & Orr, Reference Phoenix and Orr2014), fun/enjoyment (McPhate et al., Reference McPhate, Simek, Haines, Hill, Finch and Day2016; Poole, Reference Poole2001), and socialization (McPhate et al., Reference McPhate, Simek, Haines, Hill, Finch and Day2016; Tulle & Dorrer, Reference Tulle and Dorrer2012). These counter-narratives are embedded in Tulle and Dorrer’s (Reference Tulle and Dorrer2012) call for the creation of more inclusive physical cultures using a community-oriented approach. These counter-narratives are also aligned with the evidence that demonstrates that social inclusion, with an emphasis on enjoyment and socialization, is a determinant of physical activity (Resnick, Orwig, Magaziner, & Wynne, Reference Resnick, Orwig, Magaziner and Wynne2002; Yamada, Reference Yamada2016). Indeed, “…it is the social space that is created within [exercise] settings that is most influential in fostering their long-term adherence” (Hartley & Yeowell, Reference Hartley and Yeowell2015, p. 1635). This social influence may be why participants in group exercise, led by exercise instructors, demonstrate better adherence than solitary exercisers (Beauchamp, Carron, McCutcheon, & Harper, Reference Beauchamp, Carron, McCutcheon and Harper2007). However, the ways in which exercise instructors leverage these counter-narratives to shape more inclusive physical cultures within spaces of older adult fitness is unknown.

It is important to understand the ways in which exercise instructors affect the physical culture of the group exercise setting, because a better understanding of the ways in which instructors foster enjoyment and social inclusion can help to maximize older adult attendance at and adherence to exercise. The aim of this review of the literature was to elucidate the roles that the instructor plays in affecting these outcomes. Findings from this review can serve as an initial step toward understanding how instructors foster fun and inclusive exercise, as well as informing instructor best practices and policies for older adult group exercise.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of the literature on exercise instructors in older adult group exercise to conceptually map extant literature and address the gaps therein, to guide future research (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005). Scoping reviews serve as an initial method for appraising the breadth and depth of extant literature (Grant & Booth, Reference Grant and Booth2009). We deemed this the best method, because scoping reviews are a conventional means of: (1) synthesizing findings from studies of various designs that have not yet been comprehensively reviewed, (2) mapping concepts embedded within a broad scope of heterogeneous literature, and (3) describing findings in great detail (Mays, Roberts, & Popay, Reference Mays, Roberts, Popay, Fulop, Allen, Lark and Black2001; Pham et al., Reference Pham, Rajić, Greig, Sargeant, Papadopoulos and McEwen2014; Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun and Kastner2016). We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) standard framework for conducting a scoping review, which consists of five stages: (1) pose a research question, (2) identify relevant studies, (3) select articles for inclusion, (4) chart the literature, and (5) write up the results.

Stage 1: Research Question

With exercise instructors being such a vital social determinant of attendance, adherence, and enjoyment in physical activity (Carron et al., Reference Carron, Hausenblas and Mack1996; Carron & Spink, Reference Carron and Spink1993; de Lacy-Vawdon, et al., Reference de Lacy-Vawdon, Klein, Schwarzman, Nolan, de Silva and Menzies2018; Petrescu-Prahova, et al., Reference Petrescu-Prahova, Belza, Kohn and Miyawaki2015), we sought to uncover what roles the exercise instructor plays in older adult fitness that might affect these outcomes. Following Arksey and O’Malley’s (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) framework, the research question we posed to direct this scoping review was: What roles do exercise instructors play in older adult group fitness?

Stage 2: Identify Relevant Studies

Using Arksey and O’Malley’s (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) framework for conducting a scoping review, we identified relevant peer-reviewed literature on exercise instruction via database searching, reference mining, and scanning specific gerontology journals. The first author scanned the literature between January 2017 and March 2017 using a university library catalogue programmed to simultaneously search multiple databases (including, but not limited to: MEDLINE®/PubMed, PsycINFO, Social Science Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, and ProQuest Sociology) in the same manner as a Web search engine. We searched the following terms: (1) leader OR instructor, and (2) physical activity OR exercise OR fitness. This scan of the literature was then enriched with additional search methods from April 2017 to June 2017, during which the first author scanned the reference lists of the selected articles to identify literature preceding that which was already obtained, and conducted a manual search of relevant gerontology journals (e.g., The Gerontologist; Canadian Journal on Aging; The Journal of Aging and Physical Activity.) to identify pertinent articles that may have been omitted from the original database search. Follow-up scans in July 2018 and April 2019, using the aforementioned university library catalogue, yielded three new contributions to the corpus of literature identified in the initial search.

Stage 3: Selection of Articles for Inclusion, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The first author screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the potentially relevant literature identified from the search results. We included peer-reviewed qualitative and quantitative articles, commentaries, reviews, and book chapters from any country that addressed exercise instruction in the context of group exercise. We excluded literature that neither addressed exercise instruction nor group exercise. Thus, we excluded literature that focused on: (1) coaching, as this literature is sport specific, or (2) personal training, as this literature focuses on individual, rather than group, interventions. We did not impose date or language limits on the search; however, we did exclude grey literature (grey literature encompasses professional reports and documents published by professional organizations that train and certify exercise instructors, which do not undergo a peer-review process). We included studies that spoke broadly of social determinants of exercise that included, but were not limited to, the role of the instructor. However, for analysis, we only charted findings related to exercise instruction.

Given the small body of literature specific to exercise instructors of older adult fitness (only 33 of the 52 articles), we collectively synthesized the literature across all age groupings. Not only did this provide for a more meaningful presentation of results, but we were also conscious that older adults attend mainstream fitness classes that cater to persons of all ages and abilities, not just older-adult- specific group exercise classes. That said, in the review, we highlighted evidence specific to older adults where appropriate.

Stage 4: Charting the Literature

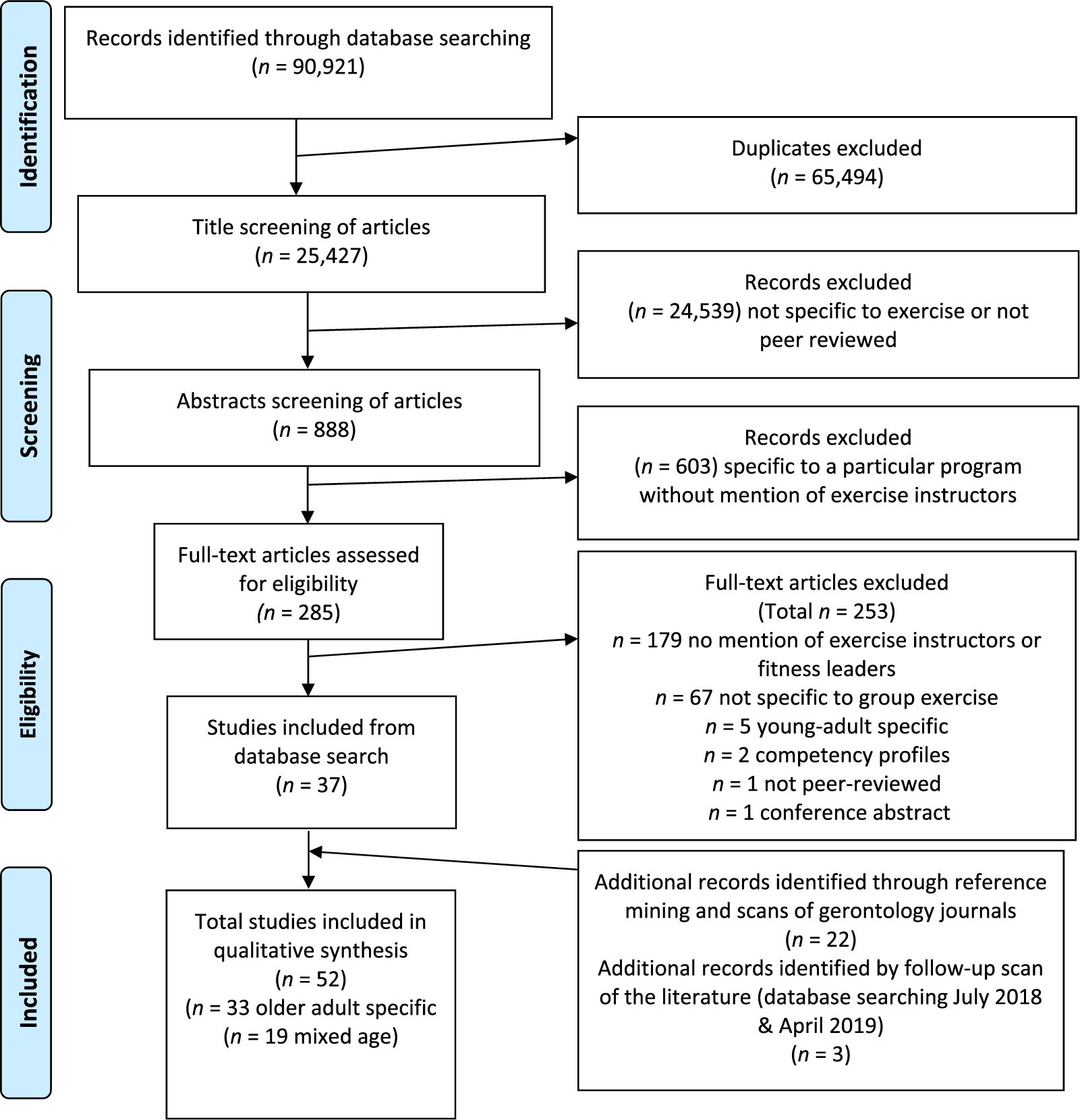

We ultimately selected 52 works for the scoping review (Figure 1). These works included peer-reviewed qualitative and quantitative studies of various study designs, reviews, and book chapters that examined group exercise instruction. The literature was predominately drawn from the fields of exercise and health psychology, as well as kinesiology and sport studies. Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) described the process of charting the literature for a scoping review as iterative in nature and similar to narrative analysis, in that themes and findings from the data are contextualized when entered into the form of a chart. Following Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005), we created a template to chart the data abstracted from the selected articles (see Appendices 1 and 2). The first author used a qualitative, thematic content analysis approach to identify descriptive information from the selected literature that specifically pertained to the role that the exercise instructor plays in older adult group exercise. The first author then charted this information onto the created template. Throughout this entire process, the second author acted as a mentor and “critical friend” as a means of achieving methodological rigor, thus providing feedback and encouraging reflexivity on both the process of conducting the review and the resultant charting of themes (Smith & McGannon, Reference Smith and McGannon2017).

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram. (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). *See Appendices 1 and 2 for detailed descriptions of the articles included in this review

Stage 5: Results

In synthesizing the included literature, we identified five themes, which revealed instructors’ vital roles as: (1) constructors of group social cohesion, (2) cultural intermediaries, (3) competent practitioners, (4) leaders and communicators, and (5) educators. A better understanding of these roles can be leveraged to inform best practices and policies regarding how exercise instructors can better foster more enjoyable and inclusive physical environments for older adults. This, in turn, could ultimately result in more welcoming physical spaces and an increased number of older Canadians who attend and adhere to group exercise interventions. In the section that follows, we elaborate on what the literature reveals about these five roles.

Results and Discussion

Social Cohesion

Group social cohesion, in the context of exercise, results in group solidarity toward a shared aim that meets the needs of those comprising the group (Christensen, Schmidt, Budtz-Jørgensen, & Avlund, Reference Christensen, Schmidt, Budtz-Jørgensen and Avlund2006). Among other factors, such as group size (Remers, Widmeyer, Williams, & Myers, Reference Remers, Widmeyer, Williams and Myers1995) and type of exercise format, the teaching ability of the instructor has been found to have a profound impact on the social environment in a group exercise class (Carron et al., Reference Carron, Hausenblas and Mack1996; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Schmidt, Budtz-Jørgensen and Avlund2006). This and more recent evidence support that the instructor’s capacity to engender social cohesion affects participant enjoyment (Fisken, Keogh, Waters, & Hing, Reference Fisken, Keogh, Waters and Hing2015; Gillett et al. Reference Gillett, Johnson, Juretich, Richardson, Slagle and Farkkoff1993; Loughead & Carron, Reference Loughead and Carron2004; Loughead, Colman, & Carron, Reference Loughead, Colman and Carron2001; Loughead, Patterson, & Carron, Reference Loughead, Patterson and Carron2008; Manson, Tamim, & Baker, Reference Manson, Tamim and Baker2017; Poole, Reference Poole2001; Yardley et al., Reference Yardley, Bishop, Beyer, Hauer, Kempen and Piot-Ziegler2006). To facilitate group cohesion, scholars recommended that instructors understand group dynamics and employ social integration and team-building activities, which might include social events outside of class (Carron & Spink, Reference Carron and Spink1993; Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Munroe, Fox, Gyurcsik, Hill and Lyon2004; Hawley-Hague, Horne, Skelton, & Todd, Reference Hawley-Hague, Horne, Skelton and Todd2016; Loughead et al., Reference Loughead, Patterson and Carron2008; Poole, Reference Poole2001). Overall, the literature indicates that fostering social cohesion could create a supportive, community-oriented culture.

Specific to the context of older adult fitness, some exercise programs employed peers as informal instructor assistants to engender social cohesion (Miyawaki, Belza, Kohn, & Petrescu-Prahova, Reference Miyawaki, Belza, Kohn and Petrescu-Prahova2016). This body of literature suggested that older adults may favor instructors who are similar to themselves (Beauchamp et al., Reference Beauchamp, Ruissen, Dunlop, Estabrooks, Harden and Wolf2018; Lox et al., Reference Lox, Martin and Petruzzello2003; Poole, Reference Poole2001). For example, one program changed from professional to peer instructors “…in response to consumer feedback that the fitness professionals did not understand and share their daily challenges” (Yan, Wilber, Aguirre, & Trejo, Reference Yan, Wilber, Aguirre and Trejo2009, p. 848), a disconnect that has been linked with the inhibition of vicarious learning and efficacy expectations (Werner, Teufel, & Brown, Reference Werner, Teufel and Brown2014). Older exercisers described peer leaders as more relatable (Gillett et al., Reference Gillett, Johnson, Juretich, Richardson, Slagle and Farkkoff1993; Layne et al., Reference Layne, Sampson, Mallio, Hibberd, Griffith and Das2008; Poole, Reference Poole2001), because they could empathize with how it feels to exercise in an aging body (Manson et al., Reference Manson, Tamim and Baker2017). This ability to relate might explain why some reports of peer-led exercise groups boasted higher adherence rates than professionally-led groups (Beauchamp et al., Reference Beauchamp, Ruissen, Dunlop, Estabrooks, Harden and Wolf2018; Stolee, Zaza, & Schuehlein, Reference Stolee, Zaza and Schuehlein2012; Waters, Hale, Robertson, Hale, & Herbison, Reference Waters, Hale, Robertson, Hale and Herbison2011). Younger instructors, however, expressed that it was sufficient for them to foster a bond with their older clients, despite their inability to identify with having an older body (Hawley-Hague et al., Reference Hawley-Hague, Horne, Skelton and Todd2016). Taken collectively, this research suggested a need to understand how instructors, of any age could better relate to clientele of diverse ages and abilities. In so doing, instructors could better create personalized interventions, while simultaneously fostering solidarity and social cohesion within a heterogeneous group.

Cultural Intermediaries

Physical culture refers to the rules, beliefs, norms, and values that take place within spaces of physical activity and are reinforced by society (Lox et al., Reference Lox, Martin and Petruzzello2003). One mechanism by which physical culture can be taken up and perpetuated within fitness spaces is by instructors, who have been found to serve as mediators between older exercisers and fitness culture (Miyawaki et al., Reference Miyawaki, Belza, Kohn and Petrescu-Prahova2016; Paulson, Reference Paulson2005). The literature reviewed herein demonstrated the tensions between the physical cultures built around successful aging and the narrative of decline/dependency, as well as pointing to the important role of the exercise instructor in promoting fitness cultures that align with older adults’ values in order to attempt to create an inclusive exercise space for older exercisers. Specifically, this literature provided examples of instructors promoting physical cultures that conflicted with older adults’ values, which negatively impacted participation and adherence.

First, the literature reviewed largely focused on senior-specific, falls-prevention programming versus mainstream fitness. Older adults rejected participation in falls-prevention programs, because their affiliation with such programs identified them as “fallers” who were at risk of decline (Katz, Reference Katz, Casper and Currah2011; McPhate et al., Reference McPhate, Simek, Haines, Hill, Finch and Day2016; Yardley et al., Reference Yardley, Bishop, Beyer, Hauer, Kempen and Piot-Ziegler2006). Instructors who embodied the decline narrative in their teaching created barriers for older exercisers; for example, by imposing more physical limitations on older exercisers in senior-specific programs (Kluge & Savis, Reference Kluge and Savis2001) than in mainstream fitness classes (Robinson, Masud, & Hawley-Hague, Reference Robinson, Masud and Hawley-Hague2016). Kluge and Savis (Reference Kluge and Savis2001) offered one such example of ageism in mainstream fitness, in which an instructor stated: “‘Everybody kick your butts with your heel! Older folks, do the best you can!’” (p. 81), thus conflating age and ability. This not only undermined the capacity for exercise enjoyment, but also created an unwelcoming fitness culture. Mirroring the tensions between successful aging and the decline narrative, the resultant social messages regarding appropriate exercise interventions for older adults exist in conflict with one another: keep active and exercise in order to avoid decline and dependency, but be safe, as the aging body is at risk of falling and becoming injured (Katz, Reference Katz, Casper and Currah2011; Pike, Reference Pike, Tulle and Phoenix2015).

Second, the literature reviewed suggested that instructors who embodied the discourse of successful aging were primarily concerned with improving older exercisers’ physical fitness capacities (Copelton, Reference Copelton2010; Fisken et al., Reference Fisken, Keogh, Waters and Hing2015; Tulle & Dorrer, Reference Tulle and Dorrer2012). The older exercisers in these studies viewed themselves as incapable of the intense exertions being imposed on them by the instructor, because of either real or perceived health concerns or the internalization of age-based norms discouraging older persons from intense activity (Gilleard & Higgs, Reference Gilleard, Higgs, Gilleard and Higgs2013; Tulle & Dorrer, Reference Tulle and Dorrer2012). The risk here was that the instructors’ perceived role—supporting a successful aging lifestyle and combating the functional decline of the aging body—ran contrary to the exercisers’ principal objective, which was enjoyment and socialization (Copelton, Reference Copelton2010; Paulson, Reference Paulson2005, Tulle & Dorrer, Reference Tulle and Dorrer2012). This is best exemplified in the work of Copelton (Reference Copelton2010), who concluded that, “For group leaders and fitness promoters, walking and steps are what count, but for walkers, talking and sociability count more” (pp. 314–315). Therefore, framing exercise as fun and social would not only be more aligned with the types of physical cultures for which older adults in this literature expressed a desire, but would also avoid some of the pitfalls inherent in relying solely on the dominant discourses of success versus decline.

Competence

Competence consists of the foundational knowledge, skills, and expertise on a particular subject that one should possess in order to ensure the basic understandings, abilities, and attitudes necessary for professional conduct (National Initiative for Care of the Elderly, 2010). In the context of exercise instruction, competencies are assured through training and certification. Indeed, competence has been found to influence how instructors approach class design and to engender participant enjoyment or dissatisfaction (Ecclestone & Jones, Reference Ecclestone and Jones2004; Fisken et al., Reference Fisken, Keogh, Waters and Hing2015; Markula & Chikinda, Reference Markula and Chikinda2016). The literature reviewed underscored the importance of having a competent exercise instructor, as older exercisers attributed great value to having an instructor who was knowledgeable about exercise, as well as about gerontology. Herein, exercise participants acknowledged the instructor’s role as competent practitioner, recognizing that certification was vital toward the assurance of technical proficiency, thus ensuring some degree of safe practice (Beaudreau, Reference Beaudreau2006; Brehm, Reference Brehm2004; Forsyth, Handcock, Rose, & Jenkins, Reference Forsyth, Handcock, Rose and Jenkins2005; Mehra et al. Reference Mehra, Dadema, Kröse, Visse, Engelbert and Van Den Helder2016; Olsen, Telenius, Engedal, & Bergland, Reference Olsen, Telenius, Engedal and Bergland2015; Taylor & Pescatello, Reference Taylor and Pescatello2016; Vseteckova et al., Reference Vseteckova, Deepak-Gopinath, Borgstrom, Holland, Draper and Pappas2018). Moreover, Oldridge (Reference Oldridge1977) argued that instructors should teach safety techniques to exercisers in order to increase exerciser self-efficacy and further reduce the likelihood of injury.

One could argue that the overemphasis on safety in some certifications could lead to the inappropriate use of interventions with older exercisers, such as chair-based exercise without due cause (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Masud and Hawley-Hague2016), which returns us to the argument regarding ageism and ableism in the previous section. However, the literature suggested that requiring instructors to possess gerontological competencies combated ageist exercise practices. In fact, Hawley, Skelton, Campbell, and Todd (Reference Hawley, Skelton, Campbell and Todd2012) found that training was positively correlated with a favorable attitude toward older adults, and that certification, work experience, and work setting all influenced instructor attitude and perception of older adulthood. However, certification and/or gerontological competencies are not always required for employment in Canada (Forsyth et al., Reference Forsyth, Handcock, Rose and Jenkins2005; Kluge & Savis, Reference Kluge and Savis2001; Taylor & Johnson, Reference Taylor and Johnson2008) despite the assertion that exercise instructor training for working with older adults requires more competence than training for working with younger adults (Ecclestone & Jones, Reference Ecclestone and Jones2004). Therefore, the role of competent instructor, which includes gerontological competence for older adult fitness, is not widely assured under current practices in Canada. Requiring certification to ensure competence should be considered a vital step in reducing ageism in Canadian physical cultures and improving the attendance and adherence rates of physical activity participation among Canada’s growing older adult population.

Leaders and Communicators

The literature reviewed indicated that older adults preferred instructors who demonstrated leadership behaviors and possessed interpersonal skills, specifically the ability to understand and communicate with exercise participants; motivate and demonstrate enthusiasm; personalize instruction and show interest in the client; be patient, caring, passionate, fun, flexible, and realistic; and foster trust with clients (Beauchamp, Welch, & Hulley, Reference Beauchamp, Welch and Hulley2007; Beaudreau, Reference Beaudreau2006; Bray, Gyurcsik, Culos-Reed, Dawson, & Martin, Reference Bray, Gyurcsik, Culos-Reed, Dawson and Martin2001; Caperchione, Mummery, & Duncan, Reference Caperchione, Mummery and Duncan2011; Manson et al., Reference Manson, Tamim and Baker2017; McAuley & Jacobson, Reference McAuley and Jacobson1991; Mehra et al., Reference Mehra, Dadema, Kröse, Visse, Engelbert and Van Den Helder2016; Miyawaki et al., Reference Miyawaki, Belza, Kohn and Petrescu-Prahova2016; Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Telenius, Engedal and Bergland2015; Poole, Reference Poole2001; Vseteckova et al., Reference Vseteckova, Deepak-Gopinath, Borgstrom, Holland, Draper and Pappas2018; Wininger, Reference Wininger2002). Literature in this domain also demonstrated that older adults desired instructors who were organized and prepared, encouraging, understanding, in good physical shape themselves, and persuasive but also respectful of individual abilities (Costello, Kafchinshi, Vrazel, & Sullivan, Reference Costello, Kafchinshi, Vrazel and Sullivan2011; Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Munroe, Fox, Gyurcsik, Hill and Lyon2004; Hawley-Hague et al., Reference Hawley-Hague, Horne, Skelton and Todd2016; Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Telenius, Engedal and Bergland2015; Vseteckova et al., Reference Vseteckova, Deepak-Gopinath, Borgstrom, Holland, Draper and Pappas2018). Therefore, older adults, as represented in this literature, rejected instructors who were unmotivated, dictatorial, impatient, and/or ignorant (Beaudreau, Reference Beaudreau2006). Positive correlations existed between increased attendance/adherence and instructors’ degree of experience, via either time devoted to professional practice or having undertaken motivational leadership training (Hawley-Hague et al., Reference Hawley-Hague, Horne, Campbell, Demack, Skelton and Todd2014; Seguin et al., Reference Seguin, Economos, Palombo, Hyatt, Kruder and Nelson2010).

Educators

Howley and Franks (Reference Howley and Franks2003) listed education as a key relationship-oriented leadership skill that instructors should possess, and it was said that the teaching ability of the instructor empowers group members through cultivating self-efficacy beliefs (Caperchione et al., Reference Caperchione, Mummery and Duncan2011; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Schmidt, Budtz-Jørgensen and Avlund2006; Izumi et al., Reference Izumi, Schulz, Mentz, Israel, Sand and Reyes2015). Despite its essential role in exercise interventions, the literature acknowledged that education was underemphasized in both research and practice (Franklin, Reference Franklin and Dishman1988; Markula, Reference Markula and Bresler2004; Oldridge, Reference Oldridge1977). Ecclestone and Jones (Reference Ecclestone and Jones2004) and Gillett et al. (Reference Gillett, Johnson, Juretich, Richardson, Slagle and Farkkoff1993) recognized the educative role of the instructor when they proposed “teaching skills and techniques” as a vital training topic for educating older adult fitness instructors. Herein, kinesthetic, or motor learning, was the primary subject of study recommended (Ecclestone & Jones, Reference Ecclestone and Jones2004; Gillett et al., Reference Gillett, Johnson, Juretich, Richardson, Slagle and Farkkoff1993), but elaboration citing specific educative methods was absent.

We could only identify two articles that argued for additional considerations beyond kinesthetic modes of education. First, recognizing that education is cognitive, affective, and kinesthetic, Kluge and Savis (Reference Kluge and Savis2001) argued that instructors should use a formal or informal learning style inventory, based on Bloom’s (as cited in Kluge & Savis, Reference Kluge and Savis2001) taxonomy of learning, with their older group exercise participants in order to tailor exercise interventions to how exercisers best learn. Second, Markula (Reference Markula and Bresler2004) posited that “…fitness instructor education, instead of merely focusing on the physical aspects of fitness, should also include critical social and pedagogical analysis” (p. 75). Her argument was based on the premise that exercise instructors teach the physical exercises, but also teach a hidden curriculum that implicitly reinforces social discourses embedded within physical culture, thus linking the instructor’s educative and cultural intermediary roles (Markula, Reference Markula and Bresler2004). As was previously mentioned, the dominant physical cultures tend to be built around the conflicting discourses of both successful aging and inevitable decline, and this influences the degree of inclusivity of the physical culture toward older adult exercisers. However, if instructors’ hidden curricula are composed of social cohesion, community, and enjoyment/pleasure, then the physical cultures may, in turn, be more inclusive. Hence, critical and reflective analyses that illuminate this hidden curriculum could be leveraged to inform educative practices that instructors might employ in older adult group exercise programs to foster more inclusive physical cultures. For example, practices could be integrated that explicitly reinforce positive physical cultures that promote group social cohesion and positive attitudes toward aging, while ultimately increasing participant enjoyment, attendance, and adherence.

Reflections

This scoping review provides a first step in identifying the roles that exercise instructors play in group fitness for older adults. This literature also elucidates that these roles are vital for creating pleasurable, inclusive group exercise classes for older adults to which a high percentage of fitness participants adhere (Bray et al., Reference Bray, Gyurcsik, Culos-Reed, Dawson and Martin2001; Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Munroe, Fox, Gyurcsik, Hill and Lyon2004; McAuley & Jacobson, Reference McAuley and Jacobson1991; McPhate et al., Reference McPhate, Simek, Haines, Hill, Finch and Day2016). However, attention to how exercise instructors educate their older adult clients is minimal in the literature (Howley & Franks, Reference Howley and Franks2003), despite the early-made assertion that “The exercise leader’s function…is educative” (Oldridge, Reference Oldridge1977, p. 87). Therefore, more research is needed into the educative role that exercise instructors, and the educational methods that they employ, play in fostering inclusive exercise environments for older adults. Also needed is inquiry into the practices that may be based on ageist assumptions and how these practices influence what exercise instructors teach.

To address the lacuna regarding the educative role of the exercise instructor, in the context of older adult group fitness, there is a great need to identify how exercise instructors facilitate somatic learning, which means learning that occurs by being mindful of corporal sensations, and embodied learning, which means holistic learning wherein the body is central, and which includes consideration of other epistemologies, such as emotional, spiritual, and cultural ways of knowing (Freiler, Reference Freiler2008). This calls for a juxtaposition of educational theory, embodied pedagogy and somatic learning specifically, with the literature on exercise instruction. To understand the context in which this learning takes place, there is the need to situate this literature within that of educational gerontology, the concerns of which are trifold: (1) teaching gerontology, in this case teaching gerontological competencies to fitness instructors; (2) education about aging to the mainstream populace, in this case as it relates to physical activity and aging; and (3) geragogy, which is teaching and educating older adult learners (Lebel, Reference Lebel1978; Glendenning & Battersby, Reference Glendenning and Battersby1990). Together, these frameworks could enhance our understanding of the educational role of the exercise instructor.

Limitations

This review is exploratory and includes literature spanning four decades, which indicates a need for more current evidence, as some findings may be outdated. It must therefore be acknowledged that the culture of physical fitness and the older adult demographic have both changed significantly during this time frame. Specifically, the historical context underpinning these studies has changed during the past 40 years, as have the features of the older adult populace. That said, the primary limitation of this scoping review is that it is, in fact, partial in scope. According to Tricco et al. (Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun and Kastner2016), “…scoping reviews have inherent limitations because the focus is to provide breadth rather than depth of information in a particular topic” (p. 9). The breadth of this review may also have limitations in that (1) much of the scholarship on exercise instructors is embedded in larger studies investigating social support as a determinant for exercise and physical activity, making it challenging to identify within the research on this subject; and (2) this review only included materials that were peer reviewed, excluding grey literature, which may have added insights to the topic of inquiry. Additionally, scoping reviews do not assess for quality in the literature reviewed (Grant & Booth, Reference Grant and Booth2009), and as such, this scoping review should be considered a starting point for further investigation, while acknowledging its inherent methodological limitations.

Future Research

In addition to the aforementioned need for future research examining the educational role of exercise instructors for older adults, as well as other topics identified throughout this article, further insight into the subject of exercise instruction could also be addressed by an updated systematic review, or meta-analysis, that both synthesizes extant literature and evaluates its findings based on methodological rigor. For example, of the literature reviewed herein, Carron et al.’s (Reference Carron, Hausenblas and Mack1996) meta-analysis provides an in-depth and structured analysis of social influences that affect exercise-related behaviors. However, this meta-analysis is outdated, signaling a need for a more systematic review of recent literature of social determinants of physical activity, specifically exercise instructors, and with attention to older adult fitness.

Implications for Policy

One of the emergent themes from this scoping review pertained to the requirement of professional competencies for exercise instructors and gerontological competencies for those working with older adults. Competencies are not universally required for exercise instructors, which has implications for exercise efficacy, as well as for client safety and enjoyment (Forsyth et al. Reference Forsyth, Handcock, Rose and Jenkins2005; Kluge & Savis Reference Kluge and Savis2001; Taylor & Pescatello, Reference Taylor and Pescatello2016). Additionally, requiring gerontological competence may reduce instances of ageism that take place in group exercise interventions (Hawley et al., Reference Hawley, Skelton, Campbell and Todd2012).

Given the growth of the older adult population in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2019), more older adults are likely to attend both mainstream and senior-specific exercise classes. Therefore, requiring gerontological competencies of only instructors who specialize in seniors’ fitness neglects older exercisers who attend mainstream classes. This scoping review highlights the importance of both fitness and gerontological competence, as demonstrated in the literature, which lends credence to policies that require certification of exercise instructors who work with older adults to ensure that they are competent practitioners.

Conclusion

The aim of this scoping review was to examine the corpus of literature on group exercise instruction and the roles that instructors play in older adult group fitness. The literature suggested that instructors’ roles are (1) to foster group social cohesion, (2) to serve as cultural intermediaries between fitness culture and older adult exercisers, (3) to serve as competent fitness and gerontology practitioners, (4) to be effective leaders and communicators, and (5) to be educators. A better understanding of these roles can ultimately result in older adults feeling more welcome in physical spaces, thus increasing the proportion of older Canadians who are physically active. Therefore, these findings can be employed to inform best practices and policies regarding how exercise instructors can create more enjoyable and inclusive physical environments for older adults. However, questions remain, and more research on the role of the exercise instructor in older adult group fitness is needed, specifically with attention to effective educational methods, skills, and approaches that promote inclusive physical cultures that are fun and social and that combat ageism.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980819000436