INTRODUCTION

Unintentional overdose has become the leading cause of injury-related death among Americans ages 25 to 64 years. 1 A comparable epidemic is under way in Canada, 2 with opioid misuse now the third-leading cause of accidental death in Ontario.Reference Madadi, Hildebrandt and Lauwers 3 , Reference Gomes, Juurlink and Dhalla 4 The World Health Organization has recommended the use of naloxone by lay responders for treatment of overdose, 5 and it has recently been added to the 2015 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiac arrest.Reference Lavonas, Drennan and Gabrielli 6 Health Canada recently removed the drug from the Prescription Drug List to increase access, making it available in Canadian pharmacies without a prescription. 7

Community-based opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs have been operational in the United States and Europe since the mid-1990s but are still relatively novel in Canada. These programs involve training people at risk of opioid overdose and their friends and family members with the skills to identify overdose situations, activate emergency medical services, and provide basic life support interventions, including the administration of intramuscular or intranasal naloxone.Reference Clark, Wilder and Winstanley 8 , Reference Walley, Xuan and Hackman 9 Program participants are provided with a naloxone kit containing the program’s training protocol, naloxone, and delivery devices. These programs have had success through overdose education and distribution of naloxone kits in several major Canadian cities,Reference Oluwajenyo Banjo, Tzemis and Al-Qutub 10 - Reference Leece, Hopkins and Marshall 12 with several community reversals of opioid overdoses reported and no adverse effects. The World Health Organization, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the U.S. Society of Toxicology have all advanced statements supporting these interventions and calling for wider access to these programs. 13 - 15

Due to the high rate of drug-related visits, 16 recurrent opioid prescribing, and routine encounters with opioid overdose patients,Reference Hasegawa, Espinola and Brown 17 the emergency department (ED) may represent an underutilized setting to identify patients at risk of opioid overdose and to distribute naloxone.

To expand outpatient overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) programs from the ED, physicians’ attitudes toward the programs and willingness to participate need to be evaluated. The objective of our study was to identify Canadian emergency physicians’ attitudes and perceived barriers to the implementation of take-home naloxone programs.

METHODS

Study design and population

We conducted a self-administered, anonymous, and confidential Web-based survey of emergency medicine (EM) resident and attending physician members of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP). A total of 1,658 physicians consented to receive surveys from the organization and were emailed a link to the survey using the Survey Monkey platform.Reference Lacroix, Stiell, Thurgur and Orkin 18 Participation was voluntary. CAEP physicians not practicing EM or who were not members of CAEP were excluded.

Survey content and administration

Fourteen survey questions (see Supplementary Material) were developed by the research team and piloted amongst a group of emergency physicians for face validity and clarity prior to distribution.Reference Karen, Burns and Mark Duffett 19 We constructed the initial survey questions based on expert opinion and review of the evidence.Reference Orkin, Bingham and Klaiman 20 - Reference Carter and Graham 22 We then conducted cognitive interviews with practicing emergency physicians, where the physicians responded to the survey. During this assessment, they were asked to vocalize anything that they felt was either unclear, uncomfortable, or any other thoughts they might have. Body language was observed as well, and physicians were questioned about what they were thinking if they appeared to be perplexed or uncomfortable. The final survey tool also included basic demographic information such as gender, EM certifications, years of experience, and practice setting. After the initial email distribution, two further electronic reminders were sent according to a modified Dillman method.Reference Dillman 23 All survey responses were collected electronically and anonymously. As an incentive, participants were invited to enter their email on a separate website upon survey completion for a chance to win a $250 gift certificate. The Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board approved this study.

Data analysis

Frequencies and means were calculated for each survey question, and a cross-tabulation chi-square analysis was performed for association of knowledge and barriers with the demographic information collected. All responses were used in the analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 459 physicians responded to the survey (response rate was 27.7%). Respondents are mostly male (63.9%), work in an urban tertiary centre (58.3%), and have a Certification in the College of Family Physicians (CCFP) EM designation (44.9%; Table 1). The majority of respondents reported prior knowledge of OEND programs (77.6%), mostly through popular media sources (59.4%), from a colleague/at a conference (54.2%), or scholarly media or journal (33%). A small proportion of respondents (14.5%) had cared for a patient involved in OEND programs, whereas 13.9% reported a direct involvement with OEND programs.

Table 1 Characteristics of survey respondents

CCFP=Certification in the College of Family Physicians (Canada); CCFP-EM=Certification in the College of Family Physicians (Canada) with special competence in Emergency Medicine; FRCPC=Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada.

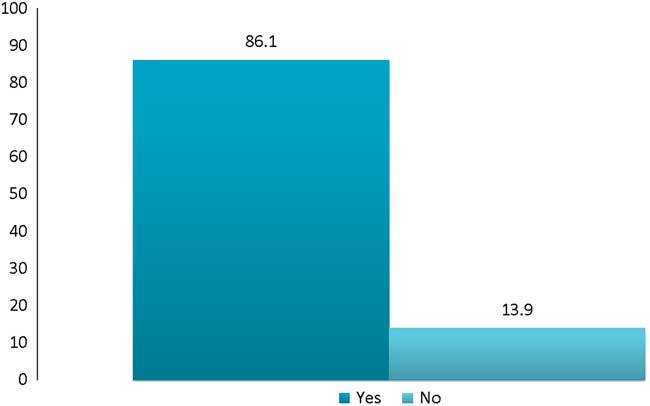

Respondents showed a positive attitude toward opioid OEND programs, with 86% reporting that they would be willing to prescribe or distribute naloxone from the ED (Figure 1). The chi-square analysis did not reveal a significant difference in willingness to prescribe based on gender (p=0.09), practice setting (p=0.74), or number of years in practice (p=0.13). The data analysis did reveal a significant association between willingness to prescribe naloxone and EM credentials or province/territory of practice; physicians with a CCFP-EM designation were less likely to distribute naloxone (p<0.01), as were physicians from the Maritimes (p<0.01).

Figure 1 Survey Respondents’ Willingness to Distribute Naloxone from the Emergency Department (%).

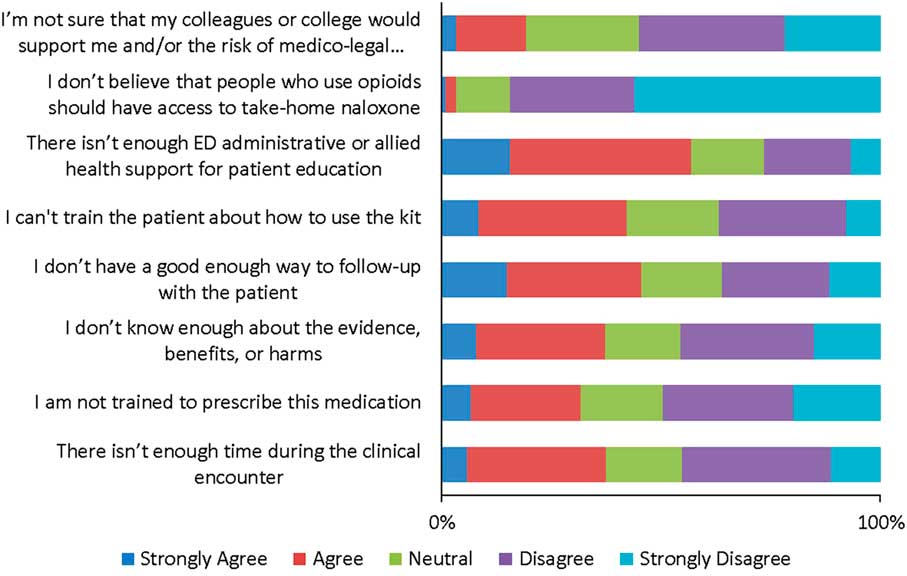

Survey respondents’ identified barriers to participation in opioid OEND programs are represented in Figure 2. Perceived barriers included lack of allied health support for patient education (57%), lack of access to follow-up (44%), inability to train the patient in the use of the kit (42%), lack of knowledge surrounding the evidence for take-home naloxone (37%), inadequate time in the clinical encounter (37%), and lack of training in the prescription of naloxone (31%).

Figure 2 Survey Respondents’ Identified Barriers to Distribution of Take-home Naloxone Kits from the Emergency Department.

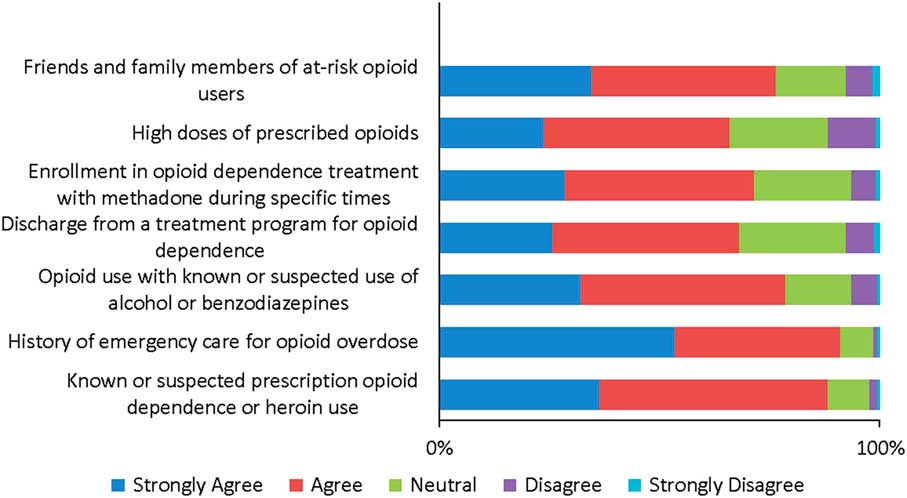

Respondents’ awareness of groups who may benefit from OEND programs is depicted in Figure 3. In addition to individuals at risk for overdose, 77% of respondents identified that friends and family members may also benefit from OEND programs. The groups that were identified as high-users of the ED, by respondents answering “always” or “frequently” to seeing them in their practice, were patients with known or suspected prescription opioid dependence or heroin use (72%), patients using high doses of prescribed opioids (69%), and patients with opioid use with known or suspected use of alcohol or benzodiazepines (68%).

Figure 3 Survey Respondents’ Awareness of Groups who may Benefit from Take-home Naloxone Programs.

When asked which member of the health care team was best suited to train recipients of OEND, emergency registered nurses and nurse practitioners were named most frequently (34% and 27%, respectively; Table 2).

Table 2 Member of the health care team identified as best suited to train recipients of take-home naloxone kits

RN=registered nurse.

DISCUSSION

Interpretation

This study found that Canadian emergency physicians are generally aware of and willing to distribute naloxone from the ED. Our respondents were in agreement with pre-specified groups who would benefit from OEND programsReference Lavonas, Drennan and Gabrielli 6 , Reference Orkin, Bingham and Klaiman 20 and identified lack of allied health support, time in the clinical encounter, access to follow-up, and lack of training as the most important barriers to implementation of these programs. Our findings that physicians with CCFP-EM designation were less likely to prescribe naloxone could be due to variations in the regional distribution of physicians, with more Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada (FRCPC) physicians working in larger cities where exposure to opioid overdose patients and ED-based OEND programs are more common. Provincial data are unfortunately lacking, which limits any conclusions about the willingness to distribute naloxone based on the scale of the opioid misuse problem in each Canadian province, a gap that has been recognized at a federal level and is currently being addressed by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. 24

Previous reports

The overwhelmingly positive attitude we found is different from what had been previously reported.Reference Beletsky, Ruthazer and Macalino 25 This could be explained by increased exposure to OEND programs as opioid overdose deaths and drug-related ED visits continue to rise, in keeping with the majority of our survey respondents’ reporting familiarity with these programs prior to this questionnaire. These programs have been widely adopted and sanctioned by respected institutions, especially in Canada with recent increased access to naloxone when it was removed from the Prescription Drug List and made available at no cost to people at risk for overdose. 7 The minister of health has also recently signed an interim order authorizing the expedited availability of intranasal naloxone in Canada for easier delivery and decreased risk to the first-responder. 26

Physicians recognize that people at risk for opioid overdose are frequently seen in the ED, and that this setting could be ideal for the implementation of OEND programs. The inclusion of opioid-associated resuscitative emergencies and OEND in the 2015 updated AHA guidelines for CPR and emergency cardiovascular careReference Lavonas, Drennan and Gabrielli 6 draws this intervention further into mainstream EM practice. A single-centre study of an OEND program in a Boston, Massachusetts ED found this setting to be feasible for education and naloxone distribution programs to a high-risk population in order to reduce opioid mortality.Reference Dwyer, Walley and Langlois 27 A recent study surveyed recipients of take-home naloxone from an ED in Vancouver, BC and reported that 68% of patients using opioids were willing to accept take-home naloxone, suggesting that the ED is an effective setting for this program.Reference Kestler, Buxton and Meckling 28 Further larger studies of ED-based programs are needed to evaluate implementation and cost-effectiveness.Reference Coffin and Sullivan 29

In our study, the willingness to distribute was not associated with practice setting or number of years in practice, making it unlikely that a generational difference could explain this change. This is comparable to a similar survey of American emergency physicians with regards to ED-based opioid harm reduction.Reference Samuels, Dwyer and Mello 21

LIMITATIONS

There are limitations to our study. Selection bias and non-response error are concerning, because respondents may have been more likely to have an interest or more positive sentiment toward the topic, and therefore may differ from non-respondents. This would increase our reported willingness to distribute naloxone. Our survey’s low response rate may also limit external validity. This number is lower than previously reported physician response ratesReference Karen, Burns and Mark Duffett 19 and may be explained by the design and length of the survey, a lack of engagement in the subject matter, or survey fatigue. We did receive responses from a large number of CAEP members (459) from all areas of the country, except Quebec. This brings forward the consideration of coverage error, given that the original language of distribution of the study by CAEP is English, despite the availability of French translation upon request. Emergency physicians who are not members of CAEP are also not represented in this population.

IMPLICATIONS

Our survey respondents identified time, institutional supports, knowledge, and training as barriers that should be addressed in the design of ED-based OEND programs to ensure success. Support from local and national leaders in EM, and education programs with focus on the evidence supporting naloxone distribution and recipient training may increase uptake of this intervention from the ED. Recent legislative changes in Canada empower any member of the patient’s care team to participate in OEND programs, which should only increase their use. The results of this study could inform the development of a workshop at a national meeting with the goal of dissemination of evidence and training in harm-reduction strategies from the ED. Future research should focus on implementation studies of ED-based OEND programs to demonstrate meaningful impact and describe how our identified barriers were overcome, as well as education strategies to address knowledge deficits.

CONCLUSION

Canadian emergency physicians are willing to distribute take-home naloxone to patients at risk for opioid overdose, but strategies that will facilitate opioid OEND implementation are necessary.

These data will inform the development of ED-based naloxone distribution programs, with emphasis on multidisciplinary training and education.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the University of Ottawa, Department of Emergency Medicine academic grant (2015-SP-10). AMO receives salary support from the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute, the University of Toronto Department of Family and Community Medicine, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research LL conceived the idea and secured research funding, collected data, and prepared the manuscript. LT, AMO, and IGS assisted with study design, supervised in the recruitment of participants and management of data, and revised the manuscript. All authors supervised in the conduct of the study and data collection, drafted the manuscript and/or contributed to its revision, and approved the final version. LL had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2017.390