Have incentives for politicians to conform to gender stereotypes diminished over time? In addition to the fact that female and male politicians speak about systematically different sets of political issues (Bäck and Debus Reference Bäck and Debus2019; Catalano Reference Catalano2009), another dimension on which gendered differences are said to arise is argumentation style. Gendered communication styles are thought to be rooted in stereotypes that create social expectations for women to act ‘like women’ and men ‘like men’ (Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly and Wood2012). If politicians internalise these expectations before entering politics, or if voters punish them for contravening gender stereotypes (Bauer Reference Bauer2015a; Boussalis et al. Reference Boussalis2021; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018), legislators are likely to engage in gender-role-consistent behaviour, and we should expect systematic differences in the political styles that female and male politicians adopt. Empirical evidence supports this view: compared to their male colleagues, female politicians' speeches are more emotional (Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien2019), less complex and jargonistic (Coates Reference Coates2015), less repetitive (Childs Reference Childs2004), and less aggressive (Kathlene Reference Kathlene1994), and they use different types of evidence to support their arguments (Hargrave and Langengen Reference Hargrave and Langengen2020).

We contribute to this literature by evaluating the degree to which gendered differences in political style vary over time. Consistent with work that views stereotypes as dynamic constructs (Diekman and Eagly Reference Diekman and Eagly2000; Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly and Wood2012), we argue that over the past 25 years in the UK, where we situate our study, several factors are likely to have decreased the degree to which UK MPs (and especially women) will conform to stereotype-consistent behaviours in Parliament. First, politicians are drawn from a broader population that has itself diverged from stereotypical communicative styles in recent years. Second, changes to the social roles played by women in public life, and in politics, have reduced the validity of gender stereotypes in the eyes of the public. Consequently, we argue that voters are less likely to sanction female legislators for gender-incongruent behaviours now than in the past. Finally, the increased prominence of women in Parliament and leadership roles is also likely to reduce the degree to which female politicians internalise expectations that they need to behave in ‘feminised’ ways. Together, these arguments lead to a central behavioural prediction that we test empirically: that UK MPs will conform less to gender stereotypes now than in the past; and that women, in particular, will adopt styles that are further from feminine stereotypes over time.

To evaluate this expectation, we examine politicians' styles as they manifest in one prominent legislative activity: parliamentary debates. We conceive of debating style as a characteristic of speech that is distinct from its content. Intuitively, the style of a speech reflects the manner in which an argument is delivered. In social psychology, women's ‘communal’ styles are thought to be marked by higher levels of emotionality, positivity, empathy and warmth, while men's ‘agentic’ styles are thought to be marked by higher levels of aggression, logic and confidence (Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly and Wood2012; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019). In political science, these concepts have been operationalised using a diverse set of indicators. We survey both literatures and identify eight styles that reflect the ideas of communality and agency, and are also – in principle – detectable in the speeches politicians deliver. The eight styles that we use as the basis of our empirical analysis are: human narrative, affect, positive emotion, negative emotion, factual language, aggression, complex language and repetition.

In addition to our substantive argument, our article also provides a methodological contribution to the measurement of style in legislative settings (Boussalis et al. Reference Boussalis2021; Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien2019). Our goal is to construct measures that closely approximate the conceptual definitions of each of the styles that we highlight in our review of the literature. For some styles, we use existing quantitative text-analysis measures that have been extensively validated in other settings (see, for example, Kincaid et al. Reference Kincaid1975). For others, we develop new measures that combine traditional dictionary approaches with a word-embedding model. Our strategy overcomes limitations of standard dictionary approaches, as it enables us to detect styles as they manifest in the specific context of parliamentary debate. Evidence from a human-validation task shows that our measures significantly outperform standard measures that have been used extensively in previous research on political style.

We apply our measures to nearly half-a-million speeches delivered in the House of Commons between 1997 and 2019 and report three main findings. First, in the early parts of our study period, we document patterns of style that are broadly consistent with expectations from the literature on gender stereotypes. Male MPs' speeches are marked by substantially higher levels of aggression and complexity, while female MPs' speeches are considerably more emotional and positive, and make greater use of human narrative. Second, and crucially, we find that these differences have reduced dramatically in recent years. In six out of eight styles, MP gender explains less variation in style use between individuals at the end of our study period than at the beginning. For cases where we report diverging behaviour over time, these stylistic shifts run counter to gender-role expectations. Third, we show that the evolving variation in style use has primarily resulted from women's decreasing use of communal styles and increasing use of agentic styles over time.

Our work builds upon a large literature (cited earlier) on gender differences in politicians' communication styles, the vast majority of which considers whether gender stereotypes accurately capture real behavioural differences at fixed points in time. By contrast, we show that the descriptive validity of prominent stereotypes of how men and women communicate is considerably lower in the contemporary House of Commons than it was in the past.

Our findings also have important implications beyond scholarly accounts of legislative politics. Prescriptive stereotypes for how men and women ought to behave are ultimately rooted in our collective understanding of how we expect men and women will behave (Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly and Wood2012). In politics, these prescriptions can form the basis of voter judgements about the behaviour of male and female politicians. Documenting when behavioural shifts run counter to gender-based stereotypes is important, then, because it potentially undermines these prescriptions and could thereby diminish the degree to which women will be subject to penalties for failing to conform to stereotypical expectations (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018; Ditonto Reference Ditonto2017).

Additionally, our results cast doubt on the idea that the election of more women into office will automatically result in a less adversarial and more deliberative culture in Westminster.Footnote 1 At least in the context of parliamentary debate, our findings suggest that such effects are unlikely to materialise because they are based on an outdated assumption about the distinctiveness of female MPs' political styles. In addition, by placing hopes of cultural change on newly elected women, proponents of these views may also be setting female politicians up to fail if their increased presence does not result in a ‘better’ political culture. To the extent that cultural change of this sort is a desideratum of modern parliamentary politics, our results suggest that hopes of affecting such change should not rely on the presumption that newly elected women will conform to anachronistic stereotypes; instead, purposive reforms to parliamentary practices may be necessary.

Gender, Stereotypes and Debating Style

Why might men and women in parliament employ different debating styles? Gender-role theory (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002) suggests that gender stereotypes concerning the typical conduct of men and women can affect behaviour via two main channels. First, repeated exposure to stereotypes from a young age may lead men and women to internalise expectations relevant to their genders, which then become self-imposed standards against which they regulate their own behaviour (Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly and Wood2012). Second, descriptive stereotypes (for example, the perceived tendency for women to be emotional) are often thought to lead to prescriptive stereotypes (for example, the view that women should be emotional), the violation of which leads to the imposition of social sanctions by others that further incentivise conformity with gender-based norms (Brescoll and Uhlmann Reference Brescoll and Uhlmann2008).

Female politicians are especially subject to pressures to conform to role-consistent behavioural standards, as voters punish women for displaying behaviour that counters feminine stereotypes. Voters form gender-biased impressions of candidates (Bauer Reference Bauer2015a) and penalise women for appearing to be too ambitious (Okimoto and Brescoll Reference Okimoto and Brescoll2010) or negative (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018), while rewarding them for displays of happiness (Boussalis et al. Reference Boussalis2021). These penalties are more acute when the campaign environment is characterised by ‘masculine’ issues (Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016) and are more commonly applied by low-attention voters (Bauer Reference Bauer2015b) and voters with sexist attitudes (Mo Reference Mo2015) or aggressive personalities (Bauer, Kalmoe and Russell Reference Bauer, Kalmoe and Russell2021). By contrast, voters are less sensitive to role-inconsistent behaviour by male politicians (Okimoto and Brescoll Reference Okimoto and Brescoll2010).

However, as political leaders, legislators are also expected to display behaviours consistent with leadership stereotypes. Men's historical occupation of leadership positions means that leadership stereotypes have been shaped by traditional ‘masculine’ traits, such as being assertive, competitive and outgoing (Koenig et al. Reference Koenig2011). The congruence between leadership stereotypes and masculine stereotypes therefore poses little challenge for male politicians to conform to both sets of expectations. By contrast, if women seek to conform to leadership stereotypes, they may risk incurring penalties for violating feminine stereotypes (Bauer Reference Bauer2017; Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Women must therefore attempt to balance a complicated array of behavioural expectations in a way that men do not.

Political scientists have evaluated whether these incentives induce male and female politicians to adopt systematically different political styles. We focus on one aspect of legislative activity where differences are likely to become manifest: political speech. On which dimensions of style should we expect gender differences? Of central concern in the social-psychology literature is the distinction between communal characteristics of style, which are associated with women, and agentic characteristics, which are associated with men (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019). These labels are heuristics for clusters of behavioural attributes, where communal characteristics are said to include being ‘affectionate, helpful, kind, sympathetic, interpersonally sensitive, nurturant, and gentle’, while agentic characteristics include being ‘aggressive, ambitious, dominant, forceful, independent, self-sufficient, and self-confident’ (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002, 574). By surveying the large empirical literature on gendered styles in political science, we identified eight styles that are representative of ‘communal’ or ‘agentic’ behaviour and that previous work has either shown to be associated with male or female use in politics, or expected to be associated with gender differences. We use these styles as the basis of our empirical analysis in the following.

We identified three ‘communal’ characteristics of style that are typically associated with women. First, women are said to make greater use of human narrative through reliance on personal experience, analogies and anecdotes in their speeches (Blankenship and Robson Reference Blankenship and Robson1995). This idea is supported both by politicians' testimonies (Childs Reference Childs2004) and by qualitative studies of political speech (Hargrave and Langengen Reference Hargrave and Langengen2020). Second, women are also thought to make greater use of emotional language or affect (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993), and there is clear evidence that women's language exhibits greater overall emotionality than men's (Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien2019; Jones Reference Jones2016). Third, and more specifically, women have been found to use more positive emotion, such as expressing happiness, in their political speeches than men (Boussalis et al. Reference Boussalis2021; Yu Reference Yu2013).

We identified five ‘agentic’ characteristics of style that are typically associated with men. First, men are thought to rely more on fact-based language, which is more ‘analytical, organised and impersonal’, and relies more on statistical evidence (Jamieson Reference Jamieson1988, 76). In the UK, MPs suggest that male politicians pay greater attention to ‘scientific research’ (Childs Reference Childs2004, 181), though in other settings, there is evidence that women may use more factual language (Hargrave and Langengen Reference Hargrave and Langengen2020).

Second, male politicians' speech is also thought to feature higher levels of linguistic complexity, marked by formalistic and jargonistic word use (Childs Reference Childs2004), while women are thought to be more accessible and clear (Coates Reference Coates2015). “Men are also thought to be, third, more repetitive (Childs Reference Childs2004, 184; Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup1988).” Fourth, men are said to be more aggressive, whereas women are said to avoid combative and aggressive styles (Brescoll and Uhlmann Reference Brescoll and Uhlmann2008; Kathlene Reference Kathlene1994), and empirical work suggests that women are significantly less adversarial than men in parliamentary debate (Grey Reference Grey2002; Hargrave and Langengen Reference Hargrave and Langengen2020). Fifth, women are thought to avoid the use of excess negative emotion for fear of backlash (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018), while men are thought to make greater use of negativity (Brooks Reference Brooks2011).

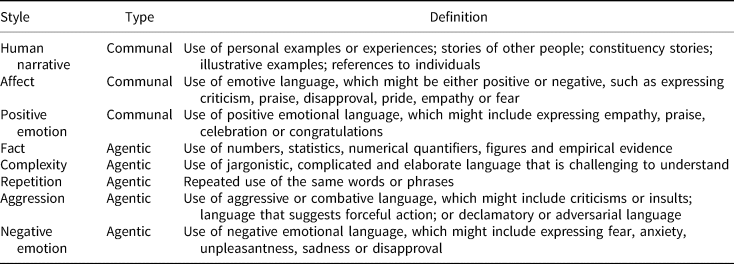

We summarise these eight styles in Table 1. We provide a short definition and categorise each as either ‘communal’ or ‘agentic’ according to our preceding discussion. The expectations that derive from the literature on gendered stereotypes suggests that women will be more likely to use communal debating styles and men are more likely to use agentic debating styles.

Table 1. Political styles

Dynamic Gender Stereotypes

Despite this rich literature, few studies consider whether politicians' conformity with gender stereotypes has changed over time.Footnote 2 This is surprising, as gender-role theorists emphasise that the content and strength of stereotypes are dynamic (Diekman and Eagly Reference Diekman and Eagly2000; Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly and Wood2012). These accounts posit that gender stereotypes arise from men and women's historical occupation of different social roles that are associated with different characteristics. For instance, because women have traditionally occupied roles in which they provide care to others, ‘caring’ as a characteristic became stereotypical of women. However, as the distribution of men and women into different roles changes, so too will the characteristics associated with the stereotypes themselves, such that the stereotype of women will be marked by ‘increasing masculinity and … decreasing femininity’ (Diekman and Eagly Reference Diekman and Eagly2000, 1,173). Building on this logic, we argue that recent changes in the roles played by women in both politics and the broader public are likely to have weakened traditional gender stereotypes in the UK, and we therefore expect a decline in the degree to which MPs, and especially women, will adopt styles that are congruent with the stereotypes described earlier.

First, politicians are selected from a broader population that has itself diverged from gender-stereotypical behaviours over time. In most advanced economies in recent decades, women's traditional role as caregivers has declined and women's educational attainment, participation in the workforce and occupancy of senior management positions have increased (Diekman and Goodfriend Reference Diekman and Goodfriend2006, 370; Sayer, Bianchi and Robinson Reference Sayer, Bianchi and Robinson2004). As societal gender roles have changed, women in the public have come to demonstrate increasingly agentic behaviours across a wide set of contexts and countries (Leaper and Ayres Reference Leaper and Ayres2007, 357; Twenge Reference Twenge2001). As politicians are likely to reflect the characteristics of the population from which they are drawn, if women in the UK are now more agentic on average, we should expect these changes to be reflected in the behaviour of politicians too.

Second, changing social roles have affected public perceptions of the validity of traditional gender stereotypes. Women in general are perceived as more agentic now than in the past (Eagly et al. Reference Eagly2020; Sendén et al. Reference Sendén2019), and while attributes associated with men have remained relatively stable, masculine characteristics are increasingly ascribed to women (Diekman and Eagly Reference Diekman and Eagly2000). Do changes in attitudes regarding the content and validity of stereotypes mean that voters are less likely to punish counter-stereotypical behaviours? As we reported earlier, several studies document voters' tendency to punish female candidates for displaying agentic traits. However, we are not aware of any existing empirical literature that tracks the extent to which politicians are punished by voters for contravening stereotypes over time. Several more recent studies suggest that voters do not always punish female politicians for violating feminine stereotypes (Brooks Reference Brooks2011; de Geus et al. Reference De Geus2021; Saha and Weeks Reference Saha and Weeks2020), but these studies again only provide evidence from a single point in time.

There is, however, evidence that the public have become less likely to endorse traditional gender stereotypes over time. As women's position in the labour market has improved, support for traditional gender norms and associated stereotypes has eroded, both in the UK and further afield (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2003; Seguino Reference Seguino2007; Twenge Reference Twenge1997). In the UK, voters have come to hold substantially more gender-egalitarian attitudes from the mid-1980s to the present (Taylor and Scott Reference Taylor and Scott2018). Further, between 1990 and 2010, voters in Western Europe, including in the UK, have become significantly less likely to agree with the traditional division of social roles performed by men and women (Shorrocks Reference Shorrocks2018). This latter finding is particularly relevant given that it is the association of men and women with particular social roles that is at the heart of theories of gender stereotypes (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). It therefore seems likely that as voters have become less willing to endorse gender stereotypes, they will also apply fewer sanctions to politicians who transgress such stereotypes. Consequently, as Mo (Reference Mo2015, 360) argues, ‘gender attitudes in the electoral process remain consequential, but have grown subtler’. To the extent that politicians in the UK are sensitive to the expectations of voters, then, changing voter attitudes about stereotypes will likely have reduced pressures on female politicians to conform to gender-stereotypical behaviours over time.

Third, the dramatic shifts in the roles that women play in political life in recent decades might also reduce the degree to which female politicians conform to traditional gender stereotypes. In the House of Commons, women held just 18 per cent of seats in 1997, but this had increased to 32 per cent by 2019 (IPU, 2020). Moreover, female politicians in the UK now occupy more high-powered positions within the legislative hierarchy (Blumenau Reference Blumenau2021). As women enter politics at a higher rate, role theory predicts that female politicians will come to be seen as possessing more masculine characteristics (Diekman et al. Reference Diekman2005), and the increasing prevalence of women in leadership has been shown to reduce the degree to which communal qualities are ascribed to women (Dasgupta and Asgari Reference Dasgupta and Asgari2004). As Diekman et al. (Reference Diekman2005, 212) argue: ‘women's increased representation as elected officials and government employees should foster the ascription to women of traditionally masculine qualities’.

Accordingly, in addition to a general tendency over recent years for the stereotypes of women to have become more oriented towards agentic characteristics, female politicians specifically may have become associated with more masculine characteristics over time as they have become more numerous and more powerful in the (historically male) political domain. These shifts in the political sphere might help to further reduce voter sanctions against female politicians who adopt agentic styles, but they are also likely to reduce the degree to which women in Parliament internalise expectations of feminine behaviour. In other words, as female politicians witness more examples of women in politics adopting more agentic and less communal styles, this may weaken the self-imposed standards of femininity that are typically seen as the internal drivers of stereotype-consistent behaviour (Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly and Wood2012). As female politicians become increasingly associated with forms of behaviour normally ascribed to men, the incentives for them to conform to more traditional feminine styles should be expected to decrease.

In our empirical analysis, we do not attempt to disentangle which of the three mechanisms outlined here, or others, may be responsible for changes in parliamentary behaviour. Rather, we aim to test a central prediction that emerges from our discussion of dynamic gender stereotypes: that MPs will conform less to gender-stereotypical styles in recent years than was true in the past; and that women in particular will be more likely to adopt agentic rather than communal styles over time.

Pressures to Conform to Institutional Behavioural Norms

In this section, we contrast the predictions of our argument with expectations generated by theories of feminist institutionalism. These perspectives hold that, as historically male-dominated institutions, legislatures are gendered spaces that maintain, favour and recreate traditional masculine behaviours (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003; Krook and Mackay Reference Krook and Mackay2011). While work in this literature does not always articulate clear predictions regarding the dynamics of gendered behaviour over time, implicit in these arguments is the idea that the pressure for women to conform to the prevailing (male) institutional style will be strongest when women are more marginalised in the legislature. When this is the case, as Franceschet (Reference Franceschet, Krook and Mackay2011, 66) argues, ‘women may respond by disavowing distinctly feminine (and feminist) concerns, instead favouring the style and substantive issues of the dominant group’. By contrast, as women gain higher levels of representation and more political power, the culture of the legislature will change to be more ‘conducive to women acting in a feminized way’ (Childs Reference Childs2004, 187).

The implication of this argument in our setting is that the pressure on women to conform to the dominant ‘masculine’ institutional style will be strongest at the beginning of our study period (in the late 1990s), when women's representation in the House of Commons was at lower levels, but that it should weaken over time. In addition to the increasing number of women in Parliament and in leadership positions, during the period we study (from 1997 to 2019), the House of Commons also introduced a series of reforms designed to strengthen the position of women within the legislature.Footnote 3 Therefore, while the House of Commons remains majority male, institutionalist perspectives predict that changes in composition and working practices will mean that women will be better able to ‘perform their tasks as politicians the way they individually prefer’ (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006, 519). Therefore, while our argument suggests that women are likely to respond to changing gender stereotypes by adopting more agentic styles over time, the institutionalist argument suggests that women are likely to adopt increasingly communal styles as they become more numerous and powerful in Parliament. The empirical strategy we outline in the following allows us to adjudicate between these contrasting predictions.

Data and Methodology

We consider the words of politicians' speeches as the primary locus of debating style, and we use texts of political speeches delivered in Parliament to infer the styles adopted by different speakers. Parliamentary speech is a useful source of information for measuring style, as it provides long-running panel data at the individual level. In the UK, MPs are afforded a large degree of autonomy regarding the debates to which they contribute, and party leaders exert no control over who participates, nor over the content of speeches that MPs deliver.

We study House of Commons debates between May 1997 and March 2019. Our study period is motivated by the fact that prior to the 1997 election, women accounted for less than 10 per cent of MPs, and so analysis of earlier periods would likely be sensitive to the styles of only a few specific women. We collapse our data such that all speeches made by an MP in a debate constitute a single speech document, making our unit of analysis an individual MP in a debate. We remove all speech documents shorter than 50 words, as well as contributions by the Speaker of the House, whose speeches are almost entirely procedural. We also exclude any debate that has fewer than five participants.Footnote 4 Our final sample consists of 14,864 debates, 1,422 MPs (370 female; 1,052 male) and 418,147 MP-debate observations.

Measuring ‘Style’ with Context-Specific Dictionaries

A common approach to measuring latent concepts, such as style, in text data is to assign each text a score based on a predefined dictionary that aims to capture the concept of interest. However, dictionary-based approaches are highly domain specific, as the words used to capture a concept in one context – say, parliamentary speeches – are likely to be different to those used to express the same concept in another context. We propose an alternative approach that combines standard dictionaries with a locally trained word-embedding model to construct domain-specific dictionaries that are better able to capture our style types as they manifest in the context of parliamentary debate. The key advantage of our approach is that it allows us to account for context-specific patterns of word use. In other words, rather than simply using an off-the-shelf dictionary that may be poorly suited to capturing, for instance, aggression in the parliamentary setting, this approach allows us to automatically create a bespoke aggression dictionary that is firmly rooted in the way that vocabulary is used in parliamentary debate. We use this approach to measure six of our styles: aggression, affect, positive emotion, negative emotion, fact and human narrative.

For each style, we follow three steps to construct the relevant score for each speech. First, we define a ‘seed’ dictionary that represents our concept of interest. For four styles (affect, negative emotion, positive emotion and fact), we use existing dictionaries, and for two styles (aggression and human narrative), we create our own seed dictionaries based on a close reading of a sample of parliamentary texts.Footnote 5

Second, we estimate a set of word embeddings using the Global Vectors for Word Representation (GloVe) model described by Pennington, Socher and Manning (Reference Pennington, Socher and Manning2014). Word-embedding models rely on the idea that words which are used in similar contexts will have similar meanings, and the embedding model allows us to learn the semantic meaning of each word directly from how the word is used by MPs in debate. We train the embedding model on the full set of parliamentary speeches, and the main output of the model is the set of word embeddings themselves. These are dense vectors that correspond to each unique word in the corpus, the dimensions of which capture the semantic ‘meanings’ of the words. Crucially for our purposes, the distances between word vectors have been shown to effectively capture important semantic similarities between different words (Mikolov et al. Reference Mikolov2013).

By calculating the cosine similarity between every word in the corpus and the words in each of our seed dictionaries, we can therefore use this property to define the set of words that, in the specific context of parliamentary debate, are used in a semantically similar fashion to the seed words. We label this quantity as ![]() $Sim_w^s $, where w indexes words and s indexes each style. Words closely related to the average semantic meaning of the seed words for a given dictionary will have a high similarity score (close to 1), and words that are less closely related will have a low similarity score (close to 0). The

$Sim_w^s $, where w indexes words and s indexes each style. Words closely related to the average semantic meaning of the seed words for a given dictionary will have a high similarity score (close to 1), and words that are less closely related will have a low similarity score (close to 0). The ![]() $Sim_w^s $ scores therefore define a domain-specific dictionary for a given style type. They describe the degree to which each unique word in our corpus is used similarly to the ways in which the words in our seed dictionary are used, on average. In essence, the embeddings enable our seed dictionaries to automatically expand to incorporate words that are used in a similar manner to the words that they already include. We provide full details of our approach, as well as an extensive set of validation checks, in the Online Appendix.

$Sim_w^s $ scores therefore define a domain-specific dictionary for a given style type. They describe the degree to which each unique word in our corpus is used similarly to the ways in which the words in our seed dictionary are used, on average. In essence, the embeddings enable our seed dictionaries to automatically expand to incorporate words that are used in a similar manner to the words that they already include. We provide full details of our approach, as well as an extensive set of validation checks, in the Online Appendix.

Third, we use the word-level scores, ![]() $Sim_w^s $, to score each sentence in the corpus on each style according to the words they contain. In particular, the score for a given sentence on a given style is:

$Sim_w^s $, to score each sentence in the corpus on each style according to the words they contain. In particular, the score for a given sentence on a given style is:

$$Score_i^s = \displaystyle{{\sum\nolimits_w^W S im_w^s N_{wi}} \over {\sum\nolimits_w^W {N_{wi}} }}$$

$$Score_i^s = \displaystyle{{\sum\nolimits_w^W S im_w^s N_{wi}} \over {\sum\nolimits_w^W {N_{wi}} }}$$ where ![]() $Sim_w^s $ is the similarity score defined earlier and N wi is the (weighted) number of times that word w appears in sentence i, where the weights are term-frequency inverse-document-frequency weights.Footnote 6 When words with high scores for a given style appear frequently in a given sentence, the sentence will be scored as highly relevant to the style. The score for each document is then the weighted average of the relevant sentence-level scores, where the weights are equal to the number of words in each sentence.

$Sim_w^s $ is the similarity score defined earlier and N wi is the (weighted) number of times that word w appears in sentence i, where the weights are term-frequency inverse-document-frequency weights.Footnote 6 When words with high scores for a given style appear frequently in a given sentence, the sentence will be scored as highly relevant to the style. The score for each document is then the weighted average of the relevant sentence-level scores, where the weights are equal to the number of words in each sentence.

The approach we outline here is similar to that developed by Rice and Zorn (Reference Rice and Zorn2021), who also use a word-embedding model to create context-specific dictionaries. We build on this work by addressing the question of whether word-embedding dictionary construction yields ‘valid dictionaries for widely-varying types of specialised vocabularies’ (Rice and Zorn Reference Rice and Zorn2021, 34). We extend the idea of word-embedding-based dictionaries to a new setting – the UK House of Commons – and to six new specialised vocabularies. As our validation exercises in the Online Appendix show, there is strong evidence that our approach significantly outperforms standard dictionary approaches across the set of styles we study.

Measuring ‘Complexity’ and ‘Repetition’

For our final two styles – complexity and repetition – dictionary approaches (domain specific or otherwise) are unsuitable, as these styles are not detectable from the occurrence of specific words. Instead, we adopt two different metrics to capture these concepts. For complexity, we use the Flesch–Kincaid Readability Score (Kincaid et al. Reference Kincaid1975). The intuition behind this measure is that documents which have fewer words per sentence and fewer syllables per word are easier to understand (more ‘readable’). We rescale the original formulation of the score such that higher numbers indicate higher levels of complexity. While Benoit, Munger and Spirling (Reference Benoit, Munger and Spirling2020, 501) show that domain-specific measures of textual complexity have some performance gains over the Flesch–Kincaid score, they also demonstrate that this metric correlates highly with more sophisticated measures. We opt for the simpler metric here because our own validation demonstrates that this measure performs well in comparisons with human judgements in our setting.

We consider MPs to be repetitive when they use the same language repeatedly during a debate. To measure repetition, we use a lossless text-compression algorithm introduced by Ziv and Lempel (Reference Ziv and Lempel1977), which underpins a variety of common computer applications. Compression algorithms work by finding repeated sequences of text and using those patterns to reduce the overall size of the input document. The efficiency of the compression of a text is directly related to the number and length of the repeated sections in that text. We apply the compression algorithm to every document in our corpus, measure the degree of compression and treat that quantity as the measure of repetition for each MP in each debate. Simply put, the more compression that a speech receives, the more repetitive we deem it to be.Footnote 7

Finally, to put our eight style measures on comparable scales, we normalise each measure across documents to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. This means that average differences for each style between men and women can be interpreted in standard deviations of the outcome variable.

In the Online Appendix, we provide extensive validation of our measures. In addition to a wide range of face-validity checks, we provide results from a task that assesses whether our measures mirror human codings of the same concepts. The results are very encouraging: across all styles, the correlation between our text-based scores and human judgements is always strongly positive, indicating that we are able to reliably detect our styles of interest in parliamentary speech. In addition, our word-embedding measures clearly predict human codings more strongly than do measures based on standard dictionary approaches, which have been used in previous studies on gender and political style.Footnote 8

Modelling Political Style

Our goal is to assess the degree to which style use varies by MP gender and whether such differences change over time. To investigate these patterns, we adopt a Bayesian dynamic hierarchical model that allows us to account for a wide variety of both individual- and topic-level confounders (described later), while also flexibly estimating changing gender dynamics in style over time.

For each speech i, we have a continuous measurement of style s, which we denote as ![]() $y_i^s $. For speech i, by MP j, in debate d and in time period t, we model the data as a function of individual- and debate-level parameters:

$y_i^s $. For speech i, by MP j, in debate d and in time period t, we model the data as a function of individual- and debate-level parameters:

where α j,t is an MP-specific random effect that captures average differences in MP style use. The t subscript indicates that we fit one intercept for each MP in each time period that they appear in the data, thus allowing us to capture average style use at different points in time. We use parliamentary sessions as our unit of time, of which there were 20 between 1997 and 2019. We observe speeches from an average of 635 MPs in each session, and each MP appears in nine sessions on average. The δ d parameters are random effects that capture average differences in style use in different debates.

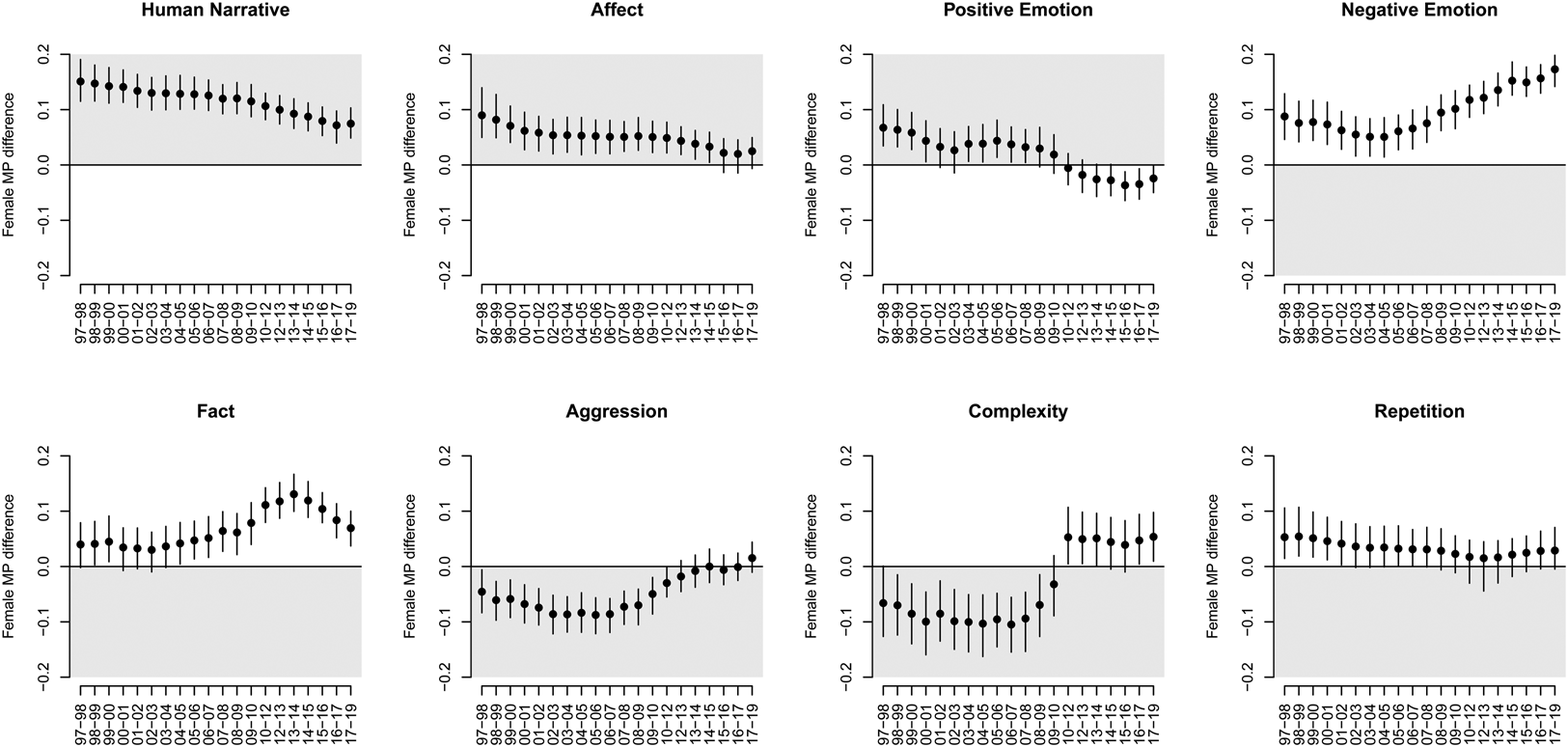

Our primary interest is in describing variation in the α j,t parameters. We model these random effects at the second level of the model as a function of MP gender, while allowing the relationship between gender and style use to vary over time:

where μ 0,t represents the average use of a style among male MPs in time period t, and μ 1,t describes the average difference in style use for women relative to men, again, in time period t. The standard deviation, ![]() $\sigma _\alpha $, describes how much, on average, the MP-session intercepts vary around the mean style use for MPs of each gender.Footnote 9 Gender differences in one parliamentary session are not independent of those in previous sessions, and in order to reflect a more realistic evolution of these differences, we model the μ 0,t and μ 1,t parameters as a first-order random-walk process:

$\sigma _\alpha $, describes how much, on average, the MP-session intercepts vary around the mean style use for MPs of each gender.Footnote 9 Gender differences in one parliamentary session are not independent of those in previous sessions, and in order to reflect a more realistic evolution of these differences, we model the μ 0,t and μ 1,t parameters as a first-order random-walk process:

$$\eqalign{& \mu _{0, t}\sim N( \mu _{0, t-1}, \;\sigma _{\mu _0}) \cr & \mu _{1, t}\sim N( \mu _{1, t-1}, \;\sigma _{\mu _1}) } $$

$$\eqalign{& \mu _{0, t}\sim N( \mu _{0, t-1}, \;\sigma _{\mu _0}) \cr & \mu _{1, t}\sim N( \mu _{1, t-1}, \;\sigma _{\mu _1}) } $$This specification assumes that the average use of a style by women and men will be similar in t and t + 1, and that changes over time will therefore occur gradually. This encourages smooth coefficient changes over time but still allows for large deviations from one period to the next if the information from the data is sufficiently strong.

The μ 0,t and μ 1,t parameters are our main quantities of interest. Here, μ 1,t captures the difference in average style use between genders in each time period, and our review of the theoretical literature implies general expectations for the sign of μ 1,t for each style (see Table 1). Consistent with our theoretical discussion of how the incentives for conforming with gender stereotypes have changed over recent years, we also expect the magnitude of μ 1,t for each style to decrease over time and for those changes to be driven mostly by changes to the average behaviour of female MPs (which, for each year t, is captured by μ 0,t + μ 1,t). We report both quantities in the following.

Our model allows us to account for individual-level confounders by including a set of MP-specific covariates in the model. To do so, in some specifications, we replace Equation 3 with:

$$\alpha _{\,j, t}\sim N( \mu _{0, t} + \mu _{1, t}Female_j + \sum\limits_{k = 1}^k {\lambda _k} X_{\,j, t}^k , \;\sigma _\alpha ) $$

$$\alpha _{\,j, t}\sim N( \mu _{0, t} + \mu _{1, t}Female_j + \sum\limits_{k = 1}^k {\lambda _k} X_{\,j, t}^k , \;\sigma _\alpha ) $$where X j,t is a vector of individual-level covariates that can vary by session.Footnote 10

We include several such controls. First, MPs in leadership positions may use systematically different styles than backbench MPs, and women came to occupy a greater share of legislative leadership roles over our study period (Blumenau Reference Blumenau2021). We therefore control for whether the MP held a frontbench position for either the government or opposition in each session, as well as whether they were a committee chair.

Second, if MPs from different parties use styles at different rates, then any change we observe in the gendered use of styles might be confounded by the fact that proportionally more Conservative Party female MPs have been elected to Parliament in recent years. We therefore also include a set of party dummies.

Third, opposition MPs use significantly more negative language than government MPs (Proksch et al. Reference Proksch2019), and because the Labour Party has proportionally more women than other parties, any increase in women's use of more agentic styles might be attributable to Labour's move into opposition in 2010. To address this possibility, we control for whether an MP is a member of a governing or an opposition party in each time period.

Fourth, we also add controls for MPs' occupational background and educational attainment. The professional and educational backgrounds of MPs have changed over time (Lamprinakou et al. Reference Lamprinakou2017), and it is plausible that these characteristics will be associated with both speechmaking styles and gender.

Finally, MPs' local electoral environment might affect language use. For instance, MPs in more competitive seats might be more likely to use human narrative to emphasise constituents' concerns. If there have been changes in the relative competitiveness of seats won by men and women over time, this could confound the differences we observe in gendered language use. We therefore control for the percentage-point margin of victory of the MP in the previous election.

We are also able to use our model to account for confounding that relates to the differential usage of styles across topics. Men and women systematically participate in debates devoted to different topics (Bäck and Debus Reference Bäck and Debus2019; Catalano Reference Catalano2009), and debate topic may correlate with style in ways that work to confound our inferences. For instance, if women participate more in debates on education that contain language related to human narrative, while men participate more in debates on the economy that include more factual language, then gender differences in topic usage will confound gender differences in style. However, the debate-level intercepts, δ d, mean that it is only within-debate variation in style use that informs the estimates of our central quantities of interest. In other words, μ 1,t will capture only the degree to which men and women use different styles when speaking about the same substantive topic. We estimate our model separately for each style in Stan (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter2017), where we use three chains of 500 iterations, after 250 iterations of burn-in.

Results

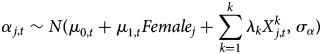

Figure 1 shows the values of μ 1,t – the average difference between men and women for each style type in each parliamentary session. Positive values indicate that a style is used more by women, and negative values indicate higher use of the style by men. The grey shading indicates the expected direction of the gender effects based on previous literature (see Table 1).

Fig. 1. Gender differences in style over time.

For five of the debating styles we study, we find that in the early years of our sample, male and female speechmaking behaviour broadly conforms to stereotypes. Female MPs are more likely to draw on examples that emphasise human narrative and to use positive and emotional language than men. Similarly, men use more aggressive and complex language, at least before 2010. Interestingly, for three of our styles – fact, repetition and negative emotion – we find that debating style in the House of Commons does not clearly conform to the expectations of the existing literature. For all three of these agentic styles, for much of the period we study, female MPs are more likely than male MPs to express these styles.

However, and in some sense more importantly, Figure 1 also reveals that there is significant variation in the size of these gender differences over time. Women are more likely to use ‘communal’ style types – affect, positive emotion and human narrative – in the early period in our data, but gender differences become smaller over time. For positive emotion and affect, there is no consistent significant difference between men and women by the latest years in our data. Similarly, while men use significantly more ‘agentic’ styles – particularly aggressive and complex language – than women before 2010, this difference has also disappeared in recent years. These changes are non-trivial: for those styles where we see a convergence between men and women, the proportion of MP-level variation in style use explained by gender decreases by between 30 per cent and 60 per cent, depending on the style, when comparing the periods before and after 2007.Footnote 11

Further, for other styles, we observe increasing gender differences over time, but the direction of these shifts also suggest that women are becoming increasingly agentic relative to men. For instance, although there are negligible gender differences in the earlier period, from 2007 onward, women use significantly more factual language. Similarly, although women use negative emotion in their speeches at higher rates throughout the time period, this gender difference has grown substantially larger over time. Between 1997 and 2007, gender explained just 0.6 per cent and 2 per cent of MP-level variation in factual language and negative emotion, respectively, but this increased to approximately 4 per cent and 9 per cent after 2007. Accordingly, even for these agentic styles that women adopt more than men throughout the study period, it remains the case that women become more likely to deploy this type of language in recent years than in the past. The only style for which we document relatively stable gender differences is repetition. While women appear to have become somewhat less repetitious relative to men over time, the trend for this style is less pronounced.

Taken together, these findings are consistent with our argument that the pressures for women to conform to stereotypes have declined over time. In general, relative to men, women demonstrate less communal (human narrative, affect and positive emotion) and more agentic (negative emotion, aggression, fact and complexity) styles in recent years than they did in the past.

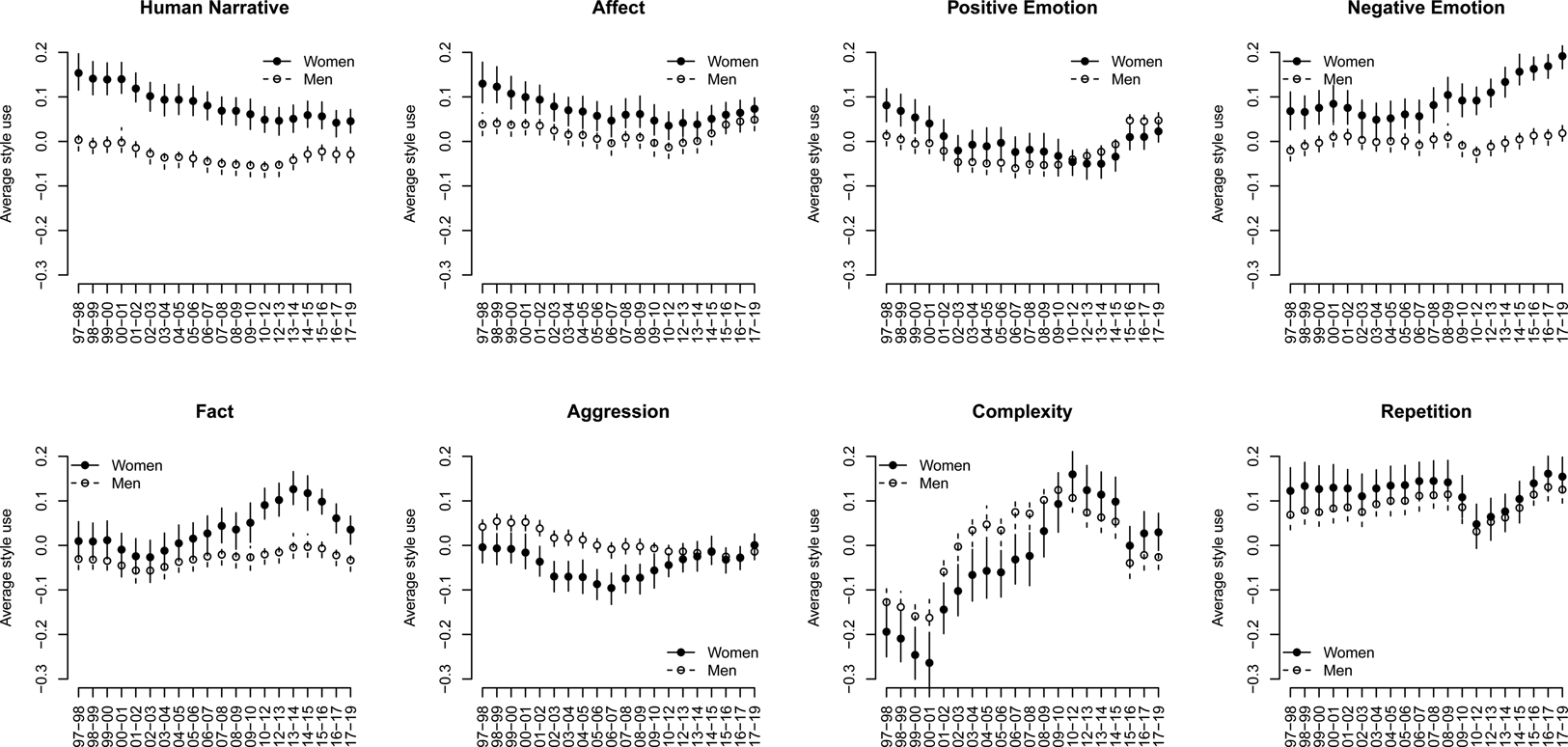

Are these patterns the result of changes in the behaviour of male or female MPs? Our argument implied that these changes were likely to be rooted in the behaviour of women as they respond to the changing content and power of gender stereotypes. Figure 2, which depicts changes in style use separately for women and men, shows that across almost all the styles we study, the largest year-to-year shifts in speechmaking behaviour do indeed occur among women. Figure 2 shows that women have used each of our communal style types – human narrative, affect and positive emotion – to a decreasing extent over time. Similarly, for the ‘agentic’ styles of negative emotion, fact and aggression, while men's behaviour has remained relatively stable, women's use of these styles has increased over time. While both men and women have adopted more complex language over time, the increase has been somewhat larger for women than for men.

Fig. 2. Average style use for men and women over time.

Threats to Inference

We have argued that politicians' conformity to traditional stereotypes has diminished over time, but there are alternative explanations that could account for the behavioural patterns we document. First, as we outlined earlier, the literature on feminist institutionalism suggests that women will face pressures to conform to institutionally dominant, masculine behaviours that are favoured and recreated by the culture of the House of Commons. While institutional pressures of this sort are surely a feature of life in the contemporary House of Commons, for this perspective to explain our results, these pressures would need to have strengthened in recent years. However, during this period, women's presence increased in the House of Commons, female MPs came to hold more senior positions and institutional reforms designed to strengthen women's institutional position were introduced. Consequently, if women face stronger incentives to conform to masculine styles when an institution is more male dominated, then we should observe women becoming less agentic over time. Our results show the opposite pattern, suggesting that institutionalist accounts are unlikely to explain the over-time dynamics in speechmaking that we document.

Second, Figures S4 and S5 in the Online Appendix report results from the model described in Equation 5, in which we control for a host of MP-level covariates. If the changes we observe over time are driven by factors such as party, opposition status and so on, we would expect to see large differences between these two sets of results. Although there is some attenuation of the over-time changes for aggression and complexity when controlling for covariates, we nonetheless still observe stereotype-consistent differences at the beginning of the sample period and clear evidence of women using more agentic styles over time.

Third, the aggregate patterns we document could reflect changes to the parliamentary agenda, rather than changes in gendered behaviour. If there are certain topics on which women are more likely to demonstrate agentic styles and these topics feature more prominently on the parliamentary agenda in the later period, then our results might be explained by changing topical prevalence over time. In the Online Appendix, we use statistical topic models to measure the differences between male and female style use across a wide variety of topics, and then evaluate whether topics that are marked by large stylistic differences become more or less prevalent over time relative to topics marked by smaller differences. We find scant evidence of such topical confounding.

Finally, in the Online Appendix, we also assess whether women with more agentic styles participate more, and women with more communal styles participate less, in parliamentary debate over time. We show that differential participation does not explain our results: MPs' styles largely fail to predict debate participation throughout our study period. In addition, we also investigate whether the changes we document are due to changes in the styles of men and women throughout their careers (‘within-MP’ effects), or because the men and women entering Parliament over time are systematically different from those leaving (‘replacement’ effects). While there is some evidence that replacement is more important for explaining the changes in agentic styles and within-MP change is somewhat more important for explaining change in communal styles, overall, we find that neither replacement nor within-MP change can alone explain the patterns that we documented earlier.

Conclusion

Our central substantive contribution is to document the fact that gender stereotypes are worse descriptors for actual political behaviour in the UK now than was true in the past. In particular, in recent years, women in the House of Commons have demonstrated less communal and more agentic styles, and the gender gap on most dimensions of style that we examined has decreased. We see these results as an important corrective to the scholarly literature on gender differences in legislative behaviour, which typically emphasises that male and female politicians argue in ways that are broadly consistent with stereotypes. Although this may be true in some settings, gender stereotypes of communication styles have become significantly less predictive of the reality of contemporary British political debate.

These findings do not, however, imply that gender stereotypes play no role in UK politics. We show that recent parliamentary behaviour is poorly described by traditional stereotypes, but we do not provide empirical evidence regarding the mechanisms that led to these changes. For instance, previous work shows that the public are less likely to endorse traditional stereotypes now than in the past, but we lack data to assess whether there has been a concomitant decline in the sanctions that voters apply for gender-role-inconsistent behaviour. Anecdotally, there continue to be examples of British female politicians being criticised for stereotype-incongruent behaviour,Footnote 12 and stereotypes may well continue to condition voter responses. Although we think this type of sanctioning is likely to have declined because of general changes in voter attitudes regarding stereotypes, future work should focus on collecting over-time survey data on voters' attitudes towards non-stereotypical behaviour by politicians.

One optimistic view of our findings, however, is that there may be a virtuous circle in which female politicians diverge from stereotypical behaviours and that this, in turn, changes perceptions of appropriate feminine behaviour, which thereby reduces the pressures women are under to conform to such stereotypes. Changes in the typical behaviours of male and female politicians are likely to translate only slowly into revised public expectations of the standards against which men and women MPs are judged. However, to the degree that the behavioural shifts that we document are noticed and internalised by the public, they might also help to reduce the social penalties applied to female politicians who display more agentic styles.

Our findings also have implications for wider debates about political culture in the UK. There is a strand of popular commentary which implies that some of the more unattractive features of Westminster's adversarial culture would be ameliorated if only more women were to be elected to public office. Our results suggest, however, that simply increasing women's numbers in Parliament is unlikely to make UK politics gentler or more deliberative. The pursuit of a ‘better’ politics requires more than vaguely hoping, on the basis of a dogged adherence to outdated gender stereotypes, that the election of women will fundamentally change the ways that our representatives communicate.

Methodologically, our article addresses a well-known problem for quantitative text analysis based on dictionaries: the words that demonstrate a given concept in one context may be poorly suited to detecting the use of that concept in another context. We used a word-embedding model to capture how different political styles manifest in the specific setting of parliamentary debate. Results from our validation (in the Online Appendix) show that this approach significantly outperforms existing methods, a finding we believe justifies its adoption elsewhere. Our strategy is likely to be useful whenever researchers are interested in measuring a latent concept from a large corpus of texts but where the domain of interest differs from the domain in which existing dictionaries were developed. This describes a large fraction of applications of dictionary methods, and so our approach has the potential to be applied widely elsewhere.

Finally, we focus only on style as expressed in legislative debates. Style may, of course, manifest in other forms of legislative behaviour or, indeed, other forms of political speech. While we show that gender gaps in legislative speech have declined, it remains possible that gender stereotypes may still be powerful in other arenas, such as in campaign communication, where politicians may be particularly sensitive to voter penalties. We hope that our findings motivate other scholars to explore how gender-based differences in political communication have evolved over time in other contexts.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000648

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PPSFLT

Acknowledgements

We thank Lucy Barnes, Jennifer Hudson, Markus Kollberg, Tone Langengen, Ben Lauderdale, Rebecca McKee, Alice Moore, Tom O'Grady, Meg Russell, Jess Smith and Sigrid Weber for helpful conversations and insightful comments. We are also grateful to participants at working group seminars at University College London, Political Studies Association Political Methodology 2020 and the Empirical Study of Gender Research Network Summer Graduate Working Group 2020. Finally, we thank Agnes Magyar and Alicia O'Malley for excellent research assistance.

Financial Support

None.

Competing Interests

None.