Despite continuing advances in knowledge and technology, the interpersonal aspects of care can remain a daily conundrum for clinicians. It is not the problem of what treatment to prescribe for a patient, but how patients engage with this treatment, that complicates clinical reality. The solution to this lies beyond established diagnostic inventories and treatment protocols, in the exploration of healthcare professionals' clinical experiences through thinking and reflection.

Reflective practice is a tool that enables professionals to learn from their experiences, by critically appraising these in order to arrive at new insights (Dewey Reference Dewey1933; Boud Reference Boud, Keogh and Walker1985). This process offers the opportunity to think creatively about complex situations not easily understood within traditional frameworks (Schön Reference Schön2017; Lutz Reference Lutz, Roling and Berger2016). Reflective practice addresses the complexity of human behaviour in these cases that defy typical solutions (Moon Reference Moon2013). This mode of working underpins the true meaning of patient-centred care.

The benefits of reflective practice within healthcare are threefold. It assists in clinicians' understanding of their patients, their development as professionals (Boud Reference Boud1999; Neumann Reference Neumann, Edelhäuser and Tauschel2011; Lutz Reference Lutz, Scheffer and Edelhaeuser2013) and the healthy functioning of their teams and institutions (Lavender Reference Lavender2003; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson and Fagerberg2004; Gordon Reference Gordon, Kirtchuk and McAlister2017).

Examples of group-based reflection in common use include Balint groups and Schwarz rounds. Although these models have different primary aims and methods of working, their effectiveness is derived from common factors that promote group functioning. These include emotional safety and the avoidance of blame, judgement or shame (Williams Reference Williams and Walker2003; Sternlieb Reference Sternlieb2015). There are also numerous resources that exist to guide and support clinicians wishing to facilitate and implement group reflective practice in their place of work (Obholzer Reference Obholzer and Roberts1994; Bradley Reference Bradley and Rustin2008; Hartley Reference Hartley and Kennard2009; Shoenberg Reference Shoenberg and Yakeley2014).

Despite a growing recognition of the value of reflective practice groups in clinical care, the evidence base for their efficacy is limited. Most research remains observational in nature, and there is need for further quantitative studies into their influence on clinical behaviour and patient outcomes (Mann Reference Mann, Gordon and MacLeod2009; Van Roy Reference Van Roy, Vanheule and Inslegers2015).

The interpersonal dynamics consultation model and its use in medical settings

The interpersonal dynamics consultation model described in this article shares some similarities with other forms of reflective practice. However, unlike the Schwarz round and Balint group the consultation is held within the multidisciplinary clinical team, rather than along professional lines or in a grand round. Its format also lends itself to the creation of new solutions for a particular case. An interpersonal dynamics consultation uses a systematic approach to assess the perspectives of both staff and patients, with an emphasis on supporting evidence where relevant. The aim of the systematic approach is to reduce the clinical blind spots that can occur in analysis of an emotionally charged case and to distinguish what is expressed by the patient from that which is inferred by the clinicians.

Interpersonal dynamics consultations are commonly used in psychiatry, but they have less recognition in physical healthcare settings. Yet, just as in mental healthcare, it is often the human factors that impede successful management for medical teams. Clinical case discussions in medical teams are often focused solely on technical facts, ignoring the wider psychosocial context of the patient, and subject to the unwritten rules of who is authorised to speak in the meeting and who is not (Launer Reference Launer2016). This mode of treatment planning can overlook the vital relational (interpersonal) factors between the team and the patient that can hinder effective treatment.

Patients with psychiatric diagnoses can experience significant difficulties in physical healthcare settings. Not only is there a significantly higher level of physical morbidity among these individuals than in the general population, but they tend to experience worse treatment. There is a tendency for diagnostic overshadowing, subsequent delays in appropriate physical health treatments and higher complication rates (Nash Reference Nash2013). Stigmatisation and negative emotional reactions towards these patients occurs because of the time pressures, communication difficulties and lack of mental health training that medical staff are subject to (Van Nieuwenhuizen Reference Van Nieuwenhuizen, Henderson and Kassam2013; Shefer Reference Shefer, Henderson and Howard2014; Noblett Reference Noblett2017).

In addition to patients with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, general hospitals also treat a constellation of patients who suffer from psychosomatic illness, personality difficulties and historical trauma. This cohort tends to fall below the threshold for psychiatric referral, or refuse referral, but have significant behavioural difficulties and troubling patterns of engagement with healthcare services.

The project described in this article involves introducing the interpersonal dynamics consultation approach to reflective practice in medical teams in order to help them think about patients who are difficult to engage with. Funded by Health Education England, the project addresses the growing recognition of the importance of joint working at the mental and physical healthcare interface and also of the value of the translational work of making psychiatry and psychotherapeutic ideas more embedded and relevant in physical healthcare settings. Building on work previously presented in BJPsych Advances (Reiss Reference Reiss and Kirtchuk2009), this article describes the interpersonal dynamics consultation model and its new application in physical healthcare settings as illustrated by case vignettes.

The interpersonal dynamics consultation project

The interpersonal dynamics consultation uses a structured and systematic model to understand the transference and countertransference processes that occur within the patient–team interaction. The consultation offers a way of thinking about the repetitive and problematic relational patterns that might be at play in a patient's engagement with help. As well as enabling a form of reflective practice that helps the processing of difficult emotions and communication within a team, the consultation is designed to help clinicians think about and care for these patients.

The theoretical basis of the interpersonal dynamics model can be traced back to the psychoanalytic principles of Freud, through successive iterations by theorists such as Leary (Reference Leary1957), Benjamin (Reference Benjamin1996) and, most recently, the Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnostics (OPD) Task Force (2001, 2008). Drawing upon the work of the OPD Task Force, Kirtchuk, Reiss and Gordon in the Forensic Psychotherapy Department in West London created the interpersonal dynamics model used in this project. This model is based on the systematic appraisal of the four interpersonal perspectives that constitute the transference and countertransference processes that can occur between patient and staff (Gordon Reference Gordon and Kirtchuk2008; Reiss Reference Reiss and Kirtchuk2009). There is a clinical manual of the IDC approach (Kirtchuk Reference Kirtchuk, Gordon and McAlister2013).

The interpersonal dynamics consultation has been used successfully for many years in mental healthcare and especially in forensic psychiatry (Gordon Reference Gordon and Kirtchuk2008). Building on this previous work, the current project explores the application of the consultation within a physical healthcare setting.

This project has been running for 24 months and during this time has provided training in the interpersonal dynamics consultation to psychiatrists across various specialties. The training enables participants to facilitate interpersonal dynamics consultations in their own teams and to act as facilitators within medical teams in general hospitals. The project's facilitators have worked with a variety of medical specialties in several hospitals across London.

The interpersonal dynamics training spans four sessions, each lasting 3 h. It provides a useful model to assist in difficult cases and also offers psychiatrists an accessible psychotherapeutic tool that draws on their existing experience as clinicians. The training also offers participants an introduction to liaison work and can form the basis for launching a quality improvement project.

The consultation format is described below, along with three fictitious case vignettes that illustrate its application in medical settings.

How to conduct an interpersonal dynamics consultation

The consultation focuses on one particular patient case and should include as many members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) involved in the care of that patient as is practicable. A trained facilitator leads the consultation, which usually lasts between 60 and 75 min. The team may be offered a second session at a later date in order to revisit and follow up a particular case.

The rationale for inclusion of the whole MDT is that different members of the team tend to experience the patient in different ways, all of which when brought together can reveal a rich tapestry of the patient's relational patterns. For the patient, different members of an MDT can come to represent different figures or parts of the self. Owing to the splitting off of these different qualities, it is useful to gather up the perspective of the whole team.

Rather than the traditional hierarchies that exist in a typical team meeting, where senior members or certain professions tend to hold more authority to speak, the interpersonal dynamics facilitator will seek to create a ‘flattened’ hierarchy within the team in order that the perspective of each member is equally valid.

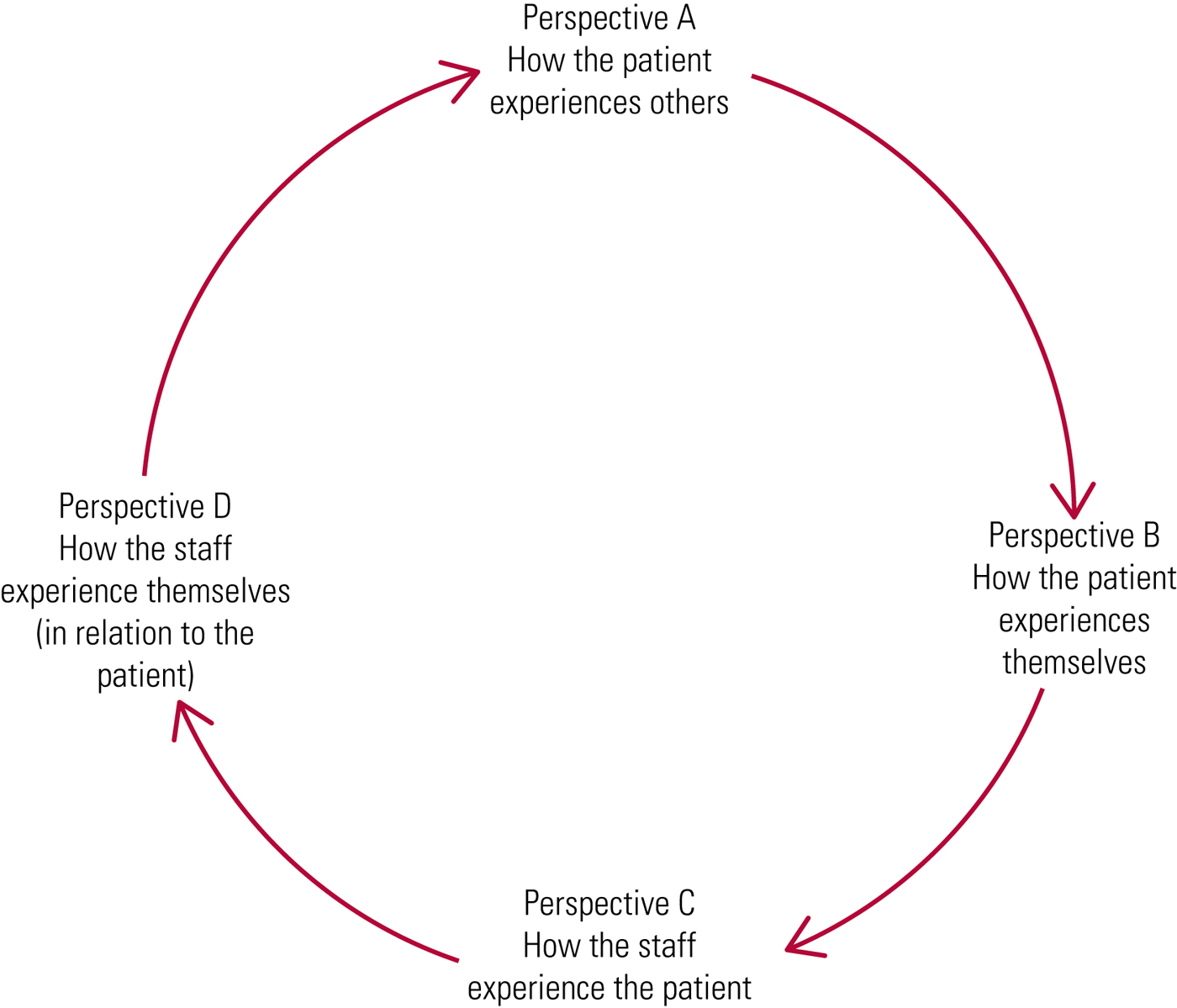

The meeting begins with the team describing the reasons for bringing this particular case to an interpersonal dynamics consultation and the questions that they seek to answer. The team are then asked to present the patient's background, with particular focus on childhood and significant relationships. By using the cluster items listed in Box 1 for guidance, the facilitator then takes the team through each of the four perspectives (Fig. 1) in turn, asking the participants to give their thoughts. For perspectives A and B, which pertain to the patient's experience, the team are also asked to back up their responses where possible with examples of the patient's actions or statements.

FIG 1 The four interpersonal perspectives.

After working through the four perspectives, the team are helped to synthesise a formulation describing how these perspectives may interrelate in a dysfunctional and repeating cycle (denoted by the arrows in Fig. 1) into which patients and staff are drawn. From here, an extended formulation brings in what is known about the patient's history. This allows exploration of how the patterns of relating forged from significant past relationships are being played out with the team members caring for them in the present.

The role of the facilitator within the consultation is to work not as an expert, but as someone who guides the team through the consultation. They facilitate an open discussion and ensure that all the separate perspectives are heard. The systematic approach and accessible framework allow the team to express their thoughts and emotions and to shift perspectives in order to ‘mentalise’ the world of the patient. It is through the discussion that the team arrive at their own insights and understanding of the patient, as well as fresh ideas for managing the case.

Case vignettes

During the course of the project there have been numerous fascinating cases from different medical specialties. The three fictitious case vignettes below, inspired by real-life consultations, illustrate the interpersonal dynamics consultation at work.

Case 1

Mr C is a 43-year-old male who was a patient under the bariatric team. Mr C is from Argentina and has been living in the UK since 1990; he lives with his long-term male partner. He is an only child in a wealthy family; his father was a diplomat and his mother was a housewife. He described his mother as benign and passive and his father as ‘absent’ while he was growing up. His father has not spoken to him since he came out to his parents about his sexuality in his early 20s. Mr C states that he had struggled to hide his sexuality for many years when growing up.

After his studies Mr C moved to the UK and began a successful career in the music industry. During this time he became addicted to cocaine and was admitted for in-patient rehabilitation on three occasions. He describes his drug use as being normal for the music industry and party scene. Mr C dieted as a teenager and started to binge and purge in his 20s; he gradually put on weight and became morbidly obese in his 30s.

Mr C presented to the team because of morbid obesity. He had received a gastric bypass 2 years ago and since this time he has had multiple complications and been admitted several times in recent months because of malnutrition with low albumin levels. Owing to the severity of these complications the team have recommended reversal surgery. Mr C refuses this, stating that he does not believe that it is required.

Mr C would behave in an overly familiar manner with the surgeons, often flattering them and joking with them, and they in turn would offer him extra appointments. He would refuse to speak to junior doctors or nurses. Mr C refused to have his partner attend the consultations and care planning meetings.

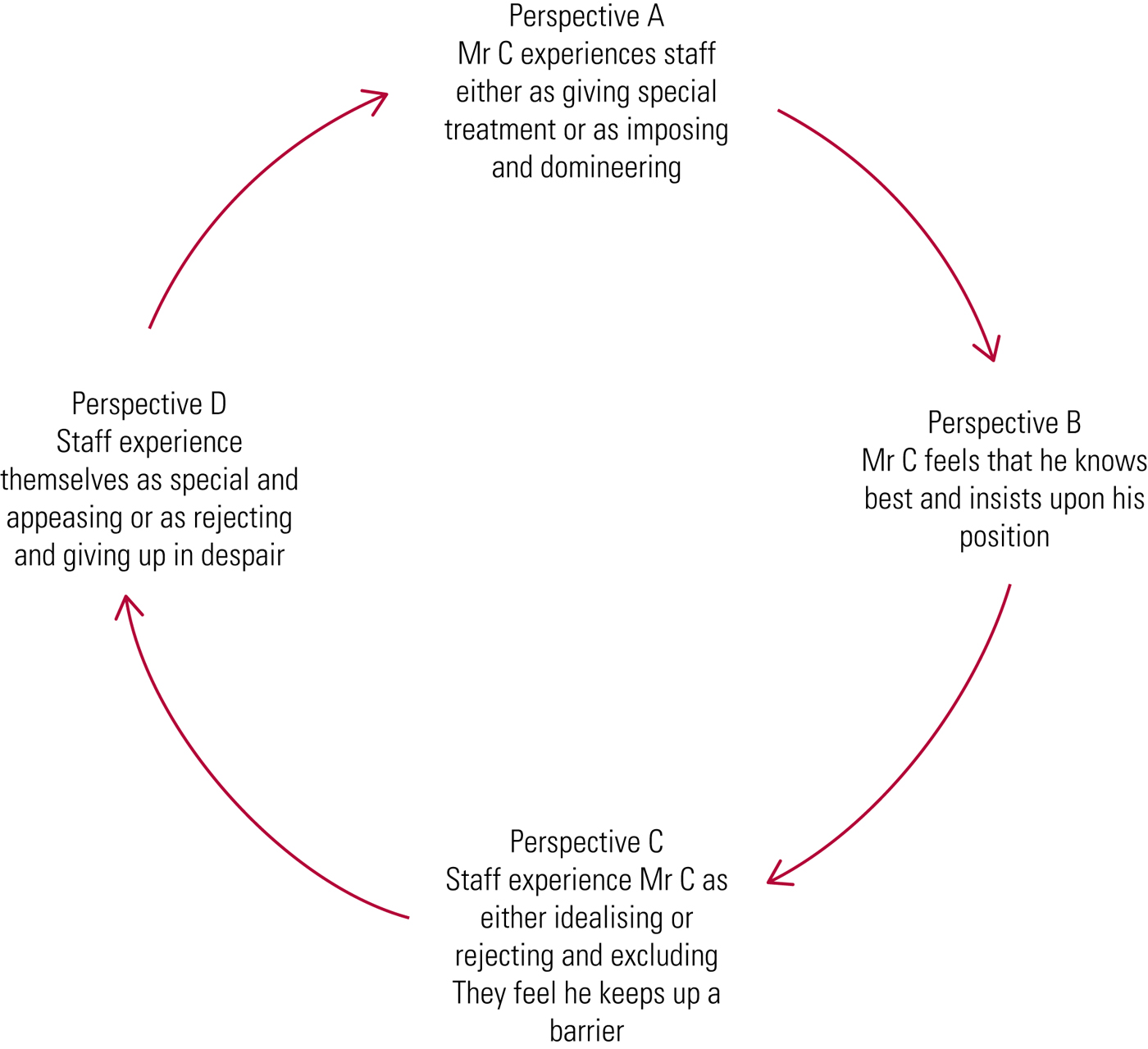

The team brought Mr C's case to an interpersonal dynamics consultation because they felt stuck and divided with respect to his treatment plan. On the basis of the background information outlined above and using the cluster items in Box 1, during the consultation the team described Mr C's interactions in the following way (Fig. 2).

BOX 1 List of cluster items for interpersonal perspectives

FIG 2 The dysfunctional cycle in case 1: Mr C.

Perspective A (how the patient experiences others):

• idealising and giving special treatment – senior clinicians would often offer Mr C extra appointments

• domineering and imposing – Mr C felt that members of the team were bullying him into having reversal surgery.

Perspective B (how the patient experiences themselves):

• requiring special treatment – Mr C talks a lot about his professional success and insists on being treated only by the senior staff

• insisting on his position – Mr C insists that he does not require the surgery

• the staff also admit to finding it difficult to imagine how Mr C really sees himself.

Perspective C (members of staff experience the patient as):

• idealising – he is overfamiliar and affectionate towards the surgeons

• rejecting and excluding – he interacts only with the consultants and ignores the other members of staff

• keeping up a barrier – staff feel that, however superficially charming Mr C is, it is impossible to get to know him.

Perspective D (members of staff experience themselves as):

• special and appeasing – some staff felt appreciated and in turn made special allowances for Mr C and found it hard to raise with him the dangerousness of his low albumin

• rejecting and giving up in despair – some staff wanted to discharge him from the service if he refused the offered treatment.

Formulation

The consultation highlighted the split that exists within the team. Some senior clinicians experienced Mr C as charming and affable and themselves as special. They wished to comply with his refusal of surgery. Some (more junior) members of the team experienced him as bullying and patronising and therefore wanted to get rid of him by discharging him. The team has become drawn into Mr C's either charming or domineering demeanour. During the consultation they came to see that this was in fact a defensive barrier that hides his underlying eating disorder, his psychological and physical needs. We can postulate that Mr C tended to emphasise his professional success, while the rejection by his father and his struggles with his sexuality, substance misuse and eating disorder remain glossed over. Growing up, the lack of understanding and acceptance by his parents was remedied by more superficial means. His self-value became oriented on wealth and success, his comfort derived from food and illicit drugs.

In conducting the consultation, the team realised the dangerousness of the situation and that making Mr C feel ‘special’ or appeasing him was not in his best interests. Mr C had an eating disorder that needed to be fully assessed, as it might undermine his capacity to make decisions about his treatment. They decided to involve the partner in all future planning meetings, and the consultation itself helped to address the splits within the team. Mr C subsequently consented to having a full reversal of the gastric bypass. He was referred to the eating disorder service but declined. The team eventually discharged him back to primary care.

Case 2

Ms A is a 46-year-old female who is a renal dialysis patient. Ms A is British, had a turbulent childhood and grew up in care. She experienced multiple placement breakdowns during her adolescence. She is unemployed and single.

Ms A attends the renal dialysis unit three times a week. She has type 1 diabetes and has been in end-stage renal failure for a number of years. She has been moved on from several dialysis units because they could not manage her challenging behaviour. Ms A would often be verbally abusive towards staff, especially if she was made to wait on arrival. She has poor levels of engagement with her renal team and poor adherence to dialysis. She often misses appointments, which puts her health at significant risk. She has a significant psychiatric history, including previous substance misuse and diagnoses of depression and borderline personality disorder. She also has poor engagement with psychiatric services and takes her antidepressants inconsistently. However, she was considered to have capacity to make decisions about her dialysis.

After a few months the current MDT began to feel that they could not cope and that they too would be unable to manage Ms A. Some were afraid of her aggressive behaviour, and others found themselves taking extra time to call her on a daily basis to remind her of her appointments. The team brought her case for an interpersonal dynamics consultation in order to help identify strategies to deal with Ms A's behaviour and create more consistent boundaries for her management.

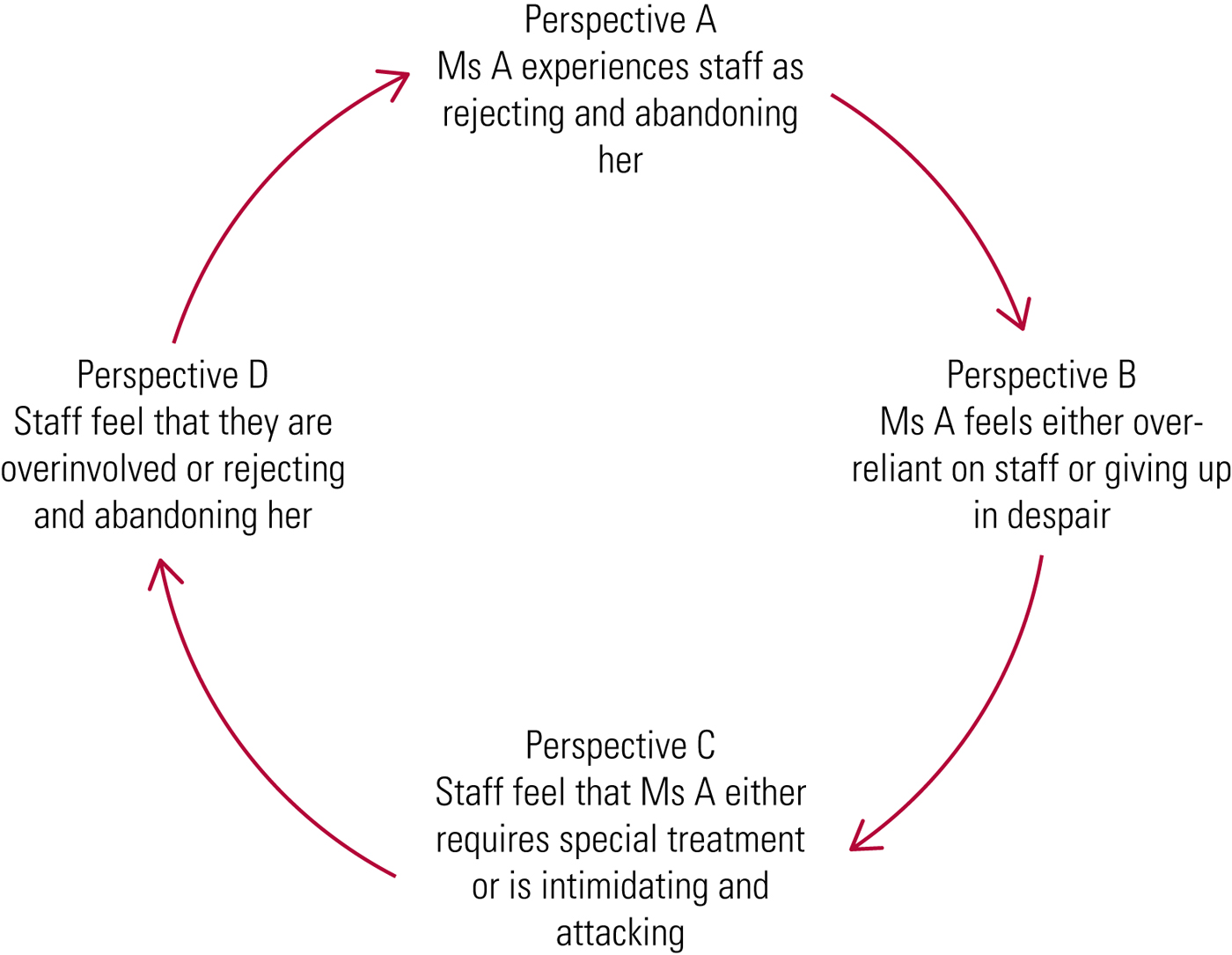

The team described Ms A's interactions in the following way (Fig. 3).

FIG 3 The dysfunctional cycle in case 2: Ms A.

Perspective A (how the patient experiences others):

• rejecting and abandoning – Ms A often demands to know why she is being made to wait and why other patients are being seen before her.

Perspective B (how the patient experiences themselves):

• giving up in despair – Ms A has stated ‘I don't want to die but I don't know how to change’

• overreliant – Ms A has expressed fear about being discharged from mental health and renal services.

Perspective C (members of staff experience the patient as):

• intimidating and attacking – Ms A often shouts and swears at staff

• requiring special treatment – staff feel that Ms A expects them to drop everything for her; they describe her as their most demanding patient; some resort to calling her every day to remind her of her appointments.

Perspective D (members of staff experience themselves as):

• overinvolved – staff stated that ‘If she dies it will be our fault – we have a duty of care’

• rejecting and abandoning – the consultants try to avoid Ms A by booking her into days when their colleagues are working; the staff have given her written warnings and try to avoid her when she arrives.

Formulation

The consultation and perspectives highlight a repeating cycle whereby Ms A lives in a state of fear of being abandoned by those around her, while simultaneously putting herself out of reach of help. This results in a repeated pattern where Ms A either demands special treatment or pushes people away with threats and intimidation. The team came to see that Ms A was testing them because of her underlying fear of abandonment. They realised that they had colluded with her tests, by becoming overinvolved or wishing to get rid of her.

Ms A's sensitivity to abandonment and rejection probably dates back to her turbulent childhood of being in foster care and experiencing multiple placement breakdowns. We can imagine that through these unstable childhood events Ms A has experienced a lot of abandonment and instability. This has resulted in a need for reassurance, which fuels her demand for special treatment. Just as in her adolescent years, she exhibits externalising and challenging behaviours that test boundaries and provoke others to abandon her; when they inevitably do, this self-fulfilling prophecy reaffirms her world-view.

As a result of the consultation the team came to realise that much of Ms A's behaviour serves to increase her contact with staff. They therefore tried to reassure Ms A that the unit would continue to care for her up until her death and they reinforced the fact that missing appointments would not result in discharge but it would further damage her health. After a discussion with Ms A they decided to limit the phone calls, as these did not affect her attendance or outcome. They were able to see that Ms A's death would not be ‘their fault’ and planned to create a consistent team around her that would include the community mental health team and in-patient unit.

Case 3

Mrs S is a 78-year-old female who is known to the community respiratory team. The youngest of five children, she grew up in a large family in an impoverished neighbourhood in Northern Ireland. She described her childhood as difficult owing to a lack of material and emotional support. She moved to England in her 20s, where she worked as a secretary and met her husband. They were happily married for almost 50 years, until he died 10 years ago. They did not have any children.

Mrs S lives alone but is very active in her community and spends most of her time gardening, socialising or involved in organising activities for the local Women's Institute meetings. She describes herself as having a ‘rigid routine’ of activities each day and has ‘no time for breathlessness or being ill’. Mrs S was diagnosed with emphysema 10 years ago and has been in hospital twice over the past 2 years with respiratory infections and exacerbations of breathlessness. She is prescribed two inhalers, along with rescue packs of steroids for acute episodes.

The team brought her case for an interpersonal dynamics consultation because of her tendency to overuse medications. They describe that she ‘pops steroids’. The team try to encourage Mrs S to call the respiratory hotline before resorting to her rescue packs, but she often ignores this advice, taking the medication before calling and telling the team that ‘all this could have been avoided’ if she had taken the medication even earlier. She is often angry at being denied greater access to the team and accuses them of ‘laziness’.

Mrs S is described as generally affable and well-presented. The team report that they ‘cannot get her out of the consultation room’; she ignores all normal cues to leave, until they eventually have to physically corral her out of the room. The team feel that they often comply with her requests for more medications in order to end the consultation and end up treating what should be ‘everyday chronic lung symptoms’ as if they were exacerbations.

The team described Mrs S's interactions in the following way (Fig. 4).

FIG 4 The dysfunctional cycle in case 3: Mrs S.

Perspective A (how the patient experiences others):

• abandoning and ignoring – Mrs S feels angry that she is not being given treatment soon enough; she has described the team as ‘lazy’ for not treating her more intensively.

Perspective B (how the patient experiences themselves):

• independent and knowing best – Mrs S often emphasises her full schedule of activities, and tells the team how she ought to be treated and how she does not have time to slow down.

Perspective C (members of staff experience the patient as):

• behaving as if she knows best – Mrs S often insists on having further medication, and staff find it difficult to get her out of the consultation room because of her talking.

Perspective D (members of staff experience themselves as):

• abandoning and ignoring – staff often feel that they are neglecting Mrs S and not giving her what she wants, such as more of their time or more medication.

• giving up and complying with her – the staff end up feeling overwhelmed and agree to prescribe Mrs S more medication in the hope of getting her to leave the consultation room.

Formulation

The formulation highlighted how Mrs S often came across as independent and behaved as if she knew best. Her overuse of clinical time and medication were probably related to a need for reassurance and support. Mrs S often felt ignored and undertreated by the team. The medication enabled her independence and its overuse served as a surrogate for other forms of care. For Mrs S the need to be independent probably served as a key defence and protection against not only this perceived neglect but also the fear of infirmity and loneliness, and as a distraction from the less happy aspects of her life, such as the loss of her husband.

We can postulate that growing up, Mrs S might have felt overlooked and neglected, as she was the youngest in a large struggling family. One can imagine how a learned self-sufficiency and independence might have been both her means of protection against this felt neglect and what enabled her to move away and make a new life for herself. Mrs S's sensitivity to her perceived neglect by clinicians probably derives from these experiences growing up. The internalisation of this childhood neglect creates a pattern of compulsive self-reliance (Bowlby Reference Bowlby1977) that serves as her defence against the risk of rejection and not receiving what she needs from others. This way of operating prevents her from engaging in the self-care that her physical health requires. She privileges her ability outwardly to perform and adhere to her rigid routine, but neglects her physical needs.

The formulation helped the team to see that they were feeling stuck and demoralised with Mrs S, as they could not offer her what she wanted. They were struck by how guilty they had come to feel, and in some ways they too had overlooked Mrs S's primary fears of loneliness, old age and reduced level of functioning.

After the interpersonal dynamics consultation the team decided to refer Mrs S to a community respiratory nurse who would form the single point of contact and develop a rapport with Mrs S in order to carry on engaging her with her management plan. They also referred Mrs S to a charity that offered support and social engagement to people with emphysema. Once the respiratory nurse had reduced Mrs S's use of rescue medications the team discharged her back to primary care services.

Discussion

These three cases serve as examples of the dysfunctional relational patterns that patients and their care teams can be drawn into. These patterns can be traced back to the patients’ experiences growing up and their previous significant relationships. It is often during times of personal crisis such as bereavement and loss, physical illness and the vulnerability of becoming a patient that attachment patterns become highly activated (Bowlby Reference Bowlby1977). As clinical staff come to represent the significant caregivers of the patient's past, powerful emotions are evoked and historical misgivings come to the fore.

We see how the team can often unwittingly collude with a patient's attempts to avoid painful aspects of reality. This denial is inevitably rooted in the patient's fears about their own mortality, their sense of self and their vulnerability in the face of illness.

Where teams become caught up in dysfunctional patterns, blind spots and biases in management can result. This can put patients at risk of neglect and iatrogenic harm, and lead to high levels of stress, poor communication and burnout in the teams.

Although the required changes to treatment plans are often straightforward, healthcare professionals can underestimate the obfuscating power of these relational processes unless they are experienced first-hand. In each of the above cases it was the interpersonal dynamics consultation's provision of a space for thinking and dialogue that helped the teams to gain the necessary distance to arrive at new insights and treatment plans.

Giving a team the time and space to think about a case sometimes has the uncanny property of unsticking the behaviour of the patient, even without changes in objective management. One can postulate that allowing the team to express their emotions and think together about a case creates subtle changes in each member's ability to empathise and contain a patient, which the patient in turn picks up on.

Conclusions

The interpersonal dynamics consultation is an accessible and helpful reflective practice tool for the understanding and effective treatment of patients who present with relational difficulties. It is also an essential way in which professionals can process the complex emotions that come with their role, and through this improve the functioning of their teams and institutions.

There are numerous examples of dysfunctional relational patterns that can affect optimal care in medical settings. Patients with difficult interpersonal styles can take up much of the capacity of medical teams, who are not accustomed to thinking about the relational complexities that underlie their cases. The vignettes described above are examples of some of the challenging cases that medical teams are confronted with, and the dangerous consequences that can ensue if they are not properly thought about in a reflective manner. They illustrate how the interpersonal dynamics consultation can help to illuminate the dysfunctional relational patterns that give rise to these perplexing cases. Not only does the interpersonal dynamics consultation help medical teams to think about these patients, it also provides them with an accessible model of reflective practice to help reduce stress and burnout.

It is hoped that this approach might complement and enrich the growing literature in liaison psychiatry. Beyond its use in psychiatric practice, the model offers a way of reflecting on the array of clinical conundrums that arise in medical care, where mind and body are interrelated, and of mediating the interdisciplinary tensions that can arise when working in this area.

Interpersonal dynamics training provides psychiatrists with a useful tool for consultation and psychotherapeutic thinking and can complement their existing clinical experience. The interpersonal dynamics model can be used for their own clinical cases, team meetings and consultations for other teams.

Although this project is still in its early stages, we have witnessed promising results in the medical teams that we have consulted for. Feedback questionnaires from the teams receiving the consultations give positive results, with members expressing appreciation for how the sessions give them an opportunity to express their feelings, communicate with their colleagues and see their patients in a different way.

Future qualitative studies are needed in order to more fully explore the experience of the teams who receive these consultations, how the consultations might assist in individual and team functioning and support changes in management plans. Research is also needed to quantify the impact of this tool using objective measures such as frequent attendances, serious unexpected incidents, iatrogenic harm and other patient outcomes.

This project promotes working at the interface of physical and mental healthcare and facilitates the important translational work of making psychiatry and psychotherapeutic ideas applicable to a larger audience. In a climate where medicine tends to be ever more mechanistic and protocol driven, the interpersonal dynamics consultation reminds professionals of the importance of recognising and decoding their subjective experiences in order to effectively understand their patients. Its systematic structure and insistence on evidence for the feelings of others avoids the projection of their own feelings onto others. This mode of working provides an ethical framework for effective, patient-centred care.

Acknowledgement

The project described in this article is funded by a grant from Health Education England (London and South East).

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 Reflective practice is:

a the application of theoretical knowledge to clinical practice

b a way in which clinicians can learn from the critical appraisal of their own experiences

c most relevant to inexperienced clinicians

d most helpful for simple problems

e only relevant to mental health settings.

2 Group-based reflective practice:

a is common in medical settings

b should be conducted with judgement and blame

c is well-researched, with high levels of evidence

d requires emotional safety in order to promote group functioning

e is not required outside of the mental health context.

3 An interpersonal dynamics consultation requires:

a only the most highly qualified clinicians to be present

b a lengthy training process for facilitators

c a 2-hour session for discussion

d the presence of as many members of the MDT as practicable

e a psychiatric assessment to have been completed for the patient beforehand.

4 The four interpersonal perspectives are:

a the perspectives gathered when four people interact

b ways of interacting that the patient and team are fully conscious of

c obtained using role-play and imagination by the team

d the perspectives that constitute the processes of transference and countertransference

e different perspectives about the management plan.

5 An interpersonal dynamics consultation is most useful:

a for patients who do not wish to consent to treatment

b when a team has a good understanding of the patient

c when the team and the patient have been drawn into dysfunctional ways of relating

d in situations where there is a high risk of litigation

e for teams who deal with psychiatric patients.

MCQ answers

1 b 2 d 3 d 4 d 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.