Research aim and significance

Despite ongoing fieldwork focusing on the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods of the Aegean, the eastern part of this region, especially western Turkey, remains almost entirely unexplored in terms of early prehistory. There is virtually no evidence from this area that can contribute to broader research themes such as the dispersal of early hominins, the distribution of Early Holocene foragers and early forager-farmer interactions. The primary aim of the Karaburun Archaeological Survey Project is to address this situation by collecting data from the eastern side of the Aegean Sea, thereby contributing to the currently debated issues of Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean prehistory.

The survey area

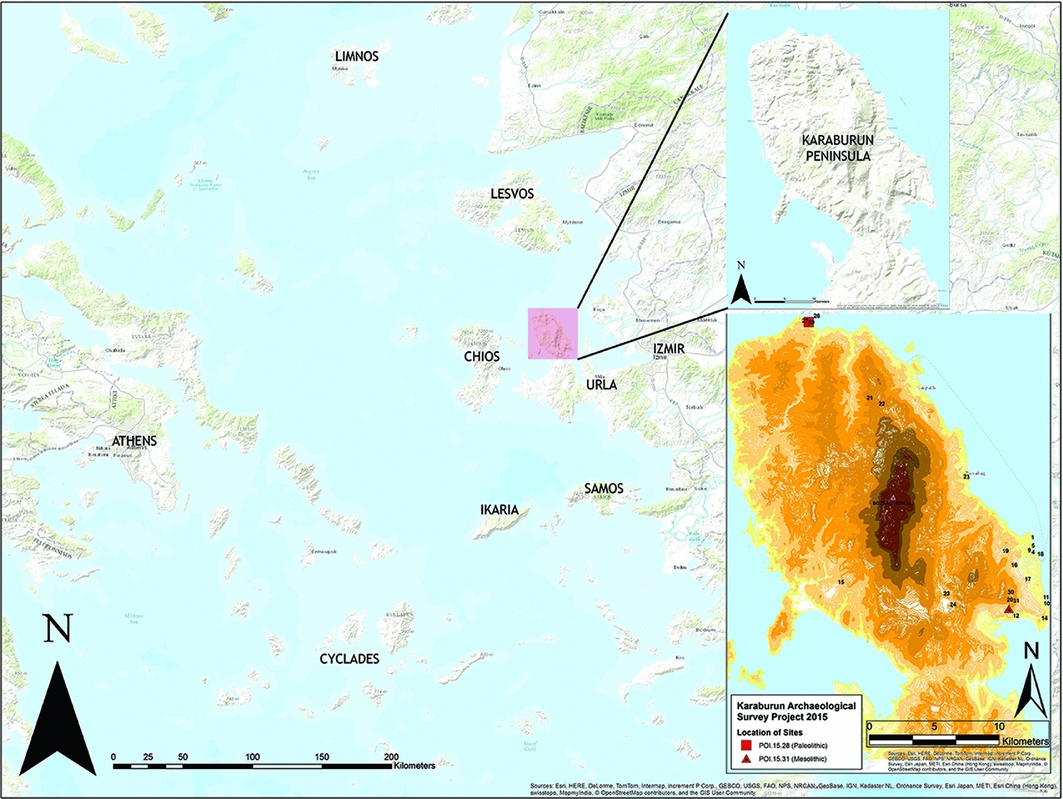

The Karaburun Peninsula occupies a strategic position in the eastern Aegean and lies close to the modern city of Izmir (Figure 1). Prior to the current project, limited archaeological research had been undertaken in this region, emphasising its rugged terrain, the thick cover of Mediterranean evergreen vegetation and low surface visibility. The Karaburun Archaeological Survey Project commenced in 2015 and is the first to investigate this ‘difficult’ landscape systematically.

Figure 1. The location of Karaburun Peninsula in the Aegean and the map of the survey area with the sites mentioned in the text.

The project is designed as a pedestrian survey with both extensive and intensive strategies. The team documents all traces of past human activity using standard recording forms noting geological, geomorphological, vegetational and archaeological information. The first season of fieldwork recorded 31 places with archaeological remains, including seven of prehistoric date (Figure 1). This article reports on the evidence for the earliest human activity identified so far at Karaburun.

Lower Palaeolithic locality of Kömürburnu

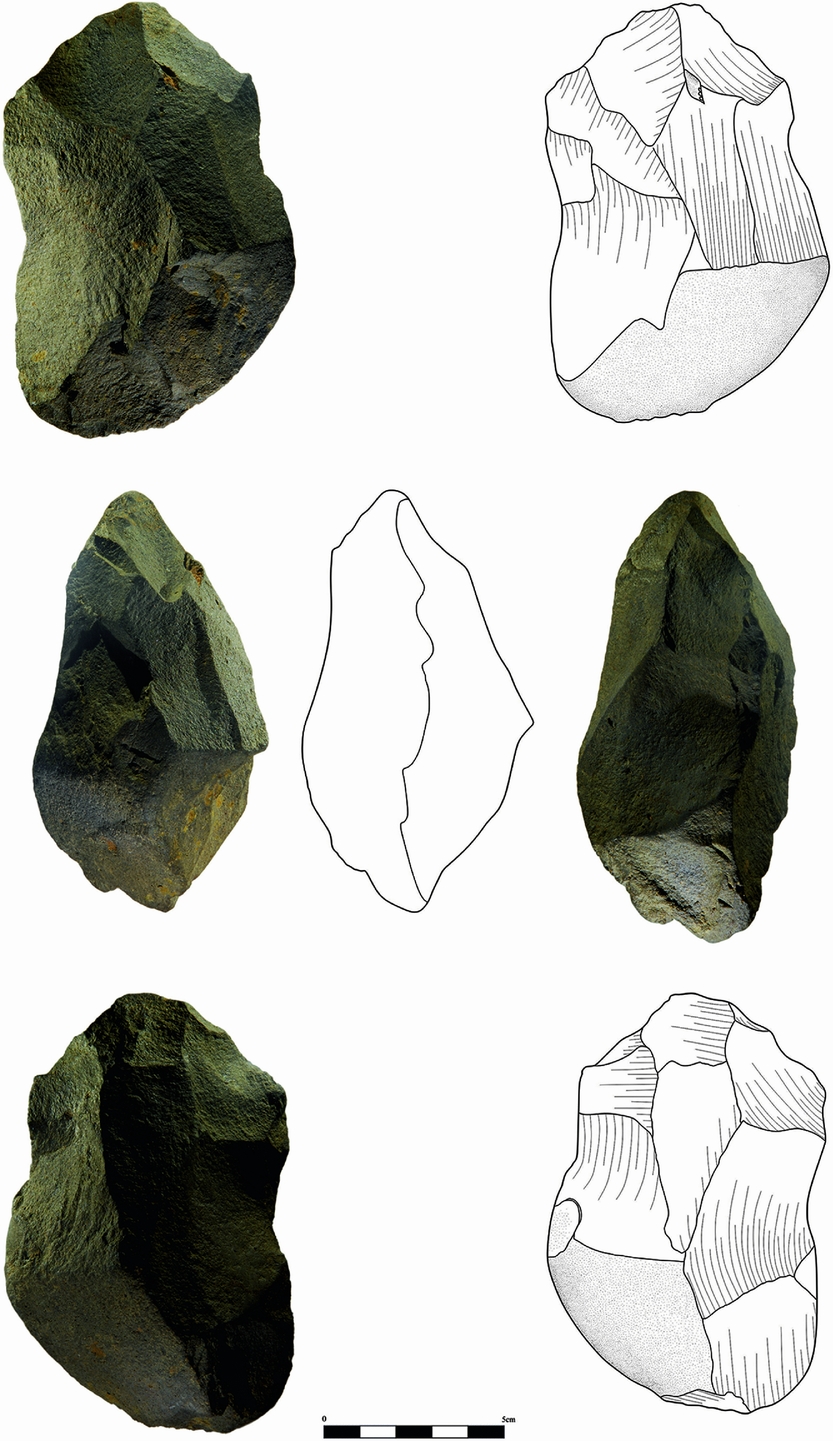

Prior to our survey, the earliest known site at Karaburun was limited to sporadic Neolithic and Chalcolithic findspots (Koşay & Gültekin Reference Koşay and Gültekin1949; Uhri et al. Reference Uhri, Öz and Gülbay2010). The 2015 fieldwork identified artefacts of much earlier date. Pedestrian survey of the Kömürburnu locality—a volcanic outcrop located on the northern coast of the peninsula (Figure 2)—collected a handaxe shaped from locally available andesite (115 × 65 × 70mm). This is a biface, shaped by a hard hammer, and has a lenticular section and long S-shaped edge profiles (Figure 3). The tip and one edge are sharper; the other edge is irregularly shaped. The base of the biface is not significantly worked and bears 20–30 per cent secondary cortex on each face. At this stage, it is not possible to give a precise date for this object, but based on its techno-typology, it is of Lower Palaeolithic age sensu lato. Associated with this biface, we also discovered cores and flakes.

Figure 2. General view of the volcanic outcrops at Kömürburnu locality where Lower Palaeolithic activity has been identified (POI.15.28).

Figure 3. Lower Palaeolithic biface from POI.15.28 (drawing by G. Özçolak and E. Sezgin).

In the 1960s, non-systematic research in Izmir Province recovered two Palaeolithic handaxes. One of them has been attributed to the Lower Palaeolithic; it is a very large, flat and elongated flint biface with irregular edge profiles (Kansu Reference Kansu1963). The other biface is ovate in shape and relatively small; this has been attributed to the Micoquian and probably of Middle Palaeolithic date (Kansu Reference Kansu1969). Taking into account their technological properties, these two isolated finds from the neighbouring areas are different to the Karaburun biface. They do, however, reflect the presence of bifacial industries in this westernmost part of Anatolia, which may also be considered alongside the Acheulean site of Rodafnidia on Lesvos, especially when we consider the existence of a land bridge between these two localities during the Lower Palaeolithic (Galanidou et al. Reference Galanidou, Cole, Iliopoulos and McNabb2013).

The Mesolithic findspot near Mordoğan

The second early prehistoric findspot (POI.15.31) located during the 2015 work is a surface scatter of chipped stones found near limestone outcrops overlooking the Balıklıova Bay on the modern road from Mordoğan to Izmir. The chipped stones are produced from white patinated flint, and display a flake-based microlithic technology without the presence of geometrics. The collection of 116 lithics was found loosely scattered across the surface and seems to have been eroded from a location that remains undiscovered. The lithics represent a very crude, flake-based industry with few retouched specimens (Figure 4). Only 12 pieces(around 10 per cent of the assemblage) can be attributed to a specific tool type: three endscrapers, three notches and six retouched flakes. The endscrapers were made on flakes and are highly reduced (Figure 5). Unretouched flakes dominate the assemblage (63 pieces), with an average length of 27mm (ranging from 14–70mm; standard deviation: 9.14mm). Only three blades are represented, of which two are crested. There are five cores in the assemblage, including one blade core.

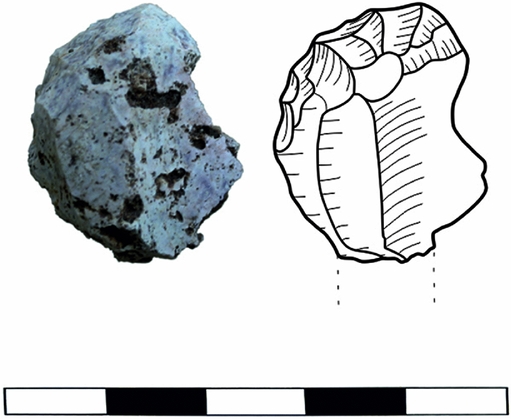

Figure 4. The flake-based lithic assemblage produced with white patinated flint from POI.15.31.

Figure 5. A typical endscraper with semi-abrupt retouch from POI.15.31 (drawing by G. Özçolak and E. Sezgin).

The technology encountered at POI.15.31 is in no way comparable to Eastern Mediterranean Epipalaeolithic or Pre-Pottery Neolithic industries. Moreover, neither technological nor typological similarities can be identified with the assemblage from the open-air site of Ouriakos on Limnos (Efstratiou et al. Reference Efstratiou, Biagi and Starnini2014). As far as preliminary observations permit, the industry represented at POI.15.31 resembles Aegean Mesolithic chipped stone assemblages identified at Franchthi lithic phase VII, Kerame 1 on Ikaria, Maroulas on Kythnos, and Stélida on Naxos (Perlès Reference Perlès, Bailey, Adam, Bailey, Panagopolou and Perlès1999; Sampson et al. Reference Sampson, Kaczanowska and Kozlowski2012; Carter et al. Reference Carter, Contreras, Mihailović, Moutsiou, Skarpelis and Doyle2014). This findspot represents virtually the only known Mesolithic site from the western coast of Turkey that can be compared with Early Holocene forager sites elsewhere in the Aegean. As such, POI.15.31 merits more detailed investigation in future fieldwork seasons.

Acknowledgements

The project is being conducted with the permission of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, and is supported by Ege University Research Fund (grant 2015-EDB-005), Groningen University Institute of Archaeology and the Municipality of Karaburun.