In April 1902 the magazine Italia moderna devoted an entire issue to the young and fast-rising soprano Emma Carelli. Among a wide range of articles and encomia penned by prominent opera and theatre critics, journalists and composers we find a short account of Carelli's early struggles in the opera world.Footnote 1 The brief biographical sketch put together by an anonymous writer on the editorial board of Italia moderna includes a paragraph-long light-hearted narrative of an episode that well portrays Carelli's assertiveness:

This girl not yet eighteen, endowed with an exuberant mind and a spirit infused with the sacred flame of art but almost completely lacking in voice, after an endless series of arguments with her own teacher, who was also her father, Beniamino Carelli, the illustrious dean of the Neapolitan Conservatoire S. Pietro a Majella – one fine day – bored with the constant opposition of that supremely annoying professor who pretended to convince her that in the first place a voice was necessary in order to sing – declared in front of the whole classroom that he was a donkey and, putting the hat jauntily on her dishevelled yet magnificent tresses, she strode out of the School shouting that ‘she would show whether Emma Carelli could or could not sing’.Footnote 2

The anecdotical flavour of this writing (with probably apocryphal details) does not detract from the impression that, from her formative years, Carelli demonstrated remarkable assertiveness and scant tolerance for the norms of female behaviour. In effect, the tale from Italia moderna already signals what Susan Rutherford has identified as Carell's ‘restless tilting against convention’.Footnote 3 This aspect of the singer's personality, which Rutherford so convincingly discusses in relation to her activity as opera impresaria, had already been adumbrated by Carelli's brother, Augusto Carelli, in his moving and richly detailed biography of his sister.Footnote 4 More recently, Carelli has become the subject of a documentary film, La prima donna (2019), in which film director Tony Saccucci similarly highlights not only the innovative artistry of the singer but also her boldness as long-term impresaria of the Teatro Costanzi in Rome (1911–26), by contextualising Carelli within the rapidly changing socio-political system of Italy from the liberal age to the advent of fascism.Footnote 5

After a precocious debut in Saverio Mercadante's La vestale (1895), Emma Carelli performed in minor Italian theatres for four years or so before her international career was launched at the age of twenty-three through several appearances in quick succession at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome (including in 1899 with Enrico Caruso) and the Milanese Teatro alla Scala (season 1899/1900, with Francesco Tamagno and Arturo Toscanini). For over a decade from 1900, Carelli brought the new operas of verismo composers – including Giordano's Fedora, Leoncavallo's Zazà, Mascagni's Iris and Puccini's Tosca – to first-rank Italian and European houses and to the major operatic centres of Latin America, where she was present in most seasons between 1900 and 1909.Footnote 6 This brilliant journey came to a close between 1911 and 1912, when the singer took on the management of the Teatro Costanzi in Rome, running the house until the fascist government nationalised the venue in 1926. This period was marked by innovative programming and a hectic pace of production, while the house was provided with a permanent chorus and orchestra together with a set design workshop, all of which consolidated the key position of the theatre in the cultural landscape of the capital.

My intention is not to recount the story of Carelli's career as impresaria.Footnote 7 Rather, I provide the backstory to that career, examined from the perspective of women's history. By continuously defying well-established social codes of female conduct, Carelli inscribed herself within a larger network of women who strove to shape their lives as ‘projects’ of their own.Footnote 8 Writers such as Sibilla Aleramo (1876–1960) and Olga Ossani (1857–1933) – the latter has claims to be the first Italian female journalist – medical doctor Maria Montessori (1870–1952) and actress Eleonora Duse (1858–1924), among many others, took full control of (and responsibility for) their personal and professional journeys by challenging the values that regulated the traditional constructions of femininity.Footnote 9 These exceptional figures advocated (from within or without the female movement) for the right of women to pursue their art and professional ambitions. In Susan Glenn's words, they stood for their right ‘not only to “be a self” but to “be for [themselves]”’.Footnote 10

In early twentieth-century Italy such aspirations threatened the socio-juridical system that defined the values of the liberal state and aroused strong social resistance. In this context, a woman who attempted to express her personality in the public arena of a profession was bound to be in tension with the long-cherished conservative ideal of domestic femininity that the liberal state still proudly advertised. By framing Carelli within this cultural and socio-political context, I hope to signal the ways in which the soprano and impresaria disrupted ideals of traditional femininity by pursuing her own aspirations. To this end, I will examine selected excerpts from Carelli's own scrapbooks together with a set of letters that she wrote to the critic and theatre impresario Adolfo Re Riccardi in the early 1900s. I argue that a contextual reading of these materials reveals a practical woman endowed with remarkable organisational skills, a keen interest in the managerial side of her craft and a sharp eye for business – particularly during the long months of touring Latin America. Carelli honed these characteristics throughout her seventeen years on the opera stage (1895–1912). I contend that it was precisely these qualities which enabled her transition from the stage to opera management, and marked it as the independent choice and hard-fought battle of a woman determined to live up to her own expectations.

Early twentieth-century Italy and women

In liberal Italy, the Codes of Law, the Church, social customs and positivist science continued to link the social value of women to their attributes as wives and mothers, and nurtured an aspiration for individual self-effacement which would find its reward in a life of domestic bliss. It was true that in parliamentary debate a few isolated voices had been levelled against the misogyny of Italian politics, and newspapers and periodicals such as La vita and Critica sociale had attempted to advocate for women's presence in public life.Footnote 11 The state system as a whole, however, discriminated against its female citizens. Not only did Italian women have no voting rights and a precarious citizenship that was tied to their husband's nationality, but their ability to act in the private sphere was also severely hindered by the need for marital authorisation: wives were required to seek their husbands’ consent for any transaction regarding their assets.Footnote 12 Yet this ‘construction’ of femininity, still stubbornly built on the old model of domesticity, bore little relation to the every-day life of Italian women. Growing urban industrialisation pushed the liberal state to adopt an ambivalent strategy, and demand that these modern angels of the heart lend their arms as factory workers, or mould the minds of future generations as primary school teachers. In exceptional cases, women were even permitted to take up the professions and become journalists, doctors or lawyers.

Though burdened with a complex set of duties as workers, taxpayers, mothers, wives and caretakers, Italian women were refused the corresponding rights. This situation only worsened when the first wave of industrialisation came to an end, and the concentration of big capital power on heavy industry made women's labour (allegedly) redundant. In this context, the passing of protective legislation on women's and children's labour (Carcano Law, 1902) perversely created the conditions for more exploitation.Footnote 13 This paternalistic approach pushed women out of the job market and back inside the house, while they were reemployed in those jobs that, being inherently unhealthy and dangerous, tended to remain vacant.Footnote 14 The Socialist Party played a key role in achieving this disastrous retrograde step, thereby alienating a large chunk of its female membership.Footnote 15 These upheavals fuelled the political action of the women's movement at the beginning of the new century, when female organisations completely redefined their structures, leading – in the words of Franca Pieroni Bortolotti, the foremost historian of Italian feminism – to the ‘official birth of proper feminist associations’.Footnote 16

The so-called Giolittian era (1900–11), named after the prime minister who shaped Italian politics during that decade, was a period of great expectation for Italian women. Through the publication of dozens of political journals and through countless philanthropic initiatives, female associations not only reached out to the highest number of women to date, but also fuelled political debate around the ‘female question’, i.e. the condition of women within the family, the workplace and vis-à-vis the state (two major campaigns for female suffrage were promoted in 1904 and 1910, though both failed).Footnote 17 As revealed by Annarita Buttafuoco's study of female periodicals (written by women for women), a febrile period of publishing activity aimed to support a programme of ‘continuous education’ for women, stimulating women of any class or background to become aware of their condition, abandon a passive attitude towards their life and take action and responsibility for themselves.Footnote 18

Emma Carelli's early adult life, stellar singing years and career change spanned exactly these years of hope for a brighter future for Italian women. One might imagine that this political ferment would have alerted Carelli to the condition of women, but it was unlikely that any such awareness would have transformed her into an activist for female emancipation. An open commitment to this cause could still endanger the position of stage artists or women whose professions put them under public scrutiny, such as popular novelists or newspapers directors. Thus women writers, as Antonia Arslan has insightfully observed, could not afford to scare away their female readership by drawing the logical conclusions to which acute analyses of the female condition in their novels and short stories would naturally lead. Rather, these authors empathised with the suffering of their vanquished protagonists and adopted their pessimistic views about ‘the inevitability of the final defeat’ and ‘reasserted [traditional] social norms’.Footnote 19

Singers and actresses, for their part, had long posed a direct threat to ‘true’ femininity by publicly displaying their bodies in order to earn a livelihood and by enjoying a level of autonomy denied to the ‘ordinary’ woman. To counteract this impression of dubious virtue, nineteenth-century stage artists devised various strategies to display an image of cosy domesticity, which was still deployed by many of them at the beginning of the new century.Footnote 20 In this situation, overt association with the political movement for female emancipation would have been perceived as unwise for stage artists who had to protect their careers and livelihoods.

With respect to Carelli, however, matters were more acute. In his biography of his sister, Augusto Carelli mentions her conservative political inclinations, explaining that her vision was fundamentally at odds with that of her (at the time) socialist husband Walter Mocchi. Before marrying Mocchi, Carelli joined him on a small island in southern Italy where Mocchi was confined under house arrest following his involvement in the 1898 social unrest around Naples. Reflecting on this episode, Susan Rutherford cautiously advanced the hypothesis that Carelli might have been close to the political beliefs of Mocchi, only to dismiss this possibility and side with the narrative provided by Augusto Carelli. The singer's sympathy for the proletariat was limited ‘to the idea of nationalism, a well-trained army, and a flourishing industrial workforce – all makers of the “new” Italy’, states Rutherford, foregrounding Carelli's latent affinity with the future fascist ideology.Footnote 21 Such a backdrop could actually align Carelli with possible a-feminist or anti-feminist positions that were shared by a number of high-profile women, such as journalist Matilde Serao and writer Neera.Footnote 22 The combined argument of Augusto Carelli and Susan Rutherford might even be reinforced by further evidence that has emerged recently. In 1925, the fascist government led a secret political investigation into Carelli's directorship of the Teatro Costanzi, following up on anonymous allegations that accused the impresaria of being an opponent of the regime, openly insulting its most eminent personalities. The report of the Chief of Police reveals that the fascists were unconcerned about these attacks:

Regarding the anonymous accusation, the investigation demonstrated that in her speeches in the premises of the theatre [Carelli] was in the habit of attacking members of the fascist government, as well as the Prime Minister. However, it appears that she only talks that way because Carelli had demanded from the government a grant to lighten the heavy expenses that she will have to bear for the forthcoming lyrical season, and has not yet obtained it. … Mrs Carelli does not have any political principles, because she does not care about politics at all.Footnote 23

For the regime, the matter was settled by ascertaining that Carelli's reasons had nothing to do with politics, and she was preoccupied with securing the money to run her season. Establishing the absence of political convictions on the part of Carelli requires a considerable degree of conjectural thinking. However, Carelli's hopes to be appointed artistic director of a nationalised Teatro Costanzi after she and Mocchi sold their majority shares to the fascist government demonstrates that, beyond and above politics, her heart lay with the future of the theatre.Footnote 24 Whatever image we feel inclined to form of Carelli, one recurring element defines her personality again and again: her determination to sustain a personal life-project that could find no endorsement within the values of the society she inhabited.

The scrapbooks: clues to Carelli

For about seventeen years, Carelli meticulously collected her press reviews and other performance-related materials in nine scrapbooks, all scrupulously itemised. It is truly a fascinating source, invaluable from both biographical and historiographical points of view. This assemblage helps us to reconstruct the phases of Carelli’s stage career with some precision, create a timeline of her performances, and identify a wealth of sources of press criticism. In several cases, the performance histories of little-known operas and major works in what were considered at the time as remote countries can be partially pieced together through the documents assembled by the singer. The scrapbooks also exhibit interesting strategies of self-representation and more broadly feed into gender studies and women's history.Footnote 25 Obvious limits of space hinder a full and many-layered analysis of the scrapbooks here, but they are nevertheless valuable clues to specific qualities of Carelli's personality.

Only seven of Carelli's nine original albums survive today. They are housed at the Historical Archive of the Rome Opera House, the venue that, under the name of Teatro Costanzi, Carelli directed for over fourteen years (1911–26).Footnote 26 Most of the scrapbooks’ content is made up of press reviews that cover the performance history of the soprano from the provincial theatres where Carelli took her first steps, to major Italian, European and Latin American opera houses. Carelli devised specific strategies to collect this material and determine what to keep and what to leave out. Unsurprisingly she often included only those sections of reviews which discussed her own performance.

The writing she selected contained admiring as well as damning comments about her singing and acting, and Carelli often seemed more interested in the critical reviews than in the flattering ones, as if she were engaging in solitary reflection or intellectual dispute with those condemning voices. She would highlight in pen entire paragraphs or underline specific sentences that expressed negative or challenging remarks by the critics. (There is no evidence that it was actually Carelli who marked the text, but the consistency of the approach and the interest in particularly insightful remarks about her interpretations and vocal limitations strongly suggest that it was she who scribbled on the text.) Only on specific occasions would Carelli paste in whole reviews: for premieres and for local premieres of operas first performed elsewhere, such as the 1900 Tosca premiere at the Teatro de la Opera in Buenos Aires (where Carelli in the title role was the only singer who had not participated in its Rome premiere). Finally, she collected complete reviews of works whose intrinsic artistic value was the object of heated critical debate, such as Mascagni's Iris and Leoncavallo's Zazà, which became two of Carelli's signature roles. Together with the reviews, however, Carelli collected other valuable materials, such as theatre programmes, playbills, long handwritten schedules of performances for the Latin American tours and, again when touring Latin America, a far more prosaic type of document: the receipts of the handsome payments she received for her benefit performances.

These different items provide us with access to the singer's mindset. By mining Carelli's scrapbooks, her exactness, accuracy, pragmatic nature and the various elements that attracted her attention while being a performer emerge. For instance, her data collection was faultless. All the names of newspapers and magazines, and the dates that she provided for the articles (or sections of them) that she included in the scrapbooks are correct. Every time I could double-check Carelli’s entry against the periodical in question, I have been able to verify that she provided the correct information, only in a few instances missing the exact date by one day.Footnote 27 With regard to other materials, Carelli tended to report more thoroughly on the season's programming and the financial aspects of specific performances and their organisation while touring the Latin American venues. On these occasions, she would write the lengthy schedules of rehearsals and performances directly into the scrapbooks, annotating the dates of each performance, including the many in which she did not participate, and the names of each singer and conductor – a habit she did not seem to have adopted when she performed in Italy.Footnote 28

The receipts of earnings and shares from benefit concerts also became an object of collecting interest and, perhaps, an aid to analysing the economics of the theatre industry. The singer was always eager to collect the reviews of her benefit concerts. They often listed jewels and other precious gifts presented to Carelli during her farewell performances, and so recorded her growing artistic prestige and international ranking. However, for the Latin American benefit performances only, Carelli included the cargos de boleteria (box-office receipts) in addition to the reviews. These receipts itemised the earnings for each seat category, the price per seat, the total profit and the split between Carelli and the management.Footnote 29 Carelli may simply have been proud of the astounding amounts she was earning in Latin America. Or perhaps she collected these documents because she had a specific interest in the Latin American operatic market and its economics, an idea supported by the content and tone of the correspondence with Adolfo Re Riccardi that I mentioned at the opening of the article. However, before I venture any further into this subject, I will address the critical reception of the singer to demonstrate how perceptions of her unconventionality, modernity and highly defined artistic individuality contribute to my broader contention: that Carelli was shaping her life, in a deliberate and self-conscious way, as a project of her own.

The early reviews describe Carelli as a fine and intelligent singer who – trained at the excellent singing school of her father Beniamino Carelli – could rely on a solid vocal technique. Judgements about her acting vary. Reviewing her interpretation of Massenet's Manon as early as 1897, some observed that ‘the simplicity and naturalness of her movements charm the audience’, while others, such as the critic of Il pungolo parlamentare, pointed out that she ‘falls into deplorable exaggerations which coarsen her gestures’.Footnote 30 The critical consensus around her voice was that it was small, fresh and well-cultivated. However, the critic of Il pungolo underlines the shrillness of Carelli's voice in the upper range, although ‘it acquires great charm and the sweetest of sound in thinly scored and delicate passages’.Footnote 31 La tribuna confirms this opinion by praising the ‘flexibility of [Carelli's] voice’ and her ability to ‘expressively colour the musical phrase’ – notwithstanding the limited range of her voice.Footnote 32 Portrayals such as these are completely at odds with the type of singing and expressivity with which Carelli was associated only a few years later, when her vehement and thunderous renditions of verismo roles such as Mascagni's Santuzza (Cavalleria rusticana) and Iris, Giordano's Fedora, Puccini's Tosca, and Leoncavallo's Zazà were disrupting long-established vocal practices. Tellingly, the comments of the critic for Il pungolo on Carelli's lack of vocal power piqued the singer's interest. She marked in blue the section of the review which digressed on her shortcomings in Manon's third act, the most tumultuously dramatic. While in Acts I and II the ‘exquisite’ singing of Carelli well suited the delicate sections in Manon's role, the complexity of overwhelming sentiments in Act III required ‘a voice more robust and warm … a vehement and dramatic expansion of singing’, which the young artist seemed incapable of producing.Footnote 33 Carelli might have sensed or hoped that her voice would develop into a heavier, more dramatic type that could open the way to the erotically charged characters of modern operas that were better attuned to her fiery personality.

The first noteworthy role which offered scope for these traits to shine was undoubtedly the eponymous heroine of Umberto Giordano's Fedora. After the successful premiere of the work at the Teatro Lirico in Milan (1898) with Gemma Bellincioni in the title role and Enrico Caruso as Loris, Carelli was engaged hastily for the Mantua production (14 January 1899).Footnote 34 Having heard Carelli in Camillo De Nardis's Stella at the same Teatro Lirico (in November 1898), Giordano was determined to secure the singer as the protagonist for his Fedora.Footnote 35 The composer's instincts pointed him in the right direction, as the reviews of the Mantuan Fedora confirm. According to the critics of La provincia di Mantova, Corriere di Napoli and Don Marzio, several parts of the opera, including the prayer (la preghiera) and the oath (il giuramento) from Act I, which had previously gone unnoticed with Bellincioni in the role, were enthusiastically received by the audience.Footnote 36 Starting with this series of performances in Mantua, the press approved what was to become a long-running association between Carelli and the most popular roles of modern operas produced at the apogee of verismo. According to the press, Carelli's ability to persuade and move the audience with her interpretations of true-to-life characters rested on two fundamental attributes of her artistry: modern acting and an innovative approach to expressively nuanced diction.

For Lionello Spada reviewing Carelli in Mascagni's Iris at the Teatro Costanzi in 1902, the singer

lives in the character; in fact, in what is truly a creative miracle, she gives to it everything that is missing in the libretto in terms of truth, and frank naivety; when the sweet girl tightly embraces the doll against her chest as if it were a living creature, when she is inebriated with the memory of her little house and its small garden and its flowers, and when she reaches the drama's greatest heights in the terror of her dream which foretells her misfortune; in the defence of her purity from the temptations of the seducer, and the awakening of her senses … She modulates [her singing] according to the action and fuses together vocal mastery and dramatic effectiveness … [and thus] achieves the great modern conquest of those perfect and privileged artists, who can not only sing their part with art but also embody their character with sincerity on the stage.Footnote 37

The unusual ability of Carelli to match high-level singing with a truthful representation of the drama is labelled as ‘modern’. The standard of her acting, moreover, prompted endless comparisons with the great actresses of the spoken theatre of her age, above all Eleonora Duse, Virginia Mariani and Virginia Reiter. The modernity of Carelli, however, was also perceived in her specific manner of articulating the words: a clear and richly varied pronunciation of the text that lent a vibrant, vital quality to her phrasing, fleshing out the voluptuous morbidezza of her characters. In a 1904 production of Iris (again at the Teatro Costanzi) Nicola D'Atri from Il giornale d'Italia observes that

Carelli has no peer in the part of Iris which she has actually created … the sweetness of her perfectly in-tune voice, the marvellous clarity of her diction, the warm phrasing, all the female softness (morbidezza) that is in the music of Iris [and that Carelli] transformed into shades of colour, renewed the ancient admiration of her Roman fans.Footnote 38

D'Atri, as well as many other commentators before and after him, plainly acknowledged the key role of Carelli in ensuring the success of the work. Similar statements can be read with regard to other roles, including the heroines of Leoncavallo's Zazà – which ‘has conquered its place in the repertoire because of Carelli, its greatest and most sophisticated protagonist’ – and Puccini's Tosca.Footnote 39

Beyond her perceived modernity, Carelli's interpretations of all these characters, as well as those from a handful of romantic melodrammi, reflect the unconventional approach of the singer to artistic representation – as well as her open refusal of traditional modes of stage performance. A brilliant daughter of her era, she aimed at a frank, utterly human and highly moving incarnation of her characters without ever shying away from the ugly or uncomfortable aspects implicit in the plot. Carelli, as we have seen, would pay close attention to the critical response to her interpretations, and it satisfied her that critics wrestled over her highly individualised, defiant and unconventional renditions.

Carelli's defiant attitude towards tradition was underscored by critics all over Italy. Her Desdemona, performed opposite Tamagno's Otello during her first season at the Teatro alla Scala in 1899, was frowned upon by the critic of the Milanese La perseveranza, Giovanni Battista Nappi. Carelli circled the whole paragraph concerning her performance and scribbled a plus sign next to the following sentence: ‘she gave us a Desdemona infused with rebellion rather than that passivity to which the tragedy condemned her. The poetry that envelops this character, all sweetness, humbleness and submissiveness, comes out rather blurred.’Footnote 40 The sense of measure and balance that Nappi urged Carelli to find did not sit well with the interpreter. Only a month before the beginning of this season, Carelli was playing Margherita in Boito's Mefistofele in Rome. In this character, a critic reports that Carelli ‘departs from the tradition of the great interpreters and creates a non-Romantic Margherita’.Footnote 41

This departure from tradition is well explained in Augusto Carelli's biography as a vividly naturalistic portrayal of the character in which Carelli ignores every model of ideal beauty in her efforts to portray ‘a scrap of agonized life’, in the singer's alleged own words.Footnote 42 Carelli’s Margherita was hailed as a new creation and Carelli not only took just pride in this reaction, but she also sought the blessing of the opera’s composer. Carelli wrote to Boito to justify her unconventional approach to Margherita. In his response, preserved in one of the scrapbooks, he praises Carelli for her

new concept of Art … [that] could be neither more correct nor more clearly thought and expressed. If you have succeeded in realising it (I have no doubt) you deserve the clamorous triumph you obtained. I rejoice with you and for you and for the important aid that you are preparing to give to the Italian lyric theatre.Footnote 43

Boito's prediction was fulfilled by Carelli, whose remarkable artistic individuality and personal independence set her on a journey of extraordinary female achievement.

The correspondence with Adolfo Re Riccardi

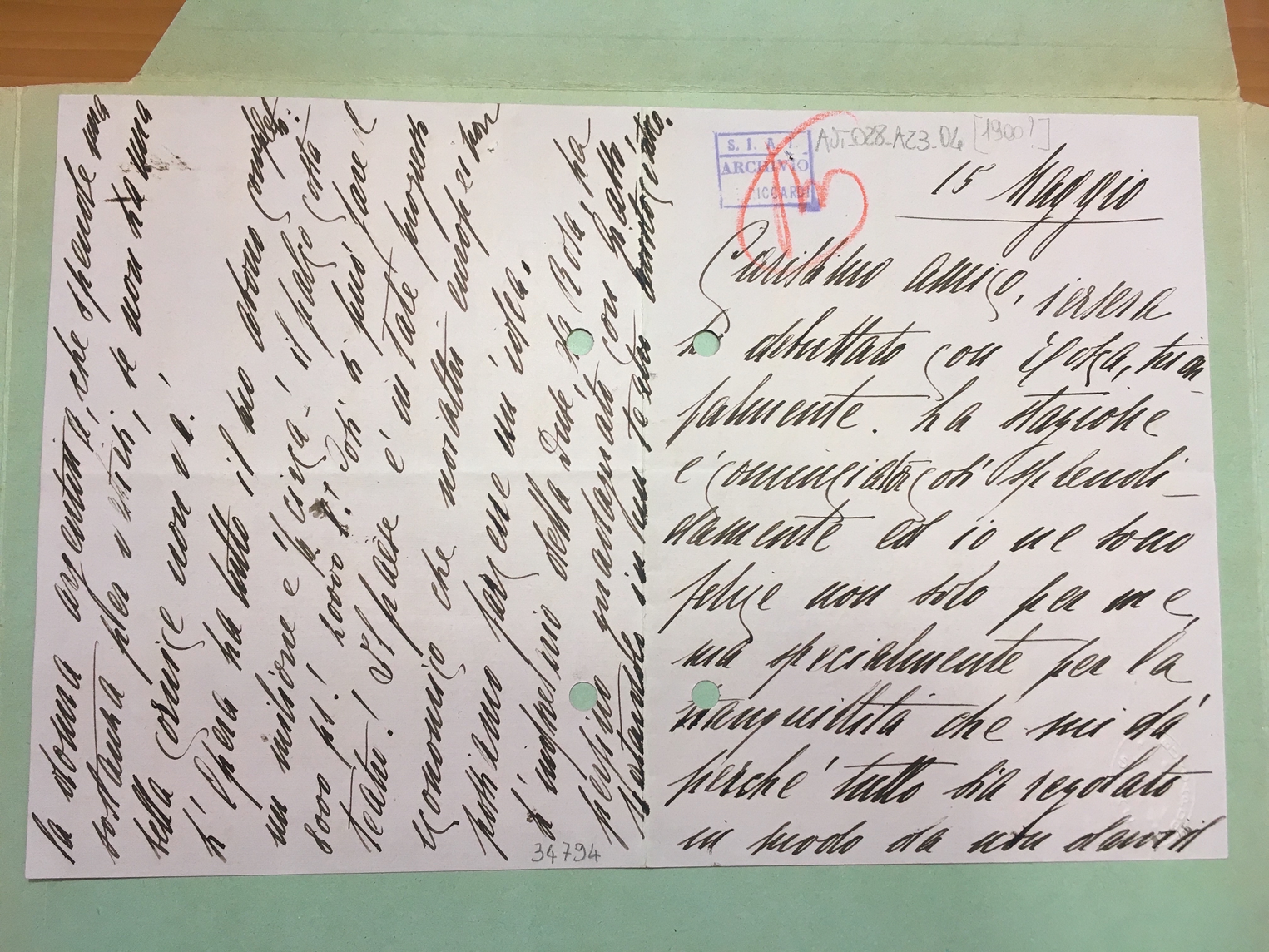

One of Italy's most respected critics and impresarios, Adolfo Re Riccardi (1859–1943), was a prominent figure in the theatrical life of the country and controlled most spoken theatre companies through his exclusive copyright over successful French plays.Footnote 44 The Archivio del Museo Teatrale del Burcardo in Rome preserves a set of letters and short notes that Carelli wrote to Re Riccardi in the early 1900s. This correspondence clearly highlights how Carelli valued Re Riccardi's friendship and admired the man with whom she sought to remain on good terms. Being a practical woman, Carelli typically discussed money matters, the vicissitudes of opera seasons and the news from the theatre world and its protagonists, although she also indulged in lighter topics such as the weather and gossip. One letter, however, is particularly telling in terms of Carelli's shifting interests from her own singing to the business opportunities for opera management. This missive was written from Buenos Aires on the 15 May 1907.Footnote 45 The year 1907 marked her fifth season in Latin America, following the 1900, 1902 and 1903 tours of Argentina and Brazil and a long 1905 season at the Teatro Municipal de Santiago, Chile. In May 1907 she was singing at the Teatro Coliseo for the Gran Compañia Lírica Italiana managed by Cesare Ciacchi, the impresario who would play a key role in the operatic ventures of Walter Mocchi that began at the end of that season with the creation of the Sociedad Teatral Ítalo-Argentina (STIA).Footnote 46 Given the importance of this document I will quote it in full (and see Figure 1 for a reproduction of the first page):

Dearest friend,

last night I opened the season with Tosca, triumphantly. The season has thus begun splendidly and I am very happy not only for me, but especially for you, because I know that a smoothly run season will not give you any headaches.

If you could see what a marvellous city is this B.A.! and how a man like yourself, although you cannot really complain about Italy, would have found a limitless field of action here! There is room for everybody here!

Imagine that the financier of our theatre, who is also the owner, owns a casino café chantant with a sort of hotel, a car park, a pavillon de las rosas sort of hall, where you can have tea and dinner, and then the splendid Coliseo, where 3000 people can be seated: 630 in the stalls, 600 in the balconies, 1,000 in the gallery and 800 in the amphitheatre. A modern and rich theatre, because the Argentine woman, who spends a fortune on dressing up, will simply not turn up if the setting is not beautiful!

The interior design is also wonderful and worth a million and a half. The stage costs 8,000 pesos! 20,000 liras! In this way it is possible to run a theatre! The country has made such huge strides economically that we Europeans cannot even imagine it.

Imagine that Duse's impresario has made profit with [illegible name of the play] presenting it in a theatre had [illegible writing].

Ciacchi already knows that he has to telegraph you 6,500 liras at the end of the month and, after all, Nicolai is informed about everything.

Here the autumn is beautiful and there with you the summer begins; have fun and enjoy your summery spirit.

I send you my most loving greetings,

Emma CarelliFootnote 47

Figure 1. First page of Carelli's letter to Adolfo Re Riccardi, 15 May 1907, courtesy of Biblioteca Museo Teatrale SIAE.

The opening sentence suggests that Re Riccardi had invested his own money in this season at the Teatro Coliseo. In effect, Carelli is rejoicing not only in her own success (‘I opened the season triumphantly’) but ‘especially’ in the certainty that the season will run smoothly and, therefore, will not create any problems for Re Riccardi.Footnote 48 Moreover, Cesare Ciacchi, the impresario who organised the season and apparently owned the Coliseo as well as other businesses orbiting around the theatre, will pay 6,500 liras to Riccardi by the end of May through Nicolai (Riccardi's secretary).

It is clear that Carelli was stirred by the thought of the financial gains that could be made in a city like Buenos Aires, where business opportunities lay round every corner, as long as one could spot them. For instance, Carelli mentions in passing the thirst for luxury of Argentine woman, only to highlight how astutely Ciacchi had exploited that desire and catered to it with a lavish interior design. As the collecting of cargos de boleteria in her scrapbooks suggests, Carelli was closely observing the mechanism of costs and profits in Latin American venues. Because Carelli was talking to another businessman, she lists the capacity of the theatre per order of seats, each of which had an impact on the theatre's general revenue. Her detailed figures, therefore, were not mere pedantry; they were meant to provide Riccardi with an idea of the possible scale of the business. In the same vein, the numbers she specifically indicates for the expenditure on stage refurbishment underline the financial possibilities of the Latin American market. Finally, her excitement peaks with the exclamation ‘In this way it is possible to run a theatre!’, implying the enormous potential for investment and the necessity to operate in the southern hemisphere at that very moment. As she remarks to Re Riccardi himself ‘although you cannot really complain about Italy, [you] would have found a limitless field of action here’. It is striking that Carelli closes this long message on a genuine if abrupt personal note, as she appeals to her friend's summery spirit, thus revealing the intimate side of their relationship. But the warmth of this final greeting comes across as an after-thought, from someone preoccupied with the hurly-burly of the daily life of a theatre.

In 1907 Carelli was planning ahead, almost certainly envisaging a change of direction for herself. The soprano–impresaria's long-accepted life story was initiated by her brother Augusto. In his biography, he stated that Emma reluctantly conceded to the request from her husband Walter Mocchi to take on the management of the Teatro Costanzi, a request motivated by the difficulties of supervising the Roman opera house while being constantly entangled in the organisation of other connected venues on the other side of the Atlantic. Mocchi took an interest in the entertainment industry when his chances of a future in politics had faded, in part because of his association with Carelli. Mocchi's allegiance to the extreme left-wing fringes of the socialist movement hardly suited the position of an international opera star.Footnote 49 In 1904, her husband's active involvement in the organisation of a major national strike permanently compromised Carelli's career in Italy, and prompted the soprano to attempt suicide.Footnote 50 After these hurdles (and an unsuccessful bid for a Parliamentary seat), Mocchi renounced his political aspirations and became formally his wife's agent, organising an Italian tour for her in 1906 and taking on large-scale management tasks in the form of international trusts in 1907.

According to Augusto Carelli, Mocchi put forward his request for help with the management of the Costanzi at some point around 1911, when Emma was thirty-four years old and still a busy singer. In other words, we are asked to believe that such an independent-minded woman would have agreed to end her singing career (a career she had fought for despite the considerable disadvantage of being married to a socialist agitator) and undertake a new endeavour irrespective of or even against her own desires. The narrative put forward in Carelli's biography, which has solidified over the years into accepted truth, needs to be questioned, not least because it does not square with the evidence. Carelli took an active part in the entrepreneurial operations of Mocchi well before 1911. She most likely liaised with her husband about most decisions, went over details, made introductions, fixed meetings and curated relationships, as the correspondence with Re Riccardi (not to mention her international network of connections as an opera star) also suggests. In the set of letters to the theatre impresario, brief messages informed Re Riccardi of the whereabouts of Mocchi, or fixed places and times for meetings between the three of them.Footnote 51 Of course, these documents need to be contextualised in the travelling habits of Carelli and Mocchi. Notwithstanding his considerable professional commitments as both a journalist and union representative, Mocchi often accompanied his wife during the long Latin American touring seasons. It could be inferred that the couple studied the southern operatic market on these occasions and pondered together its potential for economic exploitation in the forms of international ventures that were set in motion only a few years later.

Additional proof of Carelli's active involvement in managerial activities since at least the 1900s is indirectly provided by Paoletti. In 1909, Carlo Körner, the administrative director of the Teatro Regio in Turin, complained to the president of the Società Teatrale Internazionale (STIN, the second of Mocchi's international enterprises) that Carelli ‘was meddling in administrative matters [in lieu of Mocchi] giving advice about the order in which the productions should run; I leave to you to judge the moral benefit of such an intrusion’.Footnote 52 Because of the STIN’s inefficient planning, the Teatro Regio was experiencing serious difficulties in that season and Carelli, who was hired to sing the role of Iris in the theatre, added to the problems by being indisposed. However, the annoyance of Körner at the prima donna's ‘interference’ in matters of organisation in fact hints at the active role that Carelli took within the Mocchi/Carelli operatic business from the beginning.

To get beyond the colourless historiography which erased Carelli from all this activity, only to conveniently reintroduce her presence when required by this nonsensical narrative, we need to set the record straight by acknowledging the singer's highly unusual combination of personal attributes. Possessed of a practical and well-organised mind, intuitive, attentive to details but able to envisage the larger picture, profoundly knowledgeable of the theatre, connected internationally, determined, self-confident and certainly able to think outside the box, Carelli's personal and professional qualities made her an ideal candidate to direct the Teatro Costanzi – which remained key to the overall success of the international (and otherwise completely male-dominated) ventures revolving around it. Carelli's plan to turn herself into the impresaria of one of Italy's major houses sits in a landscape of female achievement. Recent studies on the extraordinary journeys of singers – including Caroline Miolan Carvalho, Fanny Tacchinardi-Persiani, Pauline Viardot and Adelina Patti – have redefined our understanding of women's influence on the operatic business as a whole, and research in theatre studies has revealed the contributions of women of the stage to ideas of female personality and female individuality.Footnote 53 It is high time we acknowledged that Emma Carelli, through her unwavering commitment to a life-project of her own, belongs in their illustrious company.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to the Leverhulme Trust (grant number ECF-2020-557) and the British School at Rome (Rome Award 2020), which allowed this work to come to fruition. My sincerest thanks to Lorenzo Corsini for his support and friendship during my months in Rome, Fabiola De Santis at the Biblioteca Museo Teatrale del Burcardo and Alessandra Malusardi at the Historical Archive of the Teatro dell'Opera in Rome.