The Qara Khitai dynasty, also known as the Western Liao (Xi Liao 西遼 1124–1218), is one of the fascinating yet lesser-known polities in the history of Central Asia—and not only because it preceded the rise of Chinggis Khan. Founded by Khitan refugees who escaped from North China when the Jurchen Jin 金 dynasty (1115–1234) vanquished the Khitan Liao 遼 dynasty (907–1125), the Qara Khitai soon carved out for themselves a multicultural empire in Central Asia that combined Khitan, Chinese, and Muslim elements. After concluding its expansion in 1141, the Qara Khitai empire stretched from the Oxus to the Altai mountains (namely, from present-day Uzbekistan to Western Mongolia, including Kyrgyzstan, parts of Tajikistan, South Kazakhstan, and most of Xinjiang, China). Its capital was at Balāsāghūn (modern Burana) in the Chuy valley of North Kyrgyzstan, about a day's ride from the Kök-Tash mausoleum. The Western Liao is the only Central Asian dynasty that is considered to be a legitimate Chinese dynasty by traditional Chinese historiography, and yet these Buddhist nomads from North China managed to rule their heterogeneous but mostly Muslim population in rare harmony up to the early thirteenth century. Moreover, their imperial Khitan culture, which included both Chinese and nomadic components, together with the relative stability and prosperity that they had brought to Central Asia and their religious tolerance, enabled the Qara Khitai to legitimate their rule in Central Asia without embracing Islam (Figure 1).Footnote 1

Figure 1. Map of the Qara Khitai empire, including the location of Kök-Tash. Source: Biran, The Empire of the Qara Khitai, p. 221.

The literary sources on the Qara Khitai are scattered between Chinese, Arabic, and Persian sources. Moreover, almost none of these fragmentary, and often contradictory, records is indigenous.Footnote 2 Until now, the material remains of the Qara Khitai have been scanty at best (see below): only few objects—and not a single structure—have been unequivocally associated with this powerful empire. We argue, however, that the Kök-Tash (Kyrgyz: Blue Stone) mausoleum recently unearthed in north-eastern Kyrgyzstan, and preliminarily identified as a rather unusual Muslim mausoleum,Footnote 3 is actually the first-ever discovered Qara Khitai elite tomb.

The basis for this assumption is the mausoleum's striking similarities to the tombs of the Liao dynasty in China both in terms of its architecture and burial goods, notably the typical Khitan mesh-wire burial suit, as well as its lack of any obviously Muslim features. The tomb does, however, make use of local materials, including the blue ceramics that gave it its name, thereby contributing to our understanding of this fascinating empire and its composite identity. Below we start with some background on the Liao, the Western Liao, and what has been known hitherto on Qara Khitai material culture. We then introduce the Kök-Tash mausoleum and analyse its parallels to the Liao tombs and its use of local materials. We further discuss the mausoleum's location in the Qara Khitai empire, its possible occupants, and what it adds to our understanding of this unique polity. Moreover, identifying the Kök-Tash mausoleum as a Qara Khitai tomb allows us to re-examine a number of other unusual burials excavated in the region in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and suggest that they may also belong to the Qara Khitai empire.

Background: from the Liao to the Western Liao (Qara Khitai)

The Khitans, a nomadic people of Manchurian provenance, arrived in Central Asia after more than 200 years of rule in Manchuria, Mongolia, and parts of North China as the Liao dynasty (907–1125). In North China, the Khitans created their own imperial culture which, while maintaining their indigenous traditions such as a nomadic way of life, the Khitan language, and shamanic rituals, also created new Khitan characteristics. These included two Khitan scripts, large and small, invented at the request of the Liao founder, Abaoji (阿保機, r. 907–926); intensive urbanisation, which did not prevent the royal court from maintaining its seasonal movements among its capitals throughout the Liao period; and the emergence of a unique and sophisticated material culture, the remains of which are mostly apparent in the many luxurious Khitan tombs—in terms of both architecture and contents—that have been discovered throughout the Liao territory. Moreover, the Liao empire also embraced Chinese imperial traditions, including its trappings such as reign titles, the calendar, and the Chinese language, which they used alongside Khitan (and Turkic). The Liao Khitans also set up a dual administration, in which the southern branch was responsible for administering the sedentary population (mostly Chinese and Bohai) and the northern branch, the nomadic sector. They also embraced Buddhism and lavishly patronised the universal religion, which became a common ground between the Khitans and their heterogeneous subjects, notably the Han Chinese who comprised the majority of the Liao population. The Khitans presented themselves both inside and outside their realm as the true successors of the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–906), and from the early eleventh century, they also forced the contemporaneous Han Chinese dynasty, the Song (960–1279), to acknowledge them as equal. Hence, in contrast to the traditional Chinese worldview, the Liao and Song emperors both bore the title ‘Son of Heaven’ (the Liao emperor as the northern one and his Song counterpart as the southern). In fact, the word ‘Cathay/Khatā/Kitad’, which derived from the ethnic affiliation (Khitan/Khitai) of the Liao's rulers, became the term for China not only in Mongolia, but also further west—in medieval Europe, Russia, and the Muslim world, thereby attesting to the successful identification of the Liao with China. The Liao conducted trade relations with various polities, including those of Islamic Central Asia, notably the Qarakhanids (circa 955–1213), with whom they also had marital connections.Footnote 4

In the early twelfth century, when the Liao, plagued by political crisis and global cooling, was overthrown by another wave of Manchurian invaders (the Jurchens), one Khitan prince, Yelü Dashi 耶鲁大石, chose not to submit to the new rulers. Instead, he led his few adherents westwards, hoping to return subsequently and restore the Liao in its former domains. In little more than a decade, he succeeded in setting up a new empire in Central Asia that was known there as the Qara Khitai, and in China as the Western Liao. The dynasty persisted for nearly 90 years, before finally being vanquished by the Mongols in 1218.

At its height, after defeating the Seljuq Sultan Sanjar in the famous Battle of Qatwān near Samarqand in 1141, the Qara Khitai empire stretched from the Amu Darya River in western Uzbekistan to the Altai Mountains on the Chinese-Mongolian border. Until 1175, the state's borders ran even further east into the Naiman and Yenisei Qirghiz territories on the fringes of western Mongolia. The population of this vast empire was multi-ethnic and heterogeneous. Besides the Khitans, who constituted but a small minority in their own domain, there were Turks (including Uighurs), Iranians, Mongols, and a few Han Chinese. While most of the populace was sedentary and Muslim, it had a significant nomadic component (led by the Khitans themselves), as well as flourishing Buddhist, Nestorian, and even Jewish communities.Footnote 5

In Central Asia the Khitans continued to adhere to the Liao imperial culture, including Liao-Chinese trappings (such as languages, symbols of rulership, and vassalage) and Khitan identity markers (such as language, script, shamanic rites). However, despite these similarities, and due to the impact of the new Central Asian environment, Qara Khitai rule was very different from that of the Liao. First of all, it was far less direct and centralised. Apart from its core territory, centred around the capital Balāsāghūn and including the Kök-Tash area, most of the Qara Khitai realm was administered indirectly and in a rather minimalistic way: the local dynasties—most important among them the Eastern and Western Qarakhanids and the Gaochang Uighurs—remained mainly intact, usually retaining their rulers, titles, and armies, and no permanent Qara Khitai troops were stationed in the subject territories. Liao peculiarities such as the dual administration or the five capitals were not retained, and despite the use of Chinese titles, no Chinese bureaucracy existed under the Western Liao. Instead, in a typical Inner Asian amalgamation, the Qara Khitai administration also included Turkic and Persian elements, manifested, for example, in the use of the Persian and Turkic languages in addition to Khitan and Chinese, and in the prevalence of Turkic and Persian titulature in the dynasty's prominent titles, such as tayangyu (Turkic: ‘chamberlain’) and shiḥna (Persian: ‘local governor’). Even the ruler's title, Gürkhan (‘universal khan’), was a hybrid Khitan-Turkic title.Footnote 6 Despite these influences, however, and in sharp contrast to their predecessors and successors in Central Asia, throughout their rule the Qara Khitai did not embrace Islam, the dominant religion in their new environment. Instead, they constructed their identity and legitimacy upon a unique combination of a shared nomadic political tradition and the prestige of China in general and the Liao in particular in Muslim Central Asia.Footnote 7 Recent historical and archaeological studies suggest that the Qara Khitai's Khitan character was more pronounced than has been previously thought.Footnote 8

The material culture of the Qara Khitai

Until now, the archaeological remains of the Qara Khitai have been extremely elusive. The first attempt to identify the archaeological traces of the Qara Khitai was made in the late 1930s–early 1940s by the Soviet archaeologist, Alexander N. Bernshtam (1910–1956). Bernshtam excavated at the site of Ak-Beshim (circa 50 kilometres [km] east of Bishkek), where he unearthed a Buddhist monastery and Chinese pottery roof tile ends (wadang 瓦當), along with a ceramic assemblage typical of the tenth to twelfth centuries as well as some Qarakhanid coins. Bernshtam's expedition also discovered cavities under the floors of the monastery's living quarters. These were interpreted as the remains of a heating system (kang 炕), which was typical of Northeast Asian, including Khitan, structures. Despite the fact that he found the closest parallels to the fragments of the Buddhist sculpture from Ak-Beshim in the materials of the Sui (581–617) and Tang periods, Bernshtam dated the monastery to the twelfth/beginning of the thirteenth centuries. Accordingly, he labelled the part of the town around the monastery as ‘the Khitan quarter’ and identified Ak-Beshim as the Qara Khitai capital, Balāsāghūn.Footnote 9 He also ascribed to the Qara Khitai a Buddhist statuette found near Bishkek, arguing for a renaissance of Buddhism in Central Asia under the Qara Khitai.Footnote 10 Bernshtam also attributed to the Qara Khitai Chinese roof and drip tiles that had been uncovered during the construction of the Great Chuy Canal in 1941 near the village of Alexandrovka (in the Moskovskij district of the Chuy region in North Kyrgyzstan). Operating on the assumption that the kilns that produced the tiles were also located there, he referred to Alexandrovka as a ‘major centre of Qara Khitai culture’, but did not conduct any substantial excavations at the site.Footnote 11 However, at the necropolis of Alexandrovka he did excavate several graves, which he attributed to the Qara Khitai.Footnote 12 The graves were dug in the soil and paved with mud-bricks, forming a vault. The buried faced north and the graves contained some jade objects, including belt plaques and a Chinese mirror. Lastly, Bernshtam credited the Khitans with a burial excavated near the village of Novotroitskoe (modern Shopokov, 216 km north-west of Kochkor and 97 north-west of Ak-Beshim). The grave was built of baked bricks and had a vault, covered with a small mound. It contained human and horse skeletons, a vessel of the Song dynasty (960–1279), and two jade rings. Unusually, the human was buried in a seated position with the head facing in the southern direction.Footnote 13

Bernshtam's excavations were interrupted by the Second World War and have been mostly ignored since the early 1960s, not least due to the intensification of the Sino-Soviet dispute (1956–1966) and later tensions between China and the former Soviet Union, which led to the downgrading (if not fully ignoring) of Chinese influence in Kyrgyzstan.Footnote 14 Later excavations and post-Soviet publications, however, refuted most of Bernshtam's conclusions on scientific and not political grounds. Notably, the monastery was dated to the beginning of the eighth century, although it continued to function until the eleventh. Ak-Beshim was convincingly identified as Suyab (Chinese: Suiye 碎葉), the capital of the Western Turks (circa 581–657) and their successors, the Turgesh (699–766). The city was under Tang rule from 679, served as the seat of one of the Tang dynasty's four garrisons in 692–719, and was later controlled indirectly by the Tang as the Turgesh's overlords. This easily explains the Chinese features unearthed there, which had no connection to the Qara Khitai.Footnote 15 We should also mention two graves in which the deceased were buried in a seated position that were recently excavated in the Chuy Valley and can be dated approximately to the twelfth century.Footnote 16 Yet these graves are not typical of the Liao dynasty, nor do they have any attested connection to the Qara Khitai.

As was recently observed by Asan Torgoev, it is nearly impossible to identify ‘purely’ Qara Khitai monuments. This is mainly because on many sites it is very difficult to identify layers dated to the twelfth century as these are often completely absent.Footnote 17 However, an important discovery was a single burial excavated by Karl Bajpakov in 1971 on the left bank of the Talgar River near Almaty.Footnote 18 The grave was dug in the soil, oriented towards the north, and, just like the Alexandrovka burials, it also contained a jade belt set, which can be dated to the thirteenth century.Footnote 19 Torgoev concluded that these burials at Alexandrovka and on the Talgar River, which are different from contemporaneous Qarakhanid graves, could belong to the Qara-Khitai.Footnote 20 However, they could also be attributed to East Asians (such as Khitans, Mongols, Jurchens, Chinese) who arrived in the region during or after Chinggis Khan's campaigns in the early thirteenth century (1218–1225).

In recent decades, however, numerous metal objects allegedly connected with the Qara Khitai have turned up on various websites (such as https://www.zeno.ru/). These are mainly chance surface finds or objects discovered by detectorists. They include coins and inscribed metal plaques, which probably served as seals or paizas (tablets of authority, a kind of diplomatic passport).Footnote 21 The findspots of most of these objects seem to have been the eastern part of the Chuy Valley. Few of these artefacts were convincingly attributed to the Qara Khitai,Footnote 22 but for many of them the lack of context means that they cannot be unequivocally associated with the Qara Khitai, as some of these objects could be Tang or Song paraphernalia, or even Liao artefacts individually imported to Central Asia from China through trade or diplomacy.Footnote 23 The same reservation is also true for the unique Khitan large-script book, unearthed in Kyrgyzstan in the 1950s. Originally classified as a Jurchen work, it gathered dust in the Hermitage's cellars for more than half a century, until the Russian philologist Vyacheslav Zaytsev rediscovered it in 2010, identifying it as Khitan. This intriguing document, bound in a Muslim fashion and wrapped in a leather cover, is the only extant Khitan book (in any script) and by far the longest example of any Khitan text. Zaytsev suggested that it was composed of several distinct compilations, one of which is the Khitan ‘veritable records’ (shilu 實 錄, the records subsequently used for compiling a dynastic history) of the nine Liao emperors (up to 1125), while another is a collection of corresponding biographies; the rest are still unidentified. All of these, however, are still undeciphered.Footnote 24

We should also mention silver belt plaques with floral and zoomorphic designs that were found before 1917 in the Kochkor Valley and are kept in the Hermitage Museum in Saint-Petersburg.Footnote 25 Torgoev suggested that the belt might have belonged to the Qara Khitai.Footnote 26 Recently, some types of arrowheads, which appeared in the Tian Shan region in the twelfth century, were also attributed to the Khitans.Footnote 27

These objects notwithstanding, however, up until now no structure or monument has been indisputably associated with the Qara Khitai. Their domination in Central Asia was discussed exclusively on the basis of the meagre literary sources (if any at all), and the material culture from this era was routinely ascribed to their vassals, the Qarakhanids, without even mentioning the name of the Qara Khitai.Footnote 28 Since the Qarakhanids had adopted Islam by the late tenth century, this material culture was also automatically defined as Muslim.

The mausoleum

The Kök-Tash underground tomb was uncovered in the Kochkor valley in modern Kyrgyzstan near the village of Kum-Döbö (Figure 2).Footnote 29 The excavations were carried out in 2017–2018 by a team from the Kyrgyz-Turkish Manas University headed by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov. After the excavations of the main structure had been completed, the excavators published a short note in English in 2018 and two preliminary reports in Russian in 2019.Footnote 30

Figure 2. Map of the region showing the sites mentioned in the article. Source: Drawing by Valery Kolchenko on a Google Earth map.

The tomb was accidentally discovered by locals during the construction of a silage pit in 1988, when parts of the dome and sections of the walls were destroyed. It was preliminarily reviewed in 1991, but due to the lack of funding was not excavated. In 2010–2011, the site suffered further extensive damage when one of the local villagers conducted an illegal excavation using heavy machinery. It was looted again in 2015. All this promoted rescue excavations that began in 2017. Despite these setbacks, however, the findings are impressive.

The mausoleum is an underground tomb: it was constructed in a previously dug pit (Figure 3). After the structure was completed, the space between the tomb's inner walls and the walls of the pit was filled with a setting of brick fragments, creating a facade with an irregular surface (Figure 4).

Figure 3. General view of the Kök-Tash mausoleum during excavations. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 4. A setting of brick fragments near the entrance to the tomb. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

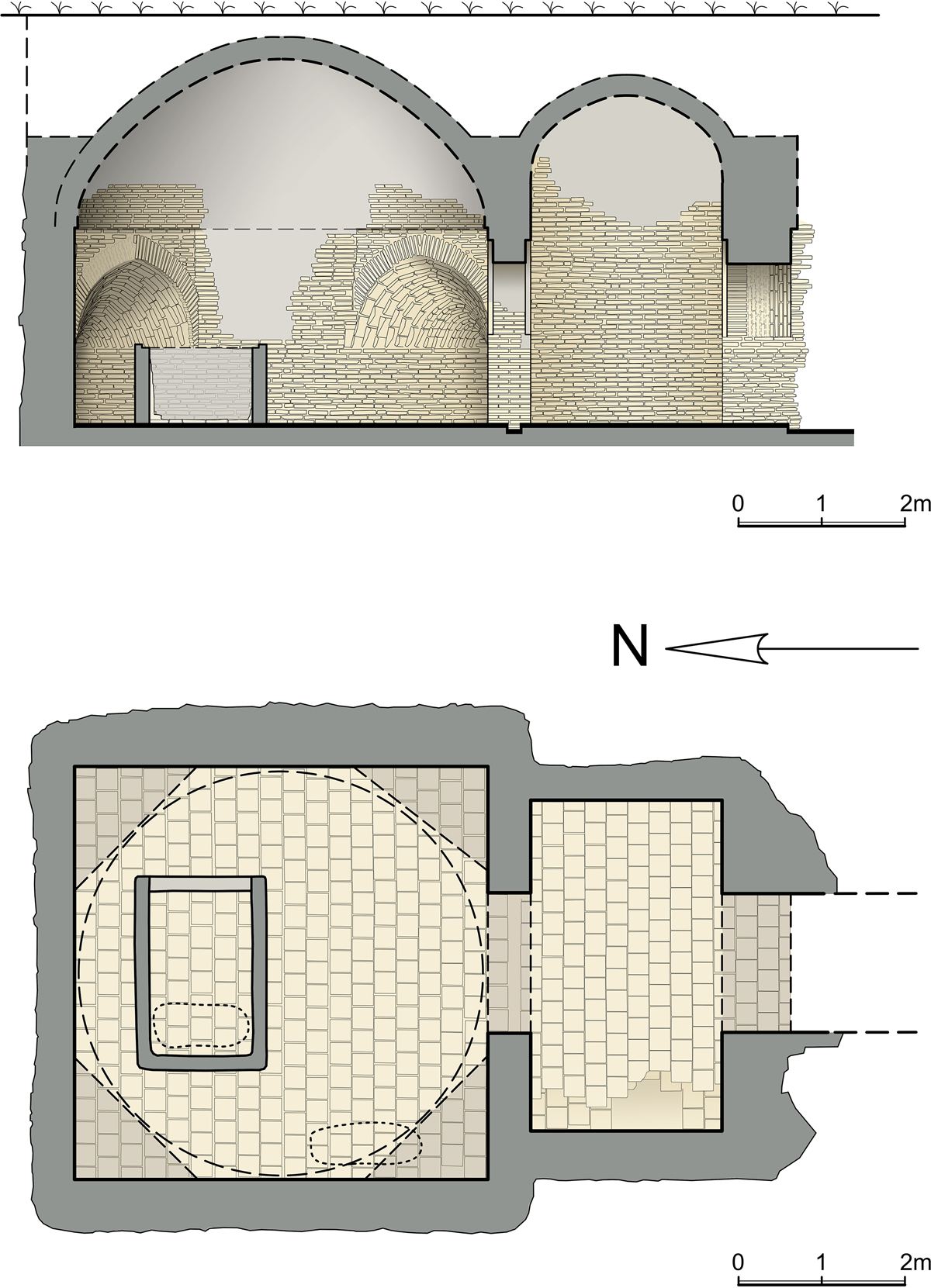

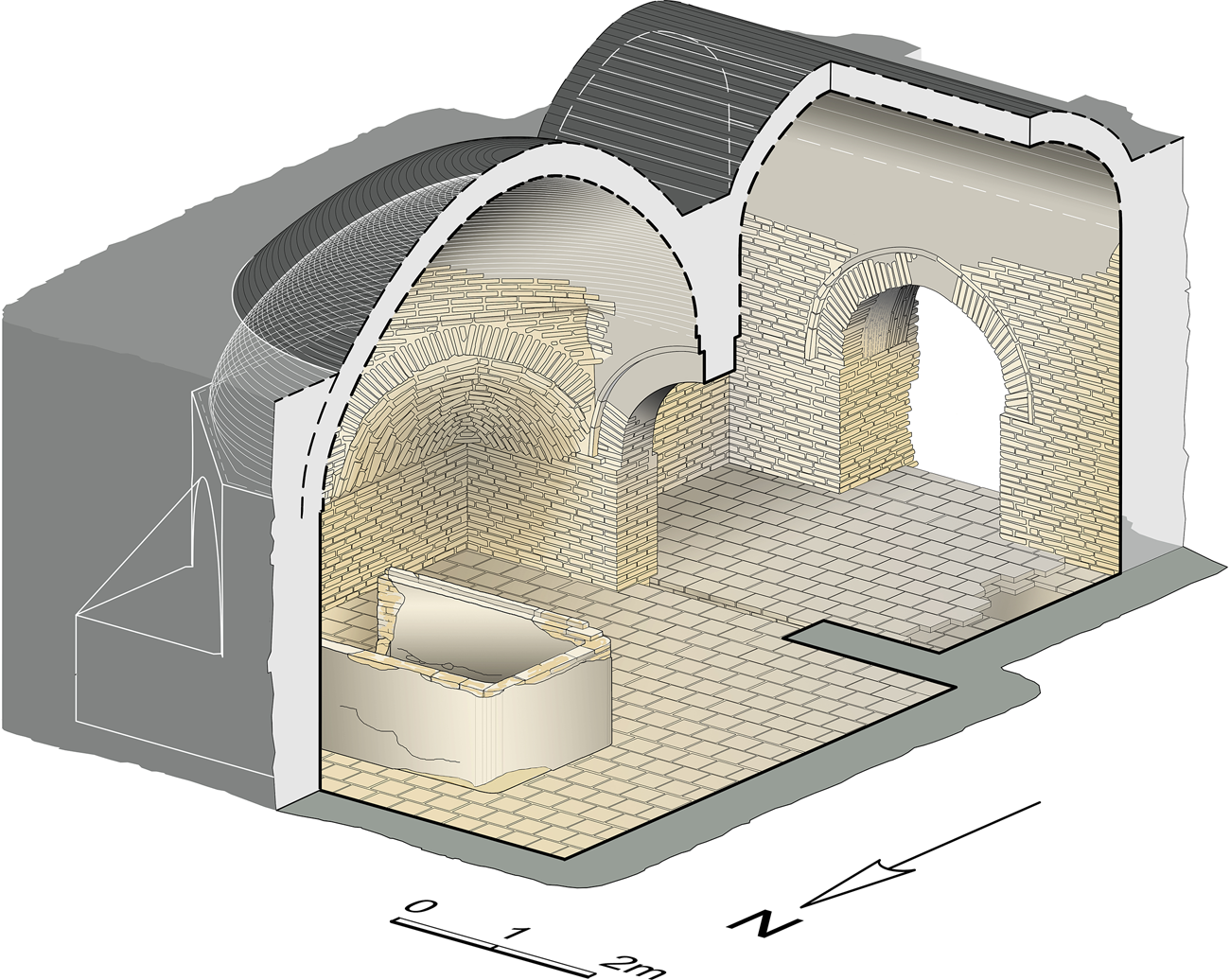

The Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey conducted by specialists from Moscow in 2017 suggested that the entrance to the tomb was via a stepped walkway (dromos) that was not excavated. The Kök-Tash mausoleum consists of two adjacent chambers, a smaller rectangular one (2.4 x 4 metres [m]) and a larger square room (6.3 x 6.3 m) connected by an arched passage (Figures 5–7). The structure is perfectly situated on the south-north axis, and the entrance is from the south.

Figure 5. Plan and section of the Kök-Tash mausoleum. Source: Drawing by Elena Bouklaeva.

Figure 6. 3D-reconstruction of the Kök-Tash mausoleum. Source: Drawing by Elena Bouklaeva.

Figure 7. An arched passage leading from the antechamber to the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

It is built of baked bricks and the second, square room was covered with a dome based on an octagon formed by squinches (Figures 8–9).Footnote 31 Its diameter was 5.2 m. The floor of both chambers is paved with two layers of baked brick (Figure 10). Six burned wooden beams and many additional fragments of burned wood were found in the main chamber (Figure 11). The preserved beams have a round section and a diameter of 10 centimetres (cm).

Figure 8. Remains of the foundation of the dome in the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 9. North-western squinch. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 10. Floor paved with two layers of backed brick in the antechamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 11. Burned beams in situ, south-eastern corner of the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

In the centre of the northern half of the second chamber, close to the rear wall, a coffin of baked brick was built directly on the floor (length 238–240 cm, width 156–169 cm, height 72–96 cm) (Figure 12). The channel in the upper part of the coffin indicates that it had a lid, but no traces of it remain. It was probably made of wood, since the brickwork is too thin to support a heavy stone lid.

Figure 12. The coffin in the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

The remains of three individuals were found in the tomb. All of them were disturbed and removed from their original resting places.Footnote 32 Inside the coffin, the upper part of a female skeleton was uncovered. The skin was partially preserved and completely covered with green powder. Bones from the lower part of the same skeleton were found near the western wall of the main room. The thighbone and the shinbone were wrapped in bronze or copper wire mesh (Figures 13–16).Footnote 33 The green powder unambiguously indicates that the same wire mesh also covered the upper part of the female skeleton. Along the western wall of the burial chamber and above the lower part of the female skeleton, a male skeleton in good anatomical order was found (Figure 17).Footnote 34 Its bones were also covered with green powder, and it is clear that it was also wrapped in bronze wire mesh which had oxidised. Small fragments of bronze wire were discovered in various parts of the tomb. Thus it seems safe to assume that the couple, who were probably husband and wife, were originally buried together inside the coffin. It seems that the grave was first disturbed shortly after the burial, when the male body and the lower part of the female body were thrown out of the coffin and left lying along the western wall. In addition, the skull of an adolescent was found near the northern wall of the burial chamber, 90–95 cm above the floor, and several bones belonging to the same skeleton were uncovered outside the tomb, near the entrance. The C-14 analyses of the adolescent's skull gave a range of 1264–1300.Footnote 35 However, because no additional coffin or other installation was placed in the burial chamber, and the majority of the bones were found outside and were not wrapped in wire mesh, it seems that the remains of the adolescent are unrelated to those of the couple and belong to a later period.

Figure 13. Bones wrapped in copper/bronze wire mesh from the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 14. Bones wrapped in copper/bronze wire mesh from the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 15. Bones wrapped in copper/bronze wire mesh from the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 16. Bones wrapped in copper/bronze wire mesh from the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 17. Male skeleton in situ, main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

In addition to the human remains, several animal bones and a dog skeleton were discovered inside the tomb, together with numerous other finds, including fragments of ceramic and glass vessels, metal, stone, gypsum, and jade objects. Most of them were uncovered at the height of one metre above floor level, and therefore probably belong to the period after the construction of the tomb, when it was gradually filled with soil. In some places, the soil inside the tomb was redeposited several times, and plastic bottles and bags were found even in the lower layers. Additional evidence of disturbance is the fact that only one complete vessel could be assembled from the hundreds of pottery sherds found in the tomb. Therefore, it seems that only a few finds, uncovered directly on the floor, can be considered to be found in situ and belonging to the grave goods of the original burial.

Among these objects are 12 small plates made of jade, which were placed on the floor in stacks of two to four pieces near the arch of the entrance to the burial chamber (Figures 18–19). At a short distance to the north of these plates, two bronze mirrors were uncovered (Figure 20). They have a diameter of 23.5 cm and one has a projection in the centre with a hole, probably intended for a loop.

Figure 18. 12 small jade plates in situ, main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 19. Drawing of the jade plates. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Figure 20. Bronze mirror from the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

Another remarkable find in the tomb is fragments of blue glazed pottery. The excavators reassembled a low, four-legged table (height 21 cm, length 53 cm, width 46.5 cm) (Figure 21), but numerous additional fragments and the find of another, fifth leg indicates that originally at least two such tables were placed in the tomb.

Figure 21. Reconstruction of the glazed ceramic table from the main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

One badly preserved, unidentified Chaghadaid coin (thirteenth–fourteenth centuries) was found under the male skeleton. Since the skeleton was removed from the burial coffin, the coin probably belongs to a later period, when the burial chamber was no longer in use. Thus, together with the date obtained by the C-14 analysis of the adolescent's skull, the coin only gives us a terminus ante quem, allowing us to conclude that the Kök-Tash tomb was built not later than the thirteenth century.

Discussion

In their preliminary report, Tabaldiev and Akmatov concluded that the Kök-Tash mausoleum is a Muslim tomb that should be dated to the eleventh–thirteenth centuries.Footnote 36 However, the tomb includes nothing that is specifically Muslim and, moreover, some of its features are exceptional and do not find ready parallels in contemporaneous Central Asian funerary structures.Footnote 37 Notably, underground tombs are extremely rare in medieval Central Asia, and none has a two-chamber structure. A floor paved with two layers of brick is also unknown in Muslim Central Asia. Furthermore, the burial arrangements are as atypical as the architectural ones: Muslims are supposed to be buried in the ground, without coffins and grave goods, and certainly burial in a coffin built on the floor and the coffin's east-west orientation are highly unusual. Moreover, a burial of a couple (male and female) together in the same coffin or grave is unknown in Muslim Central Asia.Footnote 38

In contrast, however, these and other features of the Kök-Tash mausoleum closely resemble the underground tombs of the Khitan Liao empire, whose refugees established the Qara Khitai or Western Liao dynasty. Based on these similarities, we argue that the Kök-Tash mausoleum is actually a Qara Khitai elite tomb, the first to have come to light so far.

An impressive number of several thousands of Liao burials are known today and new tombs continue to be discovered in the Khitan-ruled territories in north and north-east China. Most of the tombs were unearthed in the modern provinces of Liaoning and Inner Mongolia, but also in Hebei, Shanxi, Tianjin, Heilongjiang, and Jilin. With such an abundance of material—combined with the magnificent findings inside the tombs—it comes as no surprise that the architecture of the Liao tombs, their grave goods, and Liao burial customs have been extensively studied.Footnote 39

The Kök-Tash mausoleum clearly fits into the Liao ‘house-shaped tomb’ (屋式墓 wushimu) type, according to Dong Xinlin's classification.Footnote 40 This is the most common type of Liao burial. It consists of a passageway, a portal, and a fairly large chamber (2 m or larger) or chambers, with a domed ceiling. Variants of this type include the number of chambers along the main axis as well as the existence and number of side rooms, and also the shape of the chambers, which can be round or oval, square, rectangular or polygonal but usually octagonal or hexagonal.Footnote 41 Kök-Tash's layout of two central rooms, with one smaller antechamber leading into the main burial chamber, is characteristic of many Liao elite tombs. Rectangular rooms, however, are less common in Liao tombs, the most popular being round and octagonal shapes.Footnote 42 Side rooms, which often characterise Khitan aristocratic burials, are missing at Kök-Tash. Its rectangular double-chamber layout without the side rooms is typical of the high-ranked Liao non-Khitan (that is, Han Chinese) elite. These Han Chinese aristocrats usually rose to prominence by statecraft and through military channels, but consolidated power through intermarriage with Khitan imperial and consort clans, and in some cases even received the honorary Khitan royal surname ‘Yelü’, so they were quite ‘Khitanised’. While many held hereditary prerogatives and their families served the Khitans for generations, others (what Cheng calls ‘non-hereditary elites’) rose to prominence by other means, mainly their skills or wealth, and only retained their privileges for three generations or fewer.Footnote 43 Among these non-Khitan hereditary elite tombs, Cheng identified seven out of 21 which had two rooms. All of them belonged to the upper rank of the Liao Han hereditary elites, of the families of Han 韓 and Geng 耿 . Three of them—those of the Geng family (dated to 949, 1020, and 1026, and located at Guyinzi Village, Chaoyang City, Liaoning, in the Liao's Central Capital circuit)—were rectangular and without side rooms, and Cheng defines them as manifesting a high degree of Khitanisation, that is, they emulated the tombs of the Khitan elites.Footnote 44 The closest analogies to the Kök-Tash architectural plan are the tombs of Geng Zhixin 耿知新Footnote 45 and Zhang Shiqing 張世卿 (tomb no. 1) from Xuanhua, Hebei province (in the Liao's Western Capital circuit), dated to 1116 ce and famous for its remarkable murals (Figure 22).Footnote 46 Zhang Shiqing, a non-hereditary aristocrat, made his fortune in agriculture and was granted an official title after he had donated grain for famine relief (that is, he bought his way into the administration). He continued to advance in the Liao Southern administration, becoming a middle-ranking official. He was a devout Buddhist and was close to the last Liao emperor, Tianzuo (天祚, r. 1101–1125), who enjoyed Zhang's lavish hospitality during Buddhist feasts. By the time of his death, his grandson was married to a woman of the Yelü clan.Footnote 47 Zhang's tomb was constructed in a style emulating the burials of the Liao Khitan aristocracy, yet its content and burial practices were typical of the tradition of the Liao Han-Chinese tombs, containing many Buddhist features and excluding Khitan characteristics.Footnote 48

Figure 22. Plan of Zhang Shiqing's tomb (M1), Xuanhua, Hebei province. Source: Li Qingquan, Xuanhua Liao mu, vol. I, p.193.

The wooden beams and iron nails that were found inside the Kök-Tash burial chamberFootnote 49 could be part of a door. However, many Liao tombs contained wooden architectural elements in the main burial chambers. In some of them, an entire wooden interior tent (muzhang 木帳) was built, to create a kind of inner wooden envelope inside a burial chamber made of brick. This wooden interior tent is specific to the Liao dynasty and is unattested earlier in Chinese architecture.Footnote 50 Since only beams were found in Kök-Tash, it is clear that the entire burial chamber was not faced with wood. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that the beams were used as supports for some kind of structure above the burial coffin.

The entrance to Liao tombs is usually situated in the south-eastern direction, but the orientation of the Liao Khitan tombs is almost never as accurately north-south as in the Kök-Tash tomb. However, the orientation of the entrance to the south is typical for Liao Han Chinese graves.Footnote 51

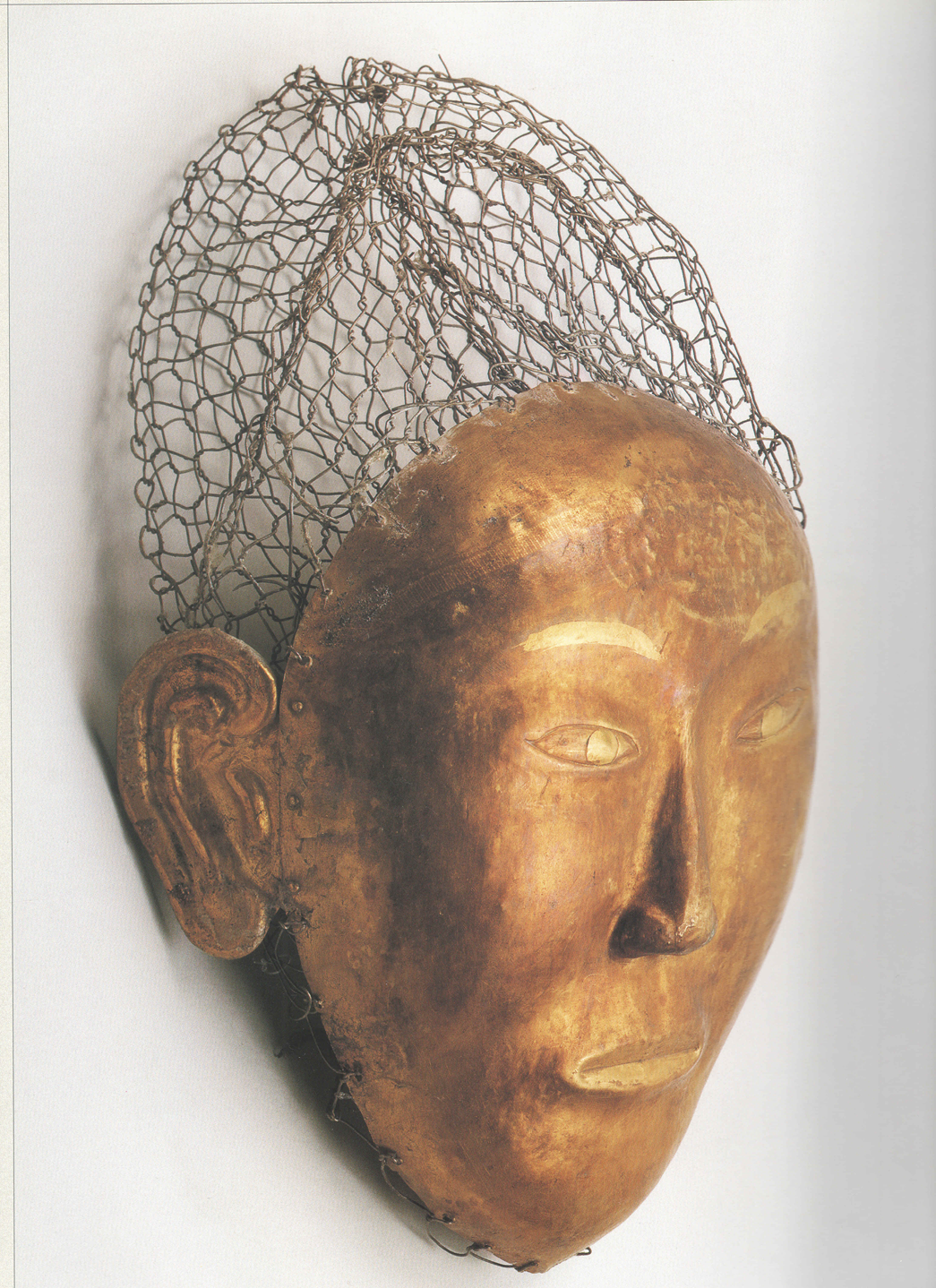

Much attention has been paid to the possible correlation between certain architectural features of the tombs, the objects placed in them, and details of the burial rites with the alleged ethnic identity of the buried, either Khitan or Han Chinese.Footnote 52 Notably, distinctively Khitan mortuary customs included the entombment of entire bodies clothed with metal burial attire, consisting of a body netting of wire mesh suits and crowns, as well as face masks (Figures 23–24), while in Han Chinese burials the deceased were cremated, although a human manikin of wood or straw was sometimes placed in the tomb.Footnote 53

Figure 23. Mesh suit from the tomb of Princess Chen (d. 1018), Naimen Banner, Zhelimu League, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Source: Zhongguo lishi bowuguan, Nei Menggu Zizhiqu wenhua ting 中囯历史愽 物馆, 内蒙古自治区文化厅 (ed.), Qidan wang chao: Nei Menggu Liao dai wenwu jinghua. 契丹王朝 : 内蒙古辽代文物精华 (Beijing, 2002), p. 29.

Figure 24. Golden mask from the tomb of Princess Chen. Source: Zhongguo lishi bowuguan, Nei Menggu Zizhiqu wenhua ting (ed.), Qidan wang chao, p. 38.

The wire mesh used to cover the deceased's entire body from head to toe, which we find on the couple buried at Kök-Tash, was thus a distinctive feature of the burial practices of the Liao Khitan elite throughout the empire's existence.Footnote 54 The origins and meaning of this Khitan custom have been much debated and should not concern us here.Footnote 55 What is important for our purposes is the preservation of this distinctive Khitan custom in Central Asia, which testifies to its continuation under the Qara Khitai elite.Footnote 56 Since the green powder also covered the front of the heads of the Kök-Tash couple (Figure 25), it seems likely that their faces were covered with copper or bronze masks that have since disappeared. Covering the faces of the deceased with metal masks, as part of the wire-mesh attire, is typical of the Liao.Footnote 57

Figure 25. Skull with traces of green power in situ, main burial chamber. Source: Photo by Kubatbek Tabaldiev and Kunbolot Akmatov.

The quantity of the attire elements and the metal used reflected the status of the buried. The masks and the body netting of members of the Liao imperial and consort clans were made of gold and silver, while people of lower status had fewer pieces, which were made of bronze.Footnote 58 Caution is necessary here, since the Liao tradition was transferred to a different geographical and cultural environment. However, in the context of the known Liao tombs, the simple layout of the Kök-Tash mausoleum (namely the absence of side rooms) and the bronze or copper wire mesh (rather than gold or silver) may indicate that the Kök-Tash couple did not belong to the imperial family of the Qara Khitai, but were, rather, members of the elite.

The burial of married couples together is typical for the Liao, for both Khitan and Han elites. This further supports the suggestion that the individuals buried in the Kök-Tash tomb were husband and wife. In Liao tombs, corpses were often placed in wooden or stone coffins,Footnote 59 which were usually located closer to the rear wall of the main chamber than to the entrance,Footnote 60 exactly as at Kök-Tash.

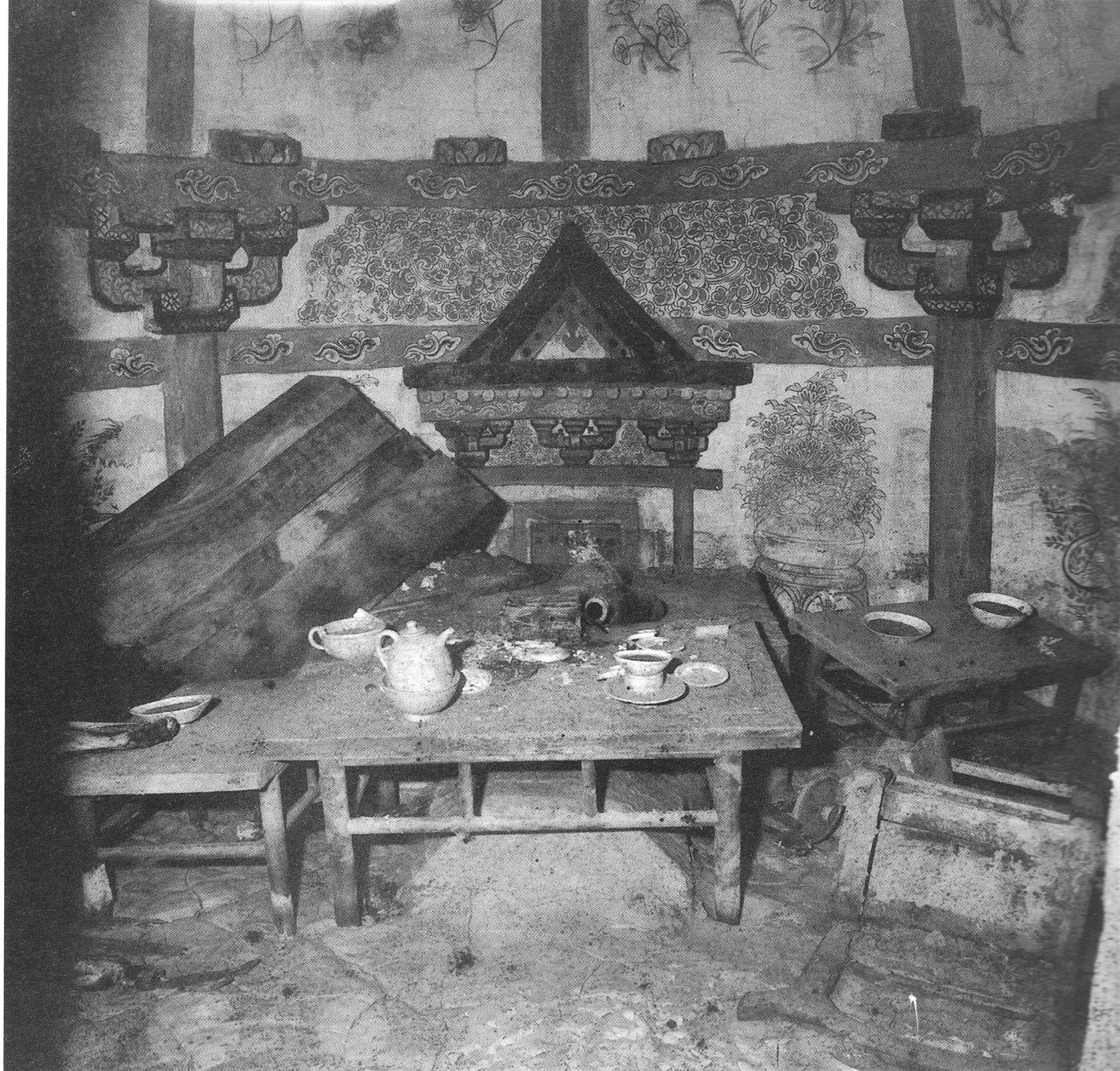

Mirrors and small ceramic tables found in Kök-Tash also find parallels in the Liao tombs. The latter often contained a number of mirrors, in both Khitan and Han-Chinese elite tombs.Footnote 61 In several elite Khitan tombs, mirrors were hung from the walls or ceiling.Footnote 62 Especially noteworthy is a large, undecorated mirror from the tomb of the Princess Chen (d. 1018) and her husband, which was suspended from the wall in the burial chamber with a silver cord inserted in the boss of the mirror.Footnote 63 It bears a close resemblance to the Kök-Tash mirror, and it seems safe to assume that the latter was also suspended from the ceiling or the wall, while the second mirror from the tomb, without a boss, was placed somewhere in the room. Kinoshita suggested that the use of mirrors in Liao tombs imitates the arrangement of mirrors in pagodas and might have been employed by the Khitans to create an auspicious, Buddhist-inspired ‘environment of paradise’.Footnote 64

The blue glazed ceramic tables seem to be almost identical in shape (but larger in size) to the turquoise glazed table (36 x 40, h. 14 cm) found in 1951 at Taraz (Kazakhstan) (Figure 26).Footnote 65 According to the records of the Taraz Regional Museum, this table was accidentally discovered during gardening, in an underground tomb built of baked bricks. It was accompanied by several glazed vessels, a jar, three plates, a small bowl, two bronze ornamented mirrors, and a turquoise glazed ceramic box with removable lid (Figures 27–28). Based on the ceramics, the tomb was dated to the thirteenth century. Unfortunately, since it did not come from a controlled excavation, this tomb was never properly studied. Senigova, who reproduced drawings of several objects from this tomb, referred to it as a ‘female burial’.Footnote 66 She also describes the bronze mirrors (6.5 and 8 cm in diameter) and notes that they have a semi-circular projection in the centre with a hole for suspension, exactly like the Kök-Tash mirror.Footnote 67 Most importantly, Senigova attests that the box from the burial contained cremated remains.Footnote 68 This definitely rules out the possibility that the buried woman was Muslim. Since the ashes and bones were put in the box, apparently specifically manufactured for this purpose, probably some of the vessels were originally placed on the table. After the discovery of the Kök-Tash tomb, and given the similarities of the two monuments (the offering table, the grave goods, the underground tomb, and the non-Muslim burial), we can also tentatively attribute this female burial from Taraz to the Qara Khitai. The central position of Taraz (known as Talās in the medieval period) in the Qara Khitai realm—at the north-western border of their Central territory and the headquarters of a notable general who headed their western campaigns—supports this identification.Footnote 69

Figure 26. Glazed ceramic table from a female burial at Taraz. Source: Baipakov et al., Treasure of Ancient and Medieval Taraz, p. 181.

Figure 27. A glazed ceramic box with removable lid from a female burial at Taraz. Source: Photo courtesy of Sejtzhan Il'yas and Aisha Begalieva.

Figure 28. A glazed ceramic box with removable lid from a female burial at Taraz. Source: Photo courtesy of Sejtzhan Il'yas and Aisha Begalieva.

These strikingly similar ceramic tables from Kök-Tash and Taraz appear to be a local, Qara Khitai version of offering/altar table(s), which were often placed in Liao tombs, especially those of the Liao Han Chinese. These offering tables were part of the ‘sacrifice of repose’ intended to provide the souls of the deceased with a final banquet, and often connected with Buddhist beliefs (Figure 29).Footnote 70 The jade plates that were probably placed on the table seem to be related to this banquet, which was so essential for the Chinese perceptions of burial that Tackett has defined it as ‘constitut[ing] good evidence of Chinese cultural influence’.Footnote 71 The presence of a large number of vessels in a burial is atypical for Central Asia. Yet jade was a famous product of the Khotan region, which was subject to the Qara Khitai, and a commodity coveted by and exported to both the Liao and the Song dynasties by the Qarakhanids in the pre-Qara Khitai period.Footnote 72 Interestingly, one of the features that we suggest identifying as non-elite Qara Khitai graves is the presence of burial goods made of jade (see below). The combination of ‘Khitan’ and ‘Chinese’ characteristics at the Kök-Tash tomb corresponds to the category of ‘hybrid’ tombs as defined by Tackett.Footnote 73 Notably, an offering table is one of the Chinese practices adopted by the Khitans buried in such ‘hybrid’ tombs.Footnote 74

Figure 29. ‘Sacrifice of repose’ from the tomb of Zhang Wenzao (M7) at Xuanhua, Hebei province. Source: Li Qingquan, Xuanhua Liaomu, vol. II, p. 34.

The Central Asian element manifests itself in the building techniques and use of local materials. This is also true for the material used for the offering table—blue ceramics. Blue, the colour of the East in the Chinese and Turkic world, might have represented the Qara Khitai's connection to the East or simply local taste. In twelfth-century Transoxania, under the Qara Khitai, blue glazed ceramics were widespread, especially in Samarqand and Bukhara, where turquoise glazed ceramics also became numerous and mass-produced.Footnote 75 Another local element is the baked bricks; their size is identical to those used in the eleventh-century minaret in Burana (Balāsāghūn), the Qara Khitai capital.Footnote 76 Thus the Western Liao elite used local Central Asian raw materials to reconstruct the funerary culture typical of the Liao empire in North China.

Who was the couple buried in the Kök Tash mausoleum? They were subjects of the Qara Khitai empire, likely of Khitan origin (or perhaps Khitanised Chinese), and possibly Buddhists. They were part of the elite, but probably not of its higher echelons or of the Qara Khitai royal family, so merely the local elite.

This assumption fits well with the location of the mausoleum. Three to four kms from the Kök-Tash tomb, next to the modern village of Kum-Döbö, there is a large site (400 x 870 m) usually identified as medieval Quchqār Bāshī or Qochnār Bāshi. The city is mentioned by Maḥmūd Kāshgharī (fl. 1072) in his Compendium of the Turkic Dialects (Dīwān Lughāt al- Turk). He said that the meaning of ‘Qochnār’ is a ram, that the city was located near the Siḍin lake, and that a certain Zānbi pass was located between Kochnar and Balāsāghūn (identified as the current Shamsi pass). Moreover, it was mentioned by Kāshgharī in his world map (centred in Balāsāghūn), thereby suggesting that it had at least a certain regional importance.Footnote 77 The city (as Quchqār) is mentioned once by the eleventh-century Ghaznavid historian Gardīzī as the death site of the Qarakhanid ruler Ilig Khan (d. 922), who passed away on his way back from Samarqand to Turkestan.Footnote 78 Yet we were unable to find any other reference to the city in the twelfth–thirteenth centuries, despite the abundance of biographical and geographical works, most notably the Kitāb al-Ansāb (Book of Genealogies) of al-Samʿānī (d. 1166), who spent a few years in Qara Khitai-ruled Transoxania, and Yāqūt's (d. 1229) comprehensive Muʿjam al-Buldān (Dictionary of Countries). This absence suggests that in the twelfth-century, Quchqār was not home to a significant scholarly Muslim population. The name (as Quḥqār) reappears in the Timurid chronicles, when describing Tamerlane's raids into Moghulistan (the eastern Chaghadaid realm, roughly equivalent to the Qara Khitai empire minus Transoxania) in the 1370s–1380s. Apart from a certain strategic importance, not much information can be gleaned from these later sources.Footnote 79

In the twelfth century, the city belonged to the central territory of the Qara Khitai, the part of their realm over which they ruled directly, as opposed to most of their empire where subject rulers (notably the Eastern and Western Qarakhanids and the Gaochang Uighurs) retained their authority. Most of the Khitans and those who accompanied them in their migration from northern China resided in the central territory, which was located around the capital, Balāsāghūn.Footnote 80 Moreover, Quchqār was on the road leading from the Qara Khitai's winter pasture around the capital to one of their summer pastures on the north-western slopes of the Tian Shan above the Issyq Kul, passing through Barskhān (modern Karakol) and sometimes going all the way to the outskirts of Kashgar (China).Footnote 81

Another feature that seems to provide further support for the settlement of the Qara Khitai in the Kochkor region is the underground burials that were unearthed in the nineteenth century, but until now were never connected to the Qara Khitai. In 1891, A. M. Fetisov explored several underground burials in the area of Keske-Tash in the same Kochkor valley, which were disturbed by the locals. Overall, he recorded five enclosures made of rammed earth with five to six large stones placed in the corners and with an entrance from the east. One burial, labelled ‘A’ had already been completely robbed when Fetisov arrived, while burial ‘B’ was partially disturbed. This allowed him to examine the general setting and the construction of the burials. From the entrance in the enclosure, there was a descending ramp leading to the floor of a completely underground structure made of baked brick. After cleaning the entrance, Fetisov realised that the ceiling of the structure had collapsed and further excavations would be dangerous. Therefore, he turned to the undisturbed enclosure ‘C’ (20 x 10 m). Its round burial chamber (diameter 2.33 m) was situated more than 1 m below the surface level. It was covered by a ‘dome-like vault’ 3.42 m high. The floor inside the tomb and its walls were plastered. Near the rear wall of the burial chamber there was a brick coffin (1 x 0.5 m and 3.42 m high) that contained ashes of the deceased. Fetisov recorded that enclosures ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’ were arranged along one diagonal line at a distance of 5–10 m from one another. Enclosure ‘E’ was the largest (22 x 14 m) and was also situated at a distance of 75–80 m from the rest. It had also been partially robbed and had collapsed as a result.Footnote 82

Such underground burial constructions made of mud bricks are not characteristic of the region. Indeed, after Fetisov's excavations, nothing similar was encountered in the region, and scholars did not suggest any convenient interpretations for these Keske-Tash burials, although it was clear that they should be dated to the medieval period.Footnote 83

In the same year of 1891, Fetisov also excavated a number of burials at Orto-Tokoi in the eastern Kochkor valley.Footnote 84 The burials were in stone boxes at a depth of 2 m and oriented towards the north. Burial goods included a Chinese mirror, jade jewellery, and a belt set. In two graves, a wooden plate, which contained sheep bones, was placed to the right of the skull.Footnote 85

Now, after the discovery of the Kök-Tash mausoleum, which has some similar basic features, it seems reasonable to suggest that the burials excavated by Fetisov belonged to non-elite Qara Khitai. If this is indeed true, then the first Qara Khitai constructions were already uncovered almost 130 years ago, but it is only now that we can recognise them as such. The burials excavated by Bernshtam at Alexandrovka and by Bajpakov near Almaty may also have belonged to non-elite Qara Khitai, while the female burial from Taraz unearthed in 1951, with its cremation box and offering table, may even have been another elite Qara Khitai tomb. Features that are shared by most of these graves include underground burial, graves paved with brick (sometimes vaulted), northern orientation, the presence of grave goods made of jade, and Chinese mirrors.

We must, however, remember that the troops of Chinggis Khan who subjugated the Qara Khitai in 1218 and the Khwārazm Shāh's empire soon afterwards (1219–1225) included quite a few Khitans and northern Chinese who had joined the Mongols at an early stage or were recruited after the conquest of the Jin capital, Yanjing, in 1215. Moreover, after their conquest of Transoxania, the Mongols transferred numerous Chinese, Khitan, and Tangut farmers to the region, and used Khitans from North China as administrators, for example, in Bukhara.Footnote 86 Thus, some of the other tombs might have belonged to East Asians (Khitans, Chinese, Jurchens, Mongols) who arrived in Central Asia after the Qara Khitai's collapse. Unlike all these other tombs, however, the presence of the wire mesh suit in the Kök-Tash mausoleum firmly supports its identification as a Qara Khitai tomb.

Conclusions

The architecture and content of the Kök-Tash mausoleum finds close parallels in the underground tombs of the Liao dynasty unearthed in North China. Conclusive evidence is provided by the use of wire mesh attire on the Kök-Tash couple. This is a custom unique to the Liao Khitan elite and is unattested elsewhere in this period. Some features, like the double-layered floors and the inner wooden architectural elements, are also unique to Khitan graves and not found elsewhere. Another rite specific to the Liao tombs is the hanging of bronze mirrors in the burial chamber. Moreover, additional details of the burial customs attested at Kök-Tash such as double (male and female) burial in a brick coffin placed near the innermost wall, as well as grave goods and offering tables, also correspond to the rites of the Liao elite tombs. Needless to say, these characteristics do not fit Muslim burials.

The Kök-Tash tomb combines features typical of the Liao elite's Khitan and Han tombs. The features more typical of the Khitan burials include inhumation and encasement of the corpses in wire mesh. Characteristics of Han-Chinese Liao tombs include north-south orientation and the funerary banquet. The rectangular room shape and absence of side rooms are also more common in Han Chinese tombs. All in all, the tomb resembles the hybrid Khitan-Chinese tombs that appear in the late Liao. Who, then, were the couple buried in the Kök Tash? We suppose that they were Buddhist Khitans, but while we cannot determine their ethnic and religious identity with any certainty at this stage, their political identity, namely their belonging to the elite of the Qara Khitai empire, is quite clear-cut.

Burial customs were among the main characteristics of the Khitan imperial culture that took shape in North China with the establishment of the Liao, together with the Khitan scripts and the creation of capital(s). In the pre-imperial era, the Khitans did not bury their dead but used ‘sky burial’, that is, they left bodies on a tree until the flesh had disappeared, later collecting the bones. Monumental burials had already begun by the time of the Liao founder Abaoji and became the most typical architectural form identified with the Khitans throughout the Liao period. It therefore makes sense that the Qara Khitai would continue to practise this major feature of the Liao imperial culture, just as they continued to use the Khitan script and language in Central Asia (alongside other languages and scripts, as was also the case in the Liao period). However, just as they adapted aspects of their government and administration to the new Central Asian environment, they made certain adaptations in their mortuary culture. The Kök Tash tomb therefore not only combines Khitan and Chinese features of the Liao tomb, but also local Central Asian elements. These included both building techniques, such as using baked bricks of local production, and prestigious local artefacts and raw materials, such as glazed blue ceramic tables and jade plates.

Such adaptations notwithstanding, the Kök Tash mausoleum is by far the most impressive archaeological evidence of the distinct Khitan character of the Qara Khitai empire. This fits well with the recent, albeit few in number, philological, historical, and archaeological publications which suggest that the Khitan character of the Qara Khitai was more pronounced than was previously thought.Footnote 87 It contributed, among other things, to the non-Islamisation of the Qara Khitai in Central Asia, despite their various adjustments to their new environment.

Moreover, this unique mausoleum may be the harbinger of a bigger discovery. We have already suggested that a few other graves unearthed in the Kochkor valley and at Talas might have also belonged to the Qara Khitai, and new research may further support this hypothesis. Moreover, a GPR survey conducted in the region in 2017 suggested that additional underground tombs were situated near the Kök-Tash mausoleum. We intend to further investigate the area and hopefully unearth additional, less disturbed, tombs belonging to this necropolis. Such further excavations would eventually allow us to better reconstruct the hitherto barely explored material culture of the Qara Khitai, as well as to gain more insights into this fascinating empire and its role in the history of medieval Central Asia.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Hiromi Kinoshita for providing them with her dissertation and Professors Francois Louis and Gideon Shelach-Lavi for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of interest

None.