Hallucinations and delusions, the classic symptoms of psychosis, have recently been documented to occur at a much higher prevalence in the general population than clinically diagnosed psychotic disorder. Reference Kelleher, Jenner and Cannon1 A meta-analysis of prevalence studies of psychotic symptoms in young people demonstrated a median prevalence of 17% in children aged 9–12 years and 7.5% in adolescents aged 13–18 years. Reference Kelleher, Connor, Clarke, Devlin, Harley and Cannon2 As the term suggests, psychotic symptoms have typically been considered to relate to psychotic disorder. Indeed, research has shown that members of the general population who report psychotic symptoms share a wide range of risk factors with people with schizophrenia (see Kelleher & Cannon for review), Reference Johns, Cannon, Singleton, Murray, Farrell and Brugha3–Reference Kelleher and Cannon9 and young people who report psychotic symptoms have been found to be at increased risk of psychotic disorder in adulthood. Reference Poulton, Caspi, Moffitt, Cannon, Murray and Harrington10,Reference Welham, Scott, Williams, Najman, Bor and O'Callaghan11 Individuals who report psychotic symptoms are also more likely to report non-psychotic psychopathological symptoms, especially symptoms of depression; Reference Wigman, Vollebergh, Raaijmakers, Iedema, van Dorsselaer and Ormel12–Reference De Loore, Gunther, Drukker, Feron, Sabbe and Deboutte16 Yung et al, for example, reported that individuals who had a diagnosed depressive disorder endorsed an increased number of psychotic symptoms on the Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences questionnaire compared with controls. Reference Yung, Buckby, Cosgrave, Killackey, Baker and Cotton17 Bartels-Velthuis et al found that young adolescents who disclosed psychotic symptoms were approximately 3–5 times more likely to score in the clinical psychopathology range on the parent-completed Child Behavior Checklist. Reference Bartels-Velthuis, van de Willige, Jenner, van Os and Wiersma18 Community-based studies to date, however, have relied mainly upon questionnaires to assess psychotic symptoms and have involved limited data on non-psychotic psychopathology. In addition, although research suggests that psychotic symptoms are more common in younger than in older children, Reference Kelleher, Connor, Clarke, Devlin, Harley and Cannon2 there is a lack of information on whether there are differences in the clinical significance of psychotic symptoms across different stages of adolescence. In an attempt to improve our understanding of the clinical significance of psychotic symptoms in the general population we examined data from four population studies, comprising two large population surveys and two in-depth clinical interview studies of psychotic symptoms. The aims of this work were to investigate whether psychotic symptoms predicted non-psychotic clinical diagnoses, and if so, which disorders; to investigate whether psychotic symptoms predicted more clinically severe disorder in terms of comorbid psychopathology (i.e. having more than one diagnosis); and to investigate whether the significance of psychotic symptoms varied as a function of age.

Method

Survey studies

Study 1: Early adolescence survey study

Sixteen schools in Dublin, Ireland, and surrounding areas took part in the Adolescent Brain Development study. Participants were aged 11–13 years and were in classes 5 and 6, the two most senior classes in the Irish primary school system. This was an ‘opt in’ study, with written parental consent required for adolescents to take part. In total 2190 consent forms were distributed, 1131 (52%) of which were returned with signed parental consent for the child to complete the survey in school. A total of 88.9% of participants were Irish-born, compared with 90.3% of children aged 0–14 years in the 2006 national census.

Study 2: Mid-adolescence survey study

Seventeen schools in Cork and Kerry, Ireland, took part in the mid-adolescence survey study (Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe). Reference Wasserman, Carli, Wasserman, Apter, Balazs and Bobes19 Participants were aged 13–16 years and were attending secondary level education. This was an ‘opt out’ study, with pupils allowed to take part if their parents did not return the consent form to specifically opt out. In total 1602 consent forms were distributed and approximately 70% of children (n = 1112) completed the survey in school. A total of 82.2% of participants were Irish-born.

Exposure and outcome measures

Both survey studies used the same exposure and outcome measures. Using the Adolescent Psychotic Symptom Screener (APSS), we have previously shown that a question on auditory hallucinations (‘Have you ever heard voices or sounds that no one else can hear?’) demonstrates very good positive and negative predictive validity not just for clinical interview-verifiable auditory hallucinations but for psychotic symptoms in general. Reference Kelleher, Harley, Murtagh and Cannon20 This question was used in both survey studies to assess for psychotic symptoms (exposure measure). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used as the measure of general psychopathology in both samples. Reference Goodman, Ford, Simmons, Gatward and Meltzer21 This is a well-validated brief screening instrument, which asks about 25 attributes divided into subscales. The emotional disorders section assesses for anxiety, depressive and obsessive–compulsive disorders, the conduct disorders section assesses for conduct and oppositional defiant disorders, and the hyperkinetic disorders section assesses for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A ‘total difficulties’ score is also generated by summing the psychopathology subscales, which predicts the presence of any psychiatric disorder. The SDQ has been validated both in terms of its ability to distinguish between clinic and community samples, Reference Goodman22 and as a screening device to detect children with a mental health disorder. Reference Goodman, Ford, Simmons, Gatward and Meltzer21 More recently, the SDQ has been shown not only to identify psychopathology at the time of assessment but also to predict disorder status 3 years later. Reference Goodman and Goodman23

Interview studies

Study 3: Early adolescence interview study

Participants in the early adolescence interview study were drawn from the Adolescent Brain Development study described above (study 1). Reference Kelleher, Murtagh, Molloy, Roddy, Clarke and Harley24 Of the 1131 adolescents who took part in the survey study, 656 (58%) indicated an interest in taking part in the interview study and a sample of 212 of these attended for interview. A total of 88.9% of participants were Irish-born (compared with 90.3% of children 0–14 years old nationally). Adolescents who attended for interview were no more likely to have an abnormal or borderline abnormal score on the SDQ (χ2 = 1.22, d.f. = 1, P = 0.27) and did not differ significantly in their scores on the APSS compared with the non-interviewed sample (interviewed group mean 1.8, s.e. = 0.12; non-interviewed group mean 1.9, s.e. = 0.19; t = 0.26, d.f. = 1130, P = 0.79).

Study 4: Mid-adolescence interview study

The mid-adolescence interview study (the Challenging Times study) was established to investigate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behaviour among Irish adolescents aged 13–15 years. Reference Lynch, Mills, Daly and Fitzpatrick25,Reference Harley, Kelleher, Clarke, Lynch, Arseneault and Connor26 The study took place in the geographical catchment area of a child and adolescent mental health team in north Dublin, with a population of 137 000. The participating schools were selected using a stratified random sampling technique according to the approximate socioeconomic class of the school in order to approximate to the geographical area population. A total of 743 pupils in eight mainstream schools were screened for psychiatric symptoms using the SDQ and the Children's Depression Inventory, which assesses cognitive, affective and behavioural signs of depression. Reference Kovacs27 Written informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian of participants. One hundred and forty pupils scored above threshold on these instruments, indicating a high risk of mental health problems, and all of these adolescents were invited to interview, of whom 117 (83.6%) agreed to attend for a full psychiatric interview. A comparison group of 173 adolescents, matched for gender and school, were also invited to attend, of whom 94 (54%) agreed. A frequency weight was applied to participants in this study to account for enrichment for psychopathology so that reported rates represent the general population rather than a psychopathology-enriched sample. Data were not collected on participant nationalities.

Exposure and outcome measures

The interview instrument used was the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children, Present and Lifetime versions (K-SADS-PL). Reference Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, Rao and Ryan28 This is a well-validated semi-structured research diagnostic interview for the assessment of all Axis I psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. Children and parents were interviewed separately, both answering the same questions about the child. In the early adolescence study interviews were conducted by two psychiatrists and four psychologists, and in the mid-adolescence study interviews were conducted by one psychiatrist and two psychologists, all trained in the use of the K-SADS-PL. Interrater reliability exceeded 90% for both studies, with κ values of 0.83 (study 3) and 0.85 (study 4). The psychosis section of the K-SADS-PL was used to assess the participants’ psychotic symptoms (hallucinations and delusions). All interviewers recorded extensive notes of potential psychotic phenomena in this section of the interview and a clinical consensus meeting was held following the interviews to classify these phenomena as psychotic symptoms or not, masked to diagnoses and all other information on the participants. The exposure measure was the presence or absence of psychotic symptoms and the outcome measure was a diagnosable lifetime affective, anxiety or behavioural disorder.

Ethical approval for studies 1 and 3 was received from the Beaumont Hospital medical ethics committee, for study 2 from the clinical research ethics committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals and for study 4 from the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital medical ethics committee.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 11.0 for Windows.

Survey studies

First, we used analysis of variance to test the association between auditory hallucinations and the SDQ ‘total difficulties’ score. Second, we divided the samples into quartiles based on their SDQ total difficulties scores and used logistic regression to test the odds of reporting psychotic symptoms in each quartile of (increasing) psychopathology. To test for a statistically significant increase (or decrease) in the prevalence of psychotic symptoms across the quartiles of SDQ-rated psychopathology, we used the Stata command nptrend, which is an extension of the Wilcoxon rank sum test and performs a non-parametric test for trend across ordered groups. We also used logistic regression to compare the prevalence of auditory hallucinations among the 5% who scored highest on SDQ total difficulties, which is often taken as a ‘severe’ psychopathology group, with the 5% who scored lowest on this measure. Finally, we stratified by the number of SDQ-rated disorder domains (emotional, conduct and hyperkinetic disorders) and used logistic regression to determine whether psychotic symptoms predicted comorbidity across these domains and, therein, more severe psychopathology.

Interview studies

Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were used to measure the relationship between psychopathology and psychotic symptoms. First, we recorded the prevalence of psychotic symptoms in diagnosable affective, behavioural and anxiety disorders together with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Second, we stratified by comorbidity/multiple pathology (i.e. having two or more Axis I diagnoses) in order to determine the prevalence of psychotic symptoms in increasingly severe (comorbid) disorders, and calculated odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association with psychotic symptoms. To test for a statistically significant increase (or decrease) in the prevalence of auditory hallucinations in line with the number of diagnosable psychiatric disorders, we used the Stata command nptrend.

Results

Survey studies

Association between psychotic symptoms and psychopathology

Psychotic symptoms were reported by 21% (n = 239) of the early adolescence sample (study 1) and 7% (n = 77) of the mid-adolescence sample (study 2). Increasing ‘total difficulties’ scores on the SDQ were associated with increasing odds of reporting psychotic symptoms (study 1: F = 94.72, P<0.001; study 2: F = 104.81, P<0.001). Adolescents who scored within the top quartile for SDQ-measured psychopathology in the early adolescence study were 6.5 times more likely to report psychotic symptoms compared with those in the lowest quartile (test for trend, Z = 8.60, P<0.001). Adolescents who scored within the top quartile for SDQ-measured psychopathology in the mid-adolescence study were nearly 16 times more likely to report psychotic symptoms compared with those in the lowest quartile (test for trend, Z = 7.32, P<0.001) (Table 1). In fact, in study 1, among adolescents with the top 5% SDQ total difficulties scores 48.1% reported psychotic symptoms, in contrast to just 2.9% of adolescents with the lowest 5% total difficulties score (OR = 31.10, 95% CI 6.91–140.02, P<0.001). In study 2, among adolescents with the top 5% SDQ total difficulties scores 35% reported psychotic symptoms, in contrast to just 1.4% of adolescents with the lowest 5% scores on this measure (OR = 38.78, 95% CI 4.95–304.02, P<0.001). Psychotic symptoms were not confined to any one disorder; rather, they were reported at an increased prevalence across each of the SDQ-rated emotional, conduct and hyperkinetic disorders (Table 2).

TABLE 1 Odds of experiencing psychotic symptoms according to Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire psychopathology scores in quartiles in the early adolescence survey study (study 1) and the mid-adolescence survey study (study 2)

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children with psychotic symptoms % |

OR (95% CI) | Children with psychotic symptoms % |

OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Quartile | n | Unadjusted | AdjustedFootnote a | n | Unadjusted | AdjustedFootnote a | ||

| 1 | 313 | 7.7 | 1 | 1 | 278 | 1.4 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 322 | 18.0 | 2.31 (1.42–3.76) | 1.91 (1.10–3.32) | 234 | 3.4 | 2.40 (0.71–8.07) | 2.35 (0.69–7.90) |

| 3 | 221 | 22.2 | 3.00 (1.81–4.97) | 2.59 (1.45–4.60) | 250 | 5.7 | 4.07 (1.32–12.55) | 4.08 (1.32–12.59) |

| 4 | 276 | 38.2 | 6.50 (4.09–10.33) | 5.50 (3.25–9.30) | 235 | 19.0 | 15.80 (5.58–44.71) | 15.82 (5.57–44.94) |

| Test for trend across quartiles | Z = 8.60, P<0.001 | Z = 7.32, P<0.001 | ||||||

a. Adjusted for gender.

TABLE 2 Odds of experiencing psychotic symptoms among adolescents with emotional, hyperkinetic and conduct disorders in the early adolescence survey study (study 1) and the mid-adolescence survey study (study 2)

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children with psychotic symptoms % |

OR (95% CI) | Children with psychotic symptoms % |

OR (95% CI) | |||

| DisorderFootnote a | Unadjusted | AdjustedFootnote b | Unadjusted | AdjustedFootnote b | ||

| Emotional disorders | 44 | 3.44 (2.33–5.10) | 2.98 (1.89–4.69) | 22 | 4.79 (2.78–8.28) | 5.19 (2.97–9.06) |

| Hyperkinetic disorders | 35 | 2.34 (1.62–3.37) | 2.74 (1.80–4.18) | 15 | 3.06 (1.86–5.04) | 3.00 (1.81–4.98) |

| Conduct disorders | 36 | 2.38 (1.63–3.48) | 2.91 (1.85–4.58) | 20 | 4.60 (2.75–7.71) | 4.68 (2.77–7.93) |

a. Rated according to the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

b. Adjusted for gender.

Comparison of studies 1 and 2

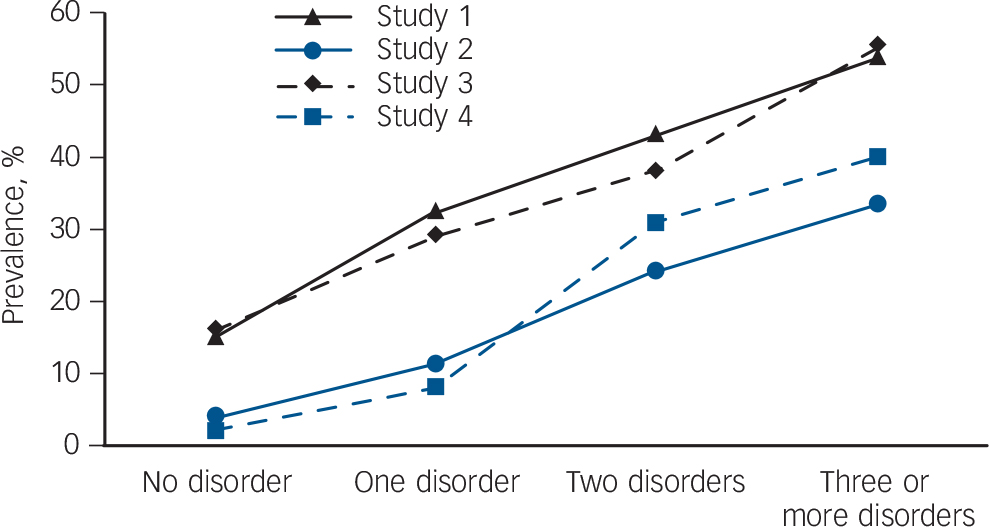

The risk of psychopathology in adolescents with psychotic symptoms varied as a function of age, with participants less likely to endorse the auditory hallucinations question as age increased. However, psychotic symptoms became more closely associated with psychopathology as age increased, in that 49% of the early adolescent sample who endorsed the auditory hallucinations question scored in the clinical psychopathology range on at least one SDQ-rated disorder domain compared with 65% of the mid-adolescence sample (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1 Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in adolescents with zero, one, two, or three or more lifetime diagnoses in the early adolescence survey sample (study 1), early adolescence interview sample (study 3), mid-adolescence survey sample (study 2) and mid-adolescence interview sample (study 4).

Multiple psychopathology

In order to investigate whether psychotic symptoms were more prevalent in adolescents with more severe psychopathology, we calculated the prevalence of psychotic symptoms among adolescents who scored positively for psychopathology on one, two or all three of the disorder domains compared with adolescents with no disorder. In the early adolescence sample (study 1), 15% of participants with no SDQ-rated disorder reported psychotic symptoms, compared with 33% of adolescents who were abnormal on one SDQ disorder domain (OR = 2.71, 95% CI 1.85–3.98, P<0.001), 43% of adolescents who were abnormal on two SDQ disorder domains (OR = 4.85, 95% CI 2.69–8.74, P<0.001) and 54% of adolescents who were abnormal on all three SDQ disorder domains (OR = 8.59, 95% CI 2.00–36.92, P<0.001) (test for trend: Z = 7.83, P<0.001). Among the mid-adolescence sample (study 2) the prevalence of psychotic symptoms among those who were not abnormal on any of the three SDQ disorder domains was less than 4%, but for psychopathology in one domain the prevalence of hallucinations was 11% (OR = 3.33, 95% CI 1.91–5.80, P<0.001), for psychopathology in two domains the prevalence of hallucinations was 24% (OR = 8.00, 95% CI 4.02–15.92, P<0.001) and for psychopathology in all three domains the prevalence of hallucinations was 33% (OR = 12.96, 95% CI 4.53–37.08, P<0.001) (test for trend, Z =7.33, P<0.001).

Interview studies

Thirty-one per cent of the early adolescence interview study sample (study 3) had a lifetime diagnosable affective, anxiety or behavioural disorder. The lifetime disorders included depressive disorders, including major depressive disorder and adjustment disorder with depressed mood (15%); behavioural disorders, including ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder (9%); and anxiety disorders, including generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder (14%). Thirty-four per cent of the mid-adolescent interview study sample (study 4) had a lifetime diagnosable affective, anxiety or behavioural disorder. The lifetime disorders included depressive disorders, including major depressive disorder and adjustment disorder with depressed mood (18%); behavioural disorders, including ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder (9%); and anxiety disorders, including generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder and panic disorder (11%).

TABLE 3 Odds of experiencing psychotic symptoms among adolescents with lifetime DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses diagnosed by clinical interview in the early adolescence interview study (study 3) and the mid-adolescence interview study (study 4)

| Study 3 | Study 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children with psychotic symptoms % |

OR (95% CI) | Children with psychotic symptoms % |

OR (95% CI) | |||

| Diagnosis | Unadjusted | AdjustedFootnote a | Unadjusted | AdjustedFootnote a | ||

| Any lifetime Axis I disorder | 40 | 3.73 (1.97–7.07) | 3.57 (1.87–6.84) | 19 | 11.15 (2.99–41.65) | 11.94 (3.14–45.41) |

| Affective disorder | 51 | 4.93 (2.31–10.51) | 5.08 (2.33–11.07) | 24 | 10.67 (3.33–34.19) | 12.33 (3.69–41.19) |

| Behavioural disorder | 50 | 3.95 (1.55–10.10) | 3.23 (1.24–8.43) | 22 | 5.14 (1.43–18.51) | 4.55 (1.23–16.75) |

| Anxiety disorder | 23 | 0.99 (0.48–2.06) | 1.01 (0.48–2.12) | 9 | 1.45 (0.30–6.95) | 1.67 (0.34–8.22) |

a. Adjusted for gender

Psychotic symptoms and association with psychopathology

In the study 3 (early adolescence) sample 22.6% (n = 53) reported psychotic symptoms, primarily auditory hallucinations (>90%). The prevalence of psychotic symptoms was higher among boys (χ2 = 7.03, P<0.01). Although participants were asked about lifetime psychotic symptoms, in almost all cases adolescents who reported psychotic symptoms had experienced these symptoms within the past year – only 3 participants from the entire sample who reported lifetime psychotic symptoms did not report experiencing these symptoms within the past year, indicating that a report of lifetime symptoms in reality almost always indicates recent symptoms. Of all adolescents who reported psychotic symptoms, 57% had a lifetime diagnosable Axis I disorder (OR = 3.73, 95% CI 1.97–7.07, P<0.001) and 30.2% had a current diagnosable Axis I disorder (OR = 3.46, 95% CI 1.64–7.31, P<0.01). Adolescents with a lifetime diagnosable affective disorder were 5 times more likely to report psychotic symptoms compared with the rest of the sample, whereas adolescents with a lifetime diagnosable behavioural disorder were 3 times more likely to report psychotic symptoms (Table 3).

In the study 4 (mid-adolescence) sample 7% of participants reported psychotic symptoms, primarily auditory hallucinations (>90%). There was a trend for psychotic symptoms to be more prevalent among boys (χ2 = 3.62, P = 0.057). Of all adolescents who reported psychotic symptoms, 79% had a lifetime diagnosable Axis I disorder (OR = 11.94, 95% CI 3.14–45.41, P<0.01) and 43% had a current diagnosable Axis I disorder (OR = 4.27, 95% CI 1.38–13.21, P = 0.01). Adolescents with a lifetime diagnosable affective disorder were more than 10 times more likely to report psychotic symptoms compared with the rest of the sample, whereas adolescents with a lifetime diagnosable behavioural disorder were 5 times more likely to report psychotic symptoms (Table 3).

TABLE 4 Odds of experiencing psychotic symptoms in adolescents with one, two or three or more comorbid DSM-IV Axis I disorders diagnosed by clinical interview in the early adolescence interview study (study 3) and the mid-adolescence interview study (study 4)

| Study 3 | Study 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children with psychotic symptoms % |

OR (95% CI) | Children with psychotic symptoms % |

OR (95% CI) | |||

| Diagnosis | Unadjusted | AdjustedFootnote a | Unadjusted | AdjustedFootnote a | ||

| One disorder only | 29 | 2.25 (1.06–4.75) | 2.27 (1.06–4.87) | 8 | 3.86 (0.83–17.88) | 4.12 (0.88–19.38) |

| Two disorders only | 38 | 3.23 (1.27–8.27) | 3.18 (1.22–8.29) | 31 | 20.15 (4.24–95.59) | 18.33 (3.77–89.15) |

| Three or more disorders | 55 | 6.47 (1.82–22.98) | 6.31 (1.73–23.05) | 40 | 29.56 (3.53–247.17) | 36.18 (3.94–332.06) |

| Test for trend | Z = 3.67, P<0.001 | Z = 4.29, P<0.001 | ||||

a. Adjusted for gender.

Multiple psychopathology

More than one diagnosable psychopathological disorder was present in 15% (n = 35) of the early adolescence sample (study 3) and in 10% (n = 21) of the mid-adolescence sample (study 4). We observed a dose–response relationship between the number of diagnoses the participants had and their risk of reporting psychotic symptoms (Table 4, Fig. 1).

Discussion

Using two large population-based survey studies and two in-depth clinical interview studies, we have shown a number of important findings. First, psychotic symptoms are prevalent in a wide range of non-psychotic psychopathologies. Second, although psychotic symptoms are not pathognomonic of illness, the majority of young people in the community who report psychotic symptoms do have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. Third, psychotic symptoms index a particularly high risk of multiple pathology (having more than one DSM diagnosis). Fourth, psychotic symptoms are reported more commonly in early than in middle adolescence. Fifth, psychotic symptoms become increasingly predictive of diagnosable psychopathology with increasing age.

Although some research has shown that the majority of psychotic symptoms in childhood are transient, with symptoms that persist over time thought to be of more clinical significance, Reference Van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and Krabbendam29 in the current study the majority of adolescents who reported psychotic symptoms had at least one diagnosable psychiatric disorder, regardless of the issue of psychotic symptom persistence. Increased risk of psychopathology was not related to a particular diagnosis or even one group of disorders; rather, a variety of Axis I disorders were associated with psychotic symptoms. Interestingly, however, psychotic symptoms demonstrated a particularly strong relationship with more severe psychopathology, with prevalence of psychotic symptoms increasing in a dose–response fashion with the number of diagnosable disorders. In study 4, for example, 40% of adolescents with three or more comorbid disorders reported psychotic symptoms, compared with just 8% of adolescents with only one disorder (see Table 4).

Psychotic symptoms were more common in early adolescence in both the surveyed and interviewed samples (21% and 23%) compared with middle adolescence (7% in both samples). This is in line with meta-analytic findings of a decline in prevalence of psychotic symptoms from childhood into adolescence. Reference Kelleher, Connor, Clarke, Devlin, Harley and Cannon2 However, associations between psychotic symptoms and diagnosable disorder were stronger in the older, compared with the younger, samples. Whereas 57% of the early adolescence sample who reported psychotic symptoms had a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, nearly 80% of the mid-adolescence sample who reported psychotic symptoms had at least one diagnosable disorder. In a study of children aged 7–8 years Bartels-Velthuis et al found that auditory hallucinations were associated with only a minor increase in risk of parent-reported behavioural and emotional symptoms, Reference Bartels-Velthuis, Jenner, van de Willige, van Os and Wiersma30 but that at age 12–13 years psychotic symptoms predicted an approximately 3- to 5-fold increased risk of scoring in the clinical range of the Child Behavior Checklist. Reference Bartels-Velthuis, van de Willige, Jenner, van Os and Wiersma18 Hallucinatory and delusional experiences, then, may fall within the normal spectrum of experience in childhood but might be expected to discontinue in the course of development. Psychotic symptoms in adolescence, the current findings suggest, become increasingly associated with psychopathology – in particular with severe, multiple diagnoses (see Fig. 1).

There are a number of possible explanations as to how psychotic symptoms act as a marker for a wide range of psychopathologies. One possibility is that the same risk factors may predispose to both psychotic symptoms and psychiatric illness. In fact, Breetvelt et al have recently demonstrated that many risk factors that have typically been considered risk factors for psychosis are risk factors for a wider range of (non-psychotic) psychopathologies. Reference Breetvelt, Boks, Numans, Selten, Sommer and Grobbee31 It is also possible that psychological distress caused by psychotic symptoms contributes to, for example, depressive thoughts or behavioural symptoms. It may also be the case, however, that psychotic symptoms do not contribute to psychopathology per se but, rather, emerge in vulnerable individuals who experience non-psychotic psychopathology and therein act as a marker, rather than an aetiological factor, for non-psychotic psychopathology. From a biological perspective, Alemany et al have recently published the first study documenting a molecular genetic association, showing an interaction between the BDNF val66met polymorphism and childhood trauma in increasing risk of psychotic symptoms. Reference Alemany, Arias, Aguilera, Villa, Moya and Ibanez32 The limited structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) research on psychotic symptoms to date suggests that adolescents with psychotic symptoms exhibit a profile of subtle neurodevelopmental differences that shares features with a number of psychiatric disorders. Reference Jacobson, Kelleher, Harley, Murtagh, Clarke and Blanchard33 A recent meta-analysis of brain volume abnormalities in major depressive disorder, for example, showed that the greatest changes occur in two regions important in emotion processing and stress regulation – the cingulum and orbitofrontal cortex, Reference Koolschijn, van Haren, Lensvelt-Mulders, Hulshoff Pol and Kahn34 both of which we have recently shown to be abnormal in adolescents with psychotic symptoms. Reference Jacobson, Kelleher, Harley, Murtagh, Clarke and Blanchard33 Using functional MRI and digital tractography, we have demonstrated reduced activity within the right frontal and bilateral temporal cortices during response inhibition tasks and overall reduced integrity of fronto-temporal pathways in adolescents with psychotic symptoms, Reference Jacobson, Kelleher, Harley, Murtagh, Clarke and Blanchard33 supporting a profile of a relative disinhibition/pro-impulsivity phenotype. These neurobiological findings mirror our clinical findings of increased affective and behavioural disorders. From a psychological perspective, psychotic symptoms in young people have been linked to poorer theory of mind and an externalised locus of control, Reference Thompson, Sullivan, Lewis, Zammit, Heron and Horwood35,Reference Bartels-Velthuis, Blijd-Hoogewys and van Os36 both of which have been shown to predict poorer mental health outcomes. Reference Liu, Kurita, Uchiyama, Okawa, Liu and Ma37,Reference Brune and Brune-Cohrs38

The relevance of our findings extends beyond adolescent mental health; the finding that psychotic symptoms are highly prevalent in a range of (non-psychotic) disorders raises questions about traditional diagnostic boundaries. Although psychosis has conventionally been considered as separate from ‘neurotic’ disorders, a number of researchers have questioned the independence of the psychoses and non-psychotic psychopathology. Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington39–Reference Freeman, Garety, Kuipers, Fowler and Bebbington41 The high prevalence of psychotic symptoms in a wide variety of non-psychotic disorders as demonstrated in the present research suggests that divisions between the neuroses and psychoses are not clear-cut.

Strengths of this research most notably include the use of four studies, each of which shows the same pattern of results. Although the larger survey studies allowed us to test for relationships between psychotic symptoms and psychopathology in terms of a symptomatic continuum, the downside of this approach is that clinical implications, in the absence of actual diagnoses, can be hard to draw. However, the inclusion of two clinical interview studies allows us to draw clear clinical implications by exploring the relationship between psychotic symptoms and actual psychiatric diagnoses. The use of multiple studies also allowed us to examine the relationship between psychotic symptoms and psychopathology from early through middle adolescence. In addition, the use of community samples is particularly valuable because findings are generalisable to the population. A limitation is that the issue of temporality cannot be resolved in the current study: which came first, psychotic symptoms or psychopathology, or indeed did both arise together? However, this does not detract from the clinical usefulness of understanding the contemporaneous relationship between psychotic symptoms and non-psychotic psychopathology. Subgroup analysis within studies means that group sizes are small, and confidence intervals as a result are wide in some cases. However, the same pattern of results was found across all four studies, showing that the findings are robust.

Implications of the study

Hallucinations and delusions, although classically known as symptoms of psychosis, are common in a wide range of non-psychotic psychiatric disorders in young people. These symptoms become increasingly associated with diagnosable psychopathology with age. Psychotic symptoms demonstrated a particularly strong relationship with more severe psychopathology, indexing high risk for multiple disorders (i.e. the presence of two or more co-occurring diagnoses). These findings have a number of important clinical implications. First, psychotic symptoms, which are to a large extent seen as an ‘adult psychiatry’ issue, are in fact very prevalent in childhood and adolescence and should be carefully assessed in child and adolescent psychiatric clinics. Second, when psychotic symptoms are present they index risk for severe psychopathology in terms of the patient having more than one diagnosable disorder and, following from this, should prompt the clinician to consider the potential importance of multiple therapeutic targets and/or approaches. For researchers, these findings highlight psychotic symptoms as a complex novel aspect in the study of the aetiology of severe mental illness, of which schizophrenia is only one. Research has only recently begun on neurogenetics, imaging, electrophysiology and cognition among individuals with psychotic symptoms. Reference Alemany, Arias, Aguilera, Villa, Moya and Ibanez32,Reference Jacobson, Kelleher, Harley, Murtagh, Clarke and Blanchard33,Reference Cullen, Dickson, West, Morris, Mould and Hodgins42–Reference Kelleher, Clarke, Rawdon, Murphy and Cannon45 Much more work will be necessary to explore the role of psychotic symptoms – symptoms which, to date, have been largely considered features of psychotic illness – in the aetiology of a broad range of non-psychotic psychiatric disorders.

Funding

The Adolescent Brain Development Study was supported by an Essel NARSAD/Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Independent Investigator award and a Clinician Scientist Award (CSA/2004/1) from the Health Research Board (Ireland) to M.C. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement HEALTH-F2-2010-241909 (Project EU-GEI); EU-GEI is the acronym of the project European Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying Gene–Environment Interactions. The Challenging Times study was supported by Friends of the Children’s University Hospital (Dublin), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the Health Service Executive (HSE) Northern Area and the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin. The Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe (SEYLE) project is supported through Coordination Theme 1 (Health) of the European Union Seventh Framework Program (FP7), grant agreement HEALTH-F2-2009-223091. The SEYLE project in Ireland was also supported by funding from the HSE National Office for Suicide Prevention. The project leader and coordinator of SEYLE is Professor Danuta Wasserman, head of the National Swedish Prevention of Mental Ill-Health and Suicide (NASP), Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. Other members of the Executive Committee are Professor Marco Sarchiapone, Department of Health Sciences, University of Molise, Campobasso, Italy; Vladimir Carli, NASP, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden; Professor Christina Hoven and Camilla Wasserman, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University, New York, USA.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Clinical Research Centre at Beaumont Hospital for use of research rooms. The Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe (SEYLE) Consortium comprises centres in 12 European countries. Site leaders for each respective centre and country are Danuta Wasserman (Karolinska Institute, Sweden), Christian Haring (University for Medical Information Technology, Austria), Airi Varnik (Estonian-Swedish Mental Health and Suicidology Institute, Estonia), Jean-Pierre Kahn (University of Nancy, France), Romuald Brunner (University of Heidelberg, Germany), Judit Balazs (Vadaskert Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Hospital, Hungary), Paul Corcoran (National Suicide Research Foundation, Ireland), Alan Apter (Schneider Children's Medical Centre of Israel, Tel-Aviv University, Israel), Marco Sarchiapone (University of Molise, Italy), Doina Cosman (Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania), Dragan Marusic (University of Primorska, Slovenia) and Julio Bobes (University of Oviedo, Spain).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.