A suboptimal diet is one of the most important contributing risk factors for death globally(Reference Forouzanfar, Alexander and Anderson1). While accurate information about nutrition would likely help improve public health, nutritional misinformation may cause confusion and doubt and hence lead to unhealthy dietary habits(2–Reference Clark, Nagler and Niederdeppe5). Although people are interested in obtaining information on diet and health, distinguishing accurate information from misinformation remains challenging(2). Despite the need to provide the general population with accurate and evidence-based information on nutrition(Reference Tufford, Calder and Van’t Veer6), the question of whether this is what they receive remains largely unknown.

People obtain information on diet and/or health from various sources, including primary care providers, family, websites, television and books(Reference Chen, Hay and Waters7,8) . In the USA, approximately 30 % of people obtain health information from books(Reference Chen, Hay and Waters7). A similar proportion is seen in Japan: the 2019 Japanese National Health and Nutrition Survey reported that 23 % of the population refers to books and magazines for dietary information(8). Importantly, however, although a certain number of people refer to books for information on diet and health, the scientific accuracy of the information in such books is not necessarily guaranteed.

The quality of health information has been evaluated in relation to its currency (date of publication and relevant updates), conflict of interest, authorship, readability, explanation of potential harms and costs, presence and type of references and appropriate description of research (e.g. study participants, methods and qualitative results)(Reference Zhang, Sun and Xie9–Reference Schwitzer16). Among these aspects, the presence of references was evaluated in many tools used to assess the quality of health information(Reference Zhang, Sun and Xie9–Reference Robillard, Jun and Lai14). The citation of references is not a sufficient requirement to ensure the reliability of information but is a minimum requirement. Additionally, several of these tools also evaluate reference type, such as journal articles(Reference Robinson, Coutinho and Bryden12,Reference Provost, Koompalum and Dong13) and study design(Reference Robillard, Jun and Lai14). Although reference type does not necessarily guarantee the accuracy of information, reliable information nevertheless requires an appropriate type of reference.

In the health-related field, the citation and quality of information have been investigated in other media(Reference Oxman, Larun and Perez Gaxiola15,Reference Denniss, Lindberg and McNaughton17) , such as newspaper articles(Reference Zimmermann and Andersson18,Reference Akamatsu, Naito and Nakayama19) , advertisements(Reference Othman, Vitry and Roughead20,Reference Mandoh and Curtain21) and websites(Reference Hunter, Delbaere and O’Connell22–Reference Goto, Sekine and Sekiguchi28). However, this topic has rarely been investigated in books(Reference Marton, Wang and Barabási29). In a study of 100 best-selling nutritional books in the USA, reference sources were investigated in only seven of the 100 books because the examination of references was not the focus of the study(Reference Marton, Wang and Barabási29). It remains unclear what proportion of high-selling nutritional books provide references and which reference type they use.

The primary aim of this study was to describe the references cited in popular books about diet and health in the USA and Japan. The secondary aim was to examine the characteristics of books and authors associated with the citation of references and systematic reviews of human research. We compare the USA as a representative English-speaking country and Japan as a representative non-English-speaking country with high book sales(30).

Materials and methods

Book selection strategy

We selected 100 popular books about diet and health in each of the USA and Japan. Selection was based on the best-seller rankings of two popular online bookstores in each country. In the USA, Amazon and Barnes & Noble were used because they have a large market share in the USA(Reference Chevalier and Goolsbee31). In Japan, in addition to Amazon Japan, which is a popular online bookstore(32), honto was used because it has large sales(33) and an appropriate category related to diet and health.

In January and February 2022, we selected books on the basis of the best-seller rankings in a related category of each online bookstore at 10:00 AM on 19th December 2021 (JST). The definition of ‘best-seller rankings’ varied among the bookstores. Amazon has explained that ‘the Amazon Best Sellers calculation is based on Amazon sales and is updated hourly to reflect recent and historical sales of every item sold on Amazon’(34). The web sites of Barnes & Nobles and honto did not provide any explanation for their rankings; rather, online chat with Barnes & Noble’s customer service revealed that ‘best-seller rankings’ meant bestsellers online within an undefined period, while email with honto customer service revealed that ‘best-seller rankings’ meant bestsellers online within the latest 30 d.

We excluded the following books: (1) books unrelated to health; (2) books unrelated to diet or nutrition; (3) magazines; (4) food composition tables; (5) diaries; (6) autobiographies; (7) textbooks for students or experts and (8) books written in non-English (for the USA) or non-Japanese (for Japan). Exclusion was based on the title and summary of the book as described in the online bookstores. For example, books were excluded if the title and summary did not include words related to both health (e.g. health, death, diseases and specific name of diseases) and nutrition or diet (e.g. dietary, eating, food, nutrients and specific name of foods and nutrients). Two researchers independently excluded books and resolved any disagreements through discussion. Although the bookstores have several categories related to diet and health, we used the category in each bookstore that had the fewest books meeting the exclusion criteria: the ‘Diets & Weight Loss’ category for Amazon, the ‘Diet & Nutrition’ category for Barnes & Noble, the ‘Diet & Nutrition’ category for Amazon Japan and the ‘Nutrition & Diet’ category for honto. Detailed information on these categories (i.e. stratification of categories and URL) is shown in online Supplemental Table 1.

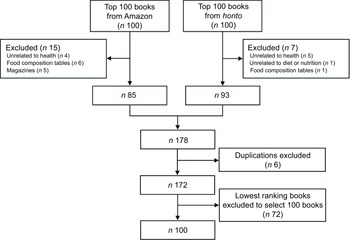

As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, the 100 highest-selling books in the respective categories were identified, resulting in 200 books in each country, including duplicates. We then excluded books that met the above exclusion criteria, resulting in 183 US books and 178 Japanese books. After the exclusion of duplicate books, 142 US books and 172 Japanese books remained. From these books, the selection was conducted using the ‘best-seller rankings’ of the book sites mentioned above. Selecting alternately in the two sites, we selected up to 100 higher-ranking books in each country (see online Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). As a result, 100 US books selected were included in the top sixty-nine best-selling books on Amazon and the top sixty-nine on Barnes & Noble, and 100 Japanese books were included in the top sixty on Amazon and the top sixty on honto. The number of books was determined considering the feasibility and number of books examined in a previous study(Reference Shin and Valente35), without a specific sample-size calculation.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of the selection of 100 US popular books about diet and health

Fig. 2 Flow chart of the selection of 100 Japan popular books about diet and health

Book characteristics

For each book, we extracted the title, author name, publication year, number of pages and international standard book number code from the summary pages provided by the online bookstores. Publication year was categorised as before 2019 or 2019–2021 so that the number of books categorised into each category was approximately equal. The number of pages was categorised using the median value of each country because Japanese and English differ in the amount of information per character, and English generally requires more characters. Additionally, the title and summary were used to determine target readers, main themes and book types (translated books or not). Categories of target readers and main themes were created by researchers after the titles and abstracts of the books were checked. We set three categories to classify target readers: general population, patients (i.e. diabetes) and others. The main themes were classified into six categories: (1) culinary recipes; (2) health effects of a specific diet, including foods, nutrients, dietary patterns, or dietary habits; (3) general health; (4) losing weight; (5) prevention or management of specific diseases and (6) others. One researcher categorised a book, which was confirmed twice by two other researchers without independence, with disagreement resolved by consensus.

Author characteristics

Authors’ information was derived from information in the books, summary pages of the books on the online bookstores or both, without further examination using other sources. The presence of author information was categorised into three groups: information provided, no author or editor and no information about author other than the author’s name. When information about authors was provided, we obtained the affiliations and licences of the first author (or first editor if there were only editors). The books were then categorised according to the first author affiliation (university (yes or no), company (yes or no) and hospital or clinic (yes or no)) and according to the first author degree and licences (doctoral degree (yes or no), medical doctor (yes or no), registered dietitian (yes or no) and other licences related to nutrition (yes or no)). These characteristics were extracted by one researcher and confirmed by another researcher without independence, with any disagreements resolved by discussion.

References in books

We examined all references mentioned on any page of a book, including its text, footnotes and bibliographies. References were distinguished using citation formats in a citation guide(Reference Lipson36). In this study, in addition to references in the bibliographies, references with in-text citation without mention in a bibliography were also considered references. For example, such explanations as ‘a US study showed that XX (Sasaki S, 2000)’ and ‘the Nurses’ Health Study showed that XX (Public Health Nutr, 2020)’ were also considered as references even if there was no bibliography. On the other hand, studies mentioned in the text but not provided as a reference (e.g. ‘a US study showed that XX’ and ‘the Nurses’ Health Study showed that XX’) were not considered references. Additionally, when the names of the journals were mentioned only for the presentation of authority without other information, such as publication years and authors’ names (e.g. ‘According to research in Lancet, a prestigious medical journal’ and ‘According to research in a national academic journal’), they were not considered references. When books mentioned ‘Dietary Reference Intakes’, ‘Dietary Guidelines for Americans’ and ‘the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top’, these were included as references because the source of information was identifiable. Bibliography items provided as online materials were also included as references. Recommended sources for further information were not considered references.

The books were then categorised according to whether they cited each of the following sources at least once: any research paper (yes or no); research papers on human subjects (yes or no); systematic reviews of human studies (with or without meta-analyses) published in academic journals (yes or no); Dietary Reference Intakes (yes or no) and national dietary guidelines (i.e. the Dietary Guidelines for Americans for US(37) and the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top for Japan(Reference Yoshiike, Hayashi and Takemi38), yes or no). These categories were developed considering tools previously used to assess information reliability(Reference Robinson, Coutinho and Bryden12–Reference Robillard, Jun and Lai14). The presence of any research papers, research papers on human subjects and systematic reviews of human studies were determined using the title, abstract and full text of the reference. Additionally, each reference was categorised as provided in an identifiable format or not. For example, ‘Public Health Nutr, 2009;109(10): XX–YY’ was categorised as an identifiable format, whereas ‘Public Health Nutr, 2020’, and ‘Sasaki S, 2000’ were categorised as unidentifiable formats. We then categorised each book by reference format into: (1) identifiable format for all references; (2) identifiable format for some but not all references and (3) unidentifiable format for all references. The citations of specific sources and reference formats were examined by one researcher and confirmed by another researcher without independence, with any disagreements resolved by discussion.

The number of references was counted for each book. When references were provided in a bibliography, the number of references in the bibliography was counted. When references were shown within text or on pages without a bibliography, we counted them manually. Duplicate references in text or bibliographies were not identified. The number of references was categorised as 1–10, 11–100, 101–1000 and more than 1000. Additionally, the location of the references was examined. Books were categorised into those that cited all references in figures or tables only and those that cited at least one reference in the text. The number of references and location of references were examined by one researcher and confirmed twice by two other researchers without independence, with any disagreements resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

Data were described using the number and percentages of books. All analyses were carried out using the chi-square test. When the expected frequency was less than five in more than 20 % of category values, Fisher’s exact test was used instead of the chi-square test. The characteristics of books and references were compared between the USA and Japan. We also examined the association of the characteristics of books (publication year, pages, target readers and main theme) and the degree and licences of the first author (doctoral degree, medical doctor and registered dietitian) with the citations of references and systematic reviews of human studies. Additionally, we compared the books that cited references and systematic reviews in the USA with those in Japan in each subgroup (i.e. the characteristics of books and degrees and licences of the first author). As a post hoc analysis, we examined associations of doctoral degrees with the citations of systematic reviews among books written by medical doctors, non-medical doctors and registered dietitians, respectively. Cohen’s κ and its 95 % CI were calculated to assess inter-rater agreement in the selection or exclusion of books. We considered a κ coefficient between 0·40 and 0·60 as a moderate agreement, 0·61 and 0·80 as a substantial agreement and 0·81 and 1·00 as an almost agreement(Reference Landis and Koch39). We did not calculate Cohen’s κ for other variables, which were confirmed by multiple researchers without independence; for each variable, we presented the number of books with disagreement and discussion needed during the process confirmed by the second researcher. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.), with two-tailed P values < 0·05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of popular books about diet and health in the USA and Japan. More US books were published before 2019 than Japanese books (P = 0·006). In both countries, around eighty books targeted the general population, while fourteen US books and eleven Japanese books targeted patients. The main theme of books differed in USA and Japan (P = 0·03). Culinary recipes accounted for 37 % in the USA and 21 % in Japan, whereas health effects of a specific diet accounted for 21 % in the USA and 36 % in Japan. The median number of pages was 312 (25–75th percentile: 240–384) for US books and 168 (25–75th percentile: 122–221) for Japanese books.

Table 1 General characteristics of popular books about diet and health in the USA and Japan (n 100, each country)

* P values for the chi-square test. When the expected frequency was less than five in more than 20 % of category values, Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used.

† These categories were decided using the title and abstract of online bookstores.

‡ Information about authors was derived from information in the book, summary pages of the books on the online bookstores or both without further examination using other sources (e.g. author’s web page). Books with no authors or editors or no information about authors were classified as having no affiliation and no licences of the first author.

§ Books could be categorised into more than one category.

One US book and thirteen Japanese books had no authors or editors. Two US books and one Japanese book had authors but did not present the author’s information other than their name, whereas ninety-seven US and eighty-six Japanese books presented the authors’ information. Compared to the USA, more first authors were affiliated with hospitals or clinics (P < 0·001) and had a doctoral degree (P = 0·004) in Japan. We observed no significant differences in other affiliations or licences of the first author between the USA and Japan. Among authors with a medical doctor licence, no author (0 %) presented their doctoral degrees in the USA, whereas twenty-one authors (54 %) presented a doctoral degree in Japan. Among authors with a registered dietitian licence, one author (11 %) had a doctoral degree in the USA, whereas no author (0 %) had a doctoral degree in Japan (see online Supplemental Table 4).

Although approximately 65 % of books cited references in both countries (n 65 in the USA, n 66 in Japan), the type of sources cited as references differed between the two countries (Table 2). In the USA, more books cited any research papers and research papers on humans than in Japan. All US books citing any research papers cited at least one research paper on humans. In other words, no US book cited only non-human research papers. Among thirty-one Japanese books citing research papers, two did not cite research papers on humans: one cited a research paper on cells and mice, and another cited a narrative review of biological mechanisms mainly comprised non-human research. Additionally, we observed a marked difference in the number of books that cited systematic reviews of human studies in the USA (n 49) and in Japan (n 9). The Japanese books cited Dietary Reference Intakes (n 24) more than the US books (n 12). Only four Japanese books cited national dietary guidelines (i.e. the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top), whereas nineteen US books cited Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Table 2 Characteristics of references in books about diet and health in the USA and Japan (n 100, each country)

* P values for the chi-square test.

† Systematic reviews of human studies (with or without meta-analyses) published in academic journals.

‡ National dietary guidelines were the Dietary Guidelines for Americans for the USA and the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top for Japan.

Among books with references (n 65 in the USA, n 66 in Japan), all US books had references in the text (not only on figures and tables), while this was true for 76 % of the Japanese books (Table 3). Additionally, 97 % of the US books presented all references in an identifiable format, whereas 64 % of the Japanese books did so. Moreover, the US books cited a larger number of references than the Japanese books. Thirty-seven US books cited more than 100 references, while only five Japanese books cited more than 100 references.

Table 3 Characteristics of references in books that cited references (n 65 in the USA, n 66 in Japan)

* P values for the chi-square test.

† ‘Identifiable format for some but not all references’ and ‘No identifiable format for any reference’ were merged into one category when the chi-square test was performed.

‡ ‘101–1000’ and ‘More than 1000’ were merged into one category when the chi-square test was performed.

Table 4 shows associations of selected characteristics with the citations of references and systematic reviews of human studies. In the USA, books published after 2019 were more likely to cite systematic reviews than those published before 2019. The number of pages was positively associated with citing references and systematic reviews in Japan but not in the USA. The main theme was associated with the citation of references and systematic reviews in both the USA and Japan. In both countries, books with general health and other themes were more likely to cite references and systematic reviews. On the other hand, books with culinary recipes were less likely to cite references and systematic reviews. Books written by medical doctors were more likely to cite references than those written by authors who were not medical doctors in both countries (and also systematic reviews in the USA). The first author with a licence as registered dietitian was not significantly associated with the citation of references and systematic reviews in either country. No Japanese books written by registered dietitians cited systematic reviews. In all subgroups (book characteristics and degree and licence of the first author), the proportion of books which cited references did not differ between the USA and Japan, whereas US books were more likely to cite systematic reviews than Japanese books, except for registered dietitians with a small number of the books.

Table 4 Associations between selected characteristics and citations of references and systematic reviews of human studies in books about diet and health in the USA and Japan (n 100, each country)

* Significant differences between the USA and Japan in each subgroup (P < 0·05, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test).

† With ref, the number of books that cited references.

‡ P values for the chi-square test. When the expected frequency was less than five in more than 20 % of category values, Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used.

§ With SR, the number of books that cited systematic reviews of human studies (with or without meta-analyses) published in academic journals.

|| Median values of each country were used (312 for the USA and 168 for Japan).

¶ Others included ‘lose weight’, ‘primary or secondary prevention of specific diseases’ and ‘others’ in Table 1.

** Information about authors was derived from information in the book, summary pages of the books on the online bookstores or both without further examination using other sources (e.g. author’s web page). Books with no authors or editors or no information about authors were classified as having no affiliation and no licences of the first author.

Doctoral degrees among medical doctors in Japan and among registered dietitians in the USA were not associated with citations of systematic reviews. Among books written by authors who were not medical doctors, a doctoral degree of the first author was positively associated with the citation of systematic reviews in the USA but not in Japan (see online Supplemental Table 4).

Cohen’s κ coefficients for the selection or exclusion of books were 0·48 (95 % CI (0·31, 0·65)) for the US books and 0·59 (95 % CI (0·43, 0·75)) for Japanese books, indicating moderate agreement between two independent researchers. The number of books with disagreement and discussion needed during the process confirmed by the second researchers was not more than 10 for almost all variables, except for the main theme (52 for the US and 31 for Japan), a reference citation (9 for the US and 14 for Japan) (see online Supplemental Table 5).

Discussion

This study focused on references in popular books about diet and health in the USA and Japan. We found that the two countries had a similar proportion of books that cited references but differed in the type of sources cited as references and in reference format. Compared with the US books, Japanese books cited fewer references and were less likely to provide identifiable formats and to cite systematic reviews of human research.

Only a limited number of studies have investigated information in books about diet and health. Compared with the present study, a previous study reported a similar proportion of authors with medical doctor licences (33·7 %) and doctoral degree (6·0 %) among 100 popular US books based on sales ranking in 2008–2015(Reference Marton, Wang and Barabási29). That study also showed that only one book cited systematic reviews among seven books examined for references, whereas our present study found that nearly half of the US books cited systematic reviews. We also found that US books published after 2019 were more likely to cite systematic reviews than those before 2019, possibly due to the increasing number of systematic reviews published per year in the biomedical field(Reference Page, Shamseer and Altman40). The difference in the proportion of books that cited systematic reviews between the previous and present studies may be partly explained by publication year, in addition to the small number of books examined in the previous study.

Another previous study evaluated nutrition facts presented in a single best-selling book by searching peer-reviewed literature that would or would not support the facts(Reference Goff, Foody and Inzucchi41). The study found that only one-third of the nutrition facts was supported by peer-reviewed literature(Reference Goff, Foody and Inzucchi41). Although this previous and our present study differ in focus and the number of books examined, both suggest that nutritional information provided in popular US books is not necessarily based on scientific evidence.

Our study also showed that one-third of US books did not present references, and that half of US books did not cite systematic reviews of human research. This is comparable to findings from previous studies on online information about diet and health in English, although evaluation methods of the source of information in each study varied(Reference Haigh24,Reference Cai, King and Dwyer25) . A previous study on Wikipedia showed that only 28 % of references were peer-review journal articles, WHO studies or Cochrane Collaboration reviews among all references cited on nutritional information(Reference Haigh24). Another study reported that more than half of the online information about supplements and cancer did not provide appropriate references(Reference Cai, King and Dwyer25). Additionally, approximately two-thirds of claims about diet and health in UK newspapers were based on evidence with an insufficient grade(Reference Cooper, Lee and Goldacre42). A previous study also showed that some nutrition claims in newspapers were based on evidence with an insufficient grade(Reference Rabassa, Alonso-Coello and Casino43). Regarding other languages, most online health claims in Spanish to improve health through gut microbiome were supported by evidence described as low or very low certainty of the effect in systematic reviews(Reference Prados-Bo, Rabassa and Bosch44). Taking these previous and our present results together, books and online information about diet and health may frequently not cite sufficient references and may be supported by evidence with insufficient grade in English as well as in other languages.

Additionally, although systematic reviews would be useful to summarise a large body of evidence(Reference Cook, Mulrow and Haynes45), our results showed that nine US and twenty Japanese books citing research papers on humans did not cite systematic reviews. Previous studies have demonstrated that systematic reviews are less likely to attract media attention compared with original research(Reference Bartlett, Sterne and Egger46,Reference Prados-Bo and Casino47) . Overall, the insufficient referencing may ultimately be explained by the inability of information providers to understand scientific evidence. In the present study, even books written by medical doctors, nutritionists and authors with doctoral degrees did not necessarily cite systematic reviews. A previous study showed that less than 30 % of medical practitioners in Malaysia could correctly identify conclusions with the appropriate direction of effects and strength of evidence from systematic reviews(Reference Lai, Teng and Lee48). These findings suggest a need for authors to be competent in interpreting research evidence.

In the present study, although the USA and Japan had a similar proportion of books that cited references, we found differences between the countries in the number of references and in whether books cited systematic reviews. The large differences in citing systematic reviews may partly be attributed to differences in the number of Cochran systematic reviews published from the USA (n 1309) and Japan (n 81) among 9765 reviews(Reference Groneberg, Rolle and Bendels49). Additionally, among books with references, almost all US books provided identifiable information for all references, while only 64 % of Japanese books did so. Consistent with our findings, a previous study showed that much more online information on lung cancer provided references and sources for all content in the USA (approximately 50 %) than in Japan (approximately 20 %)(Reference Goto, Sekine and Sekiguchi28). These results suggest the need for health professionals, academics and governments, who engage in nutritional research, to encourage information providers and publishers to recognise the importance of presenting references when stating health information, especially in Japan.

In this study, Dietary Reference Intakes were more frequently cited in Japanese (23 %) than US books (12 %), whereas national dietary guidelines were more frequently cited in US books (19 %) than in Japanese books (4 %). The fact that only four Japanese books cited the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top may be partially explained by the fact that book authors did not know this guideline or did not recognise it as a scientific guideline. In fact, the development process of the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top described a smaller number of references(Reference Yoshiike, Hayashi and Takemi38) compared with the other three guidelines, namely Dietary Reference Intakes in both countries and Dietary Guidelines for Americans(37,50–52) . Nevertheless, these three guidelines were cited in only one-fifth of books. Further studies are needed to explore whether books provided inconsistent information on these guidelines or provided consistent information but did not cite them.

Our study showed that first author with a medical doctor licence was positively associated with the citation of references and systematic reviews in US books. The education system for medical training in the USA includes journal clubs and evidence-based training(Reference Ahmadi, McKenzie and Maclean53–Reference Annaswamy, Rizzo and Schnappinger55), which may contribute to the higher citation of systematic reviews. On the other hand, in Japan, first author with a medical doctor licence was associated with the citation of references but not with that of systematic reviews. Given that language is reported to be one of the most common barriers to evidence-based medical practice among Japanese residents(Reference Risahmawati, Emura and Nishi56), barriers to language may partly explain the fact that systematic reviews were rarely cited in Japanese books written by medical doctors, or in Japanese books written by other authors. US books written by registered dietitians tended to cite references more than books written by authors who were not registered dietitians, but the difference was not significant, possibly due to the small number of books written by registered dietitians. In Japan, 58 % of books written by registered dietitians cited any references, but none cited systematic reviews. A previous study suggested that institutions with public health nutrition programmes may not be active in research related to public health nutrition in Japan(Reference Shinozaki, Wang and Yuan57). This situation may have led to the lack of citation of systematic reviews in Japanese books written by registered dietitians.

This study was limited to an examination of whether the books cited references, and the type of sources cited as references. Given that several information quality assessment tools evaluate references of information(Reference Robinson, Coutinho and Bryden12–Reference Robillard, Jun and Lai14), referencing is considered a minimal requirement for reliable information but does not fully guarantee the reliability of the information. In previous studies, diet health claims extracted from a book, newspapers and websites were evaluated based on the scientific evidence that supported the claims(Reference Goff, Foody and Inzucchi41–Reference Prados-Bo, Rabassa and Bosch44). Although our present study did not evaluate the accuracy of the claims in the books, mainly because each book contained a large number of claims, this is an important area for future research.

Several limitations of this study warrant mention. First, the books selected may not be representative of popular books about diet and health in the USA and Japan. Due to the lack of a database on total book sales in all bookstores nationwide, this study selected books on the basis of their sales ranking among online bookstores with large sales(Reference Chevalier and Goolsbee31,33) . Additionally, it should be noted that the best-seller rankings of online bookstores do not reflect the number of sellers in physical bookstores. Second, because all examinations of books were conducted manually, we cannot rule out some errors. To reduce error, however, researchers confirmed all examinations in this study twice or more. Nevertheless, at least some variables should be interpreted with caution, particularly the classification of the main theme of the books, as researchers often interpreted this differently. Third, the study did not conduct a specific sample size calculation. Therefore, the results for factors associated with citations of references and systematic reviews should be interpreted with caution. Finally, this study focused on characteristics of books and did not examine the association of books with dietary behaviours of individuals. To improve dietary intake in both countries, which have their unique dietary concerns(Reference Murakami, Livingstone and Fujiwara58), further research is necessary to explore how the information derived from books impact the reader’s dietary behaviour.

In conclusion, this study showed that two-thirds of books about diet and health cited references in both the USA and Japan, and that Japanese books were less likely to cite systematic reviews. Additionally, one-third of Japanese books that cited references provided unidentifiable information for at least one reference. These findings suggest that reliable information may not be sufficiently provided in books about diet and health in the USA and Japan, especially in Japan. Our results suggest health professionals, academics and governments may have the need to encourage information providers to recognise the importance of appropriate references. Further research is also needed to examine other aspects of the reliability of information in books, including the accuracy of their content.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Tadasuke Taguchi, Medical Library, the University of Tokyo, and Nami Kemmotsu, Kagawa Nutrition University Publishing Division, for the selection of books. We also thank Guy Harris from Dmed (dmed.co.jp <http://dmed.co.jp/>) for editing drafts of this manuscript. Permission was obtained for this acknowledgement.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Institute for Food and Health Science, Yazuya Co., Ltd. and a grant (no. 22FA1022) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. The Yazuya Co., Ltd. and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest to report.

Authorship

F.O. contributed to the concept and design of the study and data collection and management, formulated the research, acquired the funding, analysed and interpreted the data, prepared the first draft of the manuscript and had primary responsibility for the final content. R.A. contributed to the concept and design of the study and data collection and provided critical input into the final draft of the manuscript. A.Y. and M.K. contributed to the design of the study and data collection and provided critical input into the final draft of the manuscript. R.O. and A.K. contributed to the data collection and provided critical input into the final draft of the manuscript. A.T., M.S. and M.M. conducted data collection. T.T. and Y.K. contributed to the development of the study design and provided critical input into the final draft of the manuscript. K.M. provided critical input into the final draft of the manuscript. S.S. contributed to the concept and design of the study and provided critical input into the final draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study did not include human subjects. All data were obtained from the books sold in the USA and Japan; ethics approval was not required.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980023002549