I Introduction

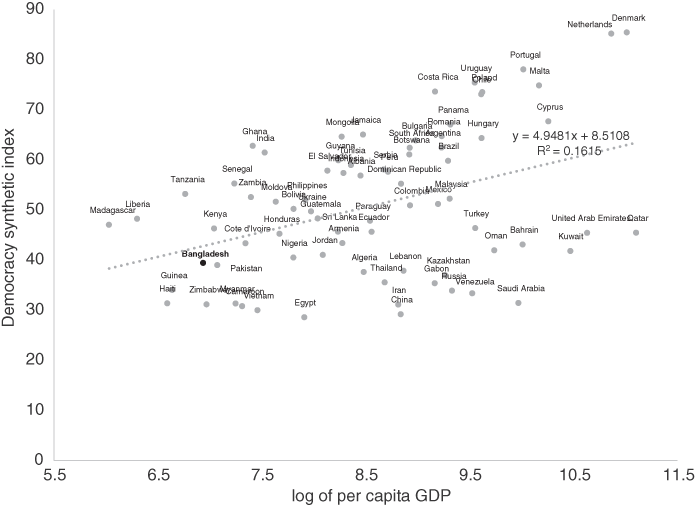

Bangladesh’s economic growth and development experiences over the past five decades, since independence in 1971, have generated much interest among academics and development practitioners both home and abroad. From its war-torn economy of 1972 until now, Bangladesh has been able to increase its per capita GDP in real termsFootnote 1 by 3.7 times (from US$ 460 in 1972 to US $1,700 in 2018), cut down the poverty rate from as much as 71% in the 1970s to 20.5% in 2019, become the second largest exporter of ready-made garments (RMG) in the world, and registered some notable progress in social sectors. In 2015, Bangladesh graduated from the World Bank’s classification of low-income country to the lower middle-income country category. Also, in 2018, the country met the first review of the three criteria required to graduate from the least developed country (LDC) status and is on track to meet the criteria under the second review in 2021 to finally graduate out of LDC status by 2024. At the same time, Bangladesh’s aforementioned development has happened in a context of a widely recognised weak institutional capacity. Bangladesh has almost always been ranked in the bottom part of most international rankings of governance indicators, as summarised in the Worldwide Governance Indicators database. Also, up to the late 2000s, its political climate was extremely tense, unstable, and often violent. All these factors have prompted some to term Bangladesh’s development the ‘Bangladesh paradox’ or the ‘Bangladesh surprise’.Footnote 2

Over the past five decades, the major factors behind Bangladesh’s growth and development achievements have been both internal and external. The major internal factors include an overall stable macroeconomy, large expansion of the private sector, robust growth in exports driven by the performance of the RMG sector, robust growth in remittances, resilient growth in the agricultural sector, a reasonably ‘working’ political climate over the last 12 years, some expansion of social protection programmes, and a wide coverage of social needs by non-governmental organisations (NGOs). The major external factors include favourable market access in major export destinations, reasonably stable economic conditions in Bangladesh’s major trading partner countries, Bangladesh’s stable political relations with neighbouring countries, some degree of regional cooperation in South Asia (especially with India), and Bangladesh’s ‘weak’ financial linkages with the global economy, which cushioned Bangladesh from the Global Financial Crisis. In 1990, Bangladesh was the 50th largest economy in the world (in international dollars). Impressively, by 2018, Bangladesh improved its position in this ranking to 33rd. According to PricewaterhouseCoopers (2019), it should become the 28th largest economy by 2030 and close to the 20th by 2050. The main question addressed in this chapter is whether the internal and external factors just mentioned will indeed keep pushing Bangladesh’s economy up at the same speed, or possibly even faster. More precisely, the issue considered is what constraints the economy may face in the future and whether further development can be achieved without a significant new direction in policy.

There are concerns that the weak institutional capacity of the country may work as a binding constraint as Bangladesh attempts to meet the stiff targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, and as it aspires to become an upper middle-income country by 2031. Moreover, the dividends from the so-called ‘Bangladesh surprise’ are likely to be on a decline as the country is confronted by several serious economic challenges. These include the slow progress in the structural transformation of the economy, the lack of export diversification, the high degree of informality in the labour market, the slow pace of formal job creation, the poor status of physical and social (i.e. education, healthcare) infrastructure, the slow reduction in poverty and rising inequality, and the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Against this backdrop and keeping in mind the ambitious development targets the country wants to meet in the next two to three decades, this chapter analyses the major development achievements of the Bangladeshi economy until today and seeks to identify the major challenges it will have to address in the future. Whether these challenges can be overcome, and which reforms can be undertaken for this to happen, depends in turn on the institutional context of the country. This particular aspect will be considered in the institutional diagnostic chapter at the end of the volume, after a deeper reflection on Bangladesh’s politico-economic institutions, through the analysis of key economic sectors and major socio-economic issues.

Focusing exclusively on economic and social issues, this chapter first analyses the sources of growth and possible limitations of the present development regime (Section II). It then evaluates the financing constraints faced by the economy in general, and by the public sector in particular (Section III). The next sections (Sections IV–VI) focus on sources of concern in social and environmental areas and the COVID-19 crisis. The conclusion summarises the main results of this chapter.

II Sources of Growth and Possible Limitations of the Present Development Regime

In this section, economic growth in Bangladesh is first analysed at the aggregate level, before considering the structural evolution of the economy, the key role played by trade, and the constraints arising from lagging infrastructure and progress in the business environment.

A Aggregate Growth

The long-term trend in the GDP growth rate shows that Bangladesh has steadily increased its rate of growth over the past 47 years, since independence in 1971 (Figure 2.1). Starting from a highly volatile growth rate in the 1970s, growth became more stable and slightly faster in the 1990s and has accelerated since the turn of the millennium. From an average rate equal to or below 4% per annum in the 1970s and 1980s, growth accelerated and shot up to over 5% in the 2000s, then exceeded 6% for several years during the 2000s, and has crossed the 7% mark in recent years. Bangladesh has been able to increase the average GDP growth rate by 1 percentage point in each decade since the 1990s. In 2018, the country achieved its highest growth rate in the past four decades: 7.9%.Footnote 3 In Figure 2.1, the steps indicate the average growth rates of the decades, and the highlighted years indicate the years of political transition in Bangladesh.Footnote 4

Figure 2.1 Real GDP growth rate in Bangladesh.

GDP per capita has grown less rapidly because of population growth, but because the latter has significantly slowed down over the last 40 years, the growth acceleration is even more noticeable for GDP per capita. The 10-year average growth rate increased from 1.5% in the 1980s to more than 5% over today.

Compared to other developing countries, in international purchasing power (purchasing power parity 2011 US$), Bangladesh’s per capita GDP was US$ 3,880 in 2018, around 1.5 times the average for LDCs, 57% of the average for lower middle-income countries, 50% of the South Asian average, and 23% of the average for upper middle-income countries. In terms of growth, however, Bangladesh has done substantially better than the average country in all of these groupings.

Interestingly enough, the vigorous acceleration of GDP growth since 1990, from 4% to 6.6%, is in line with the increase in the share of investment in GDP. The investment to GDP ratio was 17.5% around 1990. It increased regularly since then and reached 31% in 2018. However, two remarks are in order here. First, further growth acceleration, as targeted by the present government, may require a substantial increase of the investment to GDP ratio. The Perspective Plan 2041 targets an 8.5% real GDP growth rate by 2025. Given an average incremental capital output ratio of 4.3 for the period 2014–2018, the investment to GDP ratio should be more than 36% by 2025, which represents a growth rate for investment that is much faster than what has been observed in the recent past. Second, an important aspect of Bangladesh’s investment regimes in the 1990s and 2000s is that the major contribution to the growth of the investment to GDP ratio came from the rise in private investment and its share in total investment. However, the GDP share of private investment has remained stagnant in recent years, so the growth of the overall GDP share of investment has been mainly due to its public component.Footnote 5 The stability of the ratio of private investment to GDP might make it possible to sustain present growth rates but may be a concern for further acceleration.

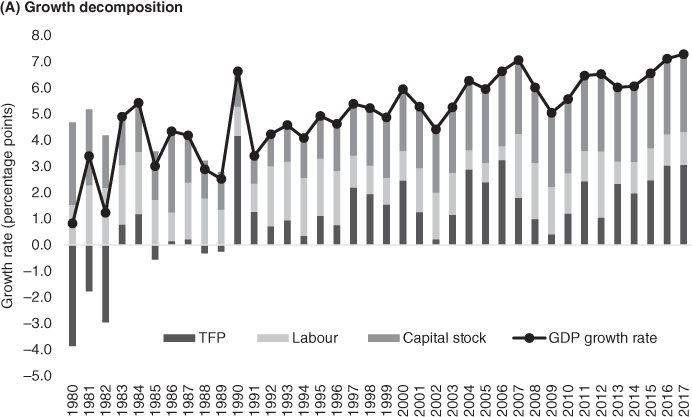

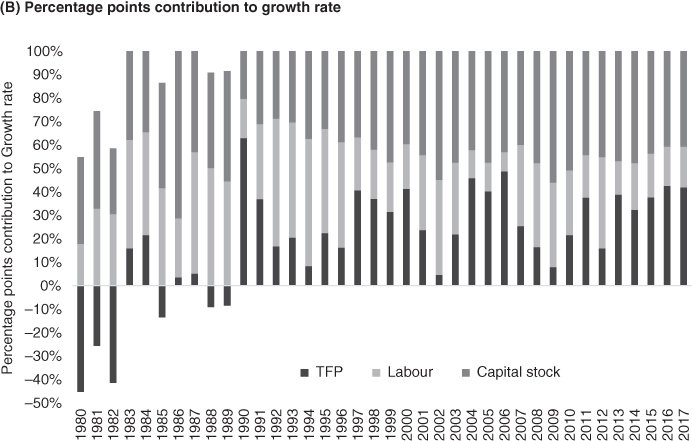

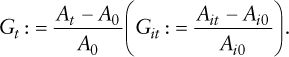

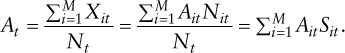

Conventional growth accountingFootnote 6 is helpful in regard to obtaining insights into the aggregate sources of GDP growth, that is what portion is derived from capital accumulation, the growth of the labour force, and total factor productivity (TFP) in general. Figure 2.2 shows the result of that decomposition on an annual basis since 1980, although the 1980s may not be relevant given that this was a very tumultuous period from both a political and an economic point of view.

A. Growth decomposition.

B. Percentage points contribution to growth rate.

Figure 2.2 Growth decomposition in Bangladesh (1980–2017).

Over the next three decades, capital accumulation was, on average, the most important factor of growth. This dominance increased over time, in line with the acceleration of investment just mentioned. The contribution of labour steadily declined over time, in part because of slowing population growth, but above all because capital grew much faster. TFP growth is the residual: it represents the productivity gains that were independent of the accumulation of capital, making up a little less than one-third of total GDP growth.

Subtracting the contribution of labour to GDP growth in the preceding decomposition is equivalent to considering the growth of the average productivity of labour: that is, GDP per worker. It has steadily increased over time.

B Structural Transformation

Part of the TFP growth in the preceding decomposition is caused by structural changes taking place in the economy. Over time, the allocation of production factors changes with net movements across sectors of activity. If productivity is not the same in the sectors of origin and in the sectors of destination, these movements affect the overall level of productivity in the economy. This mechanism has been seen as a major driver of development ever since the work of Lewis (Reference Lewis1954). However, it has recently been found that, since the 1990s, this process has worked in the opposite way. Working on sub-Saharan African and Asian countries, McMillan and Rodrik (Reference McMillan and Rodrik2011) found that structural change in those countries had a negative impact on overall labour productivity. However, Bangladesh did not follow such a pattern in the past, and this remains the case today.

Table 2.1 shows the evolution of the GDP and employment structure by sector of activity between 1991 and 2018. The contribution of agriculture, both to GDP and employment, sharply declined during 1991 and 2018, and those of non-agricultural sectors, especially the services sector, increased. Comparing the structure of GDP and that of employment, it is readily apparent that in 1991, productivity was the lowest in agriculture and the highest in ‘other industry’, followed by services. This means that net labour movements have been from low-productivity to high-productivity sectors, that is mostly from agriculture to services and ‘other industry’. Structural change has thus had a positive effect on the overall labour productivity in the economy, in line with Lewis (Reference Lewis1954).

Table 2.1 Structural change in the economy (percentage share of total)

| Broad sectors | GDP | Employment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 2018 | 1991 | 2018 | |

| Agriculture | 31.7 | 13.1 | 69.5 | 40.1 |

| Manufacturing | 13.9 | 17.9 | 12.4 | 14.2 |

| Other industry | 7.2 | 10.6 | 1.2 | 6.3 |

| Services | 47.2 | 58.4 | 16.9 | 39.4 |

At the same time, Figure 2.3 shows that in the 1990s, labour productivity increased overall in all sectors of activity except ‘other industry’, possibly because of structural changes within that sector. These sectoral productivity increases thus provided a second source of overall productivity gain, in addition to structural change.

Figure 2.3 Bangladesh’s labour productivity by sector and for the whole economy (GDP per worker 2018 = 100).

Figure 2.3 also shows some interesting short-run variations in productivity gains. For instance, the 1991–1995 period exhibited a huge increase in manufacturing productivity – a doubling in four years – apparently precisely at the time the RMG sector was taking off. It is also striking that productivity did not change in the four sectors of activity between 1995 and 2005, but overall productivity increased because of net labour movements from agriculture to other sectors, that is structural change.

Avillez (Reference Avillez2012) provides an interesting method for decomposing aggregate labour productivity gainsFootnote 7 into structural change and within-sector productivity growth. This distinguishes three components: (1) the within-sector effect (WSE) reflects the overall impact of productivity growth within individual sectors on aggregate productivity; (2) the static reallocation effect (SRE, Denison effect) captures the impact of the reallocation of employment from less productive to more productive sectors (i.e. it arises from sectoral differences in initial productivity levels); and (3) the dynamic reallocation effect (DRE, Baumol effect) describes the impact of reallocating employment to sectors with fast- or slow-growing productivity (i.e. this results from asymmetric productivity growth rates across sectors).Footnote 8 The last two effects correspond to the impact of structural change on growth.

Table 2.2 presents the decomposition of labour productivity growth in Bangladesh into WSE, SRE, and DRE using data for the four sectors appearing in Table 2.1 and three approximately 10-year periods. It appears that while total labour productivity growth doubled after 2000 compared to what it was in 1991–2000, the contributions of WSE, SRE, and DRE changed quite dramatically across the periods. WSE increased by more than 10-fold between the first and the last sub-periods, while structural change, that is the sum of SRE and DRE, which was strong and approximately constant in the first two sub-periods, declined significantly in the last decade. Interestingly, the dynamic productivity effect, DRE, was strongly negative in the 1990s, suggesting that labour shifts during that period were towards sectors with higher but slow-growing productivity. That effect then practically vanished.

Table 2.2 Decomposition of labour productivity growth in Bangladesh

| 1991–2000 | 2001–2010 | 2011–2018 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | WSE | SRE | DRE | Total | WSE | SRE | DRE | Total | WSE | SRE | DRE | |

| GDP per worker | 0.166 | 0.031 | 0.246 | –0.110 | 0.356 | 0.111 | 0.261 | –0.016 | 0.338 | 0.240 | 0.077 | 0.020 |

Note: GDP per worker is in purchasing power parity constant 2011 international $.

Figure 2.4 suggests that in the recent decade, the major contribution to labour productivity comes from WSE (71%), followed by SRE (23%) and DRE (6%). This suggests that productivity growth within individual sectors, rather than the reallocation of employment from less productive to more productive sectors and reallocating employment to sectors with growing productivity, has been the driving factor behind labour productivity growth during the 2011–2018 period. What is surprising in that evolution, and in the difference compared to the previous period, is that with agriculture still accounting for 40% of the labour force and having a substantial productivity gap, there would seem to still be a huge potential for structural change. Productivity has increased very quickly in the service sector during the last decade, with that sector being responsible for the high WSE effect in that sub-period. But it follows that it created less jobs than in the previous sub-periods, thus weakening labour movements and the structural change effect on GDP per worker, or closely related GDP per capita.

Figure 2.4 Percentage contribution to labour productivity growth in Bangladesh.

To understand better the reason for this slowing down in structural change requires disaggregating the services sector, which comprises very different types of activity, ranging from financial services to informal retail trade or ancillary jobs. It cannot be excluded that what is being observed is a mounting productivity gap within that sector that hides a falling gap between agriculture and low-productivity service activities, and thus a weakening of incentives to move away from agriculture, while huge productivity gains and faster growth take place in high-productivity services like finance. Unfortunately, employment data do not allow for a more detailed analysis that would make it possible to test that hypothesis.

C Trade

After independence in 1971, Bangladesh adopted a highly restricted trade regime that was characterised by high tariffs and non-tariff barriers and an overvalued exchange rate system, in support of the Government’s import-substitution industrialisation strategy. This policy was pursued with the aim of improving the country’s balance of payment position and creating a protected domestic market for manufacturing industries (Bhuyan and Rashid, Reference Bhuyan and Rashid1993). Then, in the mid-1980s, the trade regime registered a major shift, when a moderate liberalisation reform was initiated. Yet the boldest transition from a protectionist stance to a freer trade regime took place in the early 1990s, which led to a drastic reduction in the average tariff rate, from as high as 105% in 1990 to 13% in 2016 (Raihan, Reference Raihan2018a).

The liberal import policies during the 1990s and onwards led to a fast growth of imports. Figure 2.5 shows that the import to GDP ratio increased from 13% in the early 1990s to 23.5% today. The export to GDP ratio had started to rise by 1990, from a very low level of slightly above 5% of GDP in the 1980s, but it then closely followed imports, reaching an all-time peak of 20% in 2010. The trade deficit is endemic to the Bangladesh economy, even though it has been rather stable over time, fluctuating at around 5%, with some widening since the mid-2000s. In this long-run ascending trade perspective, there may be some concern with respect to the substantial decline in the GDP share of both imports and exports over the last five years. Is this the result of temporary shocks or the sign of deeper structural changes?

Figure 2.5 Foreign trade.

Over the years, the composition of imports has also changed in Bangladesh. There has been a move away from the heavy dominance of food imports in the early 1970s to industrial raw materials and machinery today. The change in favour of industrial raw materials and capital machinery is partly linked to the rapid expansion of the manufacturing sector, particularly RMG exports, which is the dominant feature of the Bangladeshi economy over the last four decades.

Bangladesh’s fast export growth since the late 1980s has indeed been overwhelmingly driven by the dynamism of the RMG sector alone. While the export basket was heavily dominated by jute and jute products in the early 1970s, the composition of exports in Bangladesh has evolved steadily in favour of RMG products. Today, they constitute more than 80% of export earnings. The drastic change in the import mix, as well as the spectacular surge of RMG manufacturing exports, bear witness to the structural transformation of Bangladesh’s economy and the role played by foreign trade.

The growth of Bangladesh’s RMG exports had its origins in the international trade regime in textiles and clothing, which, until 2004, was governed by Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) quotas. This quota system restricted competition in the global market by providing reserved markets for numerous developing countries, including Bangladesh, where textiles and clothing items were not traditional exports. The duty-free access of Bangladesh’s RMG products to the European Union (EU) has also greatly supported the growth of the sector. Yet the surge in RMG exports from Bangladesh took place precisely at the time of the extinction of the MFA regime and its successor Agreement on Textile and Clothing: that is, at the time the international market was liberalised and the RMG Bangladeshi sector appeared as particularly competitive relative to other providers in developing countries (outside China).

The growth of RMG exports has been one of the main growth drivers of Bangladesh’s economy over the past three decades. Although the sector directly contributes to only a little more than 6% of GDP, its indirect contribution is much larger: accounting for both backward and forward linkages, it accounts for at least twice as much. With exports increasing at an average annual rate of 12% over the last two decades, and probably more for its RMG component, the sector may have directly contributed to close to 1.4% GDP growth during that period. Yet such an estimate does not include the indirect effects on aggregate demand, on easing the foreign currency constraint, and on investment incentives. The econometric exercise reported in Annex 2.3 suggests an even larger contribution when all these effects are accounted for. With an estimated elasticity of GDP to the volume of exports of 0.22, a 12% growth of exports generates a 2.6% increase in GDP – a little less than half the average growth rate since 2000.

Despite this impressive growth record, it bears emphasis that the export base and export markets have remained rather narrow in Bangladesh, which is a matter of great concern. Undiversified exports, both in terms of market and product range, are likely to be much more vulnerable to external and internal shocks than well-diversified exports. Despite various incentives provided by trade policy reforms, Bangladesh’s manufacturing sector seems to have failed until now to develop a diversified export structure. Bangladesh’s export markets have been highly concentrated – North America and the EU being its major clients. Bangladesh’s growth is thus heavily dependent on economic activity in these two parts of the world. As far as the export product range is concerned, UNCTAD’s export concentration index suggests that Bangladesh’s export concentration has increased over the last two decades. In fact, it is much higher today than the averages for LDCs, lower middle-income countries, upper middle-income countries, and South Asian countries.Footnote 9

Despite a very high share of manufacturing exports in total merchandise exports, the export basket of Bangladesh thus remains highly concentrated around low-complexity products with lower growth prospects in world markets. A measure of the complexity of the economy is the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) of the Centre for International Development at Harvard University, which measures the knowledge intensity of an economy by considering the technical knowledge that is incorporated into the products it exports. In this respect, Bangladesh performs very poorly, with an ECI that has deteriorated over time. Following the current view on the relationship between economic complexity and the level of income, Bangladesh’s growth prospects would not seem favourable, as a low ECI would be compatible with a relatively low level of GDP per capita.Footnote 10

On the import side, it must be stressed that, despite the liberalisation of tariffs, Bangladesh’s average applied tariff rate in 2016 was the highest in South Asia, and much higher than those of the countries in Southeast Asia. Also, in 2016, the share of tariff lines with international peaks (rates that exceed 15%) in total tariff lines was as high as 39%, which was much higher than most of the South Asian (except Nepal and Pakistan) and Southeast Asian countries.Footnote 11 Given this scenario, there seems to be room for further tariff liberalisation in Bangladesh as part of a broader trade policy reform aimed at accelerating export growth and export diversification (Raihan, Reference Raihan2018a; Sattar, Reference Sattar2019).

The need to diversify exports thus appears as a key policy agenda in Bangladesh. It is essential to sustain long-term growth and employment creation, as it is far from clear that Bangladesh will be able to keep increasing its global market share in low value–added RMG products as fast as it has done in the past. Low-wage competitors are appearing in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, Ethiopia, and the whole industry is mechanising so that low labour costs may not be as strong a comparative advantage as before, and, domestically, the sector will provide less jobs. Foreign clients of Bangladeshi RMG firms are also more and more attentive to the labour conditions among their suppliers, particularly after the 2013 Rana Plaza accident that cost the life of a thousand employees. At the same time, the pressure for higher wages and better labour conditions is increasing in the country, making the RMG sector less competitive internationally.

D Remittances and Foreign Direct Investment

Remittances can be considered the second major driver of growth in Bangladesh. Figure 2.6 shows the evolution of remittances sent back home by Bangladeshi workers employed abroad since the mid-1970s. Starting from a low base, remittances increased at slow rates until the turn of the millennium. Since then, however, they have increased at very sharp rates, reaching US$ 14 billion around 2013 but then remaining roughly constant. In terms of GDP, they went up from 1% around 1995 to 10% in 2008–2012, falling back to 6% today. A reduction of transaction costs and remitting delays, but above all the fast-growing demand of foreign workers in the Gulf, where the net inflow of migrants multiplied by 5 between 2000 and 2010, made a major contribution to the increase in the flow of remittances.

Figure 2.6 Remittances and foreign direct investment.

Remittances contribute to domestic growth essentially by increasing aggregate demand, that is domestic spending, while at the same time eliminating foreign currency bottlenecks that could constrain an increase in production. Other things being equal, the same increase in spending would not have resulted in more production if it had a purely domestic origin, because of the constraint arising from the financing of imported raw materials and equipment required by any increase in domestic output. Thus, one may estimate that, with an average annual growth rate of 11% between 2000 and 2018, remittances have contributed to roughly 1 percentage point of annual GDP growth.Footnote 12 The econometric exercise reported in Annex 2.3 suggests a long-run elasticity of GDP to real remittances of 0.14. When all indirect effects are accounted for, the contribution of remittances to GDP growth is thus 1.5% per annum on average. Together with export growth, they thus generate roughly two-thirds, that is 4.1% annually, of overall growth.

Foreign direct investment represents another regular inflow of foreign currency that has the potential to accelerate domestic growth. In the case of Bangladesh, however, that contribution has been only marginal. If the amount of foreign direct investment has increased since the mid-1990s, it has represented only around 1% of GDP after the mid-2000s, and a little more than that over recent years. This does not compare well with what is observed in LDCs (3.3% on average), or in Southeast Asian manufacturing exporters such as Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam – all RMG competitors of Bangladesh – where the foreign direct investment to GDP ratio is above 6%. At the same time, Bangladesh’s domestic investment effort is larger and more dynamic.

E Infrastructure and Megaprojects

If Bangladesh does not rank high either in the availability or quality of its infrastructure according to the World Economic Forum 2019 Global Competitiveness Index, its overall score is nevertheless comparable to those of African countries at a comparable level of GDP per capita (Ghana, Kenya) and not much below dynamic middle-income industrialising Asian countries except Vietnam. However, the situation differs depending on the kind of infrastructure being considered. If Bangladesh compares well with other lower-middle income countries in transport infrastructure, the gap is more pronounced with respect to power and water. True, 80% of the population now has access to electricity, a spectacular progress mostly achieved over the last 10 years. But with an average consumption of 330 kWh per person and per year, Bangladesh keeps lying well below the rest of South Asia – except Nepal –, industrialising Asia, and even some African country like Ghana. Moreover, outages in urban areas are still frequent, which entails substantial costs. As far as access to safe drinkable water is concerned, on the other hand, the situation is definitely worse in Bangladesh than in most countries at a comparable level of development.

As in other developing countries, considerable efforts are still to be made to provide to economic agents the infrastructure that development, especially industrialisation, imperatively requires. Lately, these efforts have taken the form of a few ‘mega-projects’ meant to accelerate the pace of development and make it more transformative. These essentially are major infrastructure projects, with complex logistics, high technological requirements, and very substantial funding needs. Undertaken in key sectors such as transportation, energy, seaport, airport, mining, etc.,Footnote 13 they are intended to have a significant impact on the country’s development through job creation, enhanced connectivity, regional trade facilitation, geographic integration, and energy provision.

These mega-projects also raise several concerns, which relate to: (i) their financing; (ii) their implementation, including construction delays and their final cost; and (iii) their political significance within the context of Bangladesh’s political economy.

The total cost of the seven largest mega-projects has been estimated at USD 31.2 billion,Footnote 14 of which only 9.9 billion was funded on government funds. The rest was mostly funded by loans, part of which from foreign donors. The foreign debt of Bangladesh was significantly affected by these projects, and the issue arises of whether their return will cover reimbursement. In this regard, the systematic over-running of both construction delays and costs may be a worry. They stem from a general lack of experience in dealing with such large-scale projects but also to a lack of transparency and political pressure in selecting the implementing agency, and in procurement. In effect, many of implementation issues reflect complex dynamics of rent generation and sharing which are typical of large economic projects (Hassan and Raihan Reference Hassan, Raihan, Pritchett, Sen and Werker2018).

Even though their economic utility is not in doubt, the multiplication of these mega-projects owes much to political factors. These include vested interests created by a range of stakeholders benefiting from these projects, their multiplier effects, the clout and image associated in public opinion with such prestigious project but also the relative ease in spending money quickly, including the rent-sharing opportunities that it creates. In this respect, the key role that the Bangladesh Army has played in some of the projects may be underscored, as it may have been a way of distracting it from politics.

In summary, the recent and spectacular expansion in infrastructure projects has the potential to deliver significant economic development impacts, alleviating some key binding constraints, in terms of power, transport, and connectivity. Yet, management flaws and rent-seeking behaviour made those projects notably more costly than they should have been.

F Bangladesh’s Growth Engines and the Possible Limitations of Its Present Development Regime

Such are Bangladesh’s achievements and challenges on the economic growth front, as they appear from a thorough review of the pace of the accumulation of essential production factors, their allocation, and productivity gains. The main lesson to retain from this review is the major role of RMG exports and remittances in explaining the overall satisfactory growth performance over the last two or three decades. Exports and the RMG sector have been particularly important in making the economy more dynamic, accelerating structural change, increasing productivity, and incentivising investment. Remittances have contributed to the growth of aggregate demand and the response of the domestic production machinery. Both exports and remittances have eased the foreign currency constraint that most developing countries at Bangladesh’s development stage are confronted with. Together, RMG exports and remittances may have been responsible for two-thirds of the overall growth in GDP per capita over the last 20 years or so, the remaining third consisting of productivity gains in other sectors and the net movement of workers away from low-productivity agriculture.

The role played by manufacturing RMG exports in Bangladesh is in many respects remarkable. At the same time, the present situation hides weaknesses. On the one hand, there seems to be some anomaly in observing such a high concentration of exports in a country where apparel manufacturing export is already a mature although still growing activity. On the other hand, the international context, which has been favourable to Bangladesh RMG exports until now might become less so in the years to come.

On the first point, a common observation among countries whose development is based on manufacturing exports is precisely the fast diversifying array of products they offer. The rationale behind this diversification is the inherent complexity of manufacturing products in comparison with raw materials or commodities, which leads to progress taking place at both the intensive and the extensive margin that is exporting more of the same but also closely related products upstream or downstream as well as integrating into global value chains related to initial exports.Footnote 15 Such an evolution does not seem to take place in Bangladesh, and it will be important to understand why.

On the future of RMG exports, several obstacles were already mentioned: the appearance of low-labour cost competitors in both East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the pressure to improve labour conditions and its impact on cost-competitiveness or the automation of production which also reduces Bangladesh’s comparative advantage. To these, should be added the forthcoming graduation of the country from the LDC status, which granted to it some trade preferences in both the EU and the United States.

If not able to increase its global market share, the RMG sector will be, at best, growing as foreign demand, the same being true of migrant remittances. This means that, if Bangladesh wants to maintain its fast pace of development, it has to substantially diversify its economy, and its exports in the first place.

Another limitation that needs to be mentioned, which has been absent from this review: land. It indeed bears emphasis that, except for a handful of tiny countries, Bangladesh is the country with the highest population density on earth: Singapore and Hong Kong have a higher population density, but Bangladesh has 20 or 30 times more inhabitants. Even though it is difficult to quantify the impact of this on growth, it is difficult to imagine that the (un)availability of land is not exerting a severe constraint on Bangladesh’s development. This makes especially important the procedures for the allocation of land among its various economic uses. This point will be dealt with in some detail in the chapter on land in this volume.

III The State and the Financing of the Economy

State capacity is not a factor of production, properly speaking, and it would be difficult to provide a quantitative measure of it. Yet the ability of the state to coordinate the activity of private economic actors and, most importantly, to provide the public goods that are needed for the smooth working of the private sector is essential. This section reviews the financial aspects of the public sector in Bangladesh: that is, both its capacity to cover the public expenditures necessary for the development of the country and its ability to finance state-owned and private enterprises through public financial entities or the supervision of the private banking sector. It will be seen that, in both cases, the diagnostic is rather unfavourable. When considering the overall financing of the economy, however, a rather favourable feature is Bangladesh’s autonomy with respect to foreign financing.

A Public Finance and State Capacity

The key function of the government sector is public revenue and expenditure management, with the aim of providing the public goods needed by the population and required for accelerating economic growth, reducing infrastructure gaps, promoting investment, and ensuring an efficient redistribution of resources to alleviate poverty and reduce inequality.

Table 2.3 presents the performance of key fiscal indicators in Bangladesh between fiscal years 2013/14 and 2017/18. Focusing first on the revenue side at the top of the table, two features are striking. First, government revenues are extremely low. Second, they show no sign of growth, relative to GDP. With a 10% tax to GDP ratio, Bangladesh is among the countries with the lowest taxes in the world. Unlike some countries that can count on other sources of public revenues, for instance through royalties on exports of natural resources, non-tax revenues add only marginally to the fiscal space in Bangladesh. On several instances, the Government announced major tax reforms that would drastically increase the tax/GDP ratio. Until now, however, such reforms have failed to materialise.

Table 2.3 Government revenue and expenditure in Bangladesh

| Fiscal year | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2017/18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (as % of GDP) | |||||

| Revenue and grants | 10.92 | 9.77 | 10.09 | 10.22 | 9.66 |

| Total revenue | 10.45 | 9.62 | 9.98 | 10.18 | 9.62 |

| Tax revenue | 8.64 | 8.48 | 8.76 | 9.01 | 8.64 |

| National Board of Revenue (NBR) tax revenue | 8.29 | 8.17 | 8.44 | 8.69 | 8.31 |

| Non-NBR tax revenue | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.32 |

| Non-tax revenue | 1.81 | 1.13 | 1.22 | 1.17 | 0.99 |

| Grants | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| (as % of GDP) | |||||

| Total expenditure | 14.01 | 13.46 | 13.76 | 13.64 | 14.30 |

| Non-development expenditure including net lending | 9.60 | 9.27 | 9.06 | 9.18 | 8.87 |

| Non-development expenditure | 9.01 | 8.53 | 9.05 | 8.90 | 8.51 |

| Revenue expenditure | 8.23 | 7.84 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 7.95 |

| Capital expenditure | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.56 |

| (as % of GDP) | |||||

| Net lending | 0.60 | 0.74 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.37 |

| Development expenditure | 4.40 | 4.19 | 4.70 | 4.45 | 5.43 |

| Annual Development Programme (ADP) expenditure | 4.12 | 3.98 | 4.58 | 4.26 | 5.31 |

| Non-ADP development spending | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.12 |

| (as % of GDP) | |||||

| Overall balance (excl. grants) | –3.56 | –3.85 | –3.78 | –3.45 | –4.68 |

| Overall balance (incl. grants) | –3.09 | –3.69 | –3.67 | –3.42 | –4.64 |

| Primary balance | –0.99 | –1.65 | –1.76 | –1.62 | –2.78 |

| (as % of GDP) | |||||

| Financing | 3.09 | 3.69 | 3.67 | 3.42 | 4.64 |

| External(net) (including market borrowing) | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 1.14 |

| Loans | 0.89 | 0.79 | 1.13 | 0.95 | 1.47 |

| Amortisation | –0.64 | –0.47 | –0.39 | –0.36 | –0.33 |

| Domestic | 2.84 | 3.37 | 2.93 | 2.83 | 3.50 |

| Bank | 1.35 | 0.03 | 0.29 | –0.42 | 0.52 |

| Non-bank | 1.49 | 3.34 | 2.64 | 3.25 | 2.98 |

Note: Net financing includes market borrowing. Bank includes secondary market.

The tax system generates little revenue and, on top of that, it is highly distortive and regressive. Less than a third of government revenue comes from direct taxes and only half of that is from personal income tax. As far as the latter is concerned, a large number of potential taxpayers, including many ultra-rich people, remain outside of the tax net or pay a small amount of taxes. Also, several economic sectors that are capable of paying taxes are either fully exempted or enjoy substantial tax rebates. By contrast, indirect taxes (value-added tax, excise taxes, and import duties) that fall on the whole population and are on balance regressive account for the bulk of government revenues.Footnote 16 Overall, these features result in a tax system that is unable to raise enough revenue to finance the country’s development, as non-tax revenues are marginal; that is inefficient and distortive of economic activity because tax privileges are granted to specific sectors or firms; and that is inequality enhancing.

The situation is not different on the expenditure side of the general government account. Even though the total spent is substantially higher than the revenue figure, Bangladesh’s government expenditures are lower, in relation to GDP, than in many countries. Recurrent expenditures, for instance, amount on average to 9% of GDP, approximately the same level as revenues. Over the recent period, only 10 countries in the world have exhibited such a low level. Combined with the level of GDP per capita, this suggests that the provision of public services, as measured by spending per capita, is most likely to be of worse absolute and relative quality in Bangladesh than in most countries in the world. Such a state of affairs can only have negative implications for both current economic growth and poverty reduction but also for future growth and economic welfare, as human capital formation is necessarily affected by this lack of resources.

It is difficult to make a judgement about the size of development expenditures in Bangladesh in comparison to other countries, and similarly about public investment, as no recent dataset with comparable international data is available. From what can be gathered from work referring to the mid-2000s, Bangladesh would seem close to the international norm, but somewhat below it.Footnote 17 Yet what is most striking is the fact that the financing of the investments scheduled in the Annual Development Programme, a multi-year development plan, is almost fully funded by government debt. Indeed, over the last five years, development expenditures represent on average 4.7% of GDP, whereas the deficit of the general government is slightly below 4%.

This deficit remains in relatively reasonable territory, yet it contributes in normal times to an increase in the public debt relative to GDP: as Table 2.3 shows, the Bangladesh Government exhibits a primary deficit, that is after taking into account the payment of interest on the outstanding debt, which is above 2% of GDP and has been clearly increasing over recent years. It is also interesting to note that one-quarter of the loans to the Government originate abroad and three-quarters originate domestically. Because of this heavy reliance on domestic lending, it cannot be discarded that public investment and the lack of fiscal space due to a low tax to GDP ratio is crowding out private investment.

To conclude this brief review of the government sector, it is worth mentioning that a recent study by the General Economics Division of the Planning Commission of Bangladesh (2017), estimated that the tax to GDP ratio in Bangladesh needs to be progressively increased to 16–17% by 2030 in order to achieve the major SDGs. This figure shows the huge revenue increase that the country needs to reach its announced development goals. The comparison with today’s resources shows that such a target is ambitious but not unachievable if growth continues at the current pace. However, three years after this statement of goals, no real change is observed.

B External Financing of the Economy

The evolution of the external financing of the Bangladeshi economy is summarised in Figure 2.7. Since 1990, the balance of the current account has fluctuated over time in a rather narrow interval around equilibrium. Over the last two decades, it has been mostly on the positive side, except for the last two years, where it shows a more pronounced deficit. Overall, it is thus fair to say that the financing of the Bangladesh economy has been mostly domestic. This is well reflected in a debt to GDP ratio which is today around 20%, after peaking at close to 50% in the tumultuous 1980s and early 1990s.

Figure 2.7 Current account, foreign debt, and foreign aid as a share of GDP, 1990–2018.

This does not mean that the economy is free from financing from the rest of the world. Actually, it can be seen in Figure 2.7 that the trade balance has systematically been negative ever since independence, with a deficit ranging from 5% to 10% of GDP. Historically, the financing of that deficit has been covered by the remittances of Bangladeshi workers abroad and foreign aid. Over time, foreign aid dwindled, and current grants are today almost negligible – although the country still benefits from concessional loans from donors. Aid grants became unnecessary when remittances surged after the turn of the millennium, as was seen earlier, whereas concessional loans mattered more for technical assistance than for financing. At the same time, however, Bangladesh has become extremely dependent on the economy of those countries that host its migrant workers, led by the Gulf countries. However, as remittances started to fall rather drastically around 2015, precisely at the time oil prices plummeted and the Gulf countries cut down on their public spending. Two years later, this entailed a higher than normal deficit of the current account.

The rather balanced external position of Bangladesh’s economy does not mean that the country did not have to request the help of the IMF on a few occasions over the past two decades. The first time was in 2001 after several years of a negative balance of the current account that had led the country to run down its reserves of foreign exchange. A stabilisation programme was then signed with the IMF for the 2003–2006 period, which came with some conditionalities relating to the management of state-owned companies and state-owned banks, tax revenues, and more general governance issues.Footnote 18 In 2011, an ‘extended credit facility’ was requested due to the impact of the European crisis on Bangladesh’s balance of payment. It is thus not the case that the country is fully autonomous with respect to foreign financing. If they are strong and persistent, external shocks require payment facilities of the type provided by the IMF.

C Domestic Financing: The Banking Sector and the Weak Regulation of the Financial Sector

Two indicators can be used to evaluate the degree of development of the financial sector of a country: the broad money (M2) to GDP ratio, which measures the depth of the financial sector; and the domestic credit to the private sector by banks as a share of GDP, which measures the lending activity of the banking sector. These indicators were, respectively, 65% and 47% in Bangladesh in 2018. They doubled over the last two decades and have now reached the same level as other South Asian and lower middle-income countries. Yet they are substantially below levels observed among emerging manufacturing exporters in Southeast Asia (e.g. Cambodia or Vietnam), which were at comparable levels of financial development around 2000. The past two decades have also seen efforts to increase the quantity and the quality of banking services in Bangladesh. A broad-spectrum digitalisation, including electronic, has enabled the country to expand the coverage of its banking sector and the range of banking products not only in urban areas but also in rural areas. Yet, despite notable success, the banking sector in Bangladesh has some inherent weakness. One of its major weaknesses is the recurrent high level of non-performing loans (NPLs). The situation had become unsustainable at the end of the 1990s when NPLs reached the level of 40% of all outstanding loans. Some reforms in the regulation of the financial sector, as part of the 2003–2006 IMF stabilisation programme, were able to bring NPLs down during the 2000s. The share of NPLs in outstanding loans even reached 6% in 2011. In recent years, however, this share has started increasing again and is now above 10% – much higher than most comparable countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia, and undoubtedly damaging for the efficient functioning of the banking sector.

Even at 10%, the NPL rate is a real drain on the development capacity of the country and a powerful factor in relation to inequality. To measure its effect, the following rough calculation is instructive. It is estimated that approximately two-thirds of the NPLs can be recovered at the end of a long and costly litigation procedure. The other third must be recapitalised by the Government through drawing on fiscal resources. As NPLs are unlikely to finance the enlargement of the production capacity of the economy and are more likely to increase the wealth of defaulters, they may be considered as a sizeable net transfer – that is 3.3% of GDP – from investible resources paid by taxpayers to top income scammers.Footnote 19

A lax regulation of the banking sector plays an important role in creating and piling up NPLs, particularly in state-owned banks and other public financial institutions. Cases of loans approved due to political considerations or family connections are frequent. Loans are then often disbursed without a proper or adequate credit assessment or sanction procedure, either in terms of the viability of the project they are supposed to fund or proper valuation of collateral. When default occurs, nepotism in the sanctioning procedure in favour of politically connected people makes recovering the lost money difficult.Footnote 20

The lack of independence of the central bank, the Bangladesh Bank, and the fact that it has no control over the sizeable state-operated financial sector, are responsible for the weak regulation of the overall banking sector, that is private and state-owned. As an example of the limited regulating power of the central bank, an amendment to the Bank Company Act was recently passed that clearly facilitates the control of private banks by family or political interests.Footnote 21

Beyond increasing the frequency of NPLs, the weak regulation of the financial sector has two major consequences for the real economy. On the one hand, it allows the financial sector not to strictly obey capital adequacy requirements. This increases the probability of crises and the periodic refinancing of some banks by the state. This is especially the case for state-owned banks, where the NPL rate is the highest, as is well documented in the press.Footnote 22 On the other hand, weak control of the lending activity of banks is responsible for an inefficient allocation of investment funds. It is certainly the case that valuable projects are being financed, and the past industrial growth of Bangladesh is testimony to this, but it is also the case that weak projects are being financed, thus depriving much better projects of funding. Evidence of this is provided by the causal effect of NPLs on banks’ availability of funds, their cost, and the interest rate being charged.Footnote 23 Unfortunately, measuring the consequences of this inefficient use of those funds which have not leaked through fraudulent NPLs is extremely difficult and does not seem to have been attempted in the academic literature on Bangladesh.

Summarising, this section on the financing of the economy suggests two different views. The favourable one is that Bangladesh has been able to finance a successful industrial development in the RMG sector and is not excessively relying on foreign financing, except perhaps through the remittances of its migrant workers, which raises different issues. The less favourable one is that the exceedingly low revenue raised by the state through taxes and other means, as well as the very lax regulation of the financial sector, especially in regard to the state-owned institutions, leads to a sizeable waste of resources, and most likely to an inefficient allocation of investment.

IV Social Matters

Even though analysis of employment and the labour market would seem to belong to an analysis of output growth, it will be handled under the heading ‘social matters’ because of the deep consequences for the whole society of the pace of decent job creation in the economy, and, by contrast, the evolution of informal and often precarious employment. In particular, the state of the labour market and its evolution has direct implications for the distribution of economic welfare within the population and for the pace of poverty reduction. Human capital policies, that is education and healthcare, also affect the future level of employment and earnings, and present welfare, respectively.

A The Labour Market

The major labour market and employment challenge in Bangladesh, notably in the context of achieving the SDGs by 2030, is to provide enough jobs to the population of working age, particularly to women and youth.

A difficulty common to most emerging and developing countries is the measurement of employment and what is actually meant by a ‘job’. Without an unemployment insurance system, the notion of being unemployed is ambiguous, and in many cases irrelevant. A person without resources will always ‘do something’ to try to survive and will be recorded as ‘employed’ by enumerators. In fact, only people with some resources can afford to be truly unemployed. To a large extent, the level of employment is thus practically determined by the size of the labour force.

However, it is not the case that if most people report themselves as employed then there is no employment problem. If almost all people ‘have a job’, then Raihan (Reference Raihan2015) is right to make a distinction in Bangladesh between ‘good enough’, ‘good’, and ‘decent’ jobs, where the first category corresponds roughly to jobs in the informal sector – self-employment or wage work without a formal labour contract – and the last two categories to the formal sector. In the latter, however, a distinction must be made between ‘good’ jobs, with a labour contract and possibly some social insurance – healthcare, pensions – and ‘decent jobs’ that would fit the International Labour Organization definition. In the case of Bangladesh, that distinction is important. The Rana Plaza collapse on thousands of workers in 2013 showed that RMG jobs are not always ‘decent’ jobs, given the lack of security of workplaces. Other features defining a decent job are also often missing in the RMG sector and in other formal firms.Footnote 24

Based on that distinction, a good measure of the employment performances of a country is the creation of jobs in the formal sector, and within them the proportion of decent jobs. Based on labour force surveys over the last two decades, Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Bhattacharya and Al-Hasan2019) found that the share of informal jobs in total employment probably increased a bit between 2000 and 2006 – from 75.2% to 78.5% – and very slightly declined between 2010 and 2016: the problem being that no direct comparison is possible between 2006 and 2010 because the nature of the survey questions used to decide whether a job is formal or informal changed. According to the post-2006 surveys, the degree of informality was 87% in 2010 – indeed a big difference compared to previous estimates – and 86% in 2016. Overall, it would thus seem that: (a) the degree of informality is extremely high in Bangladesh; (b) it has varied only marginally over time. This means that formal employment grew approximately alongside the labour force, at an annual rate around 1% over the last two decades, but substantially faster since 2010, with a rate slightly above 2%. Over the recent past, Raihan and Uddin (Reference Raihan, Uddin and Raihan2018) find similar results for ‘decent’ jobs, the employment share of which increased from 10% in 2010 to 12% in 2018: that is, an annual growth rate of 3.3%. However, two or three times the rate of growth of the labour force does not make a big difference in terms of the degree of informality, given the overwhelming weight of the informal sector in total employment. It is interesting that formal or decent jobs have tended to increase at a faster pace lately, but, at that pace, it will take many years for the growth of the formal sector to make a dent in informality. This is a major challenge for Bangladesh: formal and decent job creation needs to proceed much faster.

There are bad and good signs with respect to this challenge. On the bad side, it may be stressed that between 2013 and 2016/17, and despite average annual manufacturing growth being above GDP growth, at 6.6%, the number of manufacturing jobs declined by 0.77 million, and by 0.92 million for women. This represents a 10% drop in total employment and a strong substitution of female by male jobs.

This drop in the level of employment in the manufacturing sector despite RMG exports still increasing in volume is the result of a strong automation drive that has started to displace jobs. It is a sign that the manufacturing sector might not contribute to employment growth in the future as much as it has done in the past, and that Bangladesh’s low-wage low-skill labour comparative advantage may be weakening. Even though the country may succeed in keeping, and even possibly increasing, its share of the global RMG market, the favourable social consequences of that development through the labour market will probably decline.

However, there is also a good sign in the fact that the share of the formal sector in total employment has not fallen despite an adverse evolution in manufacturing. Other formal sectors have created jobs, and presumably decent jobs, thus compensating for the loss in manufacturing. One may expect a large part of these jobs to be in the service sector, including transport and information and communication technology, and to concern workers with higher skill levels. If so, this points to the need to equip the labour force with more human capital and to invest more in education than has been done in the past.

Female employment may also be an issue. Over the past three decades, female labour force participation has increased, possibly in part as a response to the growth in RMG-based demand. Nevertheless, female labour supply has remained stagnant since 2010. Raihan and Bidisha (Reference Raihan and Bidisha2018) explored both labour supply- and demand-side factors affecting female labour force participation in Bangladesh. Their analysis suggests that custom factors like child marriage, early pregnancy, or reproductive and domestic responsibilities have not changed much with the economic progress of the country and continue to constrain female work. But the demand side also plays a role, including the stagnation, and then the recent drop, in female employment intensity. Firm-level data from the World Bank’s Enterprise Survey of 2007 and 2013 suggest that the ratio of female to male employment declined in major manufacturing and service sectors during that period, mostly due to the impact of innovation and technological upgradation.

Youth employment may also suffer from these changes. The share of youth not in education, economic activities and training (NEET) significantly increased from 25% in 2013 to 30% in 2016/17, with 87% of the youth NEET being female, possibly affected by the loss of jobs in the RMG sector.

Migrant work might be taken as a possible equilibrating mechanism of the labour market, lack of dynamism at home being compensated by more migrants. However, the driver of migration is unclear. Is it the domestic labour market pushing Bangladeshis abroad, or the labour demand pulling them towards destination countries? The recent drop in remittances, apparently linked to the slowdown in economic activity in the Gulf countries, would suggest that foreign demand matters most. Having said this, outmigration has undoubtedly had a huge impact on the domestic labour market, by reducing the supply of predominantly young, unskilled male workers, although a non-negligible share of migrants is skilled. According to World Bank statistics, some 7.7 million Bangladeshi work abroad,Footnote 25 which represents a little more than 10% of the domestic labour force.

B Poverty and Inequality

Bangladesh has made important progress in reducing poverty over the past one and half decades. According to the national estimates, the overall poverty headcount was halved between 2000 and 2016, from as high as 49% to 24%. Extreme poverty, defined by the international poverty line of 1.90 2011 international US$ per person and per day, fell still more drastically from 34% to 13% during the same period.

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) multidimensional poverty index, based not on income or consumption expenditure per capita but on various types of deprivation (nutrition, child mortality, school attendance, sanitation access to drinking water, etc.), Bangladesh has also made significant progress. The poverty headcount fell from 66% in 2004 to 47% in 2014, with particularly strong progress in child mortality, school attendance, and access to electricity, and more modest gains in access to drinking water and housing.Footnote 26 Overall, however, Bangladesh remains in the bottom third of emerging and developing countries. As this rank is somewhat below its rank in GDP per capita ranking, this suggests that Bangladesh does not do as well as other countries in the social area.

One area of concern relating to the poverty headcount is that its rate of decline seems to be slowing down. The average annual (monetary) poverty reduction has declined gradually over the past one and half decades, the same being true of the growth elasticity of poverty, which measures the capacity of economic growth to reduce poverty.Footnote 27 There are good reasons to expect such a slowdown in the reduction of poverty when poverty is already very low, as the average poor person is further and further away from the poverty line. But poverty in Bangladesh is not yet at this stage, which suggests that growth is not as inclusive today as it was in the past, and not as inclusive as it could be.

A possible explanation for the decline in the pace of poverty reduction may be the steady increase in income inequality that has been observed over time in Bangladesh. Such an increase means that better-off households benefited more, and/or worse-off households less, from economic growth. Inequality markedly increased during the 1990s. It then increased again, especially since 2010, as growth was accelerating. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, based on its Household Income and Expenditure Survey, the Gini coefficient of income rose from 0.458 in 2010 to 0.482 in 2016. The poorest 10% of the household population saw its share of the total household income fall from 2% in 2010 to 1% in 2016. By contrast, the share of the richest 10% increased from 35.8% to 38.2%.

While the preceding figures refer to household income, it is worth emphasising that a different conclusion is reached when considering the inequality of consumption expenditures per capita, as is done in the Povcalnet database maintained by the World Bank, which relies on the same household surveys as the BBS. There, no noticeable change in inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, seems to have taken place since 2000, and particularly between 2010 and 2016. A possible explanation could be that top incomes saved a higher fraction of their income in 2016 than was the case in 2010, but the reason for such a behavioural change is unclear. On the other hand, this hypothesis is consistent with the sizeable drop in the share of aggregate consumption expenditures in GDP since 2010. It is indeed little likely that low- and middle-income households, whose saving rates are very low, were responsible for such a fall in the aggregate propensity to consume.Footnote 28

The inequality issue also involves regional disparity in development. While Dhaka and a few metropolitan cities have been the major beneficiaries of development so far, many regions in the country are lagging behind. There also are genuine concerns that large discrimination prevails when it comes to budgetary allocation for social sectors and physical infrastructure, with Dhaka and a few other metropolitan cities benefitting as against many other regions in the country.Footnote 29 With two to seven times more development spending per capita in the Dhaka region in comparison with other regions, it is predicted that the country’s inequality situation will worsen in the future, despite the small improvement observed in the 2000s in the east–west gap.Footnote 30

C Education

As measured by the number of years of schooling, the level of education in Bangladesh’s population above 25 years old was 5.8 years in 2017. Among South Asian countries, this was higher than Pakistan (5.2) but lower than India (6.4), and far behind Sri Lanka (10.9) and leading Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia (10.2), Thailand (7.6), and Vietnam (8.2). In the recent past, however, Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in primary school enrolment, with near universal enrolment attained by 2010, as well as in secondary enrolment, with a rate now reaching 63%. It is thus to be expected that the average years of schooling of the Bangladeshi adult population and labour force will increase at a fast rate in the one or two decades to come.

Despite considerable progress in primary school enrolment, however, the country is seriously lagging in terms of the quality of education. Numerous studies point to low learning achievement of children who have gone through primary education. According to a recent evaluation, 59% of Grade 3 students and 90% of Grade 5 students were below the required level in mathematics at the end of the respective grades.Footnote 31 It is thus not clear that the recent increase in years of schooling will soon entail a higher productivity of the labour force. Serious efforts are now needed to improve the education system.

Regrettably, Bangladesh is among the countries in the world with the lowest ratio of public expenditure on education to GDP. This ratio has fluctuated around 2% over recent years,Footnote 32 a level that is much lower than most sub-Saharan countries, although these countries generally are poorer than Bangladesh. The contrast with the recommendation by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization that countries should target educational expenditures amounting to 6% of GDP cannot be starker.

It is important to mention that Bangladesh’s education sector also suffers from huge disparities. There is a high degree of inequality with respect to access to quality education, depending on where people live. Consequently, major spatial differences are observed in educational performances among primary schools, with schools closer to metropolitan areas performing much better than others (Raihan and Ahmed, Reference Raihan and Ahmed2016).

D Healthcare

Bangladesh has made considerable progress in basic health indicators over the last decades. Advances in life expectancy, infant mortality, and maternal mortality are noteworthy. Over the last 20 years, life expectancy has risen by eight years, to reach 72 by 2016, higher than the average for lower middle-income countries and for South Asia. Infant mortality was reduced by a factor of almost 3, being today 30 per 1,000, lower again than lower middle-income and South Asian countries. Finally, maternal mortality was brought down from more than 300 to 170 for 100,000 live births. However, to achieve the targets under SDG Goal 3 by 2030, Bangladesh still has to make significant efforts: both infant and maternal mortality must still be divided by 2.5.

There are numerous challenges for Bangladesh in achieving these targets. In particular, the public health budget is only 0.39% of GDP, which is one of the lowest in the world. For this reason, the share of out-of-pocket health expenditure in total health expenditure is much higher than in other countries, reaching 71.8%. Overall, including NGOs, it is estimated that total health expenditures amount to around 3% of GDP. In other words, the public sector covers only 13% of the cost of healthcare.

With such a low level of health expenditure compared to GDP, especially in the public sector, how has Bangladesh achieved so much in terms of the health indicators mentioned above? There is evidence that over the past few decades, Bangladesh has successfully opted for low-cost solutions to some vital health-related problems. Also, widespread activities of NGOs created a deeper awareness of health issues among the population (Sarwar, Reference Sarwar2015). A study of the use of remittances also showed that they played an important role in increasing the capacity of households to pay for health expenditure (Raihan et al., Reference Raihan, Siddiqui and Mahmood2017a).

However, in the future, such options are likely to be limited as the health system in Bangladesh is increasingly facing hard and multifaceted challenges. These result from new pressures originating from an ageing population, the rising prevalence of chronic diseases, and the growing need for more intensive use of expensive and still critical health-related equipment (like advanced scanners, MRI machines, etc.). On the other hand, financing health-related problems through out-of-pocket expenditures increases inequality, as this places a huge cost burden on poorer people and feeds the vicious disease–poverty cycle (World Health Organization and World Bank, 2019). More investment in healthcare is thus not only a desirable but also an essential policy priority. It is hard to imagine that this could be done without a substantial increase in government revenues.

E NGOs and Microcredit

Bangladesh is famous around in the world for the number and the dynamism of its NGOs. It is said they have their roots in the intense solidarity movements that developed after a deadly cyclone and the war of independence that left the country devastated and during the terrible famine that killed more than a million people during 1974–1975.Footnote 33 Thanks to them, Bangladesh has shown strong progress on several social indicators, mostly due to a multifaceted service provision regime. The expansion and multiplication of NGOs made it possible to scale up innovative anti-poverty experiments into nationwide programmes. Some notable programmes include innovations in providing access to credit to previously ‘unbanked’ poor; the development of a non-formal education system for poor children (particularly girls); and the provision of door-to-door health services through thousands of village-based community health workers. On a different level, it must also be stressed that NGOs have notably contributed to the empowerment of women within a strongly patriarchal society. The large portion of NGO beneficiaries who are poor women is evidence that a cultural change that is taking place in regard to the position of women in society.

The delivery of social services and pro-poor advocacy are not NGOs’ only activities. They have also developed commercial ventures aimed at creating a bridge between poor subsistence farmers and markets, as well as an internal revenue generation model for the NGOs themselves. Their largely self-financed pro-poor services have become an integral part of achieving national poverty reduction targets.

NGOs differ in their size and coverage. There are about 2,000 development NGOs, some of which are among the largest of such organisations in the world. NGOs such as BRAC, Grameen Bank, ASA, and PROSIKA have tens of thousands of employees and multi-million-dollar budgets, with their operations spreading throughout the nation. Other NGOs are smaller in scale and function with limited managerial and staff capacity.

Microfinance is a key factor behind the growth of NGO programmes. Some 55% of rural households have resorted to microfinance at some stage in their lives, and almost 46% hold the status of current borrowers (Raihan et al., Reference Raihan, Osmani and Baqui Khalily2017b). The sector is dominated by the Grameen Bank, BRAC, ASA, and PROSHIKA, which between them cover around 90% of microfinance operations. Even though there is some ambiguity regarding whether micro lending has a long-run transformative impact on household income,Footnote 34 it reduces current poverty and provides insurance against weather shocks or other accidents. Improvements in social indicators like female empowerment, children’s schooling, and health status in part reflect the complementary social mobilisation, training, and awareness building activities developed by NGOs alongside microcredit.

Door-to-door health services are provided by NGOs through village-based community health workers, focusing mostly on preventive care and simple curative care for women and children. NGOs have also achieved notable success in promoting behavioural change at community level by providing water and sanitation services. Their community work also includes programmes on child nutrition and tuberculosis treatment, in collaboration with the Government.

BRAC is the pioneer in launching primary education and has become the single largest NGO in the world working in primary education, social enterprises, microfinance, health services, housing, and water and sanitation programmes all over the country and also abroad. Today, BRAC provides primary education to over 1 million children in 22,000 education centres nationwide. It lends half a billion US dollars a year to 7 million people and employs more than 100,000 people for an annual budget of 750 million dollars.Footnote 35 Other NGOs are smaller but altogether they may amount to two to three times BRAC’s size. Their role is thus far from marginal. Although not quantified, their contribution to poverty reduction, in the multidimensional sense used by UNDP, has been and continues to be crucial.

V Environment and Climate Change Challenges

Bangladesh is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts because of its vast low-lying areas, large coastal population, high population density, inadequate infrastructure, and high dependence on agriculture. For Bangladesh, climate change is manifested as both changes in the severity of extreme events and in greater climate variability. Climate variability involves haphazard wet and drought years, whereas extreme weather events take the form of violent tropical cyclones which also generate powerful storm surges, and whose effects are amplified by rising sea levels. About 20% of the population lives in the low coastal zone and any increase in sea level will have disastrous effects. Because of the flat topography, even small increments in sea level rise will affect large areas, directly through inundation and salt intrusion. In the Global Climate Risk Index 2019, Bangladesh has been ranked seventh among the countries most affected by extreme weather events in the 20 years since 1998.Footnote 36

Climate change–linked problems are likely to act as a drag on the nation’s growth prospects. The Asian Development Bank (ADB, 2014) concluded that climate change poses big economic and development challenges for Bangladesh. The study pointed out that the country will face annual economic costs equivalent to about 2% of its GDP by 2050, widening to 9.4% by 2100. The reasons for these losses include an immense decline in crops, land loss and salinity, and internal migration, among other things. Climate-related disasters regularly cause migration movements and changes in poverty patterns. Because of major climate shocks, poor people from the south of the country are migrating to urban areas. Analysis at the district and sub-district levels shows that there is a strong positive correlation between the incidence of poverty and the intensity of natural hazards. On average, districts that are ranked as most exposed to natural disasters also show poverty rates that are higher than the national average. Strikingly, of the 15 most poverty-stricken districts, almost 13 of them belong to high natural hazard risk categories.

VI The Covid-19 Crisis

Bangladesh is currently the second most affected country by COVID-19 in South Asia (after India) with 1.5 million confirmed cases and 28,000 confirmed deaths between January 2020 and December 2021. However, excess mortality estimates released by The Economist Magazine suggest a much higher death toll, probably above half a million. Despite measures intended to attenuate its impact, the pandemic led to a serious economic and social crisis, and one may wonder whether the growth potential of the country has not been affected. GDP kept growing but its growth rate fell by 3–4% in 2020 and was likely still below trend in 2021. As far as poverty is concerned, on the other hand, it is estimated that at the heart of the crisis, in the spring of 2020, the headcount may have doubled, reaching maybe 40% of the population.Footnote 37 It went down, probably close to its initial level since then.

The drop in GDP growth is due to three major causes: (i) the pandemic itself, which has affected the health workers and may have forced some of them to temporarily cease working even outside lockdown periods; (ii) the lockdown episodes, especially the longest one from 23 March to 30 May 2020; and (iii) the fall in global demand. A stimulus package, consisting mostly of subsidised loans to support furlough strategies by firms, and cash/food transfers to needy households, for 3.5% of GDP, was meant to attenuate the shock.