A. Introduction: A Fundamental Shift Within the EU

The Union’s common values— fundamental rights, democracy, and rule of law—are under severe pressure. The developments in several EU Member States have consolidated to a larger illiberal turn, posing a systemic threat to the Union’s very foundations. Especially in the new Member States, a so-called rule of law backsliding can be observed.Footnote 1 Governing political parties in Poland, Hungary, and Romania started rejecting the model of a liberal democracyFootnote 2 and attacking checks and balances of the political process (e.g. independent courts, free media, or NGOs).Footnote 3 Yet, other Member States are not immune to such attacks—as evidenced, for example, by the media concentration in Italy, Greece, and Spain.Footnote 4

These developments led to a fundamental shift in the relationship between the EU and its Member States. Initially, the EU itself posed somewhat of a “threat” to fundamental rights, democracy, and the rule of law in the Member States. Although the early European Community (“EC”) presented a legal space without proper fundamental rights control of its own acts,Footnote 5 it demanded supremacy over all national law—even national fundamental rights.Footnote 6 This deficit led to the German Solange saga.Footnote 7 The Bundesverfassungsgericht, like several other constitutional courts, reserved to itself the right to review EC law for human rights violations (and eventually to suspend its application) until an EC fundamental rights protection has been established, which is “essentially comparable” to the standards set out in the German Constitution.Footnote 8 Thus, the EU had to reinvent itself in order to take human rights into account.Footnote 9 After over 40 years, the Union of today can be seen as a key actor in guaranteeing fundamental rights, democracy, and the rule of law in Europe. In parallel to this increasing protection at the EU level, an eroding constitutional protection can be observed in several Member States. In cases like Hungary, where Orbán secured a majority sufficient for constitutional amendments,Footnote 10 national constitutions seem no longer apt to shield against attacks on fundamental rights, democracy, and the rule of law.Footnote 11 These contrasting developments led to a fundamental shift in the relationship between the EU and its Member States. At least with regard to backsliding Member States, the initial Solange relationship seems to have diametrically changed: It is de facto reversed.

Figure 1: Democracy scores in Hungary and Poland after accessionFootnote 12

This reconfiguration strongly suggests that the EU should intervene in order to protect the Union’s common values in the Member States.Footnote 13 The question is, however, whether the EU has the capacity to act.

On their quest for European responses, most scholars concentrated on how to institutionally address these issues:Footnote 14 Which institution has the mandate to proceed against backsliding Member States—the European Commission, the Council, the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”), a newly founded Copenhagen Commission, the Member States bilaterally, or eventually only the Council of Europe? Which procedures should be used—Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (“TEU”), soft law instruments like the Commission’s Rule of Law Framework, or infringement procedures before the CJEU? Still, any path requiring unanimity in the Council (Article 7 TEU) or a Treaty changeFootnote 15 seems to be a political pipe dream. Since Poland and Hungary are watching each other’s backs, the Council finds itself in a deadlock situation.Footnote 16

This political petrification reminds a well-known pattern of European integration: In times when the necessary actions were not pursued in the realm of politics, the CJEU stepped in as an “engine of integration” to safeguard the core of the European integration agenda.Footnote 17 In the late 1960s, it was the Court that compensated the political stagnation with its constitutionalizing jurisprudence.Footnote 18 In the face of a growing legitimacy deficit on the Community level, it was the Court that developed fundamental rights as general principles.Footnote 19 And when facing the political inertia in constructing the internal market, it was the Court that stepped in with its doctrine of mutual recognition in Cassis de Dijon.Footnote 20 When it comes to countering the illiberal turn in several Member States, a similar inertia seems to beset the political plane, and especially the Council, as the key decision maker under the Article 7 TEU procedure. Therefore, many argued to concentrate on judicial mechanisms, to employ the infringement procedure under Article 258 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”),Footnote 21 or to interact with brave national courts via the preliminary reference procedure (Article 267 TFEU).Footnote 22 Indeed, there are good arguments in favor of relying on the CJEU. As some observed in the context of the Euro crisis, procedures before the Court have the potential to depoliticize conflicts and unfold an inclusive potential.Footnote 23 Although it is true that its involvement will place an immense burden on the Court’s legitimacyFootnote 24 and might lead to a blame game in the affected Member States,Footnote 25 it is equally true that the CJEU enjoys considerable trust from both national courts and the public.Footnote 26

So far, jurisprudential solutions seem to prove successful as the Polish example demonstrates. Many Polish courts submitted references concerning the Polish reforms curtailing the judiciary.Footnote 27 Further, the Commission decided to launch several infringement procedures.Footnote 28 After interim measures were ordered by the Court,Footnote 29 the Polish government immediately reversed some parts of its reforms.Footnote 30 This shows that governments in backsliding Member States remain responsive to the CJEU’s decisions.

This leads to the following question, which will be at the heart of this Article: What happens when a case, in which Union values are at stake, reaches the CJEU? The crucial problem is that important parts of the Polish or Hungarian reforms do not seem to be related to any EU law. So which substantive provisions can be invoked in a procedure before the CJEU? In the following, this Article will briefly expose why relying on fundamental freedoms, secondary legislation, or the Charter is not sufficient to cover threats to Union values in the Member States (B.). It will then analyze two approaches aiming at tackling the identified insufficiencies—the initial Reverse Solange and the Horizontal Solange doctrine. Although both concepts establish ways to protect the Union’s common values in situations that seem to escape the scope of EU law, they present some significant shortcomings and cannot cover illiberal developments in the Member States in all their facets (C.). Therefore, this Article argues for a more comprehensive approach: Relying on Article 2 TEU itself. Yet, this path rests on a central premise: The judicial applicability of the values enshrined in Article 2 TEU. Based on recent jurisprudential developments and the CJEU’s stance in the procedures against Poland, this Article will elaborate a framework for the operationalization of Article 2 TEU values and their judicial applicability (D.). The judgments of Associação Sindical dos Juízes Portugueses (“ASJP”),Footnote 31 Minister for Justice and Equality (“L.M.”),Footnote 32 and Commission v. Poland Footnote 33 will be at the heart of this proposal.

B. The Limited Scope of Fundamental Freedoms, Secondary Legislation, and the Charter

A first approach to addressing illiberal developments in the Member States under EU law is to rely upon provisions of the established EU acquis, which are not specifically designed or targeted at preserving fundamental rights, democracy, and the rule of law—like fundamental freedoms or secondary legislation from the internal market context. At first sight, this “get Al Capone on tax evasion strategy”Footnote 34 seems to be a clever and reliable move because it arguably depoliticizes the case and avoids the uncertainties attached to new and untested legal concepts. Yet these instruments are too limited to address the developments in backsliding Member States.

The application of fundamental freedoms usually requires a cross-border element. Therefore, many Member State areas do not come within their scope. Although cross-border requirements have lost some of their significance in the CJEU’s jurisprudence,Footnote 35 the fact remains that it will be extremely difficult (if not impossible) to always find a link to fundamental freedoms when Union values are at stake.Footnote 36 Fundamental freedoms are—except for the free movement of persons—embedded in the internal market context and its economic rationales. Although this does not exclude taking fundamental rights, democracy, or rule of law considerations into account, these considerations remain complementary. As such, it seems difficult to image how one could address for example attacks on judicial independence under these instruments.

Relying on secondary legislation is of rather limited utility as well. Experience shows that such an approach leads to superficial, eventually unsuccessful, results. The infringement procedures against the judicial reforms in Hungary (reduction of retirement ages for judges) can serve as an illustrating example.Footnote 37 The Commission based the procedures on non-compliance with Directive 2000/78 on age discrimination. Although the case was a legal success, its practical implications were limited. Instead of reinstating the judges, the government offered them compensation, a reasonable remedy in discrimination cases. It was therefore no surprise that the Hungarian government was able to avoid restoring many judges to their prior position while still complying with the CJEU’s verdict.Footnote 38

Finally, the scope of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (“CFR”) is subject to a double restriction ratione materiae: First, it does not cover threats of structural or institutional nature detached from individual rights violations. Without a doubt, human rights, democracy, and the rule of law are essentially interrelated or co-constitutive.Footnote 39 Their relationship has been incisively compared to the legs of a three-legged stool: “If one is missing the whole is not fit for purpose”.Footnote 40 Yet they are not identical, because democracy and the rule of law also include elements that affect the organization of State—for example, the separation of powers. In this sense, dangers to democracy and the rule of law are not always depictable as fundamental rights violations. This division into separate but interrelated dimensions seems to derive from the EU framework itself. Article 2 TEU differentiates between “democracy, … the rule of law and respect for human rights”. This corresponds with the findings of the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (“FRA”), which conducted an extensive study on the equivalence of Article 2 values and human rights enshrined in the Charter. According to this study, not every value has a fundamental rights counterpart. Both value-dimensions—institutional/structural and fundamental rights—are only partially overlapping. Especially democracy and the rule of law are not covered in their entirety by the Charter:

Figure 2: Comparison between Article 2 TEU values and the CFR rightsFootnote 41

Second, even if one succeeds in addressing illiberal developments in the Member States as fundamental rights issues, such an approach would have to fall within the Charter’s scope of application. Pursuant to Article 51(1) CFR, the Charter is only applicable to Member State actions “when they are implementing Union law”. In using this formula, Article 51(1) meant to cover the jurisprudential status quo before the Charter’s entry into force.Footnote 42 According to the Court’s case law, EU fundamental rights (at that time general principles) were only binding on the Member States when they were acting within the “scope of Community law”Footnote 43—meaning when a Member State implemented EU law (e.g. a directive or regulation, so-called agency-situationFootnote 44) or when it made use of the derogations or justifications permitted by EU law (derogation-situation).Footnote 45

In Åkerberg Fransson, the Court made clear that the Charter does not change the preceding case law and reiterated the formula that EU fundamental rights apply to Member State actions only in “situations … within the scope of European Union law”.Footnote 46 As Koen Lenaerts put it: “Just as an object defines the contours of its shadow, the scope of EU law determines that of the Charter.”Footnote 47 This limitation is based on a narrow understanding of the Charter’s aim and purpose with regard to the Member States. When the Charter was introduced, the Member States already had mechanisms for the protection of fundamental rights in place. Yet, diverging fundamental rights standards applying to the Member States’ implementation of EU law were perceived as a threat to its coherent and uniform application. For the Court, the Charter’s central aim vis-à-vis the Member States is therefore “to avoid a situation in which the level of protection of fundamental rights varies … in such a way as to undermine the unity, primacy and effectiveness of EU law”.Footnote 48 The Charter is just an accessory of EU law—a vehicle to secure its uniform application. In this sense, EU fundamental rights cannot go beyond what is necessary to perform this function.Footnote 49 This excludes purely internal situations, fields where the EU has potential powers which have not actually been exercisedFootnote 50 and purely hypothetical links.Footnote 51

This double limitation makes it difficult to address illiberal developments in the Member States. Since important parts of the respective reforms do not seem to be covered by Union law or are of a structural nature, the Charter is not the right tool to address these issues. So, what can be done?

C. Tackling the Identified Insufficiencies: Multiplying Solange?

A new, multiplied Solange approach could remedy this situation. The following section will outline and discuss two ideas of how Solange strategies could tackle the identified insufficiencies and protect the Union’s common values even in situations that seem to escape the scope of EU law. While Reverse Solange is a doctrinal proposal, the Horizontal Solange approach is already practiced jurisprudence.

I. The Initial Reverse Solange Doctrine

Reverse Solange goes back to Armin von Bogdandy and his team who proposed to link EU fundamental rights to EU citizenship. In Ruiz Zambrano, the CJEU held that Article 20 TFEU, the provision establishing EU citizenship, “precludes national measures which have the effect of depriving citizens of the Union of … the substance of the rights conferred by virtue of their status as citizens of the Union”,Footnote 52 irrespective of whether it is a purely internal situation.Footnote 53Accordingly, a Union citizen can challenge any Member State act before a national court on the grounds that the “substance” of its Union citizenship is violated. The Heidelberg group proposed that EU fundamental rights should form part of this substance.Footnote 54 To link human rights with citizenship and to shift from the current ratione materiae approach under Article 51(1) CFR to an approach ratione personae is not entirely new.Footnote 55 What is new is to exercise this power in form of a reverse Solange presumption. Beyond the scope of Article 51(1), Member States remain autonomous with respect to fundamental rights as long as it can be presumed that they secure the essence of EU fundamental rights protected under Article 2 TEU. Only in case of a systemic violation, this presumption is rebutted, and individuals may rely on their status as Union citizens to seek redress before national courts, which could (and should) refer the matter to the CJEU.

Obviously, this proposal was subject to criticism.Footnote 56 Since the essence of EU fundamental rights would apply even in purely internal situations, the doctrine was perceived as being incompatible with Article 51(1) CFR. Yet, one could argue that it is EU citizenship that changes the scope of application of EU law in the first place. If EU citizens can rely on the substance of their citizenship in purely internal situations, then it is not a purely internal situation anymore—it is drawn within the scope of EU law. As such, Union citizenship paves the way for the application of the Charter and EU fundamental rights remain accessory to the Treaties.Footnote 57 Further, Reverse Solange is subject to a double limitation: It operates in form of a presumption and does not rely on the full EU fundamental rights acquis, but only on its essence.Footnote 58 Therefore, Article 51(1) cannot be seen as circumvented—it still restricts the scope of the full EU fundamental rights acquis.

Despite the skillfully anticipated critique,Footnote 59 the initial Reverse Solange doctrine suffers from three major shortcomings:Footnote 60 First, its jurisprudential hook—the judgment in Ruiz Zambrano—does not reflect the current jurisprudential outlook anymore. In the early 2000s, there was a trend towards strengthening the normative status of Union citizenship culminating eventually in Ruiz Zambrano.Footnote 61 In this spirit, some commentators already anticipated a “federal turn”.Footnote 62 Since 2012, however, the jurisprudential landscape has radically changed: In an almost “reactionary phase”,Footnote 63 the Court began to construe the substance of citizens’ rightsFootnote 64 and their right to equal treatment in increasingly restrictive terms.Footnote 65 Even if the Court did not expressly shut the doors to any link between fundamental rights and citizenship in the future, it does not seem very likely that the Court will further pursue this path.Footnote 66 Thus, the Zambrano-detour—essential twist for addressing purely internal situations in the Member States under the initial Reverse Solange doctrine—does not seem a viable path any more.

Second, linking fundamental rights and citizenship simultaneously excludes third country nationals. Indeed, citizenship is an inherently exclusionary concept.Footnote 67 This leads to a gap between universal human rights and particularistic citizenship rights.Footnote 68 It is therefore not surprising that fundamental rights have been progressively decoupled from the status of citizenship in recent years and extended equally to foreigners and third country nationals.Footnote 69 This must apply in particular to Union citizenship. The whole ethos of European integration is about inclusion rather than the exclusion of the “other”.Footnote 70 To recall the warning words of Joseph Weiler: “We have made little progress if the Us becomes European [instead of German or French or British] and the Them becomes those outside the Community.”Footnote 71 As such, premising fundamental rights on citizenship could oppose the EU’s very own values.

Third, and last, the initial Reverse Solange doctrine is conceptually limited to the enforcement of EU fundamental rights. It presupposes a Union citizen vindicating his or her individual rights. Consequently, this approach does not counter threats to democracy or the rule of law in their structural or institutional dimension.Footnote 72 As such, Reverse Solange is an important but nonetheless limited tool.

II. The Horizontal Solange Doctrine

A less straightforward way to assess and enforce democracy, rule of law, and fundamental rights compliance in the Member States in situations, which seem to escape the scope of EU law, could be the use of what has been termed a Horizontal Solange approach.Footnote 73 The point of departure for this approach are mutual recognition regimes in the area of EU cooperation in civil and criminal matters. Stemming originally from the internal market context, mutual recognition regimes are EU mechanisms facilitating cooperation between (and recognition of) autonomous Member State policies without harmonization on the EU level. Examples for this mode of integration are the European Arrest Warrant (“EAW”),Footnote 74 the Common European Asylum System (“CEAS”),Footnote 75 or judicial cooperation in civil matters.Footnote 76 These mechanisms rely on one central premise: Mutual trust between the Member States—the confidence that every Member State complies with EU standards.Footnote 77

Take the EAW as an example: Generally, a Member State triggers its own human rights responsibility if it surrenders a person to a Member State where it would be subject to human rights violations.Footnote 78 Accordingly, the surrendering State has to examine the conditions in the issuing State. This is where the principle of mutual trusts intervenes. To facilitate an automatic cooperation among Member States and allow “an area without internal borders to be created and maintained”,Footnote 79 the executing State can rely upon the presumption that the issuing State complies with all EU standards. However, the principle of mutual trust does not stop there: It also entails an obligation for the executing Member States to refrain from assessing whether the issuing Member State complies with EU standards.Footnote 80 Thus, the grounds for refusing to execute an EAW were initially limited to the ones explicitly listed in the Framework Decision.Footnote 81

1. Mutual Recognition Regimes: Gateways for Rule of Law and Fundamental Rights Considerations

Yet even besides these explicit grounds, national judges can make cooperation under mutual recognition regimes subject to fundamental rights and rule of law considerations. These exceptions allow to assess the situation in the issuing Member State even concerning issues, which do not seem to be covered by EU law. That is the case in two kinds of situations.

First, judges can determine whether the conditions for a request for cooperation or recognition have been validly formed in the first place—for example, under the EAW Framework, whether the arrest warrant has been issued by a “judicial authority” in the sense of Article 6(1) of the Framework Decision. According to the CJEU in Kovalkovas, the concept of “judicial authority” is an autonomous notion of EU law, referring to an entity independent from the executive.Footnote 82 A similar reasoning applies to the mutual recognition of judgments. In Pula Parking, the Court stated that only entities that offer guarantees of independence and impartiality could be considered as “court” within the meaning of the Brussels I bis Regulation.Footnote 83 Therefore, both the EAW and EU Private International Law allow for the assessment of the issuing or rendering authority’s independence and can lead eventually to a denial of cooperation.

Second, after the EAW or the respective judgment has been validly issued or rendered, national judges can determine whether they must deny cooperation due to the risk of fundamental rights violations in the issuing Member State. Realizing the potential for conflict and inconsistencies with the European Charter of Human Rights (“ECHR”) and the Union’s own Charter—and probably pushed by national constitutional courtsFootnote 84—the CJEU began clarifying that mutual trust must not be confused with blind trust and that limitations can be made “in exceptional circumstances”.Footnote 85 For example, EAWs must be suspended or postponed if a surrender would amount to an inhumane and degrading treatment under Article 4 CFR.Footnote 86 To trigger such a postponement, a two-pronged test has to be satisfied (Aranyosi-test): First, the applicant must demonstrate systemic deficiencies amounting to a real risk of inhumane and degrading treatment.Footnote 87 Second, there must be “substantial grounds to believe that the individual concerned will be exposed to that risk”.Footnote 88 Similar developments can be observed under the Dublin SystemFootnote 89 and to a lesser extent under EU Private International Law.Footnote 90

These exceptions have far-reaching implications: They allow Member State courts and (in case of a reference) the CJEU to review internal Member State policies even concerning issues that seem to fall outside the scope of Union law.

First, Member State courts are empowered within the framework of mutual recognition regimes to review whether other Member States issuing EAWs or rendering judgements abide by essential European standards. Cooperation will be maintained as long as the other Member State generally adheres to these standards. Iris Canor termed this peer review Horizontal Solange.Footnote 91 Second, mutual recognition regimes immensely extend the CJEU’s scope of review. Generally, the CJEU cannot directly assess all relevant policies in the issuing or rendering Member States, as these are not always covered by EU law (e.g. standards in detention facilities or the organization of the judiciary). Through the gateway of mutual recognition regimes, however, the CJEU can indirectly assess whether these Member States comply with essential EU standards—even in policy areas that seem to escape the scope of EU law. In this sense, the CJEU develops an indirect competence to review the situation in issuing or rendering Member States without facing restrictions like Article 51(1) CFR.Footnote 92 That brings this construction close to the Reverse Solange doctrine—an indirect Reverse Solange.

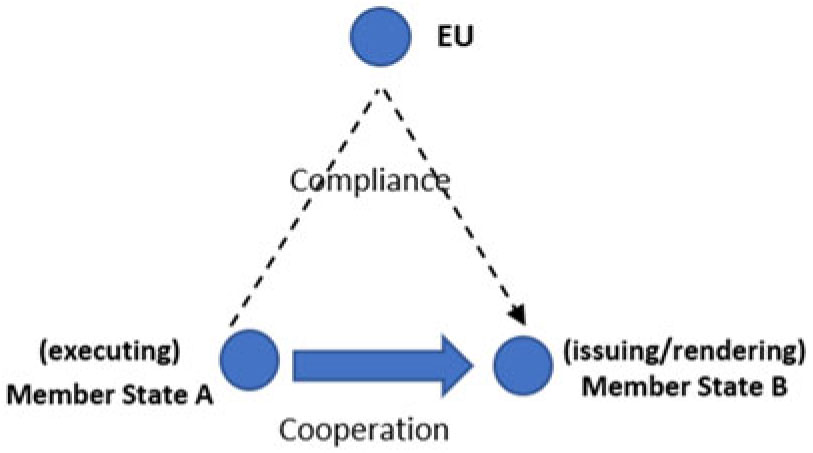

As such, mutual recognition regimes involve a horizontal (Member State-Member State) as well as a vertical axe (EU-Member State). They operate in a triangle composed of the EU and (at least) two Member States, leading to an extended review competence of both Member State courts and the CJEU. Since the EU legal order acts—both concerning the relevant standards and institutionally—as a hinge linking and regulating the relationship between the Member States, this conception could also be termed Triangular Solange.

Figure 3: Triangular Solange

Eventually, this system allows for an indirect harmonization of autonomous Member State policies. If the issuing State does not comply with essential EU standards, it is indirectly affected—in form of a reflex—via the postponement of cooperation with the executing State. It is forced to align its policies if it wants to participate in these enhanced cooperation mechanisms. This indirect pressure, however, conflicts with the rationale underlying governance through mutual recognition.Footnote 93 Compared to other modes of integration (like harmonization), mutual recognition is considered a better safeguard for the Member States’ sovereignty, diversity, and political autonomy.Footnote 94 These regimes aim at only providing a framework for cooperation without touching upon the substantive Member State policies they are supposed to coordinate. In order to respect this legislative decision against harmonization on the EU level, the CJEU has to interpret the indirectly harmonizing exceptions of cooperation in a restrictive manner.

2. Implications for Backsliding Member States: The Judgment in L.M.

How do these considerations relate to backsliding Member States? A preliminary reference of the Irish High Court from 12 March 2018Footnote 95 tried to apply the above-mentioned system to the reforms of the judiciary in Poland. The case dealt with the surrender of a Polish national, who is wanted to face trial in Poland and was arrested in Ireland based on an EAW. The High Court did not rely on the Kovalkovas-line of jurisprudence, but instead tried to apply the Aranyosi-test: Since the rule of law in Poland has been systematically damaged the respective person would be surrendered to face trial in a jurisdiction where an independent judge is not guaranteed.Footnote 96 There were, however, two potential flaws difficult to reconcile with Aranyosi: First, despite systemic rule of law deficiencies, it was not clear whether the respective person was—upon surrender to Poland—individually exposed to a risk of facing a partisan trial (second prong of the Aranyosi-test). Second, even if his return had violated his rights under Article 47 CFR, the exception in Aranyosi concerns only absolute rights,Footnote 97 which does not apply to Article 47. Aware of these obstacles, the High Court asked whether a national court can deny a request for surrender when it has found that the rule of law has been systematically breached in the issuing Member State, without performing the second step of the Aranyosi-test. Footnote 98

Generally, the CJEU had to decide L.M. in a field of considerable tension between three antagonistic claims. On one hand, there were strong calls for limiting Aranyosi to its second prong and aligning the exceptions of cooperation under mutual recognition regimes with the ECtHR’s jurisprudence in order to preserve coherence between the two systems.Footnote 99 On the other hand, the Court was urged to reduce Aranyosi to its first prong concerning structural rule of law deficiencies, to assess the situation in Poland in a centralized manner, and to generally suspend the EAW framework with regard to Poland.Footnote 100 This would have sent a strong message to backsliding Member States that the CJEU is ready to defend the Union’s common values. A possible solution would have been to establish two non-cumulative exceptions based on either systemic or individual fundamental rights considerations. Yet, the Court had to keep the exceptions of cooperation as narrow as possible to respect the legislative decision against harmonization on the EU level and to guarantee the proper functioning of mutual recognition regimes.

Eventually, the Court found some middle-ground: First, it kept both prongs of the Aranyosi-test but extended it to the essence of other fundamental rights (like Article 47 CFR).Footnote 101 Second, it rejected the possibility of generally suspending cooperation under the EAW framework and allowed only a postponing of individual EAW’s. Third, it did not assess the situation in Poland itself, but left this delicate task to the referring court, thus (presumably) opting for a decentralized case-by-case review.

3. Potential Weaknesses

The great advantage of the Horizontal (indirect Reverse or Triangular) Solange approach is that it provides the CJEU with a hook to review the internal situation in the issuing Member State. Although the surrender itself is clearly within the scope of Union law as defined by Article 51(1) CFR, this is not necessarily the case for what is scrutinized under the Aranyosi-test. In L.M., neither the Polish judicial reforms nor the specific domestic criminal proceedings show any apparent link to EU law. Therefore, the Horizontal Solange approach as applied by the CJEU in L.M. could be considered a convincing instrument to address the illiberal developments in several Member States. Nevertheless, the CJEU’s tripartite solution developed in L.M. reveals several shortcomings. Although the approach eventually allows for structural or institutional rule of law considerations and is not strictly limited to fundamental rights (3.1), the decentralized case-by-case review bears the risk of fragmentation (3.2) and might eventually even prove counter-productive (3.3).

3.1 Only Fundamental Rights?

Although the Court insisted on the second prong of the Aranyosi-test and relied on Article 47 CFR, L.M. is not a pure fundamental rights case, but a hybrid of individual fundamental rights assessment and general rule of law considerations.Footnote 102 As Advocate General Tanchev noted, there is a certain division of labor between Article 47 CFR and Article 19(1)(2) TEU, which establishes the Member States’ obligation to ensure effective judicial protection in the fields covered by Union law. While Article 19(1)(2) TEUFootnote 103 addresses a “structural infirmity” in the Member States, Article 47 CFR concentrates on “individual or particularised incidences”.Footnote 104 Yet there are two reasons why such a clear division cannot be upheld with regard to the judgment in L.M. First, the Court seems to use Article 19(1)(2) TEU to inform the content of Article 47 CFR and vice versa.Footnote 105 Although both provisions have a different function, Article 47 and Article 19(1)(2) have with regard to judicial independence a corresponding content.Footnote 106 Second, an assessment of systemic and thus structural violations is inherent in the first prong of the Aranyosi-test. As such, the CJEU can establish structural EU standards that the Member States must observe when cooperating under EU mutual recognition regimes.

3.2 The Risk of Fragmentation

To the great discontent of many commentators,Footnote 107 the CJEU neither assessed the first prong of the Aranyosi-test (systemic deficiencies) itself, nor did it suspend cooperation with Poland under the EAW framework in general. Instead, the Court seems to have opted for a decentralized case-by-case review. Indeed, a case-by-case review is demanded by the second prong of the Aranyosi-test that looks at the concrete risk of an individual fundamental rights violation. Based on the 10th recital of the Framework Decision’s preamble, the Court concludes further that a general suspension of the EAW Framework is only possible via the Article 7 TEU procedure.Footnote 108 Despite the partly legitimate criticism,Footnote 109 a general suspension would have been, in my view, a far more detrimental option. If the Court had generally suspended cooperation under the EAW framework with Poland, this would have led to a reinstitution of the pre-EAW extradition system—with national control mechanisms based on national fundamental rights. By keeping the EAW system alive with regard to Poland, the CJEU keeps this kind of inter-Member State cooperation within the scope of its review and control. This allows the CJEU to continue setting and defining relevant standards and benchmarks for the cooperation between the Member States and—in line with Horizontal Solange—to indirectly force the issuing Member State to comply with them. The Court’s self-restraint is thus a guarantee for maintaining EU law as a relevant standard.

Unfortunately, the CJEU did not assess the rule of law in Poland itself—as it did, for example, with systemic deficiencies in N.S.Footnote 110—but left this delicate task to the Member States’ courts. A decentralized control by each Member State, however, could lead to diverging or incompatible decisions throughout the EU judicial space and jeopardize the uniform application of Union law. Further, bilateral control mechanisms are generally alien to the EU legal order.Footnote 111 Therefore, at least the standards for review must be set and strictly defined in a centralized manner and in much greater detail by the CJEU.Footnote 112 A reference to the CJEU becomes even more important as it is the only way for the “accused” Member State to defend itself (via an observation). In national proceedings, a foreign Member State has practically no possibility to intervene. This ensures a certain equality of arms, which is an element of the rule of law in itself.Footnote 113

3.3 Negative Incentives

Following the L.M. judgment, national courts can now assess the rule of law compliance of Member States issuing an EAW within the frame of individual actions. Allowing Member States to postpone their cooperation with those compromising the rule of law in concrete cases seems a welcome development and should be extended to other mutual recognition regimes. Yet postponing cooperation only works if it presents an incentive for Member States to comply with EU standards. Poland’s, Hungary’s or Romania’s isolation from the Dublin system, for example, could be perceived as a courtesy.Footnote 114 Seen in this light, Horizontal Solange can only be used in selected areas of cooperation. The sole regime that could provide serious leverage is the cooperation in civil matters. Unfortunately, the public policy exceptions in these mutual recognition regimes are not developed enough to provide an instrument with bite against illiberal developments in the Member StatesFootnote 115 … yet: In this sense, much will depend on future academic work and the courts’ willingness to rely on these mechanisms in order to set a respective development in motion.

D. Towards a More Comprehensive Approach: Construing the Judicial Applicability of Article 2 TEU

Without any doubt, Reverse and Horizontal Solange constitute important and viable paths for addressing illiberal developments in the Member States before national courts and the CJEU. At their core, both Solange approaches aim at protecting the Union’s common values even in situations that seem to escape the scope of EU law. Yet, they are inherently restricted to either fundamental rights considerations or rather limited areas of cooperation (mutual recognition regimes). Without rejecting or excluding these proposals, I argue that their key aim can be better achieved by following a more comprehensive approach: Relying on Article 2 TEU itself. That provision states at a prominent position: “The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights … These values are common to the Member States … ”

Article 2 TEU presents three features qualifying it especially for countering the illiberal tendencies in EU Member States. First, it has an unrestricted scope of application. It applies to any Member State act irrespective of any link to (other) EU law.Footnote 116 Second, it is not confined to ensuring “respect for human rights”, but also captures developments threatening democracy or the rule of law in their structural, institutional dimension. Third, a justiciable Article 2 TEU could be invoked not only by Union citizens before national courts or in the context of mutual recognition regimes but in virtually any judicial proceeding before the CJEU or national courts.

The judicial applicability of Article 2 TEU, however, is far from self-evident. Considering the importance of the issues at stake, one would expect to find a thorough academic discussion and analysis of Article 2 TEU. Unfortunately, the state of scholarship concerning the famed Article 2 TEU itself is relatively low. Besides some more general contributions,Footnote 117 there are practically no works addressing the provision and its judicial applicability as such.Footnote 118

After discussing some of the uncertainties related to Article 2 TEU (I.), this contribution will demonstrate how its judicial applicability could be construed in light of the CJEU’s recent case law (II.). Certainly, the proposal will raise criticism for being methodologically unsound and—due to Article 2 TEU’s unrestricted scope of application—for uprooting the federal equilibrium between the EU and the Member States. In anticipating such objections, this Article will demonstrate that the activation of Article 2 TEU can be anchored in sound legal methodology and propose ways for limiting the judicially applicable Article 2 TEU to safeguard the federal equilibrium (III.).

I. Uncertainties Surrounding the Application of Article 2 TEU

The uncertainties surrounding Article 2 TEU can be narrowed down to three key points: Its nature (I. 1), direct effect (I. 2), and the jurisdiction of the CJEU (I. 3).

1. Nature: Do Article 2 TEU Values Have Any Legal Effect?

Scott Shapiro once wrote that “there is often no way to resolve specific disagreements about the law without first resolving disagreements about the nature of law”.Footnote 119 This holds especially true for an overarching provision like Article 2 TEU. By using the term “value”, the Treaty drafters introduced a rather ambiguous notion into EU primary law.Footnote 120 Values are widely used in very different contexts: Law, economics, philosophy, ethics, religion, sociology, psychology … values are very close to what Uwe Pörsken called “plastic words”Footnote 121—empty formulas that mean everything and nothing. As context-dependent shapeshifters or chameleons, they can be used in different fields with different meanings.

In law, values are generally juxtaposed with “principles” and “rules”,Footnote 122 and in the Treaties especially with “competences” and “objectives”.Footnote 123 Yet, values somehow transcend these dichotomies without revealing their precise character. One might justifiably ask why the drafters burdened the Treaties with such a can of worms. Unfortunately, analyzing the European Convention’s travaux is of no further use. Although several members saw the uncertainties tied to values and suggested replacing them with “principles”,Footnote 124 the term remained in the draft without being grounded in a solid theory of what they were supposed to be.Footnote 125

As such, it is not self-evident that Article 2 TEU values unfold legal effects. Some even doubt their status as law.Footnote 126 These doubts, however, are hardly convincing. The values of Article 2 TEU are laid down in the operative part of a legal text. They are applied in legally determined procedures by public institutions (Article 7 and 49(1) TEU) and their disregard leads to sanctions, which are of legal nature. In fact, the legal framing of the Union’s values seems almost inevitable. The rule of law warrants that normative requirements enforced by public institutions are laid down in the form of law. Otherwise, the mechanisms of Article 7 or Article 49 TEU would provide political morality with public authority without making it subject to any constitutional limitations.Footnote 127 For this reason, Article 2 TEU values are necessarily part of EU law.

Yet, the views on their exact nature differ considerably. First, Article 2 values can be understood as rules, because they form legal parameters relevant for both the sanctioning mechanism under Article 7 and the admission procedure under Article 49 TEU. Second, one could argue that values are in fact principles.Footnote 128 Indeed, the Treaty drafters used the notions of values and principles in a rather undifferentiated way.Footnote 129 This supports the view that Article 2 TEU is merely a continuation of the CJEU’s caselaw on general principles.Footnote 130 Finally, one could perceive Article 2 TEU as a new form of legal category, which still has to be determined. Whatever the response to this question might be, one thing seems rather clear: Article 2 TEU does not contain mere rough ideals—it unfolds legal effects.

2. Direct Effect: Are Article 2 TEU Values Directly Applicable?

Nevertheless, the acknowledgment of legal effects does not necessarily entail Article 2 TEU’s direct applicability (or even justiciability). Since the values are extremely vague and open,Footnote 131 it is not entirely clear whether Article 2 TEU fulfils the essential criteria for direct effect: A Treaty provision must be precise, clear, and unconditional.Footnote 132 With regard to the rule of law, Dimitry Kochenov and Laurent Pech put these concerns in a nutshell: “The rule of law … is not a rule of law actionable before a court.”Footnote 133

Let’s take a step back: How could Article 2 TEU be applied in the abstract? Following a broader reading, one could understand direct effect as simply implying the judicial applicability of EU law, irrespective of whether the provision creates specific legal obligations—it simply has to be taken into consideration by a court.Footnote 134 This conforms with recent trends in the CJEU’s jurisprudence. Concerning the direct effect of Charter rights, the Court started to distinguish between two categories:Footnote 135 First, mandatory effect, meaning that a provision is “sufficient in itself”to entail a specific right or obligation;Footnote 136 and second, the unconditional nature, meaning that a right does not need “to be given concrete expression by the provisions of EU or national law”.Footnote 137

According to this recent understanding, the application of Article 2 TEU faces three options. First, Article 2 TEU could be perceived as mandatory and unconditional and thus apply as a stand-alone provision.Footnote 138 Second, Article 2 TEU could lack a mandatory effect but still be unconditional. In this case, Article 2 TEU could be considered by the CJEU or national courts through some sort of (non-binding?) value-oriented interpretation of EU and national law. Finally, a third option would be that Article 2 TEU is mandatory but not unconditional. It would need to be applied with a more specific provision giving concrete expression to the values enshrined in Article 2 TEU (combined approach).Footnote 139 Such a combined approach could be construed in two ways: On one hand, Article 2 TEU could be applied directly but informed by a more specific provision. On the other hand, one could apply a specific provision of EU law giving expression to a value enshrined in Article 2 TEU thus operationalizing the latter.

3. Jurisdiction: Does the CJEU Have Competence to Review Member States’ Value Compliance?

Even if Article 2 TEU has direct effect and creates directly applicable (and thus in principle justiciable) obligations for the Member States, it is not said that the CJEU has jurisdiction to assess and enforce Article 2 TEU compliance in the Member States. Generally, the Court’s competence encompasses the interpretation and assessment of the “law” (Article 19(1)(1) TEU). This includes Union law in all its shapes, forms, and manifestations.Footnote 140 In this light, it seems very likely that the Court has a competence to interpret and assess Article 2 TEU as well. Yet it is highly debated whether the Article 7 TEU procedure and the Court’s limited competence to review the latter (Article 269 TFEU) bar an assessment and enforcement of Union values via the Article 258 or 267 TFEU proceduresFootnote 141—especially beyond the scope of application of (other) EU law.Footnote 142

Nevertheless, there are good arguments in favor of the Court’s jurisdiction. While the former Treaties have kept the EU’s foundational principles out of the Court’s reach,Footnote 143 the Lisbon Treaty does not contain any comparable limitation with regard to Article 2 TEU. First, Article 269 TFEU is an exception to the CJEU’s general competence under Article 19(1)(1) TEU, which must be interpreted narrowly.Footnote 144 Second, the political Article 7 TEU and the judicial Article 258/267 TFEU procedures have different objects and consequences. Article 7 TEU concentrates on a political situation and ultima ratio entails the suspension of Member States’ rights eventually leading to a sort of “quarantine”.Footnote 145 In contrast, the Court adjudicates an individual case and its sanctioning powers are limited to Article 260 TFEU (penalty payments). For this reason, there is no identity between the judicial and the political procedures imposing the latter’s exclusivity.

II. Reviewing and Enforcing Member States’ Value-Compliance in Judicial Proceedings

In an emerging line of jurisprudence, the CJEU could be seen as resolving these uncertainties by developing Article 2 TEU into a judicially applicable provision justiciable before the Court. The pierre fondatrice of this emerging jurisprudence is the judgment in Associação Sindical dos Juízes Portugueses (“ASJP”). In this seminal case, the Court established the Member States’ obligation to guarantee the judicial independence of de facto the whole national judiciary irrespective of any specific link to EU law (II.1.). Although this stance can also be reconstrued as a manifestation of the well-established effet utile rationale (II.2.), I propose a different reading relying on Article 2 TEU. According to my understanding, the Court opted for a combined approach, operationalizing Article 2 TEU through a specific provision of EU law. This allows to review and sanction any Member State action violating the Union’s common values in judicial proceedings before the CJEU—irrespective of whether this action reveals any link to other EU law (II.3.).

1. The Groundbreaking Judgment in ASJP

On its face, ASJP seems like a rather innocent case. A Portuguese court asked the CJEU whether salary reductions for judges adopted in the context of an EU financial assistance program violated judicial independence. As already indicated above,Footnote 146 there are two Treaty provisions guaranteeing judicial independence: Article 47 CFR and Article 19(1)(2) TEU. The former only operates under the scope defined in Article 51(1) CFR. The salary reductions were part of spending cuts conditional for financial assistance under the EU financial crisis mechanisms. Since the Court already applied the Charter in comparable situations,Footnote 147 Advocate General Øe proposed to grasp this thin material link and rely on the CFR.Footnote 148 The CJEU could have followed this approach and ASJP would have disappeared discretely as another clarification of the meandering post-Åkerberg Fransson case law. Yet, this is not what happened. The Court referred to Article 19(1)(2) TEU, which stipulates that “Member States shall provide remedies sufficient to ensure effective legal protection in the fields covered by Union law”. Such effective legal protection presupposes an independent judiciary.Footnote 149

According to the Court, this obligation applies “irrespective of whether the Member States are implementing Union law, within the meaning of Article 51(1)”.Footnote 150 This is already indicated by the different wording of both provisions. Article 19(1)(2) TEU limits its scope to “the fields covered by Union law”, whereas the Charter applies to “situations … within the scope of European Union law”.Footnote 151 “Fields” are different from “situations”. According to this semantic difference, “fields covered by Union law” could be understood in a more extensive manner.Footnote 152 But how broad should the scope of Article 19(1)(2) TEU be? The Court refers to the preliminary ruling mechanism under Article 267 TFEU: “[T]hat mechanism may be activated only by a body responsible for applying EU law which satisfies, inter alia, that criterion of independence”.Footnote 153 “Responsible for applying EU law” includes all authorities which are potentially in the situation of applying it.Footnote 154 This means practically every Member State court.Footnote 155 For Article 19(1)(2) TEU to be triggered, it is not necessary that the respective Member State court actually adjudicates a matter of EU law in the specific case at hand; the mere potentiality of dealing with such matters suffices.

As such, Article 19(1)(2) TEU reaches even situations which do not present any other link to EU law. Accordingly, ASJP has been interpreted as establishing a “quasi-federal standard”Footnote 156 for judicial independence. How does the Court justify this ample scope? A thorough analysis of ASJP reveals two (complementary?) rationales, a functional and axiological one.Footnote 157 The CJEU’s reading of Article 19(1)(2) TEU is justified both by a recourse to the functioning of the EU’s judicial system and the values enshrined in Article 2 TEU.

2. The Functioning of the EU’s Judicial System

At first sight, the CJEU seems to employ the well-established effet utile rationale. First, the Court refers to the functioning of the preliminary reference procedure in Article 267 TFEU. National courts have an indispensable position in the effective and uniform application of EU law.Footnote 158 As they are obliged to apply EU law in the respective Member States even where it may conflict with national law, they are considered to be the first “Union courts”Footnote 159 and as such an “arm of EU law”.Footnote 160 Such a system cannot work if Member State courts are not independent. Not without reason, one of the key pre-conditions for a court to be eligible for launching preliminary references is its independence.Footnote 161

Second, the rationale behind Article 19(1)(2) TEU supports the Court’s findings. Despite a limited relaxation of the demanding locus standi criteria for individual actions before the CJEU (see Article 263(4) TFEU),Footnote 162 the drafters of the Lisbon Treaty retained the decentralized judicial system based on both the CJEU and Member State courts.Footnote 163 The function of Article 19(1)(2) TEU is to ensure that this diffused judicial system works and that no protection gaps arise.Footnote 164 This necessarily enables the CJEU to specify and harmonize Member States’ provisions regarding judicial remedies and procedures.Footnote 165 These two considerations seem to strongly indicate that the CJEU is relying on its well-known effet utile argument.Footnote 166 In this light, ASJP could be read as an further step in the jurisprudential line of Les Verts, Simmenthal, Opinion 1/09 and Unibet.

3. The Judicial Applicability of Article 2 TEU

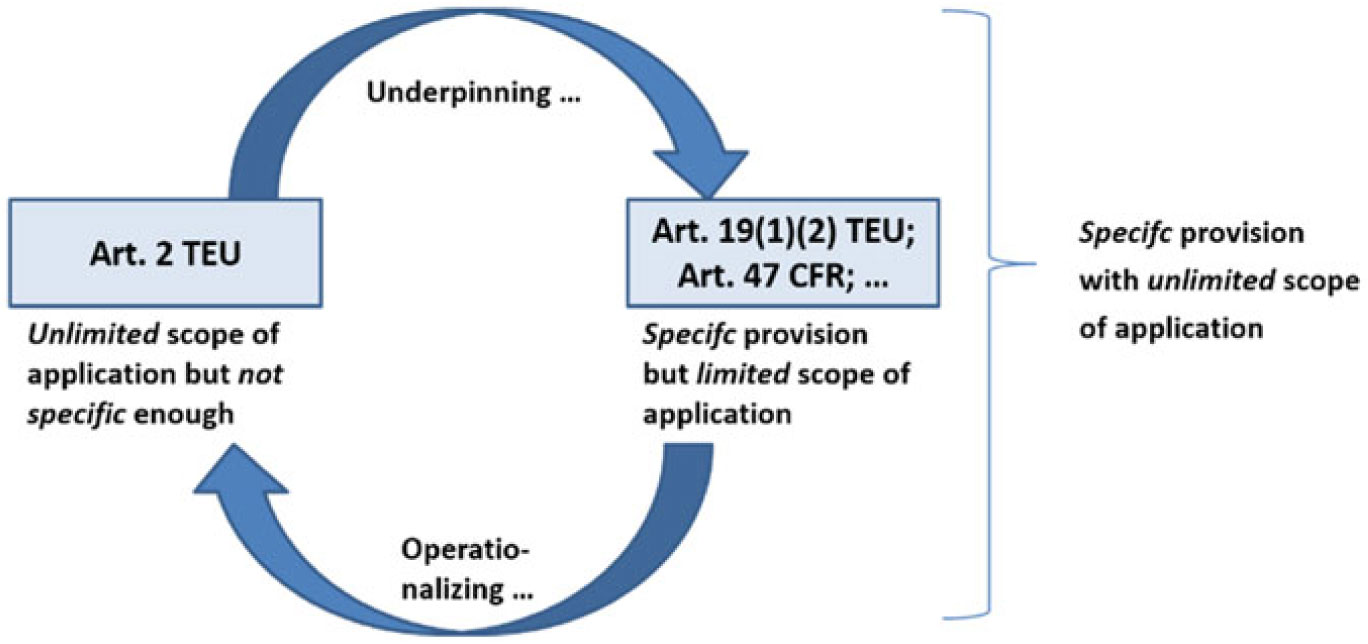

Yet there is another, potentially groundbreaking explanation for the ample scope of Article 19(1)(2) TEU leaving the beaten tracks and venturing into uncharted territories of EU law. At the crucial passage of ASJP, the Court states that “Art. 19 TEU … gives concrete expression to the value of the rule of law stated in Article 2”.Footnote 167 According to my understanding, this recourse to values lays the groundworks for the judicial applicability of Article 2 TEU. The Court implicitly rejected a self-standing application of Article 2 TEU and opted for a combined approach—it operationalizes Article 2 TEU through a specific provision of EU law (here Article 19(1)(2) TEU).Footnote 168 How does this operationalization work and what is its effect?

Like the Charter, Article 19(1)(2) TEU’s scope of application is a derived one. It only applies within the “fields covered by Union law”.Footnote 169 This, however, means that some kind of “Union law” is needed to trigger its scope. Since Article 2 TEU presumably lacks direct effect and is thus no self-standing provision either, it would probably not allow for such a triggering.Footnote 170 Taken in isolation, both provisions are therefore not applicable: Article 19 because of its derived scope and Article 2 TEU because of its lacking direct effect. What could be a way out of this impasse?

At first glance, Article 19(1)(2) TEU would have to be triggered by other Union law (e.g. a directive or fundamental freedoms). In consequence, Article 2 TEU operationalized by Article 19(1)(2) TEU would depend on the scope of the triggering EU law and could not operate beyond that.Footnote 171 Such a limitation, however, seems to severely neglect Article 2 TEU’s foundational character and its unrestricted scope of application: The Member States are bound by it even in areas not covered by any (other) Union law.Footnote 172 Limiting Article 2 TEU to the scope of other Union law would frustrate its overarching importance and deprive the recourse to Union values of any added-value.

And indeed, the CJEU does not seem to have limited the scope of Article 19(1)(2) TEU (operationalizing Article 2 TEU) to the scope of any other Union law applying. It established standards for practically any Member State court. How does the Court reach this conclusion?

According to my understanding, the combined reading of Article 2 TEU with a specific provision leads to a cumulation of their legal effects—a mutual amplification: While the specific provision of EU law (here Article 19 TEU) translates Article 2 TEU into a specific legal obligation, the operationalized Article 2 TEU triggers and determines the scope of application of the specific provision.Footnote 173 In this interplay, each contributes what the other lacks—specificity and scope. As it is Article 2 TEU, which determines the scope, the operationalized obligations can apply beyond the scope of any other Union law to any Member State action. In this sense, the idea of mutual amplification kills two birds with one stone: It allows for the judicial applicability of Article 2 TEU through a specific provision without losing its unrestricted scope.

Figure 4: Mutual Amplification

Eventually, this approach could be extended to any norm of EU law containing a specific obligation and giving expression to a value enshrined in Article 2 TEU. As already mentioned, Article 2 TEU contains the values of “respect for human rights,” democracy, and the rule of law. Since the Charter can be understood as a specific realization of these values,Footnote 174 a mutual amplification of Article 2 TEU and Charter rights seems possible.

The Court’s judgment in L.M. could be a first, careful step in this direction. As seen above, the CJEU assessed the conformity of a situation beyond the scope of Union law with the essence of a Charter right.Footnote 175 Although the issue of an EAW is clearly within the scope of Union law as defined by Article 51(1) CFR, this is not the case for what is scrutinized under the Aranyosi-test. In L.M., neither the Polish judicial reforms nor the specific domestic criminal proceedings presented any apparent link to EU law—except for Article 2 TEU. One could of course argue that this review competence is a result of the specificities of mutual recognition regimes.Footnote 176 Yet, similar to ASJP, the Court establishes a nexus between the essence of Article 47 CFR and Article 2 TEU:

Judicial independence forms part of the essence of the fundamental right to a fair trial … which is of cardinal importance as a guarantee … that the values common to the Member States set out in Article 2 TEU, in particular the value of the rule of law, will be safeguarded.Footnote 177

In the same vein, the Court started to increasingly connect Article 2 TEU and Charter rights. In Tele2 Sverige, for example, the Court established a continuum between the freedom of expression under Article 11 CFR and the value of democracy under Article 2 TEU.Footnote 178 In light of these links, one could argue that the concept of mutual amplification is not limited to the situation in ASJP, but instead open to all provisions of EU law giving concrete expression to Article 2 TEU values.

III. Anticipating Objections and Advancing Rejoinders

In sum, the Court’s stance in ASJP could be interpreted as making the values in Article 2 TEU judicially applicable through a mutual amplification with a specific provisions of EU law. The decisions following ASJP reveal a twofold development. First, the Court is willing to scrutinize and sanction Member State actions under the operationalized Article 2 TEU. Although the CJEU refrained from finding any violation in ASJP, the judgment served as a stepping stone for the infringement proceedings against Poland.Footnote 179 Second, the CJEU seems to develop the diffused and decentralized EU judicial network into a value monitoring and enforcement mechanism. Today, violations of operationalized Union values can reach the CJEU not only via infringement proceedings initiated by the Commission (constellation in Commission v. Poland) but also through preliminary reference procedures—either by “brave” national courts directly against national measures (constellation in ASJP) or by courts in other Member States assessing cooperation with backsliding Member States under mutual recognition regimes (constellation in L.M.).

Without a doubt, the proposed reading of ASJP and its progenies leads to a considerable development of the law. It seems to immensely extend the scope of Union law and the Court’s jurisdiction. Indeed, no area of the Member States seems to escape the obligations stemming from Article 2 TEU. As such, Article 2 TEU could become the core of a European Constitution threatening the federal equilibrium established by the Treaties. Therefore, any proposal of placing an activated Article 2 TEU in the hands of the CJEU will most certainly raise doubts and criticism. The following section aims at anticipating some of this critique by referring to one of Luxembourg’s most accomplished national counterparts—the Bundesverfassungsgericht (“BVerfG”).

1. Framing Possible Objections

Generally, it seems uncontested that EU primary law is characterized by a special, evolutive dynamicFootnote 180 and has to be interpreted accordingly.Footnote 181 Due to the partial incompleteness of the EU legal order, the creative judicial development of the lawFootnote 182 has been an accepted feature of the CJEU’s legal reasoning since the very beginning.Footnote 183 This must apply especially in situations of new and unprecedented challenges that threaten the EU’s very foundations.

There are, however, two key limits to such a judicial development of the law, which the BVerfG sketched out in Honeywell:Footnote 184 Horizontally, the Court should respect the inter-institutional separation of powers. Accordingly, “[t]he Court of Justice is … not precluded from refining the law by means of methodically bound case-law” respecting its judicial function.Footnote 185 “[A]s long as the Court of Justice applies recognised methodological principles”, the judicial development of the law by the CJEU has to be accepted.Footnote 186 Vertically, a “major limit on further development of the law by judges at Union level is the principle of conferral”.Footnote 187 Under this premise, it is essential to anchor the proposed reading of ASJP and the idea of mutual amplification carefully in the Court’s case law and established methods of legal reasoning (III.2.). At the same time, its impact must be strictly limited in order to safeguard the Union’s federal equilibrium (III.3.).

2. A Methodologically Unsound Concept?

Despite evident difficulties in agreeing on a common European legal methodology,Footnote 188 the CJEU’s interpretation generally revolves around “the spirit, the general scheme and the wording of the Treaty”Footnote 189 and concentrates especially on a mixture of systematic and teleological considerations.Footnote 190 On one hand, the Court can consider the telos of a respective provision itself. On the other hand, it can refer to a telos detached from said provision by referring to objectives or principles of the EU legal order. This second type could be described as systematic or meta-teleological interpretation.Footnote 191 In this light, there is a twofold, interlocking methodological justification for the idea of mutual amplification between Article 2 TEU and a specific provision of EU law.

First, the Court can rely on a teleological, concretizing, or gap-filling interpretation of Article 2 TEU itself—a practice accepted by the BVerfG as a methodologically sound, judicial endeavor.Footnote 192 Specifying the obligations enshrined in Article 2 TEU by relying on existing provisions of the acquis not only provides such specificity, but is also much more restrained than filling the gap solely based on case law and praetorian principles.Footnote 193 In doing so, a parallel could be drawn to the Court’s case law on Union objectives. Although these objectives do not have any direct effect,Footnote 194 the Court found ways to make them judicially applicable. It stated that the Union’s objectives “are necessarily applied in combination with the respective chapters of the EC Treaty intended to give effect to those principles and objectives”.Footnote 195

Second, the Court can employ a systematic or meta-teleological interpretation of the specific provision operationalizing Article 2 TEU (e.g. Article 19(1)(2) TEU, Charter rights or any other provision giving specific expression to Article 2 TEU). Under this method, the specific provision would be interpreted in light of the Union’s founding values as enshrined in Article 2 TEU. In case of provisions, which have no derived but nonetheless a limited scope of application (e.g. cross-border requirements), this could lead to a careful teleological reduction of their restricted scope as far as Article 2 TEU values are at stake.Footnote 196 Although there are arguably no hierarchies in EU primary law,Footnote 197 some provisions—like objectives—seem to have been treated as primus inter pares and served as guiding stars for its interpretation.Footnote 198 After Lisbon, objectives seem to take a back seat behind the Union’s common values. As some commentators noted, Article 2 TEU “symbolizes a paradigm shift from a legal entity that, in the first place, exists to strive for certain goals to one which, above all, expounds what it stands for.”Footnote 199 This shift should find its expression in the Court’s legal methodology. Hence, it does not seem far-fetched to propose a new kind of meta-teleological interpretation—not in light of the Union’s objectives, but in light of its common values: An axiological interpretation.Footnote 200

Eventually, the idea of a mutual amplification—two mutually complementing and reinforcing provisions—is not unprecedented in the Court’s case law. In a rather recent line of cases, the Court had to decide on the interplay of rights stemming from directives and Charter rights in horizontal situations between private parties. These cases concerned the question of whether a national provision in a case between two individuals conformed with EU law—first with rights stemming from specific directives and second with EU fundamental rights. Directives do not apply horizontally.Footnote 201 The fundamental rights at issue apply horizontallyFootnote 202—yet they are accessory to the scope of Union law (Art. 51(1) CFR) and apply only in case their scope is triggered by the directive.Footnote 203 Thus, taken in isolation, neither of them is applicable. The Court, however, relied on a creative solution based on the notorious Mangold judgment.Footnote 204 Taken together, both the directive as well as the fundamental right contribute to what the other lacks: Scope and horizontal effect. The directive, although not directly applicable, has “the effect of bringing within the scope of European Union law the national legislation at issue”.Footnote 205 Once the scope is triggered, it is the Charter right that applies horizontally in the case at hand. To add another layer to this complex interplay, the Court applies the Charter right (or the general principle) in a manner that is exactly equivalent to the right enshrined in the directive. This becomes most apparent in Kücükdeveci, where the Court stated that Directive 2000/78 “gives specific expression” to the general principle of non-discrimination.Footnote 206 The Court de facto applied the Directive as the principle’s (or right’s) specific expression.Footnote 207 As such, this reasoning is a perfect example for the cumulation of legal effects sketched out above: The general principle allows for the horizontal application, while the Directive triggers the scope of Union law and provides for specificity.

3. Pretext for a Power Grab?

Naturally, the bold reading of the Court’s case law as proposed above has the potential of severely upsetting the Union’s federal equilibrium epitomized by Articles 4(2) or 5(1) TEU or Article 51(1) CFR.Footnote 208 Therefore, it is essential to put safeguards in place ensuring that Article 2 TEU does not become the “pretext for a power grab”.Footnote 209 These essential safeguards, however, should not be applied in a way that frustrates the respect for Article 2 TEU values either. Both considerations have to be carefully balanced against each other. In my view, the outcome of this balancing exercise could be a threefold limitation ensuring Article 2 TEU’s function and simultaneously providing a safety net for the federal bargain.

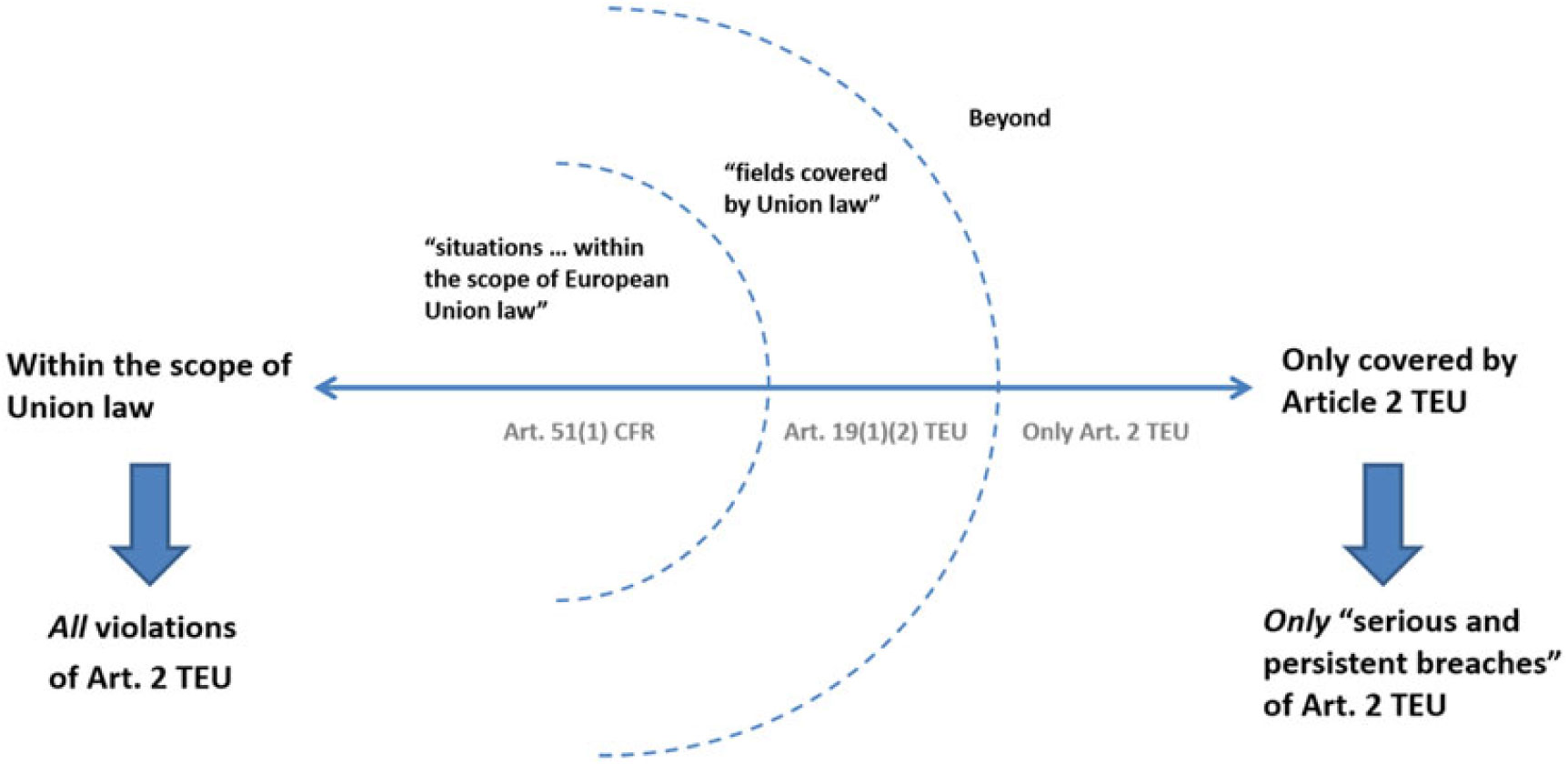

3.1 Limiting the Obligations Enshrined in Article 2 TEU

First, Article 2 TEU must be interpreted in a restrictive manner as being triggered only in exceptional situations. On the one hand, Article 2 TEU cannot impose high standards upon the Member States, since such an interpretation could not be squared with the legally guaranteed constitutional autonomy of the Member States.Footnote 210 Concerning the value of “respect for human rights”, some have proposed operating with the concept of “essence”.Footnote 211 As far as the essence of Charter rights is concerned, they are also protected as values under Article 2 TEU, while Article 51(1) CFR continues to delimit the application of the full fundamental right acquis. On the other hand, Article 2 TEU can hardly force detailed obligations upon the Member States, because this would ignore the actually existing constitutional pluralism in the Union. Due to the practically countless possibilities of how to bring the abstract values to life, Article 2 TEU cannot—from a mere practical perspective—be understood as containing very detailed obligations.Footnote 212 Accordingly, Article 2 TEU’s high degree of abstraction necessarily correlates with a lower degree of review by the Court. Where does that leave us? One feasible solution could be to understand Article 2 TEU as establishing only a regime of “red lines”.Footnote 213 On a conceptual level, Article 2 TEU would determine negatively what is not allowed, without positively determining how things should be instead. In a nutshell, the Court should apply Article 2 TEU only in exceptional situations and only in the form of “red lines”.

3.2 Limiting the EU’s Competence

Second, I argue that the Union’s “Verbandskompetenz” (its competence as a legal order) to enforce Member State’s Article 2 TEU compliance beyond the scope of (any other) Union law is limited to the substantive thresholds of Article 7 TEU. Indeed, the only provision explicitly empowering the EU legal order to enforce EU values or sanction violations thereof beyond the scope of (any other) Union law is Article 7 TEU. Hence, this provision contains a strong indication that the EU’s Verbandskompetenz is limited at least to the substantive thresholds triggering Article 7 TEU (a “serious and persistent breach”).Footnote 214 This could provide the starting point for a workable restriction operating in form of a sliding scale: The more or the clearer a situation falls within the scope of other EU law, the more the EU and the less the respective Member State is affected. This means that in case of a clear link to EU law, every violation of Article 2 TEU values can be sanctioned by EU institutions (e.g. under the Charter). If the link is weaker or nonexistent, it approaches the confines of Article 7 TEU. To assess and sanction every violation in such situations would exceed the EU’s Verbandskompetenz. Therefore, the more the situation departs from the scope of Union law and comes solely under Article 2 TEU, the more a violation must reach the substantive thresholds of Article 7, and the more it must constitute a “serious and persistent” breach in order to be invoked before the CJEU. This sliding scale could be visualized as follows:

Figure 5: Sliding scale

3.3 Limiting the CJEU’s Competence

Finally, as proposed by the Reverse Solange doctrine, the Court’s “Organkompetenz” to review Article 2 TEU value compliance in the Member States could be subject to a presumption of conformity accompanied by a high threshold for its rebuttal. Such a threshold could be fixed on the level of systemic deficiencies—a notion which is well-established throughout the European legal space.Footnote 215 Therefore, simple and isolated infringements upon the values enshrined in Article 2 TEU will not suffice to rebut the proposed presumption. The justification for such a presumption could be derived from the principle of mutual trust. Although mutual trust has initially only been invoked horizontally between the Member States,Footnote 216 it is not excluded in the vertical relationship of EU and Member States. Mutual trust is based on or at least intrinsically linked to the principle of loyal and sincere cooperation in Article 4(3) TEU.Footnote 217 This can also be derived from the Court’s case law.Footnote 218 The principle of mutual loyalty, however, expressly extends to Union institutions and hence the CJEU as well.Footnote 219 A similar trend could be predicted for the principle of mutual trust.

E. Conclusion

In entering the European Union and opening their respective legal orders for direct effect and primacy, the Member States simultaneously accepted an openness towards internal developments and decisions taken by other Member States. The EU does not only extend the transnational reach of each Member State, but also creates a situation of mutual vulnerability.Footnote 220 Internal developments in one Member State can lead to spill-over effects in all other Member States. The complex network of cooperation created by the European Union is not only enabling, it is transmitting and intensifying these effects. Especially through the introduction of majority decisions in the Council, each Member State partially and indirectly governs all others. As such, the EU is underpinned by an “all-affected principle”.Footnote 221

As Commissioner Jourova put it: “the EU is like a chain of Christmas lights. When one light goes off, others don’t light up and the chain is dark.”Footnote 222 This holds particularly true for the EU judicial space. In the words of Koen Lenaerts,

It is the … effect of supranational and transnational justice that creates a ‘chain of justice’ in Europe where national courts are to engage in a dialogue with the ECJ as well as with each other. Thus, where a national court ceases to be independent, a shackle of that chain is broken and justice in Europe as a whole is inevitably weakened.Footnote 223

Therefore, it is of utmost importance to secure Member States’ adherence to the Union’s common values as an underlying basis and essential safety net on which cooperation can take place.

The last two years have shown that the Court seems more than willing to protect this common value basis against illiberal developments in the Member States. The judgment in ASJP especially represents a veritable stepping stone towards a strong “union of values” —a judgment on par with van Gend en Loos, Costa/ENEL, or Les Verts.Footnote 224 Its groundbreaking potential cannot be overemphasized. With ASJP, the Court achieved to breathe life into the Union’s common values—it paved the way for their judicial application in the EU value crisis. In sum, the Court’s stance in ASJP could be understood as making Article 2 TEU judicially applicable by operationalizing it through specific provisions of EU law without, however, losing its unrestricted scope. Due to this mutual amplification, any Member State act can be scrutinized under the operationalized Article 2 TEU—albeit under very restrictive conditions and only in very exceptional circumstances. As such, Article 2 TEU has become the Archimedean point for judicial proceedings against backsliding Member States.

Eventually, however, judicial proceedings are only one part of the solution. As the late Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde concluded in his famous dictum, any legal order draws eventually on preconditions it cannot itself guarantee.Footnote 225 This applies especially to the blossoming European union of values. Commissioner Jourova put it in a nutshell: “We will have to decide … what … really holds us together. I am among those who believe that values are … that glue.”Footnote 226