It is hard to get to Killingworth by accident. Slotted between the two principal motorways leading out of Newcastle, the town is most directly approached through a maze of county roads punctuated by roundabouts. Motorists arriving via Southgate road pass a series of empty gray office buildings set on flat, sparsely treed moorlands, which abruptly give way to an expanse of water on either side as the road becomes a narrow causeway. Low brick houses appear off to the left, balanced by a bland office park on the right. Another roundabout: to the left and right snake West Bailey and East Bailey, looping roads that girdle the town center, while due north is a squat, nondescript specimen of suburban shopping mall architecture—the Killingworth Centre, its brick-and-plaster bulk set in an asphalt lake of parking lots. Southgate continues through the roundabout only to dead-end into the rear of the mall, at which point drivers are forced to execute an awkward three-point turn and head back to the roundabout.

A visitor returning to the town after a thirty-year absence would be baffled; not much remains of the original town. Gone is the hulking central “citadel” that once straddled the town's main north-south axis. Gone too are the soaring concrete towers linked by elevated walkways that Pevsner's Buildings of England guide described as resembling “nothing so much as a set from Fritz Lang's Metropolis.”Footnote 1 A 1970 Guardian report enthused that Killingworth “catches the imagination” and “exudes an overwhelming sense of place which is unique among new urban developments in the North-east,” while a New Statesman article from 1975 gushed that the town “comes as a sudden-future shock.”Footnote 2 Imagination and a sense of place are the antithesis of twenty-first-century Killingworth. Yet in the void between Southgate's abrupt terminus and the beginning of Northgate just north of the mall hover the ghosts of a “space age” city designed to reverse what its designer saw as the centrifugal trajectory of contemporary British social life. A “modern castle town” conceived as an experiment in social engineering as much as in innovative architecture, Killingworth is a largely forgotten piece of the history of postwar British planning and design, its central core razed and rebuilt less than two decades after its creation.

The best way to get to Killingworth might be by way of Uganda. Roy Gazzard, the town's chief architect and designer, thought so. Citing his experience as a “social engineer” in Uganda during the 1950s, Gazzard argued that new towns could provide a lesson for Britain as it entered the 1970s. Killingworth was “making the first tentative steps in social engineering,” claimed Gazzard, and its example would serve as a test case for designing cohesive communities in an increasingly multicultural nation: “What better laboratory for an experiment in racial integration could there be than the nascent community of a new town?”Footnote 3 It was a bizarre statement, since Killingworth's population was to comprise chiefly white working-class residents “decanted” from Newcastle's overcrowded peripheries in slum clearance campaigns. But Gazzard was quite serious in his claims, and used his connections in Kampala to recruit Ugandan planners for his design and development team at Killingworth.Footnote 4 Its “castle” design notwithstanding, international visitors from Tunisia and Japan likened Killingworth to their home countries’ built environment, and locals informally dubbed one housing area “Gazzard's wog village.”Footnote 5 This stridently local new town, with its overt references to medieval Northumbria, was crosshatched with colonial and global flows of people and ideas.

How those flows shaped Gazzard's design for Killingworth is the subject of this article. Drawing on Gazzard's written plans, professional talks, letters, and interviews, I show how Gazzard's colonial experience furnished him with planning principles that would guide his work in Britain during the 1960s. These principles took two main forms. The first of these was Gazzard's conception of the architect-planner's role as that of a social engineer whose mandate was to shepherd psychologically vulnerable urban populations through the traumas that attended social and economic change. He formulated this philosophy in response to anxieties over the management of urban growth in late colonial Uganda, but he later would contend that the same principle held true as a guide to planning communities in the deindustrializing north of England. The second strand of influence was subtler. Working in the colonial context instilled in Gazzard a mystical conception of the local: only designs attuned to the history, culture, people, and landscape in which they were set could create a lasting and humane urban community. Just as the contraction of Britain's empire sparked a turn toward exploring the national and the local among modernist writers, Gazzard's urban modernism increasingly embraced the specific cultural contours that bounded each place.Footnote 6 The blend of the modern and the medieval at Killingworth is best understood as part of this process of imperial crisis and contraction.

Killingworth fits awkwardly in the historiography of Britain's new-town movement, which was an unprecedented campaign to design and build self-contained towns on greenfield sites around the country.Footnote 7 Stretching from the mid-1940s to the end of the 1970s, the official New Town program's lifespan paralleled that of the British welfare state and is usually narrated according to similar themes—optimism in social progress, a naïve faith in the power of state planning, and mounting disenchantment. The story unfolds in a particularly British register: rooted in the Garden City movement in the late Victorian period, it played out as a domestic battle between visionary planners and small-minded politicians and landowners; the island story is only interrupted with an occasional detour to the United States or Europe.Footnote 8 Missing from this narrative is the formative role that international and colonial experiences had on the designers of individual new towns.Footnote 9 In a broader sense, what part did former colonial urbanists have in crafting the space of multicultural Britain?

Gazzard's work in Uganda played out in the context of Britain's “second colonial occupation” in Africa—the period between the Second World War and decolonization in the 1960s when indirect rule, a form of governance that relied heavily on the authority of local chiefs, gave way both to heightened intervention and investment by the colonial state in local intermediaries. Central to this project was the management of Africa's expanding urban populations by an array of experts—anthropologists, sociologists, engineers, and planners—in order to smoothly integrate the empire's African subjects into the political and economic structures of the colonial state.Footnote 10 The newly credentialed architect-planner Roy Gazzard was one of these experts, and his colonial experience was the crucible for his design philosophy. Gazzard's long career highlights the complicated colonial and postcolonial relays that shaped the development of one British new town. Killingworth is idiosyncratic; architectural critic Owen Hatherly describes it as “a deeply strange place.”Footnote 11 It is that, but its example nonetheless challenges insular British narratives of the new-town movement. In Gazzard's case, Killingworth was but one node of a career that spanned three continents over the course of four decades. Placing Gazzard and Killingworth in their international context reveals the overlapping and interpenetrating influences that shaped colonial and metropolitan planning at the tail end of the British Empire. Gazzard's intellectual biography also provides insight into how “universal” planning concepts like community, place, and space took on different inflections as they passed from the metropole to the colony and back again.Footnote 12

Because Gazzard's papers make few explicit comparisons between his work in Uganda and his later designs at Killingworth, identifying the colonial influence on his career demands close attention to the evolution of his design philosophy. Gazzard's work in Uganda made runnels that guided his later approach to planning. So too, however, did his professional contacts, his observations of contemporary town design, his reading in postwar planning theory, and his Christian beliefs. All of these lines of influence were simultaneously shaping his approach to Killingworth. But the colonial runnel proved especially powerful in the context of the new town. The lessons Gazzard learned while guiding development in late-colonial Uganda weighed heavily on his work as the self-titled “director of development” at Killingworth. Building new settlements for “detribalizing” Africans provided Gazzard with a conceptual and architectural vocabulary for shaping working-class communities in the deindustrializing north of England. The role of the “social engineer” in both contexts, he contended, was to find symbolic spatial forms that would suture the social, psychic, and spiritual wounds exposed by the erosion of “traditional” authority—be it the “tribe,” the factory, or the coal pit.Footnote 13 This discussion will be far more concerned with the planner's vision of Killingworth than with the lived reality of the built town. As Guy Ortolano has demonstrated, plans—even abortive or unrealized ones—are a useful lens for recovering and analyzing the “assumptions and ambitions” of a historical moment.Footnote 14

Analyzing Gazzard's extensive writings on the planning philosophy behind Killingworth complicates the opposition between “tradition” and “modernism” in British urban design.Footnote 15 John R. Gold describes a broad planning consensus in the early postwar period that linked modernism in architecture and urban design to social and political progress.Footnote 16 Writing of urban planning in the 1960s, Simon Gunn contends that it was based on a “meliorist belief that planning by experts could engineer into place a bright new world of convenience, efficiency, and plenty.”Footnote 17 The early 1960s were by all accounts the high point of this optimism in the power of rational planning and new technology, and nowhere was it more apparent than in the new towns of that decade. As Mark Clapson writes, the plans for 1960s new towns “reflected something of the zeitgeist of that decade, namely the love of the new, and the ostensible abandonment of old-fashioned ways of doing things, both of which fused with a renewed impulse to modernize the built environment, and a desire to embrace the expanding range of choice and freedoms that accompanied increasing affluence and consumption.”Footnote 18 These recent historical evaluations underline modernist planning's futurist, technophiliac bent.

Where scholars have emphasized the historically sensitive, conservationist strands of modern planning, such deviations are usually portrayed as concessions made in spite of the modernist project.Footnote 19 Yet Gazzard's plans for Killingworth exhibit a Janus-faced modernism in which the unabashedly futuristic building designs were marbled with a romantic vision of the mythic power of historical forms to provide social meaning and psychological security for the individual subject. Here, the yen for the new was intertwined with an urge to preserve local historical sites—or, where they were missing, to create them. This impulse went beyond a simple concern for conserving “heritage.”Footnote 20

Killingworth's design would have a religious as well as a psychological impact. Modern planners, Gazzard maintained, had “measured everything—except the spiritual quality of the new-town environment.”Footnote 21 Under Gazzard's leadership, the Killingworth Development Group met for weekly prayer meetings attended by “all the social engineers.”Footnote 22 A devout Anglican, Gazzard sought to integrate an ecumenical Christian ethos into the fibers of the new town—a spiritual counter to the “purely physical” and “materialistic” approach of the welfare state. This integration would take architectural form in the “Citadel”—a gargantuan multilevel building that combined commercial and administrative spaces with health clinics and an ecumenical worship center. Killingworth, as Gazzard was fond of repeating, would cater to the “whole man health,” an approach that encompassed hearts, souls, and minds as opposed to the welfare state's lopsided emphasis on physical well-being.Footnote 23

Colonial Prelude: Social Engineering in Jinja, Uganda

Roy Gazzard's earliest childhood memories included charting the architecture of London's sewers with his maternal grandfather, a sanitation engineer. Born in 1923 into a family of engineers and ink makers, Gazzard received a diploma in architecture on the eve of World War II and then served in the war, first as an engineer and later as a glider pilot. When the fighting stopped, he found a position with military intelligence in the British occupation of Jerusalem, where he narrowly escaped the bombing of the King David Hotel by militant Zionists after an anonymous phone call warned him not to take his usual morning coffee there.Footnote 24 In Jerusalem, he became acquainted with Henry Kendall, the architect in charge of urban planning in Jerusalem. Gazzard returned to England after demobilization and enrolled at the Architectural Association in London for his professional training, studying under the modernist German-Jewish émigré Arthur Korn.Footnote 25 Meanwhile, Kendall was appointed chief planner for Uganda and arranged for Gazzard to serve as his assistant. Gazzard arrived in Uganda in 1949 and took charge of planning the region east of the Nile, a region that encompassed the rapidly expanding urban centers of Mbale, Tororo, and Jinja, Uganda's second largest city and Gazzard's home for the next four years.Footnote 26

Twenty-six years old when he arrived in Jinja, Gazzard immersed himself in the town's social and cultural life. Unsurprisingly, his role as a British-born administrator launched him into the elite sphere of expatriate society, and his calendar was punctuated by banquets and tea parties as well as work with academics at the East African Institute of Social Research in Kampala.Footnote 27 Yet he also forged broader social ties in the community. He was deeply involved with the local churches (his twin daughters were baptized in Jinja), served on the governing board of missionary-run Busoga College at Mwiri, lent money to several of his African subordinates, and was godfather of an African girl.Footnote 28 These informal contacts would tether him to Uganda long after his colonial service had ended.

Jinja played a particularly formative role in Gazzard's development as a “social engineer.” His chief task was to formulate a plan for the city, which was in the midst of a period of infrastructural expansion and population growth. Between 1948 and 1951, Jinja's population more than doubled; what had been a tidy settlement of 8,400 ballooned to 20,800.Footnote 29 The Nile bisected Jinja as it flowed north out of Lake Victoria, separating the mainly African neighborhoods to the west from the city's administrative and commercial core clustered on the eastern bank. This latter area comprised an ethnically diverse population, with African and European settlements abutting a primarily Asian town center.Footnote 30

The peri-urban settlements of African workers on Jinja's western fringe were particularly concerning for colonial authorities. Describing rudimentary infrastructure and a dearth of sanitation, one report lamented that the “dense fringe of huts” girdling the core was “a menace to the health of the town.”Footnote 31 Added to these concerns with the physical environment was another threat, less tangible but just as disturbing for colonial administrators: the specter of “detribalization.” This was an explicitly social concern that focused on the traumas attendant on Africans’ transition from a “primitive” existence rooted in the communal structures of family and “tribe” to a “modern” individualistic society brought about by European colonialism. Colonial administrators feared that Africans who failed to navigate this transition were especially susceptible to joining anti-colonial movements like Kenya's Mau rebellion, which they saw as atavistic.Footnote 32

Gazzard's position as planner placed him in the center of colonial debates over how best to ease Africans into modern urban life. Jinja's population boom that came with developmentalist projects like the Owen Falls Dam (1949–54) provided the impetus for experiments in planning and housing schemes.Footnote 33 As a key site of industrial development, Jinja was freighted with optimism and anxiety for British observers: “Jinja,” the liberal journalist Vernon Bartlett wrote in the Daily Chronicle in 1950, “may develop into a second Johannesburg, devoid of any moral standards to replace the moral discipline it has destroyed. With the right sort of planning and control it may become the most hopeful place in Africa.”Footnote 34

But what was “the right sort of planning”? The question dogged Gazzard throughout his time in Uganda, and his answers underwent a profound shift over the course of the 1950s. His initial approach reflected the developmentalist ambitions of Britain's colonial project in the postwar period and was applied through universalist notions of built space and social progress. By the end of his tenure, though, Gazzard rejected the idea of grafting European forms into colonial contexts.

In his 1952 plan for Jinja, Gazzard advocated dividing the African population into discrete “neighborhoods” of roughly 10,000 residents that would form the basis of a new communal life. The idea of the “neighborhood unit” was well established in planning thought by the 1950s. Its roots were in pre–World War I America, but the concept had been taken up by British planners and integrated into the garden-city movement as a way to encourage close-knit sociability amid the conditions of modern urban life.Footnote 35 From Britain, it had spread to the colonies during the 1940s and ’50s via paladins of “tropical architecture” like Robert Gardner-Medwin, Otto Koenigsberger, Maxwell Fry, and Jane Drew. These itinerant experts advocated the neighborhood as a “modern” form universally suited to foster healthy individuals and cohesive communities.Footnote 36

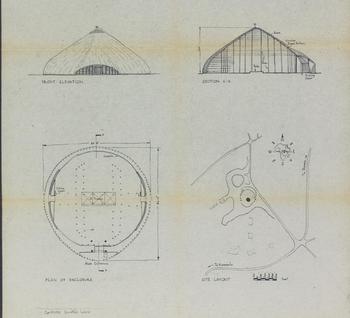

For Gazzard, the idea of African neighborhoods offered a chance to salvage the cohesive communal glue of the “tribe” while integrating the African population into an industrial urban setting. “Tribal sanctions are already disappearing,” he observed, “and in their place new standards of discipline have to be developed.” In terms reflecting British garden-city ideals, Gazzard argued that the new neighborhoods would offer “an improved environment comparable in amenity to that enjoyed in the countryside,” as well as an opportunity for Africans to become “acculturated.” This acculturation would eventually allow “the African to take his place as a citizen together with Asians and Europeans in the multi-racial population groups elsewhere in the town.” The planned neighborhood, Gazzard concluded approvingly, would be a petri dish for a new African culture that would “not be the image of the European, but probably a veneer of basically Western culture with vestigal tribal features. The introduction to this culture will be in the Neighbourhood followed by observation and imitation of the European, in the home, in the streets, and at work.”Footnote 37 Each neighborhood unit's operation and design followed Gazzard's emphasis on “tribal” communal solidarity wedded to social and economic meliorism. This philosophy fit perfectly with the policy of the Uganda Protectorate in the early 1950s, as colonial administrators searched for new forms of African “community” to replace the bonds of the “tribe.”Footnote 38 Like new towns such as Harlow, Basildon, and Crawley, whose foundations were beginning to pepper the countryside of southeast England in the decade following the 1946 New Towns Act, Jinja's neighborhoods would be grouped around a carefully planned array of industrial and social services. As figure 1 shows, the neighborhood was laid out on rationalized lines, with strict zoning and transportation requirements. “Impressive vistas and grandiose or curvaceous layouts” were to be shunned in favor of an intimate, small-scale environment scaled to “the individual and walking distance.”Footnote 39

Figure 1 The spaces of development: Diagram of Jinja ideal neighborhood from Gazzard's Specifications for Structural Standards of African Housing, 1953. Roy Gazzard Papers. Courtesy of Durham University Library Special Collections.

These neighborhood designs reflected Gazzard's universalist view of modernization and industrial development. Western spatial forms were to lubricate the African passage to the industrial future, allowing Africans to evade such ills as urban anomie and slum living.Footnote 40 During his tenure in Uganda, Gazzard's emphasis was on the universal rather than the particular, space over place. He did not value local symbolic forms as intrinsically important but as a stabilizing mechanism that would stave off the ill effects of “detribalizing” modernity. When he returned to England and wrote retrospectively decades later on his time in Uganda, though, these emphases flipped, and he spoke regretfully of having “introduced the village architecture of Sussex into Africa” and having “tried to build Welwyn Garden City in Kampala.”Footnote 41 The best approach to attain stable African communities, he now argued, was not to copy the forms of successful European cities and buildings but rather to replicate the spatial contours of “traditional” African dwellings in a modern urban environment.

Between writing plans for African neighborhoods early in 1953 and returning to England in 1954, Gazzard's design philosophy underwent a seismic shift that played out against a dramatically changing political backdrop. The foundation of the Uganda National Congress in 1952 marked the beginning of African nationalist politics in the Protectorate; whereas earlier African political movements had aimed to improve the conditions of the colonial status quo, the new party's goal was complete independence.Footnote 42 By the end of the decade, Uganda had three nationalist parties advocating self-rule, and Ghana's break from Britain in 1957 provided a model of African nationalist development free from colonial rule. Within this new political context, Gazzard renounced his advocacy of normative western forms. “My interests,” he later wrote in an unpublished account of his time in Jinja, increasingly “turned to how and where Africans built in the countryside and the comprehension which they had for their clan and its place. African dynamism is to a very large extent rooted in the soil, the harbinger of fertility.”Footnote 43 The designer's role, he now argued, was to discover the essence of the local building traditions and to recover their “sculpturesque” qualities to reproduce their psychic impact.

But as his reference to “African dynamism” indicates, Gazzard's vision of what constituted “traditional” African architecture was refracted through a mystical and romantic lens. “When the sophisticated rhythms of African drumming were converted into mathematical formulae,” he argued, “they precisely coincided with the curves of local buildings.”Footnote 44 In a 1960 lecture, he described this discovery as an epiphany: while researching the royal tombs of the Baganda near Kampala toward the end of his tenure in Uganda, he visited an “old Chief” who, over glasses of orange juice, described how the Bagandan royal huts were constructed. The old man's description, wrote Gazzard, awakened him to the possibilities in a culture where “craftsmanship of any kind was at a premium”:

These fascinating and beautiful huts are much more elaborate than the elementary beehive huts of rough grass construction and were obviously buildings of considerable monumentality and significance. Internally, they present a unique and ingenious solution to the problem of enclosing space using exponential or logarithmic curves, which is the stylistic, almost classical, tradition of African work. The dynamism which is the fundamental quality of all African sculpture is expressive of the principle of growth and increase symbolising the imminent energy which Africans believe carries a spirit force from the tomb to the universe.Footnote 45

While the vernacular building tradition around Jinja had left him cold, this conversation showed him the “curious illogical sophistication” of the Baganda rulers. His papers contain both perspective drawings and schematic plans of the huts, indicating that he took the mathematical details of their construction very seriously (see figures 2 and 3): “There is promise for architecture in Africa if traditional work of this description can be developed into new three-dimensional forms of enclosure using modern materials and techniques.” African architects needed to abandon their “slavish adherence to alien two-dimensional linear and rectangular culture from which we ourselves are seeking to escape,” and rediscover “the truly African sculpturesque tradition which should be the inspiration for the nascent architects of that continent.”Footnote 46

Figure 2 Places of “permanence and security,” part 1: A drawing of Baganda Tombs, Roy Gazzard Papers. Courtesy of Durham University Library Special Collections.

Figure 3 Diagrams of Baganda Tombs, Roy Gazzard Papers. Courtesy of Durham University Library Special Collections.

Here, Gazzard eschewed the existing vernacular tradition of building in the Busoga countryside around Jinja in favor of the “high” art of a past civilization. These forms offered a smooth, mythical evocation of “African” symbolism that elided the colonial interlude and any reference to modern nationalism. His emphasis on the mystical energy rooted in the built forms of precolonial Buganda foreshadowed his later design of Killingworth Township, where he would evoke the form of the Northumbrian castle town—not as historical pastiche but as a psychologically necessary bonding agent between people and place. Gazzard's experience in Jinja became particularly valuable in retrospect, and he returned to it repeatedly in his writings during the following decades. As Britain's colonial holdings dissolved and planning in the newly independent Commonwealth nations became competitive commissions rather than imperial service, he increasingly emphasized the importance of difference and particularity. Place, not space, dominated his discussions of his Uganda experience.

Jinja offered Gazzard an ideal laboratory to ply his trade as a “social engineer,” free of the more restrictive conditions confronting planners back in Britain. The links between colonialism and urban modernism have been extensively documented. Paul Rabinow's characterization of Europe's colonies as “laboratories of modernity” emphasizes the expanded scope for creativity experienced by colonial architects and administrators stifled by inertia in the metropole.Footnote 47 Similarly, Gwendolyn Wright argues that experiments in planning colonial cities offered French planners a chance to work out some of the political, social, and aesthetic problems they confronted back in France.Footnote 48 The German architect Ernst May, whom Gazzard befriended while in Uganda, wrote of the African landscape as a “tabula rasa” on which there was no trace of human civilization. In the colonial context, May believed, the creative genius had the power “not only to design a region on paper but could organically shape everything down to its smallest detail.”Footnote 49

The planning situation confronting Gazzard in eastern Uganda was of course far from May's tabula rasa, and implementing colonial plans involved contestation and compromise.Footnote 50 Yet Jinja did afford the untested young architect an opportunity he almost certainly would not have had in Britain—the chance to formulate urban policies ranging from sweeping structure plans for new communities composed of tens of thousands of people to the minute details of individual homes.Footnote 51 As it did for many of his peers, colonial service gave Gazzard a crucial starting point as a planner, and he parlayed his experience into a long career as an expert—in new-town planning, in “social engineering” for communities in social and economic transition, and in the academic discipline of geography.Footnote 52

When his contract expired and he turned his attention to securing work as an architect-planner in Britain, Gazzard received a glowing recommendation from Henry Kendall, who commented particularly on the younger man's “drive and enthusiasm” in carrying out his duties.Footnote 53 This trait translated well into his work at Killingworth, where he got a second shot at social engineering for a community in transition. Northumberland, he thought, “was very much like Africa—a frontier region, a place of challenge.”Footnote 54 As this analogy indicates, colonial structures of thought did not simply dissipate when the empire's political sinews were severed, and the new-town environment offered an attractive outlet to redirect colonial expertise.Footnote 55 In Gazzard's case, colonial experience provided a creative reservoir to draw upon in designing a new town in Northumbria's derelict postindustrial landscape.

Among the Bankers

Between Jinja and Killingworth lay an interval of nearly a decade, though. The Britain to which Gazzard returned in 1954 offered diminished opportunities for ambitious urban planners. Whereas the 1946 New Towns Act and the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act had set urban planning at the center of postwar reconstruction, the Conservative election victory in 1951 signaled a turn toward private initiative and a laissez-fair approach to development.Footnote 56 Fourteen new towns were established in the half decade following the war's end, but only one (Cumbernauld New Town near Glasgow) in all of the 1950s. It was, one architect-planner opined, “one of the dimmest decades in our architectural history.”Footnote 57 Fittingly, in this context of property speculation and the scaling back of public sector planning, Gazzard found a job as the lead architect for the Midlands section of Barclay's Bank in Birmingham. His role would involve designing bank buildings (drive-through architecture particularly intrigued him) and also helping the bank take advantage of the opportunities provided by Birmingham's urban renewal program. Gazzard accepted the position and remained at the bank until 1960.Footnote 58

Working as a bank architect in Birmingham was not what Gazzard wanted to be doing for the rest of his life. It is likely that he missed the opportunities for experimentation and adventure that his colonial post had offered. He approached the Architectural Press with the idea of writing a book on the design of modern banks but was rebuffed—there was little demand for the subject.Footnote 59 Even as he pursued his work at the bank, he followed Birmingham's urban renewal campaign closely, drawing comparisons to his experience in Jinja. The symbiotic relationship between ambitious public works campaigns and cash-flush property developers transforming 1950s Birmingham was “strangely comparable,” he thought, to the booming industrial expansion he had witnessed in Jinja.Footnote 60 The comparison indicates that Uganda remained present in his mind, as do the numerous clippings of Uganda's move toward independence contained in his papers.Footnote 61 Also, it was toward the end of his tenure at Barclay's that he presented his paper on “The Royal Tombs of the Baganda,” an essay that shows him not only recalling his African experience but also reformulating it.Footnote 62 Gazzard's four-year stint in Uganda distinguishes him from his many contemporaries who dedicated much of their lives to “imperial careering.”Footnote 63 Yet his persistent recourse to his colonial experience as a site of comparison and inspiration suggests that it played an enormous role in shaping his professional identity.

Birmingham grated on Gazzard. He never been there before taking up the job and “found the place name and environmental prospect unappealing.” Comparing the city to the cars it produced—“a vehicle for profit, privilege, and pleasure”—he speculated that Birmingham, was in danger of becoming a “consumer durable.” “In the context of consumer choice,” he asked, “is it a city in which people will want to live if other options remain open?”Footnote 64 In 1960, Gazzard made his own choice clear and took a position as chief architect-planner for the Peterlee New Town Development Corporation, and settled in nearby Durham.

Peterlee was part of the initial wave of postwar new-town construction and thus well advanced by the time Gazzard began working there in 1960. Also sited in northeast England, it had some similarities with Killingworth, designed as it was to offer a hub of new industry in a region devastated by the decline in the coal-mining industry. The town has a fascinating design history in its own right: its original planner was Berthold Lubetkin, one of Britain's foremost modernists and a disciple of Le Corbusier. Drastically departing from the dispersed neighborhood concept of many of the other early new towns, Lubetkin's 1948 design for Peterlee had envisioned a tight-knit central core formed by a series of geometrically arranged high-rise buildings. The town as constructed was far more conventional—a series of delays and opposition to Lubetkin's plan led to his frustrated resignation in 1950, and in 1960, by the time Gazzard arrived, the nearly completed townscape resembled its new-town counterparts in most respects.Footnote 65 Lubetkin's plan probably looked to Gazzard like a missed opportunity, since he later cited its compact structure as a key inspiration for his work at Killingworth.Footnote 66 Despite his title as chief architect, Gazzard had few outlets for creative design in Peterlee, and he stayed a scant two years. When the Northumberland County Council approached him with an opportunity to design a town from scratch, he readily accepted, taking a position at Killingworth in 1962.

Social Engineering Comes Home

Over the summer of 1969, Yorkshire Television aired a series called “I Am an Engineer,” intending to show teenagers “the fascination of engineering.” Those profiled were mainly drawn from the ranks of mechanical and civil engineers, but the fifth episode shifted gears, focusing on “Roy Gazzard, Social Engineer.” The program emphasized that designing cities was not simply a labor in physical engineering but also a massive social design project, exemplified at Killingworth, a town Gazzard was designing just north of Newcastle. After cataloguing the new town's key structures, from the modernist Gas Council Research Station to the “castle formation” of the city's core, attention shifted to Killingworth's social design: “The most striking thing about Killingworth is not its Civic Trust awards or architectural prizes, but its social philosophy.” Gazzard's interest, viewers learned, was not in the form of towns but in the way they feel—their “sense of community” and the way people lived in them.

At Killingworth, a voiceover explained, Gazzard had founded an ecumenical Christian council to serve as “an instrument of compassion”: from the beginning, they would work beside the city administrators and health workers to provide for “whole man health.” Amid Britain's “foot-loose mobile society,” it was essential to “develop a community with roots. The spiritual quality of the environment has to be analysed and whatever may be required to establish new traditions and the continuity from past to future has to be preserved.”Footnote 67 For Gazzard, the “spiritual quality” in this case was an explicitly Christian one, and Killingworth's design called for the sacred and secular to be intertwined in Communicare—a social-services center housed at the heart of the Citadel. Although it was to be a small city of only 20,000, Gazzard saw Killingworth as something far more significant: it would be a community grounded in Christian ethics, and the fulfillment of his “Christian calling.”Footnote 68

The program concluded with a turn to the future: in the final thirty years of the century, Gazzard predicted, Britain's population would annually increase by the equivalent of a city the size of Leeds,Footnote 69 and more than half of that new population would live in completely new communities that would have to be constructed specifically for them: “This is a re-settlement programme equal in magnitude to any which has been carried out in Israel, India or Africa yet community development techniques have not yet been developed which will ensure the success of the operation and no forum exists in which social engineers can discuss the problem or equip themselves by study or qualification to deal with it.” This ominous set of comparisons invoking Britain's need for social engineers underlined the importance of Gazzard's international experience visiting Jewish cooperative settlements during his postwar service in Palestine and designing “multi-racial townships” in Uganda.Footnote 70 It was now time for planners to put their skills to use back home in order to guide Britain into the twenty-first century. The conclusion had jarring implications: future population pressures would be so pronounced that Britain ought to follow examples of “re-settlement” abroad. While the references to massive population exchanges in Israel, India, and Africa go unexplored, their connotations were hardly democratic, and implied the necessity of coercive force.Footnote 71

The essentials of Killingworth's planning principles appear in this brief youth television program. The first of these was an emphasis on continuity with the local past by tapping into historical imagery, iconography, and the spatial distribution of Northumbrian castle towns. These connections with the medieval past would be recurrent themes in Gazzard's description of his work and in the town's promotional literature. Secondly, the town was conceived as a riposte to Britain's postwar welfare state, which Gazzard accused of neglecting Britons’ spiritual needs. Killingworth would cater to people in their totality rather than focusing solely on their material well-being. Finally, it was to be a city based on imperial knowledge, building on Gazzard's experience in planning for diverse and uprooted populations.

Engineering a Castle Town

By the time the television segment aired, construction at Killingworth was just getting underway after a decade of preparation and planning. Gazzard designed Killingworth as an architectural totality—each part of the city would combine to impact the inhabitant at a visceral level. The spatial configuration of the “township”—Gazzard's team eschewed the title “new town” because of its “association with immaturity”— would resonate with the mystical properties of the local landscape and the cultural sensibilities of its people.Footnote 72 As we have seen, Gazzard formulated this design philosophy—pivoting away from “universal” European planning models toward the vernacular building styles of the defunct Buganda kingdom—in the context of the faltering of colonial development in Uganda and the rise of African nationalism. His work in the 1960s would increasingly emphasize the importance of place and local tradition in urban planning.

Gazzard's plan for Killingworth, begun in 1963, envisioned a comprehensive physical design complemented by a spiritual component that would be achieved through a union of Christian ethics and the secular institutions of the local state. These components can be seen in Killingworth's “castle town” elements—Gazzard's chief architectural contribution to the city—and in the institutional vehicle through which Christianity would infuse the new town: the “Communicare experiment.” Within two decades, Killingworth itself was a failed experiment. Gazzard's castle townscape was razed in the 1980s, and only the “moat” remains. Communicare is likewise defunct, and its physical home has been replaced by a parking lot. Killingworth has now been a typical British suburb longer than it was a modernist showpiece, and analyzing its vanished core is an exercise in archaeology.

Killingworth is unusual among Britain's new towns in that a local authority rather than the central government sponsored it.Footnote 73 In August 1959 the Northumberland County Planning Department received government approval to establish a new town just north of Newcastle.Footnote 74 The town was to be a “growth point” to receive industry and people pushed out of congested areas of Tyneside by the ambitious slum clearance and urban renewal projects initiated by T. Dan Smith's Labor-led Newcastle City Council.Footnote 75 The Northumberland County Council invoked the 1952 Town Development Act, which provided for rural councils bordering large cities to serve as “receiving authorities” in partnership with a nearby urban “exporting authority.” The most tangible effect of Killingworth's status as a county-sponsored new town was that its planners lacked the extensive resources of the official new towns with their state-funded development corporations.

Killingworth reflected this difference in its modest size: while Cumbernauld New Town had a target population of 50,000, Runcorn of 90,000, and Milton Keynes of 250,000, Killingworth was to house a paltry 20,000 souls. Its siting was not particularly auspicious. Part of the appeal of the area was that the land had been scarred and used up by the coal industry, providing a cheap and readily available tract of land that could be repurposed for new industry and dwellings. The County Council's ambitions were thus both to revive a devastated natural landscape and to fill a social need with new employment and housing. Professionals in new industries like petroleum research would rub shoulders with unskilled former mine workers, who could find a job in one of the town's planned warehouses. This “model town's” careful mix of counsel housing and owner-occupied homes would “encourage integration” and ease the region's depressed industrial communities into a postindustrial future.Footnote 76 “The class war must be seen to have been won,” a Northumberland housing committee member said of the area's redevelopment.Footnote 77

The village of Killingworth was so miniscule that Whitehall opposed the invocation of the Expanded Towns Act, proposing instead that people from Newcastle's densely packed districts be “decanted” to out-of-town housing estates. With existing new towns in northeast England at Peterlee and Newton Aycliffe (both in County Durham), the central government contended that a further new town was unnecessary. Leery of further urban sprawl on the county's southern boundary, the Northumberland County Council “decided they would go it alone” without relying on funding from Whitehall, and became the first local authority outside of London to sponsor a new-town development plan.Footnote 78 Funding for the town was cobbled together from a hodgepodge of sources; the Northumberland County Council, the Longbenton Urban District Council, and Newcastle City Council provided the bulk of the funds, while Whitehall provided basic infrastructure.Footnote 79 Once the new town had received government approval, the Northumberland County Council moved to appoint a coordinating architect-planner to produce a design for the town. Their final choice was Roy Gazzard, then in his second year as chief architect at Peterlee. Gazzard accepted the job and submitted his initial plans to the Northumberland County Council in April 1963. He chose the title of “director of development” rather than architect-planner, regarding the former as more suited to his holistic approach to social engineering. While Gazzard's papers provide no background on the details of his recruitment, he was likely seen as an ideal candidate for designing the new town based on his experience at Peterlee and in the parallel “frontier” environment in the empire.Footnote 80

The environs of the future town encouraged such comparisons. As can be seen in figure 4, aerial photographs of the Killingworth site in the early 1960s show a landscape of open moorland punctuated by scattered waste dumps and occasional ponds where coal mining had caused the ground to settle. The first edition of the new town's handbook, directed toward prospective residents, opened with a downbeat tour of the land. Development would progress on an “unsightly area of land” that had “been reduced by mineral exploitation to the level of a semi-rural slum with slag heaps and flooding,” resulting in “an overpowering atmosphere of dereliction and depression.”Footnote 81 The new town was an ecological rescue project as well as an exercise in urban development and job creation. The Development Group's first design project reflected this goal of transforming the land from an industrial area to a postindustrial city focused on leisure and the creation of white-collar jobs.Footnote 82 The Northern Gas Board headquarters, a sleek modernist building designed by the Newcastle firm Ryder and Yates, provided the town's first four hundred jobs, and signaled a shift to a local economy based on service and research work. An abandoned mineshaft just north of the building was the next target for development; the subsided ground around it was flooded to form an artificial lake planned as the chief leisure site for the town's population.

Figure 4 Developing the frontier: Killingworth Development Group offices, early 1960s. Courtesy of Northumberland County Council and Newcastle Libraries.

Seeing the site as an equally important avenue for “the social engineering of the whole township as it was a civil engineering operation,” Gazzard fastened on the lake as a community lodestone—it would serve as both a therapeutic social gathering site and a source of symbolic meaning.Footnote 83 The former emphasis grew out of a widespread concern among planners about the implications of affluence and increased leisure time.Footnote 84 Even as Harold Macmillan assured the British public that they had “never had it so good,” sociological studies produced during the late 1950s stoked anxieties over the fracturing of communal solidarities and a retreat to the private home, particularly among the working classes.Footnote 85 Killingworth was constructed on the assumption that Britain's postwar growth would continue. As a publicity brochure by the town's Development Group put it, Killingworth would cater to an affluent population with wide-ranging recreational interests and ample leisure time.Footnote 86 The lake would provide a year-round recreational setting and ensure a communal outlet to compete with television's antisocial pull.

Just as crucial for Gazzard, though, was the lake's symbolic function. Most of Britain's first wave of new towns had failed, he believed, because of their planners’ emphasis on space over place. Relying on abstract conceptions of urban design, planners had created nondescript agglomerations of streets and buildings that called to mind Gertrude Stein's reputed description of Oakland: “When you get there, there is no there, there.”Footnote 87 Planning was as much a spiritual process as a technical one, and effective urban design had to provide “a place anchor which links it securely with the ambience or ethos of place. … It is this quality that is absent from much of twentieth-century place-making.”Footnote 88 Killingworth's two principal place markers would be the lake and the citadel. As he had done in his later discussions of Ugandan architecture, Gazzard sought inspiration in the spatial distributions of examplary local architecture from the past and found it in the design of Durham and in Northumbria's medieval castles. Admiring Durham's compact structure, which had sprouted organically along a narrow peninsular formed by the River Wear, Gazzard intended Killingworth's lake to have a similar shaping effect. It would “read as a river threading its way between buildings,” and when approached from the south, would give visitors the sensation of crossing a castle moat.Footnote 89 The lake's impact would resonate in an affective, subliminal register, creating the impression of transition from the formless space of Newcastle's suburban sprawl to a bounded, well-defined place.

The lake's dual role as leisure magnet and symbolic “moat” rooting the town in the historical Northumbrian landscape underlines the dual nature of Gazzard's design philosophy. Killingworth was intended to transcend Britain's postwar moment to link a mythic medieval past with an equally mythic “space-age” future. This ambivalence is reflected in figure 5, Gazzard's architectural model for the town, which features a motorway-cum-drawbridge spanning the lake. Cars crossing the bridge share the road with a monorail, that staple of space-age urban designs of the early 1960s; for all his backward-looking references to fortified castle towns, Gazzard drew from the same imaginative reservoir as Fred Pooley's initial “monorail city” plans for Milton Keynes, Arthur Ling's early designs for Runcorn New Town, Montreal's Expo 67, and Archigram's whimsical “Plug-In City” concept.Footnote 90

Figure 5 Model of Killingworth Township, facing north. The “walled town” effect was to be achieved through progressively higher building levels from the modest lakeshore housing on the fringe to the skyscrapers of the Citadel in the center. Courtesy of Northumberland County Council and Newcastle Libraries.

The structure of the town was equally poised between the futuristic and the historicist. The four cardinal streets were Southgate, Northgate, East Bailey, and West Bailey. The “Baileys”—references to the outer walls of a medieval castle—looped around the town's center, while Southgate plunged under the central megastructure “as if through a gateway,” to emerge as Northgate. The buildings would rise gradually toward the center. The courtyards of low-rise housing just within the baileys were labeled “Garths,” and these gave way to the appropriately named “Killingworth Towers”—concrete slab blocks that adjoined the central citadel. The buildings in the Garths were arranged in a “haphazard and informal medieval manner,” with an equally asymmetrical pattern of windows, and linked to other courts by “a hemmed in pedestrian system of narrow chares inspired by Newcastle's ancient confused riverside.”Footnote 91

The Towers, which had by the early 1980s become Killingworth's most notorious landmark, were six-to-ten story, deck-access maisonettes connected by “streets in the sky.” The design drew heavily on the example of Britain's best-known modernist housing project, Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith's Park Hill Estate in Sheffield. Like that of Park Hill, the Towers’ design was intended to replicate the conditions of Britain's terraced working-class housing, with their tight-knit bonds of conviviality. Prospective tenants were assured that they were moving into a “vertical village.” The deck-access design would prevent the isolation intrinsic to conventional tower blocks, as the “high level streets or decks will encourage the growth of a community without reducing the privacy which everyone wants to enjoy within his own home.” Perched high above vehicular traffic, neighbors “can meet and talk, or watch children playing in the public gardens below.”Footnote 92 The original design called for a total of 1,454 high-rise dwellings to be built on both sides of the Citadel, but only the 740 on the west side ever materialized. The eastern housing was built after the end of Gazzard's tenure and followed more conventional housing layouts.

Unsurprisingly, Killingworth's Development Group dialed back the allusions to medieval castles in the promotional literature for the housing developments, opting instead for an emphasis on the homes’ modern conveniences. Floor plans showed a generous layout, contrasting sharply with the traditional “Tyneside flats” that many residents were coming from. Whereas the bulk of local working-class housing was exceptionally small and overcrowded and often lacked indoor plumbing, Killingworth's apartments were equipped with a “day room” and “evening room,” Formica kitchens, and gas heating and were wired for television.Footnote 93 For residents arriving from Victorian-era houses, such modern amenities were a significant draw. A 1969 survey confirmed this largely positive attitude, noting that “residents generally liked their houses. The least critical were those who come from condemned or overcrowded housing.”Footnote 94 As one mother of six put it, she moved from her neighborhood on the western fringe of Newcastle “because she liked the idea of a house no one had lived in before, because it seemed a step up from that slum.”Footnote 95

While the promotional literature played up the Towers’ cutting-edge design and modern amenities, Gazzard's own ruminations were, typically, spiced with a mélange of historical references to the medieval past and paeans to social engineering. Slum-clearance programs that bulldozed neighborhoods and “decanted” the residents to high-rise towers, wrote Gazzard, often overlooked the thick networks of “social interdependence and mutual aid” animating working-class streets. Such ties “sprang naturally from a people made gregarious in their adversity and by their architecture.”Footnote 96 Sheffield's Park Hill had shown that “the desirable qualities of the old way can be recast in modern terms, in fact must be recast if the threads of man's development in relation to his environment is to be preserved intact.”Footnote 97 In terms redolent of his colonial attempts to retain “tribal bonds” in Uganda's urbanizing society, Gazzard argued for the importance of blending the bonds of working-class “community” with the individual's need for privacy. Each courtyard, like the one depicted in figure 6, would give the sense of “shelter and enclosure” for which Gazzard believed Northumbrians intrinsically yearned, and would facilitate relaxing communal activities like “gossiping and strolling.” Unlike most postwar housing estates, a “Baroque sinuousness” would supplant “the tyranny of framed facades, right angles and slab blocks.” From a distance, the Towers, each named after a Northumbrian castle, would give the impression of a continuous curtain wall enclosing the central Citadel.

Figure 6 The image of a convivial environment: A concept drawing of several of the Killingworth Towers seen from a “street in the sky.” Courtesy of Northumberland County Council and Newcastle Libraries.

The Citadel's design reflected the blend of futurism and archaism that animated the entire town plan. For inspiration, Gazzard drew on the compact medieval form of Durham as well as the megastructural center of Cumbernauld New Town and Bertolt Lubetkin's unbuilt plans for Peterlee. Residents perusing the town handbook they were given with the keys to their home would read, “The intention has been to create an acceptable environment for a ‘space age’ community more affluent than previous generations and more critical of the quality of its built environment.” Rather than the scattered array of individual buildings that formed the center of most new towns, Killingworth would be grouped around “one huge space” partitioned by decks and screen walls, all forming a cohesive whole “in the form of a complex, sophisticated modern equivalent of the Greek Agora.”Footnote 98

As in Cumbernauld's central megastructure and much of the “traffic architecture” of the period, the design was based on the principle of separation between cars and people. The north-south axis would form the town's spine, with the Citadel built over it. Car traffic would be canalized along access ways beneath the center to convenient parking garages, while pedestrians, funneled in from the housing areas along elevated walkways, would dominate the second level, with its grocery stores, shopping arcades, and “gossiping grounds.” Crowning the structure would be an open deck upon which would be built offices, community services, and high-rise apartments.

As in the Development Group's promotional literature on the Towers, the “space-age” technological aspects of the town center were foregrounded in the town handbook, rather than its symbolic allusions to the local past. In his writings and lectures, though, Gazzard emphasized the importance of historically laden forms in imparting symbolic meaning and psychological consolation for the town's residents. “The walled town is comprehended by ordinary people in Northumbria for the strength and security it represents. Certainly in Northumbria people know and love their castle towns and it seemed logical to communicate the planning concept to ordinary people in this idiom.”Footnote 99 How did Gazzard “communicate” his medieval vision? Unlike the ornate historicism of design projects like Vienna's Ringstrasse or Disneyland, Killingworth's designer embraced the clean, functional lines of architectural modernism, relying on the subliminal power of massed geometric forms to pluck viewers’ affective chords. For Ugandans, Gazzard had contended that the circle filled this need; in the English north, he held, psychic wholeness came through the sheer, blocky, dour mass of the castle.

Killingworth's town center was therefore to resemble a keep “dominating the landscape.”Footnote 100 The intended effect can be appreciated in figure 7: The sleek glass office block rising above the entire edifice was conceived as a modern incarnation of Castle Rushen on the Isle of Man, with the Woolco shopping center below serving as a “low bastion.” The Communicare Centre and administrative buildings in the town's southeast corner formed “the castle's east demesne.”Footnote 101 The rough concrete cherished by Brutalist architects for its honesty and raw intensity fit perfectly into Gazzard's vision for a town in the “masculine north-country tradition with sheerline detailing. Tone values will be black, white and grey with colour limited to small areas at the human level.” Together with the “fortified sites” of Northumberland, Gazzard's design team emulated “the rock group of Cathedral, Castle and Monastery above the Wear at Durham.”Footnote 102

Figure 7 Places of “permanence and security,” part 2: The Killingworth Citadel “dominating the landscape” in 1983. In the foreground are the “low bastion” of the shopping mall and a “street in the sky” leading to the Towers. Deterioration is already evident in the missing sign letters, though the child on roller skates looks happy enough. Courtesy of Stephen Brain.

For Gazzard, Durham was “one of the most civilised places on earth” and “all that a town ought to be.”Footnote 103 It was the intimately connected nature of the cathedral town's “rock group” that most appealed to Gazzard, and just as Durham had succeeded in spatially marrying the sacred and the profane, Killingworth's Citadel was planned to provide a Christian foundation for the town. The central piece of the planned integration of secular and sacred in the Citadel was Communicare, a social-care strategy intended to “meet the ‘whole man health’ of the individual, his physical and spiritual needs.”Footnote 104 The welfare state, a Communicare brochure contended, was one dimension of a sick “materialistic society” and was “aimed at meeting only the physical needs of the population.”Footnote 105 This criticism built on contemporary concerns over the Welfare State's failure to care for its most vulnerable members—concerns that culminated in the 1968 Seebohm Report on Social Services.

In the early stages of planning, Gazzard prevailed upon local leaders from the Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Catholic Churches to form an interdenominational Christian Council. Rather than having several small church buildings on individual plots of land, he argued, the Christian church would be better represented as a single ecumenical body. Making a virtue of necessity, the Killingworth Development Group partnered with the Killingworth Christian Council to replace the social-development services found in more generously funded official New Towns with a voluntary organization rooted in the Christian laity. Killingworth's status as a new town with a totally designed environment was as promising for spiritual engineering as it was for social engineering. For its advocates, Killingworth's “Communicare Experiment” reached far beyond Tyneside. “Can we match in human terms the efforts the planners have made in Concrete?” asked a Communicare fund-raising brochure. “If we can show that Communicare works here, this will have important consequences not only for Killingworth but for the Christian Church, town planning and people generally.”Footnote 106

Gazzard's overt claims to be engineering a Christian society are particularly striking when viewed against the conventional narrative of new-town construction. For planning historians, they form a high point of technocratic discourse and state legislation regarding land use and decentralization, while social and cultural historians focus on their association with upward mobility and affluence and their successes or failings in fulfilling these expectations.Footnote 107 Both narratives emphasize the secular, rationalist, forward-looking nature of the new towns project and their place as “emblems of post-war modernity.”Footnote 108 Gazzard's plan for Killingworth thus appears as a bizarre anachronism harking back to a vanished Christian past.

Killingworth also complicates the received view of modernist planning in general. Since the late 1960s, critics on both the right and left have characterized urban planners as arrogant technocrats—James Scott's eggheaded priests of high modernism, driven by “a rejection of the past as a model to improve upon and a desire to make a completely fresh start.” For Scott, the archetypal modernist planner is Le Corbusier, whose “repudiation of tradition, history, and received taste” provides an ideal type for the ambitions of the profession as a whole.Footnote 109 Killingworth's design, by contrast, showcased a modernism that looked to the past as much as to the future for inspiration. In Killingworth, past forms offered the promise of psychological comfort for the individual and spiritual revival on a socio-cultural level. If moats and castles formed the new town's warp, futuristic “space age” design was the weft. Cutting-edge building designs, spacious and well-appointed kitchens, and an emphasis on leisure promised a thrilling replacement for the drabness and drudgery of the Victorian cityscape. The parallel threads of futurism and historicism blur the opposition between historicism and modernism in postwar urban design—an overweening confidence in technological and social engineering could coexist with a severe unease about Britain's social trajectory and a desire to recover a mythic pre-industrial cultural totality. For Gazzard, this twinning of arrogance and anxiety grew directly from his colonial experience, which formed a crucible for his philosophy of urban design.

Conclusion

“By stepping back into the past, Killingworth is making strides into the future.” Surprisingly, this praise for Roy Gazzard's creation was not directed at the new town's medieval inspiration. Rather, the “past” to which this Financial Times article on Killingworth was referring was much more recent: Uganda in the 1950s. “The elemental conditions of the African environment,” the article continued,

can bring home very forcefully the nature of the need to live in communities as a defense against a hostile world. Our technological world is no less hostile or elemental than the African one. Only appearances are different. In part, Killingworth is an expression of this knowledge and the experience acquired by its chief architect. Northumberland was perhaps a very appropriate place for Mr. Gazzard to superimpose, architecturally, the wisdom of the primitive on to present day technological sophistication. The North has a long industrial history. Its social structure tends toward the feudal. Its land resembles Africa—there is a striking similarity between the Cheviot Hills and the Northern Transvaal, the Vumba or the Highlands of East and Central Africa.Footnote 110

In this snapshot of Killingworth, time and space flatten, fold, and reform like an origami figure. Gazzard, the article contended, had “superimposed the wisdom of the primitive” on the industrial townscape of northern England. Turning the industrial-era pit head into a postindustrial leisure lake would break the social, psychological, “even spiritual” problems that Gazzard believed were unique to “the environment of the old industrial communities.” Such communities “were, and to some extent still are, prisoners of the pit head, steel works or shipyard. The place of work at the end of the street became the citadel of the community.” With the decline of the industries that shaped their existence, such communities needed new symbols of “permanence and security.”Footnote 111 For “detribalizing” Africans in Uganda, Gazzard had offered first the modern neighborhood, then pre-colonial Baganda's logarythmic curves. He gave the working-class population of Northern England a moat and a concrete citadel.

This article has argued that Gazzard's attempt to channel his colonial experience into Killingworth's design grew partly from a jaundiced reading of contemporary history—only the firm hand of social engineers could amend the traumas that modern time wrought. Political and socio-economic shifts were eroding “traditional” forms of authority, whether based in the Ugandan “tribe” or the Northumberland factory. The architect-planner's task was to repair the resulting social and psychological wounds through creating place-specific symbols that would provide consolation amid rapid social change. But Gazzard's case also reflects broader trends in twentieth-century English culture. One of the most fertile impacts that colonial studies and postcolonial scholarship have had on British historiography is their recognition that colonialism was a two-way process, the forms and logic of which were imprinted on the colonists as well as the colonized. Rather than a distant process that played out “over there” for centuries before gracefully fading away, colonialism shaped British society and Britons’ self-understanding, and the loss of the empire had an equally profound impact. While Paul Gilroy characterizes this effect as a deep, if sublimated, feeling of loss leading to melancholia, Jed Esty emphasizes how decolonization could make space for a recuperative project that undertook “a basic repair or reintegration of English culture itself.”Footnote 112 As the empire waned and English culture “became minor,” Esty contends, English modernist writers abandoned the sweeping internationalism of High Modernism for an extended rumination on the particularities of English (as opposed to British) culture. Paralleling this literary process was a broad “repatriation” of imperial anthropology to the metropole, exemplified by Margaret Mead's studies of British and American culture and the Mass Observation project's investigations into the everyday life of the English working classes.Footnote 113

Gazzard's transition from colonial to postcolonial architect also underwent an inward turn. In the decade separating Gazzard's work in Jinja and his arrival at Killingworth, a decade in which Britain's African colonies rapidly peeled away, he eschewed his initial focus on replicating western—and, by implication, normative—new-town forms and instead valorized the specificities of place. Each place, according to Gazzard, was circumscribed by unique historical, mythical, and spiritual forces that the urban designer must divine and channel into the cityscape. Paradoxically, Gazzard's experience as a self-described designer of “multi-racial new towns” in Uganda prompted a concern with the local and particular rather than the international and universal. His time working in the empire instilled in him the belief that urban design could only be successful if it tapped into the spiritual and psychological needs of its users. Just as Bedouins identified a place by the taste of its water, Gazzard argued, town planners had to “see places as an organic cycle of change and renewal, and not as the frozen assets of an almighty master plan because in the hearts and minds of men there is always a plan of one kind or another. The essence of the creative decision is the action which translates those plans into reality.” Regretting his early attempts to import English ideas to a Ugandan context, Gazzard saw his work in Killingworth as an endeavor in “place-making”—in connecting his “body, mind, and spirit” with the Northumbrian people, landscape, and culture to transform abstract “space” into a solid, living, “place.”Footnote 114

This phenomenological turn in Gazzard's thought mirrors a broader reaction against high modernism in transatlantic urban design, exemplified by thinkers like Kevin Lynch, Jane Jacobs, Ian Nairn, Gordon Cullen, and William H. Whyte.Footnote 115 Gazzard's return to Britain from Uganda played out against this broader intellectual ferment, and it is hard to disentangle the influence of these western debates from his direct colonial experience.Footnote 116 In his view, though, there was an unbroken chain linking his career in Jinja to his work in Killingworth; he intended to write individual monographs on both places and “then perhaps to link them in a narrative style publication,” but of these only a rough manuscript on Jinja ever materialized.Footnote 117

When Uganda emerged from civil war in 1979, Gazzard, then a professor of geography at Durham University, persistently lobbied the British Overseas Development Administration for funding to volunteer in rebuilding the nation's civil-war-ravaged cities. “It would give me great pleasure,” he wrote, “to be able to renew my association with Uganda, where my children were born and for which my wife and I retain such happy memories.”Footnote 118 These efforts were rebuffed, but in a sense Gazzard's association with Uganda had never ruptured. From his musings on local spatial symbolism to the personnel of his design team at Killingworth, the colonial circuit animating Gazzard's work never fully closed until the wrecking balls pulverized his concrete citadel.