1. Introduction

In many European countries, semi-autonomous agencies have been created in health policy to safeguard general public interests. In executing their tasks, these agencies need to take into account the wishes of their stakeholders while also preventing being captured by their partial interests (Helderman et al., Reference Helderman, Bevan and France2012). Due to scarcity of financial resources and healthcare personnel, agencies in many countries are preoccupied with the difficult task of safeguarding ‘the public interest’ of future accessibility of healthcare for all citizens. The issue of scarcity threatens the willingness of people with different health risks and different incomes to pay for one another's healthcare consumption through insurance. As this principle of solidarity is fundamental to most healthcare systems, this issue is highly pressing (Enzing et al., Reference Enzing, Knies, Boer and Brouwer2021; Van de Sande, Reference Van de Sande2023).

Semi-autonomous agencies across European countries have different tasks relating to this societal challenge. These agencies were created from the 1980s onwards because they were expected to be better at ensuring adequate public service delivery, developing technical expertise, and being innovative and transparent than central government ministries. This is because ministries are likely to adapt their vision based on political influences while agencies can develop a long-term vision due to their distance from politics (Overman, Reference Overman2016). A relevant example for which governments often rely on agencies is health technology assessment (HTA) which entails assessing and appraising newly developed expensive treatments for funding or reimbursement decisions (Enzing et al., Reference Enzing, Knies, Boer and Brouwer2021). Agencies also commonly execute regulatory tasks in order to safeguard public interests which can conflict with the interests of private or semi-public parties operating within healthcare systems. Examples of these are supervision of the quality and safety of healthcare services and managing the preconditions of competition within the market (Helderman et al., Reference Helderman, Bevan and France2012). These two types of tasks of critically appraising health technologies and regulating quality can be conflicting, particularly when delegated to a single agency (Algemene Rekenkamer, Reference Rekenkamer2020).

In addressing this complex issue of scarcity, agencies need to relate to a diversity of actors such as their parent ministry, overseers, advisory boards, and parties of societal stakeholders (Van de Sande et al., Reference Van de Sande, de Graaff, Delnoij and de Bont2022). The conflicting expectations of the agency between and even within the organisations of all these actors further complicate agencies' role definition (Aleksova and Schillemans, Reference Aleksovska and Schillemans2022). Empirical research on regulatory agencies in healthcare, for example, shows the difficulty for agencies to make fair judgements. In doing so, they continuously need to balance reliance on enforcement of predefined rules and the use of interpretation and discretionary room (Rutz et al., Reference Rutz, Mathew, Robben and de Bont2017). In addition, Baldwin and Black (Reference Baldwin and Black2008) state that resources of regulators are often scarce, objectives of regulation can be unclear and legal powers can be limited. Also, regulatory functions are often divided among many different organisations that need to coordinate their activities.

Despite the important and timely role of semi-autonomous agencies in healthcare systems, research on what various actors from within and outside these agencies expect from them is limited. In public administration literature, the roles and tasks of single agencies are often perceived as relatively clear and stable. This is for example illustrated by the large amount of studies that compares the structural design or conduct of multiple agencies (Overman, Reference Overman2016; De Boer, Reference De Boer2022; Leidorf-Tida, Reference Leidorf-Tidå2022). In the field of sociology, qualitative case-study research on single agencies in healthcare does show relevant insights on the everyday concerns and controversies within these agencies. These studies, however, often focus primarily on single tasks, issues, or projects of these agencies rather than on providing an overview of all relevant (conflicting) expectations of an agency as a whole, often imbued with diverse tasks and responsibilities (Rutz et al., Reference Rutz, Mathew, Robben and de Bont2017; Kok et al., Reference Kok, Wallenburg, Leistikow and Bal2020; Van de Sande et al., Reference Van de Sande, de Graaff, Delnoij and de Bont2022). Identifying distinct viewpoints on the role of a single agency enables showing the complexity and controversy around an agency's work.

Our aim in this paper was therefore to identify different viewpoints, among internal and external actors, on the role of the National Health Care Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland, ZiN, hereafter ‘the Institute’) in the Dutch healthcare system. This is the Dutch HTA agency in charge of advising on issues of (financial) sustainability, the value of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions and quality of care, and therefore expected to address scarcity. We used a mixed-method approach called q-methodology to study this. This method enables thorough analysis of attitudes towards a complex and controversial issue (Cross, Reference Cross2005). The method is often used in research on health, wellbeing, and health policy to identify and explain distinct perspectives on a controversial issue (van Exel and De Graaf, Reference Van Exel and De Graaf2005; van Exel et al., Reference Van Exel, de Graaf and Brouwer2007; Daniels et al., Reference Daniels, Williams, Bryan, Mitton and Robinson2018; Hackert et al., Reference Hackert, Brouwer, Hoefman and van Exel2019; Kostenzer et al., Reference Kostenzer, Bos, de Bont and van Exel2021). First, we will discuss theory on conflicting expectations of agencies and on the risk of regulatory capture. Second, we will sketch the controversy regarding the role of the Institute. Third, we will elaborate upon how we conducted our q-study. Fourth, we explore the three viewpoints in our results section. Finally, we will share our conclusions and discuss the relevance of our findings.

2. Conflicting expectations of semi-autonomous agencies

Agencies operate in complex webs of relations with external stakeholders, having different expectations of their conduct. Empirical research shows that, in their work, agencies need to deal with both a large variety of actors and with their often conflicting demands (Koppel, Reference Koppel2005; Schillemans, Reference Schillemans2011; Aleksova and Schillemans, Reference Aleksovska and Schillemans2022). The relations between agencies and their regulatees and parent ministries are particularly complex. Although agencies are often created to be restricting (semi)private organisations and prevent market failures, these stakeholders or regulatees often also exercise considerable influence on agencies themselves. In this case, agencies can be subjected to ‘regulatory capture’ that can be defined as ‘a process by which regulation is consistently or repeatedly directed away from the public interest and towards the interests of the regulated industry by the intent and action of the industry itself’ (Kwak, Reference Kwak, Carpenter and Moss2013: 73). In other words, agencies can meet the wishes of private parties they are supposed to regulate and thereby make decisions that would not be supported by an informed public (Kwak, Reference Kwak, Carpenter and Moss2013). Traditionally, regulatory capture was understood as agencies being driven by self-interest and seeking to maximise their power and resources by using their authority to help private parties pursue their own interests (Levine and Forrence, Reference Levine and Forrence1990). Nowadays, the concept of regulatory capture has expanded and is seen as more complex. Agencies are no longer assumed to be self-interested. In practice, agencies often protect what are perceived as ‘general public interests’. For example, the Institute is created to safeguard current and future accessibility of healthcare for all citizens. Therefore, it sometimes takes decisions that are contested by some stakeholders like advising the minister not to publicly fund highly expensive treatments with limited proven effects on health (Helderman et al., Reference Helderman, De Kruijf, Verhey and Thiel2014). Nevertheless, forms of private influence often play an important role. Interest groups can for example also influence how regulators think about issues they need to solve with their tasks and how they subsequently act, which is called ‘cultural capture’ (Kwak, Reference Kwak, Carpenter and Moss2013).

Therefore, using the expertise and perspectives of regulatees in decision-making while also preventing being intentionally induced by them to identify with their interests requires delicate balancing. Agencies therefore use several solutions such as tripartism and reflexive regulation. Tripartism entails formally involving non-governmental organisations as third parties in negotiations (Ayres and Braithwaite, Reference Ayres and Braithwaite1992). By involving additional parties with different interests that represent contrarian viewpoints, regulators are forced to justify their own positions and use evidence and reason which could reduce unconscious biases and influence of narrow interests (Kwak, Reference Kwak, Carpenter and Moss2013). Similarly, concepts such as responsive (Ayres and Braithwaite, Reference Ayres and Braithwaite1992; Perez, Reference Perez2011) and reflexive regulation (Rutz et al., Reference Rutz, Mathew, Robben and de Bont2017) prescribe a new model of regulation that is not based on enforced compliance and predefined criteria that define regulation. Instead, agencies gather a large variation of experiences, perspectives, and expertise of different organisations while remaining open to multiple problem definitions. Within the health domain, this enables agencies to reflexively use regulatory frameworks to address normative uncertainty and the sector-, organisation-, and jurisdiction-transcending nature of issues such as scarcity (Rutz et al., Reference Rutz, Mathew, Robben and de Bont2017).

Besides the relationship with their regulatees, agencies also have to take into account the expectations of their parent ministry. Despite their semi-independent positions, agencies are often influenced by a ministry which provides it with authority and resources and is ultimately responsible for its conduct (Koop, Reference Koop2014). For these reasons, agencies themselves can be inclined to align their interests with the interests of their parent ministry or department (Dicke, Reference Dicke2002; Schillemans and Bjurstrøm, Reference Schillemans and Bjurstrøm2020). These ministries in turn can be inclined to steer agency behaviour in a preferred direction, particularly when it concerns salient issues (Pollitt, Reference Pollitt2005). On the contrary, saliency can also be an incentive for a ministry to increase agency autonomy because it provides opportunities for blame shifting (Elgie, Reference Elgie2006). Complex technical issues requiring expertise of agency employees may result in less political interest (Maggetti and Papadopoulos, Reference Maggetti and Papadopoulos2018). Also, when agencies are needed to build a trusting relation with stakeholders, less political involvement is more likely (Helderman et al., Reference Helderman, De Kruijf, Verhey and Thiel2014).

3. The Dutch National Health Care Institute

The Dutch National Health Care Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland, ZiN) is the subject of this study. The societal purpose of this agency is to promote the quality, affordability, and accessibility of healthcare for all Dutch citizens. In doing so, its core legal tasks are its package management task and its quality task (ZiN and NZa, Reference Eriksen2020). The first task entails the management of the basic benefit package of publicly funded healthcare. The package contains all types of care for which all citizens are mandatory insured. Based on HTA, including analysis of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, the Institute advises the minister on taking out treatments, only reimbursing a treatment under certain conditions, or preliminarily adding a treatment that has not been proven effective yet. In case of disputes or unclarities, health insurers, providers, and patient organisations may also ask the Institute to decide on whether a certain type of care meets the legal criteria required for reimbursement. The second task holds that the Institute improves quality of care and makes this quality transparent through stimulating societal interest parties to develop quality standards like clinical guidelines. These parties are associations representing patients, healthcare providers (both professional disciplines and healthcare organisations), and the association of insurance companies. The agency possesses several legal instruments to regulate this process. Although the agency operates largely autonomous, the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport is politically responsible for its conduct (Van de Sande, Reference Van de Sande2023).

4. Controversy on the role of the Dutch National Health Care Institute

The Institute provides an interesting case to examine conflicting expectations of a single agency since the definition of its role in the Dutch healthcare system is a contested issue. Although the Institute has a clear societal purpose of safeguarding quality, accessibility, and affordability of healthcare and political and societal expectations of its impact are high, opinions on how the agency should realise this are diverging. One issue is at the core of this controversy. The relation between the Institute's reimbursement and quality tasks has always been complicated. The Institute's predecessor, the Health Care Insurance Board, was primarily responsible for advising the minister about the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of publicly funded care, and for funding health insurers using risk equalisation. In 2014, five other organisations focusing on healthcare quality regulation were added to the organisation which constitute the Institute in its current form. The newly created Institute became also responsible for stimulating interest organisations of health insurers, healthcare providers, and patients to develop legally binding quality standards. In the agency's institutional design, the government deliberately separated these tasks from each other. The quality task was created so that the Institute, with its ostensible distance from politics, could build a good relationship with these parties. This would help to maintain their trust in policymaking, especially of healthcare professionals, because it would ensure them that cuts in public expenses would not influence the content of quality standards (Helderman et al., Reference Helderman, De Kruijf, Verhey and Thiel2014). Since its development, the strict separation of the quality and reimbursement tasks is experienced as increasingly problematic by its employees. Quality and affordability of care are perceived as highly related. The realisation of norms in quality standards can for example lead to higher public expenditure on healthcare, or sometimes lead to savings. Also, in reimbursement advice of treatments, the quality of these treatments is also considered relevant. However, opinions diverge on whether, to what extent and how the tasks should be integrated.

What further complicates the separation of these two tasks within one agency is that they are both based on expertise derived from different disciplines, respectively health economics; and quality management or organisation science. In package management, the Institute is expected to take decisions based on its expertise while in quality management, it relies on stimulating organisational learning among stakeholders. Arguably as a result, the Institute struggles to take on a strong regulatory role and enforce decisions on field parties. From 2014 until 2020, upon the minister's request, the Institute had to exclude ineffective healthcare treatments from the basic health insurance package through its ‘Meaningful Use programme’.Footnote 1 This is an important aim of the Institute since most new treatments and medicines are automatically included in the basic benefit package. Only for very expensive drugs, the Institute advises the minster based on HTA.Footnote 2 Field parties, however, have their own specific interests to keep treatments in the package. A critical evaluation of the programme by the Netherlands Court of Audit (Algemene Rekenkamer, Reference Rekenkamer2020) states that the Institute was too reluctant to use its regulatory powers to force parties to make changes to quit delivering types of ineffective care. Although much of the Institute's personnel capacity was devoted to the programme, the Court concludes that the programme has not met the expectations that were raised. The Institute subsequently stopped the programme in 2020.

Since 2020, the Institute focuses on a new transitionary movement of Dutch healthcare towards, what is called ‘appropriate care’,Footnote 3 with arguably a partly similar aim. This idea of appropriate care stems from a report published by the Institute and another agency, the Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZa) as a response to a formal request from the Dutch healthcare minister. The agencies define appropriate care as ‘care that is valuable for the health and functioning of the individual, at a reasonable price’ (ZiN and NZa, Reference Eriksen2020: 7). The most recent Coalition Agreement published in 2021 shows that the national Dutch government fully embraced appropriate care as ‘the norm’ (Coalitie, 2021: 34). As so-called basic benefit ‘package manager’, the Institute is given an ambitious role in realising this aim (Van de Sande et al., Reference Van de Sande, de Graaff, Delnoij and de Bont2022). The four principles of appropriate care are formulated as it being value-based, that it is decided upon together with the patient, that it entails the right care in the right place, and that it concerns health rather than illness (ZiN and NZa, Reference Eriksen2020). Following the publication of the report, the Institute and the Authority organised meetings with the field, and the Institute launched an online ad-campaign called ‘The Healthcare of Tomorrow’ with videos that aim to raise public awareness about the scarcity of finances and personnel within the Dutch healthcare system. Despite the high expectations, the implementation of appropriate care is very challenging and heavily criticised because the concept is only broadly defined, and responsibilities in the movement are dispersed among several public, semi-public, and private organisations and partly overlapping. What constitutes ‘appropriate care’ and what role the Institute should take on to realise this is disputed.

5. Materials and methods

The q-study method we use allows us to use both qualitative and quantitative analysis to find qualitative order in the diversity of subjective opinions on the Institute's role in this controversy. This method originates from psychology and is designed to let participants decide what has value and significance based on their own perspective. They do so through ranking heterogeneous statements in a so-called ‘q sort’ which has the form of a pyramid. In this way, respondents are forced to prioritise issues (Watts and Stenner, Reference Watts and Stenner2005). The question we asked our respondents is ‘what do you find important in the Institute's organization-wide agenda-setting? I find it important that the Institute focusses on…’. We used the term organisation-wide agenda-setting to make the question recognisable and concrete for our respondents while enabling a broader reflection on the role and goals of the Institute in the broader Dutch healthcare system.

5.1 Development of the statement set

To represent the large diversity of issues regarding the Institute's role, we based our statement set on a broad array of sources as is common in q-methodology (Akhtar-Danesh et al., Reference Akhtar-Danesh, Baumann and Cordingley2008). We conducted ethnographic research and used policy documents and scientific literature about agencies to build our statements. The first author observed four internal meetings at the Institute in which strategic advisors and managers discussed the composition of a new strategic agenda and wrote field notes. The issues that were raised regarding the Institute's role, tasks, and conduct served as input for the statements. Similarly, we used issues raised in the policy documents, visionary documents, and evaluation reports. We also included general struggles of agencies described in scientific literature such as how they deal with the ministry, regulatees, and other agencies. To check for representativeness of the issues, we grouped the statements among 12 dimensions namely ‘healthcare-related’, ‘citizens’, ‘value for patients and citizens’, ‘societal impact’, ‘mandate’, ‘relation with others’, ‘tasks’, ‘sustainability healthcare’, ‘appropriate care’, ‘term’, ‘legitimacy’, and ‘internal capacity’. Initially, we formulated 59 statements. After several discussions within the research team, of which one (DD) is intimately acquainted with the Institute, we removed redundant statements and reformulated unclear ones to end up with 39 statements. In March 2022, the first author piloted the q-study among four Institute employees to see if issues were missing and to check for clarity of the statements. Since these employees have extensive work experience in the agency but also work(ed) in other organisations on Dutch health policy, they possess much knowledge about key issues experienced by actors within and outside the organisation. Based on the pilots, we further refined the statement set through adding two new statements and removing seven others. We ended up with 34 statements. The set of opinion statements can be found in Table 3.

5.2 Selection of respondents

The first author conducted 41 q-interviews between April and August 2022. Respondents were selected through purposive sampling with the aim of including a representative collection of stakeholders' viewpoints on the role of the Institute. We included employees, called ‘advisors’ of the Institute from different layers of the organisation (board of directors, department heads, managers, and advisors). Also, we selected employees from different departments, working on different tasks of the Institute (quality tasks, package advice, information management, and risk equalisation). We also included employees from the communication department and from the research and development department. In addition, we recruited respondents working at actors the Institute cooperates with. These categories were: its three advisory committees, peer regulatory agencies, the parties (organisations for patients, professionals, healthcare providers, and insurance companies), the ministry, evaluators, and prominent experts in the health policy domain. We made use of the professional network of the authors within the Institute and within the health policy domain to identify relevant participants and recruit them for our study. All respondents received an email introducing the purpose of our q-study and the set-up of the interview which included an informed-consent form. Table 1 provides an overview of our study sample.

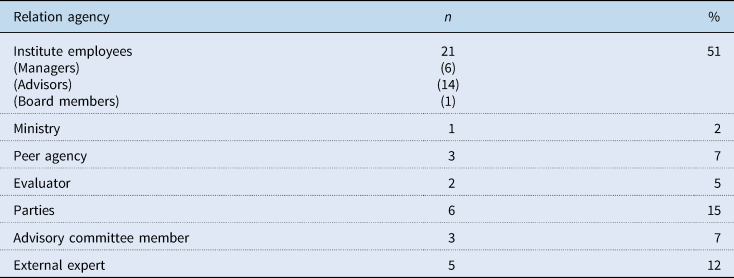

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample (N = 41)

5.3 Data collection

The 41 q-sorts were collected by the first author in an interview-setting. For 28 of the interviews, we used the online programme Miro in which respondents could sort the statements. The author used the communication programmes Microsoft Teams and Webex to provide instructions and conduct the interview afterwards. The other 13 interviews were conducted physically at the offices of our respondents. In that case, respondents were asked to place the statements printed on cards on the grid printed on a cardboard. The sorting of the statements consisted of two steps. First, respondents were asked to divide all statements in three piles, a pile for ‘unimportant’, a pile for ‘important’, and a pile for ‘do not know’. Afterwards, the respondents placed the cards on a nine-column grid ranging from 1 (‘least important’) to 9 (‘most important’). They started by placing the most important statements on the right side of the pyramid, followed by the least important ones on the left side, and the cards from the third pile in the remaining boxes in the middle. If they wished to do so, respondents could make final changes afterwards. The sorting of the statements lasted for approximately 20 minutes. The final interview afterwards in which respondents motivated their sorting lasted between 30 minutes and 1 hour. To meet the preferences of our respondents, respondents of eight organisations participated as a duo. These interviews lasted usually one-and-a-half hour including the sorting, instead of 1 hour for single participants. In that case, the duo's were asked to reach consensus on their sorting. Both the thinking-out-loud or discussing during the sorting and the interview afterwards were recorded and transcribed verbatim. A screenshot or photograph was taken of their grid. Figure 1 shows the structure of our sorting grid.

Figure 1. Sorting grid.

5.4 Data analysis

For the identification of patterns in the sorting of our statements by all participants, the first author conducted a by-person factor analysis using the programme PQMethod (Schmolck and Atkinson, Reference Schmolck and Atkinson2018). We imported our statement set and the structure of our sorting grid, which was rescaled as ranging from −4 to +4 instead of 1 to 9. We subsequently imported the cell values for all the 41 grids. The programme calculated correlations between the rankings of statements by participants and clustered participants with similar correlated rankings in factors. The factors can be understood as diverse perspectives on the role of the Institute. We conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) to extract the factors which are ordered by the relative variance in the rankings they explain. We used the statistical criteria proposed by Watts and Stenner (Reference Watts and Stenner2012) to identify the relevant factors. These state that a factor's eigenvalue (a factor's weight) must be larger than 1 and that it thus explains more of the total variance than the ranking of a single participant, and that at least two respondents load significantly on the factor (with a p-value <0.05). Thorough analysis of the loadings of individual participants on single statements and on the differences in statement-loadings between the factors enabled us to indicate the meaning and relevance of the factor. We also used our qualitative data to further determine the selection of relevant factors which left us with three factors. This data was abductively coded using ATLAS.ti. The statements were used as codes for the data. The PCA resulted in five factors that met the statistical criteria and thus served as a starting point for the analysis. Analysis of the interview transcripts of the two respondents loading significantly on the two factors with the lowest eigenvalue made clear that both were not representing clear and meaningful factors (viewpoints). The interviews were thus crucial to extract three relevant factors from the results of the PCA. The three viewpoints were subsequently also used as codes to further analyse the qualitative data and to further explore the three viewpoints.

6. Results: three distinct viewpoints on the desired role of the Institute

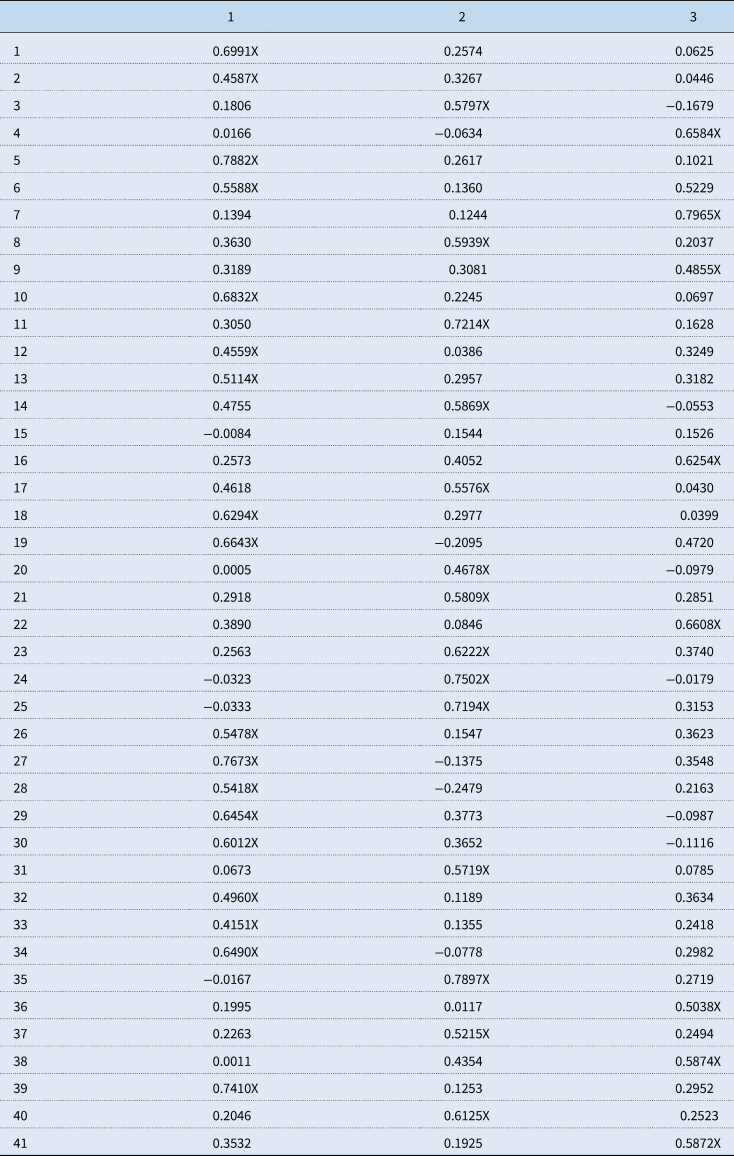

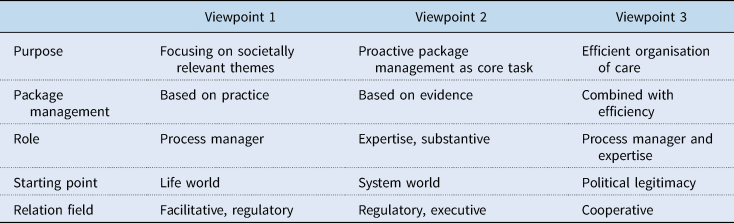

Our mixed-method approach resulted in three factors that can be interpreted as distinct viewpoints on what the Institute should focus on. Table 2 shows the loadings of participants on all three factors. The number of respondents that load significantly on the factors are 18 respondents for factor 1, 14 respondents for factor 2, and 8 respondents for factor 3. One of our respondents (number 15) has no significant loading for any of the factors. None of our respondents load significantly on more than one factor. Our factors explain 50 percent of the total variance in our data (factor 1: 20 percent, factor 2: 17 percent, factor 3: 13 percent). The correlations between our factors range from 0.46 to 0.56 and can thus be considered moderate. All respondents who load significantly on the factors are loading positively on the factors. In the description of our three viewpoints, we illustrate them using quotes from participants with high loadings on the viewpoint. We will also focus on distinguishing and consensus statements to compare the viewpoints (Table 3).

Table 2. Factor loadings

Table 3. Key aspects of the role of the Institute according to the viewpoints

6.1 Viewpoint 1: focusing on societally relevant themes

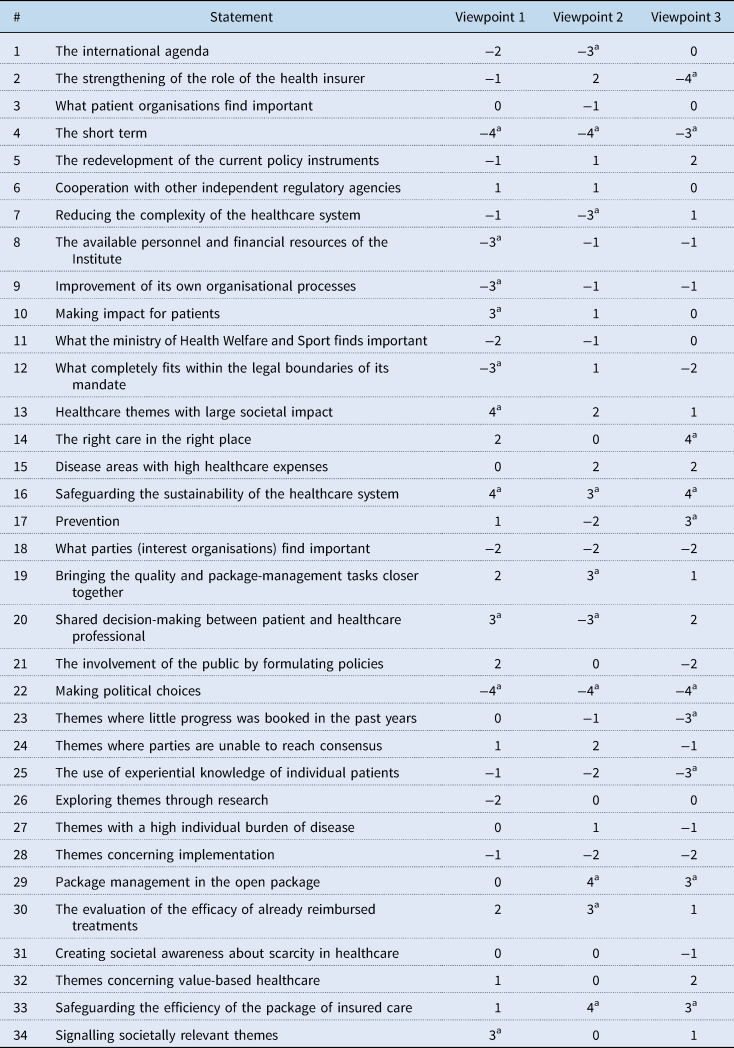

(#13, +4; #34, +3; #20, +3; #21, +2; #10, +3)

This first viewpoint is characterised by the argument that pursuing positive societal impact should be the core aim of the Institute. The statements ‘healthcare themes with large societal impact’ (13) and ‘signalling societally relevant themes’ (34) score relatively high compared to the other two viewpoints. Also, this viewpoint underscores the everyday reality of the practices of healthcare professionals and the life world of individual patients and citizens. Respondents who pre-dominantly argue in this line find that the Institute's conduct should fit the needs of individuals and that it should actively signal problems citizens are facing. Therefore, they find a focus on stimulating ‘shared decision-making between patient and healthcare professionals’ (20), ‘the involvement of the public in formulating policies’ (21), and ‘making impact for patients’ (10) important issues for the Institute to focus on (Table 4).

You should not only look at RCT's [randomized clinical trials] but at practical information as well. You [the Institute] can also evaluate by saying ‘this is care that was automatically [without an explicit judgement of the Institute] included in the basic benefit package and that parties discuss with each other afterwards’. Healthcare professionals themselves can mutually discuss whether something works, and that the treatment is not delivered anymore when its effect is insufficient. The Institute should stimulate this, rather than setting up another RCT, that will remain unreal (viewpoint 1, resp. #5).

For me appropriate care is the card we placed on top of row 9 [making impact for patients]. Appropriate care is now commonly seen as effective care [by the ministry and Institute], but my question then is ‘what do you see as effective, who determines what is effective and how do you measure that?’ Effectiveness is about contracting [insurers contracting providers] and package management, about all the ‘blue’ themes, while what patients and clients find important based on their values and how they want to structure their lives is disregarded (viewpoint 1. resp. #34).

The viewpoint is also characterised by a high level of trust in representative parties and of individual professionals. The content of quality standards is perceived to be the domain of the parties. The Institute's role is regarded as facilitative and regulatory when necessary.

I think that we have a facilitating role, but we are also in the position to undertake action when necessary. When parties cannot reach an agreement, it can help when we cut the cord or mediate on certain issues. (…) But we should leave the responsibility where it belongs, at the parties. We [the Institute] should not take things over (viewpoint 1, resp. #18).

Table 4. Average factor scores per statement for the three viewpoints

a Distinguishing statements that are characterising for a factor and score −4, −3, +3, or +4.

(#11, −2; #12, −3; #26, −2)

This viewpoint can also be regarded as rather progressive when it comes to the re-development of the Institute's role and tasks. The statement ‘what completely fits within the legal boundaries of its mandate’ (12) loads strongly negative compared to the other two viewpoints and is thus considered as less or unimportant for the Institute to focus on. This fits the argument of aligning with citizens need rather than strictly adhering to boundaries of legislation. ‘Exploring themes through research’ (26) is considered relatively unimportant since the importance of experiences from healthcare practice is considered just as valuable as evidence derived from RCTs and systematic reviews used in HTA (Table 4).

6.2 Viewpoint 2: proactively managing the basic benefit package

(#29, +4; #30, +3; #33, +4; #19, +3)

The second viewpoint stresses that the Institute should stick to its core task as package manager but that it should take on a more proactive and regulatory role and dare to make bold choices in doing so. ‘Package management in the open package’ (29) is considered an important priority for the Institute. Similar statements that score relatively high in this viewpoint are ‘the evaluation of the efficacy of already reimbursed treatments’ (30), and ‘safeguarding the efficiency of the package of insured care’ (33). This preference is illustrated by the quote below in which the respondent pleas for proactively taking decisions based on continuous evaluation of the effectiveness of reimbursed care.

I would say that the Institute should focus on executing its legal task, namely ensuring a package of good insured care. What they thus should do is systematically assessing the scientific basis of delivered care and drawing conclusions like ‘this is sufficiently substantiated and can be continued; this is insufficiently substantiated and should be excluded from the package, and this is care for which the efficacy is unknown and requires further research’ (viewpoint 2, resp. #35).

In this viewpoint, the role of clinical and economic research in terms of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and HTA are thus perceived as important. ‘Bringing together the Institute's package management and quality tasks’ is also deemed important (19). Respondents argue that the content of quality standards should also be assessed based on the financial costs. Furthermore, they find that quality and affordability are highly related.

Actually, when quality was added to us [the predecessor organization of the Institute] in 2014, then we had to very strictly keep that [quality and affordability] separated. Now, everyone sees that this is just very undesirable and also impossible because money and quality go hand in hand. And you see that when something is insured it is of good quality because it is effective. So, in that sense there are many parallels. Care is also often effective under certain prerequisites such as volume norms that professionals need to meet in order to reach good outcomes (viewpoint 2, resp. #17).

(#17, −2; #20, −3; #7, −3; #1, −3)

The value of the technical scientific expertise of the Institute is stressed by respondents included in this viewpoint. Respondents argue that the Institute's current focus with its appropriate care programme is too broad. ‘Prevention’ (17), ‘shared decision-making’ (20), and ‘reducing the complexity of the healthcare system’ (7) are seen as important things, but not for the Institute to take up as its tasks. While a focus on prevention can decrease healthcare expenses on the long term, this is associated with issues as lifestyle, public health, decreasing poverty, and job security which are not directly the domain of the Institute. Respondents find shared decision-making something that is between the individual healthcare professional and individual patient to arrange and for other organisations than the Institute to stimulate. The complexity of the healthcare system is seen as a systemic issue for which the ministry is responsible. Furthermore, respondents find that the Institute should be bolder in making choices rather than facilitating processes.

I think the Institute should focus on further explaining and supporting health insurers in what is effective and thus insured care. And it should communicate and publish all the expertise they have to do so. They are just very competent; they have much knowledge and are very important. Therefore, I think they should not be too reluctant to take on that role. And I think they should take on much less the role of guiding processes between field parties. I would find that almost a shame because based on thorough research the Institute can do more in deciding this is insured or non-insured care (viewpoint 2, resp. #24).

‘The international agenda’ (1) is perceived as unimportant because of the specific peculiarities of the Dutch healthcare system. On the one hand, this viewpoint could be seen as rather conservative compared to the first viewpoint because of the focus on the Institute's traditional core tasks. On the other hand, respondents who load significantly on this viewpoint argue that the Institute should take on a more proactive role.

6.3 Viewpoint 3: realising an efficient organisation of care

(#29, +3; #33, +3; #32, +2; #17, +3; #20, +2; #14, +4)

The third viewpoint is similar to the second one as it also shows a preference for proactive package management to improve the financial sustainability of the Dutch healthcare system. Statements that are loading high on the factor are ‘package management in the open package’ (29), ‘safeguarding the efficiency of the package of insured care’ (33), and ‘themes concerning value-based healthcare’ (32). However, respondents see the principles of appropriate care, which also concern, efficient organisation of care, as important prerequisites for the Institute to realise. Unlike the second viewpoint, this viewpoint is in favour of a focus on themes which are partly outside the scope of the Institute such as ‘prevention’ (17). Another example of this is ‘shared decision-making between patient and healthcare professional’ (20). The fourth principle of appropriate care ‘the right care in the right place’ (14) is found most important as illustrated by the quotes below.

For me it means the right care in the right place with the right information. That is also how we apply it within the Institute. For me that is super important because I think that if we together organize information services better, we can better realise appropriate care. Information services for shared decision-making, for care processes, for cooperation within the care chain, and so on (viewpoint 3, resp. #7).

R1: [about ‘the right care in the right place’]. Because eventually everyone profits if this would actually happen. It is pleasant for the client, the patient, the caregiver, and society because when everyone receives the right care in the right place it will also be at the lowest costs. So, if that would really work it would contribute to all three goals of our healthcare system [quality, affordability, and accessibility].

R2: because scarce resources and skills of personnel are then optimally used (viewpoint 3, resp. #41).

(#2, −4; #12, −2; #21, −2; #23, −3; #25, −3)

The ‘strengthening of the role of the health insurer’ (2) is marked important by respondents in the second viewpoint. They argue that by providing clarity about the effectiveness of treatments that are already included in the package, insurers know what to (not) reimburse. Respondents in the third viewpoint, however, find it one of the least important statements as the quote below illustrates.

I found it a difficult one. I thought ‘what should we do in the strengthening of the role of the health insurer?’ I think they already have a very strong position in our healthcare system so is it necessary to further strengthen this? (viewpoint 3, resp. #22).

The statement ‘what completely fits within the legal boundaries of its mandate’ (12) scores mediate compared to the other two viewpoints, which shows that this viewpoint takes on a broader view on the Institute's role than viewpoint 2 but narrower than viewpoint 1. Compared to viewpoints 1 and 2, respondents are however more conservative in involving the public as illustrated by their low scores on the statements: ‘the involvement of the public in formulating policies’ (21) and ‘the use of experiential knowledge of individual patients’ (25). Since ‘themes where little progress was booked in the past years’ (23) also scores low, the viewpoint can also be seen as rather pragmatic. The legitimacy gained from the Institute's legal tasks and the appropriate care programme embraced by the government is seen as important for the Institute in determining its focus.

6.4 Points of consensus between the viewpoints

(#16, 4, 3, 4; #4, −4, −4, −3; #6, 1, 1, 0; #18, −2, −2, −2; #22, −4, −4, −4; #31, 0, 0, −1)

Despite the controversies between the viewpoints, respondents in all three viewpoints largely agree on the relative importance or unimportance of six consensus statements. ‘Safeguarding the sustainability of the healthcare system' (16) was perceived as important by respondents of all three viewpoints and was commonly placed as most important in the pyramid. The urgency of this main challenge of the Dutch healthcare system and the core role of the Institute in dealing with this challenge was recognised by all respondents.

That is our core business according to me, because we are about good, affordable and accessible care in the Netherlands, that is the reason of our existence that is where we should focus our work on. The accessibility and affordability seem to be enormously under pressure at the moment. That is really an urgent problem, also for the future, it is not something we are easily finished with. If the costs are rising too much you can hardly defend solidarity among people. I fear that the solidarity, actually the anchor of our healthcare system is put under pressure (#resp. 1).

'The short term' (4) is generally experienced as unimportant. Respondents argue that the Institute deals with complex problems for which a longer time frame is necessary. In contrast to politicians, the Institute can use its long-term expertise, relations within the healthcare system, and vision to deal with these problems.

[about short term] You should not go for the delusion of the day. You should really keep an eye on the long term and the sustainability of the system (#resp. 13).

‘What the ministry of Health Welfare, and Sport finds important’ (11) is generally also considered less important. According to some respondents, the Institute accepts too many new projects delegated by the ministry that do not really fit its core tasks, and that, since it is a semi-autonomous agency, it should follow its own path more. 'What the parties or, in other words, the representative organisations of healthcare providers, healthcare professionals, insurance companies, and patients find important' (18) is usually marked as unimportant for the Institute. This is on the one hand remarkable since these parties are the core stakeholders and regulatees of the Institute with whom it often sits at the table. On the other hand, it fits the wish of a stricter position of the Institute towards the parties in all three viewpoints.

Umbrella organizations [interest organizations/parties], I find the patient organizations very important clubs. But still, I find that the most important task of the Institute is to cut cords. That role of cutting cords, this is effective, this is not effective, this is worth the money, and this is not worth the money according to the criteria that have been set for this by politicians. Patient- and other umbrella organizations always have all sorts of interests in this. With no doubt, they will try to convince the Institute that the type of care that they deliver or that they use should fall under one side of the dividing line. Therefore, it is extremely dangerous for a regulator to follow the will of the field too much. You should listen to it, but you should also dare to not do too much with it (#resp. 8).

'Coordination with other regulatory agencies' (6) was seen as moderately important by respondents in the three viewpoints. The statement 'taking political decisions' (22) was commonly placed utmost left. Political choices were seen as something for politicians and not for the Institute, although a few respondents regarded the work of the Institute as inherently political in a certain way. Some respondents argue for a different role of the Institute and propose a system in which the Institute no longer advices the minister about the inclusion of expensive new drugs in the basic benefit package of insured care but takes the decision on its own. This is similar to the role of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the HTA agency in the UK. In this case, politicians will determine how much public money a quality-adjusted life year is worth. The Institute will take a decision based on technical HTA procedures. The quotes below show the different explanations of respondents for ascribing unimportance to the statement.

We [the Institute] do not make legislation, we do not design the system, and we do not make political choices (#resp. 23).

Within the current system, the Institute is not in power to make political decisions, it advices the minister to do or do not reimburse things. Of course, eventually there are always normative elements in the model they use. My plea has always been that the Institute should make more political decisions. I think that it would be good if the Institute would get a much larger mandate like NICE has in the UK which means that it does not only advice but that it takes political decisions within frameworks established by the ministry (#resp. 40).

Also, 'creating societal awareness about scarcity in healthcare' (31) was not seen as a task of the Institute but rather as a task of the central government itself, which is remarkable since the Institute invested in an online campaign to raise public awareness about this issue. Many respondents were either not in favour of this campaign or they appreciated the campaign but thought that this is actually the task of the ministry.

Creating awareness, of course that was goal number one with the campaign. But we actually did this because the ministry didn't do it, let's be honest. Because this would have been a logical task for the ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport. (…) I think that we [the Institute] then thought ‘that is where everything starts’. But we are not the only ones in charge of creating awareness. (#resp. 32).

The risk is that politicians do not at all want to tell people that there is scarcity and that choices have to be made. So, the Institute has to be careful that they are not the sender of the unwelcome message because it is not the Institute's fault that there is scarcity. Public opinion can, if you approach it the wrong way, quickly turn into ‘the National health care institute is that club that is there to save money’ (#resp. 8).

The path that the Institute has taken so far which is embodied in its appropriate care programme and its campaign ‘the healthcare of tomorrow’ is thus critiqued by almost all respondents. Although many respondents appreciate the endeavour and think that the programme might lead to changes in the healthcare system in the coming years, others find that it is a political issue and not the Institute's job to do so. According to some respondents, the Institute takes a large risk in taking up this task because it might be blamed by the public opinion for ‘sending the bad message’. They fear that this might be an opportunity for the ministry to shift blame to the Institute and reduce political transaction costs which will affect the Institute's reputation as is shown in the quote above. Internal and external respondents are distributed relatively equally over the three viewpoints. However, people within the Institute working on the quality tasks, patient organisations, and several health policy experts can be placed in viewpoint 1. Insurers, experts in health economics, and people within the Institute working on package management can be placed into viewpoint 2. The third viewpoint is a more diverse group of respondents.

7. Conclusion

Using q-methodology, we aimed to identify different viewpoints on the role of the National Health Care Institute in the Dutch healthcare system. We found three different viewpoints which respectively propose that the Institute focuses on societal relevance, strict package management, and efficient organisation of care. The three viewpoints include respondents of parties, experts, evaluators, the ministry, peer agencies, and the Institute itself. Our paper makes clear that an agency that needs to address complex and controversial issues like scarcity, faces many challenges in dealing with conflicting expectations of stakeholders. It shows that the risks of regulatory capture and navigating between government autonomy and control are key issues for agencies like the Institute. In addition, our q-study shows that these challenges can result in different viewpoints on an agency's role, pulling it in different directions. We argue that this is problematic since it complicates a clear strategy and adequate actions which addressing an issue like scarcity in healthcare requests. Several scholars plea for dynamic and fluid roles of agencies through strategies such as reflexive (Rutz et al., Reference Rutz, Mathew, Robben and de Bont2017) and responsive (Ayres and Braithwaite, Reference Ayres and Braithwaite1992; Perez, Reference Perez2011) regulation in dealing with such complex problems. Although reflexively interacting with stakeholders is important to create societal support, we argue that it can also complicate a clear regulatory role of the agency which is necessary to address such issues.

Therefore, expected overarching goals need to be clearly defined and enforceable to realise changes in healthcare practice, albeit local approaches may differ. The significantly different understandings of and perspectives on the appropriate care programme are problematic in this light. Therefore future research that makes different perspectives explicit is important to ensure that the continuous redefinition of an agency's role has broad-based societal and organisational support. This is particularly relevant when an agency is expected to address a complex and salient issue like scarcity in healthcare, which is a current issue for many health systems across the globe (Enzing et al., Reference Enzing, Knies, Boer and Brouwer2021; Van de Sande, Reference Van de Sande2023). Future research (using q-methodology) can provide further insights into how different policy actors across countries deal with this issue and redefine their roles and relations accordingly.

8. Discussion

All viewpoints stress the important role for the agency in keeping the healthcare system sustainable in the future. Despite certain overlap, opinions on how the Institute should take on this grand challenge differ between the viewpoints on key aspects of its role. These conflicting expectations place the Institute in a challenging position in addressing the current complex problem of scarcity in Dutch healthcare. This issue is not unique for the Institute. Semi-autonomous agencies in many countries need to deal with conflicting expectations of various stakeholders such as their regulatees and their parent ministries. Literature shows that taking their interests into account while also weighing them at a certain moment to come to what are perceived as general public interests is often challenging (Koppel, Reference Koppel2005; Schillemans, Reference Schillemans2011; Aleksova and Schillemans, Reference Aleksovska and Schillemans2022).

The combination of ranking statements followed by interviews in our q-study provides interesting insights on the role orientations of the Institute. It shows that there are different ways to prevent this risk of regulatory capture proposed by the viewpoints. The first viewpoint fits strategies of tripartism and reflexive regulation (Ayres and Braithwaite, Reference Ayres and Braithwaite1992) since it stresses the importance of contextual knowledge through incorporating perspectives from patients and professionals in defining healthcare quality. It proposes only cutting cords when necessary. On the contrary, both the second and third viewpoint propagate that the Institute takes more bold package management decisions against partial interests based on its extensive HTA expertise. In addition, viewpoint 3 also stresses the Institute's role in realising efficient organisation of Dutch healthcare.

Remarkably, we did not find a distinction in viewpoints of respondents from within and outside the Institute. We did however find other similarities. Respondents in viewpoint 2 were mostly working on the topics of package management, HTA, or health economics both within and outside the Institute. This can be explained by actors' tendency to stress their technical expertise in justifying decisions about resource allocation (Busuioc and Lodge, Reference Busuioc and Lodge2017). Viewpoint 1 also consisted both of respondents from within and outside the Institute with a shared interest in topics related to quality management and organisation of care, which fits the Institute's approach in its quality task. These two viewpoints were expected as they align with the two conflicting values quality and affordability of care, on which the Institutes core tasks focus. This indicates that two different perspectives on what constitutes good care, informed by different scientific disciplines, are persistent across Dutch health policy and thereby also influence the Institute. Viewpoint 3 was unexpected and includes a mix of both types of respondents, also exceeding the Institute's boundaries. This possibly indicates a movement towards a more integrated focus on Dutch healthcare and the Institute's role.

The viewpoints all stand critically towards strong involvement of the parent ministry. A common challenge for agencies is to navigate to what extent they can and want to operate autonomously (Dicke, Reference Dicke2002; Elgie, Reference Elgie2006; Koop, Reference Koop2014; Maggetti and Papadopoulos, Reference Maggetti and Papadopoulos2018; Schillemans and Bjurstrøm, Reference Schillemans and Bjurstrøm2020). This relates to the value that respondents see in the Institute's long-term vision in opposition to the ministry's short-term focus. Nevertheless, viewpoint 3 largely aligns with the appropriate care programme, which has been adopted by the ministry. This shows that, despite stressing the Institute's autonomous position, some respondents also align the Institute's role with the wishes of its parent ministry. This kind of cultural capture by ministries is described in stewardship theory, which states that ministerial control can be soft when the goals of the agency and its political principal are aligned (Dicke, Reference Dicke2002; Schillemans and Bjurstrøm, Reference Schillemans and Bjurstrøm2020).

The viewpoints differ significantly on whether they find that the Institute should stay within the boundaries of its formal mandate. While viewpoints 1 and 3 argue for exceeding these boundaries to respectively address societally relevant issues and realise an efficient organisation of healthcare, viewpoint 2 pleas for strictly adhering to them. The two viewpoints touch upon a common issue for agencies. As Baldwin and Black (Reference Baldwin and Black2008) state, regulatory functions are often divided among many different organisations. To address societally relevant issues agencies therefore need to coordinate their activities with each other. The boundaries of an agency's relatively narrowly defined legal tasks can conflict with its broader societal purpose (Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2021). Our findings illustrate in detail this dilemma of staying within these boundaries or exceeding them.

Acknowledgements

We thank all our respondents for sharing their insightful perspectives. Furthermore, we thank our colleagues of the Healthcare Governance section for their valuable feedback during discussions of a draft version of this paper. Finally, we thank Job van Exel and Teyler van Muijden for sharing their knowledge on q-methodology.

Financial support

This work was partly funded by the National Health Care Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland, ZiN) as part of the Research Network HTA.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

The ESHPM Research Ethics Review Committee, Erasmus University Rotterdam. Approval number: ETH2122-0523.

Author note

When this research was conducted, Jolien van de Sande was affiliated with Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management. She is now affiliated with Tilburg University.