Publicly financed health coverage in France is universal. Nevertheless, in 2015, private health insurance accounted for 13.3% of total spending on health (French Ministry of Health, 2016),Footnote 5 one of the highest shares internationally. According to the most recent survey data available, 95% of the population is covered by a complementary health insurance contract that primarily reimburses statutory user charges. Nine out of ten people insured have a private contract while the rest benefit from publicly funded complementary coverage known as Couverture maladie universelle complémentaire (CMUC) due to their low income (Reference Barlet, Beffy and RenaudBarlet, Beffy & Renaud, 2016; based on the 2012 Health, health care and insurance survey). Footnote 6

The chapter begins by describing the basic features of the statutory health insurance system and the dynamics of its regulation, which explain the role that private health insurance has come to play over time.

It then provides an overview of the private health insurance market. Historically, the market has been dominated by non-profit mutual associations known as mutuelles. The final section distinguishes three themes around which public policy towards the private health insurance sector has emerged since the 1990s. First, harmonization of regulation aims to encourage competition and increase transparency in the market. Because of their grounding in the social economy, mutuelles and, to a lesser degree, other non-profit insurers have benefited from specific tax exemptions and other advantages deemed to contradict European Union competition law. Over time, and largely due to pressure from for-profit insurers, regulations have changed to level the competitive playing field and protect activities organized in the “general interest” of solidarity and mutual aid. The second type of regulatory intervention, first introduced in 2000, aims to strengthen equity of access to private health insurance and therefore to health care. The publicly funded CMUC and a more recent voucher scheme for low-income households sought to limit socioeconomic differences in access to private health insurance. Finally, since January 2016, all employers – irrespective of the size of their business – have been required to provide private complementary health insurance to their employees. The third regulatory trend seeks to increase the overall efficiency of the health system by better aligning the incentives of private and public insurers on the one hand, and the providers of care on the other.

Health system context and the role of private health insurance

Universal coverage through statutory health insurance

All legal residents are covered by statutory health insurance, an entitlement of the wider social security system. Set up in 1945, the statutory scheme initially offered coverage based on professional activity and was contingent on contributions. The scheme has always been administered by a number of noncompeting health insurance funds catering to different segments of the labour market. The main fund (Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salarié) currently covers 91% of the population (DSS, 2015). The two other sizeable funds cover self-employed people (Régime Social des travailleurs Indépendants, RSI) and agricultural workers (Mutualité Sociale Agricole). In 2000, the Universal Health Coverage (Couverture Maladie Universelle, CMU) Act changed the public insurance entitlement criterion from professional activity to residence. This allowed a small but growing share of the population, that had previously been excluded from the statutory scheme (and was covered through locally funded schemes), to benefit from the same rights as the rest of the population.Footnote 7 In 2016, this mechanism was generalized and simplified to become the Protection Universelle Maladie and now around 3.8% of the population draw their social health insurance membership from their residency status.Footnote 8 The benefits package was harmonized in 2001. In 1991, the funding of the French social security system (and therefore also of statutory health insurance), which initially relied on payroll contributions, was expanded to include taxes on a wider range of income sources. In 2014, payroll contributions represented around 47% of statutory health insurance revenue and other earmarked taxes represented nearly 50% (DSS, 2015).

Cost sharing and choice of provider

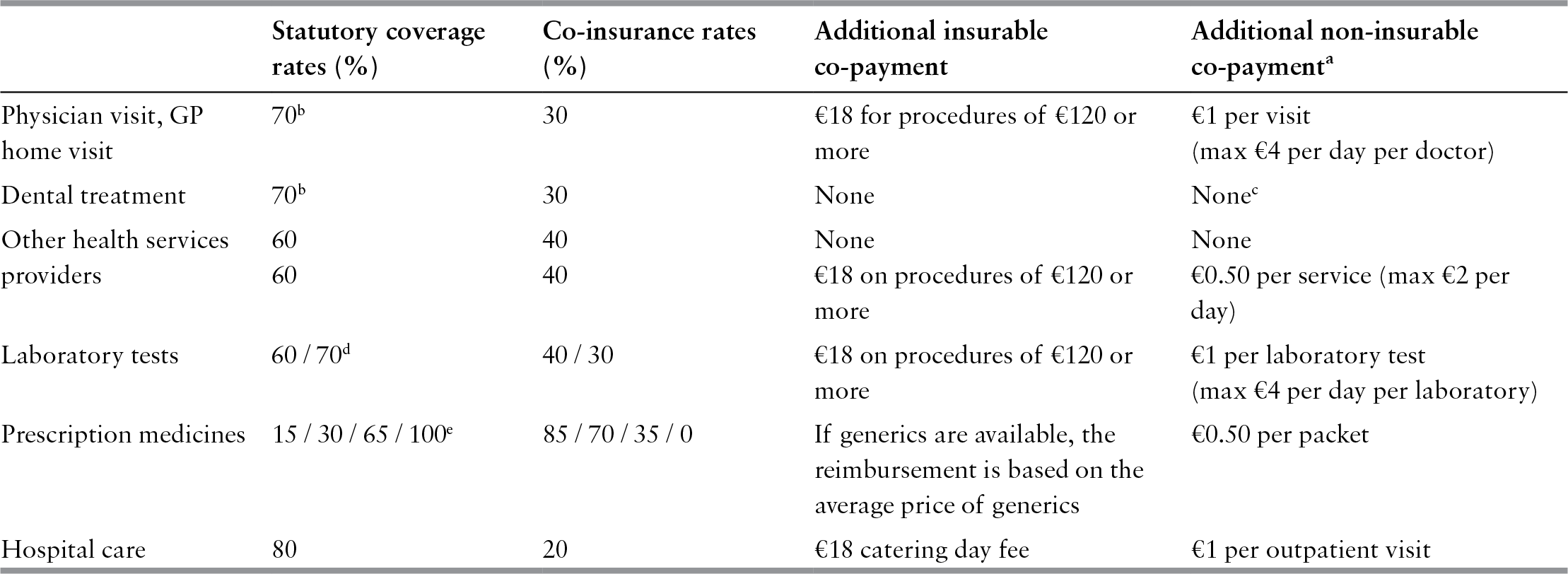

The scope of services covered by the publicly funded benefits package has always been broad in France and the preferred public spending control mechanism has been to limit the depth of public coverage, leaving the patient to pay a share of the cost (see Table 5.1). Since 2005, the government has introduced a range of additional flat-rate co-payments.Footnote 9 Another source of out-of-pocket payments is the difference between the actual market price of a service and the official tariff based on the statutory health insurance reimbursement rate (Reference Couffinhal and ParisCouffinhal & Paris, 2001). This difference is particularly high for products such as dental prostheses and eyewear, and for the services of some physicians (“Sector 2” physicians), mainly specialists, who are allowed to charge more than the official tariff. In order to balance extra-billing, additional provisions were introduced in the global agreement linking the public health insurance system and physicians’ unions in October 2012. Sector 2 doctors are incentivized to sign a voluntary 3-year “access to health care” contract, which restrains extra-billing practices (Reference ChevreulChevreul et al., 2015). More recently, in December 2015, the National Assembly adopted a government reform (projet de loi de modernisation de notre système de santé), which generalizes the third-party payment to all social health insurance beneficiaries. Third-party payment requires physicians to directly bill social health insurers (and, if they so decide, they can also directly bill complementary health insurers) rather than charging patients at the point of service. The measure, strongly opposed by physicians, was implemented in 2017 for some categories of insured exempted from statutory co-payments and will be extended to the entire population.

Table 5.1 User charges for publicly financed health care in France, 2016

| Statutory coverage rates (%) | Co-insurance rates (%) | Additional insurable co-payment | Additional non-insurable co-paymenta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician visit, GP home visit | 70b | 30 | €18 for procedures of €120 or more |

|

| Dental treatment | 70b | 30 | None | Nonec |

| Other health services providers |

|

|

|

|

| Laboratory tests | 60 / 70d | 40 / 30 | €18 on procedures of €120 or more |

|

| Prescription medicines | 15 / 30 / 65 / 100e | 85 / 70 / 35 / 0 | If generics are available, the reimbursement is based on the average price of generics | €0.50 per packet |

| Hospital care | 80 | 20 | €18 catering day fee | €1 per outpatient visit |

Notes:

a The amount is deducted from public reimbursement and limited to €50 per patient per year.

b Falls to 30% if the patient does not obtain a referral to ambulatory specialist care.

c €1 deductible applies only to dentists, not dental surgeons.

d The rate depends on the type of test and the qualification of the health professional performing the test. The HIV diagnostic test is free of charge.

e Depending on the type of medicine.

Patients have traditionally enjoyed free choice of provider and been able to self-refer to specialists. A 2004 reform introduced a voluntary “preferred primary care provider” gatekeeping system. Patients who comply with gatekeeping retain the same coverage rates as before, whereas those who do not are reimbursed at lower rates (for example, 30% rather than 70% for physician services) and providers are allowed to charge them more than the official tariff (Reference Com-Ruelle, Dourgnon and ParisCom-Ruel, Dourgnon & Paris, 2006).

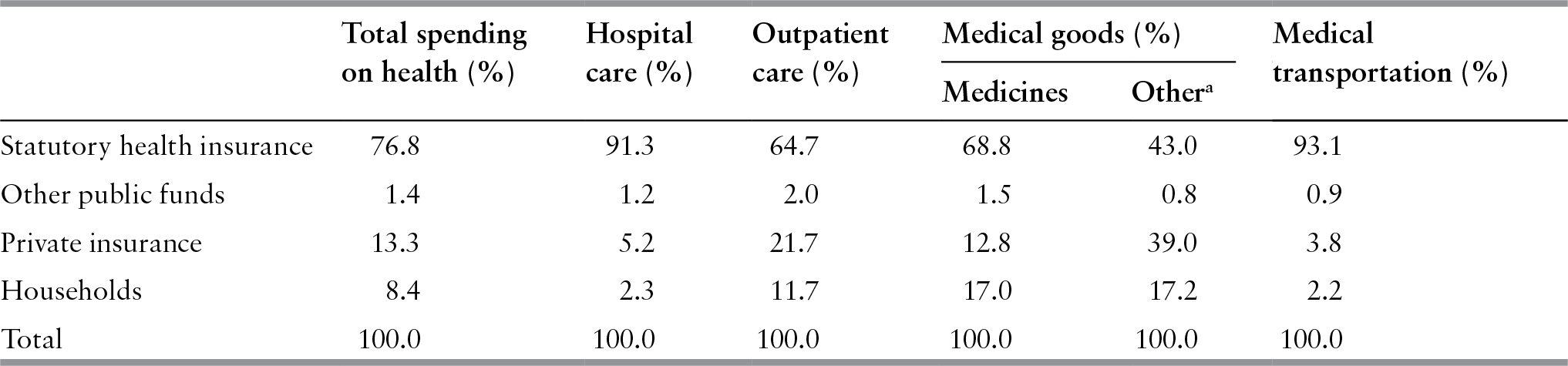

In 2015, statutory health insurance funded 78.2% of total spending on health (see Table 5.2), a share that has remained relatively stable since the mid-1980s (Reference Fenina and GeffroyFenina & Geffroy, 2007; Reference Fenina, Le Garrec and KoubiFenina, Le Garrec & Koubi, 2010; French Ministry of Health, 2016). However, while over 90% of hospital spending is publicly financed (92.5% in 2015), a share that has not changed in the last ten years, less than 67% of ambulatory care was publicly financed in 2015, and this share has fallen from 77% in 1980 (Reference Le Garrec, Koubi and FeninaLe Garrec, Koubi & Fenina, 2013). But this overall coverage rate of outpatient care masks important differences: for the 83% of the population that does not benefit from statutory exemption of co-payments due to chronic disease (see below), coverage of outpatient care is only 51% (HCAAM, 2013). In other words, public coverage of ambulatory care has become relatively less generous over time and is quite low for the majority of the population.

Table 5.2 Health care financing by source of funds in France, 2015

| Total spending on health (%) | Hospital care (%) | Outpatient care (%) | Medical goods (%) | Medical transportation (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicines | Othera | |||||

| Statutory health insurance | 76.8 | 91.3 | 64.7 | 68.8 | 43.0 | 93.1 |

| Other public funds | 1.4 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Private insurance | 13.3 | 5.2 | 21.7 | 12.8 | 39.0 | 3.8 |

| Households | 8.4 | 2.3 | 11.7 | 17.0 | 17.2 | 2.2 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Note:

a Eyewear, dental prostheses, small medical devices and bandages.

Cost containment

For many years, health policy has focused on the need to curb public spending on health and to limit the statutory scheme’s deficits. The latter has been in deficit for more than 20 years, with an annual deficit that came close to 1% of gross domestic product in 2003 and 2004 and came close to these levels again during the financial crisis. In 2015, the social health insurance deficit was €5.8 billion (down from €6.5 billion in 2014 and €11.6 billion in 2010) representing in 2015 approximately 0.3% of gross domestic product (Comptes de la Sécurité Sociale, 2016). Successive reform plans,Footnote 10 typically combining a reduction in the benefits package with increases in contribution rates, have generally managed to keep spending growth in check for a few months, but no structural reform has ever been attempted. A 2004 reform was slightly bolder in this respect. It redefined the statutory health insurance funds’ joint role in financial stewardship and significantly increased their capacity to negotiate prices with providers and adjust the benefits package (see Reference Polton and MousquèsPolton & Mousquès, 2004 or Reference Franc and PoltonFranc & Polton, 2006).

The statutory health insurance deficit decrease of recent years is mainly attributed to a reduced growth in hospital spending and a drop in medicine prices caused by greater use of generic drugs. However, pressure on the system is unlikely to recede in the mid and longer term, particularly due to the price of innovative drugs – cost containment will remain a policy priority in the years to come (HCAAM, 2010; French Ministry of Health, 2016).

Purchaser–provider relations

The statutory health insurance scheme is the main purchaser of services in a system that is traditionally characterized by its limited emphasis on managing care – a system in which providers enjoy substantial autonomy. In 2015, nearly 60% of physicians worked in private practice on a fee-for-service basis, and provided the bulk of outpatient care (Reference SicartSicart, 2011; Reference Barlet and MarbotBarlet & Marbot, 2016). Global agreements negotiated between the statutory scheme and associations of health professionals set the tariffs for reimbursement of patients. Efforts to cap the overall amount paid to physicians in a given year have always failed due to opposition from the powerful physicians’ unions. However, in 2009, the statutory scheme, under the leadership of the main fund (Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés) and in spite of strong opposition from the physicians’ unions, managed to implement a pay-for-performance system for general practitioners (GPs) (the Contract d’Amélioration des Pratiques Individuelles). In addition to their fee-for-service income, participating GPs receive additional remuneration, which varies with their number of patients and their level of progress towards or achievement of quality indicators related, among other, to chronic patient care and prevention. GPs who do not achieve the targets are not penalized. In 2011, the pay-for-performance scheme was extended to additional specialties (cardiologists and gastroenterologists) and incorporated into the physicians’ collective agreement under the label “rémunération sur objectifs de santé publique” (ROSP). The list of indicators was also expanded to 29 indicators. In 2015, 68% of targets were achieved by participating physicians and 72% of them had progressed in their achievement compared with the previous year. Participating physicians received on average €6756 in 2015. The ROSP represented a gross spending of €404 million in that year and was fully provisioned for in the National Health Insurance Expenditure Target,Footnote 11 which was met that year.

Open-ended funding of the public hospital sector came to an end during the 1980s, when global budgets based on historical costs were introduced. Private hospitals, which currently provide two thirds of all surgical procedures, were paid on a fee-for-service basis until 2005. A diagnosis-related group payment system was introduced in 2004 and covered all hospitals by 2008. The harmonization of tariffs across public and private hospitals, initially announced for 2012, was postponed till 2016 and is still not fully achieved. On the other hand, diagnosis-related group tariffs are identical across public hospitals. The new payment system works in conjunction with national spending caps for acute care (Reference BusseBusse et al., 2011).

The significant role of private health insurance

Private health insurance complements the statutory scheme by covering statutory user charges. Its size and significance have increased over time. In 1960, the market covered about 30% of the population; this share grew to 50% in 1970, 70% in 1980 and reached 95% in 2013 (Reference Buchmueller and CouffinhalBuchmueller & Couffinhal, 2004; Reference FrancFranc, 2005; Reference Barlet, Beffy and RenaudBarlet, Beffy & Renaud, 2016). France is now one of the OECD countries where private health insurance is the most widespread. In 1960, private health insurance accounted for around 5% of total spending on health, rising to 12.1% in 2001 and 13.3% in 2015 (Reference Fenina, Le Garrec and KoubiFenina, Le Garrec & Koubi, 2010; French Ministry of Health, 2016). The share of private insurance in the funding of different types of health care varies, ranging from a low 3.8% for medical transportation and 5.2% for hospital care to 21.7% for outpatient services and 39% for nonpharmaceutical medical goods (see Table 5.2).

There is no systematic analysis of the determinants of this increase in demand for private insurance. In addition to the initial and continuing influence of mutuelles in the public policy environment (see below), it is safe to assume that increased demand has been prompted by increases in statutory user charges, deterioration in the extent of statutory coverage for certain types of care (with growing differences between the official tariff and the actual price paid by patients) and an income effect.

As out-of-pocket payments increased (from €217 on average per person and per year in 1980 to €604 in 2010 and €636 in 2015Footnote 12) and private health insurance became more widespread, differences in access to health care between the privately insured and those without voluntary insurance became more significant. Since 2000, additional public schemes have been set up to ensure that low-income households receive adequate financial protection. These have been designed around the concept of complementary insurance rather than targeted increases in the depth of statutory coverage, mainly to avoid stigmatization of households near the poverty line. These measures aim to ensure that poorer households have a dual coverage package comparable to the one available to the rest of the population (statutory plus complementary cover). They are also organized to prevent a household from having to change private insurer if its circumstances change.

The first scheme, the CMUC, was introduced in 2000, at the same time as entitlement to statutory coverage (CMU) became universal. This means-tested complementary insurance scheme can be managed by private insurer or by local statutory health insurance funds (the household chooses). Since 2009, it has been fully financed by a tax on private insurers’ turnover. Taking this tax revenue into account (€2.1 billion in 2015), the share of total spending on health actually financed by private insurers in 2015 is 14.4% rather than 13.3% (as reported in Table 5.2).Footnote 13 A second scheme, involving a voucher (l’Aide Complémentaire Santé, ACS), was introduced in 2005 to subsidize the purchase of private health insurance by all households with incomes below 135% of the CMUC’s threshold (since 2012). In 2014, between 64% and 77% of the target population (between 5.8 million and 7 million) was estimated to be covered by the CMUC, but the ACS, despite consistent efforts to extend take-up, reached only 1.35 million people by the end of 2015 (around 25% of its target population) (CMU Fund, 2016).

Overview of the private health insurance market

Types of insurer

The three types of insurer that operate in the private health insurance market differ in terms of their organizational objectives, the share that health care represents in their overall activity and the way they have been regulated. Their respective lobbies have a distinct influence on debate about the organization of the health system, often supporting differing views about the role that private health insurance should play and the type of regulation needed to facilitate it.

Mutuelles developed during the 19th century to provide voluntary social protection, including protection against health risks. In 1900, roughly 13 000 mutuelles covered over 2 million people and by 1939 two thirds of the population had some form of coverage against the financial risk of illness (Reference Sandier, Paris and PoltonSandier, Paris & Polton, 2004). Mutuelles also managed mandatory social insurance schemes introduced during the first half of the 20th century (although these were limited in coverage breadth and scope), but in spite of their political and economic importance they were not given a role in managing the social security system created in 1945. Instead, they laid the foundations for the private health insurance market (Reference Buchmueller and CouffinhalBuchmueller & Couffinhal, 2004).

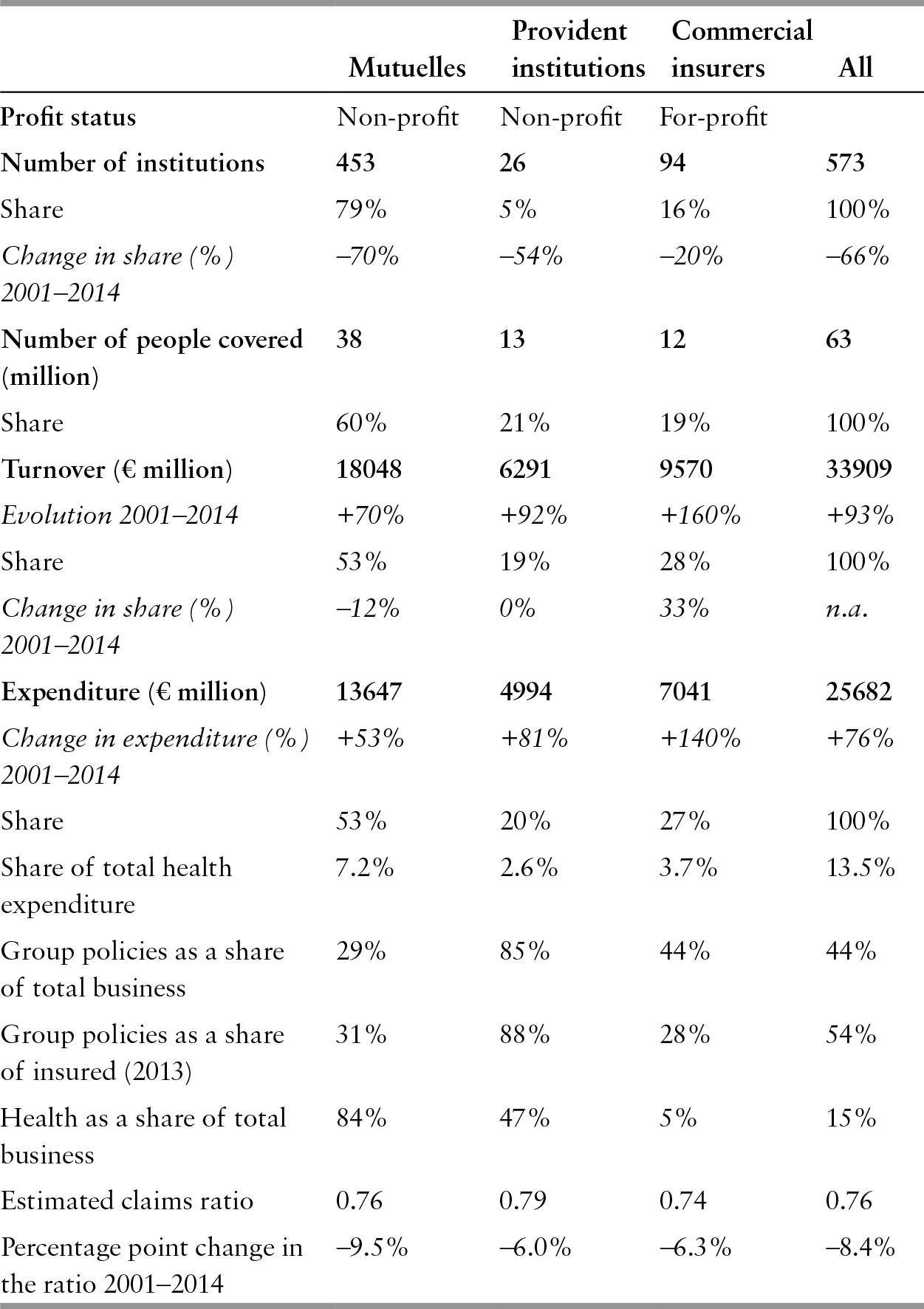

Membership of mutuelles is now usually open, although it was originally organized along occupational lines or in specific geographic areas. Historically, mutuelles emphasized mutual aid and solidarity among members, and broader social responsibility. This is reflected in the way they have traditionally conducted their business; for example, some mutuelles define premiums as a percentage of income. Complementary health insurance is now the mutuelles’ main line of business (see Table 5.3).

Table 5.3 Key features of the French private health insurance market, 2014

| Mutuelles | Provident institutions | Commercial insurers | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profit status | Non-profit | Non-profit | For-profit | |

| Number of institutions | 453 | 26 | 94 | 573 |

| Share | 79% | 5% | 16% | 100% |

| Change in share (%) 2001–2014 | –70% | –54% | –20% | –66% |

| Number of people covered (million) | 38 | 13 | 12 | 63 |

| Share | 60% | 21% | 19% | 100% |

| Turnover (€ million) | 18048 | 6291 | 9570 | 33909 |

| Evolution 2001–2014 | +70% | +92% | +160% | +93% |

| Share | 53% | 19% | 28% | 100% |

| Change in share (%) 2001–2014 | –12% | 0% | 33% | n.a. |

| Expenditure (€ million) | 13647 | 4994 | 7041 | 25682 |

| Change in expenditure (%) 2001–2014 | +53% | +81% | +140% | +76% |

| Share | 53% | 20% | 27% | 100% |

| Share of total health expenditure | 7.2% | 2.6% | 3.7% | 13.5% |

| Group policies as a share of total business | 29% | 85% | 44% | 44% |

| Group policies as a share of insured (2013) | 31% | 88% | 28% | 54% |

| Health as a share of total business | 84% | 47% | 5% | 15% |

| Estimated claims ratio | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

| Percentage point change in the ratio 2001–2014 | –9.5% | –6.0% | –6.3% | –8.4% |

Notes: An increase in the claims ratio denotes a deterioration in profitability (spending on benefits increases faster than premiums collected). Italics indicate the percentage change.

Provident institutions developed after 1945 to manage the newly created mandatory retirement schemes for employees. They later diversified their activities to provide other forms of social insurance to employees, including health insurance. Provident institutions operate on a non-profit basis and are jointly managed by representatives of employers and employees.

For-profit insurers entered the market in the 1980s to diversify their product range using health, some suspected, as a loss leader.Footnote 14 Health has remained a marginal line of business for them.Footnote 15

The French market is characterized by competition between types of insurance organizations. When commercial insurers entered the market, it was expected that, as they were not bound by solidarity principles, they would differentiate premiums to attract low-risk clients. The question that arose was whether mutuelles’ way of operating would remain viable in the face of adverse selection or whether they would be forced to adopt more market-oriented strategies in order to survive. The fact that their market share has remained remarkably stable suggests that a pragmatic balance was achieved, partly due to the “complementary” nature of the market, which limits the potential gains from differentiating between high and low risks, and partly due to successful marketing by the mutuelles to strengthen collective identity around values that appeal to their clients, such as nondiscrimination and solidarity (Reference Buchmueller and CouffinhalBuchmueller & Couffinhal, 2004). However, the mutuelles’ market share has declined since 2005, to the benefit of commercial insurers, whose market share increased by 33% between 2001 and 2014 (see Table 5.3). Risk profiles also differ across types of insurer: people aged over 60 years constitute 29% of mutuelles’ clients versus only 24% for commercial insurers, a difference which, if explained by a “cohort effect”, might decrease over time (in 2009, the shares were respectively 25% and 17%). Moreover, people aged under 25 years represent almost one third of mutuelles’ clients (30%), 23% of provident institutions’ clients and 28% of insurance companies’ clients. Recent changes in regulation (see below) may also explain why the balance between different operators is slowly shifting.

The health insurance market is not highly concentrated, although rapid consolidation has taken place in recent years. The number of insurers has decreased by two thirds since 2001, largely due to consolidation among mutuelles following a change in their regulatory framework in 2002. However, the market remains fragmented: in 2014, the 20 largest insurers accounted for 50% of business (in terms of turnover) while around 68% of insurers had an annual turnover of less than €14 million (less than 0.05% of total). At the other end of the spectrum, the five largest insurers have a turnover of over €1 billion (and the largest one over €2.2 billion, that is, approximately 6% of total) and 30 operators with turnovers of over €250 million (5% of insurers) accounted for 59% of total turnover. In 2014, the 10 largest (1.7% of the total number of insurers: four mutuelles, four provident institutions and two commercial insurers) accounted for 34% of premium income.

Overall, private health insurance seems to be a profitable business (see Table 5.3), particularly for commercial insurers. The industry-level claims ratio has deteriorated somewhat since 2001, largely due to the decline in profitability of mutuelles (perhaps because the latter are believed to cover a higher share of older people on average).Footnote 16,17

Private health insurance products

In 2014, more than half of the privately insured obtained cover through employment (see Reference Barlet, Beffy and RenaudBarlet, Beffy & Renaud, 2016). In 2013, 48% of firms (with more than 10 employees), corresponding to 70% of employees in the private sector, offered health insurance to their employees (Reference Barlet, Beffy and RenaudBarlet, Beffy & Renaud, 2016). Indeed, the probability of an employee being offered health insurance through the workplace varies with the size of the firm: in 2013, 46% of firms with 10 to 49 employees offered insurance compared with 76% of firms with 250 to 499 employees and 90% of firms with 1500 or more employees. The higher the proportion of executives in the company, the more likely the firm is to offer private cover and the more comprehensive this coverage is likely to be. Employers pay an average of 57% of the premium for their employees.

The provision of health insurance by employers was incentivized and is now mandatory. In 2009, a 2003 law (known as the Fillon law) came into effect after a transition period designed to allow employers to change the contracts they offer their employees. Under the law, tax exemptions for employers offering cover to employees are restricted to mandatory group contracts and contracts that comply with rules set by the authorities (see below). Over the transition period, companies adapted their supply of complementary health insurance to continue to benefit from tax rebates. In 2009, only 15% of employers offered voluntary contracts and 6% offered mixed contracts (mandatory for some statutory categories of employees and optional for others); these shares were 36% and 5%, respectively, in 2003. A third of the group contracts had been signed for less than 2 years. In January 2013, within the framework of a National Inter-professional Agreement, and in the context of a broader Law aimed at protecting employment (loi sur la sécurisation de l’emploi), the French government required all employers (irrespective of the size of their business) to offer private complementary health insurance to their employees from January 2016. This measure is expected to increase access to private health insurance for the employed, but its impact on the risk structure of the individual insurance market could lead to a rise in premiums for those covered (students, retirees, unemployed and civil servants) (Reference Franc and PierreFranc & Pierre, 2015).

Surveys of the privately insured (Reference Couffinhal and PerronninCouffinhal & Perronin, 2004; Reference 176Célent, Guillaume and RochereauCélent, Guillaume & Rochereau, 2014), insurers (Reference Garnero and RattierGarnero & Rattier, 2011; Reference 178Garnero and Le PaludGarnero & Le Palud, 2014) and more rarely of employers (Reference Guillaume and RochereauGuillaume & Rochereau, 2010) have led to a better understanding of the products available. They show that there is large variation in the extent of financial coverage among private health insurance contracts. Some only reimburse statutory user charges, including for goods and services for which the official tariff is notoriously lower than the market price (minimal coverage).Footnote 18 More comprehensive contracts reimburse patients beyond the official statutory tariff. The most comprehensive ones offer reimbursement that exceeds the average price for the good or service covered. Their beneficiaries can therefore use services that are priced above the market average (which is itself higher than the statutory tariff) and face no out-of-pocket payments beyond the mandatory nonrefundable statutory co-payments.Footnote 19

The distribution of coverage levels for individual contracts depends highly on the type of contract (group or individual). It was roughly as follows in 2013: around 22% of individual contracts offer minimal coverage (compared with only 6% for group contracts), an additional 69% provide limited coverage (compared with 29% for group contracts), 6% offer average coverage (compared with 13% for group contracts) and the remaining 3% are very comprehensive (compared with 53% for group contracts) (Reference Barlet, Beffy and RenaudBarlet, Beffy & Renaud, 2016). However, the content of insurance contracts is rapidly changing: for instance, the 2013 law mandating group health insurance also defined a minimum basket of benefits. In 2015, the content and the price of complementary health insurance contracts eligible for the ACS voucher were also regulated (see below).

In 2013, the average annual premium in the individual market for a contract covering single individuals aged between 40 and 59 years was €612; this premium was around 49% higher for individuals aged between 60 and 74 years and 85% higher for older individuals (Reference 178Garnero and Le PaludGarnero & Le Palud, 2014). The premium for a contract providing minimal coverage was around 15% lower than the contract offering average coverage for single individuals aged between 40 and 59 years. The average annual premium for a group contract in 2013 was €840 and was 29% higher for a very comprehensive coverage contract, keeping in mind that employers usually pay for around 57% of the premium. The premium for 91% of individual contracts varied with age in 2013 (100% of contracts offered by insurers and 89% of contracts offered by mutuelles). Although private insurers typically offer a larger number of contract options than mutuelles, there are no systematic differences between types of insurer in terms of coverage depth.

A recent trend towards increased product diversification makes it more difficult for consumers to compare contracts. In the last 15 years, many insurers have started offering “cafeteria plans”, in which the insured are invited to select their level of coverage for each type of care.

These are being marketed as a way of adapting the contract to individual needs while keeping it affordable. Another trend is for insurers to cover preventive services, irrespective of whether they are publicly covered, or even alternative or complementary medicine (for example, chiropractic services, homeopathic remedies). Some insurers now also offer ex-post premium rebates to policy-holders based on utilization (in effect a no-claims bonus system) (HCAAM, 2007). By purchasing these types of products, households provide insurers with a wealth of information about their utilization patterns and, indirectly, their health status. However, this method of (indirect) risk rating does not yet appear to be much of a concern in policy debates.

The tradition of “managed care” is not strong among private insurers. Complementary benefits are closely based on statutory benefits and, for most services, represent a small portion of the total cost of care (except for optical and dental care). As a result, private insurers have had few incentives and little leverage with which to engage providers and undertake active purchasing – all the more so because the statutory sector has not enjoyed much success in this domain either. Mutuelles have a long history of direct service provision through dental clinics, optical centres, pharmacies and even hospitals. In 2015, there were roughly 2600 such facilities open to the general public (including 746 optical shops, 475 dental centres, 54 pharmacies), with a total turnover of €3.7 billion.Footnote 20 However, while mutuelle-owned facilities are known to provide services at low prices (in particular for dental care), with the exception of a few leading institutions, their reputation for quality is not so good.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, some private insurers initiated more proactive interventions in the health care sector, often involving “call centres”. Most of this activity relates to dental care and eyewear and is advertised as customer service rather than risk management or cost control. For example, insurers may evaluate proposed fees or offer to negotiate prices on behalf of patients or set up more formal agreements with provider networks. These agreements may contain elements of quality improvement and price moderation in return for potential increases in service volume, but remain relatively loose because selective contracting is illegal. More recently, some insurers have bypassed this problem by organizing and becoming partners of an independent platform that manages networks of health professionals and contracts directly with patients who choose to join. Another area of intervention by insurers is the provision of advice about health and prevention.

Little information is readily available about these projects, their success or even their number. A rapid analysis of the 10 largest private insurers’ websites shows that they all offer the services described above to some extent and use this offer as a marketing argument. Some mutuelles promote access to their providers’ networks more proactively as part of this strategy. Others have created dedicated structures, sometimes as joint ventures, that openly seek to become service providers to a range of insurers. A significant initiative was launched by the mutuelles in 2006: with an initial focus on cancer, cardiovascular diseases and addictions, regional call centres provide guidance, medical advice and support to their members in what could eventually become a “disease management” approach. The consensus seems to be that while call centres and other managed-care activities have not yet been profitable, this type of investment could pay off in the long run, particularly if the scope of private health insurance increases. The most recent initiatives typically rely on communication technologies, with the introduction of telephone applications to monitor reimbursements, locate in-network providers, or advise patients on prevention. The largest insurance company even offers telephone consultations and the possibility of subsequently picking up a prescription at a nearby pharmacy.

Market development and public policy

Until the early 1990s, public authorities had paid little attention to the private health insurance market and its regulation. Although the market had grown steadily, the attitude of the public authorities could have been described as benevolent “laissez-faire”, with an implicit encouragement of the market’s development. Indeed, as pressure on the public system’s finances increased, the government welcomed the fact that private health insurance could neutralize, to an extent, the perceived impact of unpopular cost containment decisions such as increases in user charges. Over time, however, a series of factors contributed to changing the market’s operating environment. First, competition grew following the entry of new insurers. Second, it became increasingly obvious that there were socioeconomic differences in access to health care, and that financial barriers, linked to socioeconomic differences in access to private health insurance, were an explanatory factor. Third, as pressure to curb public spending on health persisted, and as both statutory and complementary cover provided similar incentives to patients and providers, there was growing recognition that better coordination among them could enhance efficiency in the health system. Each of these factors has led to the introduction or revision of specific aspects of the regulatory environment for private health insurance.

Policy debates and regulatory dynamics have been influenced by the positions of the two main players in the market – commercial insurers and mutuelles –who promote different types of regulation. On the political front, because of their historical role and their specialization in the health sector, mutuelles have always played a key role in health system policy debates through their main professional association (Fédération Nationale de la Mutualitée Française, FNMF), and have been represented on the boards of the statutory health insurance funds since 1996. As a lobby, FNMF has traditionally taken the view that complementary insurance is critical to accessing health care and market regulation should therefore be conducive to an environment in which no discrimination can take place; redistribution among risk groups and even social classes is encouraged, or at least an environment in which firms that operate on these principles are somewhat shielded from market competition. More broadly, FNMF claims a strong commonality with the statutory scheme and advocates comanagement of the health system to increase its efficiency.

The commercial insurers’ lobby (Fédération Française de l’Assurance, FFA) has never been as explicitly involved in policy debates as the mutuelles. As might be expected, they tend to support proposals that would increase the scope of private health insurance, and have actively lobbied to level the competitive field and eliminate what they argue are anticompetitive and unfair advantages granted to mutuelles (and, to a lesser extent, provident institutions). In the late 1990s, one of the bolder commercial insurers put forward a highly controversial proposal to introduce “health management organization-style” management of both statutory and complementary health benefits. The proposal generated heated debate, including among the commercial insurers themselves, and was eventually withdrawn (Reference Buchmueller and CouffinhalBuchmueller & Couffinhal, 2004).

Regulatory harmonization to encourage competition and increase transparency

Because their origins and governance models are entirely different, the three types of insurer have always been regulated under different sets of rules: the mutuelles by the Code de la Mutualité, the foundations of which were laid in the middle of the 19th century; the provident institutions by the Social Security Code; and commercial insurers by the Insurance Code. Two key differences in these rules later became the focus of debate: the mutuelles were subject to less stringent financial and prudential requirements than other types of organizations; and both mutuelles and provident institutions benefited from specific tax exemptions; in particular they were exempt from a 7% tax on insurance premiums and also enjoyed other exemptions linked to their non-profit status. This preferential treatment of non-profit organizations was intended to acknowledge their contribution to the general interest and their being embedded in the social economy.Footnote 21 In addition to being governed by different sets of rules, the activities of the three types of insurer were monitored by different bodies.

The need to transpose EU competition law into French law was the main thrust behind the increasing harmonization of insurer regulation. Favourable taxation of non-profit insurers violates EU policy requiring equal treatment of all insurers, independent of their form of organization. On these grounds, the FFA lodged a complaint with the European Court of Justice in 1993 and obtained a favourable ruling in 1999. In the wake of this, but also in order to fully transpose the EU insurance directives into national law, a series of changes took place.Footnote 22 The Code de la Mutualité was revised in 2003 to increase compliance with EU requirements, particularly with regard to prudential aspects, initiating a strong process of consolidation among the mutuelles. Indeed, the EU’s Solvency II Directive, which sets out stronger requirements for insurer capital adequacy and risk management, came into effect on 1 January 2016. This directive intends to ensure uniform and improved protection for insureds in the European Union and bring down the price of contracts. This European harmonization also aims to facilitate the control of international insurance groups and promote a single European insurance market. But this Directive induced a new challenge because mutuelles are owned by their policy-holders and are therefore limited in their capacity to raise capital in the financial markets. Due to strong competition in the private health insurance market and the implementation in 2002 of Solvency I and in 2016 of Solvency II Directives, the consolidation process among the Mutuelles has been rapid over the past 15 years (Table 5.3).

On the fiscal side, tax exemption criteria have been redesigned and now apply to contracts that fulfil specific criteria rather than contracts provided by a given type of organization. In response to the FFA complaint, from October 2003 exemption from the 7% tax on insurance premiums has been granted to all contracts that adhere to a “solidarity principle”. This principle prohibits an insurer from requesting any health information before subscription or charging risk-rated premiums. It automatically applied to mutuelles, and commercial insurers were expected to adapt their contracts to benefit from the exemption. The impact in practice may not have been very significant because underwriting was never a common practice in the private health insurance market. The 2004 health insurance reform added new criteria that the contracts must meet to remain exempt from insurance premium tax. So-called “responsible contracts” guarantee minimum levels of coverage and seek to enhance efficiency in the health system (see below).

By 2010, survey data suggested that virtually all private health insurance contracts met the criteria for responsible contracts (Reference 178Garnero and Le PaludGarnero & Le Palud, 2014). Since 2008, all tax exemptions previously only granted to non-profit entities, now apply to the share of any insurer’s business that adheres to the principles of a responsible contract (although such contracts also have to represent a significant share of their overall health insurance business).Footnote 23 However, to help curb the government deficit, taxes on these contracts were re-introduced, starting at 3.5% in 2010 (compared with 7% for nonresponsible contracts), and reaching 7% in 2014 (compared with 14% for nonresponsible contracts).

The three types of insurers are now supervised by a single authority.Footnote 24 Initially focused on insurers’ profit status, the debate on how private insurance should be regulated has gradually shifted towards trying to provide advantages to insurers that serve the general interest, regardless of corporate form. The changes brought about by this harmonization process have indirectly contributed to reaffirming the principles that differentiate the social economy from the business sector. For instance, before the 2003 Code de la Mutualité reform, mutuelles’ pricing practices were supposedly less discriminatory than those of commercial insurers, but they were free to decide how to set premiums. The new regimen explicitly bars mutuelles from risk rating: their premiums can vary only according to a subscriber’s income, length of time since initial subscription, statutory health insurance fund, place of residence and age, and based on the total number of insured. At the EU level, mutuelles have been actively involved in lobbying for the creation of a European Mutual Society Status and, by March 2011, a written declaration establishing European statutes for mutual societies, associations and foundations had been signed by most members of the European Parliament.

In an effort to further promote competition and transparency, the 2012 Social Security Financing Act requires all providers of voluntary health insurance to report to consumers the levels and breakdown of administrative costs (premium collection, portfolio administration, claims management, reinsurance), and acquisition costs (commissions, marketing, commercial networks) and the sum of these two amounts as a percentage of premiums.

Ensuring access to private health insurance to favour equity

Over time, and in the wake of cost containment reforms that shifted health care costs to the private sector through increased user charges, out-of-pocket spending on health gradually rose, exacerbating financial barriers not only to health care but also to private health insurance due to higher premiums. In the context of increased recognition of the importance of private health insurance in securing access to health care, a series of public interventions was introduced to enhance access to complementary cover for those likely to be excluded from the market.

The first major equity-related intervention in the market focused on risk selection and was primarily aimed at limiting underwriting and increasing portability. The 1989 Loi Evin defined a set of rules applicable to all insurers. It reinforced the rights of the privately insured by prohibiting: the exclusion of pre-existing medical conditions from groupFootnote 25 contracts; premium differentiation among employees based on health status; termination of contract or reduction in coverage once someone had been insured for 2 years; premium increases for specific individuals based on health status. It also allowed retirees and other individuals leaving a group to request their complementary coverage to be maintained by the insurer and limited any increase in tariff to 150% of the initial premium;Footnote 26 and enforced strict rules regarding information that the insurer had to provide to the insured (details of the benefits package) as well as to the employers (annual financial accounts for the contract). These rules were further strengthened in 2009, when the obligation to offer strictly identical coverage to former employees (except if the dismissal is justified by serious breach of employment contract) was confirmed in court, and in 2010 when an employer was condemned to pay compensation for failing to fully inform employees on the guarantees underwritten. The 2013 employment protection Law, which mandates private insurance for all employees, also enhanced the entitlements to coverage of former employees. Coverage must be maintained for up to 12 months (previously 9 months) free of charge for former employees.

The Loi Evin primarily focused on medical underwriting and, although it was implicitly concerned about the affordability of contracts, its measures were not specifically targeted at low-income individuals. The provisions of the CMU Act (2000) were the first to address income-related inequalities in access to complementary insurance. CMUC provides free complementary cover to all legal residents whose income is below a certain threshold, taking into account their household size. As of April 2016, the monthly income threshold was €721 for single adults and €1082 for two-person households. At the end of 2015, CMUC benefited 5.4 million people (3.5% more than the previous year) corresponding to 8% of the population,Footnote 27 including 44% of children and youth under 20 years of ageFootnote 28 (CMU Fund, 2016). Despite a 7% increase in eligibility thresholds in 2013 (which made up for a previous erosion in real terms), non-take-up remains high: it was estimated to be between 23% and 36% in 2014 (CMU Fund, 2016). No survey data are available on the factors explaining non-take-up, but a 2015 report from the French public audit commission suggested that the administrative burden imposed on eligible populations to obtain or renew their coverage constitutes a major barrier – including for people who are automatically eligible as recipients of other welfare payments (Cour des Comptes, 2015).

CMUC aims to provide poorer households with free access to health care. It covers all statutory co-payments, offers lump-sum reimbursements for eyeglasses and dental prostheses and prevents health professionals from charging beneficiaries more than the statutory tariff or the lump-sum amount. However, health professionals have not universally accepted this unfunded mandate. A situation testing undertaken in 2008 among a representative sample of physicians showed that a quarter of physicians rejected CMUC beneficiaries when they requested a first appointment by phone (Reference DesprèsDesprès, 2010). The rate was 32% among dentists and 9% among GPs (the latter are seldom allowed to charge more than the official fee).

A wealth of empirical studies has shown how health care use in France is higher among the privately insured than those without complementary cover.Footnote 29 When CMUC was introduced, it was argued that the provision of free care would generate abuse. However, the use of services by CMUC beneficiaries has been studied extensively and research shows that the scheme has had the desired impact. The first study showed that, although health care expenditure was much higher for CMUC beneficiaries compared with the rest of the population, this difference could be attributed to their worse health status; in fact, for a given health status, the use of care by CMUC beneficiaries was comparable to that of the privately insured (Reference RaynaudRaynaud, 2003). These findings have proved consistent (Reference BoisguérinBoisguérin, 2007).

Other longitudinal studies confirm that the increase in use pertained to types of care that individuals previously did not use and for which financial barriers were larger (for example, specialists’ services) (Reference Grignon, Perronnin and LavisGrignon, Perronnin & Lavis, 2007). In other words, CMUC appears to have achieved its objective of putting its beneficiaries on a par with the privately insured.

CMUC beneficiaries can decide who will manage their complementary cover: either a private insurer of their choiceFootnote 30 or their local statutory health insurance fund. Private insurers can choose whether they want to register as CMUC managers and must offer open enrolment if they do. In 2015, 56% of insurers were registered to manage CMUC contracts compared with over two thirds of all insurers in 2013 (CMU Fund, 2016). Registration is more common among larger insurers and also depends on the type of insurers: in 2015, 64% of mutuelles were registered, 83% of provident institutions and only a third of insurance companies (35%). At the end of 2015, less than 13% of CMUC beneficiaries chose to have their contracts managed by a private insurer (compared with more than 15% in 2012). This trend may have been established by the government, which automatically gave local statutory health insurance funds responsibility for covering 3.4 million people who benefited from the programmes CMUC replaced.Footnote 31 More generally, however, requesting private management increases the administrative burden for beneficiaries and, as a result, many of them prefer to let the local statutory health insurance fund manage both their statutory and complementary health benefits. On the supply side, the non-profitability of managing CMUC (see below) has undoubtedly been a powerful deterrent. CMUC beneficiaries are fairly concentrated among a small number of insurers: in 2015, the 16 insurers reporting more than 10 thousand CMUC beneficiaries managed around two thirds of all privately insured CMUC beneficiaries: 10 mutuelles covered 75% of these beneficiaries, five commercial insurers 21% and one provident institution 4%.

The CMU FundFootnote 32created in 2000 manages CMUC financing but the mix of funding sources has changed over time and overall the scheme appears to be slightly underfunded.Footnote 33 Initially, the Fund received around three quarters of its resources from the government budget and the remainder from a tax on private insurers’ turnover (CMU Fund, 2011). In 2006, this tax represented around 32% of the Fund’s resources, with the rest coming from earmarked taxes on alcohol (26%), taxes on tobacco (14%) and a transfer from the general revenue pool (25%). In 2009, the government stopped financing CMUC and it has since then been exclusively funded from the health insurance turnover tax (the rate rose from 1.75% in 2000 to 2.5% in 2006 and 6.27% in 2014). As of 2016, all taxes on health insurance contracts are administratively merged and a global rate of 13.27% applies to “responsible contracts” turnover (see above) and 20.27% to contracts not meeting these criteria. The 6.27% remains transferred to the CMU fund. In 2015, this tax represented around 85% of the Fund’s resources, the other 15% being derived from taxes on tobacco.

From its revenues, the CMU Fund reimburses managing institutions up to a flat amount per beneficiary of €408 in 2015,Footnote 34 either as a direct transfer to local statutory health insurance funds or as a rebate per registered beneficiary on the turnover tax for private insurers.Footnote 35 The average spending of CMUC beneficiaries managed by statutory health insurance funds tends to be significantly higher than that of those whose benefits are managed by private insurers (€416 vs. €376 in 2015), because the former, although younger, have worse health status on average (CMU Fund, 2016). Overall, the figures show that managing CMUC contracts is not a profitable business.

When beneficiaries lose their CMUC entitlement, provided their contract was previously managed by a private insurer, that company must offer them for at least 1 year a contract whose guarantees are very similar or identical to those under CMUC and whose annual premium is regulated (around €421 inclusive of taxes per adult in 2015). For low-income households with incomes above the CMU threshold, a voucher scheme (ACS) introduced in 2002 supports access to complementary cover. The voucher either creates an incentive for households that otherwise would not be able to afford private health insurance to purchase cover or, if they are already covered, helps them purchase contracts with more generous benefits. As of 2015, the scheme has been extended to all households with incomes below 135% of the CMUC threshold (the percentage was increased over time). Although the resources taken into account to measure monetary poverty are not the same as those used to assess entitlement to the ACS, at this point, the scheme appears to be available to most households who fall below the poverty line (Cour des Comptes, 2015). The amount of the yearly subsidy varies according to household characteristics (size and age); it was increased several times to reach €100 in 2015 for individuals under 16 and €550 for individuals over 60. Since July 2015, the ACS beneficiaries have to obtain their contract from a list of eligible providers selected by a public tender. Each provider’s bid had to include three predefined coverage options. Eleven providers (mostly consortia of insurance providers) were selected. By the end of 2015, 227 insurers offered contracts eligible for the ACS. They covered 80% of the ACS beneficiaries before the reform (which means that 20% of beneficiaries have had to change provider). This measure is estimated to have significantly reduced premiums between 2014 and 2015: by 14% for contracts providing the highest levels of guarantees, by 24% for mid-range contracts and by 37% for the contracts with the lowest levels of guarantees (CMU Fund, 2016).

In 2015, additional advantages were provided to ACS beneficiaries: they cannot be balance-billed by Sector 2 providers and they benefit from third-party payment. Further, they are exempted from the non-insurable co-payment at the point of service (see Table 5.1) and can decline mandatory coverage by the employer.

All these measures aim to expand take-up of the voucher, which, by the end of 2015 had only reached 1.35 million people, around a quarter of its target population (CMU Fund, 2016). A 2009 randomized experiment designed to understand why take-up is low showed that an increase in the benefit had a modest impact on take-up, but that targeted information sessions were poorly attended and considered to be a further deterrent by those who chose not to attend them. Among the 17% of the sample who ended up applying for the voucher, only a little more than half eventually received the benefit, and this uncertainty is likely to compound the administrative burden of applying (Reference Guthmuller, Jusot, Wittwer and DesprésGuthmuller, Jusot & Wittwer, 2011). The recent measures appear to have slightly improved take-up, which increased by 12.6% in 2015 (compared with 3.9% the previous year).

Analyses continue to show that progress is still needed to ensure better access to health care for low-income households and pensioners. A 2012 survey found that the risk of foregoing a doctor visit was three times as high for people with no complementary cover of any sort compared with those who benefit from non-CMUC private health cover (Reference 176Célent, Guillaume and RochereauCélent, Guillaume & Rochereau, 2014). Moreover, at similar levels of income, households that benefit from CMUC have a lower risk of foregoing care for financial reasons than those with non-CMUC complementary cover. In other words, there is still a high degree of heterogeneity in coverage among low-income households and there remain differences between the insured and uninsured which, by 2012, the ACS had not been able to bridge. More recent results confirm that while CMUC goes a long way towards bridging the gap between covered low-income households and “average” households, the uninsured – a significant share of whom could benefit from the ACS – continue to forego care more frequently for financial reasons (Reference BoisguérinBoisguérin, 2009; Reference 176Célent, Guillaume and RochereauCélent, Guillaume & Rochereau, 2014).

Most recently, access to insurance for pensioners has become a subject of concern, but actual implementation of recent regulation adopted to address the issue seems unlikely. Households with at least one retired member are as frequently covered as the general population by private insurance but they mostly subscribe to individual insurance contracts (93% compared with 54% for the population, Table 5.3). Their premiums are high, as are their remaining out-of-pocket payments. Health spending represents 5.6% of retired households’ disposable income (compared with 2.9 for non-retired households). It is as high as 6.6% of disposable income for those 76 years or older and 11% for households in the bottom quintile (versus only 3% for the top quintile) (Reference Barlet, Beffy and RenaudBarlet, Beffy & Renaud, 2016). The 2016 yearly Social Security Financing Act provided for the introduction of specific contracts for seniors. The measure was heavily criticized by all private insurers (see below) and the decrees laying out implementation details have not been published, considerably reducing the probability that the measure would become effective before the 2017 elections.

Incentives and efficiency in the health insurance system

In the last 10 years, policy-makers have paid increasing attention to the role that private health insurance plays in financing health care and to its complementarity with the statutory sector. Following efforts to improve access to complementary cover, attention has focused on the need to align incentives across statutory and complementary insurance and to better coordinate the two sectors. For many years, public authorities relied on private health insurance to compensate people for increases in statutory user charges. At the same time, it was widely acknowledged that this de facto cancelled any moderating effect that increases in user charges and similar measures might have had. Moreover, the resulting shift from public to private funding probably reduced fairness in financing the health system, as premiums are presumed to be less redistributive across income levels than taxes. Over time, private insurers became increasingly dissatisfied with their lack of involvement in the regulation of a system that they were increasingly expected to fund. The 2004 health insurance reform took steps to correct these problems and paved the way for the emergence of a new relationship between statutory and private insurers.

As mentioned earlier, the reform created a new type of “socially responsible” complementary contract that seeks to align incentives across statutory and private insurance and promote some minimum quality standards.Footnote 36 To qualify as responsible, a contract must provide a minimum level of coverage to policy-holders, systematically covering statutory co-payments for physician visits that take place within the gatekeeping system (leaving the patient with only €1 to pay per visit so long as they do not seek care from a physician who charges more than the official tariff); increase the reimbursement rate for most common drugs (from 65% to at least 95%), as long as these are prescribed within the gatekeeping system; and refund statutory user charges for at least two priority preventive services out of those listed by the Ministry of Health. In addition, it must not reimburse the higher statutory co-payments incurred by patients who seek care outside the gatekeeping system or cover nonreimbursable co-payments (see Table 5.1). In other words, the corresponding share of individuals’ health care expenditure has become explicitly nonrefundable. Since April 2015, responsible contracts must comply with additional obligations including the capping of reimbursements for optical care and for the extra fees of the physicians who have not signed an “access to health care” contract.Footnote 37 Further, insurers are not allowed to cap the number of hospital catering day fees covered. In summary, a complementary contract is responsible if it provides a legally defined minimum level of coverage, if it contributes to promoting prevention and, more importantly, if it does not counteract the incentives embedded in the public sector’s cost containment measures.

A range of incentives aims to encourage the development of responsible contracts. In addition to the fiscal incentives targeting insurers noted earlier, fiscal incentives targeting employers who purchase group contracts have been in place since 2008 and, between 2005 and 2015, individuals could only use ACS vouchers to purchase responsible contracts (since 2015 the choice was further restricted between three options as discussed in the previous section). Although the impact of the 2015 reforms is not known, the market was not believed to have fundamentally changed between 2005 and 2015 because it was relatively easy for most insurers to adjust their contracts to the new requirements.

There was a sense initially that the reform would give the government a powerful lever to influence the content of complementary contracts and that it would be able to add new conditions over time. But decisions to replace tax exemptions with a tax penalty for nonresponsible contracts (+ 2% in 2011 and + 7% in 2014) – motivated by the need to control public deficits in the wake of the financial crisis – have undermined some of the reform’s potential. Moreover, private insurers objected to this measure and raised premiums, penalizing poorer households. In response, the government increased the ACS eligibility ceiling, a measure that was ultimately financed by private insurers. The main concern at this point is that the level of risk in the pool of those individually insured will increase due to the generalization of group insurance,Footnote 38 which could raise premiums and lead to further segmentation.

As cost-control measures and measures aimed at better aligning incentives for providers and patients were implemented simultaneously, it is impossible to assess how the reform may have affected patients. One thing is clear, however: the combination of all these reforms has made it very difficult for patients to understand and anticipate the net amount that they will ultimately have to pay out of pocket. The generalization of third-party payments for all physician fees partly aims to offset this by reducing how much individuals have to pay at the point of care.

The 2004 reform also created a platform to allow all private insurers to participate in the regulation of the health system and defend their interests. A new institution was set up and the 33 members of the board of the Union of Voluntary Health Insurers (Union Nationale des Organismes d’Assurance Maladie Complémentaire, Unocam) represent the three types of private insurer.Footnote 39 For the first time, complementary insurers are explicitly and formally involved in national discussions on health care and health insurance. Unocam is mandated to publicly comment on the draft version of the Health Insurance and Social Security Financing Act, which sets the budget for these institutions every year. It is also invited to participate in annual negotiations between the union of statutory health insurance funds and health professional unions, and it can collectively enter into direct negotiations with health professionals. Since 2009, Unocam has been actively involved, along with statutory insurers, in negotiations with surgeons, anaesthetists and obstetricians to define new rules for balance-billing. The rules would re-introduce this option within strictly defined limits while guaranteeing complementary cover of the extra fee to maintain access for all. In addition, Unocam is consulted before changes are made to the statutory benefits package; it can become a member of other health system institutions;Footnote 40 and it can act as a lobby for private insurers to promote a common agenda.

One of its main initiatives has been to lobby for private insurers to be granted access to statutory health insurance databases. Unocam argues that this would enable private insurers to fulfil their mission, particularly in managing responsible contracts, but the demand raises serious concerns about protecting the privacy and the confidentiality of medical information.Footnote 41

In spite of differences in the views of its members, Unocam now routinely contributes to public debate. This is largely the result of its working approach, which relies on technical working groups and studies in which all members participate. Nevertheless, the impact of this new platform is difficult to assess. Unocam is technically an advisory body and neither policy-makers nor insurers are bound to take into account its position. Many of its negative opinions or suggestions for cost savings in the health system have not been acted upon: for instance, Unocam issued a negative opinion on the draft 2016 Social Security Financing Act, which envisaged the introduction of insurance contracts for seniors, arguing that this plan would further segment the market and limit options for risk pooling. Nevertheless, Unocam has given complementary insurers a seat at the table.

Conclusions

Statutory coverage in France is universal and comprehensive, particularly when it comes to hospital care, and people suffering from chronic illnesses or undergoing costly treatments are generally exempt from statutory user charges. Nevertheless, during the 1990s, it became clear that those without private health insurance, especially people with low incomes, had less access to outpatient care. From 2000, the government introduced a series of measures to improve access to complementary cover, which is now recognized as an integral part of the social protection system. Evaluations indicate that the most significant measure, CMUC, has reduced inequalities in access to health care. Still, the take-up of the CMUC, and to a worse extent of the ACS, a subsidy meant to support the near-poor’s access to complementary cover, has been limited. Group coverage has been mandated for all employees since 2016. For those still uncovered and increasingly for those covered in the individual market, private spending on health constitutes a high burden and monitoring access to care will continue to be important. Still, among OECD countries, France has achieved the lowest share of out-of-pocket spending in total spending on health (OECD, 2017a).

From an equity perspective, over time, the development of private insurance has changed the extent to which health financing arrangements match financial burden with individual capacity to pay and distribute health care services and resources based on individual need. Indeed, measures aimed at curbing public spending on health care have shifted costs from statutory to complementary insurance, which by nature is less redistributive. However, the funding of CMUC and ACS by private insurers adds a degree of income-related cross-subsidization to the complementary market.

Ultimately, achieving such a high level of prepayment and risk-pooling by relying extensively on private insurance has a cost. Administrative spending on health represents 6% of current expenditure, the second highest proportion among OECD countries, well above the OECD average of 3% (OECD, 2017b). More than 45% of that administrative spending is incurred by private insurance – which covers around 13% of health spending.Footnote 42 Whether it might be possible to achieve the same level of coverage at a lower cost overall may be worth a debate.

By reimbursing statutory user charges, complementary cover can offset demand-side incentives put in place by the statutory system to contain costs. However, it has also promoted access and financial protection and has made affordable increases in price beyond statutory fee, for instance for physician services, eyewear and dental prostheses. In 2004 and more recently in 2013, the government introduced strong incentives for private insurers to offer so-called “socially responsible contracts” that support demand-side incentives and cap the rates of coverage for some types of care for which prices have rapidly increased over the past decade, like optical and doctors’ extra-fees. Indeed, historically, leaving private insurers to fill in the gaps left by the statutory system has given them little incentive to exert leverage over providers. Even if insurers have found themselves increasingly dissatisfied with their role of passive payer and have slowly started to engage providers more actively, it would be difficult to demonstrate that they have curbed the growth rate of these spending categories. There are initial signs – and certainly hopes – that the caps on the amounts insurers are allowed to reimburse through responsible contracts may be more effective in that respect, by curbing the willingness of those who have substantial coverage to pay ever more.

A final issue concerns the contribution of private insurance to the health system being transparent and understandable. On that account, performance is poor and probably declining: statutory user charges have increased many times; rules about what providers can charge patients were made more complex by the introduction of voluntary gatekeeping; complementary contracts are becoming increasingly diversified; and responsible contracts are subject to additional reimbursement rules. All in all, it is difficult to see how patients can anticipate the net amount they will have to pay out of pocket for each contact with the health system. On that account, the standardization of ACS contracts and the introduction of responsible contracts probably have contributed to reducing the heterogeneity. Still, overall, the system remains complex and costly.

After decades of laissez-faire, regulation of private health insurance has evolved rapidly in the last 15 years, with the authorities trying to strike a balance between equity, efficiency and reducing public deficits. Indeed, a key and persistent underlying tension comes from the need to keep public spending on health in check. Although the current system tries to align incentives across statutory and private insurers, the private insurers could be tempted to offer contracts that are not “socially responsible”, at least to those who can afford them. Such a shift would once again increase inequalities in access to complementary cover, perhaps not so much between the haves and have-nots as between those who can afford comprehensive but less regulated cover and those who cannot. An alternative scenario would be for statutory and private insurers to intensify cooperation and increase their attempts jointly to manage care and access to care and to influence provider behaviour and expectations. However, the French health system does not have a good track record on either of these fronts. Indeed, the 2004 reform, which paved the way for private insurers to have more say in the design of the health system and to be more closely involved in system-level negotiations between providers and the statutory health insurance scheme, has not fundamentally changed the dynamic of the system. Finally, excluding services from statutory coverage is a more radical option, which could redefine the scope and role of private health insurance but would require explicit and politically difficult discussions about the types of services that must remain funded publicly.

Analyses and debates around possible scenarios to improve the equity and efficiency of health financing have become more prominent in recent years (Reference Dormont, Geoffard and TiroleDormont, Geoffard & Tirole, 2014; Reference 179PierronPierron, 2016). Health was also an important topic of debate in the 2017 presidential election. The Government of President Macron has since confirmed its intention to focus on strengthening public health and prevention, but also reducing out-of-pocket payments for eyewear, dental and auditory prostheses and other measures, which could impact the private health insurance market.