The Zohreh Prehistoric Project (ZPP), a long-term archaeological research programme focused on the river valley south of the modern city of Behbahan in Khuzestan Province, was launched in April 2015 (Figure 1). The valley, which lies in close proximity to the northern coast of the Persian Gulf, was surveyed extensively during the early 1970s by Hans Nissen from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (Nissen & Redman Reference Nissen and Redman1971; Dittmann Reference Dittmann1984, Reference Dittmann1986). The ZPP aims to develop full-coverage archaeological survey of the valley, focusing on the human landscape over time, mostly in relation to settlement hierarchy and dynamics, modes of production and the emergence of regional centres at the end of the fifth and beginning of the fourth millennia BC. The focal point for the project is the principal site of the Zohreh Valley, known as Tol-e Chega Sofla (39RN1Q22108; the site was previously registered as Chogha Sofla, BZ.71 (Dittmann Reference Dittmann1984: 110). We have changed this to reflect its local name. The digital reference is the unique Iranian archaeology map registration number.

Figure 1. General map of the region and the location of Tol-e Chega Sofla (© GoogleMaps 2016).

During the late fifth millennium BC in south-western Iran, large cemeteries were established alongside residential areas. Some of these cemeteries formed around monumental structures, while others appeared in the territories associated with transhumant populations (Hole Reference Hole, Henrickson and Thuesen1989). The cemetery at the important centre of Susa is the largest yet discovered (Canal Reference Canal1978); in contrast, the cemeteries at Hakalan and Parchineh (Vanden Berghe Reference Vanden Berghe and Huot1987) on the southern flank of the Central Zagros Mountains cannot at present be associated with any contemporary settlements.

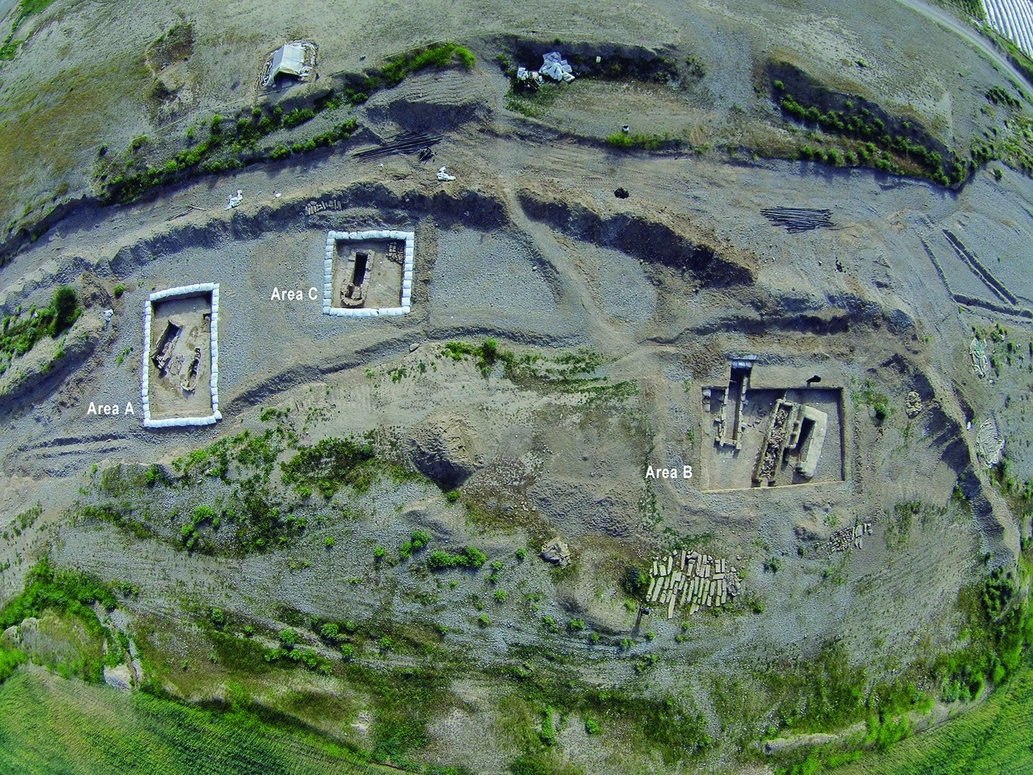

The first season of fieldwork at Tol-e Chega Sofla took place in spring 2015. A range of techniques was employed: mapping and topographic survey, surface artefact collection, geophysical survey, analysis of satellite imagery including ground-truthing, and test excavations. In particular, surface survey and geophysical prospection identified an extended cemetery area that was further investigated during the second season of fieldwork in winter 2016. Based on the geophysical results, nine burials were investigated across three areas (A, B and C) in the south-west part of the site where modern development projects had triggered an enormous gully running from south to north (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Aerial photograph showing the excavated areas.

The burials were contained in tombs of varying shape and architecture. Most take the form of rectangular chambers built of mud-brick, fired brick and stone. Interspersed between these structures were a small number of inhumations deposited in simple cuts into the natural silty layers. Nearly all of the tombs are oriented south-east to north-west, and may be associated with some sort of landmark or monument that has not yet been identified. As all of the tombs excavated in this season had been previously identified using geophysical survey, they may be biased to more elaborate funerary structures, and it is therefore inappropriate to draw conclusions here about the nature and diversity of the cemetery as a whole (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Geophysical map of the cemetery.

In most of the tombs, disarticulated and commingled human skeletal remains make it difficult to identify the number of individuals interred. In tomb 1 of area B (Figure 4), we estimate 52 individuals, based on the number of skulls. Our estimate of the total number of individuals from the nine excavated tombs is a minimum of 87, although we assume that the actual number must have been higher. The main phase of use spans from the late fifth to early fourth millennia BC, with some suggestion of activity continuing towards the end of the fourth millennium BC.

Figure 4. Tomb 1 in area B.

A number of socio-cultural differences between the deceased are apparent. Particularly striking is the visual evidence for head-shaping or cranial deformation. At least five examples were recovered from tomb 1 in area B (Figure 5). Most probably, the Tol-e Chega Sofla examples of cranial deformation are the result of circumferential head-shaping. The deceased were accompanied by ceramic and stone (alabaster) vessels (Figure 6), stone seals, metal discs and beads made of copper and a few small, golden objects. The ceramics usually consisted of jars, cups and small bowls. Every grave contains at least a few painted pots. The painted designs tend to be symbolic, and the motifs are often identical to well-known traditions in the Susiana and Fars regions.

Figure 5. A cranial deformation example from tomb 1 in area B.

Figure 6. 1) Small deep bowl; 2) small jar; 3) stone seal; 4) tall jar; 5 & 6) stone vessels.

The Zohreh Valley is an area of great archaeological interest. Its location between the Persian Gulf and the Zagros Mountains is significant, and we know of several late fifth-millennium BC settlements positioned along the River Zohreh. Among them, Tol-e Chega Sofla was the most important, demonstrating clear evidence of social differentiation expressed in the large cemetery located next to the residential area. The burials excavated in the first season demonstrate a diversity of architecture and material culture given the abundance of buried individuals. Future work, such as mtDNA and isotope analysis, will help to shed further light on socio-cultural differences.

The site of Tol-e Chega Sofla contributes to a wider understanding of the cultural, social, political, economic and religious developments during the initial emergence of complex societies in the Near East. Our investigations, through the ZPP, of the associated cemetery and the human occupation of the wider valley, works towards a recommendation to the Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicraft and Tourism organisation for the nomination of Tol-e Chega Sofla for inclusion on the World Heritage Site list.

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to the numerous people who participated in the first excavation season at Chega Sofla, particularly Javad Salmanzadeh, Mehrnoush Dabaq, Ahmad Sarkhosh, Mehdi Alipour, Mojtaba Aqajari, Zeynab Valizadeh, Laya Alinia, Sara Freydouni, Kazem Borhani, Hamed Vahdati Nasab, Koroush Mohammadkhani, Mandan Kazazi, Tiam Kahyash, Loqman Shohani, Ranin Yashmi and Ronak Ahmadinia. Field research relating to this project was supported by the Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism. My special thanks to Seyd Mohammad Beheshti and Hamideh Chubak, and also to my colleagues in the local ICHTO at Ahwaz, Behbahan and Ram Hormuz, and in particular to Atefeh Rashno, Khosro Neshan and Ehsan Barani.