Introduction

The literature on post-socialist family policy has repeatedly shown just how diverse the family policy environments in post-socialist Central and Eastern European remain (Fodor et al., Reference Fodor, Glass, Kawachi and Popescu2002; Szelewa and Polakowski, Reference Szelewa and Polakowski2008; Inglot et al., Reference Inglot, Szikra and Raţ2012; Javornik, Reference Javornik2014; Saxonberg, Reference Saxonberg2014; Kovács et al., Reference Kovács, Polese, Morris, Kennett and Lendvai-Bainton2017; Aidukaite, Reference Aidukaite and Sengoku2018). Similarly, there is a wealth of work – comparative, cross-national and featuring specific national contexts – about the gender biases and gendered outcomes of shifting family policy landscapes (e.g. Gal and Kligman, Reference Gal and Kligman2000; Haney, Reference Haney2002; Pascall and Kwak, Reference Pascall and Kwak2005; Saxonberg, Reference Saxonberg2014). By comparison, the ways in which (changing) family policy architectures may have contributed to socio-economic inequalities among families has attracted less attention (for partial exceptions see Haney, Reference Haney, Burawoy and Verdery1999, Reference Haney2002; Gábos, Reference Gábos, Kolosi, Tóth and Vukovich2000; Ferge, Reference Ferge2001; Fodor et al., Reference Fodor, Glass, Kawachi and Popescu2002; Szalai, Reference Szalai, Evers and Guillemard2012; Inglot et al., Reference Inglot, Szikra and Raţ2012; Kovács et al., Reference Kovács, Polese, Morris, Kennett and Lendvai-Bainton2017; Kovács, Reference Kovács2018; Szikra, Reference Szikra2018).

Furthermore, what we know about post-socialist family policy adaptationFootnote 1 following the political changes in 1989-1991 is marred by temporal and geographic fragmentation. Longue durée analyses (Inglot, Reference Inglot2008; Saxonberg, Reference Saxonberg2014; Hašková and Saxonberg, Reference Hašková and Saxonberg2016) complement a more ample body of single-country or small-n comparative works that typically span no more than ten to fifteen years. Different post-socialist regions have received various degrees of scholarly attention, with the fast-reforming Central European countries – Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia – featuring most frequently in the post-socialist welfare state and family policy adaptation literature.

Finally, temporal and geographic fragmentation has been coupled with empirical shortcomings. Firstly, comparative work has discussed family policies as regimes, assuming that different instruments together formed different types of coherent wholes. Secondly, comparisons have often served analytical ends, e.g. perfecting toolkits for comparison (Saxonberg, Reference Saxonberg2013; Javornik, Reference Javornik2014) or showing diversity (Fodor et al., Reference Fodor, Glass, Kawachi and Popescu2002; Saxonberg and Sirovátka, Reference Saxonberg and Sirovátka2006; Szelewa and Polakowski, Reference Szelewa and Polakowski2008), rarely engaging in a systematic fashion with changes in policy outputs and what these might cumulatively mean for socio-economically differently positioned families. Thirdly, analyses have often engaged with nominal policy changes, i.e. instances of policy ‘revision’ or policy ‘layering’ (Hacker, Reference Hacker2004: 248), ignoring policy ‘stasis’ (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010) as a potentially equally influential source of shifting policy outcomes. In other words, non-change has been conceptually equated with continuity not only of policy outputs, but also policy outcomes, which may be erroneous given possibilities for policy ‘drift’ (Hacker, Reference Hacker2004: 248). Finally, family policy analysis in the region has typically prioritised paid parental leave schemes and early childhood education and care (ECEC) service provision as the most influential instruments for social outcomes of interest (e.g. Fodor et al., Reference Fodor, Glass, Kawachi and Popescu2002; Saxonberg and Sirovátka, Reference Saxonberg and Sirovátka2006; Szelewa and Polakowski, Reference Szelewa and Polakowski2008; Javornik, Reference Javornik2014; Saxonberg, Reference Saxonberg2014; Hašková and Saxonberg, Reference Hašková and Saxonberg2016), with family transfers of less concern (for partial exceptions, see Ferge, Reference Ferge2001; Inglot et al., Reference Inglot, Szikra and Raţ2012; Kovács, Reference Kovács2018). Reflective of the more general marginality of tax breaks for social purposes (TBSPs) in social policy scholarship (Sinfield, Reference Sinfield and Greve2012; Morel et al., Reference Morel, Touzet and Zemmour2018), family tax breaks have been largely ignored in the extant scholarship (partial exceptions are Kovács, Reference Kovács2018; Szikra, Reference Szikra2018).

In short, what we know about how and how much family policy instruments have been changing in post-socialist national contexts remains reflective of a narrow gendered perspective; geographically, temporally and empirically fragmented; and typically losing sight of the impact of policy non-change on policy outcomes, including socio-economic differences. Consequently, there is need for analyses that focus on policy adaptation, both radical and incremental, alongside an analytical interest in the impact of changing and non-changing policy outputs for socio-economically differently positioned families’ social entitlements. Second, there is need for homing in not on national family policy regimes as coherent wholes, but on ‘assemblages’ of policy instruments (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Bainton, Lendvai and Stubbs2015), taking a programme-by-programme approach. Third, there is need for analyses that span longer timeframes than a decade. Fourth, there is need to include national contexts that we know less about, e.g. the Baltics and the easternmost post-socialist welfare states. Fifth, there is need to expand the analysis to family transfers, including tax breaks.

The analysis incorporating these analytical concerns serves to show that three decades of adaptation of family transfers in three different family policy environments – Hungary, Lithuania and Romania – is best understood as dualisation in social entitlements (Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012: 11-12). The article builds on recent scholarship that shows that post-2010 Hungarian and Romanian family policy adaptation is expressly anti-‘weak’ and pro-‘strong’ and asks: how recent and how important is this trend? Does it happen beyond these two national contexts? And, finally, through what modes of policy adaptation are institutional dualisms engineered?

The second section discusses the literature on dualisation, a more general trend affecting Bismarckian welfare architectures. It also contextualises the three country cases, expanding briefly on family transfer programmes in preparation for the discussion in the fourth section. The third part presents the analytical approach that also informs the development of the novel social legislation dataset that this article draws on. The latter is also presented here. The fourth section discusses in detail the over-time adaptation of various family transfers in Hungary, Lithuania and Romania during the 1990-2018 period. The fifth section concludes.

Conceptual background and national family policy contexts

Historical institutionalist work on post-socialist family policy adaptation has engaged in perhaps the most coherent fashion with issues of policy change, favouring long timeframes (Inglot, Reference Inglot2008; Saxonberg, Reference Saxonberg2014; Hašková and Saxonberg, Reference Hašková and Saxonberg2016). It should not come as a surprise, though, that the story such analyses have told is one of institutional resilience and endurance, with at most ‘bounded’ changes on a specific policy path (Inglot, Reference Inglot, Cerami and Vanhuysse2009: 75). In effect, ‘bounded’ change treated as inconsequential to policy architectures has meant that the magnitude of ‘creative adaptations’ (Inglot, Reference Inglot, Cerami and Vanhuysse2009: 75) and their impact have often been left unproblematised and unexplored. Yet, as scholars of incremental institutional change argue, entire social protection systems can be undone through small adjustments (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010). Secondly, historical institutionalists also fail to discuss the impact of no formal changes on social rights, treating institutional continuity and policy stasis as stability. However, the impact of policy drift – a situation where rules are not changed and, in time, their impact shifts as the environment within which they operate changes – or policy layering – new rules introduced alongside older ones, in time diminishing the impact of the latter (Hacker, Reference Hacker2004: 248; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010: 16–17), can have massive implications for social protection (Szikra and Tomka, Reference Szikra, Tomka, Cerami and Vanhuysse2009; Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012; Kovács, Reference Kovács2018). Finally, historical institutionalist accounts have been restricted to Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia: their conclusions are, thus, narrowly applicable.

We owe detailed accounts of family policy adaptation to single-country analyses for periods of ten-to-fifteen years. Many offer useful insight into reform outputs, with more work on some national contexts than others (for Hungary, see Haney, Reference Haney, Burawoy and Verdery1999; Gábos, Reference Gábos, Kolosi, Tóth and Vukovich2000; Ferge, Reference Ferge2001; Fodor et al., Reference Fodor, Glass, Kawachi and Popescu2002; Inglot et al., Reference Inglot, Szikra and Raţ2012; Hašková and Saxonberg, Reference Hašková and Saxonberg2016; Szikra, Reference Szikra2018; for Romania, see Fodor et al., Reference Fodor, Glass, Kawachi and Popescu2002; Inglot et al., Reference Inglot, Szikra and Raţ2012; Popescu, Reference Popescu2015; Kovács et al., Reference Kovács, Polese, Morris, Kennett and Lendvai-Bainton2017; Kovács, Reference Kovács2018; for Lithuania, see Gavelis and Visockas, Reference Gavelis and Visockas2013; Aidukaite, Reference Aidukaite and Sengoku2018). It is this body of work that has commented on the implications of social policy adaptation for social rights, more frequently, though, homing in on paid leave schemes and ECEC services rather than family transfers. Some analysts observe that post-socialist social protection has become increasingly individualised and privatised, asymmetrically affecting people across the income, skills and age distribution and along ethnic and geographic divides (for Hungary, see Ferge, Reference Ferge1997, Reference Ferge2001; Haney, Reference Haney, Burawoy and Verdery1999; Szalai, Reference Szalai, Evers and Guillemard2012). The disappearance of high employment rates quickly led to the relegation of the less fortunate to a narrow set of social programmes, notably newly introduced means-tested poverty alleviation schemes and universal, flat-rate benefits, implicit disentitlement (Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012: 9) taking hold for persistent labour market outsiders. At the same time, contributory social security programmes became restricted to persistent labour market insiders, as seen elsewhere in Bismarckian welfare states (Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012). Szalai (Reference Szalai, Evers and Guillemard2012: 299) used the term ‘bifurcated’ welfare state to describe what is essentially increased institutional dualism in social protection. The bifurcation of family entitlements along socio-economic lines seems to have taken shape recently not only in Hungary, but in Romania also (Inglot et al., Reference Inglot, Szikra and Raţ2012; Kovács et al., Reference Kovács, Polese, Morris, Kennett and Lendvai-Bainton2017; Kovács, Reference Kovács2018), with secure labour market insider families able to access more and more generous entitlements, while their labour market outsider peers have had access to fewer and less generous benefits.

Much of the literature on dualisation has pertained to persistent differences in labour market status (Busemeyer and Kemmerling, Reference Busemeyer and Kemmerling2020), while institutional dualisms have been most frequently discussed in relation to unemployment protection and old-age pensions (Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012; Rueda, Reference Rueda2014): institutional dualisms in family policy have not been of notable concern. Yet, one might expect insider-outsider differences given that paid parental leave schemes and tax breaks for dependents are employment-related (indeed, employment-exclusive). And while institutional dualisms need not lead to outsiders being left behind (Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012: 11–12), recent Hungarian and Romanian paid parental leave and cash-for-care provisions seem to have enhanced rather than mitigated divisions among parents. On the other hand, family policies also extend to universal and means-tested direct transfers, entitlements not tied to labour market status. In short, given the variety of risks (and needs) that family policy instruments cover, they represent a fertile policy domain for analysing the temporal dynamics and mechanics of dualisation.

Research from the 2010s suggests that institutional dualisms have become evident in two historically different family policy environments, Hungary and Romania. However, it remains an empirical question whether these are a recent development or predate crisis-induced family policy adaptation not only for less-researched Romania, but also for Hungary – where, for instance, the reported universality of parental leave and related cash transfer during the 1990s (Szelewa and Polakowski, Reference Szelewa and Polakowski2008: 124) fails to account for the fact that within a decade the ratio of universal-to-insurance claimants reversed, from one-to-two to two-to-one (Ferge, Reference Ferge2001: 124).Footnote 2 Furthermore, might institutional dualisms in family policy be a more universal trend, driven by similar structural pressures and tackled politically in a similar vein regardless of policy legacies? Theorists of dualisation would argue that this is a likely hypothesis (Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012: 7–8). In other words, one would expect institutional dualisms in other family policy environments, too.

Consequently, in addition to extending the timeframe for analysis to the entire post-socialist period for lesser researched direct and indirect family transfers in Hungary and Romania, the article also extends its geographic scope to include Lithuania. This post-Soviet Baltic nation was described as having a ‘comprehensive support’ family policy regime during the 1990s (Szelewa and Polakowski, Reference Szelewa and Polakowski2008), incidentally the same as Hungary, based on its cash-generous and initially high-coverage paid leave scheme and inclusive, good quality ECEC services following 1995. In Javornik’s (2014) classification, Lithuania was in the ‘supported de-familialism’ category, while Hungary was classified as explicitly familialist. Romania was not included in either of these comparisons, but other analysis has suggested that post-2005 Romanian family policy comes closest to an explicitly familialist regime (Kovács, Reference Kovács2018: 58). Still, these classifications focussed on work-family reconciliation during the early years: cash transfers were omitted. As this article further details, Hungary, Lithuania and Romania have differed notably in terms of available family transfers.

Hungary’s child allowance scheme introduced in the 1950s was extended piecemeal, becoming a universal, generous programme by 1990 (Gábos, Reference Gábos, Kolosi, Tóth and Vukovich2000; Ferge, Reference Ferge2001). Hungarian working parents could also claim family tax breaks for most of the last three decades. Finally, Hungary had an inclusive approach to supporting parental care during the early years through a two-pronged arrangement: (since 1992) a universal flat-rate benefit (known as gyermekgondozási segély (GYES)) alongside an earnings-related, insurance-funded paid leave scheme (gyermekgondozási díj (GYED)) (Ferge, Reference Ferge2001; Tárkányi, Reference Tárkányi2001; Hašková and Saxonberg, Reference Hašková and Saxonberg2016).

Lithuanian family allowances and family tax breaks were geared towards families with young children and large families during the 1990s. The family allowance was extended piecemeal to small families and older children starting in May 2004, means-tested between 2008 and 2017, with a universal benefit alongside the means-tested one introduced as late as 2018. Family tax breaks became available to all working parents in 2002, but were phased out in 2018. The paid parental leave scheme, initially up to children’s first birthday, then the second starting in 2008, was rather inclusive, with permissive eligibility criteria until 2009, as well as cash-generous.

Romania’s socialist-era earnings-related child allowance was replaced by a flat-rate universal programme in 1993, and extended with a means-tested supplementary allowance in 1997. Family tax breaks were absent for most of the 1990s, and since 2000 they have been close to universal for working families, but systematically ungenerous. The paid parental leave scheme introduced in January 1990 was initially inclusive, but eligibility tightened due to labour market contraction and increasingly more stringent conditionalities. It became a selective, though cash-generous programme by 2006, when it became tax-financed (Kovács, Reference Kovács2018: 63).

Analysing transformations of social rights over time

Analysing social protection with an eye to changes in social entitlements has a respectable pedigree. From Titmuss (Reference Titmuss, Pierson and Castles2006 [1968]: 130–31) on, comparative welfare state analysis has made frequent use of analysing differences and similarities in entitlements by social programme, with a focus especially on eligibility criteria and net replacements rates, to highlight differences and variations in welfare state architectures (most influentially Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). However, just as the quick succession of static images can produce animation, so can an analytically consistent review of programme design specifics over time reveal patterns of changes and continuities, enabling one to trace the ethos of welfare state adaptation coherently. As foregrounded, the goal is to outline changes and continuities in family policy entitlements over a longer timeframe, sensitive to socio-economic differences, in three rather different national contexts.

For this purpose, a new datasetFootnote 3 was compiled using an analytical scheme inclusive of programme specifics derived from the literature on comparative (family) policy analysis (see below). Information in the dataset was drawn from publicly available social legislation in the original languages for Hungary, Lithuania and Romania on the range of universal, means-tested and employment-conditionalFootnote 4 family policy instruments and, unprecedented for Lithuania and Romania, personal income taxation and TBSPs. The timeline for each instrument is temporally complete, covering all months between 1990/1991 and December 2018.Footnote 5 For Hungary and Romania, secondary literature was used as a starting point to identify relevant legislation and for extracting the analytically relevant programme design specifics. To corroborate information in the dataset, data from the Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC) reports and Leave Network (2019) country reports were also used. For Lithuania the dataset was built from scratch for the 1990s and corroborated with information from MISSOC and Leave Network reports for the 2004-2018 period.

The dataset covers (i) eligibility criteria; where relevant, (ii) conditionalities on receipt; and (iii) benefit levels (in relative terms for universal and means-tested benefits and replacements rates for income-replacement benefits), the most frequently reported programme specifics (e.g. Ferge, Reference Ferge2001; Kovács, Reference Kovács2018). For leave-related transfers the dataset also covers (iv) benefit duration (in these three countries the cut-off for receipt, reflective of legal provisions) (Szelewa and Polakowski, Reference Szelewa and Polakowski2008; Javornik, Reference Javornik2014; Hašková and Saxonberg, Reference Hašková and Saxonberg2016). Reflective of legal provisions, for leave-related transfers the dataset also includes information on (v) minimum benefit values, when stipulated; and (vi) caps, when stipulated. Finally, the dataset includes information on (vii) funding source, reflective of the types of public funds (un)available to different claimant groups. For TBSPs the dataset offers information on these items as well as on (viii) computation formulae taken directly from the legislation, where relevant. To serve cross-national comparison, benefit levels are computed as a percentage of gross minimum wage.Footnote 6

The ethos of family policy adaptation: increasing dualisms through high-income bias

This section discusses the ways in which Hungarian, Lithuanian and Romanian family allowance schemes, family tax breaks and paid parental leave-related transfers changed over time (or, indeed, not). The goal is to explore the over-time evolution of differences in entitlements among socio-economically differently positioned parents.

Family allowances

As transfers to families aimed at easing the financial burden that raising children represents, child or family allowances have existed in all three countries analysed here prior to and throughout the 1990-2018 period. However, while the Hungarian and Romanian programmes have been near-universal at least since their redesign in the early 1990s,Footnote 7 the Lithuanian programme became universal only in 2018. Beyond this notable difference, programme changes reveal more commonalities than differences.

One similarity has been the expansion of eligibility in terms of age, coupled with school attendance-related conditionalities (see Tables O1-O3 online). The extension of eligibility past sixteen (in Hungary) and eighteen (in Lithuania and Romania) for those in secondary, post-secondary and, in Lithuania, even university education suggests that these welfare states have become increasingly more committed to supporting families with children studying past compulsory education. At the same time, Hungary and Romania also implemented exclusionary school-related provisions. In Hungary the family allowance was renamed ‘schooling support for children of school age’ in 1998, its spending subject to child protection services oversight if school-aged children were not attending regularly. The benefit was made conditional on regular school attendance in 2011. In Romania, the introduction of the universal, flat-rate allowance in 1993 explicitly excluded children aged seven or older not enrolled in compulsory education. This conditionality was eliminated in 1998. However, school attendance-related conditionalities re-emerged recently, with the means-tested supplementary family allowance made conditional on regular school attendance in 2011, leading to a sudden 60 per cent drop in the number of claimants (Popescu, Reference Popescu2015: 99). In the context of an EU-wide push for policies supporting social investment (Morel et al., Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012), the extension of these programmes to studying young adults should not be surprising. Perhaps not even the conditionalities on receipt for school-age children should be seen as problematic were it not for the fact that in both Hungary and Romania school dropout and (very) low educational attainment have been persistently concentrated among the most impoverished, rural, often Roma children (OSI, 2007), achieved in part through illicit school segregation (Kertesi and Kezdi, Reference Kertesi and Kezdi2013; Rostas and Kostka, Reference Rostas and Kostka2014). Consequently, the extension of eligibility for those in (post-)secondary education while curtailing the access of the neediest to a nominally universal family transfer reads more like the disciplining and policing of the poor (Inglot et al., Reference Inglot, Szikra and Raţ2012; Szalai, Reference Szalai, Evers and Guillemard2012) and the restriction of tax-financed entitlements to ‘proper’ (non-Roma) families only.

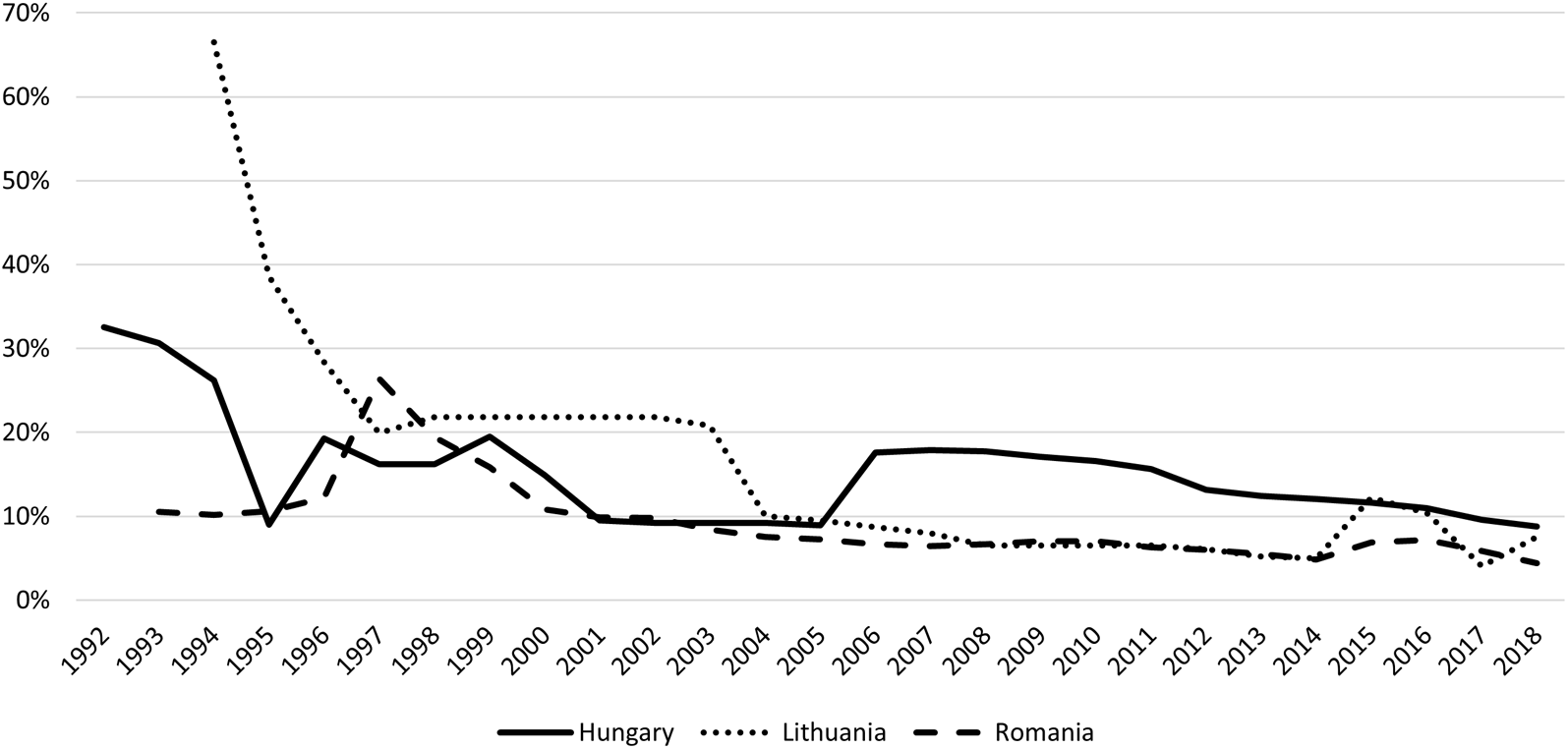

A more subtle way to undercut the entitlements of the neediest especially has been the erosion of family allowance benefit levels through wilful non-indexation (see Figure 1), a classic case of policy drift (Hacker, Reference Hacker2004: 248; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010: 16–17). In Hungary the steepest decline in relative benefit values took place between 2008 and 2018 against the backdrop of the elimination of regular indexation in 2009 (Inglot et al., Reference Inglot, Szikra and Raţ2012: 34). In Lithuania, similarly, the allowance eroded significantly between the early 1994 and 2017 as a result of non-indexation, while the universal component introduced in 2018 represented a mere 7.5 per cent of the gross minimum wage. In Romania, the family allowance also declined from its all-time high in 1997 to an insignificant transfer by 2018, with the obligation of regular indexation eliminated in 2005. Consequently, both the transfer for over twos and that for under-twos, introduced in 2007, remained unchanged for long periods.

Figure 1. Family allowance transfers as a percentage of gross minimum wage for families with one child in Hungary, Lithuania and Romania, 1992–2018

Sources. Own calculations based on minimum wage and family allowance legislation.

Notes. For years with several values for the gross minimum wage and/or for the transfer, annual averages were computed using monthly values.

In Hungary the benefit was means-tested between 1995 and 1998: information for this period is the benefit value for the lowest income band.

In Lithuania during the 1994-2004 the benefit could be claimed only for children under three: between birth and age three in families ineligible for the statutory paid parental leave and between age one and three in families with statutory paid parental leave entitlement. Between 2008 and 2017 the benefit was means-tested. Only information for children older than three (2004-2011) and children older than two (2012-2018) is provided here. For 2018 only the newly introduced universal per child benefit is reported. For more information on the family allowance, see Table O2 online.

In Romania the per child universal benefit is reported for the 1993-2006 period and only that for children older than two for the 2007-2018 period.

The Romanian means-tested supplementary family allowance is the only exception to this trend due to regular indexation after the introduction of means-testing in 2003 (see Table O3 online). Still, the benefit is ungenerous by any standard. Furthermore, its conditioning on regular school attendance starting in 2011 made it exclusionary towards the poorest families, those whose children leave school early (Popescu, Reference Popescu2015; Kovács, Reference Kovács2018).

In sum, the changes in family allowance schemes in these three nations reveal convergence towards nominally universal, but in Hungary and Romania selective, family transfer schemes. In Hungary and Romania, universalism came early, but was eliminated piecemeal, targeting the most ‘undeserving’ (i.e. neediest) since the mid-2000s, warranting the damning conclusion of Hungarian analysts (Ferge, Reference Ferge2001; Szalai, Reference Szalai, Evers and Guillemard2012; Szikra, Reference Szikra2018). In contrast, Lithuania shifted from decades of age-based selectivity and differentiation, a decade of means-testing in the wake of the 2008-9 crisis, to a universal – but ungenerous – family transfer in 2018 alongside the means-tested instrument. Opposing trends concerning eligibility have been coupled, however, with the same pattern in benefit level adjustments: from making a substantial contribution to household income during the early 1990s, family allowance schemes transformed piecemeal into inconsequential, ‘pocket money’ amounts by the late-2000s, remaining so since.

Tax breaks for families with dependent children

Tax breaks have been long treated as indirect transfers by virtue of their effect on earners’ purchasing power (Titmuss, Reference Titmuss, Abel-Smith and Titmuss1987: 48): as foregone income tax, they increase families’ disposable income just as direct cash transfers do. But because they are restricted to earners, typically to employees on incomes from wages, they are inherently selective. In addition, tax breaks tend to be more generous towards higher-income earners, particularly in progressive personal income tax regimes, where net tax rates increase with gross income and where, as a consequence, net tax savings increase correspondingly (Sinfield, Reference Sinfield and Greve2012; Morel et al., Reference Morel, Touzet and Zemmour2018). In addition, when family tax breaks work in tandem with others, these tend to be even more skewed towards higher-income earners, having little-to-no saving impact for those at the bottom of the earnings distribution when standard tax breaks reduce low-wage earners’ tax burdens to (close to) zero. This has been observable for longer or shorter periods in Hungary, Lithuania and Romania over the last three decades (see Tables O4-O6 online).

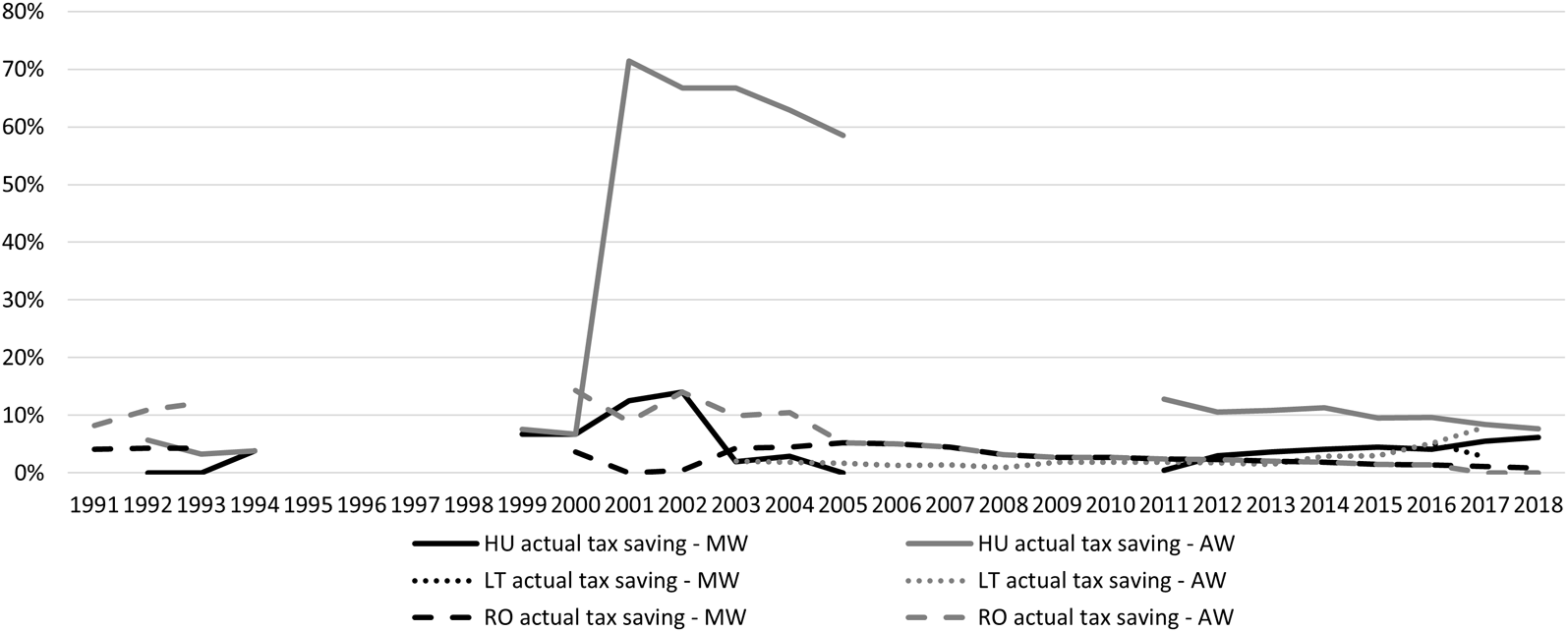

A longitudinal perspective on tax breaks for dependents in the three countries analysed shows that in Hungary family tax break generosity has gone up and down, peaking during the 2001-2005 period for families with three or more children. With progressive personal income tax (PIT) regimes up to 2010, average-wage earners typically benefitted more than their minimum-wage peers, not least because minimum-wage earners enjoyed zero de facto PIT levels through standard tax breaks, cancelling savings through other means, including family tax breaks (see Figure 2). The full measure of the pro-wealthy bias of Hungarian family tax breaks, signalled by Szikra (Reference Szikra2018) for the last decade, but – as shown here – much more pronounced during the 2001-2005 period, is borne out by the fact that the maximum tax savings through family tax breaks accrued to incomes as high as eight times the gross minimum wage (for three or more children, see Table O4 online).

Figure 2. Actual tax savings as a percentage of gross minimum wage for minimum-wage earners and average-wage earners for a single dependent in Hungary, Lithuania and Romania, 1991–2018

Sources. Own calculations based on personal income tax legislation.

Notes. MW means gross minimum wage; AW means gross average wage.

In Hungary the tax break for dependent children was discontinued between 1995 and 1998 and was restricted to families with three or more children between 2006 and 2010.

In Lithuania the tax break for dependent children was restricted to families with three or more children between 1992 and 2002. Family tax breaks were phased out in 2018.

In Romania the tax break for dependents was discontinued between July 1993 and 1999.

In contrast, Lithuanian family tax breaks during the 1990s were reserved for single parents and those raising three or more children (see Table O5 online). With the new tax code of 2002, families came to be treated much more similarly regardless of the number of children, with total tax savings per family converging regardless of size. This was achieved through two mechanisms: by making the tax allowance for one or two children complementary to the personal allowance (2003-2008), but making the tax allowance for three or more children the more attractive alternative to the standard tax allowance. Secondly, the increase in the value of the tax allowance in 2016-2017 was undercut by the reduction in the flat PIT rate, from 24 to 15 per cent, thus reducing net tax savings. With the introduction of the universal flat-rate child allowance in 2018, family tax breaks were eliminated. Unlike Hungary, where family tax breaks have been systematically geared towards high-income earners, Lithuania shifted over time from favouring large working families to all working families irrespective of the number of children to, finally, eliminating this regressive indirect family transfer altogether.

Romania has been much more similar to Lithuania in that family tax breaks were absent or meagre for the vast majority of earning families between 1991 and 2018 (see Table O6 online), with marginal regressive impact. In addition, average-wage earners benefitted more than minimum-wage earners infrequently from these instruments between 2000-2004, against the backdrop of generous standard tax allowances reducing minimum-wage earners’ overall tax burdens to close to zero. As a result of policy drift, the tax allowance for dependent children declined in value between 2005 and 2018, remaining available only to those with incomes less than twice the minimum wage. Overall, then, with the exception of the 2000-2004 period, indirect transfers to Romanian families were absent or at best ungenerous, increasingly more so during the flat tax period (2005-2018) and typically flat across the income distribution, i.e. with negligible regressive impact.

In summary, three decades of family tax break changes show that Hungary stood out with markedly regressive family tax breaks during the early 2000s and more tempered versions since 2011. In contrast, Lithuania and Romania had much narrower and more ungenerous family tax breaks, with the value of indirect transfers typically low and flat. In other words, selective redistribution towards (secure) labour market insiders through the tax system was by far the most notable in Hungary and very limited or absent in Lithuania and Romania over the last three decades.

Parental leave transfers

In all three nations eligibility criteria for paid parental leave tightened steadily between 1991 and 2018 (see Tables O7-O9 online). By 2018, all three nations shared the same conditions to qualify for leave and the related cash benefit: twelve months of earnings and/or insured status during the twenty-four months preceding childbirth, with either parent eligible. Moreover, while eligibility conditions were adversely affecting the right to claim of persistent outsiders, all three nations expanded eligibility in ways that narrowly favour those highly qualified. In Hungary, undergraduates and master’s students gained the right to a special parental leave (the so-called diplomás GYED) in 2014. In Lithuania, recent graduates under twenty-six became eligible regardless of employment status in 2008. In Romania, enrolled pupils and undergraduates became eligible for paid parental leave in 2006, master’s students and PhD candidates in 2010. Secondly, provisions became increasingly more permissive towards combining what remains defined as an income-replacement transfer with earned income during the leave period. In Lithuania, parents going on paid parental leave could also undertake paid work while in receipt of the benefit between 1991 and 1995 and since 2008. In Hungary, the right to undertake paid work while in receipt of GYED payments was introduced in 2014. In Romania, employment and paid leave were incompatible, with the law expressly ruling out income-generating activities while on paid leave between 2006 and 2016. Still, during this period parents foregoing part or all of their statutory leave were eligible to claim a so-called ‘stimulant’, whose value and duration have been increasing since 2011. And since 2016 parents on leave can earn up to a low threshold. In short, while eligibility criteria tightened across the board, all three leave schemes became increasingly more inclusive of highly skilled parents specifically, but not other groups, especially since the mid-2000s. In addition, recent policy adjustments enabled parents to cash in the leave-related benefit alongside earnings.

Furthermore, paid parental leave schemes came to be used everywhere to channel additional cash-for-care transfers especially towards parents able (and willing) to return to employment earlier, i.e. the better-off with more options to delegate childcare, engendering yet another dualism: between professional, high earners and between less skilled, low-wage earners. The bias towards secure labour market insiders in coverage and the transformation of an income-replacement transfer into an employment-conditional, cash-for-care top-up, all of it tax-financed, bears out the full extent of what is a labour market status-differentiated, increasingly regressive family policy instrument, excluding the neediest families and disproportionately benefitting above-average income dual-earner couples.

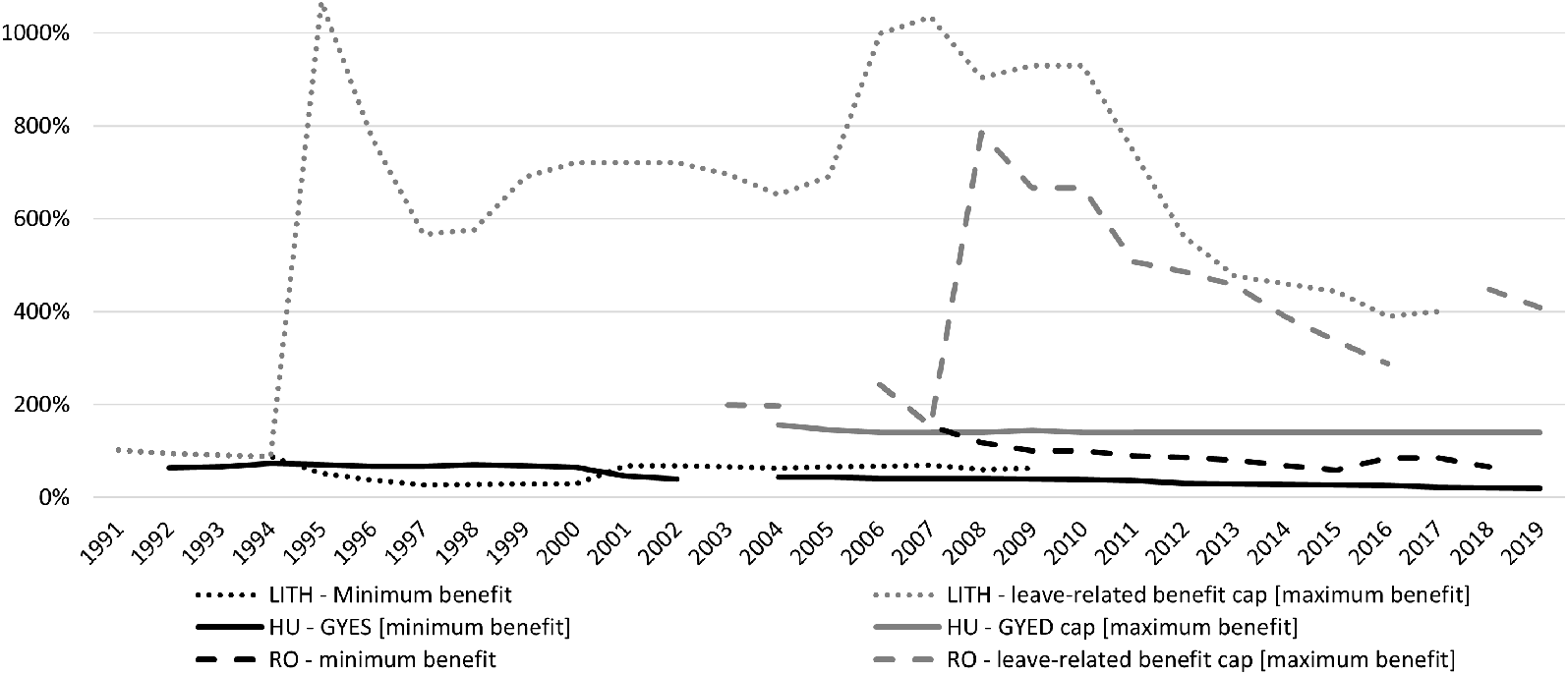

Benefit levels add further evidence to this trend. In Hungary, the universal GYES declined notably between 1992 and 2018, its value eroding during the 1990s (Ferge, Reference Ferge2001) and between 2008 and 2018 in the absence of an automatic indexation mechanism. In contrast, the earnings-related GYED, its maximum gross value tied to the comparatively ungenerous cap of 200 per cent of net minimum wage, kept up in relative terms. And while in real terms the GYED is far less generous than its Lithuanian or Romanian counterparts, the possibility to combine it with full-time work exposes its regressive potential (Szikra, Reference Szikra2018). In Lithuania, following the fast erosion of the leave-related transfer between 1991 and 1994, the benefit increased piecemeal to 100 per cent of gross earnings starting in 2008 (for the shorter leave). While the cap was typically very generous (see Figure 3), its relative decline after 2010 overlapped with parents’ right to undertake paid work while on leave. Still, it should be noted that Lithuania used the family allowance as a cash-for-care benefit for inactive parents between 1994 and 2004, the latter the equivalent of the GYES rather than that of the mainly universal family allowance scheme. Since, however, the absence of a cash-for-care instrument available to outsiders makes an increasingly more cash-generous transfer for insiders a core element of a bifurcated social rights regime.

Figure 3. Minimum and maximum benefit levels as a percentage of gross minimum wage for paid parental leave transfers in Hungary, Lithuania and Romania, 1991–2019

Sources. Own calculations based on relevant legislation and secondary literature: for Hungary Gábos (Reference Gábos, Kolosi, Tóth and Vukovich2000: 118); Leave Network (2019) annual reports; and reports of Nemzeti Foglalkoztatási Szolgálat [National Occupation Service] (2020).

Notes. In years with several gross minimum wage values an annual average was calculated using monthly values.

For Hungary there is missing data for the 2003 GYES value. No GYED cap was in place between 1990 and 1995 and the GYED was phased out between 1996 and 1999. Missing data for GYED caps for 2000–2003.

In Lithuania the benefit was flat-rate between 1991 and 1994, with a higher benefit during the first eighteen months of leave, reported here. No minimum benefit was stipulated between 2010 and 2018. No government-insured income, relevant for the cap, was announced for 2018 or 2019.

In Romania no minimum benefit existed between 1990 and 2005. There is missing data on caps for 2001, 2002, 2004 and 2005. The benefit was flat-rate during 2006–2007. For 2011–July 2016 the cap was calculated for the higher benefit, applicable to the shorter leave. There was no benefit cap between July 2016–2017.

The evolution of the Romanian programme echoes the post-2004 Lithuanian situation in that a universal cash-for-care benefit has never existed. With eligibility tightening starting in 2006, parents without labour market participation prior to birth have been excluded. As in Lithuania, benefit levels rose steadily, from 65 per cent of net earnings in 1990 to 85 between 2001-2005 and since 2016.Footnote 8 It should be noted, however, that while the minimum benefit level was not stipulated in law (until 2005), and then remained quietly unchanged (between 2006 and 2016) thus eroding significantly, consecutive governments erratically changed caps between 2006 and 2018, consistently concerned with and rewarding above-average income earners.

In summary, it is paid parental leave programmes that most consistently showed an over-time evolution overtly favouring those with strong labour market attachment in all three nations. In Hungary this trend intensified in the wake of the 2008-9 crisis in Hungary with the universal GYES left unchanged, eroding, while the GYED was automatically indexed. After a decade of a two-pronged cash-for-care entitlement, the Lithuanian leave-related benefit increased in generosity, while the family allowance – the cash-for-care alternative for inactive new parents – was extended to all families. In the wake of the crisis, both the Lithuanian and Romanian leave schemes were amended, with different incentive structures for high-income and low-income earners, respectively. Furthermore, parents on leave can now combine leave-related transfers with earnings everywhere, boosting in particular above-average income earners’ labour market attachment and earnings. These programmes are perfect illustrations of tax-financed selective, pro-‘strong’ and anti-‘weak’ social policy.

Conclusion: Three decades of selective family policy against the neediest

Analyses of post-socialist welfare state and family policy change have repeatedly emphasised diversity. This conclusion is echoed here for family transfers. However, the article also shows that there has been notable similarity also, specifically in the ethos of changes. The analysis centred on the question of whether differentiation in family benefits based on families’ socio-economic status and the disenfranchisement of the neediest is a persistent feature of family policy adaptation beyond post-2010 Hungary and Romania. More specifically, the article sought to temporally and geographically extend evidence of institutional dualisms in family entitlements by taking a systematic look at close to three decades of family transfers – including tax breaks for dependents – in Hungary, Romania and Lithuania.

A programme-by-programme overview has led to two generic conclusions. Firstly, when comparing like to like, eligibility, conditionalities and benefit levels have fared similarly, often with similar timelines. This is illustrated well by nominally universal family allowances in Hungary and Romania, as well as the Hungarian GYES and the Lithuanian family allowance, respectively. The latter restricted to families with children under three and available to inactive parents as a cash-for-care benefit. There is also striking similarity in the over-time evolution and, ultimately, decline of benefit levels, including the means through which this decline was engineered. Across the board, universal benefits have exhibited the same evolution: starting out as comparatively generous during the early 1990s, their value eroded sometimes very quickly thanks to the non-existence or elimination of indexation, leading to policy drift. The Hungarian family allowance scheme and the GYES between 2008 and 2018, the Lithuanian family allowance scheme during the late 1990s and 2000s, and the Romanian family allowance scheme during 2008-2018 are all cases in point. By 2018, all three nations had (conditional) universal family allowance schemes with ungenerous benefit levels. The universalisation of Lithuanian child allowance in 2018, particularly as it overlapped with the elimination of the family tax allowance scheme, represents a notable challenge to this story of similarities: instead of greater differentiation along socio-economic lines, Lithuania made a U-turn with the introduction of a universal – albeit ungenerous – direct transfer.

A second conclusion is that only through a programme-by-programme approach do we see that Hungary’s apparent egalitarianism in the value of family entitlements. Hungary maintains a universal child allowance, a universal GYES to complement a contributory GYED with a comparatively ungenerous cap – in contrast with overall selective Lithuanian and Romanian family transfer environment thanks to employment-conditional, cash-generous paid parental leave transfers. Thus, it has been systematically undermined by an enduring, generous and selective family tax break skewed towards high-income earners especially. Indeed, while the Lithuanian and Romanian programmes on which these nations’ pro-insider bias has hinged affect families with children under three especially, rather than all families, the Hungarian pro-wealthy policy instruments apply to families with children of all ages, with an effectively much broader scope. In other words, restricted eligibility criteria, increasingly more generous benefits and high caps resulting in the exclusion of those most exposed to outsider status among parents – the unqualified, parents from economically depressed areas, young parents without employment history – affect parents of young children only, and do so temporarily in Lithuania and Romania. In Hungary, however, recently increased disparities in benefits during the early years continue well past children’s first three years of life as indirect transfers for dependents can be claimed until children reach adulthood.

The time period analysed in this article also suggests greater similarity than difference: everywhere the discrepancy between what secure labour market insider families on the one hand and persistent labour market outsider families on the other could claim was relatively small during the 1990s: benefit level erosion was repeatedly counterbalanced in Hungary and Romania, though not Lithuania after 1995. In addition, both Hungary and Lithuania relied on a two-pronged cash-for-care instrument for new parents for much of the 1990s. Greater selectiveness through tightened eligibility and an increase in benefit generosity in paid leave-related transfers became noticeable during the mid-to-late 2000s across the board.

In conclusion, for much of the post-socialist decades the assemblages of Hungarian, Lithuanian and Romanian family policy instruments differed, but they all seem to have shifted in ways that reveal the same ethos: universal benefits have become increasingly more ungenerous, while employment-conditional benefits more difficult to access and increasingly more cash-generous. In other words, institutional dualisms in social protection have increased across the board. That relegates those outside the formal labour market to erosion-prone universal and means-tested benefits, with employment-conditional transfers in Lithuania and Romania tax-financed. Indirect transfers through the tax system, particularly generous in Hungary, particularly benefit those with strong formal labour market attachment (and high incomes). Due to the diversity of families it affects, the assemblage of family transfers in Hungary seems most pro-wealthy and anti-weak.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746421000828