By April 1854, Samuel Gurney Cresswell was on board the Archer off Elsinore in Denmark as part of the Baltic fleet.1 Back in London, sketches that he had created were being transformed into a series of eight lithographs that would be published in colour by Day and Ackermann.2 It was not until 31 July that he wrote to his parents from the Archer: ‘I am very glad to hear that the sketches are done so well, pray send me a copy out.’3 Cresswell’s letter to his parents serves to remind us that naval officers were primarily in the service of the navy and were not overseeing the publication of prints derived from their on-the-spot drawings. Although Cresswell had no input into the final appearance of the lithographs, which were very different in style to his sketches and paintings, such published prints carried, and indeed still carry, an aura of authenticity due to their close associations with ‘factual’ visual records.

The concern with truth and accuracy that permeated the discourse surrounding Robert Burford’s panorama extended to lithographs produced of the Arctic during the Franklin searches. Their format, price, and close association with naval officers, whose sketches they purported to reproduce, indicated an authority that could be ‘relied upon as exactly truthful’.4 These views, considered as artefacts replete with knowledge of the Arctic, displayed ‘much power and truth’.5 However, much like the panorama painters, the lithographic artists who worked on the Arctic prints used their imagination and aesthetic awareness to create a different version of the Arctic. As the search progressed, their representations heightened the sense of humanity’s battle with nature through perilous positions and performative suffering. The convincing presentation of the lithographs still leads to their reception as authentic ‘sketches’ and factual records amongst critics and the public today.

Like the panoramas, sets of lithographs based on officers’ drawings created new versions of the Arctic imaginary. Tensions between knowledge and ‘truth’, on the one hand, and a concern with portraying the difficulty of the search, on the other, become apparent through examining lithographs produced from the search expeditions. As a medium, lithography was associated with natural history and other sciences as well as with landscape views. However, the cost of lithographs put them well beyond the means of the average panorama-goer.6 Ten Coloured Views Taken during the Arctic Expedition (1850) by William Henry Browne was the first such folio of lithographs from the Franklin search to be published.7 It was followed by two more sets in 1854 and 1855: Cresswell’s A Series of Eight Sketches in Colour … of the Voyage of H.M.S. ‘Investigator’ (1854), which included a map of the newly discovered Northwest Passage, and Walter William May’s A Series of Fourteen Sketches Made during the Voyage up Wellington Channel (1855).8 A second edition of Cresswell’s Eight Sketches was completed at Day and Son in January of 1855.9 Edward Augustus Inglefield, who led three summer expeditions to the Arctic from 1852 to 1854, also had four tinted lithographs printed in late 1853 that showed ‘critical’ and ‘perilous’ situations of ships among the ice; these were published by Dickinson Brothers and sold individually.10

In this chapter, I look closely at a selection of these lithographs through case studies in transformation, dissemination, and reception, noting how an almost irrefutable authority was conferred on the prints that were done from on-the-spot sketches by officers on the Franklin searches. Browne’s lithographs show the conflicting interests of scientific accuracy and commercial potential, the latter exemplified by the tendency of lithographers to heighten sublimity in order to increase the attractiveness of prints. Cresswell’s folio reveals how an officer’s uncertain sketches could be rendered as confident and apparently reliable prints by accomplished lithography artists. Finally, the lithographs by May elide any cheerfulness from his work, in favour of struggling figures that epitomise the idea of ‘heroic failure’, a concept that increasingly became attached to polar exploration from the period of the search expeditions.11 In both Cresswell’s and May’s prints, and to a lesser extent in Browne’s, the power of nature and the ‘man versus nature’ trope increasingly stand in as an alibi for failure.

Despite their frequent use to illustrate present-day popular texts on polar exploration, the lithographs themselves have received little sustained critical attention. Instead, they decorate publications and are frequently taken as factual artefacts, serving as eye-catching enhancements rather than as objects of critical inquiry. As Brian Maidment notes, ‘prints, however documentary their mode or literal their intentions, can never be entirely naturalistic representations of the past’.12 Bernard Smith reminds us too that documentary drawing, based on the perceptions of draughtsmen, also relies on ‘a stock of visual memories drawn from their worlds’.13 Nevertheless, it is likely that prints such as lithographs, when not exact copies of the original drawings, combine a greater proportion of inventive drawing from the mind of the lithographic artist. A common mistake among scholars is a failure to distinguish between lithographs – the product of printing houses in the metropole – and paintings or sketches done by expedition members in the Arctic. References to lithographs as ‘paintings’ or taking prints to be exact reproductions of an artist’s work are frequent errors. Such analyses fail to take account of intermediaries: the work of the accomplished lithographic artists such as William Simpson, Edmund Walker, and Charles Haghe, the printing firms like Day and Son or Ackermann, which ultimately were commercial operations, and the influence of the Admiralty, to whom all records from expeditions had to be given. Lithographic artists generally took on the production and supervision of lithography in the metropole.14 This was particularly the case where amateur artists (such as the Arctic officers) were concerned, although professional artists might draw on the lithographic stones themselves.15 In fact, in the case of some of the Arctic lithographs, even a cursory glance shows the paintings and preparatory sketches to which we have access to be very different from the published lithographs. This suggests that the lithographic artists exercised their own imaginations and what they had learned from viewing earlier Arctic representations to enhance, improve, or exaggerate the officers’ drawings. However, the use of the word ‘sketches’, in the titles of Cresswell’s and May’s lithograph folios, seeks to disassociate the works from any intermediary. The word implied ‘authenticity and truthfulness’, a certain ‘truth status’, and sketches were seen as establishing an ‘intimate relationship between artist and audience’.16

This chapter analyses the content of the lithograph folios while paying close attention to the officers’ sketches, the geographical contexts, and the specific origins of the lithographs, reminding us that, as Tim Youngs reiterates with respect to travel writing, ‘we should not assume a uniformity of mode or perception of travel in the nineteenth century’.17 Furthermore, the dissemination and reception are attended to by the examination of contemporary reviews, advertisements, and other information. Throughout the discussion that follows, I argue that, in some cases at least, the lithographic responses to the Arctic are more likely to be those of British lithographic artists, publishers, and Admiralty figures than of expedition members whose sketches they purported to reproduce.

Invented in the late eighteenth century, lithography is a planographic technique of printing on limestone that was valued particularly for the illustration of topography and natural history, as it facilitated finely graded shading and details that were difficult to achieve using engraving.18 It was considered to be a more direct method of reproduction, since engravers were not required to transfer the image to a plate or block and drawings did not have to be converted to linear designs as they did for engravings.19 The process was also considerably cheaper than engraving.20 Louis Agassiz, who always employed his own artists to illustrate his work, set up his own lithographic printing operation in 1838 in order to improve standards of illustration in scientific texts including his own, and his plates, such as those in Études sur les Glaciers (1840), were admired by the scientific community. Chromolithography, the printing of each colour of the print using a different stone, was developed commercially from 1850.21

Although lithography was more economical than other printing methods, colour illustrations were still expensive, and the sets of Arctic lithographs ranged in price from Browne’s folio at a cost of sixteen shillings, or twenty-one shillings (‘handsomely bound’),22 to Cresswell’s larger Series of Eight Sketches in Colour, at a price of two pounds, two shillings for the set, more expensive than any written narrative to come out of the search expeditions.23 Inglefield’s large lithographs were offered for sale individually at one guinea (one pound and one shilling) each,24 and May’s Fourteen Sketches were twenty-one shillings (or one pound and one shilling) for the set.25 To put this into perspective, in 1850, a seaman on a sailing ship earned on average forty-five shillings a month, and a printer in London earned thirty-six shillings a week.26

The lithographs varied dramatically in size as well as price; Browne’s averaged about 14 × 20 cm, Inglefield’s 40 × 70 cm, Cresswell’s 40 × 60 cm, and May’s 18 × 30 cm. Although we might assume that the relatively high prices indicate a more elite audience for the lithographs than many of the people who could afford the entry price of one shilling to see the panorama Summer and Winter Views of the Polar Regions, an article in the Morning Chronicle in 1855 noted that lithographs were ‘constantly before the eye of the public’ and ‘almost completely fill the windows of our printsellers’,27 reminding us that they too were part of the Victorian culture of exhibition and were visible to all sectors of society, even if they did not have the means to purchase them. Indeed, when Inglefield’s lithographs were being printed, advertisements in newspapers show that his ‘celebrated pictures’ of the Arctic were on view at Dickinson Brothers for several months.28 The visibility of Arctic prints through their display in printers’ windows and at their establishments indicates a much wider audience for these expensive representations than has generally been assumed.

William Henry Browne’s Ten Coloured Views (1850)

Browne’s Ten Coloured Views marked the beginning of illustrated publications from the search expeditions.29 The work contained a ‘Summary of the various Arctic expeditions in search of Sir John Franklin’ to that date and ten plates of lithographs that represented ‘faithful delineations of the most interesting scenery’30 encountered on the expedition of the Enterprise and Investigator (1848–9) led by James Clark Ross. The list of plates and summary of expeditions were placed before the lithographs, which were captioned with titles. Although the plates were copied from Browne’s work, he was not the author of the accompanying text.31 This text was printed in both French and English; the former was regarded as the international language of science at the time, which would suggest that the folio was aimed at a scientific audience as well as those purely interested in the search. In fact, eight out of the ten plates show an interest in geological features at a time when little was known about the geology of the Canadian Arctic archipelago. The subsequent lithographs of Inglefield, Cresswell, and May were larger and more expensive and, as I will demonstrate later in the chapter, more interested in conveying peril and difficulty. The folio Ten Coloured Views was advertised in the Athenaeum, on 23 February 1850, less than a fortnight after Burford’s panorama had opened, making the two closely linked by Browne’s name and by their timing.32 The advertisement noted too that they were ‘drawn by Lieutenant W. H. Browne, late of Her Majesty’s Ship “Enterprise”’,33 thereby attaching the authority of a reliable eyewitness to the production of the lithographs and implying that they were direct copies of Browne’s work on that expedition

‘Tenfold interest’ attached to Ten Coloured Views on its publication ‘from the uncertainty that hangs over the fate of a brave body of our countrymen, who may even now be living in the desolate regions here depicted’.34 The Athenaeum, in its review of the lithographs, noted the ‘extreme interest evinced by the public at the present moment in all that relates to Arctic Expeditions’.35 The reviewer in the Critic concluded that the ‘portfolio will be a most welcome addition to the drawing-room table. It is the novelty of the season.’36 In common with Summer and Winter Views, reviewers were concerned with the accuracy of the representations, but some regarded the lithographs as being more reliable than the panorama. The Critic noted ‘all who have seen the panorama in Leicester-Square, which was painted from the drawings of the same gentleman, will be eagerly desirous to possess these more probable reminiscences of scenes, which it is difficult for the most vivid imagination to paint’.37 Although the panorama had been lauded for its truth and accuracy, this implies that some viewers still suspected that the deception of the panoramic format might extend to its content, or realised that Burford had used his imagination to transform Browne’s sketches into the panorama. The same reviewer spoke of how Ten Coloured Views derived ‘additional value’ and could be ‘relied upon as exactly truthful’ since they were ‘almost fac similies of sketches taken upon the spot by Lieut. Browne’.38 This suggests the reviewer may, in fact, have seen Browne’s sketches at Ackermann’s. The Art Journal spoke of Browne’s folio as a ‘valuable addition to our knowledge of the Arctic regions’ and considered the views to show ‘much power and truth’.39 The Athenaeum recommended it to those ‘desirous of extending their knowledge of the wonders of the northern seas’.40

However, the reviewer in the Athenaeum remarked ‘Great credit is due to Mr. Haghe for the fidelity and spirit with which he has lithographed Mr. Brown’s [sic] drawings’41 and the title page of Ten Coloured Views stated ‘Drawn by W. H. Browne Esq., Lieut. R.N., Late of H.M.S. “Enterprise”. On Stone by Charles Haghe.’ These acknowledgements indicate that some people were aware of the importance of the role of the lithographer and that it was perhaps not a given that fidelity could be depended upon. Around the same time that the lithographs were being prepared, Browne was writing his letter, printed in The Times, the Athenaeum, and the Literary Gazette, regarding the use of his sketches for Burford’s panorama.42 The letter gave his address as being in Birkenhead, Cheshire, indicating that he did not reside in London and would not have been closely involved with the production of the lithographs.43 The lithographs depicting the Franklin search were sometimes quite different from the officers’ sketches. Artists at printing houses were probably encouraged to make the work of the lieutenants (who after all were amateur artists) more commercial and aesthetically pleasing. Often, this meant heightening the sublime or picturesque effects of a composition even though the lithograph folios, by their very format, suggested accuracy.44 This effect was compounded by the direct association of representations with officers who had participated in the expedition and made on-the-spot sketches.

Browne’s folio of lithographs displays significant scientific, romantic, and commercial registers (such as the lure of the sublime). This complexity results in an uneven adherence to scientific accuracy, although some of the lithographs function as geological records and simultaneously as representations of the sublime. Only three extant works exist by Browne from the Ross expedition (1848–9), and two of these bear some resemblance to two of the lithographs.45 The titles of the lithographs, listed below, betray an interest in geology that seems to have influenced the selection of views to be represented from the expedition. A cursory glance shows that geographical keywords such as ‘glacier’, ‘fiord’, ‘ravine’, ‘cape’, and ‘cliff’ figure prominently.

Ten Coloured Views: List of Plates by William Henry Browne/Charles Haghe

Great Glacier near Uppernavik, Greenland.

Fiord near Uppernavik.

Ravine near Port Leopold.

The Bivouac, Cape Seppings, Leopold Island.

North-East Cape of America, and Part of Leopold Island.

Termination of the Cliffs, near Whaler Point, Port Leopold.

Prince Regent’s Inlet.

Remarkable Appearance in the Sky Always Opposite the Sun.

The Devil’s Thumb.

Noon in Mid-Winter.

Fortunately for the lithographer Charles Haghe and the publishers Ackermann, the Ross expedition wintered at Port Leopold, on the north-east of Somerset Island, an area of high sea cliffs and ravines, meaning that the topography included features associated with the sublime and thus negated the need for extreme exaggeration on the part of the printers. The plateau of Somerset Island, which consists of limestone and sandstone, ranges in elevation from three to six hundred metres and is cut by steep-sided river valleys.46 The majority of the ten lithographs depict scenes of the north-west coast of the island, where they spent a prolonged amount of time.

Geology was one of the sciences that had the potential to capture the public imagination, and constant debates over geological theories during the nineteenth century stimulated the public appetite for novelty and knowledge. Seminal texts, such as Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830–3), Louis Agassiz’s Études sur les Glaciers (1840), Hugh Miller’s The Old Red Sandstone (1841), and Humboldt’s Cosmos (1848) popularised geology in both public and scientific realms.47 Certainly, the library of the Assistance in 1852 included Cosmos and Principles of Geology as well as Henry De la Beche’s Geological Manual (1831), William Buckland’s Geology and Mineralogy (1836), and four other unspecified geological books.48 It is likely that Browne had access to a similar selection of geological texts during the voyage of the Enterprise and the Investigator from 1848 to 1849.

William Henry Browne had spent his childhood on the rocky headland of Howth in Ireland; one could suggest that this environment was the very place that influenced his choice of subject matter, the representations of geological features, which are so often the focus of his Arctic sketches. The peninsula of Howth Head is north-east of Dublin city, connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land, and many parts of the coast consist of exposed rock and cliffs. From the harbour master’s house in which he grew up, he would have looked out on the island of Ireland’s Eye, where bare rock of sandstone, quartzite, and greywacke is exposed and meets the sky in places.49 The entire island ‘displays some of the best exposures of Cambrian rocks on the east coast of Ireland’.50

Browne’s sledge journal from his second expedition shows a good knowledge of geology and observational skills, as he correctly identified rock types that he encountered in 1851 on the Austin expedition. He fulfilled many of the criteria for a geological observer as laid out by Darwin in The Admiralty Manual and identified limestone, sandstone, conglomerate, and granite on his sledge journey, noting aspects such as possible coal deposits, stratification direction, the heights of headlands and cliffs, and the colours and textures of rock. He included a separate piece in his journal on the topography and geology of the area he traversed, whereas other sledge leaders who were also good artists, such as George F. McDougall and May, hardly mention the geology of the land they pass through.51

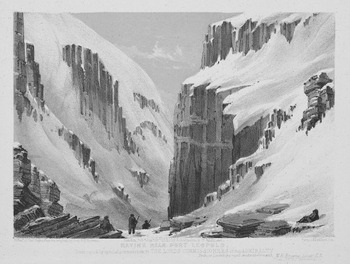

One of the most popular lithographs, The Bivouac, Cape Seppings, Leopold Island (Figure 5.1), represents a sledge party beneath the cliffs of Cape Seppings on Somerset Island. The human figures act as a scale, giving the viewer an idea of the size of the geological form, and the delineation of the cliffs demonstrates an understanding of the sedimentary geology. There is no similar sketch by Browne in the archive, but twenty-first-century photographs of the area show a formation remarkably similar to that depicted in the lithograph. An examination of topographical maps confirms that the cliffs at Cape Seppings rise to three hundred metres and are not actually vertically exaggerated to convey the sublime in the lithograph. Despite this, the sublimity of a large geological mass that reduced the search party to minuscule figures was not lost on the Art Journal, whose reviewer commented on the ‘savage grandeur’ and ‘sublimity about some of these scenes, of a very striking kind’, singling out The Bivouac as an example.52

In the bottom-left corner of The Bivouac, two figures apart from the main group are seen, indicating the scientific observer/artist and his companion. Other figures have arrived and are resting, unloading sledges, gathering around a fire. Although the presence of the expedition members beneath the sheer cliffs registers the sublime, their activities at the place of rest are less arduous than hauling the sledges. Moreover, the two observers, who are at ease in the environment, present a contemplative stillness and not a battle with nature. Their presence suggests a Romantic influence, urging a reconnection with nature and an engaged interest in the environment. This is not a sublime in which ‘terror’ or ‘pain’ indicative of the Burkean sublime are explicitly represented. The attribute of ‘bodily pain, in all the modes and degrees of labour, pain, anguish, torment … productive of the sublime’ is lacking.53

This Burkean sublime does creep into the lithograph Prince Regent’s Inlet (Figure 5.2), which may be based on one of Browne’s three extant works from the Ross expedition, Coast of N. Somerset – Regent’s Inlet (Figure 5.3).54 In the latter, two observers in the landscape fulfil a number of functions: they provide a scale for the geological features; they signify scientific authority implied by representing the act of observation and on-the-spot drawing; they act as witnesses, implying truth. Furthermore, the figures could be interpreted as the Rückenfigur, which sought to draw the viewer into the painting and into appreciation of nature,55 familiar from the work of the German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich. This connection of science with romanticism, including its use of figurative language, was commonplace in the nineteenth century, particularly in the study of ice and glaciated landscapes.56

In contrast, the lithograph Prince Regent’s Inlet (Figure 5.2) shows a very different scene.57 At first glance, the watercolour and the lithograph appear to have little in common apart from the place name in their titles. On closer inspection, it becomes evident that the lithograph is compositionally almost a mirror image of the watercolour and may also present the view from a different angle. Noticeable too is the way in which enormous quantities of snow lie heaped up in the lithograph, in contrast to the relatively light layers of snow in the watercolour. The blue sky of the watercolour has disappeared, replaced by a stormy and ominous backdrop, as have some details of geology. The tiny man-hauled sledges are starkly obvious in the right-hand corner of the lithograph, highlighted against the white snow. Although two figures still sit (bottom centre) and observe in the lithograph, their presence is almost lost in the shadow of the cliffs. Furthermore, the lithographer has made the geological features here seem larger, showing that a heightening of the sublime must have occurred in some of the plates. The tension here between scientific accuracy and commercial interests comes to the fore, as a more threatening Arctic comes into view.

Few of Browne’s lithographs show the struggle that becomes more pronounced in the later lithographs of Cresswell and May, where the heroic self-sacrifice of the search is made clear. Certainly, the figures at ease in the environment in Coast of N. Somerset – Regent’s Inlet, and in some of Browne’s lithographs, would seem to suggest contemplation rather than action. Nowhere is this more evident that in the lithograph Ravine near Port Leopold (Figure 5.4). The seated figure on the left is offset by a reclining figure in the right-hand corner, who contemplates the scene in a Romantic pose. The figure on the left, probably intended to be the artist, sits and observes; two figures enter the ravine itself, unencumbered by sledges or supplies; their objective appears to be daily exercise and exploration of their local environment. According to the Critic, Ravine near Port Leopold was a scene ‘to which the Alps afford no parallel’.58 This comment, however, reminds us of the association of the Alps and Romantic scenery; the reclining figure brings to mind the tourism for which the Alps became known in the late eighteenth century. Indeed, around the mid-nineteenth century, growing tourism and mountaineering in the Alps attracted observers who peered at climbers through telescopes from the comfort of hotels.59 These spectators were particularly interested in dangerous ascents, where there was a possibility of watching the climbers confront death.60 However, in Ravine near Port Leopold, there is no sense of imminent death or disaster in the relaxed figures that people its lower portions, and the contents of the representation suggest an incompatibility with the apprehension of the Burkean sublime.

Figure 5.4 William Henry Browne, Ravine near Port Leopold, 1850. Lithograph, 12 × 17.5 cm.

The choice of subject matter in the lithographs was surely influenced by several factors: Browne’s interest in geology fostered by his background; the location of winter quarters near the impressive sea cliffs of Somerset Island providing a local environment of immense geological forms for a large part of the expedition; a possible interest in Romantic landscape painting; and the publisher’s and the Admiralty’s choice of what sketches to produce as lithographs and how much to alter them. Browne’s lithographs remain complex documents that illustrate simultaneous registers of scientific accuracy and lithographic exaggeration. While Browne’s own Romantic response to the environment did not preclude his accurate recording of topography and geology, traces of this may be seen in the relaxed observers that appear in both his watercolour from the Ross expedition and the subsequent lithographs. These remnants, seen in the calmness of some of the figures that disrupt the portrayal of the ‘inhospitable land’,61 still give a sense of Browne’s ‘conversation’ with the land, despite the mediation of the lithographer Charles Haghe, the publisher Ackermann, and the Admiralty. However, the lithograph Prince Regent’s Inlet (Figure 5.2) points towards what would become the more typical lithographic representation of the search, with labour, difficulty, and the immensity of nature emphasised in the prints of Inglefield, Cresswell, and May.

Samuel Gurney Cresswell’s Series of Eight Sketches in Colour (1854)

Cresswell first served on the Investigator during the Ross voyage of 1848 to 1849 (the same voyage during which Browne was on the Enterprise) and subsequently as second lieutenant, again on the Investigator, as part of Robert McClure’s expedition, which entered the Arctic via the Bering Strait in 1850 and did not return until 1854. The expedition sighted the last link of the Northwest Passage early on and spent three winters in the region of Banks Island, eventually abandoning the ship to the ice and crossing the remaining section of the Northwest Passage on foot and by sledge, in order to reach the ships of the Belcher expedition.62 Although McClure and most of the crew were unable to reach England until October 1854, the news of the discovery and traversing of the Northwest Passage was brought to England by Cresswell himself after he arrived, with McClure’s despatches, in Britain on Inglefield’s supply ship the Phoenix in October 1853.63

Unlike Browne’s lithographs, in the case of Cresswell, we are fortunate in having access to a large selection of his paintings created during the two Arctic expeditions in which he participated.64 Thirty paintings and sketches exist by Cresswell that are dated to the first voyage, and twenty-three pictures date from the second Investigator voyage. Several of these latter pictures are directly comparable with some of the lithographs in Eight Sketches, showing stark differences between the sketches and their respective prints.

Reviewers were, once again, concerned with the accuracy of the representations. Referring to the published lithographs, the reviewer in the Art Journal considered that ‘Lieut. Cresswell’s masterly sketches are powerful aids in enabling us to form a tolerably accurate notion of the hazards of an Arctic expedition’.65 The reviewer also found space to note how they were ‘excellently lithographed’ by William Simpson and Edmund Walker (whose names also appear on individual lithographs) and the printers Day and Son. All in all, they considered them ‘a series of interesting views’ as well as ‘beautiful works of Art’.66 A reviewer in the Morning Chronicle, on the occasion of the publication of the second edition the following year, considered that the ‘whole of the views are exceedingly interesting, they are lithographed in the highest style of art, and their accuracy is vouched by the name of Lieutenant Cresswell, whose rare abilities as an artist we have had occasion more than once to acknowledge’.67

Conversely, the Athenaeum was less than complimentary in its review. By opening with the phrase ‘These interesting sketches seem faithful, though not very artistic’, the reviewer questioned not only the artistic merit but also the accuracy of the representations. The cautious choice of the word ‘seem’ casts some doubt on the prints’ fidelity to nature. Furthermore, the reviewer lamented the ‘heavy’ colouring and the ‘want of delicacy in detail, which is peculiarly felt in snow scenes, where the tints are so soft and evanescent’.68 The review continued: ‘The variety of surface is not conveyed to the eye, and the result is an appearance of inaccuracy which we are sure does not exist.’69 The unusual and enigmatic remarks undermine the lithographs’ intent as convincing representations and are intriguing in light of comparisons with Cresswell’s sketches, which indicate that much of the detail of the scenery relied heavily on the imagination of the lithographers Simpson and Walker.

Cresswell himself revealed that he struggled with his drawing, suggesting that he did not think of himself as an artist; in July 1848, he wrote to his parents from the Whale Fish Islands, Greenland, lamenting that he was experiencing difficulty: ‘I have taken great pains with my drawing since I have been away and the more I try to draw, the more I am sure I have no taste for it. I will do my best.’70 Indeed, his work from both voyages shows a laboured stiffness (noticeable all the more for its absence in the work of Browne and May) that reveals his frustration and lack of confidence in drawing, particularly with the human figure and with perspective.

The eight prints show specific and significant events relating to discovery and danger: headlands, the lone ship in a ‘critical position’, a storm, a sledge party setting out on what would be the completion of the Northwest Passage, the intense labour of sledging. Their titles, listed below, focus on the actions of the expedition and the movements of the ship. In this way they tell a specific narrative of exploration, one that did not include representations of leisure or inactivity.71

A Series of Eight Sketches in Colour: List of Plates by Samuel Gurney Cresswell / William Simpson and Edmund Walker

I First Discovery of Land by H.M.S. Investigator, September 6th 1850.

II Bold Headland on Baring Island.

III H.M.S. Investigator in the Pack. October 8th 1850.

IV Critical Position of H.M.S. Investigator on the North-Coast of Baring Island. August 20th 1851.

V H.M.S. Investigator Running through a Narrow Channel in a Snow Storm between Grounded and Packed Ice. September 23rd 1851.

VI Melville Island from Banks Land.

VII Sledge Party Leaving Mercy Bay, under the Command of Lieutenant Gurney Cresswell. 15 April 1853.

VII Sledging over Hummocky Ice. April, 1853.

In contrast to the lithographs, one of Cresswell’s paintings from the voyage, Brown’s Island, Coast of America (Figure 5.5), shows men scattered about in a relaxed manner under a blue sky in August 1850.72 The painting reflects the periods of inactivity that were inevitably typical of search expeditions. In the foreground of this painting, a figure reclines (bottom left) while, nearby, two sailors light their pipes; other groups of men stand around, close to the partly concealed ship. The scene has an air of quiet joviality and restfulness, not commonly seen in the public representations. The lithographs instead highlight discovery and difficulty, new lands, and the ship in peril. The first lithograph in the series immediately opens with a ‘discovery’. First Discovery of Land by H.M.S. Investigator, September 6th 1850 (40.5 × 55.9 cm), lithographed by Simpson, sets the tone for the entire production. In this plate, the water is black, only serving to make the novel ice stand out more, while the land in the distance is overshadowed by an ominous sky of dark clouds. The scene is melancholy, suggesting perhaps difficulties to come as the Investigator, alone under a threatening sky, weaves her way through ice floes seemingly impossible to navigate.

A sketch exists by Cresswell entitled Discovery of Barings Island September 6th 1850 (15.3 × 25.1 cm).73 In this monochrome sketch, the composition is broadly the same as in the lithograph, with the shape of the ice in the foreground clearly transferred from sketch to print, although the ship is significantly larger in comparison to its environment. The accomplished lithographer William Simpson,74 who became a professional artist shortly afterwards, has used his imagination to elaborate considerably on the details, creating something aesthetically pleasing out of Cresswell’s rudimentary sketch. The reduction of the size of the ship, making the environment appear more overwhelming, is evident in all of Cresswell’s lithographs where comparative drawings are available. A reviewer described the print thus: ‘the little vessel is making its way through a vast field of broken ice, and beneath a sky so heavy with snow-clouds as to overwhelm the ship’,75 echoing the uneven battle of ship versus Arctic nature. In this combat between mismatched foes, it was then no fault of the British Navy if they lost, and it became a tribute to the ‘stern courage and resolution’ of those ‘iron-hearted and iron-framed men’76 if they triumphed.

It is unsurprising, then, that two plates (III and IV) show the Investigator keeling over dramatically in the ice. Both plates were published individually on 15 May 1854, before appearing as part of the set on 25 July 1854. The Athenaeum was no doubt referring to these plates when it commented: ‘The few notes of the letterpress convey a forcible impression of the dangers and peculiar perils of Arctic voyaging; the heavy floes that crush a ship as if it were glass, or “nip” it into a shapeless heap of broken timbers.’77 The third plate, H.M.S. Investigator in the Pack. October 8th 1850 (Figure 5.6), described as a ‘moonlit scene rendered with great power’ in the Art Journal,78 shows the position of the ship in the ice in October 1850, the first winter that the Investigator spent in the Arctic during McClure’s voyage. The plate was lithographed by Edmund Walker and shows a scene that is almost Gothic in its rendering of the ice, with the ship’s inner light glowing, reflected on the ice beneath a stormy sky; the half-concealed moon glimmers off the ice pack that itself displays striking contrasts of dark and light. The ice pack, eerie, glassy, indeed lurid, appears impossible to navigate either by ship or on foot, and no figures here leave the precarious safety of the vessel.

One of Cresswell’s sketches, Position of H.M.S. Investigator after Heavy Pressure 1852 (24.4 × 31.8 cm), looks similar in composition to H.M.S. Investigator in the Pack and may have been the inspiration, even though the print claims to show a scene from two years earlier.79 Yet, in the monochrome sketch, probably indicative of the only materials then available to Cresswell, two or three comparatively large figures walk on the ice, which appears more stable than in the lithograph. In the latter, the glow of light coming from the ship points to a spark of humanity that poignantly highlights the inhuman aspects of the ice pack.

The scene was also portrayed in one of Inglefield’s lithographs, which he had published well before Cresswell’s were printed and shortly after they both returned to Britain in October 1853 on the Phoenix. Four of the lithographs taken from Inglefield’s watercolours were advertised as being in press at the end of October 1853.80 These prints were promised to be ‘of large and imposing proportions’.81 The first of Inglefield’s lithographs, The Perilous Situation of H.M.S. Investigator, while Wintering in the Pack in 1850–51, was ‘taken from a Sketch by Lieut. [S.G.] Cresswell’, and bears a resemblance both to Cresswell’s sketch and to the lithograph H.M.S. Investigator in the Pack.82 It is likely that both lithographs derive from the same sketch mentioned above, Position of H.M.S. Investigator after Heavy Pressure 1852. In both of the prints, the ship is considerably smaller than in the sketch and the icescapes are devoid of any outward human presence, excepting the ship (and a minuscule figure on board in Inglefield’s version). The small size of the ship and the lack of people emphasise the immensity of nature in a way that Cresswell’s sketch does not. Unlike in the sketch, the ice surrounding the ship appears completely unnavigable on foot, adding to the popular idea of utter imprisonment by ice. Furthermore, a type of ‘against all odds’ scenario is set up, during which the discovery of the Northwest Passage appears all the more impressive. The order of the prints in Eight Sketches, which otherwise follow a chronological sequence, suggests that the discovery (Plate VI) happened after the ship spent two winters in the Arctic, when in fact the expedition established the existence of the passage in October of the first year (1850).

The fourth lithograph in Cresswell’s series (see Figure 0.2) is perhaps the most reproduced image of the nineteenth-century Arctic in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; in particular, it is a popular choice to illustrate book covers on any aspect relating to the Franklin expedition and the searches.83 It again shows the ship trapped in an immensity of ice the following year. Lithographed by Simpson, Critical Position of H.M.S. Investigator on the North Coast of Baring Island, August 20th 1851 represents the vessel in an alarming position, appearing as though it might become crushed between masses of ice. Small figures are scattered on the ice that appears to crush the ship; some try to secure the ship to the ice while others may be placing gun powder in the ice in order to weaken it.84 The reviewer in the Art Journal noted that ‘the ship is imbedded between two enormous floes of ice as if they would crush her; this must have been a time of terrible anxiety to the navigators’.85 We have no sketch from Cresswell dated 20 August 1851; neither is any surviving one similar to this lithograph. We do have access to several written accounts of events on this day, which describe how the Investigator was sailing between pack ice and land along the north shore of Banks Island. Whether the lithograph was actually representing events of 20 August is a matter of conjecture. Accounts in published narratives remind us that memory is fluid.86 Johann Miertsching, the interpreter on the Investigator, makes no mention of the specific event represented in Plate IV, only noting on that day that ‘she was anchored to a great stranded flow [sic] in the hope of pressing on to the east when the next friendly land-wind pushed the ice back from the shore’.87 McClure writes in his journal that on 20 August they ‘secured to the inshore side of a small but heavy piece of ice, grounded in twelve fathoms, seventy-four yards from the beach’ as protection ‘against the tremendous polar ice’. By evening, they were ‘in a very critical position, by a large flow [sic] striking the piece we were fast to, and causing it to oscillate so considerably that a tongue, which happened to be under our bottom, lifted the vessel six feet’. The ‘conflict continued for several minutes’ when the large floe was ‘rent into pieces’ and the ship was ‘driven nearer the beach’.88 Alex Armstrong, the ship’s surgeon, who used the lithograph as the frontispiece for his narrative, did note that on 20 August ‘the ship’s safety was suddenly threatened by a commotion in the ice … and now rendered our situation one of extreme danger’.89

Shortly after Cresswell arrived back in England, the Illustrated London News printed three engravings of his sketches with a summary of McClure’s narrative of the voyage. They presented ‘graphic and truthful pictures of adventures in the dreary, ice-bound regions of the Polar seas’, as well as being ‘illustrations of events described in Capt. McClure’s despatches’.90 One of the engravings, Critical Position of ‘The Investigator’, at Ballast Beach, Baring Island (Figure 5.7), bears a strong resemblance to the ever-popular fourth plate in Cresswell’s series, Critical Position of H.M.S. Investigator (Figure 0.2).

The treatment of the sea ice differs in each, with the ice in the lithograph presenting a more vertical aspect reminiscent of icebergs in the eastern Arctic. However, both pictures show the ship in a very precarious position, and the existence of the engraving, printed within a few weeks of Cresswell’s arrival in England, suggests that he did paint a scene of Ballast Beach, which may now have become lost or separated from the collection of paintings held by Norfolk Record Office. The Illustrated London News explained that this engraving showed where the Investigator was frozen up from 20 August to 11 September 1851.91 It includes an extract from McClure explaining the situation (as above) when on 29 August ‘a large floe, that must have caught the piece to which we were attached under one of its overhanging ledges, raised it perpendicularly thirty feet, presenting to all on board a most frightful aspect … This suspense was but for a few minutes, as the floe rent.’92

However, a sketch by Cresswell does exist of the Investigator some weeks later in a position of difficulty, entitled Position of H.M.S. Investigator, Sept 19, 1851 (17 × 24.5 cm).93 Here, the ship is being forced at an angle by the sea ice, and men are anchoring her to a floe. The ice is in no way as high as it was represented in either the lithograph or the engraving. In fact, none of Cresswell’s paintings from the voyage shows ice as high and vertiginous as in the two prints. Cresswell’s sketch shows the figures, who anchor the ship to a grounded floe, in the foreground of the scene, making them much larger than they appear in the prints when they retreat to the background of the scene, appearing tiny and helpless, although they too are engaged in securing the ship to the ice. The figures in the sketch appear to be more in control of the situation.

Armstrong recounts that this day was filled with apprehension, when masses of ice lifted the ship fourteen inches out of the water while she was anchored to a large floe. The continual assault of the ice ‘presented a prospect of peril’ throughout the day.94 It is interesting too that the sketch is simply entitled Position of H.M.S. Investigator, Sept 19, 1851, whereas the lithograph and engraving captions have prefixed the word ‘Position’ with ‘Critical’, emphasising the danger for readers. Inglefield’s lithograph too, made use of the descriptor ‘Perilous’ in the title, thereby also clarifying the strong possibility of the wreck of the ship for the viewer.

Reviewers were concerned with accuracy and truth; for the most part, the lithographs carried an almost irrefutable stamp of authority. Cresswell’s substantial archive indicates that visual records could be transformed through lithography, with Simpson and Walker having to fill in detail where none existed. The selection of his work chosen for printing was judicious, displaying themes of discovery and danger over any other aspects of the Arctic expedition. Material showing sailors who might appear to be lounging about, instead of gallantly striving to rescue the lost expedition, was not suitable for publication. Furthermore, Cresswell’s departure for the Baltic shows that these amateur naval artists were not necessarily able to oversee the production of lithographs from their work. Lithography artists were excellent artists in their own right; shortly after working on Cresswell’s prints, Simpson became a pioneer war artist in the Baltic, and thereafter Queen Victoria regularly commissioned his work.95

Walter William May’s Series of Fourteen Sketches (1855)

When Walter May returned to the Arctic as lieutenant on the Assistance as part of the Belcher expedition of 1852 to 1854, it was his second expedition in search of Franklin.96 He illustrated the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette’97 (as discussed in Chapter 2) and also undertook other drawing as a pastime during the voyage. Some of his drawings from the Belcher expedition were subsequently published as a folio of lithographs on 1 May 1855, showing ‘fourteen most interesting and carefully-finished sketches’.98 May ‘intended to illustrate a few of the principal events and features’ of the expedition, including ‘some in a picturesque point of view, and others to illustrate “Arctic Travelling”, which though ably explained to the public in other works, has not yet been produced as one of the principal objects in a series of Sketches’.99 In his use of the term ‘picturesque’, he here signals the hope that the prints will be aesthetically pleasing, appeal to a broad audience, and not just tell a narrative of the expedition.

A close study of May’s drawings, and the lithographs derived from them, reveals the ways in which the Arctic presented to the public subtly changed once it arrived in Britain. By examining the lithographs, their written descriptions by May, and his drawings and paintings in the Arctic, we see the Arctic change into a darker, more sublime space, particularly in the prints that illustrate ‘Arctic Travelling’, than the one initially represented by May in other formats. While the prints are clearly different from the drawings, the form of their differences changes the depiction, and meaning, of the Arctic in several ways. More specifically, the printed and published Arctic became more physically difficult and inhuman, more imperial and exotic, than the Arctic depicted in the sketches and watercolours.

Although the lithographs show a struggle of heroic failure, other sources indicate that May was enthusiastically immersed in, and at ease with, Arctic life. His drawings, his own journal, and his appearances in other texts reveal much of a personal connection to the Arctic.100 All the work discussed below is drawn from May’s second Arctic voyage, when he acted as lieutenant on the Assistance under the notorious Edward Belcher from 1852 to 1854. May’s own drawings and watercolours, from which the lithographs are derived, show a far more cheerful Arctic than the one we see in print.

The Belcher expedition had many fine, clear days in its first winter quarters, despite being one of the farthest north of all the search expeditions, and May made the most of this, even drawing outside in winter, commenting that ‘the weather being so fine with no wind we do not feel the cold’.101 This fine weather made it possible for the expedition members to spend time outside, exercising, hunting, and recording meteorological phenomena in winter. It also facilitated enjoyment and appreciation of the environment. Nowhere in May’s personal journal does one get a sense of imprisonment in the Arctic winter or the alienation and loss of self that is associated with the negative sublime. However, the lithographs that were published after his voyage would be appreciated, one reviewer felt, as a record of ‘undaunted bravery and heroic perseverance under difficulties of no ordinary nature’.102 May himself eschewed hyperbole and the language of the sublime in his text, writing in an unadorned style without exaggeration: ‘Among the plates I shall now try to give a truthful description of the mode we pursued in Arctic Travelling.’103 He also fails to use the word ‘exploration’, instead choosing the more ordinary term ‘travelling’.

May’s folio of lithographs, A Series of Fourteen Sketches, was published by Day and Son on 1 May 1855 at a cost of twenty-one shillings (or one pound and one shilling).104 The folio includes a list of subscribers of 240 names.105 Some subscribers ordered more than one copy, leading to a total production (as per the list) of 259 copies. Almost one-quarter of the subscribers were women, indicating a significant female interest in viewing and owning representations of Arctic exploration at the time. The following list details the titles of the plates in the folio and shows their focus on ships and sledges.

A Series of Fourteen Sketches: List of Plates by Walter William May/Day and Son

I.— The Arctic Squadron in Lievly Harbour, Island of Disco, West Coast of Greenland.

II.— Loss of the McLellan.

III.— H.M.S. Assistance and Pioneer in Winter Quarters – Returning Daylight.

IV.— H.M.S. Assistance, in Tow of the Pioneer (Captain Sherard Osborn), Passing John Barrow Mount, North of Wellington Channel, 1853.

V.— H.M.S. Assistance and Pioneer fast to the floe, off Cape Majendie, Wellington Channel, 1853.

VI.— Perilous Position of H.M.S. Assistance and Pioneer, on the Evening of the 12th of October, 1853.—Disaster Bay.

VII.— H.M.S. Assistance and Pioneer Breaking out of Winter Quarters, 1854.

VIII.–IX.— Division of Sledges Finding and Cutting a Road through Heavy Hummocks, in the Queen’s Channel.

X.— Division of Sledges Passing Cape Lady Franklin; Extraordinary Masses of Ice Pressed against the North Shore of Bathurst Land.

XI.— Sledges in a Fresh Fair Wind, Going over Hummocky Ice.

XII.— Encamping for the Night.

XIII.— Sledge Party Returning through Water during the Month of July.

XIV.— Relics Brought by Dr. Rae.

A number of unique drawings exist that can be shown to be prototypes of the published prints. Several of these are in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, but similar themes can be found in illustrations by May in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’, and additional drawings by him exist that could also have been prototypes for the lithographs. A set of drawings that provides the prototypes for three of the six lithographs concerning sledge travel was likely to have been made after the voyage.106 In the first instance, they are done on paper imprinted with Ackermann’s name. The paper is clean and undamaged, unlike the material made in the Arctic that tends to be worn, folded, or marked, reflecting its contextual origins. Furthermore, pictures done in the Arctic tend to be on varying sizes of paper, their makers using whatever was available to them at the time. These three drawings are done on approximately the same size paper (27 × 35 cm).

In addition, the way in which May writes about the plates in the published folio often indicates that some drawings were created after the event, probably in England. These ‘Arctic Travelling’ scenes may have been included at the suggestion of another agent. Their use of the same paper, stylistic differences, and medium marks them out as separate from the rest of May’s work. In plates I to VII, May is explicit in stating the pictures’ origins. For example, in IV.—H.M.S. Assistance, in Tow of the Pioneer, May tells us that the ‘sketch was taken on one of those beautiful calm evenings’.107 Indeed, a worn and well-travelled watercolour exists in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, that shows a similarity to the lithograph.108

In the drawings and lithographs, the actions, facial expressions, and even the number of figures convey different versions of Arctic exploration. The presence of human figures in many of May’s sketches and lithographs provides a barometer of change as representations went through processes of transformation. In XIII.—Sledge Party Returning through Water in the Month of July, certain aspects of the composition change between painting and print.109 May tells the reader in his account of the drawing: ‘The Sketch in this Plate is intended to represent Captain Richards’ party returning across Byam Martin Channel, in the month of July. They are supposed to be bringing the Pioneer’s ice-boat from Melville Island, two hundred miles from the ship, where she had been placed by one of his depot sledges in the spring.’110

May is clear here that in fact this is an imaginative composition, based on his knowledge of travel and the ice. The plate is ‘intended’ to represent a scene and the figures are ‘supposed’ to be doing a certain activity. Despite this, it was felt necessary by someone to heighten May’s composition to affect a more sublime Arctic. Both the watercolour by May and the subsequent lithograph show the unpleasant work of hauling a sledge through the meltwater that forms on sea ice during the summer period. Although the lithograph is far more dramatic in many ways, from the angle of the boat to the setting sun,111 the focus here is on the first figure pulling the sledge in both pictures, and it is obvious that the printed version shows a figure engaged in a far greater struggle, with his back bent at such an acute angle.

This would seem to suggest a great war is being waged against the ice in order to find Franklin and that everything humanly possible is being done in the Arctic search. This tendency to exaggerate the angles at which figures strain to pull a heavy load over the ice is also seen in other lithographs of the set, for example in II.—Loss of the McLellan and IX.—Division of Sledges Finding and Cutting a Road through Heavy Hummocks. The figures show a valiant struggle wholly compatible with the idea of ‘gallant’ crews striving to conquer the Arctic.

But it is not just the angles of the figures that change, their faces can also be transformed in the printed material. The lithographs do not show facial expressions in the same way as source drawings or watercolours. An examination of the watercolour Loss of the McLellan (1852) and the lithograph II.—Loss of the McLellan (1855) also reveals subtle yet important differences, although at first glance the two pictures appear to be quite similar.112 The ships in both remain in much the same places and at the same angles; the boats in the foreground too seem to mimic each other; the horizon line is unchanged.

Once again it is evident by noticing the angles of the figures that those in the watercolour (31.6 × 46.7 cm) are not struggling to the same degree as the ones in the published lithograph. This includes the smaller figures in the background. However, looking more closely at the watercolour (Figure 5.8, top), we can see smiling expressions on the two men who face the artist as they heave the boat over the ice; one of them, distinctly comical with a red nose and what seems to be an eyepatch, looks right at the artist. These faces show a very human and personal Arctic, whereas the lithograph, with its hidden faces, projects a depersonalised context, making it less of a place, with its own community, and more of a space with which to battle. Indeed, it is rare to find any facial expression in published individual prints of the Arctic, although on-board newspapers are full of smiling faces that can be seen in the Illustrated Arctic News and in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’.

While the loss of a ship in the ice may sound catastrophic, in this case the crew, who were surrounded by relatively stable ice in Baffin Bay and a large amount of whaling ships as well as the search expedition, were easily rescued. The McLellan was in a far better position than trading and passenger vessels much further south in the summer of 1850 that ran into icebergs in the Atlantic. For example, Irish newspapers reported the destruction of fourteen vessels and the loss of over one hundred lives, many of whom were on an unidentified vessel (reported to have been from Derry) sailing to Québec that sank amidst the ice over several days. Although ice was generally watched out for in the Atlantic in April and May, owing to the spring break-up of the Arctic seas, the year of 1850 was exceptional and the ‘floating fields of icebergs’ were ‘immense’. ‘Subsequently a great many bodies were seen intermingled with the ice, together with some portion of the cargo.’113 Such a tragedy shows that any seafaring, not just Arctic exploration, was a risky business in the nineteenth century (as indeed it can still be today). In sharp contrast, May’s textual description of this plate in his folio relates that ‘the Sketch was taken when the men were deserting the wreck; some were launching their boats to a place of safety. Boxes, beds, casks, clothes of every description, were scattered about the floe. It formed a most animating scene, and made a capital subject for a picture.’114 Although May does not register any sense of danger in the accompanying text, which makes more sense when viewed in conjunction with the happier figures in the watercolour, the plate shows a far more threatening Arctic epitomised by the labour and struggle of the men. McDougall, too, noted the implausibly relaxed attitudes and the peculiarity of this scene: ‘It was novel, but interesting, to gaze on so many vessels in a state of utter helplessness, careening and fouling each other in every possible direction, whilst their crews, standing beside their boats and clothes on the ice, smoked their pipes like perfect philosophers.’115 The incident also appears pictorially on the front page of the January 1853 issue of the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’, entitled A Nip in Melville Bay.116 In the magazine, the account of the incident beneath refers to the picture as being ‘the next in our picture gallery’, which somewhat trivialises the incident. However, Sherard Osborn reveals that ‘Piling the agony! might we feel be pardonable in such a case, but that has so often been already done, in all connected with Polar Voyages, that we shall endeavour to give a … matter of fact account.’117 In May’s pen and ink picture in the on-board periodical, the individual men with their possessions are foregrounded, and the pulling of the boat is relegated to the background. In fact, the entire Belcher expedition, consisting of five ships, witnessed the loss of the American whaling ship, the McLellan, to the ice pack off the west coast of Greenland, and the incident was recorded visually by several expedition members. The shipwreck took place over a period of ten days in July 1852, and May’s entries in his journal over the extended period are factual and calm, showing no trace of astonishment or awe associated with the sublime. In fact, with the ships docked in the ice, he spent time trying to prepare paper for the calotype, an early photographic process.118

In the same way that the panorama peopled its Arctic with frenzied activity to imply the large number of men engaged in outdoor ‘manly’ pursuits, some of May’s lithographs, too, increase the number of human figures. The sketch for IX.—Division of Sledges Finding and Cutting a Road attributed to May is one of the three sketches mentioned above. It has the appearance of being produced directly for the purpose of preparing a lithograph and is part of a set of similar drawings that are all done in the same medium, on the same paper, which is embossed with the name of the lithography company ‘Ackermann & Co.’ It is clear that five extra figures were added into the sketch by using a hard pencil as opposed to the chalk pastel used for the rest of the scene. In particular, two of the added figures stand on a height gazing out over a vast landscape, suggesting an unexplored space beyond and a mastery of the landscape that could be possible through labour and struggle.

When May’s drawings were reinterpreted as lithographs, it was not only human forms and faces that changed; the landscape was also altered and intensified. It was through the landscape that the sublime associations of the Arctic could be conveyed and popularised most effectively by drawing on Romantic and Gothic traditions. By comparing another preparatory drawing attributed to May, Division of Sledges Passing Cape Lady Franklin, with the corresponding print from 1855,119 we observe how the printed landscape has sharper peaks and high contrasts, reminiscent of the treatment of Browne’s landscapes in the panorama. This published version shows a landscape that is altogether darker and more threatening, with its backdrop of gathering storm clouds. A closer look at the drawing also reveals the smiles on all three visible faces in the drawing (Figure 5.8, bottom), which recall the smiling faces in the watercolour Loss of the McLellan. The figures in the drawing are, without exception, turned towards their partners, reminding us of the camaraderie, humour, and enjoyment experienced in the Arctic environment. Those in the lithograph, however, are more engaged with the struggle of their endeavour, presenting a darker face and anonymity, a loss of self in the Arctic.

It was unsurprising then that the Morning Chronicle’s reviewer of the lithographs could only see the ‘intense misery, the excessive labour, and the constant perils which the naval heroes who have adventured into those frozen latitudes have been compelled to undergo’.120 The lithographs correspond with what was being written in the media about the expeditions, and the prints match the image of the search for Franklin as a trial of difficulty and self-sacrifice in a way that smiling faces in sketches, paintings, and drawings did not. Like the labourers in early nineteenth-century English landscape paintings, these industrious men have become reassuring representatives of the moral character of their country.121 In fact, the lithographs suggest the nobility of the moral sublime even more forcefully than it had appeared in the panorama Summer and Winter Views of the Polar Regions.

Given that May’s folio intended to represent Arctic modes of travelling, it is noticeable that no sledge dogs are included in the plates. However, the Belcher expedition regularly used dogs for pulling the sledges, particularly when travelling between the Assistance and the Resolute, and several men became adept dog drivers.122 During the second winter, the route from the Assistance near Cape Osborn to the North Star at Beechey Island, a distance of around a hundred kilometres, was travelled repeatedly by dog sledges that were used as ‘express couriers’.123 Their absence in the lithographs is striking, and the reasons for not including them are puzzling. Perhaps whoever was influencing the publication of the lithographs did not think that the dogs portrayed the right message. The dogs do appear on two occasions in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’, pulling a sledge driven by a man in the small pen-and-ink Snow Carriers,124 and four dogs take centre stage in a watercolour (16 × 23.5 cm) attacking a bear that May shot during the first winter.125 This exclusion of the dogs from the lithographs (none of the lithograph folios shows them) has left the image of man struggling in the snow, battling against nature, valiantly pulling a sledge, as the transport that is associated with British polar exploration. William Barr has calculated that dog sledges as opposed to man-hauled sledges undertook some 28 percent of the overall distance travelled by sledge during the British Franklin search expeditions.126

The notion of the moral superiority of man-hauling and the struggle that we see in May’s lithographs, but not to the same extent in his drawings, was adopted by Robert Falcon Scott and re-enacted in Antarctica in the early twentieth century.127 As Lisa Bloom argues, Scott was concerned with ‘constructing an image of a noble struggle’, and dogs ‘would compromise this heroic image’.128 These lithographs and other prints like them were a key way of reinforcing the polar regions as a ‘theatre of the tragic-heroic defeat of hubristic aspiration, a figuration which is central to the remediation of the polar regions in both the Ancyent Marinere and Frankenstein’.129 In many of May’s lithographs, the viewer is presented with a degree of difficulty and physical pain indicating a Burkean sublime that is absent in the preliminary drawings. The smiling expressions of the drawings negate the sublime; solitude and silence for example, were virtually impossible on those expeditions, where a large homosocial society nestled amidst the vast skies, the smiles reminding the viewer that the men knew each other well through shared experience. The largest expeditions consisted of hundreds of men, and some smaller expeditions wintered near Indigenous communities with whom they socialised. The drawings were not fully compatible with the ‘romantic glamour … that attaches to the idea of taking risks and pains in one’s travelling’.130 In essence, the suffering apparent in May’s lithographs on Arctic Travelling can be seen as performative suffering within a sublime landscape. The visual absence of the dogs, or any reference to them in the written account of the plates, signals a desire on the part of whoever was influencing the publication of the lithographs to display a more perilous and difficult travelling experience, one of the ‘markers of authenticity, and flowing from that authenticity an authority and cultural capital’.131 The lithographs present the Arctic, foreshadowing Scott’s heroic suffering in Antarctica, as the ‘theatre of heroic defeat’.132

Conclusion

With their comments on the ‘appearance of inaccuracy’ in Cresswell’s lithographs, the reviewer in the Athenaeum had, perhaps unwittingly, hinted at the difficulty that lithographers faced when transforming an amateur artist’s sketches of the Arctic into an appealing and convincing product. It is likely that this required extensive input from the lithographic artists’ imagination and memories, including, perhaps, a familiarity with the numerous Arctic exhibitions in London that had been opened to the public since 1850.

The display of expensive lithographs in printsellers’ windows and inside their premises allowed a far greater number and variety of people to view them, indicating that the influence of the Arctic lithographs was greater than has previously been assumed. The high cost did not preclude their impact on the people who could not afford to have them on their drawing-room tables. The format of these productions, ‘fac similied’ from officers’ drawings suggested a commitment to both ‘truth’ and ‘accuracy’ and the association of lithography with ‘direct duplication’133 reinforced that impression. Viewers must have been aware of the tendency of exhibitions such as panoramas and dissolving views to exaggerate or be based on an imaginary Arctic, but the lithographs were trusted, for the most part, as being wholly factual. However, the unease surrounding the truth-value of pictures, which extended to such lithographs even though they were generally thought of as being reliable, suggests a distrust of visual material as a factual source by mid-century.

While Browne’s folio Ten Coloured Views (1850) betrays a strong scientific interest through composition, subject matter, and titles, it also conveys a romanticism that connects with nature. However, despite the topographically impressive cliffs of the region, the lithographer still felt the necessity to heighten any sublime effects, particularly to enhance the darker aspects of the search. Later lithographs of Inglefield, Cresswell, and May increasingly imply that a battle is being waged against the capricious Arctic nature in an effort to find Franklin. They show an interest in displaying British masculinity, ships in peril, and the labour of sledge travel suggesting the moral sublime.

Ultimately, these prints must be viewed as artefacts that combine officers’ sketches, lithographic artists’ imaginations, and the interests of the Admiralty and of the publishers. Arresting images like Cresswell’s famous Critical Position of H.M.S. Investigator, which are prevalent in secondary texts today, were not the products of individuals alone.