All independent democratic states have a degree of cultural diversity, but for comparative purposes we can say that, at any given time, states may be divided analytically into three different categories:

-

1. States that have strong cultural diversity, some of which is territorially based and politically articulated by significant groups that, in the name of nationalism and self-determination, advance claims of independence.

-

2. States that are quite culturally diverse, but whose diversity is nowhere organized by territorially based politically significant groups mobilizing nationalist claims for independence.

-

3. States that may appear to be relatively culturally homogeneous.

In this article, I will call countries, part of whose territory falls into the first category, ‘robustly politically multinational’. Canada (owing to Quebec), Spain (especially owing to the Basque country and Catalonia) and Belgium (owing to Flanders) are ‘robustly politically multinational’. India, owing to the Kashmir Valley alone, merits classification in this category. Furthermore, at various times the Mizo Movement in north-east India, the Khalistan movement in the Punjab, and the Dravidian movement in southern India, as well as other movements, have also given a multinational dimension to Indian politics.

Switzerland and the United States are both sociologically diverse and multicultural. However, since neither country has significant territorially based groups mobilizing claims for independence, both countries clearly fall into the second but not the first category. Finally, countries such as Japan, Portugal and the Scandinavian countries fall into the third category.

What political implications do these three very different situations have? A major implication is that, if at the time of the inauguration of competitive elections, a polity has only one significant group that sees itself as a nation, and there exists a relatively common sense of history and religion and a shared language throughout the territory, nation-state building and democracy-building can be mutually reinforcing logics.

However, if a polity (like Spain at the death of Franco, India at independence or Belgium after the 1970s) has some dimensions that are politically robustly multinational, as well as deeply multicultural, nation-state building and democracy-building will be conflicting logics. This is so because one of the nations will be privileged, and the others, in Charles Taylor's sense, will be less recognized.Footnote 2 They may even be marginalized.

For a number of years, my long-time co-author, Juan J. Linz, and I, and a new co-author, Yogendra Yadav, from the Centre of Developing Societies in Delhi, have been thinking about what, if any, set of norms, social practices, party coalitions and political institutions might be compatible with social peace and political democracy within a politically robust multinational polity. We are not against nation-states. If they exist, fine. We are also not against peaceful negotiated secessions, but my focus in this article is what, if anything, can be done, if the goal is peace and democracy in one state, and the overall polity is close to a situation that I have described as ‘robustly political multinational’.

This question has been under-theorized and under-examined. What follows is an attempt to address this difficult, but not unsolvable, problem. To begin this inquiry, let me illustrate how the ‘nation-state’ ideal type is sharply different from an alternative ideal type that Stepan, Linz and Yadav call the ‘state-nation’ ideal type (see Table 1).

Table 1 Democracy and Cultural Nation(s): Two Contrasting Ideal Types of Democratic States – ‘Nation-State’ and ‘State-Nation’

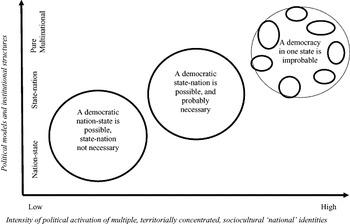

If we are concerned with varying degrees of ethno-mobilization in a polity, in what political context is a democratic ‘nation-state’, or a democratic ‘state-nation’ most probable, and most improbable? Are there some circumstances in which neither ideal type is probable? Theory, and empirical experience, indicate that ‘context matters’ for what general type of state institutional arrangements are appropriate, or even possible, given different intensities of ethno-cultural mobilization. In terms of ethno-mobilization and its relationship to state structures, there can be three sharply different contexts.

The first is a nation-state context. If only one significant, territorially concentrated, politically activated sociocultural identity exists, democratic nation-state crafting is possible. State structures can be unitary (e.g. France and Japan in the nineteenth century) or symmetrically federal (e.g. Australia in the early twentieth century and the German Federal Republic after the Second World War).

The second context is a state-nation context. If significant multiple but complementary identities exist, democratic state-nation crafting is possible, but nation-state crafting will probably be quite conflictual. The least conflictual state structure would be asymmetrical federalism, in which some cultural prerogatives are constitutionally embedded for subunits with salient and mobilized territorial identities (e.g. Belgium, Spain, Canada and India).

Third is what I call a pure multinational context. If almost no emotionally moving polity-wide common symbols exist, if almost all of the functions of the central state have been transferred or acquired by national subunits, if most citizens in subunits of the state primarily identify with ‘national’ aspirations in these units and see these units as nation-states in potentia, the political identities will tend to be singular and conflictual and there will be little loyalty to central state authorities. In this ethnocultural context, crafting a democratic, federal, ‘pure multinational’ polity in one territory is extremely improbable, due to interacting, probably violent, conflicts between secessionist attempts and possible recentralization efforts (e.g. Yugoslavia in the late 1980s). These three, quite different, contexts are depicted visually in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Democratically Probable and Improbable Relationships between Activated, Territorially Concentrated, Sociocultural Identities and Political-Institutional Strategies

In Figure 1, the circle in the upper right-hand side space that I call ‘pure multinationalism’ has deliberately been given a non-continuous and faint border to indicate that the polity is more porous and has a substantially lesser degree of ‘stateness’ than either a nation-state or a state-nation. I have also put numerous small circles and ovals within this space to indicate that these are really a cluster of aspirant nation-states within this weak state. The situation depicted in the upper right-hand corner is inherently unstable as a single democratic state. The two most likely re-equilibrations are: (1) that the aspirant nation-states become independent states and the previous single state fragments; or (2) that there is an attempt at authoritarian recentralization by a major ethnopolitical military component of the threatened state.

In the late 1980s, the two ethno-federal states of the former USSR and Yugoslavia could analytically be said to have occupied space analogous to the upper right corner of Figure 1. At the last count, 25 near ‘nation-states’ have emerged, often with substantial bloodshed and repression, out of these two ethno-federal states. Given this, is it right to assert, as many have done, that all ethno-federalarrangements are ‘state-subverting’?Footnote 3 Or, is such a deduction a dangerous half-truth, yet one more example of the ‘tyranny of the last instance’? As I hope to demonstrate in the rest of this article, the ideal type of ‘state-nation’ must be radically differentiated from the ideal type depicted in the upper right-hand box in Figure 1 that I call ‘pure multinationalism’.

The question I want to explore now is whether the somewhat ethno-federal arrangements in the state-nation ideal type are necessarily state-subverting mechanisms? Or, can there be identifications, norms, practices and institutions that can facilitate the construction of a democratic polity close to a state-nation ideal type?

THE ‘NESTED GRAMMAR’ OF STATE-NATIONS

On theoretical and empirical grounds I would like to make the case that there are arrangements that cohere in an unusual, almost counter-intuitive, nested policy grammar that may facilitate the emergence and persistence of a state-nation.Footnote 4 There are seven phrases that are an intrinsic part of this grammar:

-

1. An Asymmetrically Federal, but not a Unitary, or Symmetrically Federal State;

-

2. Individual Rights and Collective Recognition;

-

3. Parliamentary, instead of Presidential or Semi-Presidential, Systems;

-

4. Polity-Wide and‘Centric-Regional’ Parties and Careers;

-

5. Politically Integrated but not Culturally Assimilated Populations;

-

6. Cultural Nationalists versus Secessionist Nationalists;

-

7. Earned Pattern of Complementary, even though Multiple, Identities.

Why Probably an Asymmetrical Federal State?

A federal, rather than a unitary state, is part of the grammar because federal state structures allow a large territorially concentrated cultural group, with some serious nationalist aspirations, and possibly a language with its own script, to exercise self-government in that territory. Why asymmetrical? In a symmetrical federal system all units must have identical rights and obligations. It is politically possible, however, that some territorially concentrated and culturally diverse groups have in their history acquired prerogatives that they would want to retain or reacquire, and it is also possible that some tribal groups that control a large territory (such as the Mizos in India) would only agree to join the federation if some of their land-use laws, found nowhere else in the polity, were respected. Bargains and compromises on these issues, which might be necessary for peace and voluntary membership in the political community, are negotiable in an asymmetrical federal system, but are normally unacceptable in a symmetrical federal system.

Why Individual Rights and Collective Recognition?

The polity would not be democratic unless throughout the polity individual rights were constitutionally inviolable and state protected. This necessary function of the centre cannot be devolved. But in Charles Taylor's sense, some territorially concentrated cultural groups, even nations, may need some collective recognition for rights (beyond the classic liberal rights that Michael Walzer calls ‘Liberalism 1’). Such collective recognition of rights (which Walzer calls ‘Liberalism 2’) might be necessary to enable members of some groups to thrive culturally and to exercise fully their classic Liberalism 1 individual rights.Footnote 5 Walzer argues that Liberalism 2 ‘allows for a state committed to the survival and flourishing of … a (limited) set of nations, cultures and religions – so long as the basic rights of citizens who have different commitments or no such commitments are protected’.Footnote 6 There may well be concrete moments in the crafting of a democracy where individuals cannot develop and exercise their full rights until they are active members of a group that struggles and wins some collective goods common to most members of the group. These collective, group-specific, rights might be most easily nested in asymmetrical federalism. For example, if a large territorially concentrated cultural group speaks a different language with its own script, some official recognition of the privileged right of that language to be used in self-government, and in schools, radio and television, might be necessary to enable the individual rights of the members of this unit to be realized. Furthermore, for a state-nation, individuals in their ethno-federal units may not be able to participate fully in the overall federal polity, if in addition to their right of self-government in their own language, some polity-wide link language is not maintained.

The identification and loyalty of the practitioners of territorially concentrated minority religions with the centre may very well be reduced if the majority religion is the established religion throughout the territory. In such cases, it may encourage identity with the state-nation if all religions are recognized and possibly even financially supported. The financial support of religions, majority and minority, is of course a violation of classic US or French separation of religion and State doctrines, but it is not a violation of any person's individual human rights.Footnote 7

Why a Parliamentary instead of a Presidential or Semi-Presidential System as Part of the ‘Grammar’ of a State-Nation?

The elected executive in a presidential or a semi-presidential system is an ‘indivisible good’– it is necessarily occupied by one person, from one nationality, for a fixed term. However, a parliamentary system creates the possibility of a ‘sharable good’. That is, there is a possibility of other parties, composed of other nationalities, helping to constitute the ruling coalition. For example, if no single party has a majority, parliamentarianism is coalition-requiring. Furthermore, because the government can collapse unless it constantly bargains to retain the support of its coalition partners, parliamentarianism often has coalition-sustaining qualities. These ‘sharable’ and ‘coalitionable’ aspects of a parliamentary executive might be useful in a politically robust multinational society.

Why Polity-Wide and ‘Centric-Regional’ Parties and Careers?

If all the parties in the polity get the overwhelming majority of their votes from their own ethno-territorial unit, trust in, and identity with, the centre will probably be low. Many analysts would call such parties ‘regional-secessionist’. Political life in a polity dominated by such regional-secessionist parties would approximate the upper right-hand ‘pure multinational’ space depicted in Figure 1.

However, if the polity contains some major polity-wide parties that regularly need allies from regional parties to help them form a government at the centre, and if the polity-wide parties often help their regional party allies to form a majority in their own ethno-federal unit, then the logic of incentives at work here makes these so-called regional secessionist parties actually ‘centric-regional’ parties, because they regularly co-rule at the centre. This coalitional pattern is best facilitated if both the polity-wide and the regional parties are ‘nested’ in a parliamentary system that itself is nested in an asymmetrical federal system.

Why ‘polity-wide careers’? If some polity-wide language (such as French or English) is created or maintained, many university-educated members of a regional nationality group who do not speak the majority language in the country (say Hindi in India or Sinhalese in Sri Lanka) can still successfully pursue polity-wide careers in law, communications, civil service and business. If they can pursue such polity-wide careers, citizens may have strong incentives not to ‘exit’ from career-enhancing, polity-wide ‘networks’.

Why and How not Culturally Assimilated but nonetheless Politically Integrated?

In a state-nation, many cultural, and especially ethno-national, groups will be educated and self-governing in their own language. They will thus probably never be fully culturally assimilated to the dominant culture in the polity. This is a reality of ‘state-nations’.

However, if an ethno-federal group sees the polity-wide state as having helped to put a ‘roof of rights’ over its head, and if its ‘centric-regional’ party is ‘coalitionable’ with polity-wide parties, and regularly helps form government at the centre, and many individuals from the ethno-federal group also participate in, and feel they benefit from, polity-wide careers, they can be politically integrated into the polity-wide state-nation.

Why and How Cultural Nationalists Could Act Against Secessionist Nationalists?

Ernest Gellner forcefully articulated the position of many nation-state theorists when he famously asserted that: ‘Nationalism is primarily a political principle, which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent … Nationalist sentiment is the feeling of anger aroused by the violation of the principle … A nationalist movement is one actuated by a sentiment of this kind.’Footnote 8 Thus I am constantly admonished not to advocate state-nation ethno-federal policies because all cultural nationalism inevitably becomes ‘secessionist nationalism’ with eventual demands for independence.

However, we can have a situation in which a ‘cultural nationalist’ movement, nested in an asymmetrical federal, and a parliamentary system, wins democratic political control of a component unit of the federation; and governs and educates the citizens of its territory in the language, culture and history of their nation, and is also coalitionable at the centre.Footnote 9 If such a cultural nationalist movement in control of an ethno-federal unit is challenged by secessionist nationalists who use, or threaten to use, violence in order to secede and become independent, the ruling ‘cultural nationalists’ would risk losing the treasured resources they have acquired, and it is quite possible that they would use the political and security resources now under their control against the secessionist nationalists.

Why ‘Earned’ Complementary as Well as Just Multiple Identities?

In the non-zero sum polity-wide system produced by the six nested policies and norms I have just discussed, it is very possible that many citizens of the multinational society could be strongly identified with, and loyal to, both their culturally powerful ethno-federal unit and to the polity-wide centre. They would have such complementary identities because the centre has recognized and defended many of their cultural demands and, in addition, helped structure and protect their full participation in the overall politics of the polity. Such citizens may also have strong trust in the centre because they see the centre, and the institutions historically associated with it, as helping to deliver some valued collective goods, such as independence from a colonial power, security from threatening neighbours, and possibly even ensuring a large growing and common market. If this is so, the overall polity has earned their complementary and multiple identities.

AGGREGATE TESTS OF TRUST AND IDENTITY: NATION-STATES VERSUS STATE-NATIONS

The question that is now, correctly, in the reader's mind, is whether such a ‘state-nation’ can work. For, of course, a major claim of nation-state theorists and advocates is that only a nation-state can generate the necessary degree of trust in the major institutions of the state that a modern democracy needs.

Let me do a simple empirical test of this claim by examining comparative trust in the entire universe of federal systems that have been democratic for at least 25 continuous years. In my judgement, there are 11 such countries; in alphabetical order they are: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Germany, India, Spain, Switzerland and the United States. Fortunately, the World Values Study administered surveys in all 11 of the countries.Footnote 10 We thus have data for the degree of trust in five key political institutions for all 11 countries. These key institutions are: the central government, the legislature, the legal system, the civil service, political parties and police.

To go further with our test, let us now divide our 11 countries into those countries closest to the nation-state ideal type in that they (1) are symmetrically federal; (2) have no constitutionally embedded ethno-federal dimensions; and (3) are not de jure officially multilingual. These countries are: Austria, Germany, Australia, the USA, Brazil and Argentina. Those countries in our country set that are closest to the ‘state-nation’ ideal type in that they (1) are asymmetrically federal; (2) have constitutionally embedded ethno-federal features; and (3) are constitutionally multilingual are: India, Belgium, Canada and Spain. I will add Switzerland to this set because, even though it is symmetrically federal, it is much closer to a state-nation type than to a nation-state type, if one studies Table 1.

When we examine the average country trust scores for the five key political institutions for each of these polities, we get the following very surprising results (see Table 2).

Table 2 Ranking of Citizens' Trust in Six Major State Institutions within the World's 11 Long-Standing Federal Democracies is Better among State-Nations than Nation-States

Sources: The data for all countries but Austria, Belgium and Canada are from Ronald Inglehart et al., World Values Survey: 1995–97, Michigan, Inter University Consortium for Political and Social Research, University of Michigan, 1997. The data for Germany is from the Lander of the former West Germany. Canada, Belgium and Austria were not included in the 1995–97 survey. The data for these countries is from World Values Survey: 1990–93. For both the 1990–93 and 1995–97 surveys the question numbers were, from top to bottom, 142, 144, 137, 141, 143 and 145. Question 143 was not asked in Canada. Questions 142 and 143 were not asked in Belgium or Austria. See Alfred Stepan, Juan J. Linz and Yogendra Yadav, Democracy in Multinational Societies: India and other Polities, Baltimore and London, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008, chapter 2.

The ‘closer to the nation-state, the greater the trust’ claim is obviously not supported by these data. Neither is the claim that ‘any use of ethno-federal devices is subversive of the state’, because all of the countries close to the state-nation pole have some ethno-federal features as well as strong polity-wide trust. Advocates of the inherent superiority of nation-states also base their arguments on theirassumption that only a nation-state can generate the necessary degree of strong identity and pride in membership in the state that is best for a democracy. However, when I examined the average World Values scores for ‘strong pride’ in being a member of one's country, I found that the results are statistically indistinguishable between nation-states and state-nations, with the latter actually having marginally more pride. In the survey, 83 per cent of the respondents in the nation-state set expressed ‘strong pride’ in being a member of their country, but in the multilingual, multicultural polities closest to the state-nation ideal type, 84 per cent expressed ‘strong pride’.

INDIA AS A STATE-NATION?

India would seem to be one of the most difficult cases for our argument that multiple and complementary identities, and democratic state-nation loyalties, are possible even in a polity with significant ‘politically robust multinational’ dimensions, as well as intense linguistic and religious differences. At independence, at most 40 per cent of India's population could communicate with each other in Hindi. Furthermore, there were at least nine other languages used by 13 million to 32 million inhabitants of India, almost all with their own scripts.Footnote 11 Indian society also had large communities of almost every world religion – Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs and Christians. Even after partition in 1947, India had a major Islamic population. In 2008, India's Islamic population constitutes a ‘minority’ of at least 140 million, which makes it the world's third- or fourth-largest Islamic population in any country, exceeded only by Indonesia, Pakistan, and possibly by Bangladesh.

The question of India's comparative poverty is relevant to the potential ‘scope value’ of our state-nation concept. How wealthy does a country have to be, before it can utilize state-nation policies? The scope value concerning wealth would seem to be quite great because India's per capita income in purchasing power parity is almost eight times less than any of the three other ‘politically robust multinational’ democracies. Of the four multinational federal democracies in the world – Spain, Canada, Belgium and India – India is the only country that does not have an advanced industrial economy. The 2005 per capita income in current international dollars of the four multinational federal systems in descending order was; Canada $33,375, Belgium $32,119, Spain $27,169 and India $3,452.Footnote 12 But before analysing India's overall situation I want to stress that India has many problems, and its policies towards women, Muslims and ‘very poor’ should be, and could be, greatly improved (see Table 3).

Table 3 Comparative Indicators of India's Human and Income Poverty

Sources: UNDP, Human Development Report 2002: Deepening Democracy in a Fragmented World, New York and Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 149–52, 157–9, 172, 190–3, 224. Arend Lijphart, Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries, New Haven, CT, and London, Yale University Press, 1999, see table 4.1 for Lijphart's universe of the 36 countries in the world that were all continuous democracies in his judgement from at least 1977 to 1996. Government of India, Prime Minister's High Level Committee, ‘Social, Economic and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India’ (Sachar Report), A Report by the Prime Minister's High Level Committee, Cabinet Secretariat, Government of India, November 2006.

Given this great poverty, areas of policy failure, and unrivalled cultural diversity, what do the people who live in the territory of India think of the state that rules their territory? Do they identify with India or not? Do they trust Indian institutions or not? Do the citizens share important politically relevant attitudes in common? In short, is India close to, or far from, having political attitudes supportive of a state-nation?

Let us attempt to examine these questions. If a country is actually close to being a state-nation, what should we be able to document in terms of public opinion? On theoretical grounds, it would seem reasonable to insist that if people live in a territory, and have attitudes supportive of what I call a ‘state-nation’, three key sets of attitudes should be empirically present and verifiable:

-

1. positive identification with the overall state-wide polity as well as with their own ethnic-linguistic culture;

-

2. strong trust in the major polity-wide institutions of the state;

-

3. as strong support of democracy as the polities in nation-states with roughly comparable years as democracies and roughly similar levels of socio-economic development.

Fortunately, we can explore these questions for India in comparative perspective, because, as I have indicated, India and all the long-standing federal democracies have been included in most of the rounds of the World Values Study (WVS). For India, we have exceptionally rich data, because, in addition to the WVS data, Yogendra Yadav, Juan J. Linz and I constructed many questions of direct relevance for exploring our state-nation hypothesis for the State of Democracy in South Asia (SDSA) of 2005 and Yogendra Yadav was the director of India's National Election Study (NES) of 1999 and 2004, the latter with a census-based sample of 27,145, both studies conducted at the Centre for the Study of Developing Studies in Delhi. Yadav has also done numerous single-state surveys in states that at one time have had conflicts with the centre, such as Mizoram and Punjab, or that currently has a conflict with the centre, such as Kashmir.Footnote 13

With this rich survey data, let us see whether India scores positively on the three key sets of attitudes that I argue should be present and verifiable if India is actually close to the state-nation ideal type.

How much pride do Indians have in their state compared to the 10 other long-standing federal democracies? At the aggregate level, only respondents from the United States and Australia, express more pride in being members of their state than those from India (see Figure 2).Footnote 14

Figure 2 How Proud are You to be an Indian/Brazilian/ … ? Responses in the 11 Longstanding Federal Democracies (percentage who answer ‘very proud’)

Source: The data for all countries is from response to the question ‘How proud are you to be (nationality)?’ Ronald Inglehart et al. (eds), Human Beliefs and Values: A Cross-Cultural Sourcebook Based on the 1999–2002 Values Survey, Mexico, DF, Siglo XXI Editores, 2004.

My confidence level concerning respondents' pride in being Indian is strengthened by the fact that pride questions were given twice by WVS and once by SDSA 2005, and the results in all three surveys are quite similar (see Table 4).

Table 4 Pride in India, 1990–2005 (per cent)

Source: WVS = different waves of the World Values Survey; SDSA = State of Democracy in South Asia survey conducted by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in 2005.

In order to explore our state-nation hypothesis, however, it is crucial that we examine the attitudes of India's largest religious minority – Muslims – to see how similar or dissimilar they are from the attitudes of India's religious majority, Hindus. We also should explore the attitudes of the ‘scheduled castes’, the group that were formerly called ‘untouchables’, because they were historically many of the poorest and most socially marginalized of India's citizens. If we combine ‘very proud’ and ‘proud’, Muslim and scheduled castes' responses concerning our pride variable are virtually indistinguishable from the all-India average (see Table 5).

Table 5 Pride in India for all Citizens and for Muslims and Scheduled Castes, 2005 (per cent)

Source: State of Democracy in South Asia Survey, conducted by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in Delhi in 2005.

Let us now examine the data for our second variable, which concerns state-wide trust in political institutions. Pippa Norris, in her book Critical Citizens, constructed a political institutional confidence scale for 21 democracies. In this scale, India ranked at the top of the 21 countries (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Institutions and Political Trust in India and 20 Other Democracies: 1990–93

Source: Pippa Norris, Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999, figure 11.2, p. 229.

Let us go back to the World Values Survey (WVS), which elicits respondents' trust concerning six major politically relevant institutions. Within our set of the 11 long-standing federal democracies, India scored the highest of the 11 countries in trust concerning its legal system, parliament and political parties, and the second highest concerning central government and the civil service, and the second lowest (correctly in my opinion) concerning the police. Let us look at how the three countries – India, Switzerland and Canada – who scored the best on trust were ranked (see Table 6).

Table 6 Citizens Who Affirmed a ‘Great Deal’ or ‘Quite a Lot’ of Trust in Six Major Institutions: Percentages Among the Three Top-Ranked Federal Democracies

Source: The data for India and Switzerland is from Ronald Inglehart et al., World Values Survey: 1995–97, Michigan, Inter University Consortium for Political and Social Research, University of Michigan, 1997. Canada was not included in the 1995–97 survey. The data for Canada is from World Values Survey: 1990–93. For both the 1990–93 and 1995–97 surveys the question numbers were, from top to bottom, 142, 144, 137, 141, 143 and 145. Question 143 was not asked in Canada.

The third variable that we need to examine is Indian support for democracy in comparison to some important ‘third-wave’ democracies. Respondents in India indicate substantially more support for democracy, and more opposition to authoritarian rule, than do the nation-states of Korea, Chile and Brazil. And, if we only utilize ‘valid’ responses – that is, if we eliminate ‘don't knows’ and ‘no answers’, as is often done in survey analysis – India compares favourably with Spain and Uruguay, and is overwhelmingly more supportive of democracy than Chile, Korea and Brazil (see Table 7).

Table 7 Attitudes Towards Democracy and Authoritarianism in India and Five Selected ‘Third-Wave’ Democracies: Percentage Agreeing with the Following Statements

Source: The data for India are from the National Election Study, 1999 and National Election Study, 2004, of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi. Data for Uruguay, Brazil and Chile are from the Latino Barometer 1996, directed by Marta Lagos. The Spanish data are from the Eurobarometer 37, 1992. The Korean data are from the Korea Democracy Barometer, 2004, directed by Doh Chull Shin.

INTEGRATING AND DISINTEGRATING STATES: TAMILS IN INDIA VERSUS TAMILS IN SRI LANKA

Let us now shift from surveys and attitudes, to policies and outcomes. Let me specifically contrast how India, following state-nation policies, politically integrated the Tamils in the south, and how Sri Lanka, following nation-state policies towards the Tamils in the north, has almost disintegrated the state.Footnote 15

One could make a case that, of this near ‘matched pair’, India started in the more difficult position because some important Tamil leaders, such as Periar, were associated with the Dravidian secessionist movement, which burned the Indian flag at independence and the constitution when it was released.Footnote 16 Indeed, there had been a long series of conflicts and riots between Dravidian Tamils and the Brahmin Hindu northern elite in what is now Tamil Nadu. We can thus say that there was a ‘politically robust multinational dimension’ to politics in Tamil Nadu, despite the fact that many Tamils felt great attachment to the polity-wide independence movement led by the Congress Party.

Sri Lanka started in an easier position in that for one hundred years before independence there had been no politically significant riots between Sinhalese, who were largely Sinhalese-speaking Buddhists, and the Tamils, who were largely Tamil-speaking Hindus. In fact, the first president of the Ceylon Congress Party was a Tamil. Tamils had done well in English-language civil service exams in Ceylon and though interested in greater power-sharing, it is still true to say that at independence there had been no Tamil claims for devolution or federalism, much less independence. Ceylon also had a much higher per capita income than India, and could have made modest side payments to some Sinhalese groups, especially the Buddhists, which had been marginalized during the period of British colonial rule.Footnote 17

The potential issue of Tamil separatism in India had become a non-issue 35 years after independence, and the Sri-Lankan non-issue had become a bloody civil war for secession that has been raging for a quarter of a century. Why such radically different outcomes? Much, but of course not all, of the explanation, I believe, is related to the radically differential application of the nested policy grammar I discussed earlier. Let me conclude with a comparative table highlighting the state-integrating state-nation policies followed by India, and the state-disintegrating nation-state policies followed by Sri Lanka. Table 8 suggests a strong affirmative answer to the title of my article.

Table 8 The ‘Grammar’ of Politically Handling Actual or Potential Politically Robust Multinational Societies Peacefully and Democratically: Contrasting Strategies of India and Sri Lanka towards Tamils