Right-wing populist parties and leaders have been increasingly successful over the past two decades, achieving record electoral results and governing in some of the world's major democracies. At the core of their appeals is the denunciation of elites, with the populists self-cast as the only ones able to relate to the people (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015; Mudde Reference Mudde2019). This juxtaposition of themselves with the establishment is said to be reflected in the distinct language that populist leaders use (Canovan Reference Canovan1999; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016). However, we do not know what makes it distinct.Footnote 1 In fact, while scholars have created dictionaries of likely populist words and then looked for them in texts (Bonikowski and Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016; Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011), these deductive approaches decide in advance the vocabulary that characterizes populists. As a result, they may include words that are not in fact particular to populists while excluding others that are. In this study, we therefore adopt an inductive method by first gathering corpora of speeches, and then extracting the keywords – ‘items of unusual frequency in comparison with a reference corpus’ (Scott and Tribble Reference Scott and Tribble2006: 55) – that distinguish right-wing populist and mainstream leaders from one another in different languages. We then check the contexts in which those keywords are used in order to understand better their meanings. Specifically, we compare three prominent right-wing populist leaders of the past decade – Donald Trump in the United States, Marine Le Pen in France and Matteo Salvini in Italy, with their principal mainstream opponents – and ask, What distinguishes the vocabularies of right-wing populist leaders from those of their mainstream rivals?

Our point of departure in studying populist vocabulary is that words matter, and keywords matter in particular. The latter not only can indicate the topics that distinguish one leader from another, but they also shed light on how leaders talk about those topics. Especially given populism's geographic span and chameleonic tendency to shape itself to its environment (Taggart Reference Taggart2000), it seems instructive to look at right-wing populist keywords across languages. Since words have layers of inherent meanings and associations, conscious and unconscious, built up over time in distinct cultural contexts, the same broader meaning may be conveyed using different words that have specific historical resonances in a given language and culture (e.g. ‘the citizens’ rather than ‘the people’). Likewise, the same apparent concepts, even when expressed by morphologically similar words in different languages, can convey different meanings due to their specific legacies and associations. It is one thing, for example, to talk about ‘republican values’ in Ireland, and quite another to talk about ‘les valeurs républicaines’ in France. In short, taking a bottom-up perspective and looking at its keywords across languages may help us understand right-wing populism's global and country-specific characteristics.

Our analysis shows that right-wing populist leaders' vocabularies are not distinguished by keywords that are straightforward translations of one another in English, French and Italian. However, we find that their different sets of keywords do all clearly reflect right-wing populism's specific ideological focus on the ‘good people’, ‘bad elites’ and ‘dangerous others’ (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015; Wodak Reference Wodak2021: 5). They also reflect – albeit in different ways and to different extents across our cases – several prominent features of populist style. Our work thus shows that, first, the ideational and stylistic approaches are complementary, as both shed important light on the concept; second, while the ideological approach to populism sees it as a classical concept with clear pillars and boundaries, the stylistic approach to populism is more a family resemblances concept in which not all elements are present at all times (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017); third, our findings also indicate that, at least in terms of style, some leaders may be more populist than others, which in turn points to the merits of a gradational view of populism (Laclau Reference Laclau and Panizza2005; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016: 46).

In the next section, we set out what we would expect the main traits of right-wing populist vocabulary to be, drawing from the literature on right-wing populist ideology and on populism as a style. We then discuss deductive attempts to identify distinctively populist words through the creation of dictionaries. Thereafter, we present our cases, corpora and method. In the results section, we report our main findings while, in the conclusion, we reflect on the implications of our results and suggest paths for future research.

Right-wing populist ideology and style

The field of populism studies includes, among others, those who understand it primarily as an ideology (Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Stanley Reference Stanley2008) and those who conceive of it principally as a style (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016).Footnote 2 In our research, however, we consider both approaches as important for understanding populist language. Take, for example, the following invented statements:

‘Everyone is unhappy at the moment. The political class do not deign to think about ordinary people. We've had enough of their corruption, and enough of seeing illegal immigration rising year after year.’

‘Hardworking folks are totally pissed right now. The professional politicians need to stop lining their pockets, stop ignoring the people who pay their wages, and stop this unprecedented invasion of our country by criminals.’

The first statement presents words expressing right-wing populist ideas (namely, corrupt elites are ignoring the sovereign people, who in turn are annoyed at them and under threat from immigrants). The second statement sets out the same ideas but using coarser, more dramatic and more colloquial language. This difference has implications for electoral support. As Glenn Kefford et al. (Reference Kefford, Moffitt and Werner2021) have shown, voters are motivated positively and negatively by their attitudes towards populist ideas and populist styles of communication in combination, but also by their reactions to each of these separately.Footnote 3 Since both right-wing populist ideology and style can be expressed through word choices, we therefore take from theory on both in developing our expectations about the distinguishing features of right-wing populist vocabulary.

According to the ideational approach, which has become the dominant one for studying populism,Footnote 4 right-wing populist ideology has three essential building blocks: (1) good people; (2) bad elites; and (3) dangerous ‘others’ (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015; Mudde Reference Mudde2019). The first two are ever-present in populist appeals of both left and right. As Margaret Canovan (Reference Canovan1981: 294) observes, ‘all forms of populism without exception involve some kind of exaltation of and appeal to “the People” and all are in one sense or another anti-elitist’. This dichotomy of a ‘good’ people and ‘bad’ elites underpins the widely used definition by Cas Mudde (Reference Mudde2007: 23), who conceives of populism as ‘a thin-centred ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’. Populism on the right, however, has a further antagonistic element, which is ‘the others’. For right-wing populist leaders, the people are said not only to have the elites as enemies, but also a range of dangerous ‘others’ who threaten the people's rights, traditions and prosperity (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015: 5–6). In recent decades, the main ‘others’ for right-wing populists have been immigrants (especially Muslims), but, depending on the country, the ‘others’ can include homosexuals, welfare recipients, communists, student protesters or any group within society whose ethnic identity, religious and political beliefs or behaviour may be construed as placing them not only outside ‘the people’, but in an antagonistic relationship to them. We would therefore expect the distinctive words of right-wing populist vocabularies in each language to include terms expressing the above three ideational building blocks: a good people, bad elites and dangerous others.

While it shares the ideational literature's attention to the moral juxtaposition of ‘good people and bad elites’, the stylistic approach to populism devotes particular importance to how populists communicate and perform. For the purposes of our research, we primarily follow one of the most influential authors using this approach, Ben Moffitt, who defines populism as ‘a political style that features an appeal to “the people” versus “the elite”, “bad manners”, and the performance of crisis, breakdown or threat’ (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016: 45).Footnote 5 In addition to the first part of the definition about people and elites, which we have covered when discussing right-wing populist ideology above, the latter two elements – ‘bad manners’ and ‘the performance of crisis, breakdown or threat’ – also relate to the words populists use. Although not limited to verbal communication, exhibiting ‘bad manners’ involves the breaking of established conventions of behaviour. As such, it includes coarse rhetoric, slang and showing ‘a disregard for “appropriate” modes of acting in the political realm’ (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016: 58; see also Ostiguy Reference Ostiguy2009). Of course, from the populist perspective, it is not a question of displaying bad manners, but of challenging ‘political correctness’ (Wodak Reference Wodak2021: 90–94). Likewise, ‘the performance of crisis, breakdown or threat’ encompasses the use of dramatic and emphatic language, designed to convince people that they are facing individual and collective ruin unless they support the redemptive populist (Canovan Reference Canovan1999). Finally, populists are said to be more to-the-point than their mainstream opponents, using direct language to articulate ‘political analyses and proposed solutions’ that are similarly direct (Canovan Reference Canovan1999: 5–6). Or, as Rogers Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2017: 367) puts it, ‘the populist style performatively devalues complexity through rhetorical practices of simplicity, directness, and seeming self-evidence’. Consequently, they avoid ‘speaking in the convoluted language of technocrats or relying on abstraction’ (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016: 143). Overall, therefore, we would expect the distinctive vocabularies of right-wing populists to comprise words reflecting the stylistic features above, including coarse and vulgar rhetoric, directness and dramatic speech.

Right-wing populist words

The main body of work relevant to us is by scholars who have created dictionaries in different languages of likely populist words and searched for them in texts such as manifestos, speeches and tweets (Maurer and Diehl Reference Maurer and Diehl2020; Oliver and Rahn Reference Oliver and Rahn2016; Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011).Footnote 6 While it can be useful for identifying passages containing populist ideas, we argue that the dictionary-based deductive approach is less helpful than inductive ones for identifying distinctive right-wing populist vocabulary. This is due to the risk of dictionaries, on the one hand, including some terms that are not characteristic of populists and, on the other, omitting key terms that are characteristic of them. We therefore contend that inductive approaches to analysing populist language should complement deductive ones, such as dictionaries.

Teun Pauwels (Reference Pauwels2011) was the first to construct such a dictionary, which he used to analyse manifestos and grassroots members' magazines of Belgian parties. Shortly afterwards, Matthijs Rooduijn and Teun Pauwels (Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011) assembled the first multilingual dictionary of populist terms and analysed election manifestos of parties from Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK. To create their common dictionary for the four languages, they chose a series of words used by populists ‘to position the bad elites against the good people’ (Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011: 1276). In line with Pauwels's earlier work, they focused on words that denoted anti-elite stances since ‘a measurement of people-centrism by means of individual words only is nearly impossible’, as ‘not every mention of the words “our” and “we” is a reference to the people’ (Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011: 1275). Their dictionary included 14 terms they considered reflective of anti-elite stances. For each language, the authors added a small number of words ‘which are too context-specific to be translated from one language to another’ (Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011: 1276).

Researchers have since used similar dictionary-based approaches to assess populism in English and other languages. Bart Bonikowski and Noam Gidron (Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016) analysed speeches by US presidential candidates between 1952 and 1996 using a dictionary of 34 words and phrases they considered to be populist markers. Like the dictionary of Rooduijn and Pauwels (Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011), most of these relate to anti-elite stances, but there are also entries to indicate the people (Bonikowski and Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016: 1619). Notably, there are only two similar items in Rooduijn and Pauwels's dictionary and that by Bonikowski and Gidron: the former contains elit* and politic* while the latter has the bigrams ‘Washington elite’ and ‘professional politician’. In the same year, Eric Oliver and Wendy Rahn (Reference Oliver and Rahn2016: 192–193) investigated how US presidential candidates used populism in their announcement speeches. To do so, they devised dictionaries of negative terms referring to political and economic elites. While they do not provide the full dictionaries, they list 21 words and phrases. Of these, only ‘elite’ is found in Rooduijn and Pauwels (Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011), and only ‘elite’, ‘special interest(s)’, ‘millionaires’ and ‘Wall Street’ in Bonikowski and Gidron (Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016).

We find similar heterogeneity among dictionaries of populism in French and Italian. Daniel Stockemer and Mauro Barisione (Reference Stockemer and Barisione2017) searched press releases by the French right-wing populist party Front National (National Front) from 2013 to 2015 for eight verbal indicators of populism, while Peter Maurer and Trevor Diehl (Reference Maurer and Diehl2020) assembled a French dictionary with 325 words and phrases. Of these, only four are common to the Stockemer and Barisione list (‘elites’, ‘people’, ‘French’ and the centre-right party ‘UMPS’). As regards Italian, Silvia Decadri and Constantine Boussalis (Reference Decadri and Boussalis2020) created a dictionary with 18 anti-elite and seven people-centric items to analyse populist language in parliamentary speeches and parties' press releases. With a few exceptions, their anti-elite entries are the same as those in the Italian dictionary of Rooduijn and Pauwels (Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011). Their people-centric items, however, are all original, given that Rooduijn and Pauwels had only investigated populism as expressed by anti-elite language (Decadri and Boussalis Reference Decadri and Boussalis2020: 489–490).

The diversity of what scholars consider distinctive ‘populist’ vocabulary speaks to Paris Aslanidis's observation that, notwithstanding the many merits of automated text analysis, ‘human interpretative bias is still at work, concealed within the preparatory stage of choosing words to populate dictionaries’ (Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2018: 1245). Moreover, and especially pertinent to our aim of understanding the distinctive vocabularies of leaders in different countries, there are pitfalls in using a single dictionary across languages. Rooduijn and Pauwels (Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011: 1276) contend that ‘populists in every country and every time period do essentially the same thing: they position the good people against the bad elites. Because they make this same argument, we assume that they also use similar words’ (emphasis added). But this assumption is highly questionable, given the importance of cultural contexts for word choices. In contrast to the creators of dictionary-based studies, we therefore have no expectations about the specific keywords we will find. Like those authors, however, we do anticipate that the vocabulary of right-wing populist leaders will reflect the cornerstones of their ideology. Moreover, we also expect that their distinctive vocabulary will reflect stylistic elements of populism such as directness, dramatic language and vulgarity.

Cases and corpus compilation

The three right-wing populist cases we examine are Donald Trump (United States), Marine Le Pen (France) and Matteo Salvini (Italy). All have been recent party leaders, presidents and/or presidential nominees.Footnote 7 They have also all been treated in the literature as populists of the right (e.g. Mudde Reference Mudde2019; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019). In the US and France, we compare Trump and Le Pen with their main opponents, Clinton and Macron, during those countries' respective 2016 and 2017 presidential election campaigns. In Italy, we compare Salvini with the most prominent centre-left leader in the 2013–2017 period, Matteo Renzi.Footnote 8

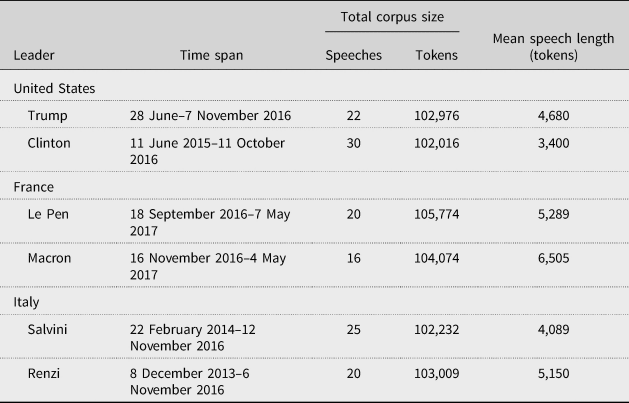

Table 1 sets out the main characteristics of our corpus in terms of speakers, the time period from which we took speeches for each politician, the total sub-corpus size and the mean length of speeches (the locations and dates are available in Appendix A in the Supplementary Material).Footnote 9 The number of word-tokens in Table 1 refers to the total number of running words, as opposed to word-types, a term used in linguistics to refer to the list of all the different forms included in a corpus. For example, in any text we will find many repetitions (i.e. tokens) of single types such as ‘the’, ‘a’, ‘of’ and so forth.

Table 1. Corpus Composition

Note: The full corpus is available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/N5PYXZ.

Our dataset, totalling 620,081 tokens, ensures good comparability for several reasons. First, our sub-corpora are comparable in terms of size as approximately 100,000 tokens were transcribed for each leader. Second, our speakers within each country case are comparable. In France and the US, we compare non-incumbent presidential candidates, while, in Italy, we compare party leaders. Third, our time spans are comparable. As Table 1 details, the speeches in each country occur in the same general period (i.e. we are comparing leaders who are selecting their speech topics from the same historical background). Fourth, our text types within each country case are comparable. In the US and France, they are monologues delivered during election campaigns. In Italy, they are also monologues and are delivered to what we can usually consider friendly audiences at events such as party conferences, rallies, campaign meetings and so forth. We have deliberately not selected debates, interviews or press conferences because the dialogical nature of these means the speakers can be considered more like ‘dancing pairs’; for example, speakers may be led by their interviewer/opponent to speak about specific topics in certain terms. Similarly, we avoided using parliamentary speeches since speakers are constrained by etiquette (Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk and Bayley2004; for an overview of parliamentary speech genres, see Ilie Reference Ilie, Tracy, Ilie and Sandel2015).

Finally, it is worth acknowledging that speeches are mostly written in advance by a team of ghost writers (with varying degrees of input from the leader). However, unlike election manifestos, for example, with speeches there is only one individual who utters the text in public and takes on the responsibility for what is said. In other words, the public does not have access to ‘Trump's original and true speech’: they are only familiar with his public linguistic image, which they get from his publicly uttered words. So, if we want to understand the language leaders use in public compared to other politicians, it is not relevant whether the words are all really their own (see also Wang and Liu Reference Wang and Liu2018: 306–307).

Method: Keyness analysis and concordances

We adopt the inductive approach of using corpus linguistics software to identify the distinctive keywords of right-wing populist and mainstream leaders across different countries and languages. This method is based on the frequency difference between words in two corpora – in our case, a corpus of a right-wing populist leader's speeches and a corpus of their principal mainstream opponent's speeches – and a statistical evaluation of the significance of these differences. The analysis allows us to obtain lists of keywords expressing topics or stylistic choices distinguishing each speaker from the other within pairs of right-wing populist and mainstream leaders. We then manually check the concordances of these keywords (i.e. the phrases and contexts in which they appear) to ascertain their semantic and stylistic environments.Footnote 10

The workflow of our analysis, detailed in the paragraphs below, was as follows: (1) the transcriptions of speeches were uploaded as corpora into AntConc (Anthony Reference Anthony2019) to extract keywords by comparing leaders from the same country; (2) AntConc was also used to extract clusters (i.e. recurrent word strings) and concordances (i.e. contexts) for all keywords found after the procedure in point 1 to analyse their meaning within the corpora; (3) the transcriptions of speeches were uploaded into TagAnt (Anthony Reference Anthony2019) to classify all words as parts of speech and remove stop words in order to conduct the robustness check reported in Appendix B1 in the Supplementary Material. To do so, only words classified as nouns, proper names, foreign words, adjectives, adverbs or verbs were maintained.

For the first step, automated and quantitative in nature, we utilize the ‘keyness’ strength measure provided by AntConc.Footnote 11 The software is freely available, thus facilitating the replicability of results, and includes a ‘keyword list’ tool to display words which are significantly frequent in a corpus in comparison with the words in a reference corpus.Footnote 12 According to Gabrielatos (Reference Gabrielatos, Taylor and Marchi2018: 228), ‘keyness analysis is essentially a comparison of frequencies. As it is currently practised, it usually aims to identify large differences between the frequency of word-forms in two corpora (usually referred to as the study and reference corpus).’ In our case, for each country, we therefore compare the populist leader's corpus of speeches with that of their mainstream opponent and extract the populist leader's keyword list. We then swap the corpora around and perform the same procedure using the populist leader's corpus as the reference to obtain the mainstream leader's keywords. We base our analysis on word-types and not lemmas,Footnote 13 since lemmatization can lead to information loss in terms of verb tenses and persons, especially in romance languages.Footnote 14 We also do not discard stop words (or ‘grammar words’, i.e. words so commonly used that they convey very little useful information, such as pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, determiners and so on) from our keyword lists. Although these are less useful than content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives etc.) for identifying topics – that is what leaders talk about – they can contribute greatly to understanding how leaders express themselves, for example if they include or exclude certain social groups (we vs they), talk about necessity (must, need, ought) rather than possibilities (can, could, should) or talk a lot about themselves (I, me, mine) and so forth. As such, if we want to know how distinctive vocabularies reflect populist style, it makes sense to include all words in our analysis. Nonetheless, as mentioned, we also run the analysis excluding stop words and find no substantial changes (see Appendix B1).

It is worth acknowledging at this point that, while keyness is the most used metric in corpus linguistics to extract keywords and is often provided by corpus analysis tools, its use of log-likelihood (or the associated p-value) has been criticized since it is influenced by corpus size and word frequency (Gabrielatos Reference Gabrielatos, Taylor and Marchi2018). As an additional check, we therefore employed another keyword extraction method: chi-square distance (see Appendix B2). No significant differences emerged from the use of this alternative method.Footnote 15

Having established the keywords for each leader, we use the ‘clusters’ tool provided by AntConc to automatically obtain a preliminary overview of the contexts in which those keywords emerge (see Appendix C in the Supplementary Material).Footnote 16 We then use the ‘concordance’ tool to move on to the second, more qualitative, step of our analysis, which is to manually check the contexts (‘concordances’) of the keywords – that is, text chunks comprising 75 characters before and after each occurrence of the selected keyword in the relevant corpus. Since natural language is characterized by synonymy and metaphorical usage (e.g., a keyword ‘fly’ could be a verb or an insect), checking contexts – that is, reading and interpreting the surrounding words and sentences – allows us to establish whether words are to be interpreted literally or metaphorically (e.g., ‘migration’ has a different meaning in a discussion of politics than it does in one about information technology). Likewise, how words are employed in a text depends also on the words surrounding them (again, to take ‘migration’ as an example, this could be seen as an opportunity or a threat for a country, depending on the context in which the word is used). In this sense, we are mixing analytical methods to ‘overcome research errors, involve both representative samples and close attention to contexts, and allow researchers to test results from one analysis using another’ (Parks and Peters Reference Parks and Peters2023: 380).

Results

In this section, we discuss our main findings, country by country, before considering the overall results and their implications in the conclusion. As we show, while right-wing populist leaders' distinctive vocabularies have almost no words in common, they do all contain words reflecting the ‘people versus elites and others’ pillars of right-wing populist ideology. They also reflect, to different degrees, some of the main features of populist style, such as directness.

United States

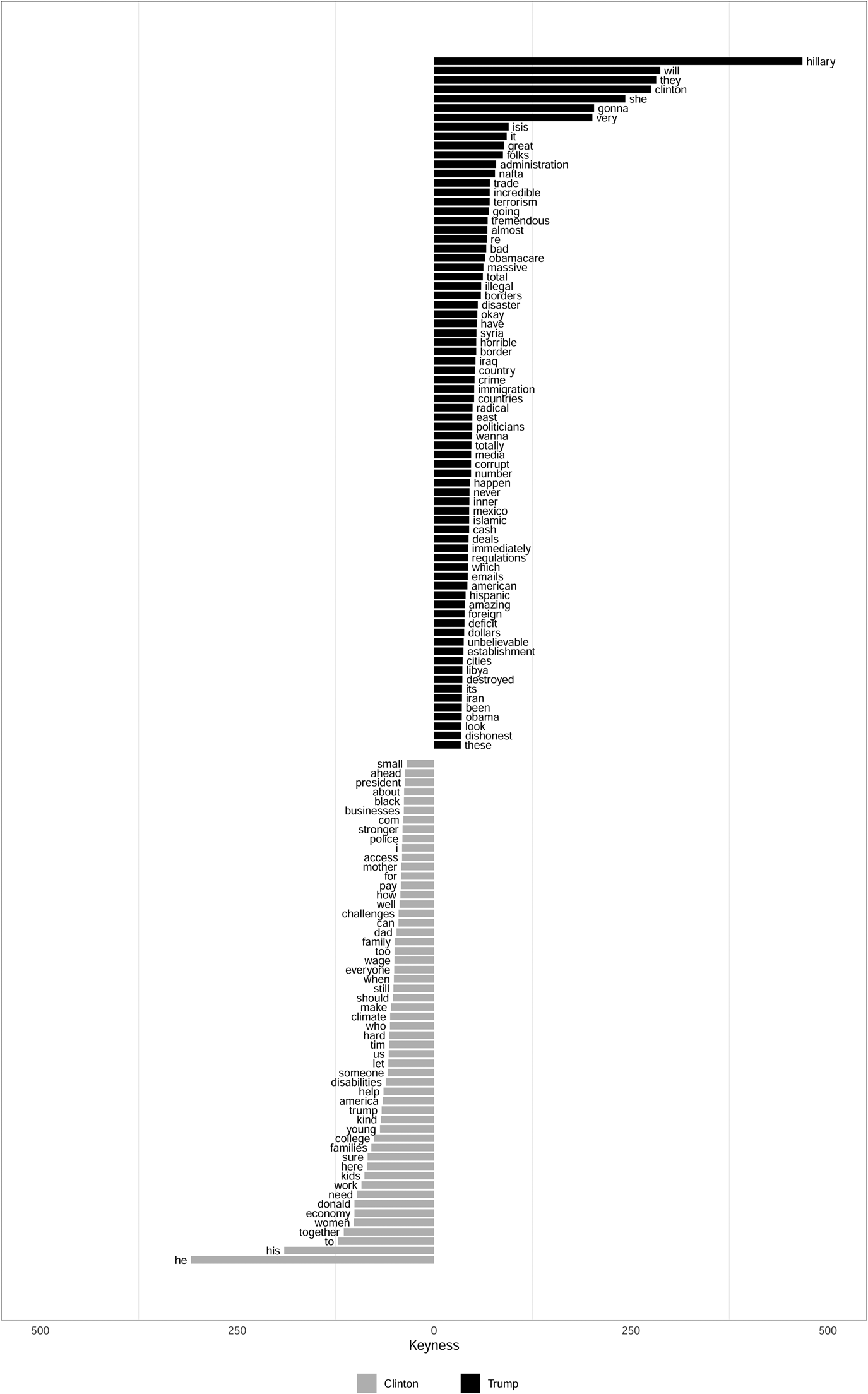

Figure 1 reports the keywords of Trump and Clinton.Footnote 17 As explained, these are words that appear with unusual frequency in one leader's corpus of speeches compared to the other. Trump has 74 keywords that distinguish him from Clinton, while Clinton has 54 that distinguish her from Trump. The results are in line with what we would expect from two leaders, of whom one is right-wing populist and the other centre-left. Trump's keywords include many which seem likely to reflect the core elements of right-wing populist ideology such as establishment, corrupt, dishonest, politicians, media, Mexico, Islamic, Isis, terrorism, immigration, illegal, border and crime, but also dramatic words that reflect populist style, such as tremendous, totally, horrible, disaster, incredible, massive, amazing and unbelievable.Footnote 18 By contrast, Clinton's keywords are not suggestive of populist ideology or style and, overall, appear to reflect inclusive ideas about different groups in society collaborating for mutual benefit (together, kids, families, mother, young, black, disabilities, help, everyone).

Figure 1. Trump and Clinton Keywords

While the results in Figure 1 suggest that Trump's vocabulary is distinguished by keywords related to right-wing populist ideology and style, we cannot say with certainty that all keywords are indeed serving those functions (for example, Trump could theoretically be talking about immigration as a positive phenomenon that enriches US society). To confirm how keywords are used, we therefore need to look at their contexts. This second level of analysis confirms that not all keywords in Figure 1 are indicative of relevant semantic patterns or stylistic choices. In Trump's case, been, have, it, its, which, re (i.e. the contraction of ‘are’) and these are stop words which do not convey or indirectly contribute to any specific meaning. We can therefore discard them as the result of idiolectal preferences. Similarly, while we thought when initially looking at the keyword list that they might contribute to the articulation of a populist Manichean worldview of ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), no such use was evident.

Nonetheless, our analysis of the concordances shows that many of Trump's keywords are indeed linked to the three main pillars of right-wing populist ideology (good people, bad elites, dangerous others) and/or convey a populist style. These relevant keywords also include stop words that did not immediately stand out. For example, while she could denote innocuous references to Trump's 2016 opponent, our analysis of the concordances featuring she shows multiple instances of Clinton being cast as one of the worst examples of the bad elites comprising politicians and the Washington establishment. Across Trump's speeches, she is consistently associated with words such as corrupt, dishonest, ‘unfit’, ‘a cheat’, ‘a criminal’ and ‘a monster’. This populist view of political competition, in which one does not have adversaries, but enemies, is evident in statements combining right-wing populist ideology and dramatic rhetorical style such as ‘she is a dangerous liar who has disregarded the lives of Americans’ and ‘she is unhinged, she's truly unhinged, and she is unbalanced, totally unbalanced’. The same negative connotations are also present when Trump refers to media, who, like Clinton, are labelled as dishonest, corrupt, and crooked.

Our initial impression that Trump's keywords contain many references to ‘dangerous others’ is confirmed by the concordance analysis. For example, when he refers to Mexico and immigration, these are linked to the idea that the American people's safety and prosperity are being undermined. Mexico is portrayed as an economic threat due to US jobs allegedly being moved south, while immigration is consistently associated with illegal and ‘criminal’. As Ruth Wodak (Reference Wodak2021: 6) argues, this is the ‘politics of fear’ of the populist right, which instrumentalizes ‘some kind of ethnic, religious, linguistic, or political minority as a scapegoat for most if not all current woes in society’. Consistent with this, foreigners are also a security threat, especially if they are Muslim, as underlined by Trump's references to radical Islamic terrorism and Isis. Finally, although we find fewer keywords clearly referencing the ‘good people’ than is the case for ‘bad elites’ and ‘dangerous others’, our examination of the concordances reveals how some keywords serve that function. For example, Trump associates references to the American people with the pronoun ‘you’ in order to address the people directly. He includes among this people ‘workers’, ‘community’, ‘children’, ‘citizens’, ‘youth’, ‘families’ and ‘households’. We find a similar function for country. Over half of these utterances by Trump refer to ‘our country’, while others point explicitly to the populist idea of the people as the only true sovereign. For example, when talking about supreme court nominations, Trump says, ‘And [when] you pick the wrong people, you have a country that is no longer your country.’

Our examination of concordances reinforces the impression that Trump's keywords strongly reflect not only right-wing populist ideology, but also style. Notably, he uses a range of words to strengthen or emphasize a concept and demonstrate confidence in what he is saying: adjectives are preceded by very or totally, verbs are followed by immediately, and nouns (such as America, individual states of the US, and people) are modified by amazing, great, incredible, unbelievable and tremendous. Similar linguistic items are used to strengthen the criticism levelled at the enemies of the people as in bad (especially Clinton) and horrible trade deals, while total is used to emphasize negative concepts such as disaster, ‘betrayal’, ‘blowout’, ‘catastrophe’, ‘chaos’, ‘corruption’, ‘destruction’, ‘disgrace’, ‘disrepair’, ‘fabrication’ and ‘violation’.

Although our focus is on the keywords of right-wing populist leaders, it is useful for comparison to look also at those of their mainstream opponents. In contrast to what we saw in the case of Trump and his use of she, Clinton does not seem to be so preoccupied with her rival: keywords like he and his in fact do not always refer to Trump and, although his name and surname are keywords, they are rarely associated with aggressive epithets akin to those that Trump used about her. The most important topics Clinton's keywords refer to concern inclusion and solidarity (rather than Trump's ‘good people’ vs ‘dangerous others’ frame). This is manifest if we look at the contexts in which we find generic words such as everyone, someone, together, help and let (e.g. ‘let's make college affordable and available to all’). Similarly, a keyword like America is not used in contrast with the interests of other countries (such as, for Trump, China or Mexico), but in phrases like ‘America is better than this’ and ‘America is great because America is good’. Rather than an exclusive people, facing a range of internal and external enemies, Clinton's America is a community that can be stronger together.Footnote 19 It is an America that is diverse and includes women, the young, black people and (people with) disabilities. Noticeably, Clinton's linguistic style choices convey a more tentative attitude than Trump's.Footnote 20 If we look at modal and auxiliary verbs, Trump's confidence is apparent in his frequent use of will and going to or gonna, particularly in the first person, both singular and plural, while Clinton opts for a more cautious use of can (both we and you), should and need.

France

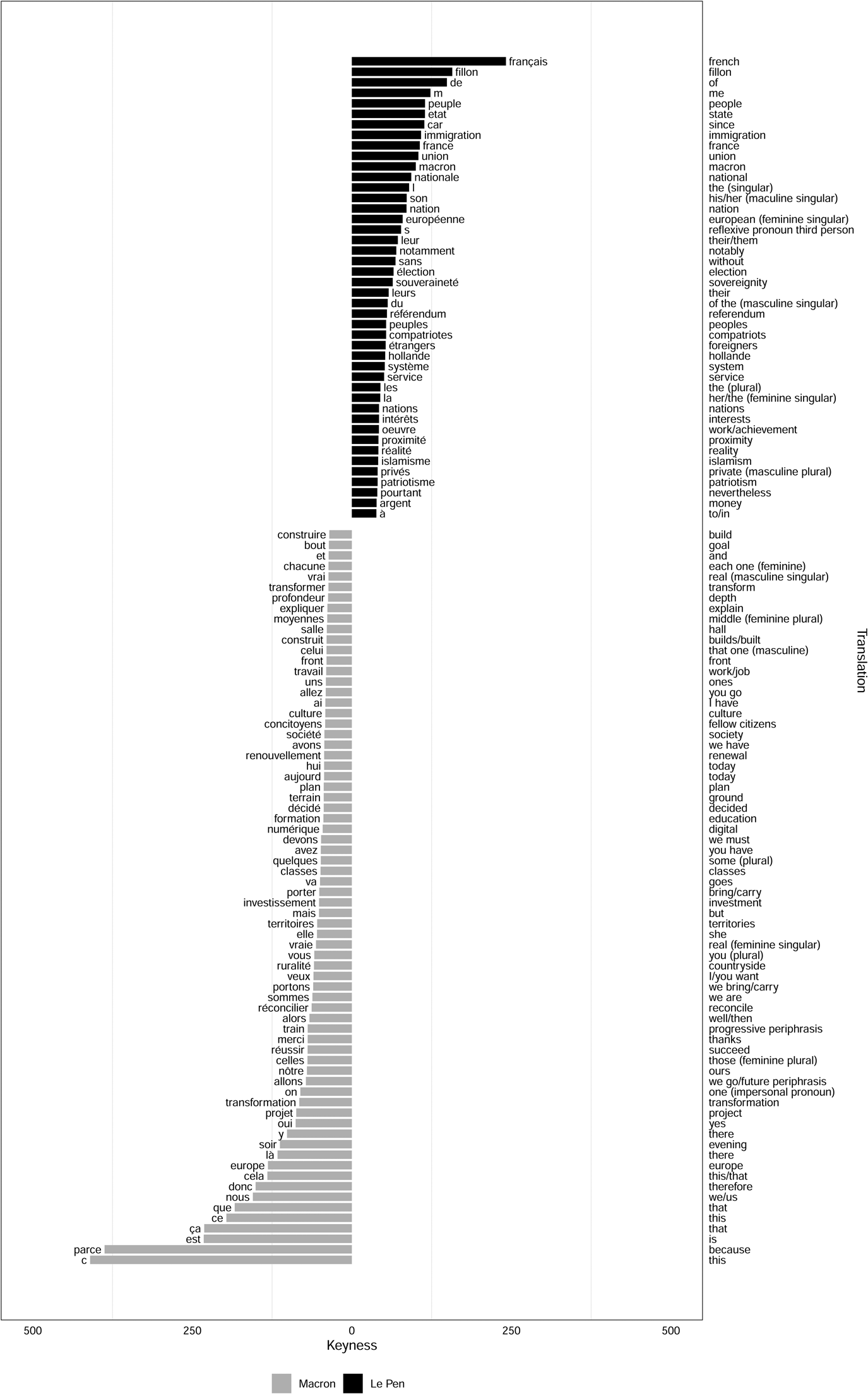

We now move on to the keywords of our French cases, Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron. Figure 2 lists Le Pen's 44 keywords and Macron's 70.Footnote 21 As was the case with Trump, Le Pen's keywords appear to reflect right-wing populist ideology, including clear references to a sovereign French people with terms like F/français (French), peuple (people), nation, national, compatriotes (compatriots), patriotisme (patriotism) and souveraineté (sovereignty). They also contain indicators of the other two pillars of right-wing populist ideology. Words like immigration, étrangers (foreigners) and islamisme (Islamism) all suggest ‘dangerous others’, while union, européenne (European), Hollande (François Hollande, the former centre-left president), Fillon (François Fillon, a leader of the centre-right), and Macron are likely ‘bad elites’. Notably, while Macron appears among Le Pen's keywords, neither she nor any other politician are among his, leading us to suspect that she focuses more on her opponents than he does. Although her main topics appear clear, there is far less of the immediate sense we had with Trump that dramatic language is a distinguishing feature of her vocabulary. As for Macron, unlike Le Pen, his keywords convey vagueness, with many generic and aspirational notions like projet (project), transformation, plan, réussir (succeed) and renouvellement (renewal), but little concrete apart from, possibly, Europe.

Figure 2. Le Pen and Macron Keywords

Our analysis of Le Pen's concordances confirms these initial impressions. The main distinguishing characteristic is her focus on the good French sovereign people. Notably, she uses France twice as often as Macron, français (French) over three times as often, and peuple (people) over four times as often. The clusters also show how she frequently refers to ‘notre peuple’ (our people), ‘au nom du peuple’ (in the name of the people), ‘la parole au peuple’ (giving the people a say), thus framing the people as sovereign. Similarly, she refers to her compatriots (compatriots), who are devoted to their nation, but whose souveraineté (sovereignty) is threatened by domestic and international elites. Among the former, Hollande, Fillon and Macron are mentioned together on occasion to convey the typically populist idea that all other politicians are the same (Taggart Reference Taggart2000: 100). Again, reflecting the right-wing populist attention to the dangers posed by non-natives, immigration is associated in the concordances with the adjectives ‘massive’, ‘clandestine’ and ‘illegal’. Similarly, étrangers (foreigners) is negatively linked with ‘criminals’ and ‘low-cost labour’.

As regards style, and in contrast to what we saw in the case of Trump, Le Pen's speeches do not appear to be characterized by dramatic language, but they are more to-the-point than those of her domestic opponent. Her keywords tend to be associated with the three pillars of right-wing populism and exceptions to this are usually stop words stressing her effectiveness and matter-of-factness. As part of this self-presentation, and in line with charismatic populist leaders (McDonnell Reference McDonnell2016), Le Pen casts herself as the leader who sees ‘how things really are’ (and can therefore identity the solution to problems). This is underlined by her use of clusters such as ‘en réalité’ (in reality) and ‘et pourtant’ (and yet). Le Pen's message is that she is there to open her audience's eyes and speak hard truths about the key issues.

Macron is much more nebulous. His speeches are characterized by keywords which do not convey any specific meaning, such as porter (to bring) and vivre (to live), or sketch a vague notion of the future, for example nouns like plan, projet (project), transformation and renouvellement (renewal), and verbs like réussir (succeed), construire (build) and transformer (transform). Notably, these words remain undefined even when modified by emphatic adjectives: for example, he talks about ‘un vrai projet’ (a real project), which does not, however, convey any specific meaning. If we look at the stop words among Macron's keywords, we can see that, unlike Le Pen, he uses the feminine form of pronouns such as celles (those) and chacune (each) alongside their masculine forms in order to ensure inclusive language. He also makes the information structure explicit by means of logical connectors – parce que (because), donc (consequently), alors (then); also in combination with oui (yes) as in donc oui, alors oui, while mais (but) is used to introduce alternatives and exploits demonstratives to build cleft sentences that are, by design, less to-the-point. For example: c'est cela, c'est ça, c'est celui and so forth, as in ‘C'est cela, ce dont nous avons besoin: un projet pragmatique qui sera le fruit d'une concertation avec les territoires et d'un vrai développement’ (That is what we need: a pragmatic project to be devised through negotiation with local administrations and real development).Footnote 22 Compared to Le Pen, Macron devotes a lot more energy to packing vague notions into a more elaborated linguistic wrapping that is meant to highlight the structure rather than the contents of his speech. By contrast, Le Pen's keywords are more content-oriented, with very few stop words and connectors, most of which (e.g. car – since/because) are used to provide explanations of the topics she focuses on.

Italy

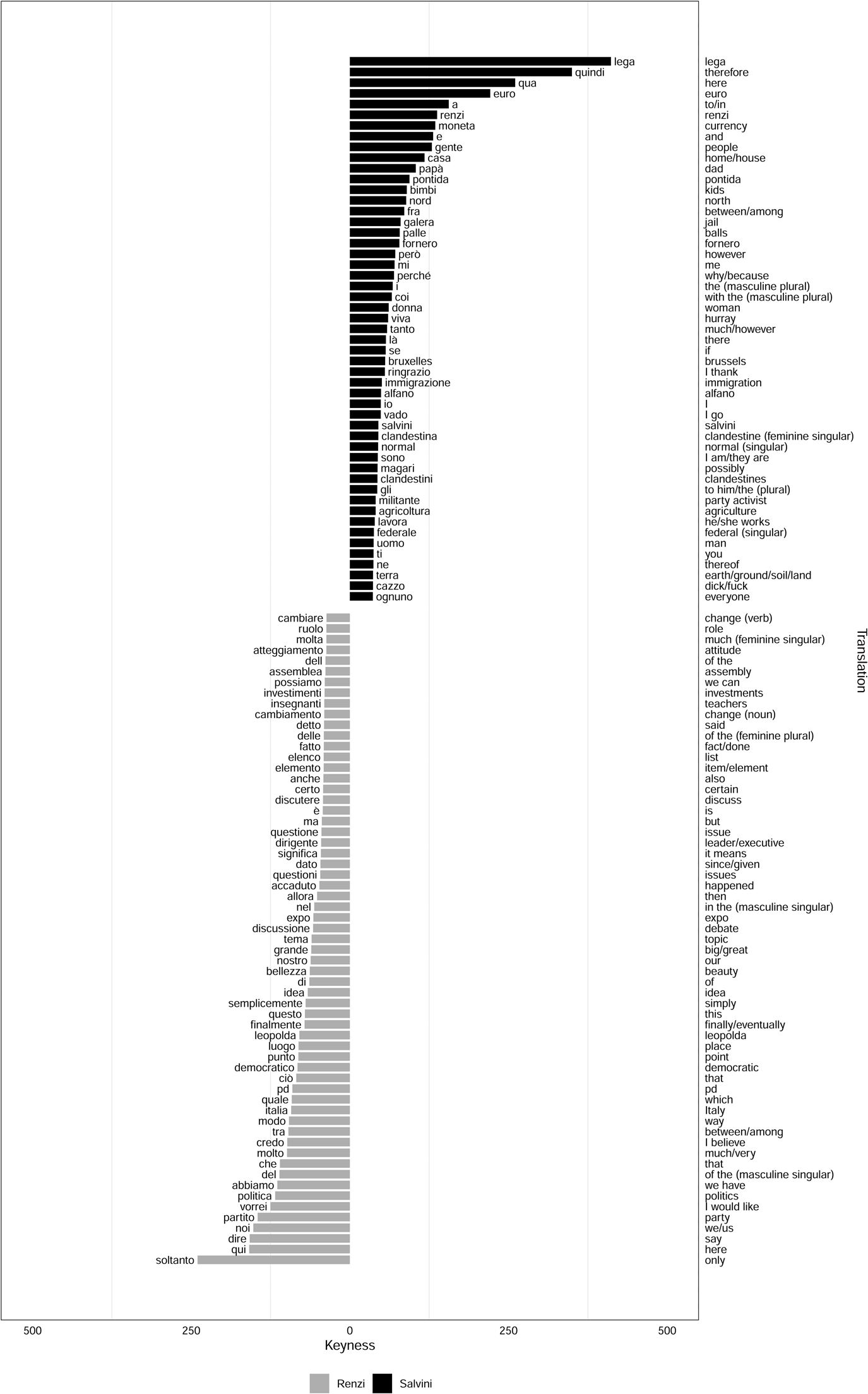

Finally, we examine the keywords of two Italian leaders, Matteo Salvini of the Northern League and Matteo Renzi from the Democratic Party (PD – Partito Democratico). Figure 3 lists Salvini's 51 keywords and Renzi's 61.Footnote 23 Similar to Trump's, Salvini's keywords are strongly suggestive of both right-wing populist ideology and populist style. We find words likely to denote a ‘good people’ such as gente (people) and casa (home), along with ‘bad elites’ such as his political opponents, Renzi, Fornero and Alfano, in addition to Bruxelles (Brussels – meaning the European Union).Footnote 24 Similarly, keywords like immigrazione (immigration) and clandestina/clandestine (clandestine) appear to indicate ‘dangerous others’.

Figure 3. Salvini and Renzi Keywords

In terms of populist style, for the first time among our cases, we find vulgar terms among the right-wing populist leaders' keywords, with Salvini's list including palle (balls) and cazzo (dick/fuck). As we saw in the French case, here too it appears that the right-wing populist leader has more concrete terms signalling clear topics among their keywords than their mainstream rival. Renzi also has many words which do not seem connected to political themes (e.g. bellezza – beauty), along with numerous verbs and nouns regarding the need for discussion such as dire (to say), discutere (to discuss), tema (theme), questione (issue), punto (point).

Our analysis of Salvini's concordances confirms that, as we have seen in the cases of Trump and Le Pen, his distinctive vocabulary contains many keywords reflecting the three pillars of right-wing populist ideology. For Salvini, the good people (he prefers the folksier gente to its synonym ‘popolo’) are those who want to live in a country that is normale (normal), in traditional families composed of a uomo (man) and a donna (woman), and bimbi (kids). Even though the League had already begun its transformation from a northern regionalist party to a nationwide right-wing populist one under Salvini by the time of these speeches (Zulianello Reference Zulianello2021), it is notable that, in contrast to Le Pen, Salvini does not have the national community (‘Italy’ or ‘Italians’) among his keywords but he does have nord (north).Footnote 25 In fact, Italia (Italy) is one of Renzi's keywords, underlining how much more that term is used by Salvini's rival. Generally, we find that Salvini prefers to evoke ideas of the people's community that are more immediate such as casa (home) and terra (land), with usages such as casa nostra (our home), but also casa ‘tua/sua’ (your/one's own home – the latter referring to immigrants who should return to their own homes). As for the enemies of the people, these are comprised of elites and others. In addition to his domestic rivals, the former particularly include those in Bruxelles (Brussels), who are variously described as ‘cretini’ (cretins), ‘stronzi’ (assholes) and, more kindly, as ‘burocrati’ (bureaucrats), while the latter are linked to immigrazione (immigration), with the concordances showing that clandestina (clandestine) is associated with this word on 45 of its 69 occurrences.

As regards populist style, Salvini is the right-wing populist leader of our three who makes most use of vulgarity.Footnote 26 He says palle (balls) 56 times, with examples including criticizing a political opponent as not having ‘the balls to say: “let's leave the Euro”. Well, we have the balls to do so and we say it with courage’, but also praising his right-wing populist counterpart in France: ‘I met Marine Le Pen. She's a woman with two huge balls.’Footnote 27 Cazzo (dick), which appears 21 times, is used both as an exclamation (akin to ‘fuck’ in English), but also to denigrate Salvini's adversaries. For example, he says ‘agli altri lasciamo i professori del cazzo alla Mario Monti e noi abbiamo la gente vera’ (we'll leave those fucking professors like Mario Monti to others. We have the real people) and ‘Renzi twitta dalla mattina alla sera. Peccato che poi non fa un cazzo’ (Renzi tweets from morning to evening. Pity he then doesn't do a fucking thing).Footnote 28 In addition to vulgarity, Salvini also employs colloquial terms. For example, one of his keywords is galera (jail): originally a galley with rowing slaves, today the word is colloquially used to refer to a life sentence, as Salvini does several times when he says ‘ti metto in galera e butto via la chiave’ (I'll send you to jail and throw away the key).Footnote 29 Finally, Salvini's keywords show his liking for lexis that is either ameliorative or pejorative, rather than neutral, in line with populists' preference for more emotional rhetoric (Canovan Reference Canovan1999) and the avoidance of dry technocratic language (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016: 143). For example, Salvini's keywords include the affectionate bimbi (kids) rather than ‘bambini’ (children) or ‘figli’ (sons and daughters), often included in his description of a traditional family with papà (dad) and ‘mamma’ (mommy).

As for Renzi, our concordance analysis shows that he is a lot less to-the-point than his right-wing populist opponent. Much like Macron, and unlike Salvini, Renzi's keywords do not refer to specific topics but mostly convey fuzzy concepts – for example, atteggiamento (attitude) and bellezza (beauty), used in sentences like ‘restituire dignità e orgoglio e bellezza alla politica’ (restore the dignity, pride and beauty of politics). Similarly again to his French counterpart, Renzi tends to speak in abstract and aspirational terms about the future with keywords like cambiare (change – verb) and cambiamento (change – noun), but without specifying what these really entail. At the same time, he emphasizes that he wants to be clear (without actually being so). We thus find frequent clusters like: ‘vuol dire’ (it means) and ‘voglio/vorrei dire’ (I mean/I wish to say), along with adverbs such as semplicemente (simply) and molto/molta (very), included in expressions like molto semplice (very simple), molto chiaro (very clear), molta chiarezza (great clarity), molta franchezza (great openness) and so on. Likewise, Renzi keeps reminding his audience of the need to discuss (discutere and discussione) issues and ideas (idea, tema – theme, questione – question/topic), while at the same time not appearing actually to present concrete issues as Salvini does.

Conclusion

Word choices matter. While right-wing populists have long been believed to use distinctive language that distances them from mainstream political elites, we know little about the word choices that make their vocabularies distinct (Canovan Reference Canovan1999; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016; Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011). In examining pairs of right-wing populists and their principal mainstream opponents, we envisaged that their ideology and populist style would be expressed through the word choices that they and their advisers make when writing texts and delivering speeches. As our study has shown, Trump, Salvini and Le Pen are indeed distinguished from their non-populist opponents by keywords that reflect the three pillars of right-wing populist ideology (good people vs bad elites and dangerous others) and some, but not all, aspects of populist style. Right-wing populism as an ideology thus appears as a concept with elements that are set in stone, which we duly find in all three leaders' distinctive vocabularies. Populism as a style, however, appears more, as Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2017: 361) puts it, a repertoire which political actors can choose from.

Our results underline the theoretical utility and complementarity of viewing right-wing populism both as an ideology (with three fixed pillars), and as a style (with more flexible features), rather than primarily one or the other. In fact, while we have shown that there are similarities in how leaders express right-wing populist ideology and style in different languages, we have also uncovered differences as regards the latter. Notably, the dramatic tones of Trump and Salvini, whether expressed through hyperbole or vulgarity, were not features of Le Pen's distinctive vocabulary.Footnote 30 To be sure, individual personalities obviously play a role and so, perhaps controversially for those from the ideational approach, who adopt a binary rather than a gradational conception of populism, it may be that some leaders are simply stylistically ‘more populist’ than others. This could be a constant feature, or it could vary according to circumstances (for example, when seeking to prove one's ‘good behaviour’ to the public and/or potential coalition partners). We therefore agree with Moffitt (Reference Moffitt2016: 46), who argues that a merit of the political style approach is it ‘acknowledges that political actors can be more or less populist at certain times’ (emphasis in original).Footnote 31

Our research also contributes to thinking about how we study populist vocabulary. When creating the first multilingual populist dictionary, Rooduijn and Pauwels (Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011: 1276) proposed that, because populists in different languages made the same argument, they would use similar words. However, we have found that, although right-wing populist leaders do indeed make the same ideological argument, the distinctive words used to convey it are different across our English, French and Italian cases. Strikingly, ‘elite’ – the only word common to all the dictionaries in English, Dutch, French, German and Italian which we discussed earlier – did not appear among any of our right-wing populist leaders' keywords.Footnote 32 While we do not discount the value of deductive, dictionary-based approaches for identifying populism, our study shows how inductive approaches can be helpful when studying populist communication. In particular, the specific method of keyness analysis to uncover distinctive vocabulary could be usefully applied to other pairs of leaders such as populist incumbent versus populist challenger; left-wing populist versus mainstream centre-left; left-wing populist versus right-wing populist; and so on. Like dictionary-based approaches, this method also has the advantage of being replicable.

Finally, our research sheds light not only on the distinctive vocabularies of right-wing populist leaders compared to mainstream ones, but also on what distinguishes mainstream leaders' appeals from those of right-wing populist ones. Our analysis thus provides a unique perspective on the specificities both of the right-wing populist challenge and of the mainstream response. Overall, it is the right-wing populist leaders who appear more to-the-point. As we have seen, their messages already emerge clearly from their keywords, even before we check the contexts in which they are used. By contrast, Macron and Renzi's distinctive vocabularies were characterized by vagueness. In fact, it is quite difficult to discern those two leaders' ideologies from their keywords – something which may speak to the general crisis of mainstream politics in Europe amidst the rise of populism (Berman and Snegovaya Reference Berman and Snegovaya2019; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2019). If what makes right-wing populist vocabularies distinct is their focus on core themes and their directness, what makes mainstream ones distinct in our European cases is nebulous aspiration and obfuscation. Or, to put it another way, while we have debunked the long-standing claim that populists are characterized by linguistically simpler language in our previous work (McDonnell and Ondelli Reference McDonnell and Ondelli2022), our study here supports the idea that what distinguishes the speeches of right-wing populist leaders is the simplicity and clarity of their message compared to that of their opponents.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2024.10.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following colleagues who provided valuable advice and assistance during the development of this research project and article: Sofia Ammassari, Paris Aslanidis, Ferran Martinez i Coma, Max Grömping, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Benjamin Moffitt, Lee Morgenbesser, Paolo Nadalutti and Arjuna Tuzzi. We are also very grateful to the interpreting and translation students at the University of Trieste who helped with the data collection, and to Julian Nikolovski who provided technical assistance. Finally, Duncan McDonnell would like to thank the Australian Research Council for supporting his research on populism with a Future Fellowship award (FT210100617).