How do ethnically divided countries balance demands for autonomy with objectives of stability and national unity? Why do some kinds of federalism fail while others evolve? Scholars looking for answers to these kinds of questions have tended to focus on the West. Yet there are important lessons arising from the substantial democratic and federal reforms that have taken place in Asia over the last decades. In the last few years alone, Nepal has established a new federal democratic constitution; Myanmar elected a new government and established a federal constitutional reform process; Sri Lanka and the Philippines both established constitutional reform committees tasked with designing new federal or quasi-federal structures. Federalism was well-established in the region long before this time. India, Malaysia and Pakistan have all been federations since independence, while even though the ‘F’ word is avoided in Indonesia, its constitution too now incorporates many federal features. What can we learn from their experiences and what does it say about how to create inclusive democracies in divided societies?

Just over a decade ago, Benjamin Reilly (Reference Reilly2007) wrote that an ‘Asian model’ of electoral democracy was emerging comprising mixed-member majoritarian electoral systems and aggregative party systems. This was argued to be motivated by aims for increasing government stability, reducing party fragmentation and minimizing the potential for new entrants. Reilly based his conclusions on an analysis of democratic reforms in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand. However, he noted two outliers – the Philippines and Indonesia, arguing that their diversity and their shift from authoritarian systems can explain the differences (Reilly Reference Reilly2007: 1367). In particular, the Philippines and Indonesia have moved in an opposite direction to the other cases, by introducing proportionality to their electoral systems and experiencing an increase in party fragmentation. This article argues that in fact the Philippines and Indonesia are not outliers in Reilly's model, but part of an ‘Asian model of federal democracy’ which can be contrasted to the unitary model that Reilly has identified. This federal model reveals a new approach to achieving democratic stability while accommodating diversity in deeply divided countries, which runs counter to the dominant paradigm, consociationalism, that focuses on proportionality and consensus (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977; McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, O'Leary, Simeon and Choudhry2008), and its competitor, centripetalism, which is majoritarian and thought to be incompatible with consociationalism (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000a). This is because, inter alia, multi-ethnic political parties have been able to bridge ethnic cleavages without undermining the inclusion and autonomy of minority ethnic groups.

To demonstrate this, this article identifies, analyses and compares the changes in, and interdependent effects of, different electoral systems, party systems and federal systems. It applies a historical-comparative analysis, combining qualitative and quantitative data and a most similar systems approach, that focuses on the evolution and interaction of federal, party and electoral institutions in eight ‘federal democracies’ in Asia, namely India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines and Sri Lanka.Footnote 1 These countries are structurally similar, having a federal system and substantive ethnic diversity, but with important variations in political party and electoral systems over time. Each of these countries is what is known in the literature as a divided society, because ethnic identities are politically salient. Their relationship is one of family resemblance, whereby members have a minimum level of shared characteristics rather than certain necessary or sufficient conditions (see Goertz Reference Goertz2006: 27–68). I focus on the period from independence or the establishment of the modern state (usually around 1948) up to 2019.

Using these cases, I show that in ethnically divided countries in Asia, majoritarianism and ethnofederalism are being combined such that regional and ethnic parties provide an important counterbalance to the national and aggregative (multi-ethnic) parties. This vertical hybridity achieves the benefits of both a strong centre and ethnic autonomy. It is supported by a shift towards more proportionality in electoral systems and more party fragmentation. Together, this means that executives in the region are almost invariably coalition governments, and – in most cases – post-election coalitions combining ethnic and multi-ethnic parties. These outcomes are contrary to dominant theories that argue that majoritarianism leads to two-party systems and that party fragmentation declines as the party system becomes more structured as a result of democratization. Further, the model displays higher levels of democratic stability than earlier alternatives and is ethnically inclusive. With the model in place, none of the cases has reverted to authoritarianism, experienced a successful coup or seen the commencement of a major civil conflict. It thus demonstrates a complementary and coherent combination of consociational and centripetal elements that augurs a middle path between these two competing and supposedly incompatible theories.

Federalism, political parties and electoral systems

Federalism is the contemporary demand of many minority ethnic groups in Asia, and governments are increasingly acting in response (Bertrand and Laliberte Reference Bertrand and Laliberte2010; Breen Reference Breen2018a; He et al. Reference He, Galligan and Inoguchi2007). I adopt a definition of federalism following Ronald Watts (Reference Watts1999: 6–14), who distinguishes between federalism, as ideology, and federal systems, as institutions, which may include federations, constitutionally decentralized unions and federacies (among others). A further distinction is made between territorial federal systems and ethnofederal systems. A territorial federal system is characterized by provinces that are based on geographic and economic factors, and liberal neutrality or equal rights (Brown Reference Brown, He, Galligan and Inoguchi2007).Footnote 2 Ethnofederal systems have one or more provinces based on identity and there are special or asymmetrical rights for certain ethnic groups or provinces (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka, He, Galligan and Inoguchi2007). There are several ethnofederal subtypes, including ethnoterritorial federal systems, where one or more territorially concentrated ethnic groups are accommodated via the provision of a province, but the numerically dominant ethnic group is split across multiple provinces (Anderson Reference Anderson2013: 7).

Based on the Watts (Reference Watts1999) typology, there are nine federal systems in Asia, encompassing three generations. The first generation are the ‘quasi-federations’ of India, Malaysia and Pakistan, established at independence following decolonization. The second generation comprises otherwise unitary states with important federal features, namely constitutionally protected local or provincial government and special autonomy (China, Philippines, Indonesia). The third generation are the emerging or aspiring federal states of Nepal, Myanmar and Sri Lanka (see Breen Reference Breen2018a: 37–48). Democracy here refers to an electoral democracy. A prominent measure of this concept of democracy is provided by the Polity5 project (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2019). Based on this, eight of the nine Asian federal systems can be classed as a democracy, each scoring at least 7 out of a possible 10 for institutionalized democracy (DEMOC) in the 2019 report. I include them in the study even if they have not been democratic in the recent past or have significant democratic deficits. I thus exclude China from this comparison as it is not and has not been an electoral democracy (Polity5 assigns it an institutionalized democracy score of 0). I retain Sri Lanka in the analysis, even though its federal practices have diminished over the last two years to the extent that five of its nine provincial councils have been without elected representatives for much of that period (as at July 2020). The outcomes of its most recent elections (2019 presidential and 2020 parliamentary) have also reinforced its unitary status, placing further federalization on indefinite hold.

Federalism, political party systems and electoral systems are closely intertwined and integral to the democratic regulation of ethnic conflict. According to Duverger's Law, proportional representation (PR) electoral systems lead to multiparty systems (more fragmentation) and coalition governments, while plurality-majority electoral systems lead to two–party systems. It follows that the latter will tend to have more stable governments. However, Duverger's Law has since been highly qualified. In particular, Giovanni Sartori (Reference Sartori1997: 39–73) showed that the effect of electoral systems differs according to the conditions in which they are implemented. For example, a plurality electoral system will cause a two-party system only if there is ‘cross-constituency dispersal’. Further, Sartori demonstrated that that the laws only apply when the party system is structured (institutionalized) – and claimed this only occurs in a consolidated democracy. In Asia, however, party system institutionalization does not always follow democratization, and many of the most institutionalized party systems in the region have authoritarian antecedents (Hicken and Kuhonta Reference Hicken, Kuhonta, Hicken and Kuhonta2015).

I adapt Reilly's (Reference Reilly2007) approach to electoral systems, which distinguishes between plurality-majority (first-past-the-post – FPTP), PR, mixed-member proportional (MMP) and mixed-member majoritarian (MMM). It is MMP or MMM depending on whether the proportion of seats decided under a plurality formula is less or more than the number of seats decided by a PR formula (or by reservations) or is MMP if the PR component is compensatory rather than parallel to the plurality component (see Reilly Reference Reilly2007: 1359–1360, n.9 1386). Further, a presidential system is a fundamentally majoritarian approach to the distribution of executive power (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999; Stepan et al. Reference Stepan, Linz and Yadav2011: 13). A presidential system with PR in the legislature is mixed-majoritarian.

For party systems, I apply and adapt the typologies of Jean Blondel and Arend Lijphart (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999: 63–67). They classify according to the effective number of parliamentary parties (ENPP), which measures both the number and size of parties.Footnote 3 Based on a distinction between ethnic parties and aggregative parties, I then classify systems as ethnic, multi-ethnic or mixed. A mixed party system must have at least one relevant party (as per Sartori Reference Sartori1977) of each type. Aggregative parties seek votes and support from all sectors of society, whereas ethnic parties seek the support of members of their respective ethnic group. For aggregative parties, I apply categories of multi-ethnic and non-ethnic, noting that in Asia, non-ethnic parties have tended to be ethnic parties of the dominant group (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000b; Reilly Reference Reilly2001). A party is multi-ethnic if it appeals to, and seeks the votes of, multiple ethnic groups, without excluding any ethnic groups (Chandra Reference Chandra2011).Footnote 4 This is indicated by its policy platforms and rhetoric, its selection of leaders and its name (Chandra Reference Chandra2011; Ishiyama and Breuning Reference Ishiyama and Breuning2011).Footnote 5

Political party systems are integral to the operation of federalism (Riker Reference Riker1964) and the regulation of ethnic conflict. However, ethnic parties often foster conflict, and once an ethnic party system is established, it is very difficult to change (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000b: 291–349). Advocates of centripetal approaches, such as Horowitz (Reference Horowitz2000b) and Reilly (Reference Reilly2006), highlight the moderating effects of two-party systems and multi-ethnic parties and coalitions. Herein lies their primary disagreement with advocates of consociationalism. Consociationalism aims to empower the extremes by establishing a power-sharing regime between different ethnic groups (see Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977, Reference Lijphart1999). It assumes and exalts an ethnic party system and PR electoral systems. Other key features are a grand coalition executive and a minority veto. But what happens where there are also multi-ethnic parties? A society may be deeply divided but still able to find a political centre through the party system. Centripetalism, the main competing prescription for divided societies, also assumes ethnic parties but aims to incentivize moderation through the design of institutions that embed reciprocity and inter-ethnic exchange, and encourage or mandate aggregative party systems (Reilly Reference Reilly2012). However, according to Donald Horowitz (Reference Horowitz2000b: 362–364), in a deeply divided society, ‘there is room for only one multiethnic party or alliance’ (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000b: 410) because competitor parties are left with little option but to appeal to ethnic interests and extremes, and there is a high risk that such a party will resort to undemocratic means to maintain power (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000b: 429–437).

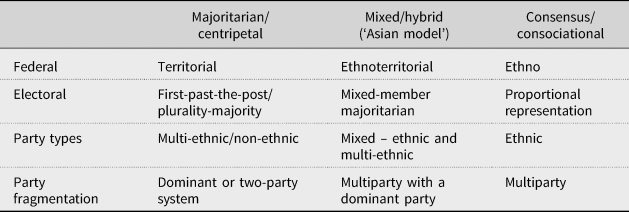

The cases of federal Asia show that it is possible to have more than one multi-ethnic party as viable contestants for power, while at the same time accommodating ethnic parties. Indeed, it is possible to engineer such an arrangement. Ethnic parties have space to compete and govern in ethnically based federal provinces, and a role to hold large multi-ethnic parties to account. Meanwhile, smaller ethnic groups have a presence in multi-ethnic parties, and their own special structures to minimize the risks of further marginalization under ethnic federal structures. The conceptual framework outlined above is simplified in Table 1, which categorizes the institutions according to their alignment with consociational and centripetal approaches.

Table 1. Summary of Types of Federal, Electoral and Party Systems Classified According to their Basic Alignment with a Majoritarian or Consensus-Based Democracy

Multilevel ethnoterritorial federalism

Since the establishment of the modern state in the eight deeply divided electoral democracies in Asia, there has been an overall positive federalization trend and an increasing extent of ethnofederalism, especially over the last 10 years. The overall trends in these eight countries in Asia is displayed in Figure 1 and discussed below.Footnote 6 They do not all have ‘federalism’, being an ideology discernible by practice as well as rhetoric, and they remain quite centralized, consistent with their holding-together origins. But each does have a federal system of at least two tiers of constitutionally protected government, each with powers derived from the constitution or other basic law. Most have three tiers of constitutionally protected government. Each also has an independent umpire (more or less) to adjudicate between jurisdictions and interpret the constitution. Other common features of federal systems exist in some of the countries but not others, such as bicameralism and institutions for intergovernmental cooperation. None of these countries is a federation in the classical sense. They are, according to Watts's criteria (Reference Watts1999: 8–9), quasi-federations or constitutionally decentralized unions. In each case, the centre has some intervention or override powers, which they have proven willing to exercise.

Figure 1. Federalism and Ethnicity in Units in Eight Countries in Asia, 1948–2018

Another feature is their development of ethnofederal systems – specifically, ethnoterritorial federal provincial designs. Each of their federal systems has become more ethnically based, and balanced, as all except for Pakistan have split the dominant ethnic group across multiple provinces to establish an ethnoterritorial federalism. To offset the more heterogeneous federal provinces, autonomous areas have been created to resolve conflict, special structures for small minority groups have been established and local government has been strengthened. We can see this occurring across each generation of federalism. The original provinces of the first-generation countries, India, Pakistan and Malaysia, had a British colonial legacy. But in each case, substantial changes were made after independence. India's federal system in particular has become more ethnic and more asymmetrical over time (Bhattacharya Reference Bhattacharya2010: 45–65). It reorganized the provinces on the basis of language in 1956, with the majority Hindi speakers split across a number of provinces, and then progressively created more provinces to recognize linguistic and ethnic diversity (Singh and Kukreja Reference Singh and Kukreja2014: 37–40). India has also established constitutionally protected local government (seventy-third and seventy-fourth amendments), added and extended reserved seats for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes (e.g. Article 234) and declared new official languages (e.g. ninety-second amendment).

Pakistan drastically changed its federal structure nine years after independence, by merging all the provinces in West Pakistan to create a supposed parity with East Pakistan. This system failed, and the East seceded after a short but bloody conflict. Pakistan then restored the original ethnically based provinces in the West and added the Federally and Provincially Administered Tribal Areas. It later (2010) renamed the North-West Frontier Province to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in recognition of the main ethnic group in that province and provided constitutional protection for the local government tier (Articles 32 and 140A). Pakistan has an ethnofederal system, but it is not ethnoterritorial because the largest group (Punjabi and before that Bengali) has been consolidated in one province.

The Federation of Malaya, the precursor to Malaysia, comprised 11 provinces, only one of which could be said to be ethnic (Penang). However, its expansion (and renaming) in 1963 saw it incorporate Singapore (briefly), Sabah and Sarawak, all of which have a non-Malay majority, and a plurality of one non-Malay ethnic group (Teik Reference Teik2005: 6–7, tables 5–6). The constitution also enacted asymmetrical rights in Sabah and Sarawak, for the benefit of its Indigenous Peoples (e.g. Articles 95B–E and 112A–C).

The second-generation countries have a locally focused design, with special autonomy for specific groups and areas. They are more unitary than federal in law and practice, but have federal systems nevertheless. Indonesia had a federal constitution (1949) that was never implemented and many there remain resistant to the term federalism. However, its democratic reforms of 1999 provided for a constitutional guarantee of decentralization, which was followed by the passage of special autonomy laws for Papua and Aceh.Footnote 7 The Philippines also federalized following its democratic reforms of 1987. It established a system of local government (known as provinces), with constitutional powers, and later enacted a special autonomy law for Muslim Mindanao. The constitution also includes provision for an autonomy law for the Cordillera hills (populated mostly by Indigenous Peoples). In both the Philippines and Indonesia, major islands and their corresponding ethnic groups have been divided into several provinces.

In 1987, Sri Lanka became an asymmetrical constitutionally decentralized union, following the signing of the Indo-Lanka Accord and the thirteenth amendment to the constitution. This amendment enacted, among other things, a constitutional division of powers across nine provinces and the centre. These new institutions were designed with a prominent and specific focus on the recognition of a Tamil ethnic homeland (see Jayawardene and Gandhi Reference Jayawardene and Gandhi1987: 1, Item 1.4),Footnote 8 while the dominant Sinhala group was divided across seven provinces. In 2008, Myanmar's new constitution re-established a federal system as part of its ‘managed transition’ to democracy.Footnote 9 It comprises 14 provinces (seven ‘regions’ established in Bamar majority areas, seven ‘states’ established in ethnic majority areas), six autonomous regions (self-administered areas) and (non-territorial) ‘national race affairs’ ministries for smaller ethnic groups and other second-order minorities. In Nepal, seven provinces and a local government tier were established under a new constitution in 2015. The provinces are heterogeneous though one province has a majority of a minority ethnic group and another three have a plurality of Indigenous Peoples (author's calculations based on census data). By 2020, four of the provinces had been given geographically based names by their respective legislatures, cognizant of their multi-ethnic make-up. The others are yet to be named. The constitution also provided for the establishment of autonomous regions and protected areas for smaller groups, and commissions for small and scattered minorities, such as Dalits.

Majoritarianism combined with fragmented multiparty systems

Complementing this region-wide shift to ethnofederalism in diverse countries has been a shift to mixed-majoritarianism, but without a corresponding shift towards two-party systems. The first-generation countries all have parliamentary systems and majoritarian electoral formulas. India's electoral system is FPTP, but with additional reserved seats. Pakistan started with an entirely FPTP electoral system, later (in 1973) adding reserved seats for small minorities (non-Muslims). So we would expect each to have a two-party system. Yet in India there has been a steadily increasing number of effective parliamentary parties (Jayal Reference Jayal2006: 95; Singh and Kukreja Reference Singh and Kukreja2014: 63).Footnote 10 In Pakistan, the ENPP has been greater than 3 since 1988, after initially being a two-and-a-half party system (author's calculation). Malaysia has maintained a FPTP system since independence, which has been coupled with a range of consociational practices. Seats were allocated among members of the then ruling alliance partners depending on the ethnic make-up of each constituency – for example, if it is majority Chinese, the Malaysia Chinese Association party contests the seat on behalf of the alliance. The ENPP in Malaysia, when applied to alliances, was below 2 every year except 1969, until 2018. When considering each alliance member as a distinct party, the ENPP has been above 3 for each election from 1969 on. In both cases, the overall trend has been upwards (author's calculations based on data in Nohlen et al. Reference Nohlen, Grotz and Hartmann2001 and the Election Commission of Malaysia).

The second generation of federalism is majoritarian also, but not in the same way as the first. The two outliers in Reilly's argument, Indonesia and Philippines, have a PR and MMM electoral system for their respective legislatures – but they also have a presidential system. So, stability and aggregative or moderating outcomes are (to be) facilitated through that institution, rather than by limiting party fragmentation (for example). Initially, the Philippines’ electoral system was majoritarian, with a traditional two-party system. However, in 1972 the authoritarian Marcos regime declared martial law. By the time democracy was restored in 1987–88, additional parties had been established and the ENPP jumped to average over 6, before dropping back to less than 4 in the next two elections. In 1998, the Philippines reformed its electoral system making it an MMM system with 20% proportional (party-list) and the remainder FPTP. However, contrary to the expectations and initial observations of Reilly (Reference Reilly2007) and Aurel Croissant and Philip Völkel (Reference Croissant and Völkel2012), party fragmentation has since fluctuated, between 2.5 and 6.5 (author's calculations based on data from Nohlen et al. Reference Nohlen, Grotz and Hartmann2001; Teehankee Reference Teehankee and Croissant2002; and the Republic of the Philippines Election Commission). Further, because seats in the party-list component were deemed to be able to apply to regional parties and were capped at three per party, fragmentation has been embedded, even as the party system becomes more structured (Rodan Reference Rodan2018: 116–138). Indonesia has also introduced democratic reforms, in 1999, which included a fully PR electoral system. With this system, the ENPP has continued to increase beyond the level at initial democratization, from 4.7 in 1999 (or 6.43 in 1955), reaching more than 8 by 2014 (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2018; author's calculations based on data in Nohlen et al. Reference Nohlen, Grotz and Hartmann2001).

Nepal had a unitary democracy in the 1950s and 1990s, which had majoritarian electoral systems with appointed members, though not specifically for minority groups. In each case, minorities were poorly represented, and democracy failed (Lawoti Reference Lawoti2008). Under Nepal's 2007 interim constitution, an election for a constituent assembly that doubled as a legislature was held using an MMP system, whereby out of 601 seats, 55% would be under a parallel PR component, 40% FPTP and the remainder by appointments. However, once the transition period passed, the new constitution shifted it to an MMM system, with 40% PR and 60% FPTP. These changes, which were accompanied by federalization and political party engineering, embedded the shift from a two-party system to a multiparty system.

Myanmar has not reformed its electoral system as part of its democratic transition, despite pressure to introduce PR, and it has maintained a FPTP system.Footnote 11 Myanmar has many clustered ethnic groups, a mostly unstructured party system and a democratic transition, yet the ENPP is low (at just 1.6 following the 2010 and 2015 elections). This is in large part because of the legacy of military party control. The second major party (Union Solidarity and Development Party – USDP) is aligned with the military, which itself has guaranteed representation in the organs of the state. Myanmar is semi-presidential but can be classified here as parliamentary because the president is elected by and accountable to the parliament.

Sri Lanka is also semi-presidential, but its system is more akin to a presidential than parliamentary system, because the president is directly elected (using an alternative vote formula) and is not accountable to the parliament. This is coupled with a PR for the legislature. Prior to 1978, Sri Lanka had a parliamentary system with a FPTP electoral system. The shift from FPTP to PR did not arrest the decline in the ENPP, which had been occurring since the first post-independence election, but the federalization after 1987 did. Although the 2019 presidential election has raised new priorities, a further shift in electoral systems is possible. This was foreshadowed by the MMM electoral system used for the 2018 local government elections, and the interim report of the Constitutional Assembly's Steering Committee (2017: 21), which stated that the ‘Electoral System shall be a Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system’.

These changes and features are consolidated in Table 2. It is notable that six of the eight federal democracies have either added proportional components to their previously entirely FPTP electoral systems or replaced them completely. Only two (Myanmar and Malaysia) have remained fully majoritarian and both of those have been debating a shift to PR. Figure 2 shows the trends for federalism (as per Figure 1), democracy (as per Polity5 indicator for institutionalized democracy: Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2019) and the ENPP. Most pertinent is that, although the initial increases in ENPP can be in large part attributed to democratization and the additional or PR elements to majoritarian systems, its stabilization at a high level is in large part a result of federalization.

Figure 2. Democracy, Federalism and ENPP in Eight Countries in Asia, 1948–2018

Table 2. Summary of Federal, Electoral and Party Systems in Eight Countries in Asia

Notes: a Because the president is elected by, and accountable to, the parliament. b Because the president is directly elected and accountable to the people. (GI = Gallagher Index.)

Mixed political party systems

The third key feature of the model of federal democracy in Asia is the nature of the party system, namely whether ethnic, multi-ethnic or mixed. As discussed earlier, it is assumed that party systems will be ethnic or multi-ethnic (aggregative) – not both. But in Asia, aggregative parties have been engineered, and emerged naturally, to supplement an existing ethnic party system. Further, initially aggregative party systems have been augmented by ethnic parties, without being fundamentally transformed. Ultimately, apart from Sri Lanka, all now have at least two major multi-ethnic parties and several relevant ethnic parties. This means that the fundamental assumptions underpinning both consociational and centripetal approaches to the management of ethnic division do not apply in Asia.

India is a case in point. Its political party system was not engineered or the direct outcome of the electoral system, but had its origins in the ‘Congress system’ that evolved in the pre-independence era (Kothari Reference Kothari1970: 152–223; Stepan et al. Reference Stepan, Linz and Yadav2011: 123–126). Although the Indian National Congress dominated the centre for much of India's post-colonial existence, it governed alongside a range of regional and ethnic parties in the provinces. In 1989, the Bharitaya Janata Party (BJP) emerged as the second major (multi-ethnic) party and the number and electoral performance of ethnic and regional parties increased (Jayal Reference Jayal2006: 97, Table 5.2; Singh and Kukreja Reference Singh and Kukreja2014: 64, Table 2.1).Footnote 12 Indeed, ‘[t]he BJP, even during the so-called Modi-Tsunami, could not outmanoeuvre regionalist parties’ (Schakel et al. Reference Schakel, Sharma and Swenden2019: 349). Between 2004 and 2018, regional and ethnic parties were the largest or second-largest party in no fewer than 24 of the 29 provinces (states) (Schakel et al. Reference Schakel, Sharma and Swenden2019: 342, table 3).

In Pakistan and Malaysia, the changes have worked in the opposite direction, but towards the same end. Recent developments have given rise to strong multi-ethnic parties, alongside ethnic parties. Although such a mix has existed in both Malaysia and Pakistan for some time, it has become far more prominent. The two long-standing major parties, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) have both recently promoted multinational policies, including creating a new ethnically based Seraiki province out of Punjab province (PPP: Vaishnav Reference Vaishnav2013) and the declaration of four provincial languages as national languages (PML-N). The most recent election was won by statewide multi-ethnic party Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI). The PTI has substantive support and membership from across all of the current provinces (Vaishnav Reference Vaishnav2013) and also campaigned on the bifurcation of Punjab province (Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf 2018).

Malaysia had the same basic ruling alliance in place from independence up until the 2018 election. However, there are two very important differences from India. One is that all members of that alliance are ethnic parties; the second is that the main party in the alliance (the United Malays National Organisation) did not have to rely on the support of ethnic parties to form a majority. It included them in the alliance, and allocated seats on a proportional basis, as a way of nullifying opposition, rather than incorporating multi-ethnic perspectives (Case Reference Case, He, Galligan and Inoguchi2007). There was no incentive to become a multi-ethnic party and indeed, Malaysia has been classified as an ‘electoral authoritarian regime’ (Croissant and Völkel Reference Croissant and Völkel2012: 236). The 2018 election, however, saw power change hands for the first time since independence. The two largest parties of that alliance are both multi-ethnic in both membership and policy. Even though the 2018 election was influenced by corruption allegations, the outcome is consistent with the broader shifts evident across the set of Asian federal democracies.

The second generation has, like India, been characterized by an increase in ethnic parties, alongside existing multi-ethnic parties. Initially, the Philippines system was a traditional two-party system, and each major party was multi-ethnic and secured strong support from across all regions in the country (Lande Reference Lande1967: 20–21). By the time democracy was restored in 1987–88, additional parties had been established. In particular, the Moro of Mindanao and the tribal groups in the Cordillera retain a distinct identity and religion, have sought autonomy and maintained their own political organization. There has been no attempt to limit ethnic parties or encourage aggregative parties – according to the constitution, ‘A free and open party system shall be allowed to evolve according to the free choice of the people’ (Article IX-C, Section 6 of the 1987 Constitution). Further, the party-list component of the electoral system has been interpreted by the court and election commission as being open to more than just sectoral or marginalized interests, leading to a proliferation of ethnic and regional (and dynastic) parties, especially since 2013 (Rodan Reference Rodan2018: 116–138).

Indonesia is also commonly held to have multi-ethnic or non-ethnic parties only. Political parties in the first democratic era (1950s) were based on a division between Islamic and secular parties, which to an extent carries through to today (Mujani et al. Reference Mujani, Liddle and Ambardi2018). Indonesia's democratic reforms in 1999 included a constitutional guarantee of decentralization (Articles 18, 18A, 18B) and, subsequently, organic laws for autonomy in Aceh and Papua provinces. This meant that the political party-engineering reforms discussed by Reilly (Reference Reilly2007), which required that political parties demonstrate a cross-regional presence, were excepted in Aceh and Papua and ethnic parties can now be formed in those provinces (e.g. Ch VII, Article 28 of the Law on Special Autonomy for the Province of Papua 2001).Footnote 13 Furthermore, the requirements on political parties to be national have not completely removed their ethnic affiliations. Most political parties are associated with a particular island or region, and voting patterns demonstrate continuing ethnic loyalties often associated with party leadership (Ananta et al. Reference Ananta, Arafin and Suryadinata2004). Ethnicity is commonly used as a tool of mobilization at the local and provincial levels, especially after the introduction of direct elections for local officials in 2005 (Aspinall Reference Aspinall2011; Xue Reference Xue2018).

The third generation is perhaps the most demonstrative of the trends and their effects. In Nepal, only one minority ethnic party had gained a seat in parliament up until the constituent assembly election of 2008, and the major parties were dominated by upper caste Pahadis and in effect the ethnic parties of that dominant ethnic group. These major parties pursued an identity-based nation-building agenda, within a unitary state, and although they needed the votes of minorities to hold government, they made no policy appeals in their interests (Breen Reference Breen2018a: 83–92). This exclusion was one of the major reasons for the civil war (between 1996 and 2005), and the Maoist insurgents made political inclusion a condition of the transition (Lawoti Reference Lawoti2008). To this end, political parties were required to become multi-ethnic in their representatives and policies, with great effect.Footnote 14 At the same time, the introduction of ethnoterritorial federalism meant that ethnic and regional political parties could continue to exist and be viable contestants for power at the provincial and local levels.

Myanmar also now has both multi-ethnic and ethnic parties. Although the main contest for power remains between two Bamar-dominated major parties, ethnic parties have proliferated over the past 10 years and performed well in certain provinces (e.g. in 2015, five ethnic parties won 20 of 28 seats in Shan State) and even better at the provincial-level elections, where they won more than one-third of the seats in the seven ethnic states (International Crisis Group 2015: 15–16). Further, the current governing National League for Democracy (NLD) has become more multi-ethnic. Although some of its policies are Bamar-centric, it went to the election on a commitment to establish genuine federalism, which is the agenda of the minority ethnic groups, and won a majority of seats in five of the seven ethnic states. It has established a multiparty government, with ethnic representation (albeit low) most substantially from its own members. It has appointed from within its own party ethnic speakers in both houses of parliament, an ethnic vice president, and ethnic chief ministers to six of the seven ethnic states (Lwin and Lone Reference Lwin and Lone2016).

Sri Lanka is the outlier on this feature. Relevant political parties have remained almost entirely ethnic, with minimal and tokenistic membership from minorities in the major parties and no cross-ethnic representatives in the parties of the minority ethnic groups. Minority support for them is reflective of this. In the 2015 parliamentary election, just one major party candidate won a seat in the north. Further, even though Sri Lanka took a national reconciliation approach to government formation (in 2015), with political leaders compiling a ‘good governance coalition’, the major Tamil parties did not participate (Breen Reference Breen2018a: 163–164). The most recent presidential election (2019) saw a major Sinhala party's candidate (Rajapaksa) win a majority vote by more than 10%, despite securing only around 6% of the vote in Jaffna in the north. This has put a brake on further federalization.

Social structures, cross-cutting cleavages and secession risks

So why are democratic reforms in this region converging around such a model? Although this is worthy of separate study, I identify three key reasons. First, most ethnic groups in each of the eight countries are regionally located and only a few are widely dispersed (see Wucherpfennig et al. Reference Wucherpfennig, Weidmann, Girardin, Cederman and Wimmer2011). In divided societies, people will tend to vote for candidates from their own ethnic groups because interests tend to align, and ethnic identities are often dominant and mutually exclusive (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000b: 51–61). This means that ethnic minorities are likely to get elected in seats where they are a majority, which incentivizes major political parties to appeal to those groups and to put forward candidates from that ethnic group in order to win enough seats to govern. This geographic distribution of ethnic groups works to moderate party policies and incentivize aggregative (multi-ethnic) parties when the dominant or largest ethnic group is not numerous enough on its own to ignore minority votes. However, when one group has a large population majority, it may not need ethnic minority votes regardless of the electoral system. Further, if a PR system is used in such cases, the problem is compounded, especially if the threshold is high. Minority status is embedded and, without a minority veto, PR becomes ineffectual and even counterproductive (see Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000a). Major parties can be assured of representation in minority areas under PR, without the need to moderate their policies or appeal directly to minorities.

In Sri Lanka, for example, Sinhala people comprise around 75% of the population, and so minority votes are not always required to form government. Its 1978 shift to PR (from FPTP) made virtually no difference to the ENPP or ethnic proportionality, because communities are clustered. It is no surprise that Sri Lanka is the only one of the cases that still has an entirely ethnic party system. If Myanmar, for example, had changed from a FPTP to a PR system, ethnic parties would have won only three extra seats (out of 330) at the 2015 election (author's calculations based on regional voting data).Footnote 15 The most successful ethnic parties would have lost 25–50% of their seats. The military-aligned USDP would have benefited most.

It has been observed elsewhere that cross-cutting cleavages may, in certain conditions, make conflict less likely (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000b; Selway Reference Selway2011). The presence of strong cross-cutting cleavages leads to multi-ethnic parties, and multi-ethnic parties moderate conflict. According to Joel Selway (Reference Selway2011), Sri Lanka and Malaysia have the least ‘cross-cuttingness’.Footnote 16 Sri Lanka still has an ethnic party system, Malaysia did until very recently. An absence of cross-cuttingness is particularly significant on an ethnic and religion dimension (Selway Reference Selway2011). Notwithstanding the substantial risks associated with the rise of Hindu nationalism in India,Footnote 17 the fact that religion cross-cuts ethnicity was conducive to the institutionalization of multi-ethnic parties and federalism. Table 3 consolidates basic demographic data on each case.

Table 3. Basic Demographic Data for Eight Countries in Asia

Sources: Ethnic proportion from Central Intelligence Agency (2013); cross-cuttingness from Selway (Reference Selway2011); clustering from Wucherpfennig et al. (Reference Wucherpfennig, Weidmann, Girardin, Cederman and Wimmer2011).

Notes: a Proportion of major ethnic groups that are regionally based (mostly clustered), rather than dispersed, urban (only) or statewide. b Uses linguistic groups.

Finally, all of the cases are instances of holding-together federalism.Footnote 18 In a post-conflict democratization or settlement negotiation, the secession risk and its ethnic dimension are paramount. Hence there are minority ethnic leaders and sometimes armed groups at the table, and federalism is a compromise (Breen Reference Breen2018b). Ethnoterritorial provincial designs are a compromise between aspirations for ethnic autonomy and central priorities for unity and stability, while strong local government acts as a counterweight to provincial secessionist movements (Breen Reference Breen2018a: 153–158). Unlike Reilly's cases, the aim is not to prevent new entrants but to accommodate new entrants as a means of resolving conflict and mitigating secession risks. The outright banning of ethnic parties is rarely an option because it forces ethnic actors to again resort to arms to defend their interests. But dominant parties will tend to advocate for majoritarian systems and minority groups for PR (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000a: 270–271). The more relevant political actors there are, the more likely it is that a PR system will be adopted (e.g. Ufen Reference Ufen2008: 344). Mixed majoritarian systems are a compromise related to both the power dynamics of a constitutional settlement or other reform process, and objectives of (minority) inclusion and stability.

The implications of the federal model

The federal model of electoral democracy in Asia has important theoretical ramifications. One concerns the relationship between party fragmentation, federalization and democratization, or more specifically party institutionalization. According to theory, the ENPP is meant to decline as democratization proceeds. But in these cases, federalization has kept it high. This point reinforces and adds to the conclusions of Allen Hicken and Erik Kuhonta (Reference Hicken, Kuhonta, Hicken and Kuhonta2015), who find that in Asia, party system institutionalization does not follow democratization. Further, I find no meaningful correlation between the ENPP and electoral volatility, which is a measure of party institutionalization (based on volatility data from Hicken and Kuhonta Reference Hicken, Kuhonta, Hicken and Kuhonta2015). In other words, irrespective of how institutionalized the party system is, the ENPP remains high because of the federalization and its mixed party systems.

Second is the effect of majoritarianism on the ENPP and the stability and formation of government. The institutionalization of a majoritarian democracy is traditionally understood to tend towards: the development of a two-party system (and more stable governments); low party proportionality; and low levels of political inclusion for minority ethnic groups. This is why scholars such as Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1977, Reference Lijphart1999) recommend PR systems for ethnically divided countries. But in these cases, majoritarian electoral systems have resulted in multiparty systems with coalition governments now the standard, even in cases where one party has a majority of seats. This has been observed by others in relation to India (e.g. Jayal Reference Jayal2006: 100–101; Stepan et al. Reference Stepan, Linz and Yadav2011), but is in fact a region-wide phenomenon. Indeed, all of the eight federal systems have in place a coalition government at the time of writing and very few parties have won a majority of seats in their own right. Yet even when they did (NLD in Myanmar, BJP in India), they have included other parties in their cabinets.

These coalition governments have, so far, proven more democratically stable than the single-party governments of the past.Footnote 19 With few exceptions, each major episode of de-democratization or onset of large-scale conflict occurred at a time of single-party government (executive) (author's calculations). The exceptions are Myanmar, where conflict started at independence and in 1962 when the government was a coalition but a minimal one, Pakistan in 1958 when the cabinet was more than one party yet still minimal and Indonesia in 1960 when the cabinet was oversized. Otherwise a single-party minimal cabinet immediately preceded de-democratization and the onset of major conflicts in India, Indonesia, Nepal (twice), Philippines, Pakistan (twice) and Sri Lanka. Indonesia is the only instance of an oversized cabinet preceding de-democratization.

There is greater stability because there is more democratic space. Most, if not all, groups have opportunities to compete for (democratic) power and so do not resort (as easily) to arms. The model does not mandate formally or by design the representation of all groups all the time, as per consociationalism, which in itself limits democratic competition because parties tend to compete within groups. This also overcomes deadlock associated with veto rights and reduces the risk of such structures resulting in autocratic ethnic parties (see Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000a). There is competition both within and across ethnic blocs. Governments themselves tend to be more stable because of the majoritarianism that lowers the threshold for forming and maintaining coalition government. But diversity and mixed elements mean it is rare for one party to breach that threshold by itself, necessitating a more inclusive executive. It avoids the major pitfalls of centripetalism because it provides for ethnic autonomy and is, for that reason, more agreeable to ethnic groups in conflict. It is ethnically inclusive and does not simply re-create or enable patterns of domination to continue.

Thus, the model is neither consociational or centripetal – it is a hybrid that combines elements of both (see Table 1), and the elements work together, rather than contradict or undermine one another. Ethnofederalism, strong local government and special structures provide space for ethnic political parties to compete alongside multi-ethnic parties, which incentivizes the multi-ethnic parties to become more proportional and to establish voluntary coalition governments that include smaller ethnic and regional parties (see also Breen Reference Breen2018a: 158–166). This creates cycling majorities in the centre and in the periphery embedding inter- and intra-ethnic competition, and prevents the capture of state institutions by one group or party. In this way it accommodates ethnic difference through autonomy and inclusion and it incentivizes cross-ethnic deliberation and moderation. But there are no veto rights or grand coalitions, and the use of an alternative vote or vote pooling is rare.Footnote 20 If the objective of federalization in these cases is to hold together, then they have been successful and found a workable balance between minority ethnic aspirations and goals for national unity.

Conclusion

The federal and democratic reforms in divided societies in Asia have exemplified a new yet still evolving model of federal democracy in Asia which can be compared and contrasted with a unitary model. This unitary model, described by Reilly (Reference Reilly2007), comprises MMM electoral systems and political party engineering that encourages aggregative parties and restricts ethnic and regional parties. Like the unitary states, federal countries in Asia have mixed majoritarianism on account of the electoral system or presidential system. However, although majoritarian systems are prevalent, the general trend has been towards increasing the extent of proportionality in the electoral system to try and find some balance between inclusion and stability.

Further, the federal model is characterized by the very trend towards further federalization. All eight cases have become ‘more federal’ since independence, and have increased the ethnic components of their federalism, by adding new ethnically based provinces, establishing special autonomy or designing the entire system with ethnicity in mind. They have also added special structures for small and scattered minorities, such as ‘national race affairs’ ministries, personal law systems, non-territorial commissions and small autonomous regions, and many are asymmetrical. A majority also have constitutionally protected local government, which provides more targeted ethnic autonomy and acts as a counterweight to the secessionist ambitions of the larger provinces. All of them, except for Pakistan, have ethnoterritorial federalism, where the dominant group is split across a number of provinces, with one or more smaller ethnic groups having dedicated province(s). Pakistan's Punjabi population is mostly consolidated into one dominant province.

Thirdly, the federal model differs from the unitary model in that it allows, indeed encourages, both aggregative (multi-ethnic) and regional (ethnic) political parties. Where (minority) ethnic parties did not exist, federalization and electoral system reforms have created the space and incentive for their creation. Where multi-ethnic parties did not exist, democratic reform and political party engineering have incentivized or mandated their creation, or the transformation of the ethnic parties of the dominant group(s). This combination appears to have had a more positive impact on the extent of ethnic proportionality in legislatures and executives than proportional electoral systems, obviating the need for specific consociational tools such as grand coalition or reservations (other than in the case of small and scattered minorities). Certainly, this has been the case in the emerging federations of Nepal and Myanmar. This should be the subject of future research.

The model is not consociational or centripetal. Those theories do not fit well with the situation in Asia, because they assume only ethnic parties, or a single alliance or party, are relevant in deeply divided democracies. In practice there is much overlap between consociational and centripetal models (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2019; Reilly Reference Reilly2012) and, indeed, this federal model is characteristic of several combinations of majoritarian and consensus-based institutions (see Table 1).Footnote 21 However, their features cannot be simply mixed without regard to their interaction as it may result in the kind of incoherence that Horowitz (Reference Horowitz2000a) warns against. They can be ‘friends or foes’ (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2019). In Asia, federalism and the social structures allow elements of each approach to coexist in a complementary way. Ethnic autonomy is enabled through federal provincial design, strong local government and special structures. This is combined with a majoritarianism that incentivizes more moderate multi-ethnic parties and voluntary coalition governments, while ensuring a strong centre. This vertical hybridity leads to multiparty systems, high levels of ethnic proportionality and democratic stability.

The model is a result of the holding-together federalization process, a response to a secession risk or the broader break-up of the state. Like the cases covered by Reilly, the parties and political actors are motivated by an aim to increase government stability, but instead of aiming to reduce fragmentation and block new entrants, they have little alternative but to accommodate new entrants – and increase autonomy – as one way to mitigate secession risk and resolve conflict. The model thus achieves objectives of both stability and ethnic accommodation. It offers a coherent middle way between consociationalism and centripetalism because of the complementarity of majoritarianism and segmented autonomy when ethnic groups are clustered and with cross-cutting cleavages.

Whether the model can deliver longer-term success and sustain stable democracies and conflict regulation should be the subject of further research. For one, most of the countries still have a considerable democratic deficit – Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Myanmar and Pakistan in particular. Certain conditions make such outcomes more or less likely. For example, the ability of one province to dominate has been identified by Henry Hale (Reference Hale2004) as a source of instability, and this condition exists in Pakistan (Adeney Reference Adeney2009). Multi-ethnic parties have not emerged in Sri Lanka and are fledgling in Myanmar. Both of these countries have a relative demographic disadvantage as one ethnic group comprises more than two-thirds of the population. Malaysia also has a near majority of one ethnic group. In such cases, a more deliberate effort at engineering the party system, such as has occurred in Nepal, may be warranted. In India, the large majority secured by the BJP in the 2019 election has allowed it to mostly forsake coalition partners, push a Hindu nationalist agenda and undermine certain federal features. Furthermore, there are other problems in the region's party systems that this article does not consider – for example, the dynastic nature of parties in the Philippines, or clientelism in Indonesia.

Nevertheless, federal failures, like the collapse of democracy in Pakistan and Myanmar (then Burma) and the electoral authoritarianism in Malaysia and Indonesia, have all been associated with either the absence of an ethnoterritorial federal system, or the absence of a mixed party system with at least two multi-ethnic parties. The strength of federal provinces provides a buffer against democratic decay in India, and populism more generally. Further, while several countries in Asia have seen their democracies go backwards over the last 10 years (e.g. Thailand, Bangladesh, Cambodia), the eight ‘federal democracies’ have over the same period maintained or enhanced their electoral democracies, as measured by the Polity5 Project (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2019). The model has a track record across the region, and though we should expect it to continue to evolve, as it must to meet changing conditions and current and arising challenges, the basic elements of an alternative middle way for accommodating ethnic diversity while maintaining national unity are in place in ethnically diverse democracies in Asia.

Supplementary material

To see the supplementary material for this article, please go to https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.26.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to Brian Galligan (1945–2019). I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the many people who provided valuable feedback at presentations of this research, in particular Benjamin Reilly, Baogang He, Wilfried Swenden, Jon Fraenkel, Soeren Keil and Timofey Agarin. I also acknowledge funding from the University of Melbourne, grant no. 502581.