Introduction

The expression “dead White men” has become hackneyed in decolonial conversations. It is a given that there is a pressing need to diversify academia: this obligation involves questioning, dismantling, and reconstructing canons in their most old-fashioned forms on the one hand, while gravitating toward practices that promote a more equitable redistribution (if not diffusion) of power on the other hand. These actions are required all over the world, not least in Africa, where colonialism was experienced in some of its worst forms. And yet, even in the twenty-first century, the phrase “dead White men” takes on a visually and conceptually poignant pertinence at the Department of English in the University of Ghana, Legon.

Prominent on the walls of this two-floor department are thirty-seven portraits of poets, writers, and playwrights – as well as Queen Elizabeth I (see Figure 11.1). Of this number, only five – Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Ama Ata Aidoo, Ousmane Sembène, Kofi Reference AnyidohoAnyidoho, and Kofi Awoonor – are of African descent (see Figure 11.2). Perhaps equally striking is the fact that out of the total, Aidoo is the only other woman author apart from Jane Austen. The remaining twenty-nine personalities are British and American White male literary artists, including well-known giants such as Shakespeare, Milton, and Conrad and others such as Thomas Wyatt the Elder, Aldous Huxley, Henry Howard, and Joseph Addison; none of the latter group, among other authors hanging on the walls, has featured in either undergraduate- or graduate-level syllabi or faculty-level research for decades. In other words, this visual greeting to students, staff, and visitors at the department is overwhelmingly by dead and somewhat obscure White men who, what is more, have little bearing on their immediate audience.

Figure 11.1 Portraits of dead White men, Jane Austen, and Queen Elizabeth I at the Department of English, University of Ghana.

Figure 11.2 Portraits of Ama Ata Aidoo and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o at the Department of English, University of Ghana.

This means that after more than seven decades of existence, a founding department of the oldest university in the first African country south of the Sahara to gain political independence from Western colonialism grapples with a situation that presents a twofold challenge to educators: first, many of those writers being held up as the standard have direct ties to colonial and neocolonial cultures whose presence looms over local/African output.1 Secondly, the prominent presence of these personalities is sharply belied by their remoteness in terms of cultural and academic relevance.2 In addition to the familiar nationally embraced social, economic, and political challenges that are presented by the colonial accident and filter into African universities, it is within this paradoxical context that the department functions.

And even if this situation at Legon is not visualized as dramatically at other African universities, the curricula of English and Literature departments in many institutions across the continent are similarly encumbered by obstacles that demand the addressing of pedagogical structures to decolonial ends. A casual sampling of syllabi in African literature courses from other universities in Ghana as well as universities in Senegal, the Gambia, Nigeria, South Africa, Cameroon, Malawi, and Botswana reveals methods of teaching and textual choices that are steeped in conservative modes and gravitate toward conservative tendencies.3 For example, courses privilege written texts (over oral and digital texts), while the traditional classroom space continues to be idealized as the sole learning environment. A more carefully done formal survey by Bhakti Reference ShringarpureShringarpure corroborated this situation but also found that other African universities, especially in Kenya and Uganda, allow students to “gain a deep knowledge of African literary traditions with emphasis placed on orature and orality.”4 In other words, different universities adopt practices that have varying degrees of success in being decolonial in nature and application.

This chapter is not intended to unduly criticize universities in Africa, which have collectively made impressive strides despite astonishing difficulties. Apart from unacceptably high student–teacher ratios for instance, finance is a big challenge: access to local funding for African universities remains chronically low, while a handful of Africa-based researchers occasionally win grants usually from foreign sources.5 Even worse, political interference occurs in many institutions. In Ghana, for example, there were multiple government-sponsored attacks and attempts to destabilize universities and university systems between 2017 and 2020.6 More specifically to literature, it must not be forgotten that hardly anyone researched into or taught African literature up until the middle of the twentieth century (Reference LindforsLindfors vii). In fact, Tejumola Olaniyan and Ato Quayson’s African Literature: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory, which is the first ever critical anthology to focus exclusively on African literature, came as late as Reference Olaniyan and Quayson2007.7 The progress that has been made despite these challenges can still be extended by suggestions that are informed by my experience gained from teaching an English course at the University of Ghana.

I use ENGL 314: Introduction to African Literature, taught in three different semesters (between 2020 and 2022), to highlight decolonial pedagogical techniques that ultimately tackle two concerns. The first is this most classic of questions that can be traced to the colonial encounter: how does one find a “balance” between the imposition of “untouchable” and “Western” standards in the literary canon and African creative expression in a postcolonial country such as Ghana? Secondly, in an age where the humanities faces various crises, including questions of finance and relevance, how is the significance of literature to aspects of students’ life, including the political, sociocultural, and ethical, to be highlighted by relevant pedagogical strategies? These questions are contextualized within a brief history of the university as well as in the evolution of the department.

Legon: The History of an African University

According to its website, the University of Ghana “was founded as the University College of the Gold Coast by Ordinance on August 11, 1948, for the purpose of providing and promoting university education, learning and research.”8 What is missing from this condensed history is that the university was set up after sustained agitation from different colonized subjects, including farmers and the educated elite, who demanded the establishment of a tertiary institution in the Gold Coast territory. Obviously there existed (and continue to exist) African forms of education (typically called “informal education”) (Reference Adeyemi and AdeyinkaAdeyemi and Adeyinka 425). Still, the establishment of the University of Ghana marked the beginning of Western-style tertiary education in the Gold Coast, which had ended at the secondary-school level prior to these developments. Money from cocoa farmers formed the bulk of funds that were used to set up the University College of the Gold Coast.

The colonial administration modeled this new institution on the University of London, thus giving the institution a British identity from the beginning.9 Francis Agbodeka notes that documents call this association a “special relationship” (Reference Agbodeka18), but for all intents and purposes, the new university was under the tutelage of its British counterpart, which exercised absolute control: the University of London approved courses, had a major hand in recruiting staff through an interuniversities committee in London, and had to approve syllabi and reading lists prepared by faculty at Legon. Additionally, examination questions were sent to the British counterpart for approval, while Legon faculty regularly traveled to London for examiners’ meetings. The university was purely European in idea and practice – explained further by the fact that the first staff recruits were Europeans who were trained in European universities. They brought with them wholesale what they had learnt from Europe, with little to no African input. The curriculum therefore remained exclusively Eurocentric from the beginning.

To the credit of the European staff, there was a coordinated movement to Africanize courses, especially after Ghana gained independence in 1957. Resident faculty, including Polly Hill, Ivor Wilks, and E. F. Collins, started to produce research that was relevant to their immediate environments; they then brought their work to the classroom. Hill, for example, explored the migratory and capitalist practices of cocoa farmers, while Wilks researched the history of the Asante kingdom.10 This Africanization push was supplemented by a decision in 1953 to increase the recruitment of qualified Ghanaians, as the university began a staff development program which involved identifying promising students and awarding them scholarships to pursue graduate studies. Beneficiaries of this policy included Alexander Adum Kwapong (who later became the first Ghanaian vice chancellor of the university), while J. H. Nketia had joined the university as a research fellow in Traditional Music, Folklore, and Festivals in West Africa in 1952. Most of these graduates traveled to universities in the United Kingdom, although a few went to the United States.

While undertaking their graduate studies, this first group of Ghanaian graduates typically wrote dissertations that focused on Western research. However, as their numbers started to increase, newer cohorts, including scholars such as George Benneh, John K. Fynn, L. A. Boadi, Florence Dolphyne, and G. K. Nukunya, invariably produced doctoral theses on African studies topics while abroad.11 They started returning to Legon from the early 1960s and, because they had Africanist backgrounds, establishing African courses was relatively straightforward. Accordingly, through new syllabi and reading lists, disciplines such as Music, History, Anthropology (which increasingly adopted a Sociology character), Linguistics, Geography, Archeology, and Philosophy started to assume identities that moved further away from their exclusively Eurocentric origins. An even stronger effort at Africanization commenced with Nkrumah’s establishment of the Institute of African Studies in 1961, and scholars further Africanized the curriculum at the pretertiary level by writing textbooks on African Studies subjects.12 With these efforts, high-school graduates who entered university had a fairly decent background in terms of formally taught African content.

In the midst of this transformation, English lagged in embracing Africanization, mainly due to the faculty’s lack of belief in the quality of African writers (Reference AnyidohoAnyidoho 9).13 Influenced by his Nigerian colleague Ikide, faculty member K. E. Senanu introduced the department’s first course on African literature in the 1970s, which was open only to English majors in their final year; all other courses remained a spillover from the colonial period.14 Disagreements between Sey and Senanu over introducing new African-centered courses at the department led to the departure of the latter to Kenya in the 1970s. Senanu had earlier played a crucial role in attempting to dismantle conservative structures at the department after spending a sabbatical at the University of Ibadan, which was set up in the same year as Legon. Ibadan at the time was a site for radical decolonial efforts, with scholars such as Biodun Jeyifo spearheading the charge.15 Added to the famous efforts of Ngũgĩ in Kenya (reflected in his seminal essay “On the Abolition of the English Department”) and others across the continent, African scholars had been bringing progressive developments to English departments in Africa. In East Africa, the name “English” was replaced by Literature or its equivalents, signaling an ideological shift. This was not reflected at Legon’s English Department anywhere as intensely.

The Africanization of the Department of English also lagged in terms of research at both faculty and student levels. In an interview, Reference AnyidohoKofi Anyidoho, who was an undergraduate student in the 1970s and a former head of department from 2004 to 2006, recalls being forced to move to the Linguistics department to write a long essay on oral literature because department faculty strongly discouraged his decision to do so at the English Department.16 Needless to say, the change at the department was gradual. Up until the 1970s, there was still a substantial number of British faculty at the department and at the university as a whole.17 However, in the late 1970s, the British government withdrew the British University Grants Committee (UGC) subsidies for lecturers overseas, which had been set up in 1919 and was crucial to them staying.18 This withdrawal led to an exodus of British lecturers from Ghana, clearing the way for more African faculty.19 By the time the university survived the economic crisis that plagued Ghana in the early 1980s, there was a majority African presence in terms of staff, which has remained the case until today.20

Still, as late as 1986, Reference LindforsBernth Lindfors had surveyed 194 courses from thirty universities in fourteen African countries, finding that while the “most radical reorientations” in the curriculum had occurred in Kenyan and Tanzanian universities, the “staunchest conservatism” was the case at the English Departments at the University of Ghana and the neighboring University of Cape Coast, both of which had only affected “minor alterations of the old colonial curriculum” (Reference Lindfors48). The department’s history of being slow to embrace decolonial endeavors has meant that it has taken monumental efforts to chip away at its conservative nature.

Shifts in curriculum development in the 1990s led by such faculty as Reference AnyidohoAnyidoho, Awoonor, Dako, and Mensah helped the English department make significant strides at decolonial efforts. By the turn of the millennium, and under the tenure of Reference AnyidohoAnyidoho as head of department, the first two doctoral dissertations in African oral literature were passed in the department, with an increase in numbers since then.21 In the last two decades, more African-centered courses have been introduced to the department at both undergraduate and graduate levels, including Oral Literature, Ghanaian Literature, Postcolonial Literature, and Literature of the Black Diaspora, all of which expanded the curriculum to decolonial ends. These courses, like most other literature courses at African universities, privilege written text and do not typically require students to go outside the classroom. Grappling with these legacies, I argue the need to do more than just revising the text of the curriculum, by introducing new modes of pedagogical engagement that foreground relevance while utilizing the resources immediately available. In times when African Studies must evolve, it is important especially for African universities to utilize Indigenous forms of knowledge and reconceptualize the environment to benefit students and optimize pedagogical potential.22

Orality and Experiential Learning at Legon

The following section expands upon this proposal to recollect and subsequently reflect on the treatment of the ENGL 314: Introduction to African Literature course at the University of Ghana, taught during the second semesters of the 2019/2020, 2020/21, and 2021/22 academic years. This course is required for all third-year students of English and has been taught in different forms for at least forty years. During the scope of study for this chapter, the class size has ranged from 75 to 110, including foreign students in all iterations apart from the last one (due to a nationwide university strike among faculty that shifted the calendar). The class size is one of the limitations that will be discussed later in the chapter, even though it is important to note here that the different semesters had a similar syllabus. Historically, the course is usually taught neither with recourse to optimal usage of the physical environment nor by harnessing nonwritten texts in a central manner.23 A marked departure from previous offerings of the course thus involved implementing an interplay of oral and experiential learning strategies, away from centering a syllabus around conventional understandings of text and writing that in turn privilege Eurocentric offerings.24

What Karin Barber terms as investigating “the very constitution of the text itself” (Reference Barber67) helped to further understand what a text is. Barber further states “what a text is considered to be, how it is considered to have meaning, varies from one culture to another. We need to ask what kinds of interpretation texts are set up to expect, and how they are considered to enter the lives of those who produce, receive and transmit them” (67). Varied interpretations of text are not intended to create a hierarchy that privileges some interpretations over others; the intention is to place them on a horizontal scale from which to make relevant choices. Additionally, the fact that one culture accepts certain interpretations does not prevent that culture from adopting and accepting alternatives from other cultures. In a globalized world where cultures have always borrowed and lent themselves despite tension and appropriation, cross-cultural exchange allows an instructor to pick and choose from a wide selection. Following from Barber, then, it is important to underline that for this course, text and writing were thus seen as both embodied and geographical due to the relationship that exists in African literature between orality and creative expression.

On all three occasions, the first few class sessions involved helping students unlearn the regular understanding of texts and writing as absolute in Western/colonial terms. The students subsequently imbibed the concept of decentering these meanings to incorporate forms that they had not immediately considered as acceptable texts.25 As Uzoma Esonwanne explains, treating oral discourses as literary devices does not trigger repetition; it rather causes the former to be spoken in a new context that creates a non-pre-discursively new utterance (Reference Esonwanne and Quayson142).26 By deconstructing orality and text, the intention was to put pressure on their elasticity, thereby allowing students to rethink their natural environment as a text that was ripe for intellectual engagement. They were able to then understand their lived experiences in Accra as a series of learning moments.

In a time when African cities are increasingly the focus of mainstream research, it is incumbent upon teachers to utilize their environments for pedagogical purposes.27 The basic logic underpinning this move was that if learning about African literature was taking place at an African university, then it was important to engage with the host African city in productively relevant ways. Accra (and by extension both Ghana and Africa) is written and spoken simultaneously – addressing only the former side of this equation through conventional learning practices leads to an incomplete understanding of the city.

One way of approaching a fuller understanding of the city was to introduce a research assignment that involved investigating the makeup of Accra through oral histories. Oral histories are the major source of both official and unofficial knowledge, and on a continent with a relative dearth in written research, oral information is a crucial source. Again, a significant amount of research on places in Africa is done through Eurocentric framings. For example, foundational texts in African studies are Eurocentric in authorship and origin, as European missionaries, soldiers, administrators, and other scholars wrote about the continent in various disciplines. V. Y. Reference MudimbeMudimbe argues in his seminal The Invention of Africa that “Africa” is a constructed culmination of centuries of discourses and practices – largely starting from the fourteenth century by Europeans and responded to from the nineteenth century by Africans. In their attempts to question this invention, African scholars have not escaped the Eurocentric invention of Africa. Even though African studies aims at reclaiming the voice that was taken away from African subjects, there has been a tendency to maintain the West as the subject of history.28 In contemporary times, Akosua Adomako Ampofo points out how Western scholarly outlets are prized, influencing African researchers to gravitate toward such destinations (Reference Ampofo17). Even though (or maybe because) the students in the ENGL 314 class do not have formally extensive training in research methods, it was important for them to appreciate that oral sources are as legitimate as published articles and monographs.29

Different student groups were to choose suburbs in Accra from a list and were tasked with investigating the history of the origin of the place. They were to accomplish this assignment by identifying and speaking to people who would have knowledge of its history. They were at liberty to complement this research by looking for documented evidence, even though this was to be a secondary strategy. After minimal training – involving introduction and observational skills – the students were to create a set of questions that would serve as a springboard for finding out the needed information. The purpose of this exercise was to let the students realize the consequence of considering people as recognized sources of information. Oral sources of information on the same issue are notorious for differing in terms of accounts; this feature was to help the students to think through authoritative sources while looking out for inconsistencies in competing accounts. In cases where histories of places were readily available – such as Jamestown and Labone – the information obtained was sometimes different from what was documented and available in libraries and archives, again allowing for an understanding of contested sources.30

By approaching and interviewing people about the histories of different places in Accra, the students were again able to define knowledge as embodied in the people they spoke to.31 Often, students would find that older people were walking history libraries who had an admirable understanding of how the place in question had evolved. Additionally, knowledge was circumscribed by specific places in the suburbs they were to investigate. For instance, churches and mosques were usually the places where students found origin stories of the various suburbs. In subsequent discussions, students appreciated the fact that people, articles, and books could be placed on the same scale of credibility on the one hand; on the other hand, different people and different written sources could compete among each other for authenticity and authority. The tendency to not have a single authoritative source allowed for a questioning of what it means to diffuse authority and “truth” in a spectral sense. Learning through this experiential model of quasi-ethnographic research was therefore useful.

It is important to harness the creative and scholarly engagements with these cities through experiential learning to make the classroom space relevant to African students. Universities in Abuja or Abijan, or Khartoum or Kigali, for instance, can adapt this assignment to appreciate the importance of understanding the rapidly changing nature of their cities. Instead of drawing a dichotomy between the classroom and the street (Reference QuaysonQuayson, “Kóbóló Poetics” 428), the classroom becomes the street, and the street is the classroom, as students are constantly alert to finding out how to learn from their physical environment.

Another decolonial strategy involves provoking a sustained critique of conventional teaching modes by displacing agency to students, allowing for the interrogation of assumptions that underpin their lived experiences. This strategy was meant to avoid replicating colonialism in the classroom in the scenario where the instructor wielded undue levels of power. The course facilitator, namely the professor, is in the prime position to exercise judgment in shaping the course and content of research and study. We must also trust students with the ability to be responsible sharers of this power. This point for me was important because anecdotal experiences corroborate research that indicates that students do not feel empowered in the classroom.32 Youth agency has to be amplified on a continent where more than two out of every three Africans south of the Sahara are younger than thirty years of age.33

Thematizing a Class

All three iterations of the course were themed around sound. This was done upon consultations with experienced faculty both in and outside the University of Ghana.34 There was additional theoretical grounding in sound studies, with Jonathan Sterne, Igor Reyner, Gavin Steingo and Jim Sykes, and Marleen de Witte particularly helpful.35 As mentioned in the course description of the syllabi, African literature is loud and full of sound: modern African literature such as novels and plays on the one hand, and African digital literature on the other hand, consistently emphasize noise, dialogue, and music. Written African literary texts such as Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Ayi Kwei Armah’s Fragments, Noviolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names, and Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s Tram83 are full of both sounds and music. And Wole Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman is famous for being structured around various forms of drumming in all parts of the play, even in scenes involving only the White characters. Oral literature is full of singing, dancing, and performance, while the acoustics and beats of contemporary music genres allow sound to permeate through creative expression all across the continent. The course was intended to introduce students to the uniqueness of African literature through a focus on sound in various ways: mythically, textually, politically, socially, culturally, and symbolically. Outside of the surrounding environment of Accra, the choice of conventional text and writing was therefore premised on understanding how to engage with sound centrally, tangentially, and indirectly.

As mentioned above (p. 000), even though the definition of text was elastic, there were still novels, plays, and short stories. Out of the selected texts, about half were authored by women, while there was a healthy mix of canonical authors such as Achebe and Aidoo, relatively newer well-known writers including Adichie and Bulawayo, and amateur writers from websites such as Brittle Paper and Flash Fiction Ghana. Writers came from countries that included Ghana, Nigeria, Algeria, Congo DR, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The intention was for students to not expect a monolithic demographic with its attendant narrow implications for perspective formation and viewpoint shaping. Spreading the author choice around these various parameters was an obvious attempt to cover an appreciable amount, even if it must be immediately admitted that, as with any set of choices, many important aspects would be inevitably left out. It would be unconscionable to many lovers of African literature, for instance, that only three of the top five most-mentioned African writers featured on the syllabus.36

The Pandemic as Opportunity

In the first two times that the course was taught, the COVID-19 pandemic altered the mode of teaching. The pandemic first reached Ghana during the middle of the semester (March 2020), with attendant implications for the mode of delivery and experiential learning. In a country that has not kept up with digital advancements, there was a general difficulty in adapting to online teaching. Subsequent teaching of the course was informed by less face time and more virtual interaction. Considering the high cost of data to the average student and the lack of digital infrastructure in some places, this challenge hampered the pedagogical effectiveness of courses all over the country and continent.

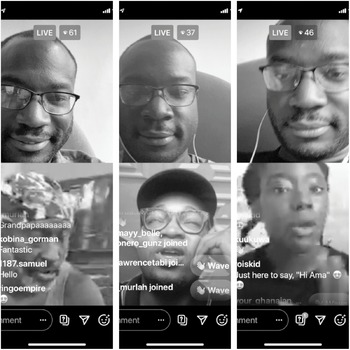

COVID-19 still provided a ripe opportunity for digital technology to be an integral part of the class. There had been plans to invite creative artists to class to interact with students and do performances/readings of their work. Because of a lockdown in Accra and general social-distancing guidelines, students interacted with musicians, poets, and spoken word artists via Zoom calls and Instagram Live sessions. Through networking, I was able to have my students partake in interactive sessions with the hiplife musicians Reggie Rockstone and Kojo Cue, the poet Agyei Adjei Baah, and the spoken word artist Poetra Asantewa, mainly via Instagram (see Figure 11.3). African literature classes will benefit from finding ways of interacting with creative artists who are local to whichever space that the institution is located.

Figure 11.3 Screenshots of Instagram Live sessions with Reggie Rockstone, Kojo Cue, and Poetra Asantewa, respectively, in 2020.

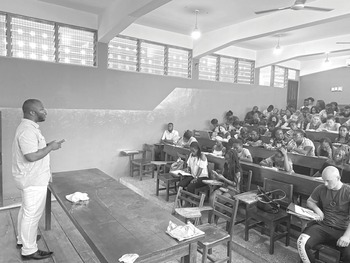

Creative artists are busy people, and securing their time was not always a success. During the second running of the course, no artist was able to make the time to join the class. This absence was also due to a shortened semester, the circumstances of which are explained in the conclusion of this chapter. For the third iteration, students had the pleasure of talking to the Ghanaian musicians Worlasi and Jupitar (see Figure 11.4), who physically came to class and fielded questions regarding inspiration, theme, character development, and other literary aspects of their songs. The amateur writer Fui Can-Tamakloe also visited the class on all three occasions (see Figure 11.5). His Pidgin-English stories, which appear on online portals, were intended to open the students’ minds to the possibility of seeing Pidgin-English appear in mainstream spaces.37 Listening to practitioners speak about their craft in nonscholarly ways was intended to complement class discussion and remind students of multifaceted engagements with texts.

Figure 11.4 Respective class visits by the Ghanaian musicians Worlasi and Jupitar in 2022.

Figure 11.5 Guest appearance from the Pidgin-English writer Fui Can-Tamakloe in 2020.

While guest visits by practitioners are by no means a novel mode of pedagogy in African universities, having them interact with students is another way of fulfilling the call by Ato Quayson and Tejumola Olaniyan to ensure that African literary and critical production are not discrete entities but relate in a “supportive and critical, mutually affective intimacy” (Reference Olaniyan and Quayson1). The students on the one hand related up close with them; the creatives on the other hand saw their work through the eyes of their audiences in ways that made them rethink aspects of their work such as thematic and character development.

Conclusion: Limitations and Shortcomings

Apart from the litany of challenges that hamper teaching in a university in a postcolonial country such as Ghana, a new mode of pedagogical engagement that relied on learning on the go while dealing with unforeseen problems like COVID-19 would inevitably yield a series of omissions, mistakes, and limitations. Each iteration of the course had a set of unique and overlapping hurdles to cross: the first time was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic; the second time was limited by a compression of the semester due to logistical challenges that the university faced in trying to catch up after closing down for months – the semester was done exclusively online, with twice the number of classes per week in half the total semester time; the third iteration of the course witnessed a reversion to the regular semester, even though the period was also compressed into ten weeks instead of thirteen, due to the strike and aftereffects of the pandemic. Even after the university eventually manages to return to a regular schedule, the other challenges (class size, finances, etc.) will most likely remain.

In terms of the breadth of syllabus, the truth of the matter is that the beauty and force of African literature is too diverse to be captured in an undergraduate class that allows for ten to twelve weeks of teaching. Different authors, themes, and texts will inevitably be left out, while the intention to foreground student agency by allowing their perspectives to influence class discussion and direction also means that occasionally, lesson plans that intend to cover certain concerns might not always be fully realized. Focusing on the various realizations and utilizations of sound was one window through which to approach the texts; alternative approaches can appropriate place and space, the home, queerness, social relations, power dynamics, and the public sphere, to name a few. In other words, like many thematized classes in different disciplines, African literature courses are open to a multitude of angles from which an instructor can take the class. The choice of theme can inform the text selection, even though, as always, certain texts will always be left out.

There were other limitations. The architectural shortcomings of the classroom venue prevented the adoption of a seating style that redirected attention from the front of the class to an oral-style circular form. This form is proven to deemphasize attention on a sole speaker. Neil ten Kortenaar recalls a time in Canada when a First Nation elder required participants at a workshop to sit in a style that incorporated traditional meeting practices (Reference ten Kortenaar236). According to the elder, thinking and acting differently required change, which would in turn “begin with the way we framed our questions and our discussion” (Reference ten Kortenaar236). The diffusion of power dynamics due to the spatial relations engendered by such arrangements was unfortunately not possible in my class. One way of circumventing this obstacle was for me to move around the classroom and sit at different vantage points during discussion. In other words, instructors must use the tools at our disposal to improvise.

In this light, my suggestion is for African departments to continue the process toward decolonizing the literature curriculum by considering such methods. Institutions across the continent might not be able to compete with counterparts in the Global North in terms of resources and funding, but the key is to use the tools at our disposal to our advantage. In my opinion, the primary advantage is place, as the city in which the class is being held is already African. Place then lends to aspects of culture that engender experiential learning, as students learn by experiencing the environment around them through scholarly engagement, including interviews in this case. In other cases, surveys, case studies, archival research, and other methods of inquiry can enable students to realize firsthand the potential of their environment, causing a rethink of conventional modes of pedagogical engagement.

Arguably, these suggestions will not necessarily result in reaching the point of being fully decolonized or uncolonizable – if either state even exists. Universities are trapped within larger global contexts that are usually beyond their purview. Regardless, incorporating alternative methods of conceptualizing the natural environment and focusing more on iterations of orality are possible ways of making African Studies become more relevant to students, leading to positive outcomes for all stakeholders.