1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder that is often chronic and negatively affects a patient’s quality of life [Reference Suvisaari, Keinanen, Eskelinen and Mantere1]. Schizophrenia has a lifetime prevalence of 1.0%–1.5% [Reference Pedersen, Mors, Bertelsen, Waltoft, Agerbo and McGrath2, Reference Perälä, Suvisaari, Saarni, Kuoppasalmi, Isometsä and Pirkola3]. Schizophrenia is associated with substantial premature death and mortality rate twice as high as that of the general population (GP) [Reference Laursen, Munk-Olsen and Vestergaard4–Reference Hjorthoj, Sturup, McGrath and Nordentoft6]. One meta-analysis by Carsten Hjorthøj and colleagues showed that patients with schizophrenia die 14.5 years earlier than general population and noted an urgent need for interventions to bridge the mortality gap for patients with schizophrenia, in particular to deal with metabolic syndrome and risks of vascular complications.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an endocrine and metabolic disorders with impaired insulin secretion and insulin resistance leading to hyperglycemia and may cause macrovascular and microvascular complications [Reference ADA7]. DM and its complications impose a heavy burden not only at the personal level but also the global level [Reference Lin, Hsu, Chen, Liu and Li8, Reference Amos, McCarty and Zimmet9]. In Asia, type 2 DM (T2DM) became a major public health concern for ethnic Chinese populations in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, and the prevalence of T2DM among the adult ethnic Chinese populations in these countries has reached 20% [Reference Lin, Hsu, Chen, Liu and Li8, Reference Quan, Li, Pang, Choi, Siu and Tang10].

Schizophrenia has high endogenous risk with diabetes [Reference Rajkumar, Horsdal, Wimberley, Cohen, Mors and Børglum11]. In 1879, Sir Henry Maudsley in Pathology of Mind wrote, ‘Diabetes is a disease which often shows itself in families in which insanity prevails’ [Reference Maudsley12]. In addition, leading researchers such as Kraepelin E. (1983) and Bleuler, E. (1911) had discussed whether altered energy metabolism should be part of the disease picture of schizophrenia [Reference Andreassen13]. Long before antipsychotic drugs became a standard type of therapy, studies had shown abnormal glucose tolerance in patients with ‘dementia praecox’ (schizophrenia) [Reference Rajkumar, Horsdal, Wimberley, Cohen, Mors and Børglum11, Reference Raphael and Parsons14, Reference Ryan and Thakore15]. Rajkumar et al. found individuals with schizophrenia were at an approximately three times higher risk of diabetes than the general population before receiving any antipsychotics mediations (drug-naïve). This finding demonstrated that diabetes is associated with schizophrenia independently of treatment with antipsychotic drugs [Reference Rajkumar, Horsdal, Wimberley, Cohen, Mors and Børglum11].

Existing evidences for the genetic correlation between schizophrenia and T2DM were still mixed. One current study used data from genome-wide association studies to test the presence of causal relationships between schizophrenia and T2DM and found no causal relationships or shared mechanisms between schizophrenia and impaired glucose homeostasis [Reference Polimanti, Gelernter and Stein16]. On the other hand, many studies suggested schizophrenia and T2DM may share genetic (such as TCF7L2 Gene) and familial risk factors [Reference Andreassen13, Reference Foley, Mackinnon, Morgan, Watts, Castle and Waterreus17, Reference Hansen, Ingason, Djurovic, Melle, Fenger and Gustafsson18]. Gene pathways that have been associated with T2DM and schizophrenia may include calcium, g-secretase-mediated ErbB4, adipocytokine, insulin, and AKT signaling [Reference Liu, Li, Zhang, Deng, Yi and Shi19]. The genetic variants may increase both the risk of diabetes and vulnerability to schizophrenia [Reference Andreassen, Djurovic, Thompson, Schork, Kendler and O’Donovan20].

Many studies have examined incidence or prevalence of diabetes in patients with schizophrenia given the possible onset of schizophrenia is much earlier than the T2DM [Reference Chien, Hsu, Lin, Bih, Chou and Chou21–Reference Vancampfort, Correll, Galling, Probst, De Hert and Ward25]. However, very few have investigated the prevalence of schizophrenia among patients with T2DM. The prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM will not only reflect the proportion of a T2DM population that has onset risk of schizophrenia at a certain point of time before they developed T2DM, but also will reflect the potential premature mortality risks that may affect the duration of the schizophrenia in patients with T2D. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM using the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) database and provide information on public health promotion efforts. Specifically, we first investigated the prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM from 2000 to 2010 and then compared factors for schizophrenia associated with these patients and the general population. Finally, we analysed the risk factors associated with schizophrenia in patients with T2DM.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

The Taiwan NHI program is a mandatory, single-payer system that was established in 1995; approximately 98% of Taiwanese residents are enrolled in the NHI program, and almost all medical care providers in Taiwan, including those employed at medical and primary care centres, are contracted by the NHI Administration (NHIA) to provide outpatient and inpatient services. All health care providers make claims to the NHI to receive monthly reimbursements for their medical fees. Related claim records include inpatient, ambulatory, and home care visits and associated information such as patient demographic characteristics, clinical details, health care utilisation, and expenditure.

2.2. Sample

This retrospective cohort study analysed a random sample of patients selected from all NHI enrolees from 2000 to 2010. In 2010, the NHI program provided the medical claims data of 1 million randomly selected patients (approximately 4.5% of all enrolees) for research on health services. The registration and claims data collected by the NHI program for these patients constitutes the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2010 (LHID 2010). The sample group did not significantly differ from all enrolees in terms of age, sex, or average insured payroll-related amount. This study analysed a sample of 715,756 patients aged ≥20 years from the LHID 2010.

2.3. Definitions of T2DM and schizophrenia

The Taiwan NHI claims data are based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes. These data provided a useful structure for using ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes to identify patients with T2DM and schizophrenia. This study analysed patients who had at least two service claims for ambulatory care or one service claim for inpatient care for a principal diagnosis of T2DM (ICD-9-CM codes 250.x0 and 250.x2) [Reference Huang, Lin, Lee, Chang and Chiu26–Reference Huang, Chiu, Hsieh, Yen, Lee and Chang28]. To deal with patients may have a diagnosis of schizophrenia in one but none of the subsequent contacts, we followed Chien et al. approach and defined schizophrenia as a record of at least one outpatient or inpatient service claim for a principal diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM code 295.xx) from 2000 to 2010 [Reference Chien, Hsu, Lin, Bih, Chou and Chou21, Reference Chien, Chou, Lin, Bih, Chou and Chang29, Reference Chien, Chou, Lin, Bih and Chou30].

2.4. Prevalence of schizophrenia

The prevalence of schizophrenia in the GP was calculated by dividing the number of patients with schizophrenia by the total number of study patients. The prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM was calculated by dividing the total number of patients with T2DM by the number of patients with schizophrenia.

2.5. Measurements

The demographic characteristics of the patients, including age, sex, residential area, residential urbanisation level, income, comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and duration of DM, were obtained from each patient file retrieved from the NHI database. Patients were classified into seven age groups, namely 20–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, 71–80, and ≥80 years. Residential area was classified into five geographical regions of Taiwan, namely northern, central, southern, and eastern Taiwan and offshore islets or other areas. Urbanisation level was categorised as rural or urban. Average monthly income was classified into six categories: ≤NT$17,280, NT$17,281–NT$22,880, NT$22,881–NT$28,800, NT$28,801–NT$36,300, NT$36,301–NT$45,800, and >NT$45,800. Comorbidities included myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, hemiplegia or paraplegia, renal disease, and cerebrovascular disease. The CCIs were defined as 0, 1–2, and >2. The duration of DM (years) was classified into four categories: ≤3, 3–6 (including the sixth year), 6–9 (including the ninth year), and >9.

Oral antidiabetic therapy (ADT) was categorised into five groups: metformin (anatomical therapeutic chemical [ATC] code A10BA), sulfonylureas (ATC code A10BB), meglitinides (ATC code A10BX), thiazolidinediones (ATC code A10BG), and an α-glucosidase inhibitor (ATC code A10BF). Insulin injection therapy was classified as rapid-acting (ATC code A10AB), intermediate-acting (ATC code A10AC), long-acting (ATC code A10AE), and combination (ATC code A10AD) therapy.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The distribution of characteristics was compared among the three groups of patients, namely T2DM with schizophrenia, T2DM without schizophrenia, and the GP. Chi-squared (χ2) and t tests were conducted to determine categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Generalised linear mixed models assuming a Poisson distribution were used to compare the prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM and the GP. The prevalence ratios (PRs) in the T2DM and GP groups were calculated and compared using a log-binomial model. A multiple logistic regression model was used to estimate the adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for determining the association between schizophrenia and T2DM in patients with T2DM, as well as the independent risk factors. The Joinpoint Regression Program (Version 4.2.0.2; National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to estimate trends related to the prevalence of schizophrenia. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical tests were double-sided and p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

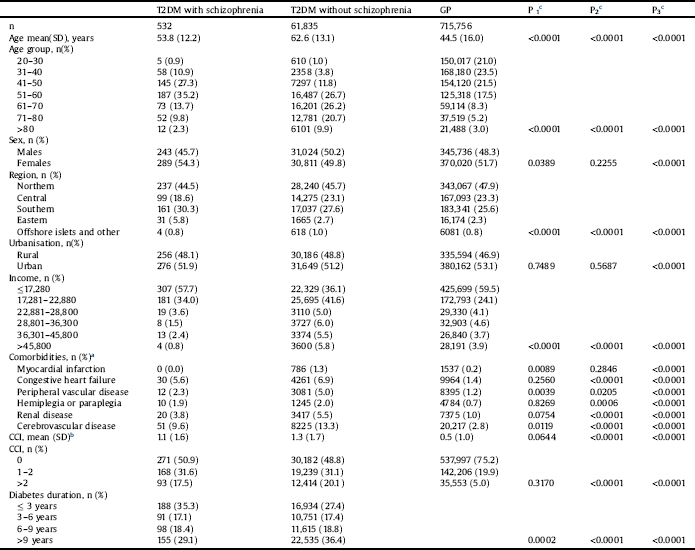

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the patients in all three groups, (T2DM with schizophrenia group n = 532, T2DM without schizophrenia group n = 61,835, and the GP group n = 715,756) including age, sex, residential area, urbanisation level, income, comorbidities, CCI score, and duration of DM in 2010. Except for urbanisation level, comorbidities (congestive heart failure, hemiplegia or paraplegia, and renal disease) and CCI, the demographic characteristics significantly differed between the T2DM with schizophrenia and T2DM without schizophrenia groups. Except for sex, urbanisation, and comorbidities (myocardial infarction), all demographic characteristics significantly differed between the GP and T2DM with schizophrenia groups. All demographic characteristics significantly differed between the GP and T2DM without schizophrenia groups.

Table 1 Characteristics of type 2 diabetes mellitus with and without schizophrenia, and general population in year 2010.

a Comorbidities was defined as ≥3 outpatient claims.

b CCI: Charlson comorbidity index for each comorbidity was defined as ≥3 outpatient claims.

c T-tests were used to compare continuous variables and chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables between two groups. The significant levels were indicated as P1, P2 and P3 (P1: T2DM with schizophrenia versus T2DM without schizophrenia; P2: T2DM with schizophrenia versus GP; P3: T2DM without schizophrenia versus GP).

Fig. 1 compares the temporal trends in the prevalence of schizophrenia from 2000 to 2010. During this period, the prevalence of schizophrenia increased from 0.64% to 0.85% in the T2DM group and from 0.37% to 0.56% in the GP group. The prevalence was significantly (P < 0.0001) higher in the T2DM group than in the GP group. The annual PRs for schizophrenia in the T2DM group were significant from 2000 to 2010 compared with the GP group (P = 0.0149). The ratio decreased from 1.73 in 2000 to 1.53 in 2010.

Fig. 1. Prevalence of schizophrenia in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus and general population, prevalence ratios of schizophrenia.

Fig. 1 shows the temporal trend in prevalence of schizophrenia from 2000 to 2010. The prevalence of schizophrenia increased from 0.64% to 0.85% in type 2 diabetes mellitus and 0.37% to 0.56% in general population. The prevalence of schizophrenia in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus were higher than those in the general population with significant difference from 2000 to 2010 (p < 0.0001).

The prevalence ratios of schizophrenia by years in the type 2 diabetes mellitus, compared with the general population, were significant from 2000 to 2010 (p = 0.0149). The type 2 diabetes mellitus-to-general population decreased from 1.73 in 2000 to 1.53 in 2010.

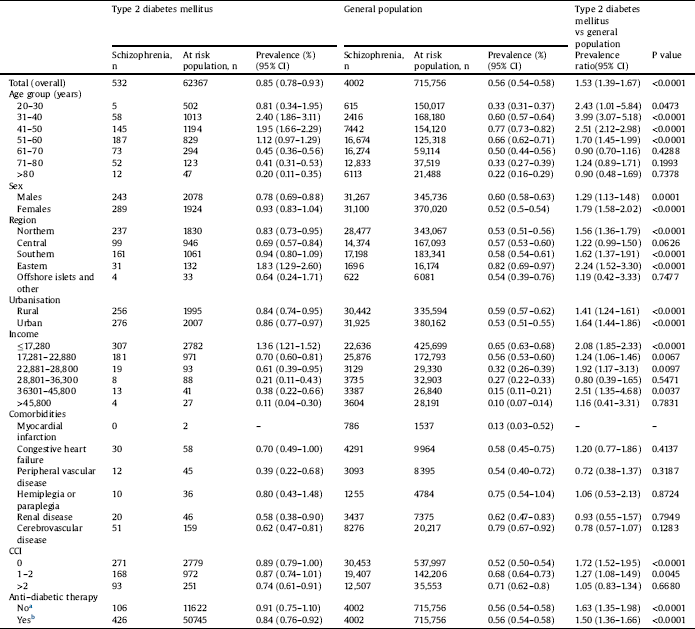

Table 2 compares the prevalence of schizophrenia between the T2DM and GP groups in 2010. The 1-year prevalence rate of schizophrenia was significantly higher in the T2DM group than in the GP group (0.85% vs. 0.56%; PR: 1.53; 95% CI: 1.39–1.67; P < 0.0001). The 1-year prevalence of schizophrenia was higher in patients with T2DM who had received ADT than in the GP (0.84% vs. 0.56%) and higher in patients with T2DM who had not received ADT than in the GP (0.91% vs. 0.56%). Patients with the following characteristics had a higher prevalence of schizophrenia in the T2DM group than in the GP group: those aged 20–30, 31–40, 41–50, or 51–60 years; men and women; those residing in all areas except for central Taiwan and offshore islets; those living in urban and rural areas; those with incomes of ≤NT$17,280, NT$17,281–NT$22,880, NT$22,881–NT$28,800, NT$36,301–NT$45,800; and those with CCI scores of 0 and 1–2.

Table 2 Prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with type 2 DM and general population in year 2010.

a Type 2 diabetes patients without anti-diabetic therapy compared with the general population.

b Type 2 diabetes patients with anti-diabetic therapy compared with the general population.

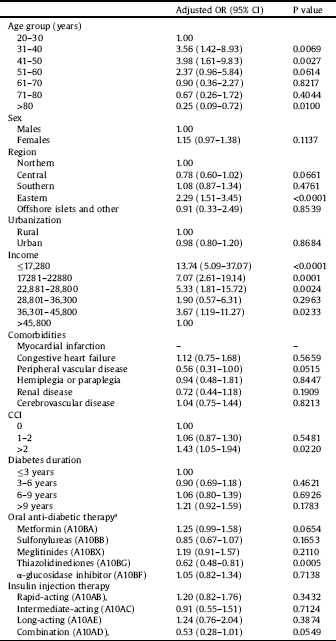

Table 3 shows the results of multiple logistic regression analysis for factors associated with the prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM. The prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM was associated with the ages of 31–40 and 41–50 years; residence in eastern Taiwan; income of ≤NT$17,280, NT$17,281–NT$22,880, NT$22,881–NT$28,800, or NT$36,301–NT$45,800; and CCI > 2; however, the prevalence was lower in patients aged ≥80 years and those prescribed thiazolidinediones.

Table 3 Adjusted odds ratio of factors with prevalence of schizophrenia in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus in year 2010 (N = 62,367).

Income: New Taiwan Dollar (NTD).

Comorbidities was defined as ≥3 outpatient claims.

CCI: Charlson comorbidity index for each comorbidity was defined as ≥3 outpatient claims.

a Oral anti-diabetic therapy and insulin injection therapy for each Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code were defined as ≥3 outpatient claims.

4. Discussion

This study was the first to use the population-based NHI dataset to estimate the prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM and the GP in Taiwan. Because the NHI program covers 98% of Taiwan’s population, the prevalence data obtained from this study approximated the actual distribution of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM and in the GP in Taiwan. To the best of our knowledge, few or no real-world data are available regarding diagnoses of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM. Most previous studies have focused on the prevalence of T2DM in patients with schizophrenia rather than that of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM [Reference Stubbs, Vancampfort, De Hert and Mitchell31–Reference Sugai, Suzuki, Yamazaki, Shimoda, Mori and Ozeki33]. Another unique feature of the current study was that it analysed a specific Asian population (i.e., ethnic Han Chinese).

Our study findings indicated that 1-year prevalence of schizophrenia in 2010 was higher in the T2DM group (0.85%) than in the GP group (0.56%). From 2000 to 2010, the prevalence of schizophrenia was significantly higher in the T2DM group (0.64%–0.85%) than in the GP group (0.37%–0.56%) and the relative risk significantly increased from a factor of 1.53 to one of 1.73 (Fig. 1). In 2010, the 1-year prevalence of treated schizophrenia in the GP was 0.56%, which was lower than the corresponding prevalence of 1.25% in Hong Kong [Reference Chang, Wong, Chen, Lam, Chan and Ng34]. However, Chien et al. showed that the cumulative prevalence of schizophrenia in the GP increased from 0.33% to 0.64% from 1996 to 2001 in Taiwan [Reference Chien, Chou, Lin, Bih, Chou and Chang29].

In addition, we found compared with GP, the prevalence of schizophrenia was observed significantly higher in patients with T2DM with earlier ages less than 60 years old (Table2). Supposedly, prevalence is the proportion of a population that has a condition at a specific time, and will be influenced by both the rate at which incident cases are occurring and the average duration of the disease [Reference Aschengrau and Seage35]. Therefore, the prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM may not only reflect the proportion of a T2DM population that has onset risk of schizophrenia at a certain point of time before they developed T2DM, but also the potential premature mortality risks that may affect the duration of the schizophrenia in patients with T2DM [Reference Hjorthoj, Sturup, McGrath and Nordentoft6, Reference Galletly36]. If an effective intervention program can reduce premature mortality, the prevalence will increase, holding the incidence rate of schizophrenia constant. Effective intervention can be suicide prevention program, or non-suicidal prevention program such as life style change intervention or improvement compliance in diabetes and schizophrenia treatments for reducing potential premature death due to diabetes or cardiovascular diseases [Reference Galletly36–Reference Suetani, Whiteford and McGrath38].

Table 3 shows the results of multiple logistic regression analyses for factors associated with the prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM. No such information on the factors of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM was previously available. The prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM was highest in those aged 31–40 and 41–50 years and lowest in those aged ≥80 years. A study conducted in Taiwan revealed that advanced age was an independent factor associated with DM in patients with schizophrenia [Reference Hung, Wu and Lin23]. In our study, an increased prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM was observed in those residing in eastern Taiwan; this could have been attributed to the presence of two large psychiatric hospitals in this region. In addition, most of our patients were at a relatively low income level; low socioeconomic status is a risk factor of DM [Reference Hoffman39]. CCI > 2 is another risk factor that was revealed in our study. Hypertension and hyperlipidaemia were the risk factors of diabetes in patients with schizophrenia in a previous study from Taiwan [Reference Hsu, Chien, Lin, Chou and Chou22]. A significant difference in the usage of thiazolidinediones exists among patients with T2DM and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia and antipsychotic agents induce metabolic syndrome and obesity. In addition, thiazolidinediones induce weight gain though various mechanisms. Hence, their use is not recommended for patients with T2DM and schizophrenia to prevent further weight gain, which can lead to adverse cardiovascular outcomes [Reference Wilding40]. By contrast, thiazolidinediones exert a neuroprotective effect through stabilizing a patient’s metabolic profile and anti-inflammation to eliminate psychological symptoms [Reference Smith, Jin, Li, Bark, Shekhar and Dwivedi41].

The present study estimated the prevalence of schizophrenia in a large, randomly selected, population-based NHI sample of patients with T2DM, and also in the GP. Insurance data are useful for studying the prevalence of schizophrenia in patients with T2DM because of the numerous patients available for data sampling. Using a health insurance database eliminates the need to spend money and conduct time-consuming psychiatric assessments, as well as the need to collect longitudinal data on the prevalence of schizophrenia and its associated risk factors [Reference Huang, Lin, Lee, Chang and Chiu26, Reference Chien, Chou, Lin, Bih, Chou and Chang29]. However, several limitations needed to be addressed. First, the limitations of a database study may still exist regarding the potential for inconsistencies in the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or T2DM, reduced reliability and validity of secondary data, dual diagnoses, and over- and under-diagnosis [Reference Huang, Lin, Lee, Chang and Chiu26, Reference Liptzin, Regier and Goldberg42, Reference Katon, Rutter, Simon, Lin, Ludman and Ciechanowski43]. Nevertheless, one study by Chien et al. compared prevalence of psychiatric disorders among National Health Insurance enrolees in Taiwan and the results from community survey study. Their prevalence results were validated and within the range of other previous community survey study. The prevalence of schizophrenic disorder (ICD-9-CM 295) was about 0.44% in year 2000 [Reference Chien, Chou, Lin, Bih and Chou30]. Second, several essential variables were not assessed in the administrative claim data, including lifestyle factors, physical activity, educational level, occupation, marital status, blood glucose control, glycaemic level, and body weight. Third, given the study data periods from year 2000, we could not track the number of years since type 2 diabetes or schizophrenia were diagnosed or identify whether patients were newly diagnosed. Future study may further look at the prevalence of schizophrenia in patients who developed type 2 diabetes to examine if antipsychotic treatment may have inflated the rate of T2DM in those with schizophrenia. Finally, differences in genetics, obesity levels, diets, cultures, lifestyles, and medical resources may exist between ethnic Han Chinese and Western populations [Reference Huang, Lin, Lee, Chang and Chiu26]. The study results from populations in Taiwan may not be generalized to other populations in other counties.

In conclusion, this study found the prevalence of schizophrenia from 2000 to 2010 was significantly higher in patients with T2DM than in the GP, and the prevalence of schizophrenia increased from 0.64% to 0.85% in patients with T2DM from 2000 to 2010. Compared with GP, the prevalence of schizophrenia was observed higher in patients with T2DM with less than 60 years old. These results suggest that physicians and public health officials must develop effective prevention and treatment strategies to carefully care those patients who were comorbid with both T2DM and schizophrenia, particularly those who have the potential premature mortality risks that may affect the duration of the schizophrenia in patients with T2DM.

Conflict of interests

We declare that none of the authors has a conflict of interest with regard to this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH105-5T08). This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health and managed by National Health Research Institutes (NHIRD-100-100 and NHIRD-102-135). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the aforementioned agencies. This manuscript was edited by Wallace Academic Editing.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.