Malacca Portuguese Creole (MPC) (ISO 639-3; code: mcm), popularly known as Malacca Portuguese or locally as (Papiá) Cristang, belongs to the group of Portuguese-lexified creoles of (South)east Asia, which includes the extinct varieties of Batavia/Tugu (Maurer Reference Maurer2013) and Bidau, East Timor (Baxter Reference Baxter1990), and the moribund variety of Macau (Baxter Reference Baxter and Carvalho2009). MPC has its origins in the Portuguese presence in Malacca, and like the other creoles in this subset, it is genetically related to the Portuguese Creoles of South Asia (Holm Reference Holm1988, Cardoso, Baxter & Nunes Reference Cardoso, Baxter and Nunes2012).

In Malacca, intermarriage between the Portuguese, locals (including Malays, Chinese and Indians), as well as Dutch and English during the subsequent colonial periods, resulted in a hybrid community whose descendants continue to reside in Malaysia (Baxter Reference Baxter2005). The largest concentration of MPC speakers in Malaysia is in a village known as the Portuguese Settlement located on the coast of Malacca, approximately 145 km south of the capital city, Kuala Lumpur. The Settlement has an estimated population of 1000 people (personal communication with the village head in 2015). The number of fluent MPC speakers has declined over the years, especially among younger speakers. MPC is ‘the last vital variety of a group of East and Southeast Asian Creole Portuguese languages’ (Baxter Reference Baxter2012a: 115) and is classified as one of the endangered languages of Malaysia, by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger (Moseley Reference Moseley2010). However, there are ongoing efforts to revitalise the language by the community (Pillai, Phillip & Soh Reference Pillai, Phillip, Soh, Peter Pericles and Aravossitas2017). These include language classes at the Portuguese Settlement and the publication of a teaching book (Singho et al. Reference Singho, Singho, Sta Maria, Pinto, Pillai, Kajita and Phillip2016).

Thus far, the most detailed study on the sound system of MPC is the non-instrumental description by Baxter (Reference Baxter1988) as part of his grammar of MPC. Baxter (Reference Baxter1988) outlined the phonological system of MPC describing the consonant and vowel qualities based on word positions. Recent instrumental studies of the sounds of MPC (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter, Pillai, Abdullah and Mustafa2013, Pillai, Chan & Baxter Reference Pillai, Chan and Baxter2015) provide a more detailed account, indicating that the phoneme inventory has similarities with Malay. However, MPC differs from Malay as it has lexical stress, and this is bound to affect its overall prosodic qualities.

For the purposes of this paper, a female native speaker of MPC contributed to our recordings. We chose a female speaker because most of the male speakers tended to work outside the Settlement and thus have more external language contact (see Pillai et al. Reference Pillai, Chan and Baxter2015). The speaker was 63 years old at the time of the recordings and gave written consent to be recorded. She grew up and still lives in the Portuguese Settlement. She frequently uses MPC with family members and others in the Settlement. She is actively involved in revitalisation efforts of MPC. In terms of education, she completed her secondary school education, and currently teaches part-time at the Settlement. Given Malaysia’s multilingual context, she also speaks the Malaysian variety of English (Pillai Reference Pillai, Kortmann and Lunkenheimer2012) and the national language, Malay.

The speaker was not given a written text but asked to narrate a story based on a series of pictures which loosely depict ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ story. For the recordings of the individual words in the consonant and vowel inventories, and other individual words used as examples, the English equivalent of the words were read out to the speaker, and she was asked to produce the equivalent word in MPC. This was done because MPC is a spoken variety and is generally not learnt formally outside the home environment. Thus, giving her written texts to read would have made it an artificial task, and possibly compromised her production of the sounds. The words for the consonant and vowel inventories were initially taken from Baxter (Reference Baxter1988), Baxter & de Silva (Reference Baxter and de Silva2004) and Singho et al. (Reference Singho, Singho, Sta Maria, Pinto, Pillai, Kajita and Phillip2016). The recordings were carried out at the speaker’s house in the Portuguese Settlement. Where relevant, the recordings were acoustically analysed using Praat version 6.0.19 (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2016).

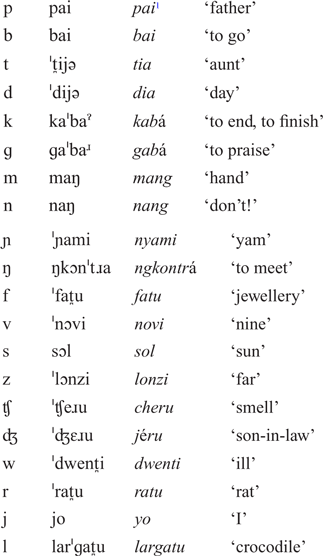

Consonants

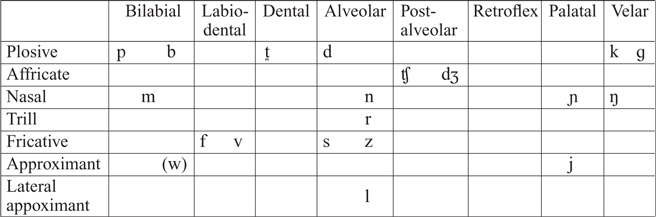

The table below presents the consonant inventory of MPC, which essentially constitutes a subset of the inventory of Standard Malay spoken in Malaysia (Maris Reference Maris1980), and yet also could be considered a subset of that of 16th-century Portuguese (Clements Reference Clements1996).

Note: /w/ is in parenthesis as it occurs infrequently in MPC.

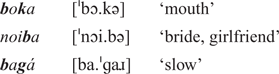

The following words illustrate the consonants of MPC:

Plosives and affricates

Similar to Malay (Shahidi & Aman Reference Shahidi and Aman2011) and Malaysian English (Shahidi & Aman Reference Shahidi and Aman2011, Phoon, Abdullah & Maclagan Reference Phoon, Abdullah and Maclagan2013), and to Portuguese (Mattos e Silva Reference Mattos and Virgínia1991, Mira Mateus Reference Mira, Elena, Mateus, Brito, Duarte and Faria2003), syllable-initial voiceless stops /p t̪ k/ are not aspirated. This lack of aspiration can be seen in the narration. The average VOTs for word-initial voiceless stops are as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 VOT of word-initial stops.

All plosives occur in syllable onsets as illustrated in the related words in the consonant inventory. Other examples of plosives occurring in syllable onsets from the recordings of individual words include:

Similar to the variety of Malay spoken in Malaysia (Maris Reference Maris1980, Zahid & Mahmood Reference Zahid and Mahmood2016), Indonesian (Soderberg & Olson Reference Zanten and van Heuven2008) and Cocos Malay (Soderberg Reference Soderberg2014), /t/ is dental, rather than alveolar (see Clynes & Deterding Reference Clynes and Deterding2011). Thus, MPC, like Malay, has a voiceless dental stop and a voiced alveolar stop. This difference in the place of articulation can be heard in the recordings of the following words:

However, in all the productions of the word notri [ˈnɔtɾ] ‘north’ in the narration, [t] rather than [t̪] was discernible. This is likely to be due to an assimilative effect of /t/ being in a consonant cluster preceding a tap /ɾ/.

The affricates /ʧ ʤ/ display a similar distribution, occurring only in syllable onsets as in the words from the consonant and vowel inventories: cheru [ˈʧe.ɹu] ‘smell’, jéru [ˈʤɛ.ɹu] ‘son-in-law’.

Fricatives

The fricatives /f v s z/ occur in word-initial and medial positions, but only /s/ occurs in word-final position, as in the word kapas [kaˈpas] ‘good at doing something’. The fricatives /v/ and /z/ are rare word-initially but can be found in syllable-initial position in the second syllable of words. Examples include, salvasang [salvɘˈsaŋ] ‘salvation’, novi [ˈnɔvi] ‘nine’, kaza [ˈkazɘ] ‘house’ and rezu [ˈɹɛzu] ‘prayer’. In some cases, /b/ and /v/ are used interchangeably: binagri [biˈnaɡɾi] or [viˈnaɡɾi] ‘vinegar’, in this instance, very likely influenced by English.

Nasals

The nasal consonants /m n ɲ ŋ/ occur in syllable onsets. However, /ɲ/ is rare word-initially as can be discerned from the dictionaries by Baxter & de Silva (Reference Baxter and de Silva2004) and Scully & Zuzarte (Reference Scully and Zuzarte2004). An example of such an occurrence is the word nyami [ˈɲami] ‘yam’. In word-final position, only /m n ŋ/ occur: dam [dam] ‘draughts’, kalkun [kalˈkun] ‘turkey’ and fesang [feˈsaŋ] ‘face’, with /m/ and /n/ occuring less frequently than /ŋ/.

The nasals /m n ŋ/ also occur in combination with a homorganic consonant in the following syllable, such as in mpodi [m.ˈpo.di] ‘cannot’ from the recording of the story. Other examples of such combinations are:

The exception to this is the word inférnu [in.ˈfɛɹ.nu] ‘hell’. In this particular word, the assimilation of the nasal to the flowing segment does not occur. In some cases, these word-initial nasals in homorganic clusters are the result of diachronic deletion of /i/ preceding the nasal consonant.

Approximants

The presence of tap and trill in apparent free variation has been registered, although the tap was felt to be predominant (Baxter Reference Baxter1988). This is confirmed by our recordings. Baxter (Reference Baxter1988) also noted the weakening and loss of /r/ in syllable-final position, and also a degree of metathesis involving /r/. In the present study, the speaker also produced the [ɹ] approximant. This tendency may be due to the influence of English, specifically the Malaysian variety of English, which uses the post-alveolar approximant.

The tap was observed in syllable-initial consonant clusters, such as in binagri [bi.ˈna.gɾi] ‘vinegar’ and pédra [ˈ pɛ.dɾə] ‘stone’. However, following [t] in such onsets, as in ngkontrá [ŋ.kɔn.ˈtɾa] ‘to meet’, a slightly devoiced tap, with friction, or the [ɹ] approximant may also occur. Elsewhere, in word-initial and syllable-initial medial positions, as in floris [ˈflo.ɹis] floris ‘flower’ and jéru [ˈʤɛ.ɹu] jéru ‘son-in-law’, [ɹ] is frequent. Yet, as seen in the narration, it may alternate with the tap in these positions, as for example in rópa [ˈɾɔ.pə] ‘clothes’ and tirá [ˈt̪i.ɾa] ‘take off’. In syllable-final position, however, the [ɹ] approximant occurs, in both internal or word-final syllables, as in nférnu [n.ˈfɛɹ.nu] ‘hell’ and bagá [ba.ˈgaɹ] ‘slow’, respectively, where it may be substantially reduced, or deleted with slight vowel lengthening.

The lateral approximant /l/ occurs in syllable onsets and coda positions such as in the following words in the story:

The average F2 value is relatively high for these words, at 1504 Hz, and thus, far apart from the F1 which had an average of 432 Hz, suggesting a clear / l/ (see Ladefoged Reference Ladefoged2003).

The approximants /w/ and /j/ occur word-initially and medially:

As single consonant onsets, they are extremely restricted in word-initial position, with /j/ occurring frequently only in yo [jo] ‘I’, and [w] in the infrequent word westi. However, they are more frequent as the second element of word-initial onsets containing consonant clusters, such as in the words siumi [ˈsju.mi] ‘jealousy’, nyami [ˈɲja.mi] ‘yam’ and dwenti [ˈdwen.t̪i] ‘ill’.

Vowels

MPC has eight vowel phonemes, /i e ɛ ə a u o ɔ/, shown in the vowel chart and Figure 1.

Figure 1: MPC F1/F2 vowel space.

The following words illustrate the vowels of MPC:

As can be seen in the vowel charts, the two high front vowels, /i/ and /e/, are relatively close to each other in the vowel space. The vowel /a/ is produced more centrally. Orthographic <a> is unstressed in word-final positions and, in such cases, tends to be produced as /ə/, for example, in the words fosa [ˈfɔsə] ‘strong’ and ropa [ˈɾɔpə] ‘clothes’ in the narration.

Pillai et al. (Reference Pillai, Rosli, Phillip, Wan Ahmad and Hassan2017) have found an acoustically verifiable distinction between the production of the vowels /e/ and /ɛ/, and between / o/ and /ɔ/ by speakers in their study, confirming the early non-instrumental accounts of Baxter (Reference Baxter1988) and Hancock (Reference Hancock2009). Initially, Baxter (Reference Baxter1988) suggested that the use of either vowel in these two sets of vowels may be broadly influenced by vowel harmony with the height of the final vowel influencing the preceding vowel, as in noiba [ˈnɔibə] girlfriend’, boka [ˈbɔkə] ‘mouth’ and pedra [ˈpɛdɾə] ‘stoneˈ (see Figure 1 for the for the relative degrees of vowel height).

Yet, subsequent work (Baxter Reference Baxter2012b) has identified the process as restricted to a minor set of word pairs that contain an etymological gender distinction for human referents, derived from Portuguese gender inflection, such as in words like bemféta [bəmˈfɛtə] ‘pretty’ and bemfetu [bəmˈfetu] ‘handsome’, wherein /ɛ/ precedes the word-final lower vowel /ə/ in words of feminine gender, and /e/ precedes the word-final high vowel /u/ in words of masculine gender.

A final point of interest is that vowels in stressed word-final open syllables may be glottalized. An example of this is the word kabá [kaˈbaʔ] ‘to end, to finish’ and nte [nˈt̪eʔ] ‘to not have, to not be’. However, the distribution of this variable phenomenon is not clear at this and thus requires further research.

There are three main diphthongs in MPC:

At this point in time, it is unclear if there is a vowel+vowel sequence in the same syllable or if there is a /j/ between the two vowels, as has been observed for Malaysian English (Pillai Reference Pillai, Manan and Rahim2014) for words like dia [ˈdi.jə] ‘day’ and tia [ˈt̪i.jə] ‘aunt’ from the consonant wordlist, and papiá [pa.pi.ˈja] ‘to talk’ and friu [ˈfɾi.ju] ‘cold’ in the narration. The same phenomenon occurs in Standard Malay, where dia ‘he, she’ is realised as two syllables, i.e. [di.jə] or [di.ja] (Teoh Reference Teoh1994).

Stress

The stress markings were assigned on the basis of auditory impressions of the recordings with reference to their spectrograms and in consultation with the speaker. With regard to the spectrograms of the recordings, it appears that the stressed syllable is longer and has a higher intensity compared to the unstressed ones. However, these correlates were more noticeable in the recordings of the word list than in the narration, where it was not always immediately obvious which syllable was being stressed. Broadly speaking, although stress is identifiable in non-monosyllabic words in the word lists, there are monosyllables that are stressed in the narration. In such cases, content monosyllables rather than function ones (e.g. prepositions, tense-aspect particles, determiners or quantifiers) are more likely to be stressed. An example of a stressed monosyllable is sol [sɔl] ‘sun’ in the narration. The need for further work on the acoustic correlates and perception of stress in MPC is warranted, especially as there is a lack of lexical stress in Malaysian English and no lexical stress in the Malaysian variety of Malay (Zanten & van Heuven Reference Zanten and van Heuven2004, Mohd. Don, Knowles & Yong Reference Mohd. Don, Knowles and Yong2008). It is also unclear how important or new information is marked in MPC. In both Malay and Malaysian English, there appears to be hardly any difference in the type of pitch accent on new and given information (Gut & Pillai Reference Pillai, Manan and Rahim2014).

In general, MPC has a large number of words displaying penultimate syllable stress, as in kaza [ˈka.zə] ‘house’, floris [ˈ flo.ɹis] ‘flower’. This is especially the case in words ending in a vowel, provided they are not verbs. A second large class of words, principally verbs, take final-syllable stress, for example, kumí [ku.ˈmi] ‘to eat’, olá [o.ˈla] ‘to see’ and kabá [ka.ˈbaʔ] ‘to end, to finish’. However, even in cases where we may predict word-final stress, such as in the case of verbs, the speaker sometimes stresses the first syllable in the following verbs in the narration of the story:

Baxter (Reference Baxter1988) noted that there may be a shift from the final to the penultimate syllable for verbs if a stressed syllable follows in the next word. This only occurred in the case of the following two words in the narration:

faze, which was always followed by the word isti [ˈis.ti] ‘this’

sinti [ˈsin.t̪i] ‘feeling’, which was followed by the words mas kenti [ˈmasˈken.t̪i] ‘very hot’

A subsequent, exploratory study (Baxter Reference Baxter2012c) found that final syllable stress in verbs is conditioned by several factors. The more prominent of these were phonological: an immediately following pause, and question intonation, both favouring word-final stress. However, morpho-syntactic factors also favoured final syllable stress: transitivity of the verb (intransitives being especially favourable), type of verb theme (verbs with final /i/ and /e/ being particularly favourable), and presence of an auxiliary verb. Nevertheless, this issue of stress assignment in verbs requires further investigation.

Transcription of recorded passage

The passage is a narrated story based on ‘The North Wind and the Sun’.

Orthographic version

Ungua dia, béntu notri kung sol, teng mpoku falasang. Béntu notri ja falá, “Keng mas fosa.” Témpu isti dos ta papiá, ungua omi ja pasá. Béntu notri ja falá kung sol, “Beng nos olá keng mas fosa.” Béntu notri falá,”Yo logu frufá mazianti. Yo logu faze isti omi tirá sa ropa.” Eli ja frufá muitu fos a. Isti omi ta fiká mas friu. Mas eli frufá mas friu isti omi ja abrasá sa ropa. Eli ja falá eli mpodi faze isti omi tirá sa ropa. Sol ja ri. Agora, sol ta falá, “yo logu faze isti omi tirá sa ropa.” Sol ja tezá sa lus. Aki omi ta sinti mas kenti. Eli mpodi aguentá, ja tirá sa ropa. Agora sol muitu alegrá. Bentu notri ja falá ke sol, “Bos mas fose di yo.”

Phonetic transcription

ˈŋwəˈdijə|ˈbɛnt̪u ˈnɔtɾi ku ŋˈ sɔ l| t̪eŋ mˈpoku faləˈsaŋ||ˈbɛ nt̪u ˈ nɔ tɾi ʤə faˈ la keŋ mas ˈ fɔsə||ˈ t̪ɛ mpu ˈ ist̪i ˈ dos t̪ə papiˈ ja|ˈŋwa ˈɔmi ʤə paˈ sa||ˈbɛ nt̪u ˈ nɔtɾi ʤəˈ fala kung ˈ sol|ˈ beŋ nos oˈ la ˈ keŋ mas ˈ fosə||ˈ bɛ nt̪u ˈ nɔtɾi faˈ la ˈ jo ˈ logu fuˈ fa maziˈ janti||ˈ jo ˈ logu ˈ faze ˈ ist̪i ˈɔmi t̪iˈɹa səˈɹɔpə|| eˈ li ʤə fuˈ fa ˈ muit̪u ˈ fɔsə||ˈ ist̪əˈɔmi ˈ t̪ə fiˈ ka ˈ mas ˈ fɹiju||ˈ mas eˈ li fuˈ fa ˈ mas ˈ fɹiju ˈ ist̪i ˈɔmi ʤa abɾəˈ sa səˈɹɔpə||ˈ eli ʤə faˈ la eˈ li mˈ podi ˈ faze ˈ ist̪i ˈɔ mi t̪iˈɾa səˈɾɔpə||ˈ sɔl ʤəˈɹi|| aˈ gɔɹə|ˈ sɔl t̪əˈ fala ˈ jo ˈ logu ˈ faze ˈ ist̪i ˈɔmi t̪iˈɾa səˈɹɔpə||ˈ sɔl ʤəˈ t̪eza səˈ lus|| aˈ ke ˈɔmi t̪əˈ sint̪i ˈ mas ˈ kent̪i|| eˈ li mˈ podi agwenˈ t̪a| ʤəˈt̪iˈɾa səˈɹɔ pə|| aˈ gɔɾəˈ sɔl ˈ muitu aleˈ gɾa||ˈ bɛ nt̪u ˈ nɔtɾi ʤəˈ fala kə sol|ˈ bos mas ˈ fɔsə di jo||

English translation

One day, the north wind and the sun, were having a small conversation (chat). The north wind said, ‘Who is stronger?’ At the time these two were talking, a man passed by. The north wind said to the sun, ‘Come let’s see who is the stronger.’ The north wind said, ‘I will blow first. I will make this man take off his clothes.’ He blew very strongly. This (the) man became very cold. The more he blew coldly, this (the) man embraced (held together) his clothes. He said that he could not make this man take off his clothes. The sun laughed. Now, the sun says, ‘I will make this man take off his clothes.’ The sun tightened the light (shone brightly). The man is feeling very hot. He cannot tolerate it, he took off his clothes. Now the sun is very happy. The north wind said to the sun, ‘You are stronger than me.’

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Fundamental Resarch Grant Scheme from the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (FP020-2015A). We would like to thank the speaker for her willingness to be recorded, and others in the community who helped in the project. We would also like to acknowledge Siti Raihan Rosli for helping with part of the data collection and Chan Min En for her input on previous versions on this paper. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S026646741900004X