1. Introduction

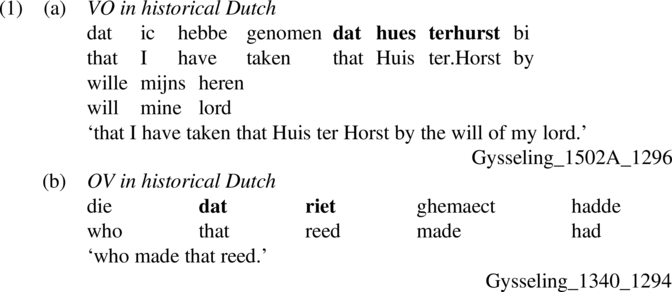

The position of direct objects in Dutch clauses has always known a certain freedom. In Middle Dutch (1150–1500) and early New Dutch (1500–1700) (henceforth referred to collectively as historical Dutch), direct object DPs appear in postverbal (VO) or preverbal position (OV), illustrated in (1), both from the end of the thirteenth century. In (1a), the object dat hues terhurst ‘that Huis ter Horst (a castle)’ is placed to the right of the main verb genomen ‘taken’, and the object dat riet ‘that reed’ in (1b) is placed to the left of the main verb ghemaect ‘made’.Footnote 2

The postverbal object position was lost from the Dutch language around the sixteenth century. However, Dutch still allows variation with respect to the position of the object vis-à-vis the position of adverbials. This phenomenon, known as scrambling, is illustrated in (2). The object het boek ‘the book’ may appear to the left or to the right of the clausal adverb waarschijnlijk ‘probably’.

OV/VO variation and scrambling have both been argued to regulate the information structural partitioning of the clause. From very early on, grammarians have been aware that given information tends to precede new information (Weil Reference Weil1844; Behaghel Reference Behaghel1909). Dutch is no exception in this regard. Preverbal objects in historical Dutch and objects that appear in a position to the left of the adverbial (scrambled objects) in present-day Dutch are often claimed to convey given information, while postverbal objects and unscrambled objects, which appear to the right of the adverbial, are claimed to convey new information (cf. Burridge Reference Burridge1993; Coussé Reference Coussé2009 on OV/VO; Schoenmakers, Poortvliet & Schaeffer Reference Schoenmakers, Poortvliet and Schaeffer2021 and sources cited there on scrambling).

This raises the question if, and if so, how, historical Dutch OV/VO variation and present-day scrambling are related. Based on a comprehensive corpus study of Dutch written between the thirteenth and nineteenth century, we demonstrate that OV/VO variation and scrambling serve a similar purpose, because in both cases the position of the object is (in part) dependent on information structure. However, while scrambling was already a syntactic option in historical Dutch, its information structural effect only emerges as the postverbal object position loses its productivity.

We demonstrate that new objects typically occur in postverbal position in earlier stages of Dutch, although they are attested in preverbal position as well. Given objects surface in preverbal position in the majority of the cases. There are no clear indications of information structural restrictions on scrambling as long as VO is a productive option in historical Dutch (until the sixteenth century). Once new objects start to appear in preverbal positions more frequently, scrambling becomes sensitive to information structure. The boundary between the information structural domains in which given and new information is expressed thus shifts from the verb to the adverbial in the so-called middle field of the clause. The loss of VO entails the loss of an important pragmatic marker, and we show that the syntax of Dutch allows enough flexibility to generate a new information structural division within the topological region to the left of the verb, with the adverbial as the novel boundary between information structural domains.

We present an analysis of Dutch object placement which allows a natural transition from a language that marks information structure by means of OV/VO variation to a strict OV language which does so by means of scrambling. We build on the antisymmetric analysis of Dutch scrambling proposed in Broekhuis (Reference Broekhuis2008), and argue that OV/VO variation and scrambling both result from the same process. Specifically, we argue that objects are generated in postverbal position and consequently move to structurally higher positions in the extended projections of VP and vP to check structural features, leaving behind copies in each intermediate position. Which of these copies is spelled out depends on (discourse-pragmatic) interface conditions. The lowest, postverbal, spell out option is lost after the sixteenth century, restricting the variation in surface position of the object to the middle field.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 sets out the key issues and patterns that play a role in Dutch object placement, from a diachronic and a syntactic perspective. Section 3 presents our approach to the corpus data. The results are presented and discussed in Section 4. Section 5 presents our analysis of Dutch clause structure. Section 6 concludes.

2. Variation in Dutch object placement

Present-day Dutch is generally considered an asymmetric SOV language, with obligatory V2 in the main clause. Koster (Reference Koster1975) was the first to argue, on the basis of a number of distributional tests, that the position of the finite verb in main clauses is derived from a clause-final position. Although the object follows the verb in main clauses with only a finite verb, Koster shows that this is a surface phenomenon. He demonstrates that verb particles are stranded in clause-final position (hij belde het meisje op ‘he calls the girl up’). In main clauses with more than one verb, the non-finite verb remains in clause-final position and the object is preverbal (hij heeft het meisje opgebeld ‘he has the girl up.called’). Since there is no V2 movement in subclauses, DP objects always precede the verb in these cases (dat hij het meisje opbelt ‘that he the girl up.calls’). From this perspective, Dutch is an SOV language. These observations do not preclude an antisymmetric (cf. Kayne Reference Kayne1994) approach to Dutch clause structure, however. In fact, in later work Koster argues that SOV-clauses in Dutch are derived from underlying SVO structure (Koster Reference Koster1999; see also Zwart Reference Zwart1993, Reference Zwart1997).Footnote 3 We will pursue such an analysis in Section 5.

The syntax of both present-day and historical Dutch is frequently approached from the perspective of topological fields, or a so-called tang ‘brace’ construction, illustrated in Table 1 (first applied to Dutch by Paardekooper Reference Paardekooper1955). In main clauses, the finite verb in V2 position marks the left bracket of the brace and the non-finite verb in clause-final position marks the right bracket. In subclauses, the complementizer serves as the left bracket and the verb(s) in clause-final position as the right bracket.

Table 1 Illustration of topological regions and the ‘brace’ construction in Dutch clauses.

The assumption of a brace construction as a descriptive template allows differentiation between a prefield (material preceding the left bracket), a middle field (material between the left and the right bracket), and a postfield (material following the right bracket). The locus of variation in object placement in historical Dutch is between the middle field and postfield: direct objects appear in the middle field (preverbally) or in the postfield (postverbally). The locus of variation in present-day Dutch is in the middle field (scrambling). We will discuss both types of variation in turn.

2.1 OV/VO variation in historical Dutch

OV/VO variation is one of the main syntactic characteristics of older (West) Germanic language varieties and sparked a vigorous debate on word order typology as well as on the analysis of individual languages (see e.g. Van Kemenade Reference Van Kemenade1987; Pintzuk Reference Pintzuk1999; Taylor & Pintzuk Reference Taylor and Pintzuk2012; De Bastiani Reference De Bastiani2019; Struik & Van Kemenade Reference Struik and van Kemenade2020, Reference Struik and van Kemenade2022 on Old English; Petrova Reference Petrova, Hinterhölzl and Petrova2009; Sapp Reference Sapp2016 on Old High German; Sapp Reference Sapp2014 on Middle High German; Walkden Reference Walkden, Bech and Eide2014; Struik Reference Struik2022b on Old Saxon and Middle Low German). This is also the case for historical Dutch, although traditional analyses often (implicitly) assume historical Dutch to be an OV language. VO order is usually accounted for by an extraposition rule, which is taken to be more liberal than in present-day Dutch, which only allows full clauses (CPs) and non-predicative PPs in postverbal position (see Zwart Reference Zwart2011).

Burridge (Reference Burridge1993: ch. 3) approaches OV/VO variation in Middle Dutch from a topological perspective, and employs the term ‘exbraciation’, that is, displacement of material to a position outside of the brace. Similarly, Neeleman & Weerman (Reference Neeleman and Weerman1992: 189) assume VO structures to be ‘leakages in the older West-Germanic OV structures’. Most studies only give a descriptive overview of observed VO constructions and do not directly address the issue of underlying clause structure (e.g. Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen and Kooij1978; De Meersman Reference De Meersman1980; Van den Berg Reference Van den Berg1980). Gerritsen (Reference Gerritsen1987), Blom (Reference Blom, Broekhuis and Fikkert2002), and De Schutter (Reference De Schutter2003) are notable exceptions, and all conclude on the basis of frequency that Middle Dutch is an OV language. Gerritsen (Reference Gerritsen1987) adds as evidence that pronouns are always OV and argues that, since Proto-Indo-European was considered an OV language, positing a change from OV to VO and then back to OV is conceptually undesirable. An argument for Blom (Reference Blom, Broekhuis and Fikkert2002) to assume that OV is the base order in Middle Dutch is that VO is only available under specific conditions: it can only be used when the object contains a relative clause or when the object belongs to the focus of the clause.

Weerman (Reference Weerman, Beukema and Coopmans1987, Reference Weerman1989) is one of the few who provides a syntactic analysis of OV/VO variation in historical Dutch. He argues that languages allow both orders at D-structure (in government-binding terms), since theta roles are assigned hierarchically and not directionally. However, constituent orders must be licensed at S-structure, which is assigned directionally following Case Theory. Weerman argues that present-day Dutch assigns case exclusively to the left, which results in basic OV order. His analysis of VO orders rests on the assumption that constituents can escape Case assignment if they have their own licensor, which Weerman claims is, at earlier stages, morphological case. This means that in Middle Dutch, which distinguished four morphological cases, the choice between OV and VO is essentially free (from a syntactic perspective). However, Dutch (largely) lost morphological case marking, which according to Weerman (Reference Weerman, Beukema and Coopmans1987, Reference Weerman1989) means that a postverbal object can no longer be licensed. As a result, VO order is lost. A potential problem for such an analysis is the observation that German retained its inflections but, like Dutch, became more rigidly SOV. This suggests that more factors come into play in the process of word order change. We will come back to this point in Section 5.2.

Much of the discussion in (recent) literature on OV/VO variation in historical West Germanic revolves around the influence of information structure. The hypothesis that preverbal objects convey given information and postverbal objects new information has been explored for many (West) Germanic language varieties (see e.g. Burridge Reference Burridge1993; Bech Reference Bech2001; Blom Reference Blom, Broekhuis and Fikkert2002; Coussé Reference Coussé2009; Petrova Reference Petrova, Hinterhölzl and Petrova2009, Reference Petrova, Nevalainen and Traugott2012; Petrova & Speyer Reference Petrova and Speyer2011; Taylor & Pintzuk Reference Taylor and Pintzuk2012; Walkden Reference Walkden, Bech and Eide2014; De Bastiani Reference De Bastiani2019; Struik & Van Kemenade Reference Struik and van Kemenade2020, Reference Struik and van Kemenade2022). Understanding the nature of the variation helps to inform the syntactic analysis of a language. Struik & Van Kemenade (Reference Struik and van Kemenade2020, Reference Struik and van Kemenade2022), for instance, show for historical English that objects in preverbal position predominantly express given information, while objects in postverbal position can be given or new. They take this as evidence for an analysis of historical English as a VO language, with leftward object movement that is driven by information structure.

The effect of information structure has also been explored in earlier studies of Middle Dutch. Burridge (Reference Burridge1993: 107), for example, claims that ‘exbraciated material is likely to be non-topical material, i.e. usually unknown information, which cannot be understood from the context and which is not shared by speaker and hearer’. Burridge, however, is concerned with all types of sentence material that can be exbraciated, and bases her conclusions on general characteristics of grammatical categories, rather than on annotation of individual objects (e.g. objects are more likely to exbraciate than subjects, because they more frequently convey new information).

Blom (Reference Blom, Broekhuis and Fikkert2002) notes that one of the factors responsible for VO order in Middle Dutch is that the object belongs to the focus of the clause as well.Footnote 4 Blom studies the characteristics of postverbal objects in three different text genres: official texts, religious texts, and narratives. She observes that objects of naming verbs, such as noemen ‘call’ and heten ‘call’, are always postverbal, and maintains that this is due to the fact that this information is never part of the common ground. She also observes that there is a large amount of VO structures in official texts, which she claims is because direct objects in these clauses ‘encode the item that is at the heart of the legal agreement’ (Blom Reference Blom, Broekhuis and Fikkert2002: 18). Similarly, Coussé (Reference Coussé2009) uses the determiner as a proxy for information structure (following Givón Reference Givón, Hammond, Moravcsik and Wirth1988) and finds a relation between the definiteness of objects and their surface position: indefinite objects, which typically convey focused information, are more likely to appear postverbally than definite objects, which typically convey non-focused information.

2.2 Scrambling in present-day Dutch

VO word order is lost from the Dutch language around the sixteenth century (see Coussé Reference Coussé2009), which restricted variation in object placement to the middle field, as in (2). While experimental and corpus studies investigating this type of variation are scarce, various syntactic analyses have been proposed to account for scrambling in the theoretical literature (Verhagen Reference Verhagen1986; Vanden Wyngaerd Reference Vanden Wyngaerd1989; Zwart Reference Zwart1993; Neeleman Reference Neeleman, Corver and van Riemsdijk1994; De Hoop Reference De Hoop1996, Reference De Hoop and Karimi2003; Neeleman & Reinhart Reference Neeleman, Reinhart, Butt and Geuder1998; Koster Reference Koster1999, Reference Koster2008; Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer2000; Broekhuis Reference Broekhuis2008; Neeleman & Van de Koot Reference Neeleman and van de Koot2008; Schoenmakers Reference Schoenmakers2020). There is a consensus that information structure also plays a crucial role in scrambling. The literature discusses topicality (or aboutness, see Reinhart Reference Reinhart1981), discourse-anaphoricity (i.e. explicit mention in previous discourse), and presuppositionality (the level of activation of a referent in the common ground; cf. accessibility in Ariel Reference Ariel1990). Schoenmakers et al. (Reference Schoenmakers, Poortvliet and Schaeffer2021) find in a language production study that the topicality status and the discourse-anaphoricity of definite objects induce distinct effects on their position in the middle field. In general, however, scrambling follows the given-before-new pattern: given objects (topical or anaphoric) are most frequently produced to the left of the adverb (i.e. in scrambled position), while new objects (focused or non-anaphoric) are typically located to their right (i.e. in unscrambled position) (see also Verhagen Reference Verhagen1986).

Such an information structural partitioning is supported by the fact that pronouns, which typically convey given information, appear in scrambled position almost obligatorily (but not if they receive contrastive stress, for example, see Bouma & De Hoop Reference Bouma and de Hoop2008), as illustrated in (3).

This contrast is reflected in the corpus data reported in Van Bergen & De Swart (Reference Van Bergen, de Swart, Schardl, Walkow and Abdurrahman2009, Reference Van Bergen and de Swart2010), who investigate the scrambling behavior of different kinds of objects in spoken Dutch: 99% of pronouns in their dataset appear in scrambled position. Only 2% of indefinite objects, which typically convey new information, are scrambled. They find most variation with proper names (53% scrambled). Van Bergen & De Swart find only 12% of definite objects in scrambled position. This is surprising, given that, on the assumption that the determiner can be used as a proxy for information structure (Coussé Reference Coussé2009), definite objects are expected to convey given information and hence to appear in scrambled position. Even more striking is that the authors also annotate for anaphoricity and find that only 22% of anaphoric definite objects are located in scrambled position. This finding contradicts most theoretical literature where a strict discourse template is postulated in which given objects obligatorily occur in scrambled position (see Schoenmakers Reference Schoenmakers2022; Broekhuis Reference Broekhuis2021 for discussion).

Van Bergen & De Swart (Reference Van Bergen, de Swart, Schardl, Walkow and Abdurrahman2009) note that speakers are more likely to use a pronoun instead of a full DP when the object is anaphoric. However, Schoenmakers & De Swart (Reference Schoenmakers, de Swart, Gattnar, Hörnig, Störzer and Featherston2019) find in an experimental study, in which participants are forced to use definite DP objects, that they are produced in scrambled position in 45% of the trials with a clause adverb. Schoenmakers et al. (Reference Schoenmakers, Poortvliet and Schaeffer2021) find in a follow-up study that definite objects which are anaphoric are produced in scrambled position from 42% to 57% (depending on the condition), whereas non-anaphoric (focused) definite objects are produced in scrambled position in only 34.5% of the trials. Even though the proportion of scrambled anaphoric definites is much higher than that in the corpus data reported in Van Bergen & De Swart (Reference Van Bergen, de Swart, Schardl, Walkow and Abdurrahman2009, Reference Van Bergen and de Swart2010), the information structural partitioning in scrambling clauses in both studies is nowhere near categorical.

These data cannot readily be accounted for by most theoretical approaches to Dutch scrambling, which link the information structural effect to a post-syntactic mapping rule that maps a discourse-anaphoric interpretation onto the scrambled position (e.g. Neeleman & Van de Koot Reference Neeleman and van de Koot2008), or to Cinque’s (Reference Cinque1993) Nuclear Stress Rule: objects in unscrambled position typically carry the main stress of the clause, and given that stress corresponds with new information focus assignment (e.g. Chomsky Reference Chomsky, Steinberg and Jakobovits1971; Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972; Cinque Reference Cinque1993), objects in this position are interpreted as information that is new to the discourse (e.g. Neeleman & Reinhart Reference Neeleman, Reinhart, Butt and Geuder1998; Broekhuis Reference Broekhuis2008). Objects in scrambled position, by contrast, undergo a process of anaphoric destressing (Reinhart Reference Reinhart2006) and convey information that is already available in the context set. Such analyses predict that given objects obligatorily occur in scrambled position and new objects in unscrambled position (but see Van der Does & De Hoop Reference Van der Does and de Hoop1998; De Hoop Reference De Hoop and Karimi2003 for notable exceptions).

Little is known about the diachrony of scrambling in Dutch. To our knowledge, this phenomenon has never been addressed in the literature on historical Dutch syntax. It is easy to show, however, that it is at least a syntactic option: we find objects in a position immediately left-adjacent to the verb, as in (4a), but also in a position on the left of an adverbial, as in (4b).

It is not clear, however, whether scrambling was already information structurally motivated in historical Dutch in the same way as in present-day Dutch. This raises the question if, and how, scrambling is related to OV/VO variation.

2.3 The relation between OV/VO variation and scrambling

The discussion above shows that Dutch allows (at least) three object positions throughout its history: V-O, Adv-O-V, and O-Adv-V. The literature suggests that OV/VO variation in historical Dutch and scrambling in present-day Dutch serve a similar purpose; they differentiate the information structural domains of given and new information. This leads to the hypothesis that the two types of variation are diachronically related: the loss of VO entails the loss of an important pragmatic marker and hence entails a shift in the locus of information structure encoding.

The next sections report on a corpus study of historical Dutch in which we investigate how the relation between syntax and information structure develops over time. We hypothesize that there is an information structural effect on OV/VO in the earliest part of our dataset. More specifically, we expect to find given objects in preverbal position, while new objects surface in postverbal position. As long as VO is a productive option in Dutch, we do not expect an information structural effect of scrambling since we expect OV objects to be given. As the frequency of VO reduces, the verb loses its status as the boundary between information structural domains. Information structure then ‘exploits’ syntax to find a new way to distinguish between given and new information. Specifically, we expect that scrambling does not have a clear discourse-related function in the earlier stages of Dutch and only becomes information structurally distinctive around the sixteenth century when VO is no longer a productive syntactic option.

3. Materials and methodology

We studied a comprehensive selection of historical Dutch texts to test the hypotheses introduced in the previous section. Relevant clauses were manually collected from various sources over the time period between 1250 and 1900. The online version of Corpus Gysseling (Reference Gysseling2021) was used for thirteenth century material and the Corpus Van Reenen–Mulder (CRM) (Van Reenen & Mulder Reference Van Reenen and Mulder1993) for fourteenth century material. The majority of the texts in CRM are short charters, so we supplemented this material with several longer texts from the Corpus Laatmiddel- en Vroegnieuwnederlands (CLVN) (Van der Sijs, Van Kemenade & Rem Reference Van der Sijs, van Kemenade and Rem2018). The CLVN was also the source for fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth century material. We used the Compilatiecorpus Historisch Nederlands (CHN) (Coussé Reference Coussé2010) for narrative texts from the late sixteenth century onwards. From each corpus, a representative sample of texts was selected based on the localization of each text. We excluded texts from the (north-)eastern part of the Netherlands to avoid potential influence from German, Low Saxon, and Frisian. The main body of texts originate from Holland, Utrecht, and Flanders. We supplemented the dataset with several religious texts to balance the overwhelmingly official nature of the earlier texts. This procedure resulted in a corpus of approximately 700,000 words. A complete overview of the material is given in Appendix A.

For each text in our selection, we manually selected all subclauses with a direct object, a finite verb (excluding forms of zijn ‘be’ to exclude passives), and a non-finite verb (excluding te ‘to’ infinitives). Selecting clauses with two verbs ensures that there is no effect of (finite) verb movement on the order of the main verb and the object. Indirect objects were excluded, because their behavior is not comparable to that of direct objects. Although indirect objects do appear in postverbal position in historical Dutch, it is unclear whether they are subject to the same constraints as direct objects. Burridge (Reference Burridge1993) notes that indirect objects are not as likely to appear postverbally as direct objects, but this might be because they are mostly pronouns in her sample. Research on Old English indicates that there is no conclusive regularity in the placement of indirect objects (Koopman Reference Koopman1990) and that information structure does not seem to play a role (Struik & Van Kemenade Reference Struik and van Kemenade2020). We leave the behavior of indirect objects for future research. Further, we excluded pronominal objects, as these are categorically OV. While it might be argued that pronouns are always preverbal because they are prototypically given, their syntactic status is different from that of full DPs. Pronouns are prosodically light elements and might be analyzed as clitics (see Van Kemenade Reference Van Kemenade1987; Van Bergen Reference Van Bergen2003; Pintzuk Reference Pintzuk2005 and the sources cited there for discussion of the status of pronouns in Old English; and Zwart Reference Zwart, Halpern and Zwicky1996 for a discussion of Dutch weak pronouns as clitics). We also excluded clausal objects as these are categorically VO (cf. Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen1987; Burridge Reference Burridge1993).

After collecting relevant clauses, each object was manually annotated for information status. Our annotation is based on a simplified version of the Pentaset (Komen Reference Komen2013) and follows the methodology in Struik & Van Kemenade (Reference Struik and van Kemenade2020, Reference Struik and van Kemenade2022). The annotation is based on the referentiality and anaphoricity of each individual object in the discourse, and, crucially, not on the morphosyntactic properties of the object (e.g. as in Coussé Reference Coussé2009). The main reason for this is that the mapping between the morphosyntactic properties of an object and its information status is not one-to-one. For instance, we find definite objects in all categories of our annotation scheme, as definiteness may indicate anaphoricity, but also uniqueness and/or existence without an explicit antecedent. Second, the determiner system (and hence the way definiteness and information structure are marked) is not diachronically stable, yet it has received little attention in the literature on Middle Dutch (but see Van de Velde Reference Van de Velde2010). Studying the diachronic effect of information structure on word order variation using the definiteness system with synchronic assumptions as a proxy would confound our conclusions: the results would then reflect the effect on a changing determiner system on OV/VO variation and scrambling, but not the effect of information structure itself.

We annotate objects as given if they are mentioned in the preceding discourse (Identity in the Pentaset), as in (5a). The object die vorseide kerke ‘the aforementioned church’ is mentioned in the preceding discourse, which is also indicated by the adjective vorseide ‘aforementioned’. Objects are also annotated as given if their referent can be inferred from previous discourse (elaborating inferables in Birner Reference Birner, Birner and Ward2006; Inferred in the Pentaset). This is illustrated in (5b), where zyn ambocht ‘his trade’ can be inferred from gildebrueder ‘guild brother’ mentioned earlier in the text, since members of a guild all practice the same trade. Finally, objects are annotated as given if they can be assumed to be familiar to the audience (Assumed in the Pentaset), i.e. if they represent encyclopedic or world knowledge, such as de brandende hel ‘the burning hell’ in (5c).Footnote 5

Objects that are newly introduced in the discourse are annotated as new. For example, the object Anthuenis Inffroot in (6a) is not mentioned before and is new to the discourse. When the object is linked to an antecedent, but the relationship does not inherently follow, the object is also annotated as new (bridging inferables in Birner Reference Birner, Birner and Ward2006). Basilica ‘basilica’ in (6b), for example, is linked to the preceding discourse by the adjective naastgelegen ‘adjacent’, which refers to a temple that has been mentioned before. However, the existence of a temple does not imply the existence of a basilica and, therefore, the object’s referent is new to the discourse.

In some cases, objects are non-referential, because they are abstract, quantified or negated, part of a fixed expression, or for some other reason do not refer to a real-world referent. These objects are annotated as inert and were discarded prior to statistical analysis. The category of Inert objects is diverse, and contains objects which may have different syntactic statuses. The object in (7) is Inert, because it is part of the fixed expression twist maken ‘argue’ (lit: ‘battle make’) and which may be a case of pseudo-incorporation (Booij Reference Booij2008). The Inert object in (8) is non-referential because it denotes a quantity and does not establish a specific discourse referent. Its syntactic status is different from the object from (7) in that it cannot (pseudo-)incorporate with the verb, but it is unclear whether the syntactic status of quantified objects is the same as that of referential objects. In Old English, quantified and negated objects behave differently from referential objects (Pintzuk & Taylor Reference Pintzuk, Taylor, Kemenade and Los2006), although they do operate within the same syntactic model independently of information status (Van der Wurff Reference Van der Wurff1997; Ingham Reference Ingham2007; Struik & Van Kemenade Reference Struik and van Kemenade2022).

Because of the heterogeneity of the Inert category, and its independence of information structure, we leave a more detailed investigation of these objects for future research.

Scrambling is annotated by documenting the position of the object relative to an adverbial in the middle field. We take adverbials as a diagnostic for scrambling in the broad sense of the word: we not only include adverbs, but any adjunct (such as DP adverbs and PPs). Adverbs and other (structurally more complex) adjuncts occupy the same position in the clause; they are both adjuncts to VP or some higher maximal projection. Including any adjunct as a diagnostic scrambling should therefore not make a difference on syntactic grounds. Objects which are not adjacent to the non-finite verb, but have an intervening adverbial are annotated as scrambled; objects that are preceded by an adverbial, but followed by another are also annotated as scrambled. Objects adjacent to the verb and preceded by an adverbial are annotated as unscrambled. In case no adverbial is present in the middle field, the sentence is recorded as ambiguous, since in those cases the surface order does not provide evidence for or against scrambling.

4. Results

This section discusses the results of our corpus study. Section 4.1 discusses the relation between information structure and OV/VO variation in historical Dutch; Section 4.2 discusses the relation between information structure and scrambling in historical Dutch. We discuss our findings and their implications in Section 4.3.

4.1 Information structure and OV/VO variation

We collected 2,245 analyzable subclauses with a finite verb, non-finite verb, and an object. Of these sentences, 1,419 contain a referential object. The distribution of new and given objects across OV and VO word orders per century is given in Table 2.

Table 2 Distribution of new and given objects across OV and VO word orders per century.

The data in Table 2 show a gradual reduction in the overall frequency of VO objects; in the thirteenth century 30.3% of the objects occur in VO order, which gradually reduces to 0.7% in the eighteenth century, and is lost altogether in the nineteenth century. However, the diachronic pattern is different for given and new objects. There is a consistent strong preference for given objects to occur in OV word order throughout the centuries. While given objects occur in VO order with some frequency in the thirteenth and fourteenth century, VO with given objects is very infrequent by the fifteenth century already. New objects occur in postverbal position at higher frequencies and for a longer period of time: although gradually declining, VO with new objects is productive until the sixteenth century, but its occurrence is reduced dramatically after that. Let us also note that in any given century, the postverbal position is more commonly occupied by new objects than by given objects, even though the overall number of new objects is much lower. These findings demonstrate that given objects are strongly associated with OV word order throughout the history of Dutch. New objects also surface in OV word order, but could also surface freely in VO order pre-sixteenth century.

To test the statistical validity of these observations we fitted a binary logistic regression within a generalized mixed model using the generalized linear mixed-effects model (glmer) function from the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (v4.0.3). We take word order (OV or VO) as the dependent variable, with VO as the reference category. The fixed factors included in the model are information status (given or new), length (of the object, measured as the logarithm of the number of letters), and the interaction between information status and century. The addition of the interaction term controls for the diachronic reduction of the VO order and for the reduction of the influence of the object’s information status. Before entering the variables into the model, we applied a non-linear transformation to the variable century by subtracting 13 from each data point, thereby anchoring the value 0 to the first century in our dataset. Furthermore, we centered the variable length around the mean. Information status was treatment coded (contrasts of 0, 1). We added varying intercepts for TextID (the specific text an item was extracted from) to the random structure of the model. This lets the model evaluate the effect of the fixed factors while taking into consideration the variation between individual texts.

We find significant main effects of length (β = −1.016; SE = 0.110; z = −9.251; p < 0.001) and information status (β = −2.224; SE = 0.287; z = −7.764; p < 0.001) on the surface word order. Shorter objects are more likely to be placed in preverbal position than longer objects, and given objects are placed in preverbal position more frequently than new objects. The coefficients of the two levels of information structure in interaction with the effect of century represent a significant rise in the use of preverbal objects as time progresses for both new objects (β = 0.822; SE = 0.102; z = 8.045; p < 0.001) and given objects (β = 0.664; SE = 0.104; z = 6.410; p < 0.001). Table 3 presents the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each of the fixed effects. These values represent the size of an effect and indicate whether the influence of a particular factor increases the odds of objects appearing in preverbal position (values below 1) or in postverbal position (values above 1).

Table 3 Odds ratios and confidence intervals of the fixed effects which explain the distribution of objects relative to the verb in our corpus data.

The odds ratio for length indicates that with each one unit increase in object length, the chances that this object appears in postverbal position are 2.76 times larger. The odds ratio for the variable information status indicates that new objects are 9.24 times more likely to appear in postverbal position than given objects. Notice that the odds ratios for the interactions between information structure and century are below 1, which confirms that the chances for given and new objects to appear in preverbal position increase over time. Figure 1 visualizes the effects of information structure and century on word order.

Figure 1 Objects in pre- and postverbal position per information status and century (error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals for the means).

4.2 Information structure and scrambling

In our dataset, 610 out of 1176 referential preverbal objects contain an adverbial which provides unambiguous evidence for scrambling. The data are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 Distribution of new and given objects across scrambled (OA) and unscrambled (AO) word orders per century.

The data in Table 4 show an overall reduction in the frequency of scrambling. In the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries around 80% of the objects scramble, but this number gradually decreases. However, the effect is stronger for new objects than for given objects. Given objects scramble at a consistent high rate throughout the history of Dutch. Scrambling with new objects is also frequent in the earlier centuries, but the overall number of new items in preverbal position is low as new objects frequently appear in VO order (see the previous section). New objects show a distinct preference for the unscrambled position from the sixteenth century onwards (i.e. after the postverbal position was lost). That is, as the overall number of new objects in preverbal position increases over time, the proportion of new objects in scrambled position reduces.

To test the statistical validity of these observations we fitted a binary logistic regression within a generalized mixed model using the glmer function from the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (v4.0.3), similar to the model presented in the previous subsection. Here, we take word order (scrambled or unscrambled) as the dependent variable, with the unscrambled order as the reference category. The fixed factors included are information status (given or new) and the interaction between information status and century. Adding the (log-transformed) variable length to the model did not result in a significant main effect on the outcome variable or in a significant improvement of the overall model (χ²(1) = 0.720, p = 0.396). We consequently excluded this variable for reasons of parsimony. Information status was treatment coded, and the same non-linear transformation was applied to century as in Section 4.1. We added varying intercepts for TextID to the random structure of the model.

We did not find a significant main effect of information status (β = −0.896; SE = 0.478; z = −1.875; p = 0.061), which indicates that there is no evidence for a difference between given and new objects in terms of their overall placement relative to the adverbial. The interaction effect between information status(given) and century did not reach significance (β = −0.115; SE = 0.067; z = −1.708; p = 0.088). Thus, the surface position of given objects in the Dutch middle field did not change significantly over time. We did find a significant interaction effect between information status(new) and century (β = −0.419; SE = 0.109; z = −3.841; p < 0.001), indicating that the scrambling behavior of new objects changes over time. The odds ratios can be found in Table 5. The odds ratio of the interaction between information status(new) and century is below 1 (0.658), which indicates that new objects become more likely to surface in unscrambled position as the centuries pass. The effect of information status and century on word order is visualized in Figure 2.

Table 5 Odds ratios and confidence intervals of the fixed effects which explain the distribution of objects relative to the adverbial in our corpus data.

Figure 2 Objects in unscrambled and scrambled position per information status and century (error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals for the means).

4.3 Discussion

The results presented in Sections 4.1 and 4.2 demonstrate that object placement in Dutch has relied heavily on information structure throughout the history of the language. However, the locus of variation seems to change over time. The position of new objects plays a key role in this observation.

When VO was a productive word order in the language, the alternation with OV was (at least partially) governed by information structure. Given objects show a strong preference for the preverbal position throughout the entire period. New objects, in contrast, show a preference for the postverbal position – until this position is lost after the sixteenth century, after a period of gradual reduction. At this point, the verb can no longer function as the boundary between information structural domains, since new objects must now appear preverbally as well. The option to place preverbal objects before or after the adverbial (scrambling) already existed in the early stages of Dutch. Our corpus data indicate that the scrambled position was the preferred object position in pre-fifteenth century Dutch, regardless of information status (although the overall number of preverbal new objects was relatively small in this period). As the frequency of VO reduces, new objects increasingly surface in unscrambled position. This shift is visualized in Figure 3, which demonstrates the development of objects in terms of OV/VO variation and scrambling, based on the frequencies and percentages from Table 2 and Table 4 for new and given objects, respectively. Given objects show a consistent preference for the preverbal, scrambled position. However, as new objects start to occur in preverbal position more frequently (OV), they start to occur in scrambled position less frequently (scrambling). This suggests that there is a relation between the loss of VO and the emergence of scrambling as an information structurally meaningful operation.

Figure 3 Development of new and given objects in terms of scrambling and OV/VO variation.

In the next section, we propose a syntactic analysis of the variation in object placement in the history of Dutch, which allows for a natural transition from one locus of variation (the verb) to another (the adverb). We show that this can be achieved in an antisymmetric model in which information structure is not directly encoded but follows from interface conditions.

5. An analysis of (historical) Dutch object placement

The previous section has shown that OV/VO variation in historical Dutch and scrambling in present-day Dutch have a similar function and seem to be diachronically related; both variations mark the information status of direct objects. Given objects are consistently preverbal throughout the history of Dutch and scramble at a high rate. The surface position of new objects, however, gradually shifts from a (largely) postverbal position to a preverbal position to the right of an adverbial (i.e. unscrambled position). A syntactic analysis of object placement should therefore not only comprise a synchronic analysis of OV/VO variation and scrambling; it should also bring out the diachronic relatedness between the two phenomena. We propose that an antisymmetric account with object movement from a postverbal base position, building on Broekhuis (Reference Broekhuis2008), and with multiple spell out options, accounts for the facts presented in the previous section.

5.1 An antisymmetric account of object placement

We present an account of scrambling in present-day Dutch that involves movement of the object (following Vanden Wyngaerd Reference Vanden Wyngaerd1989; Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer2000; Broekhuis Reference Broekhuis2008) and we generally follow the analysis presented in Broekhuis (Reference Broekhuis2008).Footnote 6 Broekhuis adopts Kayne’s (Reference Kayne1994) theory of antisymmetry, which claims that linguistic structure universally follows the same specifier–head–complement order. Under this view, the underlying structure of Dutch is VO. OV surface order in complex main clauses and subclauses results from leftward object movement motivated by structural factors.

Crucial to Broekhuis’s (Reference Broekhuis2008) antisymmetric analysis is that scrambling is not a single movement, but a process that involves two movement steps (see Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer2000 for a similar analysis). Consider the clause structure in (9), adapted from Broekhuis (Reference Broekhuis2008: 61).

The base position of objects is postverbal (OBJ1), but they must move into a specifier position in the extended projection of the verb to check the phi-features on V (cf. AgrP in Pollock Reference Pollock1989; Grimshaw Reference Grimshaw1997); that is, objects must move from OBJ1 to OBJ2. Objects can move further into the extended projection of v (i.e. from OBJ2 to OBJ3).

Broekhuis (Reference Broekhuis2008) argues that this last movement step is related to case. He supports this assumption with the observation that complement PP objects, unlike DP objects, cannot scramble over PP adverbials (cf. Vikner Reference Vikner, Corver and van Riemsdijk1994, Reference Vikner, Everaert and van Riemsdijk2006). This is illustrated in (10). Since DPs, but not PPs, are subject to the Case Filter (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1981), case is a likely trigger for scrambling.

However, the assumption that case is a formal syntactic feature is questioned in recent (minimalist) literature and it has been suggested that the (morphological) expression of case is merely a ‘by-product’ of agreement of phi-features (see Bobaljik & Wurmbrand Reference Bobaljik, Wurmbrand, Malchukov and Spencer2008; Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson2012; Polinsky & Preminger Reference Polinsky, Preminger, Carnie, Siddiqi and Sato2014; Preminger, in press, and sources cited there for arguments and discussion). This questions the assumption that case is the trigger for object movement to v, and we leave open the possibility that it is a more general agreement feature that attracts the object. The crucial point here is that the object is licensed by formal syntactic operations in two steps, which, as we will argue below, yield several potential spell out positions.

As the object moves to a higher position in the clause, it may cross predicate adverbs adjoined to VP and clause adverbs adjoined to vP (VP- and S-adverbs in Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972).Footnote 7 We follow Broekhuis’s (Reference Broekhuis2008) assumption that merger of the adverb and movement of the object is essentially free (as far as the syntax is concerned),Footnote 8 because the required modification does not depend on a particular position of the adverb within the extended projection of the modified phrase. The object moves before an adverb is adjoined to VP or vP (depending on its type), leading to ADV–OBJ order, or the adverb is adjoined before the object moves, leading to OBJ–ADV order. This optionality is illustrated in (11) for adverbs adjoined to VP and (12) for adverbs adjoined to vP, which are both simplified versions of the structures in Broekhuis (Reference Broekhuis and van Craenenbroeck2011: 21).

A crucial difference between the movement steps from OBJ1 to OBJ2 and from OBJ2 to OBJ3 in Broekhuis (Reference Broekhuis2008) is that the latter syntactically optional, regulated by information structure.Footnote 9 The rationale behind this assumption is the claim that (prosodically unmarked) new information foci must appear in the rightmost position of the clause (cf. Cinque Reference Cinque1993; see also Neeleman & Reinhart Reference Neeleman, Reinhart, Butt and Geuder1998). Broekhuis proposes that, in Dutch, this interface constraint is ranked higher than the economy constraint EPP (case), i.e. the requirement to check case on v locally. New objects consequently do not have to move to check case features on v; these features are instead checked at a distance under an Agree relation (Chomsky Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels, Uriagereka and Keyser2000). Thus, object movement from OBJ2 to OBJ3 is blocked for new objects, and only given objects are predicted to appear in OBJ3.

Our analysis is in many ways compatible with the general proposal in Broekhuis (Reference Broekhuis2008), but we do not rely on OT constraints and hence two different ways of checking case to derive the surface variation. We take movement as an operation that copies and pastes elements in the syntactic structure, following the copy theory of movement (see Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995; Nunes Reference Nunes2004). The copy theory of movement claims that copies of displaced elements are not removed from the derivation, but remain available, thereby allowing for flexibility in their spell out positions. For Dutch clauses, this means the object is generated in OBJ1 and obligatorily moves via OBJ2 to OBJ3, leaving behind copies in each intermediate position.

The position in which the object is spelled out is governed by an interplay of interface conditions (similar to Broekhuis’s LF and PF constraints). Assuming that these conditions are independent of obligatory syntactic operations allows us to also integrate the various (discourse-)semantic and prosodic factors that have been argued to play a role in scrambling and OV/VO variation. These factors together determine which of the object positions made available by the syntax are felicitous in a particular context, which may in fact be more than one. Information structure exploits the available positions to express discourse relations, and is hence not a cue for differential movement, but for differential pronunciation (see also Haider Reference Haider2020).

Our analysis is also in line with Struckmeier’s (Reference Struckmeier2017: 21) ‘subtractive grammatical architecture’. Struckmeier argues that the semantic interface determines which structures are semantically interpretable and subtracts any structure that does not adhere to the semantic requirements of a language. He shows for German that scrambling has clear semantic effects in some cases, but not in others. The same facts hold for Dutch: scrambling feeds binding (Vanden Wyngaerd Reference Vanden Wyngaerd1989; Neeleman Reference Neeleman, Corver and van Riemsdijk1994), see (13), and ‘triggers all possible strong readings’ (De Hoop Reference De Hoop1996: 51) in terms of referentiality, partitivity, and genericity. For instance, scrambling of indefinites yields interpretive effects related to specificity of the object (see Unsworth Reference Unsworth2005: 63–66), see (14). These effects are absent if the object is a definite DP (see Van der Does & De Hoop Reference Van der Does and de Hoop1998).Footnote 10

Struckmeier (Reference Struckmeier2017) argues that such semantic effects are expected to occur after movement, on the assumption that (optional) movement must have an effect on the outcome (Chomsky Reference Chomsky2001). The word order changes yield new binding options or interpretations, thereby directly fulfilling the effect-on-the-output condition.Footnote 11 Struckmeier argues that the moved elements do not need to have a designated target location; rather, the relational output configuration of the elements is evaluated. He proposes that, since German and Dutch are scope-rigid (or scope-transparent) languages in which scope relations are computed according to surface order, objects are interpreted in the position in which they are spelled out. The semantic interface rules out any order which results in a position-meaning mismatch.

The phonetics interface similarly determines which structures are phonologically well formed (potentially obscuring semantic transparency) and further restricts word order options. For instance, low spell out of prosodically unmarked pronouns is ruled out (cf. (3), repeated here as (15), cf. Bouma & De Hoop Reference Bouma and de Hoop2008).

The syntax thus makes various spell out positions for the object available, which are subjected to conditions at the semantics and phonetics interfaces. Speakers may have preferences for particular spell out options (out of the remaining felicitous candidates), based on, we argue, pragmatic principles such as given-before-new or short-before-long (Wasow Reference Wasow1997). Our conception of the pragmatic interface is that the principles at play are violable; pragmatic constraints are ‘soft’ (see Keller Reference Keller2000). That is, they are not as strict as those imposed by syntax, semantics, or phonology. Thus, scrambling is influenced, but not determined, by information structural preferences (cf. Schoenmakers et al. Reference Schoenmakers, Poortvliet and Schaeffer2021).

Adopting the copy theory of movement permits a uniform analysis of OV/VO variation in historical Dutch and scrambling in present-day Dutch, and allows for a natural transition from a clause structure with the verb as the boundary between information structural domains to a clause structure in which the adverb serves this function in the middle field. When we relate the object positions outlined in this section to the results presented in Section 4, we arrive at the schematic representation of spell out positions and information structural domains in (16).Footnote 12

We showed that objects in postverbal position were typically new to the discourse (or heavy) in historical Dutch, but that there are no clear indications of an information structural constraint on scrambling. Rather, the scrambled position (OBJ3) is preferred for all objects in the middle field, regardless of their information status (although the number of preverbal new objects is low). The most important spell out positions in historical Dutch are therefore OBJ3 and OBJ1. While OBJ2 is also available as a syntactic and hence spell out position, it does not seem to serve an independent information structural function. The verb thus marks the boundary between the domains in which given and new information is expressed in historical Dutch. The postverbal object position (OBJ1) became increasingly restricted as a spell out position, until it was lost as a regular position for objects in the sixteenth century. As a result, the verb no longer separates the domains in which given and new information is expressed. This is when the middle field starts to show a division between information structural domains, with OBJ3 for given objects and OBJ2 for new objects, and the boundary between these domains shifts to the adverbial.

5.2 Shifting the border between information structural domains

One question that we have not addressed thus far is why VO was lost, and how the middle field became the locus of information structure encoding. The data presented in Section 4 indicate that the loss of VO and the establishment of an information structurally functional middle field proceed in tandem. While the number of VO structures with new objects declines, scrambling becomes sensitive to information structure. This leads to the question whether VO order was reduced and the middle field became the locus of variation as a consequence, or whether word order in the middle field became information structurally motivated first and VO was lost as a result. If our analysis is on the right track, the loss of VO likely prompted the establishment of the middle field as the locus of information structure encoding. It is not clear from the literature what triggered the loss of VO, but it seems unlikely that this is the result of a single factor. It is more likely that VO was lost as the result of a series of internal and external changes. As a full-fledged multifactorial analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, we here present a broad-brush sketch of the factors that may have played a role in the loss of VO and how this may have resulted in an information structurally motivated middle field.

One way of formalizing this idea is by using the parametric hierarchies approach outlined in Roberts (Reference Roberts2019), which divides linguistic variation into various levels. The highest level of linguistic variable is the Macroparameter. Macroparameters are (a) typologically pervasive; for example, all languages have to determine in which order the verb and object may appear, (b) salient in the primary linguistic data (PLD), i.e. linearization of the object and verb takes place in many of the utterances an acquirer is exposed to, and (c) diachronically stable. The lower-level meso- or microparameters, however, are (a) typologically parochial, i.e. they may be language specific, (b) not pervasive in the PLD, and (c) diachronically unstable.Footnote 13 Changes at the macroparametric level are possible, but this is usually the effect of (profound) changes in (a combination of) lower-level microparameters to the point that a language acquirer no longer receives enough input to acquire the old variant (see Westergaard Reference Westergaard, Ferraresi and Lühr2010 for a similar idea).

Historical Dutch underwent several lower-level syntactic changes which may have played a role in the loss of VO. First of all, loss of inflection in general and, more specifically, the loss of overt morphological case marking on nouns (with the exception of pronouns and genitive -s) reduces the possibility to infer the relation between constituents from morphology, which may have prompted a more rigid word order (see Weerman Reference Weerman, Beukema and Coopmans1987, Reference Weerman1989). That this cannot be the single reason for the loss of VO becomes evident when Dutch is compared to German. German also lost VO word order, but retains its case system. A second factor that may have played a role in the loss of OV/VO variation in Dutch is the grammaticalization of the definite determiner. Proto-Germanic did not have a determiner (Lehmann Reference Lehmann, König and van der Auwera1994). As in Old English and Old High German, the emergence of the determiner as a grammatical category was an Old Dutch innovation, but this was not yet fully consolidated by Middle Dutch (Van de Velde Reference Van de Velde2010). Changes in the determiner system of a language also imply changes in the reference system (see Piotrowska & Skrzypek Reference Piotrowska and Skrzypek2021 for the diachronic relation between definiteness marking and referentiality in North Germanic). This, in turn, may have consequences for other means of expressing information structure, such as word order.

The analysis that we propose, in which the object is licensed in two movement steps resulting in three spell out positions, may also be relevant for the loss of VO. We argue that object movement to the highest object position in Spec,vP is obligatory and that this is also the default position where given objects are spelled out. New objects, however, are by default (but not necessarily) spelled out in the lowest object position, i.e. VO position. Because object movement proceeds in two steps, the intermediate object position in Spec,VP does not have a clear pragmatic or semantic function, as in (16). The loss of VO may be motivated, in combination with other microparametric changes such as those outlined above, by internal pressure to reduce redundancy and a need for a more parsimonious syntactic system. The reason why Dutch (and also German) converged on OV word order and not VO may lie in the functionally motivated status of VO: only new and heavy objects appear freely in VO word order, but new and heavy objects also appear in OV order. Given objects, however, strongly prefer OV. A scenario in which a language converges on VO after a period of mixed OV/VO is equally likely: this is the case in English. However, a crucial difference between Dutch and English is that OV is information structurally marked in Old and Early Middle English, while Dutch and English are similar in that both developed a definite article and both lost (most of) their case marking (Struik & Van Kemenade Reference Struik and van Kemenade2022).

Another factor that should be taken into consideration is the frequency of VO in everyday language use, especially directed to language acquirers. One may wonder how frequent VO orders are in the input of an acquirer of pre-1700 historical Dutch. Our data set suggests a very strong genre effect: while VO structures occur in all text genres and contexts, they are most frequent in official documents detailing transactions (see also Blom Reference Blom, Broekhuis and Fikkert2002), as illustrated in (17).

The grammatical object in such constructions is frequently the object of a transaction, either physically or monetarily. Approximately half of the referential VO objects in our sample are transactions. This is a very specific use, which presumably did not occur frequently in child-directed speech, nor would it have been part of everyday conversation. Note, however, that while these transactions might inflate the number of VO in historical Dutch, we find new objects in non-transaction readings as well, as in (18).

The occurrence of VO structures cannot be attributed to a genre effect alone, but the relatively low input frequency of non-formulaic VO structures, the microparametric changes that were taking place around the same time, the obligatory feature-checking in preverbal position, combined with the internal pressure of the language to reduce the redundant optionality in spell out positions may have caused acquirers to disfavor the postverbal object position (see Westergaard Reference Westergaard, Ferraresi and Lühr2010). As a result, the grammar of the language changed: the postverbal spell out position is lost over time. The loss of this position entails that the verb can no longer mark the boundary between the given and new domains; however, the middle field is already equipped with elements which might take up the task: adverbials.

An adverbial, however, is not the ideal boundary between the given and new domain, because it is an optional element. Adverbials will not always be present to demarcate the given and new domain. Moreover, there is a distinction between (at least) predicate and clause adverbials (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972; see also Cinque Reference Cinque1999), which may lead to variation in (or confusion about) the position of the information structure boundary. The verb, by contrast, is a clear boundary: it is obligatory and occupies a fixed position in the clause (in non-V2 contexts). The boundary shift does not appear to be an efficient one from an information structural point of view. This suggests that the syntactic triggers responsible for movement are stronger than the need for clearly demarcated information structural domains. This is in line with the idea that information structure piggy-backs on the structure that is made available by the syntax (see also Haider Reference Haider2020). Syntax forces objects to move from the postverbal domain and pragmatics will have to make do with the positions that remain available for spell out.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to bring together two types of word order variation in two stages of Dutch for which no relation had been previously assumed: OV/VO variation in historical Dutch and scrambling in present-day Dutch. We tested the hypothesis that both types of word order variation are functionally similar, i.e. they differentiate the information structural domains of given and new information. This was confirmed by our corpus data, which showed that the distribution is similar for OV/VO variation and scrambling: given objects tend to appear in earlier positions than new objects. In fact, the placement of given objects is rather consistent throughout the history of Dutch. They occur in preverbal and scrambled position at high frequencies between the thirteenth and nineteenth century. The position of new objects shifts from the postverbal to preverbal, unscrambled position, which suggests that the two types of variation are diachronically related.

We analyzed the diachrony of object placement as movement from a uniformly head-initial base via the specifier of VP to the specifier of vP. Historical Dutch allows spell out of the object in its postverbal base position, but this position was lost after the sixteenth century, which we argued is due to a composite of factors which together resulted in the loss of VO. Scrambling in the middle field was always a part of Dutch syntax, but in the earlier stages of the language it did not have an independent function in terms of information structure. The loss of VO entails the loss of the expression of discourse relations and, as a consequence, information structure ‘exploits’ syntax to find a new way to distinguish between given and new information. Thus, the boundary between the given and new domains shifts from the verb to the adverbial in the middle field.

Appendix. Overview of source material

Our source material contains texts from the following corpora:

-

• Corpus Gysseling (Reference Gysseling2021)

The online Corpus Gysseling contains thirteenth century official documents, originally collected by Ghent linguist Martin Gysseling between 1977 and 1987, and is enriched with part of speech tagging and lemmatization. We included a selection of texts from the regions Flanders, Utrecht, and Holland.

Total number of texts in subset: 336

Total words in subset: 278,038.

-

• Corpus Van Reenen–Mulder (CRM14) (Van Reenen & Mulder Reference Van Reenen and Mulder1993)

The CRM is a collection of fourteenth century official documents. The CRM contains over 3,800 documents which are all dated and localized. We included a random selection of texts from the regions of Flanders, Utrecht, and Holland.

Total number of texts in subset: 91

Total words in subset: 54,460

-

• Corpus Laatmiddel- en Vroegnieuwnederlands (CLVN) (Van der Sijs et al. Reference Van der Sijs, van Kemenade and Rem2018)

The CLVN contains over 2,700 official documents from the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The texts in this corpus frequently comprise several charters and hence appear longer in length than the texts from Gysseling or CRM. We included a random selection of texts from the regions of Flanders, Utrecht, and Holland. There is one exception; the corpus contains the diary of Christiaan Munsters, but this text is not localized. We included it to balance the predominantly official nature of the dataset.

Total number of texts in subset: 66

Total words in subset: 176,543

-

• Narrative section of the Compilatiecorpus Historisch Nederlands (CHN) (Coussé Reference Coussé2010)

The narrative subcorpus of the CHN contains a balanced selection of narrative prose texts written from the end of the sixteenth century onwards. The texts included in this subcorpus are all written in Holland.

Total number of texts in subset: 63

Total words in subset: 106,274

We used material from three religious primary sources to supplement the official documents included in the corpora mentioned above:

-

• Sermon 1, 20, 39, 41, and 42 of De Limburgsche Sermoenen (Kern Reference Kern1895). The Limgbursche Sermoenen are the oldest recorded sermons in the Dutch language and were written in the thirteenth century. They originate in the southeast of the Netherlands, but they were added to the text selection to balance the official treatises from Corpus Gysseling.

Total words in subset: 15,408

-

• Translations of the first 18 Psalms (Bruin Reference Bruin and Bruin1978). The Psalms were translated at the end of the fourteenth century. The author is unknown, so the text is not localized.

Total words in subset: 5,009

-

• Den Tempel Onser Sielen (Ampe Reference Ampe1968) and Der Evangelische Peerle (Ampe Reference Ampe1993) both written by the same beguine in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Total words in subset: 10,558

Total number of words in our dataset: 702,519. An overview of the distribution of material across time and region is given in Table A1.

Table A1 Distribution of source material across time and region.