Introduction

Sleep problems, such as short or long sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and daytime sleepiness, are common globally. A study of 50 countries reported that one in four adults do not sleep well (Soldatos, Allaert, Ohta, & Dikeos, Reference Soldatos, Allaert, Ohta and Dikeos2005). Among older adults, it is estimated that disruptions in sleep quality or sleep duration affect over half of this age group (Crowley, Reference Crowley2011; Neikrug & Ancoli-Israel, Reference Neikrug and Ancoli-Israel2010; Stranges, Tigbe, Gómez-Olivé, Thorogood, & Kandala, Reference Stranges, Tigbe, Gómez-Olivé, Thorogood and Kandala2012; Unruh et al., Reference Unruh, Redline, An, Buysse, Nieto and Yeh2008). In Canada, estimates range from one in three to as many as one in two adults reporting fewer hours of sleep than the recommended 7 hour minimum (Chaput, Wong, & Michaud, Reference Chaput, Wong and Michaud2017; Gilmour et al., Reference Gilmour, Stranges, Kaplan, Feeny, McFarland and Huguet2013; Nunez, Nunes, Khan, Stranges, & Wilk, Reference Nunez, Nunes, Khan, Stranges and Wilk2021; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019). Insomnia symptoms are also highly prevalent in Canadians, experienced by approximately one in four adults, with the prevalence increasing over a 10-year period (Chaput, Yau, Rao, & Morin, Reference Chaput, Yau, Rao and Morin2018; Garland et al., Reference Garland, Rowe, Repa, Fowler, Zhou and Grandner2018; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019). Indeed, more recent Canadian data indicate that 55 per cent of adult females and 41 per cent of adult males experience insomnia symptoms (Nunez et al., Reference Nunez, Nunes, Khan, Stranges and Wilk2021). Insomnia symptoms have been associated with middle-age in particular, with a higher prevalence in 40–59-year-olds than in 18–29-year-olds (Morin et al., Reference Morin, LeBlanc, Bélanger, Ivers, Mérette and Savard2011). Given the high prevalence of sleep problems among adults and older adults in Canada, understanding the potential health impacts of sleep problems is important for informing public health policy and clinical interventions.

In the context of an aging population, sleep problems have also been associated with poor well-being in middle-aged and older adults, in studies from low-resource settings (Stranges et al., Reference Stranges, Tigbe, Gómez-Olivé, Thorogood and Kandala2012), China (Zhi et al., Reference Zhi, Sun, Li, Wang, Cai and Li2016), the United States (Lemola, Ledermann, & Friedman, Reference Lemola, Ledermann and Friedman2013), and Europe (Faubel, Lopez-Garcia, Guallar-Castillón, Balboa-Castillo, & Gutiérrez-Fisac, Reference Faubel, Lopez-Garcia, Guallar-Castillón, Balboa-Castillo and Gutiérrez-Fisac2009; Lukaschek, Vanajan, Johar, Weiland, & Ladwig, Reference Lukaschek, Vanajan, Johar, Weiland and Ladwig2017). However, there is limited Canadian evidence, and measures of well-being are likely to differ across populations; therefore, it is important to assess these associations in different settings (Lindert, Bain, Kubzansky, & Stein, Reference Lindert, Bain, Kubzansky and Stein2015). Also, evidence suggests that country is an important moderator of the association between sleep quality and depression, anxiety, and stress (João, de Jesus, Carmo, & Pinto, Reference João, de Jesus, Carmo and Pinto2018). Recent Canadian evidence from an adult sample suggests significant associations between abnormal sleep duration and insomnia symptoms, and poor psychological well-being (Dai, Mei, An, Lu, & Wu, Reference Dai, Mei, An, Lu and Wu2020). Insomnia in Canadian adults has also been significantly associated with poor mental health, psychological problems, and anxiety symptoms (Morin et al., Reference Morin, LeBlanc, Bélanger, Ivers, Mérette and Savard2011). Notably, prior Canadian studies have primarily focused on sleep duration and insomnia symptoms and have neglected other facets of sleep, such as sleep dissatisfaction and the impact of sleep problems on daytime functioning. Furthermore, there is evidence of variation in associations across age groups. Short sleep duration has been found to be associated with higher odds of poor/fair self-reported mental health in Canadian adults (18–64 years), but not older adults (65 years and older; Chang, Chaput, Roberts, Jayaraman, & Do, Reference Chang, Chaput, Roberts, Jayaraman and Do2018). An in-depth understanding of the association between sleep problems and psychological well-being across middle-aged and older Canadian adults is warranted to better understand the public health implications of poor sleep on well-being across the lifespan.

There is limited evidence examining sex-modified associations between sleep problems and psychological well-being; however, associations between sleep problems and physical health outcomes have been shown to vary by sex, with a stronger magnitude of effect in women. For example, short sleep duration has been associated with a higher risk of metabolic syndrome and hypertension in women than in men (Cappuccio et al., Reference Cappuccio, Stranges, Kandala, Miller, Taggart and Kumari2007; Smiley, King, & Bidulescu, Reference Smiley, King and Bidulescu2019; Stang, Moebus, Möhlenkamp, Erbel, & Jöckel, Reference Stang, Moebus, Möhlenkamp, Erbel and Jöckel2008; Stranges et al., Reference Stranges, Dorn, Cappuccio, Donahue, Rafalson and Hovey2010). As well, sleep problems have been associated with more detrimental effects of cardiovascular risk among women (Meisinger, Heier, Löwel, Schneider, & Döring, Reference Meisinger, Heier, Löwel, Schneider and Döring2007). In terms of psychological well-being, Chang et al. did not observe an interaction by sex in the association between self-perceived mental health and short or long sleep duration among Canadian adults. Further exploration of sex differences across different domains of sleep patterns and additional measures of psychological well-being are needed to better understand sex-specific associations and to identify subgroups of people more impacted by sleep problems.

The aim of this study was to explore the association between sleep problems (sleep duration, sleep dissatisfaction, insomnia symptoms, and daytime impairment from insomnia symptoms), and psychological well-being (life satisfaction, psychological distress, self-reported mental health) among middle-aged and older adults in Canada. Effect modification by sex and age group was also explored. It was hypothesized that sleep problems would be associated with poorer psychological well-being, and that these associations would vary by sex and age group.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Study Design

This study involved a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) Comprehensive Cohort, a study of community-dwelling adults across Canada (Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 2017; Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Oremus and Patterson2009, 2019). The CLSA Comprehensive Cohort is a national stratified sample of 30,097 adults 45–85 years of age at recruitment who were able to read and speak French or English (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Balion and Cossette2019). People living in long-term care institutions, with cognitive impairment, living in the three territories or First Nations reserves, and full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces were excluded (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Oremus and Patterson2009). Participants were interviewed in person to enable detailed data collection, including physical and clinical measures; therefore, participants were randomly selected from within 25–50 km of one of 11 data collection sites located in major academic centres in seven provinces (British Colombia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland; Raina, Wolfson, & Kirkland, Reference Raina, Wolfson and Kirkland2008; Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Oremus and Patterson2009). Provincial health care registration databases and random digit dialling were used as sampling frames (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Oremus and Patterson2009). Participants provided written informed consent. Baseline data collection was conducted from 2012 to 2015. Approval to access the data was obtained from the CLSA (Application Number: 180113), and ethics approval was obtained.

Measurements

Sleep problems

Sleep questions in the CLSA were adapted from validated measures (Bastien, Vallières, & Morin, Reference Bastien, Vallières and Morin2001; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, Reference Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman and Kupfer1989). Sleep duration was assessed with the question: “During the past month, on average, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night? (This may be different than the number of hours you spend in bed.)” Answers were categorized as short (< 6 hours), normal (6–8 hours), and long sleep duration (> 8 hours). Although 7 hours is the recommended minimum for all adults, the National Sleep Foundation further rated the appropriateness of different cut-offs as they relate to health outcomes (Hirshkowitz et al., Reference Hirshkowitz, Whiton, Albert, Alessi, Bruni and DonCarlos2015). A short duration cut-off of < 6 hours was selected, as this cut-off was considered “not appropriate” and “may be appropriate in some individuals” in adults and older adults, respectively (Hirshkowitz et al., Reference Hirshkowitz, Whiton, Albert, Alessi, Bruni and DonCarlos2015), and to align with prior studies showing the health effects of habitual sleep duration, including a prior CLSA study (Ayas et al., Reference Ayas, White, Manson, Stampfer, Speizer and Malhotra2003; Cappuccio et al., Reference Cappuccio, Stranges, Kandala, Miller, Taggart and Kumari2007; Kripke, Garfinkel, Wingard, Klauber, & Marler, Reference Kripke, Garfinkel, Wingard, Klauber and Marler2002; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Rodrigues, Anderson, Wilk, Guaiana and Stranges2020; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Ayas, Malhotra, White, Schernhammer and Speizer2004; Stranges et al., Reference Stranges, Dorn, Shipley, Kandala, Trevisan and Miller2008). The long duration cut-off was selected based on the distribution of sleep duration within the CLSA sample, as only a small number of participants reported sleeping longer than 8 hours (5%). Subjective sleep dissatisfaction was examined using the question: “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your current sleep pattern?” Answers were dichotomized to satisfied/neutral (combining answers of very satisfied, satisfied, or neutral), and dissatisfied (combining answers of very dissatisfied or dissatisfied), consistent with a prior CLSA study (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Rodrigues, Anderson, Wilk, Guaiana and Stranges2020). Insomnia symptoms were identified using the questions “Over the last month, how often did it take you more than 30 minutes to fall asleep?” and “Over the last month, how often did you wake in the middle of the night or too early in the morning and found it difficult to fall asleep again?” Insomnia symptoms were defined as having problems with initiating or maintaining sleep three times a week or more. Finally, problems with daytime functioning as a result of insomnia symptoms were examined using the questions: “To what extent do you consider your problem falling asleep to interfere with your daily functioning (for example, from daytime fatigue, ability to function at work/daily chores, concentration, memory, mood, etc.)?” and “To what extent do you consider your problem staying asleep to interfere with your daily functioning (for example, from daytime fatigue, ability to function at work/daily chores, concentration, memory, mood, etc.)?” Answers of “somewhat”, “much”, and “very much” to either question were defined as having problems with daily functioning versus answers of “a little” and “not at all”.

Psychological well-being

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used, a five-item instrument rated on a seven-point scale (Diener, Emmons, & Griffin, Reference Diener, Emmons and Griffin1985). For example, for the item “I am satisfied with my life,” respondents select answers from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Scores for each item are summed to provide an overall score ranging from 5 to 35, with higher scores indicating more satisfaction. A cut-off score of 15 or less was used, indicating dissatisfaction with life (Diener, Reference Diener2006). Psychological distress was also examined, measured by the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Barker, Colpe, Epstein, Gfroerer and Hiripi2003). The K10 is a 10-item questionnaire about nonspecific psychological distress experienced in the past 30 days (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Barker, Colpe, Epstein, Gfroerer and Hiripi2003). Responses for each item use a five-point scale and are summed to provide an overall score ranging from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating more psychological distress. A cut-off score of 15 or higher was selected to indicate clinically significant psychological distress, which was found to be associated with the best balance of sensitivity (0.77) and specificity (0.78) in predicting depression/anxiety in older adults (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Sunderland, Andrews, Titov, Dear and Sachdev2013). Subjective mental health was assessed with the question: “In general, would you say your mental health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Answers were dichotomized to fair or poor versus good, very good, or excellent, consistent with prior studies (Atkins, Naismith, Luscombe, & Hickie, Reference Atkins, Naismith, Luscombe and Hickie2013; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Mei, An, Lu and Wu2020; Magee, Caputi, & Iverson, Reference Magee, Caputi and Iverson2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wu, Ungvari, Ng, Forester and Gatchel2017).

Covariates

Socio-demographic, lifestyle, and clinical factors included in the analysis were selected a priori. Socio-demographic factors included age group, sex (male or female), self-reported ethnicity (white vs. ethnic minority group), rural or urban residence, annual household income (< $20,000, $20,000–49,999, $50,000–99,999, $100,000–149,000, ≥ $150,000), employment status (retired, employed full-time, employed part-time, or unemployed), education (less than secondary, secondary, some post-secondary, post-secondary degree/diploma), and marital status (single/never married, married/common-law, widowed/divorced). For lifestyle factors, frequency of alcohol consumption in the past year was examined (lifelong abstainer, former drinker [no alcohol in the past year], infrequent drinker [drank less than once a month], occasional drinker [drank about once a month to once a week], regular drinker [drank 2–3 times a week to almost every day], and binge drinker [more than 4–5 drinks per sitting at least 2–3 times per month]). Smoking status was categorized as daily smoker, occasional smoker, former smoker, or never smoker. The Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey was used, a 19-item scale consisting of items for emotional support, instrumental assistance, information, guidance and feedback, personal appraisal support, and companionship (Sherbourne & Stewart, Reference Sherbourne and Stewart1991). The overall score is obtained by averaging responses over each item and transforming scores to range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support. A binary variable for whether participants had provided caregiving assistance in the past year was also included. Frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption was measured using the Short Diet Questionnaire (SDQ; Shatenstein & Payette, Reference Shatenstein and Payette2015), which measured the average number of times per day fruit and vegetables were consumed in the past 12 months. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) assessed past-week frequency, duration, and intensity of various forms of physical activity (Washburn, Smith, Jette, & Janney, Reference Washburn, Smith, Jette and Janney1993). The overall scores range from 0 to 793, with higher scores indicating a higher level of physical activity. To control for clinical factors, the number of self-reported chronic conditions from a list of 42 physical conditions was counted, including respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, gastrointestinal and rheumatic conditions, cancer, diabetes, allergies, acute infections (past year), and vision-related and psychiatric conditions. A complete list of conditions is available in the online supplement (Table S1). Pain was accounted for using the question “Are you usually free of pain or discomfort?” with answers of “no” indicating pain/discomfort.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted with sampling weights to account for the cluster and strata sampling design (Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 2017). Modified Poisson regression models with robust variance estimators (Zou, Reference Zou2004) and analytic sampling weights (Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 2017) were used to estimate prevalence ratios (PR) and 95 per cent confidence intervals (CI) for the prevalence of sleep problems (short/long sleep duration, dissatisfaction with sleep, insomnia symptoms, and daytime impairment) among participants with each well-being outcome (dissatisfaction with life, psychological distress, poor self-reported mental health). Unadjusted PRs and PRs adjusted for the socio-demographic, lifestyle, and clinical covariates selected a priori were estimated.

Effect modification by sex was examined by estimating stratified PRs and 95 per cent CIs for sleep problems within each well-being outcome among males and females in fully adjusted models. The ratio of male/female subgroup PRs and the associated 95 per cent CI was calculated to determine whether there were significant sex differences. For effect modification by age, age was analyzed as a continuous variable, so an interaction term for sleep problems × age was added to the fully adjusted models and the difference in effects over 10 years was calculated. Effects at specific ages were also estimated, in which PRs and 95 per cent CIs at age 45, 55, 65, 75, and 85 were calculated.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted in which participants with suspected clinical sleep disorders (sleep apnea, insomnia, and rapid eye movement-sleep behavior disorder) were removed to ascertain whether observed associations between sleep and psychological well-being were being driven by participants with clinical sleep disorders (methods described in the online supplement, Appendix S1).

Percentage of missing data ranged from 0 per cent to 9 per cent across all variables, and the case-wise proportion of missingness was up to 27 per cent. Missing data were imputed and analyzed using 25 multiply imputed data sets using chained equations. All sleep variables, socio-demographic, lifestyle, and clinical factors were used in the imputation model. The parameters in each model were estimated in each imputed data set separately and combined using Rubin’s rules (Rubin, Reference Rubin1987). All analyses were conducted in Stata/IC, version 16.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

CLSA Participants

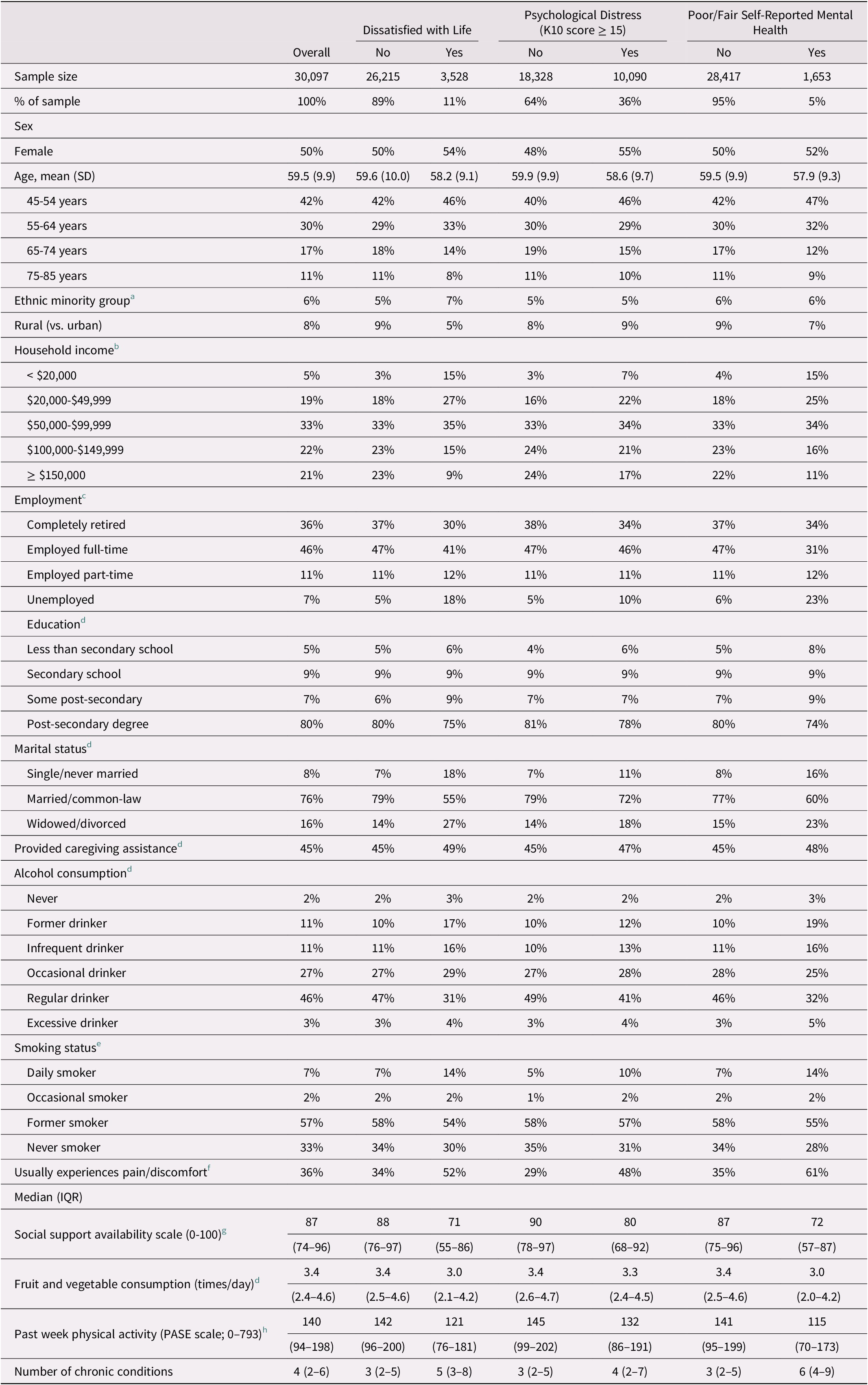

Characteristics of the CLSA participants are summarized in Table 1. Among participants who reported dissatisfaction with life, psychological distress, and poor/fair self-reported mental health, there was a larger proportion of females, participants in the youngest age group (45–54 years), lower income groups, unemployed, participants providing caregiving assistance, single/never married, former and infrequent drinkers, daily smokers, and those usually experiencing pain/discomfort (Table 1). The dissatisfied with life, psychological distress, and poor/fair self-reported mental health groups also had lower levels of social support and physical activity, and more chronic conditions (Table 1).

Table 1. CLSA participant characteristics by psychological well-being measure

Note. Weighted percentages are shown.

a 1,382 observations missing

b 1,941 observations missing

c 2,832 observations missing

d <100 observations missing

e 176 observations missing

f 1,343 observations missing

g 606 observations missing

h 1,570 observations missing.

K10 = Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range; PASE = Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly

Sleep Problems and Psychological Well-Being

Overall, 11 per cent of participants reported dissatisfaction with life, 36 per cent reported psychological distress, and 5 per cent reported poor/fair mental health (Table 1). For sleep duration, 18 per cent of participants reported abnormal sleep duration (13% short duration and 5% long duration). For sleep satisfaction, 26 per cent were dissatisfied with their sleep, whereas 59 per cent were satisfied. Associations among sleep problems, subjective well-being, and psychological distress are summarized in Table 2. All sleep problems were associated with a higher prevalence of poor psychological well-being across all measures in unadjusted models. In fully adjusted models, short sleep duration, but not long sleep, versus normal (PR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.27–1.49), sleep dissatisfaction (PR = 1.85, 95% CI 1.73–1.99), insomnia symptoms (PR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.43–1.65), and associated daytime impairment (PR = 1.83, 95% CI 1.70–1.97) were associated with a higher prevalence of dissatisfaction with life. Both short and long sleep versus normal (short: PR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.11–1.21; long: PR = 1.13, 95% CI 1.06–1.20), sleep dissatisfaction (PR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.27–1.36), insomnia symptoms (PR = 1.28, 95% CI 1.24–1.32), and associated daytime impairment (PR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.35–1.45) were associated with a higher prevalence of psychological distress. For poor/fair self-reported mental health, both short and long sleep versus normal (short: PR = 1.42, 95% CI 1.25–1.61; long: PR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.28–1.82), sleep dissatisfaction (PR = 1.88, 95% CI 1.68–2.09), insomnia symptoms (PR = 1.65, 95% CI 1.47–1.84), and daytime impairment (PR = 2.27, 95% CI 2.02–2.55) were associated with a higher prevalence of poor/fair mental health. In the sensitivity analysis from which respondents with suspected clinical sleep disorders were excluded (n = 7,680 [27%]), associations were partially attenuated, but remained consistent with the main analysis (online supplement, Table S2).

Table 2. Associations between sleep problems and psychological well-being in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (n = 30,097)

Note.

a Model 1 – unadjusted

b Model 2 – adjusted for all socio-demographic, lifestyle, and clinical covariates.

PR = prevalence ratio; CI = confidence interval; K10 = Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.

Effect Modification by Sex and Age

Results for effect modification by sex are presented in Table 3. Associations between psychological distress and sleep dissatisfaction (males: PR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.32–1.47; females: PR = 1.25, 95% CI =1.20–1.31; ratio of PRs = 1.12, 95% CI 1.04–1.19), insomnia symptoms (males: PR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.29–1.43; females: PR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.17–1.27; ratio of PRs = 1.11, 95% CI 1.04–1.19), and daytime impairment (males: PR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.45–1.62; females: PR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.25–1.37; ratio of PRs = 1.18, 95% CI 1.10–1.26) were modified by sex with significantly larger magnitude of effect in males, although associations remained significant in both sexes. No other associations were modified by sex.

Table 3. Modification of the associations between sleep problems and psychological well-being by sex in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging

Note.

a ns shown are unweighted

b PRs adjusted for socio-demographic, lifestyle, and clinical covariates.

PR = prevalence ratio; CI = confidence interval; K10 = Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.

Results for effect modification by age are summarized in Table 4. The association between dissatisfaction with life and daytime impairment caused by insomnia symptoms were modified by age, with an 11 per cent increase in prevalence of dissatisfaction with life with each 10-year increase in age (age × sleep PR = 1.11, 95% CI 1.04–1.19), although associations between dissatisfaction with life and daytime impairment were still significant at all ages. The association between poor/fair self-reported mental health and insomnia symptoms was associated with an 11 per cent decrease in prevalence with each 10-year increase in age (age × sleep PR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.80–0.99). Insomnia symptoms were associated with a higher prevalence of poor/fair self-reported mental health at age 45 (PR = 1.93, 95% CI 1.57–2.37) – an association that decreased and was no longer statistically significant by age 85 (PR = 1.20, 95% CI 0.91–1.59). Larger associations between short and long sleep duration and poor/fair self-reported mental health in younger adults was also observed, albeit that interaction effects between sleep and age were not statistically significant.

Table 4. Modification of the associations between sleep problems and psychological well-being by age in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging

Note.

a PRs adjusted for socio-demographic, lifestyle, and clinical covariates.

PR = prevalence ratio; CI = confidence interval;

Discussion

This study found that sleep problems among middle-aged and older adults in Canada were consistently and independently associated with multiple measures of poor psychological well-being. Specifically, short sleep duration relative to normal, sleep dissatisfaction, insomnia symptoms, and daytime impairment caused by insomnia symptoms were associated with a higher prevalence of dissatisfaction with life, psychological distress, and fair/poor self-reported mental health. Long sleep duration relative to normal was associated with psychological distress and poor/fair self-reported mental health, but not with dissatisfaction with life. This study observed some evidence of effect modification by sex, with larger associations between sleep dissatisfaction, insomnia symptoms, and associated daytime impairment and psychological distress in males than in females, although associations were still statistically significant in both sexes. Effect modification by age was also observed, with stronger associations between daytime impairment and dissatisfaction with life at older ages, although associations remained significant at all ages. Effect modification by age was also observed for associations between insomnia symptoms and poor/fair self-reported mental health, with associations decreasing with age.

Findings from this study, that short and long sleep duration, sleep dissatisfaction, and insomnia symptoms were associated with poor psychological well-being, are consistent with previous studies in international settings (Atkins et al., Reference Atkins, Naismith, Luscombe and Hickie2013; Cunningham, Wheaton, & Giles, Reference Cunningham, Wheaton and Giles2015; Foley et al., Reference Foley, Monjan, Brown, Simonsick, Wallace and Blazer1995; Jacobs, Cohen, Hammerman-Rozenberg, & Stessman, Reference Jacobs, Cohen, Hammerman-Rozenberg and Stessman2006; Lee & Sibley, Reference Lee and Sibley2019; Lukaschek et al., Reference Lukaschek, Vanajan, Johar, Weiland and Ladwig2017; Magee et al., Reference Magee, Caputi and Iverson2011; Ohayon et al., Reference Ohayon, Paskow, Roach, Filer, Hillygus and Chen2019; Paunio et al., Reference Paunio, Korhonen, Hublin, Partinen, Kivima and Koskenvuo2009; Štefan, Vučetić, Vrgoč, & Sporiš, Reference Štefan, Vučetić, Vrgoč and Sporiš2018; Stranges et al., Reference Stranges, Dorn, Shipley, Kandala, Trevisan and Miller2008, Reference Stranges, Tigbe, Gómez-Olivé, Thorogood and Kandala2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wu, Ungvari, Ng, Forester and Gatchel2017; Zhi et al., Reference Zhi, Sun, Li, Wang, Cai and Li2016). These findings are also consistent with Canadian evidence among adults, showing that short and long sleep duration and insomnia symptoms are associated with poor self-reported mental health and dissatisfaction with life (Chaput et al., Reference Chaput, Yau, Rao and Morin2018; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Mei, An, Lu and Wu2020). This study builds on this prior international and Canadian evidence to show that sleep dissatisfaction and daytime impairment caused by insomnia symptoms are also significant and independent correlates of poor psychological well-being. Importantly, this study observed that daytime impairment caused by insomnia symptoms was among the strongest correlates of poor psychological well-being, suggesting that this particular sleep problem is an important factor in well-being, although often overlooked in prior studies.

Mechanisms underlying associations between sleep problems and psychological well-being may be related to the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, particularly for psychological distress. Sleep and stress share pathways through the HPA axis and interact bidirectionally (Hirshkowitz et al., Reference Hirshkowitz, Whiton, Albert, Alessi, Bruni and DonCarlos2015). Sleep deprivation and insomnia lead to hyperactivation of the HPA axis (Buckley & Schatzberg, Reference Buckley and Schatzberg2005; Hirotsu, Tufik, & Andersen, Reference Hirotsu, Tufik and Andersen2015; Meerlo, Sgoifo, & Suchecki, Reference Meerlo, Sgoifo and Suchecki2008; Rodenbeck & Hajak, Reference Rodenbeck and Hajak2001). The HPA axis is also one of the main systems activated in the stress response, affecting brain function, cognition, and mood (Johnson, Kamilaris, Chrousos, & Gold, Reference Johnson, Kamilaris, Chrousos and Gold1992; Meerlo et al., Reference Meerlo, Sgoifo and Suchecki2008). It has been hypothesized that sleep problems, and short sleep duration in particular, may sensitize people to stress-related disorders, including mood disorders, by acting on stress systems such as dysregulation of the HPA axis (Meerlo et al., Reference Meerlo, Sgoifo and Suchecki2008). However, pathways connecting long sleep duration with poor well-being may differ from other sleep domains, as it has been suggested that long sleep is a consequence rather than a cause of poorer health conditions observed in long sleepers, such as depression, obesity, hypertension, and other chronic conditions (Magee et al., Reference Magee, Caputi and Iverson2011; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Rodrigues, Anderson, Wilk, Guaiana and Stranges2020; Patel, Malhotra, Gottlieb, White, & Hu, Reference Patel, Malhotra, Gottlieb, White and Hu2006; Stranges et al., Reference Stranges, Dorn, Shipley, Kandala, Trevisan and Miller2008; Zhai, Zhang, & Zhang, Reference Zhai, Zhang and Zhang2015).

This study found some evidence of effect modification by sex and age. Associations among sleep dissatisfaction, insomnia symptoms, and daytime impairment and psychological distress were stronger in males than in females, contrary to evidence for other health outcomes, which generally show stronger effects in women (Cappuccio et al., Reference Cappuccio, Stranges, Kandala, Miller, Taggart and Kumari2007; Meisinger et al., Reference Meisinger, Heier, Löwel, Schneider and Döring2007; Smiley et al., Reference Smiley, King and Bidulescu2019; Stang et al., Reference Stang, Moebus, Möhlenkamp, Erbel and Jöckel2008; Stranges et al., Reference Stranges, Dorn, Cappuccio, Donahue, Rafalson and Hovey2010). This study’s finding of stronger associations between sleep and psychological distress in males may be related to HPA axis activation, as evidence suggests higher hormone responses, including adrenocorticotropin and cortisol responses, in older males compared with females (Uhart, Reference Uhart, Chong, Oswald, Lin and Wand2006, Kudielka et al., Reference Kudielka, Hellhammer, Hellhammer, Wolf, Pirke, Varadi, Pilz and Kirschbaum1998, Traustadottir et al., Reference Traustadóttir, Bosch and Matt2003). Some effect modification by age was also observed, with stronger associations between daytime impairment and dissatisfaction with life at older ages, whereas associations between insomnia symptoms and poor/fair self-reported mental health decreased with age. It is of note that this study observed consistent associations between abnormal sleep duration and well-being across all ages. The National Sleep Foundation states that sleep from 5 to 6 hours may be appropriate for older adults and that long duration cut-offs of 10 hours and 9 hours may be appropriate for adults and older adults, respectively (Hirshkowitz et al., Reference Hirshkowitz, Whiton, Albert, Alessi, Bruni and DonCarlos2015). Findings from this study suggest that sleep of less than 6 hours and more than 8 hours has detrimental associations with well-being in middle-aged and older adults. Although the strength of some associations between sleep and well-being varied across sex and age, based on the specific sleep problem and well-being measurement, most associations were significant across both sexes and all ages, suggesting that sleep problems are relevant for well-being in both sexes and from middle age to older adulthood.

Strengths and Limitations

This study used a large, national sample to examine associations between sleep problems and psychological well-being among middle-aged and older adults in Canada. Findings from this study are strengthened by the examination of multiple dimensions of sleep patterns, providing an in-depth analysis of the associations between sleep problems and psychological well-being. This study also provides further insight into the differences in associations between sleep problems and well-being across sex and age groups.

Because of the cross-sectional study design, this study was unable to determine the direction of the associations between sleep problems and psychological well-being. Self-reported sleep duration was used, which tends to overestimate objective sleep duration (Jackson, Patel, Jackson, Lutsey, & Redline, Reference Jackson, Patel, Jackson, Lutsey and Redline2018). Studies using a longitudinal approach and objective measures of sleep duration are warranted, particularly to investigate the effects of changes to sleep patterns over time. Also, whereas the National Sleep Foundation guidelines were consulted to define sleep duration, individual sleep needs may differ from guideline recommendations. There are some limitations to the representativeness of the CLSA sample as compared with the Canadian population: the CLSA excludes residents of the Canadian territories and some remote regions, people living on First Nations reserves, full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces, and people who are institutionalized at baseline (e.g., in long-term care). Inclusion criteria for the CLSA requires participants to complete interviews in English or French, and therefore some populations such as recent migrants and people from ethnic minority groups, as well as individuals with disabilities such as hearing problems, memory impairment, and mobility issues, may be under-represented (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Balion and Cossette2019). Therefore, findings from this study may not be generalizable to these groups. Comparison of the CLSA sample with other Canadian data sources suggest that the CLSA Comprehensive Cohort is more educated with a higher household income, and has better self-rated general health (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Wolfson, Kirkland, Griffith, Balion and Cossette2019). Data on sleep and psychotropic medication use were unavailable from the CLSA at the time this study was conducted; therefore, this study was unable to account for medication use in the analysis.

Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest that in an aging population, sleep problems, including abnormal sleep duration, sleep dissatisfaction, insomnia symptoms, and associated daytime impairment, are important independent correlates of psychological well-being, in both sexes and across the lifespan. Overall, these findings, alongside prior Canadian evidence, highlight the importance of common sleep problems for psychological well-being in the Canadian population, and among middle-aged and older adults in particular. Longitudinal studies examining the temporality of the associations between sleep problems and psychological well-being, as well as the effect of changes in sleep patterns on well-being, are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible using data/biospecimens collected by the CLSA. The CLSA is led by Drs. Parminder Raina, Christina Wolfson, and Susan Kirkland. This research has been conducted using the CLSA Baseline Comprehensive Dataset version 3.2, under Application Number 180113. The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the views of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980822000368.

Funding

Funding for the CLSA is provided by the Government of Canada through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research under grant reference LSA 94473 and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. This research has been funded by the Lawson Health Research Institute Internal Research Fund (IRF). Data are available from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (www.clsa-elcv.ca) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to de-identified CLSA data.