Introduction

Jumping to conclusions (JTC) is a well-established reasoning and data gathering bias found in patients with psychosis (Dudley, Taylor, Wickham, & Hutton, Reference Dudley, Taylor, Wickham and Hutton2016; Garety & Freeman, Reference Garety and Freeman2013; So, Siu, Wong, Chan, & Garety, Reference So, Siu, Wong, Chan and Garety2016). It is usually measured by a reasoning task based on a Bayesian model of probabilistic inference known as the ‘beads task’ (Dudley, John, Young, & Over, Reference Dudley, John, Young and Over1997; Huq, Garety, & Hemsley, Reference Huq, Garety and Hemsley1988).

Early work investigating reasoning bias through beads in jars paradigm focused on the association with delusions, finding that patients with delusions tend to require fewer beads to reach a decision than would be expected following Bayesian norms (Huq et al., Reference Huq, Garety and Hemsley1988). In this respect, it has been suggested that data-gathering bias represents a key cognitive component in delusion formation and maintenance (Garety & Freeman, Reference Garety and Freeman1999). Although most of the studies endorsing this association used a cross-sectional design, comparing those with and without delusions in samples of patients with schizophrenia or other psychoses (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Startup, Dunn, Černis, Wingham, Pugh and Kingdon2014; Garety et al., Reference Garety, Joyce, Jolley, Emsley, Waller, Kuipers and Freeman2013), meta-analyses mostly found a weak association with delusions, yet a clear association with psychosis (Dudley et al., Reference Dudley, Taylor, Wickham and Hutton2016; Fine, Gardner, Craigie, & Gold, Reference Fine, Gardner, Craigie and Gold2007; Ross, McKay, Coltheart, & Langdon, Reference Ross, McKay, Coltheart and Langdon2015; So et al., Reference So, Siu, Wong, Chan and Garety2016). Moreover, JTC was found not only in non-delusional and remitted patients with schizophrenia, but also in individuals at clinical high risk and first-degree relatives (Broome et al., Reference Broome, Johns, Valli, Woolley, Tabraham, Brett and McGuire2007; Menon, Pomarol-Clotet, McKenna, & McCarthy, Reference Menon, Pomarol-Clotet, McKenna and McCarthy2006; Moritz & Woodward, Reference Moritz and Woodward2005; Peters & Garety, Reference Peters and Garety2006; Van Dael et al., Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2005).

Overall, these findings suggest that JTC could play a role in the liability for psychotic disorders, perhaps serving as an endophenotype associated with the genetic risk. As a highly heritable and polygenic disorder, many common genetic variants contribute to the risk of schizophrenia, which can be summarised into an individual polygenic risk score (PRS) (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Wray, Stone, Visscher, O'Donovan, Sullivan and Sklar2009; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, 2014). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have found a significant genetic overlap between cognition and schizophrenia (Mistry, Harrison, Smith, Escott-Price, & Zammit, Reference Mistry, Harrison, Smith, Escott-Price and Zammit2018; Ohi et al., Reference Ohi, Sumiyoshi, Fujino, Yasuda, Yamamori, Fujimoto and Hashimoto2018; Shafee et al., Reference Shafee, Nanda, Padmanabhan, Tandon, Alliey-Rodriguez, Kalapurakkel and Robinson2018), and a recent study by Toulopoulou (Toulopoulou et al., Reference Toulopoulou, Zhang, Cherny, Dickinson, Berman, Straub and Weinberger2018) showed that the variance in schizophrenia liability explained by PRS was partially mediated through cognitive deficit. Despite a large body of literature on the JTC bias describing it as a potential intermediate phenotype, to date there has been no investigation into the possible genetic overlap with psychosis through the PRS strategy. Nonetheless, there is a considerable amount of literature suggesting a link between JTC and cognitive functions. Cross-sectional studies on both recent onset psychosis and schizophrenia suggest that patients who present with neuropsychological deficits, especially involving executive functions, display more tendency to jump to conclusions (Garety et al., Reference Garety, Joyce, Jolley, Emsley, Waller, Kuipers and Freeman2013; González et al., Reference González, López-Carrilero, Barrigón, Grasa, Barajas, Pousa and Ochoa2018). Those findings appear to be corroborated by the study of Lunt (Lunt et al., Reference Lunt, Bramham, Morris, Bullock, Selway, Xenitidis and David2012) where JTC bias was found to be more prominent in individuals with prefrontal lesions, especially on the left side of the cortex, compared with controls. Woodward (Woodward, Mizrahi, Menon, & Christensen, Reference Woodward, Mizrahi, Menon and Christensen2009), using a principal component analysis (PCA) in a sample of inpatients with schizophrenia found that neuropsychological functions and JTC loaded on the same factor. Similar findings were obtained in a confirmatory factor analysis on psychotic patients with delusions and controls (Bentall et al., Reference Bentall, Rowse, Shryane, Kinderman, Howard, Blackwood and Corcoran2009). Interestingly in the latter, when general cognitive functioning was included in the model, the association between paranoia and JTC no longer held. In their study comparing patients with delusions, remitted patients with schizophrenia, and controls, Lincoln (Lincoln, Ziegler, Mehl, & Rief, Reference Lincoln, Ziegler, Mehl and Rief2010) found that, after taking intelligence into account, not only the association between JTC and delusions disappeared, but the group effect on the JTC bias was not detected any longer. Likewise, general intelligence affected statistically the relation between JTC and psychosis liability in the van Dael study (Van Dael et al., Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2005). Lower IQ was also found associated with JTC in first episode psychosis (FEP) (Catalan et al., Reference Catalan, Simons, Bustamante, Olazabal, Ruiz, Gonzalez de Artaza and Gonzalez-Torres2015; Falcone et al., Reference Falcone, Murray, Wiffen, O'Connor, Russo, Kolliakou and Jolley2015). Nonetheless, other studies on early psychosis did not detect any association with cognition, possibly due to the small sample size (Langdon, Still, Connors, Ward, & Catts, Reference Langdon, Still, Connors, Ward and Catts2014; Ormrod et al., Reference Ormrod, Shaftoe, Cavanagh, Freeston, Turkington, Price and Dudley2012).

Thus, although many studies highlighted that JTC is strongly associated with delusions, and more broadly with psychosis, this association seems to be affected by the general cognitive function. To address this question robustly requires a large sample size, whereas most previous studies of JTC in psychiatry have had moderate sample sizes of between 20 and 100 patients. Therefore, we used data from the large multi-country EUropean Network of national schizophrenia networks studying the Gene-Environment Interactions (EUGEI) case-control study of FEP to investigate whether IQ plays a role as mediator in the pathway between the bias and the disorder. We also aimed to investigate whether JTC is associated with the liability for psychotic disorders and/or liability to general intellectual function.

Therefore, in this study we aim to test the following predictions:

(1) The JTC bias will be best predicted by clinical status through IQ mediation;

(2) The JTC bias will be predicted by the polygenic risk score for schizophrenia (SZ PRS) and by the polygenic risk score for IQ (IQ PRS).

(3) The JTC bias will be predicted by delusions in patients and psychotic-like experiences (PLEs) in controls.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited and assessed as part of the incidence and first episode case-control study, conducted as part of the EU-GEI programme (Di Forti et al., Reference Di Forti, Quattrone, Freeman, Tripoli, Gayer-Anderson and Quigley2019; Gayer-Anderson, Reference Gayer-Anderson, Jongsma, Di Forti, Quattrone, Velthorst and de Haan2019; Jongsma et al., Reference Jongsma, Gayer-Anderson, Lasalvia, Quattrone, Mulè and Szöke2018). The study was designed to investigate risk factors for psychotic disorders between 1 May 2010 and 1 April 2015 in 17 sites ranging from rural to urban areas in England, France, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain and Brazil.

All participants provided informed, written consent following full explanation of the study. Ethical approval was provided by relevant research ethics committees in each of the study sites. Patients with a FEP were recruited through regular checks across the 17 defined catchment areas Mental Health services to identify all individuals aged 18–64 years who presented with a FEP during the study period. Patients were included if they met the following criteria during the recruitment period: (a) aged between 18 and 64 years; (b) presentation with a clinical diagnosis for an untreated FEP, even if longstanding [International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes F20–F33] and (c) resident within the catchment area at FEP. Exclusion criteria are: (a) previous contact with psychiatric services for psychosis; (b) psychotic symptoms with any evidence of organic causation and (c) transient psychotic symptoms resulting from acute intoxication (ICD-10: F1x.5).

Inclusion criteria for controls are: (a) aged between 18 and 64 years; (b) resident within a clearly defined catchment area at the time of consent into the study; (c) sufficient command of the primary language at each site to complete assessments and (d) no current or past psychotic disorder. To select a population-based sample of controls broadly representative of local populations in relation to age, gender and ethnicity, a mixture of random and quota sampling was adopted. Quotas for control recruitment were based on the most accurate local demographic data available, and then filled using a variety of recruitment methods, including through: (1) random sampling from lists of all postal addresses (e.g. in London); (2) stratified random sampling via general practice (GP) lists (e.g. in London and Cambridge) from randomly selected surgeries and (3) ad hoc approaches (e.g. internet and newspaper adverts, leaflets at local stations, shops and job centres).

Measures

Detailed information on age, sex, self-reported ethnicity, level of education and social networks was collected using the Medical Research Council (MRC) Sociodemographic Schedule (Mallett, Reference Mallett1997).

The short form of the WAIS III was administered as an indicator of general cognitive ability (IQ) and includes the following subtests: information (verbal comprehension), block design (reasoning and problem solving), arithmetic (working memory) and digit symbol-coding (processing speed). This short form has been shown to give reliable and valid estimates of Full-Scale IQ in schizophrenia (Velthorst et al., Reference Velthorst, Levine, Henquet, de Haan, van Os, Myin-Germeys and Reichenberg2013).

Following instructions and practice, the JTC bias was assessed using a single trial of the computerised 60:40 version of the beads task. In this task, there are two jars containing coloured beads with a complementary ratio (60 : 40). One jar is chosen, and beads are drawn one at time and shown to the participants following the pattern: BRRBBRBBBRBBBBRRBRRB, where B indicates a blue bead and R indicates red. After each draw they are required to either decide from which jar the beads have come or defer the decision (up to a maximum of 20 beads). This single-trial experiment was terminated when the participant made the decision of which jar the beads were being drawn from. The key outcome variable employed as an index of the JTC bias was the number of ‘Draws-To-Decision’ (DTD); the lower the DTD, the greater the JTC bias. The binary JTC variable based on the choice of 2 or less beads before answering the task was also employed.

Psychopathology was assessed using the OPerational CRITera system (OPCRIT) (McGuffin, Farmer, & Harvey, Reference McGuffin, Farmer and Harvey1991). Item response modelling was previously used to develop a bi-factor model composed of general and specific dimensions of psychotic symptoms, which include the positive symptom dimension (delusion and hallucination items) (Quattrone et al., Reference Quattrone, Di Forti, Gayer-Anderson, Ferraro, Jongsma, Tripoli and Reininghaus2018). For the purposes of the present work, we adapted the previous method to estimate an alternative bi-factor model comprising two discrete hallucination and delusion symptom dimensions, instead of a single positive symptom dimension. We assessed PLEs in controls through the Community Assessment of Psychic Experience (CAPE) (Stefanis et al., Reference Stefanis, Hanssen, Smirnis, Avramopoulos, Evdokimidis, Stefanis and van Os2002) positive dimension score (online Supplementary Table S1). The CAPE is a self-report questionnaire with good reliability for all the languages spoken in the EUGEI catchment areas (http://www.cape42.homestead.com/).

Polygenic risk scores

The case-control genotyped WP2 EUGEI sample (N = 2169; cases' samples N = 920, controls' samples N = 1248) included DNA extracted from blood (N = 1857) or saliva (N = 312). The samples were genotyped at the MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics in Cardiff (UK) using a custom Illumina HumanCoreExome-24 BeadChip genotyping array covering 570 038 genetic variants. After genotype Quality Control, we excluded SNPs with minor allele frequency <0.5%, Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium p < 10–6, missingness >2%. After sample Quality Control, we excluded samples with >2% missingness, heterozygosity Fhet >0.14 or <−0.11, who presented genotype–phenotype sex mismatch or who clustered with homogenous black ancestry in PCA analysis (N = 170). The final sample was composed of 1720 individuals (1112 of European ethnicity, 608 of any other ethnicities but not black African), of which 1041 controls and 679 patients. Imputation was performed through the Michigan Imputation Server, using the Haplotype Reference Consortium reference panel with the Eagle software for estimating haplotype phase, and Minimac3 for genotype imputation (Das et al., Reference Das, Forer, Schönherr, Sidore, Locke, Kwong and Fuchsberger2016; Loh et al., Reference Loh, Danecek, Palamara, Fuchsberger, A Reshef and K Finucane2016; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Das, Kretzschmar, Delaneau, Wood and Teumer2016). The imputed variants with r 2 < 0.6, MAF <0.1% or missingness >1% were excluded.

The PRS for schizophrenia and IQ was built using, as training data sets, the results from the last available mega-analysis from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, 2014) and Savage et al. (Reference Savage, Jansen, Stringer, Watanabe, Bryois and de Leeuw2018) respectively. In PRSice, individuals' number of risk alleles in the target sample was weighted by the log odds ratio from the discovery samples and summed into the PRSs at a 0.05 SNPs Pt-thresholds (apriori selected). We excluded people of homogeneous African ancestry since in this population the SZ PRS from the PGC2 we calculated, as reported by other studies (Vassos et al., Reference Vassos, Di Forti, Coleman, Iyegbe, Prata, Euesden and Breen2017), failed to explain a significant proportion of the variance (R 2 = 1.1%, p = 0.004).

Design and procedure

The EU-GEI study WP2 employed a case-control design collecting data with an extensive battery of demographic, clinical, social and biological measures (Core assessment); psychological measures, and cognitive tasks. All EU-GEI WP2 participants with JTC and IQ data were included in the current study. All the researchers involved in administrating the assessments undertook a training organised by a technical working committee of the overall EU-GEI study (Work Package 11) at the beginning and throughout the study. Inter-rater reliability was assessed annually to warrant the comparability of procedures and methods across sites.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted in STATA 15 (StataCorp., 2017). Preliminary descriptive analyses were performed using χ2 and t tests to examine the differences in age, sex, ethnicity, level of education, IQ and DTD between cases and controls. To test possible statistical mediation by IQ as intervening variable between case/control status and DTD, we applied Baron and Kenny's procedure (Reference Baron and Kenny1986). According to the authors, a mediation can be established when (1) variations in the independent variable (IV) significantly account for variations in the dependent variable (DV); (2) variations in the IV significantly account for variations in the mediator variable (Rimvall et al.); (3) variations in the MV significantly account for variations in the DV and (4) a previous significant effect of IV on DV is markedly decreased after controlling for MV. Perfect mediation occurs when the independent variable has no effect after controlling for the mediator (Baron & Kenny, Reference Baron and Kenny1986).

The STATA 15 sgmediation command was used to perform three OLS regressions according to Baron and Kenny's steps as follows: (1) DTD (DV) regressed on case/control status (IV) – Path c, (2) IQ (MV) regressed on case/control status (IV) – Path a, (3) DTD (DV) regressed on IQ (MV) and case/control status (IV) – Path b and c’ (Fig. 1). All the steps included as covariates age, sex, ethnicity and country. Furthermore, to generate confidence intervals for the indirect effect, 5000 bootstrap replications were performed (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008) and a non-parametric confidence interval based on the empirical sampling distributions was constructed.

Fig. 1. Mediation model between caseness (IV), IQ (MV) and DTD (DV).

Note: DTD, draws-to-decision; IQ, intelligent quotient.

To investigate whether JTC was associated with the liability for psychotic disorders and general intelligence, we firstly tested the accuracy of the PRSs to predict their primary phenotypes (case/control status and IQ) in our sample through logistic and linear regression models respectively. Then, we built and compared linear regression models regressing DTD on (1) case/control status, controlling for age, sex and 20 principal components for population stratification; (2) SZ PRS and (3) IQ PRS, adjusting for case/control status, age, sex, IQ and 20 principal components for population stratification.

Linear regression models were built to test the effect of the delusion symptom dimension on DTD, adding in the second step as covariates age, sex, ethnicity, IQ and country, in patients. We ran the same models in controls using the CAPE positive score as a predictor.

We repeated all the analyses using as a secondary outcome the binary variable JTC/no JTC (see online supplementary material).

Results

Sample characteristics

Cases and controls recruited as part of the EU-GEI study were included in the current study if data on both Beads task and WAIS were available. This led to a sample of FEP cases = 817 and controls N = 1294 for the mediation analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. FEP recruitment flowchart.

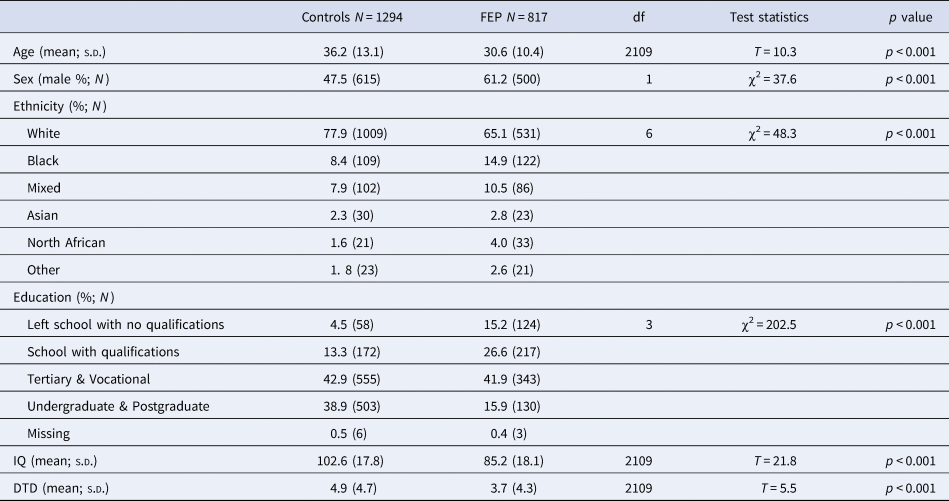

Cases were more often younger (cases mean age = 30.6 ± 10.4 v. controls mean age = 36.2 ± 13.1; t = 10.3, p < 0.001), men [cases 61.2% (500) v. controls 47.5 (615); χ2(1) = 37.6, p < 0.001] and from minority ethnic backgrounds (χ2(6) = 48.3, p < 0.001) compared to controls (Table 1). The aforementioned differences are those expected when comparing psychotic patients with the general population.

Table 1. Demographic and cognitive characteristics of the sample included in the analysis

Note: DTD, draws-to-decision; IQ, intelligent quotient.

The analysis of PRSs was performed in a subsample of 519 FEP and 881 population controls with available GWAS data.

Jumping to conclusions, psychosis and IQ

The results of the mediation model are displayed in Fig. 3. There was evidence of a negative association between caseness and DTD in path c [B = −1.4 (0.2); 95% CI −1.8 to −0.9; p < 0.001; adjusted R 2 = 8%]; as well as with IQ in Path a [B = −16. 7 (0.8); 95% CI −18.24 to −15.10; p < 0.001]. Path b showed that higher IQ scores were significantly related to more DTD [B = 0.06 (0.01); 95% CI 0.05–0.07; p < 0.001]. The direct effect of case status on DTD displayed in path c’ markedly dropped from −1.4 to −0.3 and was no longer statistically significant [B = −0.3 (0.2); 95% CI −0.7 to 0.1; p = 0.19]. The estimated proportion of the total effect of case status on DTD mediated by IQ was 79% and the variance explained by the model rose to 14%. After performing 5000 bootstrap replications, the estimated indirect effect remained statistically significant [B = −0.2 (0.02); 95% CI −0.3 to −0.2].

Fig. 3. Mediation results.

Note: DTD, draws-to decision; IQ, intelligent quotient. **p < 0.001.

Jumping to conclusions, SZ PRS and IQ PRS

Sz PRS was a predictor for case status (OR 5.3, 95% CI 3.7–7.5, p < 0.001), explaining 7% of the variance, as well as IQ PRS for IQ (B = 3.9, 95% CI 2.9–4.9, p < 0.001), accounting for 14% of the variance. As is shown in Table 2, SZ PRS was not significantly associated with JTC, but in fact was non-significantly association with increased numbers of beads drawn (B = 0.5, 95% CI −0.2 to 1.2, p = 0.17); whereas IQ PRS was positively associated with the number of beads drawn (B = 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.8, p < 0.001). When adding the IQ PRS to case-control status as a predictor of DTD, the variance explained rose to 10%, of which 1% was due to the PRS term. This relationship held even after adjusting for IQ (B = 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.6, p = 0.017).

Table 2. Linear regressions of PRS predicting DTD

SZ, schizophrenia; PRS, polygenic risk score; IQ, intelligent quotient.

a Adjusted for age, sex and 20 principal components for population stratification.

b Adjusted for case/control, age, sex and 20 principal components for population stratification.

c Adjusted for case/control, age, sex, IQ and 20 principal components for population stratification.

Jumping to conclusions, positive symptoms and psychotic-like experiences

The delusion symptom dimension was positively associated with DTD (B = 0.4, 95% CI 0.1–0.8, p = 0.013), although the association became less accurate when adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, IQ and country, with the 95% confidence interval including zero effect (B = 0.1, 95% CI −0.2 to 0.4, p = 0.531). The hallucination dimension was not a robust predictor of DTD, whether or not covariates were modelled (unadjusted B = −0.3, 95% CI −0.7 to 0.1, p = 0.089). Whereas the CAPE positive symptoms score was negatively associated with the number of beads requested by controls (B = −2.5, 95% CI −3.8 to −1.3, p < 0.001), which remained significant even after controlling for age, sex, ethnicity, IQ and country (B = −1.7, 95% CI −2.8 to −0.5, p = 0.006).

Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the relation between the JTC bias and general cognitive ability in the first episode psychotic patients. We used the largest to date incidence sample of FEP patients and population-based controls with available data on the JTC bias to address the question: is the link between the bias and the disorder better explained by the mediation of IQ? Moreover, this is the first study to test the association between JTC and genetic susceptibility to schizophrenia.

We found that IQ is accountable for about 80% of the effect of caseness on JTC. The data in fact indicated that case control differences in JTC were not only partially mediated by IQ but were fully mediated by IQ. In other words, the JTC bias in FEP might not be an independent deficit but part of general cognitive impairment. We obtained similar results also using the binary outcome JTC yes/no (see online supplementary material). Previous studies focusing on different explanations between the JTC bias and psychotic disorder suggested that deluded patients tend to request less information because sampling itself might be experienced as more costly than it would be by healthy people (Ermakova et al., Reference Ermakova, Gileadi, Knolle, Justicia, Anderson and Fletcher2018; Moutoussis, Bentall, El-Deredy, & Dayan, Reference Moutoussis, Bentall, El-Deredy and Dayan2011). Although patients at onset seem to adjust their strategy according to the cost of sampling where clearly stated and show more bias to sample less information in the classic task, general cognitive ability still plays an important role in their decision-making behaviour (Ermakova et al., Reference Ermakova, Gileadi, Knolle, Justicia, Anderson and Fletcher2018; Moutoussis et al., Reference Moutoussis, Bentall, El-Deredy and Dayan2011). Indeed, the inclusion of general cognitive ability in the relation between JTC and clinical status was reported to substantially decrease or nullify a prior significant association (Falcone et al., Reference Falcone, Murray, Wiffen, O'Connor, Russo, Kolliakou and Jolley2015; Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Ziegler, Mehl and Rief2010; Van Dael et al., Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2005). Our results are consistent with these studies and provide the first evidence that the genetic variants associated with IQ are negatively correlated with JTC, therefore endorsing the hypothesis that cognition as endophenotype mediates the relation between the bias and the liability for psychotic disorders.

In our study SZ PRS was not significantly associated with JTC. However, as the PRS technique is based on contribution of common SNPs variation to genetic risk, its detection is strictly dependent on statistical power (Smoller et al., Reference Smoller, Andreassen, Edenberg, Faraone, Glatt and Kendler2019; Wray et al., Reference Wray, Lee, Mehta, Vinkhuyzen, Dudbridge and Middeldorp2014). Although GWAS studies on schizophrenia have already identified a substantial number of genetic variants by increasing sample size (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, 2014), SZ PRS still accounts for 7% of the variance in schizophrenia liability, as we also found in our sample. Whereas, IQ PRS is based on a far larger GWAS (Savage et al., Reference Savage, Jansen, Stringer, Watanabe, Bryois and de Leeuw2018), explaining as twice the variance as SZ PRS in our study. We note that the effect sizes (quantified by estimated regression parameters) between the schizophrenia PRS and DTD was similar in size to, but, contrary to expectation, in the same direction as, the effect size between the IQ PRS and DTD (but note the former association was non-significant). Another possible explanation lies in the fact that JTC seems to be more associated with the continuous distribution of delusions rather than with schizophrenia per se (Broome et al., Reference Broome, Johns, Valli, Woolley, Tabraham, Brett and McGuire2007; Menon et al., Reference Menon, Pomarol-Clotet, McKenna and McCarthy2006; Moritz & Woodward, Reference Moritz and Woodward2005; Peters & Garety, Reference Peters and Garety2006; Van Dael et al., Reference Van Dael, Versmissen, Janssen, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Krabbendam2005). In fact, in a large case-control study on FEP patients carried out by Falcone et al. (Reference Falcone, Murray, Wiffen, O'Connor, Russo, Kolliakou and Jolley2015), adjusting for IQ and working memory abolished the relation between JTC and clinical status, but the association between JTC and delusion severity remained. Perhaps building a PRS based on the positive symptom dimension or delusions would be more associated with the bias. However, in line with a recent finding that patients with higher delusion severity may have a tendency to increased information seeking (Baker, Horga, Konova, & Daw, Reference Baker, Horga, Konova and Daw2019), we found delusions were associated with higher number of beads drawn, although with a small effect size and attenuation after adjustment. Whereas, the direction of the effect of PLE on the number of beads requested by controls was expected (Freeman, Pugh, & Garety, Reference Freeman, Pugh and Garety2008; Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Rauschenberg, ten Have, de Graaf, van Dorsselaer, Simons and van Os2018; Ross et al., Reference Ross, McKay, Coltheart and Langdon2015), and more interestingly independent from IQ. Perhaps in the absence of general cognitive impairment, the tendency to JTC contributes to PLE independent of general intellectual function, whereas in the context of disorder with general cognitive impairment, the JTC bias may not specifically relate to the pathogenesis of psychosis. Future research is warranted to further address this relation.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several advantages. These include the large sample size, the study of patients at the onset of illness and population controls. There are limitations to our study. Although the sample size is several times larger than any individual previous study, it is still modest by genomic standards. We only included a single trial of the task, as previous research has indicated that the measure of DTD is very reliable over trials (Ermakova et al., Reference Ermakova, Gileadi, Knolle, Justicia, Anderson and Fletcher2018; Ermakova, Ramachandra, Corlett, Fletcher, & Murray, Reference Ermakova, Ramachandra, Corlett, Fletcher and Murray2014), to facilitate data collection in this large multi-centre study. It can be argued that only performing one trial using the higher cognitive demanding 60:40 version could capture more miscomprehension of the task rather than truly the bias, resulting in overestimating its presence (Balzan, Delfabbro, & Galletly, Reference Balzan, Delfabbro and Galletly2012a; Balzan, Delfabbro, Galletly, & Woodward, Reference Balzan, Delfabbro, Galletly and Woodward2012b). However, the beads task employed in the study included a practice exercise before the trial. Moreover, the difference between means of beads requested by cases and controls in our study was smaller than reported in a meta-analysis on 55 studies (1.1 v. 1.4 to 1.7) (Dudley et al., Reference Dudley, Taylor, Wickham and Hutton2016). Nonetheless, future research is warranted to explore more specific cognitive mediation, such as working memory and executive functions (Falcone et al., Reference Falcone, Murray, Wiffen, O'Connor, Russo, Kolliakou and Jolley2015; Garety et al., Reference Garety, Joyce, Jolley, Emsley, Waller, Kuipers and Freeman2013; González et al., Reference González, López-Carrilero, Barrigón, Grasa, Barajas, Pousa and Ochoa2018), between JTC and psychosis using more trials of the Beads Task. The inclusion of more trials in future studies would permit a more detailed interrogation of the task (Ermakova et al., Reference Ermakova, Ramachandra, Corlett, Fletcher and Murray2014, Reference Ermakova, Gileadi, Knolle, Justicia, Anderson and Fletcher2018). For example, the use of multiple trials allows modelling of latent variables such as the probing of the distinct roles of cognitive noise and alterations in the perceived ‘cost’ of information sampling, which may have partially distinct genetic bases. We did not measure delusions with a symptom severity rating scale, but rather calculated a measure of a delusions factor using an item-response analysis from OPCRIT identified symptoms, so we caution over-interpretation of the analysis of the relation between DTD and delusions within the patient group. The CAPE self-report questionnaire was only completed by controls, in accordance with its original design for use in community samples.

Implications

Our results suggested that the tendency to jump to conclusions may be associated with psychosis liability via a general cognitive pathway. In fact, improvements on data-gathering resulting in delayed decision making seem to be driven by cognitive mechanisms as shown in Randomised Control Trials comparing Metacognitive Training (MCT) – which JTC is a core module – with Cognitive Remediation Therapy in schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Moritz et al., Reference Moritz, Veckenstedt, Bohn, Hottenrott, Scheu, Randjbar and Roesch-Ely2013, Reference Moritz, Veckenstedt, Andreou, Bohn, Hottenrott, Leighton and Roesch-Ely2014). However, psychosis liability does not necessarily translate to other outcomes of interest in psychosis, such as prognosis; for example, Andreou (Andreou et al., Reference Andreou, Treszl, Roesch-Ely, Köther, Veckenstedt and Moritz2014) using the same sample as Moritz (Moritz et al., Reference Moritz, Veckenstedt, Bohn, Hottenrott, Scheu, Randjbar and Roesch-Ely2013) found that JTC was the only significant predictor of improvement in vocational status at 6 months follow up in terms of probability of regaining full employment status. Similarly, Dudley (Dudley et al., Reference Dudley, Daley, Nicholson, Shaftoe, Spencer, Cavanagh and Freeston2013) found that patients who displayed stable JTC after 2 years showed an increase in symptomatology, whereas stable non-jumpers showed a reduction, as did those who switched to be a non-jumper. Although the aforementioned study did not account for cognition, results are in line with the literature showing the efficacy of MCT on delusion severity and general functioning up to 3-year-follow-up (Favrod et al., Reference Favrod, Rexhaj, Bardy, Ferrari, Hayoz, Moritz and Bonsack2014; Moritz et al., Reference Moritz, Veckenstedt, Bohn, Hottenrott, Scheu, Randjbar and Roesch-Ely2013, Reference Moritz, Veckenstedt, Andreou, Bohn, Hottenrott, Leighton and Roesch-Ely2014), and even in individuals with recent onset of psychosis (Ochoa et al., Reference Ochoa, López-Carrilero, Barrigón, Pousa, Barajas, Lorente-Rovira and Moritz2017). Moreover, a recent study (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Ajnakina, Stilo, Mondelli, Marques, Trotta and Murray2018) which followed up the FEP sample reported in Falcone et al., (Reference Falcone, Murray, Wiffen, O'Connor, Russo, Kolliakou and Jolley2015), showed that JTC at baseline predicted poorer outcome in terms of more days of hospitalisation, compulsory admissions and higher risk of police intervention at 4-year follow-up, even after controlling for IQ.

Thus, although JTC bias might be secondary to a cognitive impairment in the early stages of psychosis, JTC could play an important role in both delusions' maintenance and clinical outcome. Therefore, targeting this bias along with other cognitive deficits in psychosis therapies and interventions might represent a useful strategy to improve outcomes (Andreou et al., Reference Andreou, Treszl, Roesch-Ely, Köther, Veckenstedt and Moritz2014; Moritz et al., Reference Moritz, Veckenstedt, Bohn, Hottenrott, Scheu, Randjbar and Roesch-Ely2013). However, our data suggest that specific interventions to address this particular cognitive bias in terms of psychosis liability may not provide any advantage over and above cognitive remediation of general cognitive deficits (Wykes et al., Reference Wykes, Newton, Landau, Rice, Thompson and Frangou2007).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171900357X

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Medical Research Council, the European Community's Seventh Framework Program grant [agreement HEALTH-F2-2009-241909 (Project EU-GEI)], São Paulo Research Foundation (grant 2012/0417-0), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London, the NIHR BRC at University College London and the Wellcome Trust (grant 101272/Z/12/Z).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the work presented in this paper.

Group information

The European Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying Gene-Environment Interactions WP2 Group members includes:

Amoretti, Silvia, PhD Barcelona Clinic Schizophrenia Unit, Neuroscience Institute, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, CIBERSAM, Spain; Andreu-Bernabeu, Álvaro, MD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, CIBERSAM, IiSGM, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain; Baudin, Grégoire, MSc, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor,’ Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France; Beards, Stephanie, PhD, Department of Health Service and Population Research, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, England; Bonetto, Chiara, PhD, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; Bonora, Elena, PhD, Department of Medical and Surgical Science, Psychiatry Unit, Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Viale Pepoli 5, 40126 Bologna, Italy; Cabrera, Bibiana, MSc, PhD, Barcelona Clinic Schizophrenia Unit, Neuroscience Institute, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, CIBERSAM, Spain; Carracedo, Angel, MD, PhD, Fundación Pública Galega de Medicina Xenómica, Hospital Clínico Universitario, Santiago de Compostela, Spain; Charpeaud, Thomas, MD, Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France, CMP B CHU, Clermont Ferrand, France, and Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France; Costas, Javier, PhD, Fundación Pública Galega de Medicina Xenómica, Hospital Clínico Universitario, Santiago de Compostela, Spain; Cristofalo, Doriana, MA, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; Cuadrado, Pedro, MD, Villa de Vallecas Mental Health Department, Villa de Vallecas Mental Health Centre, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor/Hospital Virgen de la Torre, Madrid, Spain; D’Andrea, Giuseppe, MD, Department of Medical and Surgical Science, Psychiatry Unit, Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Viale Pepoli 5, 40126 Bologna, Italy; Díaz-Caneja, Covadonga M, MD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, CIBERSAM, IiSGM, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain; Durán-Cutilla, Manuel, MD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, CIBERSAM, IiSGM, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain; Fraguas, David, MD, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, CIBERSAM, IiSGM, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain; Ferchiou, Aziz, MD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor’, Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France; Franke, Nathalie, MSc, Department of Psychiatry, Early Psychosis Section, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Frijda, Flora, MSc, Etablissement Public de Santé Maison Blanche, Paris, France; García Bernardo, Enrique, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital GeneralUniversitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Garcia-Portilla, Paz, MD, PhD, Department of Medicine, Psychiatry Area, School of Medicine, Universidad de Oviedo, ISPA, INEUROPA, CIBERSAM, Oviedo, Spain; González Peñas, Javier, PhD, Hospital Gregorio Marañón, IiSGM, School of Medicine, Calle Dr Esquerdo, 46, Madrid 28007, Spain; González, Emiliano, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Hubbard, Kathryn, MSc, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London, London; Jamain, Stéphane, PhD, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; Jiménez-López, Estela, MSc, Department of Psychiatry, Servicio de Psiquiatría Hospital ‘Virgen de la Luz,’ Cuenca, Spain; Leboyer, Marion, MD, PhD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor,’ Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; López Montoya, Gonzalo, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Lorente-Rovira, Esther, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Universidad de Valencia, CIBERSAM, Valencia, Spain; Marcelino Loureiro, Camila, MD, Departamento de Neurociências e Ciencias do Comportamento, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, and Núcleo de Pesquina em Saúde Mental Populacional, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil; Marrazzo, Giovanna, MD, PhD, Unit of Psychiatry, ‘P. Giaccone’ General Hospital, Palermo, Italy; Martínez Díaz-Caneja, Covadonga, MD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM, CIBERSAM, Madrid, Spain; Matteis, Mario, MD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Messchaart, Elles, MSc, Rivierduinen Centre for Mental Health, Leiden, the Netherlands; Mezquida, Gisela, PhD, Centre for Biomedical Research in the Mental Health Network (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Barcelona Clinic Schizophrenia Unit, Neuroscience Institute, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Moltó, Ma Dolores, Department of Genetics, University of Valencia, Campus of Burjassot, Biomedical Research Institute INCLIVA, Valencia, Spain, Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Moreno, Carmen, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Nacher Juan, Neurobiology Unit, Department of Cell Biology, Interdisciplinary Research Structure for Biotechnology and Biomedicine (BIOTECMED), Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM): Spanish National Network for Research in Mental Health, Madrid, Spain, Fundación Investigación Hospital Clínico de Valencia, INCLIVA, Valencia, Spain; Olmeda, Ma Soledad, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain; Parellada, Mara, MD, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Pignon, Baptiste, MD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor,’ Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National dela Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; Rapado, Marta, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Richard, Jean-Romain, MSc, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; Rodríguez Solano, José Juan, MD, Puente de Vallecas Mental Health Department, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor/Hospital Virgen de la Torre, Centro de Salud Mental Puente de Vallecas, Madrid, Spain; Roldán, Laura, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM, CIBERSAM, C/Doctor Esquerdo 46, 28007 Madrid; Spain; Ruggeri, Mirella, MD, PhD, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; Sáiz, Pilar A, MD, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Oviedo, CIBERSAM. Instituto de Neurociencias del Principado de Asturias, INEUROPA, Oviedo, Spain; Servicio de Salud del Principado de Asturias (SESPA), Oviedo, Spain; Sánchez-Gutierrez, Teresa, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM, CIBERSAM, C/Doctor Esquerdo 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain; Sánchez, Emilio, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain; Schürhoff, Franck, MD, PhD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor,’ Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; Seri, Marco, MD, Department of Medical and Surgical Science, Psychiatry Unit, Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Viale Pepoli 5, 40126 Bologna, Italy; Shuhama, Rosana, PhD, Departamento de Neurociências e Ciencias do Comportamento, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, and Núcleo de Pesquina em Saúde Mental Populacional, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil; Sideli, Lucia, PhD, Department of Experimental Biomedicine and Clinical Neuroscience, University of Palermo, Via G. La Loggia 1, 90129 Palermo, Italy; Stilo, Simona A, MD, PhD, Department of Health Service and Population Research, and Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, England; Termorshuizen, Fabian, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands, and Rivierduinen Centre for Mental Health, Leiden, the Netherlands; Tronche, Anne-Marie, MD, Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France, CMP B CHU, Clermont Ferrand, France, and Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France; van Dam, Daniella, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Early Psychosis Section, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; van der Ven, Els, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands, Rivierduinen Centre for Mental Health, Leiden, the Netherlands, and Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY.