Anaemia is defined as the condition in which the content of Hb in the blood is below the ideal in individuals within the same reference population(1). In addition to genetic factors, many causes can lead to anaemia such as malaria and others parasitic infections, current infectious disease and the deficiency of some nutrients such as Fe, Zn, vitamin B12 and proteins, especially in developing regions(Reference Paula, Caminha and Figueiroa2). Besides this, poor socio-demographic conditions are some of the risk factors for anaemia well described in the literature(Reference Neuman, Tanaka and Szarfarc3,Reference Leal, Batista Filho and de Lira4) . According to WHO, it is estimated that Fe deficiency is the main cause of anaemia(1).

Therefore, the prevalence of anaemia is used as a proxy indicator to estimate Fe deficiency at the population level(Reference Leal, Batista Filho and de Lira4).This nutritional deficiency, which is present all over the world, is recognised as one of the most relevant, especially due to the vulnerability to which the groups of children under 5 years of age, pregnant women and women in reproductive age are subjected(Reference Camaschella5,Reference Lopez, Cacoub and Macdougall6) .

The damaging effects of anaemia are associated with severe harm to cognitive and motor development of children, academic performance and higher susceptibility to infections. Thus, this deficiency is considered an important public health problem both in wealthier countries and medium- and low-income nations(Reference Gupta, Perrine and Mei7,Reference Peyrin-Biroulet, Williet and Cacoub8) .

The global prevalence of anaemia in children under 5 years of age decreased from 47 to 43 % from 1995 to 2011 and was different among regions, being higher in Central, Western and Eastern Africa, as well as in South Asia(1,Reference Stevens, Finucane and De-Regil9) . In these countries, the prevalence of anaemia in children under 5 years of age was at least 55 % in 2011, which is five times higher than in wealthier countries. Despite the global tendency of decline described by Stevens et al., from 1995 to 2011, the prevalence stagnated in high-income countries in this period, and in South Africa, it increased from 30 to 46 %(Reference Stevens, Finucane and De-Regil9).

More recently, the WHO published an analysis about anaemia in the world, which showed that preschool-aged children are the most affected, with an estimated prevalence of 41·7 %(10).

Brazil is a medium-income country that is going through a nutritional transition characterised by the existence of a double load of diseases, with expressive increase in obesity, a still relevant prevalence of child malnutrition, and persistence of anaemia as an important public health problem in the maternal–infant group(11,Reference Conde and Monteiro12) . The only national investigation that evaluated anaemia in the maternal–infant population revealed prevalence of 20·9 % in children under 5 years of age in 2006 and 2007, being considered a moderate public health problem in Brazil(13). Local studies show great differences in the prevalence of anaemia according to regions, sample size and place of execution, with the classification varying from moderate(Reference Paula, Caminha and Figueiroa2,Reference Oliveira, Oliveira and Silva14,Reference Zuffo, Osório and Taconeli15) to severe(Reference Frota16,Reference Leite, Cardoso and Coimbra17) magnitude in the country.

Due to the shortage of studies with national representativity which reveals the current situation of Fe-deficiency anaemia and its associated factors in Brazil, the present study had the objective of conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis in order to estimate the national group prevalence of Fe-deficiency anaemia in children under 5 years of age. It also proposes to determine the factors involved in the variability of the estimate of anaemia prevalence in Brazil.

Two systematic reviews and meta-analysis previously published reported a pooled prevalence of anaemia in Brazilian children according different settings(Reference Ferreira, Vieira and Livramento18,Reference Vieira and Ferreira19) . In the more recent paper was evaluated data published through to 22 May 2019. In the studies of Vieira and Ferreira (2010)(Reference Vieira and Ferreira19) and Ferreira et al. (2020)(Reference Ferreira, Vieira and Livramento18) included thirty-five and thirty-seven studies, respectively. However, to our knowledge, no systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated anaemia prevalence in Brazilian children under 5 years of age stratified by geographic region and age group.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis were reported according to the guidelines by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff20). The protocol of the present study was submitted to International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), being registered under number CRD42017075431.

Data source and search strategy

To identify the studies that evaluated anaemia prevalence in Brazilian children under 5 years of age, the databases MEDLINE, LILACS and Web of Science were reviewed in April of 2020 to search for articles without date or language restrictions. In the literature search, terms of the outcome were combined with each of the terms for the age group and local/population of study, as described below.

- MEDLINE: ((((((((((((anemia) OR anaemia) OR iron deficiency anemia) OR iron deficiency anaemia) OR hemoglobin) OR haemoglobin) OR human hemoglobin) OR human haemoglobin) OR hemoglobin levels) OR haemoglobin levels)) AND (((((children) OR newborns) OR infants) OR preschoolers) OR preschool children)) AND ((brazil) OR brazilian) [All Fields];

- LILACS: (((((‘ANEMIA’) or ‘ANAEMIA’) or ‘ANEMIA/IRONDEFICIENCY’) or ‘ANAEMIA-IRON-DEFICIENCY’) or ‘HEMOGLOBIN’) or ‘HAEMOGLOBIN’ [Palavras] and ((((‘CHILDREN’) or ‘NEWBORNS’) or ‘INFANTS’) or ‘PRESCHOOLERS’) or ‘PRESCHOOL CHILDREN’ [Palavras] and (‘BRAZIL’) or ‘BRAZILIAN’ [Words];

- Web of Science: TS=(((((((((((anemia) OR anaemia) OR iron deficiency anemia) OR iron deficiency anaemia) OR hemoglobin) OR haemoglobin) OR human hemoglobin) OR human haemoglobin) OR hemoglobin levels) OR haemoglobin levels)) AND TS=((((((children) OR newborns) OR infants) OR preschoolers) OR preschool children)) AND TS=(((brazil) OR brazilian) Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, ESCI Timespan=All years;

Furthermore, the reference list of the chosen articles was researched to identify studies that were not found in the database search. We also searched grey literature through thesis and dissertations databases and contacted renowned professionals in the field to obtain references of published or unpublished works that could be part of the present study.

Two independent researchers, using the same search strategy, performed the bibliographic search. The searches were compared, and discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer.

Eligibility criteria

The included studies evaluated anaemia, Fe deficiency or Fe-deficiency anaemia in children under the age of 5 years, and they should have been developed in Brazil mandatorily. The excluded studies were the ones that did not investigate these outcomes; evaluated other types of anaemia unrelated to Fe consumption; involved children above 5 years of age; did not present sample calculation or presented convenience sampling; used method anaemia testing without digital or venous puncturing and registrations from reviews and editorials.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers selected the studies independently. After excluding duplicates, titles and abstracts were analysed to exclude the studies that were obviously irrelevant to this review. The complete texts from the remaining studies were evaluated, and the eligible studies for this review were identified. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Using a standardised protocol, two reviewers extracted data from the included studies independently, and the forms were compared. From the selected articles, the following information was extracted, besides anaemia prevalence: name of the authors, year of publication, complete title of the work, period of data collection, place of study (geographic space defined between urban or rural or that occurred in both simultaneously; city and state; location of the child in the moment of data collection – health services, schools or day care and residence visits), type of study (cross-sectional, cohort, case control or intervention), sex of target population (male and female), sample calculation (description of the calculations, expected sample, collected sample and loss percentage when it occurred), age range of target population (in months), method of Hb testing (portable haemoglobinometer and automated blood cells counter) and cut-off points for definition of anaemia (value and reference).

A few studies did not provide the 95 % CI of anaemia prevalence. Therefore, they were calculated from sample size and number of events in the sample through formulas on the open software Microsoft Office Excel (version 365)®.

Data analysis

The geolocation of the studies was performed on QGIS® software (desktop version 2·18·20), and the coordinates in decimal degrees of each municipality were used. For the classification of anaemia magnitude as a public health problem, prevalence values proposed by the WHO(11) were used, such as < 5·0 %, it is not considered a problem; 5·0 to 19·9 %, mild problem; 20·0 to 39·9 %, moderate problem and ≥ 40·0 %, severe problem.

The statistical analyses were conducted using Stata® software version 14.0 (StataCorp). The estimates of group prevalence of anaemia in Brazil by region and age range were determined from estimates of prevalence from the studies included in this review.

Initially, the studies were combined using fixed effects models, and the heterogeneity was evaluated using Q and I 2-test. In the case of the Q-test statistically significant or I 2 > 50 %, which means heterogeneity between studies, the estimates were grouped using random effects models(Reference Higgins and Thompson21).

Once the significant heterogeneity in the studies was identified, the next step was to perform bivariate analyses to test the individual association of each variable (methodological variables) with the estimate of group prevalence of Fe-deficiency anaemia on a national level using meta-regression analysis(Reference Higgins and Thompson21). This analytical strategy evaluated which variables affected the results. The evaluated methodological variables were sample size, age range, sample origin, area of influence, year of data collection and methods of Hb testing.

Afterwards, random effects model was used to evaluate sources of variability in the estimate of group prevalence of Fe deficiency anaemia on a national level. All of the co-variables associated with the prevalence rates of anaemia in the bivariate analyses, considering a P value < 0·20(Reference Maldonado and Greenland22), were included in the final multi-variate meta-regression model. For these analyses, a significance level of 5 % was established.

Assessment of the methodological quality of included studies

We used a checklist adapted from Hoy et al. (Reference Hoy, Brooks and Woolf23) to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. It is composed of nine questions that evaluate sampling, response rate, data collection, the instrument used in the study and the statistical reporting. Each question had a range score from ‘0’ to ‘1’, which corresponded to ‘low risk of bias’ and ‘high risk of bias’, respectively. The total score ranged from 0 to 9, which each tertile corresponded from low (0–3) to moderate (4–6) and high risk of bias (7–9).

Results

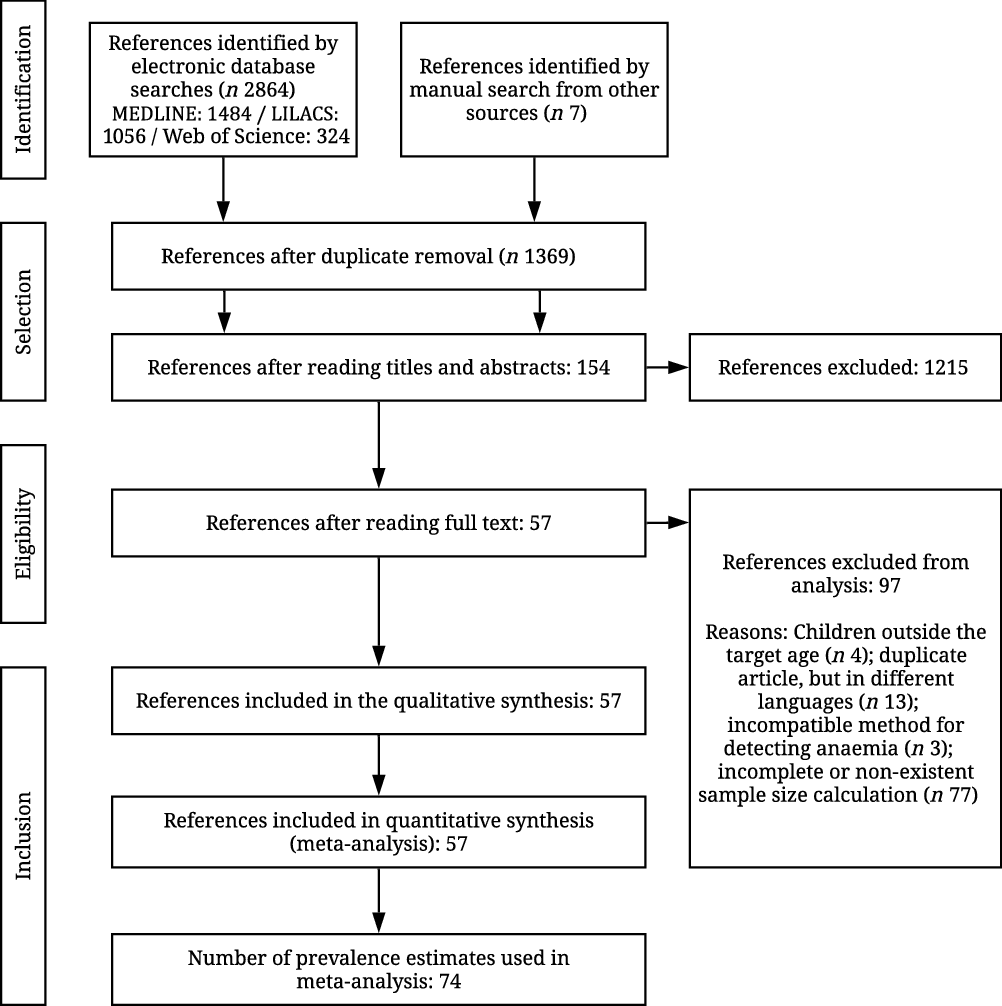

The search in the electronic databases and reverse search resulted in a total of 2871 studies. After excluding duplicates and reading titles and abstracts, 154 studies remained to read their contents in full. At the end of this last stage, fifty-seven articles remained, which comprised the qualitative analysis of this review. The reasons for exclusions from the studies can be seen in the study selection flow chart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Research and selection flow chart of studies that are part of this systematic review and meta-analysis.

The chosen studies involved children aged between 0 and 84 months, but for this review, only those who had age stratification were maintained, allowing data to be obtained for children under 59 months of age. As for the method of identifying blood Hb rates, most studies used portable haemoglobinometers (n 42) (data not presented in table).

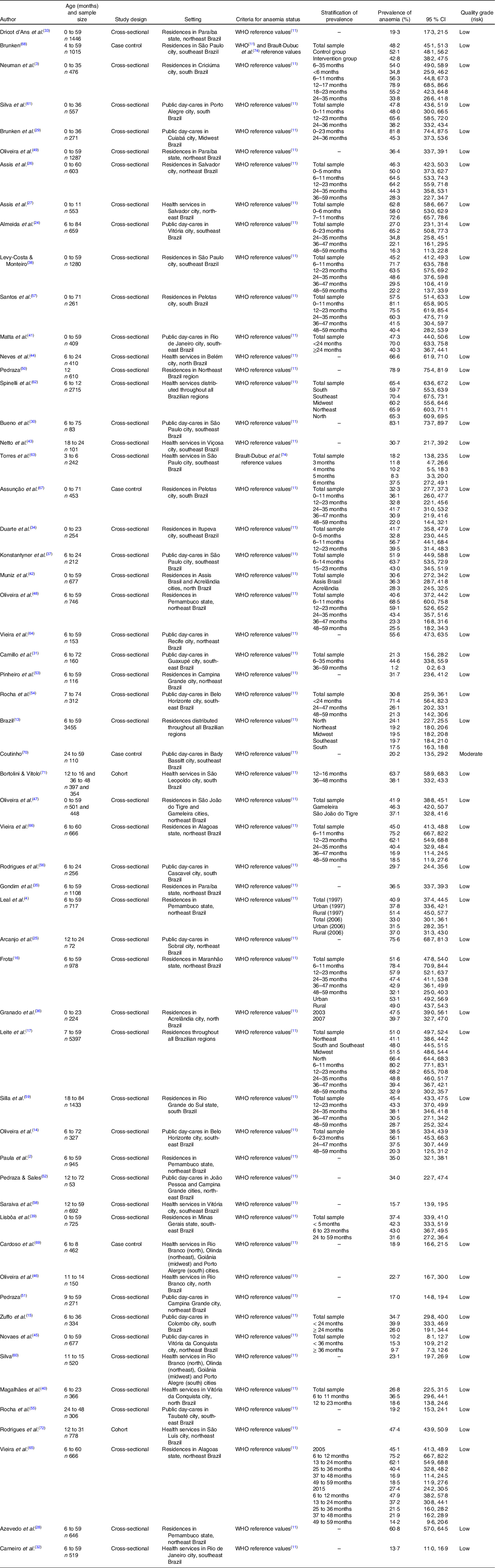

Among the fifty-seven studies, fifty-one were cross-sectional(Reference Paula, Caminha and Figueiroa2–Reference Leal, Batista Filho and de Lira4,13–Reference Leite, Cardoso and Coimbra17,Reference Almeida, Zandonade and Abrantes24–Reference Vieira, Ferreira and Costa66) , while the others were longitudinal(Reference Assunção, Santos and Barros67–Reference Rodrigues72). All geographic regions of Brazil (North, Northeast, Midwest, South and Southeast) were considered. Most of the studies were developed in the Northeast region of Brazil(Reference Paula, Caminha and Figueiroa2,Reference Leal, Batista Filho and de Lira4,Reference Frota16,Reference Arcanjo, Santos and Arcanjo25–Reference Azevedo, Caminha and Cruz28,Reference Dricot d’Ans, Dricot and Santos33,Reference Gondim, Diniz and Souto35,Reference Magalhães, Maia and Pereira Netto40,Reference Novaes, Gomes and Silveira45,Reference Oliveira, Lira and Osório47–Reference Pedraza51,Reference Pinheiro, Santos and Cagliari53,Reference Vieira, Diniz and Cabral64–Reference Vieira, Ferreira and Costa66,Reference Rodrigues72,Reference Pedraza, Queiroz and Paiva73) , followed by the Southeast region(Reference Oliveira, Oliveira and Silva14,Reference Almeida, Zandonade and Abrantes24,Reference Bueno, Selem and Arêas30–Reference Carneiro, Castro and Juvanhol32,Reference Duarte, Fujimori and Minagawa34,Reference Konstantyner, Taddei and Palma37–Reference Lisbôa, Oliveira and Lamounier39,Reference Matta, Veiga and Baião41,Reference Netto, Priore and Sant’Ana43,Reference Rocha, Lamounier and Capanema54,Reference Rocha, de Abreu and Lopes55,Reference Saraiva, Soares and Santos58,Reference Torres, Braga and Taddei63,Reference Brunken68,Reference Coutinho70) , South(Reference Neuman, Tanaka and Szarfarc3,Reference Zuffo, Osório and Taconeli15,Reference Rodrigues, Mendes and Gozzi56,Reference Santos, César and Minten57,Reference Silla, Zelmanowicz and Mito59,Reference Silva, Giugliani and Aerts61,Reference Assunção, Santos and Barros67,Reference Bortolini and Vitolo71) , North(Reference Granado, Augusto and Muniz36,Reference Muniz, Castro and Araujo42,Reference Neves, Silva and Morais44,Reference Oliveira, Augusto and Muniz46) and Midwest(Reference Brunken, Guimarães and Fisberg29). Five studies were of the multi-centre type(13,Reference Leite, Cardoso and Coimbra17,Reference Silva60,Reference Spinelli, Marchioni and Souza62,Reference Cardoso, Augusto and Bortolini69) and covered all Brazilian regions. The data collected came from residences(Reference Paula, Caminha and Figueiroa2–Reference Leal, Batista Filho and de Lira4,13,Reference Frota16,Reference Leite, Cardoso and Coimbra17,Reference Assis, Barreto and Gomes26,Reference Azevedo, Caminha and Cruz28,Reference Dricot d’Ans, Dricot and Santos33–Reference Granado, Augusto and Muniz36,Reference Levy-Costa and Monteiro38,Reference Lisbôa, Oliveira and Lamounier39,Reference Muniz, Castro and Araujo42,Reference Oliveira, Lira and Osório47–Reference Pedraza50,Reference Pinheiro, Santos and Cagliari53,Reference Santos, César and Minten57,Reference Silla, Zelmanowicz and Mito59,Reference Vieira, do Livramento and Calheiros65–Reference Brunken68) , public day-care centres(Reference Oliveira, Oliveira and Silva14,Reference Zuffo, Osório and Taconeli15,Reference Almeida, Zandonade and Abrantes24,Reference Arcanjo, Santos and Arcanjo25,Reference Brunken, Guimarães and Fisberg29–Reference Camillo, Amancio and Vitalle31,Reference Konstantyner, Taddei and Palma37,Reference Matta, Veiga and Baião41,Reference Novaes, Gomes and Silveira45,Reference Pedraza51,Reference Pedraza and Sales52,Reference Rocha, Lamounier and Capanema54–Reference Rodrigues, Mendes and Gozzi56,Reference Silva60,Reference Vieira, Diniz and Cabral64,Reference Coutinho70) and health services(Reference Assis, Gaudenzi and Gomes27,Reference Carneiro, Castro and Juvanhol32,Reference Magalhães, Maia and Pereira Netto40,Reference Netto, Priore and Sant’Ana43,Reference Neves, Silva and Morais44,Reference Oliveira, Augusto and Muniz46,Reference Saraiva, Soares and Santos58,Reference Silva60,Reference Spinelli, Marchioni and Souza62,Reference Torres, Braga and Taddei63,Reference Cardoso, Augusto and Bortolini69,Reference Bortolini and Vitolo71,Reference Rodrigues72) and almost all works(Reference Paula, Caminha and Figueiroa2–Reference Leal, Batista Filho and de Lira4,13–Reference Leite, Cardoso and Coimbra17,Reference Almeida, Zandonade and Abrantes24–Reference Spinelli, Marchioni and Souza62,Reference Vieira, Diniz and Cabral64–Reference Assunção, Santos and Barros67,Reference Cardoso, Augusto and Bortolini69–Reference Rodrigues72) used the WHO criteria(11) of determination of anaemia (Table 1).

Table 1. Description of the studies included in the present meta-analysis of the prevalence of anaemia in children under 5 years of age in Brazil

(Percentages and 95 % confidence intervals)

To determine the pooled prevalence of anaemia in Brazilian children under 5 years of age, most studies contributed more than one prevalence estimate. This stratification was performed due to the child’s age affecting the behaviour of the prevalence of anaemia in this group.

The pooled prevalence of anaemia in children under 5 years of age in Brazil was 40·2 (95 % CI 36·0, 44·8) %, being 53·5 (95 % CI 49·6, 57·6) % in those under 24 months old and 30·7 (95 % CI 27·7, 34·0) % in those between 24 and 59 months of age. When stratified by regions, it was possible to verify higher estimate of group prevalence of anaemia in the Midwest (45·6 (95 % CI 22·0, 94·7) %) and Northeast regions (42·9 (95 % CI 35·2, 52·3) %), whereas lower prevalence was observed in the Southeast (36·9 (95 % CI 29·5, 46·1) %).

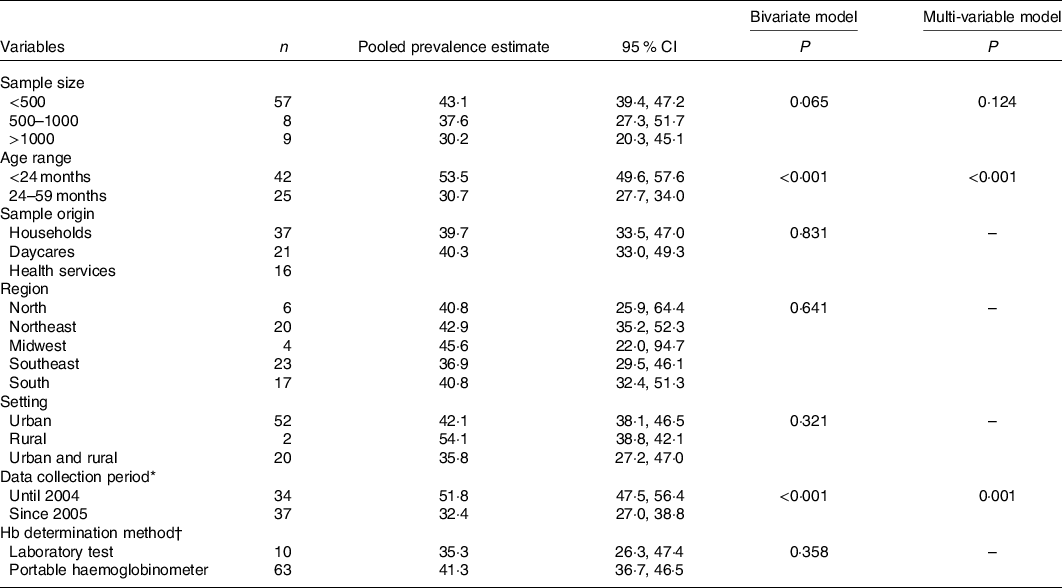

In the analysis of bivariate meta-regression, only sample size, age range of the child and year of data collection were associated with the prevalence rates of anaemia (P < 0·20) and included in the multi-variate analysis. In the final multi-variate meta-regression model, the only variables that remained associated with the prevalence rates were age range and period of data collection. The estimate of group prevalence was higher in children under 24 months old (53·5 v. 30·7 %; P < 0·001) and in studies with data collected until 2004 (51·8 v. 32·6 %; P = 0·001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Association of methodological covariates with anaemia prevalence estimates in children under 5 years in Brazil

(Pooled prevalence estimates and 95 % confidence intervals)

* In three estimates the year of data collection was not presented.

† In one estimate the Hb determination method was not presented.

Further analysis considering the age group stratified by collection period showed a reduction in the prevalence of anaemia in children under 2 years from 61·2 (95 % CI 57·4, 65·2) % to 43·9 (95 % CI 36·5, 57·8) % and in children aged 2–5 years, from 35·3 (95 % CI 31·3, 39·9) % to 27·3 (95 % CI 23·2, 32·0) %, but remaining a serious and moderate public health problem, respectively (data not shown in table).

Discussion

This review presents a broad analysis of studies conducted in Brazil, published from 1985 to 2018, that evaluated the prevalence of Fe-deficiency anaemia in children under the age of 5 and its associated factors. After meta-analysis, Fe-deficiency anaemia in Brazil was characterised as a severe public health problem and was associated with the child age range and the period of data collection of the studies.

Estimated prevalence of iron-deficiency anaemia

The estimated prevalence of anaemia in children under 5 years of age in Brazil in the North, Northeast, Midwest and South regions was classified as a severe public health problem (≥40 %). Only the Southeast, the wealthiest region of the country, had the estimate prevalence classified as a moderate public health problem (38·7 %). Therefore, anaemia is a health condition that still requires attention from the Brazilian health system through the promotion of new strategies for control and monitoring of the effectiveness of the existing public policies.

Regarding the regional aspects, it is important to highlight that, although the estimate of anaemia prevalence in the Midwest has been distinguished as the highest among the regions of the country, this result should be interpreted carefully. Considering that the Midwest region contributed with only four estimates of prevalence in the meta-analysis, we cannot discard the possibility of lower precision in the group estimate due to the low number of estimates available for this region.

Factors associated with anaemia in under 5-year-old children in the meta-analysis

Age of the child <24 months

The age of the child is the main risk factor for anaemia as shown in 47·3 % (n 26) of the studies in this review, being one of the variables that remained associated with the final meta-regression model. From these studies, eighteen identified higher prevalence in the age range of ≤24 months.

The group prevalence of anaemia in children under 24 months of age was classified as a severe public health problem. In children over this age range, prevalence was lower, but anaemia still represented a problem of moderate severity, which should be a reason for concern for administrators and health professionals in the elaboration of their priority programmes.

The WHO affirms that children under 60 months of age, especially those under 24 months, are considered a risk group for Fe deficiency anaemia(1). This is due to the high need for Fe in this age range arising from a fast growth and development, combined with the insufficient intake of this mineral.

Furthermore, a few factors could interfere with Fe absorbency, such as the discontinuance of exclusive breast-feeding, associated with complementary feeding characterized by a monotonous diet, usually with low amounts and/or bioavailability of Fe, insufficient in vitamin C and excessive in Ca(13,Reference Camillo, Amancio and Vitalle31,Reference Carneiro, Castro and Juvanhol32,Reference Gondim, Diniz and Souto35–Reference Konstantyner, Taddei and Palma37) . To encourage breast-feeding and adequate and healthy complementary feeding, in 2013, the Brazilian Ministry of Health established the programme Brazilian Breastfeeding and Feeding Strategy(Reference Levy-Costa and Monteiro38). However, so far, the impact of this action on anaemia prevalence in the country has not been measured.

Another relevant aspects in Brazil are frequent morbidity, such as acute infections, diarrhoea, and intestinal parasitosis, which have a multiplicative effect on the development of anaemia in children, especially in the age range ≤ 24 months(Reference Lisbôa, Oliveira and Lamounier39–Reference Matta, Veiga and Baião41).

Years of data collection starting in 2005

Starting in 2005, we observed the lowest estimate of group prevalence of anaemia in children under 5 years of age when compared with the prevalence in previous years. The period in question coincides with two important public policies for control of Fe-deficiency anaemia in Brazil: the requirement of ‘Fortification of wheat and maize flour with Fe and folic acid’(75) and the establishment of the ‘National Program of Iron Supplementation’(76). However, there are very few and contradictory results of studies that evaluate the effectiveness of these intervention strategies(Reference Novaes, Gomes and Silveira45,Reference Oliveira, Augusto and Muniz46) .

The fortification of wheat and maize flour was established by Resolution RDC number 344, from 13 December 2002(75), and determined the mandatory addition of 4·2 mg of Fe and 150 µg of folic acid in wheat and maize flour, and its effective implementation occurred in April 2005(76). The objective of this action was to reduce the prevalence of anaemia and to prevent the occurrence of neural tube defects during gestation.

Few works investigated the effectiveness of flour fortification in Brazil. In a time series study conducted in Pelotas – RS(Reference Assunção, Santos and Barros77), with a probability sample of children from 0 to 5 years old, analysed anaemia prevalence before and 12 and 24 months after the fortification, but did not observe significant effects on average Hb levels of the pre-schoolers. On the other hand, a literature review that included national and international articles(Reference Oliveira, Osório and Raposo48) demonstrated that food fortification is one of the best processes to prevent nutritional deficiency of Fe all over the world.

Another measure was National Program of Iron Supplementation, established by the Brazilian Ministry of Health through Ordinance number 730 from 13 May 2005(76). Its objective was to prevent and control anaemia through the prophylactic administration of ferrous sulphate in children between 6 and 24 months of age and ferrous sulphate and folic acid in pregnant women and up until the 3rd month post-partum and/or post-miscarriage.

Age v. year of collection of data

Due to the year of data collection and age range remaining in the final meta-regression model, additional analyses were performed stratifying the grouped prevalence of anaemia by age group and year of collection. There was a 1·4 times reduction in the combined prevalence of anaemia in children under 2 years and 1·3 times in children aged 2–5 years after 2004. Despite efforts by the Ministry of Health of the In Brazil, anaemia remains a serious public health problem in children under 2 years of age and moderate in children between 2 and 5 years old.

The prevalence of anaemia in Brazilian children under the age of 5 persists as a serious public health problem, indicating that efforts to combat this nutritional deficiency have not been sufficient to reduce it to acceptable levels. The factors associated with this high prevalence show the multi-causal nature and the role of social inequalities as determining factors for this disease, since a factor classically associated with age remains decisive in the onset of anaemia. Moreover, the programmes and policies developed by the public power were also associated, since studies conducted after policies of food fortification and promotion of food security were effective in reducing anaemia, but not enough to reduce its adequacy.

Furthermore, the current study, because it has no timespan restriction of the collected studies and has strong inclusion criteria in its meta-analysis, ensures that the estimated prevalence of anaemia found is as faithful as possible to the Brazilian reality and provides support for the development of new strategies, programmes and policies to combat anaemia. A limitation of the current study is the limited number of papers published in the Midwest region of Brazil, which may cause alterations or slightly biased results for this specific region.

Conclusions

The efforts made by Brazilian government were successful in the reduction of anaemia in children under 5 years of age in Brazil in the evaluated period. However, prevalence remains beyond acceptable levels for this population group.

It is concluded that Fe-deficiency anaemia remains as an important public health problem in children under 5 years of age in every region of Brazil, except in the Southeast, where it was classified as moderate. The highest prevalence of anaemia occurred in children under 24 months old and in studies with data collected before 2005. Furthermore, a continuous evaluation of the effectiveness of existing programmes is necessary to address its status.

Acknowledgements

We thank all authors who we contacted and sent us their articles to compose this review.

We also thank the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico for the financial support (grant number 44·0875/2017–0).

V. N. C. S made substantial contributions in the conception and design of the work, as well as actively participated in data acquisition, statistical analysis and data interpretation. It also contributed to the writing of the article, critical review and approval of the final version to be submitted. C. A. C., P. C. A. F. V., S. I. O. C., M. T. B. A. F., I. L. C., L. L. P., N. A. C. C., S. C. C. F. and A. K. T. C. F. participated in the acquisition of data and writing of the manuscript, as well as in the approval of the final version to be submitted. E. I. S. M. participated in the data acquisition, interpretation of results and writing of the manuscript, as well as in the approval of the final version to be submitted.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.