Introduction

The inevitability and omnipresence of stress requires coping to ensure individual health and social functioning.Footnote 1 National leaders must cope with stress and deal with the negative emotions triggered by uncertainty of conflict, economic crises, natural disasters, or pandemics in the process of policymaking. The public tends to be on the receiving end of both the stressful situations generated by international politics and its leaders’ attempts to cope.

The discipline of International Relations (IR) recognises the centrality of stress. However, how people cope with the exigencies of international politics is under-theorised. How do political actors, individual decision-makers, and collectives cope with both sudden crisis and long-term change? Furthermore, considering political decisions or collective reactions to stress in international politics, whose coping matters, and under what circumstances?

This article provides an innovative theoretical framework of coping to answer these important and unaddressed questions by anchoring psychological studies on coping mechanisms to the literature on theorisation of emotions in IR. We argue that intersubjective appraisal of urgency from everyday stressors induced by powerful political forces triggers a process that requires individual coping. How individuals deal with stress follows the logic of emotional balancing. This matters under conditions in which emotional well-being orders us to challenge established political arrangements. Through circulation of coping responses, individual coping is scaled up to collective coping, resulting in the formation of affective communities and transforming individual stress responses into collective agency.

The main literature to which this article contributes is the theorisation of emotions in IR. First, it teases out a therapeutic approach within the emotional turn of IR to establish the relevance of emotional well-being for international politics. Secondly, by answering whose coping matters in IR, the authors posit that coping processes constitute conditions for political possibilities, and that individuals’ coping with stress is imbued with collective dynamics and implications. Lastly and relatedly, the coping framework this article proposes contributes to the discussion of levelling up emotional experiences. Primarily, this work adds circulation of coping responses to the existing scaling-up pathways and further conceptualises the emergent collective, what Hutchison called ‘affective communities’,Footnote 2 in which individuals are bound by emotional understandings of the stressor and the need to cope together.

In addition to the theoretical contribution, this paper presents an empirical contribution through its choice of an overlooked case study: Hong Kong’s state-building process. The possibility of independence for Hong Kong was erased in 1972 by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the General Assembly of the United Nations,Footnote 3 when the PRC and the United Kingdom (UK) determined Hong Kong’s future as a Chinese Special Administrative Region in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration. The political compromise between the former British coloniser and the current sovereign master residing in Beijing interweaves the bilateral agreement with the need to cope by Hong Kong residents. This is epitomised in the words of Deng Xiaoping, who said that the Sino-British negotiations in the 1980s would ‘put hearts at ease’.Footnote 4 The founding of the Hong Kong National Party and the fact that 40 per cent of surveyed Hong Kongers did not rule out the idea of independence shows the failure of the British and Chinese governments to put Hong Kongers’ hearts at ease.Footnote 5 On the collective level, Hong Kong illuminates the sub-national level’s discontent and disagreement with the imposition of national identity by a powerful sovereign.

Using primary data from surveys and 80 interviews collected in the span of eight years, our findings provide a rare documentation of Hong Kongers’ efforts to sustain emotional well-being through a state-building project in defiance of an international treaty. The story of Hong Kong is not only intrinsically international, but also emotional, because it shows how ‘seemingly small-scale emotional interactions can become amplified into globally visible assemblages’.Footnote 6

Theorising coping in IR

The theory section first charts IR’s existing interest in coping, namely political psychology and ontological security. There is consensus in these two literatures that coping constitutes conditions of political possibilities, but they diverge on the unit of analysis: political psychology is primarily concerned with individual coping, while ontological security accentuates collective coping. This divergence points towards two unaddressed yet critical questions: how do individuals and collectives cope with stressful situations, and whose coping matters under what circumstances. This article’s engagement with the main literature, theorising emotions in IR, sheds light on the therapeutic approach, which notices the relevance of individuals’ emotional well-being to the configuration of global politics. Pinpointing the scaling-up process from individual to collective coping, the authors add the circulation of coping responses as an additional pathway for collective affective experience. The consequence of collective coping is the formation of Hutchison’s affective communities, which bind individuals with emotional representations and understandings. Affective community’s relevance to the coping framework resides in its ability to capture the transformation of individuals’ emotional well-being into collective agency, recognising and appreciating the transnational dimension of local experiences.

The constitutive relationship between coping and international politics

The existing IR literature acknowledges the omnipresence of coping in various units of analysis. Focusing on the individual decision-making process, foreign-policy makers need to ‘cope’ with perceived threats.Footnote 7 When it comes to state identities, states cope with negative treatment, such as stigmatisation.Footnote 8 The international community is also expected to ‘cope’ with rising powers such as China.Footnote 9 The act of coping is political, yet coping is largely treated as an empty verb that requires no further theorisation. For instance, the statement that foreign-policy makers ‘cope’ with perceived threats is more concerned with the perception of threat rather than how the process of dealing with threats can generate those perceptions.

A rare exception that examines coping in IR is the stress-coping-choice model in political psychology. Brecher locates coping mechanisms in a causal chain to explain individual and/or group decision-making.Footnote 10 Coping is considered as an intervening variable that mediates the causal relations between the perception of stress and political decisions. The political consequence of coping is to identify and invent ‘alternative options’ that inform the final policy outcome.Footnote 11

Not only is coping relevant for the decision-making process, but the research community on ontological security also recognises the constitutive relationship between coping and state identities and behaviours. Coping mechanisms such as routine, avoidance, and resort to humour are extracted as key to ontological security-seeking behaviours.Footnote 12 Situating anxiety and uncertainty management at the heart of security studies,Footnote 13 Mitzen highlights that different modes of anxiety management generate varying outcomes.Footnote 14

These two distinctive research communities converge in the acknowledgement that the coping process constitutes conditions of political possibilities in the form of alternative narratives about state identities and policies pursued by national leaders. However, the literature on the psychology of coping, introduced by Richard Lazarus and Susan Folkman, is missed by political psychology’s focus on the psychology of emotions and ontological security’s primary preference of the sociology of emotional management.Footnote 15

A re-routing of coping in IR to the psychological research on coping helps clarify two unaddressed questions: first, how do individuals and collectives cope with stressful situations, be it sudden crisis or slow-burning political change? This is an important question because individuals cope for their psychological and physiological well-being,Footnote 16 so the extrapolation of coping to the state level could be problematic, as states do not have a ‘body’ to experience stress and do not feel the need to cope. Relatedly, the second question concerns whose coping matters in international politics, and under what circumstances individual coping generates collective dynamics.

Problem- and emotion-focused coping

This paper consults Richard Lazarus and Susan Folkman’s groundbreaking works on coping in psychology to clarify the constitutive relationship between individual coping and conditions of political possibilities in IR. Lazarus and Folkman define coping as ‘constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person’.Footnote 17 The function of coping is more than the seeking and evaluation of information, as compellingly outlined by Brecher in the above-mentioned stress-coping-choice model. More importantly, it is about the restoration and maintenance of equilibrium under stress,Footnote 18 which broadens the scope of coping as understood in ontological security from repression of negative emotions to balancing affective experiences.

Folkman categorises two types of coping based on its function: problem-focused and emotion-focused.Footnote 19 Problem-focused coping refers to the management and alteration of the problem. In Brecher’s model, this involves information search and absorption, consultation, discussion forums, and the consideration of alternatives in times of crisis.Footnote 20 Emotion-focused coping, on the other hand, is ‘directed at managing or reducing emotional distress’.Footnote 21 Mitzen’s conceptualisation of anxiety avoidance by the European Union in confronting its colonial past and war memories epitomises the emotion-focused coping process.Footnote 22 Adler-Nissen and Tsinovoi’s compelling analysis of humour as a coping mechanism is another example of emotion-focused coping to handle international misrecognition.Footnote 23 The definitional differentiation does not suggest incompatibility of problem- and emotion-focused coping. Rituals, for instance, both calm emotional distressFootnote 24 and reframe ‘past suffering’ to solve problems.Footnote 25

The differentiation of problem- and emotion-focused coping in psychology bears direct relevance to IR for three reasons. First, it offers a framework to trace the constitutive relationship between coping and conditions of political possibilities. Second, emotion-focused coping pinpoints the missing micro-level actorhood of anxiety management in the ontological security literature. Third, emotion-focused coping foregrounds the overlooked logic of emotional equilibrium in shaping individual decisions and collective agency. The underpinning logic of coping is achieving an emotional equilibrium.Footnote 26 Stress disrupts individual emotional balance and requires readjustment.Footnote 27 Failure to balance emotions is a matter of mental health and generates physiological repercussions.Footnote 28 Psychological defence mechanisms amend an individual’s experience of emotions through ‘internal control structures’, which alter the perceived reality.Footnote 29 This means the logic of emotional equilibrium may override the choices motivated by strategic calculations.

Our working definition of coping in the IR context is a cognitive and behavioural adaptation, automatic or conscious, to manage objectively stressful or subjectively unbearable situations. Mapping political psychology and ontological security to the psychological typology of coping creates a false one-to-one relationship that aligns individual coping with the problem-focused and collective coping with the emotion-focused. Our engagement with psychology is not to parachute ‘the psychology of emotions’ into IR that applies ‘emotional categories’ to world politics.Footnote 30 Instead, we are interested in how we think about coping in International Relations.

The therapeutic approach in theorising emotions in IR

We anchor our theory of coping to the literature on emotions in IR, originating with Crawford’s seminal article, which ushered an ‘emotional turn’ into the discipline. Yet her legacy in pointing out the significance of individuals’ emotional well-being to international politics has so far been less appreciated. With the ‘emotional turn’ of IR comes a ‘therapeutic’ approach that appreciates an individual’s emotional well-being in the grand process of international politics. This body of literature is sensitive to the two questions mentioned above.

The question of how subjects cope with stress echoes the debate on the role of the body in emotions IR literature, between ‘bodily based micro approaches’ and macro approaches that foreground social, cultural, spiritual, and normative dimensions of emotion.Footnote 31 McDermott’s somatic account grounds emotional experiences in the physicality of bodies, recognising ‘the primacy of the physical body in both experiencing and conveying emotions’.Footnote 32 Whereas it is contestable whether the primacy of bodies should be reflected in the definition of emotions, the somatic approach aligns with the psychology of coping and pays more attention on the physiological aspect of individuals’ emotional well-being. Individuals need to cope, and the body is where coping as a psychological process begins.

The centrality of individual emotional well-being in our coping framework does not turn a blind eye to the social and cultural characters of emotions. Individual coping is inherently a social and cultural process in which individuals become interdependent through common goals.Footnote 33 ‘Structural discrimination … and collective disadvantages’ are also ‘important contextual demands with which people cope’.Footnote 34 Therefore, individual coping matters to international politics under conditions in which our emotional well-being orders us to challenge established political arrangements that require conformity to rules and norms. How we feel in reaction to political events may be subject to culturally and socially specific scripts.Footnote 35 However, how we deal with emotions follows a different script, one of emotional balancing and equilibrium. Evidence from affective neuroscience shows a ‘pre-social, pre-discursive’ dimensions of affect.Footnote 36 The counter-entropic neural disposition generates a ‘defensive understanding of selfhood’ that prioritises the attainment of ‘emotional quiescence’ over seeking perfect knowledge.Footnote 37

On the premise that ‘individuals are activists on behalf of their own well-being’,Footnote 38 our emotional well-being may order us to confront rules and norms and withdraw us from emotional labourFootnote 39 when emotions are managed, not necessarily balanced. The difference between managing and balancing emotions lies in the relationship between the self and external environment. When we manage emotions, we regulate ourselves to fit in specific circumstances – for example, we force a smile and create narratives to keep our job and maintain sanity.Footnote 40 Yet when we balance emotions, we negotiate with the wider environment, and radical changes are possible. Those moments are ‘emotional ruptures’ that set up alternative political options.Footnote 41

This brings us to the ‘therapeutic’ approach within the theorisation of emotions in IR. Emotional responses, according to Crawford, are partly based on individuals’ appraisal of ‘an event’s significance for their well-being’.Footnote 42 The political consequence is political elites’ tendency to distort past events and decisions to ‘feel good about’ their choices.Footnote 43 This is an important intervention to revisit the instrumentalist take that treats leaders as deliberate and strategic players ‘inherently capable of rising above the emotions of the masses’Footnote 44 – not to mention that unintentionally transmitted affective information may undermine orchestrated strategic communication in high politics.Footnote 45

Individuals’ neural dynamics of emotions and regulation also have collective implications, particularly when it comes to emotional attachments.Footnote 46 In the context of trauma, collective narratives that help individuals ‘heal the wounds of the past’ are vital for societies and groups to build peaceful relationships with others. Hutchison speaks of the concept of ‘working through’ to conceptualise how communities make cognitive and emotional sense of communal trauma.Footnote 47 Different from ‘moving on’, ‘working through’ trauma is simultaneously therapeutic and an ‘active political process’ in which communities engage with suffering and memories ‘in a way that prompts a questioning of the very mindsets and structures (of power)’.Footnote 48 This position poses a direct question to ontological security’s state-centric inclination by probing whose anxiety deserves narratives of the sense of self, which leads to the next section.

Distributive politics of individual coping

The question of whose coping matters to IR concerns the distributive aspect of individual coping. We intuitively understand that individual coping by leaders in eminent positions has major consequences for international politics, yet the emotional well-being of ordinary citizens also has the potential for global ramifications. This is illustrated by the Fridays for Future movement, which originated from the individual coping responses to depression and climate anxiety by a Swedish teenager.Footnote 49 Yet even when the urgency is obvious and when facing a similar stressor such as a terrorist attack, coping responses can vary significantly. In 2001, George W. Bush produced visibly different enemy narratives and security measures from the Spanish public’s emotional response to the train bombings in 2004, which resulted in demonstrations and ‘absence of public hostility toward ... the Muslim minority’.Footnote 50 These examples showcase our position that the both leaders’ and the citizenry’s coping matters and may generate different political outcomes.

The examples also illustrate that, both the exigency of a stressor and its relevance which prompt coping responses, are negotiated. Our coping framework covers the overlooked situation of a slow-burning crisis in which urgency is intersubjectively agreed, instead of objectively imposed. An example of intersubjective urgency can be observed in the storming of the US Capitol in January 2021. Then-President Trump manufactured a stressor – electoral fraud and claims that the 2020 election had been stolen – evoking negative emotions such as anger and fear among his supporters. Trump subsequently offered emotional balancing through problem-focused coping by calling them to attend a protest in Washington. The scaling up from individual to collective coping has the potential to encourage ‘strategic political behaviours’Footnote 51 in which leaders capitalise on the need to cope. How leaders cope with stress is nevertheless not automatically translated into collective coping. In fact, collective coping requires individuals to ‘enlist the assistance of ingroup others in a way that maintains sensitivity towards the wellbeing of those others’.Footnote 52

From individual to collective coping

Scaling up from individual coping to the collective level takes place via representation to ‘establish the emotional fabric that binds people together’.Footnote 53 The levelling up of emotions can be unintentional, as in the case of ‘emotional contagion’, which is an automatic process.Footnote 54 It can also be intentional and strategic by matching political strategies with others’ affective states (calibration), eliciting emotive responses for political gains (manipulation), modifying the ‘underlying structure of affective dispositions and concerns’ (cultivation), and performing an emotional display to influence the audience (display).Footnote 55

Our approach aims in the direction of representation and interpretative methods but takes a slightly different route by exploring the possibility of self-representation. A quick detour to Lazarus’s differentiation between primary and secondary appraisal helps us to illuminate what is represented, shared, and circulated when coping is projected from the individual to the collective level. Primary appraisal concerns individuals’ interpretation of the relevance of given circumstances. Secondary appraisal refers to individuals’ ‘options and prospects for coping’.Footnote 56 Interviews, questionnaires, and focus groups are conducted to collect individuals’ interpretations.Footnote 57 Reflections from individuals and self-reported narratives, utilised in psychology research, may help literature on emotions in IR narrow the existing ‘gap between a representation and what is represented therewith’.Footnote 58

Individual coping is levelled up through circulation of coping responses, rather than emotional states. Three pathways, outlined by Hall and Ross, clarify directions of scaling up. It can be a top-down process driven by political elites, such as Donald Trump’s Capitol Hill storming. The bottom-up process is also relevant when individuals enlist social assistance as coping resources, as in the case of Greta Thunberg. Horizontal circulation of a sense of urgency and the need to cope provide moments to transform an individual’s effort to maintain emotional well-being into collective action, such as the Spanish public’s response to the Madrid train bombings. Coping responses circulate (but are not always copied directly) and offer additional resources for individuals that later form their coping repertoires. This intervention therefore adds coping responses and narratives to Hall and Ross’s checklist of what is shared and circulated. Circulation of coping responses imbues individuals’ emotional balancing with collective dynamics. Scaling up occurs as coping responses are circulated and shared to address a common stressor, elevating individual coping to collective coping. Alongside the cognitive and behavioural adaptations emerges what Hutchison theorises as ‘affective communities’.Footnote 59 Through representation, individuals are not only bound ‘by shared emotional understanding’Footnote 60 of the stressor, but also the need for collective coping. Affective communities as a concept is emancipatory because it provides sites to appreciate the weaving of emotional meaning for communities beyond nation-states. In this sense, affective communities are the outcome of collective coping and a manifestation of collective agency, as individuals’ dealing with stress is reappraised as part of a bigger political reconfiguration.

This article proposes a coping framework in which intersubjective appraisal of urgency from everyday stressors triggers the levelling up from individual coping to the collective level. Circulation of coping responses, problem-focused and/or emotion-focused, binds individuals to affective communities. Our theoretical contribution identifies a therapeutic approach within the ‘emotional turn’ of IR, and we use the innovative coping framework to explore how individual well-being is transformed into collective agency. Our conceptual framework of coping contributes to the therapeutic turn by providing a much-needed vocabulary and pinpoints mechanisms of ‘working through’ and ‘moving through’ stressful situations. By doing this, we demonstrate that not only are emotions constitutive of global politics, but also that dealing with emotions engenders conditions for creativity in IR.

Methodological note

Coping research relies on self-reported information to capture and measure coping strategies and their effectiveness through interviews, questionnaires, and focus groups.Footnote 61 The introduction of coping to International Relations therefore offers important methodological challenges and opportunities. The main question lies in the ontological compatibility of self-reported affective experiences, as emotions are intrinsically social.Footnote 62 Instead, emotions are examined via representation and communication and through discourse.Footnote 63 The communicative process is highlighted, as emotional expression is mediated and regulated.Footnote 64

Yet treating self-reported information from individuals as narrativesFootnote 65 offers a methodological opportunity to link affective IR and psychology approaches. Although an individual’s narrative does not allow researchers to ‘get inside the[ir] head’,Footnote 66 their stories provide valuable indirect insights into how they ‘make sense of emotional experience and imbue it with meaning’.Footnote 67 Furthermore, it may contribute to the debate about agency in the study of political emotions by carving out an interpretive space for local agents.Footnote 68

Our research design echoes Holmes’s advocacy of a ‘triangulation of methods’ to study emotions.Footnote 69 The motivation of our research design is the recognition of the power dynamics between researchers and the agents we study. The triangulation allows us to identify affective experiences, trace how they are coped with, and understand how and why certain emotions are communicated. As coping processes entail both individual and collective levels, this study may provide new ideas to address the challenge of capturing the ‘scaling-up’ process at the intersection between individual emotions and affective dynamics.

We adhere to the established practice in the field of using a case study.Footnote 70 Our case study is the mainstreaming of the Hong Kong independence issue, which showcases the political consequence of coping. Our empirical investigation involves self-reported information via surveys and open-ended interviews to invite our respondents to reconstruct their emotional landscape and examine the coping process on the individual level. Respondents’ accounts of the everyday are essential to understanding how stress is experienced and subsequently dealt with. We distributed a survey to 60 localistFootnote 71 leaders in Hong Kong and received 32 valid responses (response rate = 53.3%). Questions in the survey were open-ended and invited respondents to offer their own narrative of their affective experiences. The survey was limited to studying patterns rather than explaining the emergence and evolution of emotions.Footnote 72 Findings from our survey were closely monitored and followed up by interviews. We contacted all groups that fit a broad definition of localism. Between 2012 and 2020, we conducted 80 in-depth interviews, in English, Mandarin, or Cantonese, with 60 localist leaders (response rate = 97%). In the interviews, we initially let localist leaders freely share the process of their political awakening before steering them towards their understanding of the impact of major events on their emotional situation. The interviews sought to establish a nuanced analysis of how leaders have coped with disruptions to their emotional equilibrium and how they communicated coping strategies to their followers. We re-interviewed several leaders over the years. Our longitudinal study allowed us to gain trust and access to leaders’ reflections of their affective experiences and explanation of their coping process. Due to the political sensitivities of the topic of Hong Kong independence, we decided to anonymise all interviewees.

Our methodological contribution, in this sense, is to return agency to research subjects. The final methodological element focuses on emotion representation: a content analysis of all social media posts by 47 localist leaders shared during the first 48 hours of the 2014 Sunflower Movement in Taiwan. Data was collected from public and private (friends/supporters) Facebook posts of leaders. Our interviews confirmed that all localist leaders use the social media platform Facebook as their primary and often only tool to disseminate information, communicate with the public, and mobilise supporters. Content analysis examined the symbolic qualities of texts through ‘qualitative interpretation’ in which the researchers’ voice participates in the dialogue with research subjects.Footnote 73 We triangulated the self-reflected emotions of political leaders with those communicated and represented through their words and images.

Findings

The idea of Hong Kong independence is not a cognitive novelty, but for decades, it was confined to sporadic op-eds and demands by isolated local elites.Footnote 74 Indeed, independence was not even the aim of Hong Kong’s student movement in the early 1970s, unlike other anti-colonial movements in Asia.Footnote 75 After the transfer of sovereignty from the British to the Chinese, independence was treated as political taboo: intellectually available, but normatively unacceptable because of its challenge to PRC sovereignty over Hong Kong. Anyone openly advocating for Hong Kong independence was seen as ‘secessionist’ by the Chinese government and as a ‘radical’ by the political establishment in Hong Kong.Footnote 76

After 1997, Hong Kong retained its own political and economic system under the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ framework. The pro-democracy movement focused on safeguarding Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy as guaranteed in the mini-constitution. For decades, the main political cleavage in the territory between the pan-democratic camp and the pro-establishment (or pro-Beijing) camp was the speed of democratisation and realisation of universal suffrage.Footnote 77 The most daring challenge to the regime in Beijing was a year-long civil disobedience campaign to pressure the Chinese government for democratic changes to the Hong Kong electoral system.Footnote 78 Neither the pan-democrats nor the pro-Beijing camp ever questioned that Hong Kong was a part of China, rendering the option of independence a non-issue.

It was not until the localist movement in the 2010s that the issue of Hong Kong independence was openly advanced.Footnote 79 The challenge to the status quo and critique of existing political camps defined localism as the ‘third force’ in Hong Kong’s political landscape. Initial theory building on localism envisioned Hong Kong as a city-state, undermining the sovereignty claimed by the PRC over Hong Kong.Footnote 80 A further step was taken with the creation of the Hong Kong National Party in 2016, which organised the first ever independence rally that attracted 10,000 people.Footnote 81 Expressions of ‘independence’ and the ‘Hong Kong nation’ subsequently entered the political establishment when localists referenced them during their oath-taking ceremony in the city’s legislature.Footnote 82 Within a very short time, the idea of Hong Kong independence was mainstreamed. Here, mainstreaming is defined as a discourse quickly shifting from marginal circles ‘to more central ones, shifting what is deemed to be acceptable or legitimate in political, media and public circles and contexts’.Footnote 83 Hong Kong independence was extensively debated in the media. The term ‘Hong Kong independence’ in Hong Kong’s seven best-selling newspapers increased by 1,380 per cent between 2011 and 2016 (from 90 mentions in 2011 to 1,332 in 2016).Footnote 84 Up to one-fifth of the population now supports Hong Kong independence, testifying to considerable public support.Footnote 85 Political groups advocating independence performed so well in electionsFootnote 86 that they pushed individuals and groups across the localist spectrum to take a clearer position on Hong Kong’s future and to support self-determination.Footnote 87 The sudden popularisation of independence was a remarkable achievement in comparative perspective,Footnote 88 given the historical legacies, as well as political and geo-strategic realities, making it an unexpected political choice to the ruling elites both in Beijing and Hong Kong.

Intersubjectivity of urgency: Interpreting mainlandisation as an essential threat

Mainlandisation refers to the accelerated socio-economic integration with the mainland.Footnote 89 In particular, Hong Kongers felt overtaken by the mass tourism and immigration from China. The new Chinese arrivals were perceived to be instruments in a strategic plan of the Chinese government to change Hong Kong into a mainland city.Footnote 90

The Hong Kong government admitted that the ‘actual impact on the livelihood of the community’, particularly in densely populated neighbourhoodsFootnote 91 and the stretched transport facilities ‘exceeded the public’s psychological acceptability’.Footnote 92

The stressor of mainlandisation generated negative emotions such as anger, fear, contempt, and despair. Our interview data shows that a series of low-intensity emotional encounters accumulated into a widely recognised stressful situation in which Hong Kong was perceived to face an existential threat.Footnote 93 The Hong Kong government’s inaction fuelled the feeling that China was a new ‘coloniser’ in Hong Kong.Footnote 94 The combination of everyday stress and the lack of response from the authorities induced a high level of frustration and fear.Footnote 95 Mainlandisation was experienced as a question of ‘life and death’.Footnote 96

Fear amplifies the intensity of everyday stress through the associated sense of lacking control.Footnote 97 Thus, despite its weak action tendency, fear disrupts individuals’ emotional equilibrium, triggering the coping process as a way of self-protection.Footnote 98 While localists coped with fear and looked for effective coping responses, a dramatic political event across the Taiwan Strait gained significant attention in Hong Kong: the so-called Sunflower Movement. This demonstration included a 23-day-long occupation of the legislature that successfully halted the enforcement of a controversial trade agreement between China and Taiwan. Taiwanese resistance to increasing Chinese influence was of direct relevance to the stressful situation experienced by localists in Hong Kong.

Circulation of coping responses

The Sunflower Movement in Taiwan possesses cognitive and emotional significance to localists because it inspires the secondary appraisal in individual coping that concerns options and prospects of coping. Taiwanese storming into the legislature vindicated localist advocacy for direct action, as localist leaders sought moral support to justify their own resistance. Direct action to confront authority is problem-focused coping. The Sunflower Movement also facilitated emotion-focused coping with the realisation that Taiwanese and Hong Kongers have a common stressor: the China factor.Footnote 99 The fear of China felt in Taiwan echoed the feelings of Hong Kongers, and the thrill of the successful occupation provided hope. A left-wing localist lawmaker reflected: ‘It [the Sunflower Movement] brings me hope. I wonder, why can’t it happen in Hong Kong? No one here has been that brave.’Footnote 100 Through the balancing of fear, Hong Kong activists also experienced disappointment and anger towards the lack of determination of Hong Kongers.

Witnessing the images and texts of the Sunflower Movement, Taiwanese coping responses circulated in Hong Kong and provided new coping narratives and repertoires. Localist leaders also reflected on the meaning of anger and reinterpreted its relationship with action through emotion-focused coping. Anger was recognised as an emotion that could embolden, for it urges people ‘to do some of the things that remove or harm its agent’.Footnote 101 Bowlby argues that two types of anger exist: a dysfunctional ‘anger of despair’, close to the inflexible state of rage, and a functional ‘anger of hope’, which contains a constructive element in its action tendency.Footnote 102 The Sunflower Movement inspired angry localists in Hong Kong to channel their anger into meaningful action, sowing the seeds of an anger of hope. The liberation of Hong Kong’s localist leaders from the anger of despair took place during Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement.Footnote 103

The accentuation of a positive reinterpretation of anger set the scene for the Umbrella Movement, Hong Kong’s own resistance against Chinese influence. In late August 2014, the Beijing government rejected genuine democratic change for Hong Kong. Angry university and secondary-school students immediately launched a comprehensive class boycott. Their anger and despair intensified and led to actions that ushered in the large-scale occupation and civil-disobedience movement. Participation in the Umbrella Movement qualifies as problem-focused coping, which aims to address the cause of negative emotions by taking direct action. A pro-independence localist leader explained that ‘the reason for people to join is simply because … they can feel the problem’.Footnote 104 A localist commentator pointed out the quasi-therapeutic qualities of the Umbrella Movement, which temporarily helped with his chronic depression.Footnote 105

Various coping responses enable individuals to reappraise a stressful situation and provide ways to alter it. Taiwan’s social movements and political developments became increasingly relevant to people in Hong Kong through the recognition of a common stressor – influence from China. Moreover, the reappraisal process resulted in Hong Kongers shifting their attention away from Beijing towards Taiwan, as this reorientation contributed to their psychological well-being. Reappraisal is primarily a consequence of emotion-focused coping. The Taiwanese achievements countering Chinese influence demonstrated that the fate of Hong Kong could also be decided by its people.

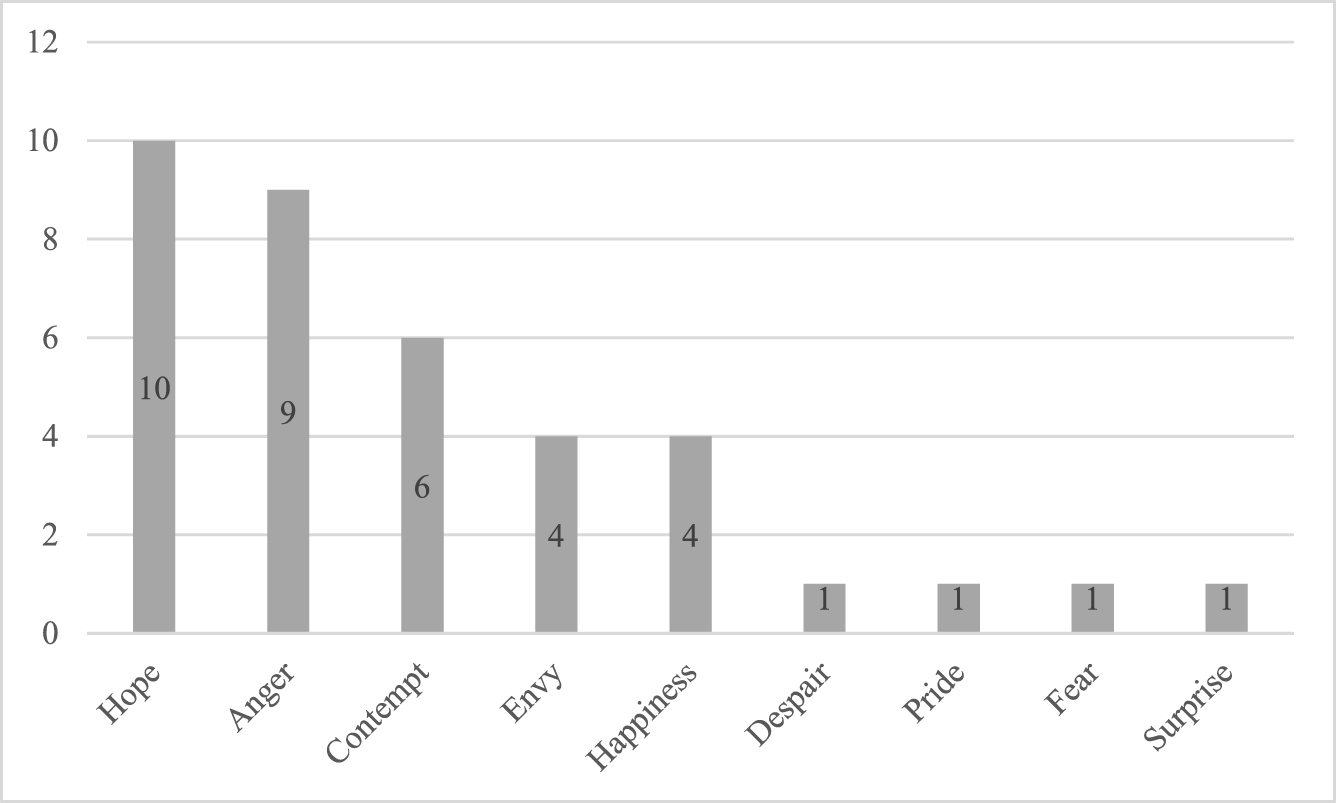

Following reappraisal, localist leaders communicated emotions (shown in Figure 1) together with their coping responses to the public via social media. Dominated by emotion-focused coping, Hong Kong activists steered their attention away from Beijing, as this reorientation contributed to their psychological well-being. The emotion-focused coping responses were represented and shared by localist leaders through social media and direct communication with followers. Negative emotions targeted China and passive Hong Kongers, while Taiwanese students’ occupation of their parliament elicited positively valanced emotions such as ‘happiness’ and ‘pride’. A localist commentator posted on Facebook that his ‘politics-induced depression disappeared as politics exploded into everyday life’.Footnote 106 In his interview he elaborates: ‘In everyday life I feel my survival is meaningless. During the Umbrella Movement, I felt pumped because I found my life meaningful, and I felt hope.’Footnote 107 Through the open communication of coping responses and negative emotions, individual coping is elevated to the collective level. It underlines coping as a communal process, which involves shared emotional understanding of the situation and collective efforts.

Figure 1. An overview of communicated emotions during the Sunflower Movement by localist leaders on Facebook.

Despite Hong Kong localists employing various coping responses, the stressor of mainlandisation remained and continued to generate negative emotions. Negative emotions rose again after the end of the Umbrella Movement in 2014. When police cleared the occupation sites after 79 days, the government refused to make any concessions on questions of democracy and universal suffrage. The failure of the Umbrella Movement amplified the severity of external stress (i.e. mainlandisation) and dealt a serious blow to the psychological well-being of participants. Localist leaders recalled intensified anger, fear, and despair.Footnote 108 The link between individuals’ psychological well-being and the city’s fate foregrounds the emergence of affective communities.

Emergent and adaptive affective communities

Intensified negative emotions could no longer be addressed through previously employed coping responses and thus required different approaches. A localist leader and radio host observed that ‘the entire society is angry, restless and these emotions have no outlet’.Footnote 109 Localist activists imbued Hong Kong society with affective qualities, as individually felt stress became situated in a communal context, and Hong Kong as a political community became populated with emotional meanings. Emotion-focused coping therefore became an important coping response for localists, which shaped the boundaries of the emerging affective community.

Individual venting of anger and contempt fuelled anti-China sentiments, and localists were accused of racism and xenophobia.Footnote 110 Localists’ anger towards the pro-democracy camp over a perceived weakness vis-à-vis China became expressed in harsh attacks that intensified tensions between the groupsFootnote 111 and demarcated community boundaries. ‘Despair [was] so widespread in Hong Kong’Footnote 112 that localist leaders deployed emotion-focused coping, which prioritises balancing negative emotions over changing the stressful situation. Classified as a dispiriting emotion, despair initially does not bode well for engendering changes to the status quo.Footnote 113 However, the future-orientation of both hope and despair allows room for the reinterpretation of the negative emotion: ‘we can hope even when we are helpless to affect the outcome’.Footnote 114 Localists realised that emotion-focused coping may unleash destructive energy. An anonymous leader of the radical localist organisation Valiant Frontier worried about the fate of the groups’ pre-teenage members. He reflected that ‘if you are filled with emotions and let emotions drive your action, then (our action) would just be a riot, not a revolution’.Footnote 115

Consequently, localist leaders deployed problem-focused coping to counter potentially problematic socio-political consequences of emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping helps individuals create a hierarchy of priorities. Several localist leaders used meditation as an individual coping response,Footnote 116 which was communicated to supporters as a ‘way of pacifying the mind, cooling them down’, combined with an ‘interpretation of … China–Hong Kong relations’.Footnote 117 Here, the coping response offered the first radical departure from the status quo thinking on how to achieve democracy in Hong Kong. A pro-independence localist leader disagreed with the pan-democrats’ objective to ‘build a democratic China’Footnote 118 to guarantee democracy in Hong Kong. This cognitive re-sequencing of democratisation was also proposed by a grassroots localist activist.Footnote 119 He argued that it is necessary to ‘de-colonise’ Hong Kong from Chinese rule first and only afterwards explore democratisation. His reorientation towards the issue of independence suppresses competing activities (i.e. the mission of building a democratic China).

Different coping responses also yielded a divergent sense of belonging within Hong Kong. For decades, thousands of Hong Kongers commemorated the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre with an annual candlelight vigil on 4 June. Localists challenged the form of these commemorations organised by pan-democratic groups.Footnote 120 The discussions about 4 June illustrate localists’ interactions and the formation of a community shaped by different emotional understandings of the vigil. For left-wing localists, 4 June is an important emotional connection to the fight for the democratisation of China.Footnote 121 Pro-independence localists ‘disagree with the patriotic sentiment’ of the vigil.Footnote 122 The lack of ‘emotional ties to China’ means a ‘focus on Hong Kong democracy first’.Footnote 123 Solidifying the borders of an affective community that is radical in its contempt towards China and pan-democrats restricted even key localist figures: ‘I couldn’t really talk about my sympathies towards China, and I avoid talking about it.’Footnote 124 The result is a reworking of the compassion towards mainland compatriots by ‘remembering [4 June] in a humanitarian manner’.Footnote 125 The debate over the commemoration exemplifies how our emotional well-being may order us to disobey well-established ritual and political habit.

Problem-focused coping allowed localist leaders to reappraise the significance of the Chinese government in Hong Kong’s democratisation process: it became ‘unrealistic to expect Beijing to give universal suffrage or democracy to us’.Footnote 126 The deadlock could only be broken by selective ignoring of the threat from China.Footnote 127 Fixating on the reaction from the Chinese government would only fuel ‘hopelessness and hatred’.Footnote 128 Thus, localists’ abandonment of the ‘democratic China’ future was followed by an alternative imagination of Hong Kong’s future. Ignoring reactions from China, localists embraced Hong Kong independence as the alternative that brought hope,Footnote 129 as the ‘only way out’ for Hong Kong.Footnote 130 In other words, Hong Kong independence became not only a preferred future, but also a symbol of hope to localist leaders. The disregard for Beijing was complemented by localists’ rising interests in the democratisation of Taiwan and shared emotional attachment to the issue of independence. The newly weighted significance of Taiwan vis-à-vis China during localists’ coping processes enabled the articulation and reasoning of the choice of Hong Kong independence. Localist leaders aimed to ‘inspire followers with a vision of state-building’.Footnote 131 A localist lawmaker elaborated links between the pursuit of Hong Kong independence and empowerment on a personal level, via steering away from the ‘tragedy and loss’ of not achieving democracy towards a new objective, ‘an optimist picture’ that ‘the Hong Kong public feels we can win’.Footnote 132 The importance of the independence issue therefore lies in its function more as a consensus on how to cope rather than as a detailed political plan. The emotional significance of independence to this community is captured by localist leaders: ‘we have no other choice … independence is the solution for decolonisation’.Footnote 133 Preaching that ‘[Hong Kong independence] is the salvation’,Footnote 134 collective coping within the affective communities defined a new objective and prescribed a desired future that is repressed by geopolitical reality. Hong Kong independence is thus empowered with emotional legitimacy within the localist affective community, which draws the boundary of the affective community and consolidates the affective bond among its members.

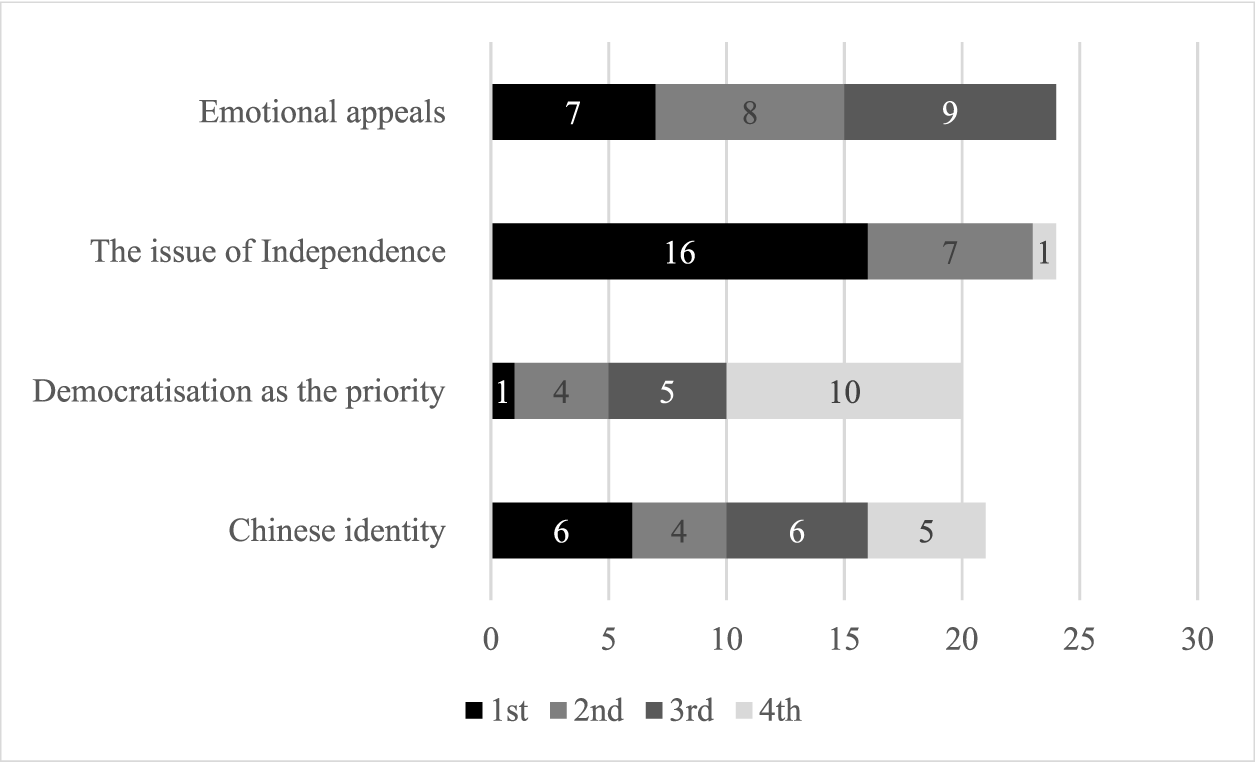

Localist leaders removed pan-democrats from their affective community. This is the result of various coping responses reflected in a survey of localist leaders on their differences with the pan-democrats, shown in Figure 2. The consequences of two coping responses are ranked highest: emotional appeals as a result of emotion-focused coping, and the issue of independence as a result of problem-focused coping.

Figure 2. Localists’ perceptions of their difference from pan-democrats.

Pan-democrats detest the idea of independence because it ‘poke[s] the tiger in the eye’.Footnote 135 Instead, their leaders cope with the stressful situation in Hong Kong by fixating on ‘democratisation’ as a priority embedded in a fight for a democratic China.Footnote 136 Localists’ rejection of China, in conjunction with emotional appeals such as anger and hope, enabled the rise of independence as the prime difference from the pan-democrats. This means that localists’ problem-focused coping responses led them to assign gravitas to the issue of independence.

With localism as a broad concept resonating with various political groups in Hong Kong, a localist lawmaker warned that ‘pan-democrats are stealing the term (localism)’ and suggested moving on ‘to an issue that they dare not to steal. We are using nation-building, which is too radical for them.’Footnote 137 Hence, independence becomes the litmus test for members within the affective community, because it symbolises the emotional bond that unites them. The pursuit of independence interweaves individual coping with a collective effort to search for Hong Kong’s future. This continuous collective and individual coping with prevailing negative emotions guarantees sufficient emotional energy to sustain the affective community.

The durability of coping and affective community

Our interview data reveals that, in some cases, everyday stresses experienced by localist leaders accumulated to traumatising levels. During the scaling-up from individual coping to the collective, Hong Kong independence emerged as an embodiment of hope, a key coping resource.Footnote 138 The durability of the independence issue does not lie in its practicality. Instead, the strength of the affective community and the rising political significance of independence resides in the stressor, i.e. pressure from the Chinese government: ‘the more the Chinese government pushes us, the more determined the future generation will become’.Footnote 139

In June 2019, Hong Kong was rocked by mass demonstrations against proposed amendments to the extradition law. Affective patterns and the coping process recurred. Triggering the protests was the fear that the legal amendments would allow extraditions of Hong Kong residents to the PRC. Anger resurfaced as the Hong Kong government ignored public demands and deployed heavy-handed police tactics against peaceful protestors.Footnote 140 The escalating police brutality was met with an increasing radicalisation of protests, escalating the stressor of mainlandisation into trauma. More than 1 in 10 adults (11.2%) in Hong Kong suffer from post-traumatic stress syndrome,Footnote 141 which is closely linked to the political climate.Footnote 142

Problem-focused coping such as direct action is visible and mainstreamed in the form of broad support from society.Footnote 143 Survey data shows that at the height of the movement, 98.4% of respondents agreed with the statement ‘I think we are in the same boat’ when asked about the appropriateness of ‘radical and confrontational actions to express their demands’.Footnote 144 In addition, the solidarity between Taiwan and Hong Kong grew stronger as a result of emotion-focused coping,Footnote 145 to the extent that the anti-extradition movement in Hong Kong impacted the early campaign phase of the 2020 presidential election in Taiwan.Footnote 146

Even though the anti-extradition movement is not about Hong Kong independence, there was a small uptick in support for independence: 19.5% of respondents supported Hong Kong independence even after the passage of the national security law.Footnote 147 Alongside support reflected in opinion polls, emotional attachments to Hong Kong independence became more visible during the protests in the form of slogans, banners, and artwork.Footnote 148 These signified the increasing emotional attachment to an alternative vision for Hong Kong’s future. Developments since the introduction of the national security law in 2020 indicate that the emergent affective community has adapted to the political challenges in Hong Kong. The exodus of Hong Kongers does not prevent them from organising global rallies, which extend the territorial borders of the affective community and verify its adaptive nature.Footnote 149

Conclusion

The theorisation of coping in this paper is a renewed effort to appreciate the coping process in IR. Continuing the articulation that emotions matter in the discipline, our intervention suggests that the process of dealing with emotions is also a constitutive feature of global politics, shaping the conditions of political possibilities.

While the main literature this paper speaks to is emotions in IR, our theoretical framework of coping enhances the engagement with coping in political psychology and ontological security literatures. The foregrounding of emotion-focused coping in individual decision-making incorporates leaders’ emotional well-being into the calculation. In addition, the theory of coping provides a new lens with a sharper focus on how leaders process emotional states. This will allow new ways of examining the existing evidence of dealing with stressors in autobiographies, official speeches, and archival materials. This paper’s encounter with the ontological security literature suggests the significance of individuals’ emotional well-being. The non-state nature of our illustrative case testifies to the relevance of ontological security to sub-national discontent and disagreement, highlighting the distributive politics of anxiety management.

Our contribution to the established theorisation of emotions in IR is to fine-tune the levelling-up process by offering two amendments. Conceptually, the coping framework adds the circulation of coping responses to the scaling-up pathways for collective affective experience. Self-representation and representation in the communication of coping responses allows individuals to stock up coping resources, which is vital because structure-induced stress exceeds the resources of a single person. Relatedly, the methodological contribution of this paper is to shed light on self-representation that connects individuals’ emotional well-being to collective agency.

The illustrative case of Hong Kong is a sharper instance of more general phenomena, such as social movements, revolutions, civil disobedience, global action in response to the climate crisis, and nationalist protests. When protest is experienced as quasi-therapy, the official narratives of intimidation and repression feed the loop of coping and collective action. In the case of Hong Kong, the sovereign’s strategy to impose legislation to criminalise separatist ideas created an exodus of Hong Kongers. Ironically, it was Beijing that made an otherwise small-scale, local, and sub-national level of suffering globally visible. Findings from this paper have policy implications. They rectify the official diagnosis that Hong Kongers’ problems are merely socio-economic. This research shows these are questions of emotional well-being, and failure to recognise this drives Hong Kongers to seek more creative political options.

The limitations of this paper arise from the richness of the empirical data. An example is the discussion of 4 June among localists, which prompts questions about whether coping leads to division in society per se or if it is a case-specific development.Footnote 150 Future research could address this outstanding question through a deeper dive into the psychology of coping with reference to ontological security literature. This could potentially clarify the linkage between anxiety and creativity, as it might be that the positive potential of anxiety is realised during the coping process.Footnote 151 International politics induce stressful situations, and how we cope with stress in turn may sow the seeds for change and creativity.

Video Abstract

To view the online video abstract, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210523000591.

Acknowledgements

Earlier draft versions of this article dating back to 2018 were commented on by Roland Bleiker, Bill Callahan, Liz Carter, Clara Eroukhmanoff, Theofanis Exadaktylos, Karin Fierke, Martha Finnemore, Todd Hall, Jack Holland, Emma Hutchison, Moran Mandelbaum, Jonathan Mercer, Helen Parr, Barry Ryan, Wu Jieh-min, and Joanne Yao. We are grateful to Sasha Milonova for helping us clarify our argument, and to Daniel Wong and Terence Yeung for invaluable research assistance. This article has also benefited from comments, questions, and support from colleagues at the following annual conferences: European Association of Taiwan Studies (2017), International Studies Association in Asia (2017), Association for Asian Studies (2018), British International Studies Association (2018 and 2019), and ‘The West and the Rest: Challenging the Emotions Research Agenda’ workshop organised by the BISA Working Group on Emotions in Politics and IR in 2019. We would like to thank the journal editors and anonymous reviewers for all the constructive and insightful feedback on this article.

Funding statement

Fieldwork was made possible by the Taiwan Spotlight Project 2015, Ministry of Culture, Republic of China (Taiwan) and the University of Surrey through Pump Priming Funds 2016–17 and 2019–20, the Impact and Engagement Fund 2017–18, and Surrey-19/20-P0001 ESRC Impact Acceleration Fund.