I am writing this editorial at the start of my final year as Director of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) at the Royal College of Psychiatrists and as the CPD Committee is preparing a CPD policy revision. It is both a personal reflection on the past few years and an anticipation of the future.

CPD policy

The current CPD system, based on personal development plans validated by a peer group, seems to be working well. We are the only Royal College to have a peer-group process and I think the others are missing out. I believe that our peer-group mechanism elevates CPD above a mere box-ticking and credit-gathering exercise. For many, working in peer groups has become a collaborative exercise with, at the least, a few helpful suggestions from colleagues. In a number of cases peer groups have become ‘action learning sets’ – actually meeting some learning objectives within the group (Reference LavertyLaverty, 2004). Peer groups emphasise the importance of both supporting and being supported by our colleagues and not becoming professionally isolated.

The CPD Committee has already determined that CPD policy revision will focus on making the system more user-friendly rather than altering fundamental principles. Forms will be revised and simplified, the process of setting learning objectives clarified and we will aim to avoid unnecessary duplication.

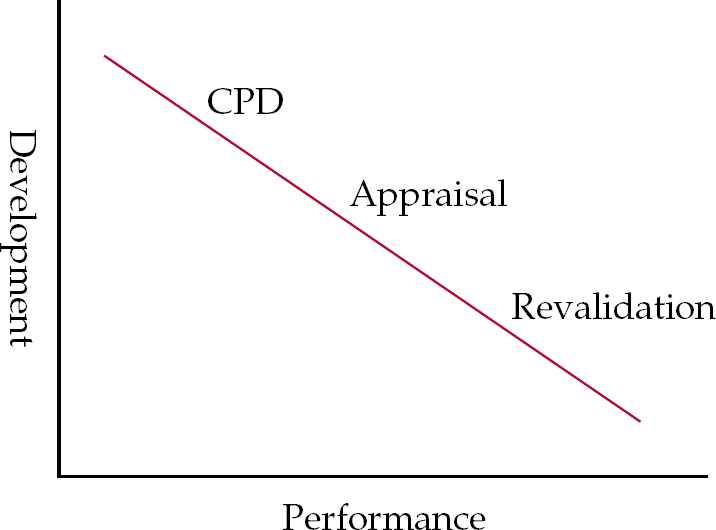

There is an important tension at the heart of CPD. On the one hand, CPD is part of our professional regulatory mechanism and as such is concerned with our performance as doctors and providing evidence that this meets, at the very least, a basic standard (Reference BouchBouch, 2003a). On the other hand, continuing professional development is about our lifelong learning. It is personal, owned by us and aspirational (Reference BouchBouch, 2003b). This tension is shared particularly with appraisal and to some extent with revalidation.

It seems to me that the most helpful way to consider the relationship between CPD, appraisal and revalidation is to consider that all three processes are concerned with both development and performance but that for each the relative concerns are different (Fig. 1). Continuing professional development starts with the individual and their personal development plan. Both support and accountability are brought by peer-group discussion. Appraisal, although still having a strong emphasis on development, brings in organisational accountability. The process of revalidation can also be seen as developmental (Reference CattoCatto, 2005) but ultimately it is most concerned with performance and an assessment of fitness to practice.

Revalidation

Uncertainty and anxiety over what will be the method for revalidation has been a constant backdrop to CPD for the past few years. Initially, revalidation was talked of as being ‘an MOT test for doctors’ (Reference KmietowiczKmietowicz, 2005). In the Shipman Inquiry, Dame Janet Smith was heavily critical of the General Medical Council for deciding to base revalidation solely on appraisal (Reference SmithSmith, 2004). In essence, her criticism was that a summative assessment regarding a doctor’s fitness to practise should not be based only on a mechanism that was intended to be formative. The Chief Medical Officer’s report based on his Review of Medical Revalidation: A Call for Ideas (Department of Health, 2005) is due shortly. In the report, a key set of questions asked

‘Should doctors’ performance be assessed in addition to, or as part of, the annual NHS appraisal? What purpose should appraisal of clinical practitioners have: should it be primarily for governance, with a mainly summative structure and handling, or should it be – as at present – primarily for developmental purposes, with a mainly formative structure and handling? Can it do both at the same time?’ (Department of Health, 2005).

In the Shipman Inquiry, Dame Janet Smith called for the introduction of a knowledge-based assessment as part of revalidation. It is still uncertain whether in the future we will have to undergo some form of assessment to be revalidated. But in this eventuality, as a clinician I would rather be tested on my skills in working with patients than on my theoretical knowledge of, for example, neurotransmitters or Freudian theory. It hardly seems logical that, as we move to making workplace-based assessments the means of assessing our trainees’ competence, senior doctors should have a knowledge test to assess their fitness to practise.

Consultants and changes in postgraduate medical education

The revolution taking place in postgraduate medical education has to date focused attention mostly on the early years of medical training after graduating. The Modernising Medical Careers initiative (http://www.mmc.nhs.uk/pages/home) has been concerned with developing a new career framework (Fig. 2). The Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB; http://www.pmetb.org.uk/) is setting standards, including those for the process of trainee assessment.

There are important implications for consultants. Modernising Medical Careers introduces the concept of the ‘workplace-based assessment’. This will involve observing trainees perform in actual clinical encounters. It is hard to argue against the rationale for such assessments. How a doctor performs in real clinical settings should determine progress rather than, for example, merely knowledge tests. The introduction of the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) to the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ MRCPsych Part I membership examination had a similar rationale, albeit that here psychiatrists are being tested in simulated clinical situations rather than real ones. But there is a problem. Existing consultants have by and large neither been trained in the new methods of assessment, nor have they themselves been assessed in this way as they have progressed through their careers. Worse than that is how little experience most of us have in either directly observing our trainees undertaking clinical work or vice versa. It is no longer accepted that if trainees develop their knowledge, then skills and attitudes will take care of themselves. In addition to time, consultant trainers will themselves require further training.Footnote 1 Training in how to support, develop, assess and give feedback to our trainees as their educational supervisors. Training in how to work with poorly performing trainees and those few who will ultimately fail to progress. And training in the various aspects of supervision, which include supervising clinical management, teaching and research, management and administration and giving pastoral care (Reference CottrellCottrell, 1999).

Post-CCT training

Training in supervision is only one of a number of examples where consultants themselves may wish to or will have to undergo further competency-based training. One situation that already exists is training related to the Mental Health Act. To take on ‘responsible medical officer’ duties, consultants have to undergo approved training, which is topped up on a regular basis. There are other roles that consultants take on, including clinical, managerial, training and research, where further training is both relevant and necessary. Examples include the roles of lead clinician overseeing electroconvulsive therapy (ECT lead), clinical director, College tutor and research tutor. Other situations in which consultant training may be necessary include return to practice after a lengthy career break, identification of performance problems at appraisal, and switching specialty or developing a particular area of expertise. Such training has been designated ‘post-CCT training’ (CCT: Certificate of Completion of Training) and it is likely to become increasingly important.

Traditionally, the Royal College of Psychiatrists has been the body that has been responsible for setting standards in psychiatric training. With the advent of PMETB there is a changing emphasis. PMETB will not work independently of the medical Royal Colleges, but it is likely that roles will gradually change and the Colleges’ responsibilities for providing training will become increasingly important. With this in mind, last year the Royal College of Psychiatrists set up the College Education and Training Centre (CETC). The CETC, in addition to providing traditional workshops and conferences (a list of forthcoming events appears on the inside back cover of this issue of APT), is developing Accredited Training Modules. The first module to be piloted will be on educational supervision and will involve 3 days of training – the first day consisting of personal study and the second and third days involving the development of skills by direct practice, observation and feedback. Participants will be assessed on both knowledge and skills. Satisfactory completion of the Accredited Training Module will result in a certificate issued by the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Conclusions

As with any other time of great upheaval there is now both threat and opportunity. Time and money to train and be trained are vital. This is problematic. The service commitment of trainees is reducing, partly because their hours are shorter as a result of the European Working Time Directive. Demands on consultants are growing. But as never before consultants’ need for both personal development and lifelong learning is being highlighted. If training rather than bureaucracy is strengthened then I think the changes will be worthwhile.

Fig. 1 The three processes – relative concerns.

Fig. 2 The Modernising Medical Careers’ career framework proposal. Red type indicates undergraduate, foundation, specialty and CPD level; arrows indicate competitive entry. (National Health Service, 2006.)

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.