Inflicting retributive punishments on wrongdoers is central to our sense of justice. Even when we have not been directly harmed by a transgression, we desire to punish the transgressor (e.g., Reference Fehr and FischbacherFehr & Fischbacher 2004; Reference Vidmar and MillerVidmar & Miller 1980). In American society in particular, this punitive response to wrongdoing dominates both the justice system and the discourse about crime and punishment (Reference CurrieCurrie 1998; Reference DomanickDomanick 2004; Reference SimonSimon 2007; Reference TonryTonry 2004). This focus on punishment is clearly illustrated in the large and growing prison population in the United States: more than 2 million offenders are currently serving prison sentences, with an average increase in the inmate population of around 3 percent per year. In addition, both the federal prison system and about half of the state prison systems are operating at overcapacity (Reference Harrison and BeckHarrison & Beck 2006: n.p.).

Relying solely on punishment (and prison) as means of achieving justice, however, raises a number of societal problems. The prison system is extremely expensive to maintain. For instance, in 2003, it cost more than $25,000 to incarcerate a single offender each year in the federal prison system (U.S. Department of Justice 2003:118). State and federal expenditures on prisons siphon funding from other government-supported institutions, such as public schools.

The current focus on punishment also neglects implementing methods to manage a range of other harms caused by crime. For instance, there is little consideration of offender rehabilitation when assigning criminal sanctions. And victims' needs and concerns are typically not well-addressed by the criminal justice system. The lack of victims' involvement in their own justice proceedings has been cited as leading to victims' dissatisfaction with the justice process (Reference BartonBarton 1999; Reference O'HaraO'Hara 2005; Reference Strang and ShermanStrang & Sherman 2003).

This fixation on punishment may have also limited psychological investigations of people's responses to criminal violations. Research in this area has focused on identifying the motives, concerns, and goals underlying the punishments people assign for intentional wrongdoing by measuring people's punitive intent in response to transgressions (e.g., length of prison sentence, punishment severity, and overall punitiveness). These investigations have demonstrated that people respond to intentional wrongdoing not as instrumentalists (concerned with deterrence and fears of victimization) but with a moral reaction (concerned with offenders receiving their “just deserts” and the moral health of society). At the individual case level, retribution motivates people's punishment responses (Reference CarlsmithCarlsmith 2006; Reference CarlsmithCarlsmith et al. 2002; Reference DarleyDarley et al. 2000; Reference McFatterMcFatter 1978, Reference McFatter1982; Reference Warr and StaffordWarr & Stafford 1984). At the macro level, Tyler and colleagues have shown that people's support for punitive policies is determined by their symbolic concerns about the moral cohesion (or lack thereof) present in society (Reference Tyler and BoeckmannTyler & Boeckmann 1997; Reference Tyler and WeberTyler & Weber 1982).

However, empirical investigations of people's reactions to wrongdoing that focus exclusively on people's desire to punish wrongdoers neglect other considerations people may have when contemplating achieving justice. The focus on punitive responses and the assigning of prison sentences has hampered the consideration of other justice goals that people may want to assign to justly deal with wrongdoing. The term justice goals refers to the subgoals of the ultimate goal of achieving justice, and it is through the fulfillment of these subgoals that this ultimate goal is reached (Reference Gromet and OswaldGromet in press). People may be concerned with three potential justice targets when thinking about achieving justice (the offender, the victim, and the community), and concern with these different targets should lead to an interest in fulfilling a variety of justice goals. Previous research has demonstrated that people associate these justice targets with different punishment goals that range in punitiveness (Reference OswaldOswald et al. 2002), but investigators have not explored whether concern with these different targets may influence people's responses to wrongdoing that go beyond punishment.

Therefore, there is an imbalance in what we know. Although much research concerns what influences the extent to which people desire punitive measures, as well as the goals that people have for the assigning of prison sentences (e.g., Reference CarrollCarroll et al. 1987; Reference McFatterMcFatter 1982), we know rather less about people's desire to satisfy additional justice goals beyond those that are focused on punishing the offender (however, see Reference De Keijserde Keijser et al. 2002 for a study of penal attitudes that includes restorative concerns). The aim of the present research is to explore whether people consider multiple justice goals when determining the full range of actions required to produce just outcomes.

Retributive and Restorative Justice

To understand which justice concerns may be part of people's responses to wrongdoing, it is useful to examine the different categories of justice (and the goals they achieve) that pertain to criminal wrongs. The two categories that we focus on are retributive and restorative justice (as this implies, we do not address either crime deterrence or incapacitation of dangerous offenders). Retributive and restorative justice are not the only justice categories that may apply to people's responses to criminal wrongdoing. We focus on these two categories in the present research because both retributive and restorative justice offer a number of justice goals that have been discussed as part of people's responses to intentional wrongdoing.

Retributive justice has been described broadly as an area of inquiry that addresses the punishment of offenders and the reaffirming of societal boundaries and values (Reference TylerTyler et al. 1997), which has concentrated on punitive goals. As we discussed previously, there is a desire to inflict punitive measures on wrongdoers, which is motivated by just deserts, retributive factors, rather than deterrence or incapacitation concerns (Reference CarlsmithCarlsmith et al. 2002; Reference DarleyDarley et al. 2000). A less studied component of retributive justice is its ability to send a message to community members that wrongdoing is not tolerated within the boundaries of the community, as well as to show support for the community values that were violated (e.g., Reference Durkheim, Lukes and ScullDurkheim 1983; Reference Vidmar and MillerVidmar & Miller 1980). The two goals pertaining to retributive justice in the present research are thus punishment of the offender and reinforcement of community values.

Restorative justice, on the other hand, has only recently been empirically scrutinized and implemented in criminal justice systems, although the extent of both these activities is increasing (Reference Roberts and StalansRoberts & Stalans 2004). Restorative justice aims to bring all actors affected by the offense (victim, offender, and community) together to jointly determine the harms that the offense has caused and what must be done to repair these harms. As this implies, restorative justice procedures are concerned with restoring the victim and the community, as well as reintegrating the offender into society (Reference BazemoreBazemore 1998; Reference BraithwaiteBraithwaite 1989, Reference Braithwaite2002; Reference Marshall and JohnstoneMarshall 2003). Therefore, the three goals pertaining to restorative justice for the present research are restoring the victim, restoring the community, and rehabilitating the offender.

We argue that people may entertain other factors beyond the retributive sanction that needs to be inflicted on the offender. This is not to diminish the role that retribution plays in people's justice responses. Punishment appears to be a necessary part of the response to a serious moral transgression. However, people may also demonstrate restorative concerns for both the victim and the community, as these targets suffer both material and psychological harms as a result of a criminal violation. Indeed, research has demonstrated that people opt to use restorative measures to respond to crimes that are low in severity (Reference Doble and GreeneDoble & Greene 2000; Reference Gromet and DarleyGromet & Darley 2006; Reference Wenzel and ThielmannWenzel & Thielmann 2006). More important for our current purposes, it has been shown that for serious offenses, people preferred an option that allowed them to assign both a restorative justice conference and a (punitive) prison sentence, rather than either of these options alone (Reference Gromet and DarleyGromet & Darley 2006). Therefore, restorative considerations may appeal to people's sense of justice in conjunction with a desire to punish.

This points to another aim of the present research: to break down the potentially artificial barrier between retributive and restorative justice in how people respond to wrongdoing. Research on these two types of justice responses have largely been conducted by investigating each set of justice practices separately, or by pitting these two approaches to justice against each other (see Reference Roberts and StalansRoberts & Stalans 2004). Given that one view in the restorative justice community has rejected punitive practices (e.g., Reference Braithwaite, Strang, Braithwaite and StrangBraithwaite & Strang 2001), it is easy to see why this “either/or” orientation has emerged. However, in the present research, we attempt to see whether respondents, if given the opportunity to do so, would want to satisfy justice goals related to both retribution and restoration. Accordingly, our current objective is to investigate the full range of justice concerns that an intentional wrong elicits. We investigate the hypothesis that people's need to punish the offender does not preclude a desire to fulfill additional justice goals that affect the victim and the community, when people are attentive to these justice targets.

The Present Research

Three studies investigate whether people seek to satisfy a range of different justice goals and what sanctions they will employ in the service of these goals. Study 1 explores whether people are in fact concerned with different justice goals, and the degree to which this depends on differing features of an offense. Study 2 examines how people believe that different justice goals can be met through the assigning of various sanctions. In Study 3, we link the findings of the first two studies by inducing different perspectives in respondents, which should affect which sanctions, and thus which justice goals, must be fulfilled in order for justice to be achieved.

These studies test two main predictions. First, we predict that people will always be concerned with punishing the offender, particularly if the offense is a morally grave one. This contention is supported by research in a number of different domains. In addition to the research previously cited demonstrating that people respond to wrongdoing by seeking retribution (e.g., Reference CarlsmithCarlsmith et al. 2002; Reference DarleyDarley et al. 2000), studies on attribution provide further evidence for the likely ubiquity of the desire to punish. People in Western cultures typically focus on the actor (and his or her dispositions) as the cause of events (e.g., Reference Morris and PengMorris & Peng 1994; Reference Ross and BerkowitzRoss 1977). More important, they tend to focus on an actor and his or her internal characteristics in making attributions for negative events and norm violations, which leads to the infliction of punitive responses for wrongdoers (Reference AlickeAlicke 2000; Reference GoldbergGoldberg et al. 1999; Reference ShaverShaver 1985; Reference TetlockTetlock et al. 2007). Findings such as these suggest that people's default response to wrongdoing may be to focus on the offender, rather than the victim or the community.

Second, however, we predict that if people's attention is drawn to the victim or the community, they will want to mobilize sanctions related to these justice concerns. But because victim and community justice concerns are not as intuitive as people's retributive response, concern for these justice targets and the goals associated with them is likely to be far more dependent on situational factors (such as the features of the crime and the respondent's perspective) than is the desire to punish the offender.

Study 1

We first wanted to investigate whether people are in fact concerned with multiple justice goals when responding to wrongdoing. To this end, we allowed participants to simultaneously indicate the extent to which they wanted each justice goal to be achieved (punishing and rehabilitating the offender, restoring the victim, reinforcing community values, and restoring the community), without having to provide a rank order of the different justice goals. This method allowed people to express concern for more than one justice goal, which provided a means of investigating the following question: Do people view additional justice goals (e.g., restoring the victim) to be as necessary for achieving justice as punishing the offender, and can people's concern with these additional justice goals be influenced by the features of the offense?

The features of an offense play an important role in the kinds of punishments people want to inflict on an offender (Reference TylerTyler et al. 1997; Reference WeinerWeiner et al. 1997), and so they may also influence people's views about how justice needs to be achieved more broadly. That is, people's concern with different justice goals may be partly determined by the features of the offense. For instance, people may be far more concerned with community-related justice goals when a community park is vandalized than when a person in the community has their private property vandalized.

In the present experiment, we manipulated three different offense features: the severity of the offense, the type of victim (a specific person or the community as a whole), and whether the offense posed a threat to society. This yields a 2 (low severity/high severity) × 2 (community as victim/specific victim) × 2 (low threat/high threat) within-subjects design, with participants evaluating eight different crimes each.

These features were selected because they have been discussed as important to justice concerns that focus on the offender, the victim, or the community. Previous research has established that one of the most important offense features with regard to people's justice judgments is the moral seriousness of the offense. For instance, Darley and colleagues demonstrated that high severity offenses make people want to inflict harsher punishments, cause them to believe that the offender is less likely to be rehabilitated, and lead them to reject purely restorative options as a response to wrongdoing (Reference CarlsmithCarlsmith et al. 2002; Reference DarleyDarley et al. 2000; Reference Gromet and DarleyGromet & Darley 2006). Whether a specific person or the community was victimized by the offense should elicit justice reactions that focus on either the individual or the community, respectively (see Reference Hans and ErmannHans & Ermann 1989). The perceived level of societal threat should influence the extent to which people feel it is desirable to reinforce the values of the community: people should be motivated to bolster important societal values that have been challenged by criminal violations (Reference RuckerRucker et al. 2004; Reference TetlockTetlock et al. 2007; Reference TylerTyler et al. 1997).

In the present study, we investigated whether people demonstrate as much of an interest in satisfying other justice goals as they do with punishing the offender. If punishing the offender is the central concern that emerges when people are faced with wrongdoing, then this justice goal should be paramount for all types of wrongdoing. People's concern with the remaining justice goals (rehabilitating the offender, restoring the victim, reinforcing community values, and restoring the community) may be far more dependent on the particular features of the crime. In particular, the nondefault justice targets (the victim and the community) may need to be salient in order for people to express concern with their associated justice goals.

To test this prediction, we analyzed each of the eight crimes separately to determine the relative importance of the different justice goals for each crime. We predict that punishing the offender should always be viewed as one of the goals most needed to achieve justice, irrespective of the features of the offense. However, whether one or more of the remaining justice goals are considered to be as important as punishing the offender should depend on the offense features. Specifically, when a specific person is victimized, people should think that restoration of the victim is as needed as punishment, whereas when the community as a whole is victimized, the goal of community restoration should be on a par with punishment. For the threat the crime poses to society, people should think that reinforcing community values is as necessary as punishment. That is, for each specific combination of offense features (e.g., a high-severity crime that victimizes a specific person and presents a high threat to society), the presence or absence of these offense features will determine which justice goals people think are as needed as punishment to achieve justice (e.g., victim restoration and reinforcing community values).

Method

Participants

Forty-three Princeton undergraduate psychology students (63% female) participated in the study as part of a course requirement. They ranged in age from 18 to 29 (M=19.50, SD=1.98). A majority of the participants identified themselves as white (60%) and as politically liberal (63%). One participant did not report any demographic information.

Procedure

The experimenter greeted the participants and sat at a computer with Internet access. They completed the experiment online. Participants learned that there are multiple ways to think about achieving justice, which impact different targets in the justice process (specifically, the offender, the victim, and the community). Participants were informed that their task was to act as judges and decide how to handle a number of different offenses, while considering all three justice targets. Participants were told that some of these offenses did not have specific victims; rather, the “victims” were members of the community or society as a whole. The experimenter instructed them to answer questions regarding the victim by thinking of whichever entity (community members/society) they thought was victimized by the crime. This information was included to avoid any confusion participants might have encountered with answering questions about the victim for crimes in which the community as a whole, rather than a specific person, had been victimized.Footnote 1

Participants then learned that they were operating in a jurisdiction where offenses were handled by assigning sets of sanctions. They were told that these sanction sets could each accomplish one of five justice goals (punishing the offender, rehabilitating the offender, restoring the victim, reinforcing community values, and restoring the community). Participants learned that one set of sanctions would punish the offender, another set would restore the victim, and so on. Participants were not presented with specific sanctions.

Participants read through all eight crimes in a randomly generated order. Table 1 contains the crimes that participants judged.Footnote 2 As a check on the effectiveness of the offense feature manipulations, the experimenter asked participants to answer six questions about the three justice targets after reading each crime: how serious the offense was and how likely it was that the offender could be rehabilitated; how much material and psychological harm the victim suffered; to what extent they thought the community had been harmed; and how prevalent a problem the offense is in society today. All six questions were answered on a scale that ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very).

Table 1. Offense Feature Classification of Crimes Used in Study 1

After completing these ratings, participants then completed the main dependent measure of interest by indicating whether they thought each of the five sanction sets was essential, desirable, or not necessary to achieve justice for each offense. The sanction sets were presented in a randomly generated order. The description of each sanction set is listed below:

Punish Offender Set: The focus of these sanctions is on punishing the offender for the crime that he or she committed. These sanctions allow the offender to be reprimanded and punished for his or her actions.

Rehabilitate Offender Set: The focus of these sanctions is on rehabilitating the offender. These sanctions work to reintegrate the offender back into society, as well as to bring about an internal, moral change of the offender.

Restore Victim Set: The focus of these sanctions is on repairing the harm that has been caused to the victim. These sanctions make the victim feel better about the victimization and to feel restored to where they were before the crime occurred.

Reinforce Community Values Set: The focus of these sanctions is on sending a message to the community that these types of actions are not tolerated. These sanctions reinforce the norms and values of the community that the offense violated.

Restore Community Set: The focus of these sanctions is on repairing the harm that has been caused to the community. These sanctions allow for the community to be paid back and restored for the harm that the crime caused.

After completing these questions for all eight offenses, participants answered demographic questions and were debriefed and thanked for their participation.

Results

Manipulation Checks

We first wanted to determine whether participants viewed our manipulations of offense severity, victim type, and threat to society as we expected they would. To this end, we conducted separate repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for each of the six questions that asked for participants' perceptions of the three justice targets (offender, victim, and community), with the three manipulated features of the offense as independent variables. For the purposes of this analysis, we report only the main effects of interest (Table 2 provides the means and standard deviations of the six manipulation checks for each crime).

Table 2. Manipulation Checks on People's Perceptions of the Offense Features

N=43

Note: Standard deviations are in parentheses. Subscripts apply only across columns. Subscripts differ from each other at p<0.05.

All the manipulation checks demonstrated that the offenses were perceived as expected. For the seriousness of the offense, participants saw high-severity offenses (M=5.87, SD=0.73) as more serious than low-severity offenses (M=4.67, SD=1.03), F(1,42)=65.75, p<0.0001. Conversely, participants saw offenders who committed low-severity offenses (M=5.24, SD=1.03) as more likely to be rehabilitated than offenders who committed high- severity offenses (M=3.99, SD=1.01), F(1,42)=77.27, p<0.0001.

With regard to the victim, participants saw crimes that had specific victims as causing more material harm (M=5.74, SD=0.70) and more psychological harm (M=4.81, SD=1.14) to the victim than crimes in which the community was the victim (material: M=3.81, SD=1.30; psychological: M=3.11, SD=1.26), F(1,42)=98.81, p<0.0001 and F(1,42)=90.51, p<0.0001, respectively.

With regard to the community, participants saw high-threat crimes (M=5.67, SD=0.78) as being more of a problem in society than low-threat offenses (M=4.24, SD=1.02), F(1,42)=92.55, p<0.0001. For community harm, participants viewed crimes that directly victimized the community (M=5.16, SD=0.98) as causing more harm to the community than crimes in which there were specific victims (M=4.24, SD=1.19), F(1,42)=25.91, p<0.0001.

Multiple Justice Goals

In order to test the hypothesis that people would find additional justice goals to be as necessary for achieving justice as punishing the offender, we first needed to establish whether different crime features produced different justice goal ratings. To this end, we conducted repeated-measures ANOVAs on participants' judgments about the necessity (1=not necessary, 2=desirable, 3=essential) of the five different justice goals (punishing the offender, rehabilitating the offender, restoring the victim, reinforcing community values, and restoring the community) for each distinct combination of crime features (i.e., each of the eight crimes) separately. For all eight crimes, there were overall differences between participants' perceptions of how necessary each of the five goals was to achieve justice (all ps<0.0001). Tables 3a and 3b present the means for the necessity of the five justice goals for each feature combination.

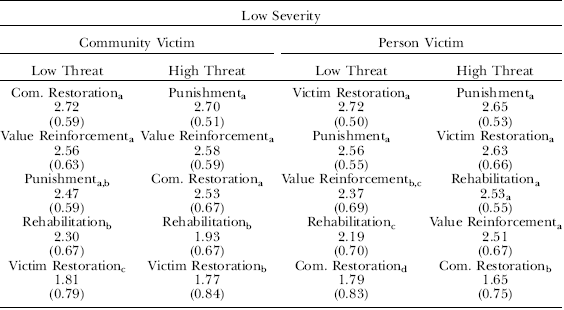

Table 3a. Comparisons of Justice Goal Necessity Within Each Low-Severity Offense Feature Combination

N=43

Note: Scale ranges from 1 to 3. Subscripts apply only within each column. Subscripts differ from each other at p<0.05. Standard deviations are in parentheses.

Table 3b. Comparisons of Justice Goal Necessity Within Each High-Severity Offense Feature Combination

N=43

Note: Scale ranges from 1 to 3. Subscripts apply only within each column. Subscripts differ from each other at p<0.05. Standard deviations are in parentheses.

We specifically predicted that punishing the offender would be viewed as one of the most essential justice goals for all eight crimes, and that which additional goals were considered to be as important would be determined by the specific features of the offense. To further explore this prediction, we conducted paired-sample t-tests that compared participants' ratings of the five justice goals within each crime (i.e., all possible pairwise comparisons among the goals for each offense). The first hypothesis was confirmed, as participants viewed punishing the offender as one of the most important requirements for achieving justice for seven of the crimes (i.e., no other justice goal exceeded it, all ps>0.05) and the most important justice requirement for the remaining crime (all ps<0.005).

We further examined these pairwise comparisons of the five justice goals to determine which specific goals were considered equivalent in importance with punishment for each individual crime. We first considered the four offenses that were low in severity. As Table 3a demonstrates, victim type (person versus community) influenced the importance of victim and community restoration for these crimes. For the two crimes that had a community victim, participants considered restoring the community to be as required to achieve justice as punishment (low threat: M restore=2.72 vs. M punish=2.47, t(42)=1.98, ns; high threat: M restore=2.53 vs. M punish=2.70, t(42)=1.26, ns), whereas for the two crimes that victimized a specific person, restoring the victim was as needed as punishment (low threat: M restore=2.72 vs. M punish=2.47, t(42)=1.98, ns; high threat: M restore=2.53 vs. M punish=2.70, t(42)=1.26, ns). In addition, participants considered value reinforcement to be as required as punishment for all four low-severity offenses (all ts<1.39).

Although participants found that rehabilitating the offender was as important as punishment for two of the four low-severity crimes (community victim, low threat: M rehabilitate=2.30 vs. M punish=2.47, t(42)=1.19, ns; specific person, high threat: M rehabilitate=2.53 vs. M punish=2.65, t(42)=1.05, ns), they did not consider the remaining justice goals as required for achieving justice for any of the four low-severity crimes (all ps<0.02). These results indicate that for low-severity crimes, participants consistently found that two additional justice goals were as needed as punishment to achieve justice, and the primary difference in justice goal support was based on victim type (whether restoration should focus on a specific person or the community).

For the four high-severity crimes in Table 3b, participants considered an additional justice goal to be as necessary as punishment for three of these crimes. For the two crimes that harmed the community, the only goal that participants considered on a par with punishment was reinforcing community values, but this was the case only for the high-threat offense (low threat: M punish=2.81 vs. M reinforce=2.42, t(42)=3.28, p<0.005; high threat: M punish=2.65 vs. M reinforce=2.51, t(42)=1.36, ns). None of the other justice goals were considered as necessary as punishment for these community victim crimes (all ps<0.0001). For the two crimes that victimized a specific person, participants thought that restoring the victim was as necessary as punishment (low threat: M punish=2.84 vs. M restore=2.79; high threat: M punish=2.84 vs. M restore=2.86, both ts<1). None of the other goals was considered to be on a par with punishment for these two crimes (all ps<.0001). Thus for high-severity crimes, participants tended to find only one additional justice goal to be as required as punishment to achieve justice.

Discussion

These results demonstrate that although people are perpetually concerned with punishing offenders, people can be equally concerned with other justice goals if the features of the offense draw their attention to these justice goals. Although not all the predictions were fully supported, the results do clearly show that people were equally concerned with additional justice goals beyond punishment. The most striking result was people's strong desire to restore the victim when a specific person was harmed by a crime. People were concerned with meeting the needs of the victim regardless of whether the offense was severe or whether it was viewed as a problem in society. The desire to see the community restored was not as strong, however, and was only viewed to be as important as punishing the offender for community crimes that were not serious offenses. There was only limited support for the societal threat prediction (a high level of threat leading to a heightened desire for reinforcing community values), as this pattern was seen only for serious crimes that targeted the community.

In addition, these findings indicate the central role that offense severity and punishment occupy in people's responses to wrongdoing. As mentioned above, punishing the offender was the most or one of the most important justice goals for all crimes. Consistent with previous research demonstrating the importance of offense severity in people's punishment decisions (Reference CarlsmithCarlsmith et al. 2002; Reference McFatterMcFatter 1978, Reference McFatter1982), we found that fewer justice goals were considered to be as necessary as punishment for high-severity offenses. The decreased emphasis on punishment for low-severity offenses may have allowed for more justice goals to be considered important.

Although these results provide evidence that people would like multiple justice goals to be fulfilled when confronted with wrongdoing, this study relied on people's self-report about which justice goals were important for handling different crimes. Study 2 addressed this issue through an approach that allowed participants to assign specific sanctions to handle different offenses. We can then infer from the sanctions people choose the different justice goals the respondents are seeking to fulfill.

Study 2

Study 1 demonstrated that people are concerned with justice goals that go beyond punishing the offender, depending on the features of an offense. However, this result depended on participants' assessments of how necessary each of the justice goals was. Simply asking participants to report their support for the various justice goals raises a number of potential problems. Although self-report is useful in understanding what people think they support and use to make decisions, people are likely to provide reasons for their behavior that are salient and seem like probable causes for their behavior, which may or may not reflect what has actually influenced their actions (Reference Nisbett and WilsonNisbett & Wilson 1977).

With regard to the justice domain, it may be that when people are provided with a number of justice possibilities, they may state that they support justice goals that, in practice, do not have an effect on their justice decisions (see Reference DarleyDarley et al. 2000). Indeed, research that has investigated why people punish offenders has demonstrated the problems with the sole reliance on this method to explain the motives behind the punishments that people assign. In general, people's self-reports about which motives they generally endorse (retribution, deterrence, etc.) are not predictive of what sentences they believe are just for individual cases (Reference CarlsmithCarlsmith et al. 2002; Reference GrahamGraham et al. 1997; Reference McFatterMcFatter 1982). Although in the present research we are examining different justice goals rather than the motivations underlying one justice goal (such as punishing the offender), these issues may be relevant for justice judgments in general.

Given these concerns, we wanted a method that allows for the assessment of multiple punishment goals and that does not rely on people's reports of which justice goals they believe are essential to achieving justice. One potential method was to allow participants to assign different sanctions (such as prison, fines, etc.) in response to specific crimes. The different justice goals that people have when they deal with wrongdoing could be associated with different sanctions, and so studying sanction choice allows for an empirical investigation of which justice goals people are motivated by. Furthermore, asking people to choose sanctions overcomes some of the potential social desirability biases that are introduced by asking for their support of various justice goals. People may self-report an interest in a particular justice goal because they perceive that showing support for that justice goal is the “correct” behavior. By contrast, social desirability concerns are far less prominent when people simply choose sanctions, as their justice goals are revealed implicitly rather than directly stated. This approach provides a way to assess how people want to handle wrongdoing when they are given the option of expressing concern with multiple justice goals without using their self-provided support of these goals.

In order to use this method, one needs an understanding of which sanctions are seen as being able to achieve different justice goals. Thus in Study 2, we asked participants to indicate which sanctions they believed could satisfy the five different justice goals in Study 1. A wide range of sanctions were used to address as many different justice targets and concerns as possible. The set of sanctions included traditional sanctions (e.g., fines and prison), sanctions from restorative justice procedures (e.g., victim expression—allowing for victims to express how they have been harmed), and sanctions that occur in public (e.g., an apology to the public). We predicted that each of the five justice goals should have distinct sanction profiles, such that each justice goal would comprise a different combination of sanctions.

Method

Participants

Sixty-six Princeton undergraduate psychology students participated in the study as part of a course requirement. Five participants were excluded because of experimenter error. Of the remaining sixty-one, 66 percent were female. Participants ranged in age from 17 to 27 (M=19.59, SD=1.71). A majority of the participants identified themselves as white (61%), and a plurality identified themselves as politically liberal (45%).

Procedure

The experimenter met the participants and provided them with a packet of materials. They learned that when people think about achieving justice after a crime has been committed, a number of justice goals may come to mind. The five justice goals (punishing the offender, rehabilitating the offender, restoring the victim, reinforcing community values, and restoring the community) were presented to the participants for review. Participants learned that their task was to indicate which sanctions (from a provided list) they thought could achieve each specific justice goal. They were told to select all the sanctions that they believed would achieve each goal. Participants also learned that they might feel that one sanction could fulfill a number of different goals, and that they could choose one individual sanction as many times as they liked, as long as they thought the sanction would be able to fulfill the specific goal in question. Participants then received descriptions of each justice goal separately and were again reminded to select the sanctions that could achieve each goal.

After reading the description of each justice goal, participants selected the appropriate sanctions from a list of 15 sanctions (each sanction was described to the participants; see Appendix for sanction descriptions): Community Response Admonishing Offender; Community Response Supporting Victim; Community Service; Counseling; Fines; Prison; Private Apology; Probation; Public Apology; Public Condemnation; Restitution; Services for Victim; Shaming; Victim Expression; Work-Release Programs.

Three different orders of this sanction list were varied between participants. After participants completed this task for all the justice goals, they then provided demographic information and were debriefed and thanked for their participation.

Results

The aim was to identify the different sanction profiles of the five justice goals. To this end, we calculated the percentage of participants who selected each sanction as being able to fulfill the different justice goals. Table 4 presents this percentage. Below, we report on the sanctions that 50 percent or more of the participants selected as being able to fulfill each justice goal.

Table 4. Percent of Participants Choosing Individual Sanctions as Fulfilling the Five Justice Goals

N=61

For the goal of punishing the offender, participants selected sanctions associated with the prison system (prison: 93%, and probation: 75%), as well as sanctions that made the offender “pay back” the victim or community through monetary or service means (fines: 80%, community service: 70%, and restitution: 70%). In addition, about half of the participants thought that humiliating the offender in public (shaming: 52%) could accomplish punishing the offender. For the goal of rehabilitating the offender, almost all the participants selected counseling (95%) as a sanction that could accomplish this justice goal. More than half of the participants also thought that a work-release program (74%), community service (70%), and probation (54%) would aid in rehabilitating the offender.

With regard to the goal of restoring the victim, the majority of the participants thought that sanctions that compensated the victim (restitution: 84%, and services for the victim: 54%) and sanctions that allowed for psychological healing of the victim (private apology: 66%, and victim expression: 59%) would accomplish this justice goal. In addition, a majority of the participants thought that a response from the community that showed support for the victim (66%) would make the victim feel restored to where he or she was before the crime occurred.

There were also distinct sanction profiles for both of the justice goals that targeted the community. For the goal of reinforcing community values, participants selected a number of sanctions that occur in public (public condemnation: 79%, community response admonishing offender: 75%, public apology: 71%, and shaming: 54%). More than half of the participants also selected two punitive sanctions (prison: 67%, and fines: 57%) as ways to accomplish this justice goal. With regard to the goal of repairing any harm that was done to the community, many participants thought that sanctions requiring the offender to compensate the community through monetary or service means (fines: 84%, and community service: 86%) were appropriate, as well as a sanction that addressed the concerns of the community through a reparative gesture by the offender (public apology: 69%).

Discussion

The results from this study demonstrate that sanctions are perceived to be differentially able to address various justice concerns. The results show which sanctions are seen as primarily concerned with punishment (e.g., sanctions associated with the prison system), rehabilitating the offender (e.g., counseling), providing restitution or restoration to the victim (e.g., sanctions that compensate the victim both materially and psychologically), reinforcing community boundaries (e.g., sanctions that occur in public), or restoring the harm done to the community (e.g., sanctions that compensate the community).

Although the primary finding of interest is which individual sanctions are seen as capable of fulfilling the different justice goals, the results also demonstrate which sanctions are viewed as accomplishing more than one justice goal. For instance, people viewed the sanction of restitution as capable of both punishing the offender and restoring the victim. Interestingly, the only sanction participants viewed as being able to address all three justice targets (offender, victim, and community) was prison. We discuss this finding in more detail in the General Discussion.

With these sanction profiles established, it is now possible to examine which justice goals people are concerned with without relying on people's self-reports of how important these different goals are. Accordingly, the aim of the next study was to use this method to investigate how the salience of the different justice targets influences which justice goals are viewed as necessary for justice to be achieved.

Study 3

The aim of the present study was to use the sanction profiles established in Study 2 to determine how situational factors influence which goals people feel are needed to achieve justice. One factor that may play a role in this judgment is which justice target (the offender, the victim, or the community) is salient in the given situation.

The salience of an actor (i.e., how prominently the actor features in the situation) has been shown to influence people's judgments about interactions both within and outside the justice domain. People's impressions of an interaction vary depending on which actor is the protagonist (Reference BowerBower 1978), and people retell transgressions differently depending on whether they are assigned the role of the transgressor, the victim of the transgression, or a neutral third party (Reference Stillwell and BaumeisterStillwell & Baumeister 1997). Therefore, it may be that when people focus on one of the three justice targets (offender, victim, or community), they will want to fulfill different justice goals than if they focused on another target. Indeed, there is evidence that people associate the three justice targets with different punishment motives. For example, general deterrence is associated with concerns about society/community (Reference OswaldOswald et al. 2002). A number of factors may influence which justice target people focus on, such as whether they have a relationship with the victim or the offender, or their feelings about the state of the community and the society in which they live (see Reference TetlockTetlock et al. 2007; Reference Tyler and BoeckmannTyler & Boeckmann 1997). In the present study, we manipulated which justice target was salient.

We hypothesized that that the justice target people are focusing on will influence the goals they want to satisfy in order to achieve justice. Specifically, we predicted that although people's default response may be to focus on the offender (who is the salient actor in the situation), people will think about concerns related to the victim and the community if they are induced to focus on these justice targets. If participants are told to focus on how a victim was affected by a crime, they may then be more eager to select measures that will restore the victim. In addition, if people are told to adopt the perspective of the community, then they may be more concerned with community-related outcomes than with punishment alone. Thus, manipulating salience of, or the focus on, the different justice targets may change which sanctions people select to achieve justice.

Participants first read descriptions of crimes and chose a limited number of sanctions that they felt were needed to best achieve justice (from the list of sanctions investigated in Study 2). They then read the same crime descriptions again, but during their second reading, they were instructed to focus on either the victim, the community, or the offender. They then re-chose which sanctions they thought would best achieve justice for each offense.

We predicted that participants who were asked to focus on the victim or the community whould show associated changes in their desired sanctions, such that, for example, participants who thought about the victim would want more sanctions that could fulfill the goal of restoring the victim. However, we predicted that participants who were instructed to focus on the offender whould choose the same sanctions as they chose in the initial uninstructed condition. Finally, we were also interested in whether there would be differences in the relative strength of the different justice goals. We expected that when participants first read about the crimes with no instructions, they would be most concerned with punishing the offender. But we also predicted that upon reading about the crimes for a second time, participants would be just as concerned to fulfill justice goals related to their target of focus as they would be to punish the offender.

Method

Participants

Seventy-five Princeton undergraduate psychology students participated in the study as part of a course requirement. Three participants were excluded because of experimenter error. Of the remaining 72, 72 percent were female. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 23 (M=19.35, SD=1.21). A majority of the participants identified themselves as white (65%), and a plurality identified themselves as politically liberal (43%).

Procedure

Default Choices

The experimenter greeted the participants and gave them a packet of materials. Participants learned that they would be reading about different crimes, and they were instructed to read the information provided. Participants read descriptions of two serious crimes: armed robbery and attempted murder. Both descriptions were a paragraph in length, and described an offender victimizing another person (both offender and victim were males). The descriptions concluded with the offender being apprehended and charged with an offense. The order in which the crimes were presented was counterbalanced. Participants read the first crime description presented to them, and they were asked to write down what they considered to be the important details of the crime. They then received the list of 15 sanctions and their descriptions. Participants were told that they should pick the five sanctions they felt would best achieve justice for the crime. Participants then repeated these tasks for the second crime. The list of sanctions was presented in three different orders (the same as Study 2).

Focus Choices

After participants completed their “default” responses, they learned that they would receive the same two crime descriptions again. Participants were instructed to focus on one of the three justice targets (offender, victim, or community) while reading the crime descriptions. Participants in the “offender focus” condition were told to think about what the offender's mindset might have been while committing the crime and what the offender's intentions and goals may have been with regard to the crime. The experimenter told those in the “victim focus” condition to think about how the victim may have been affected by the crime and how the victim may have felt as a result of the crime. Those in the “community focus” condition were told to think about how the community may have been affected by the crime (including the possible harms caused to the community), and the values and norms of the community that may have been violated as a result of the crime.

Before reading about each of the crimes again (in the same order as they had in the default phase), participants were reminded of which justice target they should keep in mind and what factors they should consider while reading the crime description. After they read each crime description, participants were instructed to write down their thoughts concerning the justice target they had been asked to keep in mind. Next, participants received the same sanction list (and instructions) as they received for their initial choices, and they were asked to select the five sanctions they felt would best achieve justice for that crime. Once they had completed these measures for both crimes, they answered demographic questions. Participants were thanked and debriefed.

Results

This study tested whether people's default response to wrongdoing is to focus on offenders, and whether people would adjust this focus if their attention was brought to the other justice targets (specifically, the person who was victimized by the crime, and the community in which the crime occurred). In order to assess both of these questions, we averaged the number of sanctions that participants chose from each of the five justice goals (punish the offender, rehabilitate the offender, restore the victim, reinforce community values, and restore the community) across the two crimes.Footnote 3 We treated a sanction as stemming from a particular justice goal based on two classification rules. We used the two sanctions that the greatest number of Study 2 participants selected as being able to fulfill each justice goal as the sanctions that represented each justice goal (see items in bold in Table 4). For the cases in which a sanction could be categorized into more than one justice goal category based on this rule, the category in which a higher proportion of Study 2 participants selected that sanction “claimed” the sanction, and the next highest sanction was then used for the “losing” justice goal.

We submitted participants' default sanction choicesFootnote 4 and the sanctions they selected after the focusing manipulation to a mixed-design ANOVA with time of selection (default versus focus) as a within-subjects variable and target focus (offender versus victim versus community) as a between-subjects factor. We performed this analysis separately for each of the justice goals.

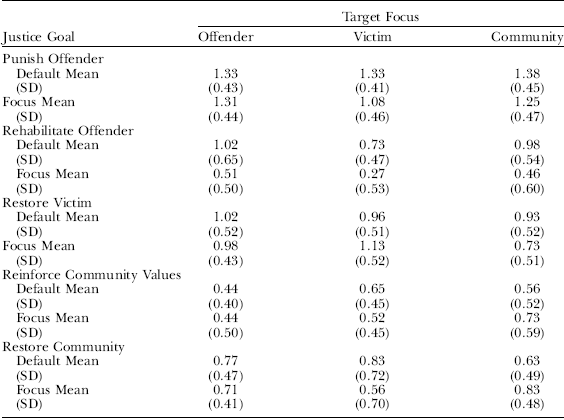

For the justice goals that targeted the victim and the community, there was an interaction between time of selection and target focus, such that the difference in the number of sanctions that participants chose between the default and focus phases depended on which target they were focusing on (restoring the victim: F(2,69)=6.68, p<0.005; reinforcing community values: F(2,69)=3.10, p=0.052; restoring the community: F(2,69)=6.47, p=0.005). For the justice goals that targeted the offender, this interaction was either marginally significant (punishment: F(2,69)=2.46, p=0.093) or not significant (rehabilitation: F(2,69)=1.31, ns). Table 5 provides the means and standard deviations of the number of participants' default and focus sanction choices by target focus for each justice goal. To further explore how the target focus influenced participants' judgments, we conducted t-tests that compared whether the number of sanctions (for each justice goal) that participants chose when they received no instruction significantly differed from the number of sanctions they chose after the focus manipulation.

Table 5. Participants' Default and Focus Sanction Choices by Target Focus

N=72

Offender Focus

Participants who were asked to think about the offender when they re-read the crimes did not show much change from their default responses. None of the default choices for the five different goals differed significantly from their choices after they had been instructed to think about the offender, ps>0.1.

Victim Focus

When participants were asked to think about the victim, the number of sanctions they chose from each justice goal differed significantly from their default choices (except for reinforcing community values, t(23)=1.54, ns). Participants who thought about the victim wanted more sanctions that were able to restore the victim than they did when they had not received any instruction on whom to think about (M=1.13 versus M=0.96), t(23)=2.56, p<0.02. They also wanted fewer of the sanctions that were directed at punishing the offender (M=1.08 versus M=1.33), t(23)=2.94, p<0.01, and rehabilitating the offender (M=0.54 versus M=0.73), t(23)=2.39, p<0.03. In addition, participants selected fewer sanctions that were directed at restoring the community (M=0.56 versus M=0.83), t(23)=3.00, p<0.01.

Community Focus

When participants were asked to think about the community, the number of sanctions they chose from each justice goal differed significantly from their default choices (except for rehabilitating the offender, t<1). Participants who thought about the community wanted more sanctions that could reinforce the values of the community (M=0.73 versus M=0.56), t(23)=2.00, p=0.057, and restore the community (M=0.83 versus M=0.63), t(23)=2.20, p<0.04. They also wanted fewer of the sanctions that were directed at punishing the offender (M=1.25 versus M=1.38), t(23)=2.30, p<0.04, as well as fewer sanctions that were directed at restoring the victim (M=0.73 versus M=0.93), t(23)=2.63, p<0.02.

Relative Goal Strength

We also wanted to examine the relative strength of the different justice goals, by comparing when participants selected sanctions without any instructions (default choices) with when they selected sanctions after they were instructed to focus on a target (focus choices). To examine this, we submitted the number of sanctions that participants chose to separate mixed-design ANOVAs for each time period, with the goal category as a within-subjects variable and target focus as a between-subjects variable. At both time periods, participants selected a differing number of sanctions from each of the goal categories (default: F(4,66)=26.73, p<0.0001; focus: F(4,66)=19.35, p<0.0001). When participants did not receive any instruction, all participants selected sanctions that punished the offender (M=1.35, SD=0.43) more than sanctions that fulfilled any other justice goal (all ps<0.0001). Participants chose an equal number of sanctions that could restore the victim (M=0.97, SD=0.51) and rehabilitate the offender (M=0.91, SD=0.57), t<1. And participants tended to select sanctions that would restore the community (M=0.74, SD=0.57) over those that would reinforce the values of the community (M=0.55, SD=0.46), t(71)=1.98, p=0.052. Participants were less interested in reinforcing community values than any other justice goal.

When participants were instructed to focus on either the offender, the victim, or the community, there was an interaction between justice goal and target focus, F(8,134)=2.28, p<0.03. When participants thought about the offender, as with the default selections, they selected more sanctions that would punish the offender (M=1.31) than for any other justice goal, all ps<0.05. When participants were instructed to think about the victim, however, they chose an equal number of sanctions that were aimed at restoring the victim (M=1.13) as they did of those that punished the offender (M=1.08), t<1. These proportions were higher than all of the remaining justice goals (ps<0.0001). For those participants who thought about the community, as with those who thought about the offender, they selected more sanctions that would punish the offender (M=1.25) than for any other justice goal, all ps<0.06. However, unlike those who thought about the offender, participants who focused on the community selected an equal number of sanctions that would restore the community (M=0.83) as they did of those that would rehabilitate the offender (M=0.92), t<1. This result stands in contrast to participants who focused on the offender, as they chose more sanctions to rehabilitate the offender than to restore the community (M=1.02 vs. M=0.71, t(23)=2.46, p<0.03).

Discussion

These results indicate how the targets that people focus on when thinking about wrongdoing can affect which justice goals people feel are necessary to achieve justice. Moreover, the sanction-assigning methodology used in this study can illuminate these effects without asking people to explicitly report their justice goals. When people focused on the offender, they did not shift their responses from their initial, default choices, which provides evidence that people primarily think about handling wrongdoing with regard to punishing the offender. However, the results show that people do want to achieve justice for both the victim and the community if their attention is drawn to these justice targets. When people focused on the victim, they wanted more sanctions that would restore the victim and fewer sanctions that would address the offender and community-based goals. In fact, the importance of restoring the victim became equal to that of punishing the offender. When participants focused on the community, they wanted more sanctions that would restore the community and reinforce its values and fewer sanctions that would address the offender- and victim-based goals.

Interestingly, when people shift their focus to think about either the victim or the community, punishing the offender still remains the most important justice goal (although for those who thought about the victim, it shared this distinction with the goal of restoring the victim). This result, along with the lack of change from the default responses of those who thought about the offender, indicates that punishing the offender is an essential component of achieving justice in the face of wrongdoing. However, the other justice goals can increase in importance when people take the time to consider how the victim and the community have been affected by the crime. This is particularly so when people think about the victim, which may be because of the salience of the victim in the crime description, as well as the ease of taking on one person's perspective rather than that of a community entity.

Finally, although the sanction-assigning methodology provides a means of avoiding people's self-reports of how necessary the different justice goals are, some issues with this methodology should be addressed. It is possible that people aimed to achieve more than one justice goal through the assigning of a single sanction. For example, people may have chosen restitution to primarily restore the victim, but they may have also wanted to use this sanction as a means of punishing the offender. For statistical clarity, we only allowed certain sanctions to count for one justice goal (e.g., restitution for restoring the victim, and not for punishing the offender), based on the higher percentage of participants who selected it as fulfilling that justice goal in Study 2. Future research should explore whether the assigning of a sanction can be linked to a single dominant justice goal or whether the assigning of sanction indicates an interest in fulfilling multiple justice goals.

General Discussion

The present studies indicate that people recognize the need for more than the punishment of offenders to achieve justice. Study 1 demonstrates that people report an interest in satisfying multiple justice goals, rather than solely punishing the offender. Study 2 reveals that people view a variety of different sanctions as differentially able to fulfill these multiple goals. In Study 3, these results are used to demonstrate that the justice target people focus on—the offender, the victim, or the community—influences which goals people believe need to be fulfilled to achieve justice. When participants thought about how the victim or the community was affected by the crime, they chose sanctions that addressed justice goals associated with these targets. Overall, these studies show that people would like to fulfill multiple justice goals when faced with intentional wrongdoing.

This work tests two primary predictions. The first is that people should show a concern with the offender (and his or her punishment) regardless of situational variation. In Study 1, we found that regardless of offense features, participants felt that the punishment of the offender was required to achieve justice. In Study 3, we showed the sanctions that people assign do tend, by default, to focus on punishing the offender, rather than the victim or the community. The justice goals that people chose to fulfill did not change from their initial choices when they were instructed to think about the offender. However, when people focused on the victim or the community, they still showed concern for punishing the offender, as well as their respective target of focus. The resistance to situational variation, and the reliance on offender-targeted retributive sanctions in a default mode, both indicate that an invariant and central component of people's response to wrongdoing is to focus on the offender and to desire his or her punishment (rather than rehabilitation).

These studies also corroborate our second hypothesis, that when people's attention is drawn to the victim or the community, they will want to address concerns related to these justice targets in addition to punishing the offender. We found that the extent to which people desire to fulfill multiple justice goals is dependent on situational factors, such as the features of the offense and the context in which people evaluate crimes. Specifically, Studies 1 and 3 demonstrate that the salience of the justice target (the offender, the victim, or the community), whether determined by prominent features of a crime or the perspective of the participant, plays a role in determining which goals people feel are important to achieving justice. These results are consistent with previous research illustrating the importance of situational factors to people's justice judgments (Reference TylerTyler et al. 1997; Reference WeinerWeiner et al. 1997), and they illustrate how increasing the salience of the nondefault targets may cause people to accommodate more than one justice target when responding to wrongdoing.

Although these results illustrate that people are concerned with other justice targets and goals beyond punishing the offender, these studies did not explicitly require people to make trade-offs, or compromises, between different justice goals. People could accommodate multiple justice goals without making concessions on individual sanctions, such that they could assign both retributive (e.g., prison) and restorative (e.g., the victim receiving an apology from the offender) measures without having to compromise on the “amount” of either sanction that was assigned. The question remains open as to how people would react if they had to make explicit trade-offs with punishment to fulfill other justice goals. According to Tetlock's Value Pluralism Model (Reference TetlockTetlock 1986, Reference Tetlock and Lupia2000; Reference Tetlock, Peterson, Lerner and SeligmanTetlock, Peterson, & Lerner 1996), people do not like to make choices that involve making compromises between values. However, people are willing to make value trade-offs when they realize that two or more important values are in conflict with each other. If people view two justice goals as being equally important to fulfill (such as punishing the offender and restoring the victim), they may thus be willing to engage in trade-offs between these goals in order to accomplish both of them. Future research is needed to test this hypothesis.

It is important to note that these studies deal with cases of intentional wrongdoing. When wrongdoers lack intent (such as for accidental harms, cases of negligence, and mental insanity), people's desire to punish will be mitigated (Reference DarleyDarley et al. 2000; Reference Darley and PittmanDarley & Pittman 2003). Indeed, even when intentional harms are low in severity, people may be more focused on other justice goals, such as restoration of the victim (Reference Doble and GreeneDoble & Greene 2000; Reference Gromet and DarleyGromet & Darley 2006; Reference Roberts and StalansRoberts & Stalans 2004). There was evidence of this in Study 1, as people viewed more of these alternative justice goals as being equal in importance with punishment for offenses that were low, rather than high, in severity.

The Focus on Punishment

The present results indicate that in order to have a more complete understanding of how people believe that justice can be achieved, we need to know more than simply the extent to which people want to punish the offender. People are open to the fulfilling of multiple justice goals as a means of achieving justice. Why, then, have previous studies shown that people are satisfied with simply punishing the offender in response to wrongdoing? We believe there are a number of possible explanations for this finding.

One explanation is that many investigators have failed to ask participants to indicate whether they would want to have goals fulfilled that target the victim and the community. People do not have a means to express concern with these justice targets. The results from Studies 1 and 3 demonstrate that when people were given the opportunity to express a concern with more than punishing the offender, they were also interested in fulfilling justice goals that addressed the salient targets in the situation. In addition, other studies have shown that people appear to be more punitive than they truly are due to the types of questions they are asked (Reference Doob, Roberts, Walker and HoughDoob & Roberts 1988; Reference McGarrell and SandysMcGarrell & Sandys 1996). For instance, Reference McGarrell and SandysMcGarrell and Sandys (1996) found that people did support the death penalty when given a dichotomous choice between supporting the death penalty or not, but this support was greatly reduced when participants were also given the option of life without parole. More pertinent to the present research, this support was even further reduced when participants were presented with the option of life without parole combined with restitution to victims' families. By focusing solely on retribution and punitiveness, investigators overlook other actions that people feel could achieve justice.

Another explanation is that people's intuitions direct them toward focusing on punishing the offender. If people's intuitive response to wrongdoing is to punish the offender in proportion to the severity of the offense, then this judgment should dominate people's reactions to intentional wrongdoing. This can be conceptualized in terms of a dual process account. There are a number of dual process accounts (Reference Chaiken and TropeChaiken & Trope 1999), but their shared characteristic is the assertion that people can think and react to the same stimuli in both automatic and controlled ways. One of these accounts, the Intuitive System/Reasoning System model advanced by Kahneman and colleagues (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2003; Reference Kahneman, Frederick and GilovichKahneman & Frederick 2002), is particularly relevant to the present results. According to this model, an intuitive, rapidly produced (automatic) response will only be adjusted or overridden by a controlled reasoning process if the reasoning system detects an error with the intuitive judgment. If the reasoning system does not detect an error, or is impaired due to time, cognitive load, or motivation constraints, then the intuitive judgment is likely to remain and be acted on.

Applying this model to the present findings, people's intuitive, automatic response to intentional wrongdoing is to punish the offender. And if people are given no cues about the victim and the community when asked to respond to wrongdoing, then their controlled reasoning system will not be signaled to intervene and adjust their intuitive response to punish. Therefore, although people's intuitive system relies on punishment alone, their more controlled reasoning system considers other justice goals to be important to the achievement of justice as well. There is evidence of this in Study 3: when people were not instructed on which target to focus, they predominantly chose sanctions that addressed punishing the offender. Study 3 also demonstrates that this intuitive response can be adjusted if people are given the opportunity to think about how the victim and the community have been affected by the offense. More research is needed to determine whether a concern with the victim and the community is indeed the product of a more effortful, reasoned process than the desire to punish the offender, but it is a plausible explanation for some of our results.

Justice Goals, Justice Targets, and Offense Sanctions

The present studies explored five different justice goals that addressed three different targets: punishing and rehabilitating the offender, restoring the victim, reinforcing community values, and restoring the community. This is, of course, not an exhaustive list of justice goals that people may want to see achieved. For our current purposes, we were interested in these five justice goals because they address the three possible justice targets (offender, victim, and community) through both retributive (punishing the offender and reinforcing community values) and restorative (rehabilitating the offender, and restoring the victim and the community) means.

As discussed at the beginning of the article, these two types of justice responses are typically framed as mutually incompatible. Our findings indicate, however, that these responses may not be entirely distinct from each other. Throughout the current studies, participants chose to fulfill both retributive and restorative goals simultaneously. This pattern was most clear for the retributive goal of punishing the offender and the restorative goal of restoring the victim. For crimes in which the victim was salient in Studies 1 and 3, participants demonstrated an equal concern for restoration of the victim as they did for punishment of the offender. These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating that when provided with the opportunity, people will choose to use both retributive and restorative measures to achieve justice (Reference Gromet and DarleyGromet & Darley 2006). It appears that people believe that fulfilling both retributive and restorative measures simultaneously allows for justice to be achieved.

In addition, one issue for the study of multiple justice goals is the degree of overlap between the different goals. This overlapping is most evident in the Study 2 finding that people viewed individual sanctions as accomplishing more than one justice goal. For instance, the offender repaying the victim for any financial loss the victim incurred as a result of the crime (restitution) was seen as both restoring the victim and punishing the offender. These results are consistent with previous research that has demonstrated that people's use of one sanction can be associated with more than one justice goal (e.g., Reference Wenzel and ThielmannWenzel & Thielmann 2006). Furthermore, it has been argued that the achievement of some justice goals may be dependent on the achievement of another, such as that part of restoring the victim is seeing that the offender is punished for the wrongs the offender committed against the victim (e.g., Reference BartonBarton 1999). For experimental purposes, it would certainly be preferable for each sanction and each justice goal to be entirely separate entities. However, it appears that these constructs may be at least somewhat overlapping, and future research should take this into account when attempting to draw distinctions between justice goals.

Policy Implications

The policy implications of the observed preference for multiple justice goals are potentially far-reaching, particularly with regard to the criminal justice system. The present research has focused on how people feel that justice can be achieved through the satisfaction of multiple justice goals. Taking public perceptions into account for criminal justice policies is important for two reasons. First, people are more likely to grant legitimacy to the criminal justice system if they feel the system employs morally correct practices (Reference Robinson and DarleyRobinson & Darley 1995; Reference TylerTyler 2006). Second, citizen support for sanctioning systems is important to legislators who are responsible for enacting changes to the system, as legislators will be reluctant to make changes that are not supported by their constituents (Reference Roberts and StalansRoberts & Stalans 2004). The present results indicate that people would support a system that does not rely solely on punitive, retributive measures to achieve justice.

It is also possible that such a system could produce a more efficient and effective justice system. Currently, the American criminal justice system assigns extremely long prison sentences to offenders and incurs very high costs to incarcerate people for longer and longer periods of time (Reference Robinson and DarleyRobinson & Darley 2004) as compared to other Western societies. A pressing question, then, is whether the fulfilling of multiple justice goals could lead to less reliance on prison as a means of achieving justice. If multiple sanctions (that tap different justice goals) had been assigned to deal with the different aspects of one offense, would people find it acceptable to reduce the prison sentence that would have been assigned? As has been argued elsewhere (Reference Gromet and OswaldGromet in press), we contend that the answer to this question is yes. If there is only a prison sentence available for the repairing of the number of different harms that crime causes, then people are likely to favor lengthy prison sentences in an attempt to satisfy a number of goals. If multiple remedies are available, however, this should lead to a reduction in the extent to which the prison sentence is used to accomplish multiple justice goals. This in turn may lead to a reduction in the length, or even the use, of costly prison terms.

Although evidence exists that people are willing to reduce punitive measures for offenders who also complete restorative sanctions (Reference Gromet and DarleyGromet & Darley 2006; Reference McGarrell and SandysMcGarrell & Sandys 1996), further empirical research is needed to determine whether access to multiple sanctions does in fact lead people to reduce the length of prison sentences. Future research should also explore which specific factors motivate people's prison sentence reductions. We have posited above that fulfilling multiple justice goals should reduce people's use of prison sentences (essentially, an argument for the hydraulic nature of these justice goals). It is also possible that when an offender completes restorative sanctions (such as apologizing to the victim and completing community service), these acts change people's conception of the offender from an out-group deviant who “deserves” a long prison sentence to a person who is now part of the in-group and for whom a severe prison term is no longer fitting (see Reference WenzelWenzel et al. 2008 for a discussion of how group identity may affect people's desire for restoration and retribution).

We acknowledge that providing participants with multiple sanctions to choose from may not be an entirely accurate reflection of how societies handle crimes. For many crimes, and most serious offenses, the current American criminal justice system is similar to most of the studies on people's responses to wrongdoing: the severity of the prison sentence is the primary option available. However, court systems around the world have begun to incorporate alternative types of justice procedures, often with a restorative justice orientation. Alternatives such as these are consistent with the concept of multiple justice goals, as they provide people with the option to address additional justice concerns beyond punishment. Therefore, with the increasing incorporation of alternative procedures, investigating people's perceptions of achieving justice through the fulfilling of multiple goals gains an added relevance and importance.

Political Identification

Another topic for further research concerns how individual differences, particularly political identification, may influence how acceptable people find a multiple-sanction system (that fulfills multiple justice goals and reduces the system's primary focus on punishment). Ideological differences have been shown to influence a number of psychological phenomena, including preference for the status quo and tolerance of inequality (Reference JostJost et al. 2003). Perhaps most relevant, Carroll and colleagues (Reference CarrollCarroll et al. 1987) have demonstrated that people tend to have one of two distinct bundles of attitudes with regard to people's sentencing goals: one that is more conservative (punitive) and one that is more liberal (rehabilitative).

The present studies, which use college students as participants (most of whom identified as liberal), do not provide an appropriate population to test for how ideological differences may influence people's support for fulfilling multiple justice goals.Footnote 5 More research is needed on how political identification influences people's desire to fulfill justice goals beyond punishment, and whether differences that may be chronically present between different ideologies may be moderated by situational and attentional variables.