Impact statements

Mental health and Humanitarian Emergencies are global issues, affecting over 200 million school-aged children and young people, placing them at risk of developing mental health conditions (Wait, Reference Wait2022; UNICEF, 2023). Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) programmes, aiming to protect, promote, prevent and/or treat mental health conditions, are considered as a key priority by international actors in humanitarian emergencies. In recent years, there have been growing interests to explore the impact of MHPSS on children and young people. Contributing to this effort, we identified 43 randomised controlled trials evaluating different types and modalities of MHPSS on a wide range of outcomes. Overall, MHPSS programmes that explicitly link thoughts, emotions, feelings and behaviour, such as cognitive behavioural programmes, can potentially improve depression symptoms. Additionally, narrative exposure therapy may contribute to the reduction in feelings of guilt. Psychosocial programmes involving creative activities indicate potential unintended effects on depression. However, evidence regarding the impact of other MHPSS modalities remains inconclusive. The lack of clear and consistent findings across MHPSS modalities underscores the importance of gaining an understanding how implementation contexts and socio-cultural dimensions may, directly and indirectly, impact children and young people’s mental health and well-being. This systematic review highlights the importance of tailoring MHPSS programmes to diverse needs in order to safely and effectively promote, prevent and treat mental health conditions in children and young people affected by humanitarian crises in low- and middle-income countries.

Introduction

In recent years, millions of children and young people worldwide have been affected by extreme weather episodes, migration, conflicts, forced displacement and global public health emergencies, including COVID-19 (UNICEF, 2021). Many of them are displaced from their homes and separated from their parents and guardians, at risk of being recruited into their national armed forces, or exposed to adverse childhood experiences, including violence, serious physical injuries and extreme poverty (Bennouna et al., Reference Bennouna, Stark, Wessells, Song and Ventevogel2020; Ceccarelli et al., Reference Ceccarelli, Prina, Muneghina, Jordans, Barker, Miller, Singh, Acarturk, Sorsdhal and Cuijpers2022). Repeated, sudden or prolonged exposures to these traumatic events can have a severe and long-term impact on their mental health and well-being (Miller and Jordans, Reference Miller and Jordans2016; Ataullahjan et al., Reference Ataullahjan, Samara, Betancourt and Bhutta2020). Children and young people living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) often are less prepared and have limited access to basic services and essential resources to respond to humanitarian emergencies.

Mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) is increasingly considered an essential element of humanitarian responses to support children and young people affected by humanitarian crises in LMICs (Meyer and Morand, Reference Meyer and Morand2015). International organisations, such as UNICEF, consider MHPSS as a priority, aiming to enhance the implementation of MHPSS across humanitarian sectors (UNICEF, 2019). Similarly, the WHO-funded Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) has introduced guidelines for MHPSS implementation in emergencies, providing a framework to understand different layers of programming and valuable activities to facilitate the development of effective, evidence-based MHPSS across agencies and practices (IASC, 2007b).

Several systematic reviews have explored the impact of MHPSS on mental health outcomes in children and young people affected by humanitarian crises (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Tol, Komproe and De Jong2009; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Song and Jordans2013; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Pigott and Tol2016; Brown et al., Reference Brown, de Graaff, Anne, Annan and Betancourt2017; Morina et al., Reference Morina, Malek, Nickerson and Bryant2017; Bosqui and Marshoud, Reference Bosqui and Marshoud2018; Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon, Gordon, O’callaghan, Papola, Peltonen, Punamaki, Richards, Staples, Unterhitzenberger, Van, De, Jordans, Tol and Barbui2018b; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Smallegange, Coetzee, Hartog, Turner, Jordans and Brown2019; Barbui et al., Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton, Gastaldon, Gureje, Hanlon, Jordans, Lund, Nose, Ostuzzi, Papola, Tedeschi, Tol, Turrini, Patel and Thornicroft2020; Kamali et al., Reference Kamali, Munyuzangabo, Siddiqui, Gaffey, Meteke, Als, Jain, Radhakrishnan, Shah, Ataullahjan and Bhutta2020; Papola et al., Reference Papola, Purgato, Gastaldon, Bovo, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2020; Pfefferbaum et al., Reference Pfefferbaum, Nitiéma and Newman2020; Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Tedeschi, Betancourt Theresa, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon, Gordon, O’callaghan, Papola, Peltonen, Punamaki, Richards, Staples Julie, Unterhitzenberger, Jong, Jordans Mark, Gross Alden, Tol Wietse and Barbui2020; Uppendahl et al., Reference Uppendahl, Alozkan-Sever, Cuijpers, de Vries and Sijbrandij2020; Galvan et al., Reference Galvan, Lueke, Mansfield and Smith2021). In general, most reviews indicate a positive impact of psychological and psychosocial interventions on post-traumatic symptoms in children and young people. However, the effect of MHPSS on internalised symptoms such as depression and anxiety remains uncertain. Purgato and colleagues (2018), in their individual patient data meta-analysis, observed no impact of the focused psychosocial interventions on depression and anxiety. In contrast, the Uppendahl study (2020) suggested that psychological and psychosocial interventions had a positive effect on the combined outcomes of post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD), depression and anxiety. Moreover, MHPSS programmes evaluated in previous reviews were tailored to the varied needs of children and young people in humanitarian contexts. This complex nature of MHPSS programming poses a challenge in identifying effective modalities. Recent evidence reviews on health interventions during humanitarian crises have recommended future research to enhance understanding of the effectiveness and implementation of different MHPSS modalities for diverse populations including children (Barbui et al., Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton, Gastaldon, Gureje, Hanlon, Jordans, Lund, Nose, Ostuzzi, Papola, Tedeschi, Tol, Turrini, Patel and Thornicroft2020; Doocy et al., Reference Doocy, Lyles and Tapis2022). Given the considerable number of children and young people in need of MHPSS in humanitarian emergencies in LMICs, this systematic review is timely. It builds on existing literature, by systematically describing the current research landscape and the nature of existing MHPSS modalities evaluated and delivered to children and young people affected by humanitarian emergencies in LMICs. We also examine the effects and potential adverse consequences to inform policy and practice in LMICs.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We carried out a systematic review of research evidence following PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, Mcdonald, McGuinness, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021). We searched 12 bibliographic databases across disciplines and specialist databases: Medline, ERIC, PsycINFO, Econlit, Cochrane Library, IDEAS, IBSS, CINHAL, Scopus, ASSIA, Web of Science and Sociological Abstracts. Both published and unpublished studies were comprehensively searched from the websites of relevant organisations. We searched the citations of included studies and relevant systematic reviews. Search strategies were informed by the scoping exercise (Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Felix, Chiumento and Dickson2016) and were developed based on three key concepts (mental health and psychosocial support, humanitarian emergencies and study designs). The search was first performed in November 2015 and updated and finalised in May 2023 (see S1 for the example of database search strategies and a list of websites searched). We included studies that aimed to evaluate the impact of MHPSS programmes on mental health and well-being of children and young people aged at or below 25, who were affected by humanitarian emergencies in LMICsFootnote 1 MHPSS programmes were broadly defined as interventions seeking to ‘provide or promote psychosocial well-being and/or prevent or treat mental health disorder’ p. 1, (IASC, 2007b). We included only experimental studies with control groups that were published in English in or after 1980 (see S2 for eligibility criteria). Two reviewers (MB and KD) piloted the eligibility criteria. A pilot screening exercise was performed by the review team members (MB, LF, KD, FS, ZD, AJ) before independently screening the studies on titles and abstracts. Any discrepancies identified during both the pilot and independent screening were addressed through discussions between the reviewers. When there was insufficient information, full reports were obtained to assess the eligibility for inclusion.

The data extraction tool, developed and piloted by two reviewers (MB, KD), aimed to collect information on key characteristics of MHPSS programmes, implementation strategies, study design, findings and conclusions. Three reviewers (MB, FS, PD) independently extracted information from eligible studies, and the second reviewer carried out a consistency check of all included studies using EPPI-Reviewer (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Graziosi, Brunton, Ghouze, O’driscoll and Bond2020). Four reviewers (MB, FS, PD, LF) assessed the risk of bias of the studies included in the synthesis using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (RoB2) (Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe, Boutron, Cates, Cheng, Corbett, Eldridge, Emberson, Hernán, Hopewell, Hróbjartsson, Junqueira, Jüni, Kirkham, Lasserson, Li, McAleenan, Reeves, Shepperd, Shrier, Stewart, Tilling, White, Whiting and Higgins2019) and cluster randomised controlled trials (cRCTs) (RoB 2 for cRCTs) (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Campbell, Campbell, Drahota, Giraudeau, Higgins, Reeves and Seigfried2017). The overall quality of the included studies was subsequently judged as a high risk of bias, some concerns or a low risk of bias according to RoB 2 framework. We resolved any disagreements by discussing and consulting with a third review member when required. The review protocol was registered at PROSPERO database (CRD42016033578).

Data analysis

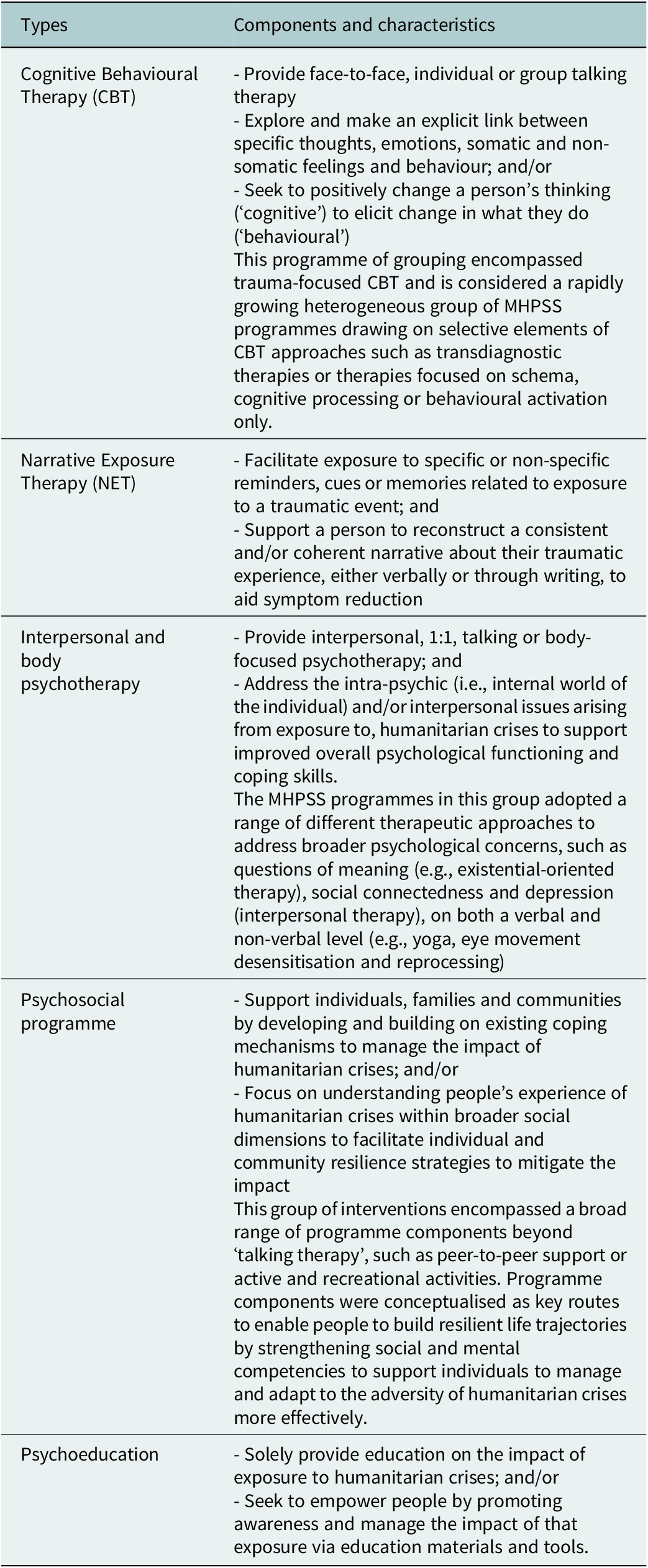

We first narratively described the key characteristics of all included studies. We included only RCTs and cRCTs. We classified types of MHPSS into five broad domains, including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), narrative exposure therapy (NET), interpersonal and body psychotherapy modalities, psychosocial programmes and psychoeducation (see Table 1) (Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Felix and Dickson2019). The iterative process of MHPSS programme classification was undertaken. We read the description of the MHPSS programmes described by the authors of the included studies and then matched the programme descriptions against pre-defined programme definitions developed by the current review team. When appropriate, the meta-analysis was performed on conceptually similar outcome measures reported in more than one study using a random effect model. The pooled standardised mean difference (SMD) effect sizes were estimated and presented in forest plots with a 95% confidence interval (CI). We extracted outcome data at the longest follow up timepoint. When we included cRCTs, we checked whether the outcome data had been adjusted for intra-cluster correlation (ICC). In cases where studies did not report ICC, we used the ICC data based on other included studies. We assessed the extent of heterogeneity using I2 statistics to quantify the magnitude of statistical heterogeneity and tested the statistical significance of heterogeneity using Q statistics. We ran a meta-analysis using STATA version 17.

Table 1. Types of MHPSS programmes

Results

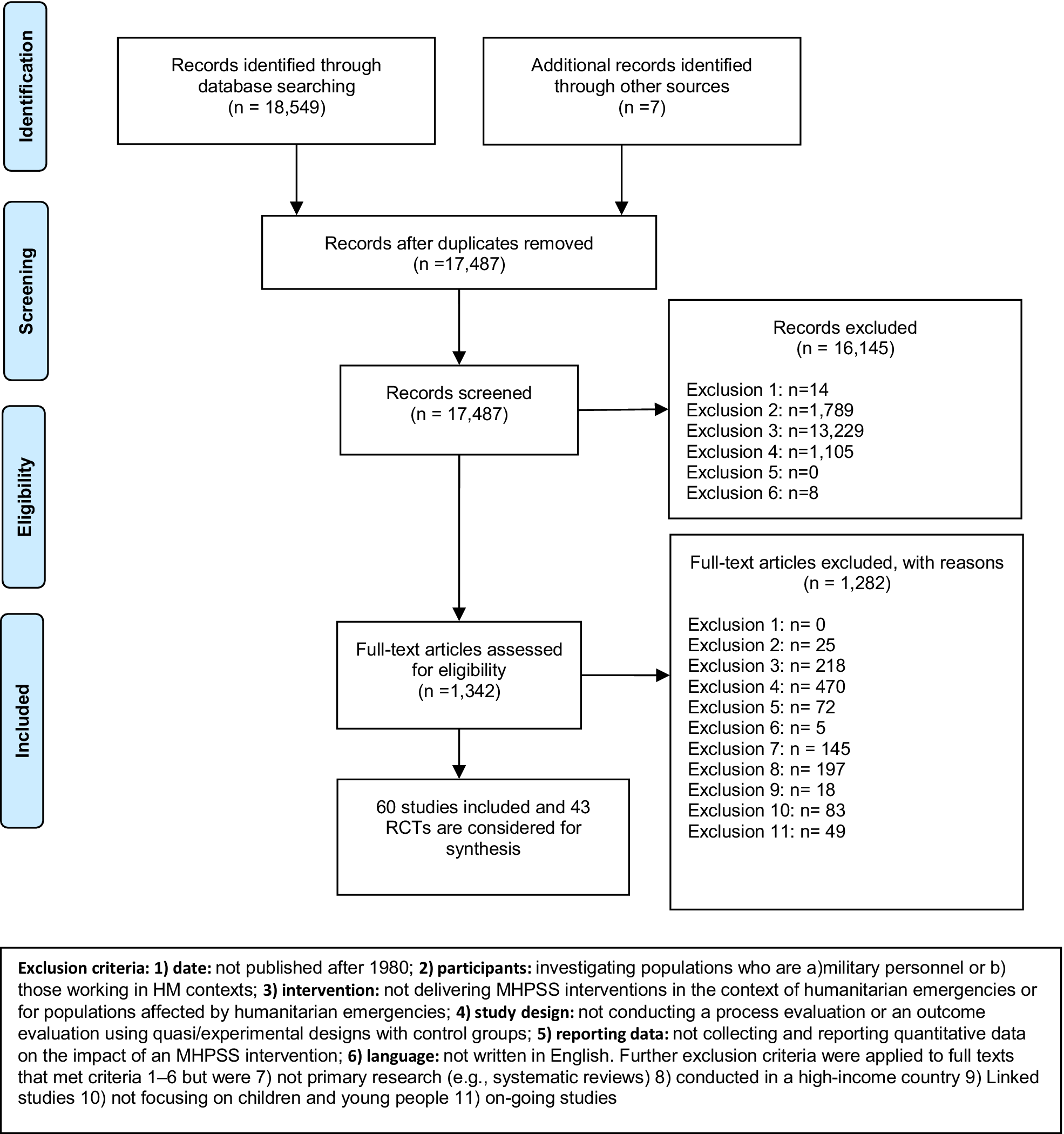

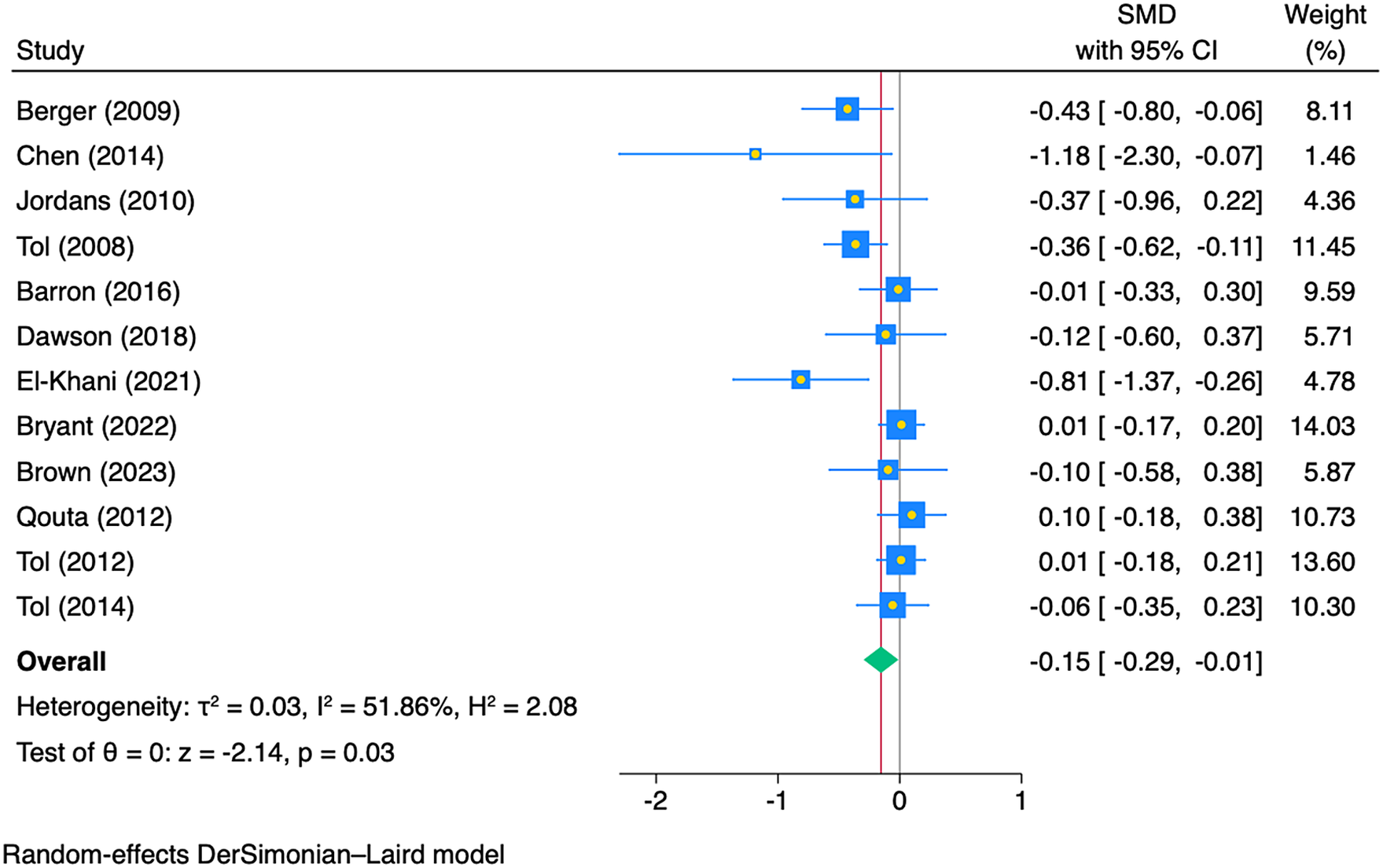

We identified 18,556 records. 16,822 records were screened on title and abstract. 1,342 records were rescreened based on full-text reports. A total of 60 studies were included in the review, and 43 RCTs and cRCTs were considered for the synthesis (see Figure 1). Twelve electronic databases, key websites and citation checking were undertaken. Forty-three RCTs published in English between January 1980 and May 2023 were included in the review. Overall, the findings suggest that cognitive behavioural therapy may improve depression symptoms in children and young people affected by humanitarian emergencies (pooled ES = -0.15; 95% CI (−0.29, −0.01), I2 = 51.86%). Narrative exposure therapy may reduce feelings of guilt (pooled ES = −0.43, 95% CI (−0.79, −0.07), I2 = 0%). However, the impact of the other MHPSS modalities across outcomes is inconsistent. In some contexts, providing psychosocial programmes involving creative activities may increase the symptoms of depression in children and young people. These findings emphasise the need for the development of MHPSS programmes that can safely and effectively address the diverse needs of children and young people living in adversarial environments.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart.

Forty-two (70%) of 60 studies were published since 2010. Most studies were conducted in the Middle East and Asia (n = 36, 60%) and 19 (33.33%) in sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the research evidence (n = 49) was conducted in war and conflict settings. One-fifth of the studies (n = 11) evaluated the impact of MHPSS programmes on displaced and refugee children (Dybdahl, Reference Dybdahl2001; Thabet Abdel et al., Reference Thabet Abdel, Vostanis and Karim2005; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011; Kalantari et al., Reference Kalantari, Yule, Dyregrov, Neshatdoost and Ahmadi2012; Lange-Nielsen et al., Reference Lange-Nielsen, Kolltveit, Thabet, Dyrgrove, Pallesen, Johnson and Laberg2012; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Jones, Berrino, Jordans, Okema and Crow2012; Annan et al., Reference Annan, Sim, Puffer, Salhi and Betancourt2017; Sirin et al., Reference Sirin, Plass Jan, Homer Bruce, Vatanartiran and Tsai2018; Yankey and Biswas Urmi, Reference Yankey and Biswas Urmi2019; Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol2021). Nearly one-quarter investigated the impact of MHPSS programmes on children and young people affected by natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunami (Goenjian et al., Reference Goenjian, Walling, Steinberg, Karayan, Najarian and Pynoos2005; Schauer von, Reference Schauer Von2008; Shooshtary et al., Reference Shooshtary, Panaghi and Moghadam2008; Berger and Gelkopf, Reference Berger and Gelkopf2009; Catani et al., Reference Catani, Kohiladevy, Ruf, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2009; SHoaakazemi et al., Reference Shoaakazemi, Momeni, Ebrahimi and Khalilid2012; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014; Cluver, Reference Cluver2015; Pityaratstian et al., Reference Pityaratstian, Piyasil, Ketumarn, Sitdhiraksa, Ularntinon and Pariwatcharakul2015; Akiyama and Gregorio Ernesto, Reference Akiyama, Gregorio Ernesto and Kobayashi2018; Cleodora et al., Reference Cleodora, Mustikasari and Gayatri2018; Dhital et al., Reference Dhital, Shibanuma, Miyaguchi, Kiriya and Jimba2019; Nopembri et al., Reference Nopembri, Sugiyama, Saryono and Rithaudin2019). The majority of the studies assessed the impact of MHPSS programmes in the aftermath of disasters. Only four studies aimed to measure the impact of MHPSS programmes on young women and girls (SHoaakazemi et al., Reference Shoaakazemi, Momeni, Ebrahimi and Khalilid2012; O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty and Black2013; Robjant et al., Reference Robjant, Koebach, Schmitt, Chibashimba, Carleial and Elbert2019; Ahmadi et al., Reference Ahmadi, Jobson, Musavi, Rezwani, Amini, Earnest, Samim, Sarwary, Sarwary and McAvoy2023) and only one study focused on former child soldiers and war-affected boys (McMullen et al., Reference McMullen, O’callaghan, Shannon, Black and Eakin2013). Most MHPSS programmes were delivered in school or classroom. Additional locations included the community (Khamis and Coignez, Reference Khamis and Coignez2004; Loughry et al., Reference Loughry, Ager, Flouri, Khamis, Afana and Qouta2006; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Jones, Berrino, Jordans, Okema and Crow2012; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Mcbain, Newnham, Akinsulure-Smith, Brennan, Weisz and Hansen2014; Annan et al., Reference Annan, Sim, Puffer, Salhi and Betancourt2017; Panter-Brick et al., Reference Panter-Brick, Dajani, Eggerman, Hermosilla, Sancilio and Ager2018; Sirin et al., Reference Sirin, Plass Jan, Homer Bruce, Vatanartiran and Tsai2018; Robjant et al., Reference Robjant, Koebach, Schmitt, Chibashimba, Carleial and Elbert2019; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Taha, Steen, Kane, Gillman, Aoun, Malik, Bryant, Sijbrandij and El Chammay2023), refugee camps (Khamis and Coignez, Reference Khamis and Coignez2004; Thabet Abdel et al., Reference Thabet Abdel, Vostanis and Karim2005; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011; Lange-Nielsen et al., Reference Lange-Nielsen, Kolltveit, Thabet, Dyrgrove, Pallesen, Johnson and Laberg2012; Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol2021), family home (Dybdahl, Reference Dybdahl2001; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Thurman, Rice, Boris, Ntaganira, Nyirazinyoye, De Dieu and Snider2009; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014), outdoor areas (Richards et al., Reference Richards, Foster, Townsend and Bauman2014; Pityaratstian et al., Reference Pityaratstian, Piyasil, Ketumarn, Sitdhiraksa, Ularntinon and Pariwatcharakul2015; Akiyama and Gregorio Ernesto, Reference Akiyama, Gregorio Ernesto and Kobayashi2018) or within church settings (O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, Branham, Shannon, Betancourt, Dempster and McMullen2014). The majority of MHPSS programmes (n = 50, 83.33%) were conducted in group settings, while four (6.7%) were delivered in group and individual formats. Of 60 studies, 22 studies evaluated the impact of CBT; 20 studies evaluated psychosocial programmes. Other studies focused on NET (n = 10), psychoeducation (n = 3) and other interpersonal and body psychotherapy modalities (n = 11). Eight studies evaluated more than one MHPSS model.

Approximately three-quarters of the MHPSS programmes included in the review provided advice and support to children and young people by sharing dialogue and discussing experiences within groups or with specialists. Other implementation strategies included exercise, drawing, arts and crafts, relaxation and breathing techniques. Some included social activities such as sports, games, drama, film or providing life skill training. Several MHPSS programmes were designed to engage with carers and work with teachers and school management, and/or the wider community. MHPSS programme implementation varied in terms of intensity and duration. Nevertheless, MHPSS programmes designed for children and young people in low-resource, humanitarian settings were typically delivered between four to 15 sessions (n = 37), each lasting approximately 60–120 min (n = 31). Five MHPSS programmes were delivered in multiple sessions, spanning one school year or more (Layne Christopher et al., Reference Layne Christopher, Saltzman William, Poppleton, Burlingame Gary, Pasalic, Durakovic, Music, Campara, Apo, Arslanagic, Steinberg Alan and Pynoos Robert2008; Peltonen et al., Reference Peltonen, Qouta, El Sarraj and Punamaki2012; Nopembri et al., Reference Nopembri, Sugiyama, Saryono and Rithaudin2019; Torrente et al., Reference Torrente, Aber John, Starkey, Johnston, Shivshanker, Weisenhorn, Annan, Seidman, Wolf and Dolan2019; Yankey and Biswas Urmi, Reference Yankey and Biswas Urmi2019).

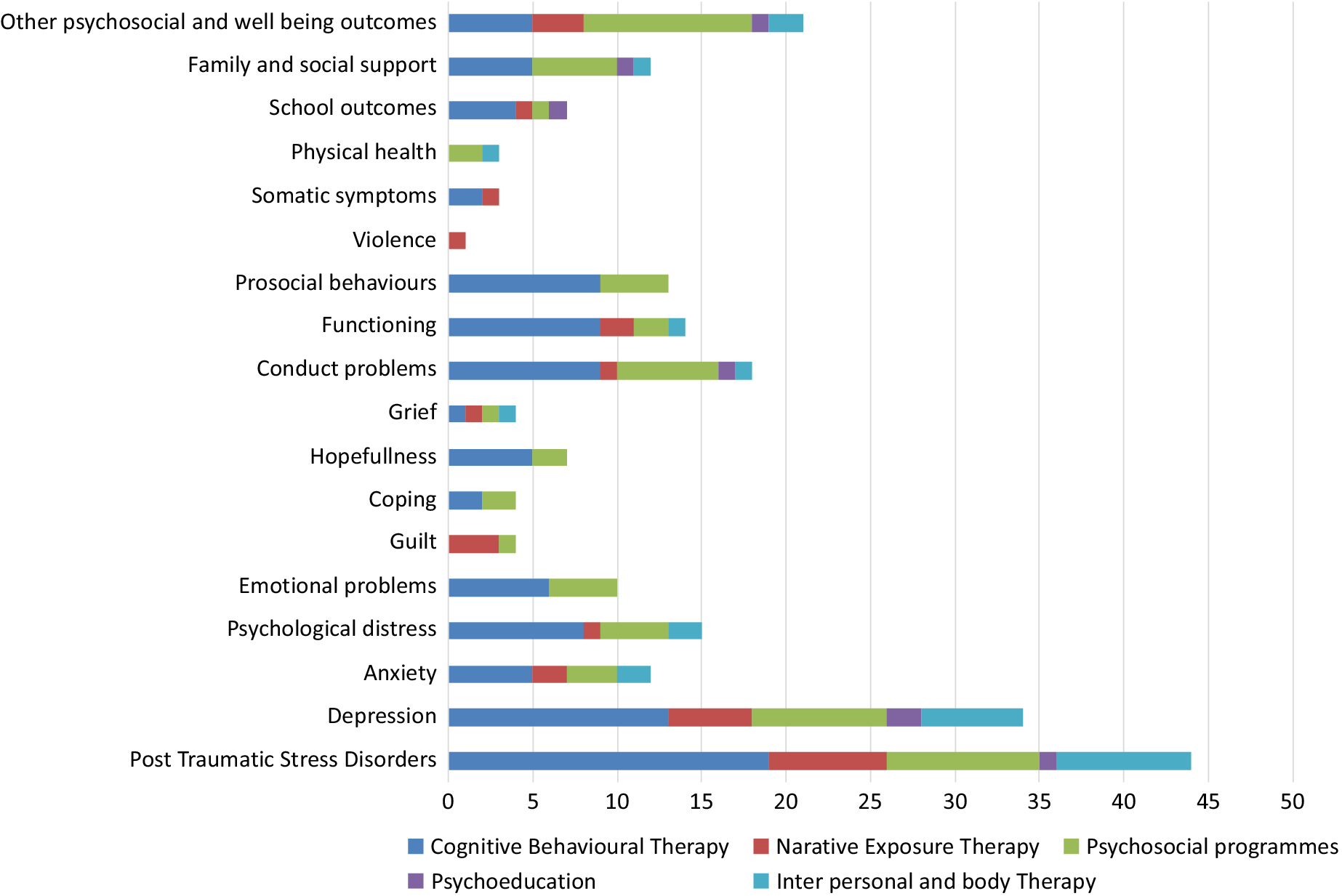

A wide range of outcomes was used to assess the impact of MHPSS programmes (see Figure 2). The most commonly reported mental health measures were PTSD (n = 41 studies, 68%) and depression (n = 31 studies, 51.67%). Other traumatic stress reactions and emotional well-being measures reported in more than ten studies included psychological distress, conduct problems, functioning, anxiety and prosocial behaviours. Other coping resources, such as family and social support outcomes, were reported in 13 studies. Less commonly reported outcome measures were emotional problems (n = 8), educational outcomes (n = 8), hopefulness (n = 7), guilt (n = 3) and grief (n = 4). We identified various tools used to measure the impact of MHPSS programmes. Nearly half of the included studies clearly explained whether and how the standardised instruments were translated into local languages or piloted for use in local settings. (the key characteristics of 60 studies are summarised in file S3).

Figure 2. Type of MHPSS programmes and outcomes*.

*More than one types of the MHPSS programmes can be evaluated in one study.

We included 43 RCTs in the synthesis. Of the 43 RCT studies, 12 studies were clustered RCTs, assigning the participants by school (Schauer von, Reference Schauer Von2008; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Komproe, Susanty, Jordans, Macy and de Jong2008; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Komproe, Jordans, Vallipuram, Sipsma, Sivayokan, Macy and de Jong2012; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Komproe, Jordans, Ndayisaba, Ntamutumba, Sipsma, Smallegange, Macy and de Jong2014; Dhital et al., Reference Dhital, Shibanuma, Miyaguchi, Kiriya and Jimba2019; Nopembri et al., Reference Nopembri, Sugiyama, Saryono and Rithaudin2019; Torrente et al., Reference Torrente, Aber John, Starkey, Johnston, Shivshanker, Weisenhorn, Annan, Seidman, Wolf and Dolan2019), class (Berger and Gelkopf, Reference Berger and Gelkopf2009; Qouta Samir et al., Reference Qouta Samir, Palosaari, Diab and Punamaki2012; Berger et al., Reference Berger, Benatov, Cuadros, Vannattan and Gelkopf2018) or local district (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Komproe, Tol, Kohrt, Luitel, Macy and de Jong2010; Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol2021). The most evaluated MHPSS programmes were CBT (n = 20) and psychosocial programmes (n = 12). We further classified the studies according to the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Guideline on MHPSS in Emergency Settings (IASC, 2007a). Two types of IASC MHPSS intervention pyramid were evaluated: one aimed to strengthen community and family support (Tier 2; n = 27), and the other focused on delivering focused, non-specialised supports to children and their families (Tier 3; n = 29). The majority of the included studies in the synthesis (n = 30, 69.76%) screened participants for mental health conditions before being enrolled in the study. Nearly all RCTs (n = 40) assessed the short-term impact (0–3 months) of MHPSS programmes with two studies assessing the impact of MHPSS programmes for more than 12 months (Schauer von, Reference Schauer Von2008; Torrente et al., Reference Torrente, Aber John, Starkey, Johnston, Shivshanker, Weisenhorn, Annan, Seidman, Wolf and Dolan2019). Twenty-four studies compared MHPSS programmes with waitlist control groups; six with active interventions and eight with Treatment As Usual (TAU), eight studies with no intervention (Kalantari et al., Reference Kalantari, Yule, Dyregrov, Neshatdoost and Ahmadi2012; SHoaakazemi et al., Reference Shoaakazemi, Momeni, Ebrahimi and Khalilid2012; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Mcbain, Newnham, Akinsulure-Smith, Brennan, Weisz and Hansen2014; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Foster, Townsend and Bauman2014; Berger et al., Reference Berger, Benatov, Cuadros, Vannattan and Gelkopf2018; Dhital et al., Reference Dhital, Shibanuma, Miyaguchi, Kiriya and Jimba2019; Yankey and Biswas Urmi, Reference Yankey and Biswas Urmi2019). Eight studies had more than one comparison groups (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Foster, Townsend and Bauman2014; Cluver, Reference Cluver2015; O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Nopembri et al., Reference Nopembri, Sugiyama, Saryono and Rithaudin2019; El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Cartwright, Maalouf, Haar, Zehra, Cokamay-Yilmaz and Calam2021). Eighteen studies were judged to be high risk of bias, 17 with medium risk of biases or having some concerns and eight with low risk of bias. (see Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of 43 RCTs

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; cRCT, cluster randomised controlled trial; DRC, democratic republic of the congo; N, sample size; NET, narrative exposure therapy; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RCT, randomised controlled trial; ROB, risk of bias; TAU, treatment as usual; *, primary outcome when reported.

Due to a substantive amount of heterogeneity, we were able to perform a meta-analysis and found a significant positive impact of MHPSS on grief (2 studies; pooled ES = −0.55*, 95% CI (−0.91, −0.19), I2 = 0%), and guilt (2 studies; pooled ES = −0.51*, 95% CI (−0.83, −0.19), I2 = 0%). In other outcomes, we reported a range of effect sizes, presenting mixed results across studies (see S4).

We performed an explorative analysis to assess the impact of MHPSS programmes by programme type. CBTs were evaluated in 20 studies (six low risk of bias, ten some concerns, four high risk of bias). All but two CBT programmes were delivered in a group format (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014; Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Joscelyne, Meijer, Steel, Silove and Bryant2018). The majority of the studies evaluated the impact of CBT delivered to children in conflict-affected settings, with three studies assessed its effects on children affected by earthquakes and tsunamis (Berger and Gelkopf, Reference Berger and Gelkopf2009; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014; Pityaratstian et al., Reference Pityaratstian, Piyasil, Ketumarn, Sitdhiraksa, Ularntinon and Pariwatcharakul2015). These CBT programmes were primarily delivered in school settings, with two conducted in refugee camps (Khamis and Coignez, Reference Khamis and Coignez2004; Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol2021), and one delivered at home(Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014). In three studies, the effect of culturally adapted, school-based trauma-based CBT designed for war-affected youth in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was examined, showing a significant reduction in PTSD, conduct and emotional problems (McMullen et al., Reference McMullen, O’callaghan, Shannon, Black and Eakin2013; O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty and Black2013; O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015). The finding from the meta-analysis suggested that CBT programmes have a potential to improve depression symptoms (pooled SMD = −0.15; 95% CI (−0.29, −0.01, I2 = 51.86%%) (Figure 3). We did not perform a meta-analysis of the effects of CBT on other outcomes due to heterogeneity.

Figure 3. Impact of CBT programmes on depression in children and young people (n = 12 studies).

We identified 11 RCTs (two low risk of bias, four some concerns, five high risk of bias) assessing the impact of psychosocial interventions (Dybdahl, Reference Dybdahl2001; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011; O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, Branham, Shannon, Betancourt, Dempster and McMullen2014; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Foster, Townsend and Bauman2014; O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Annan et al., Reference Annan, Sim, Puffer, Salhi and Betancourt2017; Panter-Brick et al., Reference Panter-Brick, Dajani, Eggerman, Hermosilla, Sancilio and Ager2018; Dhital et al., Reference Dhital, Shibanuma, Miyaguchi, Kiriya and Jimba2019; Nopembri et al., Reference Nopembri, Sugiyama, Saryono and Rithaudin2019; Torrente et al., Reference Torrente, Aber John, Starkey, Johnston, Shivshanker, Weisenhorn, Annan, Seidman, Wolf and Dolan2019; Yankey and Biswas Urmi, Reference Yankey and Biswas Urmi2019). These psychosocial programmes were varied in their programme design. Three of the interventions were delivered in Uganda, evaluating a creative play programme (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007), competitive sport and games (Richards et al., Reference Richards, Foster, Townsend and Bauman2014) and academic writing (Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011). Two psychosocial programmes were implemented in DRC involving community, school and family (O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, Branham, Shannon, Betancourt, Dempster and McMullen2014; O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Torrente et al., Reference Torrente, Aber John, Starkey, Johnston, Shivshanker, Weisenhorn, Annan, Seidman, Wolf and Dolan2019). These programmes used life skill training to address discrimination and to develop coping skills (O’callaghan et al., Reference O’callaghan, Branham, Shannon, Betancourt, Dempster and McMullen2014; Panter-Brick et al., Reference Panter-Brick, Dajani, Eggerman, Hermosilla, Sancilio and Ager2018; Nopembri et al., Reference Nopembri, Sugiyama, Saryono and Rithaudin2019; Yankey and Biswas Urmi, Reference Yankey and Biswas Urmi2019). One study evaluated the effect of psychosocial support for mothers in conflict-affected Bosnia and Herzegovina to improve mental health outcomes of their children (Dybdahl, Reference Dybdahl2001). Overall, the evidence is inconclusive regarding the impact of psychosocial programmes on children and young people’s mental health outcomes. There is no statistically significant improvement from participating psychosocial programmes on PTSD (n = 3 studies; pooled SMD = −0.18, CI 95% (−0.44,0.08) I2 = 39.07%), conduct problems (n = 2 studies, pooled SMD = 0.02, 95% CI (−0.18, 0.22), I2 = 30.03%), emotional problems (n = 2 studies; pooled SMD = −0.00, 95% CI (−0.16,0.15), I2 = 0%) or functioning (n = 2 studies, pooled SMD = 0.03, 95% CI (−0.29, 0.34), I2 = 0%). However, it is important to point out that the findings from the meta-analysis showed unintended impact of psychosocial programmes on depression symptoms (n = 5 studies pooled SMD = 0.17, 95% CI (0.00, 0.35), I2 = 14.49%). Three of five studies evaluated psychosocial programmes, aiming to engage children and young people with different activities such as songs, arts, sports or academic catch-up (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Foster, Townsend and Bauman2014). The other psychosocial programmes delivered the programmes to parents and teachers to support interactions with children and young people who affected by war (Dybdahl, Reference Dybdahl2001) and earthquake (Dhital et al., Reference Dhital, Shibanuma, Miyaguchi, Kiriya and Jimba2019).

Eight studies (four some concerns, four high risk of bias) evaluating the impact of narrative exposure therapy (NET) were included in the review.(Schauer von, Reference Schauer Von2008; Catani et al., Reference Catani, Kohiladevy, Ruf, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2009; Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011; Kalantari et al., Reference Kalantari, Yule, Dyregrov, Neshatdoost and Ahmadi2012; Lange-Nielsen et al., Reference Lange-Nielsen, Kolltveit, Thabet, Dyrgrove, Pallesen, Johnson and Laberg2012; Robjant et al., Reference Robjant, Koebach, Schmitt, Chibashimba, Carleial and Elbert2019; Getanda and Vostanis, Reference Getanda and Vostanis2020; Ahmadi et al., Reference Ahmadi, Jobson, Musavi, Rezwani, Amini, Earnest, Samim, Sarwary, Sarwary and McAvoy2023). Six NET programmes were delivered in a group format (Schauer von, Reference Schauer Von2008, Kalantari et al., Reference Kalantari, Yule, Dyregrov, Neshatdoost and Ahmadi2012, Lange-Nielsen et al., Reference Lange-Nielsen, Kolltveit, Thabet, Dyrgrove, Pallesen, Johnson and Laberg2012, Robjant et al., Reference Robjant, Koebach, Schmitt, Chibashimba, Carleial and Elbert2019, Getanda and Vostanis, Reference Getanda and Vostanis2020, Ahmadi et al., Reference Ahmadi, Jobson, Musavi, Rezwani, Amini, Earnest, Samim, Sarwary, Sarwary and McAvoy2023), with three delivered to individual participants.(Catani et al., Reference Catani, Kohiladevy, Ruf, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2009; Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011; Robjant et al., Reference Robjant, Koebach, Schmitt, Chibashimba, Carleial and Elbert2019). Two studies were carried out in Sri Lanka: one with children affected by civil war (Schauer von, Reference Schauer Von2008) and the other one was carried out immediately after the 2004 tsunami (Catani et al., Reference Catani, Kohiladevy, Ruf, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2009). Two were carried out in camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs): one in Palestine (Lange-Nielsen et al., Reference Lange-Nielsen, Kolltveit, Thabet, Dyrgrove, Pallesen, Johnson and Laberg2012) and the other in Uganda (Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011). One study was conducted in a refugee camp in Iran (Kalantari et al., Reference Kalantari, Yule, Dyregrov, Neshatdoost and Ahmadi2012). One study evaluated the NET programme delivered to female former child soldiers in DRC (Robjant et al., Reference Robjant, Koebach, Schmitt, Chibashimba, Carleial and Elbert2019). Another study evaluated the Memory Training for Recovery-Adolescent Intervention delivered to Afghan adolescent girls. The findings from the meta-analysis indicate that NET may have a significant impact in reducing the feelings of guilt (n = 2 studies; pooled SMD = -0.43, 95% CI (−0.79, − 0.07), I2 = 0%). However, NET may have no statistically significant impact on other internalised symptoms or functioning. One randomised study assessing the impact of the Writing for Recovery (WfR) programme in Gaza found that the children in the intervention group experienced an increase in depression and anxiety symptoms compared to the wait-list control group (Lange-Nielsen et al., Reference Lange-Nielsen, Kolltveit, Thabet, Dyrgrove, Pallesen, Johnson and Laberg2012).

In addition, we identified six studies (one low risk of bias, five high risk of bias) evaluating six interpersonal and body psychotherapy programmes including Group Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT-G) (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007), counselling (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014), yoga (Cluver, Reference Cluver2015), mind and body technique (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Staples, Blyta, Bytyqi and Wilson2008), logotherapy (SHoaakazemi et al., Reference Shoaakazemi, Momeni, Ebrahimi and Khalilid2012) and school-based psychotherapy (Layne Christopher et al., Reference Layne Christopher, Saltzman William, Poppleton, Burlingame Gary, Pasalic, Durakovic, Music, Campara, Apo, Arslanagic, Steinberg Alan and Pynoos Robert2008). The studies were carried out in five different countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, China, Haiti, Uganda and Kosovo) affected by armed conflict (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Staples, Blyta, Bytyqi and Wilson2008; Layne Christopher et al., Reference Layne Christopher, Saltzman William, Poppleton, Burlingame Gary, Pasalic, Durakovic, Music, Campara, Apo, Arslanagic, Steinberg Alan and Pynoos Robert2008) or natural disaster (SHoaakazemi et al., Reference Shoaakazemi, Momeni, Ebrahimi and Khalilid2012; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014). The most common outcomes reported in this group of programmes were PTSD and depression. We did not carry out statistical syntheses on these outcome measures because of differences and variations in psychotherapeutic programme modalities and intervention approaches. Four studies reported unadjusted mean scores and standard deviations of PTSD (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Staples, Blyta, Bytyqi and Wilson2008; Layne Christopher et al., Reference Layne Christopher, Saltzman William, Poppleton, Burlingame Gary, Pasalic, Durakovic, Music, Campara, Apo, Arslanagic, Steinberg Alan and Pynoos Robert2008; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014; Cluver, Reference Cluver2015). One study evaluating a mind–body skills group in Kosovo found a significant impact of the intervention on PTSD (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Staples, Blyta, Bytyqi and Wilson2008). The other studies suggested mixed findings for the interventions. Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014) found that support group counselling may have had little impact on PTSD in children and young people affected by the earthquake in China compared with those who received no intervention. The findings from the Layne Christopher et al. (Reference Layne Christopher, Saltzman William, Poppleton, Burlingame Gary, Pasalic, Durakovic, Music, Campara, Apo, Arslanagic, Steinberg Alan and Pynoos Robert2008) study also suggested that there might be little impact from a school-based psychotherapy intervention on schoolchildren in Bosnia. However, Cluver (Reference Cluver2015) found that yoga may increase PTSD in children and young people compared with those in an aerobic dance group.

Three studies assessed the impact of other psychotherapy interventions on depression (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Layne Christopher et al., Reference Layne Christopher, Saltzman William, Poppleton, Burlingame Gary, Pasalic, Durakovic, Music, Campara, Apo, Arslanagic, Steinberg Alan and Pynoos Robert2008; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shen, Gao, Lam, Chang and Deng2014). Only Bolton et al.’s (Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007) study evaluating an IPT-G programme reported a significant positive impact of the intervention on depression. In this study, 314 Acholi children aged 14–17 from two internally displaced person camps in Northern Uganda were randomly assigned to IPT-G, creative play, or a wait-list control group. At post-intervention, the IPT-G participants showed a greater reduction in depression symptoms than those in the wait-list control group.

Conclusions and discussion

In the last decade, considerable attempts have been made to support children and young people’s mental and psychosocial health in humanitarian emergencies (Barbui et al., Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton, Gastaldon, Gureje, Hanlon, Jordans, Lund, Nose, Ostuzzi, Papola, Tedeschi, Tol, Turrini, Patel and Thornicroft2020). Delivering CBT programmes has been suggested as a suitable choice of MHPSS programmes to reduce the symptoms of PTSD in adults across various humanitarian contexts (Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Felix and Dickson2019). However, the findings from this systematic review suggest inconclusive evidence regarding the effectiveness of other MHPSS modalities, such as NET or other psychotherapies, in improving internalising symptoms in children and young people. Similar results found in recent systematic reviews evaluating psychological therapies and social interventions suggest limited evidence of the programme impact on mental health of children and young people affected by humanitarian settings (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2018a; Papola et al., Reference Papola, Purgato, Gastaldon, Bovo, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2020). In addition, we found that studies evaluating psychosocial programmes incorporating components such as social support, child-friendly spaces, creative play, sports, games or academic catch ups reported potential unintended consequences. Future research should employ rigorous evaluation designs considering contextual and structural influences to better understand how these types of programming can be safely and effectively delivered to this specific population group in humanitarian settings.

We recognise that MHPSS programmes implemented in humanitarian settings may face several implementation challenges, and the observed unintended impact could arise from the interplay between programme delivery and socially and culturally sensitive contexts (Koch and Schulpen, Reference Koch and Schulpen2018). Moreover, challenges in recruiting, retraining and training programme personnel in low-resource settings, coupled with ongoing risks and insecurity, may affect the fidelity of programme implementation (Dickson and Bangpan, Reference Dickson and Bangpan2018). Recent research highlights the possibilities of training lay community workers to deliver MHPPS programme in resource-limited settings. Future research should investigate the effectiveness of this task shifting approach to guide the advancement of the implementation of MHPSS programmes (Cohen and Yaeger, Reference Cohen and Yaeger2021). In addition, some point out that children and young people face daily threats and ongoing stressful events in humanitarian emergencies which may require access to a wide range of basic social services. Therefore, further consideration to the importance of socio-ecological and multi-sectoral programming, as part of MHPSS programme design and delivery, aiming to prevent, treat and promote mental health of populations affected by humanitarian crises, is warranted (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2018a; Kamali et al., Reference Kamali, Munyuzangabo, Siddiqui, Gaffey, Meteke, Als, Jain, Radhakrishnan, Shah, Ataullahjan and Bhutta2020; Papola et al., Reference Papola, Purgato, Gastaldon, Bovo, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2020; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Ager, Bizouerne, Bryant, El Chammay, Colebunders, García-Moreno, Hamdani, James, Jansen, Leku, Likindikoki, Panter-Brick, Pluess, Robinson, Ruttenberg, Savage, Welton-Mitchell, Hall, Harper Shehadeh, Harmer and Van Ommeren2020; Raslan et al., Reference Raslan, Hamlet and Kumari2021; Papola et al., Reference Papola, Prina, Ceccarelli, Gastaldon, Tol, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Purgato2022). Future research might also benefit from considering the social determinants of mental health and developing a theory of change to understand mechanisms that improve mental health outcomes and well-being throughout the life course (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Balfour, Bell and Marmot2014).

The current systematic review offers an overview of the current state of evidence on the impact of MHPSS programmes on children and young people affected by humanitarian emergencies in LMICs. We assessed the impact of different types and modalities of MHPSS programmes, offering insights into their potential benefits and unintended consequences. Although our comprehensive search identified substantial evidence in the field, we noted some caveats when interpreting the findings. First, the quality of the studies included in the systematic review varied, with the majority judged to have some quality concerns or being at a high risk of bias. This limitation of the existing evidence is also expressed by recent systematic reviews highlighting a low quality of evidence on the impact of the programmes aiming to prevent and treat mental health in children and young people affected by humanitarian settings (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2018a; Papola et al., Reference Papola, Purgato, Gastaldon, Bovo, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2020). Second, we included only studies published in English. Other high-quality studies published in other languages may provide further evidence on the impact of MHPSS programmes, especially studies from Central and South America. Third, we identified a wide range of outcomes using various scales, reflecting the attempt to adapt tools for measuring the mental health and wellbeing outcomes across socio-cultural settings. Finally, the studies included in the meta-analysis were heterogeneous, drawing on a broad evidence base that aims to evaluate the impact of multi-component, multi-level MHPSS programmes on various outcomes across humanitarian settings. Future development and evaluation of MHPSS programmes would benefit from engaging with key stakeholders and local communities to understand and theorise how interventions intend to work and how socio-cultural factors might influence their observed impact (Kneale et al., Reference Kneale, Bangpan, Thomas and Sharma Waddington2020; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Jordans, Tol and Galappatti2021).

We systematically reviewed research evaluating the impact of MHPSS programmes on children and young people affected by humanitarian emergencies in LMICs. Sixty studies met the inclusion criteria. We identified several research gaps. In sub-Saharan Africa, although more than one-fifth of global refugees and internally displaced persons are hosted in countries such as the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Somalia and South Sudan (UNHCR, 2018), our systematic review identifies the paucity of rigorous evidence to inform the design and implementation of MHPSS programmes in this region, in line with the recent meta-review focusing on vulnerable African children (Katsonga-Phiri et al., Reference Katsonga-Phiri, Grant and Brown2019). Secondly, there is increasing recognition of the need to develop MHPSS programmes that are tailored to girls’ and boys’ needs, considering the social determinants of their individual psychological health and well-being (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon, Gordon, O’callaghan, Papola, Peltonen, Punamaki, Richards, Staples, Unterhitzenberger, Van, De, Jordans, Tol and Barbui2018b; Raslan et al., Reference Raslan, Hamlet and Kumari2021; Lasater et al., Reference Lasater, Flemming, Bourey, Nemiro and Meyer2022). Yet, we identified limited evidence examining the impact of gender-specific MHPSS programmes. Furthermore, we did not come across any studies explicitly targeting children with disabilities. There is a need to further develop inclusive MHPSS programmes that not only address the unique needs of children with disabilities but also consider the influence of intersectionality and factors, such as gender, culture and religion. Additional research gap identified from this systematic review includes evaluations of MHPSS programmes aiming to protect children and young people’s well-being in humanitarian settings through basic service and security provision. Finally, future evaluative research should aim to capture the long-term impact and assess the cost-effectiveness of MHPSS programmes (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2018a; Papola et al., Reference Papola, Prina, Ceccarelli, Gastaldon, Tol, Van Ommeren, Barbui and Purgato2022).

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.17.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.17.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, references and/or its Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Anna Chiumento who offered guidance on mental health research in LMICs for the systematic review.

Author contribution

M.B. and K.D. designed the study, developed and wrote the initial draft of the protocol. L.F. led the writing on the method section of the meta-analysis methodology in the protocol. M.B. managed the overall project. M.B. and K.D. developed the search strategy. M.B. updated the search. M.B. and L.F. retrieved the full texts and screened all studies. M.B., L.F., F.S., P.D. and A.J. performed data extraction and quality assessment of the included studies. M.B. and L.F. planned the analysis. M.B. and L.F. performed the meta-analysis, sensitivity analysis and meta-regression. A.J. wrote the initial draft of the introduction, and M.B. wrote the rest of the manuscript, with all other authors contributing to its revision and finalisation. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript and gave final approval for submission.

Competing interest

A.J. has a project funded by the National Institute for Health Research ARC North Thames. This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research ARC North Thames. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

A.J. has a studentship funded by the Economic Social research council via the London Interdisciplinary Social Science Doctoral Training Partnership. Grant award number: ES/P000703/1 – PR – 2,462,475.

Comments

No accompanying comment.